Abstract

Quiescent state has been observed in stem cells (SCs), including in adult SCs and in cancer SCs (CSCs). Quiescent status of SCs contributes to SC self-renewal and conduces to averting SC death from harsh external stimuli. In this review, we provide an overview of intrinsic mechanisms and extrinsic factors that regulate adult SC quiescence. The intrinsic mechanisms discussed here include the cell cycle, mitogenic signaling, Notch signaling, epigenetic modification, and metabolism and transcriptional regulation, while the extrinsic factors summarized here include microenvironment cells, extracellular factors, and immune response and inflammation in microenvironment. Quiescent state of CSCs has been known to contribute immensely to therapeutic resistance in multiple cancers. The characteristics and the regulation mechanisms of quiescent CSCs are discussed in detail. Importantly, we also outline the recent advances and controversies in therapeutic strategies targeting CSC quiescence.

Keywords: Stem cell, Cancer stem cell, Quiescence, Targeting quiescence

Core Tip: Quiescent state is very important for both adult stem cells and cancer stem cells. Quiescence of adult stem cells is regulated by multiple intrinsic mechanisms and extrinsic factors. Quiescence of cancer stem cells contributes immensely to therapeutic resistance in multiple cancers. Targeting the quiescence of cancer stem cells may be a novel strategy in clinical practice.

INTRODUCTION

Stem cells (SCs) are present in the embryo and persist throughout the lifetime of a multicellular organism[1]. Embryonic SCs (ESCs) and adult SCs have distinct properties. The former has unlimited potential for cell division but maintains totipotency or pluripotency[1] and can differentiate into various cell types, which is regulated by specific transcription factors at each developmental stage[2]. Adult SCs are smaller cell populations with more limited capacity for self-renewal and differentiation (i.e., are multipotent or oligopotent), and participate in the maintenance of tissue homeostasis and repair[3]. Besides, the growth of tumors is promoted by a few cells, termed cancer SCs (CSCs), which also possess self-renewal ability like the adult normal tissue SCs[4].

SCs mainly exist in a state of proliferation or quiescence[5]. A subset of adult SCs remains in quiescence in the absence of physiologic stimuli, which preserves genomic integrity. The quiescent state (G0) is defined as reversible cell cycle arrest characterized by reduced metabolic activity[5]. And SCs can exit quiescence and re-enter the cell cycle in response to various types of stress or changes in the microenvironment[5]. The phenomenon of quiescence has been found in multiple adult SCs, including hematopoietic SCs (HSCs)[6], muscle SCs (MuSCs)[7], neural SCs (NSCs)[8], and hair follicle SCs (HFSCs)[9].

Like adult SCs, CSCs can switch between the state of proliferation and quiescence, and the quiescence state can explain therapeutic resistance and relapse in cancer[4]. CSCs can remain quiescent in the body for many years[10]; factors such as those present in the circulation can induce their reactivation, leading to tumor relapse[2]. CSC quiescence has been investigated in many malignancies, such as breast cancer, myeloid leukemia, and glioblastoma[11-13].

In this review, we summarize the recent advances in studies of quiescence in adult SCs and CSCs, especially about the intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms that regulate the quiescence of adult SCs and CSCs. The clinical implications and therapeutic targeting of quiescent CSCs are also discussed.

INTRINSIC MECHANISMS REGULATING ADULT SC QUIESCENCE

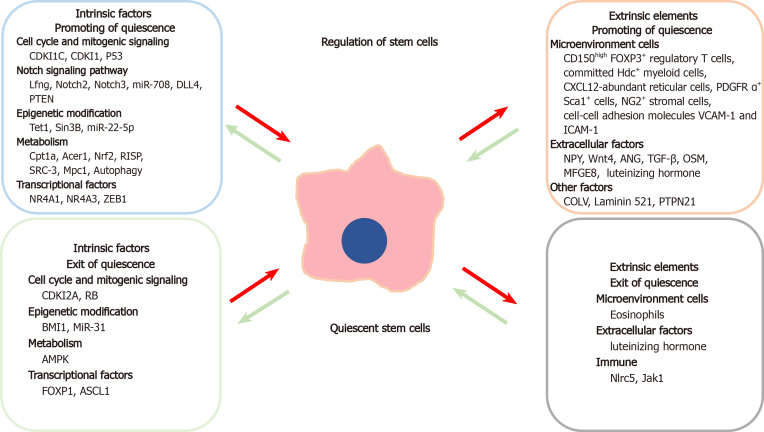

Quiescence in adult SCs is mainly regulated by intrinsic mechanisms such as the cell cycle, intracellular signaling cascades, epigenetic alterations, cellular metabolism, and transcription factors controlling gene expression (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of various factors that lead to promoting or exit of quiescence in stem cells. The intrinsic elements are in the left boxes whereas the extrinsic elements are in the right boxes.

Cell cycle and mitogenic signaling

By definition, quiescence is the reversible G0 phase of the cell cycle. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CDKIs) play an essential role in regulating adult SC quiescence. CDKI1C (P57Kip2, also known as CDKN1C) is highly expressed in human adipose-derived SCs and induces the quiescence of adipose-derived SCs via the downregulation of CDK2-cyclin E1 complex, which can promote the cell to re-enter into G0 regardless of proliferative cues[14]. The CDKI2A gene (CDKN2A) encodes two proteins, p14arf and p16, that inhibit CDK4 and CDK6 and thereby activate retinoblastoma (Rb) protein that can block cell cycle progression[15]. Deletion of CDKN2A results in the loss of function of the C2H2 zinc finger transcription factor BCL11b, which is associated with defects in mammary epithelial cell development and regeneration[16]. Furthermore, BCL11b is highly expressed in the mammary epithelial SC population that is located at the luminal-basal interface, and promotes the SC population to transit from S to G0 state and exit from the cell cycle[16]. CDKI1 (p21Cip1/Waf1) is a universal inhibitor of cyclin/CDK complexes[17]. The expression of p21Cip/waf is increased by depleting the CDK-binding protein CDK5 and ABL1 enzyme substrate 1 (CABLES1), which promotes HSC quiescence in Cables1 −/− mice[6].

The tumor suppressor protein P53 plays a critical role in maintaining genomic integrity. P53 suppresses cell proliferation by blocking cell cycle progression and accelerating cell apoptosis[18]. P53 also has the capacity of regulating SC quiescence. Knockdown of p53 in Rpt3-null muscle satellite cells rescued the cell proliferation deficiency; Rpt3 encodes the 26S protease regulatory subunit 6B, which inhibits P53 to induce cell cycle exit. Furthermore, reduced Rpt3 levels in adult resting muscle cells resulted in defective muscle regeneration and the loss of quiescent satellite cells[7]. P53 promoted the quiescence, and suppressed the self-renewal and proliferation of airway club progenitor cells, by inhibiting the expression of genes encoding cell cycle inhibitors including P21, cyclin G1 (Ccng1), inhibitor of growth protein 3 (Ing3), and erythroid differentiation regulator 1 (Erdr1), and by increasing that of cell cycle-promoting genes such as CDK2, Rad21, Ran, and stathmin (Stmn1)[19]. The posttranslational ubiquitylation and degradation of P53 in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells are regulated by COP9 signalosome subunit 5 (CSN5). Asrij, a member of the ovarian carcinoma immunoreactive antigen domain protein family, interacts with CSN5 to maintain P53 protein levels; loss of Asrij abolished quiescence and stimulated HSC proliferation in bone marrow (BM)[20].

The tumor suppressor Rb, which serves as a gatekeeper for the G1/S transition and blocks cell division, is dysregulated in multiple cancers. The phosphorylation of Rb accelerates cell cycle re-entry mainly through binding and repression of E2F transcription factors[21]. In HSCs, inactivation of Rb induces E2F-mediated transactivation of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3, which impaired thrombopoietin-mediated Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) signaling and finally abolished HSC quiescence[22].

Notch signaling pathway

Notch signaling plays an essential role in adult SC differentiation, proliferation, and survival and tissue maintenance and regeneration[23]. The Notch signaling pathway was found to be involved in NSC quiescence. Lunatic fringe (Lfng), a selectively expressed modulator of Notch receptor in NSCs, mediates the contact between NSCs and their daughter cells, and allows the NSC daughter cells to promote their parent NSCs to enter into quiescent state and to prevent their hyperactivation[23]. Deletion of Notch2 represses cell cycle-related genes, and thus activates quiescent NSCs and stimulates neurogenesis in the ventricular zone/subventricular zone (SVZ)[8]. The DNA-binding protein, inhibitor of differentiation 4 (ID4), is the main effector of Notch2 signaling in NSCs. In the adult dentate gyrus, ID4 was found to function in inhibiting cell cycle, and preserving NSC pool and their quiescence[24]. In the lateral and ventral walls of subependymal zone (SEZ), which is the largest neurogenic niche, Notch3 was found to be highly expressed in quiescent NSCs as compared to active NSCs. Downregulation of Notch3 in the lateral wall of the SEZ can increase NSC division and deplete the quiescent NSC population[25]. Ablation of Notch1 reduced the number of active but not quiescent NSCs, indicating that Notch1 especially promotes active NSC proliferation[26].

Notch signaling negatively regulates the differentiation of skeletal muscle satellite (stem) cells and stimulates the expression of extracellular factors in the SC niche to maintain skeletal muscle satellite (stem) cell quiescence. For example, Notch signaling induced the expression of miR-708 in quiescent skeletal muscle satellite cells, and thereby repressed the transcription of focal adhesion-related protein Tensin3 to inhibit cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation and maintain satellite cells in the quiescent state[27]. Additionally, MuSCs attract capillary endothelial cells (ECs) via vascular endothelial growth factor A, while ECs help to maintain MuSC quiescence through the EC-derived Notch ligand Delta-like 4 (DLL4), which interacts with Notch3 expressed by MuSCs[28,29]. Moreover, inactivation of phosphatase and tensin homolog increased Akt phosphorylation in quiescent muscle satellite cells and induced cytoplasmic translocation of Forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1)—a major substrate of phosphorylated Akt—while repressing Notch signaling, causing muscle satellite cells to exit quiescence and leading to depletion of the SC pool[30,31].

Epigenetic modification

The transition of SCs from a quiescent to a proliferative state is a dynamic and reversible process. Epigenetic mechanisms including DNA methylation, histone modification, microRNAs (miRNAs), as well as long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) play an important role in regulation of quiescence[32,33].

Ten-eleven translocation (Tet) family proteins including Tet1, Tet2, and Tet3 induce DNA demethylation[34]. Tet1 is also known to promote histone methylation[35]; Tet1 deficiency leads to loss of quiescence, which depletes the HSC population and causes HSC exhaustion in Tet1−/− mice, through decreasing histone H3 Lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) and thereby increasing the levels of the cell cycle regulators p19 and p21 in HSCs[35]. Additionally, the polycomb complex protein BMI1 suppressed multiple developmental programs in BM stromal cells (BMSCs). BMI1 depletion enhanced the ability of BMSCs to maintain HSC quiescence through downregulation of repressive epigenetic modifications, including the ubiquitylation of histone H2A and the H3K27me3 of genes such as Ink4a/ADP ribosylation factor and Homeobox genes[36].

The chromatin-associated factor SIN3 transcription regulator family member B (Sin3B) is a noncatalytic scaffold protein that is a core element of histone deacetylase (HDAC) transcriptional repressor complexes and regulates cell cycle exit. Loss of Sin3B undermines HSC quiescence and enhances their sensitivity to myelosuppressive therapy[37].

MiRNAs are small noncoding RNAs that function in RNA silencing and posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression[38]. MiRNAs are also involved in the regulation of quiescent SCs. Loss of the miRNA miR-31, which is involved in the posttranscriptional regulation of interleukin (IL)-34, stimulates asymmetric cell division of active skeletal muscle satellite cells, promotes their re-entry into a quiescence state, and enhances myogenesis[39]. HFSCs cultured with dermal papilla cells (DPCs) tend to differentiate, and the miRNA expression profiling of DPC-derived exosomes showed that miR-22-5p negatively regulates proliferation and promotes quiescence of HFSCs by targeting lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF1)[9].

Metabolism

The metabolic state of adult SCs influences their quiescence through complex mechanisms. Lipid anabolism in neural stem/progenitor cells (NSPCs), i.e., lipid accumulation from de novo lipid synthesis, was found to be critical for NSPC proliferation[40], while lipid catabolism [fatty acid oxidation (FAO)] regulated NSPC quiescence[41]. Proliferative hippocampal NSPCs show reduced carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a (Cpt1a)-dependent FAO, which is increased in quiescent NSPCs. Application of malonyl-CoA, a Cpt1a inhibitor and regulator of FAO, facilitated NSPCs to retreat from quiescence and enhanced NSPC proliferation[41].

Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) is related to the quiescent state in HSCs, and MMP-low HSCs are more quiescent in contrast to MMP-high HSCs that are activated. Single-cell RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) indicated that there are different gene expression patterns of glycolysis and lysosome in HSCs of low and high MMP. Glycolytic gene expression was enriched in the MMP-high HSCs, and MMP-high HSCs took in more glucose and exhibited higher reliance on glycolysis than MMP-low HSCs in vitro; GO terms showed that lysosomal-mediated pathways were distinctly enriched in MMP-low HSCs, and MMP-low HSCs had a lower capacity of lysosomal degradation and a higher mitochondrial turnover relative to MMP-high HSCs[42].

Ceramides and their metabolites, which are regulated by alkaline ceramidase (Acer1), function as bioactive lipids to regulate various biological processes including maintaining the homeostasis of skin epidermis[43,44]. Acer1 deficiency increased the levels of ceramides and their metabolites in the epidermal compartments and broadened the follicular infundibulum, thereby reducing the survival, stemness, and quiescence of HFSCs and leading to progressive hair loss in mice[43].

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) regulates the oxidative stress response and inhibits cell cycle progression; dysregulation of Nrf2 contributes to hyperproliferation in the HSCs and hematopoietic progenitor cells, inducing their exit from quiescence via C-X-C chemokine (CXC) receptor type 4 signaling[45]. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a regulator of cellular metabolism that targets lactate dehydrogenase (LDH); loss of AMPK resulted in a Warburg-like switch to increased glycolysis and quiescence in MuSCs[46].

Mitochondrial metabolism is important for preserving SC quiescence. In adult HSCs, defects in the mitochondrial complex III subunit Rieske iron sulfur protein (RISP) impaired mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and respiration, by decreasing the NAD+/NADH ratio, resulting in a loss of quiescence and hypocytosis[47]. Steroid receptor coactivator (SRC)-3 is highly expressed in HSCs; SRC-3 deficiency enhanced mitochondrial metabolism in HSCs, resulting in excess production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby promoting HSC to re-entry into the cell cycle[48].

HFSCs produce markedly more lactate than other cells during glycolytic metabolism, and inhibition of mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 1 (Mpc1) stimulates lactate production to promote the HFSCs to exit from quiescence and progress into the hair cycle[49].

Autophagy is a normal and controlled process that segregates unnecessary or dysfunctional cellular components into autophagosomes, which are transported to the lysosome for degradation and ultimately used to generate energy and molecules for cellular reconstruction and homeostasis[50]. Compared to younger HSCs, about one-third of aged HSCs in mice show increased autophagy and elimination of metabolic byproducts along with a self-renewal capacity. Defects of autophagy in HSCs result in mitochondria accumulation and enhanced metabolism, which accelerate myeloid differentiation through epigenetic alterations and impair HSC quiescence and regenerative potential. On the other hand, autophagy was also shown to inhibit HSC metabolism by eliminating active, robust mitochondria to maintain the stemness and quiescence of HSCs[51].

Transcriptional regulation of gene expression

Transcriptional regulation is important for SC quiescence. Nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 1 (NR4A1) and NR4A3, which are part of the Nur nuclear receptor family of transcription factors[52], regulate quiescence by directly binding to the enhancer of the gene encoding the hematopoiesis-specific anti-proliferative transcription factor CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein α (Cebpa) and inducing Cebpa transcription activity, and by blocking nuclear factor (NF)-κB-mediated proliferative inflammation responses in the HSCs[53].

Quiescent mammary SCs regulate the development of the ductal epithelium. Deletion of the transcription factor FOXP1 was shown to impair ductal morphogenesis and induce a rudimentary tree in mouse mammary gland, leading to enrichment of quiescent Tetraspanin (Tspan)8hi mammary SCs. FOXP1 is a direct repressor of Tspan8 in basal cells, and defects of Tspan8 can rescue ductal morphogenesis failure that arising from the loss of Foxp1[54].

The transcription factor zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) is upregulated in regenerating myofibers of injured muscles[55]. ZEB1 maintains MuSC quiescence and prevents their premature activation following injury and facilitates regeneration, by inhibiting myogenic differentiation 1, the transcriptional activator of FOXO3, and upregulating Notch target genes, Hairy and enhancer-of-split (Hes), and Hes-related with YRPW motif families[31,55,56].

Achaete-scute family basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor 1 (ASCL1) expression is upregulated in NSCs of the adult hippocampus, in response to the activation signals from surrounding niche. ASCL1 directly regulates the expression of cell cycle-associated genes to enhance the proliferation of hippocampal SCs in subventricular zone. Deactivation of ASCL1 hindered the quiescence exit in NSCs by rendering them insensitive to external stimuli[57]. Moreover, loss of the gene encoding E3-ubiquitin ligase HECT, UBA, and WWE domain-containing 1 (Huwe1) increased the expression of ASCL1, preventing the accumulation of cyclin D and promoting the hippocampal SCs to return to the quiescence state[58].

All the above findings highlight the contribution of cell-intrinsic mechanisms in the regulation of adult SC quiescence, including the cell cycle, intracellular signaling cascades, epigenetic mechanisms, cellular metabolism, and transcription factors controlling gene expression.

EXTRINSIC FACTORS REGULATING ADULT SC QUIESCENCE

SC quiescence is regulated not only by intrinsic molecular mechanisms but also by extrinsic factors in their surrounding microenvironment which is called ‘niche’[59]; particularly by the interactions between SCs and the growth factors, cytokines, adhesion molecules, extracellular matrix components, and metabolites released from niche cells (Figure 1)[59-62]. The adult SC niche can preserve the quiescence of adult SCs, while in response to tissue damage or other stimuli, extracellular signals can also induce SC self-renewal or differentiation for tissue repair.

Microenvironment cells

The balance among the adult SC state of quiescence, proliferation, differentiation, and self-renewal can also be regulated through their interactions with nearby cells in the microenvironment, such as eosinophils, mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), ECs, macrophages, leukocytes, and immune cells[63-66]. In addition, cell-cell adhesion molecules such as vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1, cadherin, and intercellular CAM-1 (ICAM-1) also play important roles in promoting activation of or maintaining quiescence in adult SCs[67-69].

Eosinophils are multifunctional leukocytes responsible for initiation, enhancement, and control of the inflammatory and immune responses, especially in allergic diseases[70]. Eosinophils were shown to disrupt hematopoietic SC homeostasis and quiescence via ROS accumulation, which is induced by secretion of chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 6[66].

Regulatory immune cells influence HSC self-renewal and homeostasis. CD150high FOXP3+ regulatory T cells located in the HSC niche of BM generate adenosine through the cell surface ectoenzyme CD39, which protects HSCs from oxidative stress and maintains HSC quiescence[63]. The increase in the number of HSCs in CD73 knockout mice can be blocked by treatment with an antioxidant or adenosine receptor agonist, indicating that CD73, a surface enzyme that converts AMP to adenosine, contributes to the maintenance of HSC quiescence by preventing oxidative stress via adenosine receptor 2A in CD150high FOXP3+ regulatory T cells[71]. In addition, lineage-committed Hdc+ myeloid cells that adjoin myeloid-biased hematopoietic SCs (MB-HSCs) produce histamine, activating the H2 receptor on the MB-HSCs to regulate their quiescence and self-renewal. Accordingly, dysregulation of histamine feedback results in a failure of MB-HSCs to re-enter quiescence, leading to the depletion of these cells[72].

MSCs including C-X-C chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12)-abundant reticular cells and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor α+ Sca1+ cells interact with HSCs and regulate hematopoietic homeostasis. These cells express the transcription factor early B-cell factor 1 (EBF1). Conditional knockdown of Ebf1 in MSCs altered gene expression, e.g., downregulation of adhesion-related genes, resulting in impaired HSC quiescence and reduction of myeloid output[64]. Stromal cells expressing nerve/glial antigen 2 (NG2) constitute special niches for arterioles and sinusoids in BM. Cxcl12 knockdown in arteriolar NG2+ cells was shown to induce HSCs to exit from quiescence, result in HSC exhaustion, and alter HSC localization in BM[73].

VCAM-1 is enriched in type B NSCs in adult mouse[67]. VCAM-1 signals stimulate ROS production to maintain NSC quiescence via NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2). High ROS levels were shown to sustain NSC self-renewal and prevent the depletion of the NSC pool[67]. In addition, conditional deletion of N- and M-cadherin, which mediate adhesion between MuSCs and their myofiber niche, impaired MuSC quiescence and preserved the pool of regeneration-proficient MuSCs[68]. ICAM-1, which is highly expressed in niche stroma cells such as endothelial cells, maintains quiescence and self-renew capacity of HSCs. ICAM-1 deficiency in the BM niche alters the expression profile of stroma cell factors, resulting in HSC expansion and impairing quiescence in ICAM-1-deficient mice[69].

Extracellular factors

Soluble factors secreted by neighboring cells or distant tissues can influence adult SC function and fate. Some well-known factors that regulate adult SCs include the neurotransmitter neuropeptide Y (NPY), Wnt4, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, and oncostatin M (OSM)[74-78].

NPY receptor isoforms (except Y3) are enriched in most HSCs[79]. Sympathetic nerves secrete NPY in BM, directly inhibiting HSC proliferation by facilitating HSC to enter into G0 phase and increasing the expression of genes such as Foxo3 that regulate quiescence[74].

Muscle fiber-derived Wnt4 maintains MuSC quiescence by activating RhoA in a mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1)-independent manner. In contrast, deletion of Wnt4 promoted MuSC activation and muscle generation[75].

The ribonuclease angiogenin (ANG) secreted in the niche alters the functional state of HSCs by reducing their proliferative capacity and promoting their quiescence, thus protecting the cells from radiation-induced BM damage[77].

TGF-β plays a key role in the regulation of HSC quiescence[80,81]. TGF-β was found to suppress cytokine-mediated lipid raft clustering, which is essential for HSCs to increase cytokine signaling to a level that is sufficient for cell cycle re-entry, and induce HSC quiescence ex vivo[80]. Src homology 2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 1 (SHP-1) interacts with the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitor motif of TGF-β receptor 1 to modulate TGF-β signaling. Dysregulation of SHP-1 in HSCs resulted in insensitivity to TGF-β-mediated regulation of HSC quiescence, induced HSCs to leave the quiescent state, and suppressed their self-renewal capacity. Megakaryocytes engulf SHP-1–activated HSCs and regulate their quiescence by producing TGF-β1 in the BM niche[78]. Additionally, TGF-β1 slows cell cycle progression in HSCs, promotes their return to quiescence, and limits their potential for self-renewal in vitro[82].

OSM is a member of IL-6 family that is secreted by muscle fibers and induces MuSCs’ entry into G0. Deletion of the OSM receptor caused MuSC exhaustion and decreased their regenerative potential[76]. OSM secreted by a subset of TREM2+ macrophages in the hair follicle niche negatively regulated hair growth by maintaining HFSC quiescence via JAK–signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) signaling[83].

Radial glia-like neural SCs (RGLs) in the dentate gyrus generate adult nerves throughout the lifetime of mammals[84]. Milk fat globule epidermal growth factor 8 (MFGE8), which is involved in phagocytosis, is highly expressed in quiescent RGLs[85]. Knockout of Mfge8 in mice decreased neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus, and Mfge8-deficient RGLs showed hyperactivation and exhaustion of NSCs via mTOR1 signaling[86].

Sex hormones regulate HSC proliferation and self-renewal[87,88]. Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone antagonist, a sex steroid inhibitor, suppressed luteinizing hormone levels to promote HSC’s entry into G0 and prevent their exhaustion after total-body irradiation at a lethal radiation dose[89].

Immune response and inflammation in the microenvironment

Adult SCs are long-lived and their continuous self-renewal leads to the acquisition of mutations and generation of neoantigens[90]. The neoantigens make these adult SCs to be the potential targets of immune surveillance. Immune evasion is an inherent characteristic of quiescent SCs and is achieved through downregulation of the antigen presentation mechanism mediated by the trans-activator NOD-like receptor family CARD domain-containing (Nlrc)5. Circulating adult SCs such as intestinal, ovarian, and mammary SCs are eliminated by activated T cells, while quiescent MuSCs and HFSCs that express low levels of Nlrc5 are resistant to T cell-mediated killing[91]. Proinflammatory cytokines and immune factors play critical roles in SC quiescence, while an abnormal immune response links to immunologic and neoplastic diseases[92,93]. Conditional Jak1 knockdown in HSCs diminished their potential for lymphoid/myeloid differentiation, induced quiescence, and reduced sensitivity to hematopoietic stress and immune factors such as type I interferons and IL-3[94].

Other factors in the microenvironment

Adult muscle satellite cell-derived collagen V (COLV) is a key component of the SC niche; knockdown of the Col5a1 caused aberrant cell cycle re-entry, exit from quiescence, and depletion of the SC pool[95].

Laminin 521 coating improved cell adhesion, increased the expression of quiescence-associated genes such as glial fibrillary acidic protein, and preserved quiescence in cultured rat hepatic stellate cells[96]. Thus, laminin 521 is a critical element in the space of Dissé where hepatic stellate cells (mesenchymal SCs) exist in a quiescent state.

Protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 21 (PTPN21) is highly expressed in HSCs. Inhibiting PTPN21 reduced quiescence, enhanced mobility, impaired self-renewal capacity of HSCs, and induced their egress from the niche[97].

Adult SCs are influenced by adjacent cells and extracellular factors in the microenvironment. Signals and nearby cells in the niche stimulate the expression or activity of quiescence-associated molecules and regulate the switch between quiescence and proliferation.

QUIESCENCE OF CSCS AND THEIR CLINICAL RELEVANCE

Definition of quiescent CSCs

CSCs have been detected in most malignancies and are implicated in tumorigenesis, metastasis, and posttreatment relapse[98,99]. Like normal adult SCs, CSCs are characterized by stemness, self-renewal capacity, and differentiation potential. CSCs also can switch between proliferative and quiescent states in response to external signals and stress[3,99].

CSCs tend to remain in a quiescent state (i.e., reversible G0 phase) to survive under conditions of environmental stress over a long period time[100]. The fraction of quiescent CSCs in a neoplasm is difficult to estimate and depends on the type of cancer. CSCs were reported to account for < 1% to > 80% (glioblastomas) of all tumor cells in solid tumors[101-103]. Quiescent CSCs constitute an even smaller proportion, which was estimated as 5% of total breast CSCs[11].

Quiescent CSCs are difficult to be distinguished from other CSCs owing to the lack of specific surface markers and universal genotypic and phenotypic features[104]; however, quiescent CSCs still have some specific characteristics, including label retention, low RNA content, and absence of proliferative marker expression[11,105,106].

CSCs can remain quiescent for decades before metastasizing and causing relapse in cancer patients[107]. Quiescent CSCs are thought to be the main cause of cancer treatment failure because of their resistance to harsh environmental conditions, insensitivity to therapeutics, and ability to evade immune surveillance[108-110]. For instance, quiescent breast CSCs can exist in the blood as circulating tumor cells or remain in premetastatic organs as disseminated tumor cells, contributing to late relapse after radical mastectomy[111,112]. Thus, clarifying the biological properties of quiescent CSCs is essential for developing novel anticancer treatments and preventing metastasis and relapse.

Regulations of quiescent CSCs

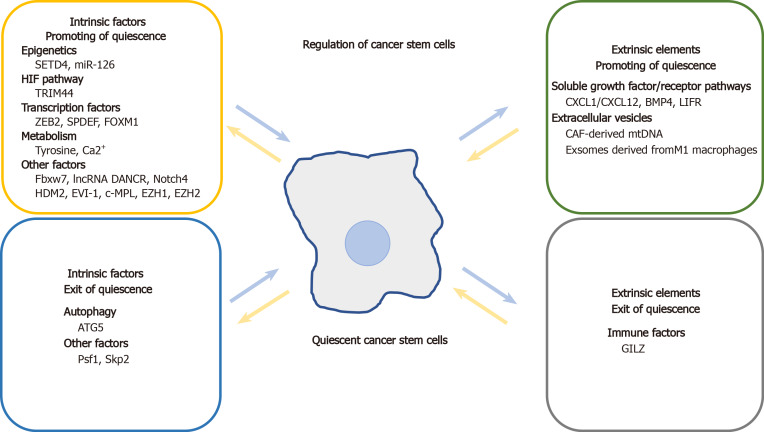

Common molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways similarly regulate quiescence in both adult SCs and CSCs. Signaling molecules and microenvironmental factors that regulate CSC quiescence include tumor suppressors, CDKs, Notch signaling pathway components, regulators of metabolism, epigenetic modifications, niche-secreted factors, and immune cells (Table 1, Figure 2).

Table 1.

Regulation of quiescent stem cells

|

Stem cells

|

Regulatory factors

|

| Adipose-derived stem cells | CDKI1C[14] |

| Airway club progenitor cells | P53[19] |

| Hepatic stellate cells | Laminin 521[96] |

| Hair follicle stem cells | MiR-22-5p[9], Acer1[43,44], Mpc1[49], OSM[83], Nlrc5[91] |

| Hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells | CDKI1[6], Asri[20], RB[22], Tet1[35], BMI1[36], SIN3[37], MMP[42], NRF2[45], RISP[47], SRC-3[48], Autophagy[51], NR4A1 and NR4A3[53], CD150high FOXP3+ regulatory T cells[63,71], Ebf1[64], Eosinophils[66], ICAM-1[69], lineage-committed Hdc+ myeloid cells[72], NG2+ cells[73], NPY[74], ANG[77], SHP-1[78], TGF-β[80], luteinizing hormone[89], Jak1[84], PTPN21[97] |

| Mammary stem cells | BCL11b[16], FOXP1 |

| Muscle satellite (stem) cells | Rpt3[7], miR-708[27], Notch3[28,29], PTEN[30,31], ZEB1[31,55,56], miR-31[39], AMPK[46], N-cadherin and M-cadherin[68], Wnt4[75], OSM[76], Nlrc5[91], Col5a1[95] |

| Neural stem/progenitor cells | Notch2[8], Lfng[23], ID4[24], Notch3[25], Cpt1a[41], ASCL1[57], Huwe1[58], VCAM-1[67], MFGE8[86] |

Figure 2.

Schematic presentation of main factors that regulate quiescent cancer stem cells in intrinsic and extrinsic aspects.

Autophagy accelerates cancer progression by allowing tumor cells to respond to intracellular and environmental insults and protects them from programmed cell death[113,114]. Ovarian cancer spheroid cells, which acquire SC characteristics, exhibit high levels of autophagy. Knockdown of autophagy-related 5 (ATG5) suppressed autophagy and arrested ovarian cancer spheroid cells in G0/G1. Conversely, exposure to the autophagy inducer rapamycin impaired self-renewal and quiescence in these cells[115].

Tumors have a highly varied epigenetic landscape that includes DNA methylation and histone modification[116]. Epigenetic modifications play an important role in regulating CSC quiescence. SET domain–containing protein 4 (SETD4) was shown to regulate breast CSC quiescence by facilitating the formation of heterochromatin via trimethylation of histone H4 lysine 20. Quiescent breast CSCs with the expression of SETD4 are chemoradiotherapy-resistant, have high tumorigenic potential, and remain in a state of quiescence through asymmetric division. Cancer cells expressing SETD4, which are derived from clinical samples (cervical, liver, ovarian, gastric, and lung cancers), show elevated levels of CSC markers and resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy[11]. ECs express miR-126, which promotes quiescence and chemotherapy resistance in BM leukemia SCs in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)[12]. In mouse CML models, miR-126 blocked cell cycle by targeting the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway[12,117].

The hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway is a major regulator of quiescence and a promising therapeutic target in leukemia and solid tumors[118,119]. Using the fluorescent tracer PKH26, quiescent stem-like cancer cells were identified in multiple myeloma (MM). Those quiescent stem-like cancer cells were present in the osteoblast niche of BM and expressed high levels of tripartite motif containing 44 (TRIM44)[119], an E3 ubiquitin ligase that deubiquitinates and stabilizes the expression of HIF-1α under normoxia and hypoxia. TRIM44 overexpression was in turn shown to stabilize the expression of HIF-1α, which contributed to SC survival and cell quiescence in MM[120].

Transcription factors, including zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 2 (ZEB2), SAM pointed domain-containing ETS transcription factor (SPDEF), and FOXM1, are involved in CSC quiescence. ZEB2, which is related to stemness and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), was reported to be highly expressed in quiescent/slow-cycling SCs isolated from colorectal cancer (CRC) by PKH26 labeling. The CSCs showed chemotherapy resistance and slow growth in vivo and in vitro. Accordingly, exogenous expression of ZEB2 in colorectal CSCs increased the G0/G1 cell fraction. High ZEB2 levels were also correlated with worse relapse-free survival in CRC patients[121]. Conditional expression of SPDEF inhibited intestinal tumorigenesis in leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptor 5 (LGR5)-positive intestinal SCs in transgenic mice expressing an oncogenic form of β-catenin[122]. SPDEF inhibits proliferation of tumor cells and induces them to stay in a quiescent state, by obstructing the binding of β-catenin to DNA-binding T cell factor 1 (TCF1) and TCF3, thereby modulating the expression of cell cycle-associated genes such as Ccnd1, Hdac4, Cdk6, Myc, and Axin2[122]. Additionally, in mixed lineage leukemia-rearranged acute myeloid leukemia (AML), upregulation of FOXM1, a regulator of the cell cycle, preserved LSC quiescence by preventing the polyubiquitination degradation of β-catenin, thereby activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling[123].

Metabolic reprogramming including tyrosine metabolism and Ca2+ homeostasis plays a key role in CSC biology[124,125]. Dysregulation of metabolic pathways in CSCs can lead to tumor recurrence and treatment resistance. Quiescent CD13+ hepatic CSCs mainly rely on aerobic metabolism of tyrosine rather than glucose for energy. Targeting tyrosine metabolism with nitisinone depleted the population of CD13+ hepatic CSCs, impaired quiescence, and delayed tumor recurrence by accelerating the degradation of FOXD3[125]. Moreover, inhibition of store-operated channels alters Ca2+ homeostasis; this increases Ca2+ sequestration by mitochondria in glioblastoma stem-like cells (GSLCs) and induces their return to quiescence[13]. Reducing extracellular pH can also promote the maintenance of a quiescent state in GSLCs[13].

Several immune factors have been shown to act on quiescent CSCs. Melanoma stem-like cells express low levels of glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ), which mediates the anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids[126]. In an in vivo model, GILZ deficiency arrested melanoma cells in G0 even after vaccination with irradiated murine melanoma cells[127].

Soluble growth factor/receptor pathways such as CXCL1/CXCL12, bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4), and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) modulate quiescence in activated CSCs. CXCL1 in mice—a homolog of human IL-8—induced quiescence and chemotherapy resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) SCs via activation of mTORC1 kinase[128]. Cxcl12 knockout in MSCs can decrease HSC numbers, and promote LSC to exit from quiescent state through downregulation of quiescence related genes such as TGF-β and STAT3[129]. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment induced a subpopulation of BMP receptor 1B+ (BMPR1B+) cells adhering to stromal cells to enter quiescence[130]. Quiescent LSCs do not produce BMP4 but rely on BMP4 that is produced by stromal cells within their niche. BMP4 was shown to directly regulate the quiescence of CML LSCs via the JAK/STAT3 pathway, which is dependent on BMPR1B kinase activity. Targeting both BMPR1B and JAK2/STAT3 depleted quiescent LSCs in the BM niche[130]. Breast cancer cells may enter a quiescent state before establishing bone metastasis through LIF. Breast cancer patients with bone metastases express lower levels of LIF receptor (LIFR), which is associated with poor prognosis[131]. Furthermore, loss of LIFR in quiescent breast cancer cells decreased the expression of quiescent CSC-associated genes such as Tgfβ2 and Notch1, while knocking down Lifr in vivo enhanced bone destruction and tumor cell proliferation[131].

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from tumor and niche cells regulate tumor progression and therapeutic resistance by transferring their contents (proteins, lipids, mRNAs, and miRNAs) to recipient cells[132]. There is accumulating evidence that EVs are involved in the regulation of CSC quiescence. EVs extracted from xenograft models or cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) from hormone therapy-resistant breast cancer patients contains mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which promotes estrogen receptor-independent oxidative phosphorylation and hormone therapy resistance. These EVs facilitate exit from quiescence in hormone therapy-naive breast cancer stem-like cells or hormone therapy-treated quiescent populations[133]. Additionally, BM macrophages with an M1 phenotype reversed breast CSC quiescence by secreting exosomes that activated NF-кB signaling. In contrast, macrophages with an M2 phenotype promoted quiescence as well as reduced proliferation and carboplatin resistance in breast CSCs through gap junction-mediated intercellular communication[134].

The perinecrotic niche harbors quiescent CSCs with high tumorigenic potential in glioblastoma. These CSCs express low levels of GINS components including SLD5, PSF1, PSF2, and PSF3. Psf1 deficiency was shown to suppress reactivation of quiescent CSCs after serum supplementation or reoxygenation[135].

Chemotherapeutic drugs including 5-fluorouracil target CSCs in lung cells by increasing F-box and WD repeat domain-containing (Fbxw) 7 and by decreasing S phase kinase associated protein (Skp) 2 expression, thereby downregulating c-Myc and upregulating CDKI 1B (p27), which pushes cells into quiescence[136].

The lncRNA DANCR is upregulated in AML LSCs. Knockdown of DANCR transcript reduced self-renewal capacity and quiescence of LSCs in a AML murine model[137]. The lncRNA growth arrest-specific 5 was highly expressed in the CD133+ pancreatic CSC population and was found to suppress proliferation by inhibiting glucocorticoid receptor-mediated cell cycle regulation[138].

NOTCH4 receptor is highly expressed in triple-negative breast cancer progression and is associated with breast CSC regulation. NOTCH4 upregulates SLUG to promote EMT and activates transcription of GAS1, a regulator of cell cycle arrest, to sustain quiescence of breast CSCs. It was also demonstrated that, compared to the well-known cell surface marker CD44+CD24−, NOTCH4 expression level can better identify mesenchymal-like breast CSCs[139].

Therapeutic strategies targeting CSC quiescence

A potential treatment for relapse is using agents that target quiescence-related markers and signaling pathways such as human double minute 2 (HDM2), ecotropic viral integration site-1 (EVI-1), chronic myeloproliferative leukemia (c-MPL), enhancer of zeste 1 (EZH1) and EZH2, and autophagy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Regulation of quiescent cancer stem cells

|

Type of cancer

|

Regulatory factor

|

Regulatory mechanism

|

| Ovarian cancer | Autophagy | Knockdown of ATG5 inhibits autophagy and arrests ovarian cancer cells in G0/G1 state through upregulating production of ROS[115] |

| Breast cancer | SETD4 | SETD4 regulates breast CSC quiescence by facilitating the formation of heterochromatin via H4K20me3 catalysis[11] |

| Breast cancer | LIFR | Loss of LIFR in dormant breast cancer cells reduces the expression of quiescence and cancer stem cell-associated genes, such as TGF-β2 and Notch1[131] |

| Breast cancer | Mitochondrial DNA | CAF-derived EVs, containing mitochondrial DNA, promote estrogen receptor-independent oxidative phosphorylation and facilitate an exit from quiescence in HT-naive breast cancer stem-like cells[133] |

| Breast cancer | Macrophages | Macrophages with an M1 phenotype secrete exosomes to activate NF-кB pathways, and thus reversebreast CSCs (BCSCs) quiescence; macrophages exhibiting an M2 phenotype causes quiescence and lessened proliferation via gap junctional intercellular communication[134] |

| Breast cancer | NOTCH4 | NOTCH4 transcriptionally activates GAS1 to sustain quiescence in BCSCs[139] |

| Colorectal cancer | ZEB2 | ZEB2 upregulates cell cycle-related factors including HDAC9, Cyclin A1, Cyclin D1, HDAC5, and TGFβ2 to keep stem cells quiescent[121] |

| Colorectal cancer | SPDEF | SPDEF breaks binding of β-catenin to TCF1 and TCF3, and regulates cell cycle-associated genes, such as CCND1, HDAC4, CDK6, MYC, and AXIN2, to induce a quiescent state[122] |

| Liver cancer | Tyrosine metabolism | Targeting tyrosine metabolism impairs quiescence by accelerating degradation of Forkhead box D3[125] |

| Liver cancer | CXCL1 | CXCL1 induces quiescence in hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells by activation of the mTORC1 kinase[128] |

| Multiple myeloma | TRIM44 | TRIM44 deubiquitinates HIF-1α to stabilize HIF-1α expression and HIF-1α contributes to MM stem cell quiescence[120] |

| Glioblastoma | Ca2+ | Inhibition of store-operated channels increases capacity of mitochondria to capture Ca2+ in GSLCs, and thus impels proliferous GSLCs to turn to quiescence[9] |

| Glioblastoma | PSF1 | Defect of PSF1 suppresses reactivation of quiescent CSCs after serum supplement or reoxygenation[135] |

| Melanoma | GILZ | Deficiency of GILZ expression in vivo arrests these cells in the G0 phase, and induces quiescence[127] |

| Pancreatic cancer | lncRNA GAS5 | GAS5 restrains the cell cycle to suppress proliferation by inhibiting glucocorticoid receptors (GR) mediated cell cycle regulation[138] |

| Lung cancer | Fbxw7, Skp2 | Knockdown of Fbxw7 upregulated c-myc and knockdown of Skp2 increased the expression of p27, and then transforms cells into quiescence[136] |

| AML | FOXM1 | FOXM1 binds to β-catenin and decreases degradation of β-catenin protein, and thus activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways, and preserves leukemia stem cell (LSC) quiescence[123] |

| AML | lncRNA DANCR | Knockdown of DANCR in LSCs causes reduced stem-cell renewal and quiescence[137] |

| AML | EVI-1 | Evi-1 depression promotes the quiescence of LSCs possibly through Notch4[141] |

| AML | PRC2 | PRC2 regulates suppression of Cyclin D to maintain quiescence in LSCs[145] |

| CML | Mir-126 | Endothelial cells provide miR-126 for CML LSCs to restrain cell cycle progression through targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway[8,117] |

| CML | CXCL12 | Knockout of CXCL12 in mesenchymal stromal cells promotes leukemic stem cell (LSC) expansion via downregulation of genes associated with quiescence such as TGF-β and STAT3[129] |

| CML | BMP4 | BMP4 directly regulates quiescence of CML LSCs through regulating JAK/Stat3 pathway, dependent upon BMPR1B kinase activity[130] |

AML: Acute myeloid leukemia; CML: Chronic myelogenous leukemia; LSC: Leukemia stem cell; CSC: Cancer stem cells.

The E3 ligase HDM2 can regulate p53 activity and is expressed on the membrane of AML blasts including LSCs but not by normal HSCs. Higher membrane (m) HDM2 level in AML blasts is directly proportional to leukemia-initiating potential, cellular quiescence, and chemoresistance. A recent study showed that the synthetic peptide PNC-27 had the capacity to bind to and promote the interaction of mHDM2 with E-cadherin on the membrane of AML blasts, leading to E-cadherin ubiquitination and degradation, thereby inducing the membrane injury and necrobiosis. In both human and murine AML models, PNC-27 treatment eliminated both AML “bulk” blasts and LSCs, but had little impact on HSCs[140].

A subtype of AML, which is characterized by high expression of EVI-1, has very poor outcome, and shows sensitivity to all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA)[141]. EVI-1 suppresses the maturation of leukemic cells and promotes LSC quiescence in vivo. ATRA enhances these effects in an EVI-1–dependent process. Pan-retinoic acid receptor antagonists play an opposite role to that of ATRA, delaying leukemogenesis and reducing LSC quiescence in EVI-1high AML LSCs[142].

A c-MPL+ population of LSCs exists in a quiescent state but is highly tumorigenic and chemotherapy-resistant. The ratio of c-MPL+ cells to CD34+ leukemia cells relates to poor prognosis in AML patients[143]. AMM2, a synthetic inhibitor of c-MPL, stimulated quiescent LSCs to re-enter the cell cycle and enhanced the survival of AE9a leukemia mice when used in combination with chemotherapy drugs[143].

Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) trimethylates histone H3 lysine 27 to maintain LSC stemness[144]. PRC2 suppression of cyclin D preserves LSCs in a quiescent state, which was associated with LSCs’ sensitivity to chemotherapy in AML patients[145]. Additionally, quiescent LSCs in AML have elevated levels of the PRC2 catalytic subunits EZH1 and EZH2. In a mouse AML model, Ezh1/2 knockout was shown to promote cell cycle progression and differentiation of quiescent LSCs, resulting in LSC depletion. In AML mouse models and patient-derived xenograft models, a novel EZH1/2 inhibitor has been developed to eliminate LSCs and impair leukemia progression, demonstrating its therapeutic potential for improving AML patient survival[145].

Autophagy can induce tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) resistance in LSCs and decrease survival in CML patients[146]. However, hydroxychloroquine—the only clinically permissible autophagy inhibitor—did not consistently improve the overall survival of glioma patients because of its high toxicity[147]. PIK-III-a selective inhibitor of vacuolar protein sorting 34 and the lysosomotropic agent Lys05 are two new autophagy inhibitors that drive LSCs out of quiescence and promote myeloid cell amplification. Moreover, combined TKI and Lys05 or PIK-III treatment reduced the size of primary CML and xenografted LSC populations, suggesting that it is an effective treatment for CML patients with persistent LSCs[146].

CONCLUSION

Quiescence of SCs including adult normal SCs and CSCs has been a topic of intense research in recent years. This review highlights the following aspects of quiescent adult SCs and CSCs: (1) Under normal conditions, quiescence protects normal adult SCs from exhaustion and senescence, thus preserving their multipotency, regenerative potential, and ability to maintain tissue homeostasis. The identification of factors that regulate quiescence in normal adult SCs can also facilitate the study of CSC behavior; (2) Elucidating microenvironmental factors that induce or maintain quiescence in SCs is critical for exploiting their clinical potential; (3) In malignant disease, quiescent CSCs exhibit resistance to conventional treatments and are responsible for relapse; and (4) Significant progress has been made in our understanding of molecular mechanisms governing quiescence in CSCs, thus expanding the scope of potential strategies for the treatment of specific types of cancer.

The therapeutic targeting of quiescent CSCs is an emerging concept. More basic and clinical research is required before widespread clinical application is possible. Several drugs that target molecules or signaling pathways in CSC quiescence have been evaluated for their efficacy in vivo or in vitro. However, more agents targeting different classes of molecules or pathways are needed, and their development is hindered by the absence of appropriate markers for CSCs and small CSC population size.

Drugs targeting quiescent CSCs should be designed based on specific markers expressed in these cells or should act on molecules controlling the switch between quiescence and proliferation. The following considerations apply to the development of any new drugs: (1) Validated markers can be used to target quiescent CSCs, especially those that are expressed on the cell surface. However, if the marker is universally expressed by adult SCs, there is a risk of accidental injury to normal cells. Thus, candidate markers are those that are highly expressed in target cells but have low or no expression in normal tissue SCs; (2) Awakening quiescent CSCs allows them to re-enter the cell cycle, increases their sensitivity to conventional therapies, and enables their extermination. However, a risk associated with CSC reactivation is that it could facilitate cancer progression by inducing a proliferative state. Therefore, drugs in this category should be used in combination with or after standard anticancer regimens, and may be more effective when tumors are better controlled; (3) Adjuvant drugs to protect normal SCs must be developed alongside the CSC-targeted therapies, to mitigate any potential damage to normal tissue SCs; and (4) A therapeutic approach that maintains CSCs in a state of quiescence for a long period of time is inherently less risky than CSC reactivation. However, quiescent CSCs may acquire mutations and become resistant to these drugs during treatment. One way to avoid this problem is to use these drugs alongside standard treatments in cases of tumor relapse. Quiescent CSCs are promising targets that need to be taken into consideration in the development of novel anticancer drugs. Nonetheless, therapeutic strategies that can harness CSCs by exploiting the unique characteristics of CSCs have the potential to reduce recurrence and improve outcomes in cancer treatment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Therapeutic strategies against quiescence

|

Type of cancer

|

Therapeutic target

|

Potential therapy

|

Therapeutic mechanism

|

| AML | HDM2 | PNC-27 | PNC-27 binds to mHDM2, leads to E-cadherin degradation, and causes membrane injury and cell necrobiosis[140] |

| AML | EVI-1 | ATRA | ATRA enhances EVI-1-dependent depression of the maturation and promotes the quiescence[141,142] |

| AML | c-MPL | AMML2 | AMML2 blocks c-MPL, stimulates entry of quiescent LSCs into the cell cycle, and increases the sensitivity of LSCs to chemotherapy[143] |

| AML | EZH1, EZH2 | OR-S1, OR-S2 | OR-S1 and OR-S2 inhibit EZH1/2, inactivate PRC2, and then eliminate quiescent LSCs, induce cell differentiation, and turn chemotherapy-resistant LSCs into a chemotherapy-sensitive population[145] |

| CML | Autophagy | Lys05, PIK-III | Lys05 achieves autophagy inhibition in LSCs and promotes differentiation; Lys05 and PIK-III inhibit TKI-induced autophagy and increase the sensitivity of LSCs to TKI[146] |

AML: Acute myeloid leukemia; CML: Chronic myelogenous leukemia; LSC: Leukemia stem cell.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors have nothing to disclose.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: July 10, 2020

First decision: July 30, 2020

Article in press: September 22, 2020

Specialty type: Cell and tissue engineering

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Li SC, Yang WJ S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li JH

Contributor Information

Meng Luo, Department of Breast Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China; Cancer Institute, Key Laboratory of Cancer Prevention and Intervention, China National Ministry of Education, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Jin-Fan Li, Department of Pathology, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Qi Yang, Department of Pathology, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Kun Zhang, Department of Breast Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Zhan-Wei Wang, Department of Breast Surgery, Huzhou Central Hospital, Affiliated Central Hospital Huzhou University, Huzhou 313003, Zhejiang Province, China.

Shu Zheng, Cancer Institute, Key Laboratory of Cancer Prevention and Intervention, China National Ministry of Education, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Jiao-Jiao Zhou, Department of Breast Surgery, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China; Cancer Institute, Key Laboratory of Cancer Prevention and Intervention, China National Ministry of Education, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China. zhoujj@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.García-Prat L, Sousa-Victor P, Muñoz-Cánoves P. Proteostatic and Metabolic Control of Stemness. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:593–608. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vira D, Basak SK, Veena MS, Wang MB, Batra RK, Srivatsan ES. Cancer stem cells, microRNAs, and therapeutic strategies including natural products. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2012;31:733–751. doi: 10.1007/s10555-012-9382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clevers H. The cancer stem cell: premises, promises and challenges. Nat Med. 2011;17:313–319. doi: 10.1038/nm.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung TH, Rando TA. Molecular regulation of stem cell quiescence. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:329–340. doi: 10.1038/nrm3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He L, Beghi F, Baral V, Dépond M, Zhang Y, Joulin V, Rueda BR, Gonin P, Foudi A, Wittner M, Louache F. CABLES1 Deficiency Impairs Quiescence and Stress Responses of Hematopoietic Stem Cells in Intrinsic and Extrinsic Manners. Stem Cell Reports. 2019;13:274–290. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitajima Y, Suzuki N, Nunomiya A, Osana S, Yoshioka K, Tashiro Y, Takahashi R, Ono Y, Aoki M, Nagatomi R. The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System Is Indispensable for the Maintenance of Muscle Stem Cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2018;11:1523–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engler A, Rolando C, Giachino C, Saotome I, Erni A, Brien C, Zhang R, Zimber-Strobl U, Radtke F, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Louvi A, Taylor V. Notch2 Signaling Maintains NSC Quiescence in the Murine Ventricular-Subventricular Zone. Cell Rep. 2018;22:992–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan H, Gao Y, Ding Q, Liu J, Li Y, Jin M, Xu H, Ma S, Wang X, Zeng W, Chen Y. Exosomal Micro RNAs Derived from Dermal Papilla Cells Mediate Hair Follicle Stem Cell Proliferation and Differentiation. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:1368–1382. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.33233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Croker AK, Allan AL. Cancer stem cells: implications for the progression and treatment of metastatic disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:374–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ye S, Ding YF, Jia WH, Liu XL, Feng JY, Zhu Q, Cai SL, Yang YS, Lu QY, Huang XT, Yang JS, Jia SN, Ding GP, Wang YH, Zhou JJ, Chen YD, Yang WJ. SET Domain-Containing Protein 4 Epigenetically Controls Breast Cancer Stem Cell Quiescence. Cancer Res. 2019;79:4729–4743. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lechman ER, Gentner B, Ng SW, Schoof EM, van Galen P, Kennedy JA, Nucera S, Ciceri F, Kaufmann KB, Takayama N, Dobson SM, Trotman-Grant A, Krivdova G, Elzinga J, Mitchell A, Nilsson B, Hermans KG, Eppert K, Marke R, Isserlin R, Voisin V, Bader GD, Zandstra PW, Golub TR, Ebert BL, Lu J, Minden M, Wang JC, Naldini L, Dick JE. miR-126 Regulates Distinct Self-Renewal Outcomes in Normal and Malignant Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:214–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aulestia FJ, Néant I, Dong J, Haiech J, Kilhoffer MC, Moreau M, Leclerc C. Quiescence status of glioblastoma stem-like cells involves remodelling of Ca2+ signalling and mitochondrial shape. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9731. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28157-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Jin S, Dai P, Zhang T, Shi Y, Ai G, Shao X, Xie Y, Xu J, Chen Z, Gao Z. p57Kip2 is a master regulator of human adipose derived stem cell quiescence and senescence. Stem Cell Res. 2020;44:101759. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2020.101759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liggett WH Jr, Sidransky D. Role of the p16 tumor suppressor gene in cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1197–1206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.3.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai S, Kalisky T, Sahoo D, Dalerba P, Feng W, Lin Y, Qian D, Kong A, Yu J, Wang F, Chen EY, Scheeren FA, Kuo AH, Sikandar SS, Hisamori S, van Weele LJ, Heiser D, Sim S, Lam J, Quake S, Clarke MF. A Quiescent Bcl11b High Stem Cell Population Is Required for Maintenance of the Mammary Gland. Cell Stem Cell 2017; 20: 247-260. :e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harper JW, Adami GR, Wei N, Keyomarsi K, Elledge SJ. The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell. 1993;75:805–816. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90499-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the Light: The Growing Complexity of p53. Cell. 2009;137:413–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McConnell AM, Yao C, Yeckes AR, Wang Y, Selvaggio AS, Tang J, Kirsch DG, Stripp BR. p53 Regulates Progenitor Cell Quiescence and Differentiation in the Airway. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2173–2182. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinha S, Dwivedi TR, Yengkhom R, Bheemsetty VA, Abe T, Kiyonari H, VijayRaghavan K, Inamdar MS. Asrij/OCIAD1 suppresses CSN5-mediated p53 degradation and maintains mouse hematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Blood. 2019;133:2385–2400. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris EJ, Dyson NJ. Retinoblastoma protein partners. Adv Cancer Res. 2001;82:1–54. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(01)82001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim E, Cheng Y, Bolton-Gillespie E, Cai X, Ma C, Tarangelo A, Le L, Jambhekar M, Raman P, Hayer KE, Wertheim G, Speck NA, Tong W, Viatour P. Rb family proteins enforce the homeostasis of quiescent hematopoietic stem cells by repressing Socs3 expression. J Exp Med. 2017;214:1901–1912. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Semerci F, Choi WT, Bajic A, Thakkar A, Encinas JM, Depreux F, Segil N, Groves AK, Maletic-Savatic M. Lunatic fringe-mediated Notch signaling regulates adult hippocampal neural stem cell maintenance. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.24660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang R, Boareto M, Engler A, Louvi A, Giachino C, Iber D, Taylor V. Id4 Downstream of Notch2 Maintains Neural Stem Cell Quiescence in the Adult Hippocampus. Cell Rep 2019; 28: 1485-1498. :e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawai H, Kawaguchi D, Kuebrich BD, Kitamoto T, Yamaguchi M, Gotoh Y, Furutachi S. Area-Specific Regulation of Quiescent Neural Stem Cells by Notch3 in the Adult Mouse Subependymal Zone. J Neurosci. 2017;37:11867–11880. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0001-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basak O, Giachino C, Fiorini E, Macdonald HR, Taylor V. Neurogenic subventricular zone stem/progenitor cells are Notch1-dependent in their active but not quiescent state. J Neurosci. 2012;32:5654–5666. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0455-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baghdadi MB, Firmino J, Soni K, Evano B, Di Girolamo D, Mourikis P, Castel D, Tajbakhsh S. Notch-Induced miR-708 Antagonizes Satellite Cell Migration and Maintains Quiescence. Cell Stem Cell 2018; 23: 859-868. :e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verma M, Asakura Y, Murakonda BSR, Pengo T, Latroche C, Chazaud B, McLoon LK, Asakura A. Muscle Satellite Cell Cross-Talk with a Vascular Niche Maintains Quiescence via VEGF and Notch Signaling. Cell Stem Cell 2018; 23: 530-543. :e9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Low S, Barnes JL, Zammit PS, Beauchamp JR. Delta-Like 4 Activates Notch 3 to Regulate Self-Renewal in Skeletal Muscle Stem Cells. Stem Cells. 2018;36:458–466. doi: 10.1002/stem.2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yue F, Bi P, Wang C, Shan T, Nie Y, Ratliff TL, Gavin TP, Kuang S. Pten is necessary for the quiescence and maintenance of adult muscle stem cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14328. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mourikis P, Sambasivan R, Castel D, Rocheteau P, Bizzarro V, Tajbakhsh S. A critical requirement for notch signaling in maintenance of the quiescent skeletal muscle stem cell state. Stem Cells. 2012;30:243–252. doi: 10.1002/stem.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toh TB, Lim JJ, Chow EK. Epigenetics in cancer stem cells. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:29. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0596-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ntziachristos P, Abdel-Wahab O, Aifantis I. Emerging concepts of epigenetic dysregulation in hematological malignancies. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1016–1024. doi: 10.1038/ni.3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ito S, D'Alessio AC, Taranova OV, Hong K, Sowers LC, Zhang Y. Role of Tet proteins in 5mC to 5hmC conversion, ES-cell self-renewal and inner cell mass specification. Nature. 2010;466:1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nature09303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tie G, Yan J, Khair L, Tutto A, Messina LM. Hypercholesterolemia Accelerates the Aging Phenotypes of Hematopoietic Stem Cells by a Tet1-Dependent Pathway. Sci Rep. 2020;10:3567. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60403-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu T, Kitano A, Luu V, Dawson B, Hoegenauer KA, Lee BH, Nakada D. Bmi1 Suppresses Adipogenesis in the Hematopoietic Stem Cell Niche. Stem Cell Reports. 2019;13:545–558. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cantor DJ, David G. The chromatin-associated Sin3B protein is required for hematopoietic stem cell functions in mice. Blood. 2017;129:60–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-06-721746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu TX, Rothenberg ME. MicroRNA. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:1202–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Su Y, Yu Y, Liu C, Zhang Y, Liu C, Ge M, Li L, Lan M, Wang T, Li M, Liu F, Xiong L, Wang K, He T, Shi J, Song Y, Zhao Y, Li N, Yu Z, Meng Q. Fate decision of satellite cell differentiation and self-renewal by miR-31-IL34 axis. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:949–965. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0390-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knobloch M, Braun SM, Zurkirchen L, von Schoultz C, Zamboni N, Araúzo-Bravo MJ, Kovacs WJ, Karalay O, Suter U, Machado RA, Roccio M, Lutolf MP, Semenkovich CF, Jessberger S. Metabolic control of adult neural stem cell activity by Fasn-dependent lipogenesis. Nature. 2013;493:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knobloch M, Pilz GA, Ghesquière B, Kovacs WJ, Wegleiter T, Moore DL, Hruzova M, Zamboni N, Carmeliet P, Jessberger S. A Fatty Acid Oxidation-Dependent Metabolic Shift Regulates Adult Neural Stem Cell Activity. Cell Rep. 2017;20:2144–2155. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang R, Arif T, Kalmykova S, Kasianov A, Lin M, Menon V, Qiu J, Bernitz JM, Moore K, Lin F, Benson DL, Tzavaras N, Mahajan M, Papatsenko D, Ghaffari S. Restraining Lysosomal Activity Preserves Hematopoietic Stem Cell Quiescence and Potency. Cell Stem Cell 2020; 26: 359-376. :e7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin CL, Xu R, Yi JK, Li F, Chen J, Jones EC, Slutsky JB, Huang L, Rigas B, Cao J, Zhong X, Snider AJ, Obeid LM, Hannun YA, Mao C. Alkaline Ceramidase 1 Protects Mice from Premature Hair Loss by Maintaining the Homeostasis of Hair Follicle Stem Cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;9:1488–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:139–150. doi: 10.1038/nrm2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsai JJ, Dudakov JA, Takahashi K, Shieh JH, Velardi E, Holland AM, Singer NV, West ML, Smith OM, Young LF, Shono Y, Ghosh A, Hanash AM, Tran HT, Moore MA, van den Brink MR. Nrf2 regulates haematopoietic stem cell function. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:309–316. doi: 10.1038/ncb2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Theret M, Gsaier L, Schaffer B, Juban G, Ben Larbi S, Weiss-Gayet M, Bultot L, Collodet C, Foretz M, Desplanches D, Sanz P, Zang Z, Yang L, Vial G, Viollet B, Sakamoto K, Brunet A, Chazaud B, Mounier R. AMPKα1-LDH pathway regulates muscle stem cell self-renewal by controlling metabolic homeostasis. EMBO J. 2017;36:1946–1962. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ansó E, Weinberg SE, Diebold LP, Thompson BJ, Malinge S, Schumacker PT, Liu X, Zhang Y, Shao Z, Steadman M, Marsh KM, Xu J, Crispino JD, Chandel NS. The mitochondrial respiratory chain is essential for haematopoietic stem cell function. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:614–625. doi: 10.1038/ncb3529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu M, Zeng H, Chen S, Xu Y, Wang S, Tang Y, Wang X, Du C, Shen M, Chen F, Chen M, Wang C, Gao J, Wang F, Su Y, Wang J. SRC-3 is involved in maintaining hematopoietic stem cell quiescence by regulation of mitochondrial metabolism in mice. Blood. 2018;132:911–923. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-02-831669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flores A, Schell J, Krall AS, Jelinek D, Miranda M, Grigorian M, Braas D, White AC, Zhou JL, Graham NA, Graeber T, Seth P, Evseenko D, Coller HA, Rutter J, Christofk HR, Lowry WE. Lactate dehydrogenase activity drives hair follicle stem cell activation. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:1017–1026. doi: 10.1038/ncb3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 2011;147:728–741. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ho TT, Warr MR, Adelman ER, Lansinger OM, Flach J, Verovskaya EV, Figueroa ME, Passegué E. Autophagy maintains the metabolism and function of young and old stem cells. Nature. 2017;543:205–210. doi: 10.1038/nature21388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Milbrandt J. Nerve growth factor induces a gene homologous to the glucocorticoid receptor gene. Neuron. 1988;1:183–188. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Freire PR, Conneely OM. NR4A1 and NR4A3 restrict HSC proliferation via reciprocal regulation of C/EBPα and inflammatory signaling. Blood. 2018;131:1081–1093. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-07-795757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fu NY, Pal B, Chen Y, Jackling FC, Milevskiy M, Vaillant F, Capaldo BD, Guo F, Liu KH, Rios AC, Lim N, Kueh AJ, Virshup DM, Herold MJ, Tucker HO, Smyth GK, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE. Foxp1 Is Indispensable for Ductal Morphogenesis and Controls the Exit of Mammary Stem Cells from Quiescence. Dev Cell 2018; 47: 629-644. :e8. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siles L, Ninfali C, Cortés M, Darling DS, Postigo A. ZEB1 protects skeletal muscle from damage and is required for its regeneration. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1364. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08983-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bjornson CR, Cheung TH, Liu L, Tripathi PV, Steeper KM, Rando TA. Notch signaling is necessary to maintain quiescence in adult muscle stem cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30:232–242. doi: 10.1002/stem.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Andersen J, Urbán N, Achimastou A, Ito A, Simic M, Ullom K, Martynoga B, Lebel M, Göritz C, Frisén J, Nakafuku M, Guillemot F. A transcriptional mechanism integrating inputs from extracellular signals to activate hippocampal stem cells. Neuron. 2014;83:1085–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Urbán N, van den Berg DL, Forget A, Andersen J, Demmers JA, Hunt C, Ayrault O, Guillemot F. Return to quiescence of mouse neural stem cells by degradation of a proactivation protein. Science. 2016;353:292–295. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Birbrair A, Frenette PS. Niche heterogeneity in the bone marrow. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1370:82–96. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pinho S, Frenette PS. Haematopoietic stem cell activity and interactions with the niche. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:303–320. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0103-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Santos AJM, Lo YH, Mah AT, Kuo CJ. The Intestinal Stem Cell Niche: Homeostasis and Adaptations. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:1062–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Discher DE, Mooney DJ, Zandstra PW. Growth factors, matrices, and forces combine and control stem cells. Science. 2009;324:1673–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.1171643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hirata Y, Furuhashi K, Ishii H, Li HW, Pinho S, Ding L, Robson SC, Frenette PS, Fujisaki J. CD150high Bone Marrow Tregs Maintain Hematopoietic Stem Cell Quiescence and Immune Privilege via Adenosine. Cell Stem Cell 2018; 22: 445-453. :e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Derecka M, Herman JS, Cauchy P, Ramamoorthy S, Lupar E, Grün D, Grosschedl R. EBF1-deficient bone marrow stroma elicits persistent changes in HSC potential. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:261–273. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0595-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wilson A, Laurenti E, Oser G, van der Wath RC, Blanco-Bose W, Jaworski M, Offner S, Dunant CF, Eshkind L, Bockamp E, Lió P, Macdonald HR, Trumpp A. Hematopoietic stem cells reversibly switch from dormancy to self-renewal during homeostasis and repair. Cell. 2008;135:1118–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang C, Yi W, Li F, Du X, Wang H, Wu P, Peng C, Luo M, Hua W, Wong CC, Lee JJ, Li W, Chen Z, Ying S, Ju Z, Shen H. Eosinophil-derived CCL-6 impairs hematopoietic stem cell homeostasis. Cell Res. 2018;28:323–335. doi: 10.1038/cr.2018.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kokovay E, Wang Y, Kusek G, Wurster R, Lederman P, Lowry N, Shen Q, Temple S. VCAM1 is essential to maintain the structure of the SVZ niche and acts as an environmental sensor to regulate SVZ lineage progression. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goel AJ, Rieder MK, Arnold HH, Radice GL, Krauss RS. Niche Cadherins Control the Quiescence-to-Activation Transition in Muscle Stem Cells. Cell Rep. 2017;21:2236–2250. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu YF, Zhang SY, Chen YY, Shi K, Zou B, Liu J, Yang Q, Jiang H, Wei L, Li CZ, Zhao M, Gabrilovich DI, Zhang H, Zhou J. ICAM-1 Deficiency in the Bone Marrow Niche Impairs Quiescence and Repopulation of Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2018;11:258–273. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Acharya KR, Ackerman SJ. Eosinophil granule proteins: form and function. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:17406–17415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.546218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hirata Y, Kakiuchi M, Robson SC, Fujisaki J. CD150high CD4 T cells and CD150high regulatory T cells regulate hematopoietic stem cell quiescence via CD73. Haematologica. 2019;104:1136–1142. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.198283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen X, Deng H, Churchill MJ, Luchsinger LL, Du X, Chu TH, Friedman RA, Middelhoff M, Ding H, Tailor YH, Wang ALE, Liu H, Niu Z, Wang H, Jiang Z, Renders S, Ho SH, Shah SV, Tishchenko P, Chang W, Swayne TC, Munteanu L, Califano A, Takahashi R, Nagar KK, Renz BW, Worthley DL, Westphalen CB, Hayakawa Y, Asfaha S, Borot F, Lin CS, Snoeck HW, Mukherjee S, Wang TC. Bone Marrow Myeloid Cells Regulate Myeloid-Biased Hematopoietic Stem Cells via a Histamine-Dependent Feedback Loop. Cell Stem Cell 2017; 21: 747-760. :e7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Asada N, Kunisaki Y, Pierce H, Wang Z, Fernandez NF, Birbrair A, Ma'ayan A, Frenette PS. Differential cytokine contributions of perivascular haematopoietic stem cell niches. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:214–223. doi: 10.1038/ncb3475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ulum B, Mammadova A, Özyüncü Ö, Uçkan-Çetinkaya D, Yanık T, Aerts-Kaya F. Neuropeptide Y is involved in the regulation of quiescence of hematopoietic stem cells. Neuropeptides. 2020;80:102029. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2020.102029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eliazer S, Muncie JM, Christensen J, Sun X, D'Urso RS, Weaver VM, Brack AS. Wnt4 from the Niche Controls the Mechano-Properties and Quiescent State of Muscle Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2019; 25: 654-665. :e4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sampath SC, Sampath SC, Ho ATV, Corbel SY, Millstone JD, Lamb J, Walker J, Kinzel B, Schmedt C, Blau HM. Induction of muscle stem cell quiescence by the secreted niche factor Oncostatin M. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1531. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03876-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goncalves KA, Silberstein L, Li S, Severe N, Hu MG, Yang H, Scadden DT, Hu GF. Angiogenin Promotes Hematopoietic Regeneration by Dichotomously Regulating Quiescence of Stem and Progenitor Cells. Cell. 2016;166:894–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jiang L, Han X, Wang J, Wang C, Sun X, Xie J, Wu G, Phan H, Liu Z, Yeh ETH, Zhang C, Zhao M, Kang X. SHP-1 regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence by coordinating TGF-β signaling. J Exp Med. 2018;215:1337–1347. doi: 10.1084/jem.20171477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yi M, Li H, Wu Z, Yan J, Liu Q, Ou C, Chen M. A Promising Therapeutic Target for Metabolic Diseases: Neuropeptide Y Receptors in Humans. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;45:88–107. doi: 10.1159/000486225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yamazaki S, Iwama A, Takayanagi S, Eto K, Ema H, Nakauchi H. TGF-beta as a candidate bone marrow niche signal to induce hematopoietic stem cell hibernation. Blood. 2009;113:1250–1256. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-146480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Blank U, Karlsson S. TGF-β signaling in the control of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2015;125:3542–3550. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-618090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang X, Dong F, Zhang S, Yang W, Yu W, Wang Z, Zhang S, Wang J, Ma S, Wu P, Gao Y, Dong J, Tang F, Cheng T, Ema H. TGF-β1 Negatively Regulates the Number and Function of Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2018;11:274–287. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang ECE, Dai Z, Ferrante AW, Drake CG, Christiano AM. A Subset of TREM2+ Dermal Macrophages Secretes Oncostatin M to Maintain Hair Follicle Stem Cell Quiescence and Inhibit Hair Growth. Cell Stem Cell 2019; 24: 654-669. :e6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron. 2011;70:687–702. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Raymond A, Ensslin MA, Shur BD. SED1/MFG-E8: a bi-motif protein that orchestrates diverse cellular interactions. J Cell Biochem. 2009;106:957–966. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhou Y, Bond AM, Shade JE, Zhu Y, Davis CO, Wang X, Su Y, Yoon KJ, Phan AT, Chen WJ, Oh JH, Marsh-Armstrong N, Atabai K, Ming GL, Song H. Autocrine Mfge8 Signaling Prevents Developmental Exhaustion of the Adult Neural Stem Cell Pool. Cell Stem Cell 2018; 23: 444-452. :e4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]