Abstract

Background

Strongyloidiasis is an intestinal parasitic infection mainly caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. Although it is a predominant parasite in tropics and subtropics where sanitation and hygiene are poorly practiced, the true prevalence of strongyloidiasis is not known due to low-sensitivity diagnostic methods.

Objective

This systematic review and meta-analysis is aimed at determining the pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis in African countries, stratified by diagnostic methods, study settings, and patients.

Methods

Cross-sectional studies on strongyloidiasis published in African countries from the year 2008 up to 2018 in PubMed and Google Scholar databases and which reported at least one Strongyloides spp. infection were included. Identification and screening of eligible articles were also done. Articles whose focus was on strongyloidiasis in animals, soil, and foreigners infected by Strongyloides spp. in Africa were excluded. The random effects model was used to calculate the pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis across African countries as well as by diagnostic methods and study settings. The heterogeneity between studies was also computed.

Result

A total of 82 studies were included. The overall pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis was 2.7%. By individual techniques, the pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis was 0.4%, 1.0%, 3.4%, 9.3%, 9.6%, and 19.4% by the respective direct saline microscopy, Kato-Katz, formol ether concentration, polymerase chain reaction, Baermann concentration, and culture diagnostic techniques. The prevalence rates of strongyloidiasis among rural community, school, and health institution studies were 6.8%, 6.4%, and 0.9%, respectively. The variation on the effect size comparing African countries, diagnostic methods, study settings, and patients was significant (P ≤ 0.001).

Conclusions

This review shows that strongyloidiasis is overlooked and its prevalence is estimated to be low in Africa due to the use of diagnostic methods with low sensitivity. Therefore, there is a need for using a combination of appropriate diagnostic methods to approach the actual strongyloidiasis rates in Africa.

1. Introduction

Strongyloides stercoralis is one of the soil-transmitted helminths (STHs) that cause strongyloidiasis. There are more than 60 species in the genus which parasitize the duodenum of the small intestine of humans and domestic mammals [1]. Only two species S. stercoralis and S. fuelleborni are known to infect human beings. Strongyloides stercoralis is distributed in tropical and subtropical areas whereas S. fuelleborni infection is found in Papua New Guinea and sporadically in Africa [2].

The true prevalence of strongyloidiasis is underestimated and underreported due to the use of diagnostic methods with poor sensitivity [3]. An estimated 370 million strongyloidiasis occur globally [4], being 90% of them in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, Latin America, Oceanian countries, and the Caribbean islands and is related to poor sanitation and hygiene practices [5]. Studies showed that high numbers of strongyloidiasis occur among children [6] and immunocompromised individuals [7]. Several factors including malnutrition, autoimmune diseases, and taking corticosteroid drugs that impaired the immune system may contribute for the high prevalence of strongyloidiasis [8].

In developing countries, the risk of acquiring strongyloidiasis is higher in rural dwellers, having low socioeconomic status [9] and poor sanitation infrastructures [10]. Infection ranges from asymptomatic to life-threatening clinical manifestations depending on the level of immunity [11]. The infection appears when the filariform larva enters the human body through skin penetration and crosses the lung during larva migration, and the adult reaches the small intestine. The larvae may cause skin rashes, dry cough, and recurrent sore throat whereas the adult stage of the parasite may also cause abdominal pain, loss of appetite, diarrhea, blood in stool, epigastric pain, and bloating, but most frequently, the infection is asymptomatic [12].

Strongyloidiasis is detected by microscopic-based diagnostic methods like direct saline microscopy (DSM) [3], formol ether concentration technique (FECT) [13], Baermann concentration technique (BCT) [14], agar plate technique (APT) [15], and immunological [16] and molecular-based techniques [17].

The Baermann concentration technique may increase the detection rate of strongyloidiasis by 3.6-4 times compared to the FECT or DSM technique [18]. In the same way, serological assays [16] and real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) techniques have shown to be more sensitive diagnostic tools for S. stercoralis detection [17].

The sensitivity of BCT, APT, RT-PCR, and ELISA is good, but not enough. Moreover, they have limitations for application in countries of poor resource in Africa. Because of that, a combination of techniques is the recommended approach for diagnosing the infection. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis is aimed at providing an overview of the prevalence of strongyloidiasis across African countries, stratified by diagnostic methods, study settings, and patients.

2. Materials and Methods

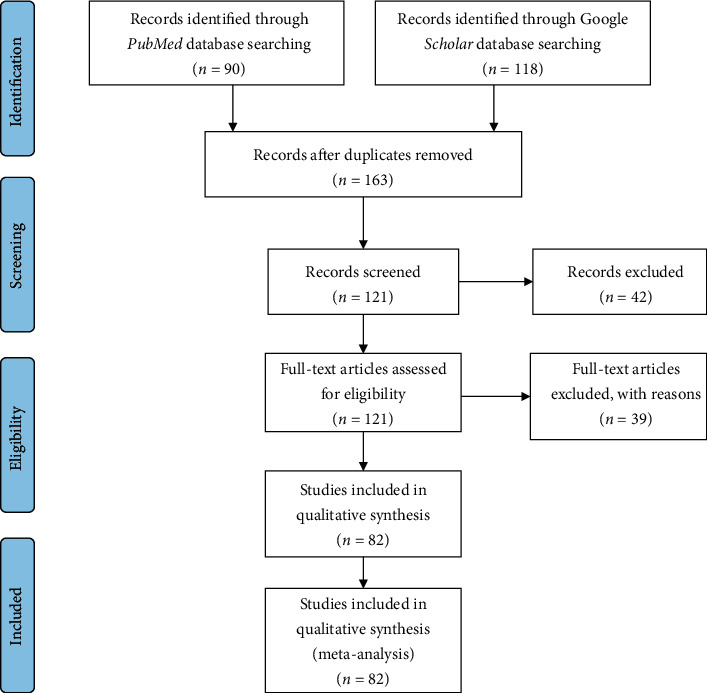

A search on the databases PubMed and Google Scholar was done for studies written in English from the year 2008 up to 2018. Keywords used in the search were “Strongyloidiasis,” “Strongyloides,” “Strongyloides stercoralis,” and “Soil-transmitted helminths” in each African country. The search for electronic data of studies was conducted between July 2019 and August 2019. Identification, screening, and checking the eligibility and the inclusion of the relevant studies were done following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) (Figure 1). The articles extracted from the two databases were first screened to remove duplication. Furthermore, the articles were screened by reading their abstracts and the full articles and then the articles which did not investigate the prevalence of strongyloidiasis.

Figure 1.

Overview of search methods of article inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

All cross-sectional studies from 2008 to 2018 conducted in African countries among patients or any participants in Africa and diagnosed by DSM, KK, FECT, BCT, culture, PCR, or a combination of these diagnostic techniques and obtained at least one positive for Strongyloides spp. were included. Including only PubMed and Google Scholar databases was the limitation.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

All studies on strongyloidiasis in animals, soil, foreigners in African countries or imported cases, nondefined study population, sample sources other than stool, analysis of S. stercoralis-positive cases only, method comparisons, case studies, cohort studies, duplications, articles conducted before the year 2008, and review articles done in African countries were excluded. The suitability of all studies according to the defined criteria was judged independently by two different authors. Any differences in judgment were resolved by discussion among the authors.

For each selected paper, the following information was recorded: number of infected individuals, number of examined individuals, country name, types of diagnostic method used, study setting where date were collected, and types of disease recorded in health institution. The pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis in African countries as well as by each diagnostic method, study settings, and among patients was computed using a random effects model.

The meta-analysis was performed using comprehensive meta-analysis 2.2 software (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA). The pooled overall prevalence of strongyloidiasis at 95% confidence interval (CI) in African countries was calculated using a random effects model. The pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis by diagnostic methods, study settings, and patients was calculated in the subgroup analysis. The forest plot was reported, and separate meta-analyses were performed to evaluate the effect of diagnostic methods, study settings, and patients in health institutions with strongyloidiasis. Heterogeneity (the difference between studies) by country, diagnostic methods, study settings, and among patients was assessed using Cochran (Q) value, P value, and I2 and visual inspection of the forest plot. The level of significance for all tests was P ≤ 0.001. Publication bias that occurs in published studies was checked by considering effect size symmetry on funnel plot (a scatter plot of estimates). Absence of bias is presented by shape like a funnel.

3. Result

A total of 208 (90 from PubMed and 118 from Google Scholar databases) studies were identified. One hundred sixty-three studies were screened and recorded after duplications removed. One hundred twenty-one studies were found to be eligible after full-text assessment, and finally, 82 studies were included in qualitative analysis (Figure 1).

3.1. Prevalence of Strongyloidiasis

Twenty African countries having strongyloidiasis research reports and fulfilling the inclusion criteria were involved with the total participants being 96,069 (Table 1).

Table 1.

The main characteristics of the included articles.

| Authors' information and reference | Diagnostic methods | Study settings | S. stercoralis Pos (n, %) | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dacal et al., 2018, Angola [19] | PCR | School | 75 (21.4) | 351 |

| Bocanegra et al., 2015, Angola [20] | FECT | School | 1 (0.07) | 1425 |

| de Alegrıa et al., 2017, Angola [21] | BCT, FECT | School | 28 (12.2) | 230 |

| Karou et al., 2011, Burkina Faso [22] | DSM | H/institution | 6 (0.05) | 11,728 |

| Bopda et al., 2016, Cameroon [23] | KK | H/institution | 7 (2.1) | 334 |

| Nsagha et al., 2016, Cameroon [11] | FECT | H/institution | 2 (0.7) | 300 |

| Kuete et al., 2015, Cameroon [24] | FECT | H/institution | 4 (0.9) | 428 |

| Becker et al., 2015, Côte d'Ivoire [25] | BCT, culture, PCR | Community | 56 (21.9) | 256 |

| Glinz et al., 2010, Côte d'Ivoire [26] | BCT, culture | School | 68 (27.1) | 251 |

| Rayan et al., 2011, Egypt [27] | BCT, FECT, culture, PCR | H/institution | 18 (15.7) | 115 |

| Roka et al., 2013, Equatorial Guinea [28] | FECT | H/institution | 28 (10.3) | 273 |

| Roka et al., 2012, Equatorial Guinea [29] | FECT | H/institution | 23 (8.8) | 260 |

| Amor et al., 2016, Ethiopia [6] | BCT, FECT, PCR | School | 82 (20.7) | 396 |

| Abdia et al., 2017, Ethiopia [30] | FECT | School | 3 (0.7) | 408 |

| Ramos et al., 2014, Ethiopia [31] | DSM | H/institution | 92 (0.3) | 32191 |

| Zeynudin et al., 2013, Ethiopia [32] | FECT | H/institution | 6 (6.6) | 91 |

| Assefa et al., 2009, Ethiopia [33] | FECT | H/institution | 28 (7.4) | 378 |

| Wegayehu et al., 2013, Ethiopia [34] | FECT | Community | 51 (5.9) | 858 |

| Huruy et al., 2011, Ethiopia [35] | DSM | H/institution | 12 (3.1) | 384 |

| Gedle et al., 2015, Ethiopia [36] | FECT | H/institution | 5 (1.6) | 305 |

| Abera et al., 2013, Ethiopia [37] | FECT | School | 27 (3.4) | 788 |

| Derso et al., 2016, Ethiopia [38] | DSM | H/institution | 6 (1.6) | 384 |

| Fekadu et al., 2013, Ethiopia [39] | FECT | H/institution | 36 (10.5) | 343 |

| Abate et al., 2013, Ethiopia [40] | FECT | H/institution | 8 (2.0) | 410 |

| Alemu et al., 2017, Ethiopia [41] | FECT | H/institution | 4 (1.8) | 220 |

| Teklemariam et al., 2013, Ethiopia [42] | FECT | H/institution | 15 (4.0) | 371 |

| Legesse et al., 2010, Ethiopia [43] | FECT | School | 1 (0.3) | 381 |

| Hailu et al., 2015, Ethiopia [44] | FECT | H/institution | 5 (0.05) | 100 |

| Nyantekyi et al., 2010, Ethiopia [45] | FECT | Community | 38 (13.2) | 288 |

| Chala, 2013, Ethiopia [46] | DSM | H/institution | 73 (1.2) | 6342 |

| M'bondoukwé et al., 2018, Gabon [47] | DSM | Community | 10 (3.7) | 270 |

| Janssen et al., 2015, Gabon [48] | Culture | H/institution | 10 (4.0) | 252 |

| M'bondoukwé et al., 2016, Gabon [49] | DSM | H/institution | 1 (1.0) | 101 |

| Adu-Gyasi et al., 2018, Ghana [50] | FECT | Community | 14 (0.9) | 1569 |

| Nkrumah et al., 2011, Ghana [51] | DSM | Hospital | 6 (0.6) | 1080 |

| Forson et al., 2017, Ghana [52] | FECT | School | 1 (0.3) | 300 |

| Yatich et al., 2009, Ghana [53] | BCT | H/institution | 29 (3.9) | 746 |

| Sam et al., 2018, Ghana [54] | FECT | School | 20 (5.1) | 394 |

| Cunningham et al., 2018, Ghana [55] | PCR | Community | 5 (1.1) | 448 |

| Kagira et al., 2011, Kenya [56] | DSM | H/institution | 3 (9.7) | 31 |

| Walson et al., 2010, Kenya [57] | FECT | Community | 20 (1.3) | 1541 |

| Arndt et al., 2013, Kenya [58] | FECT | Community | 5 (3.3) | 153 |

| Meurs et al., 2017, Mozambique [59] | FECT, BCT, PCR | Community | 147 (48.5) | 303 |

| Cerveja et al., 2017, Mozambique [60] | DSM | H/institution | 5 (1.3) | 371 |

| Chukwuma et al., 2009, Nigeria [61] | FECT | School | 13 (5.9) | 220 |

| Uhuo et al., 2011, Nigeria [62] | FECT | School | 4 (0.5) | 800 |

| Wosu and Onyeabor, 2014, Nigeria [63] | FECT | School | 11 (3.6) | 304 |

| Simon-oke et al., 2014, Nigeria [64] | DSM | School | 23 (12.8) | 180 |

| Adekolujo et al., 2015, Nigeria [65] | FECT | H/institution | 4 (0.6) | 717 |

| Olusegun et al., 2011, Nigeria [66] | DSM | School | 2 (0.7) | 304 |

| Abaver et al., 2011, Nigeria [67] | FECT | H/institution | 3 (2.5) | 119 |

| Ivoke et al., 2017, Nigeria [68] | FECT | H/institution | 8 (1.0) | 797 |

| Ojurongbe et al., 2018, Nigeria [69] | FECT | H/institution | 2 (1.0) | 200 |

| Emeka, 2013, Nigeria [70] | FECT | School | 28 (11.0) | 255 |

| Esiet and Edet, 2017, Nigeria [71] | FECT | School | 46 (4.4) | 1055 |

| Manir et al., 2017, Nigeria [72] | FECT | School | 10 (4.0) | 252 |

| Onyido et al., 2016, Nigeria [73] | FECT | School | 1 (0.8) | 120 |

| Abah and Arene, 2015, Nigeria [74] | FECT | School | 273 (7.1) | 3826 |

| Damen et al., 2010, Nigeria [75] | FECT | School | 34 (6.8) | 500 |

| Akinbo et al., 2010, Nigeria [76] | FECT | H/institution | 23 (1.2) | 2000 |

| Ojurongbe et al., 2014, Nigeria [77] | FECT | School | 6 (3.7) | 162 |

| Amoo et al., 2018, Nigeria [78] | FECT | H/institution | 10 (4.3) | 231 |

| Alli et al., 2011, Nigeria [79] | FECT | H/institution | 4 (1.1) | 350 |

| Eke et al., 2015, Nigeria [80] | FECT | School | 63 (13.1) | 480 |

| Auta et al., 2013, Nigeria [81] | FECT | School | 12 (4.2) | 283 |

| Aniwada et al., 2016, Nigeria [82] | FECT | School | 10 (1.2) | 859 |

| Umar and Bassey et al., 2010, Nigeria [83] | Culture | School | 104 (37.1) | 280 |

| Tuyizere et al., 2018, Rwanda [84] | Culture | Community | 94 (17.4) | 539 |

| Ferreira et al., 2015, Sao Tome and Principe [85] | FECT | Community | 11 (2.5) | 444 |

| Sow et al., 2017, Senegal [86] | PCR | H/institution | 6 (6.1) | 98 |

| Babiker et al., 2009, Sudan [87] | FECT | H/institution | 2 (0.1) | 1500 |

| Mohamed et al., 2018, Sudan [88] | DSM | H/institution | 1 (0.2) | 600 |

| Knopp et al., 2014, Tanzania [89] | BCT, PCR | Community | 83 (7.4) | 1128 |

| Salim et al., 2014, Tanzania [90] | BCT | Community | 71 (6.9) | 1033 |

| Sikalengo et al., 2018, Tanzania [91] | BCT | H/institution | 89 (13.3) | 668 |

| Mhimbira et al., 2017, Tanzania [92] | BCT, FECT | Community | 161 (16.6) | 972 |

| Barda et al., 2017, Tanzania [93] | BCT, culture | School | 36 (7.1) | 509 |

| Oboth et al., 2019, Uganda [94] | KK | Refuge | 1 (0.2) | 476 |

| Stothard et al., 2008, Uganda [95] | BCT | Community | 4 (1.3) | 301 |

| Hillier et al., 2008, Uganda [96] | BCT | Community | 256 (12.4) | 2059 |

| Kelly et al., 2009, Zambia [97] | DSM | Community | 14 (0.5) | 2981 |

| Knopp et al., 2008, Zanzibar [98] | BCT, culture | Community | 7 (2.2) | 319 |

| Total | 2614 (2.7) | 96,069 |

∗BCT = Baermann concentration technique; DSM = direct saline microscopy; FECT = formol ether concentration technique; H/institution = health institution; KK = Kato-Katz; PCR = polymerase chain reaction.

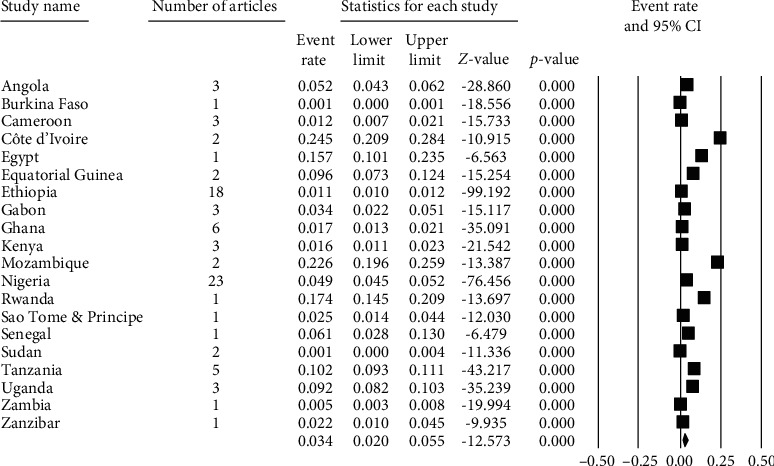

Among the 82 studies in Africa, the prevalence of strongyloidiasis ranged from 0.1% in a study conducted in Sudan [87] to 27.1% in Côte d'Ivoire [26] (Table 1). All studies in Côte d'Ivoire used a combination of two or three diagnostic techniques including PCR, BCT, and culture techniques. One of the two studies from Mozambique also used combination of FECT, BCT, and PCR reporting a prevalence rate of 48.51% [59]. The prevalence rate 17.4% in Rwanda was reported using agar plate culture among community dwellers [84]. The fourth highest prevalence 10.21% (92-96%) of strongyloidiasis was from Tanzania. All the five studies [89–93] conducted in Tanzania used BCT as diagnostic method, and three of which studies used PCR [90], FECT [93], or culture [94] (Table 1).

In Ethiopia, a relatively high number of participants 44,638 (45.1%) were included (Table 1) and the total pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis was 1.1% (1.0-1.2) (Figure 2). Most of the studies (13/18; 72.2%) used FECT, whereas four studies (22.2%) used DSM as a means of diagnosis. The majority of the studies (12/18: 66.7%) were conducted among patients visiting the health institutions for different ailments (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of strongyloidiasis in African countries using random effects model.

In Nigeria, a total of 14,294 (14.8%) study participants were involved in 23 (27.7%) studies (Table 1). The pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis in Nigeria was 4.9% (4.5-5.2%) (Figure 2). Nineteen (82.6%) and three (13.0%) of the studies used FECT and DSM diagnosis in Nigeria, respectively. Only one study used culture diagnostic method. In addition, 15 (65.2%) and eight (34.8%) studies were conducted among school-age children and patients, respectively (Table 1).

Low pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis was reported from studies conducted in Sudan (0.14%) [87], Zambia (0.5%) [97], and Burkina Faso (0.5%) [22]. Among studies conducted in Sudan, one study conducted using DSM [88] and the other by FECT [87] had low sensitivity to strongyloidiasis detection. The studies conducted in Burkina Faso and Zambia used DSM as a diagnostic method (Table 1).

The forest plots (Figure 2) indicated the pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis among 82 studies in Africa which was 3.4% (95% CI: 2.0-5.5%) using random effects model. The highest pooled prevalence 22.6% of strongyloidiasis was recorded in Côte d'Ivoire followed by Mozambique 22.6% (19.6-25.9%), Rwanda 17.4% (14.5-20.9%), and Egypt 15.7% (10.1-23.4%) (Figure 2). The heterogeneity of studies across African countries was high (Q = 2782.625, I2 = 99.317%, P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 2).

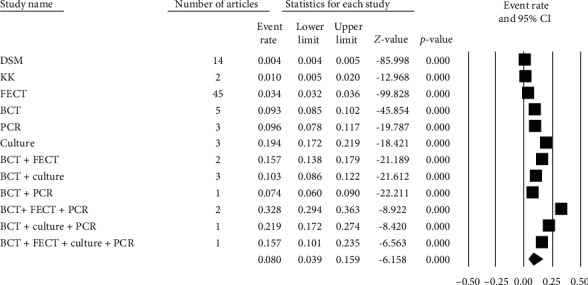

3.2. Diagnostic Methods of Strongyloidiasis

Regarding the diagnostic methods of S. stercoralis, most studies (69, 84.15%) used DM, KK, or FECT. Most of the studies (43, 52.4%) used FECT for diagnosing the infection in Africa (Figure 3). Among studies using single diagnostic methods, high pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis was recorded 19.4% in stool culture followed by 9.6% in PCR and 9.3% in BCT detection methods (Figure 3). The highest pooled prevalence rate 32.8% of strongyloidiasis was obtained by using a combination of BCT, FECT, and PCR diagnostic methods (Figure 3). The low prevalence rates of strongyloidiasis 3.4%, 0.4%, and 1.0% were also obtained using FECT, KK, and DSM diagnostic methods, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of strongyloidiasis prevalence by diagnostic methods using random effects model.

Forest plot (Figure 3) indicated that the pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis in Africa across different diagnostic methods was 8.0% (95% CI: 3.9-15.9%) using random effects model. Heterogeneity of studies through different diagnostic approaches was high (Q = 3497.655, I2 = 99.696%, P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 3).

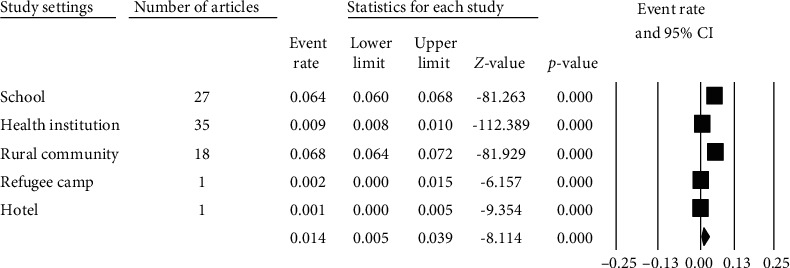

3.3. Strongyloidiasis by Study Settings

Among the total studies, 35 (42.68%) studies were conducted in health institutions followed by 27 (32.93%) in schools and 18 (21.95%) in rural communities (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of strongyloidiasis prevalence by study settings using random effects model.

The forest plot (Figure 4) shows the pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis across different study settings in Africa using random effects model which was 1.4% (95% CI: 0.5-3.9%). Heterogeneity of studies among the study sites in the African countries was high (Q = 1856.455, I2 = 9.785%, P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 4).

3.4. Strongyloidiasis In Health Institutions

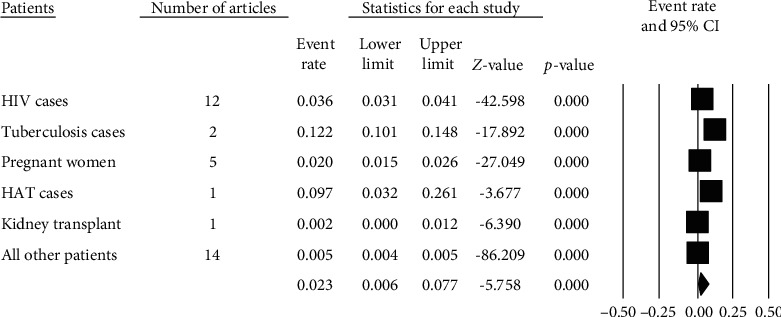

Pooled prevalence rates of 12.2%, 9.7%, and 3.6% of strongyloidiasis were obtained with the respective tuberculosis (TB), human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of strongyloidiasis prevalence among patients using random effects model.

Forest plot (Figure 5) indicates 2.3% (95% CI: 0.6-7.7%) pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis among patients across health institutions in Africa using random effects model. Heterogeneity of studies between patients in the African countries was high (Q = 83.334, I2 = 99.440%, P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 5).

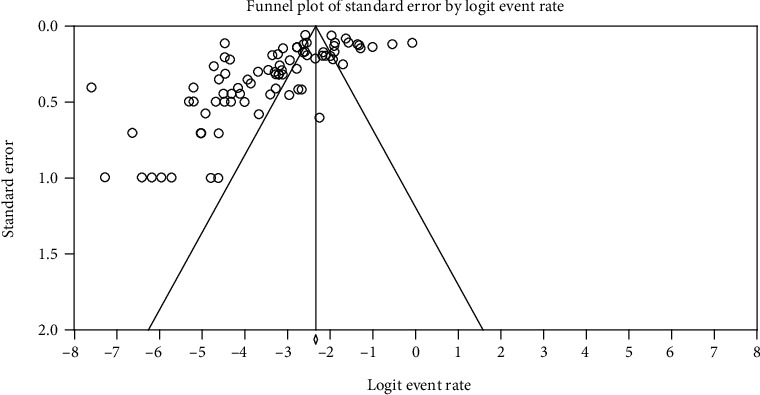

The funnel plot shows that studies were distributed symmetrically about the combined effect size that showed the absence of publication bias in this review (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Funnel plot displaying strongyloidiasis prevalence data for all included publications.

4. Discussion

The prevalence of strongyloidiasis in Africa is difficult to estimate due to inadequacy of studies and absence of very high-sensitive diagnostic methods. In this review, authors clearly demonstrated that a study conducted with DSM, FECT, and KK methods provided low strongyloidiasis prevalence report in the African continent. This finding is supported by the most widely used diagnostic methods to helminthic infections including DSM, FECT, and KK which most likely fail to detect strongyloidiasis [18]. The justification for the low prevalence rates of strongyloidiasis in African in the current review might be due to the use of traditional methods (FECT, KK, and DSM), very small amount of stool sample used, and one-time stool sample collection which may give false-negative results. Moreover, single stool examination might also compromise the true prevalence of strongyloidiasis detection. For instance, single stool examination using DSM can detect the strongyloidiasis larvae in only 30% of the cases [99]. Furthermore, the intermittent excretion nature of S. stercoralis and chronic low-intensity infections which lead to low larval load within the stool may also affect the true prevalence [7]. Generally, most African countries use low-sensitivity diagnostic methods for strongyloidiasis detection since there is a lack of awareness and more sensitive diagnostic methods are costly and difficult to adopt in most African health institutions. As a result, they stick to using FECT and DSM with their limitations [18].

In this review, stool culture, BCT, and PCR are more sensitive methods for the diagnosis of strongyloidiasis. This finding is supported by other previous studies [15, 100]. A combination of two or three of the culture, BCT, and PCR provided better detection rate of strongyloidiasis in stool in the current review. This result agrees with a previous report [6], and better detection of strongyloidiasis was obtained using combination of BCT and other methods [101]. Nevertheless, it should be borne in mind that the sensitivity of such tests is not perfect, especially when it is performed on a single fecal specimen, diarrheic stool, and a very small amount of stool sample. All these might lead to underdiagnosis and underestimation of the true prevalence of strongyloidiasis. Therefore, there is a need to define a standard protocol in terms of diagnostic methods, the amount and consistency of stool specimens, and the frequency of examination of stool specimens for better assessment of strongyloidiasis. Such priority recommendations and elaboration of mapping guidelines should be done by the World Health Organization for strongyloidiasis like the other soil-transmitted helminthic infections and included in the neglected tropical disease (NTD) group.

The prevalence of strongyloidiasis among community dwellers of Africa in the current review was relatively high (6.69%). This is consistent with an earlier report [7]. This high prevalence of strongyloidiasis in a rural community might be due to low sanitation and hygiene practice, limited knowledge on the transmission of Strongyloides infection, and absence of adequate water for sanitation and hygiene in the rural communities of African countries [102, 103].

The prevalence of strongyloidiasis among school children was 6.4% (6.0-6.8%) in this review. A considerable similar report among school-age children is also found in a systematic review conducted in Ethiopia [104]. This might be justified firstly by the fact that African children are living in unhygienic environment with poor sanitation practices where most children play with contaminated soil and walk barefoot that increases the probability of the entrance of the filariform larvae in the body [105]. Secondly, most African children are malnourished [106] and this is evidenced by a high prevalence of strongyloidiasis among malnourished children [107]. Thirdly, a high infection rate of strongyloidiasis was seen in immunocompromised children [108].

In this review, the distribution of strongyloidiasis among patients was 2.3% (0.6-7.7%). This result is consistent with 5.1% prevalence among HIV patients in the previous report [7] but lower than 23% among Bolivian patients [108]. The difference might be due to diagnostic method difference and serological test used in addition to coproparasitological test in a study conducted in Bolivia.

In the current review, heterogeneity of studies was high and there was no publication bias. The current heterogeneity finding is consistent, but the publication bias report disagrees with a previous report [109]. The absence of publication bias might be justified as combined effect size in the current studies is distributed symmetrically using funnel plot.

Unlike other soil-transmitted helminth infections, much attention is not given to Strongyloidiasis by the policymakers although the global burden is probably much higher than previously estimated. We encourage researchers to work on standardizing diagnostic protocols of strongyloidiasis and also policymakers to include strongyloidiasis in the soil-transmitted helminth package.

4.1. Limitation of This Review

The use of only PubMed and Google Scholar databases as a source of articles was the limitation of this review.

5. Conclusions

This review shows that strongyloidiasis prevalence is overlooked and its prevalence is low in Africa due to the use of low-sensitivity diagnostic methods and lack of correct diagnostic approach. A combination of microscopic and PCR method gives good detection rate of strongyloidiasis. Therefore, there is a need for using a combination of microscopic and molecular-based diagnostic methods to determine the true prevalence in Africa. Further research is also needed to break the transmission cycle and reduce the impacts of strongyloidiasis in the African population.

Data Availability

The data can be requested from Bahir Dar University (https://bdu.edu.et/node/74).

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declare(s) that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

All the authors acknowledged their active participation during gathering and screening of articles and critically reviewing this systematic review and meta-analysis.

References

- 1.Grove D. I. Human strongyloidiasis. Advances in Parasitology. 1996;38:251–309. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(08)60036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashford R. W., Barnish G., Viney M. E. Strongyloides fuelleborni kellyi: infection and disease in Papua New Guinea. Parasitology Today. 1992;8(9):314–318. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(92)90106-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Requena-Méndez A., Chiodini P., Bisoffi Z., Buonfrate D., Gotuzzo E., Muñoz J. The Laboratory Diagnosis and Follow Up of Strongyloidiasis: A Systematic Review. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2013;7(1):p. e2002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisoffi Z., Buonfrate D., Montresor A., et al. Strongyloides stercoralis: a plea for action. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2013;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO The world Health Organaization. Soil-transmitted helminth infections. Fact sheet. 2016. September 2019 http://www.who.int/intestinal_worms/en/

- 6.Amor A., Rodriguez E., Saugar J. M., et al. High prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis in school-aged children in a rural highland of North-Western Ethiopia: the role of intensive diagnostic work-up. Parasites & Vectors. 2016;9(1):p. 617. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1912-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schär F., Trostdorf U., Giardina F., et al. Strongyloides stercoralis: global distribution and risk factors. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2013;7(7):p. e2288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsen A., van Lieshout L., Marti H., et al. Strongyloidiasis-the most neglected of the neglected tropical diseases? Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2009;103(10):967–972. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viney M., Lok J. B. The C. elegans Research Community. Strongyloides spp. WormBook; 2007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grove D. I. Strongyloidiasis: a conundrum for gastroenterologists. Gut. 1994;35(4):437–440. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.4.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nsagha D. S., Njunda A. L., Assob N. J. C., et al. Intestinal parasitic infections in relation to CD4+ T cell counts and diarrhea in HIV/AIDS patients with or without antiretroviral therapy in Cameroon. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2015;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1337-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotman H. L., Yutanawiboonchai W., Brigandi R. A., et al. Strongyloides stercoralis: eosinophil-dependent immune-mediated killing of third stage larvae in BALB/cByJ mice. Experimental Parasitology. 1996;82(3):267–278. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandong B. M., Madaki A. J. K. Missed diagnosis of schistosomiasis leading to unnecessary surgical procedures in Jos University Teaching Hospital. Tropical Doctor. 2005;35(2):96–97. doi: 10.1258/0049475054037011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Kaminsky R. G. Evaluation of three methods for laboratory diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. The Journal of Parasitology. 1993;79(2):277–280. doi: 10.2307/3283519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arakaki T., Iwanaga M., Kinjo F., Saito A., Asato R., Ikeshiro T. Efficacy of Agar-Plate Culture in Detection of Strongyloides stercoralis Infection. The Journal of Parasitology. 1990;76(3):425–428. doi: 10.2307/3282680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pak B. J., Vasquez-Camargo F., Kalinichenko E., et al. Development of a rapid serological assay for the diagnosis of strongyloidiasis using a novel diffraction-based biosensor technology. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2014;8(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Paula F. M., de Mello Malta F., Marques P. D., et al. Molecular diagnosis of strongyloidiasis in tropical areas: a comparison of conventional and real-time polymerase chain reaction with parasitological methods. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110(2):272–274. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760140371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Assefa T., Woldemichael T., Seyoum T. Evaluation of the modified Baermann’s method in the laboratory diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis. Ethiopian Medical Journal. 1991;29(4):193–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dacal E., Saugar J. M., de Lucio A., et al. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Strongyloides stercoralis, Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium spp., and Blastocystis spp. isolates in school children in Cubal, Western Angola. Parasites & Vectors. 2018;11(1):p. 67. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-2640-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bocanegra C., Gallego S., Mendioroz J., et al. Epidemiology of Schistosomiasis and Usefulness of Indirect Diagnostic Tests in School-Age Children in Cubal, Central Angola. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2015;9(10):p. e0004055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Alegría M. L. A. R., Nindia A., Moreno M., et al. Prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis and Other Intestinal Parasite Infections in School Children in a Rural Area of Angola: A Cross-Sectional Study. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2017;97(4):1226–1231. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karou S. D., Sanou D., Ouermi D., et al. Enteric parasites prevalence at Saint Camille Medical Centre in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2011;4(5):401–403. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bopda J., Nana-Djeunga H., Tenaguem J., et al. Prevalence and intensity of human soil transmitted helminth infections in the Akonolinga health district (Centre region, Cameroon): are adult hosts contributing in the persistence of the transmission? Parasite Epidemiology and Control. 2016;1(2):199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.parepi.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuete T., Yemeli F. L. S., Mvoa E. E., Nkoa T., Somo R. M., Ekobo A. S. Prevalence and risk factors of intestinal helminth and Protozoa infections in an urban setting of Cameroon: the case of Douala. Am J Epidemiol Infect Dis. 2015;3(2):36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker S. L., Piraisoody N., Kramme S., et al. Real-time PCR for detection of Strongyloides stercoralis in human stool samples from Côte d’Ivoire: diagnostic accuracy, inter-laboratory comparison and patterns of hookworm co-infection. Acta Tropica. 2015;150:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glinz D., N'Guessan N. A., Utzinger J., N'Goran E. K. High prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis among school children in rural Côte d'Ivoire. The Journal of Parasitology. 2010;96(2):431–433. doi: 10.1645/GE-2294.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rayan H. Z., Soliman R. H., Galal N. M. Detection of Strongyloides stercoralis in fecal samples using conventional parasitological techniques and real-time PCR: a comparative study. Parasitol United J. 2012;5:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roka M., Goni P., Rubio E., Clavel A. Intestinal parasites in HIV-seropositive patients in the continental region of Equatorial Guinea: its relation with socio-demographic, health and immune systems factors. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2013;107(8):502–510. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trt049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roka M., Goni P., Rubio E., Clavel A. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in HIV-positive patients on the island of Bioko, Equatorial Guinea: its relation to sanitary conditions and socioeconomic factors. Sci Total Environ. 2012;432:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdi M., Nibret E., Munshea A. Prevalence of intestinal helminthic infections and malnutrition among schoolchildren of the Zegie Peninsula, northwestern Ethiopia. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2017;10(1):84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramos J. M., Rodríguez-Valero N., Tisiano G., et al. Different profile of intestinal protozoa and helminthic infections among patients with diarrhoea according to age attending a rural hospital in southern Ethiopia. Tropical Biomedicine. 2014;31(2):392–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeynudin A., Hemalatha K., Kannan S. Prevalence of opportunistic intestinal parasitic infection among HIV infected patients who are taking antiretroviral treatment at Jimma Health Center, Jimma, Ethiopia. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2013;17(4):513–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Assefa S., Erko B., Medhin G., Assefa Z., Shimelis T. Intestinal parasitic infections in relation to HIV/AIDS status, diarrhea and CD4 T-cell count. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2009;9(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wegayehu T., Tsalla T., Seifu B., Teklu T. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among highland and lowland dwellers in Gamo area, South Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huruy K., Kassu A., Mulu A., et al. Intestinal parasitosis and shigellosis among diarrheal patients in Gondar Teaching Hospital, northwest Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes. 2011;4(1) doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gedle D., Gelaw B., Muluye D., Mesele M. Prevalence of malnutrition and its associated factors among adult people living with HIV/AIDS receiving anti-retroviral therapy at Butajira Hospital, southern Ethiopia. BMC Nutrition. 2015;1(1):p. 5. doi: 10.1186/2055-0928-1-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abera B., Alem G., Yimer M., Herrador Z. Epidemiology of soil-transmitted helminths, Schistosoma mansoni, and haematocrit values among schoolchildren in Ethiopia. Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 2013;7(3):253–260. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Derso A., Nibret E., Munshea A. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care center at Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2016;16(1):p. 530. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1859-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fekadu S., Taye K., Teshome W., Asnake S. Prevalence of parasitic infections in HIV-positive patients in southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 2013;7(11):868–872. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abate A., Kibret B., Bekalu E., et al. Cross-Sectional Study on the Prevalence of Intestinal Parasites and Associated Risk Factors in Teda Health Centre, Northwest Ethiopia. ISRN Parasitology. 2013;2013:5. doi: 10.5402/2013/757451.757451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alemu G., Alelign D., Abossie A. Prevalence of opportunistic intestinal parasites and associated factors among HIV patients while receiving ART at Arba Minch Hospital in southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences. 2018;28(2):147–156. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v28i2.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teklemariam Z., Abate D., Mitiku H., Dessie Y. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infection among HIV positive persons who are naive and on antiretroviral treatment in Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, eastern Ethiopia. ISRN AIDS. 2013;2013:6. doi: 10.1155/2013/324329.324329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Legesse L., Erko B., Hailu A. Current status of intestinal Schistosomiasis and soiltransmitted helminthiasis among primary school children in Adwa Town, Northern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development. 2011;24(3) doi: 10.4314/ejhd.v24i3.68384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hailu A. W., Selassie S., Merid Y., Gebru A. A., Ayene Y. Y., Asefa M. K. The case control studies of HIV and intestinal parasitic infections rate in active pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Woldia General Hospital and Health Center in North Wollo, Amhara region, Ethiopia. International Journal Pharma Sciences. 2015;5(3):1092–1099. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nyantekyi L. A., Legesse M., Belay M., et al. Intestinal parasitic infections among under-five children and maternal awareness about the infections in Shesha Kekele, Wondo Genet, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development. 2011;24(3):185–190. doi: 10.4314/ejhd.v24i3.68383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chala B. A retrospective analysis of the results of a five-year (2005–2009) parasitological examination for common intestinal parasites from Bale-Robe Health Center, Robe town, southeastern Ethiopia. ISRN Parasitology. 2013;2013:7. doi: 10.5402/2013/694731.694731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.M’bondoukwé N. P., Kendjo E., Mawili-Mboumba D. P., et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for malaria, filariasis, and intestinal parasites as single infections or co-infections in different settlements of Gabon, Central Africa. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2018;7(1):p. 6. doi: 10.1186/s40249-017-0381-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Janssen S., Hermans S., Knap M., et al. Impact of anti-retroviral treatment and cotrimoxazole prophylaxis on helminth infections in HIV-infected patients in Lambaréné, Gabon. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2015;9(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mbondoukwe P., Mboumba P., Mondouo F., Kombila M., Akotet M. Prevalence of soil-transmitted helminths and intestinal Protozoa in shanty towns of Libreville, Gabon. International Journal of TROPICAL DISEASE & Health. 2016;20(3):1–9. doi: 10.9734/ijtdh/2016/26774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adu-Gyasi D., Asante K. P., Frempong M. T., et al. Epidemiology of soil transmitted helminth infections in the middle-belt of Ghana, Africa. Parasite Epidemiology and Control. 2018;3(3):p. e00071. doi: 10.1016/j.parepi.2018.e00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nkrumah B., Nguah S. B. Giardia lamblia: a major parasitic cause of childhood diarrhoea in patients attending a district hospital in Ghana. Parasites & Vectors. 2011;4(1) doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Forson A. O., Arthur I., Olu-Taiwo M., Glover K. K., Pappoe-Ashong P. J., Ayeh-Kumi P. F. Intestinal parasitic infections and risk factors: a cross-sectional survey of some school children in a suburb in Accra, Ghana. BMC Research Notes. 2017;10(1):p. 485. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2802-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yatich N. J., Rayner J. C., Turpin A., et al. Malaria and intestinal helminth co-infection among pregnant women in Ghana: prevalence and risk factors. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2009;80(6):896–901. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.80.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sam Y., Edzeamey F. J., Frimpong E. H., Ako A. K., Appiah-Kubi K. Prevalence of soil-transmitted helminths among school pupils in the upper east region of Ghana using direct wet mount technique and formol-ether concentration technique. IJTDH. 2018;32(3):1–9. doi: 10.9734/IJTDH/2018/43809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cunningham L. J., Odoom J., Pratt D., et al. Expanding molecular diagnostics of helminthiasis: piloting use of the GPLN platform for surveillance of soil transmitted helminthiasis and schistosomiasis in Ghana. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2018;12(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kagira J. M., Maina N., Njenga J., Karanja S. M., Karori S. M., Ngotho J. M. Prevalence and types of coinfections in sleeping sickness patients in Kenya (2000/2009) Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2011;2011:6. doi: 10.1155/2011/248914.248914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walson J. L., Stewart B. T., Sangaré L., et al. Prevalence and correlates of helminth co-infection in Kenyan HIV-1 infected adults. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2010;4(3):p. e644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arndt M. B., John-Stewart G., Richardson B. A., et al. Impact of helminth diagnostic test performance on estimation of risk factors and outcomes in HIV-positive adults. PLoS One. 2013;8(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meurs L., Polderman A. M., Vinkeles Melchers N. V. S., et al. Diagnosing polyparasitism in a high-prevalence setting in Beira, Mozambique: detection of intestinal parasites in fecal samples by microscopy and real-time PCR. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2017;11(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cerveja B. Z., Tucuzo R. M., Madureira A. C., et al. Prevalence of Intestinal Parasites Among HIV Infected and HIV Uninfected Patients Treated at the 1° De Maio Health Centre in Maputo, Mozambique. EC Microbiology. 2017;9(6):231–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chukwuma M. C., Ekejindu I. M., Agbakoba N. R., Ezeagwuna D. A., Anaghalu I. C., Nwosu D. C. The prevalence and risk factors of geohelminth infections among primary school children in Ebenebe town, Anambra state, Nigeria. Middle-East J Sci Res. 2009;4(3):211–215. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uhuo A. C., Odikamnoro O. O., Ani O. C. The incidence of intestinal nematodes in primary school children in Ezza North local government area, Ebonyi state Nigeria. Advances in Applied Science Research. 2011;2(5):257–262. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wosu M., Onyeabor A. The Prevalence of Intestinal Parasite Infections among School Children in a Tropical Rainforest Community in Southeastern Nigeria. Journal of Animal Science Advances. 2014;4(8):1004–1008. doi: 10.5455/jasa.20140827111807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simon-oke I. A., Afolabi O. J., Afolabi T. G. The prevalence of soil transmitted helminthes among school children in Ifedore local government area of Ondo state, Nigeria. EJBMSR. 2014;2(1):17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adekolujo D. R., Olayinka S. O., Adeniji J. A., Oyeyemi O. T., Odaibo A. B. Poliovirus and other enteroviruses in children infected with intestinal parasites in Nigeria. Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 2015;9(10):1166–1171. doi: 10.3855/jidc.5863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adefioye O. A., Efunshile A. M., Ojurongbe O., et al. Intestinal Helminthiasis among School Children in Ilie, Osun State, Southwest, Nigeria. Sierra Leone Journal of Biomedical Research. 2011;3(1) doi: 10.4314/sljbr.v3i1.66651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goon D. T., Abaver D. T., Nwobegahay J. M., Iweriebor B. C., Anye D. N. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among HIV/AIDS patients from two health institutions in Abuja, Nigeria. African Health Sciences. 2011;11(3) doi: 10.4314/ahs.v11i3.70066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ivoke N., Ikpor N., Ivoke O., et al. Geophagy as risk behaviour for gastrointestinal nematode infections among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in a humid tropical zone of Nigeria. African Health Sciences. 2017;17(1):24–31. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v17i1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ojurongbe O., Okorie P. N., Opatokun R. L., et al. Prevalence and associated factors of Plasmodium falciparum and soil transmitted helminth infections among pregnant women in Osun state, Nigeria. African Health Sciences. 2018;18(3):542–551. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v18i3.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Emeka L. I. Prevalence of Intestinal Helminthic Infection among School Children in Rural and Semi Urban Communities in Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences. 2013;6(5):61–66. doi: 10.9790/0853-0656166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Esiet U. L. P., Asariedet I. Comparative prevalence of intestinal parasites among children in public and private schools in Calabar South, Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria. A J Res Commun. 2017;5(1):80–97. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Abdulhadi B. J. Survey on Prevalence of Intestinal Parasites Associated With Some Primary School Aged Children in Dutsinma Area, Katsina State, Nigeria. MOJ Biology and Medicine. 2017;2(2):197–201. doi: 10.15406/mojbm.2017.02.00044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Onyido A. E., Okoye M. M., Irikannu K. C., Okafor E. N., Ugha C. N., Umeanaeto P. U. Intestinal helminth infections among primary school pupils in Nimo community, Njikoka local government area, Anambra state, southeastern Nigeria. JARBPR. 2016;1(4):p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abah A. E., Arene F. O. I. Status of Intestinal Parasitic Infections among Primary School Children in Rivers State, Nigeria. Journal of Parasitology Research. 2015;2015:7. doi: 10.1155/2015/937096.937096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Damen J. G., Lar P., Mershak P., Mbaawuga E. M., Nyary B. W. A Comparative Study on the Prevalence of Intestinal Helminthes in Dewormed and Non-Dewormed Students in a Rural Area of North-Central Nigeria. Laboratory Medicine. 2010;41(10):585–589. doi: 10.1309/lm0fjmg1jod5kltg. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Akinbo F. O., Okaka C. E., Omoregie R. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among HIV patients in Benin City, Nigeria. Libyan Journal of Medicine. 2010;5(1):p. 5506. doi: 10.3402/ljm.v5i0.5506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ojurongbe O., Oyesiji K. F., Ojo J. A., Odewale G., Adefioye O. A., Olowe A. O., et al. Soil transmitted helminth infections among primary school children in Ile-Ife southwest, Nigeria: a crosssectional study. Int Res J Med Med Sci. 2014;2(1):6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Amoo J. K., Akindele A. A., Amoo A. O. J., et al. Prevalence of enteric parasitic infections among people living with HIV in Abeokuta, Nigeria. Pan African Medical Journal. 2018;30 doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.30.66.13160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alli J. A., Okonko I. O., Kolade A. F., Nwanze J. C., Dada V. K., Ogundele M. Prevalence of intestinal nematode infection among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at the University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. Adv Appl Sci Res. 2011;2(4):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eke S. S., Ibeh E. O., Omalu I. C. J., Otuu C. A., Hassan S. C., Ubanwa E. D. Prevalence of geohelminth in soil and primary school children in Panda Development Area, Karu local government area, Nasarawa state, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Parasitology. 2016;36(2) doi: 10.4314/njpar.v37i2.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Auta T., Kogi E., Audu O. K. Studies on the intestinal helminths infestation among primary school children in Gwagwada, Kaduna, northwestern Nigeria. JBAH. 2013;3:p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Aniwada E., Uleanya N., Igbokwe L., Onwasigwe C. Soil Transmitted Helminths; Prevalence, Perception and Determinants among Primary School Children in Rural Enugu State, Nigeria. International Journal of TROPICAL DISEASE & Health. 2016;15(1):1–12. doi: 10.9734/ijtdh/2016/24501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Umar A. A., Bassey S. E. Incidence of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in Ungogo, Nassarawa, Dala and Fagge local government areas of Kano State, Nigeria. Bayero Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences. 2011;3(2) doi: 10.4314/bajopas.v3i2.63224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tuyizere A., Ndayambaje A., Walker T. D., et al. Prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis infection and other soil-transmitted helminths by cross-sectional survey in a rural community in Gisagara District, Southern Province, Rwanda. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2018;112(3):97–102. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/try036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ferreira F. S., Baptista-Fernandes T., Oliveira D., et al. Giardia duodenalis and soil-transmitted helminths infections in children in Sao Tome and Principe: do we think Giardia when addressing parasite control? Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 2015;61(2):106–112. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmu078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sow D., Halfon P., Sylla K., et al. Performance of real-time polymerase chain reaction assays for the detection of 20 gastrointestinal parasites in clinical samples from Senegal. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2017;97(1):173–182. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Babiker M. A., Ali M. S. M., Ahmed E. S. Frequency of intestinal parasites among food-handlers in Khartoum, Sudan. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2009;15(5):1098–1104. doi: 10.26719/2009.15.5.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mohamed N. S., Siddig E. E., Mohamed M. A., et al. Enteroparasitosis infections among renal transplant recipients in Khartoum state, Sudan 2012–2013. BMC Research Notes. 2018;11(1):p. 621. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3716-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Knopp S., Salim N., Schindler T., et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Kato–Katz, FLOTAC, Baermann, and PCR Methods for the Detection of Light-Intensity Hookworm and Strongyloides stercoralis Infections in Tanzania. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2014;90(3):535–545. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Salim N., Schindler T., Abdul U., et al. Enterobiasis and strongyloidiasis and associated co-infections and morbidity markers in infants, preschool- and school-aged children from rural coastal Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2014;14(1):p. 644. doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0644-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sikalengo G., Hella J., Mhimbira F., et al. Distinct clinical characteristics and helminth co-infections in adult tuberculosis patients from urban compared to rural Tanzania. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2018;7(1):p. 24. doi: 10.1186/s40249-018-0404-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mhimbira F., Hella J., Said K., et al. Prevalence and clinical relevance of helminth co-infections among tuberculosis patients in urban Tanzania. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2017;11(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Barda B., Speich B., Keiser J., et al. Side Benefits of Mass Drug Administration for Lymphatic Filariasis on Strongyloides stercoralis Prevalence on Pemba Island, Tanzania. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2017;97(3):681–683. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Oboth P., Gavamukulya Y., Barugahare B. J. Prevalence and clinical outcomes of Plasmodium falciparum and intestinal parasitic infections among children in Kiryandongo refugee camp, mid-Western Uganda: a cross sectional study. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2019;19(1):p. 295. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3939-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stothard J. R., Pleasant J., Oguttu D., et al. Strongyloides stercoralis: a field-based survey of mothers and their preschool children using ELISA, Baermann and Koga plate methods reveals low endemicity in western Uganda. Journal of Helminthology. 2008;82(3):263–269. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X08971996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hillier S. D., Booth M., Muhangi L., et al. Plasmodium falciparumand helminth coinfection in a semiurban population of pregnant women in Uganda. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;198(6):920–927. doi: 10.1086/591183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kelly P., Todd J., Sianongo S., et al. Susceptibility to intestinal infection and diarrhoea in Zambian adults in relation to HIV status and CD4 count. BMC Gastroenterology. 2009;9(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Knopp S., Mohammed K. A., Khamis I. S., et al. Spatial distribution of soil-transmitted helminths, including Strongyloides stercoralis, among children in Zanzibar. Geospatial Health. 2008;3(1):47–56. doi: 10.4081/gh.2008.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.WGO World Gastroentrology Organization, 2004. Practice guideline management of strongyloidiasis. https://www.worldgastroenterology.org/UserFiles/file/guidelines /management-of-strongyloidiasis-english-2004.pdf.

- 100.Schär F., Odermatt P., Khieu V., et al. Evaluation of real-time PCR for Strongyloides stercoralis and hookworm as diagnostic tool in asymptomatic schoolchildren in Cambodia. Acta Tropica. 2013;126(2):89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pocaterra L. A., Ferrara G., Peñaranda R., et al. Improved Detection of Strongyloides stercoralis in Modified Agar Plate Cultures. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2017;96(4):863–865. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Khieu V., Schär F., Forrer A., et al. High prevalence and spatial distribution of Strongyloides stercoralis in rural Cambodia. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2014;8(6):p. e2854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Forrer A., Khieu V., Vounatsou P., et al. Strongyloides stercoralis: Spatial distribution of a highly prevalent and ubiquitous soil-transmitted helminth in Cambodia. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2019;13(6):p. e0006943. doi: 10.1101/453274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Terefe Y., Ross K., Whiley H. Strongyloidiasis in Ethiopia: systematic review on risk factors, diagnosis, prevalence and clinical outcomes. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2019;8(1):p. 53. doi: 10.1186/s40249-019-0555-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.YORI P. A. B. L. O. P., BERN C. A. R. Y. N., CHAVEZ C. E. S. A. R. B. A. N. D. A., et al. SEROEPIDEMIOLOGY OF STRONGYLOIDIASIS IN THE PERUVIAN AMAZON. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2006;74(1):97–102. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2006.74.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2019. Safeguarding against economic slowdowns and downturns. Rome: FAO; 2019. https://www.unicef.org/media/55921/file/SOFI-2019. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Forrer A., Khieu V., Schär F., et al. Strongyloides stercoralis is associated with significant morbidity in rural Cambodia, including stunting in children. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2017;11(10):p. e0005685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gétaz L., Castro R., Zamora P., et al. Epidemiology of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in Bolivian patients at high risk of complications. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2019;13(1):p. e0007028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ahmadpour E., Ghanizadegan M. A., Razavi A., et al. Strongyloides stercoralisinfection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients and related risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 2019;66(6):2233–2243. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be requested from Bahir Dar University (https://bdu.edu.et/node/74).