Abstract

Ferroptosis, a relatively recently discovered type of cell death that is iron dependent and nonapoptotic, is involved in the accumulation of lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS), and has been shown to serve a vital role in various pathological processes, including those underlying neurodegeneration, ischemic reperfusion injury, acute organ injury, and in particular, tumor biology. Emerging evidence has highlighted the roles of ferroptosis in the development and resistance to chemoradiotherapy in cancer. Recently, an increasing number of studies have shown that non-coding RNAs modulate the process of ferroptotic cell death, and this has further highlighted the potential of regulation of ferroptosis as a means of cancer management. Although these studies have highlighted the critical role of ferroptosis in cancer therapeutics, the roles of ferroptosis induced by non-coding RNAs in cancer development remain unclear. Herein, the current body of knowledge of ferroptosis in cancer is summarized and an overview of the mechanisms of ferroptosis and the functions of non-coding RNAs in regulating ferroptotic cell death are discussed. The future status of ferroptosis in cancer management is deliberated and strategies for treatment of therapy-resistant cancers are discussed.

Keywords: ferroptosis, iron metabolism, lipid reactive oxygen species, non-coding RNAs, cancer therapeutics

1. Introduction

Ferroptosis, a novel form of regulated cell death (RCD), first proposed by Dixon et al (1) in 2012 and is characterized by the overwhelming iron-dependent accumulation of lethal lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS). The morphological hallmarks of ferroptotic death are a reduction or loss of mitochondrial cristae (1), condensation of the mitochondrial membrane (2) and rupture of the outer mitochondrial membrane (3). An initial characterization of ferroptotic biochemical demonstrated that cysteine depletion or inactivation of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) activity, which causes exhaustion of the intracellular pool of glutathione (GSH), iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation, specifically triggers this form of cell death (4). The genetic features of ferroptosis shows that it primarily dysregulates ferroptotic molecular on antioxidant metabolism, iron and lipid metabolism, such as SLC7A11, GPX4, TfR1, ACSL4, which are involved in the initiation of ferroptosis (5–7). As shown in Table I, there are no forms of morphological, biochemical, or genetic crosstalk between ferroptosis and other types of RCD, including apoptosis, autosis, pyroptosis, autophagy, necroptosis and various other forms of RCD.

Table I.

Characteristics of the primary types of RCD.

| First author, year | RCD (year of discovery) | Morphological features | Biochemical features | Genetic features | Regulatory pathways | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Duve et al, 1966 | Autophagy (1966) | Formation of double-membrane lysosomes | Increased lysosomal activity for the degradation and recycling of damaged proteins and organelles | ATG4/5/7/10/12, DRAM3, TFEB, Atg8, BECN1, LC3, BNIP3, ULK1/2, VPS34 | MAPK-ERK1/2-mTOR, PI3K/AKT/mTOR and p53 signaling pathways | (205) |

| Kerr et al, 1972 | Apoptosis (1972) | Cell shrinkage, plasma membrane blebbing, reduced cellular and nuclear volume, nuclear fragmentation, chromatin margination | Activation of caspases, exteriorization of phosphatidylserine, oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation | Caspase, P53, Fas, Bcl-2, Bax | Endoplasmic reticulum pathway; Caspase-, Death receptor-, P53-, and Bcl-2-mediated signaling pathways | (206) |

| Cookson et al, 2001 | Pyroptosis (2001) | Cell swelling and the formation of large bubbles from the plasma membrane, karyopyknosis | Proinflammatory cytokine releases, inflammatory caspases | GSDMD, Caspase-1, IL-1β, IL-18 | Caspase-1 and NLRP3-mediated signaling pathways | (207) |

| Degterev et al, 2005 | Necroptosis (2005) | Rapid swelling of cells and organelles, plasma membrane rupture, moderate chromatin condensation | Proinflammatory Response; decreased ATP levels; activation of RIP1, RIP3, and MLKL | TNFR1, RIPK1, TRADD, LEF1, RIP1, RIP3 | RIPK1/3-, MLKL-, TNFα-, TNFR1-, TLR3-, TRAIL-, -and PKC-MAPK-AP-1- mediated signaling pathways | (208) |

| Overholtzer et al, 2007 | Entosis (2007) | Formation of cell-in-cell structures, cell cannibalism, lack of ECM attachment | Internalization of one cell inside of another; adherens junction formation, lysosome-mediated degradation | Rho GTPase, ROCK, Par3/Par6/aPKC, Crumbs3/Pals1/Patj, Scribble/Lgl/Dlg | Rho–Rho-associated and ROCK-myosin pathways | (209) |

| Dixon et al, 2012 | Ferroptosis (2012) | Condensed mitochondrial membrane, reduced mitochondria crista or loss of mitochondria crista, outer mitochondrial membrane rupture | Iron and ROS accumulation, inhibition of xCT, reduced GSH, inhibition of GPX4 | xCT, GPX4, Nrf2, LSH, TFR1, ACSL4 | xCT and GPX4, RAS-RAF-MEK signaling pathway, p62-Keap1-Nrf2 pathway, LSH signaling pathway, MVA, HSF1-HSPB1 | (1) |

RCD, regulated cell death.

As a cellular process, ferroptosis can be triggered by various pathological conditions in humans and animals (4,8–10). Notably, emerging evidence has indicated that ferroptosis likely prevents tumorigenesis, such as gastric cancer (11), non-small-cell lung carcinoma (12), glioblastoma (13) and colorectal cancer (14). Ferroptosis is now accepted as an adaptive process in biological systems that acts as a tumor suppressive mechanism to eradicate the malignant cells, but the activation of oxidative stress pathways when metabolism is dysregulated leads to tumorigenesis (15). Interestingly, recent evidence has suggested that non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), particularly micro RNAs (miRNAs/miRs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and circular RNAs (circRNAs), serve vital roles in regulating ferroptosis (16). These ncRNAs are involved in iron metabolism, ROS metabolism and ferroptosis-related amino-acid metabolism, which regulates the process of ferroptosis initiation (17). Of particular interest, the accumulation of abundant lipid ROS in cells is the most critical factor for triggering ferroptosis (18). Conversely, ncRNAs can directly or indirectly regulating lipid ROS-related molecules to maintain redox dynamics during periods of high levels of ROS generation, and work to reduce ROS levels below toxic thresholds, which allows tumor cells to exhibit tolerances to relatively high levels of cellular ROS and avoids initiating ferroptosis (19). A moderate increase in cellular ROS levels promotes cell proliferation, survival and malignant transformation (19). These findings highlight the potential targets for anticancer treatments via genetic or pharmacological interference in ncRNA-regulated ferroptotic cell death. In the present review, the primary mechanism of ferroptosis initiation and the involvement of ncRNAs in ferroptosis in various types of cancer cells is summarized, with the aim of highlighting potentially novel strategies for personalized cancer treatment.

2. Mechanism of ferroptosis

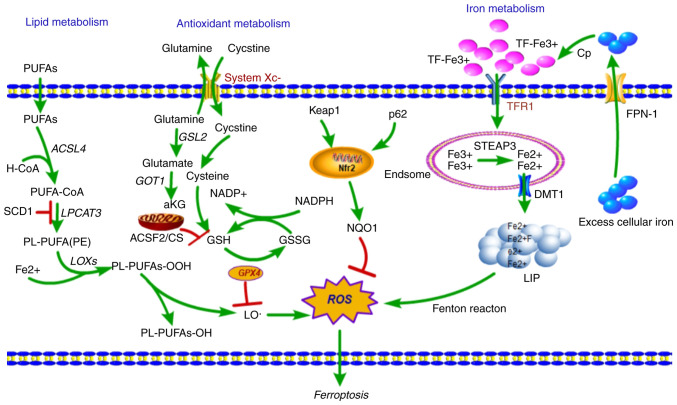

Iron metabolism

Iron is an essential nutrient, as it is necessary for the maintenance of cellular metabolism and all several important physiological activities, such as oxygen transport, DNA synthesis and ATP production (20). As iron is ubiquitously present, cellular iron homeostasis is a complex and tightly regulated process though the acquisition, utilization, storage and recycling of iron (5). The cellular iron balance is maintained through the redox cycle and iron intake (Fig. 1). The cellular iron redox cycle is primarily dependent on the Fenton reaction (21). In the cellular Fenton reaction, ferrous iron (Fe2+) is oxidized to ferric iron (Fe3+) during the conversion of H2O2 into reactive hydroxyl radicals; conversely, Fe3+ is then reduced back to Fe2+ through superoxide radicals (22). In of iron intake, transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) is expressed on the surface of the majority of cells, where it primarily takes up transferrin (TF)-bound iron into cells. The TfR1/TF-(Fe3+)2 complex is endocytosed (23), and Fe3+ is released from TF (24), reduced to Fe2+ by ferric reductase six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 3 (STEAP3), and then transported across the endosomal membrane by divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) (25).

Figure 1.

Overview of the mechanism of ferroptotic cell death. Fe3+ is loaded into the circulating apo-Tf, forming a TfR1-Tf-(Fe3+)2 complex, which is endocytosed by TfR1, and iron is released from TF at same time. Fe3+ is reduced to Fe2+ by the ferric reductase STEAP3, and Fe2+ is then transported to the cytosol by DMT1, where it enters the cytosolic LIP for various metabolic needs. Excess iron is effluxed into circulation by FPN-1 and an associated ferroxidase, which causes the production of ROS, in-turn initiating ferroptosis. Lipid metabolism: Fatty acids are activated (ACSL4) and esterified (LPCAT3) into PL-PUFAs, then LOXs catalyze the dioxygenation of PL-PUFAs and generate PL-PUFAs-OOH. Lipid-OOHs are regulated by the balance of GPX4 activity. An excess of PUFAs enhances generation of ROS and toxic lipid peroxides and simultaneously decreases GPX4 activity, which initiates ferroptosis. Ferroptosis-related amino-acid metabolism: System Xc- imports cystine in exchange for glutamate, which is reduced to cysteine and used to synthesize GSH, a necessary cofactor of GPX4 for eliminating ROS. GSH is an antioxidant particularly important in protecting cells from ferroptosis. TfR1, Transferrin receptor 1; TF, Transferrin; LIP, labile iron pool; DMT1, divalent metal transporter 1; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; STEAP3, six transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 3; FPN-1, ferroportin 1; ROS, reactive oxygen species; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids; LOXs, lipoxygenases; GSH, glutathione.

The imported cellular iron enters the transient cytosolic labile iron pool, a pool of chelatable and redox-active iron (26), which is utilized by cells for various metabolic processes or stored in ferritin (27). Excess cellular iron is exported out of the cell and transported into circulation by ferroportin 1 (FPN-1), after which it is oxidized by the ferroxidase-ceruloplasmin and binds to serum TF (28). Furthermore, cellular iron balance is also regulated by a network of iron-dependent proteins: The iron-responsive elements (IREs) and iron-regulatory proteins (IRPs). IRPs are cytosolic proteins that regulate the expression of genes involved in iron import (TfR1, DMT1), storage [ferritin (FTH), FTH1 and FTL] and export (FPN-1) by binding IREs (29).

Iron metabolism is an indispensable component of ferroptosis that distinguishes it from other types of RCD. Iron can gain and lose electrons, rendering it capable of contributing to free radical formation. When cellular iron is overloaded, the free radicals accumulate aberrantly, causing increased production of ROS. This effect leads to oxidative stress, which results in ferroptotic cell death (30). However, dysregulation of iron metabolism also serves an active role in carcinogenesis and promotes tumor growth (5,31).

TfR1 is a major regulator of intracellular iron uptake, and researchers found that abnormal accumulation of TfR1 on the cell surface is a specific marker of ferroptosis (32). In hepatocellular carcinoma, TfR1 and FTH1 are upregulated in erastin and sorafenib induced ferroptotic cell death (33), and TfR1 is also upregulated in erastin-induced cell death in myeloid leukemia cell lines (34). Furthermore, in Calu-1 lung cancer cells and HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cells, IRE-binding protein 2 (IREB2) is an essential gene for erastin-induced ferroptosis by regulating TFRC, FTH1 and FTL (1). Furthermore, several studies have suggested that inhibition of DMT1 may prevent iron translocation, leading to lysosomal iron overload, ROS production and ferroptotic cell death in cancer stem cells (35), and sulfasalazine induced ferroptosis is reduced by the inhibitory effect of estrogen receptor on TFRC and DMT1 in breast cancer cells (36). Artemisinin compounds sensitize cancer cells to ferroptosis by regulating IRP/IRE-controlled iron homeostasis (37). Therefore, targeting iron metabolic pathways may offer novel therapeutic options for cancer therapy.

Lipid metabolism

Fatty acid (FA) metabolism provides specific lipid precursors for energy storage, membrane biosynthesis, generation of signaling molecules and lipid oxidation that result in an accumulation of an abundance of lipid ROS (38). Although ferroptosis is induced by multiple stimuli, the accumulation of abundant lipid ROS in cells is the most critical factor causing ferroptotic cell death. In addition to iron-generated ROS production via the Fenton reaction, ROS from lipid oxidation appears to serve a role in ferroptosis (Fig. 1). Therefore, lipid peroxidation is crucial for induction of ferroptosis.

In the process of lipid metabolism, arachidonic acid (AA), a fatty acid substrate, is activated by acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) to produce AA-CoA, and then AA-CoA is esterified by lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) to phosphatidyl-(PE)-AA (39). PE-AA is oxidized to cytotoxic PE-AA-OOH by lipoxygenases (LOXs) that are activated during catalysis of Fe2+ (40). Under physiological conditions, glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) reduces cytotoxic PE-AA-OOH to non-cytotoxic PE-AA-OH, which protects cells from oxidative damage. When GPX4 is inactivated or depleted, PE-AA-OOH accumulates in the cell, and this induces ferroptosis (40). Thus, lipid peroxidation accounts for a large proportion of ferroptosis initiation.

ACSL4 is a key enzyme involved in the synthesis of long chain unsaturated fatty acids. ACSL4 was found to sensitize RSL3-induced ferroptosis through altering the cellular lipid composition (8). In hepatocellular carcinoma patients who had complete or partial responses to sorafenib-induced ferroptosis, and had higher ACSL4 expression in the pretreated tumor tissues than those who did not respond, ACSL4 was a predictive biomarker for sensitivity of sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma (41). Consistently, ACSL4 suppresses the proliferation of tumor cells through activation of ferroptosis in glioma cells (42). Furthermore, a CRISPR-based genetic screen identified ACSL4 and LPCAT3 as promoting of RSL3- and DPI7-induced ferroptosis, but they did not affect erastin-induced ferroptosis (39). Several studies have supported the conclusion that PUFAs can be oxidized, producing the lipid peroxides that promote the induction of ferroptosis (43). Therefore, targeting the lipid metabolism pathway may also be a novel means of tumor therapy.

Antioxidant metabolism

GSH, a thiol-containing tripeptide, is a potent antioxidant whose synthesis is limited by the constant import of cysteine and the availability of cystine/cysteine. The system Xc− antiporter is a cystine/glutamate transporter that takes up extracellular cystine in exchange for intracellular glutamate (44). SLC7A11, expressed at the cell surface, is a regulatory light chain component of the system Xc− transporter and is essential for cystine cellular uptake and serves a role in intracellular GSH synthesis (19). Once imported into cells, intracellular cystine is reduced to cysteine, a precursor of GSH used in GSH biosynthesis. GPX4, a central mediator of ferroptosis, which has phospholipid peroxidase activity, catalyzes the reduction of lipid peroxides to lipid alcohols using GSH as an essential co-factor, thus preventing cells from undergoing too much lipid peroxidation (45). Blockade of a member of the system Xc− antiporter, SLC7A11, and inhibition of GPX4 were shown to induce ferroptosis (1). Both interventions impaired cellular antioxidant defenses, thereby facilitating toxic ROS accumulation, suggesting antioxidant pathways as potential regulators of ferroptosis.

Erastin, a RAS-selective lethal compound, triggers ferroptosis by directly inhibiting system Xc− activity to reduce GSH levels in cancer cells (1,2). Similarly, sulfasalazine, a drug used to treat chronic inflammation, also triggers ferroptosis through directly inhibiting SLC7A11 activity (46). Similar to the above two compounds, p53, a well-characterized tumor suppressor, was also shown to sensitize cells to ferroptosis through the repression of SLC7A11 (47,48). Furthermore, the tumor suppressor BRCA1-associated protein 1 suppresses SLC7A11 transcription by decreasing H2Aub, leading to elevated lipid peroxidation and thus, increased ferroptosis (49). kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) can also suppress the expression of SLC7A11 through degrading the transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), which is a master transcription factor of the antioxidant response (50). Another molecular mechanism of ferroptosis is the direct suppression of GPX4 by promoting its degradation or the loss of its activity. GPX4 was identified as a target protein of the classical ferroptosis inducer RSL3 (51), which directly binds to GPX4 to inactivate the peroxidase activity of GPX4 and induce ferroptosis (52). Several ferroptosis inducers directly inhibit GPX4 function including DPI7, DPI10, DPI12, DPI13, DPI17, DPI18, DPI19 and ML162 (52,53), and several ferroptosis inducers have an indirect effect on GPX4 function, including SRS13–45 (46), SRS13-60 (46), buthionine (54), sulfoximine (52), DPI2 (52), lanperisone (55), sorafenib (56) and erastin derivatives (52). Taken together, these studies show that the SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis primarily mediates the initiation of ferroptosis, and that GPX4 serves a central role in regulating ferroptosis.

3. Role of ncRNAs in ferroptosis and cancer development

Well-established regulatory mechanisms that regulate changes in iron and ROS metabolism in cancer have recently been identified. ncRNAs are being increasingly recognized as vital regulatory mediators of ferroptosis.

miRNAs in ferroptosis

A set of miRNAs that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression by RNA silencing have been demonstrated to be involved in the regulation of iron and ROS metabolism. The levels of these miRNAs are directly or indirectly correlated with ferroptosis.

As shown in Table II, miRNAs can participate in the ferroptotic process. In A375 and G-361 melanoma cell lines, miR-9 directly suppresses glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 1 (GOT1) by binding to its 3′-UTR, which subsequently inhibited erastin- and RSL3-induced ferroptosis (57). In A549 and SPC-A-1 lung cancer cell lines, miR-6852 regulates the expression of cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS), a surrogate marker of ferroptosis, by competing for LINC00336, which increases the intracellular concentrations of iron, lipid ROS and mitochondrial superoxide and decreases the mitochondrial membrane potential (58). Another study showed that miR-137 suppressed erastin- and RSL3-induced ferroptosis through directly targeting the glutamine transporter SLC1A5 in melanoma (58). In the STKM2, MKN45 and OE33 gastric cancer cell lines, miR-4715-3p inhibited AURKA expression by directly targeting its 3′-UTR, leading to downregulation of expression of GPX4. Therefore, depletion of miR-4715-3p promoted ferroptotic cell death by inhibiting GPX4 (60). In MGC-803, MKN-45 and other gastric cancer cell lines, miR-103a-3p directly suppressed glutaminase 2 expression, promoting physcion 8-O-β-glucopyranoside-induced ferroptosis by increasing intracellular Fe2+ and ROS levels (61). miR-7-5p expression was shown to be upregulated in clinically relevant radioresistant (CRR) cells, and increased miR-7-5p levels could decrease mitoferrin levels and thus reduce Fe2+, causing CRR cells to suppress ferroptosis (62). miR-K12-11 was found to suppress BACH-1 to induce SLC7A11 expression, leading to Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus dissemination and persistence in an environment of oxidative stress via inhibition of ferroptosis (63). In endothelial cells, miR-17-92 directly suppressed the expression of ACSL4 by directly targeting A20, protecting endothelial cells from erastin-induced ferroptosis (64). In HepG2 and Hep3B cells, erastin enhanced the activation of transcription factor 4 (ATF4), whereas overexpression of miR-214-3p could sensitized cells to erastin-induced ferroptosis by directly suppressing the expression of ATF4 (65). miR-761 expression is downregulated in glioma, whereas overexpression of miR-761 confers resistance to erastin-induced ferroptosis by directly repressing integrin subunit β8 expression in LN229 and U251 cells (66).

Table II.

Summary of non-coding RNAs involved in ferroptosis.

| A, MicroRNA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| First author, year | Modulatory effect | Cell lines | (Refs.) |

| Zhang et al, 2018 | Decreases lipid peroxidation and inhibits erastin- and RSL3-induced ferroptosis | A375, G-361 | (57) |

| Wang et al, 2019 | Promotes ferroptosis by regulate CBS expression | ADC, A549, SPC-A-1, PC9 | (58) |

| Luo et al, 2018 | Suppresses erastin- and RSL3-induced ferroptosis by repression of SLC1A5 expression | A375, G-361 | (59) |

| Gomaa et al, 2019 | Overexpression confers resistance to ferroptosis by promoting of GPX4 | STKM2, MKN45, OE33 | (60) |

| Niu et al, 2019 | Promotes PG-induced ferroptosis by suppressing GLS2 expression | MGC-803, MKN-45 | (61) |

| Tomita et al, 2019 | Decreases mitoferrin and overexpression sensitizes to ferroptosis induced by radiation | HeLa, SAS | (62) |

| Qin et al, 2010 | Induces SLC7A11 expression and inhibits ferroptosis induced by oxidative stress | RAW | (63) |

| Xiao et al, 2019 | Suppresses erastin-induced ferroptosis by repression of ACSL4 expression | HUVECs | (64) |

| Bai et al, 2020 | Overexpression sensitizes to erastin-induced ferroptosis by directly target ATF4 | HepG2, Hep3B | (65) |

| Zhang et al, 2020 | Overexpression sensitizes to erastin-induced ferroptosis by directly target ITGB8 | LN229, U251 | (66) |

| B, Long non-coding RNA | |||

| First author, year | Modulatory effect | Cell lines | (Refs.) |

| Mao et al, 2018 | Knockdown suppresses erastin-induced ferroptosis | SPCA1, H522, A549 | (67) |

| Wang et al, 2019 | Overexpression suppresses erastin- and RSL3-induced ferroptosis by repression of CBS expression | ADC, A549, SPC-A-1, PC9 | (58) |

| Qi et al, 2019 | Knockdown sensitizes to erastin-induced ferroptosis by downregulating of GABPB1 | HepG2, Huh7, Hep3B | (68) |

| C, Circular RNA | |||

| First author, year | Modulatory effect | Cell lines | (Refs.) |

| Zhang et al, 2020 | Knockdown sensitizes to erastin-induced ferroptosis by directly target ITGB8 | LN229, U251 | (66) |

lncRNAs and circRNAs in ferroptosis

lncRNAs are a class of non-coding RNAs >200 nucleotides in length that function to regulate gene expression by epigenetic, transcriptional and translational modulation. lncRNAs have been implicated in various biological processes. Recent studies have shown dysregulation of several lncRNAs is also involved in the ferroptotic process (Table II).

lncRNA P53RRA is downregulated in lung cancer and acts as a tumor suppressor. In the cytoplasm, P53RRA interacts with G3BP1 to activate the p53 signaling pathway, which in-turn promotes erastin-induced ferroptosis by increasing lipid ROS and altering the iron concentration (67). lncRNA LINC00336 is upregulated in lung cancer and functions as an oncogene. LINC00336 competes with miR-6852 for CBS, inhibiting ferroptosis by decreasing iron concentrations, ROS and mitochondrial superoxide levels, as well as the mitochondrial membrane potential (58). lncRNA GABPB1-AS1 is an antisense lncRNA of GABPB1 that downregulates GABPB1 levels by blocking GABPB1 translation, leading to peroxiredoxin-5 peroxidase suppression and increased lipid ROS concentrations, ultimately promoting erastin-induced ferroptosis (68).

CircRNAs are class of non-coding RNA characterized by a covalently closed loop structure leaving no free ends and have been demonstrated to be involved in tumorigenesis. CircTTBK2 is upregulated in glioma and functions as a master regulator of CPEB4 by sponging miR-217. Knockdown of circTTBK2 promoted erastin-induced ferroptosis accompanied with an increase in the intracellular concentrations of ROS, iron and ferrous iron by competing with miR-217 for CBS in glioma cells (66).

NcRNA related modulators of ferroptosis

Iron metabolism (Table III), lipid metabolism (Table IV) and antioxidant metabolism (Table V) are basic functions in the ferroptotic process, and they serve a vital role in ferroptosis. The primary modulators of iron, lipid and antioxidant metabolism-related genes are also involved in regulating the process of ferroptosis and act as ferroptotic markers. Therefore, these metabolism-related ncRNAs may also be involved in regulating the process of ferroptosis.

Table III.

Summary of primary modulators of iron metabolism-related ncRNAs involved in ferroptosis.

| First author, year | Gene | Function | ncRNA | Modulatory effect | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schaar et al, 2009 | TfR1 | Cellular transferrin-iron uptake | miR-320 | Suppresses the expression of TfR1 directly | (69) |

| Fu et al, 2019 | miR-107 | (70) | |||

| Babu et al, 2019 | miR-148a | (71) | |||

| Miyazawa et al, 2018 | miR-7-5p, miR-141-3p | (72) | |||

| Kindrat et al, 2016 | miR-152 | (73) | |||

| Yoshioka et al, 2012 | miR-210 | (74) | |||

| Xu et al, 2015 | FTH1 | Subunit of major intracellular iron storage protein | miR-200b | Suppresses the expression of FTH1 directly | (75) |

| Chan et al, 2018 | miR-638, miR-362 | (76) | |||

| Di Sanzo et al, 2018 | miR-675 | (77) | |||

| Di Sanzo et al, 2018 | H19 | The pre-miRNA template for the miR-675 and suppresses the expression of FTH1 by miR-675 | (77) | ||

| Ripa et al, 2017 | IREB2 | Regulates iron levels | miR-29 | Suppresses the expression of | (78,79) |

| Zhang et al, 2017 | in the cells by regulating the translation and stability of mRNAs that affect iron homeostasis | IREB2 directly | |||

| Liu et al, 2019 | miR-935 | (80) | |||

| Andolfo et al, 2010 | DMT1 | Metal-iron transporter that is involved in iron | miR-Let-7d | Suppresses the expression of DMT1 directly | (81) |

| Jiang et al, 2019 | Absorption and use | miR-16, miR-195, miR-497, miR-15b | (82) |

ncRNA, non-coding RNA; miR, microRNA; TfR1, transferrin receptor 1; FTH1, ferritin heavy chain 1; IREB2, iron response element binding protein 2; DMT1, divalent metal transporter 1.

Table IV.

Summary of primary modulators of iron metabolism-related ncRNAs involved in ferroptosis.

| First author, year | Gene | Function | ncRNA | Modulatory Effect | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiang et al, 2020 | ACSL4 | Converts free fatty acids into fatty acyl-CoAs | miR-34a-5p/miR-204-5p | Suppresses the expression of ACSL4 directly | (85) |

| Park et al, 2018 | miR-141 | (86) | |||

| Wu et al, 2018 | miR-3595 | (87) | |||

| Bai et al, 2017; Ooi J et al, 2017 | miR-34a/c | (88,89) | |||

| Zhou et al, 2017 | miR-548p | (90) | |||

| Cui et al, 2014 | miR-205 | (91) | |||

| Peng et al, 2013 | miR-224-5p | (92) | |||

| Park et al, 2018 | miR-19b-3p/miR-17-5p/miR-130a-3p/miR-150-5p/miR-7a-5p/miR-144-3p/miR-16-5p | (93) | |||

| Jiang et al, 2020 | NEAT1 | Promotes the expression of ACSL4 by completing miR-34a-5p and miR-204-5p | (85) | ||

| Li et al, 2019 | LOXs | Catalyzes the dioxygenation of polyunsaturated fatty acids in lipids | miR-18a/miR-203 | Suppresses the expression of 15-LOX1 directly | (96) |

| Li et al, 2019 | miR-17/miR-20a/miR-20b/miR-106a/miR-106b/miR-93/miR-590-3p | Suppresses the expression of 15-LOX2 directly | (96) | ||

| Fredman et al, 2012 | miR-219-2 | Suppresses the expression of 15-LOX directly | (97) | ||

| Su et al, 2016 | miR-674-5p | Suppresses the expression of 5-LOX directly | (98) | ||

| Wang et al, 2018 | miR-216a-3p | (99) | |||

| Busch S et al, 2015 | miR-19a-3p/miR-125b-5p | (100) | |||

| Xue et al, 2018; Min et al, 2018 | GPX4 | Lipid repair enzyme | miR-181a-5p | Decreases protein expression of GPX4 by targeting SBP2 or SECISBP2 | (101,102) |

| Zhang et al, 2017 | SCD1 | Converts the saturated fatty acids palmitate and stearate to the monounsaturated fatty acids palmitoleate PMA and oleate | miR-27a | Suppresses the expression of SCD1 directly | (104) |

| Guo et al, 2017 | miR-212-5p | (105) | |||

| Zhang et al, 2020 | miR-103 | (106) | |||

| Mysore et al, 2016 | miR-192* | (107) | |||

| Zhang et al, 2016 | miR-378 | (108) | |||

| Guo et al, 2018 | miR-4668 | (109) | |||

| El et al, 2017 | miR-600 | (110) | |||

| Zhou et al, 2019 | miR-Let-7c | (111) | |||

| Guo et al, 2018 | uc.372 | Promotes the expression of SCD1 by completing miR-4668 | (109) | ||

| Zeng et al, 2016; Pinto et al, 2017 | CS | Regulates the metabolism of mitochondrial fatty acid | miR-122/ miR-19 | Suppresses the expression of SCD1 directly | (112,113) |

ncRNA, non-coding RNA; miR, microRNA; ACSL4, acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; SCD1, stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1; CS, citrate synthase.

Table V.

Summary of primary modulators of antioxidant metabolism-related ncRNAs involved in ferroptosis.

| First author, year | Gene | Function | ncRNA | Modulatory Effect | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luo et al, 2019; Zhao et al, 2019 | Nrf2 | Key regulator of anti-oxidant related genes expression | miR-675/miR-181 | Suppresses Nrf2 signaling | (114,115) |

| Zhang et al, 2019 | miR-302b-3p | Suppresses Nrf2 signaling by directly geting FGF15 | (116) | ||

| Wu et al, 2018; Zhou et al, 2019 | miR-141 | Suppresses Nrf2 signaling by directly targeting Keap1 | (117,118) | ||

| Reziwan et al, 2019 | miR-1225 | (119) | |||

| Duan et al, 2019 | miR-25 | Suppresses Nrf2 signaling by directly targeting KLF2 | (120) | ||

| Zhao et al, 2019 | miR-128-3p | Suppresses Nrf2 pathway by targeting Sirt1 | (121) | ||

| Liu et al, 2019 | miR-19b | Suppresses Nrf2 pathway by targeting SIRT1 | (122) | ||

| Chen et al, 2019 | miR-125b | Suppresses Nrf2 pathway by targeting PRXL2A | (123) | ||

| Ling et al, 2018 | miR-494 | Suppresses Nrf2 pathway by targeting NQO1 | (134) | ||

| Gao et al, 2018 | miR-365 | Suppresses the expression of Nrf2 directly | (135) | ||

| Geng et al, 2018 | miR-495 | Activates Nrf2 signaling by directly targeting PSD-93 | (126) | ||

| Wang et al, 2018 | miR-136 | (127) | |||

| Huang et al, 2018 | miR-34a | (128) | |||

| Wu et al, 2019 | miR-340-5p | (129) | |||

| Zhang et al, 2020 | miR-125b | (130) | |||

| Qin et al, 2019; Dong et al, 2019 | miR-101-3p | (131,132) | |||

| Chen et al, 2019 | miR-155 | (133) | |||

| Cai et al, 2019 | miR-380-3p | (134) | |||

| Srinoun et al, 2019; Yin et al, 2018; Li et al, 2019 | miR-144 | (135–137) | |||

| Zhu et al, 2019 | miR-153 | (138) | |||

| Khadrawy et al, 2019 | miR-28/ miR-708 | (139) | |||

| Sun et al, 2019 | miR-129-3p | (140) | |||

| Huang et al, 2019 | miR-27b | (141) | |||

| Liu et al, 2019 | miR-140-5p | (142) | |||

| Singh et al, 2013 | miR-93 | (143) | |||

| Chorley et al, 2012 | miR-365-1/ miR-193b/ miR-29-b1 | (144) | |||

| Zhang et al, 2019 | miR-152-3p | Activates Nrf2 signaling by directly targeting PSD-93 | (145) | ||

| Kim et al, 2014 | miR-101 | Activates Nrf2 signaling by directly targeting Cul3 | (146) | ||

| Xu et al, 2017 | miR-455 | (147) | |||

| Chen et al, 2019 | miR-601 | (148) | |||

| Kabaria et al, 2015 | miR-7 | Activates Nrf2 signaling by targeting Keap1 | (149) | ||

| Eades et al, 2011 | miR-200a | (150) | |||

| Wang et al, 2019 | miR-873-5p | (151) | |||

| Xiao et al, 2018 | miR-24-3p | (152) | |||

| Huang et al, 2019 | miR-34b | (153) | |||

| Ding et al, 2019 | miR-223 | (154) | |||

| Li et al, 2019 | miR-146b-5p | Activates Nrf2 signaling by targeting Brd4 | (155) | ||

| Sun et al, 2018 | miR-98-5p | Activates Nrf2 signaling by targeting Bach1 | (156) | ||

| Feng et al, 2019 | Blnc1 | Activates Nrf2 signaling | (157) | ||

| Li et al, 2019; Fan et al, 2018; Chen et al, 2018; Amodio et al, 2018; Zeng et al, 2018 | MALAT1 | (158–162) | |||

| Joo et al, 2019 | Nrf2-lncRNA | (163) | |||

| Liu et al, 2019 | AK094457 | (164) | |||

| Porsch et al, 2019 | Linc01213 | (165) | |||

| Xiao X et al, 2019 | lncRNA 74.1 | (166) | |||

| Gao et al, 2017 | ODRUL | (167) | |||

| Dong et al, 2018 | SNHG14 | Activates Nrf2 signaling by directly targeting PABPC1 | (168) | ||

| Geng et al, 2018 | UCA1 | Increases the expression of Nrf2 by miR-495 | (126) | ||

| Luzon-Toro et al, 2019 | LUCAT1 | Increases the expression of Nrf2 | (169) | ||

| Sun et al, 2019; Zhang et al, 2019; Gong et al, 2019 | TUG1 | (170–172) | |||

| Wu et al, 2017 | Loc344887 | (173) | |||

| Zheng et al, 2016 | H19 | (174) | |||

| Li et al, 2016 | Mhrt | (175) | |||

| Zhou et al, 2015 | MIAT | (176) | |||

| Yuan et al, 2015 | MRAK052686 | (177) | |||

| Zhao et al, 2015 | AATBC | (178) | |||

| Zhang et al, 2015 | HOTAIR | (179) | |||

| Wu et al, 2019 | NRAL | Activates the expression of Nrf2 by miR-340-5p | (129) | ||

| Luo et al, 2019 | H19 | Suppresses Nrf2 signaling | (114) | ||

| Li et al, 2017 | Sox2OT | (180) | |||

| Gao et al, 2018 | MT1DP | Activates the expression of Nrf2 by miR-365 | (125) | ||

| Wang et al, 2018; Huang et al, 2018; Wang et al, 2017 | MEG3 | Activates the expression of Nrf2 by miR-136 or miR-34a | (127, 128, 181) | ||

| Wu et al, 2018 | KRAL | Activates Nrf2 signaling by directly targeting Keap1 | (117) | ||

| Li et al, 2020 | circ4099 | Activates Nrf2 signaling | (182) | ||

| Drayton et al, 2014 | SLC7A11 | Subunit of system Xc− to import cystine | miR-27a | Suppresses the expression of SLC7A11 directly | (183) |

| Wu et al, 2017 | miR-375 | (184) | |||

| Liu et al, 2011 | miR-26b | (185) | |||

| Luo et al, 2017 | SLC7A11-AS1 | Suppresses the expression of SLC7A11 | (186) | ||

| Yuan et al, 2017 | AS-SLC7A11 | (187) | |||

| Xian et al, 2020 | Keap1 | Binds to and regulates Nrf2 by keeping its levels | miR-26b | Suppresses the expression of Keap1 directly | (190) |

| Li et al, 2020 | miR-941 | (191) | |||

| Jiang et al, 2020; Wang et al, 2020 | miR-200a | (192,193) | |||

| Duan et al, 2019 | miR-421 | (194) | |||

| Xu et al, 2019 | miR-626 | (195) | |||

| Reziwan et al, 2019 | miR-1225 | (119) | |||

| Zhou et al, 2019 | miR-141 | (118) | |||

| Akdemir et al, 2017 | miR-432 | (196) | |||

| Amodio et al, 2018 | MALAT1 | Epigenetically regulates Keap1 | (161) | ||

| Wu et al, 2018 | KRAL | Activates Nrf2 signaling by completing with miR-141 | (127) | ||

| Zhang et al, 2018; Wang et al, 2019 | GOT1 | Synthesis of a-ketoglutarate from glutamate | miR-9 | Suppresses the expression of Keap1 directly | (57,198) |

ncRNA, non-coding RNA; miR, microRNA; nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; Keap1, kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1.

Iron metabolism

Previous studies have demonstrated that cellular iron overload causes ferroptosis. TfR1 is a critical transporter involved in iron uptake and a specific ferroptosis marker, which imports Tf-iron from the extracellular environment into cells, contributing to the cellular iron pool required for ferroptosis (32). miR-320 (69), miR-107 (70), miR-148a (71), miR-7-5p/miR-141-3p (72), miR-152 (73) and miR-210 (74) are all involved in suppression of TfR1 by directly targeting TfR1. Therefore, it has been reasonably shown that these miRNAs can suppress ferroptosis by targeting TfR1.

FTH1, a major intracellular iron storage protein, is an iron regulators involved in iron storage. Expression levels of FTH1 are regulated by oncogenic RAS signaling, which controls the cellular iron pool and ferroptosis sensitivity in tumor cells (51). FTH1 is regulated by NRF2 in ferroptosis, knockdown of FTH1 enhances erastin or sorafenib-induced ferroptosis sensitivity in hepatocellular carcinoma, suggesting that reduced iron storage may contribute to cellular iron overload causing ferroptosis and that FTH1 may serve as a specific marker of ferroptosis marker as well (54). miR-200b is involved in the repression of FTH1 by directly targeting FTH1, which transforms H2O2 and O2 into the reactive •OH radical, thus inducing tumor cell death (75). Oncogenic miR-638 and miR-362 have been identified as targets of FTH1 transcript or multiple FTH1 pseudogenes by an unbiased screen in prostate cancer (76). lncRNA H19 is the pre-miRNA template of miR-675, and knockdown of FTH1 upregulates H19 expression and thus its cognate miR-675, and H19/miR-675 activation primarily contributes to altered iron metabolism induced by FTH1 silencing (77). Therefore, it has been reasonably confirmed that these miRNAs may suppress ferroptosis by targeting TfR1. Together, these studies have shown that these ncRNAs may be involved in regulating the process of ferroptosis through iron storage.

IREB2 is an intra-cellular iron metabolism RNA-binding protein which regulates the translation and the stability of iron homeostasis related genes. Knock down of IREB2 suppresses erastin-induced ferroptosis by amino acid/cystine deprivation (1). miR-29 regulates IREB2 directly, thus affecting both energy production and redox status of the cell (78). Furthermore, miR-29a-related genetic variants alter the expression of IREB2 and may modify the risk of lung cancer together with dietary iron intake (79). Oncogenic miR-935 is elevated in renal cell carcinoma, and miR-935 directly suppresses the transcription of IREB2 by binding to the 3′-UTRs of IREB2 (80). Therefore, these miRNAs may suppress ferroptosis by targeting IREB2.

DMT1 is a widely expressed key iron transporter located within the plasma membrane and membranes of lysosomes and endosomes, which enables the uptake of Fe2+ to the cytosol following iron endocytosis. DMT1 inhibitors were selected as a target in cancer stem cells by blocking lysosomal iron translocation, which leads to lysosomal iron accumulation, and thus production of ROS and induction of ferroptotic cell death (35). DMT1 is also involved in sulfasalazine-induced ferroptosis via activation of iron metabolism in breast cancer cells (36). miR-Let-7d binds to the 3′-UTR of DMT1-IRE decreasing its expression at both the mRNA and protein levels in K562 and HEL cells (81). miR-16 family members miR-16, miR-195, miR-497 and miR-15b have been shown to suppress intestinal DMT1 expression by targeting DMT1 3′-UTR in HCT116 cells (82). These miRNAs may be involved in ferroptosis by targeting DMT1.

Lipid metabolism

ACSL is expressed on the mitochondrial outer membrane and endoplasmic reticulum, where they catalyze fatty acids to form acyl-CoAs, which are lipid metabolic intermediates that facilitate fatty acid metabolism and membrane modifications (83). According to genome-wide recessive genetic screening, ACSL4 has been identified as an essential pro-ferroptotic gene and as a critical determinant of ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition (8). Another study also showed that ACSL4 is a biomarker and contributor of ferroptosis via ACSL4-mediated production of 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (5-HETE) (84). miR-34a-5p/miR-204-5p (85), miR-141 (86), miR-3595 (87), miR-34a/c (88,89), miR-548p (90), miR-205 (91), miR-224-5p (92) and miR-19b-3p/miR-17-5p/miR-130a-3p/miR-150-5p/miR-7a-5p/miR-144-3p/miR-16-5p (93) can suppress the transcription of ACSL4. These miRNAs may inhibit ferroptosis by targeting ACSL4. In addition, a recent study reported that lncRNA NEAT1 promotes the transcription of ACSL4 by competing with miR-34a-5p and miR-204-5p, which may suppress ferroptosis (85).

LOXs are a family of iron-containing enzymes, including six LOX genes in humans; LOX5, LOX12, LOX12B, LOX15, LOX15B and LOXE3 (94). These genes can catalyze dioxygenation of PUFAs to produce fatty acid hydroperoxides in a stereospecific manner (94). Oxidation of PUFAs by LOXs had been implicated in erastin-induced ferroptosis (94). LOX15-driven enzymatic generation of lipid peroxidation is a hallmark of ferroptotic signals (95). In the miR-17 family, miR-18a and miR-203 bind to four sites of the 3′-UTR in 15-LOX1, and miR-17, miR-20a, miR-20b, miR-106a, miR-106b, miR-93 and miR-590-3p bind to four sites of the 3′-UTR of 15-LOX2 (96). Oncogenic miR-219-2 (97) directly targets the 3′-UTR of 15-LOX, whereas miR-674-5p (98), miR-216a-3p (99) and miR-19a-3p/miR-125b-5p (100) regulate 5-LOX through directly targeting the 3′-UTR of 5-LOX.

GPX4, unlike other members of the GPX family, serve a unique role in physiology; they catalyze the reduction of lipid peroxides in a complex cellular membrane environment. Overexpression or knockdown of GPX4 modulates the lethality of ferroptosis inducers, indicating that GPX4 is an essential regulator of ferroptotic cell death (52). miR-181a-5p decreases the expression of GPX4 by targeting SBP2 or SECISBP2 and reduces the ability to counter oxidation, which may promote ferroptosis (101,102).

Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) is a rate-limiting step catalytic enzyme in mono-unsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) synthesis that serves a central role in FA metabolism by converting the saturated fatty acids palmitate and stearate to the MUFAs palmitoleate (PMA) and oleate. SCD1, as an inhibitor of ferroptosis, serves an important role in the negative regulation of ferroptosis through the products of MUFAs (103). miR-27a (104), miR-212-5p (105), miR-103 (106), miR-192* (107), miR-378 (108), miR-4668 (109), miR-600 (110) and let-7c (111) significantly suppress the relative expression of SCD1 by directly binding to its 3′-UTR. Moreover, lncRNA uc.372 promotes the transcription of SCD1 by competing with miR-4668 (109).

Citrate synthases (CSs) are implicated in the regulation of mitochondrial fatty acid metabolism, which supply a specific lipid precursor necessary for ferroptotic cell death (1). Silencing CS suppresses erastin-induced ferroptosis (1). miR-122 suppresses the expression of mRNAs and proteins related to CS (112), whereas miR-19 only regulates the expression of proteins related to CS (113). Therefore, these ncRNAs have been implicated in promoting ferroptosis by targeting lipid metabolism-related genes.

Antioxidant metabolism

Nrf2 is a pivotal inhibitor of ferroptosis due to its ability to inhibit cellular iron uptake, limit ROS production, and upregulate SLC7A11 expression by regulating the Nrf2-targeted genes FTH1, HO-1 and NQO1. Certain miRNAs can directly or indirectly suppress the transcription of Nrf2 or Nrf2 signaling to promote ferroptosis. For example, miR-675 (114), miR-181 (115), miR-302b-3p (116), miR-141 (117,118), miR-1225 (119), miR-25 (120), miR-128-3p (121), miR-19b (122), miR-125b (123) and miR-494 (124) restrain Nrf2 signaling by targeting Nrf2-related genes. In contrast, miR-365 (125), miR-495 (126), miR-136 (127), miR-34a (128), miR-340-5p (129), miR-125b (130), miR-101-3p (131,132), miR-155 (133), miR-380-3p (134), miR-144 (135–137), miR-153 (138), miR-28/miR-708 (139), miR-129-3p (140), miR-27b (141), miR-140-5p (142), miR-93 (143) and miR-365-1/miR-193b/miR-29-b1 (144) have been shown to decrease Nrf2 levels through directly binding to the 3′-UTR of Nrf2. Additionally, certain miRNAs activate Nrf2 signaling via a variety of mechanisms, ultimately resulting in inhibition of ferroptosis. For example, miR-152-3p (145), miR-101 (146), miR-455 (147), miR-601 (148), miR-7 (149), miR-200a (150), miR-873-5p (151), miR-24-3p (152), miR-34b (153), miR-223 (154), miR-146b-5p (155) and miR-98-5p (156) activate Nrf2 signaling by targeting Nrf2-related genes. It is thus hypothesized that these miRNAs can regulate ferroptosis by targeting Nrf2, but this has not yet been demonstrated.

Emerging evidence has indicated that lncRNAs Blnc1 (157), MALAT1 (158–162), Nrf2-lncRNA (163), AK094457 (164), Linc01213 (165), lncRNA74.1 (166), ODRUL (167), SNHG14 (168), UCA1 (126), LUCAT1 (169), TUG1 (170–172), Loc344887 (173), H19 (174), Mhrt (175), MIAT (176), MRAK052686 (177), AATBC (178), HOTAIR (179), NRAL (129), H19 (114), Sox2OT (180), MT1DP (125), MEG3 (127,128,181) and KRAL (117) may activate Nrf2 signaling by targeting Nrf2-related genes. Furthermore, circRNA-4099 may activate Nrf2 signaling by targeting miR-706, which augments H2O2-induced cell damage in the L02 cells (182). Notably, these ncRNAs are involved in regulating ferroptosis and may be a potential target for cancer therapy.

SLC7A11, the subunit of cystine-glutamate antiporter, is a crucial mediator in the process of ferroptosis. Studies have shown that miR-27a (183), miR-375 (184) and miR-26b (185) directly suppress the transcription of SLC7A11 by binding to its 3′-UTR. Therefore, these miRNAs have been implicated in promoting ferroptosis by directly targeting SLC7A11. Furthermore, lncRNAs SLC7A11-AS1 (186) and AS-SLC7A11 (187), the antisense lncRNAs of SLC7A11, suppress the transcription of SLC7A11. Therefore, these two SLC7A11-antisense lncRNAs have been hypothesized to suppress ferroptosis by downregulating SLC7A11 levels.

Keap1 is a member of the BTB-kelch protein family, which are primarily located in the perinuclear region of the cytoplasm (188). Keap1 represses Nrf2 transcriptional activity, a transcriptional target of Keap1. Overexpression of Keap1 enhanced erastin- and RSL3-induced ferroptosis, while knockdown conferred resistance to ferroptosis (189). Studies have shown that overexpression of miR-7 (149), miR-873-5p (151), miR-24-3p (152), miR-34b (153), miR-223 (154), miR-26b (190), miR-941 (191), miR-200a (192,193), miRNA-421 (194), miR-626 (195), miR-1225 (119), miR-141 (118) and miR-432 (196) suppressed Keap1 3′-UTR expression and downregulated its mRNA and protein expression. Notably, lncRNA MALAT1 could epigenetically downregulate Keap1 expression (161). lncRNA KRAL functions as a ceRNA by effectively binding to miR-141 and then restoring Keap1 expression (117). These studies suggest that Keap1 related-ncRNAs are involved in the process of ferroptosis.

GOT1 is essential for cell sustaining proliferation and maintenance of redox homeostasis. Reduced GOT1 suppresses erastin-induced ferroptosis by amino acid/cystine deprivation (197). According to previous studies, both in pancreatic cancer and melanoma, miR-9-5p inhibited the expression of GOT1 by directly binding to its 3′-UTR, ultimately resulting in decreased proliferation, glutamine metabolism and redox homeostasis, which suppresses the process of ferroptosis (57,198).

Collectively, the modulators of ferroptotic markers are their related ncRNAs, which serve critical roles in the regulation of ferroptosis. As discussed above, ncRNAs possess tumor suppressor or oncogenic roles in the process of ferroptosis during the course of tumorigenesis and progression. Thus, targeting ncRNAs may be a viable strategy in the development of novel cancer treatments.

4. Therapeutic approaches for ncRNAs targeting ferroptosis in cancer

Ferroptosis likely inhibits tumor development and/or progression, thus inducing ferroptosis is a promising strategy for anticancer therapy. ncRNA expression patterns show specificity for specific tumor and tissue types, highlighting ncRNAs as potential therapeutic targets in cancer. With advances in biotechnologies, such as genome editing, high-throughput sequencing and nanotechnology, ncRNAs can be theoretically used as molecular targets for cancer therapy. Therefore, ncRNAs are considered as an emerging and viable candidates for precision medicine depending on its property of tissue-specific expression.

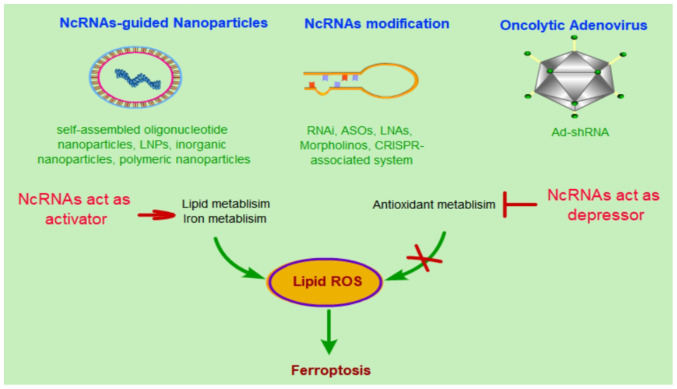

Thus far, among the annotated ncRNAs, miRNAs, lncRNAs and circRNAs are the most extensively investigated. They function as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors, which induce or inhibit ferroptosis by targeting their mRNAs, respectively. Previously, several preclinical studies have investigated RNA-guided precision medicine for cancer treatment (161,199–201). For example, miR-34a mimic-mediated tumor suppression was the first miRNA-based therapy to be used in the clinic (202). lncRNA MALAT1 with antisense oligonucleotide-conjugated nanostructure inhibited metastasis of lung cancer cells (203). In total, three strategies have been proposed for ncRNA-based therapy: i) ncRNA-guided nanoparticles, ii) ncRNA modification and iii) an oncolytic adenovirus strategy (204).

The methods described above are currently the most promising ncRNA-based treatment strategies for cancer. These therapeutic approaches can also be used in ncRNAs targeting ferroptosis for cancer treatment. Most of the ncRNAs regulate lipid ROS-related molecules and antioxidant metabolism-related molecules, which leads to increased tumor cell tolerance for relatively higher ROS levels and thus reduced possibility of initiating ferroptosis. At same time, high levels of cellular ROS promote tumor cell growth. To initiate ferroptotic cell death, stimulating ncRNAs need to activate lipid and iron metabolism or otherwise activate antioxidant metabolism, which in turn leads to an accumulation of cellular ROS and eventually cell death (Fig. 2). Thus, ncRNAs have been considered not only as therapeutic targets for cancer therapy, but also as potentially promising therapeutic tools for precision medicine. However, the majority of studies regarding the use of ncRNAs therapeutically are still in their early stages. Several problems need to be overcome before they can be used clinically, such as the off-target effects, short half-life, severe toxicity and low transfection efficiency in ncRNA guided strategies (204). A large number of further studies are still required.

Figure 2.

Therapeutic approaches for use of ncRNAs for targeting ferroptosis in cancer. In anticancer approaches, induction of the occurrence of ferroptosis by lipid ROS is the primary approach of ferroptosis based cancer therapy. Targeting ncRNA-related ferroptosis via activation of lipid and iron metabolism or suppression of antioxidant metabolism by ncRNA-guided nanoparticles, ncRNA modification or oncolytic adenovirus strategy. NcRNA-guided nanoparticles strategies primarily include self-assembled oligonucleotide nanoparticles, LNPs, inorganic nanoparticles, and polymeric nanoparticles; ncRNA modification strategies primarily include RNAi, ASOs, LNAs, Morpholinos and CRISPR-associated system; and oncolytic adenovirus strategies primarily includes the use of Ad-shRNA. LNPs, lipid-based nanoparticles; RNAi, double stranded RNA-mediated interference; ASOs, single stranded antisense oligonucleotides; LNAs, locked nucleic acids; Ad-shRNA, adenovirus-shRNA. ncRNA, non-coding RNA; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

5. Conclusions and future perspectives

Ferroptosis is a novel type of cell death with distinct functions intricately involved in numerous physiological processes and various diseases. Substantial progress in exploring the mechanisms of ferroptosis and understanding on how oncogenic states drive sensitivity to ferroptosis has been made. Collectively, these studies have demonstrated ferroptosis as a tumor suppressive mechanism that inhibits tumor growth and contributes to chemotherapy sensitivity, and that induction of ferroptosis is a viable anticancer therapeutic strategy, particularly for drug-resistant tumors.

However, cellular sensitivity to ferroptosis likely depends on the cell type and physiological conditions. What types of physiological processes are associated with ferroptosis? Under what context do cells benefit from ferroptotic cell death? Studies exploring the association between cancer and ferroptosis are still limited. Although several candidate primary markers of ferroptosis have been identified, and the pathways they target are known, several candidates fail to acquire their special cellular conditions and exhibit poor pharmacokinetics. A large number of recent studies have demonstrated that miRNAs, lncRNAs and circRNAs serve an important role in the process of ferroptosis, and that these ncRNAs may affect the regulation of ferroptosis in a cell type-dependent or tissue type-dependent manner. Due to the heterogeneity of gene expression on a per individual basis, ncRNA-based treatment strategies can be used for personalized cancer treatment and may eventually exhibit more specificity than ferroptosis-inducing drugs such as erastin, sulfasalazine and RSL3. Thus, targeting ncRNAs may at present be considered a prototypic intervention which has the potential to be superior in terms of precision compared with established anti-tumor drugs. Moreover, with the development of gene related technologies, ncRNAs constitute promising potential targets for gene therapy. However, a deeper understanding of the mechanisms by which ncRNAs regulate ferroptosis is still required, and tissue specific expression of ncRNAs and the variety of off-target effects are major challenges.

In summary, ncRNAs may serve as anticancer targets by regulating ferroptosis, which is a novel and promising means of treating drug-resistant cancer. Targeting key ncRNA-related ferroptotic molecules may create novel opportunities for gene therapy for the treatment of cancer.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- RCD

regulated cell death

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- PUFAs

polyunsaturated fatty acids

- GSH

glutathione

- GPX4

glutathione peroxidase 4

- ncRNAs

non-coding RNAs

- miRNA

microRNA

- lncRNA

long non-coding RNA

- circRNA

circular RNA

- Fe2+

ferrous iron

- Fe3+

ferric iron

- TfR1

Transferrin receptor 1

- TF

Transferrin

- STEAP3

six transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 3

- IREs

iron-responsive elements

- DMT1

divalent metal transporter 1

- IRPs

iron-regulatory proteins

- FPN-1

ferroportin 1

- FTH1

ferritin heavy chain 1

- TFRC

transferrin receptor

- FTH

ferritin

- FTL

ferritin light polypeptide

- HSPB1

heat-shock 27-kDa protein 1

- LOXs

lipoxygenases

- ACSL4

acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4

- LPCAT3

lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3

- CS

citrate synthase

- IREB2

iron response element binding protein 2

- SCD1

stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1

- AA

arachidonic acid

- system xc-

cystine/glutamate transporter

- Nrf2

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

- Keap1

kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- GOT1

glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 1

- CRR

clinically relevant radioresistant

- ATF4

activation of transcription factor 4

Funding

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) through grants no. 81270561 and Program of High-level Talents Introduction in the First Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu Medical College through grants no. CYFY-GQ17.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YL and QH wrote the manuscript. YL, QH, BH, YL and SH created the figures and tables. YL and JX conceived the topic of this review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS, et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149:1060–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yagoda N, von Rechenberg M, Zaganjor E, Bauer AJ, Yang WS, Fridman DJ, Wolpaw AJ, Smukste I, Peltier JM, Boniface JJ, et al. RAS-RAF-MEK-dependent oxidative cell death involving voltage-dependent anion channels. Nature. 2007;447:864–868. doi: 10.1038/nature05859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedmann Angeli JP, Schneider M, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Hammond VJ, Herbach N, Aichler M, Walch A, Eggenhofer E, et al. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:1180–1191. doi: 10.1038/ncb3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon SJ. Ferroptosis: Bug or feature? Immunol Rev. 2017;277:150–157. doi: 10.1111/imr.12533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manz DH, Blanchette NL, Paul BT, Torti FM, Torti SV. Iron and cancer: Recent insights. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2016;1368:149–161. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carbone M, Melino G. Lipid metabolism offers anticancer treatment by regulating ferroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26:2516–2519. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0418-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desideri E, Ciccarone F, Ciriolo MR. Targeting glutathione metabolism: Partner in crime in anticancer therapy. Nutrients. 2019;11:1926. doi: 10.3390/nu11081926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, Irmler M, Beckers J, Aichler M, Walch A, et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:91–98. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X, Xu S, Zhao C, Liu B. Role of TLR4/NADPH oxidase 4 pathway in promoting cell death through autophagy and ferroptosis during heart failure. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;516:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang N, Zeng GZ, Yin JL, Bian ZX. Artesunate activates the ATF4-CHOP-CHAC1 pathway and affects ferroptosis in Burkitt's Lymphoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;519:533–539. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang C, Shi M, Ji J, Cai Q, Zhao Q, Jiang J, Liu J, Zhang H, Zhu Z, Zhang J. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) facilitates the growth and anti-ferroptosis of gastric cancer cells and predicts poor prognosis of gastric cancer. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:15374–15391. doi: 10.18632/aging.103598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu P, Wu D, Duan J, Xiao H, Zhou Y, Zhao L, Feng Y. NRF2 regulates the sensitivity of human NSCLC cells to cystine deprivation-induced ferroptosis via FOCAD-FAK signaling pathway. Redox Biol. 2020;37:101702. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Fu X, Jia J, Wikerholmen T, Xi K, Kong Y, Wang J, Chen H, Ma Y, Li Z, et al. Glioblastoma therapy using codelivery of cisplatin and glutathione peroxidase targeting siRNA from iron oxide nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12:43408–43421. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma P, Shimura T, Banwait JK, Goel A. Andrographis-mediated chemosensitization through activation of ferroptosis and suppression of β-catenin/Wnt-signaling pathways in colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2020;41:1385–1394. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgaa090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fanzani A, Poli M. Iron, oxidative damage and ferroptosis in rhabdomyosarcoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1718. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mou Y, Wang J, Wu J, He D, Zhang C, Duan C, Li B. Ferroptosis, a new form of cell death: Opportunities and challenges in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:34. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0720-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fearnhead HO, Vandenabeele P, Vanden Berghe T. How do we fit ferroptosis in the family of regulated cell death? Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:1991–1998. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Badgley MA, Kremer DM, Maurer HC, DelGiorno KE, Lee HJ, Purohit V, Sagalovskiy IR, Ma A, Kapilian J, Firl CEM, et al. Cysteine depletion induces pancreatic tumor ferroptosis in mice. Science. 2020;368:85–89. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw9872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trachootham D, Alexandre J, Huang P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: A radical therapeutic approach? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrd2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altamura S, Marques O, Colucci S, Mertens C, Alikhanyan K, Muckenthaler MU. Regulation of iron homeostasis: Lessons from mouse models. Mol Aspects Med. 2020;75:100872. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2020.100872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koppenol WH, Hider RH. Iron and redox cycling. Do's and don'ts. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;133:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kajarabille N, Latunde-Dada GO. Programmed cell-death by ferroptosis: Antioxidants as mitigators. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4968. doi: 10.3390/ijms20194968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frazer DM, Anderson GJ. The regulation of iron transport. Biofactors. 2014;40:206–214. doi: 10.1002/biof.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El Hage Chahine JM, Hemadi M, Ha-Duong NT. Uptake and release of metal ions by transferrin and interaction with receptor 1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820:334–347. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohgami RS, Campagna DR, Greer EL, Antiochos B, McDonald A, Chen J, Sharp JJ, Fujiwara Y, Barker JE, Fleming MD. Identification of a ferrireductase required for efficient transferrin-dependent iron uptake in erythroid cells. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1264–1269. doi: 10.1038/ng1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kakhlon O, Cabantchik ZI. The labile iron pool: Characterization, measurement, and participation in cellular processes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)01006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Philpott CC, Ryu MS, Frey A, Patel S. Cytosolic iron chaperones: Proteins delivering iron cofactors in the cytosol of mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:12764–12771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R117.791962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris ZL, Durley AP, Man TK, Gitlin JD. Targeted gene disruption reveals an essential role for ceruloplasmin in cellular iron efflux. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10812–10817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang DL, Ghosh MC, Rouault TA. The physiological functions of iron regulatory proteins in iron homeostasis-an update. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:124. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dixon SJ, Stockwell BR. The role of iron and reactive oxygen species in cell death. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:9–17. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Recalcati S, Correnti M, Gammella E, Raggi C, Invernizzi P, Cairo G. Iron metabolism in liver cancer stem cells. Front Oncol. 2019;9:149. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng H, Schorpp K, Jin J, Yozwiak CE, Hoffstrom BG, Decker AM, Rajbhandari P, Stokes ME, Bender HG, Csuka JM, et al. Transferrin receptor is a specific ferroptosis marker. Cell Rep. 2020;30:3411–3423.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bai T, Lei P, Zhou H, Liang R, Zhu R, Wang W, Zhou L, Sun Y. Sigma-1 receptor protects against ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:7349–7359. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye F, Chai W, Xie M, Yang M, Yu Y, Cao L, Yang L. HMGB1 regulates erastin-induced ferroptosis via RAS-JNK/p38 signaling in HL-60/NRASQ61L cells. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:730–739. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turcu AL, Versini A, Khene N, Gaillet C, Cañeque T, Müller S, Rodriguez R. DMT1 inhibitors kill cancer stem cells by blocking lysosomal iron translocation. Chemistry. 2020;26:7369–7373. doi: 10.1002/chem.202000159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu H, Yang C, Jian L, Guo S, Chen R, Li K, Qu F, Tao K, Fu Y, Luo F, Liu S. Sulfasalazine-induced ferroptosis in breast cancer cells is reduced by the inhibitory effect of estrogen receptor on the transferrin receptor. Oncol Rep. 2019;42:826–838. doi: 10.3892/or.2019.7189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen GQ, Benthani FA, Wu J, Liang D, Bian ZX, Jiang X. Artemisinin compounds sensitize cancer cells to ferroptosis by regulating iron homeostasis. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:242–254. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0352-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Carvalho CCCR, Caramujo MJ. The various roles of fatty acids. Molecules. 2018;23:2583. doi: 10.3390/molecules23102583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dixon SJ, Winter GE, Musavi LS, Lee ED, Snijder B, Rebsamen M, Superti-Furga G, Stockwell BR. Human haploid cell genetics reveals roles for lipid metabolism genes in nonapoptotic cell death. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:1604–1609. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F, Angeli JP, Doll S, Croix CS, Dar HH, Liu B, Tyurin VA, Ritov VB, et al. Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:81–90. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng J, Lu PZ, Zhu GZ, Hooi SC, Wu Y, Huang XW, Dai HQ, Chen PH, Li ZJ, Su WJ, et al. ACSL4 is a predictive biomarker of sorafenib sensitivity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020 Jun 15; doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0439-x. (Epub ahead of print). doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0439-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng J, Fan YQ, Liu BH, Zhou H, Wang JM, Chen QX. ACSL4 suppresses glioma cells proliferation via activating ferroptosis. Oncol Rep. 2020;43:147–158. doi: 10.3892/or.2019.7419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richard D, Kefi K, Barbe U, Bausero P, Visioli F. Polyunsaturated fatty acids as antioxidants. Pharmacol Res. 2008;57:451–455. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lewerenz J, Hewett SJ, Huang Y, Lambros M, Gout PW, Kalivas PW, Massie A, Smolders I, Methner A, Pergande M, et al. The cystine/glutamate antiporter system x(c)(−) in health and disease: From molecular mechanisms to novel therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:522–555. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascón S, Hatzios SK, Kagan VE, et al. Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 2017;171:273–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dixon SJ, Patel DN, Welsch M, Skouta R, Lee ED, Hayano M, Thomas AG, Gleason CE, Tatonetti NP, Slusher BS, Stockwell BR. Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. Elife. 2014;3:e02523. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the light: The growing complexity of p53. Cell. 2009;137:413–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, Wang SJ, Su T, Hibshoosh H, Baer R, Gu W. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 2015;520:57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature14344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y, Zhuang L, Gan B. BAP1 suppresses tumor development by inducing ferroptosis upon SLC7A11 repression. Mol Cell Oncol. 2018;6:1536845. doi: 10.1080/23723556.2018.1536845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rojo de la Vega M, Chapman E, Zhang DD. NRF2 and the hallmarks of cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;34:21–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang WS, Stockwell BR. Synthetic lethal screening identifies compounds activating iron-dependent, nonapoptotic cell death in oncogenic-RAS-harboring cancer cells. Chem Biol. 2008;15:234–245. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, Cheah JH, Clemons PA, Shamji AF, Clish CB, et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156:317–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weiwer M, Bittker JA, Lewis TA, Shimada K, Yang WS, MacPherson L, Dandapani S, Palmer M, Stockwell BR, Schreiber SL, Munoz B. Development of small-molecule probes that selectively kill cells induced to express mutant RAS. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:1822–1826. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun X, Ou Z, Chen R, Niu X, Chen D, Kang R, Tang D. Activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway protects against ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology. 2016;63:173–184. doi: 10.1002/hep.28251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shaw AT, Winslow MM, Magendantz M, Ouyang C, Dowdle J, Subramanian A, Lewis TA, Maglathin RL, Tolliday N, Jacks T. Selective killing of K-ras mutant cancer cells by small molecule inducers of oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:8773–8778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105941108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Louandre C, Marcq I, Bouhlal H, Lachaier E, Godin C, Saidak Z, François C, Chatelain D, Debuysscher V, Barbare JC, et al. The retinoblastoma (Rb) protein regulates ferroptosis induced by sorafenib in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:971–977. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang K, Wu L, Zhang P, Luo M, Du J, Gao T, O'Connell D, Wang G, Wang H, Yang Y. miR-9 regulates ferroptosis by targeting glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase GOT1 in melanoma. Mol Carcinog. 2018;57:1566–1576. doi: 10.1002/mc.22878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang M, Mao C, Ouyang L, Liu Y, Lai W, Liu N, Shi Y, Chen L, Xiao D, Yu F, et al. Long noncoding RNA LINC00336 inhibits ferroptosis in lung cancer by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26:2329–2343. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0304-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luo M, Wu L, Zhang K, Wang H, Zhang T, Gutierrez L, O'Connell D, Zhang P, Li Y, Gao T, et al. miR-137 regulates ferroptosis by targeting glutamine transporter SLC1A5 in melanoma. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:1457–1472. doi: 10.1038/s41418-017-0053-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gomaa A, Peng D, Chen Z, Soutto M, Abouelezz K, Corvalan A, El-Rifai W. Epigenetic regulation of AURKA by miR-4715-3p in upper gastrointestinal cancers. Sci Rep. 2019;9:16970. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53174-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Niu Y, Zhang J, Tong Y, Li J, Liu B. Physcion 8-O-β-glucopyranoside induced ferroptosis via regulating miR-103a-3p/GLS2 axis in gastric cancer. Life Sci. 2019;237:116893. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tomita K, Fukumoto M, Itoh K, Kuwahara Y, Igarashi K, Nagasawa T, Suzuki M, Kurimasa A, Sato T. miR-7-5p is a key factor that controls radioresistance via intracellular Fe2+ content in clinically relevant radioresistant cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;518:712–718. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.08.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qin Z, Freitas E, Sullivan R, Mohan S, Bacelieri R, Branch D, Romano M, Kearney P, Oates J, Plaisance K, et al. Upregulation of xCT by KSHV-encoded microRNAs facilitates KSHV dissemination and persistence in an environment of oxidative stress. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000742. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiao FJ, Zhang D, Wu Y, Jia QH, Zhang L, Li YX, Yang YF, Wang H, Wu CT, Wang LS. miRNA-17-92 protects endothelial cells from erastin-induced ferroptosis through targeting the A20-ACSL4 axis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;515:448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.05.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bai T, Liang R, Zhu R, Wang W, Zhou L, Sun Y. MicroRNA-214-3p enhances erastin-induced ferroptosis by targeting ATF4 in hepatoma cells. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:5637–5648. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang HY, Zhang BW, Zhang ZB, Deng QJ. Circular RNA TTBK2 regulates cell proliferation, invasion and ferroptosis via miR-761/ITGB8 axis in glioma. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:2585–2600. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202003_20528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mao C, Wang X, Liu Y, Wang M, Yan B, Jiang Y, Shi Y, Shen Y, Liu X, Lai W, et al. A G3BP1-interacting lncRNA promotes ferroptosis and apoptosis in cancer via nuclear sequestration of p53. Cancer Res. 2018;78:3484–3496. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qi W, Li Z, Xia L, Dai J, Zhang Q, Wu C, Xu S. lncRNA GABPB1-AS1 and GABPB1 regulate oxidative stress during erastin-induced ferroptosis in HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Sci Rep. 2019;9:16185. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52837-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schaar DG, Medina DJ, Moore DF, Strair RK, Ting Y. miR-320 targets transferrin receptor 1 (CD71) and inhibits cell proliferation. Exp Hematol. 2009;37:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fu Y, Lin L, Xia L. miR-107 function as a tumor suppressor gene in colorectal cancer by targeting transferrin receptor 1. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2019;24:31. doi: 10.1186/s11658-019-0155-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Babu KR, Muckenthaler MU. miR-148a regulates expression of the transferrin receptor 1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1518. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35947-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Miyazawa M, Bogdan AR, Hashimoto K, Tsuji Y. Regulation of transferrin receptor-1 mRNA by the interplay between IRE-binding proteins and miR-7/miR-141 in the 3′-IRE stem-loops. RNA. 2018;24:468–479. doi: 10.1261/rna.063941.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kindrat I, Tryndyak V, de Conti A, Shpyleva S, Mudalige TK, Kobets T, Erstenyuk AM, Beland FA, Pogribny IP. MicroRNA-152-mediated dysregulation of hepatic transferrin receptor 1 in liver carcinogenesis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:1276–1287. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yoshioka Y, Kosaka N, Ochiya T, Kato T. Micromanaging iron homeostasis: Hypoxia-inducible micro-RNA-210 suppresses iron homeostasis-related proteins. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:34110–34119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.356717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu D, Liu D, Wang B, Chen C, Chen Z, Li D, Yang Y, Chen H, Kong MG. In Situ OH Generation from O2- and H2O2 plays a critical role in plasma-induced cell death. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chan JJ, Kwok ZH, Chew XH, Zhang B, Liu C, Soong TW, Yang H, Tay Y. A FTH1 gene:pseudogene: microRNA network regulates tumorigenesis in prostate cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:1998–2011. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Di bSanzo M, Chirillo R, Aversa I, Biamonte F, Santamaria G, Giovannone ED, Faniello MC, Cuda G, Costanzo F. shRNA targeting of ferritin heavy chain activates H19/miR-675 axis in K562 cells. Gene. 2018;657:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ripa R, Dolfi L, Terrigno M, Pandolfini L, Savino A, Arcucci V, Groth M, Terzibasi Tozzini E, Baumgart M, Cellerino A. MicroRNA miR-29 controls a compensatory response to limit neuronal iron accumulation during adult life and aging. BMC Biol. 2017;15:9. doi: 10.1186/s12915-017-0354-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang L, Ye Y, Tu H, Hildebrandt MA, Zhao L, Heymach JV, Roth JA, Wu X. MicroRNA-related genetic variants in iron regulatory genes, dietary iron intake, microRNAs and lung cancer risk. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1124–1129. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu F, Chen Y, Chen B, Liu C, Xing J. miR-935 promotes clear cell renal cell carcinoma migration and invasion by targeting IREB2. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:10891–10900. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S232380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 81.Andolfo I, De Falco L, Asci R, Russo R, Colucci S, Gorrese M, Zollo M, Iolascon A. Regulation of divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) non-IRE isoform by the microRNA Let-7d in erythroid cells. Haematologica. 2010;95:1244–1252. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.020685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jiang S, Guo S, Li H, Ni Y, Ma W, Zhao R. Identification and functional verification of MicroRNA-16 family targeting intestinal divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) in vitro and in vivo. Front Physiol. 2019;10:819. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Soupene E, Kuypers FA. Mammalian long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:507–521. doi: 10.3181/0710-MR-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yuan H, Li X, Zhang X, Kang R, Tang D. Identification of ACSL4 as a biomarker and contributor of ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;478:1338–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jiang X, Guo S, Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Li X, Jia Y, Xu Y, Ma B. lncRNA NEAT1 promotes docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer by regulating ACSL4 via sponging miR-34a-5p and miR-204-5p. Cell Signal. 2020;65:109422. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2019.109422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]