Abstract

Background:

Latino/a adolescents experience higher levels of depressive symptoms than Caucasian and African-American adolescents. Many studies found that cultural stressors contribute to this disparity, but these findings have not been integrated into a cohesive picture of the specific cultural stressors that contribute to the development of depressive symptoms for Latino/a adolescents.

Objective:

The purpose of this integrative review is to identify cultural stressors that are associated with depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents.

Design:

Procedures outlined by Ganong were used to conduct the review. The results of 33 articles that met inclusion criteria were synthesized.

Results:

Discrimination, family culture conflict, acculturative and bicultural stress, intragroup rejection, immigration stress, and context of reception were identified as cultural stressors that are associated with depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents.

Conclusions:

Clinicians should employ strategies to help Latino/a youth cope with cultural stressors and advocate for policies that support the mental health of Latino/a youth.

Keywords: Adolescent, Depression, Stress, Minorities, Cross-cultural Issues

The Latino/a population in the United States (US) nearly quintupled since the 1970s and now composes 17% of the US population (Pew Research Center, 2015). Latino/a youth currently compose 25% of all US children (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2014), and these youth suffer from significant health disparities, one of which is depressive symptoms (CDC, 2016). According to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (CDC, 2016), 35.3% of Latino/a adolescents reported experiencing depressive symptoms in 2015, measured by the percentage of youth that felt so sad or hopeless in the last two weeks that they stopped taking part in some of their daily activities; in comparison, 28.6% of Caucasian adolescents and 33.9% of African-American adolescents reported depressive symptoms. In Latino/a adolescents, depressive symptoms are associated with serious consequences, such as suicidality (CDC, 2016), substance use (Cano et al., 2015; Schwartz et al., 2015), and rule breaking behaviors (Cano et al., 2015). Due to the high prevalence and serious nature of this problem, attention to the mental health needs of Latino/a adolescents is urgent.

Recent immigration policies contributed to increased tension and negative attitudes towards the Latino/a population. Although immigrants to the US are often faced with discrimination, the process of acculturation for Latino/as has become more turbulent in the last several years. The passage of Arizona Senate Bill 1070 in 2010, for example, enacted strict immigration policies directed towards the Latino/a population (American Immigration Council, 2011). This legislation received nationwide media attention and sparked similar bills in other states, further heightening anti-immigrant attitudes towards Latino/as across the US (Androff et al., 2011; Lyons, Coursey, & Kenworthy, 2013). These attitudes cast Latinos/as as being criminals, stealing American jobs, and burdening the US economy (Androff et al., 2011). Strict immigration policies and negative societal attitudes can increase the stress that immigrants experience and put them at risk for developing health problems (Bourhis, Moise, Perreault, & Senecal, 1997).

Research on the relationship between culture and health outcomes in immigrant populations often takes two different perspectives. One field of research has examined how culture can serve as a protective factor against negative health outcomes for immigrant communities (Arrington, & Wilson, 2000). For example, Neblett, Rivas-Drake, and Umaña-Taylor (2012) found that having a strong bicultural identity is protective against depressive symptoms for Latino/a youth. Another area of research focuses on how culture can contribute to increased stress and risk of negative health outcomes for immigrants (Arrington, & Wilson, 2000). Studies guided by this perspective examine how problems such as discrimination can increase stress for immigrant youth and lead to negative mental health outcomes (Arrington, & Wilson, 2000). The current review focuses on research that explores how culture can precipitate stress for immigrant populations and lead to negative health outcomes.

Cultural stressors are negative events uniquely experienced by members of minority populations (Cano et al., 2015; Stein et al., 2012) and may be especially influential during adolescence, a stage in which identity development is a critical developmental task (Delgado, Updegraff, Roosa, & Umaña-Taylor, 2011). Many experts suggest that cultural stressors play a role in the development of depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents (Cano et al., 2015; Cervantes, Cardoso, & Goldbach, 2015; Stein, Gonzalez, & Huq, 2012). In research, these stressors have been referred to by several different terms, such as bicultural stressors (Piña-Watson, Dornhecker, & Salinas, 2015a; Schwartz et al., 2015), acculturative stressors (Forster et al., 2013), culturally-based stressors (Stein et al., 2012), and socio-cultural stressors (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2016b). However, the literature is saturated with inconsistencies in both conceptual and operational definitions of cultural stressors (Caplan, 2007).

Although the relationships between cultural stressors and depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents have been examined, no comprehensive review has been conducted to provide a cohesive picture of the specific cultural stressors that contribute to the development of depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents. Such a synthesis is important because it will help researchers and clinicians to better understand and address the high rate of depressive symptoms experienced by Latino/a adolescents. The purpose of this integrative review is to identify specific cultural stressors that are associated with the development of depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents.

Method

Integrative reviews are conducted to systematically gather, synthesize, and analyze the literature on a specific phenomenon in order to examine the support for existing hypotheses, identify gaps in the literature, and uncover common methodological and theoretical issues (Ganong, 1987). This review was guided by Ganong’s (1987) integrative review method. The steps of this method include formulating the research question, searching for relevant articles, recording the characteristics of the research, analyzing the findings, interpreting the results, and disseminating the findings.

Variables of Interest

Stress is the individual’s perception of a threat or challenge when the demands of a situation outweigh an individual’s resources, whereas a stressor is the situation that leads to the individual’s perception of stress (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Universal stressors affect populations as a whole whereas cultural stressors are unique to members of minority ethnic groups (Stein et al., 2012). Cultural stressors can vary between minority groups as what one group perceives as stressful may not be present or perceived as stressful by a different group. This integrative review will draw from Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) definition of stress and Stein et al.’s (2012) description of cultural stressors. For this review, cultural stressors are defined as stressful negative events uniquely experienced by members of the Latino/a population living in the US.

The outcome variable of this review is the rate of depressive symptoms experienced by Latino/a adolescents. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 defines Major Depressive Disorder as the experience of depressed mood or loss of pleasure for a two-week period, at least four other depressive symptoms (weight gain/loss, insomnia/hypersomnia, fatigue, psychomotor agitation/retardation, feelings of worthlessness, inability to concentrate, or recurrent thoughts of death), and significant reduction in work or social functioning (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). When individuals experience at least two of these symptoms for two or more weeks, one of which must be depressed mood or loss of pleasure, they are classified as having depressive symptoms, even if they do not fully meet the criteria for a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder (Rodríguez, Nuevo, Chatterji, & Ayuso-Mateos, 2012). Depressive symptoms, and not a clinical diagnosis of depression, is the outcome of interest for this review.

Search Strategy

The databases of PubMed, CINAHL, PsychINFO, and SocINDEX were used to search for peer-reviewed articles published between the years 2010 and 2017. The year 2010 was selected to coincide with the enactment of the Arizona Senate Bill 1070, with the assumption that cultural stressors for Latino/as living in the US likely intensified during this time. After consultation with a university librarian, the terms of “Latino/a,” “Adolescent,” “Depression,” and “Stress” were entered into the thesaurus of each database to determine the most appropriate indexed search terms to be used in each individual database. In addition to these thesaurus terms, “cultur*,” “bicultur*,” and “accultur*” were added to each database search. Three hundred and eighty-six articles were retrieved using this search strategy. An additional seven articles were added to this total after ancestry searching.

Articles were included in the review if they (1) included Latino/a adolescent participants, (2) measured depressive symptoms, (3) measured at least one cultural stressor, and (4) determined the relationship between the cultural stressor and depressive symptoms. Articles were excluded from the analysis if the authors (1) included adults over 18 or children under 12 in the sample, (2) included pregnant or parenting adolescents, or (3) conducted the study outside the US.

Articles were considered to meet inclusion criterion 3 if they measured a variable that could be considered a negative, stressful event that is uniquely experienced by US Latinos/as. For instance, general family conflict was not considered a cultural stressor because it can be experienced by any adolescent regardless of ethnicity. Family culture conflict, however, was considered a cultural stressor because it involves conflict between a parent and child concerning differences in cultural values and preferences. Similarly, level of acculturation was not considered a cultural stressor since it is a process by which individuals balance the adoption of aspects of a new culture with maintaining aspects of their heritage culture (Rogers-Sirin, Ryce, & Sirin, 2014). However, acculturation can sometimes result in challenging and threatening situations, such as being separated from family members or facing discrimination in a new country, resulting in what is known as acculturative stress (Rogers et al., 2014). For this reason, acculturative stress was considered a cultural stressor, while level of acculturation was not.

Data Collection

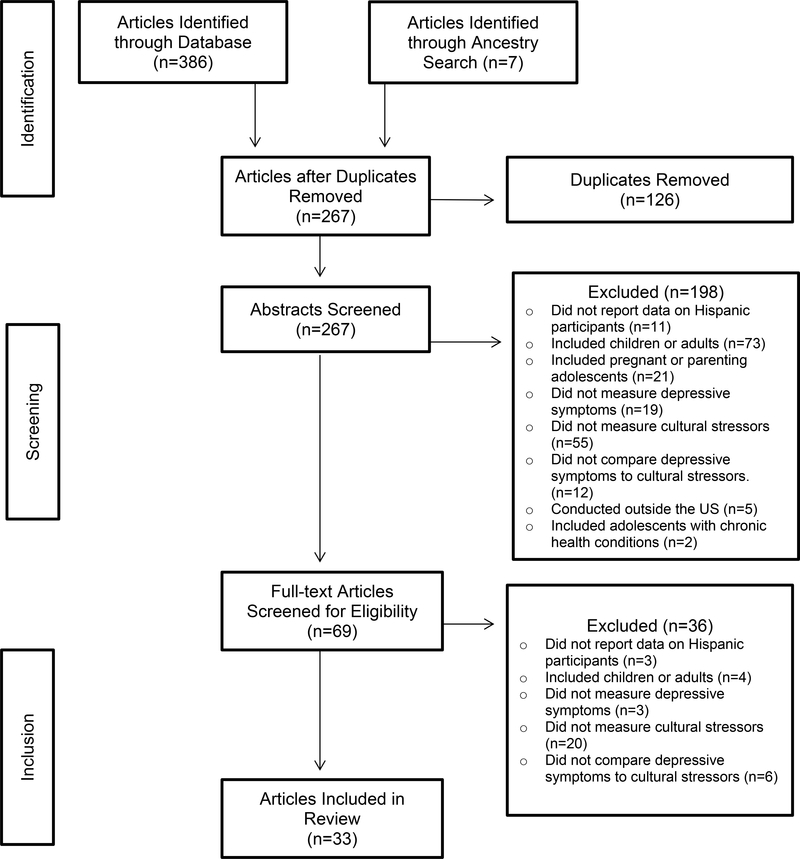

After removing 126 duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 267 articles were examined to determine if they met inclusion criteria. One hundred ninety-eight articles were eliminated after title and abstract screening, leaving 69 articles for full-text screening. Out of these 69 articles, 33 met the inclusion criteria and were included in this integrative review. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram was used to record this process and reasons for article exclusion (Figure 1). Data from these 33 articles were then extracted and organized into an evidence table (Table 1) by the first author. The second and third authors reviewed the search procedures, examined the data tables, and confirmed the review conclusions.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Diagram. This figure illustrates the search strategy employed in this integrative review (Modified from Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, & the PRISMA Group, 2009).

Table 1.

Integrative Review Evidence Table

| Source | Sample | Methods | Cultural Stressor | Depressive Symptoms | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bámaca et al. (2012) | N=271 Mother Daughter Dyads Mean Age: 12 Female: 100% Nationality: Mexico: 100% Nativity: US born: 60% |

Design: Cross Sectional Survey Setting: 4 middle and 6 high schools in Southwest US |

Family Culture Conflict: Definition: Parent-adolescent conflict was not defined. Measure: 15-item Likert scale asking respondents about general family conflict with a few items specifically related to Mexican American values. |

Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depress-ion Scale (CES-D; Radloff et al., 1991) | There was an association between parent-adolescent conflict and adolescent depressive symptoms for both early (r=0.47; p<0.001) and middle adolescents (r=0.29; p<0.001). |

| Basáñez et al. (2013) | N= 1045 Mean Age: NA Female: 54% Nationality: Mexico: 86% Nativity: US born: 89% |

Design: Longitudinal Survey Setting: 7 LA High Schools |

Discrimination: Definition: Discrimination is “a negative action towards a social group or its members on account of group membership” (p. 245). Measure: 10-item scale asking respondents to specify how often they feel they are treated poorly because of their ethnic or cultural background (Guyll, Matthews, & Bromberger, 2001) |

CES-D | Perceiving discrimination in 9th grade was associated with depressive symptoms in 11th grade (β=0.23, p<0.01). |

| Basáñez et al. (2014) | N= 2214 Mean Age: 15 Female: 54% Nationality: Mexico: 84% Nativity: US born: 85% |

Design: Longitudinal Survey Setting: 7 LA High Schools |

Intragroup Rejection:

Definition: Intragroup Rejection is “negative behaviors originating from Latino/as against other Latino/as” (p. 2). Measure: Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory (Rodriguez et al., 2002)- 4 items from the Pressure against Acculturation subscale |

CES-D | Intragroup Rejection from Latino/as in 10th grade was associated with depressive symptoms in 11th grade (β=0.14; p<0.001). |

| Behnke et al. (2011) | N= 383 Mean age: 14.6 Female: 53% Nationality: Mexico: 69% Nativity: US born: 84% |

Design: Cross-Sectional Survey Setting: 1 LA High School |

Discrimination:

Definition: Societal Discrimination was defined as “unfair treatment based on race, culture, and/ or ethnicity from various groups in society” (p. 1182). Measure: 10-item scale asking how often teens were affected by discrimination from various individuals (Whitbeck, Hoyt, McMorris, Chen, & Stubben, 2001) Family Culture Conflict: Definition: Culture conflict with parents was defined as “intense arguments with parents over cultural values” (p. 1182). Measure: Parent-Adolescent Conflict Scale (Smetana, 1988)-Items asking adolescents to report how intense the disagreements with their mothers and fathers were regarding cultural traditions. |

CES-D | ·Discrimination associated with depressive symptoms for girls (r=0.3; p<0.05) and boys (r=0.24; p<0.05). ·Culture conflict with father associated with depressive symptoms in boys (r=0.21; p<0.05) and girls (r=0.25; p<0.05). ·Culture conflict with mother associated with depressive symptoms in boys (r=0.27; p<0.05) and girls (r=0.15; p<0.05). |

| Cano et al. (2015) | N= 302 Mean age: 14.5 Female: 47% Nationality: Miami: Cuba: 61% LA: Mexico: 70% Nativity: US born: 0% |

Design: Longitudinal Survey Setting: From mental health treatment and school settings in LA, Miami, El Paso, and Lawrence |

Discrimination:

Definition: Perceived Ethnic Discrimination defined as “negative attitudes, beliefs, and differential treatment toward members of minority ethnic groups” (p.32). Measure: 7-item scale assessing being called names, followed around stores, and viewed with suspicion (Phinney, Madden, & Santos, 1998) Context of Reception: Definition: Perceived context of reception is “the perception that the host culture is unwelcoming and hostile” (p. 32). Measure: 6-item scale assessing the perception of the degree to which the opportunity structure of society does not favor one’s ethnic group Bicultural Stress: Definition: Bicultural stress was defined as “perceived pressures emanating from interactions with both the heritage and receiving cultural communities” (p. 32). Measure: Bicultural Stress Scale (BSS; Romero & Roberts, 2003) |

CES-D | ·Perceived ethnic discrimination (r=0.3; p<0.01), context of reception (r=0.25; p<0.01), and bicultural stress (r=0.45; p<0.01) were significantly associated with depressive symptoms. |

| Cervantes et al. (2015) | N= 1187 Mean age: 14.9 Female: 45% Nationality: Mexico: 47% Nativity: US born: 84% |

Design: Two-group Cross Sectional Survey Setting: LA, Miami, El Paso, and Lawrence |

Discrimination:

Definition: Discrimination stress was not defined. Measure: The Hispanic Stress Inventory-Adolescent Version (HSI-AV; Cervantes et al., 2012) Discrimination Stress Subscale Family Culture Conflict: Definition: Acculturation gap stress was not defined. Measure: HSI-AV Acculturation Gap Subscale Immigration Stress: Definition: Immigration stress was not defined. Measure: HSI-AV Immigration Stress Subscale |

Children’s Depression Inventory-2 (CDI-2; Kovacs & Multi-Health Systems Staff, 2011) | Discrimination stress (β=1; p<0.001), acculturation gap stress (β=0.48; p<0.001), and immigration stress (β=0.34; p<0.001), were associated with depressive symptoms. |

| Cervantes et al. (2012) | N= 992 Mean Age: 14.8 Female: 56% Nationality: Mexico: 47% Nativity: US born: 85% |

Design: Cross Sectional Survey Setting: LA, Miami, El Paso, and Boston |

Discrimination:

Definition: Discrimination stress was not defined. Measure: HSI-AV Discrimination Stress Subscale Family Culture Conflict: Definition: Acculturation gap stress was not defined. Measure: HSI-AV Acculturation Gap Subscale Immigration Stress: Definition: Immigration stress was not defined. Measure: HSI-AV Immigration Stress Subscale |

CDI-2 | Discrimination stress (r=0.36; p<0.001), acculturation gap stress (r=0.4; p<0.001), and immigration stress (r=0.15; p<0.001) were associated with depressive symptoms. |

| Chithambo et al. (2014) | N= 395 Mean age: 15.3 Female: 51% Nationality: Mexico: 48% Nativity: US born: 78% |

Design: Cross Sectional Survey Setting: 1 LA High School |

Discrimination:

Definition: Perceived discrimination defined as “a process by which dominant groups attempt to maintain their status within the social hierarchy” (p. 54). Measure: Everyday Discrimination Scale (Essed, 1991) |

CES-D | Perceived discrimination was associated with depression (r=0.44; p<0.05). |

| Davis et al. (2016) | N= 302 Mean age: 14.5 Female: 47% Nationality: Miami Cuba: 61% LA Mexico: 70% Nativity: US born: 0% |

Design: Longitudinal Survey Setting: 13 Schools in LA and 10 schools in Miami |

Discrimination: Definition: “Perceived ethnic discrimination can be defined as occurring when an individual believes that s/he has experienced unfair treatment by others based on her/his ethnic background” (p. 458). Measure: 7-item scale referring to being called names, followed around stores, and viewed with suspicion (Phinney et al., 1998). |

CES-D | Discrimination was associated with depressive symptoms at all three time points (T1: r=0.3; p<0.001; T2: r=0.29; p<0.001; T3: r=0.23; p<0.001). |

| Delgado et al. (2011) | N= 246 Mean age: 14.25 Female: 50% Nationality: Mexico: 100% Nativity: US born: 0% |

Design: Cross Sectional Survey Setting: 2 middle and 1 high school in Southeast US |

Discrimination: Definition: Perceived discrimination was not defined. Measure: 4 items from the Adolescents’ Experiences with Racism Scale to assess discrimination from peers in school |

CES-D | Discrimination was associated with depressive symptoms for younger (r=0.41; p<0.001) and older adolescents (r=0.32; p<0.001). |

| Forster et al. (2013) | N= 1167 Mean age: 14 Female: 54% Nationality: Mexico: 84% Nativity: US born: 89% |

Design: Longitudinal Survey Setting: 7 LA High Schools |

Acculturative Stress:

Definition: Acculturative Stress is “stress that occurs as a result of the acculturation process” (p. 2). Measure: Modified version of the Acculturative Stress Scale (Gil et al., 2000) |

CES-D | Acculturative stress in 9th grade was associated with depressive symptoms in 10th grade (β=0.11, p<0.001). |

| Gonzales-Baken (2017) | N=338 Mean age: 7th grade: 12.3 10th grade: 15.2 Female: 100% Nationality: Mexico: 100% Nativity: 7th-US: 64% 10th-US: 61% |

Design: Cross sectional survey Setting: 4 middle and high schools in the Southwest US |

Discrimination Definition: Perceived discrimination was not defined. Measure: Perceived Discrimination Scale (Whitbeck et al., 2001) |

CES-D | Perceived discrimination was associated with depressive symptoms (r=0.38, p<0.001). |

| Huq et al. (2016) | N= 172 Mean age: 14 Female: 53% Nationality: Mexico: 78% Nativity: NA |

Design: Cross Sectional Survey Setting: 2 middle and 1 high school in Southeast US |

Discrimination:

Definition: Racial/Ethnic Discrimination was not conceptually defined. Measure: Adult and Peer Discrimination Scale (Way, 1997) Family Culture Conflict: Definition: Parent-adolescent acculturation conflict is defined as “conflict that explicitly relates to differences in cultural values between parents and their children due to differential acculturation” (p. 1). Measure: 4 items from the BSS |

Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (Angold et al., 1987) | Acculturation conflict (r=0.25, p<0.01) and discrimination (r=0.24, p<0.01) were associated with depressive symptoms. |

| Huynh (2012) | N= 360 Mean age: 17 Female: 57% Nationality: Mexico: 95% Nativity: NA |

Design: Cross Sectional Survey Setting: 2 LA High Schools |

Discrimination:

Definition: Ethnic microaggressions are ‘brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, and environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults to the target person or group” (p. 831). Measure: Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (Huynh, 2012) |

CES-D | Frequency of microaggressions was associated with depressive symptoms (r=0.24, p<0.001). |

| Li, Y. (2014) | N= 2676 Mean age: 14.2 Female: 51% Nationality: Cuba: 41% Mexico: 25% Nativity: US born: 57% |

Design: Longitudinal Survey Setting: Miami, San Diego |

Family Culture Conflict:

Definition: Intergenerational conflict is “a result of adolescents’ new perceptions of autonomy, family rules, and parental authority as they enter puberty” (p. 81). Measure: The Intergenerational Conflict Scale (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001) |

CES-D | Intergenerational conflict was associated with depressive symptoms (β=0.44, p<0.001). |

| Lo et al. (2017) | N= 2185 (38.8% Hispanic) Mean age: 14.1 Female: 57% Nationality: NA Nativity: NA |

Design: Longitudinal survey Setting: Miami, San Diego |

Discrimination:

Definition: Discrimination was not defined. Measure: One item assessing the presence or absence of discrimination, and one item assessing the belief that racial/ethnic discrimination would continue despite level of education obtained |

CES-D | Perceived discrimination in education at time 2 was associated with depression at time 2 (b=0.394, p<0.01). |

| Lopez et al. (2016) | N= 2931 Mean age: 14.2 Female: 50% Nationality: Cuba: 41% Mexico: 25% Nativity: US born: 53% |

Design: Longitudinal Survey Setting: Miami, San Diego |

Discrimination:

Definition: Discrimination was not defined. Measure: Two questions asking “Have you ever felt discriminated against?” (y/n) and “By whom?” (teachers, students, counselors, White Americans in general) Intragroup Rejection: Definition: Intra or Co-ethnic Discrimination is defined as “discrimination from one’s own racial or ethnic minority group” (p. 132). Measure: Two questions asking “Have you ever felt discriminated against?” (y/n) and “By whom?” (Cubans or Latinos in general) |

CES-D | Discrimination from teachers (β=0.06, p<0.05), students (β=0.05, p<0.05), Cubans (β=0.19, p<0.001), and Latinas/os (β=0.19, p<0.001) were positively associated with depressive symptoms. |

| Lorenzo-Blanco et al. (2015) | N= 1919 Mean age= 14 Female= 52% Nationality: Mexico: 84% Nativity: US born: 87% |

Design: Longitudinal Survey Setting: 7 LA High Schools |

Discrimination:

Definition: Everyday Discrimination is “perceived daily experiences of unfair, differential treatment” (p. 1985). Measure: 10-item scale assessing frequency of perceived experiences with everyday discrimination (Guyll et al., 2001) Acculturative Stress: Definition: Acculturative Stress is “stress that results from the acculturation process” (p. 1986). Measure: 3-item scale about frequency with experiences with acculturative stress (Gil et al., 2000) |

CES-D | Discrimination at T1 associated with depressive symptoms at T1 (r=0.34, p<0.001) and T3 (r=0.16, p<0.001). Acculturative stress at T1 associated with depressive symptoms at T1 (r=0.25, p<0.001) and 3 (r=0.13, p<0.001). |

| Lorenzo-Blanco et al. (2011) | N= 1124 Mean age: 14 Female: 54% Nationality: Mexico: 86% Nativity: US born: 86% |

Design: Longitudinal Survey Setting: 7 LA High Schools |

Discrimination:

Definition: Perceived Discrimination is “perceived daily experiences of unfair, differential treatment” (p. 3) Measure: Ten item scale assessing frequency of perceived experiences with ethnic discrimination (Guyll et al., 2001) |

CES-D | Perceived discrimination was associated with depressive symptoms (r=0.22, p<0.001). |

| Lorenzo-Blanco et al. (2016a) | N= 293 Mean age: 14.5 Female: 47% Nationality: Miami Cuba: 61% LA Mexico: 70% Nativity: Not reported |

Design: Longitudinal Survey Setting: Miami, LA |

Acculturative Stress Definition: Parental Acculturation Stress was defined as a construct consisting of perceived discrimination, experiencing a negative context of reception, and acculturative stress. Measure: Latent variable was developed from scores on the Perceived Discrimination Scale, Negative Context of Reception Items (Schwartz et al., 2014), and Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory (Rodriguez et al., 2002) |

CES-D | Increases in parental acculturative stress overtime were associated with higher adolescent depressive symptoms (β=0.045, p<0.5). |

| Paat et al. (2016) | N= 775 Mean age: 14 Male: 52% Nationality: Mexico: 100% Nativity: US born: 57% |

Design: Longitudinal Survey Setting: San Diego and Miami |

Discrimination Definition: Anticipated discrimination is not conceptually defined. Measure: One item asking participants if they believed that they would continue to be discriminated regardless of level of education Family Culture Conflict Definition: Parent-child conflict is defined as discrepancies in the way of handling things between the participants and their parents. Measure: Two items asking how often adolescent and parents preferred American ways of doing things. Variable was derived from subtracting the perceived parental responses from the participants’ response. |

CES-D | Anticipated discrimination was associated with depressive tendencies (β=0.104, p<0.01), but parent-child conflict was not. |

| Park et al. (2017) | N=269 Mean age: 14.1 Female: 57% Nationality: Mexico: 100% Nativity: US Born: 71% |

Design: Longitudinal Survey Setting: Midwest |

Discrimination Definition: Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination is defined as unfair treatment from others on the basis of one’s race or ethnicity. Measure: Perceptions of Racism in Children and Adolescents Scale (Pachter, Szalacha, Bernstein, & García Coll, 2010) |

CDI-2 | Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination and depressive symptoms were associated at all three time points (T1: r=0.33, p<0.001; T2: r=0.39, P<0.001: T3: r=0.39, p<0.001) |

| Piña-Watson et al. (2015a) | N= 516 Mean age: 16.2 Female: 53% Nationality: Mexico: 100% Nativity: US born: 92% |

Design: Cross Sectional Survey Setting: 1 high school in South Texas |

Family Culture Conflict:

Definition: Family stress was not defined. Measure: BSS Family Stress Subscale Discrimination: Definition: Discrimination stress was not defined. Measure: BSS Discrimination Subscale Intragroup Rejection: Definition: Peer stress was not defined. Measure: BSS Peer Stress Subscale |

CES-D | Family stress (r=0.45, p<0.001), discrimination (r=0.36, p<0.001), and peer stress (r=−0.33, p<0.001) were associated with depressive symptoms. |

| Piña-Watson (2015b) | N= 524 Mean age: 16 Female: 53% Nationality: Mexico: 100% Nativity: US born: 91% |

Design: Cross Sectional Survey Setting: 1 high school in South Texas |

Bicultural Stress: Definition: “Bicultural stress is that which results from difficulties navigating both the majority cultural and culture of origin.” (p. 671). Measure: BSS Total scale Family Culture Conflict: Definition: Family stress was not defined. Measure: BSS Family Stress Subscale Discrimination: Definition: Discrimination stress was not defined. Measure: BSS Discrimination Subscale Intragroup Rejection: Definition: Peer stress was not defined. Measure: BSS Peer Stress Subscale |

CES-D | Family stress (r=0.438, p<0.01), discrimination (r=0.33, p<0.01), and peer stress (r=0.31, p<0.01) were associated with depressive symptoms. Total bicultural stress was associated with depression (β=0.467, p<0.001). |

| Potochnick et al. (2012) | N= 463 Mean age: 15 Female: 50–56% Nationality: Mexico: 46–74% Nativity: US born: 26–83% |

Design: Cross Sectional Survey Setting: High schools in NC and LA |

Discrimination:

Definition: Perceived discrimination was not defined. Measure: Perceived discrimination was measured based on the likelihood of experiencing four hypothetical situations of mistreatment due to race and a daily diary checklist of experiences of discrimination. |

Profile of Mood States (McNair et al., 1971) | Perceived discrimination was associated with daily depressive symptoms (b=0.06, p<0.01). |

| Potochnick et al. (2010) | N= 255 Mean age: 13.9 Female: 56% Nationality: Mexico: 70% Nativity: US born: 0% |

Design: Cross Sectional Survey Setting: 25 NC High Schools and Middle Schools |

Discrimination:

Definition: Discrimination was not defined. Measure: Four items from the Youth Adaptation and Growth Questionnaire (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001) Immigration Stress: Definition: Migration stress was not defined. Measure: Number of years the adolescent was separated from primary caregiver, presence of a stressful migration event, and adolescent’s involvement and satisfaction with the decision to move to US |

CDI-2 | Dissatisfaction with migration (AOR 1.67; 95%CI 1.03–2.69), not having documentation upon entering the US (AOR 7.89; 95%CI 1.33–46.79), and experiencing discrimination (AOR 55.09; 95%CI 2.10–1448.0) associated with depression. |

| Schwartz et al. (2014) | N= 302 Mean age: 14.5 Female: 47% Nationality: Miami: Cuba: 61% LA: Mexico: 70% Nativity: US born: 0% |

Design: Longitudinal Survey Setting: Miami and LA |

Discrimination:

Definition: Discrimination was defined as “micro-aggressions, specific acts of prejudice, exclusion, denigration, or violence and to generally unwelcoming climate directed toward individuals because of their racial or ethnic group” (p. 2). Measure: Seven items asking about the degree to which participants were treated unfairly by members of the receiving community Context of Reception: Definition: Context of reception is “the opportunity structure, degree of openness versus hostility, and acceptance in the local community” (p. 2). Measure: Nine items reflecting the possibility of achieving the American Dream and the feeling of being blocked or thwarted in one’s attempts to integrate oneself into the receiving community and society. |

CES-D | Perceived discrimination in Miami (r=0.04, p<0.05) and LA (r=0.3, p<0.01) samples was associated with depressive symptoms. Negative context of reception was also associated with depressive symptoms in Miami (r=0.42, p<0.001) and LA (r=0.25, p<0.001) samples. |

| Stein et al. (2012) | N= 190 Mean age: 14 Female: 53% Nationality: Mexico: 78% Nativity: US born: 60% |

Design: Cross Sectional Survey Setting: 3 NC schools |

Discrimination:

Definition: Discrimination was not defined. Measure: 19-items assessing for peer discrimination Acculturative Stress: Definition: Acculturative stress is “the stress that results from the interactions between different cultural groups” (p. 1340). Measure: BSS |

MFQ | Acculturative stress (r=0.22; p<0.05) and discrimination (r=0.35; p<0.05) were associated with depressive symptoms. |

| Stein & Polo (2014) | N= 159 Mean age: 13.1 Female: 50% Nationality: Mexico: 100% Nativity: US born: 52% |

Design: Cross sectional Survey Setting: 3 LA middle schools |

Family Culture Conflict:

Definition: Cultural Value Gap is “the differential incorporation of US values between parents and children” (p. 189). Measure: Cultural gap variable created by subtracting youth affiliative obedience from parent affiliative obedience. Measurement of the gap assessed difference in values between adolescent and parent. |

CES-D | Affiliative obedience cultural value gap scores were associated with depressive symptoms (β=0.26, p<0.001). |

| Stein et al. (2016) | N= 71 Mean age: 15 Female: 50% Nationality: Mexico: 60% Nativity: US born: 53% |

Design: Longitudinal Survey Setting: Southeast US Community |

Discrimination:

Definition: Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination was defined as “perceived unfair, biased, or discriminatory treatment by adults and peers in schools” (p. 263). Measure: Adult and Peer Discrimination Scale (Way, 1997) |

MFQ | Peer (b=0.11; p<0.01) and adult discrimination (b=0.16; p<0.01) was associated with depressive symptoms for Latino youth. |

| Wiesner et al. (2015) | N= 40 Mean age: 13.4 Female: 50% Nationality: Mexico: 82% Nativity: US born: 90% |

Design: Cross sectional Survey Setting: 1 School in Texas |

Family Culture Conflict:

Definition: Mother-youth acculturation gap is defined as “differences in acculturation level between parents and their children” (p. 1). Measure: Difference in the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II (Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995) for parents and children on Anglo and heritage culture orientations |

CES-D | Higher levels of mother-youth acculturation gap for mothers with Mexican orientation were associated with youth depressive symptoms (r=0.36; p<0.05). |

| Young et al. (2016) | N= 90 Age: <16: 74% Female: 56% Nationality: Mexico: 32% Nativity: US born: 78% |

Design: Cross sectional Survey Setting: Pediatric clinic in southern US |

Discrimination: Definition: Perceived discrimination was not conceptually defined. Measure: Perceived Discrimination Scale (Whitbeck et al., 2001) |

CES-D | Perceived discrimination was associated with depressive symptoms (r-0.313; p=0.003). |

| Zeiders et al. (2013) | N= 323 Mean age: 15.3 Female: 50% Nationality: Mexico: 77% Nativity: US born: 72% |

Design: Longitudinal Survey Setting: 5 high schools in Illinois |

Discrimination:

Definition: Perceived ethnic discrimination is “mistreatment based on differences from the majority culture on language and, in the case of individuals born outside the United States, immigration status” (p. 953). Measure: Ten-item scale asking how often teens were affected by discrimination from general public, authority figures, and teachers (Whitbeck et al, 2001) |

CES-D | Perceived ethnic discrimination associated with depressive symptoms in the short term for males (r=0.46; p<0.001) and females (r=0.28; p<0.001), but not associated with depressive symptoms over time. |

| Note. BSS = Bicultural Stress Scale (Romero & Roberts, 2003); CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1991); CDI-2 = Children’s Depression Inventory 2 (Kovacs & Multi-Health Systems Staff, 2011); HSI-AV = Hispanic Stress Inventory – Adolescent Version (Cervantes et al., 2012); LA = Los Angeles; MFQ= Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (Angold et al., 1987); NC = North Carolina | |||||

Similar cultural stressors in the 33 articles were grouped into categories. The categories were labeled as follows: discrimination, family culture conflict, acculturative and bicultural stress, intragroup rejection, immigration stress, and context of reception. For each category, we determined (a) how frequently the stressors in that category were discussed, (b) how the stressors were labeled, defined, and measured; and (c) how the stressors in each category were related to depressive symptoms. Based on our findings, recommendations are made for research, practice, and policy with this population.

Results

Seventeen of the 33 studies had a cross-sectional design, and 16 had a longitudinal design. Six different classifications of cultural stressors were identified in this review: Discrimination, family culture conflict, acculturative and bicultural stress, intragroup rejection, immigration stress, and context of reception. Table 2 provides a brief description of these classifications of cultural stressors.

Table 2.

Cultural Stressors and Definitions

| Cultural Stressor | Definition |

|---|---|

| Discrimination | Unfair, differential treatment based on ethnicity, including negative behaviors from others such as derogatory remarks, prejudicial treatment, and violence |

| Family Culture Conflict | Disagreement with a family member related to a discrepancy between his or her cultural values and those of the adolescent |

| Acculturative Stress | The stress that results from acculturation, which is the process of changing values and practices as a result of coming in contact with another culture |

| Bicultural Stress | The difficulties experienced when simultaneously navigating between one’s heritage culture and a host culture |

| Intragroup Rejection | Becoming the recipient of negative behaviors and remarks from another individual within the same ethnic group |

| Immigration Stress | Challenges surrounding the event of immigrating to the new country |

| Context of Reception | “[T]he opportunity structure, degree of openness versus hostility, and acceptance in the local community” (Schwartz et al., 2014, p. 2) |

Discrimination

Cultural stressors related to discrimination were examined in 26 out of 33 studies (79%). These stressors were labeled ethnic microaggressions (Huynh, 2012), anticipated discrimination (Paat, 2016), perceived ethnic discrimination (Cano et al., 2015; Davis et al., 2016; Huq, Stein, & Gonzalez, 2016; Park, Williams, Lijuan, & Alegría 2017; Zeiders, Umaña-Taylor, & Derlan, 2013), perceived discrimination (Basáñez, Unger, Soto, Crano, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2013; Chithambo, Huey, & Cespedes-Knadle, 2014; Gonzales-Backen, Bámaca-Colbert, Noah, & Rivera, 2017; Young, 2016), discrimination stress (Cervantes et al., 2015; Cervantes, Fisher, Córdova, & Napper, 2012; Piña-Watson et al., 2015a; Piña-Watson, Llamas, & Stevens, 2015b), societal discrimination (Behnke, Plunkett, Sands, & Bámaca-Colbert, 2011), and every day discrimination (Lorenzo-Blanco & Unger, 2015). Although these terms were defined differently, all the definitions suggested that discrimination for Latino/a adolescents involves “unfair, differential treatment” (Lorenzo-Blanco & Unger, 2015; Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2011) based on ethnicity (Cano et. al., 2015; Schwartz et al., 2014; Zeiders et al., 2013), and includes negative behaviors from others such as derogatory remarks, prejudicial treatment, and violence (Schwartz et al., 2014).

Discrimination was measured with a variety of instruments, many of which had similar items. Some instruments measured sources of discrimination (Behnke et al., 2011; Gonzales-Backen et al., 2017; Lopez, LeBron, Graham, & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016; Stein et al., 2012; Zeiders et al., 2013), whereas others measured specific types of discriminatory behaviors (Cano et al., 2015; Davis et al., 2016; Cervantes et al., 2012; Cervantes et al., 2015), the frequency of discrimination (Basáñez et al., 2013; Chithambo et al., 2014; Lorenzo-Blanco & Unger, 2015; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011), or the presence of discrimination (Lo, Hopson, Simpson, & Cheng, 2017). Three studies used instruments that assessed the adolescent’s level of discomfort with experiences of discrimination (Huynh, 2012; Piña-Watson et al., 2015a; Piña-Watson et al., 2015b).

All studies that examined discrimination found significant relationships between discrimination and depressive symptoms. Societal discrimination (Behnke et al., 2011), anticipated discrimination (Paat, 2016), discrimination stress (Cervantes et al., 2012; Cervantes et al., 2015), perceived discrimination (Basáñez et al., 2013; Chithambo et al., 2014; Gonzales-Backen et al., 2017; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011; Potochnick, Perreira, & Fuligni, 2012; Potochnick & Perreira, 2010; Young, 2016), ethnic discrimination from teachers and peers (Huq et al., 2016; Stein, Supple, Huq, Dunbar, & Prinstein, 2016), and ethnic microaggression frequency (Huynh, 2012) all had significant positive associations with depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents. These studies thus provide strong evidence for a significant relationship between discrimination and depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents.

Family Culture Conflict

Cultural stressors related to family culture conflict were examined in 11 out of 33 studies (33%). These stressors were labeled parent adolescent conflict (Bámaca-Colbert, Umaña-Taylor, & Gayles, 2012; Paat, 2016), culture conflict with parents (Behnke et al., 2011), intergenerational conflict (Li, 2014), parent adolescent acculturation conflict (Huq et al., 2016), acculturation gap stress (Cervantes et al., 2015; Cervantes et al., 2012), family stress (Piña-Watson et al., 2015a; Piña-Watson et al., 2015b), mother-youth acculturation gap (Wiesner, Arbona, Capaldi, Kim, & Kaplan, 2015), and cultural value gap (Stein & Polo, 2014). The definitions provided for these stressors all highlighted disagreement with a family member related to a discrepancy between his or her cultural values and those of the adolescent (Behnke et al., 2011; Stein & Polo, 2014).

A variety of instruments were used to measure family culture conflict. Nine studies used instruments that assessed conflict with the adolescents’ parents (Bámaca-Colbert et al., 2012; Behnke et al., 2011; Cervantes et al., 2015; Cervantes et al., 2012; Huq et al., 2016; Li, 2014; Paat, 2016; Stein & Polo, 2014; Wiesner et al., 2015), while two studies measured conflict with any family member (Piña-Watson et al., 2015a; Piña-Watson et al., 2015b). All eleven studies measured discrepancies in values relating to traditions (Behnke et al., 2011; Piña-Watson et al., 2015a), cultural norms (Cervantes et al., 2015; Cervantes et al., 2012; Stein & Polo, 2014), or “different ways of doing things” (Li, 2014).

Ten studies found a significant relationship between family culture conflict and depressive symptoms. Parent adolescent conflict (Bámaca-Colbert et al., 2012), acculturation gap stress (Cervantes et al., 2015; Cervantes et al., 2012), parent adolescent acculturation conflict (Huq et al., 2016), cultural value gaps (Stein & Polo, 2014), intergenerational conflict (Li, 2014), mother-youth acculturation gaps (Wiesner et al., 2015), and family stress (Piña-Watson et al., 2015a; Piña-Watson et al., 2015b) were significantly and positively associated with depressive symptoms.

Additionally, the relationship between family culture conflict and depressive symptoms was moderated by gender in two studies. At low levels of family conflict, Piña-Watson et al. (2015a) found that girls had higher levels of depressive symptoms, but at high levels of family conflict, boys had greater depressive symptoms. Similarly, Behnke et al. (2011) discovered that culture conflict with father was directly and positively associated with depressive symptoms in boys, but the relationship between culture conflict with father and depressive symptoms was not significant for girls. Based on this evidence, it appears that family culture conflict is significantly associated with depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents, but family culture conflict may relate to the mental health of Latino boys and Latina girls in different ways.

Acculturative and Bicultural Stress

Cultural stressors related to acculturative stress and bicultural stress were examined in 6 out of 33 studies (18%). While both of these terms are commonly thought of as separate concepts with distinct definitions, they were often used interchangeably within the literature. Acculturative stress was commonly defined as the stress that results from acculturation, which is the process of changing values and practices as a result of coming in contact with another culture (Forster et al., 2013). Bicultural stress was consistently defined as the difficulties experienced when simultaneously navigating between one’s heritage culture and a host culture (Cano et al., 2015). However, a few articles in this review addressing bicultural and acculturative stress used these terms interchangeably. Piña-Watson et al. (2015a) discussed the concept of bicultural stress but also referred to this concept as acculturative stress. Likewise, Stein et al. (2012) examined acculturative stress but used the Bicultural Stress Scale (Romero & Roberts, 2003) to operationalize this concept.

Three instruments were used to measure acculturative and bicultural stress. Forster et al. (2013) and Lorenzo-Blanco and Unger (2015) used items from the Acculturative Stress Scale (Gil, Wagner, & Vega, 2000), while Cano et al. (2015), Piña-Watson et al. (2015b), and Stein et al. (2012) used the Bicultural Stress Scale (Romero & Roberts, 2003). Additionally, Lorenzo-Blanco et al. (2016a) examined the association between reported parental acculturation stress and adolescent depressive symptoms, using a latent variable composed of scores from the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory (Rodriguez, Myers, Mira, Flores, & Garcia-Hernandez, 2002), the Perceived Discrimination Scale (Whitbeck, Hoyt, McMorris, Chen, & Stubben, 2001), and Negative Context of Reception scale (Schwartz et al., 2014). Despite claiming to measure different concepts, all of these measures assess for similar stressors, including language stressors, discrimination, and family culture conflict. Additionally, several of the studies reported acculturative and bicultural stress as overall scores without reporting findings for the different subscales of the instruments (Cano et al., 2015, Forster et al. 2013; Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2016a; Lorenzo-Blanco & Unger, 2015; Stein et al., 2012). All six studies found a significant positive association between acculturative or bicultural stress and depressive symptoms. Due to inconsistencies in how these stressors are defined and measured, however, it is difficult to draw conclusions about which specific elements of acculturative and bicultural stress contribute to depressive symptoms.

Intragroup Rejection

Cultural stressors related to intragroup rejection were examined in 4 out of 33 studies (12%). These stressors were labeled as intragroup rejection (Basáñez, Warren, Crano, & Unger, 2014), intra-ethnic discrimination (Lopez et al., 2016), and peer stress (Piña-Watson et al., 2015a; Piña-Watson et al., 2015b). While several authors did not define intragroup rejection, Basáñez et al. (2014) did define intragroup rejection as becoming the recipient of negative behaviors from another individual within the same ethnic group. Three instruments were used to measured intragroup rejection. To assess perceived pressures to “fit in” with Latino peers, Basáñez et al. (2014) used items from the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory (Rodriguez et al., 2002), while Piña-Watson et al. (2015a, 2015b) used the Peer Subscale of the Bicultural Stress Scale (Romero & Roberts, 2003). Lopez et al. (2016) measured intra-ethnic discrimination with two questions assessing for discrimination experienced from other Latinos/as (Lopez et al., 2016). All four studies found a significant relationship between intragroup rejection and depressive symptoms (Basáñez et al., 2014; Lopez et al., 2016; Piña-Watson et al., 2015a; Piña-Watson et al., 2015b).

Immigration Stress

Cultural stressors related to immigration were examined in 3 out of 33 (9%) studies. None of these studies provided a definition of the stressors; however, commonalities in the measures of immigration stress suggest that it is characterized by the specific challenges surrounding the event of immigrating to a new country. In two studies, one instrument was used to assess for immigration stress by asking participants about the difficulties they faced when leaving their home country (Cervantes et al., 2015; Cervantes et al., 2012). Another study examined the overall migration experience by assessing the number of years the adolescent was separated from their primary caregiver, the presence of a stressful migration event, and the adolescent’s involvement and satisfaction with the decision to move to the U.S. (Potochnick & Perreira, 2010). Each of these studies found a significant positive relationship between immigration stress and depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents. The strength of these findings, however, is limited by the lack of a common definition and measurement of immigration stress.

Context of Reception

Cultural stressors related to context of reception were examined in 2 of the 33 (6%) studies. The context of reception was consistently defined as “the opportunity structure, degree of openness versus hostility, and acceptance in the local community” (Schwartz et al., 2014, p. 2). One study measured context of reception using an instrument that assessed the perception of the degree to which the societal opportunity structure did not favor one’s ethnic group (Cano et al., 2015). Another study used an instrument measuring the degree to which individuals felt thwarted in their attempts to integrate into the receiving community (Schwartz et al., 2014). Both of these studies revealed that a perceived negative context of reception was positively associated with depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents (Cano et al., 2015; Schwartz et al., 2014).

Discussion

All of the studies in this review found a significant relationship between a cultural stressor and depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents. However, the strength of these findings differed based on the category of the stressors. Discrimination and family culture conflict were the two most widely researched cultural stressors, and strong evidence exists for the association between these stressors and depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents. Acculturative and bicultural stressors were also associated with depressive symptoms in several studies. Although intragroup rejection, immigration stress, and context of reception were also associated with depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents, fewer studies examined these stressors and thus the evidence supporting their relationship with depressive symptoms is not as robust. More research on intragroup rejection, immigration stress, and context of reception is needed before strong conclusions can be drawn about the relationship between these concepts and depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents.

Limitations

The findings of this review should be understood in the context of the limitations of the literature examined. Most notably, some conclusions were tempered due to inconsistent definitions provided for the cultural stressors and the variability of the instruments used to measure them. Acculturative and bicultural stress, for example, were associated with depressive symptoms, but it was difficult to draw conclusions about what specific aspects of such stress can be implicated in Latino/a adolescent depression due to the vague and sometimes conflicting definitions of these constructs. Despite these limitations, our conclusions do have research, clinical, and policy implications.

Research Implications

While there were some commonalities in how cultural stressors were conceptualized, the studies varied in how the stressors were defined and measured. One of the main tasks for theorists and researchers seeking to understand the relationship between cultural stressors and depressive symptoms in this population is to develop consistent definitions and use common instruments to measure cultural stressors such as discrimination, family culture conflict, acculturative stress and bicultural stress, intragroup rejection, and immigration stress. Researchers can then compare findings across studies and have more confidence in the evidence generated by the cumulative findings of these studies.

Moving forward, researchers will need to explore cultural stressors that are related to present-day concerns in the Latino/a community. Most studies in this review examined cultural stressors based on foundational research from the early 2000s. For instance, many of the studies used data from the Children of Immigrants Study, a longitudinal study conducted in San Diego and Miami from 1999–2006 (Portes & Rubén, 2012) and Project RED (Reteniendo y Entiendiendo Diversidad para Salud), a longitudinal study conducted in Los Angeles from 2005–2007 (Unger, Ritt-Olson, Wagner, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2009). Although stressors experienced by Latino/a adolescents during the early 2000s are likely still relevant today, there may be others that surfaced in more recent years that have not been addressed. The widespread use of the Internet in this age group, new avenues for immigration, and the current political climate may lead to different types of cultural stress for contemporary Latino/a adolescents. For example, one cultural stressor that was not captured in this review is the fear of deportation and a sense of hopelessness that accompanies it (Androff et al., 2011; Salas, Ayón, & Gurrala, 2013). Future research should also address how resiliency factors, such as a strong bicultural ethnic identity, can protect against depressive symptoms for Latino/a youth facing the cultural stressors identified in this review. While the stressors identified in this review may be unique to Latino/a adolescents in many cases, researchers should examine how these cultural stressors may be impacting the mental health of other groups of ethnic minority and immigrant adolescents.

Clinical Implications

The findings of this review have important implications for clinicians who work with Latina/o adolescents experiencing depressive symptoms. Because evidence suggests that a number of cultural stressors are associated with depression in this group, clinicians should initiate conversations about how these stressors are experienced in the day-to-day lives of the adolescents. Clinicians might then inquire about how adolescents cope with these stressors and explore coping strategies that might mitigate the negative consequences of the stressors.

While the etiology of depression in any group is complex and multi-faceted, this review provides evidence that discrimination in particular is strongly associated with depressive symptoms in Latina/o adolescents. Clinicians therefore should address this issue in their therapeutic work with this group. For example, Latina/o adolescents may benefit from an opportunity to discuss any ethnically based microaggressions, derogatory remarks, and violence they have experienced, within the safety of a therapeutic relationship. Moreover, because studies have noted that a strong sense of ethnic identity can buffer against the effects of discrimination (Huq et al., 2016), clinicians might facilitate ethnic identity exploration in Latina/o adolescents and help them challenge any negative internalized beliefs they hold about themselves as a result of discrimination (Graham, Sorenson, & Hayes-Skelton, 2013; Quintana, 2007).

The review also found that family culture conflict is strongly associated with depressive symptoms in Latina/o adolescents. This finding suggests that culturally relevant family therapy approaches in which Latina/o adolescents and their parents can discuss conflicts related to disparate cultural values would likely be useful. Parents are typically involved in the mental health treatments that their adolescents receive, but for Latino/a youth this may be even more important because their culture often emphasizes the value of familismo, or family closeness (Andrés-Hyman, Ortiz, Añez, Paris, & Davidson, 2006). Clinicians can help Latino/a parents and adolescents explore their conflict through the perspective of culture and acculturation, allowing parents and adolescents to gain new insight into their family interactions (Stein & Polo, 2014).

Public Policy Implications

While therapeutic interventions can be implemented on the individual level to help Latino/a adolescents cope with cultural stressors, action also needs to be taken at local, state, and national policy levels to endorse programs that can minimize their exposure to discrimination, immigration stressors, and negative context of reception. Immigration policy and national dialogue surrounding immigration in the US will affect how Latino/a adolescents experience discrimination, immigration stressors, and context of reception. For example, programs that seek to promote unity and racial/ethnic integration in schools and communities are needed to decrease perceived discrimination and intragroup rejection for Latino/a youth (Seaton & Douglass, 2014). According to professional codes of conduct (American Counseling Association, 2014; American Nurses Association, 2010; American Psychological Association, 2001; National Association of Social Workers, 2008), all mental health disciplines have a responsibility to advocate for patients who are subject to social injustices that impede their mental health. Clinicians thus are called upon to advocate for public policies that promote the mental health of Latina/o adolescents by ensuring acceptance and integration of Latino/a families in their local communities.

Conclusion

Latino/a adolescents face cultural stressors above and beyond those stressors experienced by all adolescents living in the US, and this has contributed to a high rate of depressive symptoms in this population. Discrimination, family culture conflict, acculturative and bicultural stress, immigration stress, intragroup rejection, and context of reception and emerged as cultural stressors that are associated with depressive symptoms in this population. Researchers and practitioners can use this information to drive further research, improve clinical practices, and advocate for policy changes that will ultimately decrease the number of Latino/a adolescents who suffer from depressive symptoms.

Funding Acknowledgment:

The first author was supported by grant # 5T32 NR007066 from the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors report no potential or actual conflicts of interest.

References

- American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics. Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org/docs/ethics/2014-aca-code-of-ethics.pdf?sfvrsn=4

- American Immigration Council. (2011). Arizona SB 1070, legal challenges and economic realities. Retreived from http://www.immigrationpolicy.org/clearinghouse/litigation-issue-pages/arizona-sb-1070%E2%80%8E-legal-challenges-and-economic-realities

- American Nurses Association. (2010). Nursing’s social policy statement: The essence of the profession. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2001). Resolution against racism and in support of the goals of the 2001 UN World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Related Intolerance. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/about/policy/racism.aspx

- Andrés-Hyman RC, Ortiz J, Añez LM, Paris M, & Davidson L (2006). Culture and clinical practice: Recommendations for working with Puerto Ricans and other Latinas (os) in the United States. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 37(6), 694–701. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.37.6.694 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Androff D, Ayon C, Becerra D, Gurrola M, Moya Salas L, Krysik J, … Segal E (2011). U.S. immigration policy and immigrant children’s well-being: The impact of policy shifts. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 38, 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Arrington EG, & Wilson MN (2000). A re-examination of risk and resilience during adolescence: Incorporating culture and diversity. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 9(2), 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Bámaca-Colbert MY, Umaña-Taylor AJ, & Gayles JG (2012). A developmental-contextual model of depressive symptoms in Mexican-origin female adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 406–421. doi: 10.1037/a0025666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basáñez T, Unger JB, Soto D, Crano W, & Baezconde-Garbanati L (2013). Perceived discrimination as a risk factor for depressive symptoms and substance use among Hispanic adolescents in Los Angeles. Ethnicity and Health, 18(3), 244–261. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.713093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basáñez T, Warren MT, Crano WD, & Unger JB (2014). Perceptions of intragroup rejection and coping strategies: Malleable factors affecting Hispanic adolescents’ emotional and academic outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(8), 1266–1280. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.713093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke AO, Plunkett SW, Sands T, & Bámaca-Colbert MY (2011). The relationship between Latino adolescents’ perceptions of discrimination, neighborhood risk, and parenting on self-esteem and depressive symptoms. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(7), 1179–1197. doi: 10.1177/0022022110383424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bourhis RY, Moise LC, Perreault S, & Senecal S (1997). Towards an Interactive Acculturation Model: A social psychological approach. International Journal of Psychology, 32(6), 369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Cano MÁ, Schwartz SJ, Castillo LG, Romero AJ, Huang S, Lorenzo-Blanco EI,…Szapocznik J (2015). Depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors among Hispanic immigrant adolescents: Examining longitudinal effects of cultural stress. Journal of Adolescence, 42, 31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan S (2007). Latinos, acculturation, and acculturative stress: A dimensional concept analysis. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 8(2), 93–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Hispanic or Latino populations. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/populations/REMP/Latino/a.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Youth risk behavior surveillance- United States, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6304.pdf

- Cervantes RC, Cardoso JB, & Goldbach JT (2015). Examining differences in culturally-based stress among clinical and nonclinical Hispanic adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(3), 458–467. doi: 10.1037/a0037879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes RC, Fisher DG, Córdova D Jr., & Napper LE (2012). The Hispanic Stress Inventory—Adolescent Version: A culturally informed psychosocial assessment. Psychological Assessment, 24(1), 187–196. doi: 10.1037/a0025280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chithambo TP, Huey SJ Jr., & Cespedes-Knadle Y (2014). Perceived discrimination and Latino youth adjustment: Examining the role of relinquished control and sociocultural influences. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 2(1), 54–66. doi: 10.1037/lat0000012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I, Arnold B, & Maldonado R (1995). Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 17(3), 275–304. doi: 10.1177/07399863950173001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AN, Carlo G, Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, … Soto D (2016). The longitudinal associations between discrimination, depressive symptoms, and prosocial behaviors in U.S. Latino/a recent immigrant adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(3), 457–470. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0394-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MY, Updegraff KA, Roosa MW, & Umaña-Taylor AJ (2011). Discrimination and Mexican-origin adolescents’ adjustment: The moderating roles of adolescents’, mothers’, and fathers’ cultural orientations and values. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(2), 125–139. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9467-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essed P (1991). Understanding everyday racism. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Forster M, Dyal SR, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Chou CP, Soto DW, & Unger JB (2013). Bullying victimization as a mediator of associations between cultural/familial variables, substance use, and depressive symptoms among Hispanic youth. Ethnic Health, 18(4), 415–432. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.754407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganong LH (1987). Integrative reviews of nursing research. Research in Nursing and Health, 10(1), 1–11. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770100103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, & Vega WA (2000). Acculturation, familism, and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: Longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology, 28(4), 443–458. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales-Backen MA, Bámaca-Colbert MY, Noah AJ, & Rivera PM (2017). Cultural profiles among Mexican-origin girls: Associations with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 5(3), 157–172. doi: 10.1037/lat0000069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JR, Sorenson S, & Hayes-Skelton SA (2013). Enhancing the cultural sensitivity of Cognitive Behavioral interventions for anxiety in diverse populations. The Behavior Therapist, 36(5), 101–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyll M, Matthews KA, & Bromberger JT (2001). Discrimination and unfair treatment: Relationship to cardiovascular reactivity among African American and European American women. Health Psychology, 20(5), 315–325. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.5.315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huq N, Stein GL, & Gonzalez LM (2016). Acculturation conflict among Latino youth: Discrimination, ethnic identity, and depressive symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(3), 377–385. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh VW (2012). Ethnic microaggressions and the depressive and somatic symptoms of Latino and Asian American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(7), 831–846. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9756-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, & Multi-Health Systems Staff. (2011). CDI-2: Children’s Depression Inventory 2nd edition technical manual. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y (2014). Intergenerational conflict, attitudinal familism, and depressive symptoms among Asian and Latino/a adolescents in immigrant families: A latent variable interaction analysis. Journal of Social Service Research, 40(1), 80–96. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2013.845128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lo C, Hopson L, Simpson G, & Cheng T (2017). Racial/ethnic differences in emotional health: A longitudinal study of immigrants’ adolescent children. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(1), 92–101. doi: 10.1007/s10597-016-0049-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez WD, LeBrón AMW, Graham LF, & Grogan-Kaylor A (2016). Discrimination and depressive symptoms among Latina/o adolescents of immigrant parents. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 36(2), 131–140. doi: 10.1177/0272684X16628723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Meca A, Unger JB, Romero A, Gonzales-Backen M, Piña-Watson B, … & Villamar JA (2016a). Latino parent acculturation stress: Longitudinal effects on family functioning and youth emotional and behavioral health. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(8), 966. doi: 10.1037/fam0000223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Romero AJ, Cano MÁ, Baezconde-Garbanati L, … & Huang S (2016b). A process-oriented analysis of parent acculturation, parent socio-cultural stress, family processes, and Latina/o youth smoking and depressive symptoms. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 52, 60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, & Unger JB (2015). Ethnic discrimination, acculturative stress, and family conflict as predictors of depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among Latina/o youth: The mediating role of perceived stress. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(10), 1984–1997. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0339-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D, & Baezconde-Garbanati L (2011). Acculturation, gender, depression, and cigarette smoking among U.S. Hispanic youth: The mediating role of perceived discrimination. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(11), 1519–1533. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9633-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons PA, Coursey LE, & Kenworthy JB (2013). National identity and group narcissism as predictors of intergroup attitudes toward undocumented Latino immigrants in the United States. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 35(3), 323–335. doi: 10.1177/0739986313488090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNair DM, Lorr M, & Droppelman LF (1971). Manual for the profile of mood states. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Services. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, & the PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(6). doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers. (2008). Code of ethics. Retrieved from http://www.socialworkers.org/pubs/code/code.asp?

- Neblett EW, Rivas-Drake D, & Umaña-Taylor AJ (2012). The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Development Perspectives, 6(3), 295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00239.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paat Y-F (2016). Strain, psychological conflicts, aspirations-attainment gap, and depressive tendencies among youth of Mexican immigrants. Social Work in Public Health, 31(1), 19–29. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2015.1087910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachter LM, Szalacha LA, Bernstein BA, & García Coll C (2010). Perceptions of Racism in Children and Youth (PRaCY): Properties of a self-report instrument for research on children’s health and development. Ethnicity and Health, 15(1), 33–46. doi: 10.1080/13557850903383196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IJK, Williams DR, Lijuan W, & Alegría M (2017). Does anger regulation mediate the discrimination-mental health link among Mexican-origin adolescents? A longitudinal mediation analysis using multilevel modeling. Developmental Psychology, 53(2), 340–352. doi: 10.1037/dev0000235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2015). Latino/a population reaches record 55 million, but growth has cooled. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/06/25/u-s-Latino/a-population-growth-surge-cools/

- Phinney JS, Madden T, & Santos LJ (1998). Psychological variables as predictors of perceived ethnic discrimination among minority and immigrant adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(11), 937–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01661.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piña-Watson B, Dornhecker M, & Salinas SR (2015a). The impact of bicultural stress on Mexican American adolescents’ depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation: Gender matters. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 37(3), 342–364. doi: 10.1177/0739986315586788 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piña-Watson B, Llamas JD, & Stevens AK (2015b). Attempting to successfully straddle the cultural divide: Hopelessness model of bicultural stress, mental health, and caregiver connection for Mexican descent adolescents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(4), 670–681. doi: 10.1037/cou0000116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, & Rubén RG (2012). Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study (CILS), 1991–2006 [Data set]. 10.3886/ICPSR20520.v2 [DOI]

- Portes A, & Rumbaut RG (2001). Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Potochnick S, Perreira KM, & Fuligni A (2012). Fitting in: The roles of social acceptance and discrimination in shaping the daily psychological well-being of Latino youth. Social Science Quarterly, 93(1), 173–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2011.00830.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potochnick SR, & Perreira KM (2010). Depression and anxiety among first-generation immigrant Latino youth: key correlates and implications for future research. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198(7), 470–477. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e4ce24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM (2007). Racial and ethnic identity: Developmental perspectives and research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3), 259. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1991). The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 20(2), 149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez MR, Nuevo R, Chatterji S, & Ayuso-Mateos JL (2012). Definitions and factors associated with subthreshold depressive conditions: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 12(181), 1–7. 10.1186/1471-244X-12-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez N, Myers HF, Mira CB, Flores T, & Garcia-Hernandez L (2002). Development of the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory for adults of Mexican origin. Psychological Assessment, 14(4), 451–461. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers-Sirin L, Ryce P, & Sirin SR (2014). Acculturation, acculturative stress, and cultural mismatch and their influences on immigrant children and adolescents’ well-being In Global perspectives on well-being in immigrant families (pp. 11–30). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, & Roberts RE (2003). Stress within a bicultural context for adolescents of Mexican descent. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 9(2), 171–184. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas LM, Ayón C, & Gurrola M (2013). Estamos traumados: The effect of anti-immigrant sentiment and policies on the mental health of Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Community Psychology, 41(8), 1005–1020. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21589 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, & Douglass S (2014). School diversity and racial discrimination among African-American adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(2), 156–165. doi: 10.1037/a0035322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG (1988). Concepts of self and social convention: Adolescents’ and parents’ reasoning about hypothetical and actual family conflicts In Gunnar MR & Collins WA (Eds.), The Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology: Development during the transition to adolescence, 21 (pp. 43–77). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Zamboanga BL, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Des Rosiers SE, …Szapocznik J (2015). Trajectories of cultural stressors and effects on mental health and substance use among Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(4), 433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Des Rosiers SE, Villamar JA, Soto DW, … Szapocznik J (2014). Perceived context of reception among recent Latino/a immigrants: Conceptualization, instrument development, and preliminary validation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(1), 1–15. doi: 10.1037/a0033391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GL, Gonzalez LM, & Huq N (2012). Cultural stressors and the hopelessness model of depressive symptoms in Latino adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(10), 1339–1349. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9765-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GL, & Polo AJ (2014). Parent–child cultural value gaps and depressive symptoms among Mexican American youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(2), 189–199. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9724-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GL, Supple AJ, Huq N, Dunbar AS, & Prinstein MJ (2016). A longitudinal examination of perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms in ethnic minority youth: The roles of attributional style, positive ethnic/racial affect, and emotional reactivity. Developmental Psychology, 52(2), 259. doi: 10.1037/a0039902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Wagner KD, Soto DW, & Baezconde-Garbanati L (2009). Parent–child acculturation patterns and substance use among Hispanic adolescents: A longitudinal analysis. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 30(0), 293–313. 10.1007/s10935-009-0178-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]