Key Points

Question

What is the nutritional quality of foods and beverages depicted in the 250 top-grossing US movies from 1994 to 2018?

Findings

This qualitative study found that, across 14 946 foods and beverages, 73% of movies earned less healthy food nutrition ratings and 90% earned less healthy beverage ratings, even though only 12% of foods and beverages were visibly branded products. Moreover, the movie-depicted diet failed federal recommendations for saturated fat by 25%, fiber by 45%, and sodium by 4% per 2000 kcal, featuring 16% higher sugar content and 313% higher alcoholic content per 2000 kcal than US individuals actually consume.

Meaning

This study suggests that popular US movies depict an unhealthy diet; depicting unhealthy foods and beverages in media is a sociocultural problem that extends beyond advertisements.

Abstract

Importance

Many countries now restrict advertisements for unhealthy foods. However, movies depict foods and beverages with nutritional quality that is unknown, unregulated, and underappreciated as a source of dietary influence.

Objective

To compare nutritional content depicted in top-grossing US movies with established nutrition rating systems, dietary recommendations, and US individuals’ actual consumption.

Design and Setting

In this qualitative study, a content analysis was performed from April 2019 to May 2020 of the 250 top-grossing US movies released from 1994 to 2018.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The proportion of movies with less healthy nutrition ratings using the Nutrient Profile Index, the proportion of movies with medium or high food nutrition ratings according to the United Kingdom’s “traffic light” guidelines (in which green is low and indicates the healthiest foods; amber, medium; and red is high and indicates the least healthy foods), and how the movie-depicted nutritional content compared with US Food and Drug Administration–recommended daily levels and US individuals’ actual consumption according to National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2015-2016 data. Secondary outcomes compared branded and nonbranded items and tested whether outcomes changed over time or for movies targeting youths.

Results

Across 9198 foods and 5748 beverages, snacks and sweets (2173 [23.6%]) and alcoholic beverages (2303 [40.1%]) were most commonly depicted. Alcohol comprised 23 of 127 beverages (18.1%) in G-rated movies, 268 of 992 beverages (27.0%) in PG-rated movies, 1503 of 3592 beverages (41.8%) in PG-13–rated movies, and 509 of 1037 beverages (49.1%) in R-rated movies. Overall, 178 of 245 movies (72.7%) earned less healthy Nutrient Profile Index food ratings and 222 of 246 movies (90.2%) earned less healthy beverage ratings, which would be unhealthy enough to fail legal limits for advertising to youths in the United Kingdom. Among foods, most movies depicted medium or high (amber or red traffic light) levels of sugar (229 of 245 [93.5%]), saturated fat (208 of 245 [84.9%]), total fat (228 of 245 [93.1%]), and, to a lesser extent, sodium (123 of 245 [50.2%]). Only 1721 foods and beverages (11.5%) were visibly branded, but branded items received less healthy nutrition ratings than nonbranded items. Overall, movies failed recommended levels of saturated fat per 2000 kcal by 25.0% (95% CI, 20.6%-29.9%), sodium per 2000 kcal by 3.9% (95% CI, 0.2%-7.9%), and fiber per 2000 kcal by 45.1% (95% CI, 42.9%-47.0%). Movies also depicted 16.5% (95% CI, 12.3%-21.0%) higher total sugar content per 2000 kcal and 313% (95% CI, 298%-329%) higher alcohol content per 2000 kcal than US individuals consume. Neither food nor beverage nutrition scores improved over time or among movies targeting youths.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study suggests that popular US movies depict an unhealthy diet that fails national dietary recommendations, akin to US individuals’ actual diets. Depicting unhealthy consumption in media is a sociocultural problem that extends beyond advertisements and branded product placements.

This qualitative study compares nutritional content depicted in the 250 top-grossing US movies from 1994 to 2018 with established nutrition rating systems, dietary recommendations, and US individuals’ actual consumption.

Introduction

Advertisements for unhealthy foods and beverages are aired worldwide, target youths, and are associated with consumption behavior.1,2,3 In response, at least 16 countries, including the United Kingdom (but excluding the United States), restrict unhealthy food advertisements to youths in some capacity.4,5 Although advertisements have been extensively studied,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 foods and beverages are also frequently depicted to worldwide audiences in popular cultural media, such as movies.10,11,12 Compared with advertising, these cultural mainstays have been underappreciated as a source of dietary influence.

Movies, as cultural products, may reflect norms regarding which foods and beverages are valued and representative of a culture.13,14,15 Beyond mere reflection, however, movies may actively influence viewers’ health behaviors. Cohort studies show that exposure to movie depictions of smoking and alcohol use during a 1- to 2-year period was associated with increased smoking16,17 and alcohol use18,19 at follow-up for adolescents who had never previously tried smoking or drinking. Results of laboratory experiments also show that children and adolescents who were randomly assigned to view movies with high (vs low) placement of an unhealthy snack were 2.5 to 3 times more likely to choose the featured snack immediately after viewing.20,21 These findings suggest that foods and beverages depicted in movies have the potential to influence viewers’ consumption.

If movies influence viewers’ health behaviors, then it is important to know the nutritional quality of the foods and beverages that they depict. Prior studies quantified alcoholic beverage depictions in movies,10 identified branded food and nonalcoholic beverage placements in movies,11 and qualitatively rated foods and beverages depicted in movies as healthy, mixed, or unhealthy.12 Yet a detailed nutritional analysis and comparison with regulatory nutrition indices, federal dietary recommendations, and information on US individuals’ actual consumption is lacking, to our knowledge. What proportion of movies depict foods and beverages that would pass advertising laws in countries that restrict unhealthy advertisements? Does the diet depicted in movies meet federal guidelines for recommended daily intake, and how does it compare with what US individuals actually consume?

This study presents a comprehensive nutritional analysis of 14 946 foods and beverages depicted in the 250 top-grossing US movies from 1994 to 2018. We tested whether the movie-depicted foods and beverages would pass legal advertising limits in countries that restrict unhealthy advertisements, would meet federal recommended daily intake levels set by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and would be healthier or less healthy than the average US individual’s actual diet based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The 25-year time span allowed us to examine trends over the most recent 25 years. In addition, we tested for differences by target audience using the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) ratings (G [general audiences—all ages admitted], PG [parental guidance suggested—some material may not be suitable for children], PG-13 [parents strongly cautioned—some material may be inappropriate for children under 13 years], and R [restricted—children under 17 years require accompanying parent or adult guardian]) and compared branded and nonbranded foods and beverages.

Methods

Movie Sample

The 250 movies with the highest US domestic box office gross revenues between 1994 and 2018 (top 10 highest-grossing movies per year) were included.22 Movie metadata (eTable 1 in the Supplement) regarding MPAA rating, production studio, budget, and domestic box office sales were obtained from the Internet Movie Database in February 2020.22 Stanford University determined that this research did not require institutional review board approval because it did not involve human participants. This study followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) reporting guideline.

Identification of Foods and Beverages

Two trained researchers (B.P.T. and I.J.H.-M.) viewed movies in their entirety and content-coded all foods and beverages depicted in each scene. A scene was defined as a continuous time span occurring in the same setting. Scenes involving flashbacks, rapid changes in setting set to music, car chases, or extended fight scenes were coded as 1 continuous scene. Researchers paused, rewatched, and slowed down scenes as many times as necessary for clarification. Foods and beverages were coded as precisely as possible (eg, “chocolate ice cream on a sugar cone” instead of “ice cream,” “Monster energy drink” instead of “energy drink”), regardless of positioning on the screen and including empty food and beverage containers (additional coding details in eTable 2 and the eMethods in the Supplement). Foods and beverages appearing multiple times in the same scene were coded only once.

Food and Beverage Categories

To quantify the frequency of food and beverage categories and subcategories depicted, we used the What We Eat In America 2015-2016 categories and subcategories from the US Department of Agriculture.23 Beverages were sorted into 8 categories (alcoholic beverages, water, dairy beverages, coffee and tea, sweetened beverages, 100% juices, diet beverages, and infant formula and human milk), and foods were sorted into 11 categories (dairy, grains, proteins, fruits, vegetables, snacks and sweets, mixed dishes, fats and oils, condiments and sauces, sugars, and protein and nutritional powders), each with multiple subcategories.

Calculating Nutritional Content

To evaluate the nutritional content of each food and beverage, we consulted the US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS) 2015-2016,24 which provides standard nutrition information per 100 g for more than 8600 unique foods and beverages. For foods and beverages with a single relevant code in the FNDDS (eg, Snickers bar), nutrient values for that code were used. For items with multiple relevant codes (eg, cookies), the most specific FNDDS code that was applicable for each observation was used (eg, “cookie, chocolate chip” for chocolate chip cookies). Otherwise, the “not further specified” FNDDS code was used, which provides nutrition information for a general form of that food or beverage (eg, “cookie, not further specified”). See the eMethods in the Supplement for additional details.

Monitoring Coder Reliability

As is standard practice,10,11,12,17,25 interrater reliability between the 2 coders was rigorously monitored at each step (eMethods in the Supplement) and ranged from substantial to almost perfect agreement26 for the presence of a food or beverage (κ = 0.91-0.93), food or beverage type depicted (κ = 0.73-1.00), number of food- and beverage-containing scenes per movie (r = 0.96-0.97), category represented by each unique food or beverage (κ = 0.85-1.00), and FNDDS nutrition code (92%-98% agreement).

Classifying Nutritional Content

To evaluate the healthiness of food and beverage nutritional content, 2 established nutrition rating systems were used that represent enacted law in the United Kingdom, one of the aforementioned countries that regulates food and beverage advertising to youths.4,5,27,28,29 As in prior research on food and beverage advertising,7,8,9,28 we first generated a summary nutrition score from 0 (least healthy) to 100 (healthiest) using the Nutrient Profile Index (NPI).4,27,28 The NPI penalizes 4 components that should be limited (sugar, sodium, energy, and saturated fat) and rewards 3 components that are encouraged (fiber, protein, and fruit and vegetable content) to classify foods and beverages as healthier (food NPI score ≥64 and beverage NPI score ≥70) or less healthy (food NPI score <64 and beverage NPI score <70) (eFigures 1 and 2 in the Supplement). Foods and beverages classified as less healthy are illegal to advertise to youths in the United Kingdom.4 Second, we used the United Kingdom’s front-of-package “traffic light” rating guidelines29 to classify sugar, sodium, saturated fat, and total fat content as low (green traffic light; healthiest), medium (amber traffic light), or high (red traffic light; least healthy) among foods (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). Traffic light ratings were not used for beverages because few beverages contain sodium or fat.

Critically, neither rating system depends on portion size, which would be unknowable in many movie depictions (eg, scenes depicting grocery aisles or produce markets), particularly when characters do not consume the depicted foods. Rather, NPI and traffic light ratings classify the nutritional quality of a 100-g sample of a food or beverage.4,27,28,29 These rating systems are better suited for observational studies of food and beverage products7,8,9,28 compared with other established rating systems that are intended for evaluating individuals’ consumption (including serving sizes) over 24 hours, such as the Alternate Healthy Eating Index–201030 or American Heart Association Healthy Diet Score.31,32

Comparison With Federal Recommended Daily Values

For comparison with federal dietary recommendations, we consulted FDA recommended daily levels per 2000 kcal: 78 g of total fat, 20 g of saturated fat, 2300 mg of sodium, 28 g of fiber, and 1 alcoholic drink (14 g of alcohol).33 Although recommendations also limit added sugars to 50 g, the FNDDS does not provide data on added sugars. Therefore, only results of total sugars are presented. Recommended values were compared with model-estimated, movie-depicted values per 2000 kcal (eMethods in the Supplement).

Comparison With US Individuals’ Actual Dietary Intake

To compare movie-depicted nutritional content and food and beverage categories with US individuals’ consumption, we consulted the NHANES 2015-2016,23,34 a nationally representative survey of US individuals’ consumption. Data (8506 individuals, all ages) for amounts of total fat, saturated fat, sugars, sodium, alcohol, and fiber per 2000 kcal of food and beverage intake34 were compared with model-estimated movie-depicted values per 2000 kcal (eMethods in the Supplement). In addition, because food groups (eg, fruits, vegetables, and processed meats) are relevant health metrics,30,31,32,35 the proportion of What We Eat In America food and beverage categories and subcategories that comprise the US diet23 were also compared with proportions depicted in movies.

Statistical Analysis

To calculate nutrition scores, we used a random intercept model from the lmerTest package36 in R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).37 The model estimated the outcome (eg, NPI nutrition score) with a random intercept effect of scenes nested within movies. Secondary outcomes were tested using mixed-effects models that assessed the outcome as a function of release year (continuous variable, with 1994 coded as 0, 1995 as 1, and so on, through 2018 coded as 24), MPAA rating (factor coded), or branding (factor coded), with a random intercept effect of scenes nested within movies. These mixed-effects models account for the nonindependence of observations that co-occurred within scenes and movies, representing the nested structure of the data. Statistical tests were 2-sided and P < .05 or 95% CIs that excluded zero were considered statistically significant.

Results

Together, these 250 movies sold 10 billion domestic box office tickets and grossed $164 billion in theaters worldwide.22 This indicates high domestic and international exposure, and does not account for extensive additional exposure via home-viewing. Most of the films (219 [87.6%]) targeted or were accessible to youths, with MPAA ratings of G, PG, or PG-13 (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Food and Beverage Categories

Nearly every movie featured at least 1 food scene (245 [98.0%]) and at least 1 beverage scene (246 [98.4%]), for a total of 9198 foods and 5748 beverages. Snacks and sweets were the most common food category depicted (2173 [23.6%]), followed by fruits (2053 [22.3%]), vegetables (1324 [14.4%]), proteins (900 [9.8%]), and grains (833 [9.1%]; eTable 3 in the Supplement). Among beverages (eTable 4 in the Supplement), 2303 (40.1%) were alcoholic beverages, followed by coffee and tea (1323 [23.0%]), water (881 [15.3%]), sweetened beverages (790 [13.7%]), dairy beverages (223 [3.9%]), and 100% juices (169 [2.9%]).

Nutrition Quality Ratings

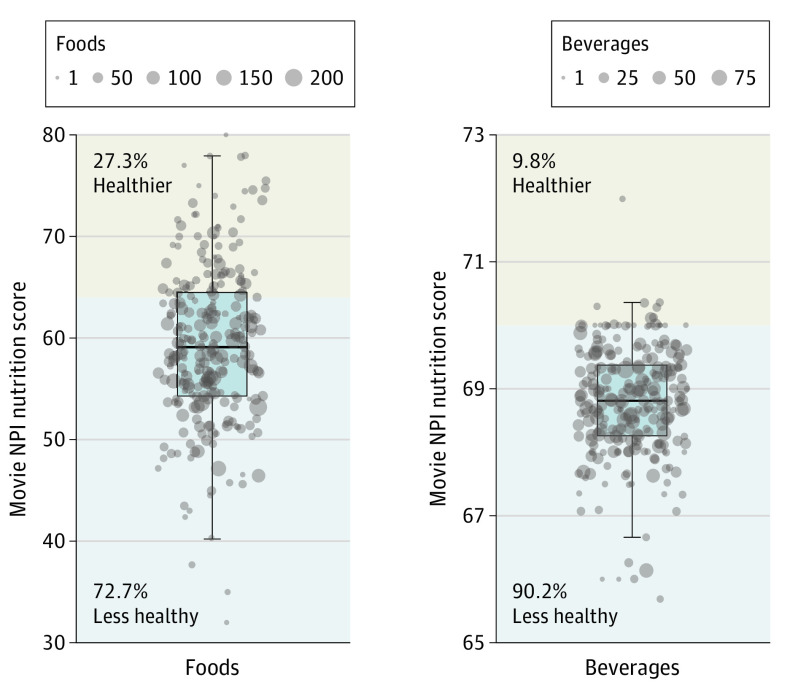

Results of NPI nutrition ratings showed that 178 of 245 movies (72.7%) received a less healthy food nutrition score and that 222 of 246 movies (90.2%) received a less healthy beverage nutrition score (Figure 14; eTable 5 in the Supplement). Thus, 73% of these movies would fail legal advertising limits in the United Kingdom for food, and 90% would fail limits for beverages.4 Results of traffic light ratings additionally showed that, for foods, most movies depicted medium or high levels of sugar (229 of 245 [93.5%]), saturated fat (208 of 245 [84.9%]), total fat (228 of 245 [93.1%]), and, to a lesser extent, sodium (123 of 245 [50.2%]) (eFigure 4 and eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Movie-Level Nutrient Profile Index (NPI) Nutrition Ratings.

Movie-level NPI nutrition ratings for foods (245 movies with food scenes) and beverages (246 movies with beverage scenes). The upper regions represent nutrition scores classified as healthier, and the lower regions represent nutrition scores classified as less healthy by the NPI, which would fail legal advertising limits to youths in the United Kingdom.4 Each boxplot inner horizontal line represents the median, boxes represent the interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles), and vertical lines represent 1.5 times the interquartile range. Dot size corresponds to the number of foods or beverages per movie.

Food and Beverage Branding

Only 11.5% (n = 1721) of all foods and beverages were visibly branded—8.5% (n = 783) of foods and 16.3% of beverages (n = 938). The eResults in the Supplement verify that this small proportion of branded items was accurate, as our observed frequency of branded foods and beverages was very similar to frequencies reported in prior independent investigations of only branded foods and beverages.11,25 Branded foods (eTable 6 in the Supplement) were dominated by snacks and sweets (478 [61.0%]), followed by grains (109 [13.9%]), mixed dishes (64 [8.2%]), and condiments and sauces (56 [7.2%]). The most common branded foods (eTable 7 in the Supplement) were Tabasco hot sauce, Lay’s chips, and Hostess pastries. Branded beverages (eTable 8 in the Supplement) were primarily alcoholic beverages (389 [41.5%]) and sweetened beverages (383 [40.8%]), with Budweiser or Bud Light, Coca-Cola or Diet Coke, and Pepsi or Diet Pepsi as the most common brands (eTable 9 in the Supplement). We did not include branded restaurant storefronts in analyses but noted 109 appearances (eTable 10 in the Supplement), led by McDonald’s and Starbucks. Branded foods received significantly less healthy NPI nutrition scores than nonbranded foods (45.6 [95% CI, 43.9-47.2] vs 60.1 [95% CI, 59.3-61.0]; P < .001) and contained significantly more sugar (24.1 g [95% CI, 22.4-25.9 g] vs 14.4 g [95% CI, 13.5-15.3 g]; P < .001), sodium (416 mg [95% CI, 383-450 mg] vs 302 mg [95% CI, 288-317 mg]; P < .001), saturated fat (4.7 g [95% CI, 4.3-5.2 g] vs 3.0 g [95% CI, 2.8-3.1 g]; P < .001), and total fat (14.7 g [95% CI, 13.5-15.9 g] vs 9.3 g [95% CI, 8.9-9.8 g]; P < .001) per 100 g of food than nonbranded foods (Table 1). Branded beverages also received significantly less healthy NPI nutrition scores than nonbranded beverages (68.1 [95% CI, 67.9-68.3] vs 68.9 [95% CI, 68.8-69.0]; P < .001) and contained significantly more sugar per 100 g of beverage than nonbranded beverages (5.0 g [95% CI, 4.6-5.3 g] vs 1.8 g [1.6-2.0 g]; P < .001). A greater proportion of branded items received amber or red traffic light ratings (medium or high levels) for all nutrients compared with nonbranded items (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Nutritional Content of Branded and Nonbranded Foods and Beverages Depicted in Movies.

| Outcomea | Branded | Nonbranded | Difference | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPI food nutrition score (95% CI)b | 45.6 (43.9 to 47.2) | 60.1 (59.3 to 61.0) | −14.6 (−16.1 to −13.0) | <.001 |

| NPI beverage nutrition score (95% CI)c | 68.1 (67.9 to 68.3) | 68.9 (68.8 to 69.0) | −0.8 (−1.0 to −0.6) | <.001 |

| Sugar per 100 g of food, g (95% CI) | 24.1 (22.4 to 25.9) | 14.4 (13.5 to 15.3) | 9.7 (8.1 to 11.3) | <.001 |

| Sugar per 100 g of beverage, g (95% CI) | 5.0 (4.6 to 5.3) | 1.8 (1.6 to 2.0) | 3.1 (2.8 to 3.4) | <.001 |

| Saturated fat per 100 g of food, g (95% CI) | 4.7 (4.3 to 5.2) | 3.0 (2.8 to 3.1) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.2) | <.001 |

| Total fat per 100 g of food, g (95% CI) | 14.7 (13.5 to 15.9) | 9.3 (8.9 to 9.8) | 5.4 (4.1 to 6.6) | <.001 |

| Sodium per 100 g of food, mg (95% CI) | 416 (383 to 450) | 302 (288 to 317) | 114 (81 to 147) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: NPI, Nutrient Profile Index.

Model outputs are from a linear mixed-effects regression model assessing the outcome as a function of year released plus a random intercept effect of scene nested within movie.

NPI food scores below 64 are rated as less healthy.

NPI beverage scores below 70 are rated as less healthy.

Trends Over Time

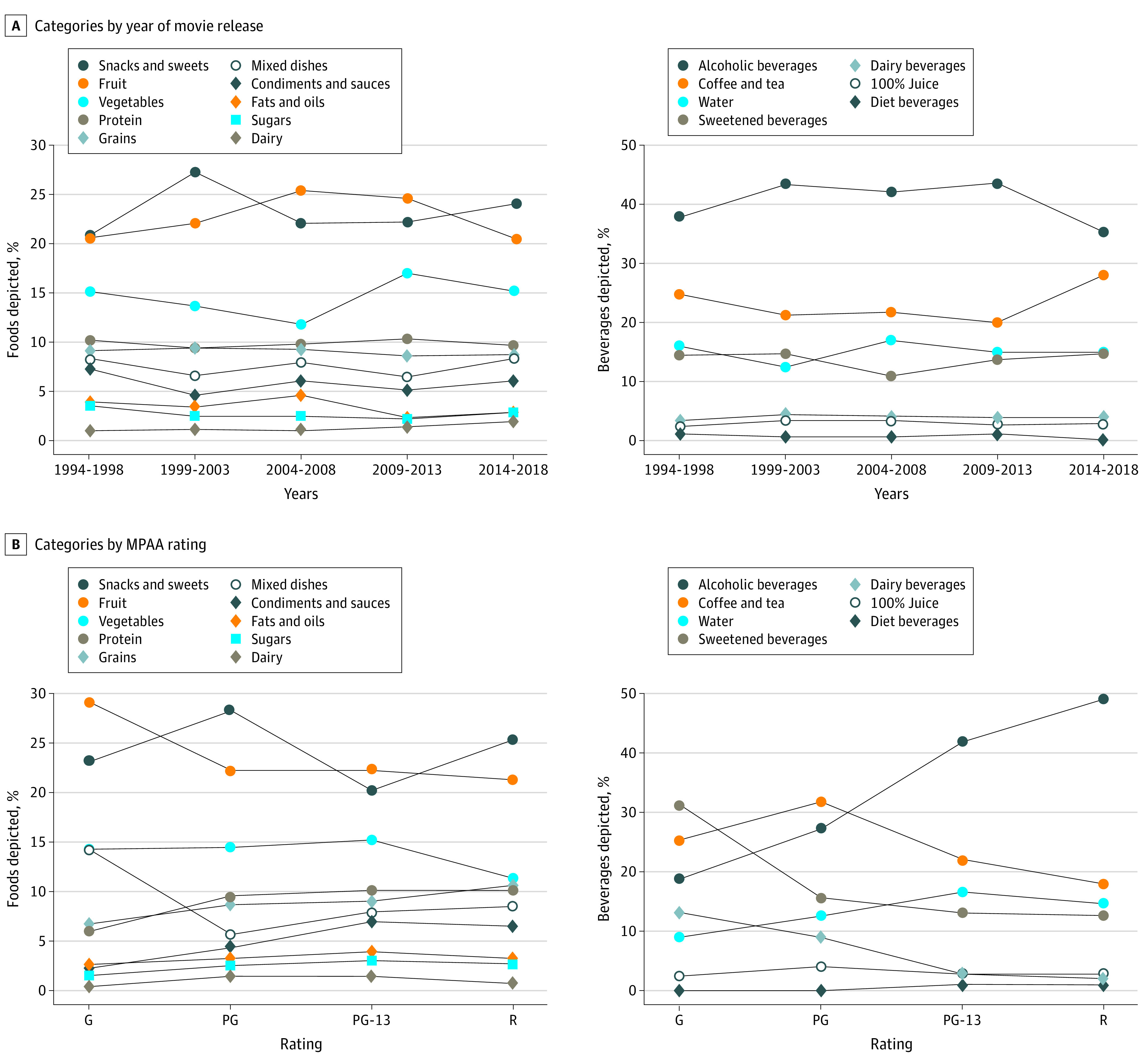

Longitudinal analyses showed no significant improvement in NPI nutrition score over time for foods (b = 0.07 points per year [95% CI, –0.05 to 0.19]; P = .23) or beverages (b = 0.00 [95% CI, –0.01 to 0.02]; P = .53) (eFigure 5A and eTable 11 in the Supplement). The prevalence of individual food and beverage categories was also relatively stable over time (Figure 2A). We found no evidence of improvement over time in sugar, saturated fat, total fat, or sodium content of foods or in sugar content of beverages (eTable 11 in the Supplement). Exploratory sensitivity analyses that controlled for MPAA rating in each longitudinal analysis yielded similar results.

Figure 2. Trends in What We Eat In America (WWEIA) Food and Beverage Categories Over Time and by Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) Rating.

A, WWEIA categories of foods and beverages by year of movie release (5-year means). B, WWEIA categories of foods and beverages by MPAA rating. G indicates general audiences—all ages admitted; PG, parental guidance suggested—some material may not be suitable for children; PG-13, parents strongly cautioned—some material may be inappropriate for children under 13 years; and R, restricted—children under 17 years require accompanying parent or adult guardian.

Trends by MPAA Rating

Analyses by MPAA rating showed that neither food nor beverage movie nutrition scores significantly differed by target audience (eFigure 5B and eTable 12 in the Supplement). The proportions of individual food categories were relatively stable across MPAA ratings, but for beverages, the proportion of alcoholic beverages increased sharply as MPAA rating increased (Figure 2B). In G-rated movies, nearly 1 in 5 beverages (23 of 127 [18.1%]) was alcoholic, as were 268 of 992 beverages (27.0%) in PG-rated movies, 1503 of 3592 beverages (41.8%) in PG-13 movies, and almost half of beverages (509 of 1037 [49.1%]) in R-rated movies. Because sweetened beverages comprised a greater proportion of beverages in movies targeting younger audiences, the beverage sugar content was higher in movies targeting younger audiences (eTable 12 in the Supplement). See the eResults in the Supplement for further exploratory results by MPAA rating.

Comparison With Federal Recommended Daily Values

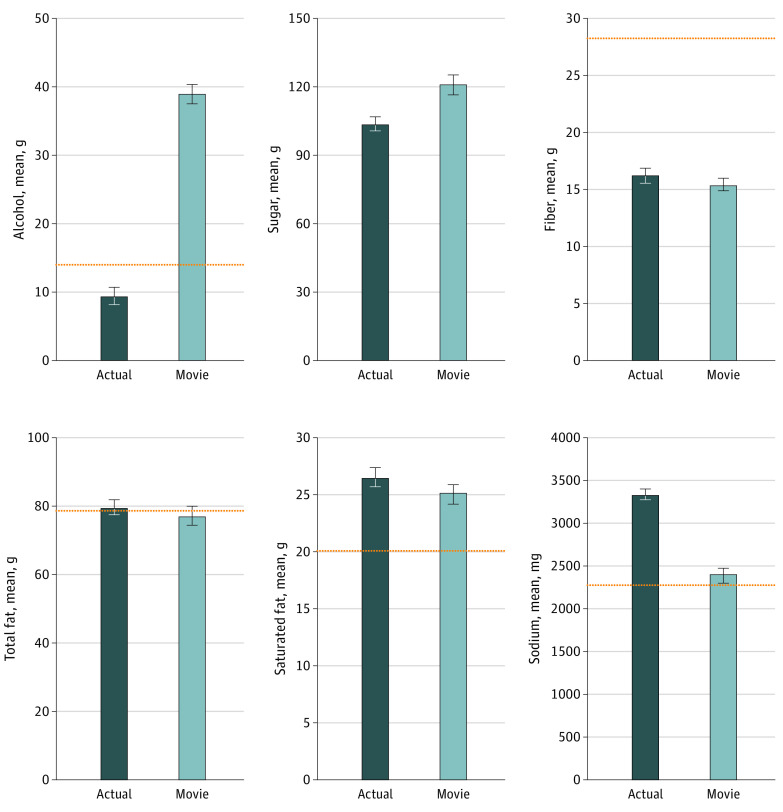

Movies depicted 45.1% less fiber (95% CI, 42.9%-47.0%) than recommended (15.4 g [95% CI, 14.8-16.0 g]). Levels of sodium (2390 mg [95% CI, 2304-2482 mg]), saturated fat (25.0 g [95% CI, 24.1-26.0 g]), and alcohol (38.8 g [95% CI, 37.4-40.3 g]) per 2000 kcal exceeded maximum recommended limits by 3.9% (95% CI, 0.2%-7.9%) for sodium, 25.0% (95% CI, 20.6%-29.9%) for saturated fat, and 177% (95% CI, 167%-188%) for alcohol (eTable 13 in the Supplement). Total fat levels met the maximum recommended limit (76.9 g [95% CI, 74.2-79.9 g]). Although there is no federal recommendation for total sugar intake,33 movies depicted 121 g (95% CI, 116-125 g) of total sugar per 2000 kcal, which is higher than the total sugar content in 3 cans of Coca-Cola.

Comparison With US Individuals’ Actual Dietary Intake

Figure 333,34 and eTable 14 in the Supplement compare US individuals’ actual intake with movie-depicted nutrient levels (both normalized to 2000 kcal). Federal recommended daily levels33 are indicated with a dashed line. Compared with US individuals’ mean nutrient intake per 2000 kcal,34 movies depicted 313% more alcohol (95% CI, 298%-329%) and 16.5% more total sugars (95% CI, 12.3%-21.0%). Levels of fiber, total fat, and saturated fat were similar in movies and in US individuals’ diets, with movies depicting 4.5% less fiber (95% CI, −7.9% to −0.8%), 3.2% less total fat (95% CI, −6.7% to 0.5%), and 5.5% less saturated fat (95% CI, −8.9% to −1.9%). Movies depicted 28.2% less sodium (95% CI, −30.8% to −25.5%) than US individuals’ mean nutrient intake per 2000 kcal.

Figure 3. Movie-Depicted Nutritional Content and US Individuals’ Actual Intake.

Actual represents mean quantities consumed per 2000 kcal of total food and beverage intake for US individuals (all ages) based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2015-2016 data.34 Movie represents model-estimated nutrient quantities per 2000 kcal across all depicted food and beverages. Error bars represent 95% CI of the estimate. The dashed line for alcohol represents 1 alcoholic beverage equivalent. The dashed lines for fiber, total fat, saturated fat, and sodium represent US Food and Drug Administration–recommended daily values.33 There is no daily recommended limit for total sugars.

Further comparisons of the proportions of food and beverage categories that comprised the movie-depicted diet and US individuals’ actual diet23 are presented in Table 2. Alcoholic beverages comprised an 11.4-fold greater share of beverages in movies compared with beverages that US individuals consume (40.1% vs 3.5%), including 16.6-fold more liquor (14.6% vs 0.9%). Although sugar-sweetened beverages comprised a similar proportion of beverages in movies and US consumption (13.7% vs 15.5%), movies depicted 2.4-fold fewer water (15.3% vs 36.3%) and 3.9-fold fewer dairy beverages (3.9% vs 15.3%) than US individuals consume. Among foods, movies depicted 1.8-fold more sweet bakery products (9.3% vs 5.2%), 2.6-fold more candy (7.6% vs 2.9%), and 2.9-fold more fruit (22.3% vs 7.8%) than US individuals consume. Proportions of vegetables (14.4% vs 12.6%), savory snacks (4.1% vs 4.5%), red meats (1.8% vs 2.0%), seafood (1.5% vs 1.1%), and condiments and sauces (5.9% vs 5.9%) were similar in movies and in US consumption. The movie-depicted diet comprised smaller proportions of cured meats (1.4% vs 3.6%), fats and oils (3.5% vs 6.1%), and dairy foods (1.3% vs 4.5%) than US individuals consume.

Table 2. Food and Beverage Categories Depicted in Movies and Consumed by US Individuals.

| Categorya | No. (%) of foods or beverages | |

|---|---|---|

| Moviesb | US dietc | |

| Food category | ||

| Snacks and sweets | 2173 (23.6) | 13 581 (16.8) |

| Sweet bakery products (cookies, pies, pastries, cakes, donuts, brownies) | 851 (9.3) | 4177 (5.2) |

| Candy (candy, chocolate, and caramels) | 702 (7.6) | 2369 (2.9) |

| Savory snacks (cheese balls, pretzels, potato chips, popcorn) | 378 (4.1) | 3626 (4.5) |

| Other desserts (ice cream and frozen dairy desserts, puddings, gelatins) | 156 (1.7) | 1659 (2.0) |

| Crackers | 62 (0.7) | 1311 (1.6) |

| Snack or meal bars (breakfast bar, energy bar, granola bar) | 24 (0.3) | 439 (0.5) |

| Fruits | 2053 (22.3) | 6294 (7.8) |

| Vegetables | 1324 (14.4) | 10 198 (12.6) |

| Vegetables (dark green, starchy, red or orange, mixed-vegetable dishes) | 1124 (12.2) | 7784 (9.6) |

| White potatoes (mashed, baked, fried, boiled, french fries) | 200 (2.2) | 2414 (3.0) |

| Protein | 900 (9.8) | 12 616 (15.6) |

| Plant-based proteins (nuts, seeds, soy products, beans, legumes) | 190 (2.1) | 2366 (2.9) |

| Meats (pork, lamb, beef, goat, game) | 169 (1.8) | 1627 (2.0) |

| Eggs (including omelets) | 153 (1.7) | 1927 (2.4) |

| Seafood (fish, shellfish) | 140 (1.5) | 929 (1.1) |

| Cured meats and poultry (cold cuts, bacon, sausages, hot dogs) | 125 (1.4) | 2894 (3.6) |

| Poultry (chicken, turkey, duck) | 123 (1.3) | 2873 (3.5) |

| Grains | 833 (9.1) | 10 620 (13.1) |

| Breads, rolls, and tortillas (bread loaves, buns, dinner rolls, tortillas, bagels) | 451 (4.9) | 4922 (6.1) |

| Cereals (ready-to-eat) | 150 (1.6) | 2054 (2.5) |

| Quick breads or bread products (biscuits, muffins, pancakes, waffles) | 116 (1.3) | 1337 (1.7) |

| Cooked grains (dry or plain pasta, noodles, rice) | 96 (1.0) | 1637 (2.0) |

| Cooked cereals (oatmeal, breakfast grits) | 20 (0.2) | 670 (0.8) |

| Mixed dishes | 682 (7.4) | 10 612 (13.1) |

| Mixed dishes—sandwiches (cheeseburger, deli subs, hot dogs, peanut butter and jelly sandwich) | 254 (2.8) | 2222 (2.7) |

| Mixed dishes—Asian (chow mein, stir-fry, egg rolls, dumplings, sushi) | 121 (1.3) | 828 (1.0) |

| Mixed dishes—pizza | 91 (1.0) | 1325 (1.6) |

| Mixed dishes—soups | 83 (0.9) | 1225 (1.5) |

| Mixed dishes—grain-based (lasagna, pasta, rice dishes) | 66 (0.7) | 2162 (2.7) |

| Mixed dishes—meat, poultry, seafood | 43 (0.5) | 1449 (1.8) |

| Mixed dishes—Mexican (burritos, tacos, nachos) | 24 (0.3) | 1401 (1.7) |

| Condiments and sauces (ketchup, mustard, soy sauce, dips, gravy) | 539 (5.9) | 4765 (5.9) |

| Fats and oils (butter, cream cheese, whipped cream, mayonnaise, vegetable oils) | 325 (3.5) | 4937 (6.1) |

| Sugars (sugar, honey, sugar substitutes, jams, syrups, toppings) | 251 (2.7) | 3568 (4.4) |

| Dairy | 116 (1.3) | 3654 (4.5) |

| Cheese | 102 (1.1) | 2950 (3.6) |

| Yogurt | 14 (0.2) | 704 (0.9) |

| Other (protein, nutritional powders) | 2 (0.0) | 142 (0.2) |

| Beverage category | ||

| Alcoholic beverages | 2303 (40.1) | 1385 (3.5) |

| Liquor and cocktails | 841 (14.6) | 346 (0.9) |

| Wine | 777 (13.5) | 332 (0.8) |

| Beer | 685 (11.9) | 707 (1.8) |

| Coffee and tea | 1323 (23.0) | 5782 (14.7) |

| Coffee (coffee, cappuccino, blended coffee drinks, mocha) | 1102 (19.2) | 3507 (8.9) |

| Tea (tea, sweet tea) | 221 (3.8) | 2275 (5.8) |

| Water | 881 (15.3) | 14 288 (36.3) |

| Plain water | 849 (14.8) | 14 016 (35.6) |

| Flavored or enhanced water | 32 (0.6) | 272 (0.7) |

| Sweetened beverages | 790 (13.7) | 6112 (15.5) |

| Soft drinks | 579 (10.1) | 3286 (8.4) |

| Fruit drinks | 128 (2.2) | 1919 (4.9) |

| Sport and energy drinks | 61 (1.1) | 492 (1.3) |

| Smoothies and grain drinks | 15 (0.3) | 330 (0.8) |

| Nutritional beverages | 7 (0.1) | 85 (0.2) |

| Dairy beverages | 223 (3.9) | 6026 (15.3) |

| Milk | 179 (3.1) | 4857 (12.3) |

| Milkshakes and other dairy drinks | 20 (0.3) | 130 (0.3) |

| Flavored milk | 19 (0.3) | 733 (1.9) |

| Milk substitutes (almond, soy) | 5 (0.1) | 306 (0.8) |

| 100% Juices | 169 (2.9) | 2434 (6.2) |

| Citrus juice | 114 (2.0) | 1045 (2.7) |

| Other fruit juice | 28 (0.5) | 604 (1.5) |

| Apple juice | 19 (0.3) | 713 (1.8) |

| Vegetable juice | 8 (0.1) | 72 (0.2) |

| Diet beverages | 48 (0.8) | 938 (2.4) |

| Diet soft drinks | 48 (0.8) | 695 (1.8) |

| Diet sport and energy drinks | 0 | 70 (0.2) |

| Other diet drinks | 0 | 173 (0.4) |

| Infant formula and human milk | 11 (0.2) | 2371 (6.0) |

Food and beverage categories are based on What We Eat In America Categories 2015-2016.23

Percentages for movies from 9198 foods and 5748 beverages.

Data on US diet from nationally representative National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2015-2016 survey, day 1 intake, all respondents (8506 individuals, 80 987 foods, and 39 336 beverages).

Discussion

Exposure to movie portrayals of problematic societal behaviors including racial bias,38 violence,39 risky sex,40 binge drinking,18,19 and smoking16,17 is associated with increases in those behaviors among viewers. To the extent that food and beverage depiction in movies is also associated with viewers’ food and beverage consumption, as reported by short-term laboratory studies for food depictions20,21 and longitudinal cohort studies for alcohol depictions,18,19 our nutritional analyses suggest that US movies promote unhealthy consumption to global audiences. Together, these data show that 72.7% of the most influential US movies from 1994 to 2018 would be unhealthy enough to fail legal nutrition advertising standards in the United Kingdom for foods, as would 90.2% of movies for beverages. There was no improvement in nutrition scores over time or for younger audiences. Furthermore, the movie-depicted diet failed nutrition recommendations and was similar to or less healthy than the US diet in sugar, saturated fat, total fat, fiber, water, and, especially, alcohol content.

One potential explanation for these results is frequent product placement of branded unhealthy items, a means of covert advertising in movies.10,11,25 However, although branded items were less healthy than nonbranded items, just 11.5% of foods and beverages were visibly branded. This finding suggests that the problem of media depictions of unhealthy diets as normative and valued extends far beyond brands and advertisements. Accordingly, an understanding of obesogenic food environments must expand beyond advertising, food supply systems, and physical built environments41,42 to also include sociocultural media influences.

Movies may represent an opportunity to encourage healthier consumption if movie producers depict healthier foods and beverages. Historically, however, industry self-regulation has been an unsuccessful approach for reducing unhealthy substance depiction.25,43,44 For example, alcohol depiction in movies has been self-regulated, and as prior research10,25 and the present findings show, alcohol depictions remain common, even in movies targeting youths. For smoking, the Master Settlement Agreement of 1998, an external regulation to end placement of cigarette brands in movies, decreased overall smoking depiction.25 However, without universal endorsement of the R rating for movies with any tobacco imagery, smoking persists in movies accessible to youths.25,44 Although the present research represents an important step in illuminating the nutritional composition of foods and beverages depicted in movies, additional research is needed to understand the long-term effects of exposure on viewers’ consumption and to inform targeted advocacy efforts for improving the nutritional profile of foods and beverages that movies depict.

Limitations

This research has several limitations. First, the foods and beverages depicted in the 10 top-grossing movies from each year may not be representative of all movies released that year. This sample contained a disproportionate amount of action, adventure, and PG-13–rated movies. Second, nutritional values from the FNDDS may be imprecise in difficult cases, such as foods and beverages in animated movies. However, the FNDDS provides entries for general forms of food (eg, cake, not further specified) when nutrition content is not completely knowable. Third, depictions of foods and beverage were coded as discrete instances rather than coding the amount of time depicted, portion sizes, or how characters interacted with foods, which are potentially influential factors for viewers’ behavior.21

Conclusions

Advertisements for nutrient-poor foods and beverages have been extensively studied and are now regulated in many countries outside of the United States. The present results suggest that most top-grossing US movies depict a diet that would be unhealthy enough to fail legal advertising limits to youths in the United Kingdom, as well as US federal recommendations for a healthy diet. The results suggest that the marketing and social acceptance of unhealthy foods is a sociocultural problem that extends beyond advertisements and branded product placements. Given their influence, however, movies represent a high-impact opportunity to promote healthy consumption if movie producers expand the range of foods and beverages depicted as normative, valued, and representative of US culture.

eMethods.

eResults.

eTable 1. Movie Characteristics

eTable 2. Detailed Coding Decisions

eTable 3. Food Categories Depicted in Movies

eTable 4. Beverage Categories Depicted in Movies

eTable 5. Movie-level and Item-level Nutrition Ratings for Foods and Beverages in Movies

eTable 6. Branded Food Categories Depicted in Movies

eTable 7. Branded Food Items Depicted in Movies

eTable 8. Branded Beverage Categories Depicted in Movies

eTable 9. Branded Beverage Items Depicted in Movies

eTable 10. Branded Restaurant Storefronts Depicted in Movies

eTable 11. Trends in Nutrition Ratings and Key Nutrients Over Time

eTable 12. Trends in Nutrition Ratings and Key Nutrients by MPAA Rating

eTable 13. Comparing Movie-Depicted Nutrients With Federal Recommended Daily Values

eTable 14. Comparing Movie-Depicted Nutrients With US Individuals’ Actual Intake

eFigure 1. Example Nutrient Profile Index (NPI) Scores for Foods

eFigure 2. Example Nutrient Profile Index (NPI) Scores for Beverages

eFigure 3. Example Front-of-Package “Traffic Light” Ratings for Nutrient Content of Foods

eFigure 4. Movie-Level Traffic Light Nutrition Ratings for Foods

eFigure 5. Trends in NPI Nutrition Scores Over Time and by MPAA Rating

eReferences.

References

- 1.Boyland EJ, Nolan S, Kelly B, et al. Advertising as a cue to consume: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of acute exposure to unhealthy food and nonalcoholic beverage advertising on intake in children and adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(2):519-533. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.120022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lapierre MA, Fleming-Milici F, Rozendaal E, McAlister AR, Castonguay J. The effect of advertising on children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140(suppl 2):S152-S156. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1758V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith R, Kelly B, Yeatman H, Boyland E. Food marketing influences children’s attitudes, preferences and consumption: a systematic critical review. Nutrients. 2019;11(4):e875. doi: 10.3390/nu11040875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Public Health England The 2018 review of the UK Nutrient Profiling Model. Accessed January 24, 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/694145/Annex__A_the_2018_review_of_the_UK_nutrient_profiling_model.pdf

- 5.Taillie LS, Busey E, Mediano Stoltze F, Dillman Carpentier FR. Governmental policies to reduce unhealthy food marketing to children. Nutr Rev. 2019;77(11):787-816. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuz021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman B, Kelly B, Baur L, et al. Digital junk: food and beverage marketing on Facebook. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):e56-e64. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bragg MA, Miller AN, Elizee J, Dighe S, Elbel BD. Popular music celebrity endorsements in food and nonalcoholic beverage marketing. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20153977. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bragg MA, Miller AN, Roberto CA, et al. Sports sponsorships of food and nonalcoholic beverages. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20172822. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bragg MA, Pageot YK, Amico A, et al. Fast food, beverage, and snack brands on social media in the United States: an examination of marketing techniques utilized in 2000 brand posts. Pediatr Obes. 2020;15(5):e12606. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dal Cin S, Worth KA, Dalton MA, Sargent JD. Youth exposure to alcohol use and brand appearances in popular contemporary movies. Addiction. 2008;103(12):1925-1932. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02304.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sutherland LA, Mackenzie T, Purvis LA, Dalton M. Prevalence of food and beverage brands in movies: 1996-2005. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):468-474. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matthes J, Naderer B. Sugary, fatty, and prominent: food and beverage appearances in children’s movies from 1991 to 2015. Pediatr Obes. 2019;14(4):e12488. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shweder RA. Why Do Men Barbecue? Recipes for Cultural Psychology. Harvard University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markus HR, Kitayama S. Cultures and selves: a cycle of mutual constitution. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2010;5(4):420-430. doi: 10.1177/1745691610375557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markus HR, Conner A. Clash!: How to Thrive in a Multicultural World. Hudson Street Press; 2014:14-36. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dalton MA, Sargent JD, Beach ML, et al. Effect of viewing smoking in movies on adolescent smoking initiation: a cohort study. Lancet. 2003;362(9380):281-285. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13970-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD. Exposure to smoking in internationally distributed American movies and youth smoking in Germany: a cross-cultural cohort study. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):e108-e117. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD. Longitudinal study of exposure to entertainment media and alcohol use among German adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):989-995. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD, Hunt K, et al. Portrayal of alcohol consumption in movies and drinking initiation in low-risk adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):973-982. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown CL, Matherne CE, Bulik CM, et al. Influence of product placement in children’s movies on children’s snack choices. Appetite. 2017;114:118-124. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthes J, Naderer B. Children's consumption behavior in response to food product placements in movies. J Cons Behav. 2015;14(2):127-136. doi: 10.1002/cb.1507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The internet Movie Database. Top box office (US). Accessed February 4, 2020. https://www.imdb.com/boxoffice/alltimegross

- 23.US Department of Agriculture What We Eat in America Food Categories 2015-2016. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/1516/Food_categories_2015-2016.pdf

- 24.US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service Food Surveys Research Group: Beltsville, MD. Accessed September 14, 2020. https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/fndds/

- 25.Bergamini E, Demidenko E, Sargent JD. Trends in tobacco and alcohol brand placements in popular US movies, 1996 through 2009. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(7):634-639. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159-174. doi: 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lobstein T, Davies S. Defining and labelling “healthy” and “unhealthy” food. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(3):331-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris JL, Schwartz MB, Munsell CR, et al. Fast Food FACTS 2013: Measuring Progress in Nutrition and Marketing to Children and Teens. Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity; 2013. Accessed July 21, 2020. https://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2013/rwjf408549

- 29.Department of Health Guide to creating a front of pack (FoP) nutrition label for pre-packed products sold through retail outlets. Accessed January 24, 2020. https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/fop-guidance_0.pdf

- 30.Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB, et al. Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J Nutr. 2012;142(6):1009-1018. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.157222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. ; American Heart Association Strategic Planning Task Force and Statistics Committee . Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic impact goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586-613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rehm CD, Peñalvo JL, Afshin A, Mozaffarian D. Dietary intake among US adults, 1999-2012. JAMA. 2016;315(23):2542-2553. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.US Food and Drug Administration. Food labeling: revision of the nutrition and supplement facts label: guidance for industry. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/134505/download

- 34.US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service Nutrient intakes from food and beverages: mean amounts consumed per individual, by gender and age, in the United States, 2015-2016. Accessed February 11, 2020. https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/1516/Table_1_NIN_GEN_15.pdf

- 35.United States Department of Agriculture Scientific report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: advisory report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture. Accessed July 27, 2020. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Scientific-Report-of-the-2015-Dietary-Guidelines-Advisory-Committee.pdf

- 36.Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J Stat Softw. 2017;82(13):1-26. doi: 10.18637/jss.v082.i13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.R CoreTeam R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2013. Accessed July 21, 2020. https://www.r-project.org/

- 38.Weisbuch M, Pauker K, Ambady N. The subtle transmission of race bias via televised nonverbal behavior. Science. 2009;326(5960):1711-1714. doi: 10.1126/science.1178358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huesmann LR, Taylor LD. The role of media violence in violent behavior. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:393-415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Hara RE, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Li Z, Sargent JD. Greater exposure to sexual content in popular movies predicts earlier sexual debut and increased sexual risk taking. Psychol Sci. 2012;23(9):984-993. doi: 10.1177/0956797611435529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):804-814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Townshend T, Lake A. Obesogenic environments: current evidence of the built and food environments. Perspect Public Health. 2017;137(1):38-44. doi: 10.1177/1757913916679860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sargent JD, Tickle JJ, Beach ML, Dalton MA, Ahrens MB, Heatherton TF. Brand appearances in contemporary cinema films and contribution to global marketing of cigarettes. Lancet. 2001;357(9249):29-32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03568-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Polansky JR, Driscoll D, Garcia C, Glantz SA Smoking in top-grossing US movies 2018. UCSF Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education. Accessed July 21, 2020. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/55x9b9c1

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.

eResults.

eTable 1. Movie Characteristics

eTable 2. Detailed Coding Decisions

eTable 3. Food Categories Depicted in Movies

eTable 4. Beverage Categories Depicted in Movies

eTable 5. Movie-level and Item-level Nutrition Ratings for Foods and Beverages in Movies

eTable 6. Branded Food Categories Depicted in Movies

eTable 7. Branded Food Items Depicted in Movies

eTable 8. Branded Beverage Categories Depicted in Movies

eTable 9. Branded Beverage Items Depicted in Movies

eTable 10. Branded Restaurant Storefronts Depicted in Movies

eTable 11. Trends in Nutrition Ratings and Key Nutrients Over Time

eTable 12. Trends in Nutrition Ratings and Key Nutrients by MPAA Rating

eTable 13. Comparing Movie-Depicted Nutrients With Federal Recommended Daily Values

eTable 14. Comparing Movie-Depicted Nutrients With US Individuals’ Actual Intake

eFigure 1. Example Nutrient Profile Index (NPI) Scores for Foods

eFigure 2. Example Nutrient Profile Index (NPI) Scores for Beverages

eFigure 3. Example Front-of-Package “Traffic Light” Ratings for Nutrient Content of Foods

eFigure 4. Movie-Level Traffic Light Nutrition Ratings for Foods

eFigure 5. Trends in NPI Nutrition Scores Over Time and by MPAA Rating

eReferences.