Abstract

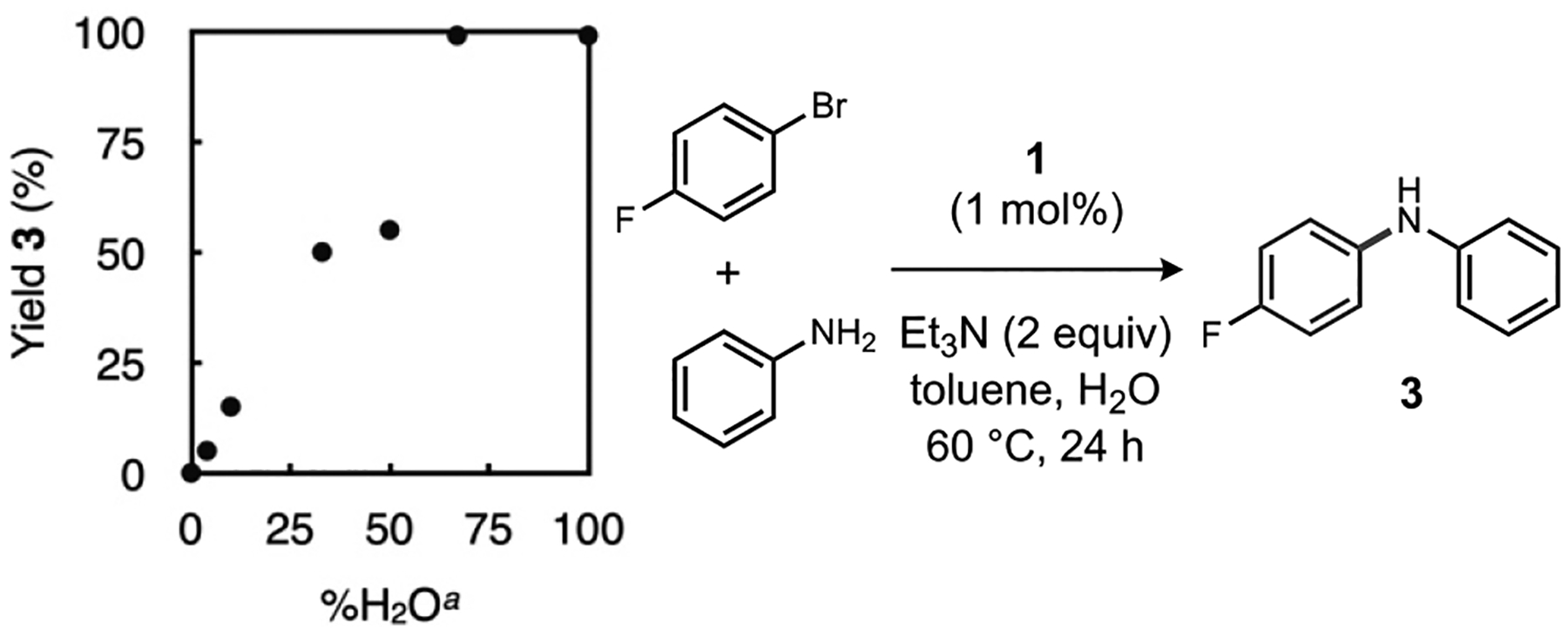

Amination of aryl halides has become one of the most commonly practiced C–N bond-forming reactions in pharmaceutical and laboratory synthesis. The widespread use of strong or poorly soluble inorganic bases for amine activation nevertheless complicates the compatibility of this important reaction class with sensitive substrates as well as applications in flow and automated synthesis, to name a few. We report a palladium-catalyzed C–N coupling using Et3N as a weak, soluble base, which allows a broad substrate scope that includes bromo- and chloro(hetero)arenes, primary anilines, secondary amines, and amide type nucleophiles together with tolerance for a range of base-sensitive functional groups. Mechanistic data have established a unique pathway for these reactions in which water serves multiple beneficial roles. In particular, ionization of a neutral catalytic intermediate via halide displacement by H2O generates, after proton loss, a coordinatively-unsaturated Pd–OH species that can bind amine substrate triggering intramolecular N–H heterolysis. This water-assisted pathway operates efficiently with even weak terminal bases, such as Et3N. The use of a simple, commercially available ligand, PAd3, is key to this water-assisted mechanism by promoting coordinative unsaturation in catalytic intermediates responsible for the heterolytic activation of strong element-hydrogen bonds, which enables broad compatibility of carbon-heteroatom cross-coupling reactions with sensitive substrates and functionality.

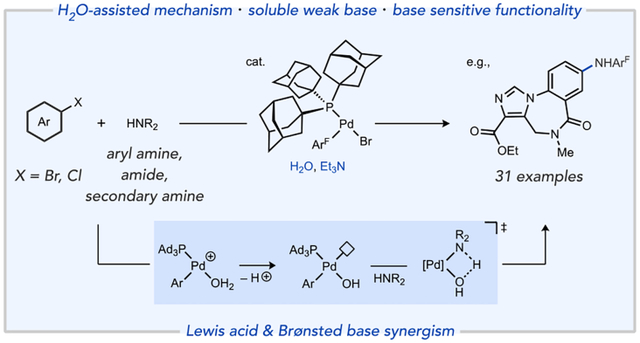

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Carbon-nitrogen cross-coupling reactions using palladium and related late transition metal catalysts are some of the most widely utilized methods for the synthesis of pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, organic electronic materials, and fine chemicals.1 Over that past two decades, numerous innovations in the ligand(s) and precatalyst structure of palladium complexes have been made that have expanded the diversity of organic electrophile and amine nucleophile classes applicable to this transformation.2 On the other hand, the bases used for Buchwald-Hartwig amination have evolved to a lesser extent; modern C–N coupling methods still rely heavily on ionic bases, such as sodium tert-butoxide or lithium hexamethyldisilazide (LiHMDS).3 Such strong ionic bases impose compatibility issues with functional groups susceptible to nucleophilic attack, such as carboxylic acids, esters, nitriles, nitro groups, and carbonyl groups with enolizable sites, to name a few.4 Amination reactions conducted on scale in organic solvents using common inorganic bases, such as hydroxide, carbonate and phosphate salts, also frequently incur reproducibility issues.5 High-throughput experimentation (HTE)6 and continuous flow chemistry7 face similar issues where base insolubility can present either an inconvenience or major hurdle, respectively.8 The development of new methods that operate efficiently with weak, soluble, and inexpensive bases could circumvent all of these issues and broaden the applicability of C–N coupling in industrial applications.

The difficulty of transitioning C–N coupling toward the use of weak, soluble bases can be attributed, at least in part, to a mechanistic challenge using conventional Pd catalysts, such as those ligated by BINAP as a prototypical example. A combined computational and experimental mechanistic study by Norrby found that soluble neutral bases such as the phosphazene tert-butylimino-tri(pyrrolidino)phosphorene (t-BuP1(pyrr)), Barton’s guanidine base 2-tert-butyl-1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine (BTMG), or the amidines 7-methyl-1,5,7-triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene (MTBD) and 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) perform poorly relative to NaOtBu as a prototypical strong ionic base (Scheme 1a).9 This striking difference was correlated to the preference of the system to maintain neutral reaction pathways in nonpolar organic solvents because ionization of neutral metal halide complexes is too energetically unfavorable. Ionic bases are more reactive in the neutral manifold, either by deprotonating a neutral amine-coordinated Pd intermediate or through salt metathesis to generate a basic Pd-alkoxo intermediate that can deprotonate an amine substrate.10 Furthermore, amine bases such as DBU were implicated in catalyst inhibition by competitively binding Pd to form off-cycle intermediates.11

Scheme 1.

Base effects in Pd-catalyzed C–N coupling.

Several studies have recently demonstrated that newer generation Pd complexes featuring hindered phosphines can catalyze C–N coupling reactions with soluble bases. The phosphazene superbase P2Et enabled homogeneous aminations suitable for HTE screening on micro- or nanomole scale.12 However, phosphazene bases are prohibitively expensive for large scale applications. Buchwald developed a well-defined Pd precatalyst coordinated by the hindered terphenyl phosphine AlPhos, which catalyzes amination reactions of aryl triflates or some halides with unhindered primary amines and amides using DBU as base.13 Palladium catalysts featuring other phosphine ligands, such as Xantphos, DPEphos, and Josiphos have also emerged for DBU-promoted C–N coupling.14,5 Additionally, photoredox15 or electrochemical16 conditions have been demonstrated to provide sufficient driving force to utilize weak bases, such as DABCO.

Importantly in the (AlPhos)Pd-catalyzed reactions, a ligand-enabled mechanism change from a typical neutral to an ionic pathway for N–H cleavage was identified, which facilitates efficient turnover with a weak base (Scheme 1b).11a Dissociation of a triflate anion and coordination of amine leads to acidification of the bound substrate to such an extent that the cationic intermediate is susceptible to external N–H deprotonation by even moderate bases, like DBU. Furthermore, the turnover-limiting step of these reactions was found to be dissociation of DBU from an off-cycle intermediate coordinated by this base, which highlights another challenge facing weak base amination reactions involving Lewis basic (strongly coordinating) reagents. Extending the applicable weak base further to tertiary amines remains highly desirable in this area due to their low cost, tunable properties, stability,17 and low basicity in comparison to other soluble bases such as amidines, guanidines, or phosphazenes. To this end, a Ni-catalyzed amination of aryl triflates with anilines and triethylamine as base was recently reported by Buchwald.18 An ionic catalytic pathway is also believed to operate in this system for which aryl bromides and chlorides are more challenging substrates, possibly due to stronger halide coordination to the transition metal that inhibits ionization and amine binding. An outstanding need thus remains for the identification of new catalysts that can promote weak base coupling with widely available halo(hetero)arene electrophiles, as opposed to specialty aryl triflates, with a variety of amine nucleophile classes using an “ideal” soluble weak base, such as Et3N.19

Our group previously reported a coordinatively-unsaturated organopalladium catalyst, Pd(PAd3)(ArF)Br 1 (ArF = 4-FC6H4), which functions as an on-cycle catalyst for Suzuki-Miyaura coupling with organoboronic acids prone to fast base-catalyzed protodeboronation (PDB).20 A key aspect of this development was achieving efficient catalytic turnover using the combination of H2O and a weak, soluble amine base (Et3N). Stoichiometric mechanistic experiments implicated ionization of Pd(PAd3)(ArF)X (X = Br, Cl) complexes to cationic species [Pd(PAd3)(ArF)(S)]+ (S = water, solvent),21 which undergo facile deprotonation of the acidified aqua ligand even by mild bases (Scheme 1c).22 It is thus possible to access coordinatively unsaturated Pd-hydoxo intermediates (III, Scheme 1c) that feature both Lewis acidic (open coordination site) and Lewis/Brønsted basic properties in the absence of stoichiometric ionic bases (i.e., hydroxide or alkoxides).23 Because palladium hydroxo and alkoxo complexes have been implicated in numerous other catalytic processes but are classically accessed by reactions involving stoichiometric strong bases (e.g., NaOH, NaOtBu),24 it may be possible to leverage the water-assisted pathway we uncovered to promote a range of catalytic transformations under conditions milder than what was possible using traditional catalysts.

The Brønsted basicity of species such as III should also be reactive toward activation of strong element-hydrogen bonds, such as in the amine activation step (N–H heterolysis) of Buchwald-Hartwig amination.25 While such species can be generated from stoichiometric reactions of Pd(II)-halide complexes with hydroxide,26 the intermediacy of palladium hydroxo complexes in N–H bond activation has to our knowledge not been unambiguously established in a catalytic setting.27 We hypothesized that the coordination of amine to the catalyst open site should strongly acidify the N–H bond, and the cis-hydroxo ligand would then be poised for intramolecular deprotonation to extrude water and generate the penultimate Pd-amido catalytic intermediate. Here we report a method for aryl amination of bromo- and chloro(hetero)arenes using the on-cycle catalyst 1 and Et3N as a soluble weak base. Water is an essential component for these reactions, and mechanistic data implicate three complementary roles by which water can facilitate the overall catalytic process: i) acceleration of an inner sphere heterolysis of the substrate N–H bond, ii) driving an unfavorable ionization of neutral palladium halide species by sequestering halide into an aqueous phase, and iii) shunting catalyst away from an inhibited, base-coordinated state.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

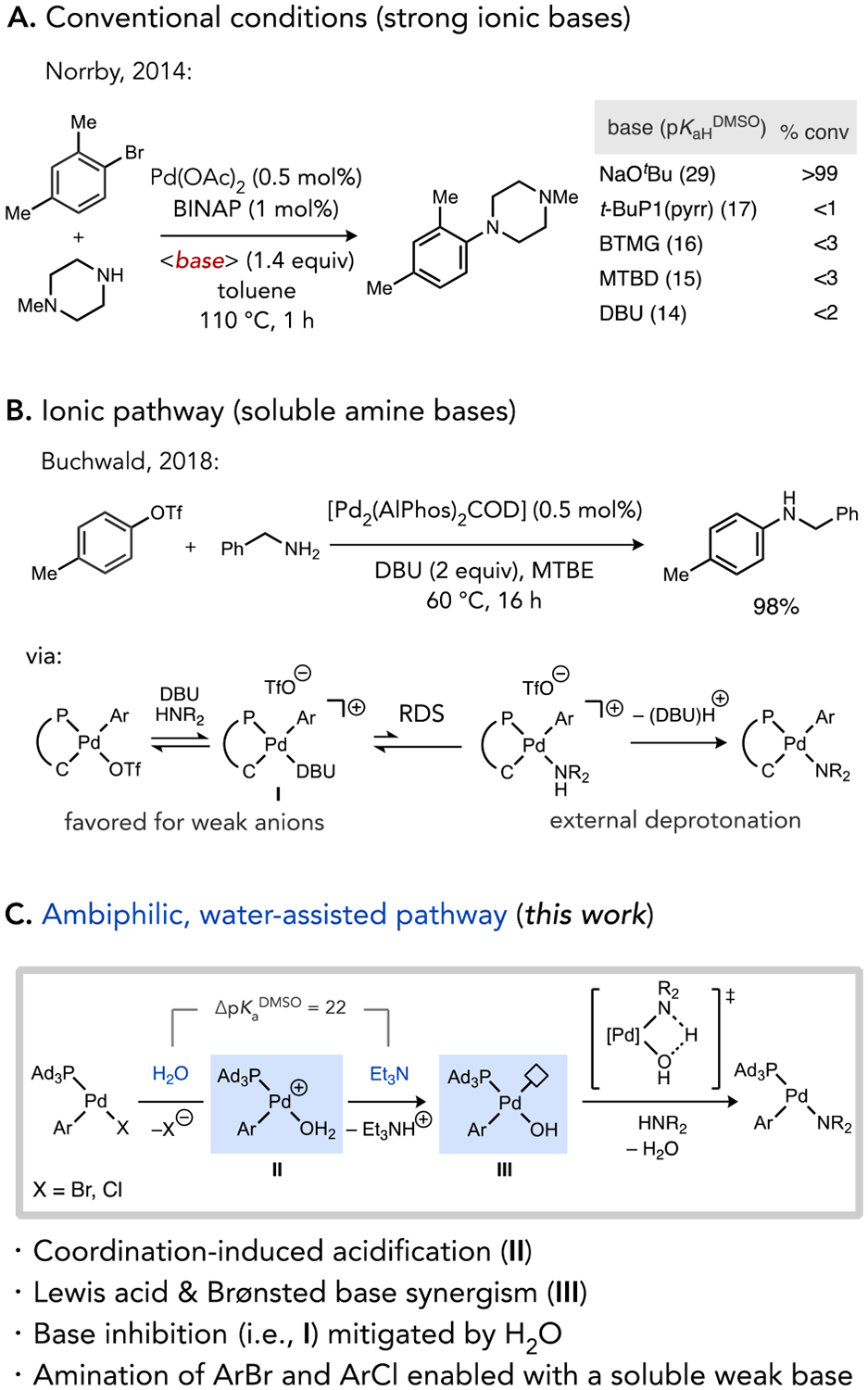

High-throughput experimentation (HTE) techniques were used to assess the multi-dimensional influence of solvent, amine base, and water on a model reaction between 4-chlorobiphenyl and 4-nitroaniline catalyzed by complex 1 (1 mol%) to form amine 2.28 Representative results of this three-dimensional screening are visualized in the heat plot shown in Figure 1 (see Tables S1 and S2 for tabular data). The solvent dimension did not indicate a clear contrast in conversion as a function of solvent polarity. Both polar (a)protic (e.g., t-amyl alcohol, DMF) and relatively non-polar (e.g., toluene, DME, 2-methyl tetrahydrofuran) solvents were associated with significant conversion. On the other hand, Et3N (pKaHDMSO = 9) gave the best average conversion versus other tertiary amines (e.g., diisopropylethylamine, N-methyl morpholine) in the base dimension. Counterintuitively, stronger bases (pKaDMSO) such as MTBD (15), DBU (14), or tetramethylguanidine (13) were generally inferior to Et3N, which contrasts the base trends typically observed in C–N coupling, even compared to a recently-developed weak base method using AlPhos-coordinated Pd catalysts.11a Importantly, reactions conducted with more water performed better regardless of the choice of base.

Figure 1.

Heat plot for survey of soluble amine bases under Buchwald-Hartwig amination conditions with water co-solvent. ArF = 4-FC6H4. aVersus total solvent volume.

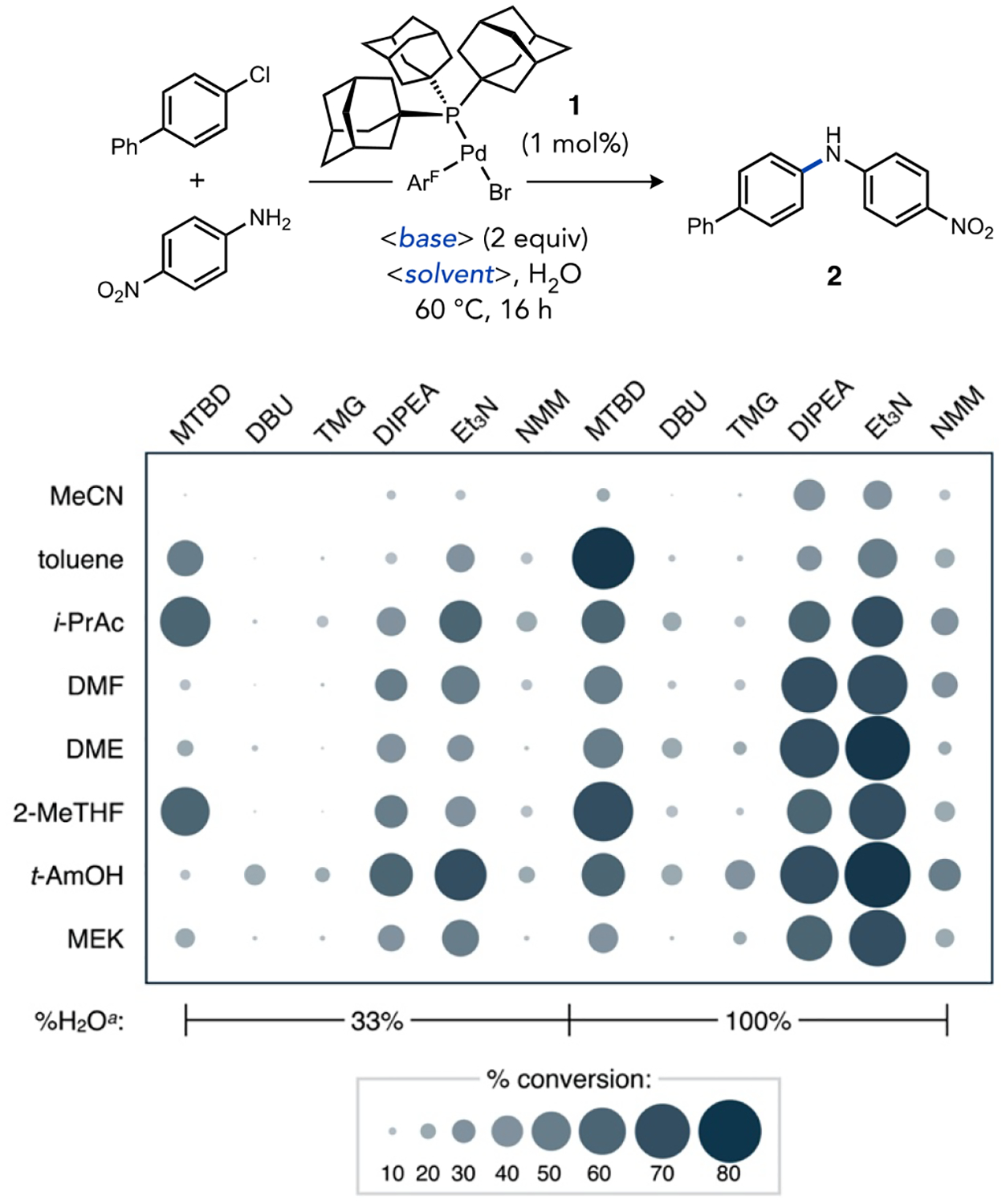

Additional optimization confirmed water loading as a crucial dimension for achieving high reaction conversions (Figure 2), as determined by formation of 3 by 19F NMR spectroscopy during reactions of 1-bromo-4-fluorobenzene with aniline. Together with an increase in reaction temperature from 60 to 80 °C, adjusting the solvent/water ratio to at least 2:3 gave markedly improved yields after 6 h. It is worth noting we believe the better performance of toluene in this model reaction versus the HTE screen may reflect a solubility artifact during catalyst dosing (compare Tables S1 and S2). In subsequent methodology studies (Tables S3–S5), a 1:4 mixture of toluene and water was ultimately selected as the most versatile mixture across different haloarene and amine combinations. We also found that substitution of 1 for the admixture of PAd3 with a commercially available (Buchwald-G3) precatalyst gave comparable performance in formation of 2 from 4-chlorobiphenyl (see Tables 1 and S6).

Figure 2.

Optimization of water assistance during weak base Buchwald-Hartwig amination. Yield determined by 19F NMR versus CF3C6H5 as internal standard. aVersus total toluene volume.

Table 1.

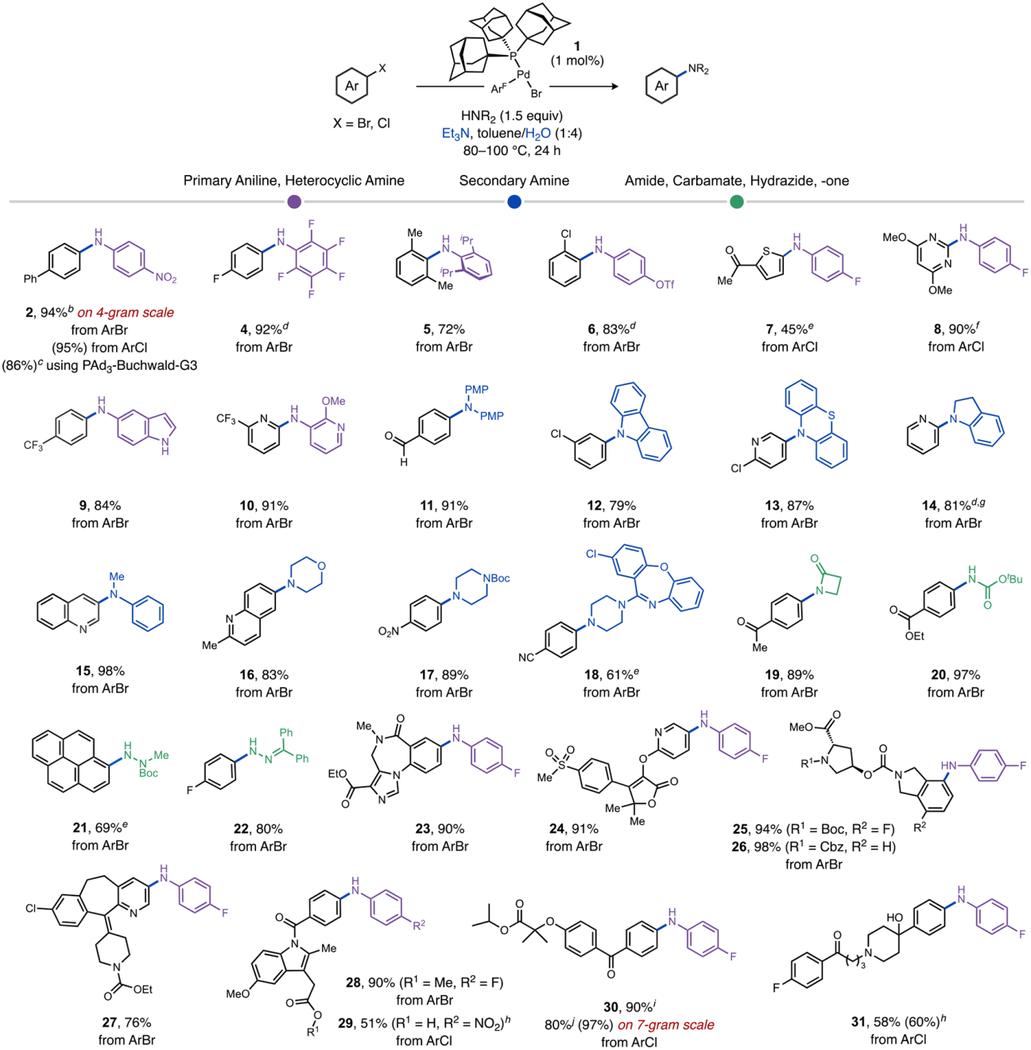

Substrate Scope of Water-Assisted Amination Using Triethylamine as a Soluble Weak Base.a

|

Standard conditions: Aryl halide (0.2 M), amine (1.5 equiv), Et3N (2 equiv), and catalyst 1 (1 mol%) were stirred in a toluene/H2O (1:4) mixture at 80 °C (X = Br) or 100 °C (X = Cl) in a sealed vial over 24 h. Isolated yields shown unless noted otherwise; parentheses denote yields determined by 19F NMR vs. CF3C6H5 as internal standard or calibrated UPLC analysis.

6 h.

Catalyst generated in situ, see Table S6 for details.

Neat water.

48 h.

16 h.

3 mol% 1.

2 mol% 1, 48 h.

36 h.

t-AmOH/H2O (1:3), 85 °C for 12 h. ArF = 4-FC6H4. PMP = 4-MeOC6H4.

A variety of chloro- and bromo(hetero)arene electrophiles and nucleophiles were tested to explore the scope of a method featuring this (Ad3P)Pd-catalyzed, water-assisted reaction pathway (Table 1). For primary aryl amines, products generated from an electron-poor nucleophile (4), which are more challenging versus simple amines,15,29 and hindered aniline (5) occurred in 92% and 72% isolated yield, respectively, suggesting good tolerance to variations in aniline electronic and steric properties. Preliminary screening suggested primary alkyl amines (see Table S7) are challenging for this catalyst, as has been noted before using catalysts with a single monophosphine ligand.3g,30 Chemoselective oxidative addition favoring bromide over triflate or chloride is confirmed by formation of 6, 12, 13, 18, and 27 in 61–87% isolated yields. An internal competition reaction with 4-BrC6H4OTf (not shown) was also highly selective for C–Br activation giving S1 in 90% isolated yield (see Supporting Information). This orthogonality makes bond constructions at different C–X bonds viable and also complements previous C–N coupling methods favoring activation of aryl triflates. Heteroaryl chlorides, such as those containing thiophene (7) and pyrimidine (8) motifs, were compatible substrates under the reaction conditions. Reactions using heterocyclic amines such as 5-aminoindole (9) and 3-amino-2-methoxypyridine (10) underwent arylation in high yield (84% and 91%, respectively).

Secondary anilines that underwent arylation in good to excellent yields (79–98%) include carbazole (12), phenothiazine (13), indoline (14), and N-methylaniline (15). Aliphatic secondary amines are also competent nucleophiles to generate 16–18 in 61–89% isolated yields, the latter of which involved the drug amoxapine as the nucleophile. As a point of comparison, secondary amines were shown to be poor substrates in previous C–N coupling strategies with organic base, presumably due to steric clash with the extremely hindered ligands used.14,18 The amide nucleophile 2-azetidinone or the protected ammonia equivalent t-butyl carbamate generated 19 and 20 in 89% and 97% yields, respectively. Hydrazine derivatives that are useful functional handles for heterocycle synthesis,1a such as 1-Boc-1-methylhydrazide or benzophenone hydrazone, were also suitable nucleophiles for this method generating 21 and 22 in 69% and 80% isolated yields, respectively. These results highlight versatility of this water-assisted method across a spectrum of nucleophile classes that sample a broad range of N–H pKa and size. A survey of several alternative catalysts established for C–N coupling across a panel of three substrate combinations (Figure S2) indicates 1 gives superior performance.

Drug-like electrophiles were also explored to gauge the tolerance of the catalyst and water-assisted method to more complex functionality. Reaction of 4-fluoroaniline with compounds X2, X3, X4, X6, or X8 generated amination products 23–27 in 76–98% isolated yields.31 The high yields in these reactions indicate the synthetic utility of a weak base strategy compared against established catalytic or stoichiometric C–N coupling of these substrates using strong bases.12d,32

Importantly, we envisioned this weak base method should engender improved compatibility toward base-sensitive functionality. Ketone and ester functional groups with enolizable sites were well-tolerated, as exemplified by the moderate to good yields obtained for formation of products 7 (45%), 19 (89%), 25 (94%), 26 (98%), 28 (90%), and 31 (58%). Formation of 17 and 18 in 89% and 61% yield, respectively, demonstrate tolerance of nitrile and nitro groups. Functionalization of the commercial drugs indomethacin, fenofibrate, and haloperidol in 51%, 90%, and 58% isolated yields, respectively, further highlight both the compatibility of this weak base amination method with chloroarenes as well as with protic functional groups (e.g., carboxylic acid in 29 and alcohol in 31). Several amination reactions were also conducted in neat water (e.g., 4, 6, and 14), which demonstrate that catalyst 1 can operate under single solvent conditions that could be advantageous for green chemistry33,34 or biorthogonal35 applications and might hint that the beneficial role(s) of water may extend beyond just sequestration of halide away from an organic solvent phase where catalyst resides.36

Amination of the chloroarene fenofibrate was selected to evaluate the scalability of the method. Preliminary reactions (Table S9) on half-gram scale at 98 °C indicated comparably high conversions for reactions in toluene, anisole, cyclopropyl methyl ether, or t-amyl alcohol as solvent. At a lower temperature (80 °C), t-AmOH was superior giving 94% conversion within 21 h. Further increasing the reaction in t-AmOH to 20-mmol scale gave an excellent solution yield (97%) of 30 within 12 h at 85 °C yielding 7.0 g (80%) of analytically pure (>99%) product after crystallization. Kinetic profiling of the reaction (Figure S4) indicated 100% conversion was actually achieved within 45 min at 1 mol% catalyst loading.

The effectiveness of the combination of a (Ad3P)Pd catalyst and water in enabling catalytic turnover of bromo- and chloroarenes raised several mechanistic questions. For instance, it was not clear a priori if a similar or distinct catalytic mechanism might be operative compared to what has been proposed using an (AlPhos)Pd catalyst and DBU under anhydrous conditions (Scheme 1b).11a,13 A switch in mechanism could potentially account for the improved reactivity toward bromo- and chloroarene electrophiles in this method versus aryl triflates as well as the lack of base inhibition observed previously. Experiments were thus conducted to interrogate the role(s) water plays in the catalytic mechanism, such as the initially hypothesized potential for on-cycle Pd intermediates to be generated from coordinated water.

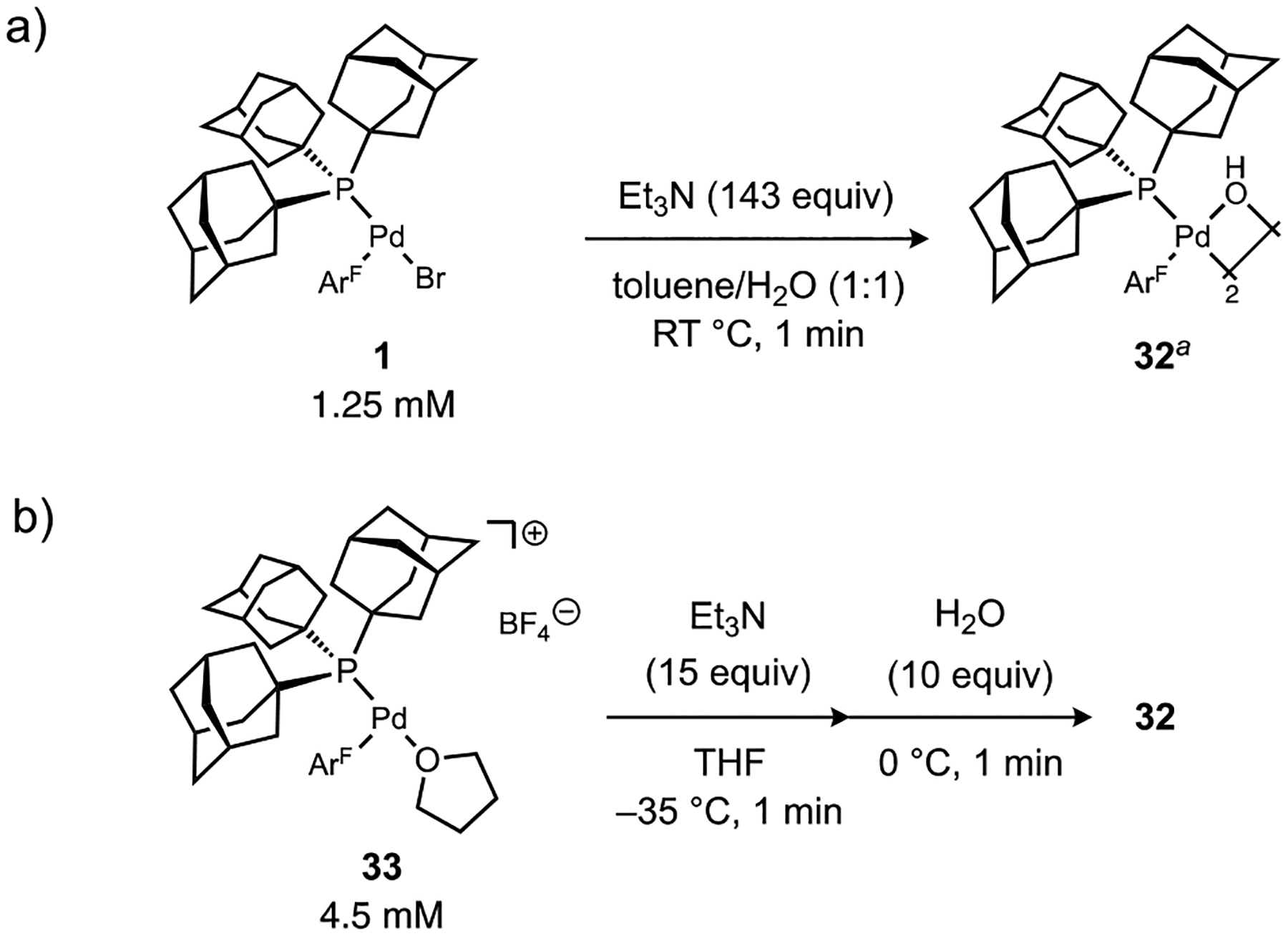

Observation of the reaction of neutral complex 1 with water and Et3N in toluene by 31P NMR spectroscopy indicated clean formation of a new palladium complex after 1 min (Figure 3a). Based on comparison to an independently prepared sample, this new species was assigned as the μ-hydroxo complex 32. A dimeric solution structure for 32 is suggested by the observation in the 1H NMR spectrum of a single upfield resonance virtually coupled to phosphorus (δH = −2.12 ppm, J(31P–1H) = 3.2 Hz) corresponding to a μ-OH ligand and an anti disposition of PAd3 ligands. Importantly, the time frame for this stoichiometric reaction is far less than that required for the respective catalytic aminations in Table 1 even at a much lower temperature, which suggests formation of Pd hydroxo species from water and Et3N is a kinetically viable step during catalysis. On the other hand, addition of water or Et3N individually to 1 led to no detectable changes in the 31P NMR spectra.

Figure 3.

Stoichiometric O–H heterolysis reactions initiated from (a) neutral or (b) cationic aryl-palladium complexes using water and Et3N. aNo conversion was observed in the absence of added H2O or Et3N. ArF = 4-FC6H4.

Deprotonation of a strongly acidified aqua ligand by Et3N in a cationic Pd species would be expected to be facile, and presumably renders the preceding fast yet unfavorable equilibrium hydrolysis step irreversible. An analogous cationic pathway for B-to-Pd transmetalation was postulated in our previous study of weak base Suzuki-Miyaura coupling.21 To further probe if such a process could be operative in the present amination reactions, a discrete cationic species [Pd(PAd3)(ArF)(THF)]+ BF4– (33) was prepared at low temperature according to a reported procedure.21 Treatment of 33 with Et3N at −35 °C in THF for 1 min generated a new species (vide infra) that cleanly converted to Pd hydroxo complex 32 within 1 min at 0 °C upon addition of water (Figure 3b). This faster reaction is consistent with a cationic aqua complex being a competent intermediate in the conversion of the palladium halide complex 1 to the palladium hydroxo complex 32, considering that exchange of the labile solvento ligand in 33 for water should occur readily. Furthermore, water could also play a role in driving the reaction forward by sequestering the resulting ammonium salts. Finally, the presumed basicity of the hydroxo ligand was confirmed by the immediate reversion of 32 back to 33 upon treatment with HBF4 etherate in THF at −25 °C (Figure S11).

While palladium hydroxo complexes have been proposed as intermediates in numerous cross-coupling reactions, their formation is generally believed to require anion exchange processes using stoichiometric ionic bases. Hydrolysis of halide ligands in a nonpolar organic solvent represents a unique and much milder pathway to access these versatile intermediates, yet such ionization processes have been proposed to be energetically prohibitive.9 This issue has been mitigated by moving away from halide electrophiles to those with weaker anions (e.g., triflate) or by addition of halide abstracting reagents (i.e., Ag+, Tl+), such as in methods that access the cationic pathway for the Mizoroki-Heck reaction.37 Our data suggest that an appropriate coordinatively-unsaturated metal intermediate, such as the T-shaped (Ad3P)Pd(II) species in this work, can in fact undergo facile ionization through hydrolysis even in toluene, which allows deprotonation of the resultant acidified aqua ligand in the cationic complex using very mild bases. To our knowledge, such a process represents a novel pathway for a key catalytic step of Buchwald-Hartwig amination reactions that activates the substrate amine, which engenders advantages in the electrophile scope to include more strongly coordinating anions (e.g., Br, Cl) without the need for halide scavengers.

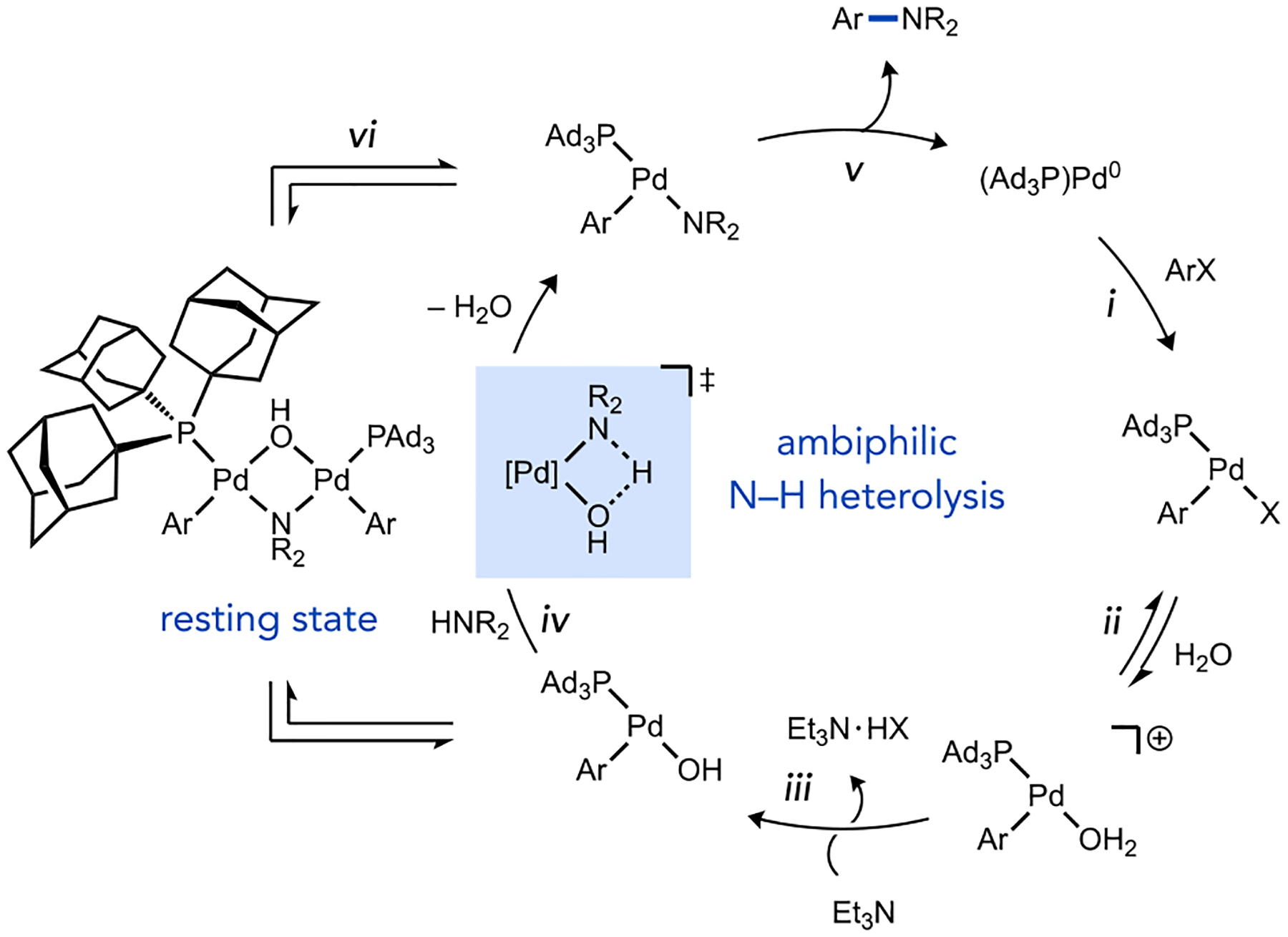

A catalytic cycle is proposed for (Ad3P)Pd-catalyzed aryl amination of aryl halides in Scheme 2, which incorporates a water-assisted mechanism to generate an ambiphilic Pd hydroxo species. To probe the turnover-limiting step, the experimental rate law (eq 1) was determined using either Burés’ variable time normalization analysis38

| (1) |

or initial rate measurements for reactions of 4-BrC6H4F (ArFBr) with aniline under the standard conditions of Table 1 (see Figures S37–S41). The observation of a nominally zeroth-order dependence of the initial rates on [ArFBr] and [Et3N] suggest neither oxidative addition (step i) nor deprotonation of water (step iii) are turnover-limiting, respectively, in the catalytic reaction. These results contrast prior work on amination of aryl triflates where either a positive order dependence on [DIPEA] signified rate-determining N–H deprotonation using a tertiary amine base, or a negative order dependence on [DBU] under different conditions indicated catalyst poisoning by this base.11a

Scheme 2.

Proposed catalytic cycle for (Ad3P)Pd -catalyzed, water-assisted amination.

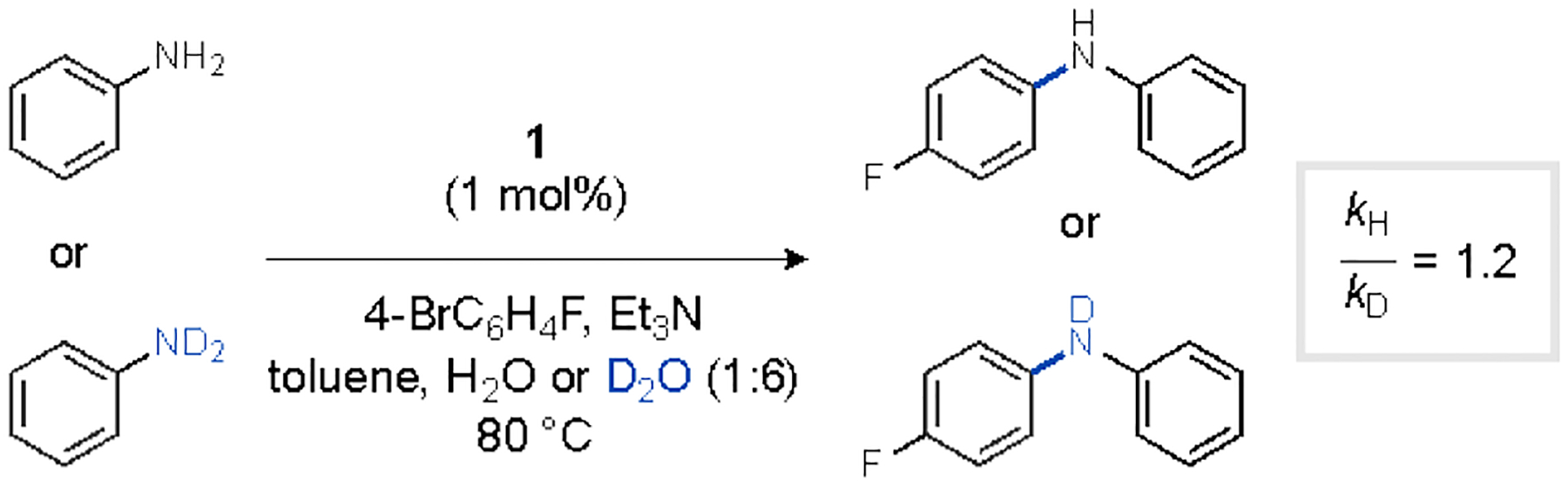

While the nominally zeroth-order dependence of the rate on [amine] is consistent with fast N–H heterolysis (step iv), it could also be manifested in a scenario in which amine coordination to Pd occurred reversibly and the equilibrium saturated in the range of concentrations tested. To distinguish between these possibilities, the kinetic isotope effect (KIE) was determined for independent reactions of ArFBr with aniline in toluene/H2O or aniline-d2 in toluene/D2O (Figure 4). The absence of a primary KIE in these reactions is inconsistent with turnover-limiting N–H heterolysis regardless of potential reversibility in amine substrate coordination.

Figure 4.

Determination of kinetic isotope effect from independent catalytic amination reactions of aniline or aniline-d2.

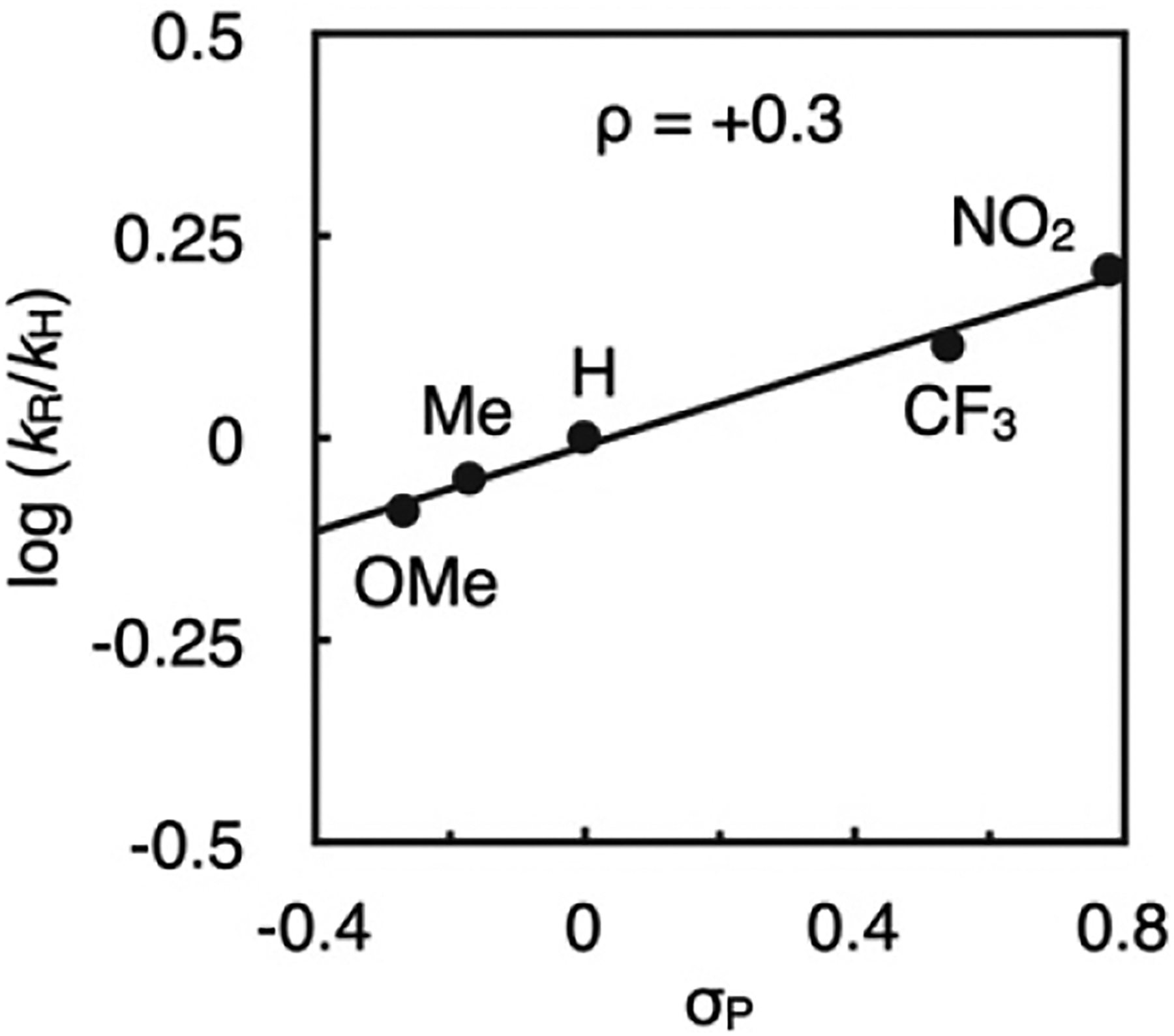

The kinetic and isotope effect data above seem to implicate C–N reductive elimination as the likely turnover-limiting step of catalysis. However, analysis of the initial rates for reactions using a series of para-substituted anilines (Figure 5) suggest C–N bond formation (step v) is not rate-determining. The slope of this Hammett plot (ρ = +0.3) is inconsistent with literature data for stoichiometric reductive elimination reactions from arylpalladium amido complexes, which are generally faster for complexes with more electron-rich amido ligands (ρ < 0).39 Considering also that stoichiometric reactions (see Figure 3) suggest hydrolysis is kinetically facile (step ii), the available data are not consistent with any on-cycle catalytic step being turnover-limiting. An alternative kinetic scenario must then be operative during these catalytic reactions, and spectroscopic data from additional stoichiometric experiments at low temperature with isolated organometallic complexes provided several key insights in this regard.

Figure 5.

Hammett plot for catalytic amination of 4-BrC6H4F with a para-substituted aniline under the optimized conditions of Table 1 as determined by the method of initial rates.

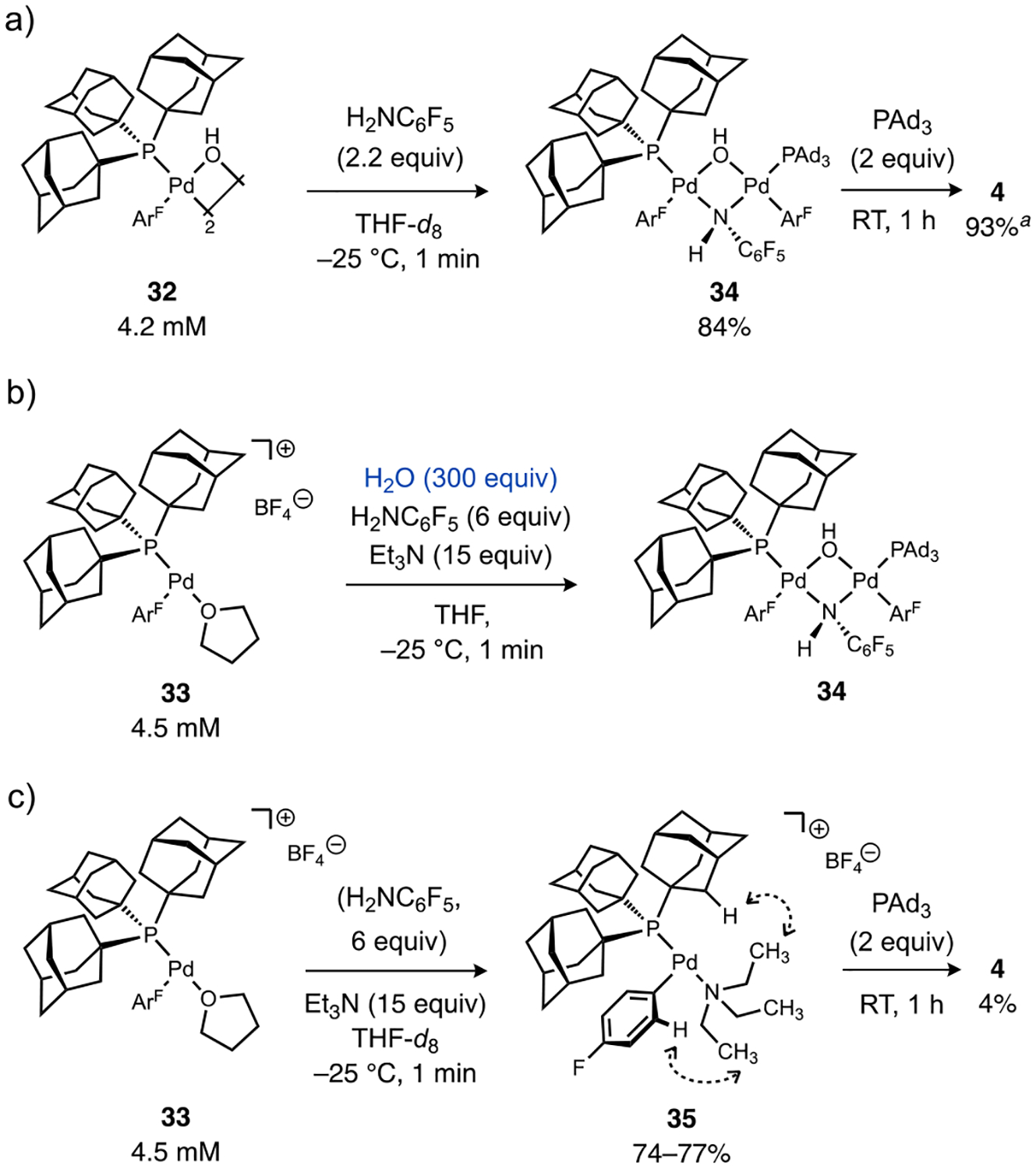

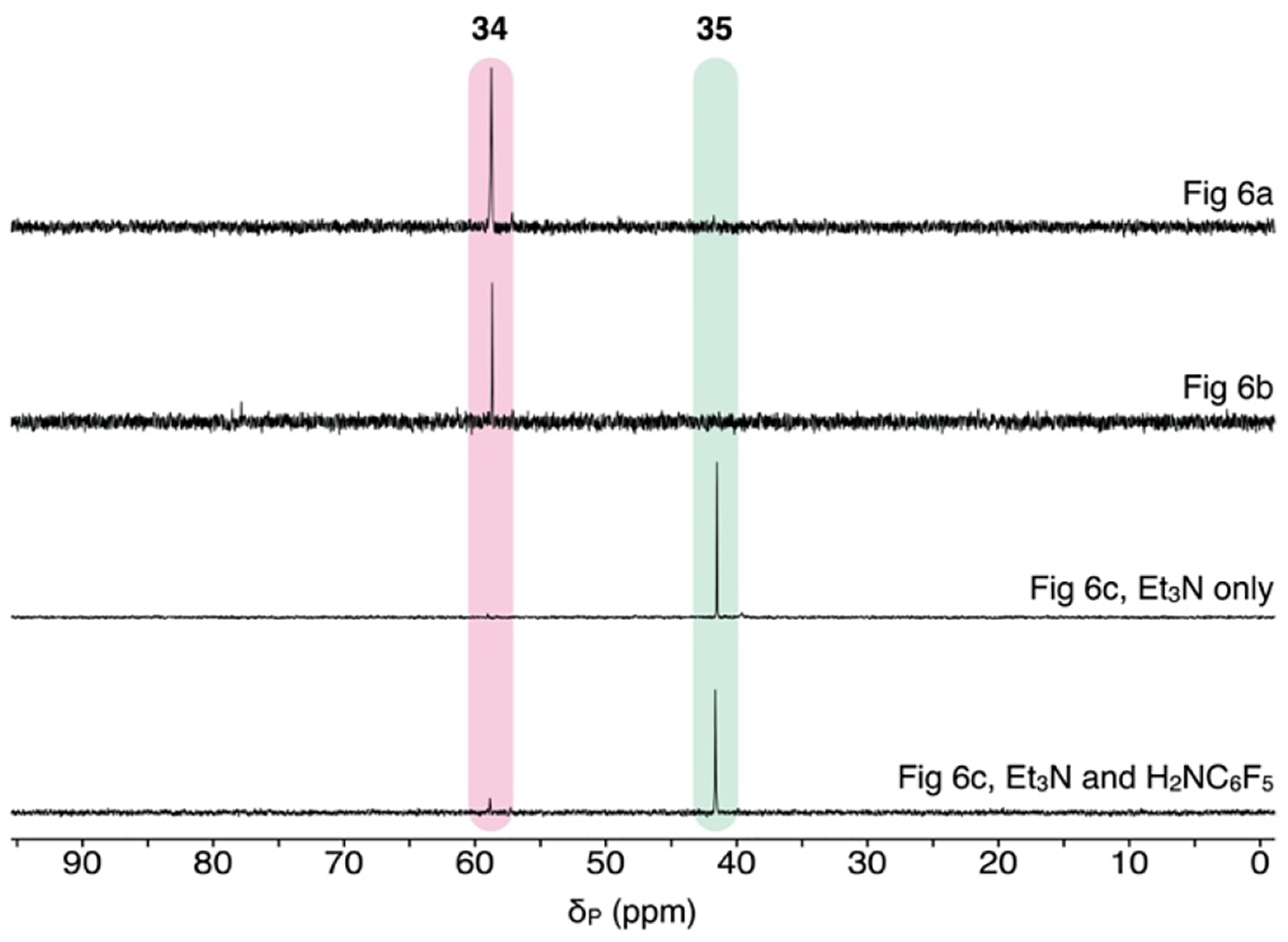

The stoichiometric N–H heterolysis of H2NC6F5 by Pd hydroxo complex 32 in THF occurred with full conversion of 32 within 1 min at −25 °C to generate a new palladium species (δP 58.8 ppm) in 84% yield (Figure 6a). The stoichiometry of μ-OH and μ-NHC6F5 resonances versus Pd(PAd3) and Pd(4-FC6H4) resonances (1:2, respectively) in the 1H NMR and single resonance in the 31P NMR spectra suggests a syn-dinuclear complex (34), which is structurally analogous to a {Pd2(PPh3)2Ph2(μ-OH)(μ-NHtBu)} species that was crystallographically characterized by Hartwig.25,40 When 34 was allowed to warm to room temperature, C–N reductive elimination occured completely to form 4 in 93% yield, relative to both [Pd]–ArF equivalents in the starting dimer complex 32, as determined by 19F NMR versus octafluorotoluene as standard. A yield of product 4 in excess of 50% necessitates the μ-OH ligand in the dinuclear intermediate 34 further reacts with the remaining H2NC6F5 in solution after C–N bond formation is triggered. The identification of this dinuclear species (34) can also resolve the issue of the turnover-limiting step during catalysis. Specifically, the observed reaction constant of ρ = +0.3 is consistent with rate-determining fragmentation of the μ-anilido ligand in species analogous to 34, which should be faster with decreasing ligand σ-donicity induced by withdrawing anilido substituents. Fragmentation of this dinuclear species can also rationalize the fractional dependence of the catalytic rate on [1] (0.9) within the mechanistic pathway outlined in Scheme 2 (see Supporting Information for full details).

Figure 6.

Stoichiometric N–H heterolysis reactions between aryl-palladium complexes, H2NC6F5, and Et3N with or without added water and characterization of the resulting amido-Pd or amino-Pd intermediates. Dashed lines indicate NOE-correlated 1H nuclei. aRelative to both [Pd]–ArF equivalents in 32. ArF = 4-FC6H4.

The reaction of cationic complex 33 with H2NC6F5, excess water, and Et3N in THF also occurred within 1 min at −25 °C to generate the same dinuclear intermediate 34 (Figure 6b). In contrast, an analogous reaction of 33 with Et3N in the absence of added water (Figure 6c) led to the consumption of starting material but generated a distinct product (δP 41.5 ppm) as shown in Figure 7. Characterization of this species by 1H and 1H–1H NOESY NMR is consistent with a cationic, Et3N-coordinated structure (35). Importantly, repetition of the reaction with added H2NC6F5 led to formation of the same species (Figure 7), but upon warming to room temperature only a trace (4%) of C–N coupling product 4 formed after 1 h. We interpret these results as suggesting that aniline substrates struggle to displace coordinated Et3N at Pd, and catalyst inhibition should occur using a soluble base as was observed previously by Buchwald.11a Because this does not appear to occur during the catalytic reactions of this work (reactions are zeroth- rather than inverse-order in [Et3N]), we postulate that another role of excess water can be to shunt catalyst away from an inactive state (e.g., 35) toward active intermediates, such as [Pd(PAd3)Ar(OH2)]+ and Pd(PAd3)Ar(OH). The rapid generation of the active Pd–OH species upon addition of water to the deactivated species 35 over 1 min at 0 °C is consistent with this notion (see Figures 3b and S32). In total, these mechanistic data strongly support a catalytic pathway unique from previous work on amination of aryl triflates using weak base for which the resting state is an off-cycle base-coordinated Pd species – an undesirable poisoned state that can be circumvented by the action of water together with the coordinative unsaturation enforced by the PAd3 ligand.

Figure 7.

31P NMR spectra of stoichiometric reactions of aryl-Pd complexes 32 or 33 with amines shown in Figure 6.

CONCLUSION

A method for amination of chloro- and bromo(hetero)arenes has been developed that operates efficiently with Et3N as a mild, soluble base in combination with water in toluene. The nucleophile classes applicable to this transformation span a wide pKa range from relatively acidic amides and electron-deficient anilines to poorly acidic aliphatic secondary amines. The mild conditions are also compatible with range of base sensitive functional groups that can be problematic under classic strong base conditions, which includes carboxylic acids, esters, nitrile, nitro, and enolizable keto groups. Amination in complex settings was validated by reactions of the chloroaryl group in the pharmaceuticals indomethacin, fenofibrate, and haloperidol as well as in five drug-like bromo(hetero)arenes. Reactions can also be conducted in neat water for applications requiring single solvent conditions.

Mechanistic experiments support multiple roles for water assistance in the catalytic mechanism. An initial hydrolysis of the organopalladium halide complex formed after oxidative addition is facilitated kinetically by the PAd3-enforced coordinative unsaturation of the complex, as well as thermodynamically driven through sequestration of the halide byproduct into the aqueous phase of a biphasic system. Importantly, this ionization occurs even for more strongly coordinated halide ions derived from commercially abundant bromo- and chloroarenes, which contrasts the typically difficult task of ionization Pd(II) complexes in nonpolar media that traditionally requires organic electrophiles with better leaving groups or halide scavengers. Deprotonation of an acidified aqua ligand in the cationic intermediate can occur readily even with Et3N, which corresponds to a considerable influence of the catalyst on relative acidities (ΔpKaDMSO = 22). The ambiphilic Pd(PAd3)(Ar)OH intermediate that is readily accessible from water and Et3N in these reactions features both Lewis acidic and Brønsted basic properties that, upon coordination of amine substrate, triggers an intramolecular N–H cleavage under very mild conditions.

Stoichiometric experiments with aryl-palladium complexes implicate another unanticipated role of water in shunting catalyst speciation away from inactive, base-coordinated intermediates, which has been a challenge in other recently developed weak base amination methods. To our knowledge, this water-assisted mechanism for C–N coupling reactions has not been previously observed and could potentially be effective in promoting other catalytic processes involving element-hydrogen bond activation under weak base conditions. The persistent coordinative unsaturation of the (Ad3P)Pd catalyst thus appears to engender a number of kinetic benefits in accessing unique catalytic mechanisms for carbon-carbon and now carbon-heteroatom bond forming reactions that are attractive for catalysis in the most sensitive settings.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (R35GM128902). We thank Prof. Guy Lloyd-Jones for assistance with kinetic modeling, Kiwoon Baeg and Lucy Wang for assistance with preliminary catalyst development, and Michael Peddicord for HR-MS analyses.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Experimental procedures. Reaction optimization details, kinetics data, and spectral data for new compounds.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): A patent was filed by Princeton University: Carrow, B. P.; Chen, L. WO2017/075581 A1, May 4, 2017.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Ruiz-Castillo P; Buchwald SL Applications of Palladium-Catalyzed C–N Cross-Coupling Reactions. Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 12564–12649; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Torborg C; Beller M Recent Applications of Palladium-Catalyzed Coupling Reactions in the Pharmaceutical, Agrochemical, and Fine Chemical Industries. Adv. Synth. Catal 2009, 351, 3027–3043; [Google Scholar]; (c) Devendar P; Qu R-Y; Kang W-M; He B; Yang G-F Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions: A Powerful Tool for the Synthesis of Agrochemicals. J. Agric. Food Chem 2018, 66, 8914–8934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Surry DS; Buchwald SL Biaryl Phosphane Ligands in Palladium-Catalyzed Amination. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2008, 47, 6338–6361; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hartwig JF Evolution of a Fourth Generation Catalyst for the Amination and Thioetherification of Aryl Halides. Acc. Chem. Res 2008, 41, 1534–1544; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Valente C; Çalimsiz S; Hoi KH; Mallik D; Sayah M; Organ MG The Development of Bulky Palladium NHC Complexes for the Most-Challenging Cross-Coupling Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51, 3314–3332; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chartoire A; Nolan SP CHAPTER 4 Advances in C–C and C–X Coupling Using Palladium–N-Heterocyclic Carbene (Pd–NHC) Complexes In New Trends in Cross-Coupling: Theory and Applications; The Royal Society of Chemistry: 2015, p 139–227; [Google Scholar]; (e) Stradiotto M Ancillary Ligand Design in the Development of Palladium Catalysts for Challenging Selective Monoarylation Reactions In New Trends in Cross-Coupling: Theory and Applications; Colacot T, Ed.; The Royal Society of Chemistry: 2015, p 228–253; [Google Scholar]; (f) Ingoglia BT; Wagen CC; Buchwald SL Biaryl monophosphine ligands in palladium-catalyzed C–N coupling: An updated User’s guide. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 4199–4211; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Forero-Cortés PA; Haydl AM The 25th Anniversary of the Buchwald–Hartwig Amination: Development, Applications, and Outlook. Org. Process Res. Dev 2019, 23, 1478–1483; [Google Scholar]; (h) Shaughnessy KH Development of Palladium Precatalysts that Efficiently Generate LPd(0) Active Species. Isr. J. Chem 2020, 60, 180–194. [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Old DW; Wolfe JP; Buchwald SL A highly active catalyst for palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions: Room-temperature Suzuki couplings and amination of unactivated aryl chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 9722–9733; [Google Scholar]; (b) Hartwig JF; Kawatsura M; Hauck SI; Shaughnessy KH; Alcazar-Roman LM Room-Temperature Palladium-Catalyzed Amination of Aryl Bromides and Chlorides and Extended Scope of Aromatic C−N Bond Formation with a Commercial Ligand. J. Org. Chem 1999, 64, 5575–5580; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wolfe JP; Buchwald SL A Highly Active Catalyst for the Room-Temperature Amination and Suzuki Coupling of Aryl Chlorides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 1999, 38, 2413–2416; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Huang J; Grasa G; Nolan SP General and Efficient Catalytic Amination of Aryl Chlorides Using a Palladium/Bulky Nucleophilic Carbene System. Org. Lett 1999, 1, 1307–1309; [Google Scholar]; (e) Stauffer SR; Lee S; Stambuli JP; Hauck SI; Hartwig JF High Turnover Number and Rapid, Room-Temperature Amination of Chloroarenes Using Saturated Carbene Ligands. Org. Lett 2000, 2, 1423–1426; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wolfe JP; Tomori H; Sadighi JP; Yin J; Buchwald SL Simple, Efficient Catalyst System for the Palladium-Catalyzed Amination of Aryl Chlorides, Bromides, and Triflates. J. Org. Chem 2000, 65, 1158–1174; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Stambuli JP; Kuwano R; Hartwig JF Unparalleled rates for the activation of aryl chlorides and bromides: coupling with amines and boronic acids in minutes at room temperature. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2002, 41, 4746–4748; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Shen Q; Shekhar S; Stambuli JP; Hartwig JF Highly Reactive, General, and Long-Lived Catalysts for Coupling Heteroaryl and Aryl Chlorides with Primary Nitrogen Nucleophiles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2005, 44, 1371–1375; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Marion N; Navarro O; Mei J; Stevens ED; Scott NM; Nolan SP Modified (NHC)Pd(allyl)Cl (NHC = N-Heterocyclic Carbene) Complexes for Room-Temperature Suzuki-Miyaura and Buchwald-Hartwig Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 4101–4111; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Navarro O; Marion N; Mei J; Nolan SP Rapid room temperature Buchwald-Hartwig and Suzuki-Miyaura couplings of heteroaromatic compounds employing low catalyst loadings. Chem.--Eur. J 2006, 12, 5142–5148; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Biscoe MR; Fors BP; Buchwald SL A New Class of Easily Activated Palladium Precatalysts for Facile C−N Cross-Coupling Reactions and the Low Temperature Oxidative Addition of Aryl Chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 6686–6687; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Shen Q; Hartwig JF [(CyPF-tBu)PdCl2]: An Air-Stable, One-Component, Highly Efficient Catalyst for Amination of Heteroaryl and Aryl Halides. Org. Lett 2008, 10, 4109–4112; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Fors BP; Watson DA; Biscoe MR; Buchwald SL A Highly Active Catalyst for Pd-Catalyzed Amination Reactions: Cross-Coupling Reactions Using Aryl Mesylates and the Highly Selective Monoarylation of Primary Amines Using Aryl Chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 13552–13554; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Organ MG; Abdel-Hadi M; Avola S; Dubovyk I; Hadei N; Kantchev EAB; O’Brien CJ; Sayah M; Valente C Pd-Catalyzed Aryl Amination Mediated by Well Defined, N-Heterocyclic Carbene (NHC)–Pd Precatalysts, PEPPSI. Chem. Eur. J 2008, 14, 2443–2452; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (o) Lundgren RJ; Sappong-Kumankumah A; Stradiotto M A Highly Versatile Catalyst System for the Cross-Coupling of Aryl Chlorides and Amines. Chem. Eur. J 2010, 16, 1983–1991; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (p) Crawford SM; Lavery CB; Stradiotto M BippyPhos: A Single Ligand With Unprecedented Scope in the Buchwald–Hartwig Amination of (Hetero)aryl Chlorides. Chem. Eur. J 2013, 19, 16760–16771; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (q) Weber P; Scherpf T; Rodstein I; Lichte D; Scharf LT; Gooßen LJ; Gessner VH A Highly Active Ylide-Functionalized Phosphine for Palladium-Catalyzed Aminations of Aryl Chlorides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2019, 58, 3203–3207; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (r) Tappen J; Rodstein I; McGuire K; Großjohann A; Löffler J; Scherpf T; Gessner VH Palladium Complexes Based on Ylide-Functionalized Phosphines (YPhos): Broadly Applicable High-Performance Precatalysts for the Amination of Aryl Halides at Room Temperature. Chem. Eur. J 2020, 26, 4281–4288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Reactions using LiHMDS as base can in certain circumstances tolerate hydroxyl, amide, and carbonyl groups. See:; Harris MC; Huang X; Buchwald SL Improved Functional Group Compatibility in the Palladium-Catalyzed Synthesis of Aryl Amines. Org. Lett 2002, 4, 2885–2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Beutner GL; Coombs JR; Green RA; Inankur B; Lin D; Qiu J; Roberts F; Simmons EM; Wisniewski SR Palladium-Catalyzed Amidation and Amination of (Hetero)aryl Chlorides under Homogeneous Conditions Enabled by a Soluble DBU/NaTFA Dual-Base System. Org. Process Res. Dev 2019, 23, 1529–1537. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Shevlin M Practical High-Throughput Experimentation for Chemists. ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2017, 8, 601–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Noël T; Buchwald SL Cross-coupling in flow. Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40, 5010–5029; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schoenitz M; Grundemann L; Augustin W; Scholl S Fouling in microstructured devices: a review. Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 8213–8228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Meyers C; Maes BUW; Loones KTJ; Bal G; Lemière GLF; Dommisse RA Study of a New Rate Increasing “Base Effect” in the Palladium-Catalyzed Amination of Aryl Iodides. J. Org. Chem 2004, 69, 6010–6017; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dooleweerdt K; Birkedal H; Ruhland T; Skrydstrup T Irregularities in the Effect of Potassium Phosphate in Ynamide Synthesis. J. Org. Chem 2008, 73, 9447–9450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Sunesson Y; Limé E; Nilsson Lill SO; Meadows RE; Norrby P-O Role of the Base in Buchwald–Hartwig Amination. J. Org. Chem 2014, 79, 11961–11969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).(a) Shekhar S; Ryberg P; Hartwig JF; Mathew JS; Blackmond DG; Strieter ER; Buchwald SL Reevaluation of the Mechanism of the Amination of Aryl Halides Catalyzed by BINAP-Ligated Palladium Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 3584–3591; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shekhar S; Hartwig JF Effects of Bases and Halides on the Amination of Chloroarenes Catalyzed by Pd(PtBu3)2. Organometallics 2007, 26, 340–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).For comparison of relative nucleophilicity, see:; (a) Dennis JM; White NA; Liu RY; Buchwald SL Pd-Catalyzed C–N Coupling Reactions Facilitated by Organic Bases: Mechanistic Investigation Leads to Enhanced Reactivity in the Arylation of Weakly Binding Amines. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 3822–3830; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ammer J; Baidya M; Kobayashi S; Mayr H Nucleophilic reactivities of tertiary alkylamines. J. Phys. Org. Chem 2010, 23, 1029–1035; [Google Scholar]; (c) Baidya M; Mayr H Nucleophilicities and carbon basicities of DBU and DBN. Chem. Commun 2008, 1792–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Buitrago Santanilla A; Christensen M; Campeau L-C; Davies IW; Dreher SD P2Et Phosphazene: A Mild, Functional Group Tolerant Base for Soluble, Room Temperature Pd-Catalyzed C–N, C–O, and C–C Cross-Coupling Reactions. Org. Lett 2015, 17, 3370–3373; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Buitrago Santanilla A; Regalado EL; Pereira T; Shevlin M; Bateman K; Campeau L-C; Schneeweis J; Berritt S; Shi Z-C; Nantermet P; Liu Y; Helmy R; Welch CJ; Vachal P; Davies IW; Cernak T; Dreher SD Nanomole-scale high-throughput chemistry for the synthesis of complex molecules. Science 2015, 347, 49–53; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ahneman DT; Estrada JG; Lin S; Dreher SD; Doyle AG Predicting reaction performance in C–N cross-coupling using machine learning. Science 2018, 360, 186; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Uehling MR; King RP; Krska SW; Cernak T; Buchwald SL Pharmaceutical diversification via palladium oxidative addition complexes. Science 2019, 363, 405–408; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Baumgartner LM; Dennis JM; White NA; Buchwald SL; Jensen KF Use of a Droplet Platform To Optimize Pd-Catalyzed C–N Coupling Reactions Promoted by Organic Bases. Org. Process Res. Dev 2019, 23, 1594–1601. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Dennis JM; White NA; Liu RY; Buchwald SL Breaking the Base Barrier: An Electron-Deficient Palladium Catalyst Enables the Use of a Common Soluble Base in C–N Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 4721–4725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Kashani SK; Jessiman JE; Newman SG Exploring Homogeneous Conditions for Mild Buchwald–Hartwig Amination in Batch and Flow. Org. Process Res. Dev 2020. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Corcoran EB; Pirnot MT; Lin S; Dreher SD; DiRocco DA; Davies IW; Buchwald SL; MacMillan DWC Aryl amination using ligand-free Ni(II) salts and photoredox catalysis. Science 2016, 353, 279–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Li C; Kawamata Y; Nakamura H; Vantourout JC; Liu Z; Hou Q; Bao D; Starr JT; Chen J; Yan M; Baran PS Electrochemically Enabled, Nickel-Catalyzed Amination. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 13088–13093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Hyde AM; Calabria R; Arvary R; Wang X; Klapars A Investigating the Underappreciated Hydrolytic Instability of 1,8-Diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene and Related Unsaturated Nitrogenous Bases. Org. Process Res. Dev 2019, 23, 1860–1871. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Liu RY; Dennis JM; Buchwald SL The Quest for the Ideal Base: Rational Design of a Nickel Precatalyst Enables Mild, Homogeneous C–N Cross-Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 4500–4507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Murthy Bandaru SS; Bhilare S; Chrysochos N; Gayakhe V; Trentin I; Schulzke C; Kapdi AR Pd/PTABS: Catalyst for Room Temperature Amination of Heteroarenes. Org. Lett 2018, 20, 473–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Chen L; Francis H; Carrow BP An “On-Cycle” Precatalyst Enables Room-Temperature Polyfluoroarylation Using Sensitive Boronic Acids. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2989–2994. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Chen L; Sanchez DR; Zhang B; Carrow BP “Cationic” Suzuki–Miyaura Coupling with Acutely Base-Sensitive Boronic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 12418–12421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lennox AJJ; Lloyd-Jones GC Transmetalation in the Suzuki–Miyaura Coupling: The Fork in the Trail. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2013, 52, 7362–7370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).(a) Thomas AA; Denmark SE Pre-transmetalation intermediates in the Suzuki-Miyaura reaction revealed: The missing link. Science 2016, 352, 329–332; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Thomas AA; Wang H; Zahrt AF; Denmark SE Structural, Kinetic, and Computational Characterization of the Elusive Arylpalladium(II)boronate Complexes in the Suzuki–Miyaura Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 3805–3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Palladium hydroxo species have been generated using amine bases:; Molloy JJ; Seath CP; West MJ; McLaughlin C; Fazakerley NJ; Kennedy AR; Nelson DJ; Watson AJB Interrogating Pd(II) Anion Metathesis Using a Bifunctional Chemical Probe: A Transmetalation Switch. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 126–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Driver MS; Hartwig JF Energetics and Mechanism of Alkylamine N-H Bond Cleavage by Palladium Hydroxides: N-H Activation by Unusual Acid-Base Chemistry. Organometallics 1997, 16, 5706–5715. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Nelson DJ; Nolan SP Hydroxide complexes of the late transition metals: Organometallic chemistry and catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev 2017, 353, 278–294. [Google Scholar]

- (27).(a) Kuwano R; Utsunomiya M; Hartwig JF Aqueous Hydroxide as a Base for Palladium-Catalyzed Amination of Aryl Chlorides and Bromides. J. Org. Chem 2002, 67, 6479–6486; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Huang X; Anderson KW; Zim D; Jiang L; Klapars A; Buchwald SL Expanding Pd-Catalyzed C−N Bond-Forming Processes: The First Amidation of Aryl Sulfonates, Aqueous Amination, and Complementarity with Cu-Catalyzed Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 6653–6655; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Urgaonkar S; Verkade JG Scope and Limitations of Pd2(dba)3/P(i-BuNCH2CH2)3N-Catalyzed Buchwald−Hartwig Amination Reactions of Aryl Chlorides. J. Org. Chem 2004, 69, 9135–9142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).These substrates were selected based on good HPLC resolution of starting materials and product in the high throughput assay.

- (29).(a) Pompeo M; Farmer JL; Froese RDJ; Organ MG Room-Temperature Amination of Deactivated Aniline and Aryl Halide Partners with Carbonate Base Using a Pd-PEPPSI-IPentCl- o-Picoline Catalyst. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2014, 53, 3223–3226; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Brusoe AT; Hartwig JF Palladium-Catalyzed Arylation of Fluoroalkylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 8460–8468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Widenhoefer RA; Buchwald SL Formation of Palladium Bis(amine) Complexes from Reaction of Amine with Palladium Tris(o-tolyl)phosphine Mono(amine) Complexes. Organometallics 1996, 15, 3534–3542. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Note that X4 and X8 are supplied as a mixture of diastereomers, which complicates analysis of potential epimerization of the enolizable stereocenter during the reaction.

- (32).Kutchukian PS; Dropinski JF; Dykstra KD; Li B; DiRocco DA; Streckfuss EC; Campeau L-C; Cernak T; Vachal P; Davies IW; Krska SW; Dreher SD Chemistry informer libraries: a chemoinformatics enabled approach to evaluate and advance synthetic methods. Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 2604–2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).(a) Dallas AS; Gothelf KV Effect of Water on the Palladium-Catalyzed Amidation of Aryl Bromides. J. Org. Chem 2005, 70, 3321–3323; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu C; Gong J-F; Wu Y-J Amination of aryl chlorides in water catalyzed by cyclopalladated ferrocenylimine complexes with commercially available monophosphinobiaryl ligands. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 1619–1623; [Google Scholar]; (c) Lipshutz BH; Chung DW; Rich B Aminations of Aryl Bromides in Water at Room Temperature. Adv. Synth. Catal 2009, 351, 1717–1721; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Pithani S; Malmgren M; Aurell C-J; Nikitidis G; Friis SD Biphasic Aqueous Reaction Conditions for Process-Friendly Palladium-Catalyzed C–N Cross-Coupling of Aryl Amines. Org. Process Res. Dev 2019, 23, 1752–1757. [Google Scholar]

- (34).(a) Shaughnessy KH Beyond TPPTS: New Approaches to the Development of Efficient Palladium-Catalyzed Aqueous-Phase Cross-Coupling Reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2006, 2006, 1827–1835; [Google Scholar]; (b) Shaughnessy KH Cross-Coupling Reactions in Aqueous Media In Palladium-Catalyzed Coupling Reactions; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, 2013, p 235–286; [Google Scholar]; (c) Carril M; SanMartin R; Domínguez E Palladium and copper-catalysed arylation reactions in the presence of water, with a focus on carbon–heteroatom bond formation. Chem. Soc. Rev 2008, 37, 639–647; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Shaughnessy KH Greener Approaches to Cross-Coupling In New Trends in Cross-Coupling: Theory and Applications; The Royal Society of Chemistry: 2015, p 645–696. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Zhang C; Vinogradova EV; Spokoyny AM; Buchwald SL; Pentelute BL Arylation Chemistry for Bioconjugation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2019, 58, 4810–4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).For examples of halide inhibition in C–C and C–N cross-coupling, see:; (a) Fuentes-Rivera JJ; Zick ME; Düfert MA; Milner PJ Overcoming Halide Inhibition of Suzuki–Miyaura Couplings with Biaryl Monophosphine-Based Catalysts. Org. Process Res. Dev 2019, 23, 1631–1637; [Google Scholar]; (b) Fors BP; Davis NR; Buchwald SL An Efficient Process for Pd-Catalyzed C−N Cross-Coupling Reactions of Aryl Iodides: Insight Into Controlling Factors. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 5766–5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Jutand A Mechanisms of the Mizoroki–Heck Reaction In The Mizoroki–Heck Reaction; Oestreich M, Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: West Sussex, 2009, p 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Burés J Variable Time Normalization Analysis: General Graphical Elucidation of Reaction Orders from Concentration Profiles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 16084–16087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).(a) Hartwig JF Electronic Effects on Reductive Elimination To Form Carbon−Carbon and Carbon−Heteroatom Bonds from Palladium(II) Complexes. Inorg. Chem 2007, 46, 1936–1947; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Arrechea PL; Buchwald SL Biaryl Phosphine Based Pd(II) Amido Complexes: The Effect of Ligand Structure on Reductive Elimination. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 12486–12493; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Peacock DM; Jiang Q; Hanley PS; Cundari TR; Hartwig JF Reductive Elimination from Phosphine-Ligated Alkylpalladium(II) Amido Complexes To Form sp3 Carbon–Nitrogen Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 4893–4904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Driver MS; Hartwig JF Carbon−Nitrogen-Bond-Forming Reductive Elimination of Arylamines from Palladium(II) Phosphine Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119, 8232–8245. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.