Abstract

Background

In 2018, the World Health Organisation (WHO) commenced a program of work to update the 2010 Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health, for the first-time providing population-based guidelines on sedentary behaviour. This paper briefly summarizes and highlights the scientific evidence behind the new sedentary behaviour guidelines for all adults and discusses its strengths and limitations, including evidence gaps/research needs and potential implications for public health practice.

Methods

An overview of the scope and methods used to update the evidence is provided, along with quality assessment and grading methods for the eligible new systematic reviews. The literature search update was conducted for WHO by an external team and reviewers used the AMSTAR 2 (Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews) tool for critical appraisal of the systematic reviews under consideration for inclusion. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) method was used to rate the certainty (i.e. very low to high) of the evidence.

Results

The updated systematic review identified 22 new reviews published from 2017 up to August 2019, 14 of which were incorporated into the final evidence profiles. Overall, there was moderate certainty evidence that higher amounts of sedentary behaviour increase the risk for all-cause, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer mortality, as well as incidence of CVD, cancer, and type 2 diabetes. However, evidence was deemed insufficient at present to set quantified (time-based) recommendations for sedentary time. Moderate certainty evidence also showed that associations between sedentary behaviour and all-cause, CVD and cancer mortality vary by level of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), which underpinned additional guidance around MVPA in the context of high sedentary time. Finally, there was insufficient or low-certainty systematic review evidence on the type or domain of sedentary behaviour, or the frequency and/or duration of bouts or breaks in sedentary behaviour, to make specific recommendations for the health outcomes examined.

Conclusions

The WHO 2020 guidelines are based on the latest evidence on sedentary behaviour and health, along with interactions between sedentary behaviour and MVPA, and support implementing public health programmes and policies aimed at increasing MVPA and limiting sedentary behaviour. Important evidence gaps and research opportunities are identified.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12966-020-01044-0.

Keywords: Exercise, Physical activity, Sedentary, Guidelines, Public health, Global health, Chronic disease, Cardiovascular, Type 2 diabetes, Cancer, Health promotion

Introduction

Sedentary behaviour is defined as any waking behaviour characterized by an energy expenditure ≤1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs), while in a sitting, reclining, or lying posture [1]. Most desk-based office work, driving or riding in a car, and watching television are examples of sedentary behaviours and can also apply to those unable to stand, such as wheelchair users. In most research studies to date involving ambulatory individuals, sedentary behaviour is typically operationalized as total daily sitting time, television viewing, or low counts on an accelerometer or activity monitor. Sedentary behaviours are considered conceptually distinct from physical inactivity, with the latter referring to performing insufficient amounts of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) to meet current physical activity recommendations. Indeed, it is possible to meet or exceed the public health guidelines for MVPA, and yet also spend most waking hours sedentary. At present, most published population-based estimates of sedentary behaviour are limited to high-income countries, with data on global trends in adults remaining scant. Accelerometer-based estimates from a recent review, derived from large or population-representative studies, indicate that adults spend approximately 8.2 h/day (range 4.9–11.9 h/day) sedentary [2].

Research on sedentary behaviour is relatively recent compared to that of physical activity. Indeed, much of the evidence on the detrimental health effects associated with sedentary behaviour has rapidly accumulated within the past decade. However, there have been notable developments, and the evidence-base is now at a level where dose-response relationships between sedentary behaviour and multiple health outcomes are being systematically examined, along with the interplay between sedentary behaviour and MVPA [3–7]. Given its high prevalence and increasing concern of the potential impact on public health, a growing number of countries are interested in and developing recommendations on sedentary behaviour at varying levels of specificity, either by incorporating them into their physical activity guidelines or by issuing specific sedentary behaviour guidelines (e.g. [8–12]).

In 2018, the World Health Organisation (WHO) was requested to update the 2010 Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health based on the latest available science, including sedentary behaviour, as part of global efforts to support countries to implement recommendations set out in the Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030 and achieve a 15% reduction in physical inactivity by 2030 [13]. WHO commenced this program of work and convened an international group of public health scientists and practitioners to serve on the Guideline Development Group (GDG) [14]. The purpose of this paper is to briefly summarize and highlight the scientific evidence that underpinned the new sedentary behaviour guidelines and its strengths and limitations. We also discuss the public health importance and practical implications of these new guidelines and outline several important evidence gaps and future research directions.

Methods

The guideline development process followed WHO protocols [15] and included establishing a guideline development group (GDG) who met in July 2019 to review and finalise the scope and agree on the methods. Full details of the procedures for identifying and grading the evidence are described in detail elsewhere [14, 16]. The evidence-base around sedentary behaviour and health outcomes in youth are detailed separately [17].

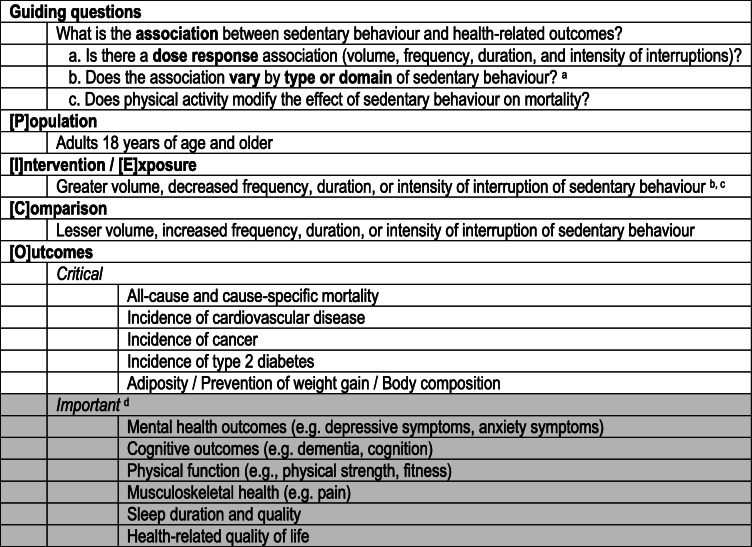

Briefly, the critical outcomes that were examined and the set of PI/ECO (Population, Intervention/Exposure, Comparison, Outcome) questions are shown in Table 1. Literature searches were undertaken to update the most recent and relevant systematic reviews for the critical outcomes only and not the important outcomes (see Table 1), which for sedentary behaviours and adults were identified to be the comprehensive syntheses of evidence undertaken by the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee (PAGAC) Scientific Report from the United States [9].

Table 1.

Scope and PI/ECO questions related to sedentary behaviour and health outcomes in adults

a The search to update the evidence used the same search terms as PAGAC and they were likely broad enough to pick up any relevant systematic reviews on type or domain of sedentary behaviour. However, it is noted that PAGAC did not specifically address this question in their final scope and thus some evidence may have been missed

b Sedentary behaviour exposure measures operationalised as either: total sitting time, screen-time, leisure-time sitting, occupational sitting time, accelerometer measured sedentary time [1, 9]

c Evidence on bouts and breaks in sedentary behaviour was also examined. A ‘bout’ of sedentary behaviour can be operationalized as a period of uninterrupted sedentary time, whereas a ‘break’ in sedentary behaviour can be operationalized as a non-sedentary bout in between two sedentary bouts [1]

d New searches were not conducted for the ‘important’ outcomes due to anticipated time/resource constraints, hence no results nor conclusions are reported for these outcomes

The literature search update was conducted for WHO by an external team and reviewers used the AMSTAR 2 (Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews) tool for critical appraisal of the systematic reviews under consideration for inclusion [18]. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) method was used to rate the certainty (i.e. very low to high) of the evidence for each PI/ECO (see Additional File 1) [19, 20].

The GDG considered both the evidence reported by the PAGAC and new reviews identified to make recommendations on health outcomes and sedentary behaviour for all adults and older adults. Other considerations such as values, preferences and risks and identified evidence gaps were also appraised. Observational evidence from reviews including more well-conducted longitudinal studies were upgraded to better reflect the increased certainty in findings and improved inferences about the causal structure of associations between sedentary behaviour and health outcomes from such studies. Greater emphasis was given to evidence provided by reviews graded moderate or above, and to those reviews providing evidence from studies using measures of total sedentary or sitting time, or device-based measures of sedentary time, where available.

Results

The PAGAC report provided systematic-review-level evidence published from 2011 to 2016 on sedentary behaviour and all-cause (n = 9), cardiovascular disease (CVD; n = 5) and cancer (n = 5) mortality, and type 2 diabetes (n = 5), weight status (n = 2), CVD (n = 5) and cancer (n = 8) incidence in adults. PAGAC applied a modified evidence grading protocol which is fully described elsewhere [9, 21, 22].

The updated search for systematic reviews identified 22 potential new reviews published from 2017 to August 2019. Of these, 17 reviews met inclusion criteria (five were excluded because their study exposures or design were out-of-scope) and a further three reviews were excluded because they had critically low credibility ratings (Table 2). The 13 remaining reviews provided updated evidence on all-cause, CVD and cancer mortality, type 2 diabetes, CVD and cancer incidence, and adiposity. For a detailed summary of the grading of meta-analyses and systematic reviews that contributed new evidence to inform the GDG conclusions, see the WHO report [16] and Web Annex Evidence Profiles (Tables B.2.a-e).

Table 2.

Credibility ratings for identified new reviews according to 16 item AMSTAR 2 tool

| Author, Year | ACM | Cause-specific mortality | CVD | Cancer | Diabetes | Adiposity | Last Search Date | AMSTAR 2 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmad 2017 [23] | X | X | X | Dec 2016 | Moderate | |||

| Bailey 2019 [24] | X | X | Feb 2019 | Moderate | ||||

| Berger 2019 [25] | Prostate | Prostate | Jan 2019 | Moderate | ||||

| Chan 2019 [26] | Breast | Apr 2017 | Moderate | |||||

| del Pozo-Cruz 2018 [6] | X | X | X | X | Dec 2016 | Moderate | ||

| Ekelund 2018 [3] a | CVD, Cancer | Oct 2015 | Moderate | |||||

| Ekelund 2019 [5] | X | Jul 2018 | Moderate | |||||

| Ku 2018 [27] | X | Jan 2018 | Moderate | |||||

| Ku 2019 [28] | X | Mar 2019 | Moderate | |||||

| Lee 2019 [29] | Ovarian | Dec 2017 | Critically Low e | |||||

| Ma 2018 [30] | Colorectal | Feb 2017 | Critically Low e | |||||

| Mahmood 2017 [31] | Colorectal | Dec 2015 | Low | |||||

| Mañas 2017 [32] | X b | Oct 2016 | Critically Lowe | |||||

| Patterson 2018 [7] | X | CVD, Cancer | X | Sep 2016 | Low | |||

| Shepard 2017 [33] | Bladder | Jun 2016 | Critically Lowe | |||||

| Wang 2018 [34] | Colorectal | Sep 2018 | High | |||||

| Xu 2019 [35] c | X | May 2018 | Low |

a Secondary data analysis of 2016 review [4]

b Not included for all-cause mortality given better quality reviews reporting this outcome

c Individual participant data meta-analysis

d See WHO report [16] for details on the AMSTAR 2 tool to rate the credibility of the evidence and the full evidence profiles

e Reviews rated as having critically low credibility were not incorporated into the final evidence profiles

Evidence

All-cause and cause-specific mortality (Web Annex, Table B.2.a)

A recent high certainty harmonised meta-analysis (eight prospective studies; n = 36,383) in middle aged and older adults (mean age 62.6 years; 72.8% women) showed a non-linear positive dose-response relationship between accelerometer-measured sedentary time and all-cause mortality [HRs and 95% CI per quartile of higher sedentary time relative to the least sedentary referent, after adjustment for potential confounders including time spent in MVPA: 1.28 (1.09 to 1.51), 1.71 (1.36 to 2.15), and 2.63 (1.94 to 3.56)], with mortality risks increasing gradually from approximately 7.5 to 9 h/day and becoming more pronounced from > 9.5 h/day [5]. Another recent comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis of over a million participants [7] also found non-linear positive associations for total sedentary behaviour (mostly self-reported) with all-cause mortality (RR per 1 h/day = 1.01 (95% CI = 1.00–1.01) for ≤8 h/day and 1.04 (95% CI = 1.03–1.05) for > 8 h/day of exposure) and cardiovascular disease mortality (RR = 1.01 (95% CI = 0.99–1.02) for ≤6 h/day and RR = 1.04 (95% CI = 1.03–1.04) for > 6 h/day), although associations with cancer mortality were not statistically significant, after adjustment for physical activity.

A new harmonized meta-analysis (CVD mortality, 9 studies, n = 850,060; Cancer mortality, 8 studies, n = 777,696) provided high certainty evidence on whether associations between self-reported sitting (and TV viewing) varied among different strata of MVPA for CVD and cancer mortality [3]. Significant dose–response associations (9–32% higher risk) were shown for sitting time and CVD mortality in the inactive, lowest quartile of MVPA (~ 5 min/day). More specifically, the hazard of cardiovascular disease mortality was 32% higher in those who sat > 8 h/day compared with the reference group (< 4 h/day). The results were less pronounced but remained statistically significant compared with the reference group for the second (HR = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.03–1.20) and third quartiles (HR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.03–1.26) of MVPA, but this association was mitigated in the most active quartile (~ 60–75 min/day). This review also found that associations for sedentary behaviour and cancer mortality were generally weaker, although a 6–21% higher dose-related risk was observed with higher sitting time (particularly > 8 h/day) among those who were in the lowest quartile of MVPA (~ 5 min/day), with hazard ratio’s largely attenuated in the highest quartile of MVPA. These new findings build upon previous harmonized meta-analyses [4] and show overall that the associations of sedentary behaviour and risk for all-cause, CVD and cancer mortality appear to be more pronounced at lower levels of MVPA than at higher levels, but that higher levels of MVPA (i.e. about 60–75 min/day) can largely mitigate the increased risks of sedentary behaviour.

Type 2 diabetes, CVD, and cancer incidence (Web Annex, Table B.2.b-d)

Two new moderate certainty reviews [including eleven prospective studies (n = 400,292) and five prospective studies (n = 4575) with two duplicates, and slightly different foci in terms of exposure and study inclusion criteria], examined associations of total daily sitting time [24] and total sedentary behaviour (mostly self-reported) [7] with type 2 diabetes incidence. Small linear associations were observed for increments of 1 h/d in total sedentary behaviour (RR = 1.01, 95% CI = 1.00, 1.01) [7], while higher levels of total sitting time were also associated with increased risk of diabetes incidence (HR = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.19) after adjustment for physical activity [24]. Bailey et al. also found an increase in incident CVD risk (HR = 1.29 (95% CI, 1.27 to 1.30) with total sitting, which was attenuated following statistical adjustment for physical activity (HR = 1.14 (95% CI, 1.04 to 1.23)) [24]. Four new reviews [25, 26, 31, 36] reporting on sedentary behaviour and cancer incidence all had very low to low certainty ratings, mostly attributable to a lack of adjustment for confounding variables, indirectness in terms of diversity of outcome assessment, and high statistical heterogeneity. However, evidence from three meta-analyses [37–39] previously summarized [9] provided moderate certainty evidence for an association between sedentary behaviour and type cancer incidence (endometrial, colon, and lung cancers).

Adiposity (Web Annex, Table B.2.e)

Only two new reviews for adiposity [6, 40] were identified. Both were of very low certainty and included mostly cross-sectional studies with higher risk of bias [i.e. thirteen cross sectional studies and one prospective study (n = 13,395) and six cross-sectional studies (n = 4774)]. The results reported were consistent with previous reviews [9] and showed limited, heterogeneous, and/or low certainty evidence for a small association between sedentary behaviour and adiposity markers (i.e. BMI and waist circumference), and low/insufficient certainty evidence for a dose-response relationship.

Overall conclusions, extrapolation to sub-populations, and WHO guidelines

Table 3 provides a summary of the relationships and level of evidence for each health outcome examined with sedentary behaviour, which was largely consistent and complementary between the systematic reviews. Overall, there was moderate certainty systematic review evidence for a direct association (i.e. an ‘independent’ association after adjustment for potential confounders, including MVPA) between higher amounts of sedentary behaviour and increased risk of all-cause, CVD and cancer mortality, as well as CVD, cancer, and type 2 diabetes incidence; however, evidence was limited and of low certainty for adiposity markers. Moderate certainty evidence also supported a non-linear dose-response relationship between sedentary behaviour and all-cause, CVD and cancer mortality, and incident CVD. This evidence provided sufficient support for new recommendations to limit sedentary time and replace it with activity of any intensity to reduce health risks (see Table 4) and the benefits of limiting sedentary behaviour were deemed to outweigh the risks. However, given the considerable variations in how sedentary behaviour was assessed (via self-reported sitting time, television viewing time, or device-based (accelerometer) assessments) and reported in studies, it was concluded there was insufficient evidence to set quantified (time-based) recommendations (Table 3). It was also considered probable that specific thresholds for sedentary time were likely to vary across health outcomes, by levels of MVPA (see below), and among population sub-groups.

Table 3.

Summary of relationships and level of evidence for sedentary behaviour and each health outcome in adults

| Health Outcomes | Evidence for association | Evidence for dose-response c | Evidence for variation in association by physical activity | Evidence for type or domain of sedentary behaviour |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Insufficient |

| CVD mortality | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Insufficient |

| Cancer mortality | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Insufficient |

| Incident type 2 diabetes | Moderate | Low | Insufficient | Insufficient |

| Incident CVD | Moderate | Moderate | Insufficient | Insufficient |

| Incident cancer a | Low-moderate b | Low | Insufficient | Insufficient |

| Adiposity | Low/insufficient | Low/insufficient | Insufficient | Insufficient |

See the WHO report [16] for details on the framework to rate the certainty of the evidence and the full evidence profiles

a Includes endometrial, colon, and lung cancers. Evidence graded very low to low certainty for other cancer types

b Level of evidence rating based on evidence from PAGAC reviews [9]

c It was concluded that there was insufficient evidence to set quantified (time-based) recommendations

Table 4.

The new WHO sedentary behaviour guidelines for adults and older adultsa (strong recommendation, moderate certainty evidence)

| 1. Adults and older adults should limit the amount of time spent being sedentary. Replacing sedentary time with physical activity of any intensity (including light intensity) has health benefits. | |

| 2. To help reduce the detrimental effects of high levels of sedentary behaviour on health, and older adults should aim to do more than the recommended levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. |

a Guidelines 1 and 2 were extrapolated to those living chronic conditions and/or disabilities, and only guideline 1 was extrapolated for pregnant and postpartum women (strong recommendation, low certainty evidence; without contraindication)

There was moderate certainty evidence that the associations between sedentary behaviour and all-cause, CVD and cancer mortality vary by level of MVPA when modelled in joint or stratified analyses. In other words, higher amounts of MVPA (i.e. about 60–75 min/day) can attenuate the detrimental association between sedentary behaviour and health outcomes. This underpinned additional guidance around increased levels of MVPA in the context of high levels of sedentary time to help reduce the risks (see Table 4).

In addition to overall volume of sedentary behaviour, the patterns by which sedentary behaviour is accrued were reviewed. However, consistent with previously summarized evidence syntheses [9], there was insufficient or low-certainty systematic review evidence to make recommendations on the frequency and/or duration of bouts or breaks in sedentary behaviour. The possibility that some types or domains of sedentary behaviour may be more detrimental to health than others, both in terms of their direct associations and their potential to displace time spent in more healthful physical activity, was also considered. For example, some studies report stronger associations with sedentary behaviour reported as TV viewing compared with total sitting time [7]. This may be due to differences in the behaviours themselves, differential measurement error/validity, or differences in residual/unmeasured confounding associated with the self-report measures and instruments, but further research is still needed to untangle this. Similarly, some misclassification may occur from device-based measures of sedentary time as many of these device placements (e.g. wrist, waist) do not currently distinguish between positions (e.g. lying, sitting, and standing still). At present, there is insufficient/low certainty review-level evidence directly comparing associations between different types/domains of sedentary behaviour to make any conclusions or recommendations.

Direct evidence on sedentary behaviours and health outcomes in people living with disabilities or chronic conditions, or pregnant or postpartum women, remains sparse. However, the evidence reviewed in the general adult population, including the benefit of undertaking more MVPA to help counteract the potential risks of high levels of sedentary behaviour, was considered applicable (assuming no contraindications) and therefore extrapolated to inform guidelines on sedentary behaviour for these specified sub-populations [41, 42] for a common set of critical health outcomes, with a downgrading of certainty to reflect indirectness (see Table 4). In extrapolating this evidence to people living with disabilities, it was recognized that certain population groups, such as wheelchair users, unavoidably sit for long periods of time and sitting may therefore be the norm. For these groups, sedentary behaviour is best defined based on the low energy expenditure component, rather than the postural component (e.g. moving in a power chair or being pushed in a wheelchair). The final guidelines on sedentary behaviour for all adults and older adults are detailed in Table 4.

Discussion

In the past decade, there has been a rapid accumulation of evidence on the prospective associations between sedentary behaviour and several critical public health outcomes (see Table 3). With increasing concerns around low prevalence of physical activity and rising levels of sedentary behaviour among many populations worldwide, important public health gains could be made by limiting excessive sedentary behaviour and replacing it with more physical activity of light, moderate or vigorous intensity. As such, the incorporation of new evidence-based recommendations on sedentary behaviour for all adults and older adults within the 2020 WHO guidelines marks an important step forward, while complementing and extending existing physical activity guidelines.

Although the evidence reviewed shows that sedentary behaviour is clearly related to several health outcomes, there remains some imprecision and uncertainty in the characteristics of the specific dose-response curves, which in turn has made it difficult to provide specific quantitative public health recommendations. As researchers and policy makers enter this new era of joint physical activity and sedentary behaviour recommendations, three important evidence and practice gaps warrant further contextualisation and discussion:

1. No specific or quantified (time-based) threshold for sedentary time: Identifying whether there is a threshold of sedentary behaviour which is associated with increased health risk is of public health and policy relevance. Although there was some consistency in the positive dose-response relationships between sedentary time and mortality outcomes (but less so for type 2 diabetes and cancer incidence or adiposity) to support clear statements to limit sedentary time overall (see Table 3), there was insufficient evidence to identify a specific time-based threshold. Limitations in the evidence included the variations in how sedentary time has been measured or reported across all the major reviews, which complicates the identification of specific quantitative thresholds. Moreover, the evidence reviewed showed that thresholds of increased risks for sedentary time are likely to vary depending upon the level of MVPA (as described in the second sedentary behaviour recommendation; also see point 2), by health outcome, and among different population sub-groups (e.g. defined by age, sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or weight status, etc). Future reviews that include well-harmonised and/or device-based measures of total sedentary time in ethnically and culturally diverse populations could help inform more specific quantifications around the amounts of sedentary time that significantly increase health risks. However, evidence to inform such sedentary guidance is complex and will also need to be considered within the context of its inter-relationships with physical activity of various types/intensities.

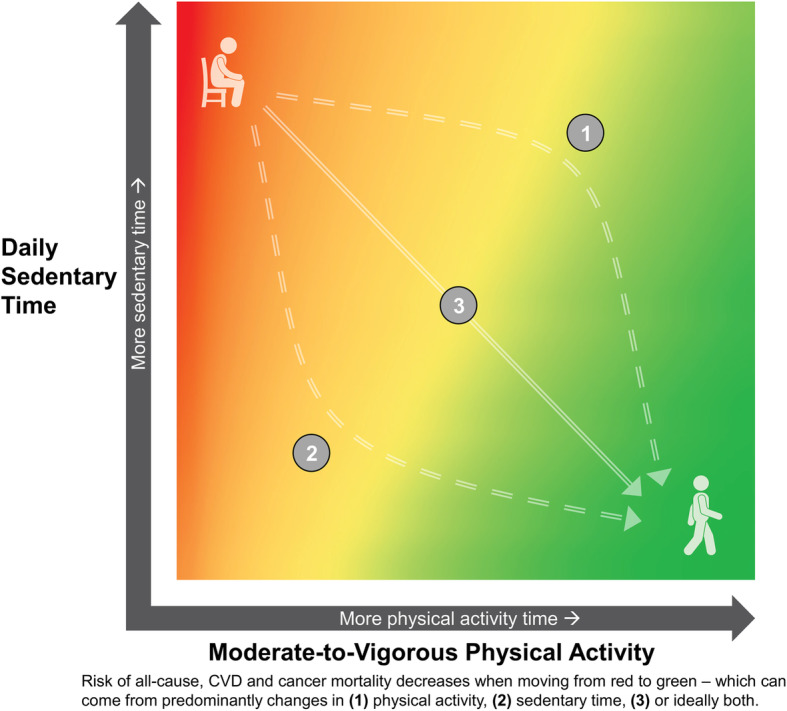

2. The feasibility of achieving or exceeding the upper limits of MVPA guidelines to reduce the detrimental effects of “high levels” of sedentary behaviour: The new evidence reviewed demonstrating that high levels of MVPA (i.e. > 300 min/week) can largely offset the mortality risks associated with sedentary behaviour is good news for those who are highly sedentary, but who are also able to achieve high levels of MVPA. This evidence emphasizes the role of MVPA in offsetting the potential harms associated with excessive sedentary time (see Table 4). However, achieving such high levels of MVPA may be a challenge for large segments of the population, as illustrated by the high proportion of people not meeting the lower limit for MVPA guidelines [43, 44]. Dual sedentary behaviour guidelines therefore emphasize and support added flexibility in options, through encouraging the use of multiple approaches or strategies to reduce risk. These could include lowering total sedentary time (and likely increasing light-intensity activity), increasing MVPA time or, ideally, some combination of both strategies. This integration concept is illustrated elegantly by the heat map developed by the PAGAC [9], which shows conceptually that many combinations of less sedentary time and more MVPA can be associated with a reduced risk of all-cause mortality (see Fig. 1) – evidence which has now been extended to include CVD and cancer mortality outcomes [3]. Importantly, the new WHO guidelines point to the importance of attending to both physical activity (i.e. of light, moderate, and vigorous intensity) and sedentary time to try to optimize the “balance” of these behaviours for better health. The dual sedentary recommendations also promote more inclusivity towards a broader variety of sub-populations – including large portions of the population who are physically inactive or obese, or who have chronic conditions or disabilities – for whom achieving high levels of MVPA may be challenging.

Fig. 1.

Joint associations of sedentary (sitting) time and MVPA with risk of all-cause mortality based on data by Ekelund et al. [4] – now also broadly applicable for risk of CVD and cancer mortality [3]. Orange and yellow shading represents transitional decreases in risk. For context, data analysis ranges for all-cause mortality [4] were based on four levels of self-reported sedentary time (< 4, 4–6, 6–8, > 8 h/day) and MVPA (∼5, 25–35, 50–65, 60–75 min/day), but specific scales are intentionally left blank and could vary considerably for either device-based measures (e.g. hip or thigh accelerometry), by different health outcomes (e.g. type 2 diabetes, adiposity), or by different sub-populations (e.g. frail/elderly adults, people living with some chronic conditions or disabilities). Heat map adapted from the PAGAC [9] report

3. No specific recommendations on how to break up sedentary behaviour: Information on sedentary break and bout accumulation patterns in relation to health outcomes represents a promising and potentially powerful public health messaging tool. However, operationalising and analysing sedentary break and bout accumulation pattern data, distinct from the volume of time spent in sedentary and active behaviours, requires more clarity and detailed interrogation. There was insufficient or low-certainty systematic review evidence on the frequency and/or duration of bouts or breaks in sedentary behaviour with health outcomes to make specific recommendations. A lack of evidence to date is likely due in part to the reliance on device-based measures, and some heterogeneity/limitations in how bouts and breaks in sedentary time are summarized. Some emerging but limited evidence is available from short to medium duration randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective cohort studies with clinical endpoints. However, it should also be noted that most of the review-level evidence is based on cross-sectional [45] or acute laboratory-based [46] studies, or free-living short to medium duration intervention studies with behavioural or surrogate disease risk biomarkers as primary outcomes [47–49].

Key limitations/gaps in the evidence base and future directions

Several limitations and gaps in the current evidence base were identified and future research recommendations generated from this work, some of which are also broadly covered in a separate paper [50]. Key future directions and opportunities are detailed below. More research in all of these areas would lead to more specificity and generalisability in guidelines, such as what types/domains of sedentary behaviours to limit most, the role of standing in replacing sitting, which types/domains of sedentary behaviours may be neutral or even health-promoting, and specific daily or weekly time-based thresholds/ranges above which there are important health risks. Advances in measurement tools and analytics, as well as better data harmonization or pooling across studies, should support and provide important insights towards these areas. However, it is important that such research is paralleled by greater efforts to improve global surveillance and data collection across a diversity of sub-populations and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including those from more disadvantaged/vulnerable backgrounds, where evidence remains particularly scant.

1. Measurement and analytics: Most of the evidence reviewed by the GDG was derived from self-reported sitting and TV viewing time, with less evidence from device-based measures of sedentary behaviour or sitting per se. There is a need to develop and incorporate better field-based measurement methods to adequately quantify time spent in sedentary behaviours. Such methods should quantify both postural and energy expenditure components, consistent with the accepted sedentary behaviour definition, and ideally also capture more detailed information on the type and domain of sedentary behaviour (e.g. occupational, sedentary screen time, active/passive sedentary behaviours, upper and lower-body fidgeting, etc). To capture all such elements will likely require combinations of both self-report and device-based methods, including possible use of wearable cameras. Moreover, since sedentary time, light-intensity physical activity, MVPA and sleep all co-exist and interact within a finite 24-h day or energy total, analytical methods that better account for the relative time- and energy-use compositions of these behaviours will provide more useful insights into correlates and behavioural associations with health outcomes [51–53]. Similarly, better analytical methods to identify, standardize, and summarize information on sedentary breaks and bout accumulation patterns (distinct from total sedentary volume or other time-uses) will provide more useful information when examining associations with prospective health outcomes.

2. Outcomes, mechanisms, and context: More prospective evidence is needed on a broader range of health and psycho-biological outcomes. The bulk of the literature so far, including the evidence synthesis for this review, relies on mortality or cardiometabolic outcomes. Similar to physical activity, future guidelines should ideally be based on evidence from a more comprehensive suite of important health or health-related outcomes, including: specific cancers; mental health (including affective responses); cognitive/brain health; musculoskeletal health and falls; social outcomes; and quality of life. More experimental and etiological research that informs biological mechanisms (both acute and longer term) and potential causal pathways linking sedentary behaviour with health outcomes will also be highly informative [54]. Examples include: experimental evidence on direct effects of exposures to different types, postures, or patterns of sedentary behaviour; residual/unmeasured confounding issues (e.g. socioeconomic status, diet, occupation type, mental health, functional status, cancer screening); untangling issues around reverse or bi-directional causality and mediation (e.g. for type 2 diabetes and adiposity); effect modification by key demographic and personal characteristics (e.g. sex, age, race/ethnicity, chronic conditions, disabilities, socioeconomic status, occupation type, adiposity, and cardiorespiratory fitness); and interactions between sedentary time and physical activity across the intensity spectrum (e.g. light, moderate, and vigorous).

3. Examining options for limiting sedentary behaviour in RCTs: Building on previous points, research that encapsulates the full 24-h range of behaviours (e.g. sleep, sedentary time, light-intensity physical activity, and MVPA) will inform sedentary behaviour guidelines by providing guidance on how to replace sedentary time optimally. In particular, the positive or negative consequences of replacing sedentary time with additional sleep duration, standing, and various other activities within the wide range of light-intensity activities, and for whom, is of interest. Ideally, these questions should be examined within the context of high-quality RCTs targeting a variety of sub-populations, using harmonizable measures of these behaviours. This research will allow specific replacement effects to be more reliably ascertained through later individual-level participant data analyses and meta-analytic approaches [47]. Finally, a better understanding of the key biological or modifiable determinants (or “drivers”) of sedentary behaviour (a behaviour which can often be habitual and socially/environmentally reinforced) will also be crucial in informing the design, targeting, and implementation of the above RCTs, as well as more effective, evidence-based interventions and policies to change sedentary time [55].

4. An uneven evidence base generated in high-income countries: To date, most evidence on sedentary behaviour (and physical activity) has been built on studies examining populations predominately from western high-income countries. Therefore, the prevalence, context, and generalisability of different amounts, types, and patterns of sedentary behaviour – particularly in terms of determinants, health impacts, and targeted interventions – remains less clear for populations in LMICs. A global perspective and more high-quality empirical data in a diversity of sub-populations and LMICs is therefore needed. This need is particularly pressing since LMICs are already experiencing economic and societal transitions that are expected to lead to rapid urbanisation and more sedentary jobs/societies. Indeed, populations in LMICs are already experiencing higher global disease burden or differential disease patterns compared to high-income countries [56, 57]. It seems likely that some underlying institutional, social, and cultural practices between countries will mean that sedentary and active living are viewed or influenced in different ways [58], such as leisure or occupational sedentary time representing higher social status or active transport representing poverty. These unique determinants/macrolevel drivers and potential differential health impacts of sedentary behaviour require more detailed data and understanding across a wider range of countries, with a focus on disadvantaged populations and LMICs. Recent global surveillance data, though somewhat limited, indicates that self-reported sedentary time varies substantially between high- and low-income countries [59], with high-income countries reported sedentary time almost double that of low income countries (4.9 vs 2.7 h/day). Moreover, the contextual patterns in which sedentary behaviours occur also vary by indices of socioeconomic status and markers of social disadvantage. For example, in high-income countries, occupational sedentary time tends to be higher among those with higher educational attainment or income, whereas TV viewing levels are often higher among those in lower socioeconomic positions [60]. Understanding and addressing potential social and cultural inequities in the determinants, prevalence, and health impacts of different sedentary behaviours, and appropriate opportunities and strategies to intervene, is therefore an important area in need of more research.

Policy and practice implications and opportunities

From a practical perspective, policy makers should view the new WHO sedentary behaviour guidelines as complementary and reinforcing to physical activity guidelines and public health endeavours to reduce the risk of non-communicable diseases. The benefits of MVPA are well-established, and these new sedentary recommendations show that substantial health gains also exist from promoting all adults to limit high levels of sedentary time, and to replace sedentary behaviours with physical activity of any intensity. These recommendation support new opportunities for more comprehensive messages and policies to help improve health, such as “move more” and “sit less” (or limit sedentary behaviour in non-ambulatory individuals), and even without specific thresholds, such messages are intrinsically synergistic from a public health perspective.

These new sedentary behaviour recommendations should be disseminated to key audiences and across multiple settings, broadening the potential options for health promotion and non-communicable disease prevention/management initiatives. Indeed, as emphasized in the Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030 [13], there are multiple ways to be more active, multiple policy choices, settings and opportunities, and multiple benefits. The same is true of sedentary behaviour; thus, a combined emphasis on policies and initiatives to change both physical activity and sedentary behaviours is needed to help move the physical activity agenda forward, and importantly scale-up more action at the national and global level.

The synergies between physical activity and sedentary behaviour calls for both interdisciplinary and intersectoral population health action. However, this should be supported by and will require a deeper understanding of the complexity of sedentary behaviour (e.g. from measurement/operationalization, to determinants, and health impacts) and its inter-relationships with other behaviours under different contexts. These inherent complexities suggest we should be working with different fields, expertise, and constituencies beyond public health – such as urban planners, employers, educators, and the sport sector – to create more “activity-friendly” communities and social/built environments. A solutions-oriented approach, as well as a focus on different behavioural settings (e.g. neighbourhoods, schools, domestic/homes, workplaces, and transport/commuting) and creating stronger partnerships with communities, healthcare, employers, businesses, and government, transport and industry sectors, should also be emphasised [55, 61]. Most importantly, public health efforts will need to move beyond short-term implementation and impact, and more towards achieving system embeddedness, co-benefits, and translation at scale into policy and practice [62, 63]. Moreover, the appropriateness and efficacy of all such approaches and policies will need to be tested in a diversity of populations – including those from disadvantaged backgrounds or LMICs, those living with chronic diseases or disabilities, and across different cultural backgrounds.

Conclusion

The WHO 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour provide new guidance on sedentary behaviour and its interrelationships with physical activity. They provide a broader, mutually reinforcing set of behavioural targets to help improve population health. Identified evidence gaps underscore the need for further research, especially among certain sub-populations and in diverse contexts including more LMICs. An important challenge will now be to identify effective, sustainable, and scalable approaches for limiting sedentary behaviour and increasing physical activity among those who need it most, particularly more vulnerable populations. These new sedentary behaviour guidelines should provoke more targeted research in this area and be a catalyst for more system-wide policies, programs, and initiatives to help improve global health.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Grading the body and certainty of evidence.

Acknowledgements

Systematic reviews of evidence prepared for 2018 US Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services were updated thanks to additional literature searches conducted by Kyle Sprow (National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Maryland, USA). Summaries of evidence and GRADE tables were prepared by Carrie Patnode and Michelle Henninger (The Kaiser Foundation Hospitals, Center for Health Research, Portland, Oregon, USA).

Authors’ contributions

PCD led the overall development of the paper and had primary responsibility for the final manuscript. JW and FB were members of the WHO Steering Group that oversaw the guideline development process and drafted the WHO guidelines. All authors were involved in conceptualising the paper, revisions and editing. All authors reviewed and approved the paper.

Funding

The Public Health Agency of Canada and the Government of Norway provided financial support to update the WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. PCD is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia Fellowship (#1142685) and the UK Medical Research Council [MC_UU_12015/3]. ES is funded by a NHMRC of Australia Senior Research Fellowship (#1110526) and an Investigator Grant (#1194510), and PAL Technologies (Scotland) who develop equipment measuring sedentary behaviour. The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tremblay MS, Aubert S, Barnes JD, Saunders TJ, Carson V, Latimer-Cheung AE, et al. Sedentary behavior research network (SBRN) - terminology consensus project process and outcome. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0525-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauman AE, Petersen CB, Blond K, Rangul V, Hardy LL. The descriptive epidemiology of sedentary behaviour. In: Leitzmann MF, Jochem C, Schmid D, editors. Sedentary behaviour epidemiology. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. pp. 73–106. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ekelund U, Brown WJ, Steene-Johannessen J, Fagerland MW, Owen N, Powell KE, et al. Do the associations of sedentary behaviour with cardiovascular disease mortality and cancer mortality differ by physical activity level? A systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis of data from 850 060 participants. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(14):886–894. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekelund U, Steene-Johannessen J, Brown WJ, Fagerland MW, Owen N, Powell KE, et al. Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1302–1310. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ekelund U, Tarp J, Steene-Johannessen J, Hansen BH, Jefferis B, Fagerland MW, et al. Dose-response associations between accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time and all cause mortality: systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;366:l4570. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Del Pozo-Cruz J, Garcia-Hermoso A, Alfonso-Rosa RM, Alvarez-Barbosa F, Owen N, Chastin S, et al. Replacing sedentary time: meta-analysis of objective-assessment studies. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(3):395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patterson R, McNamara E, Tainio M, de Sa TH, Smith AD, Sharp SJ, et al. Sedentary behaviour and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality, and incident type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose response meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33(9):811–829. doi: 10.1007/s10654-018-0380-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UK Chief Medical Officers' Physical Activity Guidelines. Department of Health and Social Care, Llwodraeth Cymru Welsh Government, Department of Health Northern Ireland and the Scottish Government; 2019.

- 9.2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/report.aspx; 2018.

- 10.Brown WJ, Bauman AE, Bull FC, Burton NW. Development of evidence-based physical activity recommendations for adults (18-64 years). Report prepared for the Australian Government Department of Health. 2012.

- 11.Rütten A, Pfeifer K. National recommendations for physical activity and physical activity promotion. Erlangen: FAU University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weggemans RM, Backx FJG, Borghouts L, Chinapaw M, Hopman MTE, Koster A, et al. The 2017 Dutch physical activity guidelines. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s12966-018-0661-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world. https://www.who.int/ncds/prevention/physical-activity/global-action-plan-2018-2030/en/: World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland; 2018.

- 14.Bull F, Al-Ansari S, Biddle SJH, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Dempsey PC, et al. World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Brit J Sports Med. 2020. (in press). 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.World Health Organization. WHO Handbook for guideline development - 2nd ed. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/145714: World Health Organization: Geneva; 2014.

- 16.Bull F, Willumsen J. World Health Organization. Guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaput JP, Willumsen J, Bull F, Chou R, Ekelund U, Firth J, et al. 2020 WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour for children and adolescents aged 5-17 years: summary of the evidence. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020. (in press). 10.1186/s12966-020-01037-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torres A, Tennant B, Ribeiro-Lucas I, Vaux-Bjerke A, Piercy K, Bloodgood B. Umbrella and systematic review methodology to support the 2018 physical activity guidelines advisory Committee. J Phys Act Health. 2018;15(11):805–810. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2018-0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture; . 2015:436.

- 23.Ahmad S, Shanmugasegaram S, Walker KL, Prince SA. Examining sedentary time as a risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases and their markers in South Asian adults: a systematic review. International journal of public health. 2017/03/17 ed2017. p. 503–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Bailey DP, Hewson DJ, Champion RB, Sayegh SM. Sitting time and risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(3):408–416. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger FF, Leitzmann MF, Hillreiner A, Sedlmeier AM, Prokopidi-Danisch ME, Burger M, et al. Sedentary Behavior and Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Cancer Prevention Research. 2019;12(10):675–688. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-19-0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan DSM, Abar L, Cariolou M, Nanu N, Greenwood DC, Bandera EV, et al. World Cancer Research Fund international: continuous update project-systematic literature review and meta-analysis of observational cohort studies on physical activity, sedentary behavior, adiposity, and weight change and breast cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30(11):1183–1200. doi: 10.1007/s10552-019-01223-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ku PW, Steptoe A, Liao Y, Hsueh MC, Chen LJ. A cut-off of daily sedentary time and all-cause mortality in adults: a meta-regression analysis involving more than 1 million participants. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1062-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ku PW, Steptoe A, Liao Y, Hsueh MC, Chen LJ. A Threshold of Objectively-Assessed Daily Sedentary Time for All-Cause Mortality in Older Adults: A Meta-Regression of Prospective Cohort Studies. J Clin Med. 2019;8(4):564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Lee J. Physical activity, sitting time, and the risk of ovarian cancer: a brief research report employing a meta-analysis of existing. Health Care For Women International. 2019;40(4):433–458. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2018.1505892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma P, Yao Y, Sun W, Dai S, Zhou C. Daily sedentary time and its association with risk for colorectal cancer in adults: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(22):e7049. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahmood S, MacInnis RJ, English DR, Karahalios A, Lynch BM. Domain-specific physical activity and sedentary behaviour in relation to colon and rectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(6):1797–1813. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manas A, Del Pozo-Cruz B, Garcia-Garcia FJ, Guadalupe-Grau A, Ara I. Role of objectively measured sedentary behaviour in physical performance, frailty and mortality among older adults: a short systematic review. Eur J Sport Sci. 2017;17(7):940–953. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2017.1327983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shephard RJ. Physical activity in the prevention and management of bladder cancer. J Sports Medicine Physical Fitness. 2017;57(10):1359–1366. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.17.06830-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J, Huang L, Gao Y, Wang Y, Chen S, Huang J, et al. Physically active individuals have a 23% lower risk of any colorectal neoplasia and a 27% lower risk of advanced colorectal neoplasia than their non-active counterparts: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Sports Med. 2019;54(10):582–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Xu C, Furuya-Kanamori L, Liu Y, Faerch K, Aadahl M, R AS, et al. Sedentary Behavior, Physical Activity, and All-Cause Mortality: Dose-Response and Intensity Weighted Time-Use Meta-analysis. J Am Med Directors Assoc. 2019;20(10):1206–12.e3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Wang J, Huang L, Gao Y, Wang Y, Chen S, Huang J, et al. Physically active individuals have a 23% lower risk of any colorectal neoplasia and a 27% lower risk of advanced colorectal neoplasia than their non-active counterparts: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(10):582–591. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen D, Mao W, Liu T, Lin Q, Lu X, Wang Q, et al. Sedentary behavior and incident cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmid D, Leitzmann MF. Television viewing and time spent sedentary in relation to cancer risk: a meta-analysis. J National Cancer Institute. 2014;106(7):dju098. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, Bajaj RR, Silver MA, Mitchell MS, et al. Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):123–132. doi: 10.7326/M14-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmad S, Shanmugasegaram S, Walker KL, Prince SA. Examining sedentary time as a risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases and their markers in south Asian adults: a systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2017;62(4):503–515. doi: 10.1007/s00038-017-0947-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dempsey PC, Friedenreich CM, Leitzmann MF, Buman MP, Lambert E, Willumsen J, et al. Global public health guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour for people living with chronic conditions: a call to action. J Phys Act Health. 2020 (in press). 10.1186/s12966-020-01044-0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Carty C, Van der Ploeg HP, Biddle SJH, Bull F, Willumsen J, Lee L, et al. The first global physical activity and sedentary behaviour guidelines for people living with disability. J Phys Act Health. 2020 (in press). 10.1123/jpah.2020-0629. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(10):e1077–e1e86. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ussery EN, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, Katzmarzyk PT, Carlson SA. Joint prevalence of sitting time and leisure-time physical activity among US adults, 2015-2016. JAMA. 2018;320(19):2036–2038. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.17797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chastin SF, Egerton T, Leask C, Stamatakis E. Meta-analysis of the relationship between breaks in sedentary behavior and cardiometabolic health. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2015;23(9):1800–1810. doi: 10.1002/oby.21180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loh R, Stamatakis E, Folkerts D, Allgrove JE, Moir HJ. Effects of Interrupting Prolonged Sitting with Physical Activity Breaks on Blood Glucose, Insulin and Triacylglycerol Measures: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med (Auckland, NZ) 2019;50(2):295–330. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01183-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hadgraft NT, Winkler E, Climie RE, Grace MS, Romero L, Owen N, Dunstan DW, Healy G, Dempsey PC. Effects of sedentary behaviour interventions on biomarkers of cardiometabolic risk in adults: systematic review with meta-analyses. Brit J Sports Med. 2020. (in press). 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Peachey MM, Richardson J, A VT, Dal-Bello Haas V, Gravesande J. Environmental, behavioural and multicomponent interventions to reduce adults' sitting time: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2020;54(6):315–325. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Martin A, Fitzsimons C, Jepson R, Saunders DH, van der Ploeg HP, Teixeira PJ, et al. Interventions with potential to reduce sedentary time in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(16):1056–1063. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DiPietro L, Al-Ansari S, Biddle SJH, Borodulin K, Bull F, Dempsey PC, et al. Advancing the Global Physical Activity Agenda: Recommendations for Future Research by the 2020 WHO physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines development group. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2020. (in press). 10.1186/s12966-020-01042-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Pedišić Ž, Dumuid D, Olds T. Integrating sleep, sedentary behaviour, and physical activity research in the emerging field of time-use epidemiology: definitions, concepts, statistical methods, theoretical framework, and future directions. Kinesiology. 2017;49(2):10–11. doi: 10.26582/k.49.2.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chastin SF, Palarea-Albaladejo J, Dontje ML, Skelton DA. Combined effects of time spent in physical activity, sedentary behaviors and sleep on obesity and cardio-metabolic health markers: a novel compositional data analysis approach. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0139984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dumuid D, Stanford TE, Martin-Fernandez JA, Pedisic Z, Maher CA, Lewis LK, et al. Compositional data analysis for physical activity, sedentary time and sleep research. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018;27(12):3726–3738. doi: 10.1177/0962280217710835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dempsey PC, Matthews CE, Dashti SG, Doherty AR, Bergouignan A, van Roekel EH, et al. Sedentary behavior and chronic disease: mechanisms and future directions. J Phys Act Health. 2020;17(1):52–61. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2019-0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chastin SF, De Craemer M, Lien N, Bernaards C, Buck C, Oppert JM, et al. The SOS-framework (Systems of Sedentary behaviours): an international transdisciplinary consensus framework for the study of determinants, research priorities and policy on sedentary behaviour across the life course: a DEDIPAC-study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0409-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.World Health Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020. https://www.who.int/nmh/events/ncd_action_plan/en/: World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland; 2013.

- 57.United Nations . Time to deliver: third UN high-level meeting on non-communicable diseases. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Buck C, Loyen A, Foraita R, Van Cauwenberg J, De Craemer M, Mac Donncha C, et al. Factors influencing sedentary behaviour: a system based analysis using Bayesian networks within DEDIPAC. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0211546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McLaughlin M, Atkin AJ, Starr L, Hall A, Wolfenden L, Sutherland R, et al. Worldwide surveillance of self-reported sitting time: a scoping review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):111. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-01008-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O'Donoghue G, Perchoux C, Mensah K, Lakerveld J, van der Ploeg H, Bernaards C, et al. A systematic review of correlates of sedentary behaviour in adults aged 18-65 years: a socio-ecological approach. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:163. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2841-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Okely AD, Tremblay MS, Hammersley M, Aubert S. Targeting sedentary behaviour at the policy level. In: Leitzmann MF, Jochem C, Schmid D, editors. Sedentary behaviour epidemiology. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. pp. 565–594. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koorts H, Eakin E, Estabrooks P, Timperio A, Salmon J, Bauman A. Implementation and scale up of population physical activity interventions for clinical and community settings: the PRACTIS guide. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s12966-018-0678-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reis RS, Salvo D, Ogilvie D, Lambert EV, Goenka S, Brownson RC. Scaling up physical activity interventions worldwide: stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1337–1348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Grading the body and certainty of evidence.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.