Abstract

Longitudinal preclinical and clinical studies suggest that Aβ drives neurite and synapse degeneration through an array of tau-dependent and independent mechanisms. The intracellular signaling networks regulated by the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) substantially overlap with those linked to Aβ and to tau. Here we examine the hypothesis that modulation of p75NTR will suppress the generation of multiple potentially pathogenic tau species and related signaling to protect dendritic spines and processes from Aβ-induced injury. In neurons exposed to oligomeric Aβ in vitro and APP mutant mouse models, modulation of p75NTR signaling using the small-molecule LM11A-31 was found to inhibit Aβ-associated degeneration of neurites and spines; and tau phosphorylation, cleavage, oligomerization and missorting. In line with these effects on tau, LM11A-31 inhibited excess activation of Fyn kinase and its targets, tau and NMDA-NR2B, and decreased Rho kinase signaling changes and downstream aberrant cofilin phosphorylation. In vitro studies with pseudohyperphosphorylated tau and constitutively active RhoA revealed that LM11A-31 likely acts principally upstream of tau phosphorylation, and has effects preventing spine loss both up and downstream of RhoA activation. These findings support the hypothesis that modulation of p75NTR signaling inhibits a broad spectrum of Aβ-triggered, tau-related molecular pathology thereby contributing to synaptic resilience.

Subject terms: Alzheimer's disease, Mechanism of action, Neurotrophic factors

Introduction

Degeneration of neurites, and synapses and spines in particular, are among the pathophysiological features that best correlate with loss of cognition in Alzheimer’s disease (AD)1,2. Clinical3 and mouse model4 studies, suggest that Aβ drives synaptic degeneration and failure, in large part, through tau-mediated mechanisms5. Moreover, longitudinal AD studies have identified subjects with significant amyloid accumulation, but with largely absent neurite/synapse degeneration and/or cognitive impairment (termed AD resilience)2 and this has further stimulated interest in the identification of mechanistic targets and therapeutic approaches that might prevent degeneration promoted by the Aβ-tau axis. Significant challenges to these efforts include the wide array of pathological tau molecular mechanisms triggered by Aβ, and additionally, the possibility that there are concomitant, tau-independent mechanisms through which Aβ promotes synaptic failure.

Molecular mechanisms relevant to the neurite and synapse degeneration triggered by amyloid beta (Aβ) and occurring in AD include: increased phosphorylation, misfolding, cleavage and oligomerization of tau6,7; missorting of pathological forms of tau into dendrites and spines promoting deleterious protein–protein interactions8; and aberrant cofilin-mediated actin modification within spines9. Upstream signaling changes occurring in AD and likely contributing to these processes include increased tau kinase activity10, increased caspase mediated tau cleavage11–13, and dysregulated Rho kinase activity14–17.

Signaling networks regulated by p75NTR have a substantial overlap with AD-related degenerative networks18–20. Moreover, p75 is expressed by most neuronal populations involved in AD, including those affected in the earliest stages21,22. Given these findings, and that p75NTR in its unliganded state or in the presence of its principal central nervous system ligands, pro-neurotrophins, enables or promotes neuronal degeneration23, we and others have tested the hypothesis that knockout of intact p75NTR would inhibit Aβ-related degeneration. In in vitro studies, degeneration of mouse hippocampal neuron neurites triggered by Aβ oligomers was blocked in cultures of p75NTR–/– hippocampal neurons24,25. Consistent with these in vitro studies, injection of Aβ oligomers into the hippocampus of p75NTR–/– mice resulted in decreased degeneration of basal forebrain neurons relative to wildtype mice24 and crossing of p75NTR–/– mice with two different APP mutant AD mouse models resulted in decreased neurite degeneration without a decrease in Aβ levels25,26. In clinical studies, polymorphisms involving the genes encoding p75NTR ligands proNGF and proBDNF27,28 and its co-receptors sortilin and sorCS229,30 have been found to be associated with AD. In addition, associations between genetic polymorphisms involving p75NTR and AD have been identified31,32. These genetic findings implicate the p75NTR/ligand/co-receptor signaling module as a candidate contributor in the development of AD. At the protein level, proNGF is increased in brain tissue or cerebrospinal fluid derived from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD subjects with significant correlations between the proNGF level and cognitive score23,33,34.

In prior studies, we developed small molecule ligands of p75NTR that modulate its activity to downregulate degenerative and upregulate trophic signaling20,35. One of these, LM11A-31, has been found to block several p75NTR-linked pathophysiological mechanisms in the context of AD19. LM11A-31 blocks neuritic dystrophy induced by Aβ oligomers in vitro, and in APP mouse models inhibits excess tau phosphorylation and misfolding as well as decreasing neuritic dystrophy19,36–38.

To investigate the role of p75NTR in tau-related mechanisms and AD resilience, we determined the effects of the p75NTR modulator LM11A-31 on tau molecular pathologies and neurite, spine and synaptic degeneration triggered by Aβ. We found that the compound had unexpectedly broad effects on tau-related molecular mechanisms induced by Aβ, and substantially inhibited degeneration of neurites and spines. These findings support small molecule p75NTR-targeting strategies for conferring resilience in the context of Aβ accumulation.

Results

p75NTR modulation mitigates Aβ-induced neuritic and spine neurite degeneration

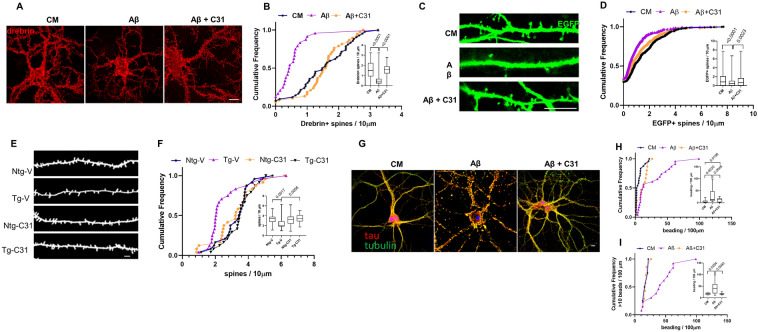

Hippocampal neurons at > 15 days in vitro (DIV) respond to addition of soluble Aβ oligomers with synaptic and neuritic degeneration rather than cell death, which occurs in less mature cultures39,40. Loss of structures containing drebrin, an F-actin binding protein present in dendritic spines, serves as a measure of Aβ-induced spine degeneration in vitro39 and studies have found that total drebrin levels are reduced in human AD and AD mouse model brain tissue, and drebrin-containing spines have been shown to be substantially reduced in the latter41. In the present study, exposure of 21 DIV hippocampal neurons to oligomeric Aβ caused an ~ 70% decrease in the median density and significant uniform left shift of the density distribution of drebrin-positive spines; this effect was blocked by LM11A-31 (Fig. 1A,B). These observations were further characterized by visualization and counting of spines, made visible by the transfection of cells with EGFP, which was previously utilized to assess Aβ effects on spines42. Here, spine densities in EGFP-expressing cells were decreased ~ 50% by Aβ with significant, though incomplete protection by LM11A-31 (Fig. 1C,D).

Figure 1.

p75NTR modulation mitigates Aβ-induced loss of spines and neurite injury. (A–D) 21 DIV hippocampal neurons were treated with CM, Aβ, or Aβ with 100 nM LM11A-31 and examined at 24 h following treatment. (A) Representative neurons stained for drebrin (red). (B) Quantitation of numbers of drebrin-positive spines per length of dendrite segment, displayed in cumulative frequency and (inset) box plots, with p values above the boxes from KS testing of indicated comparisons. n = 24–38 neurites per condition from a total of 3 independent experiments. (C) Dendritic spines of EGFP-transfected hippocampal neurons (green) were visualized at 24 h post-Aβ exposure. (D) Dendritic spine density quantitated and displayed as in (B). n = 36–43 neurons per condition from a total of 9 independent experiments. (E,F) 7.5–8.0-month-old non-transgenic mice (Ntg) and AβPPL/S mice (Tg) were treated with either vehicle (V) or LM11A-31 (C31) by oral gavage for 3 months, at which time spine density of hippocampal CA1 neurons was determined in Golgi-stained dendrites using MBF Neurolucida. (E) Representative traced dendritic spine images. (F) Quantitative analysis of the dendritic spine density displayed as in (B). 3 neurons from each of 6 mice were analyzed from each treatment group (n = 18/group). Scale bars in each image, 10 µm. To assess neuritic injury, neurons were immunostained for tau (red) and tubulin (green) and discrete yellow regions (‘beads’), reflecting co-accumulation of tau and tubulin, were manually counted and expressed as number of beads/100 µm neurite beads. Scale bar, 10 µm (G). (H) Cumulative frequency analysis shows a population of higher-count segments in Aβ-treated cells not observed in the presence of C31 or without Aβ. Inset displays box plots with p values from KS testing for the indicated comparisons. (I) Analysis of distributions of high-count segments (> 10 beads/100 µm). n = 12–14 neurites/group derived from a total three independent experiments.

To determine whether p75NTR modulation could affect final common pathways of AD-related spine loss in vivo, effects of LM11A-31 were determined in an APP-mutant AD mouse model, APPL/S, which exhibit amyloid plaques starting at age 3–4 months43 and reduced spine densities by age 7.0–7.5 months (unpublished data, Longo Laboratory). Mice were treated for 3 months with LM11A-31, from age 7.5–8 to 10.5–11 months, at which time tissue was harvested for assessment of hippocampal pyramidal neuron dendritic spines. Compared to wild-type mice, dendrites from APP-L/S mice exhibited a 42% reduction in spine density, while treatment of transgenic mice resulted in median spine densities and distributions matching those of vehicle-treated wild-type mice (Fig. 1E,F). LM11A-31 had no detectable effects on spine density in wild type mice. Since spine density is decreased in these mice at age 7.0–7.5 months when treatment with LM11A-31 began, these findings indicated that LM11A-31 treatment may shift the dynamics of spine formation and regression back towards normal. Notably, prior studies in the APP-L/S model demonstrated that similar treatments with LM11A-31 had no effect on Aβ levels measured by either ELISA or plaque quantitation36,37.

To determine the effects the of p75NTR modulation on Aβ-induced dendritic degeneration, we examined neurite beading, a process linked with tau pathology involving disruption of the microtubule cytoskeleton along with localized accumulation of tau44. Exposure of 21 DIV hippocampal neurons to Aβ resulted in extensive neuritic beading, quantitated as number of beaded morphological profiles per 100 µm process length (Fig. 1G,H). Notably, though the median beading values were not significantly altered by LM11A-31, the distribution of beading across counted segments was significantly shifted towards a reduction in degeneration by the treatment, with a dramatic divergence between the distributions occurring above 10 beads/100 µm (Fig. 1I), with the treated cells trending similar to the control distribution. This pattern may be due to alterations in the kinetics of injury, but the sharp divergence may further suggest that LM11A-31 inhibits the progression to severe involvement, but not the initiation of tau-related Aβ-induced neuritic injury.

Altering p75NTR activities reduces AD-associated forms of tau induced by Aβ

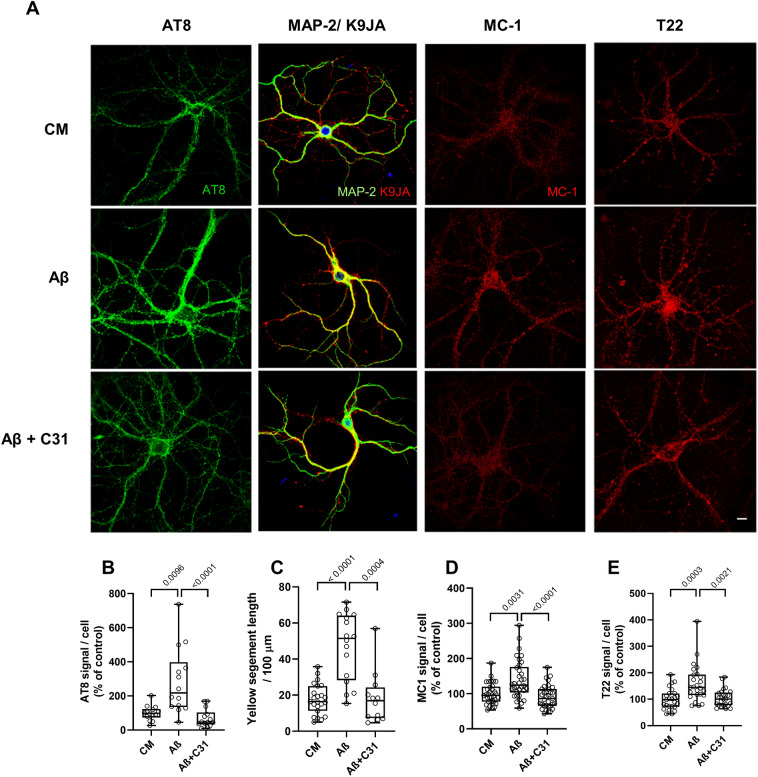

Several tau modifications and configurations, including tau phosphorylation, cleavage, misfolding and missorting, have been proposed to mediate spine and neurite degeneration and dysfunction caused by Aβ45–48. Further, since LM11A-31 inhibited spine and neurite degeneration, and was previously shown to inhibit Aβ-triggered activation of tau kinases GSK3β and cdk5, as well as tau phosphorylation at Ser20219, it was of interest to determine whether one or more additional Aβ-induced tau alterations occurring in hippocampal neurons might be blocked by LM11A-31. Under these conditions, LM11A-31 suppressed Aβ-induced excess levels of Ser202 and Thr205 phosphorylation as reflected by AT8 binding49 (Fig. 2A first column, B). Increased phosphorylation at some sites on tau, including the AT8 sites, is associated with Aβ-provoked redistribution of tau from axons to the somatodendritic compartment46. Tau is predominantly located in axons under normal conditions (CM), while MAP2 is located in dendrites. In Aβ treated cells, tau is redistributed into dendrites, which can be quantified by measuring its colocalization with MAP2. LM11A-31 also inhibited this missorting of tau (Fig. 2A second column, C). The generation of misfolded tau isoforms which can be detected by antibodies such as MC-1, which recognizes an epitope formed by the apposition of two regions at each end of the tau peptide not normally in proximity, is associated with tau phosphorylation and the progression of AD50,51. Further, misfolding is associated with the production of oligmerized tau, considered to be a major toxic species52, which can be detected with the antibody T2253. Here, both MC-1 and T22 signals, which were increased by exposure to Aβ, were diminished by LM11A-31(Fig. 2A third and fourth columns, D,E). Though the co-dependencies and temporal sequences of the generation of these various tau alterations remain subjects of investigation, together these findings indicate that in this in vitro model of Aβ toxicity, LM11A-31 can function downstream of Aβ and broadly upstream of several known tau modifications associated with AD.

Figure 2.

LM11A-31 prevents Aβ-induced tau phosphorylation, missorting, misfolding and oligomer accumulation. (A) Representative immunostaining for tau phosphorylation, missorting, misfolding and oligomer formation in hippocampal neurons. 21 DIV hippocampal neurons were treated with CM or Aβ ± LM11A-31 and immunostained with the indicated antibodies at 4 h for tau phosphorylation (AT8/green), 3 h for coincidence of microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2/green) tau and (K9JA/red) (missorting), 8 h for tau misfolding (MC-1/red) and 48 h for tau oligomerization (T22/red). Scale bar, 10 µm. (B–E) Total fluorescence intensity was measured and ratios of total fluorescence intensity to total cell numbers per field were calculated. (B) n = 14 neurons derived from 3 independent experiments. (C) n = 14–23 neurites derived from 3 independent experiments. (D) n = 30 neurons derived from 5 independent experiments. (E) n = 24 neurons derived from 4 independent experiments. Statistical significance of the indicated comparisons was determined in (C–E) using Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA with post-hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test and in (B) using Regular ANOVA with post-hoc Sidak’s multiple comparison testing.

Tau oligomerization and cleavage in APPL/S mice is inhibited by modulation of p75NTR

Since tau oligomerization likely results from multiple tau metabolic mechanisms, including some which might be present in in vivo but not in in vitro models it was of further interest to determine the effects of modulating p75NTR signaling on the accumulation of tau oligomers in vivo. Mutant APP-based mouse models do not demonstrate neurofibrillary tangles in the absence of human tau, but do form tau oligomers which can be detected with the T22 antibody on Western blots as high molecular weight bands in non-denaturing gels53. Treatment of mice with LM11A-31 resulted in a decrease in the elevated level of T22-binding oligomers > 100 kDa in PBS-soluble extracts present in AβPPL/S mice relative to wildtype, though this did not reach significance (Fig. 3A,B). A ~ 56 kDa band, within the size range of either an oligomer of tau fragments, or alternatively, physiological murine tau54, was significantly increased in APPL/S mice compared to non-transgenic mice (Fig. 3A,C) and though there was an apparent small decrease in this band associated with LM11A-31 exposure, this also did not reach significance. In addition, Tau5 antibody, which detects physiological as well as oligomeric tau forms55, was used to study aggregation. Tau5 detection of tau oligomeric species of ≥ 100 kDa was increased in vehicle treated APPL/S mice compared to wild type but significantly reduced by LM11A-31 treatment (Fig. 3D,E). Of note, T22 and Tau-5 antibodies may recognize different, though overlapping, populations of tau oligomeric species56, derived from a diverse set of functionally distinct conformers57. Signal at ~ 50 kDa MW consistent with tau monomers remained unchanged between wild type and transgenic mice and LM11A-31 had no detectable effect (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

LM11A-31 decreases Aβ-induced tau oligomer accumulation, tau cleavage and injury signaling in vivo. 7.5–8.0-month-old non-transgenic mice (Ntg) and AβPPL/S mice (Tg) were treated with LM11A-31 by oral gavage for 3 months. PBS extract fractions (for tau oligomers and cleavage) and RIPA extracts (for p-JNKT183/Y185, caspase 3/7 and LC3B) from hippocampal tissue were assessed by western blot or ELISA. For western blots, phospho-protein/total-protein or protein-of-interest/actin was determined as indicated; n = 6 mice per group, with three independent western blots averaged per animal. For caspase activity ELISA, n = 6 mice per group, with duplicate wells averaged per animal. (A) T22/oligomeric tau western blot. (B) Quantification of T22 signal > 100 kDa and (C) T22 ~ 56 kDa. (D) Tau 5 total tau western blot. (E) Quantification of Tau-5 (oligomer) signal > 100 kDa and (F) Tau-5 signal ~ 50 kDa (tau monomers). (G) Tau-C3 (cleaved tau) western blot. (H) Tau-C3 signal > 100 kDa. (I) Hippocampal extract caspase 3/7 activity normalized to Ntg-V. (J) Western blot analysis p-JNK/total JNK. (K) Western blot of LC3B/actin. Statistical significance of the indicated comparisons was determined in (B,F,K) using Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA with post-hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test and in (C,E,H,I,J) using Regular ANOVA with post-hoc Sidak’s multiple comparison testing.

Caspase-mediated tau cleavage at Asp421 has been proposed to contribute to tau toxicity58 and oligomer formation59, and cleaved tau is a component of tau oligomers and neurofibrillary tangles. Since Aβ can promote caspase activation12 and tau cleavage59–61, and given that p75NTR has been linked to caspase activation62, it was of interest to examine the effects of p75NTR modulation on accumulation of Asp421-truncated tau in APPL/S mice. Using the tau-C3 antibody which is specific for tau cleaved at Asp421, western blot analysis demonstrated significantly increased levels of this product in APPL/S mice which were largely abolished with LM11A-31 treatment (Fig. 3G,H). To assess potential mechanisms underlying this effect, caspase 3/7 activity, which is responsible for Asp421cleavage, was examined in hippocampal extracts using the Caspase-Glo 3/7 assay. Increased caspase3/7 activity was detected in APPL/S mice compared to wild type mice and treatment with LM11A-31 reduced this activity to baseline levels (Fig. 3I). Since p75NTR signaling may influence JNK activation, which in turn may lead to activation of caspases62,63, JNK activation, as indicated by the generation of phospho-JNK, was measured in these samples. p-JNK levels were increased in transgenic relative to wild type mice and this increase was prevented by LM11A-31 treatment (Fig. 3J).

While the above findings suggested that LM11A-31 might lead to reduced levels of tau oligomers by inhibiting their production, similar effects might occur due to promotion of tau degradation64,65. One major pathway regulating tau turnover and oligomer formation is autophagic activity, which may be reflected by levels of the autophagosome component, autophagy-related protein light chain 3 beta (LC3B). Treatment with LM11A-31 was not found to be associated with increased LC3B signal suggesting that it does not promote decreased oligomer levels through increased autophagic flux (Fig. 3K). Possible contributions of the ubiquitin–proteasome system remain to be assessed in this model. Together with the cell culture data, these in vivo findings provide evidence for several p75NTR/LM11A-31-associated mechanisms which may regulate the production of oligomeric tau isoforms. However, a significant contribution of increased degradation of those forms remains a possibility.

Small molecule-mediated modification of p75NTR signaling reduces Aβ-induced spino- and synaptotoxic Fyn kinase activities

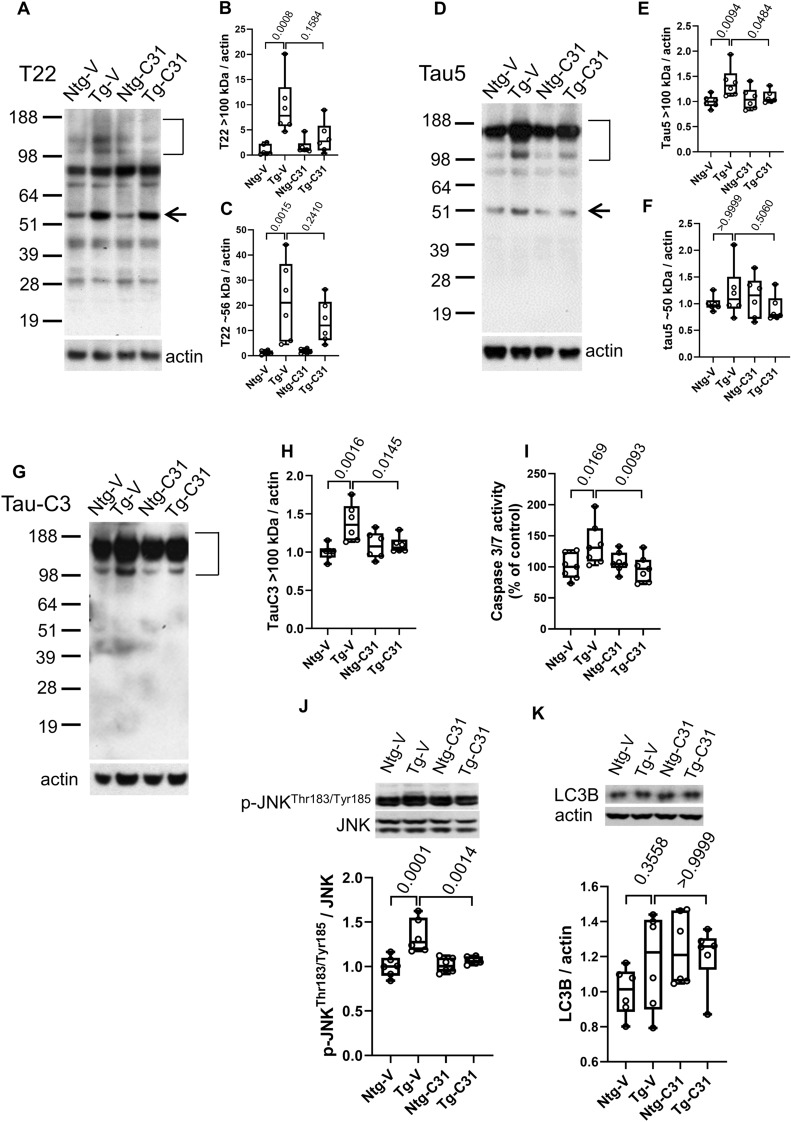

Aβ- and/or tau-related mechanisms may mediate synaptotoxicity through interactions with the protein kinase Fyn. Several lines of evidence suggest that increased missorting of tau and its accumulation in dendrites leads to increased binding to Fyn which facilitates Fyn-mediated phosphorylation of the NR2B subunit of NMDA receptors, which impairs their functions4,66. Since p75NTR signaling has been implicated in activation of Fyn67 and LM11A-31 reduces tau missorting, it was hypothesized that LM11A-31 would inhibit excess Fyn phosphorylation/activation occurring in Aβ-treated neurons. In hippocampal neuron cultures, addition of Aβ led to increased p-FynY416, indicative of Fyn activation68, and this was inhibited in the presence of LM11A-31 (Fig. 4A first row, B). Fyn kinase targets, which may play important roles in synaptotoxicity, include tauY18 and NR2BY1472, both associated with excitotoxic alterations in glutamate transmission66,69,70. Therefore, it was of interest to determine whether LM11A-31-mediated inhibition of Aβ-induced Fyn activation would inhibit accumulation of p-tauY18 and p-NR2BY1472. Treatment of DIV 21 hippocampal neurons with Aβ induced a significant increase in tauY18 and NR2BY1472 phosphorylation and these effects were significantly reduced by LM11A-31 (Fig. 4A middle and bottom rows, C,D). Similar results were obtained on in vivo analysis of p-NR2BY1472 in APPL/S hippocampal tissue (Fig. 4E). Together, these results are consistent with the possibility that LM11A-31 mediated suppression of Fyn activation contributes significantly to the overall effects of the compound on the inhibition of Aβ synaptic toxicity.

Figure 4.

LM11A-31 modulates Aβ-induced Fyn activation and substrate phosphorylation. (A) 21 DIV hippocampal neurons were treated with CM or Aβ ± LM11A-31 and fixed and immunostained with the indicated antibodies after 20 min. Scale bar, 10 µm. (B–D) Total fluorescence intensity was measured and ratios of total fluorescence intensity to total cell numbers per field were calculated. For p-FynY416, n = 18–22 fields derived from 4 independent experiments; p-NR2BY1472, n = 24 fields derived from 6 independent experiments; p-tauY18, n = 30 fields derived from 5 independent experiments. Statistical significance of the indicated comparisons was determined using Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA with post-hoc Dunn’s Multiple Comparisons test. (E) 7.5–8.0 months old non-transgenic mice (Ntg) and AβPPL/S mice (Tg) were treated with LM11A-31 by oral gavage for 3 months. RIPA protein extracts from hippocampal tissue were assessed by western blot analysis and the ratio of phospho-NR2BY1472 to total NR2B protein was determined with normalization to Ntg-V. n = 6 mice per group, with three independent western blots averaged per animal. Statistical significance of the indicated comparisons was determined in (C,D) using Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA with post-hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test and in (B,E) using Regular ANOVA with post-hoc Sidak’s multiple comparison testing.

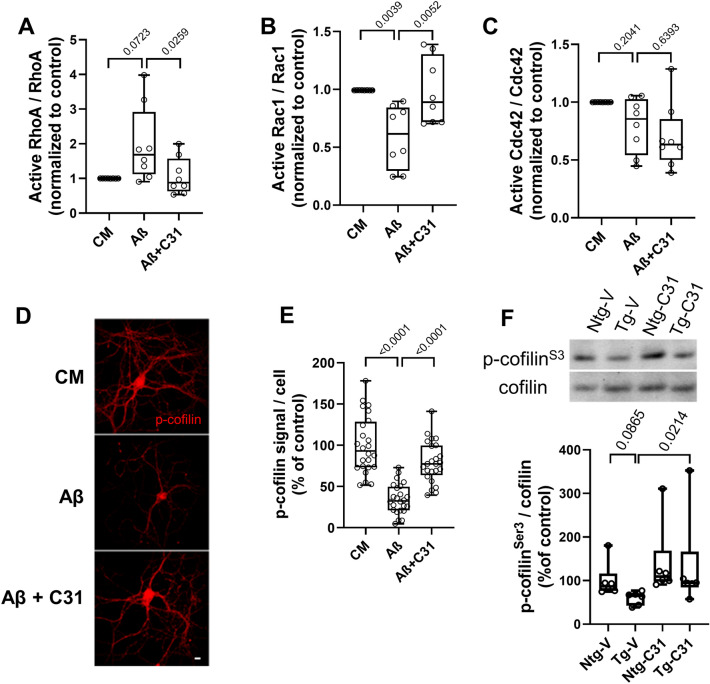

Rho-family GTPase and cofilin responses to Aβ are mitigated by modulation of p75NTR signaling

Rho family GTPases are important regulators of neurite growth and dendritic spine dynamics71. p75NTR modulates RhoA activation and related actin depolymerization72 and Aβ can promote RhoA activation73 in vitro. Since LM11A-31 has been shown to inhibit pathologic excessive RhoA activation in a model of chemotherapeutic agent toxicity74,75, it was theorized that it might work similarly in Aβ toxicity models. Aβ exposure induced Rac1 inactivation in hippocampal neuron cultures and increased median RhoA activation, though the latter did not reach significance, and these effects were inhibited by LM11A-31 (Fig. 5A,B). There was no detectable change in Cdc42 activity nor response to LM11A-31 (Fig. 5C). An important downstream effector regulated by Rho GTPases, cofilin, is a highly conserved actin-binding protein, which plays an essential role in regulating actin filament dynamics and reorganization by stimulating the severing and depolymerization of actin filaments76,77. Aβ oligomer-induced spine loss and reduction of the spine protein drebrin has been linked to dephosphorylation at the cofilin Ser3 residue and resulting actin filament disassembly9,78. In the present study, cofilin phosphorylation at Ser3 was reduced by ~ 60% in hippocampal neurons treated with Aβ (Fig. 5D,E) and this reduction was inhibited by treatment with LM11A-31. Consistent with these in vitro results, and with observations in other AD animal models9, levels of cofilin phosphorylation were reduced in APPL/S mice compared to vehicle treated-non-transgenic mice (Fig. 5F). Notably, these levels were restored by treatment with LM11A-31.

Figure 5.

Aβ-induced changes in cofilin and Rho-family signaling are normalized by LM11A-31. (A–E) 21 DIV hippocampal neurons were treated with CM or Aβ ± LM11A-31 and cells were harvested after one hour for cell extract preparation. (A–C) For each assay measuring RhoA, Rac1 or Cdc42 GTPase, n = 9 protein preparations from independent experiments were measured, each protein preparation was tested using each of the three assays in duplicate and the two values were averaged. (D) Representative immunostaining images for p-cofilinSer3. Scale bar, 10 µm. (E) For p-cofilinS3 quantitation, total fluorescence intensity over total cell number per field was calculated, n = 24 fields derived from a total of 4 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined for the indicated comparisons using Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA with post-hoc Dunn’s Multiple Comparisons test. (F) 7.5–8.0-month-old non-transgenic mice (Ntg) and AβPPL/S mice (Tg) were treated with LM11A-31 by oral gavage for 3 months. RIPA protein extracts from hippocampal tissue were assessed by western blotting for the ratio of p-cofilinSer3 to total cofilin signal. N = 6 mice per group, with the values from three independent western analyses averaged per animal. Statistical significance of the indicated comparisons was determined in (A,B,C,F) using Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA with post-hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons test and in (E) using Regular ANOVA with post-hoc Sidak’s multiple comparison testing.

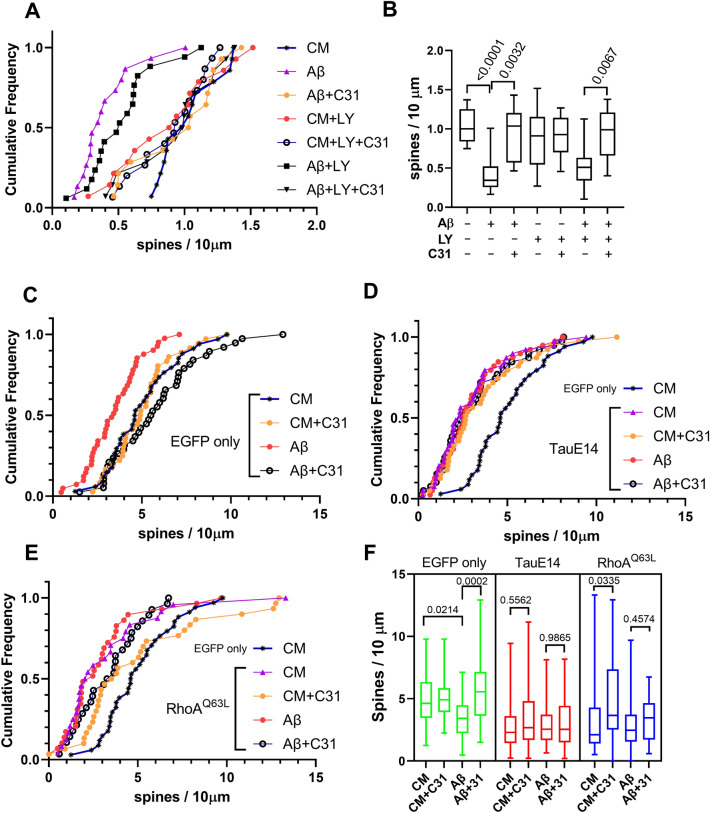

Roles of tau phosphorylation and RhoA activation in the actions of LM11A-31 on Aβ-induced spine density loss

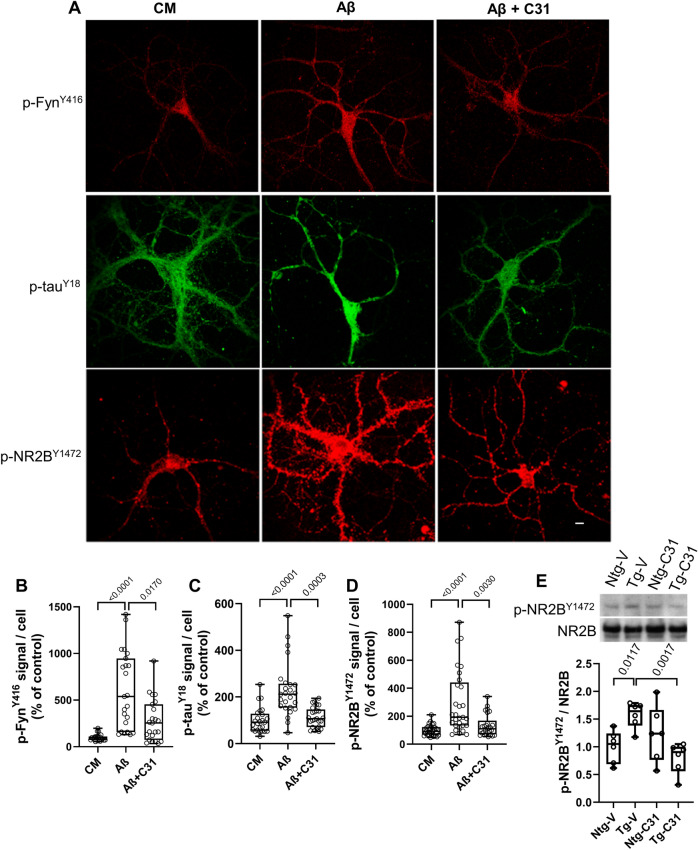

In prior studies, LM11A-31 was shown to inhibit the Aβ-induced reduction of PI3K/AKT activation and increased c-JUN activation19, consistent with known roles of p75 in regulating PI3K/AKT and JNK signaling20. In the present study, addition of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002, previously found to substantially inhibit LM11A-31 support of immature neuron survival35, did not alter the effects of the Aβ oligomers on spines in hippocampal neuron cultures and did not inhibit LM11A-31-mediated restoration of spine densities (Fig. 6A,B). These findings suggest that the protective effect of LM11A-31 is not dependent on its activation of PI3K/AKT signaling.

Figure 6.

LM11A-31 inhibition of Aβ-induced spine loss is dependent on modulation of tau phosphorylation and RhoA activation. (A,B) 21 DIV hippocampal neurons were treated with CM or Aβ ± LM11A-31 with or without LY29002 (a PI3 kinase inhibitor), and examined at 24 h. The number of drebrin-positive spines per dendrite length was measured. (A) Cumulative frequency graph and (B) box plot of the indicated treatment groups. n = 14–16 fields derived from three independent experiments. P values for the indicated comparisons determined by KS testing. (C–F) DIV 20 hippocampal neurons were plasmid transfected for 2 h followed immediately by the addition of CM or Aβ ± LM11A-31. Dendritic spine density was determined after 24 h. (C) Cumulative frequencies of cells transfected with plasmid encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), (D) transfection with tau phosphomimetic, pRK5-EGFP-Tau E14, or (E) transfection with constitutively active RhoA, pcDNA3-EGFP-RhoA-Q63L. Distribution of EGFP/CM samples is included in graphs (D) and (E) as a reference. (F) Summary box plot of all groups. P values for the indicated comparisons determined by KS testing. n = 26–42 neurons for each condition derived from a total of 5 independent experiments.

To further examine the roles of the effects of LM11A-31 on the formation of pathogenic tau conformations and Rho-family GTPase activities in protection of dendritic spines, responses with transfection of mutant forms of tau and RhoA were determined. With an EGFP-only-expressing control plasmid, administration of LM11A-31 inhibited Aβ-induced spine loss (Fig. 6C) similar to the prior EGFP-spine observations (Fig. 1C,D). Preliminary spine density studies with transfection of EGFP-wild type tau found no differences with EGFP alone (Supplementary Figure 6), and the wild-type form was not further assessed. In 21 DIV hippocampal neurons transfected with tauE14 in which all 14 proline-directed serine/threonine phosphorylation sites are mutated to glutamate to emulate hyperphosphorylation79 or RhoAQ63L a constitutively active form of RhoA80, spine densities were significantly decreased (Fig. 6D–F). In cultures transfected with EGFP-tauE14, Aβ caused no additional decreases in spine density and LM11A-31 failed to prevent dendritic spine loss (Fig. 6D,F) either with or without Aβ. These observations provide further support for the idea that the protective effects of LM11A-31 are dependent, at least in part, on its inhibition of tau-mediated spinotoxicity. Since overexpression of wild-type tau does not reduce spines, the result with tauE14 is consistent with prevention of excess tau phosphorylation by LM11A-31 as a protective mechanism; however, effects on other tau-mediated mechanisms may also contribute. In addition, though the lack of further decline in spine density on adding Aβ is consistent with a principal role for pathogenic forms of tau in mediating Aβ-induced decreased spine densities, other Aβ-mediated mechanisms cannot be ruled out, as the effect achieved by tauE14 may represent a floor spine density value. RhoA-activating mutations such as that present in RhoAQ63Lmay increase the level and duration of RhoA activity after neuronal stimulation, effects similar to, but more pronounced than those occurring with wild-type RhoA overexpression71, and are also associated with decreased neuritic spine density81. Neurons transfected with RhoAQ63L, while attaining a reduction in spine density similar to that seen with tauE14 remained partially responsive to LM11A-31, suggesting that the compound may function parallel to or downstream of RhoA activation. In the presence of Aβ, there were no significant differences in distributions or median values with or without LM11A-31 (Fig. 6E,F) suggesting the possibility that the compound’s inhibition of Aβ spinotoxicity is dependent, in part, on its effects on RhoA. Whether this depends on the amount of RhoA, its localization, activity or another aspect of its physiology remains to be determined. These results suggest that to the extent that RhoA activity contributes to Aβ-mediated spinotoxicity, inhibition of RhoA activation may constitute one contributing factor to LM11A-31’s spinoprotective effects.

Discussion

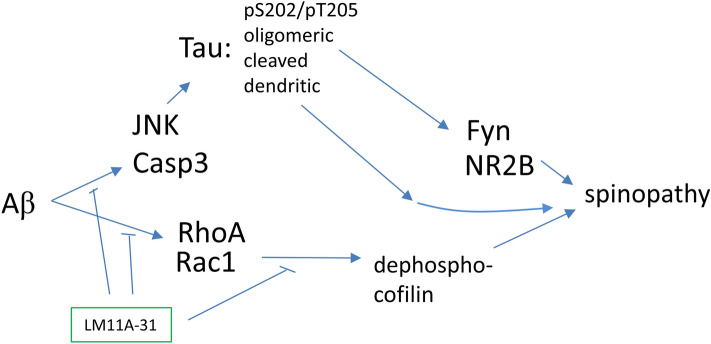

Recent studies involving human subjects and multiple AD mouse models continue to support the hypothesis that Aβ triggers processes promoting neurite and synaptic degeneration through multiple molecular mechanisms, with several, though not all, involving tau-linked molecular pathology82,83. Given the likely limitations of single-mechanism approaches, a major goal is to develop therapeutic strategies capable of blocking as many such degenerative mechanisms as possible; including non-tau- as well as tau-based processes. Prior studies demonstrated that LM11A-31 inhibited Aβ-induced neuronal degeneration and that this effect was lost in cells expressing mutant p75NTR lacking its extracellular ligand-binding domain or in the presence of nerve growth factor (NGF) acting as an LM11A-31 antagonist at p75NTR, suggesting that the protective effect is dependent on targeting p75NTR signaling19. Prior work also demonstrated that LM11A-31 blocks Aβ-induced tau phosphorylation (AT8), activation of calpain, cdk5, c-jun, GSK3β, p38 kinase; and impairment of CREB and AKT activation19,36,37. The present study, focused on tau-related mechanisms, found that LM11A-31 prevents Aβ-induced and tau-linked pathologies including loss of dendritic spines and neurite degeneration, and identified an array of affected tau-related mechanisms through which this protective effect might occur. These include inhibition of tau phosphorylation, cleavage, misfolding, missorting and oligomerization – a novel and broad mechanistic profile in the context of existing AD therapeutic strategies under development. In addition to tau-based processes, LM11A-31 inhibited RhoA/Rac1/cofilin mechanisms that are also known to contribute to spine degeneration. Other effects detected in the APPL/S mouse model included: inhibition of caspase-3/7 activation and tau cleavage, JNK activation, and excess NR2B phosphorylation. Taken together, these in vitro and in vivo findings establish a small molecule therapeutic model based on the inhibition of multiple key Aβ-related degenerative processes (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Model for LM11A-31/p75 modulation of Aβ-induced degenerative signaling. p75 signaling intersects several potentially degenerative Aβ-induced signaling pathways including those involving JNK, caspases and RhoA and that enhance formation of potentially toxic modified forms of tau. The present study points to regulation of tau phosphorylation and RhoA activation as two mechanisms promoted by modulation of p75 signaling likely to contribute to resilience of spine degeneration induced by Aβ.

The ability of LM11A-31 to inhibit accumulation and likely production of misfolded and oligomerized tau points to a new therapeutic category. Currently, two approaches based on direct targeting of tau and evaluated in preclinical studies have entered clinical trials84. One tau-centered method, is the application of tau antisense treatments, which is based on preclinical work showing reduced pathology in APP/Aβ-based tau KO mice85. Potential challenges to this approach include establishing the extent to which a therapeutic window exists in which a chronic reduction of tau does not significantly impair its critical physiologic functions yet substantially inhibits AD pathology. Moreover, the extent to which synaptic failure and degeneration in late onset AD is promoted by tau versus mechanisms unrelated to tau remains an open question. Another tau-based treatment approach is the administration of tau antibodies84. One challenge will involve the effective targeting of likely multiple toxic tau conformers/strains. Another is the possibility that tau toxicity might occur via tau structural intermediates and/or proximal/rapid interactions which are unlikely to be blocked by antibodies directed to the final toxic strain. Finally, limited antibody access within intracellular compartments where pathological forms of tau are likely generated might further impair this approach. The findings in the present study suggest that targeting multiple ‘upstream’ mechanisms affecting formation of pathogenic tau species, while maintaining levels of physiologic/non-oligomeric tau, is a tractable approach to protection against Aβ toxicity.

The principal approach to preventing tau hyperphosphorylation involves direct inhibition of individual tau kinases86–89. This may interfere with their physiologic functions and the possibility remains that the set of tau sites regulated by a given kinase would be insufficient to adequately prevent misfolding and toxic oligomer formation. Indeed, the extent to which small molecule tau kinase inhibitors can block tau misfolding and oligomer formation is not known. Moreover, whether any of these strategies prevent the degeneration of neurites, spines and/or synapses remains to be established.

Interactions of tau missorted into dendritic/spine compartments with the protein kinase Fyn is a proposed pathway by which tau mediates synaptotoxicity4. In this model, missorted tau mediates the ability of Fyn to cause excess phosphorylation of the NR2B subunit of the NMDA receptor4,66,69,90 and tyrosine residues in the proline-rich domain of tau, including Tyr1891,92. Excess phosphorylation of NR2B promotes increased recruitment of PSD95 into a synaptic protein complex resulting in excitotoxicity. The mechanisms of mislocalization are not fully established, but may involve phosphorylation as well as other post-translational modifications of tau, such as acetylation, not examined in this study, but also potentially influenced by LM11A-3193,94. Given the possible major role for tau missorting in promoting early stages of synaptic degeneration46, its correction by LM11A-31 may represent an important aspect of the compound’s spine- and neuritic process-protecting actions.

Truncated or cleaved tau has been proposed to contribute to cognitive impairment in AD95,96. Caspase-3- and calpain-mediated tau cleavage products have been detected in early stages of Aβ-induced neurotoxicity, including prior to tau hyperphosphorylation59,97 and neurite degeneration98. Caspase-3-truncated tau has been detected before the formation of NFTs and cell death60. Caspase-3 activation is elevated in AD99 and Aβ treatment of neurons induced activation of calpain and caspase-3/7 resulting in tau fragmentation100. Activated JNK, in addition to directly phosphorylating tau, can activate caspases via effects on mitochondrial apoptotic pathways11. Caspase-3 activity is increased in the dendritic spines of APP/Aβ transgenic mice and is associated with synaptic deficits101. Finally, genetic knockout and pharmacologic inhibition of caspase-3 rescue cognitive and synaptic deficits in an AD model and LTP deficits caused by soluble Aβ oligomers101,102. Thus, inhibition of JNK and caspase activation along with tau cleavage may each contribute to the protective effects of LM11A-31, representing yet another pathogenic pathway influenced by LM11A-31. Determination of the relative importance of these mechanisms awaits future studies.

The Rho subfamily of small GTPase proteins, which include RhoA, Rac1, Cdc42 and the actin-binding proteins such as cofilin and drebrin play significant roles in regulating actin cytoskeleton and spine dynamics41,103,104. In general, Rac1 and Cdc42 promote spine formation and maturation, whereas RhoA kinase activation is associated with spine retraction and synapse loss through its effects on actin cytoskeletal remodeling105,106. Aβ oligomers trigger a significant increase in RhoA activity in both SY5Y cells and in cultured hippocampal neurons14,73,107,108. Increased RhoA activity has been observed in the Tg2576 AD model, particularly in association with amyloid plaques73 and dystrophic neurites109. Studies in the hAPP J20 (Swedish and Indiana mutations) AD mouse model found a significant correlation between increased RhoA activity, dendritic spine loss and behavioral deficits14. A potential role for the Rho subfamily of small GTPase proteins in AD has also been uncovered in systems biology approaches110.

The state of cofilin phosphorylation modulates its regulation of actin cytoskeletal conformation, a key influence on synaptic spine status111. As noted, RhoA activity, which generally promotes phosphorylation and inactivation of cofilin via ROCK1 and LIMK is increased in AD, however increased cofilin activity has been observed in some AD brain and AD models, with decreased cofilin activation in others9. Recent detailed studies suggest that cofilin activation is spatially and temporally complex, with phosphorylation/inactivation occurring dynamically in post-synaptic densities, where it is associated with synaptic dysfunction and loss, and with dephosphorylated cofilin predominating in other cellular compartments111. Further, in another AD mouse model, phospho/inactive cofilin was found to decrease between 1 and 4 months of age, with a dramatic rise occurring by 10 months9,112. In addition, p21-activated kinase (PAK) has also been implicated as a cofilin kinase, with its activity regulated by p75NTR, possibly though modulation of Rac1113. The known p75NTR modulation of Rho GTPase signaling and the findings here that LM11A-31 inhibits Aβ-driven effects on RhoA and Rac1 and alterations in cofilin activation and spine loss, and that the inhibition of Aβ-induced spine loss does not occur in the presence of constitutively active RhoA, illustrate another arm of the diverse effects promoted by LM11A-31/p75NTR modulation which also have acute effects on synaptic transmission19,114.

Overall, the findings presented here demonstrate a broad set of Aβ pathogenic pathways influenced by LM11A-31/p75 receptor modulation, including inhibition of activation of multiple tau kinases along with reductions in Aβ-induced tau missorting, misfolding, cleavage and oligomerization. The effectiveness in reversing neurite/spine degeneration and lack of apparent deleterious effects indicate that LM11A-31, and more broadly, p75 modulation, may be an approach with significant therapeutic potential.

Methods

Materials

LM11A-31[2-amino-3-methyl-pentanoic acid (2-morpholin-4-yl-ethyl)-amide], was custom manufactured in the HCl salt form by Olon Ricerca Biosciences LLC (Concord, OH). Each preparation was purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and was greater than 99.8% pure. Structure was confirmed by nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. For use in vitro, LM11A-31 was dissolved in water prior to dilution in culture medium. For use in vivo, LM11A-31 was dissolved in water at a concentration of 5 mg/ml and stored at − 20 °C. Aβ1–42 peptide (HFIP form) was purchased from rPeptide (Bogart, GA). Aβ1–42 oligomers were prepared as described previously19. Other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corp (St. Louis, MO), unless otherwise stated.

Hippocampal neuron cultures and treatments

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals using protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Stanford University. Primary embryonic mouse hippocampal neuron cultures were prepared as previously described19. Briefly, neurons were plated on poly-D-lysine-coated (10 µg/ml) glass cover slips at 40,000–50,000 cells per well in 12-well plates (Corning Life Sciences, Tewksbury, MA). Cells were seeded in plating medium DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1 × penicillin/streptomycin (PS) for 2 h. Medium was then changed to Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with PS and B27 (Invitrogen) and 2 mM glutamine. After 21 days under these culture conditions, neurons demonstrate an adult-like phenotype with respect to neuronal polarity, microtubule and neurofilament cytoskeleton architecture, dendritic spines and functional synapses40. At 21 days cells were exposed to oligomeric Aβ at a concentration of 5 µM under conditions described in the “Results” and Figure Legends.

Hippocampal neuron transfection studies

For assessment of dendritic spines, hippocampal neurons in vitro were transfected with a plasmid encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGF; pEGFPN1, Clontech, Mountain View, CA). For analysis of p-tau and RhoA mechanisms, neurons were transfected with pRK5-EGFP-Tau E14 or constitutively active RhoA plasmid pcDNA3-EGFP-RhoA-Q63L (Addgene, Cambridge, MA). Transfections were performed over a 2-h period using Lipofectamine 2000 (EMD Millipore) at 20 days in vitro (DIV) as previously described115. Immediately following the 2-h transfection period, neurons were treated with CM, Aβ, or Aβ with or without concomitant addition of LM11A-31 (100 nM final concentration). After 24 h, neurons were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and slide-mounted with Pro-Long Gold (EMD Millipore). Images of EGFP transfected dendrites were acquired using a Leica DM5500 confocal microscope (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL) with a 63 × objective. Spine density was measured by manual tracing using Neurolucida (MBF Biosciences, Williston, VT) and expressed as the number of spines per 10 µm of dendrite length using measurements obtained for multiple lengths of dendrite (n = number of lengths of dendrite) taken from 4–15 neurons per well across four or five independent neuronal cultures for each experimental condition. Counts were performed by an observer blinded to treatments.

Immunofluorescence

Cultured hippocampal neurons were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 20 min, permeabilized for 6 min in 80% ice-cold methanol, and incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. Primary antibodies used were: rabbit polyclonal tau antibody K9JA (1:1000; DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) and mouse monoclonal MAP2 antibody AP20 (1:1000; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to assess tau missorting; mouse monoclonal phospho-tau antibody AT8 (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and rabbit polyclonal T22 (1:500; EMD Millipore) to measure tau phosphorylation and tau oligomer formation; rabbit polyclonal synaptophysin antibody (1:300; Abcam, Cambridge, MA); MC-1 antibody which detects misfolded murine tau116; rabbit polyclonal tau antibody K9JA and mouse monoclonal α-tubulin antibody (1:1000; Sigma) to visualize neuritic beading. Other antibodies used for immunofluorescence included: mouse monoclonal drebrin antibody (1:300; Enzo, Farmingdale, NY), rabbit polyclonal p-cofilinS3 antibody (1:300; Abcam), rabbit polyclonal p-FynY416 antibody (1:300; Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA); rabbit polyclonal p-NR2BY1472 antibody (1:600; Sigma) and mouse monoclonal p-tauY18 antibody (1:300; Medimabs, Montréal, QC). Secondary antibodies consisted of either donkey anti-rabbit or anti-mouse conjugated with either FITC or Cy3 (1:400; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. West Grove, PA).

G-LISA Rac1, cdc42 and RhoA activation assays

For analysis of Rac1, cdc42 and RhoA activation, Cytoskeleton, Inc. (Denver, CO) G-LISA Rac1, cdc42 and RhoA Activation Assay Biochem Kits were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, hippocampal protein lysates were incubated in Rac1-GTP, RhoA-GTP or cdc42-GTP affinity plates for 30 min. Bound, activated Rac1, cdc42 and RhoA were measured with Rac1, cdc42 or RhoA-specific antibodies as activated/total signal from the same cell lysates.

Caspase-3/7 activity assay

Caspase activity was measured using the luminescent Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay, which reports both caspase 3 and 7 activity, according to manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). One microgram of mouse hippocampal lysate in 25 µL of protein lysis buffer, plus 25 µL of Caspase-Glo 3/7 Reagent were added to each well of a white-walled 96-well plate, followed by incubation for 1 h at 37 °C. Sample luminescence was determined using a SpectraMax/M5 plate-reading luminometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and activity was expressed in relative luminescence units (RLU). Measurements were normalized as a percentage of the culture medium control mean value.

Confocal imaging, quantification and data analysis

Cell culture images were collected by systematic field imaging in a blinded manner using a 63 × objective lens with a Leica DM5500 Confocal microscope. For quantification of pixel fluorescence intensity, UN-Scan-it Gel & Graph Digitizing Software Ver. 6.14 (Silk Scientific Inc, Orem, UT) was used. Signal per cell averages were calculated as the total level of fluorescent antibody-associated signal per field (p-tau AT8S202/205, synaptophysin, PSD95, T22, p-tauY18, p-cofilinS3, p-FynY416 or p-NR2BY1472) divided by the total number of neurons in the field, and were normalized as a percentage of the culture medium control mean value. For quantification of neurite degeneration, Neurolucida (MBF Biosciences) in the manual mode was used to measure the total length of tubulin-positive neurites and the number of tau-positive beads, roughly circular to ovoid swellings arrayed along processes, in each field to yield the average number of tau-positive beads per 100-μm length of neurite for the given set of fields (3–6 fields per well). For quantification of tau missorting, Neurolucida was used manually to measure the total length of MAP2-positive neurites (green) and the length of neurite segments with MAP-2/tau co-localization (yellow) within a field, and the of co-localization length per 100-μm length of MAP2-positive neurites determined. All quantifications were performed in a blinded manner.

AD mouse models, drug treatment, tissue harvesting and neuritic spine analysis

The AD mouse model utilized was the transgenic line Thy-1 hAPP 41B C57BL/6 which expresses the human amyloid precursor protein (APP) 751 (hAPP751) containing the London (V717I) and Swedish (K670M/N671L) mutations under the murine Thy1 promoter (APP-L/S)43. Male APP-L/S mice demonstrate progressive plaque deposition in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus beginning at 3–4 months of age43. One brain hemisphere was processed for modified Golgi staining and spine density measurements of hippocampal pyramidal neurons using established protocols, and the hippocampus of the other hemisphere was isolated for quantitative Western blotting as previously described115,117. Densities of dendritic spines of CA1 pyramidal neurons of the dorsal hippocampus were determined by tracing and marking Golgi-stained hippocampal neurons manually using Neurolucida while adjusting focus at 100X. Minimally overlapping neurons in the same region were selected. All branches from one dendritic tree of each neuron were traced and 3 neurons were analyzed per mouse.

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis

Protein extracts were prepared by homogenizing frozen hippocampal tissue in RIPA lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl; 1% NP-40; 50 mM Tris, pH7.4; 1 mM EDTA; 10% glyceryl, 1 mM PMSF) with Pierce Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Tablets (Cat# A32959, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA)118. Tau oligomer fractions were prepared by homogenizing frozen hippocampal tissue in phosphate buffered saline with a protease inhibitor (Cat#A32955, ThermoFisher) and 0.02% NaN3 using a 1:3 (w/v) dilution. Preparations were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Protein concentration was measured using the Precision Red Advanced Protein Assay (Cytoskeleton, Inc). Supernatants were aliquoted and stored at − 80 °C until use55. For Western blotting, 20–40 µg of total protein from each sample was run per lane on precast NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Gels for SDS-PAGE (ThermoFisher) then transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% nonfat dried milk at room temperature for 1 h, membranes were probed overnight at 4 °C with one of the following antibodies: T22 (1:1000, EMD Millipore); cleaved-tau-Asp421 (1:10,000, EMD Millipore); Tau 5 (1:5000; BioLegend, San Diego, CA); p-JNKT183/Y185 (1:1000, Cell Signaling); JNK (1:1000, Cell Signaling); NR2B (1:1000); p-FynY416 (1:1000, Cell Signaling); Fyn (1:2000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); p-NR2BY1472 (1:1000, BD BioScience, San Jose, CA); actin (1:10,000; Sigma) or L3B (1:3000; Novus Biologicals, LLC, Littleton, CO). Secondary antibodies were either horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000; ThermoFisher) or anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000; DAKO) ECL (GE Healthcare, Sunnyvale, CA). Immunoreactive band densities were measured using Un-Scan-It gel software (Ver. 6.14, Silk Scientific Inc).

Statistical analyses

Graphpad Prism 8 and Microsoft Excel were used for statistical data analysis, with α set at p < 0.05 for all tests. Box-plot graphs display the median (middle line), 25th and 75th percentiles (extent of the box) and range (whiskers) derived from at least three independent experiments. Data normality was determined for each set with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Non-parametric testing with Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA and Dunn’s post-hoc analysis was used when normality testing was not passed, otherwise regular ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison post-hoc testing was utilized for group comparisons as indicated. Outcomes of in vivo experiments included in post-hoc testing were; first, differences between vehicle and drug in the transgenic context; and second, as a measure of quality control, differences between wild type and transgenic mice. Sample distributions were compared with two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) testing.

Ethical approval and informed consent

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals using protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Stanford University.

Supplementary information

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

Amyloid beta

- APP

Amyloid precursor protein

- NMDA

N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor

- NTR

Neurotrophin receptor

- NGF

Nerve growth factor

- EGFP

Enhanced green fluorescent protein

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- p

Phosphorylated

- Rac

Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1

- RhoA

Small GTPase RhoA

- Fyn

Fyn kinase

- KS testing

Kolmogorov–Smirnov testing

Author contributions

T.Y., study design, experimental procedures, data analysis, manuscript preparation; A.Y.Z., study design, experimental procedures, data analysis; K.C.T., experimental procedures, data analysis; S.M.M. and F.M.L., study design, data analysis, manuscript preparation. All authors edited and approved the final version of manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Horngren Family Alzheimer’s Research Fund, Jean Perkins Foundation, Taube Philanthropies, Koret Foundation, General Alzheimer’s Research Donor Fund and Buena Thomas AD Research Fund.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

FML and SMM are listed as inventors on patents relating to a compound in this report that is assigned to the University of North Carolina, University of California, San Francisco and the Dept. of Veterans Affairs. SMM and FML are entitled to royalties distributed by UC and the VA per their standard agreements. FML is a principal of, and has financial interest in PharmatrophiX, a company focused on the development of small molecule ligands for neurotrophin receptors that has licensed several of these patents. TY, KCT and AYZ declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Kevin C. Tran and Anne Y. Zeng.

Contributor Information

Stephen M. Massa, Email: Stephen.Massa@ucsf.edu

Frank M. Longo, Email: longo@stanford.edu

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-77210-y.

References

- 1.Scheff SW, Price DA, Schmitt FA, Mufson EJ. Hippocampal synaptic loss in early Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol. Aging. 2006;27:1372–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boros BD, et al. Dendritic spines provide cognitive resilience against Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 2017;82:602–614. doi: 10.1002/ana.25049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanseeuw BJ, et al. Association of amyloid and Tau with cognition in preclinical Alzheimer disease: a longitudinal study. JAMA Neurol. 2019 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ittner LM, et al. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-beta toxicity in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Cell. 2010;142:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Y, Mucke L. Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell. 2012;148:1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naseri NN, Wang H, Guo J, Sharma M, Luo W. The complexity of tau in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2019;705:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saha P, Sen N. Tauopathy: a common mechanism for neurodegeneration and brain aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2019;178:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zempel H, Mandelkow E. Lost after translation: missorting of Tau protein and consequences for Alzheimer disease. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:721–732. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang DE, Woo JA. Cofilin, a master node regulating cytoskeletal pathogenesis in Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019 doi: 10.3233/JAD-190585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin L, et al. Tau protein kinases: involvement in Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2013;12:289–309. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yarza R, Vela S, Solas M, Ramirez MJ. c-Jun N-terminal Kinase (JNK) signaling as a therapeutic target for Alzheimer's disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2015;6:321. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chong YH, et al. ERK1/2 activation mediates Abeta oligomer-induced neurotoxicity via caspase-3 activation and tau cleavage in rat organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:20315–20325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mead E, et al. Halting of caspase activity protects Tau from MC1-conformational change and aggregation. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54:1521–1538. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pozueta J, et al. Caspase-2 is required for dendritic spine and behavioural alterations in J20 APP transgenic mice. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1939. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lefort R. Reversing synapse loss in Alzheimer's disease: Rho-guanosine triphosphatases and insights from other brain disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2015;12:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s13311-014-0328-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aguilar BJ, Zhu Y, Lu Q. Rho GTPases as therapeutic targets in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2017;9:97. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0320-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee S, Salazar SV, Cox TO, Strittmatter SM. Pyk2 signaling through Graf1 and RhoA GTPase is required for amyloid-beta oligomer-triggered synapse loss. J. Neurosci. 2019;39:1910–1929. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2983-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coulson EJ. Does the p75 neurotrophin receptor mediate Abeta-induced toxicity in Alzheimer's disease? J. Neurochem. 2006;98:654–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang T, et al. Small molecule, non-peptide p75 ligands inhibit Abeta-induced neurodegeneration and synaptic impairment. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longo FM, Massa SM. Small-molecule modulation of neurotrophin receptors: a strategy for the treatment of neurological disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013;12:507–525. doi: 10.1038/nrd4024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu XY, et al. Increased p75(NTR) expression in hippocampal neurons containing hyperphosphorylated tau in Alzheimer patients. Exp. Neurol. 2002;178:104–111. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chakravarthy B, et al. Hippocampal membrane-associated p75NTR levels are increased in Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012;30:675–684. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fahnestock M, Shekari A. ProNGF and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Front. Neurosci. 2019;13:129. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sotthibundhu A, et al. Beta-amyloid(1–42) induces neuronal death through the p75 neurotrophin receptor. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:3941–3946. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0350-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knowles JK, et al. The p75 neurotrophin receptor promotes amyloid-beta(1–42)-induced neuritic dystrophy in vitro and in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:10627–10637. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0620-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy M, et al. Reduction of p75 neurotrophin receptor ameliorates the cognitive deficits in a model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2015;36:740–752. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Maria E, et al. Possible influence of a non-synonymous polymorphism located in the NGF precursor on susceptibility to late-onset Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29:699–705. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-112006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen T, et al. BDNF polymorphism: a review of its diagnostic and clinical relevance in neurodegenerative disorders. Aging Dis. 2018;9:523–536. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersson CH, et al. A genetic variant of the Sortilin 1 gene is associated with reduced risk of Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016;53:1353–1363. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lane RF, et al. Vps10 family proteins and the retromer complex in aging-related neurodegeneration and diabetes. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:14080–14086. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3359-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cozza A, et al. SNPs in neurotrophin system genes and Alzheimer's disease in an Italian population. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15:61–70. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2008-15105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cong W, et al. Genome-wide network-based pathway analysis of CSF t-tau/Abeta1-42 ratio in the ADNI cohort. BMC Genom. 2017;18:421. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3798-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mufson EJ, et al. Hippocampal proNGF signaling pathways and beta-amyloid levels in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2012;71:1018–1029. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318272caab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Counts SE, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid proNGF: a putative biomarker for early Alzheimer's disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2016;13:800–808. doi: 10.2174/1567205013666160129095649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Massa SM, et al. Small, nonpeptide p75NTR ligands induce survival signaling and inhibit proNGF-induced death. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:5288–5300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3547-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knowles JK, et al. Small molecule p75NTR ligand prevents cognitive deficits and neurite degeneration in an Alzheimer's mouse model. Neurobiol. Aging. 2013;34:2052–2063. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen TV, et al. Small molecule p75NTR ligands reduce pathological phosphorylation and misfolding of tau, inflammatory changes, cholinergic degeneration, and cognitive deficits in AbetaPP(L/S) transgenic mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42:459–483. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simmons DA, et al. A small molecule p75NTR ligand, LM11A-31, reverses cholinergic neurite dystrophy in Alzheimer's disease mouse models with mid- to late-stage disease progression. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e102136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lacor PN, et al. Abeta oligomer-induced aberrations in synapse composition, shape, and density provide a molecular basis for loss of connectivity in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:796–807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3501-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zempel H, Mandelkow EM. Linking amyloid-beta and tau: amyloid-beta induced synaptic dysfunction via local wreckage of the neuronal cytoskeleton. Neurodegener. Dis. 2012;10:64–72. doi: 10.1159/000332816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishizuka Y, Hanamura K. Drebrin in Alzheimer's disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017;1006:203–223. doi: 10.1007/978-4-431-56550-5_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tackenberg C, Brandt R. Divergent pathways mediate spine alterations and cell death induced by amyloid-beta, wild-type tau, and R406W tau. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:14439–14450. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3590-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rockenstein E, Mallory M, Mante M, Sisk A, Masliaha E. Early formation of mature amyloid-beta protein deposits in a mutant APP transgenic model depends on levels of Abeta(1–42) J. Neurosci. Res. 2001;66:573–582. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jin M, et al. Soluble amyloid beta-protein dimers isolated from Alzheimer cortex directly induce Tau hyperphosphorylation and neuritic degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:5819–5824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017033108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shipton OA, et al. Tau protein is required for amyloid {beta}-induced impairment of hippocampal long-term potentiation. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:1688–1692. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2610-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zempel H, Thies E, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM. Abeta oligomers cause localized Ca(2+) elevation, missorting of endogenous Tau into dendrites, Tau phosphorylation, and destruction of microtubules and spines. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:11938–11950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2357-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoover BR, et al. Tau mislocalization to dendritic spines mediates synaptic dysfunction independently of neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2010;68:1067–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pooler AM, Noble W, Hanger DP. A role for tau at the synapse in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76(Pt A):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goedert M, Jakes R, Vanmechelen E. Monoclonal antibody AT8 recognises tau protein phosphorylated at both serine 202 and threonine 205. Neurosci. Lett. 1995;189:167–169. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11484-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weaver CL, Espinoza M, Kress Y, Davies P. Conformational change as one of the earliest alterations of tau in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2000;21:719–727. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haroutunian V, Davies P, Vianna C, Buxbaum JD, Purohit DP. Tau protein abnormalities associated with the progression of alzheimer disease type dementia. Neurobiol. Aging. 2007;28:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kopeikina KJ, Hyman BT, Spires-Jones TL. Soluble forms of tau are toxic in Alzheimer's disease. Transl. Neurosci. 2012;3:223–233. doi: 10.2478/s13380-012-0032-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lasagna-Reeves CA, et al. Identification of oligomers at early stages of tau aggregation in Alzheimer's disease. FASEB J. 2012;26:1946–1959. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-199851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brandt R. The tau proteins in neuronal growth and development. Front. Biosci. 1996;1:d118–130. doi: 10.2741/a120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Castillo-Carranza DL, et al. Specific targeting of tau oligomers in Htau mice prevents cognitive impairment and tau toxicity following injection with brain-derived tau oligomeric seeds. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40(Suppl 1):S97–S111. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lo Cascio F, et al. Toxic Tau oligomers modulated by novel curcumin derivatives. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:19011. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55419-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dujardin S, et al. Tau molecular diversity contributes to clinical heterogeneity in Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1256–1263. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0938-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chung CW, et al. Proapoptotic effects of tau cleavage product generated by caspase-3. Neurobiol. Dis. 2001;8:162–172. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gamblin TC, et al. Caspase cleavage of tau: linking amyloid and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:10032–10037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1630428100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rissman RA, et al. Caspase-cleavage of tau is an early event in Alzheimer disease tangle pathology. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:121–130. doi: 10.1172/JCI20640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Basurto-Islas G, et al. Accumulation of aspartic acid421- and glutamic acid391-cleaved tau in neurofibrillary tangles correlates with progression in Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2008;67:470–483. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31817275c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salehi AH, Xanthoudakis S, Barker PA. NRAGE, a p75 neurotrophin receptor-interacting protein, induces caspase activation and cell death through a JNK-dependent mitochondrial pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:48043–48050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shi J, Longo FM, Massa SM. A small molecule p75(NTR) ligand protects neurogenesis after traumatic brain injury. Stem Cells. 2013;31:2561–2574. doi: 10.1002/stem.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee MJ, Lee JH, Rubinsztein DC. Tau degradation: the ubiquitin-proteasome system versus the autophagy-lysosome system. Prog. Neurobiol. 2013;105:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chesser AS, Pritchard SM, Johnson GV. Tau clearance mechanisms and their possible role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. Front. Neurol. 2013;4:122. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2013.00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Um JW, et al. Alzheimer amyloid-beta oligomer bound to postsynaptic prion protein activates Fyn to impair neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2012;15:1227–1235. doi: 10.1038/nn.3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lim YS, et al. p75(NTR) mediates ephrin-A reverse signaling required for axon repulsion and mapping. Neuron. 2008;59:746–758. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thomas SM, Brugge JS. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Larson M, et al. The complex PrP(c)-Fyn couples human oligomeric Abeta with pathological tau changes in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:16857–16871a. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1858-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 70.Miyamoto T, et al. Phosphorylation of tau at Y18, but not tau-fyn binding, is required for tau to modulate NMDA receptor-dependent excitotoxicity in primary neuronal culture. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017;12:41. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0176-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murakoshi H, Wang H, Yasuda R. Local, persistent activation of Rho GTPases during plasticity of single dendritic spines. Nature. 2011;472:100–104. doi: 10.1038/nature09823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yamashita T, Tohyama M. The p75 receptor acts as a displacement factor that releases Rho from Rho-GDI. Nat. Neurosci. 2003;6:461–467. doi: 10.1038/nn1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Petratos S, et al. The beta-amyloid protein of Alzheimer's disease increases neuronal CRMP-2 phosphorylation by a Rho-GTP mechanism. Brain. 2008;131:90–108. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.James SE, et al. Anti-cancer drug induced neurotoxicity and identification of Rho pathway signaling modulators as potential neuroprotectants. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29:605–612. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Friesland A, et al. Amelioration of cisplatin-induced experimental peripheral neuropathy by a small molecule targeting p75 NTR. Neurotoxicology. 2014;45:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sumi T, Matsumoto K, Takai Y, Nakamura T. Cofilin phosphorylation and actin cytoskeletal dynamics regulated by rho- and Cdc42-activated LIM-kinase 2. J. Cell Biol. 1999;147:1519–1532. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Meng Y, Zhang Y, Tregoubov V, Falls DL, Jia Z. Regulation of spine morphology and synaptic function by LIMK and the actin cytoskeleton. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;14:233–240. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2003.14.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shankar GM, et al. Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-beta protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:2866–2875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Khurana V, et al. TOR-mediated cell-cycle activation causes neurodegeneration in a Drosophila tauopathy model. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:230–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mayer T, Meyer M, Janning A, Schiedel AC, Barnekow A. A mutant form of the rho protein can restore stress fibers and adhesion plaques in v-src transformed fibroblasts. Oncogene. 1999;18:2117–2128. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tashiro A, Yuste R. Regulation of dendritic spine motility and stability by Rac1 and Rho kinase: evidence for two forms of spine motility. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2004;26:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Morris M, Maeda S, Vossel K, Mucke L. The many faces of tau. Neuron. 2011;70:410–426. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Scholl M, Maass A. Does early cognitive decline require the presence of both tau and amyloid-beta? Brain. 2020;143:10–13. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Congdon EE, Sigurdsson EM. Tau-targeting therapies for Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018;14:399–415. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0013-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Roberson ED, et al. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid beta-induced deficits in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316:750–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1141736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Garcia-Barroso C, et al. Tadalafil crosses the blood-brain barrier and reverses cognitive dysfunction in a mouse model of AD. Neuropharmacology. 2013;64:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Onishi T, et al. A novel glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitor 2-methyl-5-(3-{4-[(S)-methylsulfinyl]phenyl}-1-benzofuran-5-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole decreases tau phosphorylation and ameliorates cognitive deficits in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 2011;119:1330–1340. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gong EJ, et al. Morin attenuates tau hyperphosphorylation by inhibiting GSK3beta. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011;44:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang X, et al. Diaminothiazoles modify Tau phosphorylation and improve the tauopathy in mouse models. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:22042–22056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.436402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mondragon-Rodriguez S, et al. Interaction of endogenous tau protein with synaptic proteins is regulated by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-dependent tau phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:32040–32053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.401240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bhaskar K, Yen SH, Lee G. Disease-related modifications in tau affect the interaction between Fyn and Tau. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:35119–35125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee G, et al. Phosphorylation of tau by fyn: implications for Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:2304–2312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4162-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sohn PD, et al. Acetylated tau destabilizes the cytoskeleton in the axon initial segment and is mislocalized to the somatodendritic compartment. Mol. Neurodegener. 2016;11:47. doi: 10.1186/s13024-016-0109-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Guo T, Noble W, Hanger DP. Roles of tau protein in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;133:665–704. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1707-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Means JC, et al. Caspase-3-dependent proteolytic cleavage of tau causes neurofibrillary tangles and results in cognitive impairment during normal aging. Neurochem. Res. 2016;41:2278–2288. doi: 10.1007/s11064-016-1942-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kim Y, et al. Caspase-cleaved tau exhibits rapid memory impairment associated with tau oligomers in a transgenic mouse model. Neurobiol. Dis. 2016;87:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Reifert J, Hartung-Cranston D, Feinstein SC. Amyloid beta-mediated cell death of cultured hippocampal neurons reveals extensive Tau fragmentation without increased full-length tau phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:20797–20811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.234674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]