Abstract

As a field, psychiatry is undergoing an exciting paradigm shift toward early identification and intervention that will likely minimize both the burden associated with severe mental illnesses as well as their duration. In this context, the rapid-acting antidepressant ketamine has revolutionized our understanding of antidepressant response and greatly expanded the pharmacologic armamentarium for treatment-resistant depression. Efforts to characterize biomarkers of ketamine response support a growing emphasis on early identification, which would allow clinicians to identify biologically enriched subgroups with treatment-resistant depression who are more likely to benefit from ketamine therapy. This chapter presents a broad overview of a range of translational biomarkers, including those drawn from imaging and electrophysiological studies, sleep and circadian rhythms, and HPA axis/endocrine function as well as metabolic, immune, (epi)genetic, and neurotrophic biomarkers related to ketamine response. Ketamine’s unique, rapid-acting properties may serve as a model to explore a whole new class of novel rapid-acting treatments with the potential to revolutionize drug development and discovery. However, it should be noted that although several of the biomarkers reviewed here provide promising insights into ketamine’s mechanism of action, most studies have focused on acute rather than longer-term antidepressant effects and, at present, none of the biomarkers are ready for clinical use.

1. Conceptual introduction to ketamine biomarkers

The glutamatergic modulator ketamine is a rapid-acting antidepressant effective for treatment-resistant depression and suicidal ideation, but the precise neurobiological mechanisms underlying its antidepressant effects remain unclear. In this vein, a need exists for objective measures to better stratify depressed individuals into biologically enriched subgroups according to their propensity to respond to the existing pharmacologic armamentarium. Unless effective strategies are in place for such stratification, the potential of therapy with ketamine or other next-generation antidepressants may remain untapped.

Briefly, a biomarker is defined as a quantifiable substrate of an overlying illness state. Biomarkers are organized by form and function. Here, “form” refers to the specific biological domain—genomic, metabolomic, immune, hormonal, physiological, structural, or connectomic biomarkers, among others. In contrast, “function” is a broad designation related to the translational application for diagnosis and/or treatment (e.g., diagnostic, disease, predictive, or therapeutic) (see Fig. 1). Furthermore, biomarkers can be considered either predictive or as possible mediators/moderators of response. Predictive biomarkers are specific factors, present at baseline, that predict better or worse response to a treatment. Mediator/moderator biomarkers illuminate potential mechanisms of treatment, particularly if change in the specific biological factor is associated with treatment response. Understanding both predictive biomarkers and specific mechanisms (mediators) is critical for future efforts in precision medicine.

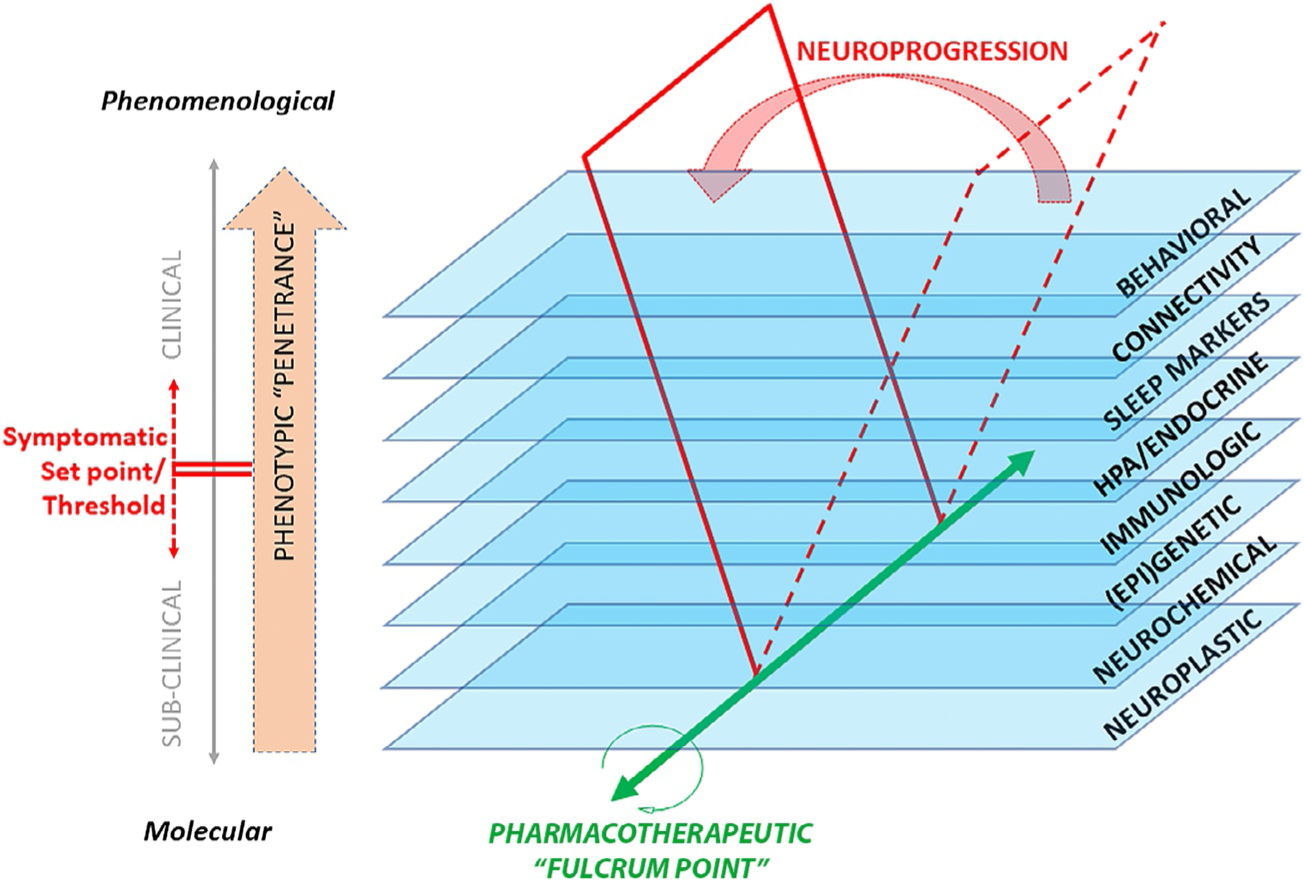

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of neuroprogression, briefly defined as dynamic changes in the various levels of biological substrates (central and systemic) underlying the chronic, relapsing-remitting clinical course of mental illness.

The notion of “target engagement” in translational psychiatry arises from mapping the mechanisms of a therapeutic intervention onto a biological substrate specific to an illness (Niciu, Mathews, et al., 2014). The search for biomarkers of response to ketamine can therefore be conceptualized as the search for surrogate biomarkers of target engagement within a biologically enriched clinical subgroup. As an example, family history of alcohol dependence has been associated with different physiological characteristics and with treatment response to ketamine in depressed participants, suggesting high loading of associated risk factors onto a clinically enriched subgroup (Niciu, Luckenbaugh, Ionescu, Richards, et al., 2014; Petrakis et al., 2004). In addition, treatment-resistant depression has been increasingly associated with neurometabolic perturbations in vulnerable regions of the CNS (Miller, Haroon, Raison, & Felger, 2013) that unfold in a chronic, relapsing-remitting process known as neuroprogression (Boufidou & Halaris, 2017) (see Fig. 1).

In this context, identifying novel biomarkers of response to ketamine may be operationalized as characterizing moderating and mediating relationships between biomarkers and clinical outcomes. Information generated via ketamine studies at each level of a specific biological domain (for instance, genomic, metabolomic, immune, hormonal, physiological, structural, or connectomic biomarkers) will lead to a better understanding of the mechanistic processes underlying ketamine’s therapeutic properties. As will be discussed later, it is likely that response to ketamine is much more nuanced than “normalization”—that is, achieving a specific biological domain toward that of healthy participants—but rather involves, at each domain, a set point threshold that needs to be achieved. Clinical outcome depends on where an individual is at baseline before receiving a specific treatment (i.e., ketamine) referred to as the “fulcrum point” or homeostasis (Fig. 1).

This chapter, which focuses on human rather than animal studies conducted with ketamine, presents a broad overview of a range of translational biomarkers, including those drawn from imaging and electrophysiological studies (Table 1), sleep and circadian rhythms, and HPA axis/endocrine function as well as metabolic, immune, (epi)genetic, and neurotrophic biomarkers related to ketamine response. Ketamine’s unique, rapid-acting properties may serve as a model to explore a whole new class of novel rapid-acting treatments with the potential to revolutionize drug development and discovery.

Table 1.

Neuroimaging and electrophysiological markers of response to ketamine.

| Type of study | Biomarker used | Sample/design | Biomarker finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positron emission tomography (PET) | |||

| Carlson et al. (2013) | [18F]FDG PET | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 20) | In the voxel-wise correlational analysis, antidepressant response was significantly correlated with increasing metabolism in superior and middle temporal gyri (STG/MTG) and cerebellum. Clinical improvement significantly correlated with decreasing metabolism in more ventral and medial loci within the STG/MTG along with the parahippocampal gyrus, inferior parietal cortex, and temporo-occipital cortex |

| Chen et al. (2018a) | [18F]FDG PET | MDD TRD (n = 24) randomized to 0.2 or 0.5 mg/kg i.v. infusion over 40 min | Increased glucose metabolism in the dACC was associated with antidepressant response in participants who received a 0.5 mg/kg dose of ketamine |

| Esterlis et al. (2018) | [11C]ABP688 PET | MDD (n = 13)andHVs (n = 13) | At baseline, significantly lower [11C]ABP688 binding was detected in the MDD participants versus the HVs. Significant ketamine-induced reductions in mGluR5 availability in both groups persisted 24 h later. Depressive symptoms were reduced in the MDD group post-ketamine, an effect associated with binding changes immediately post-ketamine |

| Li et al. (2016) | [18F]FDGPET | MDD TRD (n = 48) randomized to saline placebo, 0.2, or 0.5 mg/kg ketamine infusion | Increased glucose metabolism in the PFC was associated with antidepressant response. No relationship between glucose metabolism in the amygdala and antidepressant response was observed |

| Nugent et al. (2014) | [18F]FDG PET | BD (n = 21) | Change in glucose metabolism in right ventral striatum was inversely related to antidepressant response. Glucose metabolism in the sgACC post-placebo was positively correlated with percentage improvement in MADRS score post-ketamine |

| Structural MRI (sMRI) | |||

| Abdallah et al. (2015) | Hippocampal volume | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 16) | Left hippocampal volume was associated with antidepressant response to ketamine |

| Abdallah et al. (2017) | Nucleus accumbens (NAc) and hippocampal volume | Cohort A: MDD (n = 34) and HVs (n = 26). Cohort B: MDD (n = 16) | Only Cohort B received ketamine. In cohort A, MDD participants had larger left NAc volume than HVs. In cohort B, ketamine treatment reduced left NAc, but increased left hippocampal volumes in MDD participants achieving remission |

| Niciu et al. (2017)a | Baseline subcortical volumes, BDNF rs6265 genotype (val/met) | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 55) | No correlation found between subcortical volumes and antidepressant response. Thalamic volume negatively correlated with antidepressant response to ketamine in met carriers (n = 14) |

| Ortiz et al. (2015)a | Shank3 blood, volumetric measurements, [18F]FDG PET, sMRI | Bipolar depression (n = 29) | No correlation between hippocampal volume and antidepressant response. Higher baseline Shank3 levels predicted antidepressant response at Days 1, 2, and 3 and were associated with larger right amygdala volume. Higher baseline Shank3 also predicted increased glucose metabolism in the amygdala and hippocampus |

| Vasavada et al. (2016) | DTI | MDD (n = 10) and HVs (n = 15) | Larger fractional anisotropy (FA) values in the cingulum and forceps minor in antidepressant responders compared to non-responders. Decreased radial diffusivity in cingulum in responders compared to non-responders |

| Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) | |||

| Evans et al (2018) | 1H-MRS (glutamate) in pgACC | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 20) and HVs (n = 17) | Baseline glutamate levels were not associated with antidepressant response |

| Milak et al. (2016) | 1H-MRS (GABA and Glx) in medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) | MDD medication-free (n = 11) | No association between antidepressant response and either GABA or Glx in the mPFC |

| Salvadore et al. (2012) | 1H-MRS (GABA, glutamate, Glx/glutamate ratio) in vmPFC and dorsomedial/dorsal anterolateral prefrontal cortex (DM/DA-PFC) | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 14) | Pretreatment GABA and glutamate concentrations did not correlate with antidepressant response. Pretreatment Glx/glutamate ratio in the DM/DA-PFC was negatively correlated with antidepressant response. No significant correlation of MRS markers with Day 1 antidepressant response |

| Valentine et al. (2011) | 1H-MRS (glutamate, GABA, glutamine) in occipital cortex | MDD medication-free (n = 10) | The rapid (1 h) and sustained (at least 7 days) antidepressant effects of ketamine infusion were not associated with either baseline measures of, or changes in, occipital amino acid neurotransmitter content |

| Functional MRI (fMRI) | |||

| Abdallah et al. (2017) | Global brain connectivity with global signal regression (GBCr, resting-state) | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 18) and HVs (n = 25) | Individuals who responded to ketamine had higher delta GBCr values in the PFC, caudate, and insula. Exploratory seed-based analyses showed increased lateral PFC and caudate connectivity with regions outside the PFC and subcortex in ketamine responders compared to non-responders, but lower connectivity within the PFC and subcortical regions |

| Abdallah et al. (2017) | Global brain connectivity with global signal regression (GBCr, resting-state) | Cohort A: MDD TRD (n = 22) and HVs (n = 29). Cohort B: HVs (n = 18) | TRD participants had significant reductions in dorsomedial and dorsolateral prefrontal GBCr compared to HVs. In TRD participants, GBCr in the altered clusters increased significantly 24 h post-ketamine but not post-midazolam control |

| Abdallah et al. (2018) | Global brain connectivity with global signal regression (GBCr, resting-state) | Unmedicated MDD (n = 56; 19 received ketamine, 19 received lanicemine, and 18 received placebo) | Compared to placebo, ketamine significantly increased average PFC GBCr during ketamine infusion and 24 h later. Average delta PFC GBCr (during minus baseline) positively predicted improvement in depressive symptoms in participants receiving ketamine or lanicemine but not those receiving placebo |

| Evans et al. (2018) | Default mode network (DMN) connectivity during resting-state scan | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 33) and HVs (n = 25) | DMN connectivity with the insula normalized after ketamine administration to levels comparable to a sample of HVs |

| Morris et al. (2020) | fMRI response to an incentive-processing task | MDD (n = 28) and HVs (n = 20) | MDD participants had higher sgACC activation to positive and negative monetary incentives than HVs. Ketamine also reduced sgACC hyper-activation to positive, but not negative, incentives |

| Murrough, Collins, et al. (2015) | fMRI response to two emotional face perception tasks (negative and positive emotions) | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 20) and HVs (n = 20) | In a negative emotion task, no biomarkers of antidepressant response were found. In a positive emotion task, no correlation was found for whole-brain analysis. A connectivity analysis showed a significant correlation between right caudate connectivity post-infusion and antidepressant response |

| Reed et al. (2018) | fMRI response to emotional attention task (dot-probe) | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 33) and HVs (n = 26) | Compared to placebo, ketamine administration was significantly associated with less activation to angry trials and greater activation to happy trials in the left parahippocampal gyrus and amygdala, bilateral cingulate gyri, precuneus, and left medial and middle frontal gyri |

| Reed et al. (2019) | fMRI response to emotional evaluation task | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 33) and HVs (n = 24) | Compared to placebo, ketamine was associated with decreased activity in a right frontal cluster that extended into the ACC and insula in MDD participants; this effect was reversed in a comparison sample of HVs |

| Kraus et al. (2020) | Global brain connectivity with GBCr, resting-state | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 28) and HVs (n = 22) | Reduced pretreatment GBC in individuals with TRD versus HVs in the middle cingulate cortex, ACC, and PFC. No differences in GBCr between ketamine and placebo and no association with antidepressant response |

| Magnetoencephalography (MEG) | |||

| Cornwell et al. (2012) | Response to tactile stimulation to the right and left index fingers | MDD TRD medication free (n = 20) | MDD participants with robust improvements in depressive symptoms 230 min post-infusion (responders) exhibited increased cortical excitability. Stimulus-evoked somatosensory cortical responses increased after infusion relative to pretreatment response in responders but not in treatment non-responders |

| Gilbert, Yarrington, Wills, Nugent, and Zarate (2018) | Response to tactile stimulation (air puff) | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 18) and HVs (n = 18) | Dynamic causal modeling (DCM) was used to estimate connectivity changes in AMPA and NMDA receptors. Antidepressant response was associated with reduced NMDA and AMPA connectivity within the somatosensory cortex |

| Nugent, Robinson, Coppola, and Zarate (2016) | MEG functional connectivity (resting-state), [18F]FDG PET | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 13) | Decreased baseline connectivity in the sgACC was associated with changes in sgACC glucose metabolism in eight of the 13 participants who underwent PET imaging. No findings correlated with antidepressant response |

| Nugent, Ballard, et al. (2019) | Resting-state MEG recordings (gamma power) | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 35) and HVs (n = 25) | No difference between antidepressant response and gamma power was observed 40 min post-infusion. Lower baseline gamma at baseline was associated with greater antidepressant response at 40 min post-infusion; participants with higher gamma power had an attenuated antidepressant response |

| Nugent, Wills, Gilbert, and Zarate (2019) | Resting-state MEG recordings (gamma power) | MDD TRD (n = 31) and HVs (n = 25) | A significant difference in peak gamma power was seen in the depressed ketamine responders versus non-responders at 230 min and at 1 day post-ketamine |

| Salvadore et al. (2009) | MEG recordings of fearful faces task | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 11) and HVs (n = 11) | Increased pretreatment ACC activity in response to fearful faces was associated with antidepressant response to ketamine |

| Salvadore et al. (2010) | MEG recordings of working memory (WM) task | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 15) | Participants who showed the least engagement of the pgACC in response to increased WM load showed the greatest antidepressant response. Pretreatment functional connectivity between the pgACC and the left amygdala was negatively associated with antidepressant response |

| Electroencephalography (EEG)b | |||

| Sumner et al. (2020) | EEG to assess long-term potentiation as a measure of neural plasticity | MDD (n = 30) | Ketamine increased visual long-term potentiation-mediated neural plasticity |

| Multimodal (neuroimaging or electrophysiology and another biomarker) | |||

| McMillan et al. (2020) | EEG/phMRI | MDD (n = 30) | BOLD signal decrease in sgACC was not related to antidepressant response to ketamine; changes in BOLD signal were likely the result of artifacts and emphasize the importance of noise correction and multiple temporal regressors for phMRI analyses |

| Niciu et al. (2017)a | Baseline subcortical volumes, BDNF rs6265 genotype (val/met) | MDD TRD medication-free (n = 55) | No correlation found between subcortical volumes and antidepressant response. Thalamic volume negatively correlated with antidepressant response to ketamine in met carriers (n = 14) |

| Nugent, Farmer, et al. (2019) | DTI, MRS, resting-state fMRI, MEG | MDD TRD (n = 30), HVs (n = 26) | A correlation was observed along tracts connecting the sgACC and right amygdala between FA and subsequent antidepressant response to ketamine infusion in MDD participants |

| Ortiz et al. (2015)a | Shank3 blood, volumetric measurements, [18F]FDG PET, sMRI | Bipolar depression (n = 29) | No correlation between hippocampal volume and antidepressant response. Higher baseline Shank3 levels predicted antidepressant response at Days 1, 2, and 3 and were associated with larger right amygdala volume. Higher baseline Shank3 levels also predicted increased glucose metabolism in the amygdala and hippocampus |

| Woelfer et al. (2019) | BDNF rs6265 genotype (val/met), BDNF plasma level changes, resting-state functional connectivity | HVs (n = 53) | Higher relative levels of plasma BDNF were observed two and 24h post-ketamine versus post-placebo. In whole-brain regression, change in BDNF levels 24 h post-ketamine was associated with resting-state functional connectivity in the dorsomedial PFC |

Because they apply to more than one category, some studies are listed twice.

McMillan et al. (2020) is included under the multimodal header because this study included both phMRI and EEG.

Abbreviations: ACC: anterior cingulate cortex; AMPA: α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; BOLD: blood-oxygen-level-dependent; dACC: dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; DMN: default mode network; DTI: diffusion tensor imaging; EEG: electroencephalography; [18F]FDG PET: 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography; FA: fractional anisotropy; fMRI: functional magnetic resonance imaging; GABA: gamma aminobutyric acid; GBC: global brain connectivity; GBCr: global brain connectivity with global signal regression; Glx: glutamate+glutamine; GSR: global signal regression; HV: healthy volunteer; MADRS: Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MDD: major depressive disorder; MEG: magnetoencephalography; mGluR5: metabotropic glutamate receptor 5; mPFC: medial prefrontal cortex; MRS: magnetic resonance spectroscopy; MTG: middle temporal gyri; NAc: nucleus accumbens;NMDA: N-methyl-d-aspartate; PFC: prefrontal cortex; phMRI: pharmacologic magnetic resonance imaging; pgACC: pregenual anterior cingulate cortex; sgACC: subgenual anterior cingulate cortex; STG: superior temporal gyri; TRD: treatment-resistant depression; vmPFC: ventromedial PFC; WM: working memory

2. Neuroimaging and electrophysiological markers of response to ketamine

Several neuroimaging modalities have been leveraged to discover neural markers of the mechanistic processes presumably implicated in ketamine’s antidepressant mechanism of action. In positron emission tomography (PET), biologically active molecules (e.g., fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)) are labeled with injected radioactive tracers, allowing activity to be measured in an area of the brain as glucose is metabolized; higher metabolic rates are associated with higher levels of activity. Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses morphometric methods to measure volumetric and shape differences in subcortical structures. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) can evaluate the in vivo effects of ketamine on glutamatergic pathophysiology. Functional MRI (fMRI) uses blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) contrasts in the brain to measure both baseline neural activity (resting-state fMRI) or activity in response to stimuli (task-based fMRI). Magnetoencephalography (MEG) and electroencephalography (EEG), respectively, record magnetic or electrical activity in the brain with excellent temporal resolution. Brain connectivity analyses using MRI, EEG, and MEG refer to the temporal synchronization of neural activity in spatial locations that may be distinct and/or distributed. Thus, pharmacoimaging paradigms offer considerable potential as future biomarkers of antidepressant response to ketamine.

2.1. PET

PET has been used to study the neural mechanisms of acute antidepressant response to ketamine. In a study by Carlson and colleagues, 20 unmedicated individuals with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) underwent [18F]FDG PET to measure regional cerebral glucose metabolism at baseline and following ketamine infusion (single intravenous dose of 0.5mg/kg over 40min) (Carlson et al., 2013). Regional metabolism decreased significantly post-ketamine in the insula, habenula, and ventrolateral and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices of the right hemisphere. Furthermore, acute improvement in depression rating scale scores (230min post-ketamine infusion) correlated directly with metabolism changes in the right superior and middle temporal gyri. Conversely, metabolism increased in the sensory association cortices, conceivably related to the illusory phenomena sometimes experienced with ketamine (Carlson et al., 2013).

Using [18F]FDG PET in 21 participants with bipolar depression, a region of interest analysis by Nugent and colleagues found that acute improvement in depressive symptoms post-ketamine (230min post-ketamine infusion) correlated with a corresponding increase in regional cerebral glucose metabolism in the right ventral striatum. Furthermore, in a voxel-wise analysis, participants had significantly lower glucose metabolism in the left hippocampus post-ketamine infusion than post-placebo infusion (Nugent et al., 2014). In another [18F]FDG PET imaging study, Li and colleagues found increased glucose metabolism in the PFC post-ketamine, a result that correlated with reduced depressive symptoms within 240min post-ketamine infusion (Li et al., 2016). The same group found that, after controlling for the effects of age, sex, amygdala changes post-infusion, and ketamine dose (0.2 or 0.5mg/kg), cerebral glucose uptake in the PFC post-ketamine was the most significant predictor of antidepressant effects at both 40 and 240min post-infusion. In another [18F]FDG PET study, Chen and colleagues reported a significant relationship between increased dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) glucose uptake and fewer depressive symptoms 24h post-infusion in participants with treatment-resistant depression who received the standard 0.5mg/kg ketamine dose, but no significant relationship in those who received a 0.2mg/kg dose (Chen et al., 2018a).

It should be noted that, to date, no suitable PET receptor ligand for N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) or α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid (AMPA) receptors has been identified. However, some success has been achieved in developing PET ligands for metabotropic glutamate receptors. These receptors, particularly mGluR5, are extrasynaptically/perisynaptically localized at postsynaptic densities, and their activation regulates excitotoxic glutamate synaptic levels. In mood disorders research, mGluR5 concentrations have been positively correlated with NMDA receptor levels; metabotropic and NMDA receptors are linked by a variety of intracellular mechanisms, thus allowing the NMDA receptor to be modulated by manipulating mGluR5 (Park, Niciu, & Zarate, 2015). Esterlis and colleagues examined the effects of ketamine on ligand binding to mGluR5 in both individuals with MDD (n = 13) and healthy volunteers (n = 13) and found that ketamine significantly reduced mGluR5 availability (i.e., [11C]ABP688 binding) in both MDD and healthy volunteers, an effect that persisted 24h later (Esterlis et al., 2018). A significant reduction in depressive symptoms was also observed post-ketamine administration (1 day post-infusion) in MDD participants; this reduction was associated with binding changes observed immediately post-ketamine. The investigators hypothesized that the glutamate released post-ketamine moderated mGluR5 availability, a change that appeared to be related to acute antidepressant efficacy. Thus, the sustained decrease in binding may have reflected prolonged mGluR5 internalization in response to glutamate surge (Esterlis et al., 2018).

Notably, the PET moderator/mediator biomarker studies in depression reviewed above all examined acute antidepressant treatment response (within 24h) (see Table 1). While encouraging, these results are preliminary in nature and suggest that PET is not yet ready for clinical use. However, the development of an NMDA or AMPA receptor PET ligand would significantly impact the field.

2.2. Structural MRI

MRI studies have been used to explore brain region volume and white matter tract integrity as indicators of response to ketamine. For hippocampal volume, the extant evidence is largely negative (Abdallah et al., 2015; Niciu et al., 2017).

In vivo structural alterations of the nucleus accumbens have also been examined. Sixteen individuals with MDD underwent MRI at baseline and at 24h following an intravenous ketamine infusion (0.5mg/kg). The investigators found that ketamine treatment reduced the volume of the left nucleus accumbens but increased left hippocampal volume in participants achieving remission (Abdallah et al., 2017).

Finally, white matter integrity is an established indicator of cognitive function (Madden, Bennett, & Song, 2009). In a preliminary diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) study of 10 individuals with MDD receiving ketamine, antidepressant responders compared to non-responders had greater white matter integrity in the cingulum and structural changes in the forceps minor and striatum (Vasavada et al., 2016).

In summary, only a few relevant structural MRI studies have been conducted, and all have had small sample sizes. Such studies should remain in the research setting until larger controlled studies with ketamine in MDD are conducted (see Table 1).

2.3. MRS

Proton MRS studies of glutamatergic transmission support the involvement of neurochemical markers in ketamine’s antidepressant effects. Early preclinical studies found that acute glutamatergic changes in the brain were consistent with the theory that a transient glutamate surge or “burst” plays a critical role in ketamine’s acute antidepressant effects (Duman, 2014). In individuals with MDD, Salvadore and colleagues found that pretreatment Glx/glutamate ratio in the dorsomedial/dorsal anterolateral prefrontal cortex (DM/DA-PFC) was negatively correlated with acute improvement in depressive symptoms at 230min post-ketamine infusion (Salvadore et al., 2012). Subsequent work by Milak and colleagues found that ketamine affected Glx and gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels in the medial PFC, with significant increases from baseline levels observed in MRS spectra obtained over the course of a 40-min ketamine infusion (Milak et al., 2016); however, these changes were not associated with post-ketamine (within 230min) improvements in depressive symptoms.

Abdallah and colleagues found that the ratio of carbon-13 (13C) MRS glutamate/glutamine—a putative measure of neurotransmission strength that correlated with Clinician Administered Dissociative States Scale (CADSS) scores—was enriched during ketamine infusion, providing further evidence that ketamine increases glutamate release in the PFC in a manner that may induce rapid antidepressant effects (Abdallah et al., 2018). In contrast, Valentine and colleagues found no relationship between baseline amino acid neurotransmitter levels and the rapid (1h) or sustained (at least 7 days) antidepressant effects of ketamine, nor did they find that ketamine affected neurotransmitter levels 3h or 2 days post-infusion (Valentine et al., 2011). Another MRS 7-Tesla (7T) study found that levels of neither pregenual baseline glutamate nor other neurochemicals measured (e.g., choline, N-acetyl-aspartate, glutamine, glutathione, creatine) predicted antidepressant response at 1 day post-infusion (Evans et al., 2018).

These findings suggest that the results of MRS studies are mixed. Notably, of the proton MRS moderator/mediator biomarker ketamine studies in depression reviewed above, all but one examined acute antidepressant treatment response (within 24h). The limited evidence for longer-term alterations in neurotransmission post-infusion or for a relationship between changes in neurotransmission and antidepressant response suggests that glutamate surge alone may not suffice to explain sustained antidepressant response to ketamine. Another possibility is that the glutamate surge occurs very rapidly in response to ketamine infusion (within 1h) and thus would not be detected at the later time points obtained in the studies; indeed, some preliminary evidence suggests that the Glx/glutamate ratio peaks within the first 40min (Milak et al., 2016).

In summary, MRS is presently limited to the research realm and is not ready for clinical use. Future MRS studies are needed to determine the immediate effects of ketamine on brain glutamate levels and the relationship between both acute and sustained antidepressant effects (see Table 1).

2.4. fMRI

fMRI techniques have been used to evaluate responses to specific stimuli as well as network connectivity changes in response to ketamine. Notably, significantly altered global brain connectivity (GBC)—a measure of the brain’s network hubs—in the PFC, cingulate cortex, and other brain areas such as cerebellum has been observed in individuals with treatment-resistant depression. In GBC with global regression (GBCr), the value represents the average correlation between BOLD activity at one voxel and all other gray matter voxels. Abdallah and colleagues used resting-state fMRI to study GBCr in 18 medication-free individuals with treatment-resistant depression treated with ketamine. They found that the GBCr of ketamine responders resembled values seen in healthy volunteers after ketamine treatment, suggesting normalization (Abdallah et al., 2017). Because the results pointed toward a role for PFC connectivity in ketamine’s antidepressant efficacy, Abdallah and colleagues subsequently sought to replicate this finding of PFC connectivity underlying the mechanism of antidepressant response to ketamine. This follow-up study found that individuals with treatment-resistant depression showed significant reductions in dorsomedial and dorsolateral PFC GBCr compared to healthy volunteers (Abdallah et al., 2017). In participants with treatment-resistant depression, GBCr in the altered clusters significantly increased 24h post-ketamine, but not post-midazolam, the active control. As with the prior study, these findings underscored ketamine’s ability to normalize depression-related prefrontal dysconnectivity. In a subsequent study, the same investigators examined GBCr in 56 unmedicated individuals with MDD who were randomized to receive intravenous ketamine (0.5mg/kg; n = 19), lanicemine (100mg; n = 19), or placebo (n = 18). Compared to placebo, ketamine significantly increased average PFC GBCr during ketamine infusion as well as 24h later. Average delta PFC GBCr (during minus baseline) showed a pattern of positively predicting improvement in depressive symptoms in participants receiving ketamine or lanicemine but not those receiving placebo (Abdallah et al., 2018).

Building on this work, Kraus and colleagues used rsfMRI and identical preprocessing strategies to seek to replicate the finding of altered GBC in individuals with treatment-resistant depression; the investigators found significant group differences, with reduced pretreatment GBC in individuals with treatment-resistant depression versus healthy volunteers in the middle cingulate cortex and ACC as well as in the PFC in similar—though not identical—clusters to those identified by Abdallah and colleagues (Kraus et al., 2020). However, in contrast to previous findings, this study detected no ketamine versus placebo or ketamine versus pretreatment differences, either in healthy volunteers or in individuals with treatment-resistant depression.

Recent fMRI studies are also consistent with the homeostatic hypothesis, which suggests that ketamine acts by restoring homeostasis to aberrant systems altered by the pathophysiology of MDD (Fig. 1). One fMRI study examined the effect of a single ketamine infusion on the resting-state default mode network (DMN) at two and 10 days after a single ketamine infusion in unmedicated individuals with MDD as well as healthy volunteers (Evans et al., 2018). In MDD participants, connectivity between the insula and the DMN was normalized compared with healthy volunteers 2 days post-ketamine infusion. This change was reversed after 10 days and did not appear in either of the placebo scans. The findings suggest that ketamine may normalize the interaction between the DMN and salience networks, supporting the triple network dysfunction model of MDD (Evans et al., 2018).

Task-related fMRI studies have also implicated normalization of functioning after ketamine administration. In individuals with treatment-resistant MDD, two fMRI studies examined BOLD activity—one used an event-related fMRI during an emotional attention task (dot-probe) and the other used an emotional evaluation task. The investigators observed decreased activity approximately 2 days post-ketamine compared to post-placebo in regions implicated in depression (Reed et al., 2018, 2019). Intriguingly, in both studies, healthy volunteers displayed the opposite effect, with increased activation post-ketamine compared to post-placebo in the implicated regions, indicating disrupted homeostasis in healthy individuals (Reed et al., 2018, 2019). Murrough and colleagues similarly used fMRI and two separate emotion perception tasks to examine the neural effects of ketamine in 20 individuals with treatment-resistant depression 24h post-ketamine infusion. Compared with healthy volunteers, participants with treatment-resistant depression showed reduced neural responses to positive faces within the right caudate. After ketamine, neural responses to positive faces were selectively increased within a similar region of the right caudate (Murrough, Collins, et al., 2015). In addition, Morris and colleagues recently reported that ketamine normalized sgACC cortex hyperactivity in individuals with MDD (Morris et al., 2020). In this study, 28 MDD participants and 20 healthy volunteers completed task-based fMRI using an incentive-processing task. In the second part of the study, 14 MDD participants underwent the same task-based fMRI at baseline and 40min after a 40-min ketamine infusion. Individuals with MDD showed higher sgACC activation to positive and negative monetary incentives than healthy volunteers. Ketamine also reduced sgACC hyper-activation to positive, but not negative, incentives (Morris et al., 2020).

Taken together, these studies suggest that normalization of connectivity may be a neural marker of ketamine’s antidepressant effects (see Table 1). Nevertheless, the results are preliminary in nature. Thus, neither resting-state nor task-related fMRI is yet ready for clinical use as a technique to predict treatment response to ketamine. It should also be noted that all but one of the studies reviewed above examined acute rather than longer-term (sustained) treatment effects.

2.5. MEG

Further indications of ketamine’s role in regulating homeostatic balance have emerged based on differential and opposing effects in healthy volunteers and individuals with MDD, not only with fMRI (as noted above) but with MEG as well. One exploratory analysis using resting MEG gamma oscillatory power as a proxy marker for homeostatic balance of GABAergic system inhibition and excitatory glutamatergic neurotransmission found that individuals with MDD and healthy volunteers generally showed increases in gamma power post-ketamine compared to post-placebo (Nugent, Ballard, et al., 2019); interestingly, healthy volunteers had increased depressive symptoms up to 24h post-ketamine infusion. Furthermore, although a direct relationship between gamma power and depressive symptoms was not found, individuals with MDD who had lower pre-ketamine gamma power in several regions were likely to show greater improvement in depressive systems post-ketamine, while individuals with higher pre-ketamine gamma power in these regions had less acute improvement in depressive symptoms (Nugent, Ballard, et al., 2019). Although this effect was not observed beyond the 40-min post-infusion timepoint, the moderation of clinical response in MDD participants by baseline gamma power, coupled with the opposite effect of ketamine on depressive symptoms in MDD versus healthy participants, suggests that ketamine may indeed balance synaptic homeostasis in the glutamatergic and GABAergic systems. Building on this work, Nugent and colleagues sought to replicate this finding of increased gamma response at 230min and Day 1 in ketamine responders versus non-responders in a sample of 31 individuals with treatment-resistant MDD and 25 healthy volunteers (Nugent, Wills, et al., 2019). A significant difference in peak gamma power was seen in the depressed ketamine responders versus non-responders, implicating AMPA through-put in ketamine’s mechanism of antidepressant action.

In another study of individuals with treatment-resistant depression, Nugent and colleagues found that connectivity to limbic regions following ketamine administration was reduced compared to baseline, and that this occurred regardless of whether or not connectivity was abnormally increased or decreased at baseline relative to healthy volunteers (Nugent et al., 2016). Connectivity between the insulo-temporal independent components and the amygdala, which was abnormally elevated at baseline, was reduced by ketamine infusion to levels more in line with those seen in healthy volunteers, suggesting normalization.

Other MEG studies have evaluated the effects of ketamine on the neural correlates of cognitive and emotional function. In particular, two predictive biomarker studies of acute treatment response were conducted. One found that, 1 to 3 days before ketamine administration, MDD participants had increased rostral ACC activity in response to fearful faces, while healthy participants’ rostral ACC activity in response to the stimuli decreased (Salvadore et al., 2009); these increases in ACC activity were associated with rapid antidepressant response to ketamine in MDD participants. In the second MEG study, the same investigators reported that as working memory load increased, MDD participants with low baseline task-related beta activity in the pregenual ACC (pgACC) and low functional connectivity between the pgACC and amygdala had improved clinical response to ketamine within 4h of administration (Salvadore et al., 2010).

In order to better understand the modulating effects of glutamatergic transmission on antidepressant response to ketamine, Gilbert and colleagues compared MEG results obtained before the first ketamine infusion and 5–9h after both ketamine and placebo infusions in individuals with treatment-resistant MDD and healthy volunteers (Gilbert et al., 2018). Dynamic causal modeling (DCM) was used to measure changes in AMPA- and NMDA-mediated connectivity estimates using a simple model of somatosensory evoked responses. The authors found that ketamine’s antidepressant effects correlated with reduced NMDA and AMPA connectivity estimates in discrete extrinsic connections within the somatosensory cortical network (Gilbert et al., 2018). These findings suggest that AMPA- and NMDA-mediated glutamatergic signaling play a key role in antidepressant response to ketamine. A similar study by Gilbert and colleagues recently used resting-state MEG to examine electrophysiological correlates of suicidal ideation. In this study, gamma power in distinct regions in the anterior insula were found to be associated with suicidal ideation compared with depression. In the DCM of insula-ACC connectivity, ketamine lowered the membrane capacitance for superficial pyramidal cells. In addition, connectivity between the insula and ACC was associated with improvements in depressive symptoms (Gilbert, Ballard, Galiano, Nugent, & Zarate, 2020).

Finally, the plasticity effects of ketamine were also studied in 20 unmedicated individuals with treatment-resistant MDD who received a single, open-label, intravenous infusion of ketamine hydrochloride (0.5mg/kg) (Cornwell et al., 2012). MEG recordings were made approximately 3 days before and approximately 7h after the ketamine infusion, while participants passively received tactile stimulation to the right and left index fingers while resting (eyes closed). MDD participants with robust improvements in depressive symptoms 230min post-infusion (responders) exhibited increased cortical excitability within this antidepressant response window. Specifically, stimulus-evoked somatosensory cortical responses increased after infusion relative to pretreatment response in responders but not in treatment non-responders. The findings suggest that synaptic potentiation is critical for ketamine’s rapid antidepressant effects (Cornwell et al., 2012).

As the evidence reviewed above underscores (see Table 1), the findings from MEG studies with ketamine in depression are preliminary in nature and, as techniques for predicting treatment response to ketamine, not yet ready for routine clinical use. While most studies of this modality have examined acute treatment effects, a few are beginning to examine the relationship between neural activity and sustained antidepressant response to ketamine (7 days).

2.6. EEG

Further evidence of ketamine’s pro-plasticity effects comes from a recent EEG study that found that neural plasticity increased within the time frame of ketamine’s antidepressant effects. In a double-blind, active placebo-controlled, crossover trial, EEG-based long-term potentiation was recorded approximately 4h after a single intravenous dose of ketamine or active placebo (remifentanil) in 30 individuals with MDD. The investigators found that ketamine specifically increased visual long-term potentiation-mediated neural plasticity (Sumner et al., 2020).

As with MEG, the findings from EEG studies are preliminary and not yet ready for routine clinical use. However, it should be noted that EEG remains a particularly useful potential technology because it could be rapidly implemented into clinic settings to investigate real-world applicability.

2.7. Multimodal imaging studies

This section discusses studies that used multiple modalities (neuroimaging or electrophysiology and another biomarker) to explore antidepressant response to ketamine. A previous study from our laboratory found no correlation between smaller hippocampal volumes and improved antidepressant efficacy of ketamine in 55 individuals with MDD at any timepoint (from baseline to 230min, 1 day, and 1 week post-ketamine infusion); nevertheless, the same study did find a preliminary relationship when factoring in genotype of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) rs6265 genotype methionine (Met) allele (valine (Val)/Met or Met/Met). In Val/Val participants (n = 23), corrected left and right thalamic volume positively correlated with antidepressant response to ketamine at 230min post-infusion, although this finding did not reach statistical significance. In met carriers (n = 14), corrected left and right thalamic volume negatively correlated with antidepressant response to ketamine (Niciu et al., 2017). Another recent study by Woelfer and colleagues examined the relationship between ketamine response, BDNF levels, and resting-state functional connectivity in 53 healthy volunteers (Woelfer et al., 2019). The investigators observed higher relative levels of plasma BDNF 2 and 24 h post-ketamine compared to post-placebo. In addition, whole-brain regression revealed that change in BDNF levels 24 h post-ketamine was associated with resting-state functional connectivity in the dorsomedial PFC. The investigators suggested that these findings may reflect ketamine’s effects on synaptic plasticity.

Another study examined the relationship between subcortical brain volume, glucose metabolism, response to ketamine, and Shank3—a postsynaptic density protein involved in NMDA receptor tethering and dendritic spine rearrangement that is implicated in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder. Ortiz and colleagues found that higher baseline Shank3 levels predicted antidepressant response at Days 1, 2, and 3 and were associated with larger right amygdala volume. Higher baseline Shank3 levels also predicted increased glucose metabolism in the amygdala and hippocampus (Ortiz et al., 2015).

A recent study by Nugent and colleagues examined 30 participants with treatment-resistant depression and 26 healthy volunteers who received ketamine and underwent DTI, MRS, resting-state fMRI, and MEG (Nugent, Farmer, et al., 2019). Tracts connecting the sgACC and the left and right amygdala, as well as connections to the left and right hippocampus and thalamus, were examined as target areas. Reduced fractional anisotropy (FA) was observed in the studied tracts. Significant differences in the correlation between medial PFC glutamate concentrations and FA were also observed between MDD and healthy volunteers. Along tracts connecting the sgACC and right amygdala, a correlation was observed between FA and subsequent antidepressant response to ketamine infusion in MDD participants (Nugent, Farmer, et al., 2019).

Finally, McMillan and colleagues examined simultaneous pharmacological MRI (phMRI) and EEG during ketamine infusion in individuals with MDD (McMillan et al., 2020). EEG spectral analysis was used to help interpret BOLD signal changes with phMRI. The authors found that low beta and high gamma power time courses explained significant variance in the BOLD signal, and suggested that the decrease in sgACC BOLD signal was unrelated to antidepressant response to ketamine.

As reviewed above, studies examining neuroimaging markers of response to ketamine hold considerable promise (see Table 1). In addition, the study by McMillan and colleagues provides a clear example of how multimodal technologies may be used to interpret study findings. Nevertheless, small sample sizes, lack of reliable replicability, and mixed results all suggest that the scientific community should pay particular attention to the design of future studies; investigations that compare connectivity or other measures across different stages of depression are warranted to examine the potential of specific biomarkers as treatment efficacy markers. To date, multimodal technologies in the context of acute treatment effects of ketamine have mainly been used to better understand mechanism of action; thus, these modalities remain in the research realm.

3. Sleep and circadian markers of antidepressant response to ketamine

Sleep represents a promising area to evaluate markers of ketamine’s antidepressant effects. Sleep deprivation (SD)—in which depressed individuals are kept awake overnight with subsequent rapid improvements in mood—is arguably one of the only other rapid-acting antidepressants; however, SD-related improvements often dissipate after one night of sleep (Wirz-Justice & Benedetti, 2019).

Interestingly, SD and ketamine may share similar biological mechanisms, including altered glutamate/glutamine levels in the ACC followed by NMDA and AMPA receptor signaling coupled with downstream mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling changes (Benedetti et al., 2009; Bunney et al., 2015). Furthermore, there is potential overlap in circadian clock mechanisms between ketamine and SD; in one preclinical model, gene expression in the ACC of mice exposed to either low-dose ketamine or SD showed similar transcriptional responses related to neuroplasticity and the circadian clock (Orozco-Solis et al., 2017). Specifically, ketamine and SD overlapped in the expression of 64 genes, including Ciart, Per2, Npas4, Dbp, and Rorb, all of which are implicated in the circadian clock. Using neuronal cell culture (NG108–15), ketamine was also found to alter the expression of clock genes, specifically by inhibiting CLOCK:BMAL-mediated transcription (Bellet, Vawter, Bunney, Bunney, & Sassone-Corsi, 2011).

With regard to potential markers of response, sleep slow wave activity (SWA) has been linked to clinical depression phenotypes and may be a marker of both synaptic plasticity and homeostatic sleep regulation (Goldschmied & Gehrman, 2019; Tononi & Cirelli, 2003). Specifically, individuals with MDD appear to have reduced SWA, particularly in the first non-REM period (Armitage, Hoffmann, Trivedi, & Rush, 2000). Accordingly, antidepressant response to SD is associated with improvements in SWA on recovery sleep (Landsness, Goldstein, Peterson, Tononi, & Benca, 2011). Similar to the findings in SD, Duncan and colleagues found that, post-ketamine, SWA during the first non-REM episode increased from baseline in a sample of 30 individuals with treatment-resistant MDD (Duncan, Sarasso, et al., 2013). As another marker of neuronal plasticity, changes in BDNF at 230min and change in SWA were also correlated; exploratory analyses found that this relationship between BDNF and SWA only existed for those who responded to ketamine but not the non-responders (Duncan, Sarasso, et al., 2013). The same investigators found that a lower delta sleep ratio—another metric of sleep homeostasis calculated as the ratio of SWA in the first two non-REM sleep episodes—also predicted antidepressant response to ketamine at Day 1 (Duncan, Selter, Brutsche, Sarasso, & Zarate, 2013). Taken together, and in keeping with homeostatic theories of ketamine’s antidepressant effects, ketamine’s impact on sleep may also represent a temporary alteration in sleep homeostasis, thereby transiently relieving depressive symptoms (Duncan, Ballard, & Zarate, 2019). These homeostatic mechanisms underlying SWA and ketamine were elegantly summarized by Rantamaki and Kohtala in their ENCORE-D model (Rantamaki & Kohtala, 2020); their findings suggest that SWA and changes in synaptic strength underlie the sustained antidepressant effects of several rapid-acting antidepressants, including ketamine, SD, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

In addition to polysomnographic markers such as SWA, wrist-activity markers or actigraphy are indicators of circadian timekeeping over the course of the day. Timekeeping markers include parameter estimates of amplitude, acrophase (timing of peak), and mesor (central value) on a fitted sinusoidal curve summarizing 24-h activity counts. Studies have linked activity patterns such as phase delay (later acrophase) (Robillard et al., 2015), lower mesor (Hori et al., 2016), and lower amplitude (Wolff, Putnam, & Post, 1985) with current depressed state. Antidepressant response to SD has also been associated with phase advanced activity (Benedetti et al., 2007). In 51 individuals with MDD or bipolar depression, Duncan and colleagues found that ketamine was associated with decreased mesor compared to baseline and placebo (Duncan et al., 2017). Lower mesor and earlier phase at baseline were associated with antidepressant response to ketamine at Day 1. Furthermore, at Day 1, responders demonstrated advanced activity timing compared to non-responders. For responders at Day 3—that is, those individuals who still had a 50% improvement in Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) rating scale scores on the third day after ketamine administration—response was associated with increased mesor and amplitude compared to non-responders. Building on this work, a subsequent analysis of antidepressant response found that those who experienced a brief antidepressant response—that is, those who responded to ketamine at Day 1 but not at Day 3—had decreased amplitude at baseline and phase advance on Day 1 (Duncan et al., 2018). Those who had an antidepressant response at both Day 1 and Day 3 had phase advanced activity at baseline and increased amplitude on Days 1 and 3.

The findings reviewed above implicate two core sleep processes in ketamine’s antidepressant effects: sleep homeostasis (Process S) and the circadian clock (Process C) (Duncan et al., 2019). Further work is needed to explore the relationship between sleep and antidepressant response to ketamine at the genetic, molecular, circuit, and behavioral levels. It should be noted here that disturbed sleep may be a particularly important marker for suicide risk (Pigeon, Pinquart, & Conner, 2012). Wakefulness in the 4amhour has been linked to next-day suicidal thoughts (Ballard et al., 2016), and a suicidal ideation response to ketamine was found to be associated with improvements in wakefulness as compared to suicidal ideation non-response (Vande Voort et al., 2017).

In summary, the evaluation of depression and certain depressive symptom clusters—such as suicidal thoughts with sleep, activity markers, and polysomnography—may be a fruitful area of research in the context of ketamine. While these studies have mostly been used to examine acute treatment response to ketamine, they have nevertheless provided valuable information into the putative mechanistic processes that underlie ketamine’s mechanism of action. However, while this is a promising area of biomarker development, the clinical usefulness of sleep and circadian markers for assessing response to ketamine remains exploratory in nature.

4. Immunologic biomarkers of response to ketamine

The emerging field of psychoneuroimmunology is based on mounting evidence that some neuropsychiatric illnesses arise, in part, from a dysregulated immune response (Haroon, Raison, & Miller, 2012). Stress induces an inflammatory response that is normally self-limited in healthy individuals through negative feedback by the glucocorticoid system. However, prolonged episodes of inflammatory stress promote glucocorticoid resistance (Pariante, 2017), which results in persistent elevations of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and immune activation (Cohen et al., 2012). This process of chronic inflammatory burden directly alters brain structure and function, such as reducing dendritic length in the hippocampus and causing related memory deficits in animal models (McEwen, Nasca, & Gray, 2016).

Notably, ketamine is associated with anti-inflammatory effects in humans (Dale, Somogyi, Li, Sullivan, & Shavit, 2012; Du, Huang, Yu, & Zhao, 2011) and animals (Tan, Wang, Chen, Long, & Zou, 2017; Yang et al., 2013), suggesting that its ability to modulate the inflammatory state may play a role in its rapid antidepressant effects. While the precise mechanisms of ketamine’s anti-inflammatory properties remain unclear, evidence implicates the involvement of the gut microbiome (Getachew et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2017), NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated upregulation of AMPA receptors (Li et al., 2019), attenuation of dendritic cell maturation (Ohta, Ohashi, & Fujino, 2009), and priming of TH1-type immune response (Ohta et al., 2009). Preliminary reports also suggest a link between ketamine and changes in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (Kido et al., 2019), a newly recognized hematologic biomarker of peripheral inflammation potentially relevant for depressive disorders (Aydin Sunbul et al., 2016; Mazza et al., 2018).

However, the clinical relevance of ketamine-induced inflammatory modulation remains unclear. On the one hand, preclinical studies support the notion that response to ketamine is at least partly moderated by baseline inflammatory parameters, including C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), and IL-6 (Walker et al., 2015); clinical evidence also supports the role of adipokines in humans (Machado-Vieira et al., 2017). Response to ketamine also appears to be moderated by baseline body mass index (Niciu, Luckenbaugh, Ionescu, Guevara, et al., 2014), which has been linked to inflammatory burden and risk of depressive relapse (Bond et al., 2016). On the other hand, it is less clear whether treatment response is mediated by ketamine-induced alterations in inflammatory cytokine levels. Response to ketamine in individuals with treatment-resistant depression has been linked to shifts in IL-6 and TNF-alpha levels (Chen et al., 2018b) as well as increased osteoprotegerin/receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) ratio (Kadriu et al., 2018; Zhang, Ma, Dong, & Hashimoto, 2018); however, other studies confirmed the link between treatment-resistant depression and elevated baseline IL-6 levels (Kiraly et al., 2017) but found no association between response to ketamine and shifts in inflammatory markers (Kiraly et al., 2017; Park et al., 2016). In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of individuals with MDD or bipolar disorder who received a single intravenous infusion of ketamine, Park and colleagues found no clear evidence of cytokines associated with antidepressant response to ketamine (Park et al., 2016). Of eight cytokines examined, only sTNFR1 was associated with depression at baseline. Cytokine changes did not correlate with changes in mood nor predict mood changes associated with ketamine administration. This study suggests that cytokines are not a primary mechanism of ketamine’s antidepressant effects (Park et al., 2016).

Dimensional analysis of clinical outcomes may be needed to unmask any putative mediating effects of biomarkers and response to ketamine (Ballard et al., 2018). Regardless, a scenario in which inflammatory markers moderate but do not mediate response to ketamine supports the notion that the mechanisms driving the neurobiology of depression do not necessarily align with those that underlie response to ketamine. In other words, reversing baseline immune dysregulation may not suffice for treatment response, even if this dysregulation is involved in the neurobiology of treatment-resistant depression as an indirect baseline predictor of response to ketamine.

5. Metabolic/bioenergetic biomarkers

5.1. The kynurenine pathway

The kynurenine (KYN) pathway is an alternate tryptophan (TRP) break-down pathway that, under physiological conditions, metabolizes TRP (>95%) into KYN and an array of downstream neuroactive metabolites (Michels et al., 2018). The TRP to KYN conversion process is enabled by two rate-limiting enzymes: tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). Once in the brain, KYN is processed by either astrocytes or microglia to produce distinct neuroactive compounds that have been shown to alter downstream synaptic glutamatergic neurotransmission (Miller, 2013) and facilitate communication between the brain and the immune system (Schwarcz & Stone, 2017). Because the KYN pathway appears to represent the conceptual confluence of immunologic, monoaminergic, and glutamatergic theories of depression (Savitz, 2020; Schwarcz & Stone, 2017), it is plausible that the KYN pathway contains putative biomarkers of response to ketamine.

In humans, studies have noted KYN pathway aberrations in the pathophysiology of treatment-resistant MDD (Moaddel et al., 2018; Savitz et al., 2015) as well as bipolar depression (Kadriu et al., 2019; Murata et al., 2019). Savitz and colleagues found that KYN pathway alterations were associated with volumetric changes in various brain areas, including volumetric hippocampal and amygdala changes in both MDD and bipolar depression (Savitz, 2020). In another study, Kadriu and colleagues found that in individuals with treatment-resistant bipolar depression, ketamine reduced IDO levels, reduced the quinolinic acid (QA)/KYN ratio (without changing QA levels), and increased levels of KYN and kynurenic acid (KYNA) (Kadriu et al., 2019). The same study found that baseline levels of proinflammatory cytokines and behavioral measures predicted KYN pathway changes post-ketamine (Kadriu et al., 2019). In addition, Moaddel and colleagues found that individuals with treatment-resistant MDD who responded to ketamine exhibited decreased plasma KYN levels and increased arginine levels 4h post-ketamine infusion (Moaddel et al., 2018). Finally, Zhou and colleagues found that individuals with MDD or bipolar depression who received repeated ketamine infusions exhibited early increases in serum KYNA levels, and that the KYNA/KYN ratio within 24h predicted sustained antidepressant effects at 24h, 13 days, and 26 days (Zhou et al., 2018).

Taken together, the evidence reviewed above suggests that key neuroactive players in the KYN pathway—such as IDO, KYNA, QA, and others—have tremendous potential not only as novel therapeutic targets for intervention in depression but also as key prognostic biomarkers of treatment response to novel therapeutics like ketamine.

5.2. d-Serine

The glycine binding site modulator d-serine is an endogenous co-agonist of the NMDA receptor with preferential affinity to the glycine site. It plays a key role in long-term potentiation (Henneberger, Papouin, Oliet, & Rusakov, 2010), neurotransmission (Billiard, 2012), plasticity (Billiard, 2012), and NMDA-induced neurotoxicity (Papouin et al., 2012). In individuals with treatment-resistant MDD, Moaddel and colleagues demonstrated that peripheral plasma baseline d-serine concentrations were much lower in ketamine responders compared to non-responders (Moaddel et al., 2015). In addition, low baseline d-serine plasma concentrations predicted improved antidepressant response to ketamine (Moaddel et al., 2015). However, no newer studies have examined the link between d-serine and antidepressant response to ketamine.

6. Neurotrophic/plastic biomarkers

BDNF has been extensively studied in the pathophysiology of depression. In fact, early preclinical studies attempting to model depressive-like symptoms found reduced BDNF expression in the brains of animals exposed to stress (Duman & Monteggia, 2006; Lee & Kim, 2010). Mounting evidence suggests that response to rapid-acting antidepressants is moderated, and possibly mediated, by neurotrophic factors. For instance, Laje and colleagues found that the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism was associated with impaired NMDA receptor transmission as well as impaired synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus, suggesting that decreased BDNF expression may be associated with higher susceptibility to depression and decreased response to medications, including ketamine (Laje et al., 2012). Haile and colleagues found that this response correlated with increased BDNF levels at 240min post-ketamine infusion (Haile et al., 2014). Finally, Niciu and colleagues examined the effects of BDNF genetic variation on the relationship between subcortical volumes and ketamine’s antidepressant efficacy and found that in individuals with MDD carrying the Met allele (Val/Met or Met/Met) on the rs6265 SNP of BDNF, smaller bilateral thalamic volumes were associated with increased antidepressant response 230min post-ketamine, an effect not observed in those carrying the Val/Val genotype (Niciu et al., 2017).

As the evidence reviewed above underscores, the study of peripheral biomarkers (i.e., immunologic, metabolic/bioenergetic, d-serine, neurotrophic/plastic) is an area of enormous interest for several reasons, including ease of access and the theoretic link with proximal processes believed to be involved with ketamine’s mechanism of action. However, the relationship between peripheral and central biomarkers, even at the extracellular/intracellular level, remains unclear. As such, peripheral biomarkers are not yet clinically useful and remain an area of further exploration.

7. Genetic/epigenetic markers of response to ketamine

To date, genome-wide association studies of response to ketamine in treatment-resistant MDD or bipolar disorder have been extremely under-powered. Preliminary studies identified no single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that surpassed the genome-wide threshold for significance, although Guo and colleagues found several genes of interest, including RASGFR2, ROBO2, SPRED2, SEC11A, KRASP1, and FAM83B (Guo et al., 2018). In addition, Ficek and colleagues recently used whole-genome microarray profiling to identify patterns of numerous gene transcripts (e.g., Dusp1, Per1, and Fkbp5) whose expression was altered in the brain post-ketamine (Ficek et al., 2016), thus providing novel directions for the molecular classification of ketamine. The transcriptional profile of ketamine reflects its multi-target pharmacological nature. Interestingly, this research revealed similarities in the transcriptional effects of ketamine and those of monoaminergic antidepressants (particularly fluoxetine), suggesting a degree of confluence in the downstream molecular impact of their mechanisms of antidepressant action (Ficek et al., 2016).

Pharmacogenomic profiling of individual genetic variation in the CYP450 enzyme and its effects on ketamine metabolism may also represent a step toward personalized medicine and stratification of individuals who respond to ketamine. Ketamine exhibits extensive oxidative first-pass metabolism in the liver via two main cytochrome (CYP) enzymes: CYP3A and CYP2B6 (Peltoniemi, Hagelberg, Olkkola, & Saari, 2016). However, evidence regarding the impact of genetic variants of CYP450 on response to ketamine has, to date, been mixed. While CYP450 variants do not seem to predict clinical response to ketamine (Zarate et al., 2012), a recent study suggested that the activity of hepatic CYP450 isoforms contributes to sustained antidepressant-like response to ketamine (Nguyen et al., 2019).

As with other pharmacogenetic studies, these findings are preliminary in nature and will require that many participants be studied before definitive conclusions can be made.

8. Non-neurobiological biomarkers

8.1. Clinical predictors

Several clinical predictors have been examined in relationship to ketamine’s antidepressant effects, including vital signs such as heart rate and blood pressure. In 2014, Luckenbaugh and colleagues conducted a secondary data analysis of several potential predictors of antidepressant response to ketamine (n = 108) (Niciu, Luckenbaugh, Ionescu, Guevara, et al., 2014). Higher body mass index correlated with greater improvement in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) scores at 230min and Day 1, but not at Day 7. Family history of alcohol use disorder in a first-degree relative has also been associated with greater improvement in depressive symptoms at Days 1 and 7. The overall statistical model explained 13%, 23%, and 36% of the percent change in variance in HAM-D score at 230min, Day 1, and Day 7, respectively (Niciu, Luckenbaugh, Ionescu, Guevara, et al., 2014). Change in manic symptoms as measured by the Young Mania Rating Scale, change in psychotic symptoms as assessed by positive symptoms scores on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, and change in diastolic blood pressure, systolic blood pressure, and heart rate at 40min post-infusion were not associated with later antidepressant response to ketamine (Luckenbaugh et al., 2014). In contrast, dissociative symptoms as measured by the CADSS were associated with antidepressant improvement at both 230min and Day 7 post-infusion. Although statistically significant, the CADSS change from baseline explained only a small fraction of the variance in antidepressant response to ketamine. Taken together, the evidence suggests that clinical variables explain some of the variance associated with antidepressant response to ketamine; however, the effects are small.

8.2. Neurocognitive studies

Murrough and colleagues examined the relationship between antidepressant response to ketamine and neurocognitive functioning, as assessed via the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB). They found that individuals with MDD who responded to ketamine at 24h post-treatment had poorer baseline neurocognitive performance than non-responders and, in particular, slower processing speed (Murrough et al., 2013). Building on this work, the same group addressed this issue in a larger study of 62 medication-free MDD participants who underwent neurocognitive assessments before and after a single intravenous infusion of ketamine (0.5mg/kg) or midazolam. As with their previous study, the investigators found that reduced processing speed at baseline was associated with better antidepressant response to ketamine (Murrough, Burdick, et al., 2015). Given that only a few such studies have investigated the acute and long-term safety of ketamine and moderators of treatment response, additional studies are urgently needed.

Evidence drawn from studies of non-neurobiological biomarkers suggests that future studies are needed to compare clinical versus biological markers of treatment response to ketamine and integrate these in an attempt to identify subgroups of responders to ketamine.

9. Conclusion

The field of psychiatry is undergoing an exciting paradigm shift toward early identification and intervention, which is likely to minimize both the burden associated with severe mental illnesses as well as their duration. In this context, the rapid-acting antidepressant ketamine has revolutionized our understanding of antidepressant response and greatly expanded the pharmacologic armamentarium for treatment-resistant depression. Efforts to characterize biomarkers of ketamine response support the growing emphasis on early identification, which would allow clinicians to identify biologically enriched subgroups with treatment-resistant depression who are more likely to benefit from ketamine therapy. Toward that end, an emerging concept is that the rational use of combined biomarkers across different modalities—rather than single biomarkers in isolation—can optimize clinical outcomes by enhancing biological target engagement.

This chapter reviewed several exciting predictive and moderator/mediator biomarkers of response to ketamine. However, this body of work remains in its infancy. Broadly, the vast majority of biomarker studies conducted with ketamine in depression have examined its acute treatment effects, and few replication studies have been performed. To date, all of the biomarkers reviewed above remain largely exploratory in nature, and none are ready for clinical use. That being said, important work is underway to explore these biomarkers across modalities. Such multimodal studies are particularly valuable because they may ultimately illuminate neurobiological signals that can be observed with less expensive and invasive treatments (e.g., neurocognitive testing/EEG versus PET/fMRI). While more work is clearly needed to delineate and validate biomarkers of response to ketamine in order to ensure the field’s ongoing advances toward personalized care, an improved understanding of the underlying neurobiology across biomarkers will eventually allow investigators to recommend scalable markers that can be used in the clinic.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the 7SE research unit and staff for their support.

Conflict of interest statement

Funding for this work was supported by the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health (IRP-NIMH-NIH; ZIAMH002857), by a NARSAD Independent Investigator Award to Dr. Zarate, and by a Brain and Behavior Mood Disorders Research Award to Dr. Zarate. Dr. Zarate is listed as a co-inventor on a patent for the use of ketamine in major depression and suicidal ideation; as a co-inventor on a patent for the use of (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine, (S)-dehydronorketamine, and other stereoisomeric dehydro and hydroxylated metabolites of (R,S)-ketamine metabolites in the treatment of depression and neuropathic pain; and as a co-inventor on a patent application for the use of (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine and (2S,6S)-hydroxynorketamine in the treatment of depression, anxiety, anhedonia, suicidal ideation, and post-traumatic stress disorders. He has assigned his patent rights to the U.S. government but will share a percentage of any royalties that may be received by the government. All other authors have no conflict of interest to disclose, financial or otherwise.

List of abbreviations

- ACC

anterior cingulate cortex

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- BOLD

blood oxygen level-dependent

- CADSS

Clinician Administered Dissociative States Scale

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CYP

cytochrome

- DCM

dynamic causal modeling

- DMN

default mode network

- DM/DA-PFC

dorsomedial/dorsal anterolateral prefrontal cortex

- DTI

diffusion tensor imaging

- ECT

electroconvulsive therapy

- EEG

electroencephalography

- FA

fractional anisotropy

- FDG

fluorodeoxyglucose

- fMRI

functional magnetic resonance imaging

- GABA

gamma aminobutyric acid

- GBC

global brain connectivity

- GBCr

global brain connectivity with global regression

- HAM-D

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

- IDO

indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

- IL

interleukin

- KYN

kynurenine

- KYNA

kynurenic acid

- MADRS

Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale

- MCCB

MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- MEG

magnetoencephalography

- Met

methionine

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MRS

magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- mTOR

mechanistic target of rapamycin

- NMDA

N-methyl-d-aspartate

- PET

positron emission tomography

- pgACC

pregenual ACC

- phMRI

pharmacological magnetic resonance imaging

- QA

quinolinic acid

- RANKL

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand

- rMRGlu

regional cerebral glucose metabolism

- SD

sleep deprivation

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- SWA

slow wave activity

- TDO

tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TRP

tryptophan

- Val

valine

References

- Abdallah CG, De Feyter HM, Averill LA, Jiang L, Averill CL, Chowdhury GMI, et al. (2018). The effects of ketamine on prefrontal glutamate neurotransmission in healthy and depressed subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology, 43, 2154–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah CG, Jackowski A, Salas R, Gupta S, Sato JR, Mao X, et al. (2017). The nucleus accumbens and ketamine treatment in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42, 1739–1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah CG, Salas R, Jackowski A, Baldwin P, Sato JR, & Mathew SJ (2015). Hippocampal volume and the rapid antidepressant effect of ketamine. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 29(5), 591–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage R, Hoffmann R, Trivedi M, & Rush AJ (2000). Slow-wave activity in NREM sleep: Sex and age effects in depressed outpatients and healthy controls. Psychiatry Research, 95(3), 201–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin Sunbul E, Sunbul M, Yanartas O, Cengiz F, Bozbay M, Sari I, et al. (2016). Increased neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in patients with depression is correlated with the severity of depression and cardiovascular risk factors. Psychiatry Investigation, 13(1), 121–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard ED, Vande Voort JL, Bernert RA, Luckenbaugh DA, Richards EM, Niciu MJ, et al. (2016). Nocturnal wakefulness is associated with next-day suicidal ideation in major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(6), 825–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard ED, Yarrington JS, Farmer CA, Lener MS, Kadriu B, Lally N, et al. (2018). Parsing the heterogeneity of depression: An exploratory factor analysis across commonly used depression rating scales. Journal of Affective Disorders, 231, 51–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellet MM, Vawter MP, Bunney BG, Bunney WE, & Sassone-Corsi P (2011). Ketamine influences CLOCK:BMAL1 function leading to altered circadian gene expression. PLoS ONE, 6(8), e23982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti F, Calabrese G, Bernasconi A, Cadioli M, Colombo C, Dallaspezia S, et al. (2009). Spectroscopic correlates of antidepressant response to sleep deprivation and light therapy: A 3.0 tesla study of bipolar depression. Psychiatry Research, 173(3), 238–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti F, Dallaspezia S, Fulgosi MC, Barbini B, Colombo C, & Smeraldi E (2007). Phase advance is an actimetric correlate of antidepressant response to sleep deprivation and light therapy in bipolar depression. Chronobiology International, 24(5), 921–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billiard JM (2012). D-Amino acids in brain neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity. Amino Acids, 43, 1851–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond DJ, Andreazza AC, Hughes J, Dhanoa T, Torres IJ, Kozicky JM, et al. (2016). Association of peripheral inflammation with body mass index and depressive relapse in bipolar disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 65, 76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]