Abstract

The expression of accessory non-structural proteins V and W in Newcastle disease virus (NDV) infections depends on RNA editing. These proteins are derived from frameshifts of the sequence coding for the P protein via co-transcriptional insertion of one or two guanines in the mRNA. However, a larger number of guanines can be inserted with lower frequencies. We analysed data from deep RNA sequencing of samples from in vitro and in vivo NDV infections to uncover the patterns of mRNA editing in NDV. The distribution of insertions is well described by a simple Markov model of polymerase stuttering, providing strong quantitative confirmation of the molecular process hypothesised by Kolakofsky and collaborators three decades ago. Our results suggest that the probability that the NDV polymerase would stutter is about 0.45 initially, and 0.3 for further subsequent insertions. The latter probability is approximately independent of the number of previous insertions, the host cell, and viral strain. However, in LaSota infections, we also observe deviations from the predicted V/W ratio of about 3:1 according to this model, which could be attributed to deviations from this stuttering model or to further mechanisms downregulating the abundance of W protein.

Keywords: polymerase stuttering, pseudo-templated transcription, deep sequencing

1. Introduction

Newcastle disease (ND) is a well-known, economically important, and prevalent poultry disease worldwide. The causative agent of ND is Newcastle disease virus (NDV), which belongs to the Orthoavulavirus genus of Avulavirinae subfamily in the Paramyxoviridae family [1]. NDV is an enveloped virus and, like any other paramyxovirus, has an approximately 15 kb long non-segmented, single-stranded, negative sense RNA genome. NDV genome encodes six essential genes expressing main structural proteins in the order of 3′-NP-P-M-F-HN-L-5′ [2], which are nucleocapsid protein (NP), phosphoprotein (P), matrix protein (M), fusion protein (F), haemagglutinin-neuraminidase protein (HN), and large RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L) [3]. Each NDV gene contains conserved transcriptional regulatory sequences known as gene start (GS) 3′-UGCCCAUCU/CU-5′ and gene end (GE) 3′-AAUU/CC/UU5-6-5′, respectively. In between two genes, there are intergenic sequences (IGSs), which span from 1 to 47 nucleotides.

NDV HN, F, and M proteins are components of the viral envelope. NDV-HN protein interacts efficiently with α-2,3 and α-2,6 N-linked sialic acid conjugates [4]. The HN protein and cell receptor tethering activate the F protein, which facilitates fusion activity for viral entry and egress [5]. Meanwhile, M protein is responsible for the translocation of viral components and virion assembly at the host cell membrane [6]. The NP is an RNA binding protein where monomers of NP proteins bind to full length genomic (−ve) and antigenomic (+ve) RNAs and form encapsidated and helical structured biologically active template for RNA transcription and replication in the host cell cytoplasm [7]. NDV P protein is an important component of viral RNA polymerase enzyme complex and essential for viral RNA synthesis [8]. NDV also expresses two non-structural accessory proteins by mRNA editing of the P gene at the preserved editing site (3′-UUUUUCC-5′). P gene uses non-template guanine residues (G), viz. +G (V) and +GG (W), during co-transcription modification, resulting in a shift of the respective open reading frame (ORF), where P, V, and W proteins share the amino-terminal, but have a distinctive carboxy-terminal. The relative approximate proportion of NDV proteins P/V/W reported for P is 60 to 70%, for V is 25 to 35%, and for W is 2 to 8.5% in NDV-infected cells [9]. The insertion of more than two G residues leading to the supplementary amino acid insertion is rare, but possible in chicken cells [9,10].

The V protein plays roles in the NDV virulence as it antagonises IFN responses. The carboxy-terminal of V protein inhibits type-I IFNs (IFN-α/β) signalling by targeting signal transducer and activator transcription factor 1 (STAT-1). The carboxy-terminal domain of V protein interacts with melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) to impede IFN-β response [11,12]; however, the function of the W protein remains unclear. NDV L protein is a central subunit of RNA polymerase complex, which controls enzymatic activities required for genomic RNA transcription into functional viral mRNA, nucleotide polymerisation, mRNA post-transcriptional modification by 5′ methyl cap and 3′ poly-A tail, as well as replication of biologically active genomic and antigenomic RNA [6]. In NDV-infected cells, P and L proteins start viral RNA synthesis at the 3’ end of genomic RNA to form leader RNA by the start and stop mechanism at each gene junction directed by GS and GE sequences [6]. The NDV genome, like other paramyxoviruses, contains multiple hexamers of nucleotides and follows ‘the rule of six’ to maintain efficient replication and transcription as the RNA is encapsidated in a helical structure by the NP protein, with each NP protein monomer spanning six nucleotides of the genome [13,14].

A unique feature of RNA editing in the P gene and the use of an alternate frame of NDV and other paramyxoviruses is known to increase the genome coding capacity of the virus efficiently [15]. The co-transcriptional RNA editing of P gene in paramyxoviruses is thought to be based on the stuttering mechanism of RNA polymerase enzyme in the ORF region in a similar fashion, where the polyadenylated tail is added to each transcript at the 3′ end of mRNA [16,17]. A model for the stuttering mechanism has been proposed by Kolakofsky and collaborators in 1990 [16,18]. The model suggested that, during transcription, the nascent chain of mRNA is weakly paired with the genomic template. When polymerase transcription complex halts at the editing site, the nascent mRNA would disassociate and realign with the template RNA, thus introducing G insertions [16].

The stuttering mechanism of co-transcriptional mRNA editing suggests that a larger number of guanines can be inserted with lower frequencies, and in fact, such insertions have been observed and are not uncommon among paramyxoviruses [19]. While these longer insertions are rare in NDV and thus unlikely to play any significant role, they are generated by the same stuttering mechanism. Hence, a more accurate study of the distribution of such insertions could provide a quantitative test of this stuttering model.

In this paper, we analyse data from deep mRNA sequencing to uncover the patterns of mRNA editing in NDV. We consider different strains from in vitro and in vivo infections: LaSota and Herts/33 infections in cultures of CEF cells, and LaSota experimental infections of Leghorn and Fayoumi chicken. We build a simple Markov model of polymerase stuttering to describe the distribution of guanine insertions and the regulation of the relative abundance of W and V, reproducing the basic features of polymerase stuttering proposed by Kolakofsky [16]. We apply this model to deep sequencing data from all samples, in order to provide a quantitative understanding of the stuttering process. We find a very good agreement, but also observe some deviations from this model, possibly related to further mechanisms affecting the regulation of the relative abundance of W and V.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets

We analysed samples from in vitro NDV infections in chicken embryo fibroblast (CEF) cells using LaSota and Herts/33 strains [20] and in vivo NDV infections from Leghorn and Fayomi chicken lines using LaSota strain [21,22,23]. These chicken lines differ in their phenotype, with Leghorn being more susceptible and Fayoumi more resistant to NDV infections. We report results on only six in vivo samples (three from Leghorn and three from Fayoumi), as they were the only ones with a reasonably high depth of viral reads at the editing site. The details of the samples are summarised in Table 1 and Table S1.

Table 1.

Summary of samples used from in vivo and in vitro experiments. NDV, Newcastle disease virus; CEF, chicken embryo fibroblast.

| Melissa Deist & Lamont Lab Group [21,22,23] | Prof Chan Ding’s Lab [20] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | Chicken Line | Sex | Phenotype | Chicken Age | Samples | Embryo Age |

| Leghorn rep 1 | Leghorn | Female | Susceptible | 21 | LaSota rep 1 | CEF cells isolated from 10-day-old SPF chicken embryos |

| Leghorn rep 2 | Leghorn | Female | Susceptible | 21 | LaSota rep 2 | |

| Leghorn rep 3 | Leghorn | Male | Susceptible | 21 | LaSota rep 3 | |

| Fayoumi rep 1 | Fayoumi | Female | Resistant | 21 | Herts/33 rep 1 | |

| Fayoumi rep 2 | Fayoumi | Female | Resistant | 21 | Herts/33 rep 2 | |

| Fayoumi rep 3 | Fayoumi | Male | Resistant | 21 | Herts/33 rep 3 | |

| Virus dose | 200 microliters 107 embryo infectious dose of 50% | Virus dose | MOI = 1 | |||

| Experiment type | in vivo | Experiment type | in vitro | |||

| Organ harvested | Trachea | Organ used for primary cells | Chicken embryo | |||

| Cell type | Epithelial cell | Cell type | Fibroblast cell | |||

| Sample type | RNA | Sample Type | RNA | |||

| Time of tissue harvest | 2 days post infection | Time of cell harvest | 12 h post infection | |||

| NDV strain | LaSota (non-pathogenic) | NDV strain | LaSota (non-pathogenic) & Herts/33 (highly pathogenic) |

|||

Cultured CEF cells were infected with LaSota or Herts/33 at a MOI of 1 and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. They were later cultured in 2% FBS containing DMEM and harvested before 12 h post infection. For in vivo studies, 21-day-old Fayoumi and Leghorn chickens were infected with 200 μL of 107 embryos infectious dose (EID) of 50% through intranasal and ocular routes, then the trachea was harvested 2 days post infection.

RNA sequencing was performed on Illumina HiSeq2500 platforms (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), with paired-end sequencing of 125 bp reads for the in vitro experiments and single-end sequencing of 100 bp reads for the in vivo ones. More details on the experimental design, preparation, and sequencing of the datasets analysed here can be found in the original publications.

It has been shown that sequencing of mRNA isolated by poly(A) selection can lead to biases in quantification of expression, because of the contribution of genomic and antigenomic RNA [24]. However, the amount of antigenomic RNA should be negligible compared with genomic RNA and mRNA, as it is used as a template for viral replication [24]. Given the strong 3′ to 5′ gradient in the expression of NDV genes, we can quantify an upper bound on the contribution of genomic RNA by comparing the expression of mRNAs coding for L (the least expressed gene, which is thus an upper bound on the amount of genomic RNA) and P. The resulting upper bound on genomic RNA contribution is 2 to 5% for the samples from in vivo infection but reaches 80 to 100% for the samples from infected CEFs (Table S2). Hence, the actual fraction of genomic RNA (which is not edited) is negligible in the former samples, but unknown in the latter samples.

2.2. Bioinformatic Analysis

As viral reference, we used the LaSota reference sequence with GenBank accession JF950510 (complete genome of NDV LaSota strain-15186 bp cRNA linear) and Herts/33 sequence AY741404 (complete genome of NDV Herts/33 strain-15186 bp RNA) for the data from in vitro experiments in [20], and LaSota sequence AF077761 (complete genome of NDV LaSota strain-15186 bp RNA) for the in vivo data from [21,22,23]. Reads were aligned to the combined transcriptome of NDV and Gallus gallus (genome build GRCg6a, gene build 2018-03) using the RNA-pipeline from the GEM aligner [25] with default parameters. We realigned all indels across all samples using LeftAlignIndels from GATK 4.0.1.2 [26] in order to assign all insertions near the RNA editing site to a single location in the genome. Reads were filtered for mapping and base quality >30 using SAMtools [27]. Variants were called using SiNPle v1.0 [28] with default parameters.

We verified manually that SAMtools mpileup assigned all insertions to positions 2284 with respect to the sequence of AF077761, and to position 2287 with respect to JF950510 and AY741404, corresponding to the base before the start and end position of the guanine homopolymeric stretch that is expanded by RNA editing. Hence, we considered all homopolymer insertions of guanines (+G) of any multiplicity at the start position for AF077761 and at the end position for JF950510 and AY741404. Finally, we considered only the samples that were covered by at least 100 reads at these positions.

To make sure that the insertions were NDV-specific and not more general artefacts of sample preparation and sequencing (e.g., stuttering of the polymerase in vivo/in vitro during the experiments or from reverse transcriptase and amplification), we performed a semi-automatic search for single-base insertions at frequencies >1% supported by at least two NDV or chicken reads, selected the ones that also included double insertions in the same position, then screened manually the resulting positions looking for insertions of homopolymeric sequences of variable length. We found such positions once every 3 to 5 kb of sequence, in both NDV and in human transcriptome; these insertions were often shared among replicates from the same experiment, but differed among experiments, even if performed by the same group. These artefacts are thus likely to depend both on the experimental protocol, on the host and on NDV strain, and possibly on the specific run of extraction and preparation; it is then unlikely that such artifacts would precisely affect the position in the NDV genome corresponding to the RNA editing process by the NDV polymerase.

2.3. Markov Model of Polymerase Stuttering

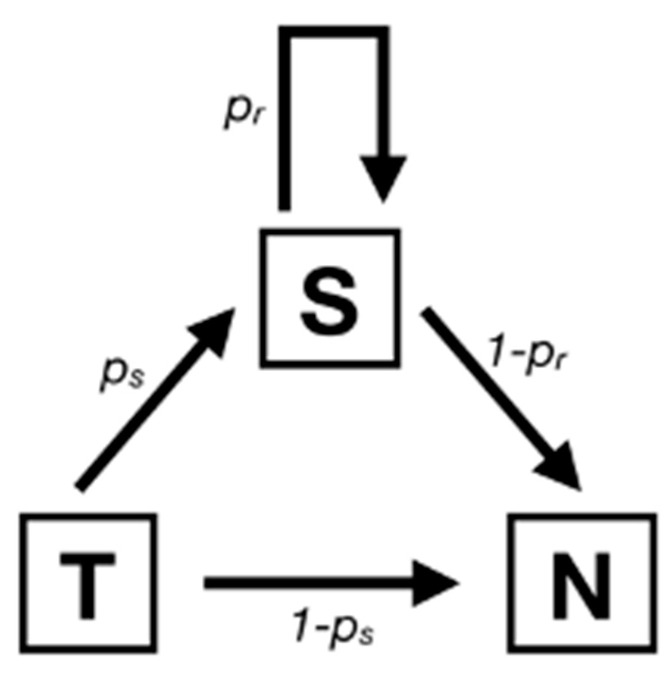

To describe the process of polymerase stuttering, we implemented a Markov model (Figure 1) with three possible states: transcribe (T), next (N), and stutter (S). In normal conditions, the polymerase would proceed from the state T where it just transcribed a base to the state N, where it would transcribe the next base. In our model, this transition happens with probability . The system goes in a stuttering state (S) with probability . This means that the same guanine base is transcribed once more, resulting in a single insertion. The polymerase can then stutter again with a different probability pr or the polymerase might move to the next base, ending up in the absorbing state N (corresponding to the transcription of the rest of the sequences) with probability 1 − pr. After the first time, the polymerase can stutter any number of times, each time with probability pr.

Figure 1.

Markov model of polymerase stuttering. In this model, three states are possible: Transcribe, Stutter, Next. The two rates in the figure can be inferred from deep sequencing data.

The probability of the polymerase not stuttering, resulting in no insertion at all, is

| (1) |

while the probability of a stutter of length l > 0 (i.e., insertion of a homopolymeric stretch of l guanines) is

| (2) |

A fraction γ of genomic RNA would change the observed distribution of the length of the insertion as

| (3) |

where δl,0 = 1 for l = 0 and 0 otherwise. This would also change the inferred fraction of V and W, by reducing both of them by a factor 1 − γ; however, their ratio is unchanged.

We consider the logarithm (in base 10) of . Our model predicts a linear dependence on for this quantity, except for = 0. The slope of the linear part is , while its intercept is , provided that the contribution from genomic RNA is negligible.

3. Results

3.1. RNA Editing and P/V/W Frequencies

The relative frequencies of P, V, and W mRNA that can be inferred from the frequencies of different insertions among the reads are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Frequencies and counts of reads that can be attributed to P, V, and W mRNA.

| Samples | P | V | W | P mRNA Count | V mRNA Count | W mRNA Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leghorn 1 | 0.5881057 | 0.3502203 | 0.0616740 | 534 | 318 | 56 |

| Leghorn 2 | 0.5895536 | 0.3096877 | 0.1007588 | 3341 | 1755 | 571 |

| Leghorn 3 | 0.6131687 | 0.3165559 | 0.0702754 | 1937 | 1000 | 222 |

| Fayoumi 1 | 0.5700246 | 0.3611794 | 0.0687961 | 464 | 294 | 56 |

| Fayoumi 2 | 0.5855513 | 0.3650190 | 0.0494297 | 154 | 96 | 13 |

| Fayoumi 3 | 0.5555556 | 0.3801170 | 0.0643275 | 95 | 65 | 11 |

| CEF Herts/33 1 | 0.7581556 | 0.1857977 | 0.0560466 | 71,789 | 17,593 | 5307 |

| CEF Herts/33 2 | 0.7703368 | 0.1770732 | 0.0525900 | 79,934 | 18,374 | 5457 |

| CEF Herts/33 3 | 0.7920412 | 0.1618567 | 0.0461021 | 75,335 | 15,395 | 4385 |

| CEF LaSota 1 | 0.9236920 | 0.0665634 | 0.0097446 | 18,484 | 1332 | 195 |

| CEF LaSota 2 | 0.9380527 | 0.0531048 | 0.0088425 | 18,883 | 1069 | 178 |

| CEF LaSota 3 | 0.9465327 | 0.0443343 | 0.0091330 | 20,624 | 966 | 199 |

The apparent fraction of P is very different among different samples (Table S3); however, because of the unknown contribution of genomic RNA to the reads from CEF cells, the quantification of P could be overestimated.

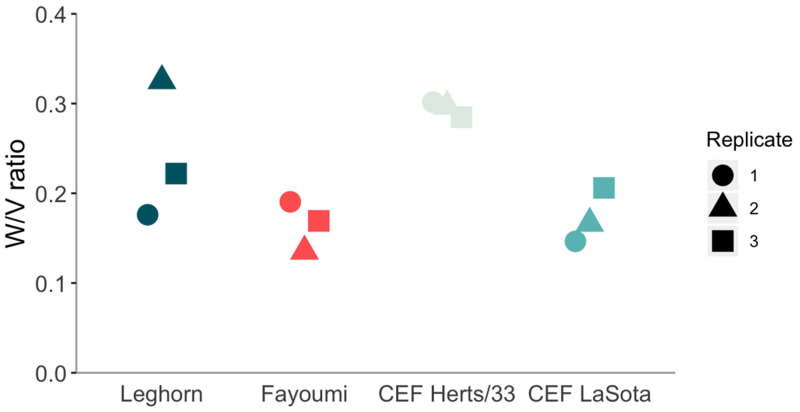

The W/V ratio is not affected by the unknown contribution from genomic RNA. The values of W/V are in the range of 0.14 to 0.33, with a mean of 0.22, median of 0.2, and SD of 0.07 (Figure 2). Values from in vivo infections are not dissimilar to the ones from in vitro infection of the same LaSota strain but differ significantly from the ones of the virulent Herts/33 strain (Table 3).

Figure 2.

W/V ratio for different datasets.

Table 3.

p-values of Student’s t-test for differences in ratio of W/V mRNA.

| p-Value | Leghorn | Fayoumi | CEF Herts/33 | CEF LaSota |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leghorn | 1.0000000 | 0.1803779 | 0.2960698 | 0.2243687 |

| Fayoumi | 0.1803779 | 1.0000000 | 0.0015257 | 0.7551445 |

| CEF Herts/33 | 0.2960698 | 0.0015257 | 1.0000000 | 0.0026214 |

| CEF LaSota | 0.2243687 | 0.7551445 | 0.0026214 | 1.0000000 |

3.2. Pattern of Polymerase Stuttering

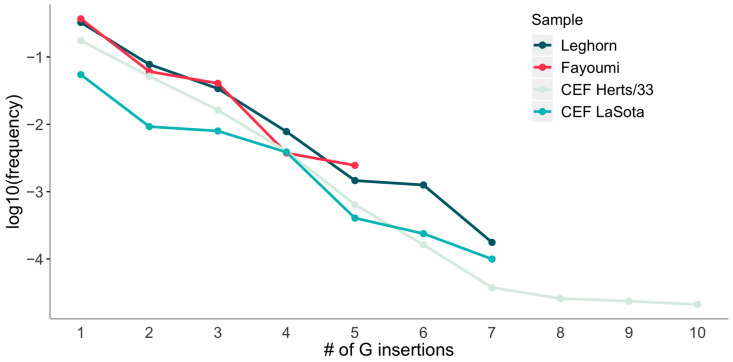

To understand what controls the P/V/W ratio, we explore the patterns of insertions of more than two guanines. Interestingly enough, for all four experiments, we observe a clear geometric decay (i.e., a linear decay in log-scale, see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Log-plot of mRNA fraction with a given length of G insertions, averaged among all samples from the same experiment.

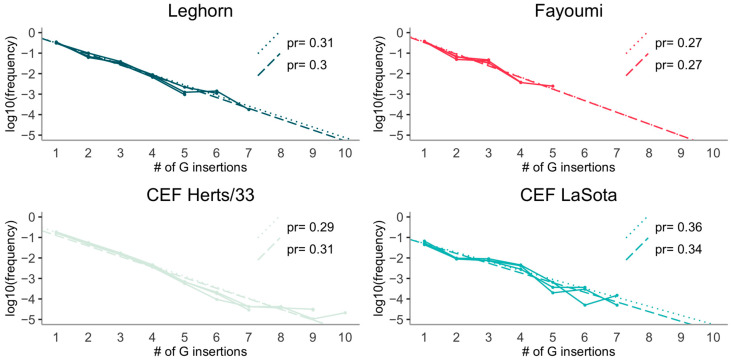

Our simple Markov model of stuttering predicts a geometric decay as well. We fit both an unweighted linear model (assuming that the measurement variance scales as the square of the frequency) and a linear model weighted according to an uncertainty on frequencies due to Poisson noise (i.e., assuming that the measurement variance between samples scales as the read count). A linear decay in log-scale fits our data very well, no matter the assumptions about the uncertainties in the frequencies (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Log-plots of mRNA fraction as a function of insertion length, presented for each sample separately. Straight lines show the linear regressions for each experiment (the dotted line corresponds to the “Poisson-weighted” regression).

It is remarkable that, fitting a linear model for each experiment (Figure 4), all coefficients provide an estimate for (i.e., a slope of about −0.5 in the log10 plot). The same is true for a joint linear fit of all experiments, allowing for different slopes. All differences in slope (and thus in ) between experiments are non-significant (Table 4).

Table 4.

Combined linear model for log10 (mRNA fraction) as a function of experiments and length of insertions, weighted by read count (corresponding to inverse variance due to Poisson noise in read sampling).

| Coefficient | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr (>|t|) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (intercept) | 0.0091800 | 0.0549286 | 0.1671257 | 0.8677600 |

| l (slope) | −0.5130190 | 0.0339636 | −15.1049786 | 0.0000000 |

| Fayoumi | 0.1106835 | 0.1650741 | 0.6705082 | 0.5047720 |

| CEF-LaSota | −0.2277560 | 0.0566429 | −4.0209119 | 0.0001460 |

| CEF-Herts/33 | −0.8588694 | 0.0722928 | −11.8804256 | 0.0000000 |

| l:Fayoumi | −0.0589679 | 0.1098642 | −0.5367340 | 0.5931778 |

| l:CEF-LaSota | −0.0224315 | 0.0350717 | −0.6395889 | 0.5245578 |

| l:CEF-Herts/33 | 0.0737953 | 0.0428570 | 1.7218949 | 0.0895690 |

It is even more remarkable that, for the in vivo samples, which contain a negligible fraction of genomic RNA, the weighted fit (Table 4) predicts a value for , i.e., larger, but not so far from (Figure S1).

These conclusions do not change if we fit an unweighted linear model (Figure 4, Table S4).

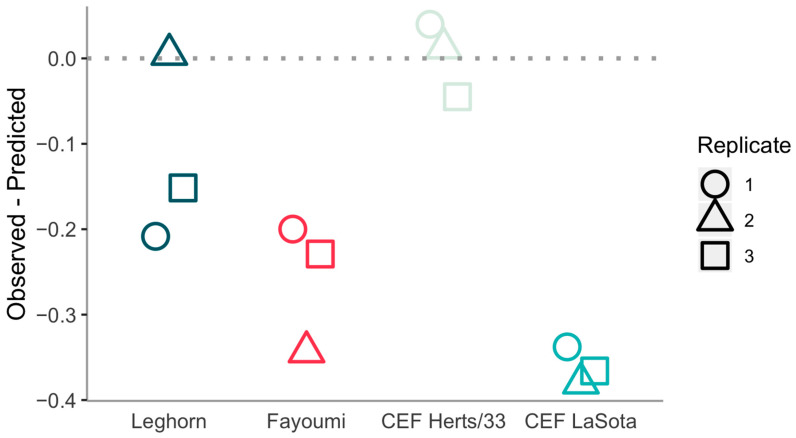

3.3. Further Suppression of W mRNA Expression

We also note a systematic deviation from the model. While double insertions +GG closely follow the trend described by the model for Herts/33 infections in CEF cells, the scenario is different for all LaSota samples. In all LaSota infections but one, +GG insertions appear to be underrepresented with respect to the predictions of the model. We reanalysed the stuttering profile ignoring +GG insertions and compare their fraction with the predicted one in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Difference between the actual log10-fraction of reads with +GG insertions and the predicted one based on our model fitted on all but +GG insertions.

This further suppression of +GG insertions significantly reduced the fraction of W mRNA in all LaSota samples (Figure 2), as +GG insertions represent the dominant source of W mRNA. As already observed, the difference is statistically significant (Table 3). The deviation is clearly attributable to double insertions, as longer insertions follow the model reasonably well without any clear trend in their deviations from it.

4. Discussion

RNA editing in paramyxoviruses is one of the most interesting examples of a functional role for pseudo-templated transcription and polymerase stuttering [29]. The evidence presented by Kolakofsky and collaborators for polymerase stuttering in NDV as the origin of V and W proteins [17,19] was very convincing. Three decades after their proposal, our work has provided strong quantitative support for their model, also revealing some unexpected relations between its parameters.

We find a value of for the probability of stuttering, which appears to be remarkably universal among all infections studied here. This would hint at a universal value for the W/V ratio, if such a ratio would be controlled purely by polymerase stuttering. However, we also observe evidence of a difference between Herts/33 and LaSota in the W/V ratio, with a lower ratio than expected for both in vivo and in vitro LaSota-infected samples, compared with the good fit of our stuttering model. This lower W/V ratio corresponds to a lower amount of mRNA with +GG insertions. Hence, the regulation of W expression is likely to be more complicated than conjectured and controlled by further mechanisms beyond simple polymerase stuttering. Based on our finding, the simplest explanations would be either a preference for +GG insertions, similarly to what happens at the first round of insertions in other paramyxoviruses [19], but only during the second stuttering event, or a hypothetical mechanism suppressing specifically the expression of mRNA with double guanine insertions.

Inference of the fraction of P mRNA from CEF cells is unfortunately unreliable because of the contribution from genomic RNA [24]; consequently, the inference of is unreliable from in vitro samples. It is, however, tempting to speculate, on the basis of evidence from the in vivo data only, that , i.e., that after the initial insertion of a guanine, further stuttering by the polymerase would be slightly inhibited. This would be consistent with suggestions that, after the first round of insertions, there could be either an inhibition of the pause needed to stutter [29], or a displacement of the strand being formed [18]. Such a scenario is likely to also occur for measles virus, where evidence could hint at [30]. If this would be the case, the two parameters would then control both the V/P ratio and the W/V ratio, but for the extra regulation discussed above. Interestingly, the opposite relation between rates () was hypothesised to explain the results of some upstream sequence modifications [31]. It should be remarked that there are large uncertainties on the value of , thus the two parameters could also have a similar value.

Our results show how RNA processes such as mRNA editing can be detected and quantified from deep sequencing data. They also illustrate the richness of information that can be extracted from massive sequencing datasets: from the regulation of the host transcriptome [20,21,22,23], to the genetic diversity of the viral population (A. Jadhav et al., in preparation), and to the RNA modifications presented here. More generally, this work illustrates the power of creative applications of modern sequencing technologies in shedding light on aspects of the molecular biology of RNA viruses.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/12/11/1249/s1, Table S1: information about samples, Table S2: L/P coverage ratio as upper bound on the contribution of genomic RNA to the reads, for each sample in our datasets, Table S3: p-values of Student’s t-test for differences in fraction of P mRNA, Table S4: combined linear model for log10(mRNA fraction) as a function of experiments and length of insertion, Figure S1: distributions of inferred values of from the weighted linear model presented in the Main Text, assuming independent Gaussian uncertainties for each term of the regression.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F.; methodology, A.L. and L.F.; formal analysis, L.Z., A.L., and L.F.; investigation, A.J. and L.F.; resources, W.L. and C.D.; data curation, A.J. and L.F.; writing—original draft preparation, L.F.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, L.Z.; supervision, V.N. and L.F.; funding acquisition, V.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) grants BBS/E/I/00007032, BBS/E/I/00007032, BBS/E/I/00007039, and BB/R007896/1 and BBSRC Newton Fund supported Joint Centre Awards on “UK-China Centre of Excellence for Research on Avian Diseases” (BBS/OS/NW/000007) and UK-India Joint Centre on Animal Technology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Amarasinghe G.K., Ayllón M.A., Bào Y., Basler C.F., Bavari S., Blasdell K.R., Briese T., Brown P.A., Bukreyev A., Balkema-Buschmann A., et al. Taxonomy of the order Mononegavirales: Update 2019. Arch. Virol. 2019;164:1967–1980. doi: 10.1007/s00705-019-04247-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganar K., Das M., Sinha S., Kumar S. Newcastle disease virus: Current status and our understanding. Virus Res. 2014;184:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagai Y., Hamaguchi M., Toyoda T. Molecular biology of Newcastle disease virus. Prog. Vet. Microbiol. Immunol. 1989;5:16–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sánchez-Felipe L., Villar E., Muñoz-Barroso I. α;2-3-And α;2-6-N-linked sialic acids allow efficient interaction of Newcastle Disease Virus with target cells. Glycoconj. J. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10719-012-9431-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choppin P.W., Compans R.W. Reproduction of Paramyxoviruses. In: Choppin P.W., Fraenkel-Conrat H., Wagner R.R., editors. Comprehensive Virology. Springer; Boston, MA, USA: 1975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamb R.A., Parks G.D. Paramyxoviridae: The viruses and their replication. Fields Virol. 2007;5:1449–1496. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fields B.N., Knipe D.M., Howley P.M. Fields Virology. Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health; Philadelphia, PA, USA: Baltimore, MD, USA: New York, NY, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamaguchi M., Yoshida T., Nishikawa K., Naruse H., Nagai Y. Transcriptive complex of Newcastle disease virus: I. Both L and P proteins are required to constitute an active complex. Virology. 1983;128:105–117. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steward M., Vipond I.B., Millar N.S., Emmerson P.T. RNA editing in Newcastle disease virus. J. Gen. Virol. 1993 doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-12-2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Locke D.P., Sellers H.S., Crawford J.M., Schultz-Cherry S., King D.J., Meinersmann R.J., Seal B.S. Newcastle disease virus phosphoprotein gene analysis and transcriptional editing in avian cells. Virus Res. 2000;69:55–68. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1702(00)00175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiu X., Fu Q., Meng C., Yu S., Zhan Y., Dong L., Song C., Sun Y., Tan L., Hu S., et al. Newcastle Disease Virus V Protein Targets Phosphorylated STAT1 to Block IFN-I Signaling. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0148560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schirrmacher V. Signaling through RIG-I and type I interferon receptor: Immune activation by Newcastle disease virus in man versus immune evasion by Ebola virus (Review) Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015;36:3–10. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolakofsky D., Pelet T., Garcin D., Hausmann S., Curran J., Roux L. Paramyxovirus RNA Synthesis and the Requirement for Hexamer Genome Length: The Rule of Six Revisited. J. Virol. 1998 doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.891-899.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calain P., Roux L. The rule of six, a basic feature for efficient replication of Sendai virus defective interfering RNA. J. Virol. 1993;67:4822–4830. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4822-4830.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolakofsky D., Vidal S., Curran J. In: Paramyxovirus RNA Synthesis and P Gene Expression BT—The Paramyxoviruses. Kingsbury D.W., editor. Springer; Boston, MA, USA: 1991. pp. 215–233. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hausmann S., Garcin D., Delenda C., Kolakofsky D. The Versatility of Paramyxovirus RNA Polymerase Stuttering. J. Virol. 1999;73:5568–5576. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5568-5576.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vidal S., Curran J., Kolakofsky D. A stuttering model for paramyxovirus P mRNA editing. EMBO J. 1990;9:2017–2022. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacques J.P., Hausmann S., Kolakofsky D. Paramyxovirus mRNA editing leads to G deletions as well as insertions. EMBO J. 1994;13:5496–5503. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06884.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolakofsky D. Paramyxovirus RNA synthesis, mRNA editing, and genome hexamer phase: A review. Virology. 2016;498:94–98. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu W., Qiu X., Song C., Sun Y., Meng C., Liao Y., Tan L., Ding Z., Liu X., Ding C. Deep Sequencing-Based Transcriptome Profiling Reveals Avian Interferon-Stimulated Genes and Provides Comprehensive Insight into Newcastle Disease Virus-Induced Host Responses. Viruses. 2018;10:162. doi: 10.3390/v10040162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J., Kaiser M.G., Deist M.S., Gallardo R.A., Bunn D.A., Kelly T.R., Dekkers J.C.M., Zhou H., Lamont S.J. Transcriptome Analysis in Spleen Reveals Differential Regulation of Response to Newcastle Disease Virus in Two Chicken Lines. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1278. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19754-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deist M.S., Gallardo R.A., Bunn D.A., Dekkers J.C.M., Zhou H., Lamont S.J. Resistant and susceptible chicken lines show distinctive responses to Newcastle disease virus infection in the lung transcriptome. BMC Genom. 2017;18:989. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4380-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deist M.S., Gallardo R.A., Bunn D.A., Kelly T.R., Dekkers J.C.M., Zhou H., Lamont S.J. Novel Mechanisms Revealed in the Trachea Transcriptome of Resistant and Susceptible Chicken Lines following Infection with Newcastle Disease Virus. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2017;24:e00027-17. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00027-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wignall-Fleming E.B., Hughes D.J., Vattipally S., Modha S., Goodbourn S., Davison A.J., Randall R.E. Analysis of Paramyxovirus Transcription and Replication by High-Throughput Sequencing. J. Virol. 2019;93:e00571-19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00571-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marco-Sola S., Sammeth M., Guigó R., Ribeca P. The GEM mapper: Fast, accurate and versatile alignment by filtration. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:1185–1188. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DePristo M.A., Banks E., Poplin R., Garimella K.V., Maguire J.R., Hartl C., Philippakis A.A., del Angel G., Rivas M.A., Hanna M., et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., Marth G., Abecasis G., Durbin R. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferretti L., Tennakoon C., Silesian A., Freimanis G., Ribeca P. SiNPle: Fast and sensitive variant calling for deep sequencing data. Genes. 2019;10:561. doi: 10.3390/genes10080561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacques J.P., Kolakofsky D. Pseudo-templated transcription in prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms. Genes Dev. 1991;5:707–713. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.5.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cox R.M., Krumm S.A., Thakkar V.D., Sohn M., Plemper R.K. The structurally disordered paramyxovirus nucleocapsid protein tail domain is a regulator of the mRNA transcription gradient. Sci. Adv. 2017;3 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hausmann S., Garcin D., Morel A.S., Kolakofsky D. Two nucleotides immediately upstream of the essential A6G3 slippery sequence modulate the pattern of G insertions during Sendai virus mRNA editing. J. Virol. 1999;73:343–351. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.1.343-351.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.