Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have captured great attention in regenerative medicine for over a few decades by virtue of their differentiation capacity, potent immunomodulatory properties, and their ability to be favorably cultured and manipulated. Recent investigations implied that the pleiotropic effects of MSCs is not associated to their ability of differentiation, but rather is mediated by the secretion of soluble paracrine factors. Exosomes, nanoscale extracellular vesicles, are one of these paracrine mediators. Exosomes transfer functional cargos like miRNA and mRNA molecules, peptides, proteins, cytokines and lipids from MSCs to the recipient cells. Exosomes participate in intercellular communication events and contribute to the healing of injured or diseased tissues and organs. Studies reported that exosomes alone are responsible for the therapeutic effects of MSCs in numerous experimental models. Therefore, MSC-derived exosomes can be manipulated and applied to establish a novel cell-free therapeutic approach for treatment of a variety of diseases including heart, kidney, liver, immune and neurological diseases, and cutaneous wound healing. In comparison with their donor cells, MSC-derived exosomes offer more stable entities and diminished safety risks regarding the administration of live cells, e.g. microvasculature occlusion risk. This review discusses the exosome isolation methods invented and utilized in the clinical setting thus far and presents a summary of current information on MSC exosomes in translational medicine.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stem cell, Exosome, Extracellular vesicle, Exosome isolation, Regenerative medicine

Background

Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) are multipotent nonhematopoietic adult cells initially discovered by Alexander Friedenstein while studying the bone marrow. MSCs, possibly originated from the mesoderm, were reported to express CD73, CD90 and CD105 plasma membrane markers while not expressing CD14, CD34 and CD45 molecules [1, 2]. In addition to the bone marrow, MSCs can be isolated from other adult tissues including adipose tissue, amniotic fluid, dental pulp, placenta, umbilical cord blood, Wharton’s jelly and even the brain, kidney, liver, lung, spleen, pancreas and thymus [1, 3]. MSCs are known for their ability of differentiation, self-renewal and colony formation [4]. The unique capacity of MSCs to proliferate in vitro and differentiate into various cellular phenotypes represented a great opportunity for their recruitment as therapeutic agents to heal necrotic or apoptotic cells of the connective tissue. In fact, MSCs can differentiate into different lineages of mesenchymal origin including adipocytes, endothelial cells, cardiomyocytes, chondrocytes and osteoblasts as well as numerous nonmesenchymal lineages such as hepatocytes and neuron-like cells [5, 6]. The differentiation of MSCs into functional nonmesodermal cells casted doubt on the conventional paradigm that adult stem cells only differentiate from their corresponding germ layer [7]. While subsequent investigations attributed this cross-germ line differentiation to cell fusion events or methodology limitations [8, 9], the mechanism of tissue repair by MSCs particularly in nonmesodermal tissues remained to be unraveled.

It was originally assumed that upon in vivo injection, MSCs start to regenerate the damaged/diseased sites by travelling to the respective locations, engraftment, and subsequent differentiation into mature functional cells. However, this classic hypothesis was later challenged by findings from numerous animal and human studies performed during the last decades. To our surprise, it was demonstrated that MSCs neither engraft in large quantities nor for time spans long enough to explain the tissue replacement process [10]. According to a more contemporary hypothesis, MSCs employ alternate modes of tissue repair and affect their neighboring cells by inducing cell viability, proliferation and differentiation, decreasing cell apoptosis and fibrosis, stimulating extracellular matrix remodeling, and sometimes adjusting the local immune system responses to inhibit inflammation. These alternate strategies involve paracrine signaling between MSCs and the adjacent cells, which is facilitated by producing and releasing certain trophic factors, cytokines, chemokines and hormones, intercellular interactions facilitated by tunneling nanotubes, and secreting extracellular vesicles (EVs) like exosomes [3]. Exosomes derived from MSCs represent biological functions similar to these cells by contributing to tissue regeneration through enclosing and conveying active biomolecules such as peptides, proteins and RNA species to the diseased cells/tissues [11]. In this article, we overview current available exosome isolation methods intended for therapeutic application, and then summarize recent important achievements regarding the therapeutic implementation of MSC-derived exosomes in regenerative medicine in both experimental models and clinical trials.

Exosomes

Exosomes (30–150 nm in diameter) are classified as one of the three subpopulations of EVs. The other two subpopulations include microvesicles/shedding particles and apoptotic bodies (both larger than 100 nm). Exosomes are formed by sprouting as intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within the luminal space of late endosomes or so-called multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [12]. The ILVs are then secreted as exosomes once MVBs incorporate to the cellular membrane. Exosomes were initially detected by Rose Johnstone and colleagues in 1983 as the vesicles involved in mammalian reticulocyte differentiation and maturation [13]. Johnstone selected the term “exosome” because “the process seemed to be akin to reverse endocytosis, with internal vesicular contents released in contrast to external molecules internalized in membrane-bound structures” [14, 15]. Exosomes are constantly produced and released by numerous haematopoietic and nonhaematopoietic cell types including reticulocytes, B and T lymphocytes, platelets, mast cells, intestinal epithelial cells, dendritic cells, neoplastic cell lines, and the immune cells of the nervous system, i.e. microglia and neurons [16–18]. Accumulating knowledge has revealed that exosomes play significant role in a variety of cell-to-cell interaction pathways associated with numerous physiological and pathological functions.

According to their molecular composition and morphology, there are different populations of MVBs and thus different populations of exosomes within a cell. However, not all MVBs are destined for extracellular release. For instance, it was shown that only MVBs containing higher proportion of cholesterol could fuse with the cellular membrane of B lymphocytes and secrete exosomes [19]. More interestingly, multiple researches have shown that exosomes secreted from the apical and basolateral sides of polarized cells have different molecular compositions [20]. However, the content of exosomes partly reflects the content of their parent cells [21]. Exosomes contain a wide variety of cytoplasmic and membrane proteins including receptors, enzymes, transcription factors, extracellular matrix proteins, nucleic acids (mtDNA, ssDNA, dsDNA, mRNA and miRNA) and lipids [18]. Investigations of the exosomal protein content have revealed that some of these proteins are restricted to certain cell/tissue types, but others are common among all exosomes. While cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), integrins, tetraspanins and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) I/II proteins are common amongst all exosomes, a number of fusion and transferring proteins like Rab2, Rab7, annexins, flotillin, heat shock and cytoskeleton proteins, and MVB-generating proteins like Alix (ALG2-interacting protein X) are considered nonspecific exosomal proteins [22, 23].

Unlike proteins, exosomal lipid content is usually conserved and cell type-specific. Lipids play pivotal roles in forming and protecting exosomal structure, vesicle biogenesis and regulation of homeostasis in their target cells [24]. For instance, enhanced concentrations of lysobisphosphatidic acid in the inner phospholipid layer of MVB membrane in cooperation with Alix enable inward sprouting of MVBs and thereby exosome formation [25]. Exosomes also regulate the homeostasis of their target cells by altering their lipid composition particularly in cholesterol and sphingomyelin [25].

Methods of exosome isolation for therapeutic application

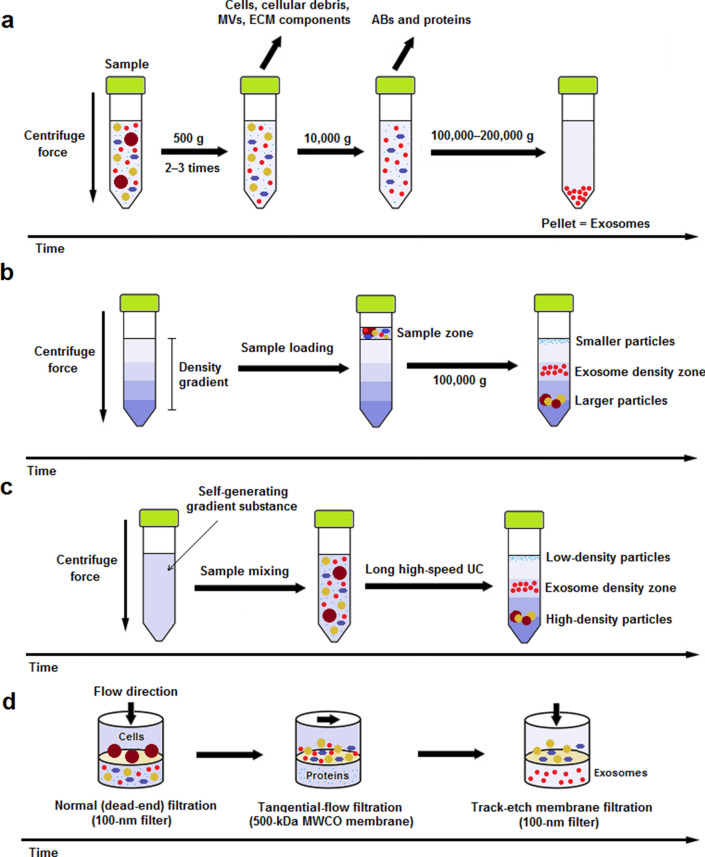

In the following section, we will discuss the two most frequently utilized methods, i.e. ultracentrifugation (UC)-based techniques and ultrafiltration (UF), for isolation of exosomes for therapeutic application. Schematic representation of the isolation methods is depicted in Fig. 1 and both methods are compared in detail in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of most frequently utilized exosome isolation methods for therapeutic purpose. a Differential ultracentrifugation (DUC): Sample is subjected to 2‒3 steps of low-speed (500 g) centrifugation to pellet out cells, microvesicles (MVs), extracellular matrix (ECM) components, and cellular debris. The supernatant is then centrifuged at 10,000 g for removal of apoptotic bodies (ABs) and contaminating proteins. Finally, exosomes are retrievd by a long (60–120 min) ultracentrifugation (UC) step at 100,000–200,000 g and subsequent washing of the pellet in PBS; b rate-zonal ultracentrifugation (RZUC): RZUC is a type of density gradient UC (DGUC) where sample is placed at the surface of a gradient density medium such as sucrose, and following a step of UC at 100,000 g, sample components migrate through the gradient density and separate according to their size and shape; c isopycnic ultracentrifugation (IPUC): IPUC is another type of DGUC that separates particles based on their density. Sample is usually mixed with a self-generating gradient substance such as CsCl, and is then subjected to a long UC step. In the end, distributed components form bands, so-called the isopycnic position, where the buoyant density of the collected particles matches with the gradient density of the surrounding solution. The banded exosomes can be retrieved from the density zone between 1.10 and 1.21 g/mL by fractionation; d sequential filtration (SF): Sample is first subjected to a 100-nm dead-end (normal) filteration process to separate cells and larger particles. Then, contaminating proteins are excluded via tangential flow filtration using a 500-kDa MWCO membrane. Lastly, the filtrate is once more passed through a track-etch membrane filter (with pore size of 100 nm) at very low pressure in order to inhibit passing of flexible nonexosomal EVs into the filtrate while allowing for passage of exosomes

Table 1.

Comparison of two most frequently utilized exosome isolation methods for clinical utility

| DUC | UF | |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of exosome separation | Physical features of exosomes (size, shape and density), the exerted centrifugal force, and the viscosity of the solvent | Particle size and MWCO of the utilized filter membrane |

| Recovery | I | H |

| Purity | H | L |

| Specificity | I | L |

| Sample volume | I | H |

| Efficiency | I | I |

| Time | H | H |

| Cost | L | I |

| Complexity | I | L |

| Functionality of exosomes | I | I |

| Scalability | I | H |

| Advanced equipment | I | L |

| References | [113–117] | [118–121] |

L low, I intermediate, H high

Recovery: exosomal yield; purity: the ability of isolating exosomes with minimum contamination; specificity: the ability to separate exosomes from nonexosomal content; sample volume: the required amount of starting material; efficiency: sample processing with high quality; time: the ability to isolate exosomes in a short amount of time; cost: the required amount of money; complexity: the need for training before use; functionality of exosomes: the use of isolated exosomes for downstream functional analysis without changing their efficacy; scalability: the ability to isolate exosomes from large sample volumes without overly increasing time, cost, or personnel required; advanced equipment: the need for expensive equipment and device

Ultracentrifugation-based techniques

When a suspension is centrifuged, its constituents will be separated on the basis of their physical features such as size, shape and density, the exerted centrifugal force, and the viscosity of the solvent. In ultracentrifugation (UC), extremely high centrifugal forces (up to 1,000,000 g) are applied to particulate components of a sample. UC methods are generally divided into analytical and preparative techniques. In the field of exosome isolation, preparative UC methods are considered the gold standard and account for approximately 56% of all methods employed by researchers [26]. In the following section, we will discuss two types of common preparative UC-based approaches for isolation of exosomes.

Differential ultracentrifugation

The successive steps of centrifugation and debris removal is referred to as differential ultracentrifugation (DUC), which is the first and still most frequent method implemented for isolation of EVs. Prior to isolation, sample is cleaned from large biocomponents and protease inhibitors are used to prevent degradation of exosomal proteins [27]. DUC consists of two to three successive low-speed (500 g) centrifugation steps to pellet out cells, microvesicles and other particles of the extracellular matrix. Further purification is then performed by 0.22 microfiltration and elimination of apoptotic bodies through centrifugation at 10,000 g. Finally, exosomes are retrieved by UC at approximately 100,000–120,000 g for 60–120 min and subsequent washing in a proper medium like phosphate buffered saline (PBS) [28]. Since the size and density of most EVs and other cellular components overlap to some extent, DUC does not yield pure exosomes, but rather results in an enrichment of exosomes. In fact, the final preparation is somewhat low in exosome recovery and often includes other particles such as serum lipoparticles [29]. If the secretory autophagy pathway is induced, lipid droplets originated from autophagosomes can also be co-isolated with exosomes [30]. The presence of large quantities of cholesteryl ester or triacylglycerol in the final preparation is defined as an index of impurity which is caused by lipoproteins or lipid droplets [31]. Therefore, it was proposed that the outcome of the 100,000 g pellet should be considered “small EVs”, not ‘exosomes’ [32]. In an attempt to increase the exosomal yield obtained by DUC, UC duration was increased to 4 h which led to serious physical damage to the exosomes, not to mention the higher contamination levels of soluble proteins [33]. DUC is laborious and time-consuming, however, it is generally applicable to large sample volumes [34], making its scalability feasible for clinical purposes [29]. Another drawback of DUC method is that its outcome is restricted by rotor capacity. Nevertheless, DUC technique requires little methodological expertise and almost no sample pretreatment [33]. Additionally, DUC is cost-effective over time and is widely utilized for isolation of exosomes in the clinical setting [35–38].

Density gradient ultracentrifugation

In density gradient ultracentrifugation (DGUC), a density gradient is usually constructed using iodoxinol, CsCl, or sucrose in a centrifuge tube before the separation takes place [39]. DGUC was reported to efficiently separate exosomes from soluble cellular components and protein aggregates, and resulted in the purest exosome recovery in comparison with DUC and precipitation-based techniques [40]. DGUC methods generally include rate-zonal ultracentrifugation and isopycnic ultracentrifugation. Several investigations have combined DGUC methods with DUC and reported that the purity of the separated exosomes were drastically improved. However, the gradient construction in this strategy was extremely time-consuming and further precaution was required to inhibit the gradient damage during acceleration and deceleration step [28]. DGUC usually leads to a relatively low exosomal yield and is not capable of discriminating different populations of EVs [32], which generally limits its application to large-scale exosome preparation for clinical purposes [41]. Nevertheless, several studies have successfully combined sucrose/deuterium oxide (D2O) DGUC with UC for isolation of exosomes for clinical use [42, 43].

Rate-zonal ultracentrifugation: In rate-zonal ultracentrifugation (RZUC), the sample is located in a thin zone at the surface of a shallow gradient density medium, which possesses a lower density than that of any of the sample particles [41]. Then the intended centrifugal force is exercised and the sample components start to travel through the gradient density, which gradually grows from the top to the bottom of the tube, and the particles are finally separated into various zones of the tube. Since the sample particles are denser than the gradient medium, RZUC separates components primarily based on their size and shape rather than by density [44]. The larger components and also the more spherically symmetrical particles migrate more rapidly through the gradient [44]. The duration of the centrifugation phase is of significant importance, and if not properly optimized, all particles will finally copellet at the bottom of the tube since they are all denser than the gradient [28]. To avoid exosome sedimentation, a high-density cushion is typically applied to layer the bottom of the centrifuge tube [41]. The capacity of RZUC is limited due to small loading region of the centrifuge tube which presents an obstacle for large-scale exosome preparations of clinical relevance [44].

Isopycnic ultracentrifugation: Isopycnic ultracentrifugation (IPUC) (also known as buoyant DUC or equilibrium DGUC) recruits the concept of buoyancy for separating particles based on their density. The sample density should be between the lowest and highest density range of the gradient [45]. In IPUC, the sample is located in a dense medium at the bottom of the gradient or uniformly mixed with a self-generating gradient substance such as CsCl [41]. Following a long high-speed centrifugation, a steep density gradient is created in the centrifuge tube [46]. As components distribute, they form bands (so-called the isopycnic position) where the buoyant density of the collected particles matches with the gradient density of the surrounding solution. The separation of exosomes into a distinct region merely depends on their density difference from all other components if a sufficient time of centrifugation is applied [41]. The banded exosomes are retrieved from the density zone between 1.10 and 1.21 g/mL by fractionation, which is performed either by removing certain amounts of fractions from the top of the tube or by draining particles with a long-needle syringe. The concentrated exosome aliquot is then subjected to a short UC at ∼100,000 g and resuspended in PBS for further analysis [41]. IPUC is a very precise technique with the ability of differentiating exosomes from other vesicles like apoptotic bodies and microvesicles as well as soluble proteins [28]. However, it is not generally applicable to clinical-scale exosome preparations [46].

Ultrafiltration

As is the case with any other conventional membrane filtration, ultrafiltration (UF) separates exosomes on the basis of their size and molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) of the utilized membrane filter. MWCO is an arbitrary unit representative of membrane pore size, which is utilized for characterizing UF membranes. UF membranes were initially used to purify biological fluids for retaining macromolecules particularly peptides and globular proteins. Since biological macromolecules are described by their molecular weight, the ability of UF membranes to retain these macromolecules is defined by their molecular weight. MWCO is described as the molecular weight where 90% of the macromolecular component is rejected by the membrane. Exosomes larger than pores of the membrane are held by it and smaller components are transited through the membrane. One major drawback of UF is the trapping and clogging of exosomes on membrane filter. Thus, they cannot be recovered for downstream analysis [39]. However, the isolation efficiency can be improved by starting the process with large MWCO membranes and then shifting to smaller ones [39]. UF is simpler and faster than UC, does not involve any special equipment, and can be easily scaled up and applied to the clinical field of exosomes [36, 47]. However, UF may sometimes result in exosomal damage because of the implemented shear force, which can be minimized through careful regulation of the pressure exerted on the membrane [33].

Sequential filtration (SF) is a UF technique used for isolation of exosomes by successive steps of filtration. First, the biosample is loaded on a 100-nm filter, which sieves out cells and large rigid cellular components and debris by dead-end (normal) filtration. Although their diameter is larger than 100 nm, different EV populations pass through this filter since they are flexible and soft [48]. The remaining contaminants like soluble proteins are then eliminated by tangential flow filtration using a 500-kDa MWCO membrane and the biosample is further concentrated. The filtrate is once more passed through a membrane filter, so-called track-etch membrane, with defined pore sizes (100 nm) at very low pressure in order to inhibit passing of flexible nonexosomal EVs into the filtrate while allowing for passage of exosomes. SF is one of the most efficient methods which is performed within a day. The process is automation-friendly and due to low manipulation forces, results in intact high-purity functional exosomes. Additionally, SF is capable of isolating exosomes from large sample volumes (up to 1 L) [34], which has been implemented in clinical trials [49].

Application of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in regenerative medicine

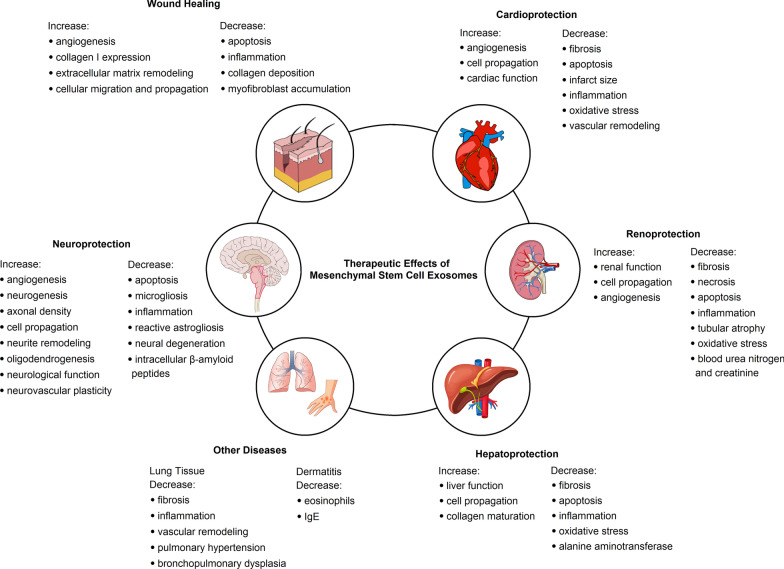

The therapeutic effects of MSC exosomes in preclinical studies are depicted in Fig. 2 and the details are summarized in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

Regenerative effects of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in different diseases in preclinical experimental models

Table 2.

Therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in different diseases in preclinical experimental models

| Condition/disease | Exosome source | Experimental model | Target mechanism(s) | Therapeutic effect(s) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular diseases | hBM-MSC | HUVEC cell | Improved proliferation, migration, and tube formation of endothelial cells in vitro | Promoted neoangiogenesis in vitro and in vivo | [50] |

| Rat MI | Improved cardiac indices, i.e. cardiac systolic/diastolic performance and blood flow | ||||

| Reduced infarct size in vivo | |||||

| mBM-MSC | Mouse HPH | Inactivated STAT3 pathway | Reduced vascular remodeling and HPH | [51] | |

| Decreased the levels of miR-17 superfamily | |||||

| Increased miR-204 levels in lung cells | |||||

| Repressed the hypoxic pulmonary influx of macrophages and the induction of MCP1 and HIMF | |||||

| rBM-MSC overexpressing CXCR4 | Neonatal CM | Upregulated IGF1α and pAkt levels, inhibited caspase 3, and promote VEGF expression and tubulogenesis in vitro | Increased angiogenesis | [52] | |

| Rat MI | Reduced infarct size | ||||

| Improved cardiac remodeling | |||||

| rBM-MSC | HUVEC cell | Enhanced tube formation by HUVEC cells | Decreased infarct size; preserved cardiac systolic and diastolic performance; enhanced the density of new functional capillary and blood flow recovery in vivo | [53] | |

| Rat MI | Compromised T cell function by impeding cell proliferation in vitro | ||||

| mBM-MSC | Mouse MI | miR-22-enriched exosomes were secreted after MI which reduced cardiomyocyte apoptosis by direct targeting of Mecp2 | Reduced infarct size and cardiac fibrosis in vivo | [55] | |

| rBM-MSC overexpressing GATA-4 | Neonatal rat CM | miR-221-enriched exosomes reduced the expression of p53 while upregulating PUMA | [56] | ||

| Expression of PUMA was greatly declined in CM cocultured with MSC | |||||

| rBM-MSC overexpressing GATA-4 | Neonatal rat CM | Increased CM survival, reduced CM apoptosis, and preserved mitochondrial membrane potential in vitro | Exosomal miR-19a could restore cardiac contractile function and decreased infarct size in vivo | [57] | |

| Rat MI | Exosomal miR-19a downregulated PTEN and triggered the Akt and ERK signaling pathways | ||||

| mBM-MSC | HUVEC cell | Enhanced the proliferation, migration and tube formation in vitro | Promoted angiogenesis and cardiac function in vivo | [58] | |

| Mouse MI | The pro-angiogenic effect of exosomes is probably associated with a miR-210-Efna3 dependent mechanism | ||||

| hEn-MSC | Neonatal CM | Overexpression and shuttling of exosomal miR-21 was attributed to suppression of PTEN, stimulation of Akt, along with Bcl-2 and VEGF upregulation | Restored cardiac function and reduced infarct size | [59] | |

| HUVEC cell | |||||

| Rat MI | |||||

| rBM-MSC | Cardiac stem cell | Triggered proliferation, migration, and angiotube formation in vitro probably mediated by a set of microRNAs | Reduced cardiac fibrosis in vivo | [60] | |

| Rat MI | Enhanced capillary density | ||||

| Restored long‐term cardiac function | |||||

| Kidney diseases | hBM-MSC | mTEC | Exosomal mRNAs encoding CDC6, CDK8 and CCNB1 influenced cell cycle entry | Improved renal function and morphology | [61] |

| Mouse AKI | Exosomal miRNAs regulated proliferative/anti-apoptotic pathways and growth factors (HGF and IGF1) that led to renal tubular cell proliferation | ||||

| hAD-MSC overexpressing GDNF | HUVEC cell | Triggered migration and angiogenesis in vitro | Reduced peritubular capillary rarefaction and renal fibrosis scores in vivo | [62] | |

| Mouse ureteral obstruction | Conferred apoptosis resistance | ||||

| Enhanced Sirtuin 1 signaling and p-eNOS levels | |||||

| hBM-MSC | Rat IRI | Enhanced TEC proliferation and survival possibly via exosomal miRNA and mRNA molecules regulating renoprotective signaling routes | [63] | ||

| Gl-MSC | Mouse IRI | Activated TEC proliferation | Ameliorated kidney function | [64] | |

| Reduced the ischemic damage post IRI | |||||

| mK-MSC | HUVEC cell | Promoted cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo | Selective engraftment in ischemic tissues and significant improvement of renal function | [65] | |

| Mouse IRI | Improved endothelial tube formation on growth factor reduced Matrigel | ||||

| Expressed pro-angiogenic mRNA molecules encoding bFGF, IGF1 and VEGF | |||||

| rAD-MSC | Rat IRI | Decreased expression of TNFα, NF-κB, IL1β, MIF, PAI1, Cox2 pro-inflammatory molecules | Reduced creatinine and BUN level, and improved renal function | [66] | |

| Reduced the levels of NOX1, NOX2, and oxidized protein | |||||

| Downregulated Smad3 and TGFβ fibrotic proteins | |||||

| Enhanced Smad1/5 and BMP2 anti-apoptotic proteins | |||||

| Upregulated CD31, vWF, and angiopoietin angiogenic biomarkers | |||||

| Enhanced mito-Cyt C levels | |||||

| rBM-MSC | Rat AKI | Enhanced IL10 levels | Decreased creatinine, urea, FENa, necrosis, apoptosis | [67] | |

| Downregulated TNFα and IL6 expression | |||||

| Increased cell proliferation | |||||

| hWJ-MSC | HUVEC cell | Repressed NOX2 and ROS | Reduced fibrosis | [68, 69] | |

| NRK-52E cell | Decreased apoptosis and sNGAL levels | Improved renal function | |||

| Rat IRI | Enhanced cell proliferation. Upregulated Nrf2/antioxidant response element and HO1 in vitro and in vivo | ||||

| hWJ-MSC | NRK-52E cell | Upregulated autophagy-related genes such as ATG5, -7, and LC3B in vitro and in vivo | Improved renal function in vivo | [70] | |

| Rat AKI | Induced mitochondrial apoptosis | ||||

| Inhibited secretion of TNFα, IL1β, and IL6 pro-inflammatory cytokines in vitro | |||||

| hWJ-MSC | NRK-52E cell | Reduced apoptosis and necrosis of proximal kidney tubules | Decreased BUN and creatinine levels | [71] | |

| Rat AKI | Decreased production of tubular protein casts through anti-oxidation and anti-apoptosis pathways in vitro and in vivo | ||||

| Promoted cell proliferation by activating the ERK1/2 pathway | |||||

| hBM-MSC | PTEC cell | Promoted cell proliferation by carrying IGF1 receptor mRNA, but not IGF1 mRNA | [72] | ||

| Liver diseases | hWJ-MSC | HL7702 cell | Suppressing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in vitro and in vivo | Reduced LF | [73] |

| Mouse LF | Inactivated the TGFβ1/SMAD2 pathway | ||||

| Alleviated hepatic inflammation and collagen deposition | |||||

| Recovered serum AST function | |||||

| Reduced collagen type I and III | |||||

| hESC-MSC | TAMH, THLE-2, and HuH-7 cells | Upregulated PCNA and Cyclin D1 cell cycle proteins and anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL gene | Recovered ALI | [74] | |

| Mouse ALI | |||||

| hCP-MSC | Rat LF | Exosomal miR-125b blocked Smo production and inactivated Hedgehog signaling mode | Reduced expansion of progenitors and regressed LF | [75] | |

| MiR‐122‐modified-hAD-MSC | Mouse LF | Exosomal miR-122 regulated the expression of IGF1R, Cyclin G1 (CCNG1) and P4HA1, which suppress HSC activation and collagen maturation | Suppressed LF development | [76] | |

| Reduced the serum levels of HA, P‐III‐P, ALT, AST and liver hydroxyproline content | |||||

| mBM-MSC | Mouse ALI | Reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines and apoptosis | Decreased the serum levels of ALT and liver necrotic areas | [77] | |

| Upregulated anti-inflammatory cytokines | |||||

| Triggered the number of Tregs | |||||

| hWJ-MSC | Mouse ALI | Exosomal GPX1 cleared H2O2 and reduced apoptosis | Treated liver failure | [78] | |

| h/mBM-MSC | Mouse LI | Exosomal Y-RNA-1 modulated cytokine expression and reduced peripheral inflammatory responses and apoptosis | Reduced hepatic injury and increased survival | [79] | |

| Neurological diseases | hBM-MSC | Mouse stroke | Enhanced angioneurogenesis | Recovered postischemic neurological injury | [80] |

| Attenuated postischemic immunosuppression (i.e., B cell, NK cell and T cell lymphopenia) in the peripheral blood | Presented long term neuroprotection. Reduced motor coordination impairment | ||||

| rBM-MSC | Rat stroke | Increased synaptophysin-positive regions in the ischemic boundary zone | Promoted neurovascular remodeling, axonal density and functional recovery | [81] | |

| Enhanced the number of newly formed doublecortin and vW | |||||

| rBM-MSC | Rat stroke | Exosomal miR-133b decreased the expression of connective tissue growth factor and ras homolog gene family member A | Resulted in neurite remodeling and stroke recovery | [82] | |

| rBM-MSC overexpressing miR-17–92 cluster | Rat stroke | Inhibited PTEN and activated the downstream proteins, protein kinase B and glycogen synthase kinase 3β | Improved neurogenesis, neurite remodeling/neuronal dendrite plasticity and oligodendrogenesis | [83] | |

| hBM-MSC | Rat BI | Attenuated inflammation-induced neuronal cellular degeneration | Improved long-lasting cognitive functions | [84] | |

| Decreased microgliosis and prevented reactive astrogliosis | |||||

| Restored short term myelination deficits and long term microstructural abnormalities of the white matter | |||||

| hBM-MSC | Ewe BI | Reduced the neurological sequelae | Promoted brain function via decreasing the total number and duration of seizures | [85] | |

| Did not affect cerebral inflammation | Preserved baroreceptor reflex sensitivity | ||||

| rBM-MSC | Rat TBI | Enhanced angiogenesis, the number of newborn immature and mature neurons, and decreased neuroinflammation | Improvement of spatial learning | [86] | |

| Recovered sensorimotor function | |||||

| rB-MSCs | Mouse TBI | Suppressed the expression of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2-associated X protein, TNFα and IL1β | Reduced the lesion size and recovering neurobehavioral performance | [87] | |

| Upregulated anti-apoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma 2 | |||||

| Modulated microglia/macrophage polarization | |||||

| rBM-MSC | Rat SCI | Regulated macrophage function by targeting M2-type macrophages in the injured sites | [88] | ||

| rBM-MSC | Rat SCI | Reduced the proportion of A1 astrocytes via blocking the nuclear translocation of the NF-κB p65 | Reduced lesion area | [89] | |

| Reduced the percentage of p65 positive nuclei in astrocytes and TUNEL-positive cells in the ventral horn | |||||

| Downregulated IL1α, IL1β and TNFα | |||||

| Increased the expression of myelin basic protein, synaptophysin and neuronal nuclei | |||||

| hBM-MSC | Rat SCI | Showed anti-inflammatory responses in the damaged tissue and disorganization of astrocytes and microglia | Improved locomotor activity | [90] | |

| mBM-MSC | Mouse AD | Normoxic MSC exosomes: Decreased plaque deposition and Aβ levels | Normoxic MSC exosomes: Recovered cognition and memory impairment | [91] | |

| Reduced the activation of astrocytes and microglia | Preconditioned MSC exosomes: Improved learning and memory capabilities | ||||

| Downregulated TNFα and IL1β and upregulated IL4 and IL10 | |||||

| Deactivated STAT3 and NF-κB | |||||

| Preconditioned MSC exosomes: Reduced plaque deposition and Aβ levels | |||||

| Upregulated growth-associated protein 43, synapsin 1, and IL10 | |||||

| Decreased the levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein, ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1, TNFα, IL1β | |||||

| Deactivated STAT3 and NF-κB | |||||

| Enhanced miR-21 levels | |||||

| hAD-MSC | Mouse N2a cell | Exosomes carried enzymatically active neprilysin and decreased both secreted and intracellular Aβ levels | [92] | ||

| hDP-MSC | ReNcell VM human neural stem cell | Rescued dopaminergic neurons from apoptosis via inducing 6-hydroxy-dopamine | [93] | ||

| Wound healing | hWJ-MSC | EA.hy926 and HFL1 cells | Triggered propagation, migration, and tube formation in vitro | Improved wound healing in vivo | [94] |

| Rat skin burn | Stimulated β-catenin nuclear translocation | ||||

| Upregulated proliferating cell nuclear antigen, cyclin D3, N-cadherin, and β-catenin | |||||

| Downregulated E-cadherin | |||||

| hWJ-MSC | Dermal fibroblast and HEK293T cell | Exosomal miR-21, ‐23a, ‐125b, and ‐145 inhibited scar formation and myofibroblast accumulation through TGFβ2/SMAD2 pathway blockade and reduction of collagen deposition in vitro and in vivo | [95] | ||

| Mouse skin-defect | |||||

| hiPSC-MSC | HUVEC cell | Upregulated angiogenesis-related biomolecules | Increased microvessel density and blood perfusion | [96] | |

| Mouse femoral artery excision | |||||

| hWJ-MSC | Rat skin burn | Upregulated collagen I, PCNA and CK19 | Resulted in rapid in vivo re-epithelialization | [97] | |

| Exosomal Wnt4 contributed to β-catenin nuclear translocation and promotion of skin cell propagation and migration | |||||

| Activated AKT pathway which reduced heat stress-induced apoptosis in vivo | |||||

| hWJ-MSC | Rat skin burn | Decreased TNFα and IL1β levels and increased IL10 levels | [98] | ||

| Exosomal miR-181c decreased inflammation via suppressing the TLR4 signaling route | |||||

| hAD-MSC | HUVEC cell | Promoted angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo | [99] | ||

| Immunodeficient mouse | Exosomal miR-125a acted as a pro-angiogenic factor by downregulating DLL4 and regulating the generation of endothelial tip cells | ||||

| hiPSC-MSC | HUVEC cell and dermal fibroblast | Promoted collagen maturity and neoangiogenesis | Enhanced re-epithelialization | [100] | |

| Rat skin wound | Triggered cell proliferation and migration in vitro | Decreased scar size | |||

| Increased type I, III collagen and elastin mRNA expression and secretion and tube formation in vitro | |||||

| hBM-MSC | Diabetic wound and normal fibroblasts | Promoted fibroblast propagation and migration | [101] | ||

| Enhanced tube formation | |||||

| Triggered Akt, ERK, and STAT3 signaling pathways | |||||

| Upregulated HGF, IGF1, NGF and SDF1 | |||||

| Other diseases | hWJ-MSC and hBM-MSC | Mouse BPD | Triggered pleiotropic effects on gene expression related with hyperoxia -induced inflammation | Relieving BPD, hyperoxia-associated inflammation, fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular remodeling in the lung tissue | [102] |

| Modulated the macrophage phenotype fulcrum, repressing the M1 state and promoting a M2-like state | |||||

| hAD-MSC | Mouse atopic dermatitis | Decreased the levels of eosinophils, IgE, CD86+ and CD206+ cells, and infiltrated mast cells | Ameliorated atopic dermatitis in vivo | [103] | |

| hBM-MSC | C2C12 and HUVEC cells | Exosomal miR-494 improved angiogenesis and myogenesis in vitro and in vivo | Resulted in muscle regeneration | [104] | |

| Mouse muscle injury | |||||

| hBM-MSC and hWJ-MSC | hPBMC | Enhanced the number of Tregs in vitro | Decreased educed the mean clinical score of EAE mice | [105] | |

| Mouse EAE | |||||

| Decreased PBMC proliferation and levels of pro-inflammatory Th1 and Th17 cytokines inclusive of IL6, IL12p70, IL17AF, and IL22 | Decreased demyelination and neuroinflammation | ||||

| Enhanced levels of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase |

Aβ amyloid β peptide, AD Alzheimer’s disease, AKI acute kidney injury, ALI acute liver injury, ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, bFGF basic fibroblast growth factor, BPD: bronchopulmonary dysplasia, BMP2 bone morphogenetic protein 2, BUN blood urea nitrogen, CM cardiomyocyte, Cox-2 cyclooxygenase 2, DLL4 angiogenic inhibitor delta-like 4, DP-MSC dental pulp-derived MSC, EAE experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, ERK extracellular-signal-regulated kinase, FENa fractional excretion of sodium, GDNF glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, Gl-MSC glomeroli MSC, GPX1 glutathione peroxidase 1, HA hyaluronic acid, hCP-MSC human chorionic plate-derived MSC, hEn-MSC human endometrium-derived MSC, hESC-MSC human emberyonic stem cell-derived MSC, HGF hepatocyte growth factor, HIMF hypoxia-inducible mitogenic factor, hiPSC-MSC human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived MSC, HO1 heme oxygenase 1, hPBMC human peripheral blood mononuclear cell, HPH hypoxic pulmonary hypertension, HSC hepatic stellate cell, HUVEC human umbilical vein endothelial cell, IGF1α insulin-like growth factor 1α, IL1β interleukin 1β, IRI ischemia reperfusion injury, LF liver fibrosis, MCP1 monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, Mecp2 methyl CpG binding protein 2, MI myocardial infarction, MIF macrophage migration inhibitor factor, mito-Cyt C mitochondrial cytochrome C, mK-MSC mouse kidney-derived MSC, mTEC murine tubular epithelial cells, NF-κB nuclear factor κB protein, NGF nerve growth factor, NOX NADPH oxidase, P4HA1 prolyl-4-hydroxylase α1, PAI-1 protein expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, PCNA proliferating cell nuclear antigen, p-eNOS phosphorylated endothelial nitric oxide synthase, P‐III‐P procollagen III‐N‐peptide, PTEC proximal tubular epithelial cell, PTEN phosphatase and tensin homolog, PUMA p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis, rAD-MSC rat adipocyte-derived MSC, rB-MSC rat bone-derived MSCs, ROS reactive oxygen specie, SCI spinal cord injury, SDF1 stromal cell-derived factor 1, sNGAL serum neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, STAT3 signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, TBI traumatic brain injury, TGFβ transforming growth factor β, TNFα tumor necrosis factor α, Treg regulatory T cell, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, vWF von Willebrand factor

Cardiovascular diseases

The cardioprotective effects of exosomes secreted from MSCs was investigated in a rat myocardial infarction (MI) model using vesicles from human bone marrow-derived MSCs (hBM-MSCs). Intramyocardial injection of exosomes was reported to improve cardiac indices such as cardiac systolic and diastolic performances and blood flow [50]. MSC exosomes were also able to exert therapeutic effects by reducing vascular remodeling and hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in mice. These outcomes were mediated by inactivation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway and upregulation of miR-204 in the lung cells [51]. Exosomes released from genetically modified rat BM-MSCs overexpressing CXCR4 (ExoCR4) were reported to enhance the levels of insulin-like growth factor 1α (IGF1α) and pAkt, inhibit caspase 3, and promote vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) upregulation and tubulogenesis in cultured cardiomyocytes. Moreover, when ExoCR4-pretreated MSC-sheet was engrafted into the damaged myocardium of a rat MI model, the infarct size remarkably decreased and angiogenesis was triggered [52]. In another study, BM-MSC exosomes promoted tube formation by endothelial cells as well as T cell inhibition, reduction of the infarct size, and recovery of cardiac systolic and diastolic performances [53, 54]. Investigation of the role of exosomal miRNA molecules demonstrated that miR-22-enriched exosomes were notably successful in decreasing the infarct size and cardiac fibrosis in a murine post-MI model via targeting MECP2 (methyl-CpG-binding protein 2) [55]. BM-MSC exosomes carrying miR-221 exhibited anti-apoptotic and cardioprotective effects by downregulating PUMA (p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis) expression in vitro [56]. Another work performed by the same team revealed that exosomal miR-19a could reduce the infarct size and restore cardiac function through downregulating phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and triggering the Akt and ERK signaling pathways in an acute MI rat model [57]. Additionally, exosomal miR-210 were shown to promote angiogenesis and retain cardiac function both ex vivo and in vivo [58]. In an attempt to explore the cardioprotective effects of endometrium-derived MSC exosomes, exosome-mediated shuttling of miR-21 was attributed to the suppression of PTEN, stimulation of Akt, and upregulation of Bcl-2 and VEGF. As a result, cardiac function was restored and the infarct size was diminished [59]. Notable results were also found by Zhang et al. when cardiac stem cells were preconditioned with BM-MSC exosomes and administered to a rat model of MI [60]. Here, cardiac fibrosis was reduced and survival and capillary density were drastically improved.

Kidney diseases

In order to investigate the renoprotective effects of BM-MSC exosomes, Bruno et al. found that exosomal mRNAs encoding CDC6, CDK8 and CCNB1 along with exosomal hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and IGF1 mediated cell cycle entry and subsequent proliferation of tubular epithelial cells while blocking apoptosis [61]. The renoprotective effects of AD-MSC exosomes overexpressing glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) was investigated on renal injury using a ureteral obstruction murine model. Here, exosomes could decrease peritubular capillary rarefaction and renal fibrosis. Moreover, they stimulated angiogenesis, cell migration, sirtuin 1 signaling pathway as well as conferring apoptosis resistance [62]. In a rat model of ischemia–reperfusion injury (IRI), BM-MSC exosome administration was associated with improved tubular epithelial cell proliferation and survival [63], most probably via exosomal miRNA and mRNA molecules mediating renoprotective signaling pathways [64]. Exosomes released form kidney-derived MSCs were also recently reported to induce angiogenesis in the renal tissue by harboring pro-angiogenic mRNA molecules encoding basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), IGF1 and VEGF [65]. In another study on a rat model of renal IRI, adipocyte-derived MSC (AD-MSC) exosomes reduced the levels of creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and improved renal function via downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and Smad3 and TGFβ fibrotic proteins as well as enhancing anti-apoptotic proteins and angiogenic biomarkers [66]. In a gentamycin-induced AKI model, administration of BM-MSC exosomes remarkably reduced inflammation by upregulating IL10 and downregulating TNFα and IL6 expression [67]. In an attempt to explore the antioxidant effects of MSC exosomes in the kidney tissue, it was revealed that exosomes derived from human Wharton’s jelly MSCs (hWJ-MSCs) could repress NADPH oxidase (NOX) and reactive oxygen species [68] while triggering Nrf2/antioxidant response element [69], which led to improved renal function and apoptosis inhibition. In a cisplatin-induced AKI model, hWJ-MSC exosomes were reported to stimulate autophagy by upregulating autophagy-related genes such as ATG5, ATG-7, and LC3B [70]. Exosomes released by hWJ-MSCs were also reported to successfully decrease BUN and creatinine levels, necrosis of proximal kidney tubules, and production of tubular protein casts through anti-oxidative and anti-apoptosis pathways [71]. Further studies have shown that when BM-MSC exosomes were co-incubated with cisplatin-injured proximal tubular epithelial cells, they were capable of promoting cell proliferation by conveying IGF1 receptor mRNA [72].

Liver diseases

Exosomes secreted by MSCs were also utilized in numerous studies for exploring their therapeutic effects in liver diseases. Transplantation of hWJ-MSC exosomes in a carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver injury (LI) murine model was shown to limit liver fibrosis (LF) and protect hepatocytes by suppressing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and inactivating the transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1)/SMAD2 pathway [73]. Hepatoprotective effects of exosomes isolated from human embryonic stem cell-derived MSCs (hESC-MSCs) were explored in an in vitro model of acetaminophen/H2O2-induced LI and a murine model of CCl4-induced acute LI, and it was revealed that these exosomes contributed to tissue regeneration through upregulating the expression of PCNA and Cyclin D1 cell cycle regulators and anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL gene [74]. In a separate study using a mouse model of CCl4-induced LF, it was revealed that exosomes released by chorionic plate-derived MSCs harbored miR-125b that demonstrated hepatoprotective effect by blocking Smo production and thus inactivating Hedgehog signaling route [75]. Furthermore, it was revealed that AD-MSC exosomes shuttle miR-122 to hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and regulate the expression of miR-122 target genes including IGF1R, Cyclin G1 (CCNG1) and prolyl-4-hydroxylase α1 (P4HA1), which affect cell proliferation and collagen maturation in HSCs [76]. The application of BM-MSC exosomes in a concanavalin A-induced LI (a case of immune-induced LI) could decrease the serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and pro-inflammatory cytokines while enhancing the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines and regulatory T cell (Treg) activity [77]. In another work, a single administration of hWJ-MSC exosomes harboring glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1), a vital human anti-oxidant, in a murine acute LI model could treat the disease via clearing hydrogen peroxide and relieving oxidative stress and cell death [78]. Exosomal Y-RNA-1 molecules were demonstrated to recover LI and increase survival by adjusting peripheral inflammatory responses and triggering anti-apoptosis effects in a lethal murine model of D-galactosamine/TNFα-induced liver failure [79].

Neurological diseases

Exosomes released from BM-MSCs were reported to exhibit therapeutic effects as they recover post-ischemic neurological injuries, enhance angioneurogenesis, and represent long-term neuroprotective functions in a murine stroke model [80]. When BM-MSC exosomes were administered intravenously to a rat stroke model, neurovascular plasticity was promoted and axonal density and synaptophysin-positive regions were improved in the ischemic margin zone of striatum and cortex [81]. Further investigations regarding BM-MSC exosomes showed that they contain miR-133b, which contributes to neurite remodeling and consequent stroke recovery upon delivery to astrocytes and neurons [82]. Additionally, it was revealed that these exosomes carry the miR-17–92 cluster, which mediates neurogenesis, neural remodeling and oligodendrogenesis in the ischemic boundary region [83]. Here, it was further demonstrated that miR-17-92 cluster-enriched exosomes have the potential of inhibiting PTEN (a confirmed target gene of miR-17-92 cluster) and consequently activating the downstream proteins, protein kinase B (mechanistic target of rapamycin) and glycogen synthase kinase 3β. In a laboratory model of inflammation-induced preterm brain injury, BM-MSC exosomes were reported to impede neural degeneration, microgliosis and inhibit reactive astrogliosis [84]. In another study, a reduction of the neurological sequelae and recovery of brain function was shown upon injection of BM-MSC exosomes [85]. While exploring the neuroprotective effects of BM-MSC exosomes in traumatic brain injury (TBI), researchers found that exosomes resulted in the promotion of angiogenesis and neuronal growth rate along with reduction of inflammation in lesion boundary zone and dentate gyrus after TBI [86]. In a separate TBI study, exosomes isolated from bone-derived MSCs (B-MSCs) exhibited neuroprotective effects by reducing the lesion size and recovering neurobehavioral performance. These outcomes were mediated by suppressing the expression of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2-associated X protein, TNFα and IL1β, upregulation of anti-apoptotic protein B-cell lymphoma 2, and modulating microglia/macrophage polarization [87]. In spinal cord injuries (SCIs), intravenously-delivered exosomes were shown to regulate macrophage functions by targeting M2-type macrophages in the injured sites [88]. Intravenous injection of BM-MSC exosomes was also reported to diminish the proportion of SCI-induced A1 astrocytes, the percentage of p65 positive nuclei in astrocytes, and the expression of IL1α, IL1β and TNFα. These mechanisms were ascribed to nuclear translocation of the NF-κB p65 [89]. Similar results were reported when systemic administration of BM-MSC exosomes showed anti-inflammatory responses in the damaged cord tissue and improved locomotor activity via disorganization of astrocytes and microglia [90]. Exosomes isolated from hypoxia-preconditioned BM-MSCs could rescue synaptic dysfunction and promote anti-inflammatory effects in an APP/PS1 murine model of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [91]. In another study of AD, it was shown that AD-MSCs secrete exosomes containing an abundance of neprilysin, the most utilized enzyme for degradation of β-amyloid peptides in the brain tissue. The levels of secreted and intracellular β-amyloid peptides were decreased when these exosomes were transferred into neuroblastoma cells [92]. In a separate study, exosomes released from dental pulp MSCs (DP-MSCs) were reported to rescue dopaminergic neurons from apoptosis via inducing 6-hydroxy-dopamine in a 3D culture [93].

Wound healing

Exosomes secreted from hWJ-MSCs contribute to wound healing process via transferring Wnt4 and activating β-catenin, which leads to angiogenesis in vivo [94]. Exosomal miRNAs including miR-21, ‐23a, ‐125b, and ‐145 from hWJ-MSCs were reported to impede scar formation and myofibroblast accumulation through TGFβ2/SMAD2 pathway blockade and reduction of collagen deposition [95]. MSC exosomes were also able to trigger the expression of angiogenesis-related biomolecules and increase microvessel density and blood perfusion in the ischemic limbs of a murine model [96]. Wounds treated with hWJ-MSC exosomes demonstrated rapid in vivo re-epithelialization as well as upregulating the expression of collagen I, PCNA and CK19. Furthermore, these exosomes harbored Wnt4 that contributed to β-catenin nuclear translocation and promotion of skin cell propagation and migration [97]. MSC exosomes were also reported to ameliorate burn-induced inflammation in cutaneous wound healing. For example, hWJ-MSC exosomes exhibited anti-inflammatory effects via reducing mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL1β and TNFα while increasing IL10 levels [98]. In another study, it was shown that AD-MSC exosomes were enriched in miR-125a that acted as a pro-angiogenic factor by downregulating the angiogenic inhibitor delta-like 4 (DLL4) expression and modulating the generation of endothelial tip cells [99]. Transplantation of exosomes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hiPSC-MSCs) to the wound sites in a rat model led to rapid re-epithelialization, promoted collagen maturity, and decreased the scar size. Additionally, these vesicles triggered cell proliferation and migration and increased the secretion of type I, III collagen and elastin in a dose-dependent manner in vitro [100]. Exosomal miR-181c contributed to the suppression of TLR4 signaling route. Here, exosomes derived from BM-MSCs could dose-dependently promote fibroblast propagation and migration, tube formation, trigger Akt, ERK, and STAT3 signaling pathways, and upregulate HGF, IGF1, nerve growth factor (NGF) and stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF1) expression [101].

Other diseases

In the lung, exosomes isolated from WJ-MSCs demonstrated remarkable therapeutic effects by relieving bronchopulmonary dysplasia, hyperoxia-associated inflammation, fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular remodeling through adjusting the phenotype of lung macrophages [102]. In a murine atopic dermatitis model, AD-MSC exosomes could decrease the levels of eosinophils, IgE, CD86+ and CD206+ cells, and the infiltrated mast cells [103]. Exosomal miR-494 contributed to muscle regeneration via improving angiogenesis and myogenesis [104]. Study of BM-MSC exosomes in an experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model of multiple sclerosis revealed that they were capable of downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and inducing Tregs [105].

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in clinical trials

Preclinical data have proven the safety of exosome therapy and scalability of their isolation methods from MSCs for clinical application. However, the use of MSC exosomes in clinical setting is limited due to the lack of established cell culture conditions and optimal protocols for production, isolation and storage of exosomes, optimal therapeutic dose and administration schedule, and reliable potency assays to evaluate the efficacy of exosome therapy [106–108]. There are numerous studies investigating the efficiency of MSC exosomes in the clinical settings. Although most of the clinical trials are in the recruitment and active phases, some of them have completed without publishing their results. Kordelas et al. tested the therapeutic effects of BM-MSCs in patients with steroid refractory graft-versus-host disease and found that the secretion of IL1β, TNFα, and IFNγ by PBMCs were remarkably reduced following the third exosome application [109]. In line with the ameliorated pro-inflammatory response of the PBMCs, the disease symptoms improved significantly shortly after the MSC exosome therapy started. In another study, Nassar et al. showed that the application of UC-MSC exosomes led to overall improvement in renal function in patients suffering from grade III-IV chronic kidney disease [110]. Here, exosome therapy resulted in remarkable improvement of plasma creatinine level, estimated glomerular filtration rate, blood urea and urinary albumin creatinine ratio. Furthermore, serum levels of IL10 and TGFβ1 were increased while serum levels of TNFα were decreased. There are also other ongoing trials performed to determine the safety and effectiveness of human MSC exosomes in treatment of tissue injuries which are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in clinical trials (https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/)

| Organ | Condition/disease | Trial ID/Ref | Phase | Status | Source of exosomes | Dose/frequency/route | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | Healthy | NCT04313647 | I | Recruiting | AD-MSC | 1× level: 2.0 × 108/3 ml | China |

| 2× level: 4.0 × 108/3 ml | |||||||

| 4× level: 8.0 × 108/3 ml | |||||||

| 6× level: 12.0 × 108/3 ml | |||||||

| 8× level: 16.0 × 108/3 ml | |||||||

| 10× level: 20.0 × 108/3 ml | |||||||

| All experiments: once; aerosol inhalation | |||||||

| SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia | NCT04276987 | I | Completed | AD-MSC | 2.0 × 108/3 ml | China | |

| Once a day during 5 days | |||||||

| Aerosol inhalation | |||||||

| NCT04491240 | I, II | Enrolling by invitation | MSC | Procedure 1: 0.5–2 × 1010/3 ml | Russia | ||

| Procedure 2: 0.5–2 × 1010/3 ml | |||||||

| All experiments: twice a day during 10 days; inhalation | |||||||

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | NCT03857841 | I | Recruiting | BM-MSC | 20 pmol phospholid/kg | ||

| 60 pmol phospholid/kg | |||||||

| 200 pmol phospholid/kg | |||||||

| All experiments: intravenous injection | |||||||

| Skin | Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa | NCT04173650 | I, II | Not yet recruiting | BM-MSC | AGLE-102 exosomes | USA |

| Once a day during 60 days | |||||||

| Applied topically to the entire body | |||||||

| Chronic ulcer | NCT04134676 | I | Completed | WJ-MSC | Conditioned medium gel | Indonesia | |

| Every week for 2 weeks | |||||||

| Applied topically to the wound | |||||||

| Brain | Acute ischemic stroke | NCT03384433 | I, II | Completed | BM-MSC | 200 µg total protein of miR-124-loaded exosomes | Iran |

| One month after attack | |||||||

| Stereotactic guidance | |||||||

| Alzheimer’s disease | NCT04388982 | I, II | Not yet recruiting | AD-MSC | Low dosage group: 5 μg exosome/1 ml | China | |

| Mild dosage group: 10 μg exosome/1 ml | |||||||

| High dosage group: 20 μg exosome/1 ml | |||||||

| All experiments: twice a week during 12 weeks; nasal drip | |||||||

| Eye | Macular holes | NCT03437759 | Early phase I | Recruiting | UC-MSC | 20–50 µg exosome/10 μl | China |

| Single dose | |||||||

| Directly injected around macular hole area | |||||||

| Dry eye | NCT04213248 | I, II | Recruiting | UC-MSC | 10 µg exosome/drop | China | |

| 4 times a day during 14 days | |||||||

| Eye drops | |||||||

| Other organs/tissues | Multiple organ failure | NCT04356300 | Not applicable | Not yet recruiting | UC-MSC | 150 mg exosome | China |

| Once a day during 14 days | |||||||

| Intravenous injection | |||||||

| Diabetes mellitus type 1 | NCT02138331 | II, III | Unknown | UC-MSC | First dose: Intravenous injection of exosomes isolated from the supernatant produced from 1.22–1.51 × 106 MSCs/kg | Egypt | |

| Second dose: 7 days after the first dose; intravenous injection of MVs isolated from the supernatant produced from the same dose of MSCs utilized in the first injection | |||||||

| Osteoarthritis | NCT04223622 | I | Not yet recruiting | AD-MSC | Osteochondral explants from arthroplasty patients treated with AD-MSC secretome (either complete conditioned medium or EVs) | Italy | |

| Graft-versus-host disease | [109] | – | Concluded | BM-MSC | 1.3–3.5 × 1010 exosome/unit; 0.5–1.6 mg/unit (The yield of an EV fraction isolated from supernatants of 4 × 107 MSCs was defined as one unit.) | Germany | |

| First dose: a tenth of a unit | |||||||

| Second dose: 2 days after the first dose, unit amounts were progressively enhanced and administered every 2–3 days until 4 doses | |||||||

| Chronic kidney disease | [110] | II, III | Concluded | UC-MSC | 100 μg of total EV protein/kg | Egypt | |

| 2 doses (1 week apart) | |||||||

| First dose: intravenous injection | |||||||

| Second dose: infused into the renal artery |

Concluding remarks

Exosomes secreted by MSCs are now being extensively exploited to develop novel regenerative strategies for numerous diseases since they convey most of the therapeutic properties of MSCs. Exosomes offer a possibility of cell-free therapy, which minimizes safety concerns regarding the administration of viable cells. In many cases, the regenerative effect of MSC exosomes has been ascribed to their anti-inflammatory function in the recipient cells. Exploiting these immunomodulatory effects allows for the use of MSC-derived exosomes to treat different inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. The function of exosomes can be readily adjusted via preconditioning of MSC culture, for instance by addition of chemical factors or cytokines, exerting hypoxic conditions, and introducing gene modifications such as the CRISPR/Cas9 technology [111]. However, details about the functional mechanisms of exosomes in MSCs and their target cells continue to be elucidated. Moreover, there are still a few unresolved concerns before bringing MSC-derived exosomes into the clinical setting. Standards and guidelines should be established for vesicle size, purity, expression of certain surface biomarkers (e.g. CD9, CD63, CD81), and acceptable contamination levels for identification and quality control of the isolated exosomes. It was confirmed that the physiological state of MSCs influence the therapeutic efficiency of isolated exosomes [108]. This issue can be partly resolved by MSC preconditioning or extracting exosomes from induced pluripotent stem cells or embryonic stem cells [112] in order to diminish the lot-to-lot variation regarding primary naive MSCs. In summary, findings from various research works imply that MSC-derived exosomes possess promising therapeutic capacity for treatment of a variety of diseases. Efforts directed toward determining standards on the therapy efficacy and safety issues will speed up clinical implementation of MSC-derived exosomes as regenerative agents.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- AD-MSC

Adipocyte-derived mesenchymal stem cell

- AKI

Acute kidney injury

- Alix

ALG2-interacting protein X

- bFGF

Basic fibroblast growth factor

- B-MSC

Bone-derived mesenchymal stem cell

- CAM

Cell adhesion molecule

- CCl4

Carbon tetrachloride

- CRISPR

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- DLL4

Delta-like 4 protein

- DGUC

Density gradient ultracentrifugation

- DP-MSC

Dental pulp-derived mesenchymal stem cell

- DUC

Differential ultracentrifugation

- EV

Extracellular vesicle

- GPX1

Glutathione peroxidase 1

- hBM-MSC

Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell

- hESC-MSC

Human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cell

- HGF

Hepatocyte growth factor

- HSC

Hepatic stellate cell

- hUC-MSC

Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cell

- hWJ-MSC

Human Wharton’s jelly (umbilical cord matrix)-derived mesenchymal stem cell

- IgE

Immunoglobulin E

- IGF1α

Insulin-like growth factor 1α

- IL1β

Interleukin 1β

- ILV

Intraluminal vesicle

- IPUC

Isopycnic ultracentrifugation

- IRI

Ischemia–reperfusion injury

- K-MSC

Kidney-derived mesenchymal stem cell

- LF

Liver fibrosis

- LI

Liver injury

- MECP2

Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2

- MHC

Major histocompatibility complex

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- MSC

Mesenchymal stem/stromal cell

- MVB

Multivesicular body

- MWCO

Molecular weight cut-off

- NADPH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- NGF

Nerve growth factor

- P4HA1

Prolyl-4-hydroxylase α1

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- PTEN

Phosphatase and tensin homolog

- PUMA

P53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis

- RBC

Red blood cell

- RZUC

Rate-zonal ultracentrifugation

- SCI

Spinal cord injury

- SDF1

Stromal cell-derived factor 1

- SF

Sequential filtration

- STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- TBI

Traumatic brain injury

- TGFβ1

Transforming growth factor β1

- TNFα

Tumor necrosis factor α

- UF

Ultrafiltration

- UC

Ultracentrifugation

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Authors’ contributions

Conception and manuscript design: RJ. Collection of data: SN, JR, NMJ and RJ. Manuscript writing: SN, JR, NMJ and RJ. Made important revisions and confirmed final revision: RJ. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sepideh Nikfarjam, Email: nikfarjams@tbzmed.ac.ir.

Jafar Rezaie, Email: Rezaie.j@umsu.ac.ir.

Naime Majidi Zolbanin, Email: majidiz.n@umsu.ac.ir.

Reza Jafari, Email: Jafari.reza@umsu.ac.ir.

References

- 1.Teixeira FG, Carvalho MM, Sousa N, Salgado AJ. Mesenchymal stem cells secretome: a new paradigm for central nervous system regeneration? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(20):3871–3882. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1290-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akbari A, Jabbari N, Sharifi R, Ahmadi M, Vahhabi A, Seyedzadeh SJ, et al. Free and hydrogel encapsulated exosome-based therapies in regenerative medicine. Life Sci. 2020;249:117447. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai RC, Yeo RW, Lim SK. Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;40:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smirnov SV, Harbacheuski R, Lewis-Antes A, Zhu H, Rameshwar P, Kotenko SV. Bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells as a target for cytomegalovirus infection: implications for hematopoiesis, self-renewal and differentiation potential. Virology. 2007;360(1):6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crapnell K, Blaesius R, Hastings A, Lennon DP, Caplan AI, Bruder SP. Growth, differentiation capacity, and function of mesenchymal stem cells expanded in serum-free medium developed via combinatorial screening. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319(10):1409–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, Henegariu O, Hwang S, Gardner R, et al. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell. 2001;105(3):369–377. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagers AJ, Weissman IL. Plasticity of adult stem cells. Cell. 2004;116(5):639–648. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prockop DJ, Oh JY. Medical therapies with adult stem/progenitor cells (MSCs): a backward journey from dramatic results in vivo to the cellular and molecular explanations. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113(5):1460–1469. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theise ND. On experimental design and discourse in plasticity research. Stem Cell Rev. 2005;1(1):9–13. doi: 10.1385/SCR:1:1:009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iso Y, Spees JL, Serrano C, Bakondi B, Pochampally R, Song YH, et al. Multipotent human stromal cells improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction in mice without long-term engraftment. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354(3):700–706. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rani S, Ryan AE, Griffin MD, Ritter T. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: toward cell-free therapeutic applications. Mol Ther. 2015;23(5):812–823. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rezaie J, Ajezi S, Avci ÇB, Karimipour M, Geranmayeh MH, Nourazarian A, et al. Exosomes and their application in biomedical field: difficulties and advantages. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(4):3372–3393. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan BT, Johnstone RM. Fate of the transferrin receptor during maturation of sheep reticulocytes in vitro: selective externalization of the receptor. Cell. 1983;33(3):967–978. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnstone RM, Adam M, Hammond J, Orr L, Turbide C. Vesicle formation during reticulocyte maturation. Association of plasma membrane activities with released vesicles (exosomes) J Biol Chem. 1987;262(19):9412–9420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnstone RM. Revisiting the road to the discovery of exosomes. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2005;34(3):214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trams EG, Lauter CJ, Salem JN, Heine U. Exfoliation of membrane ecto-enzymes in the form of micro-vesicles. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA). 1981;645(1):63–70. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(81)90512-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potolicchio I, Carven GJ, Xu X, Stipp C, Riese RJ, Stern LJ, et al. Proteomic analysis of microglia-derived exosomes: metabolic role of the aminopeptidase CD13 in neuropeptide catabolism. J Immunol. 2005;175(4):2237–2243. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Février B, Raposo G. Exosomes: endosomal-derived vesicles shipping extracellular messages. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16(4):415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Möbius W, Ohno-Iwashita Y, Donselaar EGV, Oorschot VM, Shimada Y, Fujimoto T, et al. Immunoelectron microscopic localization of cholesterol using biotinylated and non-cytolytic perfringolysin O. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50(1):43–55. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Q, Takada R, Noda C, Kobayashi S, Takada S. Different populations of Wnt-containing vesicles are individually released from polarized epithelial cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):35562. doi: 10.1038/srep35562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, Sjöstrand M, Lee JJ, Lötvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(6):654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Niel G, Porto-Carreiro I, Simoes S, Raposo G. Exosomes: a common pathway for a specialized function. J Biochem. 2006;140(1):13–21. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poliakov A, Spilman M, Dokland T, Amling CL, Mobley JA. Structural heterogeneity and protein composition of exosome-like vesicles (prostasomes) in human semen. Prostate. 2009;69(2):159–167. doi: 10.1002/pros.20860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minciacchi VR, Freeman MR, Di Vizio D. Extracellular vesicles in cancer: exosomes, microvesicles and the emerging role of large oncosomes. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;40:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mashouri L, Yousefi H, Aref AR, Ahadi AM, Molaei F, Alahari SK. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis, and mechanisms in cancer metastasis and drug resistance. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0991-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zarovni N, Corrado A, Guazzi P, Zocco D, Lari E, Radano G, et al. Integrated isolation and quantitative analysis of exosome shuttled proteins and nucleic acids using immunocapture approaches. Methods. 2015;87:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rechavi O, Erlich Y, Amram H, Flomenblit L, Karginov FV, Goldstein I, et al. Cell contact-dependent acquisition of cellular and viral nonautonomously encoded small RNAs. Genes Dev. 2009;23(16):1971–1979. doi: 10.1101/gad.1789609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doyle LM, Wang MZ. Overview of extracellular vesicles, their origin, composition, purpose, and methods for exosome isolation and analysis. Cells. 2019;8(7):727. doi: 10.3390/cells8070727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaborowski MP, Balaj L, Breakefield XO, Lai CP. Extracellular vesicles: composition, biological relevance, and methods of study. Bioscience. 2015;65(8):783–797. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biv084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hessvik NP, Øverbye A, Brech A, Torgersen ML, Jakobsen IS, Sandvig K, et al. PIKfyve inhibition increases exosome release and induces secretory autophagy. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(24):4717–4737. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2309-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skotland T, Sandvig K, Llorente A. Lipids in exosomes: current knowledge and the way forward. Prog Lipid Res. 2017;66:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kowal J, Arras G, Colombo M, Jouve M, Morath JP, Primdal-Bengtson B, et al. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(8):E968–E977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521230113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeringer E, Barta T, Li M, Vlassov AV. Strategies for isolation of exosomes. Cold Spring Harbor Protoc. 2015;2015(4):074476. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top074476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Busatto S, Vilanilam G, Ticer T, Lin WL, Dickson DW, Shapiro S, et al. Tangential flow filtration for highly efficient concentration of extracellular vesicles from large volumes of fluid. Cells. 2018;7(12):273. doi: 10.3390/cells7120273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pachler K, Lener T, Streif D, Dunai ZA, Desgeorges A, Feichtner M, et al. A Good Manufacturing Practice-grade standard protocol for exclusively human mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Cytotherapy. 2017;19(4):458–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andriolo G, Provasi E, Lo Cicero V, Brambilla A, Soncin S, Torre T, et al. Exosomes from human cardiac progenitor cells for therapeutic applications: development of a GMP-Grade Manufacturing Method. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1169. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Escudier B, Dorval T, Chaput N, André F, Caby M-P, Novault S, et al. Vaccination of metastatic melanoma patients with autologous dendritic cell (DC) derived-exosomes: results of thefirst phase I clinical trial. J Transl Med. 2005;3(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lamparski HG, Metha-Damani A, Yao JY, Patel S, Hsu DH, Ruegg C, et al. Production and characterization of clinical grade exosomes derived from dendritic cells. J Immunol Methods. 2002;270(2):211–226. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(02)00330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang M, Jin K, Gao L, Zhang Z, Li F, Zhou F, et al. Methods and technologies for exosome isolation and characterization. Small Methods. 2018;2(9):1800021. doi: 10.1002/smtd.201800021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Deun J, Mestdagh P, Sormunen R, Cocquyt V, Vermaelen K, Vandesompele J, et al. The impact of disparate isolation methods for extracellular vesicles on downstream RNA profiling. J Extracell Vesicles. 2014;3(1):24858. doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.24858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li P, Kaslan M, Lee SH, Yao J, Gao Z. Progress in exosome isolation techniques. Theranostics. 2017;7(3):789–804. doi: 10.7150/thno.18133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dai S, Wei D, Wu Z, Zhou X, Wei X, Huang H, et al. Phase I clinical trial of autologous ascites-derived exosomes combined with GM-CSF for colorectal cancer. Mol Ther. 2008;16(4):782–790. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morse MA, Garst J, Osada T, Khan S, Hobeika A, Clay TM, et al. A phase I study of dexosome immunotherapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Transl Med. 2005;3(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Serwer P. Bacteriophages: separation of. In: Wilson ID, editor. Encyclopedia of Separation Science. Oxford: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 2102–2109. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hameed BS, Bhatt CS, Nagaraj B, Suresh AK. Chapter 19—chromatography as an efficient technique for the separation of diversified nanoparticles. In: Hussain CM, editor. Nanomaterials in chromatography. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2018. pp. 503–518. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carmignac DF. Biological centrifugation. Cell Biochem Func. 2002;20(4):357. doi: 10.1002/cbf.964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Besse B, Charrier M, Lapierre V, Dansin E, Lantz O, Planchard D, et al. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes as maintenance immunotherapy after first line chemotherapy in NSCLC. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(4):e1071008. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1071008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heinemann ML, Ilmer M, Silva LP, Hawke DH, Recio A, Vorontsova MA, et al. Benchtop isolation and characterization of functional exosomes by sequential filtration. J Chromatogr A. 2014;1371:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Escudier B, Dorval T, Chaput N, André F, Caby M-P, Novault S, et al. Vaccination of metastatic melanoma patients with autologous dendritic cell (DC) derived-exosomes: results of the first phase I clinical trial. J Transl Med. 2005;3(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bian S, Zhang L, Duan L, Wang X, Min Y, Yu H. Extracellular vesicles derived from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells promote angiogenesis in a rat myocardial infarction model. J Mol Med. 2014;92(4):387–397. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]