Abstract

Cellular RNA is decorated with over 170 types of chemical modifications. Many modifications in mRNA, including m6A and m5C, have been associated with critical cellular functions under physiological and/or pathological conditions. To understand the biological functions of these modifications, it is vital to identify the regulators that modulate the modification rate. However, a high‐throughput method for unbiased screening of these regulators is so far lacking. Here, we report such a method combining pooled CRISPR screen and reporters with RNA modification readout, termed CRISPR integrated gRNA and reporter sequencing (CIGAR‐seq). Using CIGAR‐seq, we discovered NSUN6 as a novel mRNA m5C methyltransferase. Subsequent mRNA bisulfite sequencing in HAP1 cells without or with NSUN6 and/or NSUN2 knockout showed that NSUN6 and NSUN2 worked on non‐overlapping subsets of mRNA m5C sites and together contributed to almost all the m5C modification in mRNA. Finally, using m1A as an example, we demonstrated that CIGAR‐seq can be easily adapted for identifying regulators of other mRNA modification.

Keywords: CIGAR‐seq, m5C modification, mRNA modification, NSUN6, pooled CRISPR screen

Subject Categories: Methods & Resources, RNA Biology

CIGAR‐seq is a new method combining pooled CRISPR screen with an epitranscriptomic reporter for identifying mRNA modification regulators. NSUN6 is discovered as a novel mRNA m5C methyltransferase, which together with NSUN2, contributes to almost all the m5C modification in mRNA.

Introduction

Cellular RNAs can be chemically modified in over a hundred different ways, and such modifications have been associated with diverse cellular functions under physiological and/or pathological conditions (Machnicka et al, 2013; Roundtree et al, 2017). To achieve so‐called dynamic epitranscriptomic regulation, each modification needs its distinct deposition, removal, and recognition factors (termed “writers”, “erasers”, and “readers”, respectively). Yet, comparing to the ever‐expanding techniques on detecting RNA modifications (Zhao et al, 2020), the methods to systematically identify writers and erasers of RNA modifications are rather limited. For instance, the first N6‐adenosine (m6A) methyltransferase METTL3 was identified through a combination of in vitro assay, conventional chromatography, electrophoresis, and microsequencing (Bokar et al, 1994; Bokar et al, 1997); and METTL14, a key component of m6A methyltransferase complex, was discovered through the phylogenetic analysis based on METTL3 (Wang et al, 2014). In general, the first strategy is less efficient and may have assay‐specific bias, while the second strategy relies on the prior knowledge of related molecule(s). So far, unbiased method to screen for novel regulators of RNA modifications is still lacking.

Recently, the rapid development of CRISPR‐based gene manipulation provides a new paradigm for high‐throughput and genome‐wide functional screening. Pooled CRISPR screen outperforms array‐based screen by its scalability and low cost, however, was largely restricted to standard readouts, including survival, proliferation, and FACS‐sortable markers (Hanna & Doench, 2020). Most recently, combining with microscopy‐based approaches, CRISPR screen enabled the association of subcellular phenotypes with perturbation of specific gene(s) (Wheeler et al, 2020; preprint: Yan et al, 2020). In studying regulation of gene expression, Perturb‐seq, CRISP‐seq, and CROP‐seq, which combine CRISPR‐based gene editing with single‐cell mRNA sequencing, allowed transcriptome profile to serve as comprehensive molecular readout (Adamson et al, 2016; Dixit et al, 2016; Datlinger et al, 2017), but often with limited throughput. Until now, pooled CRISPR screen with epitranscriptomic readout has not yet been developed.

One important RNA modification, 5‐methylcytosine (m5C), was first identified in stable and highly abundant tRNA and rRNA (Helm, 2006; Agris, 2008; Schaefer et al, 2009). Subsequently, many novel m5C sites in mRNA were discovered by using next‐generation sequencing‐based methods, including mRNA bisulfite sequencing (mRNA‐BisSeq) (Schaefer et al, 2009; Squires et al, 2012), m5C‐RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) (Edelheit et al, 2013), 5‐azacytidine‐mediated RNA immunoprecipitation (Aza‐IP) (Khoddami & Cairns, 2013), and methylation‐individual‐nucleotide‐resolution crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (miCLIP) (Hussain et al, 2013). The m5C modification has been reported to regulate the structure, stability, and translation of mRNAs (Luo et al, 2016; Li et al, 2017a; Guallar et al, 2018; Shen et al, 2018; Schumann et al, 2020) and be catalyzed by NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase family member 2 (NSUN2) (Khoddami & Cairns, 2013; David et al, 2017; Yang et al, 2017). However, recent studies have shown that, even after NSUN2 knockout (KO), a significant number of m5C sites in mRNA remained methylated (Huang et al, 2019; Trixl & Lusser, 2019), suggesting the existence of additional methyltransferase(s) involved in mRNA m5C modification. To fully appreciate the function of this modification, it would be important to identify the remaining methyltransferase(s).

Here, we report a method combining pooled CRISPR screen and a reporter with epitranscriptomic readout, termed CRISPR integrated gRNA and reporter sequencing (CIGAR‐seq). Using CIGAR‐seq with a reporter containing a m5C modification site, we screened through a gRNA library targeting 829 RNA‐binding proteins and identified NSUN6 as a novel m5C writer of mRNA. mRNA‐BisSeq in HAP1 cells without or with NSUN6 and/or NSUN2 knockout showed NSUN6 and NSUN2 worked on non‐overlapping subsets of mRNA m5C sites and together contributed to almost all the m5C modification in mRNA. Finally, using m1A as an example, we demonstrated that CIGAR‐seq can be easily adapted for studying other mRNA modification.

Results

CIGAR‐seq: Pooled CRISPR screening with a epitranscriptomic readout

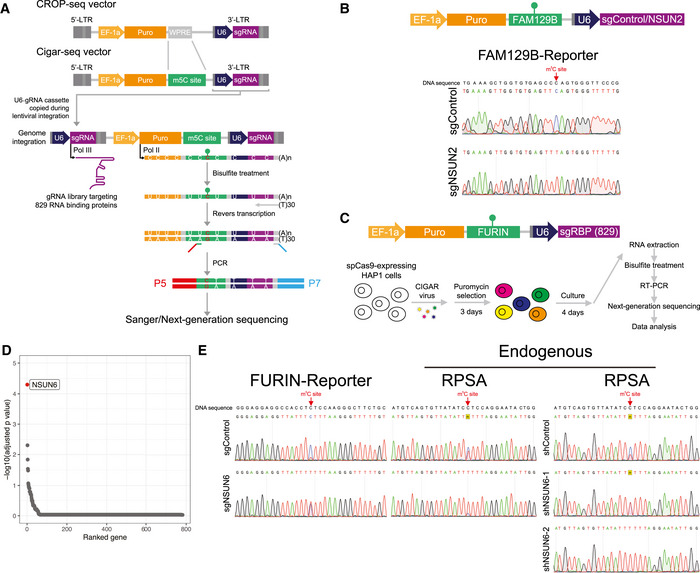

In CIGAR‐seq, to integrate pooled CRISPR screening with a epitranscriptomic readout, here more specifically m5C modification readout, we adopted the previously developed CROP‐seq method (Datlinger et al, 2017) and replaced the WPRE cassette on the original vector by an endogenous m5C site with its flanking region (Fig 1A). Thereby, the mRNA molecules transcribed from this lentiviral vector contain a selection marker followed by an endogenous m5C site, a U6 promoter and a gRNA sequence. To detect the m5C level in the gRNA sequence‐containing transcripts, total mRNA was firstly subjected to bisulfite treatment followed by reverse transcription. Subsequently, a primer pair flanking the m5C site and gRNA sequence was used to amplify the region for Sanger or next‐generation sequencing (Fig 1A). In this way, the methylation level of the m5C reporter site can be measured and associated with the gRNA targeting a specific gene.

Figure 1. CIGAR‐seq identified NSUN6 as a novel mRNA methyltransferase.

- An illustration of CIGAR‐seq method in studying m5C modification. The WPRE cassette on the original CROP‐seq vector was replaced by an endogenous m5C site with its flanking region. To measure the m5C level of the reporter site in gRNA sequence‐containing transcripts, mRNA was subjected to bisulfite treatment followed by reverse transcription. Then, a primer pair flanking the m5C site and gRNA sequence was used to amplify the region for subsequent Sanger or next‐generation sequencing.

- Validation of CIGAR‐seq method using a m5C reporter site derived from FAM129B gene with a control gRNA without target genes and a gRNA targeting NSUN2. Upon NSUN2 knockout, the m5C modification is diminished in the FAM129B reporter mRNA, whereas the modification remains intact in control knockout cells.

- The application of CIGAR‐seq in screening for regulators of m5C sites. Cas9‐expressing HAP1 cells were transduced with viral particles that express Cigar vectors combining NSUN2‐independent m5C reporter sites derived from FURIN gene and a gRNA library targeting 829 RBPs. Seven days after transduction, enriched polyA RNA was bisulfite‐treated, reveres‐transcribed, and PCR‐amplified using primers flanking the m5C site and gRNA sequence to generate NGS library.

- The rank of genes whose knockout reduced m5C modification rate of the reporter site. To identify the high‐confident candidate genes, information of multiple gRNAs of the same genes was combined using the Stouffer’s method, then a combined P‐value for each gene was calculated using the weighted version of Stouffer’s method. NSUN6 was the top hit.

- Validation of NSUN6 as a mRNA m5C methyltransferase. Knockout as well as knock‐down NSUN6 reduced the m5C level in both FURIN m5C reporter transcripts and endogenous NSUN2‐independent m5C sites in RPSA gene.

As a proof‐of‐concept experiment, a known NSUN2‐dependent m5C site in FAM129B (also known as NIBAN2) gene was cloned into CIGAR‐seq vector, together with a control gRNA without any target gene or a gRNA targeting NSUN2 (Fig 1B, upper panel). Seven days after transduction into Cas9‐expressing HAP1 cells, m5C modification level on the reporter transcripts was measured. The result demonstrated that, upon NSUN2 perturbation (Fig EV1A), the m5C modification rate reduced significantly in the reporter containing NSUN2 targeting gRNAs (Fig 1B, lower panel), whereas the modification remained intact in the reporter containing the control gRNA (Fig 1B, upper panel).

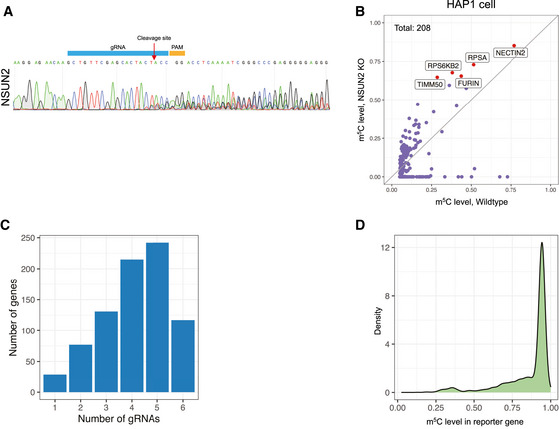

Figure EV1. NSUN2 Knockout and the effect on the reporter as well as endogenous m5C sites.

- The NSUN2‐KO efficiency in Cas9‐expressing HAP1 cells. Seven days after viral transduction, NSUN2 was efficiently mutated.

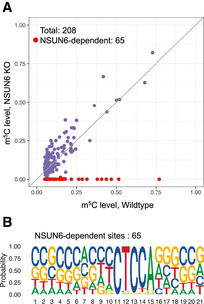

- Scatter plot demonstrating the effect of NSUN2 knocked out in HAP1 cells. 208 m5C sites were identified in wild‐type HAP1 cells, 90 (43.3%) of which showed significantly reduced m5C level in NSUN2‐KO cells. The five m5C sites with the highest modification rate in NSUN2‐KO cells were highlighted as red dots and marked with gene names. The gray line represents the diagonal line, along which the modification rate is equal between wild‐type and NSUN2 knockout cells.

- Distribution of genes with different number of gRNAs detected.

- Density plot of m5C level of the reporter site associated with individual gRNA. The Y‐axis represents the density of gRNAs.

CIGAR‐seq identified NSUN6 as a novel mRNA methyltransferase

As suggested by previous studies that large amount of m5C sites in mRNA remained methylated after NSUN2 knockout (Huang et al, 2019; Trixl & Lusser, 2019), we sought to utilize CIGAR‐seq to identify gene(s) that mediate the m5C modification on NSUN2‐independent sites. First, to determine the NSUN2‐independent m5C sites, we established NSUN2 knockout (NSUN2‐KO) HAP1 cells (Fig EV2A), and performed mRNA bisulfite sequencing (mRNA‐BisSeq) in wild‐type as well as NSUN2‐KO cells. Following bioinformatic pipeline proposed by Huang et al (2019), a set of 208 m5C sites was identified in wild‐type HAP1 cells (Materials and Methods), only 90 (43.3%) of which showed significantly reduced m5C level in NSUN2‐KO cells (Fig EV1B).

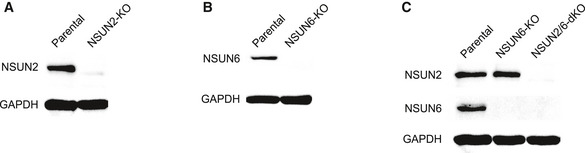

Figure EV2. KO of NSUN2 and/or NSUN6 in HAP1 cells.

-

A‐CWestern Blot demonstrating the effect NSUN2 (A), NSUN6 (B) as well as NSUN2/6 double knockout (C). NSUN2/6 double knockout (NSUN2/6‐dKO) HAP1 cells were established based on clonal NSUN6‐KO cells.

We then chose a NSUN2‐independent site in the 3’UTR of FURIN gene with a high m5C modification rate as the reporter site for CIGAR‐seq. Meanwhile, a gRNA library targeting 829 RNA‐binding proteins (RBP) was synthesized (Dataset EV1). To establish the CIGAR‐seq vector pool for the genetic screen, the gRNA library was firstly cloned into the vector followed by the insertion of the FURIN m5C site with its flanking genomic region (Materials and Methods). Cas9‐expressing HAP1 cells were then transduced with CIGAR‐seq virus pool (Fig 1C, Materials and Methods). Seven days after transduction, cells were collected and subjected to RNA extraction. Enriched polyA RNA was then bisulfite‐treated, reveres‐transcribed and PCR‐amplified using primers flanking the m5C site and gRNA sequence to generate next‐generation sequencing (NGS) library (Materials and Methods). After pair‐end sequencing and data processing, 811 genes were detected with at least one gRNA, of which 782 genes had at least two gRNAs (Fig EV1C). The m5C modification rate of reporter site was calculated for each gRNA. While the median m5C modification rates of gRNA‐associated reporter sites were around 93.5%, a small part of gRNAs showed significantly reduced m5C rates (Fig EV1D). To prioritize the candidate genes, Stouffer’s method was used to calculate the combined P‐value based on the gRNAs targeting the same gene (Materials and Methods). As shown in Fig 1D, it turned out that NSUN6, a member of NOL1/NOP2/sun domain (NSUN) family, was identified as the best hit with all six gRNAs decreasing the m5C level effectively (Fig 1D and Dataset EV2). Interestingly, NSUN6 was previously reported to introduce the m5C in tRNA (Li et al, 2019). However, two previous studies did not show significant m5C changes in mRNA after NSUN6 perturbation in HeLa cells (Yang et al, 2017; Huang et al, 2019), which might be due to the incomplete gene silencing mediated by siRNA.

To validate our result, a gRNA targeting NSUN6 was inserted into the CIGAR‐seq vector containing the FURIN m5C site. As shown in Fig 1E, perturbation of NSUN6 (Fig EV3A) indeed reduced the m5C level in both reporter mRNA and endogenous NSUN2‐independent m5C site in RPSA gene (Fig 1E, left and middle panels). Furthermore, to rule out the potential off‐target effect of gRNA, we repressed NSUN6 expression using shRNA (Fig EV3B). Again, the m5C level at the endogenous site was also reduced in cells with NSUN6 repression (Fig 1E, right panel). Together, these results confirmed NSUN6 as a bona fide mRNA m5C methyltransferase.

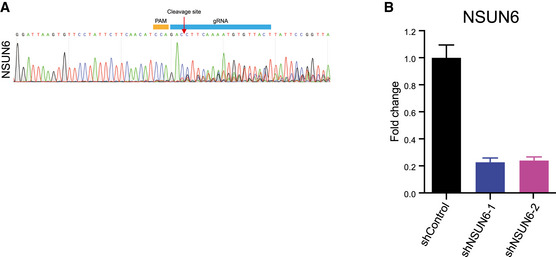

Figure EV3. NSUN6 was efficiently knocked out or knocked down.

- The KO efficiency of NSUN6 in Cas9‐expressing HAP1 cells. Seven days after viral transduction, NSUN6 was efficiently mutated.

- The knockdown efficiency of NSUN6 in HAP1 cells. Three independent biological replicates were performed. Error bars represent SD.

In addition to NSUN6, we selected another two candidate genes, EIF3J and ZCCHC11 with multiple gRNAs (five and six, respectively, Dataset EV2) showing inhibitory effect on m5C modification for validation. However, knockout of neither ZCCHC11 nor EIF3J could reduce the modification rate of the m5C site in the reporter transcripts.

Global profiling of NSUN6‐dependent m5C sites

To globally characterize NSUN6‐dependent m5C sites, we established NSUN6 knockout (NSUN6‐KO) HAP1 cells (Fig EV2B) and performed mRNA‐BisSeq. Of 208 m5C sites identified in wild‐type HAP1 cells, 65 (31.2%) showed significant reduction at m5C level in NSUN6‐KO cells (Fig 2A). To illustrate the features of sequence flanking NSUN6‐dependent m5C sites in HAP1 cells, motif analysis was performed based on the upstream and downstream 10 nucleotide sequences flanking the m5C sites. As shown in Fig 2B, NSUN6‐dependent m5C sites were embedded in slightly GC‐rich environments with a strongly enriched TCCA motif at 3′ of m5C sites. Previously, a similar 3′ TCCA motif was also found at NSUN6 target sites in tRNAs (Li et al, 2019) and has also been proposed as sequence motif around NSUN2‐independent sites in another study (Huang et al, 2019). In comparison, the sequence feature around NSUN2‐dependent m5C sites is distinct, which is enrich for 3′ NGGG motif (Yang et al, 2017; Huang et al, 2019).

Figure 2. Global profiling of NSUN6‐dependent m5C sites.

- mRNA bisulfite sequencing revealed NSUN6‐dependent m5C sites in HAP1 cells. Of 208 m5C sites identified in wild‐type cells, 65 showed significantly reduced modification in NSUN6 knocked out cells. X‐ and Y‐axis represented the modification rate in wild‐type and NSUN6 knocked out HAP1 cells, respectively. The gray line represents the diagonal line, along which the modification rate is equal between wild‐type and NSUN6 knockout cells.

- The sequence features of NSUN6‐dependent m5C sites in HAP1 cells. A strong 3′ TCCA motif was found in NSUN6‐dependent sites.

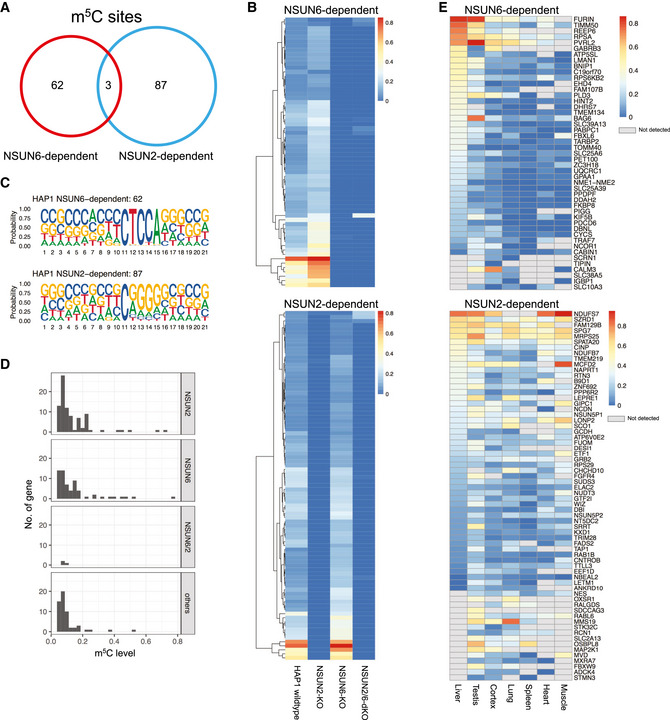

Contribution of NSUN6 and NSUN2 to the mRNA m5C modification

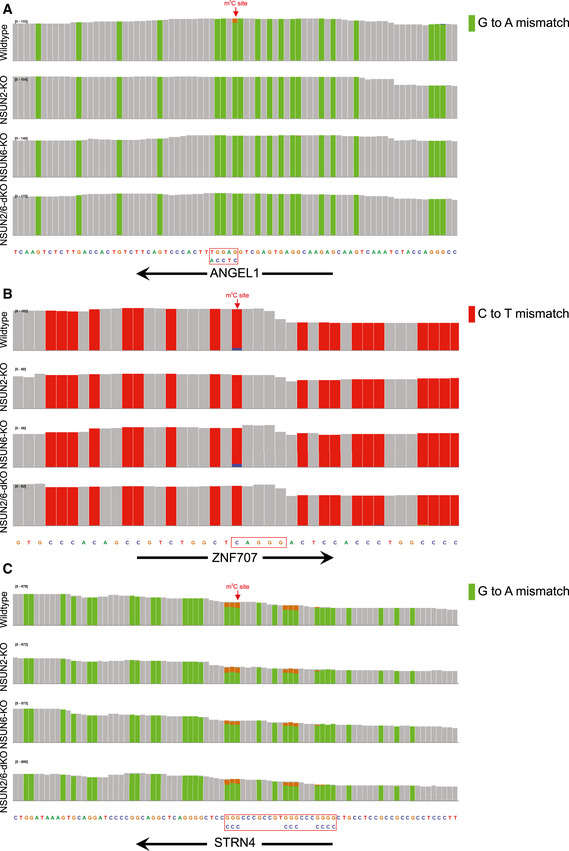

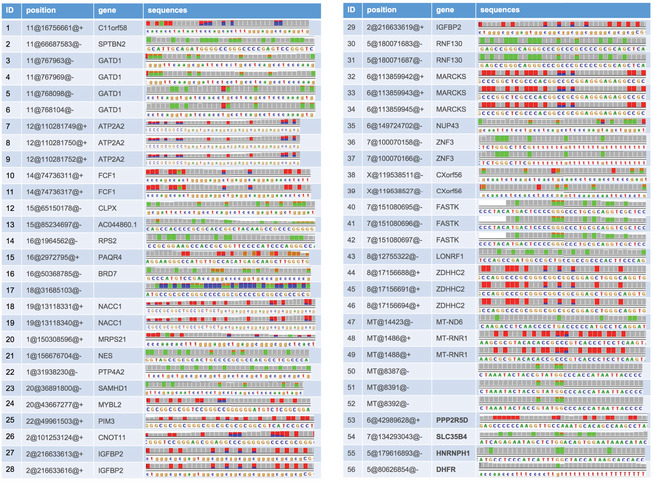

We then evaluated the relative contribution of NSUN6 and NSUN2 to the global mRNA m5C modification. First, comparing between NSUN2‐ and NSUN6‐dependent m5C sites, as shown in Fig 3A, these sites were largely non‐overlapping, suggesting their non‐redundant biological functions. Then, to further examine whether NSUN2 and NSUN6 together are responsible for all mRNA m5C modifications, NSUN2 and NSUN6 double KO (NSUN2/6‐dKO) HAP1 cells were established (Fig EV2C) and subjected to mRNA‐BisSeq analysis. As shown in Fig 3B, the modification of m5C sites depend only on NSUN6 or NSUN2 (62 and 87, respectively) were also abolished in NSUN2/6‐dKO cells. While NSUN6‐dependent sites were strongly enriched for 3′ TCCA motif as shown earlier, NSUN2‐dependent sites were enriched for 3′ NGGG motif as previously reported (Yang et al, 2017; Huang et al, 2019) (Fig 3C). Furthermore, we carefully examined the three sites that showed dependence on both NSUN6 and NSUN2, as well as the 56 sites that were independent of both NSUN6 and NSUN2. Comparing to the other three groups, the group of three overlapping sites had very low m5C level (Fig 3D). In addition, the m5C sites in ANGEL1 and ZNF707 possessed a 3′ TCCA and a 3′ AGGG motif, respectively (Fig EV4A and B), suggesting they are very likely a NSUN6‐ and a NSUN2‐dependent site, respectively, but with low m5C level that led to false negative findings in the mRNA‐BisSeq analysis of some but not all the samples. The remaining m5C site in STRN4 was embedded within a cluster of “pseudo” m5C sites (Fig EV4C), which was highly likely an artifact due to the incomplete bisulfite conversion as suggested before (Haag et al, 2015; Huang et al, 2019). Similarly, the group of 56 NSUN2/6‐independent sites was also highly enriched for such clusters of pseudo m5C sites: 52 sites had at least one pseudo m5C site in vicinity (Fig EV5). The remaining four sites all had very low m5C level.

Figure 3. Comparison between NSUN6‐ and NSUN2‐dependent m5C modification sites.

- The largely non‐overlapping pattern between NSUN2‐ and NSUN6‐dependent m5C sites.

- Heat map showing the m5C modification rate in wild‐type, NSUN2‐KO, NSUN6‐KO, and NSUN2/6‐dKO HAP1 cells for NSUN6‐ (upper panel) and NSUN2‐dependent sites (lower panel), respectively.

- The sequence features of NSUN6‐only‐ (upper panel) and NSUN2‐only‐dependent m5C sites (lower panel) in HAP1 cells. While NSUN6‐dependent sites were strongly enriched for 3′ TCCA motif, NSUN2‐dependent sites were enriched for 3′ NGGG motif.

- The modification rate of 4 groups of m5C sites that showed different dependence. Comparing to the other three groups, the group of three overlapping sites showed very low m5C level.

- Modification rate of NSUN6‐ and NSUN2‐dependent m5C sites across different tissues.

Figure EV4. mRNA‐BisSeq profiles of the three m5C modification sites depend on both NSUN6 and NSUN2.

-

A–CIGV plots showing the m5C sites in ANGEL1, ZNF707, and STRN4 genes. The m5C sites in ANGEL1 (A) and ZNF707 (B) possessed a 3′ TCCA and a 3′ AGGG motif, respectively, while the m5C site in STRN4 was among a cluster of “pseudo” m5C sites (C).

Figure EV5. NSUN2/6‐independent m5C sites.

The group of 56 NSUN2/6‐independent sites was highly enriched for clusters of pseudo m5C sites: 52 sites had at least one pseudo m5C site in vicinity.

Of note, here, to characterize the NSUN6‐ and NSUN2‐in/dependent m5C sites, we set stringent criteria to avoid potential false discovery of m5C sites due to incomplete bisulfite conversion (Materials and Methods). Whereas such stringent criteria would assure the high specificity of our findings, we would likely also miss some of the true m5C sites, particularly those with low modification rate.

To explore the modification rate of NSUN6/2‐dependent m5C sites across different tissues, we resorted to mRNA‐BisSeq data from a previous study (Huang et al, 2019). As shown in Fig 3E, m5C modification on 47 NSUN6‐ and 66 NSUN2‐dependent m5C sites could also be observed in other human tissue(s). While the modification rate of NSUN6‐dependent sites was by and large highest in liver, NSUN2‐dependent ones did not show such tissue biases (Fig 3E).

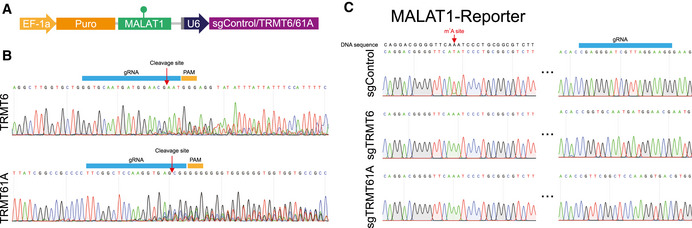

CIGAR‐seq could be used for the study of other mRNA modification

Finally, to explore the potential application of CIGAR‐seq in the study of other mRNA modifications, we turned to N‐1‐methyladenosine (m1A). As N‐1‐methyladenosine (m1A) can cause mis‐incorporation during cDNA synthesis (Hauenschild et al, 2015), its modification can be detected by direct cDNA sequencing. Similar as the previous NSUN2 proof‐of‐concept experiment, we chose a well‐characterized m1A site from MALAT1, which is known to be modified by TRMT6/TRMT61A complex (Dominissini et al, 2016; Li et al, 2017b; Safra et al, 2017). We cloned the site and its flanking region into CIGAR‐seq vector with a control gRNA and two gRNAs targeting TRMT6/TRMT61A complex, respectively (Fig 4A). As shown in Fig 4C, in HAP1 cells with perturbation of either TRMT6 or TRMT61A (Fig 4B), the m1A modification of the reporter site was completely abolished, whereas in cells transduced with control gRNAs, the modification remains intact.

Figure 4. Exemplar application of CIGAR‐seq in the study of m1A modification.

-

AAn illustration of CIGAR‐seq vector designed for m1A modification. A known TRMT6/61A complex‐dependent m1C site in MALAT1 gene was cloned into CIGAR‐seq vector, together with control gRNA as well as gRNAs targeting TRMT6 and TRMT61A, respectively.

-

B, CUpon perturbation of either TRMT6 or TRMT61A in HAP1 cells, the m1A modification was completed abolished in m1A reporter site, whereas the modification remains intact in control knockout cells.

Discussion

Combining pooled CRISPR screening strategy and a reporter with epitranscriptomic readout, CIGAR‐seq for the first time enables the unbiased screening for novel regulators of mRNA modifications. In this study, we demonstrated its power in identification of NSUN6 as a novel mRNA m5C methyltransferase. In addition, we also showed its potential application in studying m1A modification. Integrating additional modification readout strategies into our pipeline, it could be further adapted to investigate other modifications. For instance, we can use CIGAR‐seq to search for potential regulators of RNA editing by simply reading the A‐G or C‐T changes in the cDNA sequence reads derived from A‐I or C‐U RNA editing reporters. m6A‐iCLIP (Linder et al, 2015) or SELECT (Xiao et al, 2018) method, which were used to measure the modification rate of individual m6A site, could also be integrated into our CIGAR‐seq in analyzing m6A regulators. Furthermore, changing reporters to those with other regulatory readout, for example alternative splicing or alternative polyadenylation pattern, the potential application of CIGAR‐seq could be easily extended to screen for factors involved in diverse post‐transcriptional regulations. There, given the readout is based on directly measuring the reporter‐derived RNAs, CIGAR‐seq would be in principle superior to current fluorescence‐reporter‐FACS‐based screening strategies.

Like any other high‐throughput assays, CIGAR‐seq has also its own sensitivity and specificity issues, which could be affected by the choice of reporter and CRISPR system. The reporter could affect its performance in two ways. First, the high or low modification level of the reporter site could result in biased performance in detecting positive or negative regulators. For example, in this study, our m5C site from FURIN genes has a very high modification rate. At this level, it would be much more sensitive in finding the decrease of methylation rate, therefore be much easier to discover the methyltransferase than potential demethylase if any in this case. In contrast, the use of reporter site with low modification rate would not be preferable in identifying methyltransferase. Second, except writer and eraser, most regulators may modulate the modification level through binding to the cis‐regulatory elements, which are not necessarily in direct vicinity of the target site. A reporter constructs with a limited length might not be able to include all the relevant cis‐elements. Consequently, we would fail to identify the regulators with binding sites missed in the reporter. On the other hand, the CIGAR‐seq vector itself may contain artificial regulatory sequences affecting the modification of reporter site, which could result in the assay‐specific artifacts. Therefore, subsequent careful validation with endogenous sites would be essential when working with the CIGAR‐seq. The choice of CRISPR system could also have an effect. The screening based on CRISPR/Cas9 system, as applied in this study, would have limitations in finding potential regulators that are essential for cell survival and/or proliferation (e.g., METTL3/METTL14) since the gRNAs targeted at those essential genes would be largely depleted in the final sequencing library. This problem could be potentially alleviated by adopting CRISPRi or CRISPRa systems. In the future, with further improvements in CRISPR system and development of more sequencing‐based readout with high precision, CIGAR‐seq will become a versatile tool for systematic discoveries of players in multiple layer of RNA‐based post‐transcriptional gene regulation.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Tools table

| Reagent/resource | Reference or source | Identifier or catalog number |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental models | ||

| HAP1 cells (Homo sapiens) | Horizon discovery | C631 |

| HEK‐293T cells (H. sapiens) | ATCC | CRL‐11268 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| LentiCas9‐Blast | Addgene | #52962 |

| CROPseq‐Guide‐Puro | Addgene | #86708 |

| pLKO.1‐puro | Addgene | #10878 |

| pLKO.1‐blast plasmid | This study | N/A |

| psPAX2 | Addgene | #12260 |

| pMD2.G | Addgene | #12259 |

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit anti‐NSUN2 | Proteintech | 20854‐1‐AP |

| Rabbit anti‐NSUN6 | Proteintech | 17240‐1‐AP |

| Mouse anti‐GAPDH | TransGen Biotech | HC301‐01 |

| Goat anti‐mouse IgG‐HRP | Santa cruz biotechnology | sc‐2005 |

| Goat anti‐rabbit IgG‐HRP | Santa cruz biotechnology | sc‐2004 |

| Chemicals, enzymes, and other reagents | ||

| TRIzol® Reagent | Ambion | 15596026 |

| HiScript III 1st Stand cDNA Synthesis Kit | Vazyme Biotech | R312‐02 |

| Hieff qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix | Yeasen | 11201ES08 |

| VAHTS mRNA Capture Beads | Vazyme Biotech | N401 |

| HiScript II Q Select RT SuperMix | Vazyme Biotech | R233‐01 |

| HifairTM II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit | Yeasen | 11121ES60 |

| Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit | Agilent | NC1711873 |

| VAHTS Stranded mRNA‐seq Library Prep Kit | Vazyme Biotech | NR602‐01 |

| High Sensitivity DNA Kit | Agilent | 5067‐4626 |

| Electrocompetent Stbl3 cell | Weidi Biotechnology | DE1046 |

| PEI | Polysciences | 23966‐2 |

| BCA | Beyotime | P0011 |

| Polyvinylidene difluoride membranes | Immobilon‐P | IPVH00010 |

| Pierce™ ECL Western Blotting Substrate | Thermo | 32209 |

| EZ RNA methylation kit | Zymo research | R5002 |

| RMPI1640 medium | Gibco | 22400089 |

| FBS | Gibco | 10270106 |

| P/S | Gibco | 15070063 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Oligonucleotides | This study | Dataset EV3 |

Methods and Protocols

Cell culture and gene manipulation

HAP1 cell was obtained from Horizon discovery and cultured in RMPI1640 medium (Gibco) with 10% FBS (Gibco) and 1% P/S (Gibco) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cas9‐expressing HAP1 cell line was established by using lentiCas9‐Blast plasmid (Addgene). To generate NSUN2‐KO, NSUN6‐KO, and NSUN2/6‐dKO clonal HAP1 cells, Cas9‐expressing HAP1 cells were transduced with CROP‐seq (Addgene) virus expressing following gRNAs: gNSUN2, #1; gNSUN6, #2. NSUN6 knockdown mediated by shRNA was performed using pLKO.1‐blast plasmid (modified from pLKO.1‐puro) with following shRNAs: shControl, #3; shNSUN6‐1, #4; shNSUN6‐2, #5.

RT‐qPCR

Total RNA was extracted by TRIzol® Reagent (Ambion). First‐stand cDNA was synthesized using HiScript III 1st Stand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme). Quantitative PCR was performed by Hieff qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Yeasen) and the BIO‐RAD real‐time PCR system. Following primers were used to detect relative gene expression: NSUN6‐F, #6; NSUN6‐R, #7; GAPDH‐F, #8; GAPDH‐R, #9.

CIGAR‐seq vector with m5C/m1A reporters and individual gRNA

Sequence flanking m5C site of FAM129B was amplified by forward primer #10 and reverse primer #11 from genomic DNA; m5C site of FURIN by forward primer #12 and reverse primer #13, and m1A site of MALAT1 by forward primer #14 and reverse primer #15. Amplified products were used to replace WPRE cassette in CROP‐seq vector (Addgene) by ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme). Afterwards, following gRNAs were inserted at BsmBI sites to knockout individual genes: gControl, #16; gNSUN2, #1; gNSUN6, #2; gTRMT6, #17; gTRMT61A, #18.

m5C detection by bisulfite conversion followed by sanger sequence

Total RNA was extracted by TRIzol® Reagent (Ambion). mRNA was enriched using VAHTS mRNA Capture Beads (Vazyme). 200 ng mRNA was converted by EZ RNA methylation kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s protocol with minor modification. More specifically, mRNA was incubated at 70°C for 10 min, and 60°C for 1 h. Converted RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using HiScript II Q Select RT SuperMix (Vazyme).

To measure m5C rate in FURIN m5C reporter, target site was amplified using vector specific primer pair #19 and #20, and sanger‐sequenced by primer #19. For m5C detection of endogenous m5C site in RPSA, target site was amplified using primer pair #21 and #22, and sanger‐sequenced by primer #21.

m1A detection based on mis‐incorporation during reverse transcription

1 µg total RNA was reverse transcribed by HifairTM II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Yeasen). The region flanking m1A site was amplified by plasmid specific primer pair #23 and #24. The mismatch site was measured by sanger sequencing using primer #23.

mRNA‐BisSeq

The quality of 500 ng bisulfite‐treated mRNA (see above) was assessed using Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit (Agilent) and then subjected to NGS libraries preparation using VAHTS Stranded mRNA‐seq Library Prep Kit (Vazyme). The library quality was assessed using High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent). Paired‐end sequencing (2 × 150 bp) was performed with Illumina NovaSeq 6000 System by Haplox genomics center.

Generation of CIGAR‐seq vector pool with a FURIN m5C reporter

A gRNA library containing 4,975 gRNA targeting 829 RBP (Dataset EV1) was synthesized by GENEWIZ and cloned into CROP‐seq vector (Addgene) at BsmBI sites. For measuring the complexity of the gRNA library, the region harboring gRNA sequence was amplified with primer pair #25 and #26 for NGS. Afterwards, the FURIN m5C reporter was amplified and used to replace WPRE cassette using ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme). During cloning of CIGAR‐seq vector pool, electrocompetent Stbl3 cells (Weidi Biotechnology) were always used.

CIGAR‐seq viral package

HEK‐293T cells were plated onto 15 cm plates at 40% confluence. The next day, cells were transfected with PEI (Polysciences) using 15 µg of CIGAR‐seq vector, 15 µg of psPAX2 (Addgene), and 22.5 µg of pMD2.G (Addgene). Supernatant containing viral particles were harvested at 48 and 96 h and purified with 0.45 µm filter.

Genetic screen for novel m5C regulators

First day, 2 × 108 HAP1 cells were transduced with CIGAR‐seq viral particles (MOI = 0.3).

After 24 h, HAP1 cells were treated with 1 µg/ml of Puromycin.

Puromycin resistant cells were cultured for additional seven days in medium containing 1 µg/ml of Puromycin.

Afterwards, 2 × 108 HAP1 cells were collected for RNA extraction by TRIzol® reagent (Ambion).

All of extracted RNA was used to enrich poly(A)+ mRNA by VAHTS mRNA Capture Beads (Vazyme).

Enriched mRNA was quantified by Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit (Agilent).

A total of 100 ng mRNA was bisulfite converted by EZ RNA methylation kit (Zymo), then reversed transcribed into cDNA using HiScript II Q Select RT SuperMix (Vazyme).

All synthesized cDNA was used as template to PCR‐amplify CIGAR‐seq NGS library with primer pair #27 and #28.

Paired‐end sequencing (2 × 150 bp) was performed with Illumina NovaSeq 6000 System by Haplox genomics center.

Western blotting

HAP1 cells were collected and lysed by RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, 1% EDTA, 1% NP40, 0.1% SDS). Lysate was incubated at 4°C for 30 min, then sonicated with 10 cycles (30 s On /30 s Off), and then centrifuged at 15,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The total protein concentration was measured by BCA (Beyotime). 60 µg total protein was loaded and separated on the 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel. The protein on the gel was transfected to the polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon‐P). The membrane was incubated with primary antibody and horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody, and then proteins were detected using the Pierce™ ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo) by BIO‐RAD ChemiDoc™ XRS+ system. The following antibodies were used for western blotting: NSUN2 (Proteintech), NSUN6 (Proteintech), GAPDH (TransGen Biotech), goat anti‐mouse IgG‐HRP (Santa cruz biotechnology), and goat anti‐rabbit IgG‐HRP (Santa cruz biotechnology).

Computational methods

CIGRA‐seq data analysis

CIGRA‐seq NGS data consists of paired‐end reads. Read1 contains the sequence of m5C reporter site while read2 consists of the gRNA sequence. Raw fastq data were first trimmed using fastp (Chen et al, 2018) to remove low‐quality bases (‐A ‐w 12 ‐‐length_required 30 ‐q 30). Then, the clean read pairs were parsed using a custom script based on pysam package. Specifically, gRNA sequence in read2 was extracted by regex module using regular expression ((CAACTTAACTCTTAAAC[ATCG]{20}CA){s<=1}). m5C reporter sequence was extracted in the similar way ((GTTATTT[TC]{1}TTTAAGG){s<=1}). At most, 1 substitution was allowed during the pattern searching. Read pairs with both reads containing the matched pattern sequences and the m5C sites being C or T were kept for further analysis. Then for each gRNA sequence, the number of supported reads with reporter site being C (m5C) or T was calculated, and the number of C reads divided by the sum of C and T reads represented the m5C level. Only the extracted gRNA sequences that match exactly with the RBP gRNA sequences (Dataset EV1) were kept for further analysis.

To identify the high‐confident candidate genes that regulate m5C level, information of multiple gRNAs of the same genes was combined using the Stouffer’s method. gRNAs with no more than 20 supported reads were filtered out. Genes with only one gRNA detected were filtered out. Then, given a gene i, the m5C level of reporter site correspondence to gRNA j is X i,j., m5C level was converted to Z‐score and P value P i,j was calculated under normal distribution assumption. Then, a combined P‐value for each gene P i was obtain using the weighted version of Stouffer’s method, with the logarithmic scale of read count as weight for each gRNA. Finally, P‐values of multiple tests were adjusted with Benjamini & Hochberg’s method.

mRNA‐BisSeq data analysis

mRNA‐BisSeq data generated in this study were analyzed following the RNA‐m5C pipeline (Huang et al, 2019) (https://github.com/SYSU‐zhanglab/RNA‐m5C). Reference genomes (GRCh38) and gene annotation GTF file was downloaded from Ensemble (http://www.ensembl.org/info/data/ftp/index.html). Briefly, raw paired‐end reads were trimmed using cutadapt (Martin, 2011) (‐a AGATCGGAAGAGCACACGTC ‐A AGATCGGAAGAGCGTCGTGT ‐j 12 ‐e 0.25 ‐q 30 ‐‐trim‐n) and then Trimmomatic (Bolger et al, 2014) (SLIDINGWINDOW:4:25 AVGQUAL:30 MINLEN:36). Clean read pairs were aligned to both C‐to‐T and G‐to‐A converted reference genomes by HISAT2 (Kim et al, 2019). Unmapped and multiple mapped reads were then aligned to C‐to‐T converted transcriptome by Bowtie2 (Langmead & Salzberg, 2012), and the transcript coordinates were liftovered to the genomic coordinates. Reads from HISAT2 and Bowtie2 mapping were merged and filtered using the same criteria as in RNA‐m5C pipeline. Bam file was transformed into pileup file (‐‐trim‐head 6 ‐‐trim‐tail 6). Putative m5C sites were called using script m5C_caller_multiple.py inside RNA‐m5C pipeline (with parameters ‐P 8 ‐c 20 ‐C 2 ‐r 0.05 ‐p 0.05 ‐‐method binomial). Default parameters of RNA‐m5C scripts were used unless otherwise specified.

NSUN6‐dependent m5C sites

First, to determine a set of high‐confident m5C sites in HAP1 cells, five replicates of mRNA‐BisSeq data generated from the WT HAP1 cells were used. The criteria to determine the high‐confident m5C sites were as follows: (i) coverage of the site being at least 20 reads in all five replicates; (ii) number of reads containing the unmodified C being at least 2 in all five replicates; (iii) the WT methylation level (the minimum methylation level from the five replicates) being at least 0.05. Then, to determine the NSUN6‐dependent m5C sites, m5C level of the sites was at least 0.05 in WT HAP1 cells and less than 0.02 or 10% of the WT m5C level in NSUN6‐KO HAP1 cells. NSUN2‐dependent sites were defined based on the same criteria.

Features of the m5C sites

The upstream and downstream 10 bp sequences flanking the m5C sites were extracted from the genome. Motif analysis was performed Using ggseqlogo (Wagih, 2017) R package.

Author contributions

WC and LF developed the concept of the project. WW, LF, LZ, DG, JY, and YT designed and performed experiments. GL performed bioinformatic analysis. WZ, MZ, DD, ZS, QZ, and ZD assisted in performing experiments. WC, LF, GL, YH, WW, JL, HC, and WS reviewed and discussed results. WC, LF, GL, and WW wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Expanded View Figures PDF

Dataset EV1

Dataset EV2

Dataset EV3

Review Process File

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Shenzhen‐Hong Kong Institute of Brain Science‐Shenzhen Fundamental Research Institutions (Grant No. 2019SHIBS0002), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (Grant No. KQTD20180411143432337, JCYJ20190809154407564, and JCYJ20180504165804015) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31701237, 31900431 and 31970601). The authors acknowledge the Center for Computational Science and Engineering of SUSTech for the support on computational resource and acknowledge the SUSTech Core Research Facilities and Guixin Ruan for technical support.

Mol Syst Biol. (2020) 16: e10025

Contributor Information

Liang Fang, Email: fangl@sustech.edu.cn.

Wei Chen, Email: chenw@sustech.edu.cn.

Data availability

All next‐generation sequencing data were submitted to Gene Expression Omnibus under the accession number GSE157368 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE157368).

References

- Adamson B, Norman TM, Jost M, Cho MY, Nunez JK, Chen Y, Villalta JE, Gilbert LA, Horlbeck MA, Hein MY et al (2016) A multiplexed single‐cell CRISPR screening platform enables systematic dissection of the unfolded protein response. Cell 167: 1867–1882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agris PF (2008) Bringing order to translation: the contributions of transfer RNA anticodon‐domain modifications. EMBO Rep 9: 629–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokar JA, Rath‐Shambaugh ME, Ludwiczak R, Narayan P, Rottman F (1994) Characterization and partial purification of mRNA N6‐adenosine methyltransferase from HeLa cell nuclei. Internal mRNA methylation requires a multisubunit complex. J Biol Chem 269: 17697–1704 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokar JA, Shambaugh ME, Polayes D, Matera AG, Rottman FM (1997) Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet‐binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6‐adenosine)‐methyltransferase. RNA 3: 1233–1247 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B (2014) Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30: 2114–2120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J (2018) fastp: an ultra‐fast all‐in‐one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34: i884–i890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datlinger P, Rendeiro AF, Schmidl C, Krausgruber T, Traxler P, Klughammer J, Schuster LC, Kuchler A, Alpar D, Bock C (2017) Pooled CRISPR screening with single‐cell transcriptome readout. Nat Methods 14: 297–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David R, Burgess A, Parker B, Li J, Pulsford K, Sibbritt T, Preiss T, Searle IR (2017) Transcriptome‐wide mapping of RNA 5‐methylcytosine in Arabidopsis mRNAs and noncoding RNAs. Plant Cell 29: 445–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit A, Parnas O, Li B, Chen J, Fulco CP, Jerby‐Arnon L, Marjanovic ND, Dionne D, Burks T, Raychowdhury R et al (2016) Perturb‐Seq: dissecting molecular circuits with scalable single‐cell RNA profiling of pooled genetic screens. Cell 167: 1853–1866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini D, Nachtergaele S, Moshitch‐Moshkovitz S, Peer E, Kol N, Ben‐Haim MS, Dai Q, Di Segni A, Salmon‐Divon M, Clark WC, Zheng G, Pan T, Solomon O, Eyal E, Hershkovitz V, Han D, Dore LC, Amariglio N, Rechavi G, He C (2016) The dynamic N(1)‐methyladenosine methylome in eukaryotic messenger RNA. Nature 530: 441–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelheit S, Schwartz S, Mumbach MR, Wurtzel O, Sorek R (2013) Transcriptome‐wide mapping of 5‐methylcytidine RNA modifications in bacteria, archaea, and yeast reveals m5C within archaeal mRNAs. PLoS Genet 9: e1003602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guallar D, Bi X, Pardavila JA, Huang X, Saenz C, Shi X, Zhou H, Faiola F, Ding J, Haruehanroengra P et al (2018) RNA‐dependent chromatin targeting of TET2 for endogenous retrovirus control in pluripotent stem cells. Nat Genet 50: 443–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag S, Warda AS, Kretschmer J, Gunnigmann MA, Hobartner C, Bohnsack MT (2015) NSUN6 is a human RNA methyltransferase that catalyzes formation of m5C72 in specific tRNAs. RNA 21: 1532–1543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna RE, Doench JG (2020) Design and analysis of CRISPR‐Cas experiments. Nat Biotechnol 38: 813–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauenschild R, Tserovski L, Schmid K, Thuring K, Winz ML, Sharma S, Entian KD, Wacheul L, Lafontaine DL, Anderson J et al (2015) The reverse transcription signature of N‐1‐methyladenosine in RNA‐Seq is sequence dependent. Nucleic Acids Res 43: 9950–9964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm M (2006) Post‐transcriptional nucleotide modification and alternative folding of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 34: 721–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T, Chen W, Liu J, Gu N, Zhang R (2019) Genome‐wide identification of mRNA 5‐methylcytosine in mammals. Nat Struct Mol Biol 26: 380–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S, Sajini AA, Blanco S, Dietmann S, Lombard P, Sugimoto Y, Paramor M, Gleeson JG, Odom DT, Ule J et al (2013) NSun2‐mediated cytosine‐5 methylation of vault noncoding RNA determines its processing into regulatory small RNAs. Cell Rep 4: 255–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoddami V, Cairns BR (2013) Identification of direct targets and modified bases of RNA cytosine methyltransferases. Nat Biotechnol 31: 458–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, Salzberg SL (2019) Graph‐based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT‐genotype. Nat Biotechnol 37: 907–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL (2012) Fast gapped‐read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9: 357–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Li X, Tang H, Jiang B, Dou Y, Gorospe M, Wang W (2017a) NSUN2‐mediated m5C methylation and METTL3/METTL14‐mediated m6A methylation cooperatively enhance p21 translation. J Cell Biochem 118: 2587–2598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Xiong X, Zhang M, Wang K, Chen Y, Zhou J, Mao Y, Lv J, Yi D, Chen XW et al (2017b) Base‐resolution mapping reveals distinct m(1)A methylome in nuclear‐ and mitochondrial‐encoded transcripts. Mol Cell 68: 993–1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Li H, Long T, Dong H, Wang ED, Liu RJ (2019) Archaeal NSUN6 catalyzes m5C72 modification on a wide‐range of specific tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 47: 2041–2055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder B, Grozhik AV, Olarerin‐George AO, Meydan C, Mason CE, Jaffrey SR (2015) Single‐nucleotide‐resolution mapping of m6A and m6Am throughout the transcriptome. Nat Methods 12: 767–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Feng J, Xu Q, Wang W, Wang X (2016) NSun2 deficiency protects endothelium from inflammation via mRNA methylation of ICAM‐1. Circ Res 118: 944–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machnicka MA, Milanowska K, Osman Oglou O, Purta E, Kurkowska M, Olchowik A, Januszewski W, Kalinowski S, Dunin‐Horkawicz S, Rother KM et al (2013) MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways–2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res 41: D262–D267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M (2011) Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high‐throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal 17: 10 [Google Scholar]

- Roundtree IA, Evans ME, Pan T, He C (2017) Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell 169: 1187–1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safra M, Sas‐Chen A, Nir R, Winkler R, Nachshon A, Bar‐Yaacov D, Erlacher M, Rossmanith W, Stern‐Ginossar N, Schwartz S (2017) The m1A landscape on cytosolic and mitochondrial mRNA at single‐base resolution. Nature 551: 251–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M, Pollex T, Hanna K, Lyko F (2009) RNA cytosine methylation analysis by bisulfite sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res 37: e12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann U, Zhang HN, Sibbritt T, Pan A, Horvath A, Gross S, Clark SJ, Yang L, Preiss T (2020) Multiple links between 5‐methylcytosine content of mRNA and translation. BMC Biol 18: 40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q, Zhang Q, Shi Y, Shi Q, Jiang Y, Gu Y, Li Z, Li X, Zhao K, Wang C et al (2018) Tet2 promotes pathogen infection‐induced myelopoiesis through mRNA oxidation. Nature 554: 123–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires JE, Patel HR, Nousch M, Sibbritt T, Humphreys DT, Parker BJ, Suter CM, Preiss T (2012) Widespread occurrence of 5‐methylcytosine in human coding and non‐coding RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 5023–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trixl L, Lusser A (2019) Getting a hold on cytosine methylation in mRNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol 26: 339–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagih O (2017) ggseqlogo: a versatile R package for drawing sequence logos. Bioinformatics 33: 3645–3647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Li Y, Toth JI, Petroski MD, Zhang Z, Zhao JC (2014) N6‐methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 16: 191–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler EC, Vu AQ, Einstein JM, DiSalvo M, Ahmed N, Van Nostrand EL, Shishkin AA, Jin W, Allbritton NL, Yeo GW (2020) Pooled CRISPR screens with imaging on microraft arrays reveals stress granule‐regulatory factors. Nat Methods 17: 636–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Wang Y, Tang Q, Wei L, Zhang X, Jia G (2018) An elongation‐ and ligation‐based qPCR amplification method for the radiolabeling‐free detection of locus‐specific N(6) ‐methyladenosine modification. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 57: 15995–16000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X, Stuurman N, Ribeiro SA, Tanenbaum ME, Horlbeck MA, Liem CR, Jost M, Weissman JS, Vale RD (2020) High‐content imaging‐based pooled CRISPR screens in mammalian cells. bioRxiv 10.1101/2020.06.30.179648 [PREPRINT] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Yang Y, Sun B‐F, Chen Y‐S, Xu J‐W, Lai W‐Y, Li A, Wang X, Bhattarai DP, Xiao W et al (2017) 5‐methylcytosine promotes mRNA export ‐ NSUN2 as the methyltransferase and ALYREF as an m(5)C reader. Cell Res 27: 606–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao LY, Song J, Liu Y, Song CX, Yi C (2020) Mapping the epigenetic modifications of DNA and RNA. Protein Cell 11: 792–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expanded View Figures PDF

Dataset EV1

Dataset EV2

Dataset EV3

Review Process File

Data Availability Statement

All next‐generation sequencing data were submitted to Gene Expression Omnibus under the accession number GSE157368 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE157368).