Abstract

Objectives

Work-related lung diseases (WRLDs) are entirely preventable. To assess the impact of WRLDs on the US transplant system, we identified adult lung transplant recipients with a WRLD diagnosis specified at the time of transplant to describe demographic, payer and clinical characteristics of these patients and to assess post-transplant survival.

Methods

Using US registry data from 1991 to 2018, we identified lung transplant recipients with WRLDs including coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, silicosis, asbestosis, metal pneumoconiosis and berylliosis.

Results

The frequency of WRLD-associated transplants has increased over time. Among 230 lung transplants for WRLD, a majority were performed since 2009; 79 were for coal workers’ pneumoconiosis and 78 were for silicosis. Patients with coal workers’ pneumoconiosis were predominantly from West Virginia (n=31), Kentucky (n=23) or Virginia (n=10). States with the highest number of patients with silicosis transplant were Pennsylvania (n=12) and West Virginia (n=8). Patients with metal pneumoconiosis and asbestosis had the lowest and highest mean age at transplant (48.8 and 62.1 years). Median post-transplant survival was 8.2 years for patients with asbestosis, 6.6 years for coal workers’ pneumoconiosis and 7.8 years for silicosis. Risk of death among patients with silicosis, coal workers’ pneumoconiosis and asbestosis did not differ when compared with patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Conclusions

Lung transplants for WRLDs are increasingly common, indicating a need for primary prevention and surveillance in high-risk occupations. Collection of patient occupational history by the registry could enhance case identification and inform prevention strategies.

INTRODUCTION

The role of workplace exposures in the development and exacerbation of lung diseases has been acknowledged for centuries.1 Work-related lung disease (WRLD), including but not limited to the pneumoconioses, can be severe and life-threatening and may continue to progress in the absence of further exposure.2 For some patients with WRLD, lung transplantation becomes the therapeutic option of last resort.3 Unlike many other indications for lung transplantation, WRLDs are entirely preventable through proper use of environmental, administrative and/or respiratory protection controls. Effective exposure prevention and medical monitoring programmes in high-risk industries are key for prevention, but many patients have already progressed to end-stage WRLD for which the only effective remaining intervention is a lung transplant. Lung transplantation incurs surgical and medical risk, most significantly in the form of post-procedural resistant infections and graft failure or rejection. The procedure also requires significant social support and may be a financial burden on patients and their families, which can be prohibitive to placing a potential recipient on a transplant waitlist.4 Additionally, being listed for transplantation is not a guarantee of an organ offer, as there is a shortage of acceptable donors.

In recent years, data from the US population-based Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) registry have been used to estimate post-transplant survival in patients with WRLD, with most studies focusing on silicosis or coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (CWP).5–8 For case identification within the registry, these studies have generally relied on an occupational lung disease code that is inconsistently applied; use of this code will underestimate the frequency of lung transplantation for WRLDs,9 which could bias summary measures such as post-transplant survival. Accurate and comprehensive accounting of WRLDs is vital and has implications for organ allocation and for transplant centre willingness to perform lung transplants in patient populations deemed higher risk. Using national registry data, we identified adult lung transplant recipients with a WRLD diagnosis specified at the time of transplant to describe demographic, payer and clinical characteristics of these patients and to assess post-transplant survival.

METHODS

We received deidentified OPTN patient data for thoracic organ transplants performed in the USA during January 1991–December 2018, and restricted analysis to 37 089 unilateral and bilateral lung transplants performed for recipients aged ≥18 years. Although OPTN patient data include both numeric and free-text entries for the listing diagnosis, we queried all free-text diagnoses to increase the sensitivity of case finding, as described previously.9 Free-text entries are specifically requested when numeric codes for the following diagnosis categories are selected: occupational lung disease other specify, congenital: other specify, pulmonary fibrosis other specify cause, lung disease: other specify and other—specify, and are optional for other numeric diagnosis codes. We reviewed each free-text diagnosis to identify patients with WRLDs, including cases for which the population attributable risk for work-relatedness is ~100% (eg, CWP and silicosis),10 and cases for which work-relatedness was specified through combination of a free-text diagnosis and a numeric code (eg, ‘chlorine gas exposure’ with the occupational lung disease code or ‘occupational lung disease’ with the pulmonary fibrosis code).

Cases were assigned to six categories: silicosis, CWP, asbestosis, metal pneumoconiosis, berylliosis and a single category inclusive of other WRLDs (bagassosis, occupational farmer’s lung, unspecified occupational hypersensitivity pneumonitis, occupational bronchiolitis obliterans, occupational lung disease from high-intensity exposures and non-specific occupational lung diseases). Lung allocation score (LAS), a summary value used to assign relative priority for transplantation in the USA, was calculated for registry patients beginning in 2005.11 We summarised patient characteristics, including LAS, and payment source for transplant-associated medical expenses and characterised the frequency of adult lung transplants for WRLDs and overall. We used a Kaplan-Meier estimator and Cox proportional hazards models, adjusting for patient age at transplantation and transplant type (unilateral vs bilateral) to compare post-transplant survival among patients with WRLD with a group of adult males with a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) with no indication of occupational attribution who received a lung transplant during the same time period. Analysis of the available data, including descriptive statistics and Cox proportional hazard modelling, was conducted using SAS V.9.4 (Cary, North Carolina, USA).

RESULTS

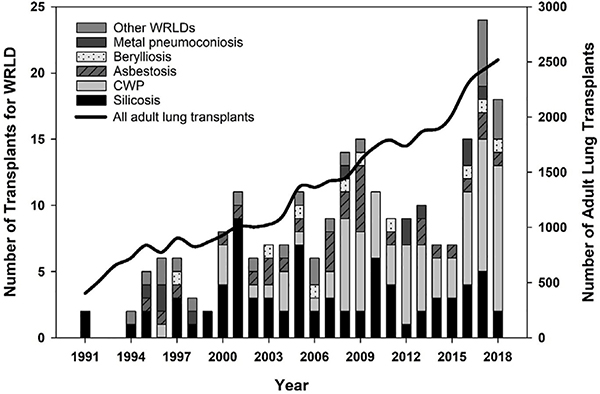

We identified 230 lung transplants for WRLD performed in the USA, accounting for 0.6% of adult lung transplants during the 28-year study period (figure 1). The majority (54%) of WRLD-related transplants were performed during 2009–2018. Nearly all WRLD transplant recipients were males (97%), compared with 56% of recipients with other indications. A total of 202 (88%) WRLD transplant recipients were Caucasian, 7 (3%) were black and 17 (7%) were Hispanic. On average, WRLD transplant recipients spent less time on the waitlist compared with other adults (mean=171 days vs 249 days). Other demographic and clinical characteristics of WRLD transplant recipients were comparable to those for the overall adult lung transplant recipient population. Mean age of WRLD transplant recipients was 55.6 years, mean body mass index was 25.4, mean per cent of predicted forced expiratory volume in the 1 s (FEV1%) was 37.6, mean per cent of predicted forced vital capacity (FVC%) was 49.4 and 142 (62%) received a bilateral lung transplant.

Figure 1.

Frequency of lung transplantation in adult patients with work-related lung disease (WRLD) and overall, USA, 1991–2018. CWP, coal workers’ pneumoconiosis.

Table 1 summarises patient characteristics by WRLD category. A total of 157 (68%) of the transplants in this category were for CWP or silicosis. Recipients with metal pneumoconiosis had the lowest mean age at the time of transplant (48.8 years), and patients with asbestosis had the highest (62.1 years). Recipients with silicosis had the lowest mean FEV1% (29.4), while those with metal pneumoconiosis had the lowest mean FVC% (35.6). Recipients with berylliosis had the shortest waitlist time (mean=90 days), and those with silicosis had the longest (mean=216 days). Asbestosis and metal pneumoconiosis were the only categories in which less than half of patients received a bilateral lung transplant. Mean initial calculated LAS for lung transplant recipients with WRLD was as follows: asbestosis (41.6), berylliosis (45.5), CWP (41.8), metal pneumoconiosis (47.8), silicosis (44.9) and other WRLDs (54.0).

Table 1.

Characteristics of lung transplant recipients with WRLD, USA, 1991–2018

| CWP (n=79) | Silicosis (n=78) | Asbestosis (n=29) | Metal pneum. (n=11) | Berylliosis (n=10) | Other WRLDs* (n=23) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years | 57.7±6.0 | 52.4±9.5 | 62.1±5.8 | 48.8±10.0 | 57.7±6.3 | 53.1±12.4 |

| Male sex (%) | 79 (100) | 76 (97.4) | 29 (100) | 10 (90.9) | 8 (80.0) | 22 (95.7) |

| BMI | 25.3±4.6 | 24.3±4.5 | 28.2±3.4 | 23.9±4.5 | 27.5±4.0 | 26.2±4.6 |

| FEV1 % | 38.5±20.8 | 29.4±11.2 | 51.3±19.7 | 37.2±11.4 | 49.5±19.5 | 40.8±18.9 |

| FVC % | 53.4±15.6 | 46.2±17.7 | 51.6±21.2 | 35.6±10.5 | 59.9±17.3 | 46.5±15.3 |

| Days on WL | 148±158 | 216±252 | 160±247 | 166±208 | 90±116 | 152±219 |

| Bilateral LT (%) | 56 (70.9) | 47 (60.3) | 10 (34.5) | 5 (45.5) | 7 (77.8) | 17 (73.9) |

Other category includes: bagassosis, occupational farmer’s lung, unspecified occupational hypersensitivity pneumonitis, occupational bronchiolitis obliterans, occupational lung disease from high-intensity exposures (including chlorine gas, ammonia, insecticide and sulfuric acid) and non-specific occupational lung diseases.

BMI, body mass index; CWP, coal workers’ pneumoconiosis; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; LT, lung transplant; metal pneum., hard metal pneumoconiosis; WL, waitlist; WRLD, work-related lung disease.

Eighty-one per cent of lung transplants for CWP were performed for patients residing in the Appalachian states of West Virginia (n=31), Kentucky (n=23) and Virginia (n=10). The states with the highest number of silicosis transplant patients were Pennsylvania (n=12), West Virginia (n=8) and Wisconsin (n=5). Public insurance was the primary payment source for approximately half (n=115) of the patients with WRLD; two-thirds of these were covered by Medicare (table 2). More than one-quarter (n=21) of patients with CWP had ‘Other government insurance’ listed as the primary payer. Private insurance was listed as primary payer for 43%–57% of lung transplants in each WRLD category, except for CWP (32%).

Table 2.

Primary source of payment for medical expenses associated with lung transplantation for WRLDs, USA, 1991–2018

| CWP | Silicosis | Asbestosis | Metal pneum. | Berylliosis | Other WRLDs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public insurance | 52 (66.7) | 26 (34.7) | 16 (57.1) | 6 (54.5) | 5 (50.0) | 10 (43.5) |

| Medicaid | 0 (0) | 3 (4.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Medicare | 30 (38.5) | 18 (24.0) | 14 (50.0) | 5 (45.5) | 2 (20.0) | 10 (43.5) |

| Veterans affairs | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0) |

| Other government insurance | 21 (26.9) | 4 (5.3) | 2 (7.1) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (20.0) | 0 (0) |

| Private insurance | 25 (32.1) | 42 (56.0) | 12 (42.9) | 5 (45.5) | 5 (50.0) | 13 (56.5) |

| US/state agency | 1 (1.3) | 6 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Free care or self-pay | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 78* (100) | 75* (100) | 28* (100) | 11 (100) | 10 (100) | 23 (100) |

Data are n (%).

Missing payer data for CWP (n=1), silicosis (n=3) and asbestosis (n=1).

*Other category includes: bagassosis, occupational farmer’s lung, unspecified occupational hypersensitivity pneumonitis, occupational bronchiolitis obliterans, occupational lung disease from high intensity exposures (including chlorine gas, ammonia, insecticide and sulfuric acid) and non-specific occupational lung diseases.

CWP, coal workers’ pneumoconiosis; metal pneum., hard metal pneumoconiosis; WRLDs, work-related lung diseases.

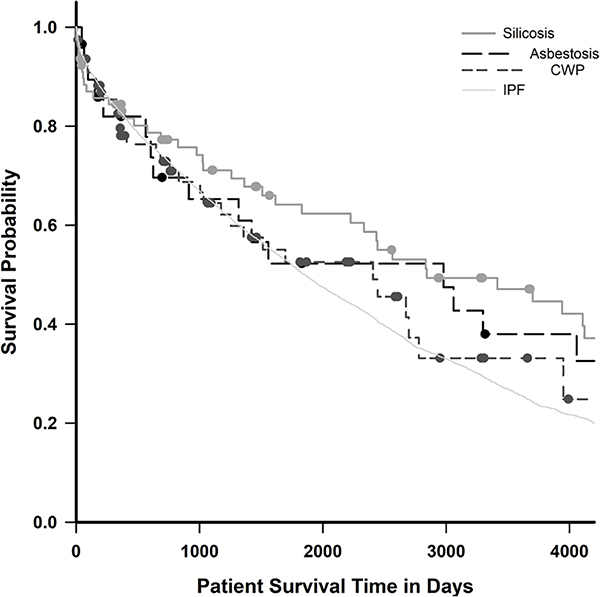

Figure 2 displays post-lung transplant survival for recipients with asbestosis, CWP, silicosis and a referent group of 7677 adult males with IPF. Recipients with metal pneumoconiosis, berylliosis and those in the ‘other’ category were excluded from survival analysis due to small sample size. One-year and 3-year survival for lung transplant recipients with silicosis was 84% and 71%, with IPF was 83% and 65%, with asbestosis was 82% and 65% and with CWP was 78% and 65%, respectively. Median post-transplant survival was 8.2 years (SE=3.3) for asbestosis, 6.6 years (SE=1.7) for CWP, 7.8 years (SE=2.1) for silicosis and 5.1 years (SE=0.1) for IPF (log-rank test, p=0.027). Using a pairwise multiple comparison test (Holm-Sidak method) to assess for differences between individual survival curves, the silicosis versus IPF comparison was the only statistically significant pairing (p=0.022).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier function, post-lung transplant survival by work-related lung disease, compared with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), USA, 1991–2018. CWP, coal workers’ pneumoconiosis.

Table 3 displays the results of crude and adjusted Cox models for hazard comparisons by patient group. Recipient age and transplant type (single vs bilateral) were independently associated with survival and were included in the adjusted model. In the crude model, silicosis was the only category with lower risk of death during follow-up compared with IPF (HR=0.64; 95% CI 0.47 to 0.87). However, after adjusting for age and transplant type, the risk of death among transplant recipients with silicosis, CWP and asbestosis did not differ significantly when compared with recipients diagnosed with IPF. Relative to patients with IPF, the silicosis group had an adjusted HR of 0.75 (95% CI 0.56 to 1.02).

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazard models, time-to-death for lung transplant recipients by thoracic diagnosis, USA, 1991–2018

| Crude |

Adjusted |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| CWP | 0.937 | 0.672 to 1.307 | 1.064 | 0.763 to 1.485 |

| Silicosis | 0.641 | 0.474 to 0.866 | 0.750 | 0.555 to 1.015 |

| Asbestosis | 0.834 | 0.531 to 1.310 | 0.768 | 0.489 to 1.207 |

| IPF | Referent | Referent | ||

| Age (years) | 1.020 | 1.016 to 1.024 | 1.015 | 1.011 to 1.019 |

| Transplant type | ||||

| Single | 1.510 | 1.418 to 1.608 | 1.426 | 1.337 to 1.520 |

| Bilateral | Referent | Referent | ||

Adjusted model includes covariates for recipient age at time of transplantation and transplant type (single vs bilateral)

CWP, coal workers’ pneumoconiosis; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

DISCUSSION

Using national registry data, we identified 230 patients receiving lung transplants for WRLDs during 1991–2018, with most occurring in the last decade. Recent reports have described an increase in the frequency and rate of lung transplantation for CWP,12,13 but trends for other WRLDs have not previously been reported. Although CWP has displaced silicosis as the most common indication for WRLD-associated transplantation, lung transplants for asbestosis, berylliosis, silicosis, metal pneumoconiosis and other WRLDs continue to occur, indicating a need for primary prevention and medical monitoring in worker populations at risk for these conditions.

Associations between WRLDs and industries including mining, sandblasting, construction and insulation work have been well-described.14 However, understanding classic exposure and disease relationships does not guarantee ongoing control of WRLDs such as CWP, silicosis and asbestosis, and evolving work practices or regulatory changes can have public health consequences. Following decades of decline, the prevalence of severe pneumoconiosis in underground coal miners in the USA has reached an all-time high. 15 International demand for metallurgic coal has likely incentivised mining practices in Appalachia including thin-seam coal mining and ‘slope’ development, which involves cutting through pure rock with equipment designed to cut coal. In this region, there has been a sixfold increase since 1980 in the prevalence of a radiographic pattern associated with crystalline silica.16 Studies of these coal miners have identified high-exposure jobs that involve cutting or drilling at the mining face.17,18 A recent case series on work practices of coal miners with severe pneumoconiosis described the use of continuous miner machines to cut sandstone, which contains high levels of crystalline silica, for months at a time.19 The incidence of asbestos-related lung disease has declined as a result of reductions in the commercial of asbestos in the USA. A rule released in 2019 by the Environmental Protection Agency allows for continued use of asbestos in domestic manufacturing, renewed asbestos mining to support these uses and importation of asbestos into the USA.20,21 The rule also includes a process to seek approval for new domestic uses of asbestos. The effects of this rule have yet to be realised; however, there is no safe level of asbestos exposure.22

Worker exposures in emerging industries might also cause new WRLD cases. Multiple reports of engineered stone-associated silicosis, primarily among workers fabricating countertops, underscore the potential for emerging outbreaks of WRLDs.23–31 In a recent Israeli study spanning 13 years, 10 of 25 patients with silicosis associated with occupational exposure to dust from engineered stone products received lung transplants.29 Until recently, one case of engineered stone silicosis had been described in the USA.27 A 2019 report identified 18 additional cases in four states, primarily among younger Hispanic workers.26 The US engineered stone industry has approximately 96 000 workers and has experienced an 800% increase in countertop imports since 2010. National requirements for medical monitoring of silica-exposed workers have only recently been established, and most workers have never been screened, so the true burden of silicosis is surely larger than what has been reported.32 Australia’s recent experience might foreshadow ours: following reports of silicosis in engineered stone workers, the Queensland government initiated medical screening and identified 98 (12%) cases of silicosis among 799 workers.33 In light of the domestic growth of unconventional natural gas development, silica exposure during hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas well development has been identified as an emerging risk. A study of full-shift personal breathing zone samples from workers at 11 US hydraulic fracturing sites in five states identified respirable crystalline silica concentrations greater than 10 times the relevant occupational exposure criteria.34 Because of latency issues for diseases like silicosis, work practices with documented potential for high exposures merit attention because cumulative exposures might not manifest as lung disease for years.

The average cost of a bilateral lung transplant in the USA is US$1.2 million.35 More than 50% of WRLD transplants described in this report were paid for with public insurance, primarily Medicare or ‘Other government insurance’. For patients with CWP, ‘Other government insurance’ presumably refers to the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund, which covers medical expenses when a responsible coal mine operator does not meet its obligations to pay benefits to disabled miners. As a result of a recent tax cut for coal operators, declining domestic coal production and interest payments for past borrowing from the Treasury, the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund faces significant challenges. Currently, the Trust Fund is US$4.2 billion in debt, and a moderate case projection by the Government Accountability Office estimates a debt of US$15.4 billion by 2050.36 If the number of lung transplants for CWP continues to increase, it would place additional strain on the Trust Fund.

Few registry-based studies have focused on lung transplants specifically for patients with WRLD. Two studies used OPTN data to compare survival in lung transplant recipients with silicosis with that of other WRLDs and lung diseases not attributed to workplace exposures.7,8 Singer et al found that patients receiving a lung transplant for non-silicosis WRLDs initially experienced higher mortality compared with recipients with silicosis and to recipients with other indications, but this difference attenuated 1 year post-transplantation.8 Hayes and colleagues replicated Singer’s methods, adding approximately 3 years of data and follow-up, and did not observe increased mortality among patients with WRLD with and without silicosis compared with all other lung transplant recipients.7 Enfield and colleagues examined post-transplant survival in patients with CWP and reported significantly higher mortality among patients with CWP compared with those with silicosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and IPF.5 Each of these studies likely underestimated the number of WRLDs by relying on preselected diagnosis codes to identify WRLD cases, without incorporating information from associated free-text fields. While accounting for age and transplant type, we found that survival among patients with silicosis, CWP or asbestosis did not differ significantly when compared with patients with IPF. Lung transplant recipients with silicosis had a modest survival advantage in the crude analysis, and a slightly higher 3-year survival rate, but this benefit diminished in the adjusted model.

This study focused on respiratory diseases caused solely by workplace exposures and therefore likely underestimated the true number of lung transplants performed for patients with a work-related contribution to their lung disease. A review by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) determined that occupational exposures account for 10% to 20% of the overall prevalence of COPD.37 A multicentre study by Paulin and colleagues found that among patients with COPD, a history of workplace exposure was associated with lower quality of life, worse symptoms, more dyspnoea and shorter 6-min walk distance.38 Similarly, 26% of IPF cases are estimated to be attributable to occupational exposures.39 The ability to establish a workplace (or non-workplace) aetiology for conditions such as COPD and IPF will probably not alter clinical management, but this knowledge could offer insight into new or existing work practices leading to disease, for which preventive interventions could be developed. In 2013, ATS re-emphasised the importance of obtaining an occupational history from patients with COPD,40 and a diagnosis of IPF should include a presumption that known aetiologies, such as occupational exposures, have been ruled out.

Registry data are collected primarily to facilitate safe and efficient organ sharing, not for public health surveillance. It is possible that certain transplant centres are more likely than others to collect occupational histories from patients and to apply the occupational lung disease code when recording data for the registry, which could result in differential misclassification. We focused on respiratory conditions caused solely by occupational exposures and therefore underestimated the total number of lung transplants performed for patients with work-related contributions to their underlying lung disease. We narrowly defined WRLD and did not include conditions possibly related to occupational exposures (eg, ammonia exposure). In addition, we did not include patients with free-text diagnoses of conditions that can sometimes arise from occupational exposures, such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis and COPD.

More than 300 years ago, the physician Ramazzini noted the importance of knowing and understanding a patient’s occupation; this knowledge is paramount for identifying risk factors and for preventing future cases. The frequency of lung transplants for conditions that are entirely preventable is rising. Donor lungs are a precious resource. Unlike diseases with genetic aetiologies, WRLDs are entirely preventable. Inclusion of occupational information in the registry would be helpful, but prevention of harmful exposures and detection of disease at an earlier stage, when interventions less drastic than lung transplantation are still possible, is even more imperative.

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Work-related lung disease (WRLD), including but not limited to the pneumoconioses, can be severe and life-threatening and may continue to progress in the absence of further exposure. For some patients with WRLD, lung transplantation becomes the therapeutic option of last resort.

What are the new findings?

Using national registry data, we identified 230 patients receiving lung transplants for WRLDs during 1991–2018, with most occurring in the last decade.

How might this impact on policy or clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Collection of patient occupational history by the registry could enhance case identification and inform prevention strategies.

Acknowledgments

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Disclaimer The content of this manuscript is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control andPrevention, or the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Ethics approval The NIOSH Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that this study did not require IRB review, and activities were covered by a signed data use agreement with the United Network for Organ Sharing.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The data reported here have been supplied by the United Network for Organ Sharing as the contractor for the OPTN. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and should not be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the OPTN or the US Government. These data are available on request with a signed data use agreement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ramazzini B De morbis artificum diatriba [diseases of workers]. 1713. Am J Public Health 2001;91:1380–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mason RJ, Broaddus VC, Martin T, et al. Murray and Nadel’s textbook of respiratory medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartert M, Senbaklavacin O, Gohrbandt B, et al. Lung transplantation: a treatment option in end-stage lung disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014;111:107–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolaitis NA, Singer JP. Defining success in lung transplantation: from survival to quality of life. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2018;39:255–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enfield KB, Floyd S, Barker B, et al. Survival after lung transplant for coal workers’ pneumoconiosis. J Heart Lung Transplant 2012;31:1315–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enfield KB, Floyd S, Peach P, et al. Transplant outcome for coal workers pneumoconiosis. San Diego, CA: American Transplant Congress, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayes D, Hayes KT, Hayes HC, et al. Long-Term survival after lung transplantation in patients with silicosis and other occupational lung disease. Lung 2015;193:927–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singer JP, Chen H, Phelan T, et al. Survival following lung transplantation for silicosis and other occupational lung diseases. Occup Med 2012;62:134–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blackley DJ, Halldin CN, Cohen RA, et al. Misclassification of occupational disease in lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017;36:588–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leigh JP, Robbins JA. Occupational disease and workers’ compensation: coverage, costs, and consequences. Milbank Q 2004;82:689–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shweish O, Dronavalli G. Indications for lung transplant referral and listing. J Thorac Dis 2019;11:S1708–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackley DJ, Halldin CN, Cummings KJ, et al. Lung transplantation is increasingly common among patients with coal workers’ pneumoconiosis. Am J Ind Med 2016;59:175–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blackley DJ, Halldin CN, Laney AS. Continued increase in lung transplantation for coal workers’ pneumoconiosis in the United States. Am J Ind Med 2018;61:621–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Matteis S, Heederik D, Burdorf A, et al. Current and new challenges in occupational lung diseases. Eur Respir Rev 2017;26:170080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blackley DJ, Halldin CN, Laney AS. Continued increase in prevalence of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis in the United States, 1970–2017. Am J Public Health 2018;108:1220–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall NB, Blackley DJ, Halldin CN, et al. Continued increase in prevalence of R-type opacities among underground coal miners in the USA. Occup Environ Med 2019;76:479–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blackley DJ, Reynolds LE, Short C, et al. Progressive massive fibrosis in coal miners from 3 clinics in Virginia. JAMA 2018;319:500–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blackley DJ, Crum JB, Halldin CN, et al. Resurgence of Progressive Massive Fibrosis in Coal Miners - Eastern Kentucky, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1385–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds LE, Blackley DJ, Colinet JF, et al. Work practices and respiratory health status of Appalachian coal miners with progressive massive fibrosis. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2018;60:e575–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landrigan PJ, Lemen RA. A Most Reckless Proposal - A Plan to Continue Asbestos Use in the United States. N Engl J Med 2019;381:598–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.In: Environmental Protection Agency, ed. Restrictions on discontinued uses of asbestos; significant new use rule, 2019.

- 22.Lanphear BP. Low-Level toxicity of chemicals: no acceptable levels? PLoS Biol 2017;15:e2003066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iavicoli I, Leso V, Piacci M, et al. An exploratory assessment of applying risk management practices to engineered nanomaterials. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoy RF, Baird T, Hammerschlag G, et al. Artificial stone-associated silicosis: a rapidly emerging occupational lung disease. Occup Environ Med 2018;75:3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosengarten D, Fox BD, Fireman E, et al. Survival following lung transplantation for artificial stone silicosis relative to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Ind Med 2017;60:248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rose C, Heinzerling A, Patel K, et al. Severe Silicosis in Engineered Stone Fabrication Workers - California, Colorado, Texas, and Washington, 2017–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:813–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman GK, Harrison R, Bojes H, et al. Notes from the field: silicosis in a countertop fabricator - Texas, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:129–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grubstein A, Shtraichman O, Fireman E, et al. Radiological evaluation of artificial stone silicosis outbreak. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2016;40:923–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kramer MR, Blanc PD, Fireman E, et al. Artificial stone silicosis [corrected]: disease resurgence among artificial stone workers. Chest 2012;142:419–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pascual Del Pobil Y Ferré MA, García Sevila R, García Rodenas MDM, et al. Silicosis: a former occupational disease with new occupational exposure scenarios. Rev Clin Esp 2019;219:26–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ronsmans S, Decoster L, Keirsbilck S, et al. Artificial stone-associated silicosis in Belgium. Occup Environ Med 2019;76:133–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casey ML, Mazurek JM. Silicosis prevalence and incidence among Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Ind Med 2019;62:183–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirby T Australia reports on audit of silicosis for stonecutters. Lancet 2019;393:861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Esswein EJ, Breitenstein M, Snawder J, et al. Occupational exposures to respirable crystalline silica during hydraulic fracturing. J Occup Environ Hyg 2013;10:347–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bentley T, Phillips S. 2017 us organ and tissue transplant cost estimates and discussion 2017.

- 36.United States Government Accountability Office. Black lung benefits program, financing and oversight challenges are adversely affecting the trust fund, 2019.

- 37.Balmes J, Becklake M, Blanc P, et al. American Thoracic Society statement: occupational contribution to the burden of airway disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paulin LM, Diette GB, Blanc PD, et al. Occupational exposures are associated with worse morbidity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:557–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blanc PD, Annesi-Maesano I, Balmes JR, et al. The occupational burden of nonmalignant respiratory diseases. An official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019;199:1312–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarlo SM, Malo J-L, Fourth Jack Pepys Workshop on Asthma in the Workplace Participants. An official American Thoracic Society proceedings: work-related asthma and airway diseases. presentations and discussion from the fourth jack Pepys workshop on asthma in the workplace. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2013;10:S17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The data reported here have been supplied by the United Network for Organ Sharing as the contractor for the OPTN. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and should not be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the OPTN or the US Government. These data are available on request with a signed data use agreement.