Abstract

Nitrogenase is the enzyme that catalyzes biological N2 reduction to NH3. This enzyme achieves an impressive rate enhancement over the uncatalyzed reaction. Given the high demand for N2 fixation to support food and chemical production and the heavy reliance of the industrial Haber–Bosch nitrogen fixation reaction on fossil fuels, there is a strong need to elucidate how nitrogenase achieves this difficult reaction under benign conditions as a means of informing the design of next generation synthetic catalysts. This Review summarizes recent progress in addressing how nitrogenase catalyzes the reduction of an array of substrates. New insights into the mechanism of N2 and proton reduction are first considered. This is followed by a summary of recent gains in understanding the reduction of a number of other nitrogenous compounds not considered to be physiological substrates. Progress in understanding the reduction of a wide range of C-based substrates, including CO and CO2, is also discussed, and remaining challenges in understanding nitrogenase substrate reduction are considered.

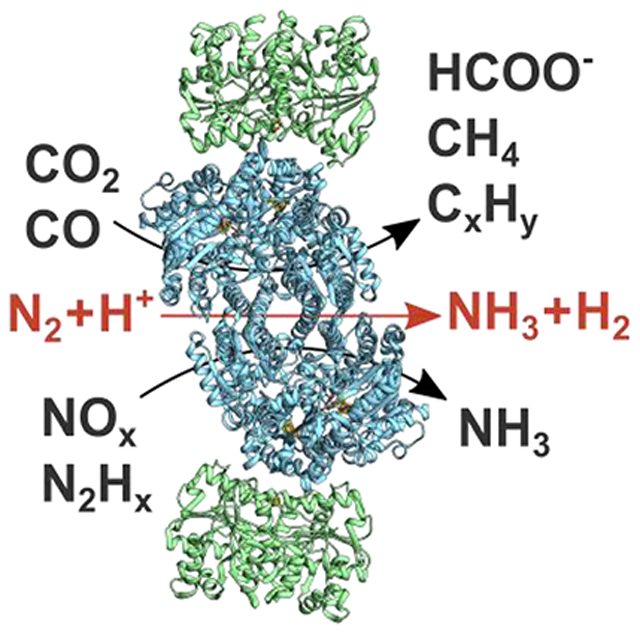

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

The element nitrogen (N) is a constituent of many industrially and biologically important molecules, and thus there is a high worldwide demand for usable forms of N.1–4 The major simple molecular states of N constitute the global biogeochemical nitrogen cycle, with dinitrogen (N2) being the most abundant form constituting 78% of the Earth’s atmosphere.5–10 While abundant, N2 is not generally useable directly but instead must first be “fixed” into a form that is useful for industrial or biological processes.1,2,11,12 The reduction of N2 to NH3, called nitrogen fixation, is the largest contributor of fixed nitrogen into the global N cycle. This reduction reaction occurs at scale in comparable amounts through two processes, the Haber–Bosch industrial reaction13–15 and by the action of the enzyme nitrogenase operating inside specialized microorganisms, called diazotrophs, found throughout the biosphere.11,16–18 Nitrogenase catalyzes the N2 reduction reaction having the following optimal (limiting) stoichiometry:19–23

| (1) |

As indicated by eq 1, N2 reduction by nitrogenase is fundamentally an electrochemical process, employing electrons and protons. In that sense, it differs qualitatively from the chemical industrial Haber–Bosch process, which employs H2 as the source of reducing equivalents and H (eq 2):3

| (2) |

The nitrogenase catalyzed reaction requires energy input in the form of hydrolysis of ATP, whereas 90% of the energy input for the Haber–Bosch process is used to make the H2 reactant from methane24 (eq 3)

| (3) |

Finally, the nitrogenase stoichiometry (eq 1) incorporates the obligatory production of one H2 per N2 reduced, a long-debated idea that has been established only recently.21,23

Enzyme-catalyzed reactions, like all catalyzed reactions, are often measured by the rate enhancement achieved over the uncatalyzed reaction.25–27 Although nitrogenase catalyzes the reduction of N2 to 2 NH3 with a seemingly low rate constant of ~1 s−1,19,20,28,29 this corresponds to a large enhancement over the uncatalyzed reaction that places it as one of the most impressive known catalysts.

Research on nitrogenase over decades has endeavored to understand this complex enzyme and elucidate the mechanism by which this remarkable catalyst achieves its rate enhancement.20,21,23,30–37 Other reviews in this volume detail diverse aspects of how nitrogenase works, including how electron transfer occurs and the roles of ATP hydrolysis, how spectroscopy provides insights into the properties of the active site metal clusters, and how metal site cofactors are biosynthesized. In this Review, we detail how the field has advanced over the last ~6 years, with an emphasis on the recent breakthroughs in our understanding of how the active site metal cluster achieves substrate reduction.

Although the physiological substrates are protons and N2, nitrogenases can also reduce a number of other substrates, such as acetylene (C2H2), carbon dioxide (CO2), diazene (HN=NH), and hydrazine (H2N-NH2).20,39,40 We also review the current understanding of the mechanism of reduction of these alternative substrates, which not only is providing new insights into the mechanism of nitrogenase, but also provides insights into possible ways nitrogenase might be used to carry out useful reductions other than N2 fixation.

2. NITROGENASES

2.1. Enzymes

There are three known isozymes of nitrogenase: the molybdenum-dependent Mo-nitrogenase, vanadium-dependent V-nitrogenase, and iron-only Fe-nitrogenase.20,41–49 The nitrogenases are broadly distributed throughout nature with corresponding genes necessary to produce nitrogenases predicted in 13 phyla of bacteria and one phylum of archaea.18,50 Mo-nitrogenase is the predominant isozyme,51 but many diazotrophs carry genes for at least one, if not both, of the other isozymes.44 Because of this distribution, the V-nitrogenase and Fe-nitrogenase are often called “alternative” nitrogenases.41,44,52 Expression of the isozymes appears to be primarily regulated by metal availability, wherein the absence of Mo or the inability to transport Mo efficiently, one of the alternative systems is expressed.43,44,46,49,53

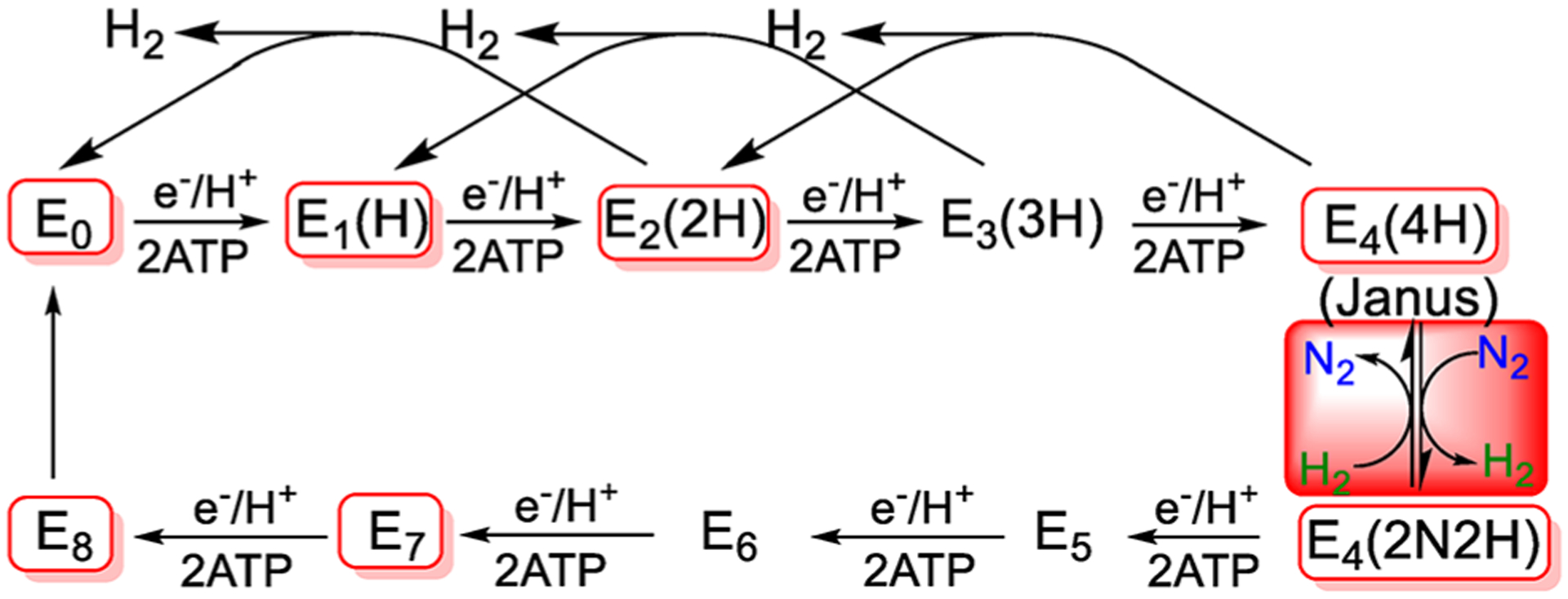

Structures of the Mo- and V-nitrogenase, reviewed elsewhere in this issue, show them to have similar quaternary structures.54–60 The structure of Fe-nitrogenase has not been solved, but available genetic and spectroscopic evidence indicates it is similar to the other two,43,45 as depicted in Figure 1. All three isozymes are two-component protein systems61,62 with the catalytic components for each being encoded by unique gene clusters. Mo-nitrogenase is encoded by nif genes,50,63 V-nitrogenase by vnf genes,64–66 and Fe-nitrogenase by anf genes.66,67 The two component proteins are a catalytic component, or MFe protein (M = Mo, V, Fe) (NifDK, VnfDGK, AnfDGK), which receives electrons from the electron delivery component, or Fe protein (NifH, VnfH, AnfH).20,31,41,43,44 The MFe proteins form as two identical catalytic halves; MoFe protein is an α2β2 heterotetramer and VFe and FeFe proteins are α2β2γ2 heterohexamers.41,43,68 Each catalytic half houses an [8Fe-7S] P-cluster and an active site cofactor called FeMo-co,55–57,69–71 FeV-co,58,72,73 or FeFe-co38 as the site of substrate binding and reduction. Fe protein for all three isozymes is a homodimer, which houses a single [4Fe-4S] cluster and two nucleotide-binding sites for ATP (Figure 1).54,60

Figure 1.

<j/>General nitrogenase architecture. Schematic of nitrogenase structures showing the electron delivery Fe protein component and the catalytic MFe protein component (M = Mo, V, Fe). MoFe protein is an α2β2, and VFe and FeFe proteins are α2β2γ2 heterohexamers. Adapted with permission from ref 38. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

In all three isozymes, electron flow originates from the [4Fe-4S] cluster of the Fe protein, and proceeds through the P-cluster, eventually ending on the active site cofactor FeM-co (Figure 2).74–77 The process of electron flow is complex and is covered in detail in other chapters of this Review.

Figure 2.

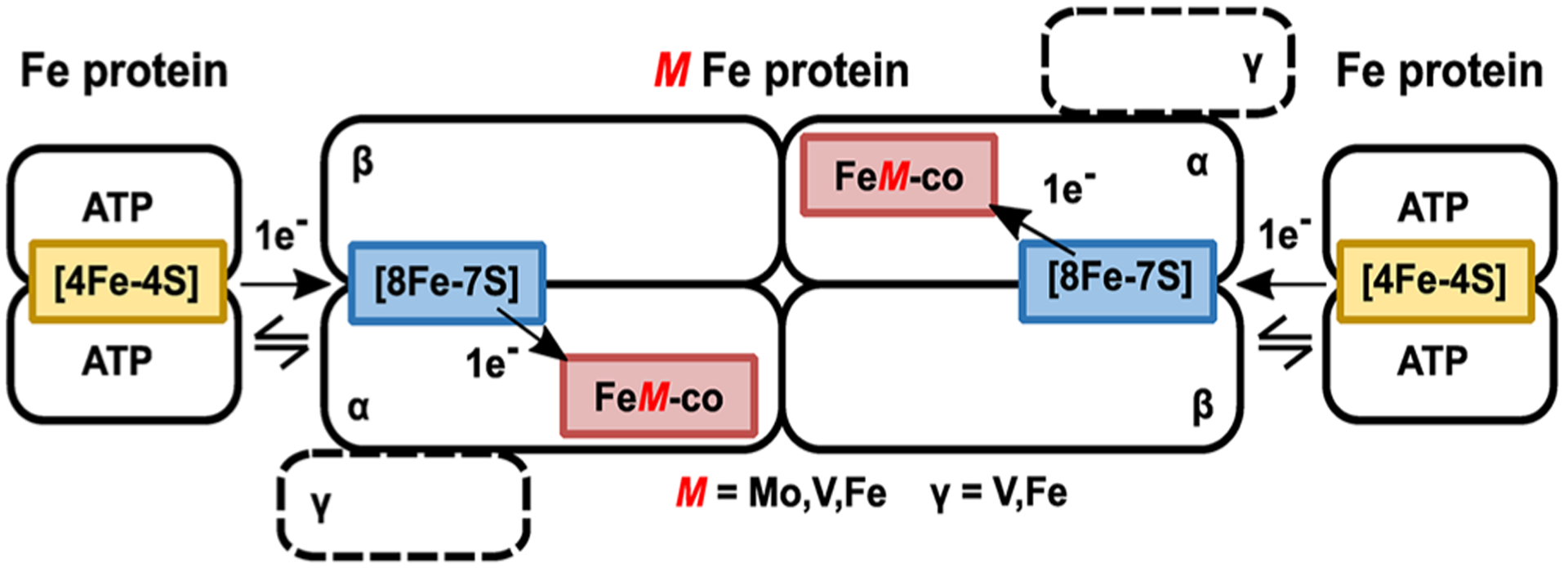

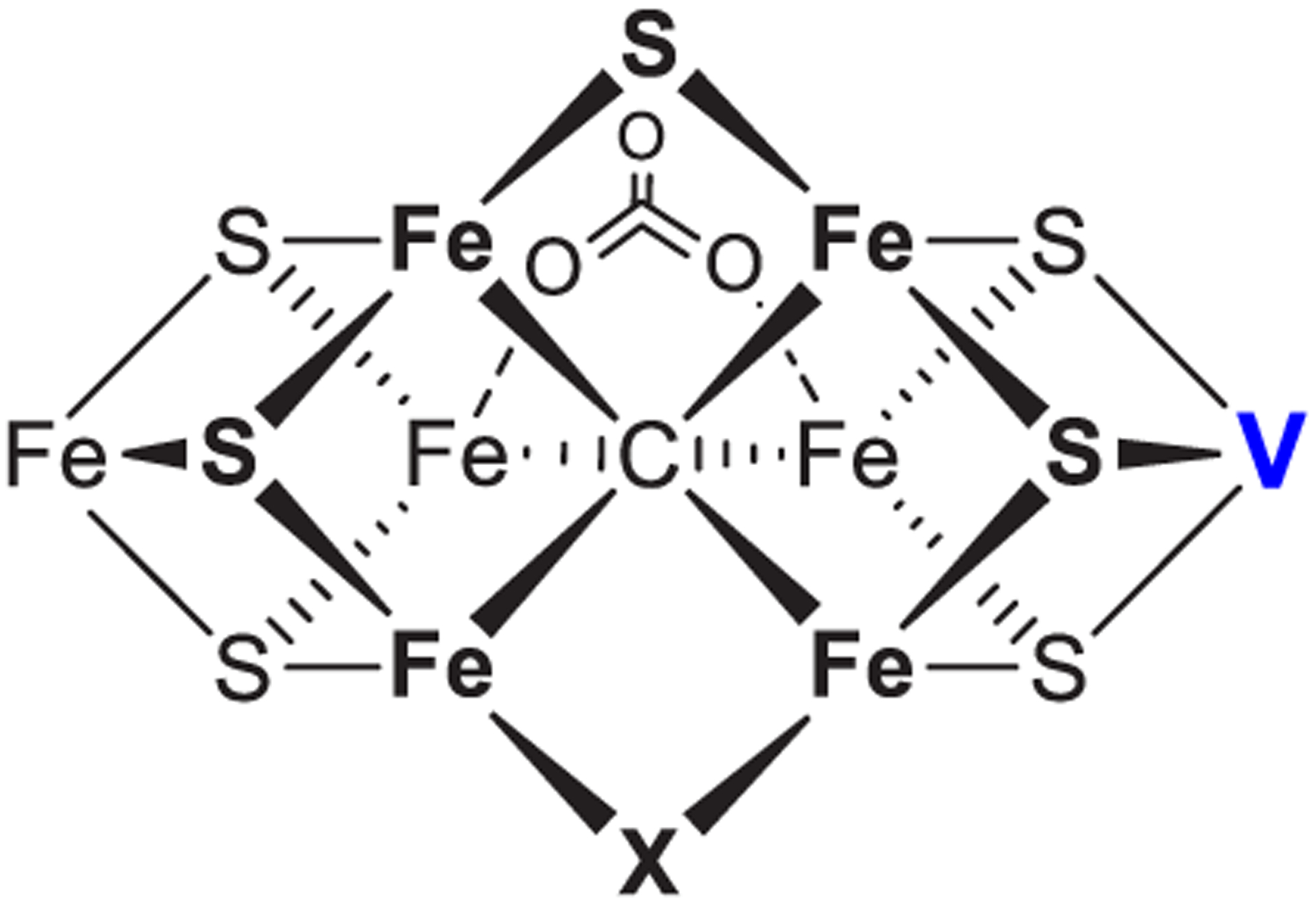

Structures of the FeMo-cofactor of Mo-nitrogenase,56,57,69,79 FeV-cofactor of V-nitrogenase,58,72 and proposed structure of the FeFe-cofactor of Fe-nitrogenase.80 View is looking down on the Fe2, 3, 6, 7 face as indicated by the Fe atom numbering on FeMo-cofactor. Not shown are the cysteine coordinating Fe1, and the histidine and the R-homocitrate tail that ligate the Mo, V, or Fe are shown in blue.

2.2. Cofactors

Electrons and protons are accumulated, and substrates are reduced on the active site cofactor (FeMo-co, FeV-co, and FeFe-co, Figure 2). FeMo-co has the chemical composition [7Fe-9S-Mo-C-(R)-homocitrate] and is often referred to as the M-cluster.56,57,69,70,78,79 FeV-co has a chemical composition of [7Fe-8S-V-C-(R)-homocitrate], with a carbonate ligand bound in place of the ninth sulfur and is sometimes referred to as V-cluster.58,59,72 The FeFe-co is less well studied, but from spectroscopic studies is inferred to have a chemical composition of [8Fe-9S-C-(R)-homocitrate].80

3. MECHANISM OF NITROGENASE REDUCTION OF PROTONS AND N2

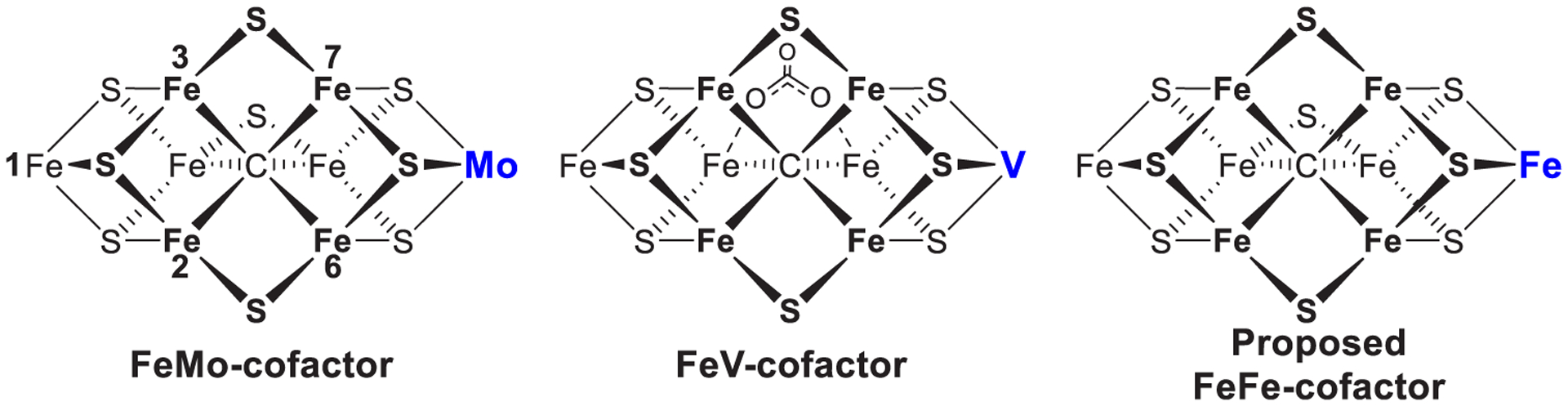

Extensive studies in the 1970s and 1980s20,31,81 led to the development of the Lowe–Thorneley kinetic scheme for catalysis by the Mo-dependent nitrogenase, Figure 3.20,31,81 This describes the transformations among catalytic intermediates, denoted En where n is the number of steps of electron/proton delivery from the nitrogenase Fe protein to the active-site iron–molybdenum cofactor ([7Fe-9S-Mo-C-R-homocitrate]; FeMo-co) Figure 2.23,82 This scheme’s central feature was the mysterious proposal of obligatory formation of one mole of H2 per mole of N2 reduced, with the attendant limiting stoichiometric requirement of 8[e−/H+] per reduction of one N2 to 2NH3, as given by eq 1, in agreement with stoichiometric measurements by Simpson and Burris,19 but in contrast to the six reducing equivalents from 3H2 used in the Haber–Bosch reaction.14

Figure 3.

Simplified 8[e−/H+] kinetic scheme for nitrogen reduction. In the Lowe–Thorneley En notation, n = number of [e−/H+] added to FeMo-co; in parentheses, the stoichiometry of H/N bound to FeMo-co. The re/oa equilibrium is highlighted in red, and the intermediates in red boxes have been freeze trapped for spectroscopic study.

Some early reports presented possible explanations for the proposed connection between H2 evolution and N2 reduction, including models that involve metal-bound hydrides.20,31,83–92 These speculations invoked multiple forms of hydride intermediates,31,88,90 as they sought to explain three important observations of nitrogenase catalysis: (i) obligatory H2 evolution during N2 reduction by Mo-nitrogenase (eq 1),19,93 (ii) H2 (D2) as competitive inhibitors of N2 reduction,88,90,94,95 and (iii) N2-dependent HD formation by Mo-nitrogenase during N2 reduction in the presence of D2.85,88–90,96–100 One report suggested a dihydride intermediate after accumulation of three or four reducing equivalents (E3 or E4 in Figure 3) on the active site, and even suggested that N2 somehow binds by displacing one H2.31,87 Metal-hydride intermediates were also proposed to be involved in the reduction of C-based substrates (e.g., C2H2 and cyclopropene).101–103 In parallel, progress in understanding binding and activation of small molecules, such as N2 and NO3−, by metal-hydride and metal-dihydrogen inorganic compounds suggested possible N2 reduction mechanisms that involved hydrides.83,84,104–108 Such mechanistic speculations included that N2 binds to Mo-nitrogenase by displacing H2 through a Mo-dihydride or trihydride intermediate,83,104 that an H2 complex bound to Mo might play an important role for N2 binding,105 and that nitrogenase evolves H2 through the reductive elimination of a dihydride species bound to either Mo or Fe, favoring the binding and reduction of N2.106 Such multiple contradictory models, although insightful and provocative, were neither experimentally established nor excluded at the time they were suggested.

Despite the connection between N2 reduction and H2 release implied by the kinetic scheme of Figure 3, and the speculations it generated, in fact it had been neither confirmed nor universally accepted20,84 that there is an obligatory, mechanistic requirement for formation of one H2 per N2 reduced to two NH3, with the apparent “waste” of 2[e−/H+] delivered at the cost of 4 ATP hydrolyzed. Beyond that, none of the intermediate states proposed in LT scheme (Figure 3) had been trapped for characterization: the “boxes” connected by the kinetic scheme were empty. Key breakthroughs came after the determination of the structure of the active site FeMo-cofactor55,56 and the application of a combined strategy using genetic, biochemical, and biophysical methods characterize nitrogenase intermediates trapped during turnover with different substrates as previously reviewed21,23,33,36,82,110 and further detailed in the following sections. As a result of these recent studies, seven of the ten states in the kinetic cycle have now been trapped for study (boxed in red in Figure 3).21,23,33,82

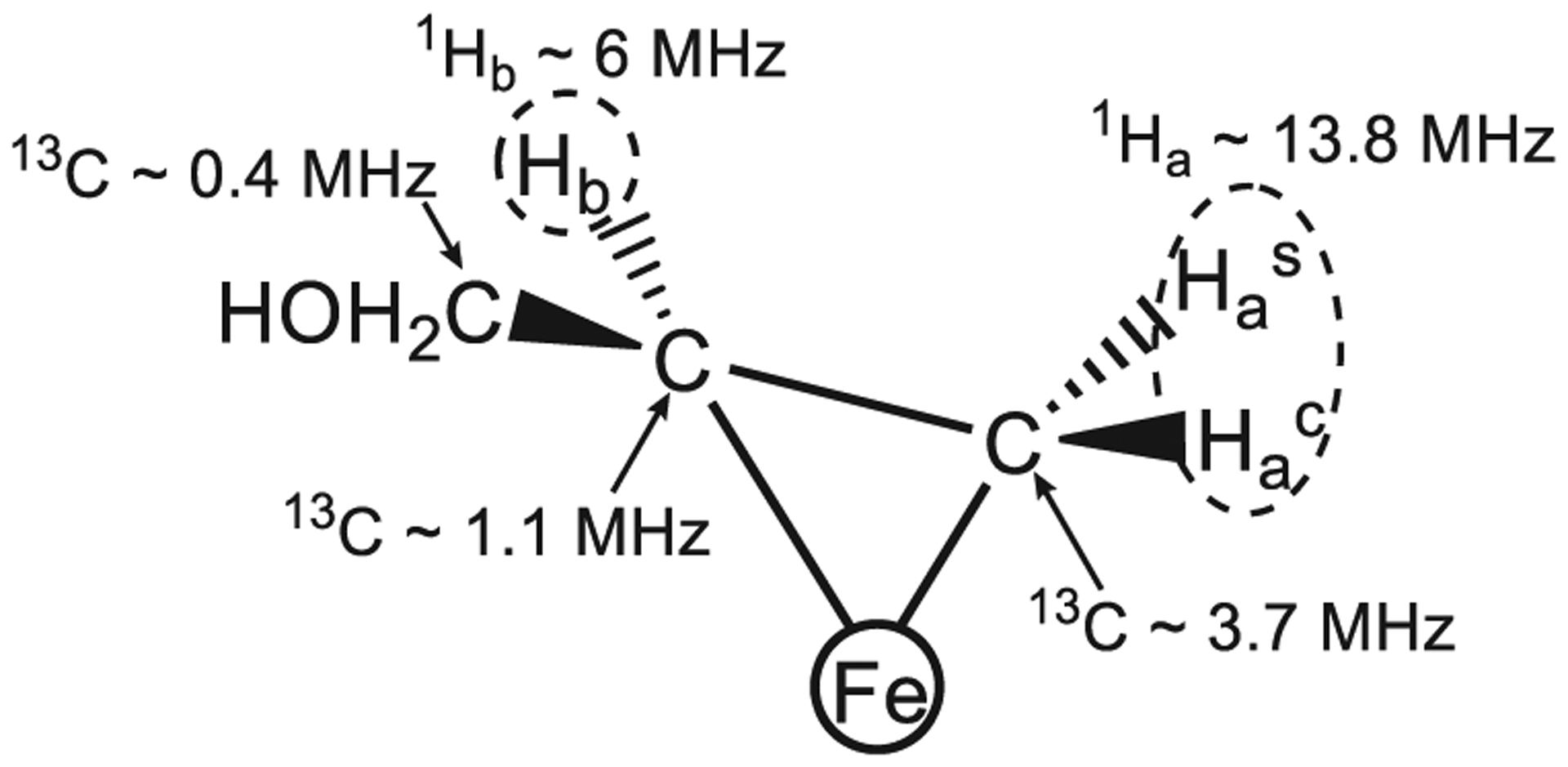

An important step in characterizing catalytic intermediates was the trapping and characterization of an organometallic intermediate allyl alcohol bound as a ferracycle to a single Fe of FeMo-co during turnover with the substrate propargyl alcohol (Figure 4).109 This was followed by characterization of an electron-accumulation intermediate (FeMo-co spin S = 1/2) trapped during turnover of MoFe protein having the α−70Val→Ile substitution,111 which apparently prevents access by all substrates to the active site, other than protons.112 Because electron delivery cannot be experimentally synchronized during turnover, the number of electrons accumulated by this intermediate (n) was not evident. To determine this, the system was frozen to 77 K to prevent further electron delivery by reduced Fe protein, and then, it was warmed while frozen (cryoannealing) until relaxation toward E0 is enabled through a process involving 2-electron steps in which an H2 is released (see Figure 3). This cryoannealing electron-counting protocol showed this state relaxes in two steps with loss of H2 in each step, first to E2(2H) and thence to E0.113 As shown in Figure 3, this identifies the intermediate as the key E4(4H) “Janus” state (defined below),21 which has accumulated four of the eight reducing equivalents required by eq 1. 1,2H/95 Mo ENDOR spectroscopy further showed that these equivalents are stored as two [Fe-H-Fe] bridging hydrides,111,114 not as a previously imagined Mo-H species.83,104 The E4(4H) state of the native/wild-type (WT) enzyme itself115 exhibits identical EPR/ENDOR and photophysical characteristics to this state when trapped in the α−70Val→Ile/α−195His→Gln altered protein.116 As the WT intermediate accumulates in lower abundance, it has proven to be convenient to have these faithfully equivalent versions of the WT state.115,116

Figure 4.

Propargyl alcohol reduction intermediate with hyperfine couplings indicated. Reproduced with permission from ref 109. Copyright 2004 American Chemical Society.

3.1. Reductive Elimination/Oxidative Addition (re/oa) Mechanism: As Proposed

The E4(4H) intermediate represents a critical transition point in the N2 reduction pathway, Figure 3; as both the culmination of the catalytic phase of electron/proton accumulation by the enzyme and the initial step in the N2 reduction phase, it is poised to “fall back” to the E0 resting state by successive release of two H2,113 but equally poised to eliminate H2 and proceed to reduce N2 to two NH3 through the accumulation of four more equivalents, hence the name, Janus, for the Roman god of transitions.21 The trapping of this intermediate for study opened, for the first time, the possibility of directly testing for/characterizing the proposed equilibrium between two E4-level states that interconvert through N2 binding/release coupled to H2 release/binding without additional [e−/H+] input, as visualized in Figure 3.

The experimental determination that E4(4H) stored four reducing equivalents as bridging hydrides111,114 offered explanations of numerous features of nitrogenase mechanism that had defied explanation for decades,20,106 while forging a connection between nitrogenase catalysis and the organometallic chemistry of metal hydrides.106,108,117–119 See the earlier reviews for an account of early speculations about a possible role for hydrides in nitrogen fixation.20,84

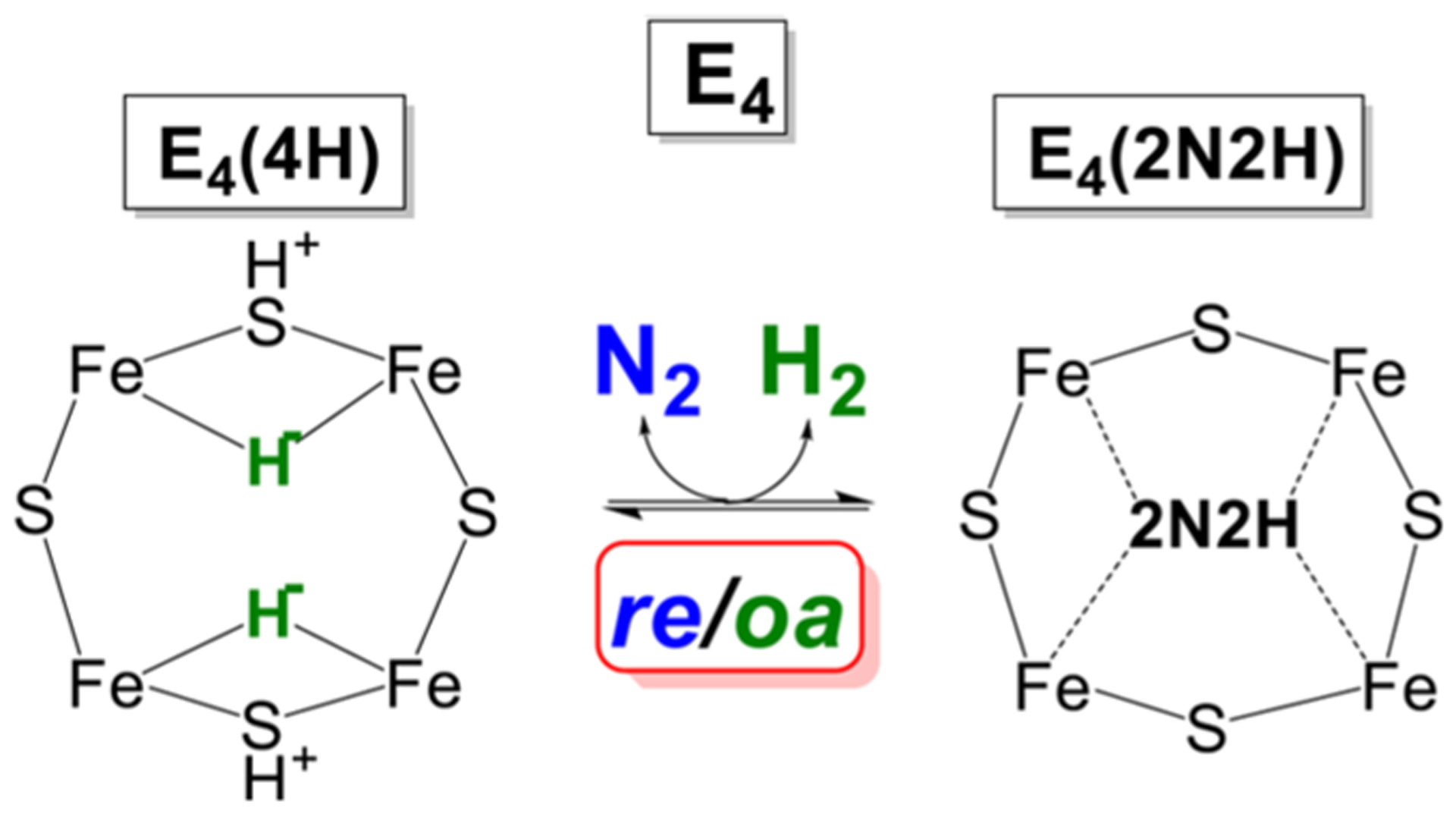

The connection thus established to the chemistry of metal hydrides offered a potential explanation for and justification of the previously mysterious stoichiometry incorporated in eq 1. This explanation was proposed in a pair of “white papers” that showed how the obligatory H2 formation during nitrogenase N2 reduction might explain key experimental observations related to mechanism.21,23 Once it was recognized that E4(4H) contains two bridging hydrides, then the chemistry of metal-dihydride complexes117–119 identifies the proposed [E4(4H) + N2] ↔ [E4(2N2H) + H2] equilibrium (Figure 3) as representing the reductive elimination (re) of H2 and its reverse, the oxidative addition (oa) of H2: a mechanistically coupled re/oa equilibrium Figure 5. The re and release of H2 drives the most difficult (first) step of N2 cleavage: reduction of the N2 triple bond to a diazene level (2N2H) intermediate through delivery to the substrate of the remaining two reducing equivalents.21 As mentioned above and discussed in detail below, this proposal also offered an explanation of the key constraints on a mechanism for nitrogen fixation that had been developed over decades of study.20

Figure 5.

Schematic of re/oa equilibrium. In the indicated equilibrium, the binding and activation of N2 is mechanistically coupled to the re of H2, as described in the text. Adapted with permission from ref 116. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

3.2. Demonstration that Nitrogenase Functions Through the re/oa Equilibrium

The process of defining the mechanistic core of N2 activation, the re/oa equilibrium, as visualized in Figure 5, involved multiple steps over a number of years. It included the demonstration that high-spin (S = 3/2) intermediates previously trapped during turnover under argon of wild type enzyme are E2(2H) isomers,120–123 and was completed by a capstone study of native nitrogenase that trapped and monitored both E4(4H) and E4(2N2H) as a function of turnover conditions.22,115,116,124,125 In so doing, it completed the process of establishing that native nitrogenase is activated by the re/oa equilibrium, which mechanistically requires the loss of one H2 per N2 and results in the attendant 8e− stoichiometry shown in eq 1.19,23

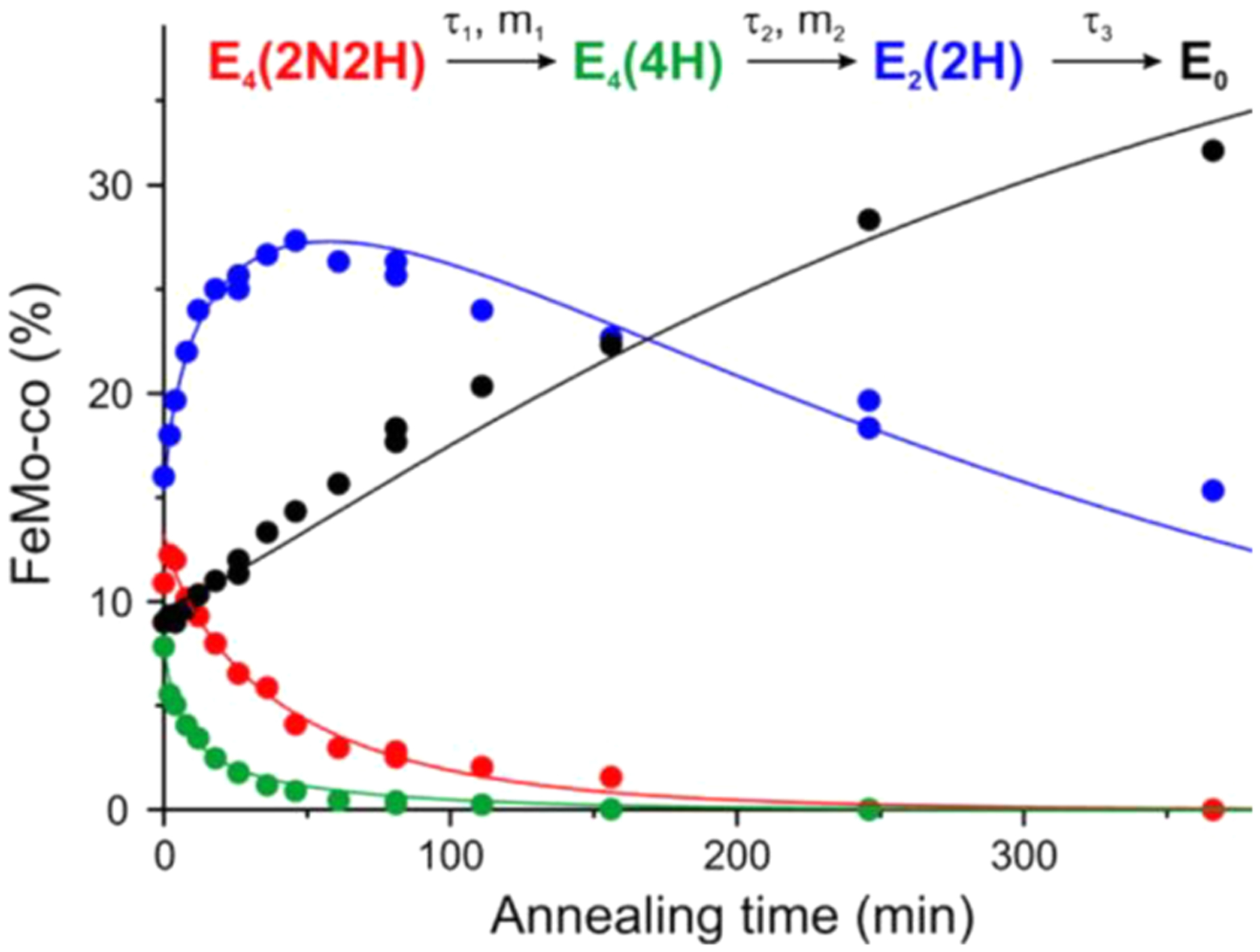

Having identified the EPR spectra of all of the states involved in the relaxation of the E4(4H) and E4(2N2H) (Scheme 1), it was possible to monitor the kinetics of the relaxation of WT E4(2N2H) to the resting-state E0.115,124 The progress curves for the relaxation of E4(2N2H) and kinetically linked intermediates during cryoannealing of WT enzyme at −50 °C presented in Figure 6 are well described by the curves calculated from fits to the sequential kinetic scheme involving the re/oa equilibrium of Scheme 1.115,124 Not only does E4(2N2H) relax to E4(4H), but the amount of trapped E4(2N2H) increases with increasing [N2], while the amount of E4(4H) decreases (Figure 7).115,124

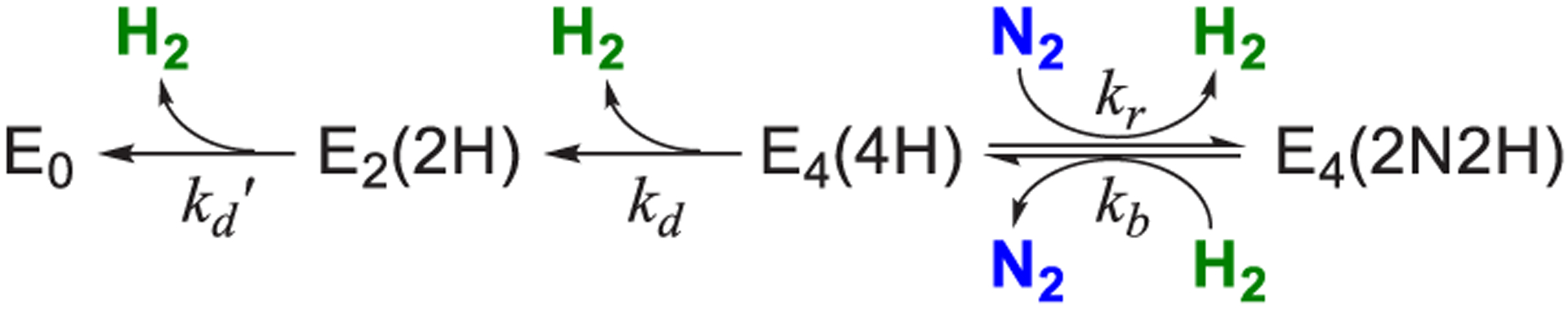

Scheme 1. Kinetic Scheme for the Decay of Freeze-Trapped E4(2N2H) Derived from Figure 3a.

Reproduced with permission from ref 124. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. akr and kb are the second-order rate constants for re and its reverse; kd and kd′ are the rate constants for the irreversible decay of E4(4H) and E2(2H), respectively.

Figure 6.

Time courses of four EPR detected states during −50 °C cryoannealing of WT low P(N2) ~ 0.05 atm turnover in H2O. The data colors correspond to those in the kinetic scheme (top) and the lines correspond to fits to that scheme. Stretched exponential exp(−(t/τ)m) parameters of the first two fast steps are τ1 = 43 min, m1 = 0.79 and τ2 = 6 min, m2 = 0.8, and the third slow step fitted as exponential with τ3 = 330 min. Reproduced with permission from 115. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

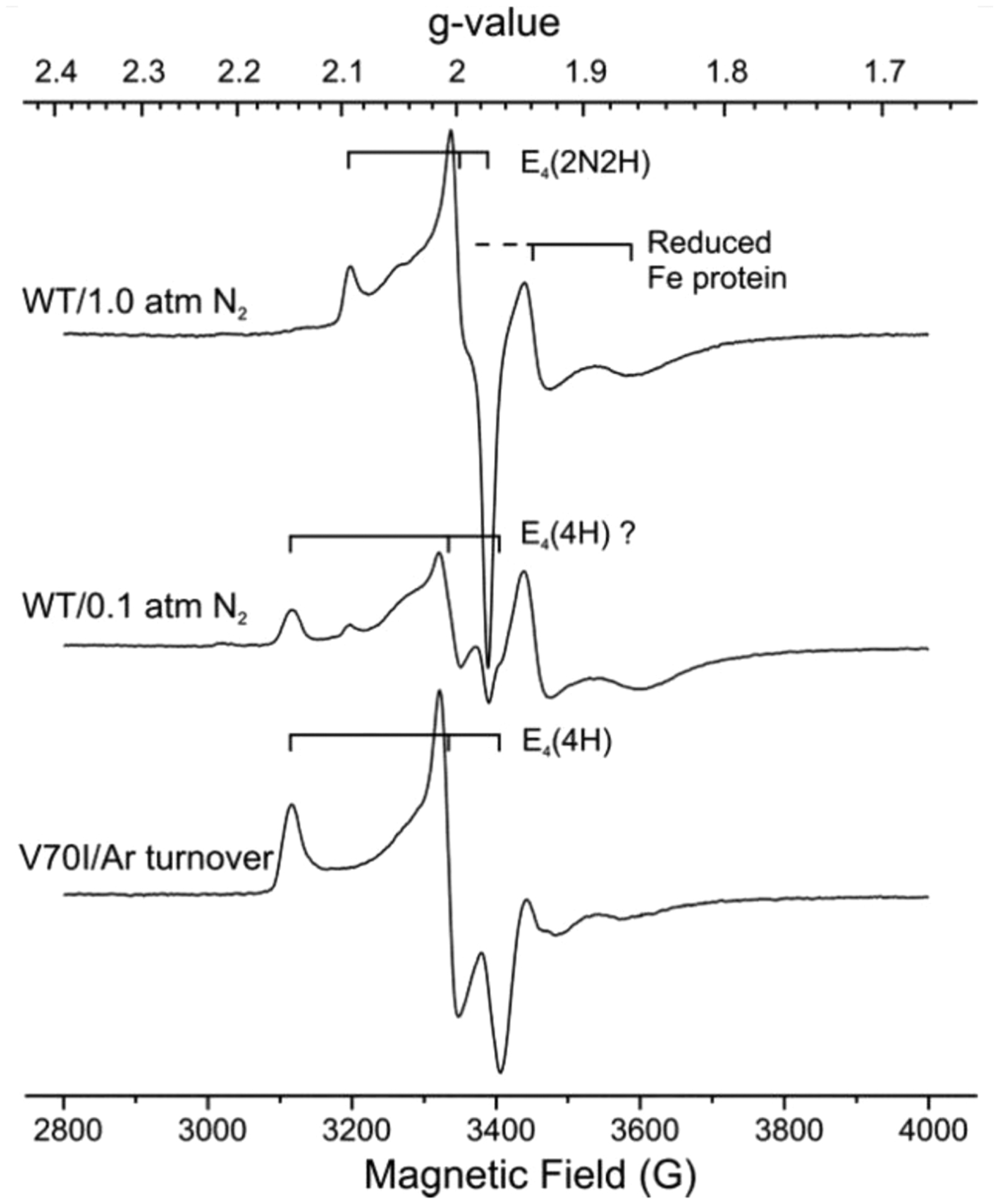

Figure 7.

X-band EPR spectra of WT nitrogenase turnover samples trapped under 1 atm of N2 (with stirring to facilitate transfer of H2 formed during turnover into the headspace124), and under low P(N2) in H2O buffer (without stirring) shown in comparison with spectrum of E4(4H) state trapped during turnover of α−70Val→Ile MoFe protein of the same concentration. Reproduced with permission from ref 115. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

Correspondingly, the rate of relaxation increases with increasing [H2], and decreases with increasing [N2].115,124 This kinetic coupling of the loss of E4(2N2H) to the formation of E4(4H) through oa of H2, directly establishes the operation of the re/oa equilibrium and its kinetic reversibility.

The observation of both E4(4H) and E4(2N2H) in samples freeze-quenched during N2 fixation allowed measurement of the equilibrium constant for re/oa, Kre = kr/kb (Figure 5; Scheme 1).115 This was done by estimating the relative amounts of E4(4H) and E4(2N2H) freeze-trapped under experimentally varied partial pressures of N2 and H2, yielding the re/oa equilibrium constant, Kre and the free energy for the equilibrium, eqs 4 and 5

| (4) |

| (5) |

Thus, this first step in the reduction of N2 by nitrogenase is essentially thermoneutral, ΔreG0 ~ −2 kcal/mol, whereas direct hydrogenation of gas-phase N2 is endergonic by more than 50 kcal/mol.115

3.2.1. re/oa Mechanism Generates the Key Constraints Revealed by Experiment.

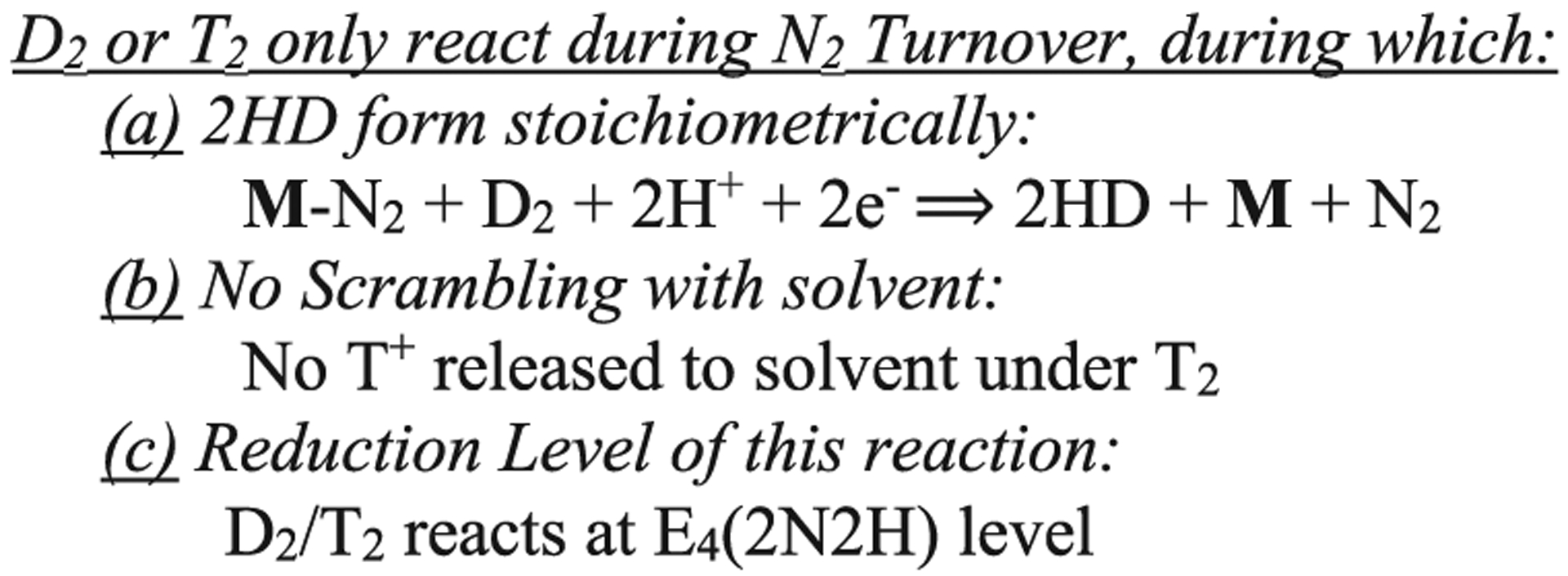

Decades of study had revealed several puzzling features of nitrogen fixation by nitrogenase whose mechanistic origins were not understood, but ultimately served as key constraints on any proposed mechanism, Chart 1.20,21,23 A series of experiments has shown that all of these constraints are generated by the functioning of the re/oa mechanism.

Chart 1.

Key Constraints on the Nitrogenase Mechanism20

These constraints arise from previously confusing results from turnover in the presence of D2 or T2. It was found that D2 and T2 only react with nitrogenase during turnover under an N2/D2 or N2/T2 atmosphere90,98 at the E4(2N2H) reduction level (c); in this reaction D2 is stoichiometrically reduced to two HD (with H2O buffer) (a);88,89,98 corresponding turnover with T2 does not lead to exchange of T+ into H2O solvent (b).90 It has now been shown that all these D2/T2 constraints arise through the reverse of the re process, Figure 5, namely, the oxidative addition (oa) of H2 with loss of N2.21,23 According to the mechanism, during turnover under D2/N2, reaction of the E4(2N2H) intermediate with D2 generates dideutero-E4 with two [Fe-D-Fe] bridging deuterides that do not exchange with solvent,22 and the same is true for T2. These E4(4H) isotopologues, which are denoted E4 (2L−;2H+), L = D or T, would relax through E2(L−;H+) to E0 with successive loss of two HL.21,113

The proposed formation of the E4(2D−;2H+) and E2(D−;H+) states through the thermodynamically allowed reverse of re, the oa of D2 with accompanying release of N2, in fact was the first successful test of the re/oa mechanism. When these states were formed during turnover under N2/D2, the nonphysiological substrate acetylene (C2H2) intercepted them to generate deuterated ethylenes (C2H3D and C2H2D2).22 More recently the E4(2D−;2H+) and E4(2H−;2D+) states were observed and characterized by EPR spectroscopy and by studies of isotope effects on the photophysical properties of these isotopologues.115

3.2.2. There Are No Reductive Activation Steps Prior to Catalysis.

In recent years, mechanistic proposals have posited that multiple [e−/H+] must be delivered to the true resting-state FeMo-co to activate it to a state that acts as the E0 in an 8[e−/H+] catalytic cycle equivalent to the scheme of Figure 3.126 First, of course, no such preactivation process was observed in the many presteady state measurements carried out on as-isolated nitrogenase over decades.20,31 But most importantly the measurements of the relaxation of the odd-electron S = 1/2 E4(4H) with release of 2H2 (Figure 6)113 unambiguously show that it relaxes directly to the same EPR-active odd-electron E0 (S = 3/2) resting state that has been isolated and characterized crystallographically, not to a different state, which at least in one model, would not even be odd-electron.126 And there is no doubt that E4(4H) indeed relaxes to the crystallographically characterized E0 state. The identity of the crystalline E0 and the putative E0 formed by E4(4H) relaxation is established by the identity of the EPR spectra of the solution E0 formed by relaxation and that of the crystalline E0,57,127 both of which precisely match the long-established EPR spectrum of as-isolated Mo-nitrogenase in solution.

3.3. Exploring the re/oa Mechanism

Upon establishing that nitrogen fixation by nitrogenase operates through the re/oa mechanism with its 8[e−/H+] stoichiometry, further experiments and computation have been used to explore the microscopic details.

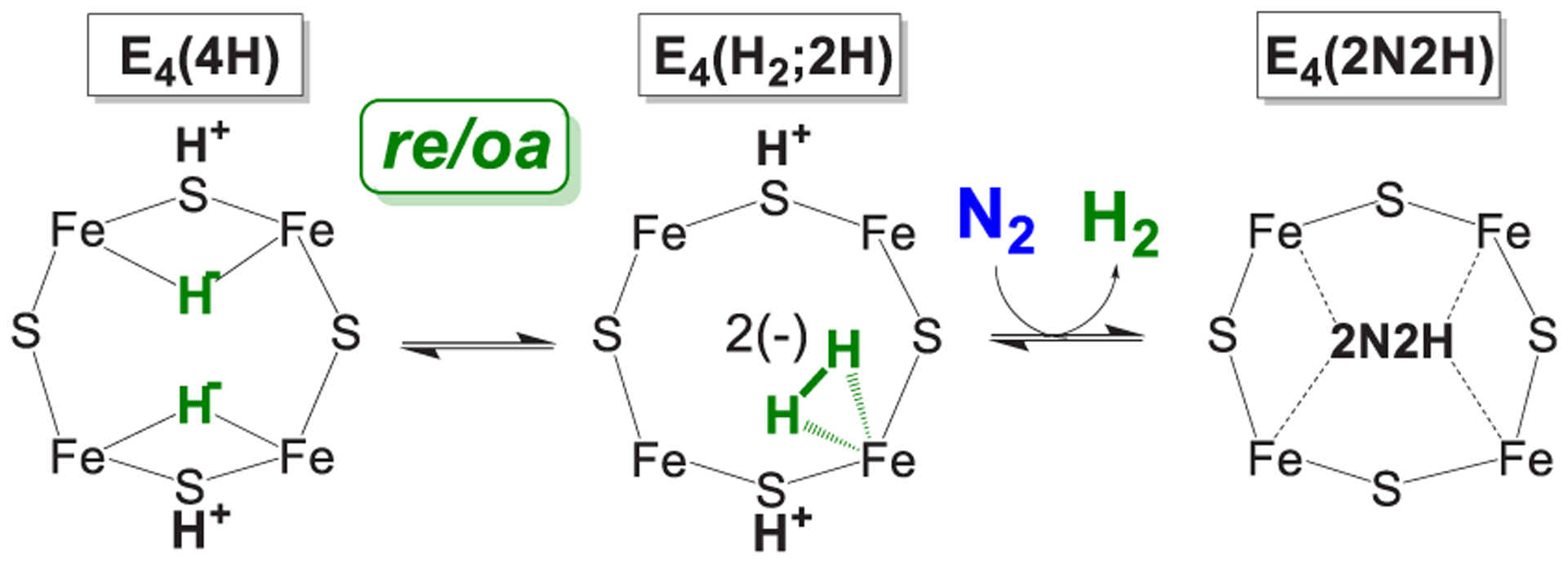

3.3.1. Reductive Elimination Involves an H2-Bound Intermediate.

The demonstration that the E4(4H) Janus intermediate has accumulated four reducing equivalents as two [Fe-H-Fe] bridging hydrides, and the resulting link thus forged between nitrogenase catalysis and the organometallic chemistry of metal hydrides, inspired examination of the behavior of E4(4H) under photolysis as a test of this linkage and as a means of obtaining atomic-level details of the re activation process. The photolysis of transition metal dihydride complexes typically results in the release of H2,108,128–135 and it was found that H2 release in fact occurred during in situ 450 nm photolysis of E4(4H) in an EPR cavity at temperatures below 20 K.116,125 These studies, as supported by density functional theory (DFT) calculations,136 showed that an H2 complex on the ground adiabatic potential energy surface E4(H2;2H) becomes populated during catalysis, but this state cannot lose H2 because the resultant, denoted [E4(2H)* + H2], is at inaccessibly high energy.125 However, N2 can bind and displace the H2 of E4(H2;2H) to complete the conversion of [E4(4H) + N2] into [E4(2N2H) + H2], as represented in Figure 8.136

Figure 8.

Cartoon version of suggested catalytic pathway for re/oa activation of FeMo-co for N2 reduction. Reproduced with permission from ref 125. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

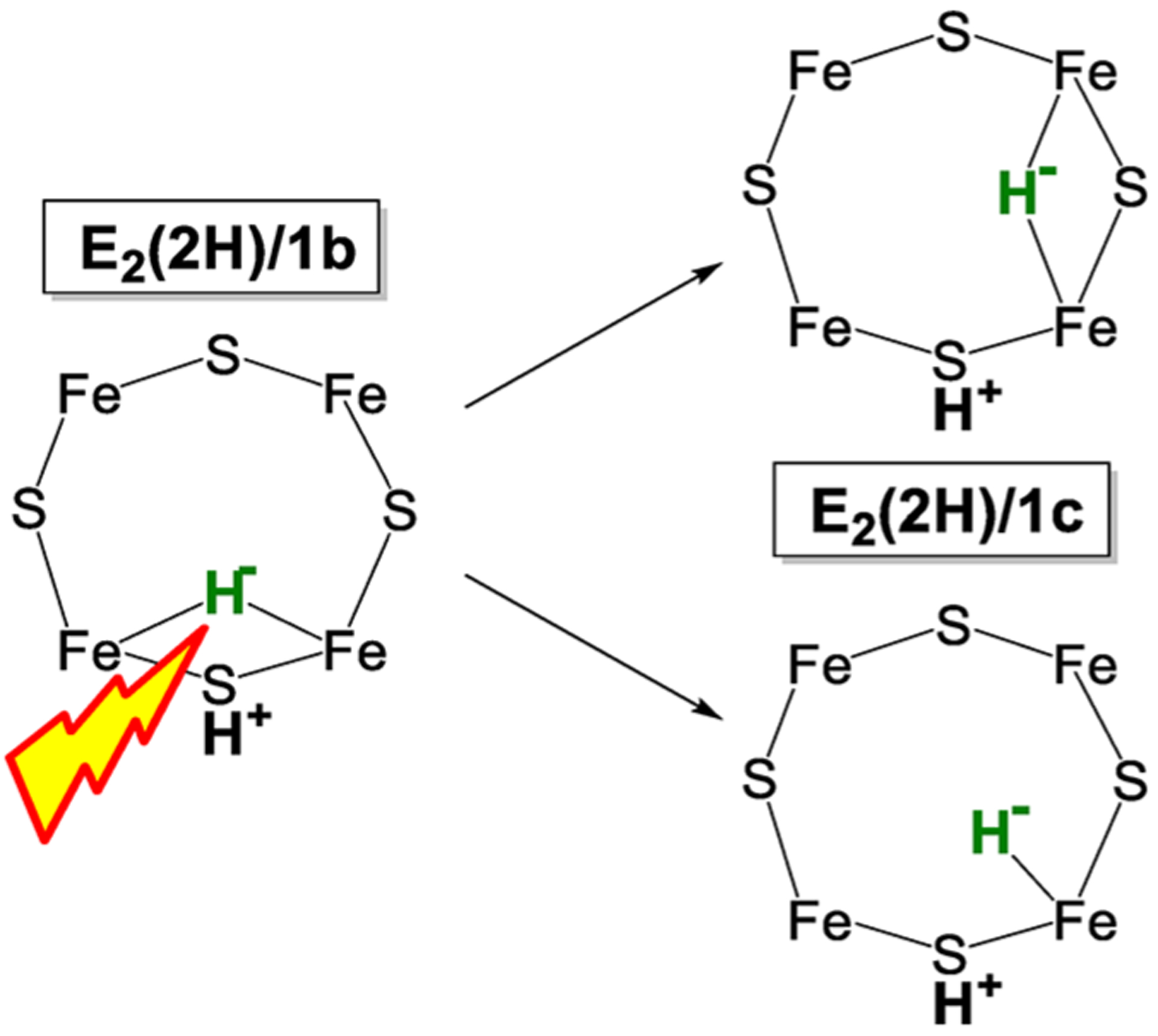

3.3.2. E2(2H) States 1b and 1c Are Hydride Isomers.

As a further use of hydride photolysis to explore nitrogenase function, it was shown that E2(2H)/1b stores the two reducing equivalents as a hydride, almost surely with the [Fe-H-Fe] bridging mode of binding, and that 1c is a hydride isomer of E2(2H)/1b, either with the hydride bridging a different pair of Fe or having converted to a terminal hydride, as visualized in Figure 9.123 Relatively modest differences in the occupancy ratio of the two E2(2H) hydride conformers during turnover, 1b/1c ~ (2–3)/1, suggested that the two are able to readily interconvert during fluid-solution turnover.123

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of photolysis conversion of [Fe-H-Fe] hydride bridge of E2(2H)/1b into isomer E2(2H)/1c with either a hydride bridge between a different pair of Fe ions or an Fe-H terminal hydride. Adapted with permission from ref 123. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society

3.3.3. Density Functional Studies of the re/oa Equilibrium.

The structure and energetics of possible nitrogenase intermediates were recently explored by DFT calculations on a broad range of structural models for the active site and a variety of DFT exchange and correlation functionals.136–139 These computations136 showed that it is necessary to include all residues (and water molecules) interacting directly with FeMo-co via specific H-bonds interactions, nonspecific local electrostatic interactions, and steric confinement to prevent spurious disruption of FeMo-co126,140–142 upon accumulation of 4[e−/H+]. These calculations indicated an important role of sulfide hemilability in the overall conversion of E0 to a diazene-level intermediate, as suggested by X-ray crystallographic studies.58,59,143,144 Perhaps most importantly, they explained how the enzyme mechanistically couples exothermic H2 formation to endothermic cleavage of the N≡N triple bond in the nearly thermoneutral re/oa equilibrium discovered experimentally (Figure 10), while preventing the futile generation of two H2 without N2 reduction: hydride re generates an H2 complex, again in agreement with experiment, and H2 is only lost when displaced by N2, to form an end-on N2 complex, which then proceeds to a diazene-level intermediate.136

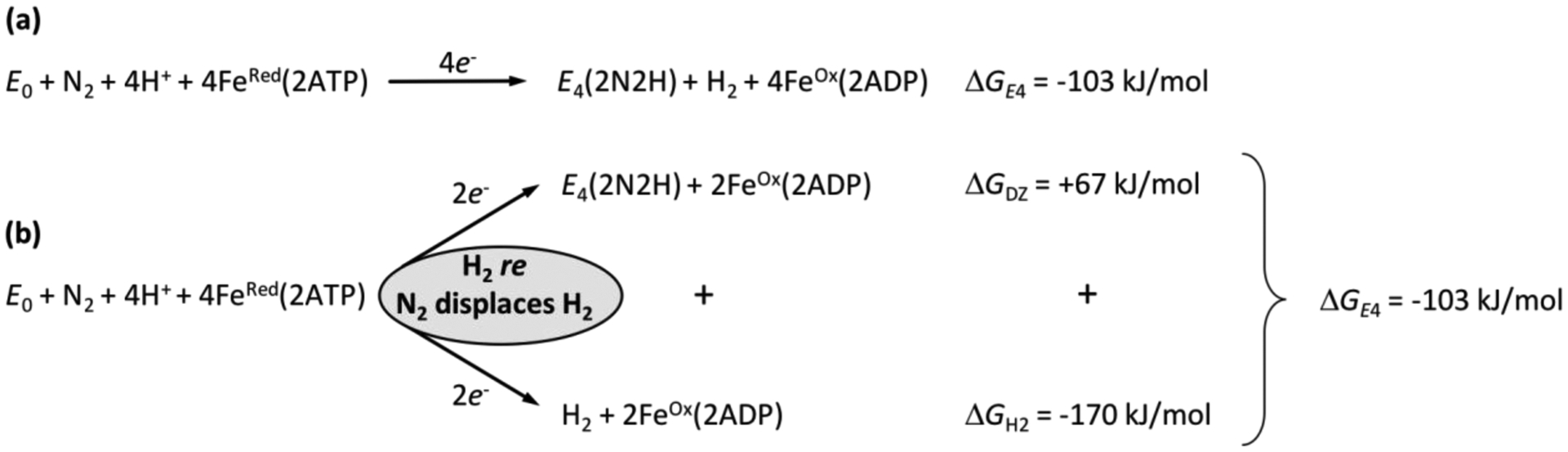

Figure 10.

Energetics of formation of E4(2N2H) from the enzymatic reactants and its decomposition into two individual two-electron, two-proton processes, each involving the hydrolysis of 2ATP per electron: the formation of E4(2N2H) and of H2, which are coupled through displaces and releases H2 formed by re from E4(4H). Adapted with permission from 136. Copyright 2018 National Academy of Sciences.

3.3.4. High-Resolution ENDOR Spectroscopy Coupled with Quantum Chemical Calculations Reveals the Structure of Janus Intermediate E4(4H).

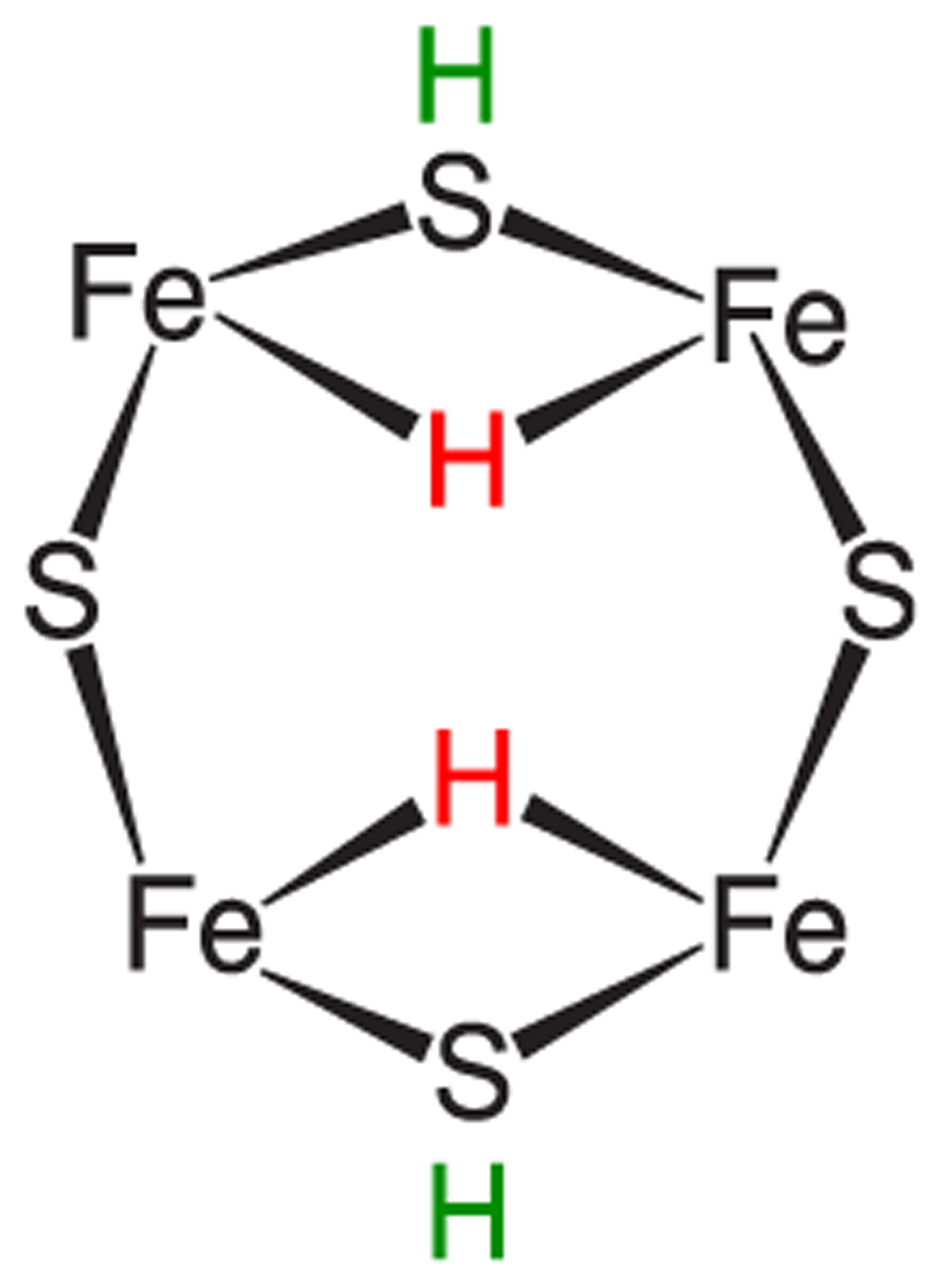

Because of the central role of E4(4H) in the re/oa mechanism, it was essential to characterize its structure. The original 1H ENDOR study of E4(4H),111 and subsequent 95Mo and 57Fe ENDOR study114,145 demonstrated that FeMo-co in E4(4H) contains two [Fe-H-Fe] bridging hydrides but were unable to provide a satisfactory picture of the relative spatial relationships of the two hydrides. The nature of E4(4H) has been the subject of numerous recent computational studies based on DFT.136–139 The lowest-free-energy E4 isomers obtained from the DFT studies reported so far have two of the four hydrogens located on μ2-S atoms, while the other two hydrogens are either present as hydrides in bridging positions between two Fe atoms, or in mixed bridging/terminal position on the Fe2,3,6,7 face of FeMo-co,136,137,146,147 or as a dihydrogen (η2-H2) adduct bound to either Fe2136,137,147 or Fe6.147

As we pointed out, limitations in DFT-based schemes—the only ones computationally feasible for a systematic study of complex systems, such as FeMo-co—make it difficult to determine the ground-state structure of E4(4H) based on DFT-derived relative energies alone. To emphasize this issue, careful computational analyses carried out by the research groups of Ryde137,146,148,149 and Bjornsson139,147 have clearly shown that the exchange and correlation functional adopted in the DFT calculations largely affect the ordering of possible E4 isomers, which differ on the location of the hydrides. This uncertainty is further aggravated by intrinsic deficiency of broken symmetry DFT calculations which are simply unable to capture the multideterminant character of the electronic structure of FeMo-co. A detailed discussion of all of these issues has been presented by Cao and Ryde.146

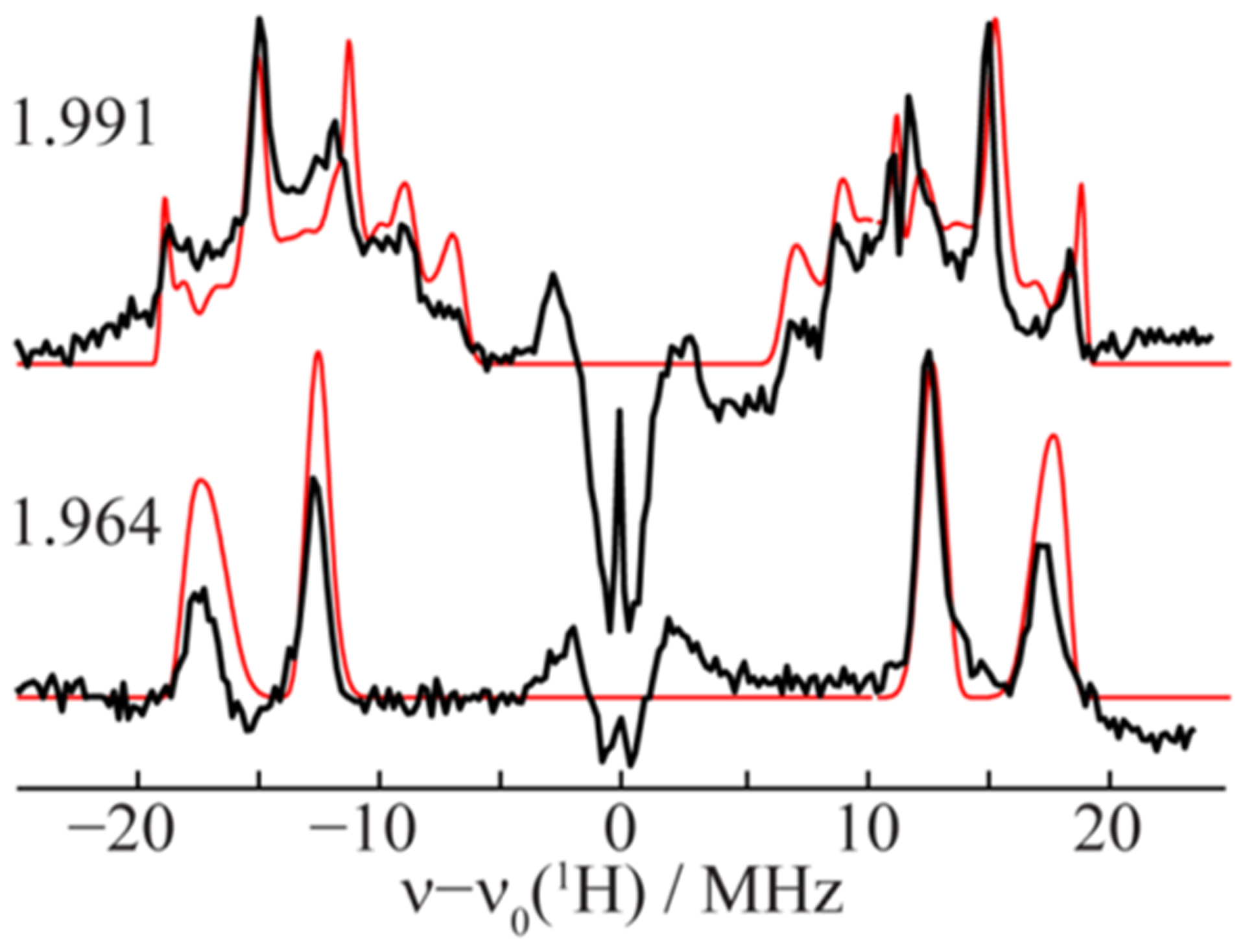

To determine how the Janus intermediate binds its two hydrides, exhaustive, high-resolution CW-stochastic 1H-ENDOR experiments were performed using improved ENDOR methodologies and updated equipment.150 Figure 11 illustrates the remarkable spectroscopic resolution and strong orientation selection that enabled the previously unattainable determination of absolute hyperfine-interaction signs. The important results for structural assessments were the findings that (i) the dipolar–electron–nuclear hyperfine coupling tensors for the two hydrides were coaxial, (ii) each had “rhombic symmetry” (two components with equal and opposite signs; one null component), and (iii) the signed tensor components for the two hydrides were permuted relative to each other.

Figure 11.

35 GHz 1H stochastic-field modulation detected (stochastic CW) ENDOR spectra of E4(4H) in 70Val→Ile/α−195His→Gln MoFe protein, acquired at g = 1.991 and 1.964 (black) and summed simulations (red). The signal with ν0(1H) ± ~3 MHz, with both positive and negative features, represents transient responses from weakly coupled, more distant protons. Reproduced with permission ref 150. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

These findings provided critical constraints on the structure of E4(4H), but did not by themselves implicate a particular structure, and so experiment was coupled to the DFT computations. Just as the DFT computations could not discriminate among candidates for the E4(4H) ground state, neither could they discriminate through computations of the dipolar hyperfine couplings. However, the DFT structures are robust and so the ENDOR measurements were coupled to DFT structural models through an analytical point-dipole Hamiltonian for the hydride electron–nuclear dipolar coupling to its “anchoring” Fe ions, an approach that overcomes limitations inherent in both experimental interpretation and computational accuracy. The simple point-dipole approximation was not expected to provide quantitatively accurate results for the magnitudes of the hyperfine tensor components because of the delocalized nature of the electron density in the FeMo-co.147 Instead, for each of the DFT-derived candidate structures for E4(4H) ground state the dipole approach was simply used to assess the relative orientation of the dipolar interaction tensors for the two hydrides of a structural model when each had a rhombic tensor, and this was compared to the experimentally determined relative tensor orientation.146,147,150

This comparison alone enabled discrimination among possible E4(4H) isomers.23,111 The result: the freeze-trapped, lowest-energy Janus intermediate structure is E4(4H)(a), Figure 12. As the calculations indicated the presence of a number of isomers close in energy,137,139,146,147,150 it was envisioned that at ambient temperatures the E4(4H) hydrides become fluxional, with a dynamic population of multiple isomers.

Figure 12.

Cartoon of the 2,3,6,7 face of the ground state isomer of E4(4H), denoted E4(4H)(a) as found by BS-DFT computation. Reproduced with permission from ref 150. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

As additional DFT computations are carried out, suggesting variations on the E4(4H) structure, the results of this ENDOR study, in conjunction with the analytical point-dipole Hamiltonian, will continue to provide the benchmark against which those structures can be tested.

3.3.5. E1 Forms by Reduction of Fe, Not Mo.

The E1(H) state as prepared both by low-flux turnover and by radiolytic cryoreduction were investigated using a combination of Mo Kα-HERFD (high energy resolution fluorescence detection) and Fe K-edge PFY (partial-fluorescence yield) X-ray absorption spectroscopy techniques.151 The results demonstrate that this state is formed by an Fe-centered reduction and that Mo does not change redox state, a further indication that Mo is only indirectly involved in substrate reduction, which occurs at Fe. This conclusion is further supported by a recent Mo and Fe K-edge EXAFS (extended X-ray absorption fine structure) characterization of E0 and E1 states in combination with QM/MM calculations that supported protonation of a belt sulfide (S2B or S5A) in E1.152

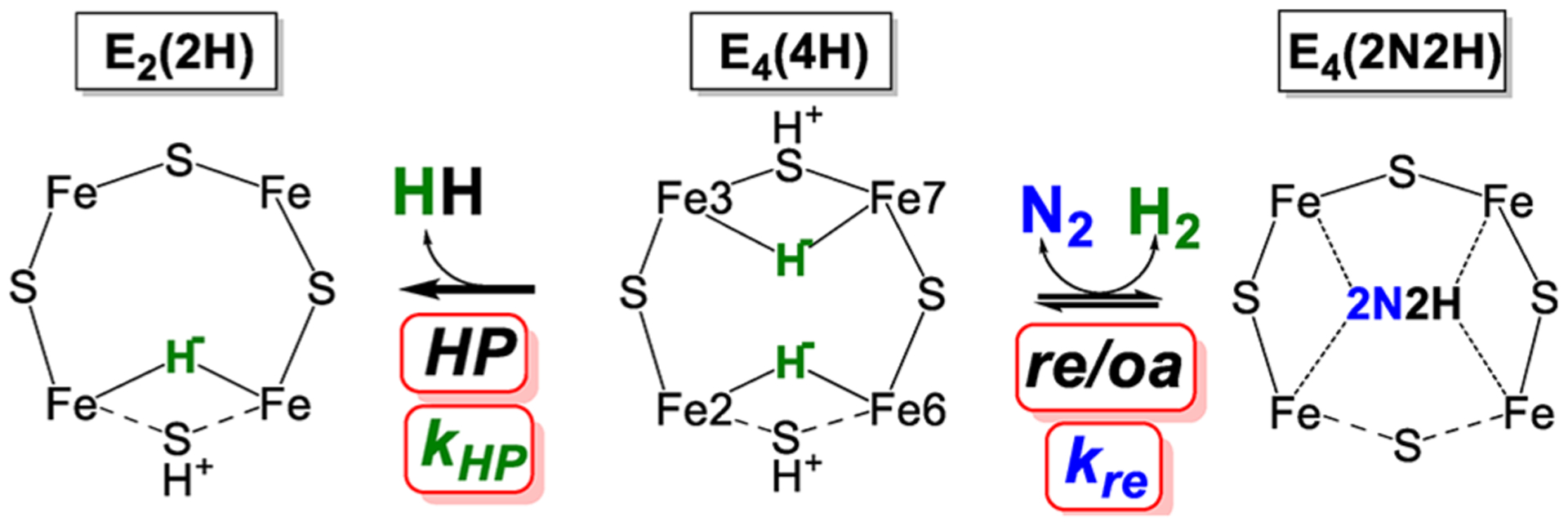

3.4. Kinetic Description of the Competing Reactions at E4(4H)

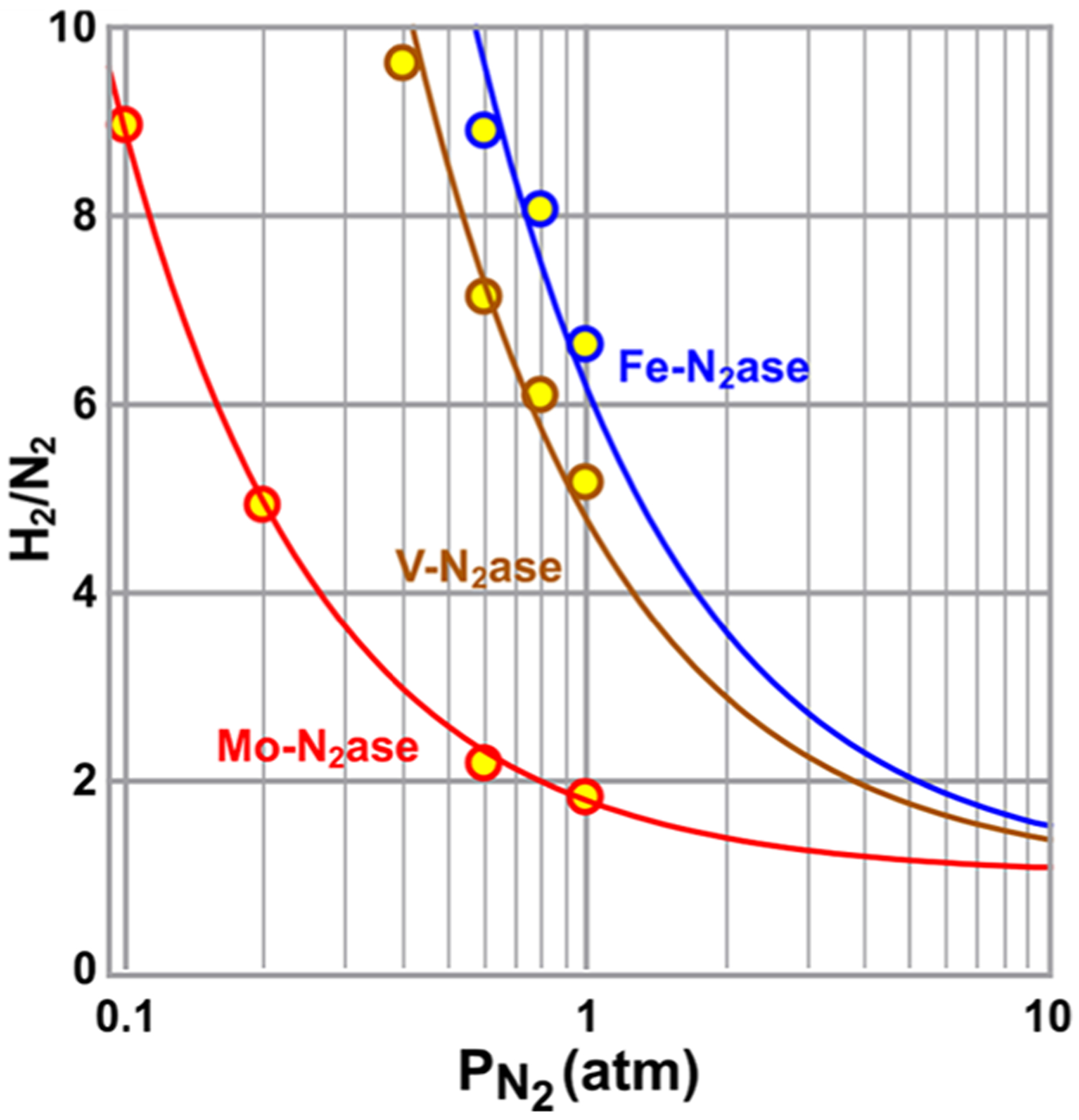

As can be seen in Figure 13, the reactions of E4(4H) can be viewed as a competition: the forward direction of the re/oa equilibrium, involving binding of N2 and displacement of H2, competes with the relaxation of E4(4H) through hydride protonolysis (HP), which releases H2 without N2 binding.153,154 The competition between these two reactions is defined by the ratio of their rate constants kre for the forward reaction and kHP for the relaxation reaction and modulated by the ratio of the partial pressures of N2 and H2. A kinetic model was developed that yields, under high electron flux conditions (high Fe protein to MoFe protein molar ratio), the values of these two rate constants from the fitting of the ratio, H2 formed divided by N2 reduced, as a function of the partial pressure of N2. As can be seen in Figure 14154 and from measurements by many groups, at 1 atm of N2, Mo-nitrogenase shows H2/N2 < 2 and the ratio asymptotically approaches unity with increasing N2 partial pressure. The fit to the data of Figure 14 yielded kre/kHP = 5.1 atm−1. This considerable preference for the forward reaction is truly remarkable when considering the expected reactivity of a metal hydride toward protonolysis as observed in many reductive catalysts. Corresponding suppression of the formation of H2 by an HP reaction in synthetic catalysts for N2 reduction is one of the grand challenges in catalyst design.

Figure 13.

Reactions of the E4 state. N2 binds through re with rate constant kre to the right. H2 evolves through HP with rate constant kHP to the left. Reproduced with permission 153. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

Figure 14.

Ratio of H2 evolved to N2 reduced as a function of partial pressure N2 for all three nitrogenase isozymes. The fits to this data for each enzyme produce the value of its parameter ρ = kre/kHP Reproduced with permission from ref 154. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

The two other isozyme of Mo-nitrogenase, the V- and Fe-nitrogenases, share similar architecture to the Mo-enzyme, but as noted above, have different polypeptides that present different active site environments and different active site metal clusters.43,58 At 1 atm of N2, it can be seen that the V- and Fe-nitrogenase show much higher ratios of H2 formed per N2 reduced (Figure 14). Application of the high-flux kinetic model to the V- and Fe-nitrogenases, revealed reduced values of the rate-constant ratio compared to Mo-nitrogenase, kre/kHP= 1.1 and 0.78 atm−1, respectively.154 Further analysis pinpointed that whereas the values for kre for the V- and Fe- nitrogenases are as much as 10-fold smaller than kre for the Mo enzyme, the values of kHP differ by less than 2-fold. In short, the V- and Fe-nitrogenases are not better at the HP side-reaction, but rather are poorer at the productive re reaction. The source of these differences among the three nitrogenase isozyme remains to be deduced.153,154

3.4.1. All Three Nitrogenases Employ the re/oa Mechanism.

The differences in rate constants among the three isozymes might suggest a different mechanism for N2 binding and activation. However, this is not so. The re/oa mechanism involves an equilibrium between the E4(4H) state and the E4(2N2H) state. This predicts H2 inhibition of N2 reduction and the formation of HD during turnover under mixed D2 and N2, both of which were found for all three isozymes. These observations establish that all three nitrogenase isoforms follow the same re/oa mechanism.38,153,154

3.5. Structure–Function Relationship During Nitrogenase Catalysis

One of the persistent challenges in nitrogenase research is to understand how protein and cluster dynamics might participate in the mechanism.32,33,35–37,68,75,156–168 Many structural and spectroscopic studies have shown that the resting state of nitrogenase is largely unreactive, suggesting that motion of the surrounding protein or changes in ligation of FeMo-co might be essential in catalysis.32,33,82,158 A number of calculations have suggested changes in FeMo-co that could be occurring during catalysis, including breaking of one or more the Fe–C bonds126,140,141,169–171 or breaking one or more Fe–S bonds.136,172–177 Recent structural studies have observed significant changes in the FeMo-co and FeV-co structures that might point to dynamics relevant to catalysis.58,59,143,144,178 In one such study, it was observed that MoFe protein under turnover with CO shows the substitution of one of the belt sulfide ligand S2B by a bridging CO ligand143 (see section 5.2 for more details). These studies point to lability in one or more of the Fe–S bonds during turnover.178,179 This lability was seen in the computational study of the re/oa equilibrium described in sections 3.3.3 and 3.3.4.136 Recently, a structure of the V-nitrogenase by Einsle et al. showed FeV-cofactor with two belt sulfide ligands substituted by a proposed carbonate and a light atom (N(H) or O(H), Figure 15).59,155 Even though the identity of the light atom ligand is under debate, the plausible implication and relevance to the N2 reduction mechanism by nitrogenase have initiated vigorous discussion.156,180,181 The recent progress in spectroscopic studies on nitrogenase intermediates162 and the X-ray structures of nitrogenase from turnover mixtures promises further progress in understanding the dynamics of the metalloclusters, especially the active site FeM-cofactor during substrate/inhibitor interaction.

Figure 15.

FeV-cofactor structure proposed by X-ray structure (X = NH)59 and theoretical calculations (X = OH).155

4. NONPHYSIOLOGICAL N-BASED SUBSTRATES

4.1. Range of N-Based Substrates

An important property of nitrogenases is the ability to bind and reduce a number of nonphysiological substrates.20,39,40 A common, but not universal, property of nitrogenase substrates is that they are small and contain double or triple bonds. The study of how these alternative substrates interact with nitrogenase has provided important mechanistic insights.20,23,33,41,82 In this section, recent work on a number of alternative substrates that contain N is reviewed.

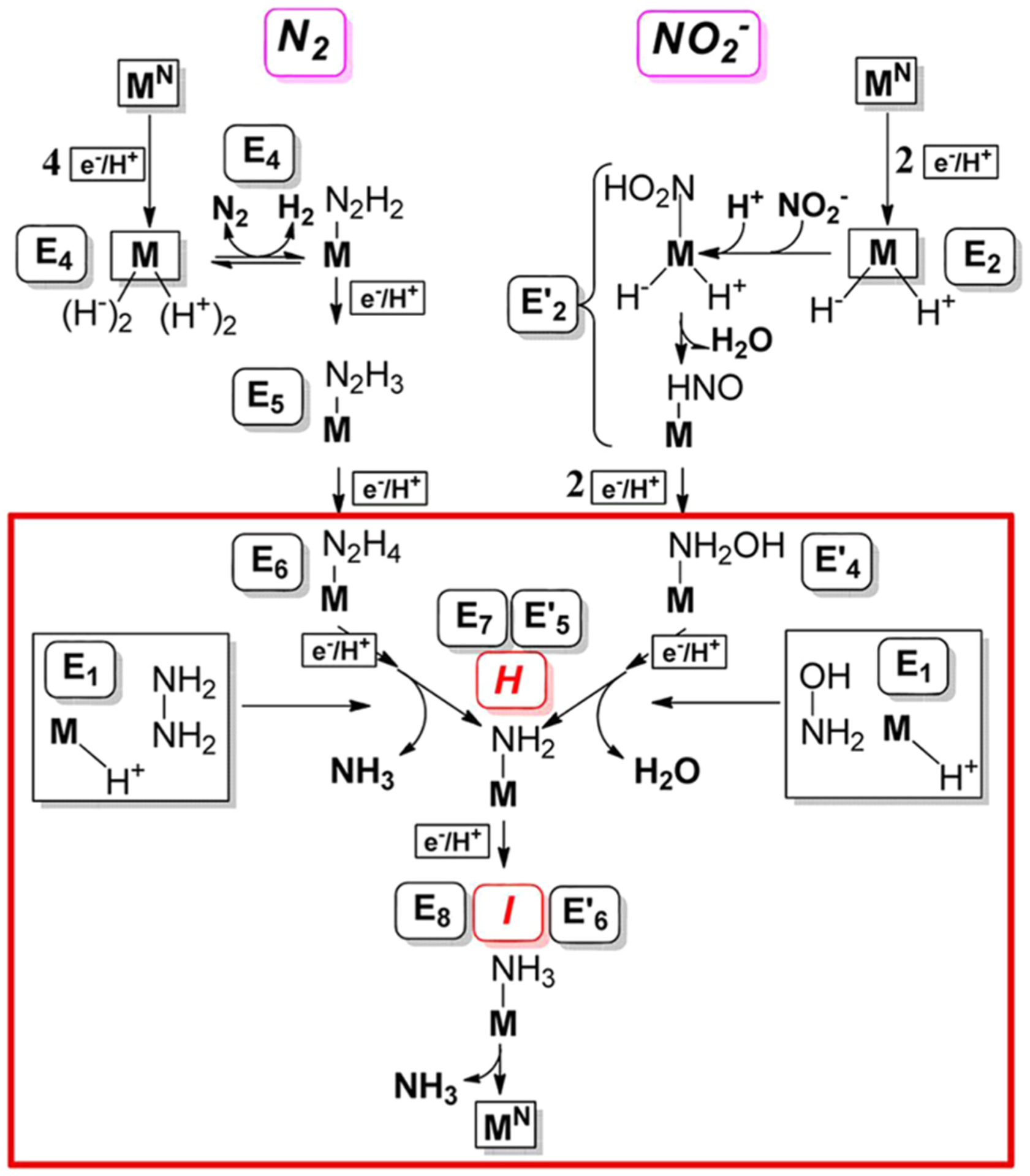

4.2. N2Hx Substrates

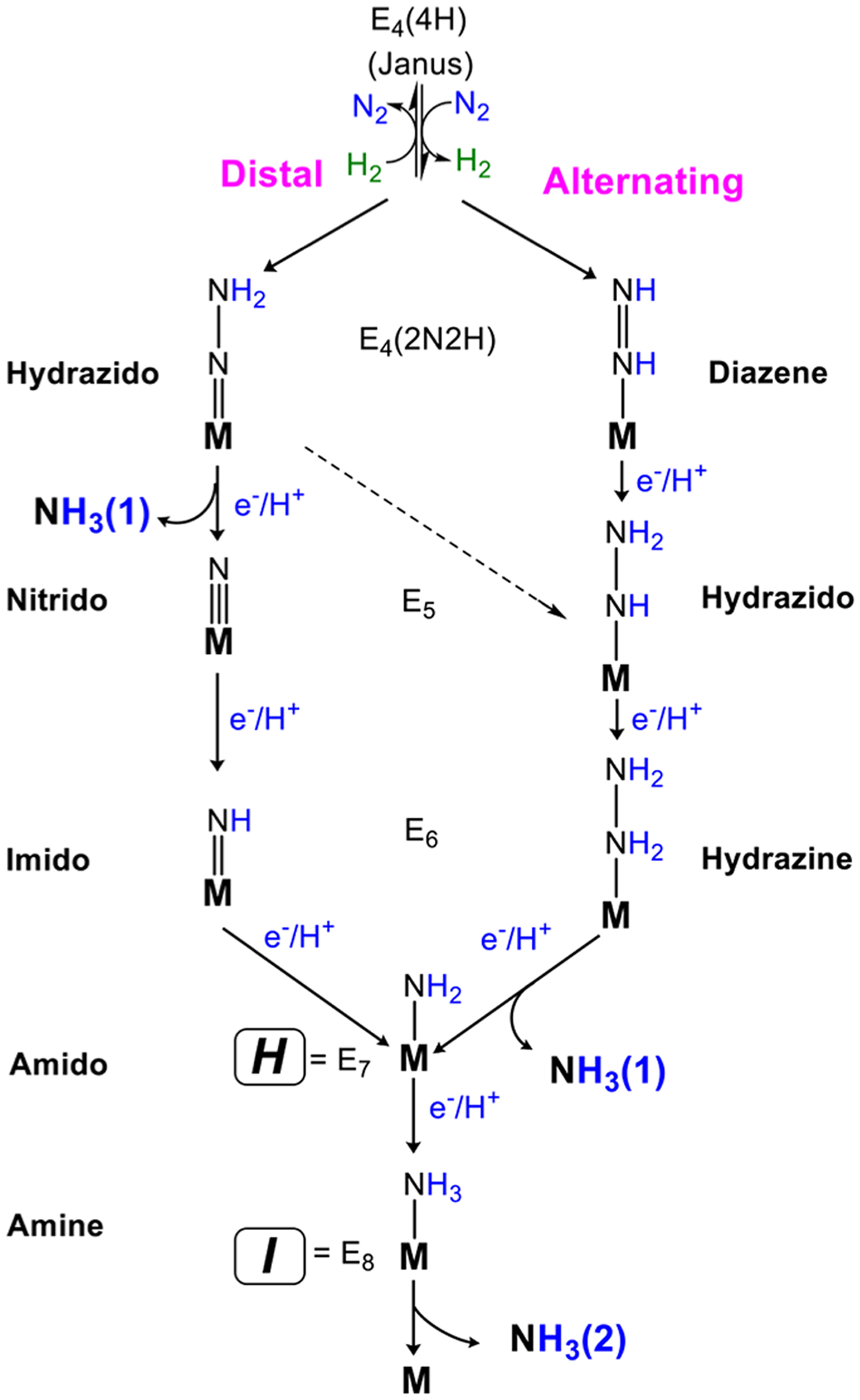

As shown in the re/oa kinetic scheme of Figure 3, following the formation of E4(2N2H), the catalytic cycle traverses four states that contain partially reduced species of N2.21,23 Researchers have long considered two competing proposals for this “second half” of the kinetic scheme, which invoke distinctly different intermediates, Figure 16. In the “distal” (D) pathway, utilized by N2-fixing inorganic Mo complexes,83,183–185 the distal N of Fe-bound N2 is hydrogenated in three steps. The first NH3 is then liberated with the addition of the fifth [e−/H+] overall, to generate the nitrido species, E5. This nitrido-N is then hydrogenated three times to yield the second NH3. In the “alternating” (A) pathway that has been suggested to apply to reaction at Fe of FeMo-co,175,186 the two N’s instead are hydrogenated alternately, with a four-electron and proton reduced species equivalent to hydrazine (N2H4) formed as the E6 intermediate. In this case, the first NH3 is only liberated during the next hydrogenation step, the formation of E7 (Figure 16).33,82 Peters et al. has proposed what might be called a hybrid-A pathway,182 in which E4 on the D pathway is converted to E5 on the A pathway. Consequently, as with the limiting A pathway, the first NH3 also is released with formation of E7, as shown.

Figure 16.

Proposed N2 reduction pathways with M representing the active site FeMo-cofactor. A distal reduction pathway (D) and an alternating reduction pathway (A) are displayed with plausible key intermediates. The hybrid-A pathway is indicated by a dashed arrow.182

Previous studies demonstrated that the diazene analogs methyldiazene (CH3-N=NH), dimethyldiazene (CH3-N=N-CH3) and diazirine (CH2N2) are substrates for nitrogenase, all being reduced to NH3, and CHx species.187,188 The early studies on these substrates have been reviewed.93 In 2007, the study of diazene (HN=NH) as a substrate for Mo-dependent nitrogenase was expanded through the use of in situ generation from azodiformate.189 The 4 [e−/H+] reduction of diazene produced two equivalents of NH3. The reduction of diazene was found to be inhibited by H2, which is also an inhibitor of N2 reduction.189 As can now be understood, in both cases the inhibition is a consequence of the re/oa mechanism as described in section 3. This result implies that diazene must enter the reaction pathway by forming the same diazene-level intermediate, E4(2N2H), as forms when N2 reacts with E4(4H).23 The addition of H2 then reverses the re/oa equilibrium, with the E4(2N2H) undergoing oa with loss of N2 to generate E4(4H). The E4(2N2H) could form in one of two ways: direct reaction with E0 or, as proposed in 2012,190 reaction with E2(2H) with loss of H2 through hydride protonation.

Recently it has also been shown that the 2 [e−/H+] reduction of hydrazine to produce two equivalents of NH3191 is efficiently achieved by remodeling of the α−70Val residue around FeMo-cofactor of Mo-nitrogenase with a smaller side-chain amino acid (Ala).192 In contrast to the H2 inhibition of diazene and N2 reduction, hydrazine reduction was not inhibited by H2. This again is consistent with the scheme of Figure 3. Once the delivery of [e−/H+] to E4(2N2H) has generated E5, the enzyme has passed the re/oa equilibrium stage and is no longer susceptible to inhibition by H2, while hydrazine appears on the A N2 reduction pathway at E6.190

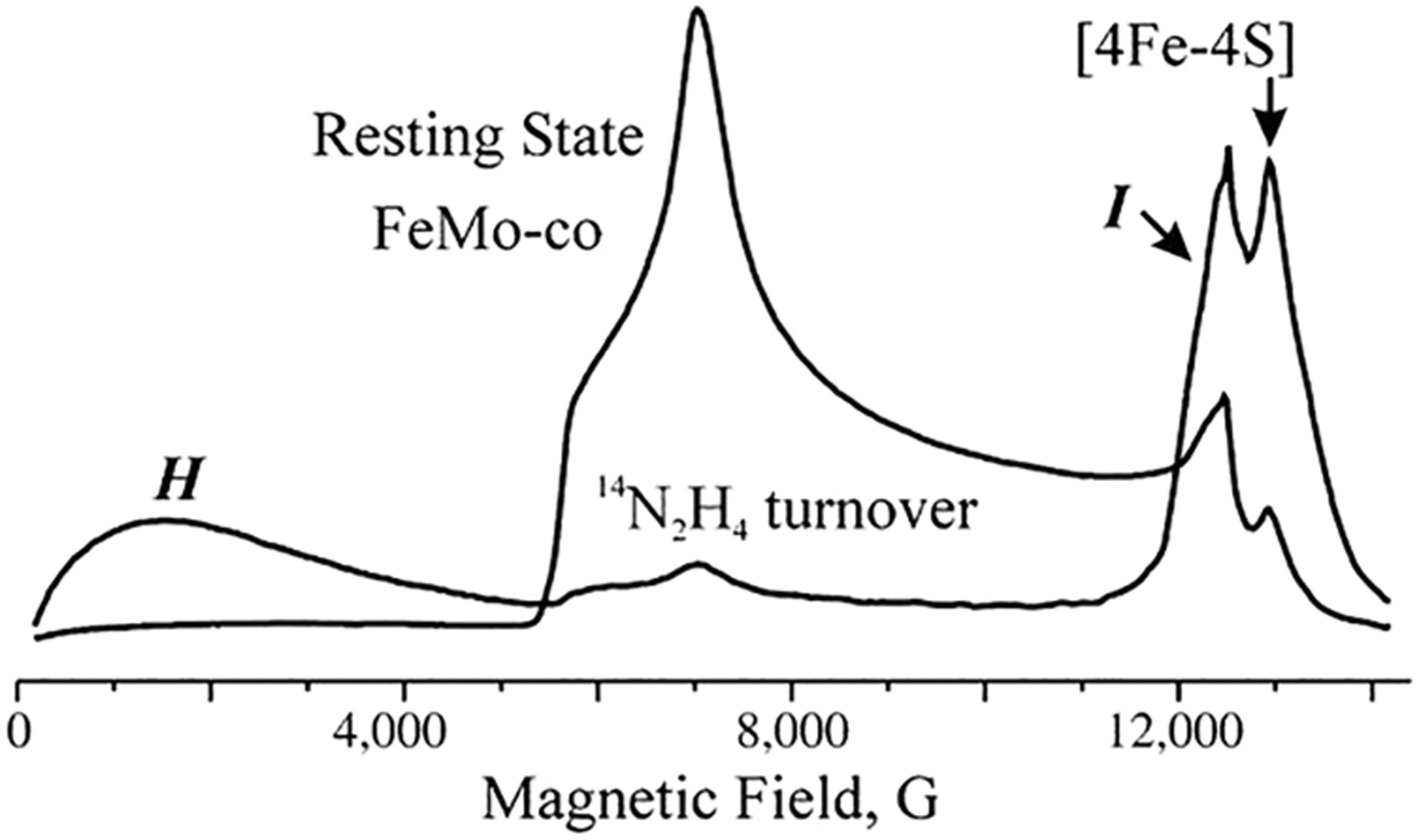

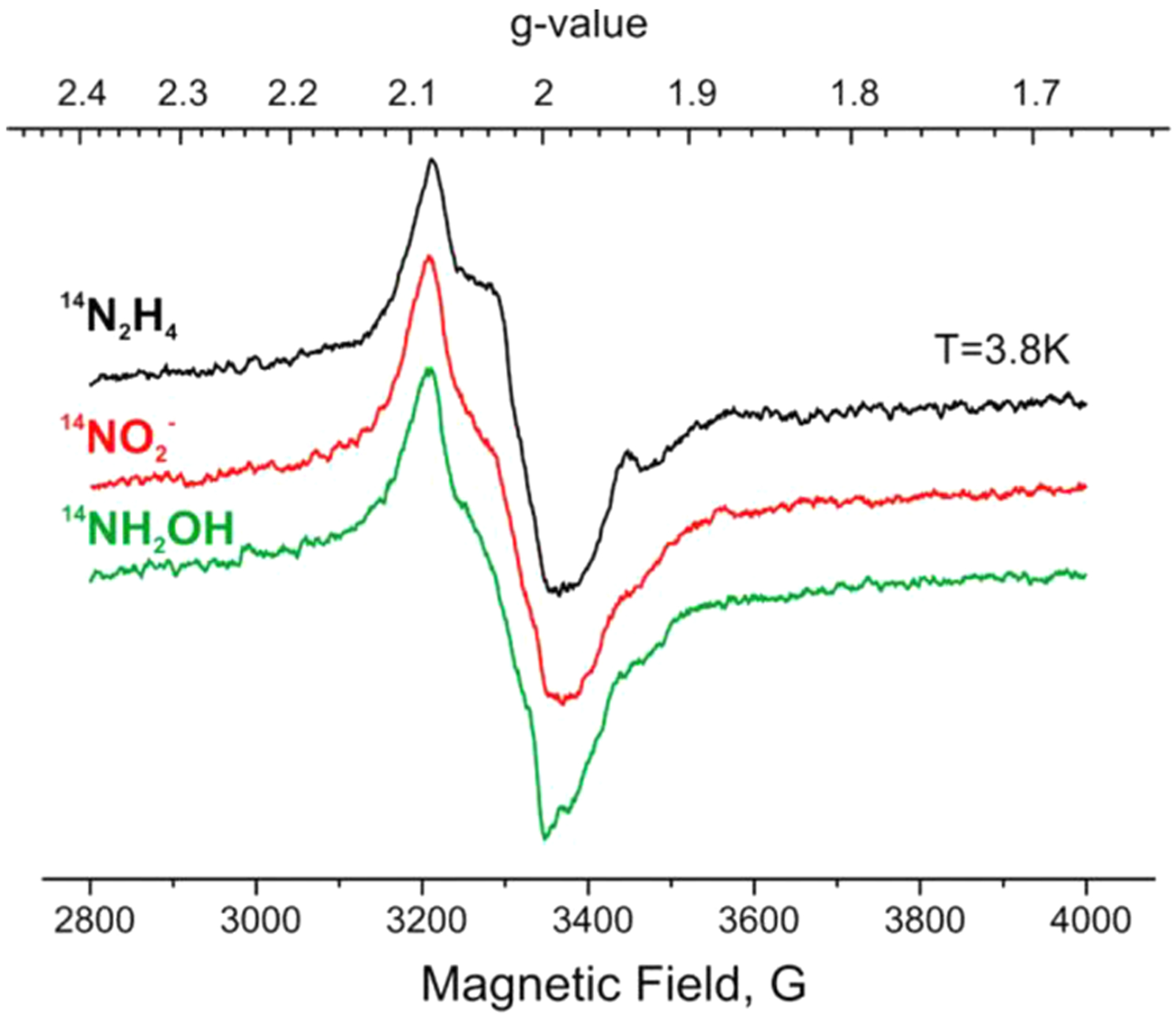

Two common intermediates have been freeze-trapped using MoFe protein variants with both diazene substrates (CH3-N=NH and HN=NH) and hydrazine N2H4 (Figure 17):188,189,192,194 a broad, low-field resonance H (non-Kramers state, S ≥ 2) EPR-detectable in Q-band at 2 K; a Kramers state, S = 1/2, with g = [2.09, 2.01, 1.98]), denoted, I.190 These intermediates have been fully characterized by X/Q-band EPR and 15N, 1,2H-ENDOR, HYSCORE, and ESEEM spectroscopic studies. Their enzymatic and chemical assignments are E7(NH2) = H with NH2− bound to FeMo-cofactor and E8(NH3) = I, with a bound NH3.190

Figure 17.

Q-band CW EPR spectrum of α−70Val→Ala/α−195His→Gln MoFe protein in the resting state and trapped during turnover with 14N2H4 as substrate. Kramers intermediate I and non-Kramers intermediate, H, are noted in the turnover spectrum. Reproduced with permission from ref 190. Copyright 2012 Authors. Published by PNAS.

4.3. NOx Substrates

Nitrite (NO2−), nitrous oxide (N2O), and hydroxylamine (NH2OH) all are reduced by nitrogenase.20 The recent characterization of nitrite as a nitrogenase substrate established that six-electron reduction of NO2− to NH3 by nitrogenase proceeds without the obligatory H2 evolution that is required for the reduction of N2.193 The kinetic observations and mechanistic implications of the first three of these substrates have been summarized in detail in an earlier review.20 Hydroxylamine was recently reported as a nitrogenase substrate, being reduced by two electrons to NH3 and H2O.193 The reduction of each of these substrates is not inhibited by H2, as in the case in the reduction of hydrazine. As with hydrazine, these results are as expected for reactions that involve intermediates that correspond to En, n > 4 (see above).

Freeze-trapping α−70Val→Ala/α−195His→Gln MoFe protein under turnover conditions with NO2− or NH2OH as substrate resulted in the same two EPR-active species (S = 1/2 and S ≥ 2) trapped with diazenes or hydrazine as substrate (Figure 18). As confirmed by 1H and 15N pulsed ENDOR study, the S = 1/2 intermediates of NO2− or NH2OH are E8(NH3) = I; 14/15N ESEEM studies confirmed the identity of the non-Kramers intermediates as E7(NH2) = H (S ≥ 2) for NO2− or NH2OH.193

Figure 18.

X-band EPR spectra of α−70Ala/α−195Gln MoFe protein turnover samples prepared with N2H4 (black), NO2− (red), and NH2OH (green) substrates. Reproduced with permission 193. Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

4.4. Mechanisms and Insights

The study of these N-based alternative substrates has provided evidence regarding the nature of the reaction pathway for N2 reduction: D or A (Figure 16). An alternating pathway for N2 hydrogenation is supported by the observation that (i) hydrazine is a product of N2 reduction by V-nitrogenase,195 which also functions through the re/oa mechanism,153,154 and (ii) hydrazine was detected as a product by acid or base quenching of Mo-nitrogenase during N2 reduction.86,87 Of course, as seen in Figure 16, in the D pathway the N-N bond is cleaved before hydrazine can be formed and so could not be formed during catalysis, thus indicating that the A pathway is followed by nitrogenase.

The kinetic and spectroscopic observations of nitrite and hydroxylamine reduction by nitrogenase led to the proposal of a [6e−/7H+] reduction mechanism of nitrite by nitrogenase (eq 6) as shown in the right panel of Figure 19.193 In this mechanism, NO2− and one proton bind to FeMo-cofactor at the E2 state. After one water molecule was released, the resulting M-[NO+] species reacts with the hydride on the same cofactor to avoid the formation of an M-[NO] “thermodynamic sink”.196 The formation of an M-HNO species is similar to the reduction of heme-bound NO to bound HNO through hydride transfer from NADH by P450 NO reductase.197 The M-HNO intermediate is then converted to further reduced species through a pathway analogous to the nitrite reduction by cytochrome c nitrite reductase (ccNIR),198–201 including intermediates H (M-NH2) and I (M-NH3).190

| (6) |

Figure 19.

Comparison of the proposed reduction pathways of N2 (left) and nitrite (right) by nitrogenase (M represents FeMo-cofactor). An intermediate, labeled En on N2 pathway and Em′ on nitrite pathway, has accumulated n or m [e−/H+]. (Boxed Region) Convergence of pathways for nitrite and N2 reduction by nitrogenase, as discussed in the text. Within this region, boxed reactions of E1 show the most direct routes by which N2H4 and NH2OH join their respective pathways. Reproduced with permission from ref 193. Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

Even though the binding and reduction mechanism of N2 and NO2− are totally different, the generation of common intermediates H and I from both the di-N substrates (N2H2 and N2H4) and mono-N substrates (NO2− and NH2OH) further confirmed the previous assignments of intermediate H to M-NH2 and I to M-NH3, and their assignment to E7 and E8, respectively.190,193 These results are understood as arising from a convergence of the reduction pathways of N2 and NO2− in the late stage of the corresponding catalytic cycles as highlighted in the red box in Figure 19.193

Hydrazine and hydroxylamine were proposed to bind to E1 and undergo bond cleavage, forming the intermediate H, and NH3 and H2O, respectively.190,193 These results are consistent with the proposed alternating N2 reduction pathway by nitrogenase in which the first NH3 is released after delivery of the seventh [e−/H+] to the N2H4-bound E6 state to form intermediate H. The intermediate H accepts one last pair of [e−/H+] to form intermediate I, which regenerates the E0 state to finish one catalytic cycle by releasing the second NH3.21,23,190

5. C-BASED SUBSTRATES

In addition to the nonphysiological N-based substrates, nitrogenase interacts with a broad range of carbon (C)-based substrates/inhibitors. The utilization of these C-based substrates/inhibitors has greatly expanded the ability to probe nitrogenase mechanism, and their reduction has been reviewed.20,39,40,203 In this section, we will focus on the progress in studying C-based substrates/inhibitors of nitrogenase since 2013,40 referring to earlier work when necessary for clarity.

5.1. Alkyne Substrates

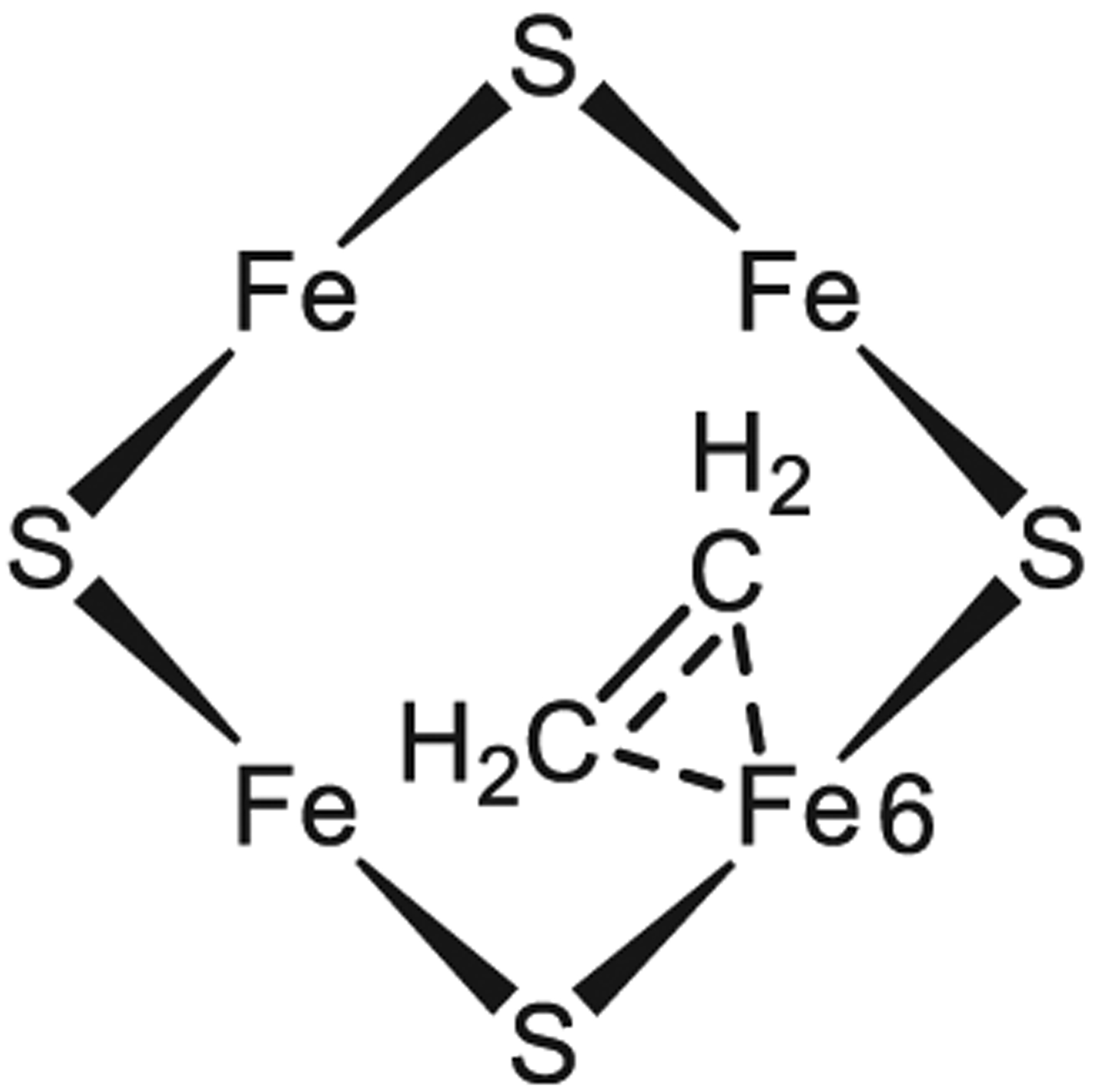

Alkynes were widely used as substrates and inhibitor in probing the substrate-binding sites and reduction mechanism of nitrogenase over the last half-century.20,39,40,179 Acetylene was the first alkyne discovered early as an alternative substrate of nitrogenase,204 with pioneering works studying the steady-state EPR of wild type205 and α−195His→Gln-substituted MoFe protein206 with acetylene as substrate. The X- and Q-band EPR spectra of the freeze-trapped species exhibited three simultaneously generated S = 1/2 signals: a rhombic SEPR1 signal with g = 2.12, 1.98, 1.95, a rhombic SEPR2 signal with g = 2.007, 2.000, 1.992, and a minor isotropic SEPR3 signal with g ≈ 1.97.206,207 Initial 13C and 1H ENDOR measurements on the SEPR1 signal suggested that it arises from a substrate complex, with two C2H2-derived species bound to the cofactor, one of them being a C2H2 bound to the FeMo-cofactor by bridging two Fe ions of the Fe2,3,6,7 face.207 However, results described directly below, which were obtained for an intermediate trapped during turnover of the alkyne propargyl alcohol with the α−70 Val→Ala-substituted MoFe protein suggested that this interpretation be reexamined. Subsequent, improved ENDOR measurements on SEPR1, which included 57Fe ENDOR measurements, revealed interactions with three distinct carbon nuclei, again indicating that at least two C2H2-derived species are bound to the cofactor, but they suggested that this intermediate in fact contains an ethylene product bound as a ferracycle to a single Fe of a two-electron reduced (E2) FeMo-cofactor (Figure 20).202

Figure 20.

Schematic representation of chemical structure of SEPR1 species at E2 state, highlighting the ferracycle formed by C2H4 binding to Fe6 as proposed in literature.202 The 4Fe4S face represents the same orientation as in Figure 2.

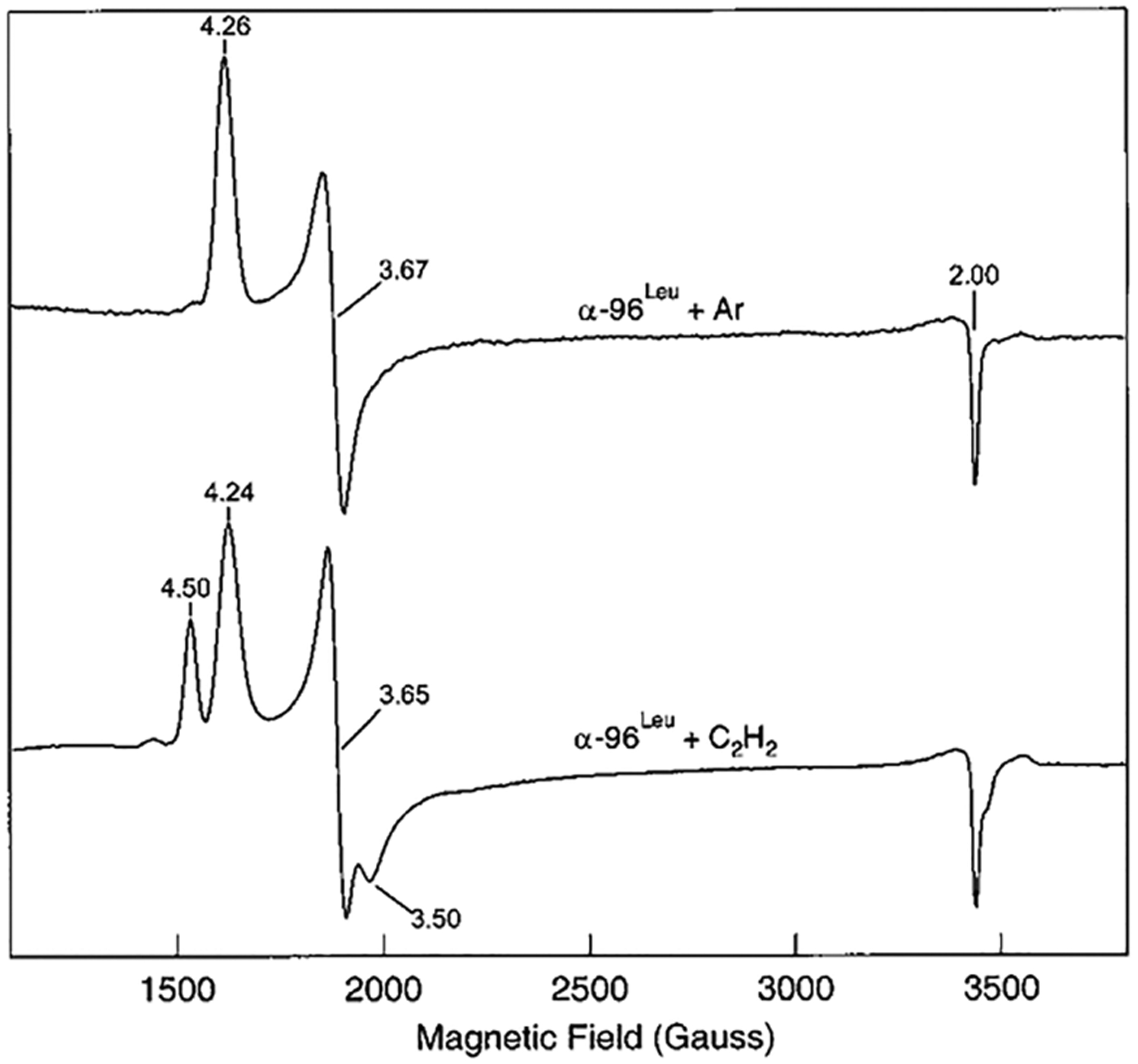

It was long held that FeMo-cofactor contained within the MoFe protein required the accumulation of one or more electrons before any substrate or inhibitor could interact.20,209 This conclusion was drawn from the lack of significant perturbations of the resting state (E0) FeMo-cofactor EPR signal line shape upon the addition of any inhibitors or substrates.20 This situation changed with the report that when the α−96Arg, located on one FeS face of FeMo-cofactor within the MoFe protein, was substituted by a series of other amino acids, the resulting MoFe protein variants showed perturbations of the FeMo-cofactor EPR signal (S = 3/2, g = 4.26, 3.67, 2.00) upon incubation of the resting state enzyme with the substrate acetylene or the inhibitor cyanide (CN−).208 Both acetylene204,210,211 and cyanide212–214 were long ago reported as substrates for nitrogenase under turnover conditions, being reduced to ethylene (C2H4) and methane (CH4) and ammonia (NH3), respectively. Incubation of resting-state α−96Arg→Leu-substituted MoFe protein with acetylene or cyanide was found to decrease the normal FeMo-cofactor signal with appearance of new EPR signals having g = 4.50 and 3.50 (Figure 21), and g = 4.06, respectively. Subsequent 13C ENDOR studies revealed direct, but weak, interactions between acetylene or CN− and the resting-state FeMo-cofactor.208 These observations were the first to show that substrates/inhibitors can interact with the resting state FeMo-cofactor contained within the MoFe protein.

Figure 21.

X-band EPR spectra of α−96Leu MoFe protein under nonturnover conditions in the absence (top trace) and presence (bottom trace) of acetylene. Reproduced with permission from ref 208. Copyright 2001 American Chemical Society.

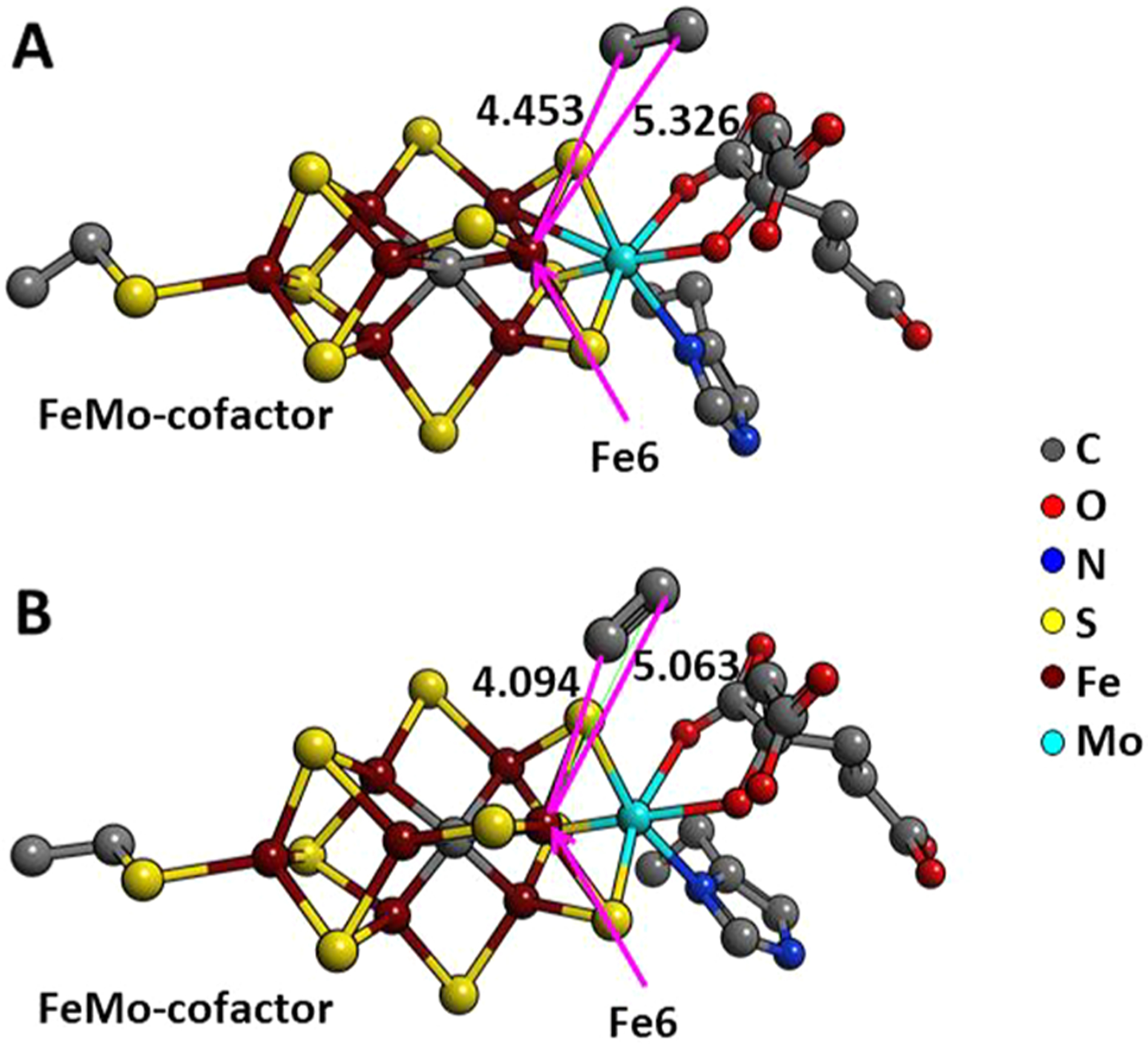

Capitalizing on this finding, a recent X-ray crystallographic study of α−96Arg→Gln-substituted MoFe protein in the presence of acetylene resulted in the first crystal structure with a substrate molecule, acetylene, captured near the active site FeMo-cofactor.215 In the 1.70 Å crystal structure, the acetylene is located 4–5 Å away from Fe6 atom, which was supported by DFT calculations (Figure 22).215 These results are consistent with the previous findings that nitrogenase binds some substrates at the 4Fe4S face of FeMo-co approached by the side chains of α−70Val and α−96Arg.33,36 An 1H and 57Fe ENDOR study using wild-type and Nif V− MoFe proteins from Klebsiella pneumoniae also revealed that acetylene binding to the resting-state MoFe protein can perturb the FeMo-cofactor environment.216

Figure 22.

Comparison of the acetylene location at the FeMo-cofactor. The acetylene location at the FeMo-cofactor is compared between X-ray (A) and DFT optimized structures (B). The interatomic distances are shown with red lines. Reproduced with permission 215. Copyright 2017 Elsevier, Ltd.

The first detailed characterization of alkyne-reduction intermediates, alluded to above, was carried out on states freeze-trapped during the turnover of nitrogenase modified by substitution of the valine at α−70 position in MoFe protein by alanine.109,217,218 This substitution allows the reduction of longer-chain alkyne substrates,219,220 such as propargyl alcohol (HC≡CCH2-OH).217 When the α−70Val→Ala-substituted MoFe protein was frozen in liquid nitrogen during steady-state turnover with propargyl alcohol as substrate, the S = 3/2 EPR spectrum of the FeMo-cofactor was changed to a new S = 1/2 signal.217,218 Using 1,2H- and 13C-ENDOR spectroscopies, it was demonstrated that this S = 1/2 signal originates from the FeMo-cofactor having the alkene allyl alcohol (H2C=CHCH2-OH) reduction product bound as a ferracycle to a single Fe as shown in section 3 (Figure 4).109

This structural assignment was later supported by the EXAFS and NRVS examination of the same intermediate.162 A similar S = 1/2 signal was also observed when propargyl alcohol was replaced by propargyl amine (HC≡CCH2-NH2) as substrate. Trapping of these two intermediates was shown to be dependent on pH and the presence of histidine at α−195 position.218 These results suggested that these intermediates are stabilized, and thereby trapped, by H-bonding interactions between either the −OH group or the −NH3+ group and the imidazole of α−195His. Theoretical calculations refining the binding mode and site pointed to η2 coordination at Fe6 of the FeMo-cofactor, as visualized in Figures 4 and 21.218

5.2. CO as Inhibitor and Substrate

CO was described as an inhibitor of wild-type Mo-nitrogenase in early studies, being shown to inhibit the reduction of all substrates except protons to make H2.20,93,221 CO inhibition of proton reduction was observed when the first sphere (substitution of homocitrate by citrate as in the NifV− mutant)222,223 or secondary sphere environment of the FeMo-cofactor222,224,225 was changed. Similar CO inhibition of proton reduction was also seen for Mo-nitrogenase under high pH conditions226 and for V-nitrogenase.227,228 Recently, CO was reported to stimulate the H2 production catalyzed by three MoFe protein variants, α−277Cys, α−192Asp, and α−192Glu under high-electron flux conditions but not under low-electron flux conditions. These intriguing observations are apparently at odds with the observation that CO displays either no inhibitory or inhibitory effect on proton reduction catalyzed by Mo- and V-nitrogenases, as noted above.229

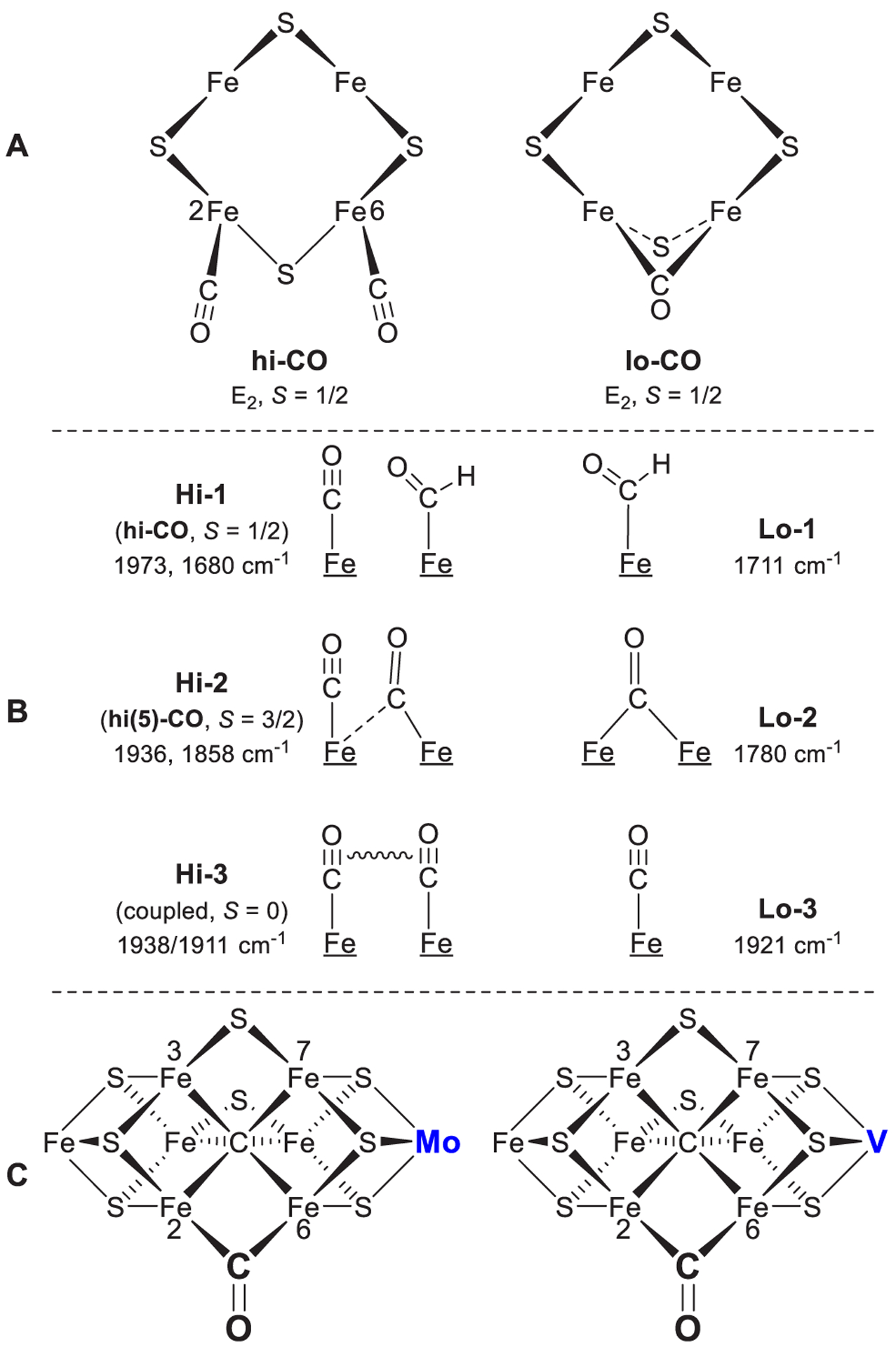

Trapping of nitrogenase by freezing during turnover under CO revealed a loss of the EPR spectrum of the resting state FeMo-cofactor and appearance of two major different EPR signals.205,230–234 In the presence of low concentrations of CO ([CO]:[FeMo-cofactor] ≤ 1:1), the S = 3/2 spectrum of FeMo-cofactor changed to an S = 1/2 spin state giving rise to a new rhombic EPR signal (denoted lo-CO) with g = 2.09, 1.97, 1.93. At higher concentrations of CO (≥0.5 atm), an axial EPR signal (S = 1/2, called hi-CO) was observed with g = 2.17, 2.06, 2.06.205,231–234 In addition to these trapped CO complexes, a small population of species at S = 3/2 spin state, so-called hi(5)-CO, has been observed under high CO concentrations and higher electron flux in wild-type233 and variant MoFe proteins.222,234

These trapped CO complexes of FeMo-cofactor have been well studied by advanced spectroscopic methods. ENDOR studies of lo-CO and hi-CO complexes using different isotopologues of CO and FeMo-cofactor characterized the two CO complexes.202,230,235–238 Key conclusions from these studies were that in lo-CO the C of a single CO bridges two Fe ions (end-on mode) and in hi-CO, two CO terminally bind to two Fe ions in the “waist” of the FeMo-cofactor (Figure 23A). The hi(5)-CO complex has been suggested to contain two bridging CO molecules on the FeMo-cofactor.222 Finally, EPR-monitored photolysis experiments revealed that a terminal CO of hi-CO complex is photolabile, causing the state to reversibly convert to lo-CO. In contrast, both lo-CO and hi(5)-CO complexes are photostable.239

Figure 23.

Schematic structures of CO complexes as proposed based on (A) EPR/ENDOR,202,230,235–238 (B) IR-monitored photolysis,240–242 and (C) X-ray crystallography of Mo-nitrogenase143 and EPR comparison of Mo- and V-nitrogenases.243 The presence of a bound carbonate in the VFe-co was revealed later by X-ray crystallography.

The En level of lo-CO and hi-CO remain a matter of considerable interest. It has been reported that lo-CO and hi-CO can be interconverted by adding CO to the former or pumping CO off of the latter, without redox or catalytic processes, thus demonstrating that they are at the same En level.233 In addition, lo-CO can be converted to E0 by extensive pumping, which suggests that all three states are at the same, MN (E0), redox level,233 an idea consistent with 57Fe ENDOR measurements.145,237 However, CO cannot bind to FeMo-cofactor in the resting state, and can only bind to the cofactor in a state formed during turnover under CO.233 One possibility is that lo-CO is indeed an E2 state, and we have discussed this possibility.202 However, such a state should have the two reducing equivalents stored as a hydride, and no such 1H ENDOR signal is observed.150,236 Thus, it appears unlikely that lo-CO is an E2 state. To explain the combined observations one might imagine that CO binds to FeMo-cofactor in an E2 state, or in an E1 state that then receives a second electron, and that the resulting CO-bound E2 state loses H2 to form the observed lo-CO, which indeed is at an E0 redox level. The differing net spins, S = 3/2 for resting state, S = 1/2 for CO-bound states, would then merely reflect the influence of the CO binding. Clearly, a reexamination of the lo-CO state, including 95Mo ENDOR and DFT computations, would seem to be in order.

Although EPR and ENDOR give the optimal insights into properties of intermediates with half-integer spin states (S = 1/2, 3/2, 5/2, …), rarely (intermediate H, section 4.2) can it probe intermediates with integer spin (S = 0, 1, 2, …).190,193 Stopped-flow FTIR studies are equally effective for all spin states.244–246 Recently, IR-monitored photolysis studies of complexes of wild-type and two MoFe protein variants trapped during turnover with low electron flux under hi-CO conditions displayed a more complex landscape of hi-CO complexes.240–242 Three different hi-CO complexes (designated as Hi-1, Hi-2 or hi(5)-CO, and Hi-3) were observed with absorptions at different energy levels. All hi-CO complexes have two CO bound to FeMo-cofactor and can reversibly release one CO to generate lo-CO complexes with one terminal, bridging, or protonated CO species. The three hi-CO complexes all have one CO terminally bound to FeMo-cofactor with the other ligand as a terminal, semibridging, or bridging/protonated CO ligand (Figure 23B).240–242 Further photolysis and DFT study of Hi-3 with C-O stretching frequencies at 1938 and 1911 cm−1 revealed that it has two terminal CO ligands bound to two adjacent Fe atoms in the FeMo-cofactor with an EPR silent S = 0 spin state.241,242 DFT calculations of the C-O stretching frequencies of hi-CO complexes also suggested that C-O frequencies at 1973 and 1680 cm−1 in IR of Hi-1 species originated from a terminal −CO and a partially reduced −CHO ligands bound to two adjacent Fe sites as well, consistent with the EXAFS and NRVS observations for the wild-type enzyme.242 Recent NRVS studies of nitrogenase under high CO conditions revealed that the FeMo-cofactor undergoes significant structural perturbation upon −CO/−CHO binding.242 The identification of Fe-CO stretching and Fe-C-O bending modes in the range of 470–560 cm−1 in NRVS provided the first confirmation that binding is indeed at Fe sites,23,110 extending the many studies noted above that showed the heterometal, Mo in FeMo-cofactor, may tune the properties of the cofactor, but is not directly involved in valence changes or substrate reduction.114,151

As described above, structures of the FeMo-cofactors with CO or CO-derived ligands have been proposed based on the different spectroscopic studies (Figure 23). In 2014, Rees et al.143 reported the first X-ray crystal structure of a CO-bound state of the MoFe protein with 1.5 Å resolution, using crystals obtained from a solution, following turnover in the presence of CO and C2H2. Surprisingly, the structure showed the bridging CO proposed for lo-CO, but it was found to bind to the FeMo-cofactor by replacing one of the belt sulfide ligands, S2B (Figure 23C). Correspondingly, a recent EPR study of the CO-modified MoFe protein generated under the same conditions that yielded the CO-modified crystals yielded a spectrum that almost exactly matches that reported for lo-CO.243 The dissociation of a belt sulfide is a central factor in the developing view, noted above, that FeMo-cofactor is not structurally rigid71,143 during turnover.

The exchange of CO for S2− on the FeMo-cofactor is reversible under turnover conditions.143 Thus, CO inhibition of acetylene reduction could be recovered when the CO-bound MoFe protein crystals were dissolved and incubated in an assay mixture, and the structure of MoFe protein crystals obtained from this mixture revealed the loss of the bridging CO ligand and the reinstallation of the belt sulfide, thus restoring the resting state FeMo-cofactor structure. Even though a plausible sulfide binding site (SBS) was proposed, the origin and mechanism of insertion of the belt sulfide ligand are still not clear.

About a decade ago, CO was discovered to be a substrate of V- and Mo-nitrogenases producing both CH4 and short-chain hydrocarbons as products.227,228,247 Two or more CO could be reduced and coupled to make multi-C hydrocarbons at low rates when turned over with Fe protein and MgATP. The reactivity of FeMo-co- and FeV-co-reconstituted apo-MoFe protein (apo-NifDK) toward CO reduction has also recently been explored.248 It was found that both FeMo-co- and FeV-co-reconstituted NifDK protein showed similar hydrocarbon product profiles from CO to that of wild-type Mo-nitrogenases, with much lower rates compared to that by V-nitrogenase.227,228 However, a ~100 times increase of hydrocarbon formation from CO reduction was observed when FeMo-cofactor was housed in a VFe protein scaffold compared to that housed in its native MoFe protein scaffold.249 These results highlighted a combined contribution from the protein environment and cofactor properties toward CO reduction.

It has also been reported that CO can bind to the V-nitrogenase in the absence of Fe protein/MgATP (nonturn-over) as electron-delivery agent, but instead in the presence of the reductants dithionite (E0 = −0.66 V), EuII-EGTA (E0 = −0.88 V), and EuII-DTPA (E0 = −1.14 V).243 The comparison of the EPR spectrum of the CO-bound VFe protein to that of the CO-modified MoFe protein led the authors to propose replacement of a belt-sulfide by a bridging CO ligand (Figure 23C).143,243 They reported that the CO of this CO-bound VFe protein could be further reduced to methane when subjected to turnover condition with Fe protein (VnfH)/MgATP and dithionite, revealing the relevance of this CO-bound state to the catalytic turnover of CO as substrate.243

It has been long believed that CO does not bind to FeMo-cofactor of Mo-nitrogenase in the resting state (E0), which is further supported by a recent electrochemical study of CO interaction with FeMo-cofactor in MoFe protein with EuIII/II-L (L = BAPTA, EGTA, DTPA) as electron mediators.250 However, the binding of CO to FeV-cofactor in the absence of Fe protein/MgATP (resting-state VFe protein as suggested)243 indicates that it might be risky to simply expand the concept of resting-state E0 of Mo-nitrogenase to V- and Fe-nitrogenases without careful consideration of the fine-tuning effect of heterometals (Mo, V, and Fe) and secondary environments on the electronic structure of FeM-cofactor. For example, to date, the FeV-cofactor in as-isolated VFe protein always has a CO32− ligand that does not exist in any MoFe protein crystal structures observed.58,59 Clearly, CO interacts with nitrogenases in complex ways, with some aspects still needing resolution.

In 2013, the possible connection between CO reduction and the interstitial carbide in the active site FeMo-cofactor was explored.251 It was found that reconstitution of apo-MoFe protein with 14C-labeled FeMo-cofactor in the resting state and upon turnover with acetylene and N2 did not show any dilution of the 14C-label in the active site, indicating that the interstitial carbide cannot be exchanged during turnover. Moreover, the GC-MS characterization of the hydrocarbon products from reaction mixtures with the combined use of 12/13C-enriched CO substrate and the carbide in the active site revealed that the interstitial carbide could not be used as a substrate and incorporated into the hydrocarbon products.251 These results are consistent with a role for carbide in stabilizing the structural integrity of FeMo-cofactor71 as it proceeds through different conformational states during catalysis.

5.3. CO2 as Substrate

CO2 was reported as a substrate for nitrogenase in 1995, being reduced by two electrons to CO.252 The form of CO2 (CO32−, HCO3−, and CO2) that is the substrate remains unclear. Recently, it was reported that in the crystal structures of V-nitrogenase a CO32− ligand replaced one of the belt-sulfide ligands of the active site FeV-cofactor (Figure 2).58 This proposed CO32− ligand is also present in a plausible turnover-relevant structure of the FeV-cofactor,59 further complicating the origin of this CO32− ligand and the relevance to the CO2 reducing ability of nitrogenases.

Later studies reported that CO2 could be reduced by eight electrons/protons to methane (CH4) by a remodeled Mo-nitrogenase having amino acid substitutions α−70Val→Ala/α−195His→Gln.254 In 2016, light-driven in vivo CO2 reduction to CH4 by an anoxygenic phototroph, Rhodopseudomonas palustris (R. palustris), which expressed the same remodeled Mo-nitrogenase, was reported.255 This catalytic ability was conferred upon R. palustris by use of a variant of the transcription factor NifA that can activate expression of nitrogenase under all growth conditions.256–259 More recently, the in vivo CH4 production from CO2 reduction has been confirmed to be catalyzed by the wild-type Fe-only nitrogenase from R. palustris and several other nitrogen-fixing bacteria.260 The CH4 production by the Fe-only nitrogenase in R. palustris was found sufficient to support the growth of an obligate CH4-utilizing Methylomonas strain. These results suggest that active Fe-only nitrogenase, present in diverse organisms, contributes CH4 that could shape microbial community interactions.260

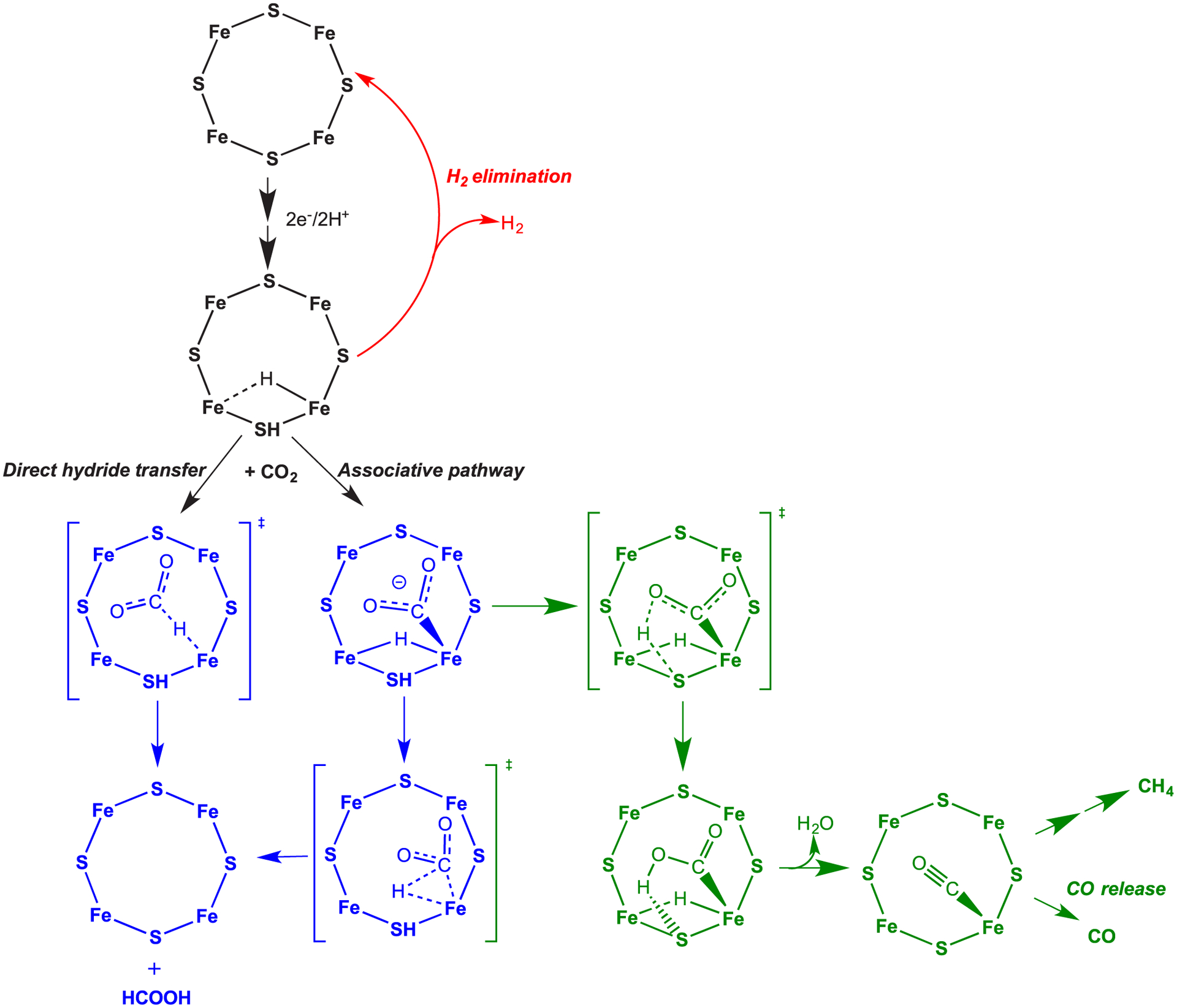

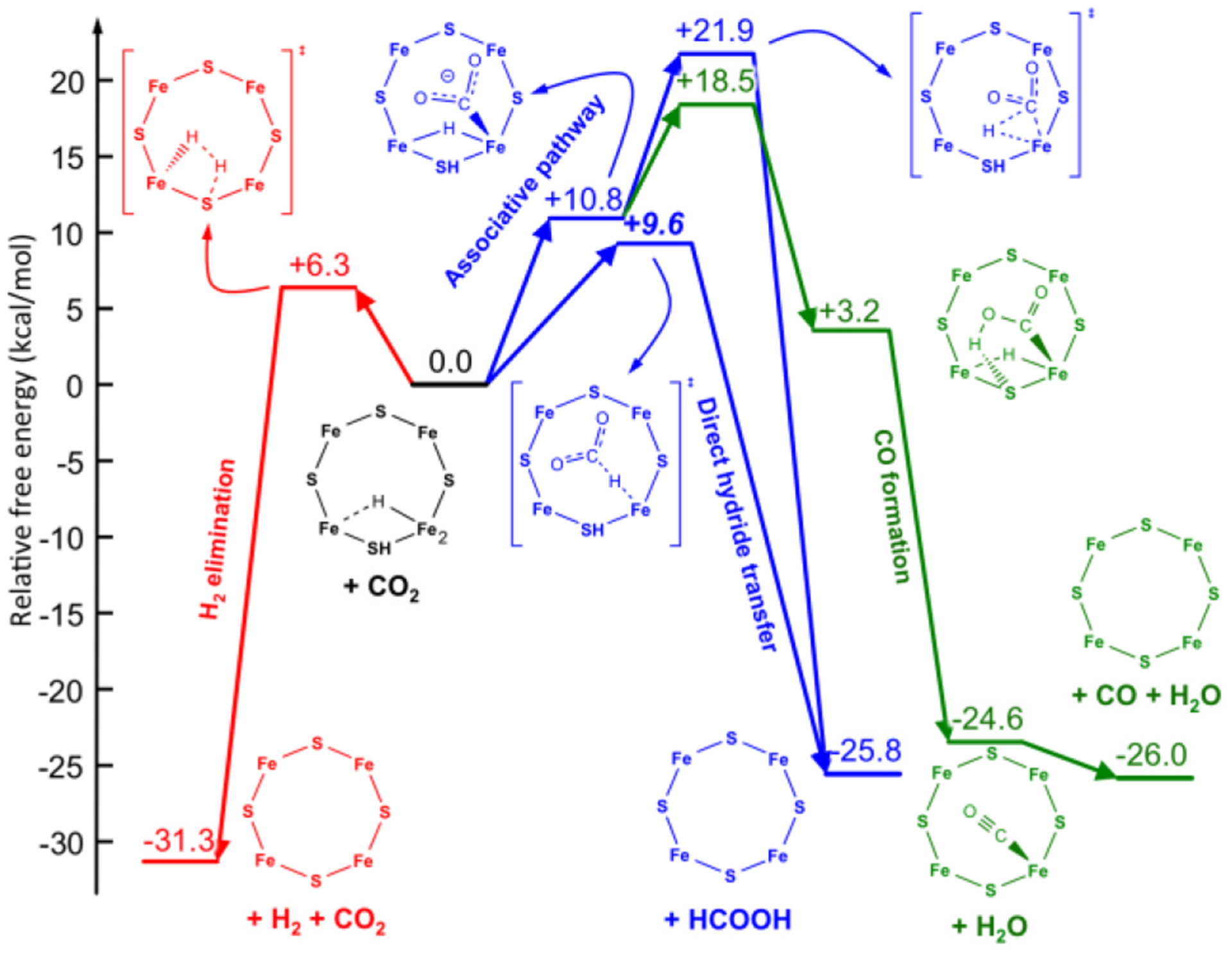

Recently, it was discovered that Mo-nitrogenase catalytically reduces carbon dioxide (CO2) to formate (HCOO−) at rates >10 times faster than that of CO2 reduction to CO and CH4.253 This reaction was not inhibited by H2, indicating that CO2 reduction does not involve the re/oa equilibrium central to N2 binding/activation, as expected if the reduction occurs a En states with n < 4.253 In fact, DFT calculations136 on the doubly reduced FeMo-cofactor (E2 state) with a Fe-bound hydride and S-bound proton favor a direct reaction of CO2 with the hydride (direct hydride transfer reaction pathway, see Figure 24 and 25, lower blue pathway), with facile hydride transfer to CO2 yielding formate. In contrast, a significant barrier is observed for reaction of Fe-bound CO2 with the hydride (associative reaction pathway, Figure 25, upper blue pathway), which leads to CO and CH4. Importantly, computations revealed that protein residues above the reactive face of the FeMo-cofactor hamper the CO2 access to the hydridic hydrogen. In particular, steric hindrance from the side chain of α−70Val or α−96Arg introduces a barrier for the direct hydride transfer favoring the competitive elimination of H2 over HCOO− formation. Consistent with this finding, MoFe proteins with amino acid substitutions near FeMo-cofactor (α−70Val→Ala/α−195His→Gln) are found to significantly alter the distribution of products between formate and CO/CH4.253 The formate formation by Fe-nitrogenase reduction of CO2 was also reported to have a higher efficiency than that of Mo-nitrogenase.261

Figure 24.

Possible CO2 reduction pathways. CO2 activation at one FeS face of the E2 state of FeMo-co is shown. The E2 state is proposed to contain a single Fe-hydride and a proton bound to a sulfide shown bound to one face of FeMo-co. Reduction to formate (blue pathways) can go by either direct hydride transfer or an associative pathway. A pathway to formation of CO and CH4 is shown in the green. Adapted with permission from ref 253. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

Figure 25.

Computed free energy diagram for CO2 reduction and H2 formation occurring at the E2 state of FeMo-cofactor. Reproduced with permission 253. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

The analysis of the electronic properties of FeMo-cofactor during the hydride transfer revealed a strong charge transfer from the σ(Fe-H) bonding orbital to the π*(C=O) antibonding orbital, which results in the heterolytic Fe-H → Fe+ + H− bond cleavage and the transfer of the hydride to CO2. The exergonic nature of the direct hydride transfer (ΔG0 = −26 kcal/mol) suggests that the hydricity of the E2 state, ΔGH−, is sufficient to transfer a hydride to CO2 to generate formate, that is, the hydricity is below that of formate (HCOO− → CO2 + H−, ΔGH− = +24.1 kcal/mol).262

The same computational investigation revealed a pathway leading to the formation of CO from E2(2H)-CO2, which starts with the exergonic transfer of the protic S-H hydrogen to one of the oxygen atoms of CO2 (Figure 25, green pathway).253 Although the small size of the adopted computational models introduces a rather large uncertainty, initial protonation of CO2 by other ionizable residues, such as α−96Arg, was found very unlikely. The formation of CO proceeds with the transfer of the Fe-H hydrogen (as a proton rather than a hydride) to that oxygen, which results in the exoergic dissociation of a water molecule.253

The competitive formation of H2 from the E2(2H) state was also investigated computationally (Figure 25, red pathway). It was found that the release of H2 is a facile and exergonic process (ΔG0 = −31.3 kcal/mol). The exergonic nature of the formation of H2 is consistent with the observation that H2 cannot reduce FeMo-cofactor. It is of interest to point out that, as with the direct hydride pathway for the CO2 reduction, the Fe-H behaves as a hydride that is protonated by S-H, with the overall H2 elimination driven by a σ(Fe-H) to σ*(S-H) charge transfer.253

In a separate study of CO2 reduction by nitrogenases, it was found that both Mo- and V-nitrogenases can reduce CO2 to CO yielding substoichiometric amounts of product compared to the amount of the proteins used.263,264 Different from its Mo-counterpart, the V-nitrogenase can further reduce CO2 to CD4, C2D4, and C2D6 in D2O buffer with substoichiometric amounts of products after 3 h incubation. The product profile of CO2 reduction was further expanded to ≤C4 hydrocarbons in an ATP-independent study of V-nitrogenase with EuII-DTPA as reductant, with all products showing a turnover number (TON) < 1.264,265

5.4. Other C Substrates

As analogs of carbon dioxide, isocyanic acid/cyanate (HNCO/OCN−), thiocyanate (SCN−), and carbon disulfide (CS2) are substrates of wild-type Mo-nitrogenase.252,266 The slow turnover rates for the reduction of these substrates allowed trapping intermediates by rapid freeze-quench. Dependent on pH and isocyanic acid concentration, the EPR spectra of nitrogenase during turnover in the presence of HNCO displayed signals with g-values corresponding to lo-CO and hi-CO complexes indicating the production of CO.266 The initial EPR study of trapped intermediates from thiocyanate and carbon disulfide reduction by nitrogenase revealed a similar S = 1/2 spin state signal (denoted “c”), indicating a sulfur-containing intermediate bound to FeMo-cofactor.266 Further detailed EPR and 13C-ENDOR study267 revealed the presence of three sequentially formed intermediates trapped during CS2 reduction: “a” with g = 2.035, 1.982, 1.973; “b” with g = 2.111, 2.002, 1.956; and a previously observed “c” with g = 2.211, 1.996, 1.978. All three intermediates were suggested to have CS2-derived fragments bound to one or two Fe atoms on FeMo-cofactor. The first formed intermediate “a” might contain an activated CS2 bound to FeMo-cofactor in side-on mode, and the third intermediate “c” was suggested to contain a “C≡S” species terminally bound to the cofactor through C atom.267

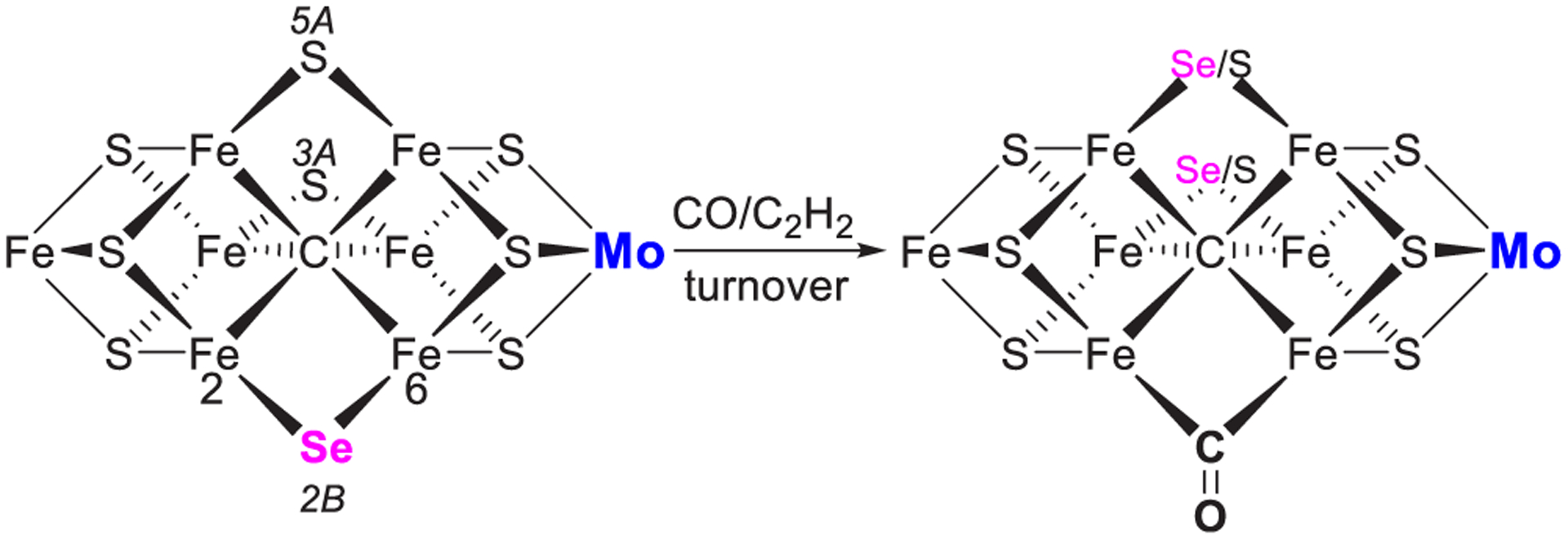

Recently, the potential of selenocyanate (SeCN−) as nitrogenase substrate and inhibitor was evaluated.144 Compared to SCN− and cyanide (CN−), it was found that SeCN− is a poor substrate in terms of methane production. In addition, SeCN− is a potent, yet reversible inhibitor of acetylene reduction by nitrogenase with an inhibition constant (Ki (SeCN−) = 410 ± 30 μM)144 30 times lower than that observed for SCN− (Ki (SCN−) = 12.7 ± 1.2 mM).266 In contrast to full inhibition of acetylene reduction by SeCN−, the proton reduction was inhibited to a lesser extent.144

Rees et al. resolved a MoFe protein crystal structure at 1.6 Å resolution isolated from an assay mixture that included 25 mM SeCN−, revealing a quantitative substitution of the belt sulfide S2B by a selenide ligand.144 A time course series of crystallographic structures demonstrated the migration of the selenide ligand from the original Se2B position to the other two belt sulfide positions (S5A and S3A) during acetylene reduction, as opposed to little or no migration of Se2B during proton reduction. The Se was completely lost and replaced by S after a sufficient number of catalytic turnovers of acetylene. Turning over of the Se-incorporated MoFe protein in the presence of CO and C2H2 resulted in the migration of Se from 2B position to the other two belt positions and high occupancy of bridging CO ligand in the Se2B position (Figure 26).144 The lability of the S2B position toward ligand exchange during substrate reduction confirms the long-proposed Fe2-Fe6 edge as a primary interaction site for substrates and inhibitors.23,33,36,40,59,110,144,156 Application of advanced X-ray absorption spectroscopies to these Se- and CO-substituted FeMo-cofactors revealed a significant asymmetry with regard to the electronic distribution about the cluster, and a redox reorganization mechanism within the cluster has been postulated.268

Figure 26.

Simplified schematic representation of conversion of Se-modified FeMo-cofactor by CO, highlighting the migration of Se2− to S3A and S5A position from the Se2B position.144