Abstract

Objectives

This study investigated whether commensality (eating a meal with others) is associated with mental health (depression, suicidal ideation) in Korean adults over 19 years old.

Methods

Our study employed data from the sixth and seventh Korea National Health and Nutritional Examination Surveys (KNHANES) for 2013, 2015, and 2017. The study population consisted of 14,125 Korean adults (5854 men and 8271 women). In this cross-sectional study, data were analyzed with the Rao-Scott chi-square test and multiple logistic regression to evaluate the association between commensality(0[includes skipping meals] to 3 times eating meals together) and both depression and suicidal ideation using select questions from the Mental Health Survey. By setting socioeconomic factors, health conditions, and behavioral factors as confounders, we conducted a subgroup analysis to reveal the effect on depression and suicidal ideation commensality.

Results

Commensality was significantly associated with depression and suicidal ideation (p < 0.05). In both sexes, people who ate fewer meals together had poorer mental health. In a subgroup analysis, we revealed greater odds of developing depression in men when living in rural areas and belonging to low-income groups. In contrast, greater odds of suicidal ideation in men who ate alone when living in the city and belonging to high-income groups. On the other hand, Women in every region had greater odds of being depressed if they ate alone. And greater odds of suicidal ideation in women who ate alone when living in the city and belonging to medium-high income groups.

Conclusions

Our analysis confirmed that Korean adults with lower chance of commensality had greater risk of developing depression and suicidal ideation. And it could be affected by individuals’ various backgrounds including socioeconomic status. As a result, to help people with depression and prevent a suicidal attempt, this study will be baseline research for social workers, educators and also policy developers to be aware of the importance of eating together.

Keywords: Commensality, Eating alone, Depression, Suicidal ideation, Living alone, Region

Highlights

Commensality was significantly associated with depression and suicidal ideation.

People who ate fewer meals together had poorer mental health.

Men had greater odds of depression when living in rural areas and having low-income

Women in every region had greater odds of being depressed if they ate alone

Introduction

Mental illness affects 10% of the world’s population in modern society. Approximately 350 million people suffer from depression globally [1]. The causes of depression are various, including physiological factors, social psychological factors, environmental variation, and role changes as a family member or worker [2]. Depression deteriorates quality of life while leading to social problems (e.g., loss of support network or employment), increasing suicide risk [3, 4]. Indeed, suicide is a major clinical symptom of depression, highly correlated with suicidal ideation, and considerable effort has been devoted to examining the link between suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts [5].

South Korea currently has the highest suicide rate in the world at 25.6 per 100,000 people, with depression prevalence at 5.0% (men 3.0%, women 5.9%) (Statistics Korea, 2016). Mental-health problems are likely linked to a rapidly changing society with various demands at different ages, including marriage, childbirth, child rearing, employment, and retirement [6, 7]. Stress from sociological factors such as generational differences also contribute to mental health. As a coping mechanism, people may alter their behaviors, including eating habits. More research is needed on behavioral responses to mental stressors as they are expected to become increasingly common [8].

Commensality, or the act of eating meals together, has become an important health issue because eating alone appears to be associated with poorer mental health outcomes [9–14]. Although traditional customs emphasized commensality [15], people in modern societies are increasingly eating alone for various reasons. In particular, some people who dine alone have reported that they associate commensality with negative feelings because they do not have the freedom to eat what they like and are uncomfortable eating in the presence of others [16]. However, eating alone can exclude an individual from many positive effects of communal eating, including socializing and disclosure [17, 18].

The percentage of single-person households in South Korea has increased rapidly from 4.2% in 1975 to 28.6% in 2017, and this rise is projected to continue. For many Koreans, this recent decrease in number of family members occurs concurrently with eating alone involuntarily, leading to loneliness and social isolation [19]. Increasingly, work-related or personal problems are also causing modern young people to move their homes without settling down. Such changes mean the lack of opportunities to share their lives, including meals, with family or other close social partners, affecting physical health, cognition, emotional state, and behavior [20–22]. Most Korean adults either skip breakfast or eat the meal away from home. Additionally, some of them involuntarily spend lunchtime and dinnertime alone; the lack of meal-related social activities narrows their relationships and appears to generate depressive feelings [23]. Other studies in Korea likewise found that people who ate lunch or dinner alone were more depressed than those who ate commensally; these associations even stronger when eating alone was involuntary (caused by external situations) [8, 9, 11, 24]. Therefore, in this study, we examined recent data from South Korea to determine whether the association between commensality and mental health differs among subgroups and is affected by socio-economic factors such as age, household size, geographic regions, and household income level. Our findings should have important implications for developing appropriate measures to address depression and suicide.

Materials and methods

Study population and data

This study was conducted using the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which aims to provide data for the development and evaluation of health policy. The survey produces statistics regarding smoking, drinking, physical activity, and obesity for the World Health Organization and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

The survey was performed across 192 regions. Participants were selected through two-stage stratified cluster sampling step by step with regions and households. This study only used the first (2013) and third (2015) years of the sixth KNHANES, as well as the second (2017) year of the seventh KNHANES. These were the only years that included questions on suicidal ideation, suicidal plans, and suicidal attempts. Data from the three surveys were pooled during analysis.

Data from 3697 out of 18,341 adults (8088 men, 10,353 women) were excluded due to missing values in the household, health, and mental health surveys. The missing values on diagnosed depression were also excluded (519 participants). Although independent variables, depression and suicidal ideation, could be already affected by whether or not they are diagnosed depression, adults with diagnosed depression were included (643 participants) not to rule out the possibility that the commensality could actually have resulted in clinical depression. The final dataset for this study included 14,125 adults over 19 years old (5854 men and 8271 women).

Measures

Outcome variables

Depression was assessed using one item on the mental health survey [25], “have you ever recently felt sad or desperate enough to experience negative effects in your everyday life for more than 2 weeks?”. Participants answered either “yes” or “no.” Based on these responses, they were categorized into two groups: (1) experienced depression, (2) did not experience depression.

Suicidal ideation was assessed instead of suicide directly owing to the difficulties of directly studying individuals who attempted or succeeded in suicide. Participants’ response to the question form the same survey, “have you ever seriously though of committing suicide within the last year?” was used to assess suicide ideation. Again, “yes” or “no” responses were used to categorized subjects into two groups: (1) experienced suicidal ideation, (2) did not experienced suicidal ideation. Since these data were obtained using a self-reported questionnaire and do not significantly represent clinical outcomes, those who were previously diagnosed with depression were not reclassified or treated differently.

Independent variable

Commensality was assessed using an item that asked whether participants ate each meal (breakfast, lunch, dinner) with family member or others within the past year. If a participant answered “yes” to “eating breakfast/lunch/dinner together,” then frequency of each meal was counted. The response “did not eat” (breakfast = 2918, lunch = 470, dinner = 291) was considered the same as “eating a meal alone,” because based on a previous study [26], we expected that skipping meals may also lead to lack of social exchange and elevate the risk of depression and suicidal ideation. Therefore, we re-classified eating habits into four groups: (1) eating no meal together, (2) eating one meal together, (3) eating two meals together, (4) eating all three meals together.

Covariates

The analysis examined a whole host of socioeconomic factors that could confound the relation between commensality and mental health, including gender, generation, household size, residential area, household income level, education level, and occupation. Chronic illness, smoking status, and drinking status were also included. Covariates were re-categorized based on previous research [12, 14, 20, 24, 26]: gender, generation age (20–29, 30–49, 50–64, ≥65), household size (alone, ≥1), residential area (metropolis [population over 1 million], city [population over 50,000], rural [population less than 50,000]), household income (low, medium-low, medium-high, high), completed education (≤elementary school, middle school, high school diploma, ≥bachelor’s degree), occupation (white collar, sales and services, blue collar, unemployed), presence of chronic illness (none, one, ≥2), smoking status (non-smoker, current smoker, past smoker), and drinking status (non-drinker, > 1 time per month, < 4 times per month, 2–3 times per week, ≥4 per week). Non-drinker group was analyzed as a reference, due to the nature of the questionnaires, to distinguish among non-drinker, drink less than once a month and drink once a month based on our previous study [27].

Statistical analysis

Multiple logistic regression was performed to quantify the strength of associations between commensality and mental health variables through odd ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and Rao-Scott chi-square tests. Individuals who ate three meals together were the reference category. We also conducted a subgroup analysis on depression and suicidal ideation among women and men separately to examine potential sex differences in the association with commensality. Marriage status as a variable with high multicollinearity (P ≥ 2) was excluded. All analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Of the study population, 2283 of 5854 men (39%) ate all three meals commensally, while 2724 of 8271 women (32.9%) had two meals commensally, as the highest percentage in their groups. Commensality was differentially associated with depression and suicidal ideation depending on socioeconomic or health characteristics (p < 0.05; Tables 1 and 2). Both mental health variables in men and women was significantly associated with household size, generation, household income, education, occupation, chronic illness, smoking status, and drinking status.

Table 1.

General Characteristics of commensality and depression

| N (%) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | ||||||||||||||

| Men | p-value | Women | p-value | |||||||||||

| Total | Yes | No | Total | Yes | No | |||||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | |||

| Commensality | ||||||||||||||

| Eating 3 meals together | 2283 | 39.0 | 172 | 31.7 | 2111 | 39.7 | <.0001 | 2437 | 29.5 | 311 | 25.1 | 2126 | 30.2 | <.0001 |

| Eating 2 meals together | 2062 | 35.2 | 158 | 29.2 | 1904 | 35.8 | 2724 | 32.9 | 350 | 28.2 | 2374 | 33.8 | ||

| Eating 1 meals together | 904 | 15.4 | 89 | 16.4 | 815 | 15.3 | 1863 | 22.5 | 300 | 24.2 | 1563 | 22.2 | ||

| Eating no meals together | 605 | 10.3 | 123 | 22.7 | 482 | 9.1 | 1247 | 15.1 | 280 | 22.6 | 967 | 13.8 | ||

| Household member | ||||||||||||||

| Alone | 584 | 10.0 | 115 | 21.2 | 469 | 8.8 | <.0001 | 1036 | 12.5 | 233 | 18.8 | 803 | 11.4 | <.0001 |

| > 1 | 5270 | 90.0 | 427 | 78.8 | 4843 | 91.2 | 7235 | 87.5 | 1008 | 81.2 | 6227 | 88.6 | ||

| Generation | ||||||||||||||

| 20–29 years old | 705 | 12.2 | 73 | 13.5 | 632 | 11.9 | <.0001 | 828 | 10.0 | 128 | 10.3 | 700 | 10.0 | <.0001 |

| 30–49 years old | 1843 | 31.9 | 112 | 20.7 | 1731 | 32.6 | 2922 | 35.3 | 318 | 25.6 | 2604 | 37.0 | ||

| 50–64 years old | 1695 | 29.3 | 173 | 31.9 | 1522 | 28.7 | 2401 | 29.0 | 386 | 31.1 | 2016 | 28.7 | ||

| ≥ 65 years old | 1610 | 27.8 | 184 | 33.9 | 1427 | 26.9 | 2119 | 25.6 | 409 | 33.0 | 1710 | 24.3 | ||

| Residential area | ||||||||||||||

| Metropolis | 2498 | 42.7 | 236 | 43.5 | 2262 | 42.6 | 0.8737 | 3648 | 44.1 | 524 | 42.2 | 3124 | 44.4 | 0.0005 |

| City | 2256 | 38.5 | 208 | 38.4 | 2048 | 38.6 | 3213 | 38.8 | 458 | 36.9 | 2755 | 39.2 | ||

| Rural area | 1100 | 18.8 | 98 | 18.1 | 1002 | 18.9 | 1410 | 17.0 | 259 | 20.9 | 1151 | 16.4 | ||

| Household Income | ||||||||||||||

| Low | 1105 | 19.1 | 186 | 34.3 | 919 | 17.3 | <.0001 | 1737 | 21.0 | 433 | 34.9 | 1304 | 18.5 | <.0001 |

| Medium-low | 1458 | 25.2 | 148 | 27.3 | 1310 | 24.7 | 2103 | 25.4 | 321 | 25.9 | 1782 | 25.3 | ||

| Medium-high | 1577 | 27.3 | 94 | 17.3 | 1483 | 27.9 | 2177 | 26.3 | 265 | 21.4 | 1912 | 27.2 | ||

| High | 1714 | 29.6 | 114 | 21.0 | 1600 | 30.1 | 2254 | 27.3 | 222 | 17.9 | 2032 | 28.9 | ||

| Educational Attainment | ||||||||||||||

| Elementary School | 1009 | 17.2 | 147 | 27.1 | 862 | 16.2 | <.0001 | 2321 | 28.1 | 503 | 40.5 | 1818 | 25.9 | <.0001 |

| Middle School | 648 | 11.1 | 70 | 12.9 | 578 | 10.9 | 843 | 10.2 | 146 | 11.8 | 697 | 9.9 | ||

| High School Diploma | 2020 | 34.5 | 191 | 35.2 | 1829 | 34.4 | 2483 | 30.0 | 340 | 27.4 | 2143 | 30.5 | ||

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 2177 | 37.2 | 134 | 24.7 | 2043 | 38.5 | 2624 | 31.7 | 252 | 20.3 | 2372 | 33.7 | ||

| Occupation | ||||||||||||||

| White Collar | 1523 | 26.0 | 73 | 13.5 | 1450 | 27.3 | <.0001 | 1660 | 20.1 | 145 | 11.7 | 1515 | 21.6 | <.0001 |

| Sales and Services | 1015 | 17.3 | 90 | 16.6 | 925 | 17.4 | 1427 | 17.3 | 221 | 17.8 | 1206 | 17.2 | ||

| Blue Collar | 1590 | 27.2 | 135 | 24.9 | 1455 | 27.4 | 1016 | 12.3 | 172 | 13.9 | 844 | 12.0 | ||

| Unemployed | 1726 | 29.5 | 244 | 45.0 | 1482 | 27.9 | 4168 | 50.4 | 703 | 56.6 | 3465 | 49.3 | ||

| Chronic Illnesses | ||||||||||||||

| None | 3767 | 64.3 | 286 | 52.8 | 3481 | 65.5 | <.0001 | 5171 | 62.5 | 655 | 52.8 | 4516 | 64.2 | <.0001 |

| 1 | 1180 | 20.2 | 137 | 25.3 | 1043 | 19.6 | 1519 | 18.4 | 261 | 21.0 | 1258 | 17.9 | ||

| 2 or more | 907 | 15.5 | 119 | 22.0 | 788 | 14.8 | 1581 | 19.1 | 325 | 26.2 | 1256 | 17.9 | ||

| Smoking | ||||||||||||||

| Current Smoker | 2013 | 34.4 | 210 | 38.7 | 1803 | 33.9 | 0.0444 | 384 | 4.6 | 110 | 8.9 | 274 | 3.9 | <.0001 |

| Past Smoker | 2518 | 43.0 | 227 | 41.9 | 2291 | 43.1 | 443 | 5.4 | 83 | 6.7 | 360 | 5.1 | ||

| Non-Smoker | 1323 | 22.6 | 105 | 19.4 | 1218 | 22.9 | 7444 | 91.1 | 1048 | 84.4 | 6396 | 91.0 | ||

| Drinking | ||||||||||||||

| Non-drinker | 290 | 5.0 | 44 | 8.1 | 246 | 4.6 | <.0001 | 1518 | 18.6 | 261 | 21.0 | 1257 | 17.9 | <.0001 |

| < 1 time per/month | 1440 | 24.6 | 149 | 27.5 | 1291 | 24.3 | 3493 | 42.8 | 517 | 41.7 | 2976 | 42.3 | ||

| < 4 times per/month | 2045 | 34.9 | 148 | 27.3 | 1897 | 35.7 | 2439 | 29.9 | 323 | 26.0 | 2116 | 30.1 | ||

| 2–3 times per week | 1373 | 23.5 | 112 | 20.7 | 1261 | 23.7 | 629 | 7.7 | 94 | 7.6 | 535 | 7.6 | ||

| ≥ 4 per week | 706 | 12.1 | 89 | 16.4 | 617 | 11.6 | 192 | 2.4 | 46 | 3.7 | 146 | 2.1 | ||

| Total | 5854 | 100.0 | 542 | 9.3 | 5312 | 90.7 | 8271 | 100.0 | 1241 | 15.0 | 7030 | 85.0 | ||

Table 2.

General Characteristics of commensality and suicidal ideation

| N (%) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal ideation | ||||||||||||||

| Men | p-value | Women | p-value | |||||||||||

| Total | Yes | No | Total | Yes | No | |||||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | |||

| Commensality | ||||||||||||||

| Eating 3 meals together | 2283 | 39.0 | 73 | 26.9 | 2210 | 39.6 | <.0001 | 2437 | 29.5 | 108 | 22.5 | 2329 | 29.9 | <.0001 |

| Eating 2 meals together | 2062 | 35.2 | 66 | 24.4 | 1996 | 35.8 | 2724 | 32.9 | 117 | 24.4 | 2607 | 33.5 | ||

| Eating 1 meals together | 904 | 15.4 | 53 | 19.6 | 851 | 15.2 | 1863 | 22.5 | 128 | 26.7 | 1735 | 22.3 | ||

| Eating no meals together | 605 | 10.3 | 79 | 29.2 | 526 | 9.4 | 1247 | 15.1 | 126 | 26.3 | 1121 | 14.4 | ||

| Household member | ||||||||||||||

| Alone | 584 | 10.0 | 75 | 27.7 | 509 | 9.1 | <.0001 | 1036 | 12.5 | 101 | 21.1 | 935 | 12.0 | <.0001 |

| > 1 | 5270 | 90.0 | 196 | 72.3 | 5074 | 90.9 | 7235 | 87.5 | 378 | 78.9 | 6857 | 88.0 | ||

| Generation | ||||||||||||||

| 20–29 years old | 705 | 12.2 | 26 | 9.6 | 679 | 12.2 | <.0001 | 828 | 10.0 | 46 | 9.6 | 782 | 10.0 | <.0001 |

| 30–49 years old | 1843 | 31.9 | 49 | 18.1 | 1794 | 32.1 | 2922 | 35.3 | 118 | 24.6 | 2804 | 36.0 | ||

| 50–64 years old | 1695 | 29.3 | 87 | 32.1 | 1608 | 28.8 | 2401 | 29.0 | 145 | 30.3 | 2257 | 29.0 | ||

| ≥ 65 years old | 1610 | 27.8 | 109 | 40.2 | 1502 | 26.9 | 2119 | 25.6 | 170 | 35.5 | 1949 | 25.0 | ||

| Residential area | ||||||||||||||

| Metropolis | 2498 | 42.7 | 114 | 42.1 | 2384 | 42.7 | 0.7140 | 3648 | 44.1 | 197 | 41.1 | 3451 | 44.3 | 0.0269 |

| City | 2256 | 38.5 | 101 | 37.3 | 2155 | 38.6 | 3213 | 38.8 | 179 | 37.4 | 3034 | 38.9 | ||

| Rural area | 1100 | 18.8 | 56 | 20.7 | 1044 | 18.7 | 1410 | 17.0 | 103 | 21.5 | 1307 | 16.8 | ||

| Household Income | ||||||||||||||

| Low | 1105 | 19.1 | 125 | 46.1 | 980 | 17.6 | <.0001 | 1737 | 21.0 | 185 | 38.6 | 1552 | 19.9 | <.0001 |

| Medium-low | 1458 | 25.2 | 67 | 24.7 | 1391 | 24.9 | 2103 | 25.4 | 133 | 27.8 | 1970 | 25.3 | ||

| Medium-high | 1577 | 27.3 | 34 | 12.5 | 1543 | 27.6 | 2177 | 26.3 | 90 | 18.8 | 2087 | 26.8 | ||

| High | 1714 | 29.6 | 45 | 16.6 | 1669 | 29.9 | 2254 | 27.3 | 71 | 14.8 | 2183 | 28.0 | ||

| Educational Attainment | ||||||||||||||

| Elementary School | 1009 | 17.2 | 86 | 31.7 | 923 | 16.5 | <.0001 | 2321 | 28.4 | 215 | 44.9 | 2106 | 27.0 | <.0001 |

| Middle School | 648 | 11.1 | 49 | 18.1 | 599 | 10.7 | 843 | 10.3 | 46 | 9.6 | 797 | 10.2 | ||

| High School Diploma | 2020 | 34.5 | 86 | 31.7 | 1934 | 34.6 | 2483 | 30.4 | 144 | 30.1 | 2339 | 30.0 | ||

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 2177 | 37.2 | 50 | 18.5 | 2127 | 38.1 | 2624 | 32.1 | 74 | 15.4 | 2550 | 32.7 | ||

| Occupation | ||||||||||||||

| White Collar | 1523 | 26.0 | 30 | 11.1 | 1493 | 26.7 | <.0001 | 1660 | 20.1 | 51 | 10.6 | 1609 | 20.6 | <.0001 |

| Sales and Services | 1015 | 17.3 | 32 | 11.8 | 983 | 17.6 | 1427 | 17.3 | 84 | 17.5 | 1343 | 17.2 | ||

| Blue Collar | 1590 | 27.2 | 65 | 24.0 | 1525 | 27.3 | 1016 | 12.3 | 58 | 12.1 | 958 | 12.3 | ||

| Unemployed | 1726 | 29.5 | 144 | 53.1 | 1582 | 28.3 | 4168 | 50.4 | 286 | 59.7 | 3882 | 49.8 | ||

| Chronic Illnesses | ||||||||||||||

| None | 3767 | 64.3 | 128 | 47.2 | 3639 | 65.2 | <.0001 | 5171 | 62.5 | 237 | 49.5 | 4934 | 63.3 | <.0001 |

| 1 | 1180 | 20.2 | 78 | 28.8 | 1102 | 19.7 | 1519 | 18.4 | 112 | 23.4 | 1407 | 18.1 | ||

| 2 or more | 907 | 15.5 | 65 | 24.0 | 842 | 15.1 | 1581 | 19.1 | 130 | 27.1 | 1451 | 18.6 | ||

| Smoking | ||||||||||||||

| Current Smoker | 2013 | 34.4 | 114 | 42.1 | 1899 | 34.0 | 0.0049 | 384 | 4.6 | 60 | 12.5 | 324 | 4.2 | <.0001 |

| Past Smoker | 2518 | 43.0 | 114 | 42.1 | 2404 | 43.1 | 443 | 5.4 | 41 | 8.6 | 402 | 5.2 | ||

| Non-Smoker | 1323 | 22.6 | 43 | 15.9 | 1280 | 22.9 | 7444 | 91.1 | 378 | 78.9 | 7066 | 90.7 | ||

| Drinking | ||||||||||||||

| Non-drinker | 290 | 5.0 | 20 | 7.4 | 270 | 4.8 | <.0001 | 1518 | 18.6 | 101 | 21.1 | 1417 | 18.2 | <.0001 |

| < 1 time per/month | 1440 | 24.6 | 91 | 33.6 | 1349 | 24.2 | 3493 | 42.8 | 199 | 41.5 | 3294 | 42.3 | ||

| < 4 times per/month | 2045 | 34.9 | 68 | 25.1 | 1977 | 35.4 | 2439 | 29.9 | 115 | 24.0 | 2324 | 29.8 | ||

| 2–3 times per week | 1373 | 23.5 | 39 | 14.4 | 1334 | 23.9 | 629 | 7.7 | 37 | 7.7 | 592 | 7.6 | ||

| ≥ 4 per week | 706 | 12.1 | 53 | 19.6 | 653 | 11.7 | 192 | 2.4 | 27 | 5.6 | 165 | 2.1 | ||

| Total | 5854 | 271 | 4.6 | 5583 | 95.4 | 8271 | 479 | 5.8 | 7792 | 94.2 | ||||

Associations between commensality and depression

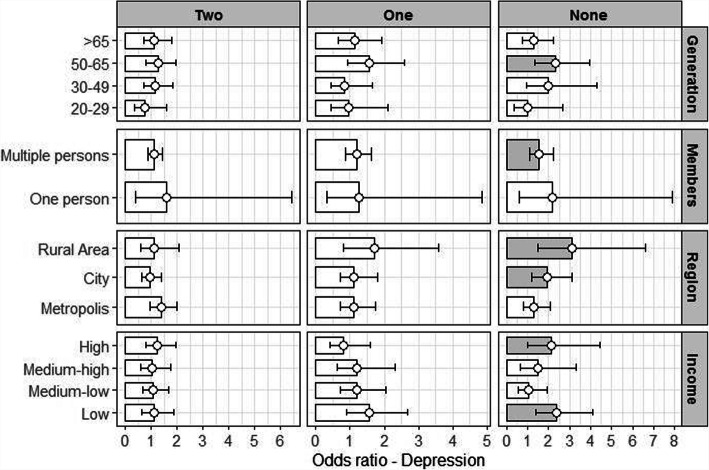

Relative to those who had all three meals together, men who ate every meal alone were up to 1.72 times (OR: 1.72, 95% CI: 1.27–2.34) more likely to be depressed, while women who ate alone were 1.58 times (OR: 1.58, 95% CI: 1.28–1.95) more likely to be depressed. There was a weaker association between depression and commensality among the ≥65 years old category than the 20–29 year old category (reference group) for both men (OR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.37–0.80) and women (OR: 0.49, 95% CI: 0.35–0.68). Men who lived with others had a significantly greater association between commensality and depression (OR: 1.65, 95% CI: 0.37–0.80) than those who lived alone (Table 3). The result of associations between commensality and depression was shown in Fig. 1.

Table 3.

Association between commensality and general characteristics of depression

| Depression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 5854) |

Women (n-8271) |

|||

| Odds Ratio | 95% CIa | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

| Commensalityb | ||||

| Eating 3 meals together | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Eating 2 meals together | 1.15 | (0.90–1.46) | 1.15 | (0.97–1.36) |

| Eating 1 meals together | 1.17 | (0.87–1.56) | 1.36 | (1.13–1.63) |

| Eating no meals together | 1.72 | (1.27–2.34) | 1.58 | (1.28–1.95) |

| Household member | ||||

| Alone | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| > 1 | 1.61 | (1.22–2.14) | 0.90 | (0.73–1.01) |

| Generation | ||||

| 20–29 years old | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| 30–49 years old | 0.72 | (0.59–1.01) | 0.66 | (0.52–0.83) |

| 50–64 years old | 0.80 | (0.55–1.15) | 0.70 | (0.53–0.91) |

| ≥ 65 years old | 0.54 | (0.37–0.80) | 0.49 | (0.35–0.68) |

| Residential area | ||||

| Metropolis | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| City | 0.97 | (0.79–1.19) | 0.99 | (0.86–1.14) |

| Rural area | 0.82 | (0.63–1.07) | 1.17 | (0.98–1.39) |

| Household Income | ||||

| Low | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Medium-low | 0.80 | (0.61–1.03) | 0.62 | (0.52–0.74) |

| Medium-high | 0.51 | (0.37–0.69) | 0.53 | (0.44–0.65) |

| High | 0.63 | (0.47–0.85) | 0.48 | (0.38–0.59) |

| Educational Attainment | ||||

| Elementary School | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Middle School | 0.85 | (0.62–1.17) | 0.85 | (0.68–1.07) |

| High School Diploma | 0.82 | (0.62–1.10) | 0.69 | (0.56–0.85) |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 0.70 | (0.50–0.98) | 0.56 | (0.42–0.71) |

| Occupation | ||||

| White Collar | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Sales and Services | 1.49 | (1.05–2.13) | 1.23 | (0.96–1.58) |

| Blue Collar | 1.34 | (0.95–1.89) | 1.29 | (0.98–1.69) |

| Unemployed | 1.92 | (1.37–2.69) | 1.36 | (1.10–1.69) |

| Chronic Illnesses | ||||

| None | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| 1 | 1.38 | (1.08–1.78) | 1.10 | (0.91–1.33) |

| 2 or more | 1.43 | (1.10–1.87) | 1.26 | (1.04–1.53) |

| Smoking | ||||

| Non-smoker | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Current smoker | 1.24 | (0.95–1.62) | 2.15 | (1.67–2.76) |

| Past smoker | 1.06 | (0.81–1.38) | 1.30 | (1.00–1.69) |

| Drinking | ||||

| Non-drinker | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| < 1 time per/month | 0.70 | (0.48–1.02) | 1.02 | (0.86–1.22) |

| < 4 times per/month | 0.58 | (0.39–0.84) | 0.99 | (0.81–1.20) |

| 2–3 times per week | 0.63 | (0.42–0.93) | 1.06 | (0.80–1.40) |

| ≥ 4 per week | 0.83 | (0.55–1.25) | 1.43 | (0.96–2.13) |

aCI Confidence Interval

bCommensality is analyzed by Controlled variables includes household members, generation, Residential area, household income, educational attainment, occupation, chronic illnesses, smoking, drinking

Fig. 1.

Commensality and depression: generation, household members, region, household income

Associations between commensality and suicidal ideation

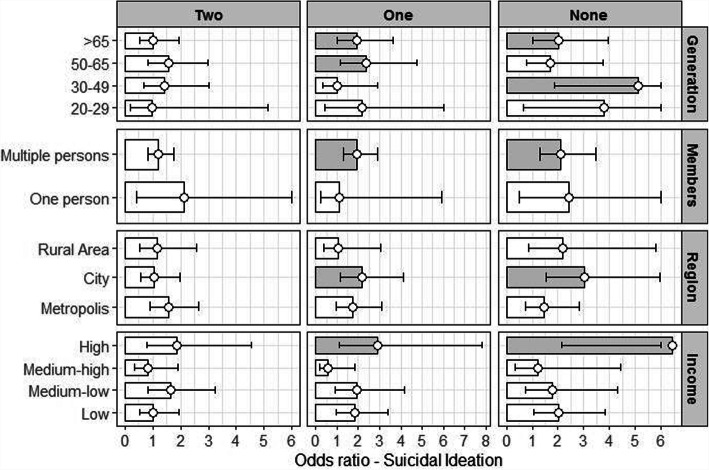

Men eating one meal together (OR: 1.77, 95% CI: 1.19–2.62), men eating all meals alone (OR: 2.16, 95% CI: 1.41–3.30), women eating one meal together (OR 1.64, 95% CI: 1.24–2.17), and women eating all meals alone (OR: 1.94, 95% CI: 1.41–2.67) were all highly associated with suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation in men who lived with others (household size > 1) was also more likely to be associated with commensality than those who lived alone (OR: 1.61, 95% CI: 1.10–2.37). Women in the 20–29 age group experienced a stronger association between suicidal ideation and commensality than other generations. In addition, this association was stronger among women who lived in rural regions (OR 1.02, 95% CI: 0.82–1.26) or cities (OR 1.18, 95% CI: 0.90–1.54) compared with those living in metropolitan areas, although the difference was not significant (Table 4). The result of associations between commensality and suicidal ideation was shown in Fig. 2.

Table 4.

Association between commensality and general characteristics of suicidal ideation

| Suicidal ideation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 5854) |

Women (n = 8271) |

|||

| Odds Ratio | 95% CIa | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

| Commensalityb | ||||

| Eating 3 meals together | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Eating 2 meals together | 1.28 | (0.90–1.82) | 1.09 | (0.82–1.45) |

| Eating 1 meals together | 1.77 | (1.19–2.62) | 1.64 | (1.24–2.17) |

| Eating no meals together | 2.16 | (1.41–3.30) | 1.94 | (1.41–2.67) |

| Household member | ||||

| Alone | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| > 1 | 1.61 | (1.10–2.37) | 0.81 | (0.59–1.12) |

| Generation | ||||

| 20–29 years old | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| 30–49 years old | 1.03 | (0.60–1.76) | 0.74 | (0.52–1.06) |

| 50–64 years old | 1.04 | (0.59–1.83) | 0.74 | (0.48–1.14) |

| ≥ 65 years old | 0.78 | (0.44–1.37) | 0.52 | (0.31–0.88) |

| Residential area | ||||

| Metropolis | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| City | 0.99 | (0.74–1.32) | 1.02 | (0.82–1.26) |

| Rural area | 1.03 | (0.72–1.46) | 1.18 | (0.90–1.54) |

| Household Income | ||||

| Low | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Medium-low | 0.59 | (0.42–0.83) | 0.68 | (0.52–0.90) |

| Medium-high | 0.33 | (0.22–0.51) | 0.49 | (0.36–0.66) |

| High | 0.47 | (0.31–0.72) | 0.44 | (0.31–0.62) |

| Educational Attainment | ||||

| Elementary School | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Middle School | 1.22 | (0.82–1.81) | 0.64 | (0.45–0.91) |

| High School Diploma | 0.82 | (0.56–1.20) | 0.74 | (0.52–1.03) |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 0.58 | (0.36–0.94) | 0.41 | (0.26–0.63) |

| Occupation | ||||

| White Collar | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Sales and Services | 0.90 | (0.53–1.55) | 1.04 | (0.70–1.55) |

| Blue Collar | 1.13 | (0.69–1.84) | 0.91 | (0.59–1.40) |

| Unemployed | 1.77 | (1.09–2.85) | 1.21 | (0.86–1.71) |

| Chronic Illnesses | ||||

| None | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| 1 | 1.47 | (1.04–2.06) | 1.26 | (0.95–1.67) |

| 2 or more | 1.34 | (0.93–1.92) | 1.27 | (0.94–1.72) |

| Smoking | ||||

| Non-smoker | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Current smoker | 1.50 | (1.01–2.22) | 2.85 | (2.05–3.97) |

| Past smoker | 1.10 | (0.75–1.63) | 1.70 | (1.19–2.44) |

| Drinking | ||||

| Non-drinker | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| < 1 time per/month | 1.08 | (0.65–1.79) | 1.04 | (0.80–1.36) |

| < 4 times per/month | 0.77 | (0.45–1.31) | 0.95 | (0.70–1.29) |

| 2–3 times per week | 0.58 | (0.33–1.02) | 1.04 | (0.67–1.63) |

| ≥ 4 per week | 1.22 | (0.70–2.13) | 1.98 | (1.19–3.30) |

aCI Confidence Interval

l

bCommensality is analyzed by Controlled variables includes household members, generation, Residential area, household income, educational attainment, occupation, chronic illnesses, smoking, drinking

Fig. 2.

Commensality and suicidal ideation: generation, household members, region, household income

Subgroup of depression and suicidal ideation among men

Subgroup analysis showed that in men of the 50–64 age group, depression was significantly associated with eating all meals alone (OR: 2.32, 95% CI: 1.35–3.97). Looking within multi-person households, depression was significantly associated with eating alone (OR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.08–2.24). Within residential area, eating fewer meals together meant being 1.92 times more likely to be depressed when living in cities (OR:1.92, 95% CI 1.18–3.12) and 3.11 times more likely in rural areas (OR: 3.11, 95% CI: 1.47–6.60). Similarly, suicidal ideation was significantly associated with eating fewer meals together among men. Within generations, the 30–49 age group had the highest association between eating all meals alone and suicidal ideation (OR: 5.11, 95% CI: 1.87–14.00). Those who lived in cities were more likely to have an association between eating no meals commensally and suicidal ideation (OR: 3.10, 95% CI: 1.53–5.94). Men in the high-income group were significantly more likely to have suicidal ideation if they ate only one meal together (OR: 2.92, 95% CI: 1.09–7.82) or ate all meals alone (OR: 6.45, 95% CI: 2.15–19.33) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Association between commensality and depression and suicidal ideation in subgroups: Men

| Depression (n = 542) | Commensality (Number of meals together)b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case(n) | 3(n = 172) | 2(n = 158) | 1(n = 89) | None(n = 123) | ||||

| Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | 95% CIa | Odds Ratio | 95% CIa | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | ||

| Generation | ||||||||

| 20–29 years old | 71 | 1.00 | 0.77 | (0.37–1.60) | 0.96 | (0.44–2.09) | 0.99 | (0.37–2.65) |

| 30–49 years old | 112 | 1.00 | 1.14 | (0.71–1.82) | 0.84 | (0.43–1.65) | 2.00 | (0.93–4.30) |

| 50–64 years old | 173 | 1.00 | 1.26 | (0.81–1.94) | 1.56 | (0.94–2.59) | 2.32 | (1.35–3.97) |

| ≥ 65 years old | 184 | 1.00 | 1.13 | (0.71–1.79) | 1.13 | (0.66–1.92) | 1.29 | (0.74–2.25) |

| Household members | ||||||||

| One person | 115 | 1.00 | 1.59 | (0.39–6.43) | 1.25 | (0.32–4.86) | 2.17 | (0.60–7.90) |

| Multiple persons(≥1) | 427 | 1.00 | 1.12 | (0.88–1.43) | 1.20 | (0.88–1.62) | 1.55 | (1.08–2.24) |

| Region | ||||||||

| Metropolis | 236 | 1.00 | 1.40 | (0.97–2.01) | 1.12 | (0.73–1.73) | 1.28 | (0.79–2.06) |

| City | 208 | 1.00 | 0.94 | (0.64–1.38) | 1.12 | (0.71–1.79) | 1.92 | (1.18–3.12) |

| Rural area | 98 | 1.00 | 1.13 | (0.61–2.09) | 1.71 | (0.81–3.57) | 3.11 | (1.47–6.60) |

| Household Income | ||||||||

| Low | 186 | 1.00 | 1.10 | (0.65–1.86) | 1.56 | (0.90–2.69) | 2.39 | (1.40–4.10) |

| Medium-low | 148 | 1.00 | 1.07 | (0.68–1.67) | 1.21 | (0.72–2.03) | 1.03 | (0.55–1.93) |

| Medium-high | 94 | 1.00 | 1.04 | (0.61–1.77) | 1.20 | (0.63–2.31) | 1.49 | (0.67–3.32) |

| High | 114 | 1.00 | 1.24 | (0.78–1.97) | 0.81 | (0.41–1.59) | 2.14 | (1.02–4.46) |

| Suicidal ideation (n = 271) | Case(n) | 3(n = 77) | 2(n = 66) | 1(n = 53) | None(n = 79) | |||

| Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | 95% CIa | Odds Ratio | 95% CIa | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | ||

| Generation | ||||||||

| 20–29 years old | 26 | 1.00 | 0.97 | (0.18–5.14) | 2.16 | (0.43–10.96) | 3.77 | (0.65–21.89) |

| 30–49 years old | 49 | 1.00 | 1.41 | (0.65–3.03) | 1.00 | (0.34–2.92) | 5.11 | (1.87–14.00) |

| 50–64 years old | 87 | 1.00 | 1.56 | (0.82–2.99) | 2.37 | (1.17–4.75) | 1.71 | (0.77–3.75) |

| ≥ 65 years old | 109 | 1.00 | 1.01 | (0.52–1.95) | 1.92 | (1.02–3.61) | 2.01 | (1.02–3.95) |

| Household members | ||||||||

| One person | 75 | 1.00 | 2.14 | (0.40–11.46) | 1.11 | (0.21–5.92) | 2.43 | (0.51–11.53) |

| Multiple persons(≥1) | 196 | 1.00 | 1.19 | (0.81–1.74) | 1.94 | (1.28–2.92) | 2.11 | (1.29–3.46) |

| Region | ||||||||

| Metropolis | 115 | 1.00 | 1.55 | (0.91–2.66) | 1.72 | (0.95–3.09) | 1.44 | (0.73–2.82) |

| City | 101 | 1.00 | 1.04 | (0.55–1.96) | 2.15 | (1.13–4.11) | 3.01 | (1.53–5.94) |

| Rural area | 56 | 1.00 | 1.15 | (0.51–2.57) | 1.03 | (0.35–3.05) | 2.20 | (0.84–5.79) |

| Household Income | ||||||||

| Low | 125 | 1.00 | 0.99 | (0.51–1.92) | 1.83 | (0.98–3.40) | 2.02 | (1.07–3.83) |

| Medium-low | 67 | 1.00 | 1.65 | (0.83–3.25) | 1.95 | (0.92–4.15) | 1.78 | (0.74–4.29) |

| Medium-high | 34 | 1.00 | 0.81 | (0.35–1.91) | 0.58 | (0.18–1.83) | 1.23 | (0.34–4.41) |

| High | 45 | 1.00 | 1.87 | (0.77–4.53) | 2.92 | (1.09–7.82) | 6.45 | (2.15–19.33) |

aCI Confidence Interval

cCommensality is analyzed by Controlled variables includes household members, generation, Residential area, household income, educational attainment, occupation, chronic illnesses, smoking, drinking, except each subgroup variable

Subgroup of depression and suicidal ideation among women

Women who were ≥ 65 years old were 1.72 times more likely to have depression if they only ate one meal commensally (OR: 1.72, 95% CI: 1.21–2.45) and 3.04 times more likely if they ate alone (OR: 2.04, 95% CI: 1.44–2.89). Similar to men, women who lived in multi-person households were 1.38 times more likely to have depression if they ate one meal together (OR: 1.38, 95% CI: 1.14–1.67) and 1.56 times more likely if they ate entirely alone (OR: 1.56, 95% CI: 1.23–1.99). Women in every region had greater odds of being depressed if they ate alone (metropolitan area, OR: 1.70, 95% CI: 1.23–2.34; city, OR: 1.73, 95% CI: 1.22–2.46; rural area, OR: 1.21, 95% CI: 0.73–2.01). Among medium-high income women, eating two meals together (OR: 1.76, 95% CI: 1.22–2.55), eating one meal together (OR: 2.02, 95% CI: 1.37–2.97), eating no meals together (OR: 2.04, 95% CI: 1.24–3.35) all increased the odds of being depressed (Table 6).

Table 6.

Association between commensality and depression and suicidal ideation in subgroups: Women

| Depression (n = 1241) | Case(n) | Commensality (Number of meals together)b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3(n = 311) | 2(n = 350) | 1(n = 300) | None(n = 280) | |||||

| Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | 95% CIa | Odds Ratio | 95% CIa | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | ||

| Generation | ||||||||

| 20–29 years old | 128 | 1.00 | 0.95 | (0.54–1.66) | 1.21 | (0.68–2.17) | 1.15 | (0.54–2.44) |

| 30–49 years old | 318 | 1.00 | 1.18 | (0.86–1.62) | 1.39 | (0.98–1.96) | 1.70 | (1.03–2.80) |

| 50–64 years old | 386 | 1.00 | 1.19 | (0.89–1.60) | 1.21 | (0.88–1.67) | 1.36 | (0.93–2.00) |

| ≥ 65 years old | 409 | 1.00 | 1.16 | (0.81–1.66) | 1.72 | (1.21–2.45) | 2.04 | (1.44–2.89) |

| Household members | ||||||||

| One person | 233 | 1.00 | 1.59 | (0.47–5.37) | 1.87 | (0.61–5.75) | 2.37 | (0.79–7.16) |

| Multiple persons(≥1) | 1008 | 1.00 | 1.15 | (0.97–1.38) | 1.38 | (1.14–1.67) | 1.56 | (1.23–1.99) |

| Region | ||||||||

| Metropolis | 524 | 1.00 | 1.26 | (0.96–1.63) | 1.25 | (0.94–1.66) | 1.70 | (1.23–2.34) |

| City | 458 | 1.00 | 1.13 | (0.84–1.50) | 1.53 | (1.14–2.06) | 1.73 | (1.22–2.46) |

| Rural area | 259 | 1.00 | 1.00 | (0.68–1.47) | 1.35 | (0.88–2.06) | 1.21 | (0.73–2.01) |

| Household Income | ||||||||

| Low | 433 | 1.00 | 1.13 | (0.79–1.61) | 1.32 | (0.91–1.90) | 1.87 | (1.30–2.70) |

| Medium-low | 321 | 1.00 | 1.08 | (0.78–1.48) | 1.32 | (0.87–1.98) | 1.32 | (0.87–1.98) |

| Medium-high | 265 | 1.00 | 1.76 | (1.22–2.55) | 2.02 | (1.37–2.97) | 2.04 | (1.24–3.35) |

| High | 222 | 1.00 | 0.77 | (0.54–1.11) | 1.18 | (0.80–1.74) | 1.00 | (0.56–1.78) |

| Suicidal ideation (n = 479) | Case(n) | 3(n = 108) | 2(n = 117) | 1(n = 128) | None(n = 126) | |||

| Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | 95% CIa | Odds Ratio | 95% CIa | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | ||

| Generation | ||||||||

| 20–29 years old | 46 | 1.00 | 1.57 | (0.51–4.83) | 4.22 | (1.40–12.68) | 4.24 | (1.20–14.94) |

| 30–49 years old | 118 | 1.00 | 1.06 | (0.62–1.81) | 1.98 | (1.15–3.40) | 2.03 | (0.94–4.37) |

| 50–64 years old | 145 | 1.00 | 0.94 | (0.59–1.51) | 0.98 | (0.59–1.64) | 1.49 | (0.85–2.61) |

| ≥ 65 years old | 170 | 1.00 | 1.48 | (0.88–2.49) | 2.05 | (1.22–3.44) | 2.36 | (1.43–3.92) |

| Household members | ||||||||

| One person | 101 | 1.00 | 0.68 | (0.11–4.11) | 1.51 | (0.33–7.04) | 1.63 | (0.36–7.42) |

| Multiple persons(≥1) | 378 | 1.00 | 1.15 | (0.87–1.53) | 1.67 | (1.24–2.24) | 2.10 | (1.48–2.96) |

| Region | ||||||||

| Metropolis | 197 | 1.00 | 1.08 | (0.70–1.66) | 1.39 | (0.89–2.16) | 1.80 | (1.10–2.94) |

| City | 179 | 1.00 | 1.31 | (0.81–2.12) | 1.98 | (1.24–3.18) | 2.43 | (1.44–4.11) |

| Rural area | 103 | 1.00 | 0.86 | (0.47–1.59) | 2.07 | (1.14–3.76) | 1.82 | (0.90–3.72) |

| Household Income | ||||||||

| Low | 185 | 1.00 | 1.00 | (0.60–1.67) | 1.49 | (0.90–2.47) | 1.55 | (0.92–2.60) |

| Medium-low | 133 | 1.00 | 1.16 | (0.70–1.91) | 1.42 | (0.84–2.40) | 1.87 | (1.04–3.36) |

| Medium-high | 90 | 1.00 | 2.02 | (1.02–4.01) | 3.21 | (1.63–6.32) | 3.04 | (1.34–6.91) |

| High | 71 | 1.00 | 0.66 | (0.35–1.25) | 1.19 | (0.62–2.28) | 2.06 | (0.94–4.48) |

aCI Confidence Interval

l

cCommensality is analyzed by Controlled variables includes household members, generation, Residential area, household income, educational attainment, occupation, chronic illnesses, smoking, drinking, except each subgroup variable

Women in the 20–29 age group were 4.22 times more likely to have suicidal ideation if they ate only one meal commensally (OR: 4.22, 95% CI: 1.40–12.68) and 4.24 times more likely if they ate all meals alone (OR: 4.24, 95% CI: 1.20–14.94). Women 65 years or older were 2.05 times more likely to have suicidal ideation if they ate one meal together (OR: 2.05, 95% CI: 1.22–3.44) and 2.36 times more likely if they ate alone (OR: 2.36, 95% CI: 1.43–3.92). Women who lived in cities were more likely to have suicidal ideation if they ate fewer meals commensally (one meal together, OR: 1.98, 95% CI: 1.24–3.18; no meals together, OR: 2.43, 95% CI: 1.44–4.11). Finally, women making medium-high incomes had significantly greater odds of suicidal ideation if they ate fewer meals commensally, whether that was two meals (OR: 2.02, 95% CI: 1.02–4.01), one meal (OR: 3.21, 95% CI: 1.63–6.32), or no meal together (OR: 3.04, 95% CI: 1.34–3.6.91)(Table 6).

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of commensality for social interactions and intimate relationships [28]. Specifically, eating alone, without the benefits of commensality such as socializing and disclosure, was related to a greater likelihood of depression and suicidal ideation [29, 30]. Depression and suicidal ideation were analyzed together, because the former is highly correlated with suicidality (including suicidal ideation, suicidal plans, and suicidal attempts) [9, 30]. Our study focused on the benefits of commensality for promoting mental health. Numerous studies have linked not only physical health but also mental health to self-destructive behaviors such as suicide, suggesting the need to prevent these behaviors through an integrated approach [30–32]. We added to the existing literature by analyzing the strength of the relationship between commensality and mental health for various subgroups, using detailed socio-economic data on Korean adults.

The results showed that both men and women who ate meals less frequently with others were more likely to be depressed. This result differs from that of previous studies, in which commensality had a strong association with depression only among men [33]. Also, we found that commensality was significantly associated with depression and suicidal ideation for the 20–29 year old age group, in contrast with previous studies that only found these associations among older adults [24, 34–36]. For early adults, commensality provides emotional stability and positively affects mental health [6, 7]. Increased pressure in the academic, marriage, and employment realms has forced young adults to delay getting married and live alone for a longer period, which causes them to have individualistic values and decreases their social exchanges with others [37].

This study also demonstrated that lower socio-economic levels [24, 35, 38, 39], including lower income levels and education attainment, and poorer physical health, such as the present of a chronic disease [40] or smoking [14], have a higher association between eating alone and depression and suicidal ideation.

Similar to research that found that commensality with family members has a positive effect on mental health [24, 33], this study also found that people in multi-person households who ate meals alone were more likely to be depressed and have suicidal ideation. Owing to the small sample size and the fact that the proportion of single-person households was only 10%, the relationship between commensality and mental health was insignificant among single-person households. Because the population of single-person households is increasing in Korea [41], further research is needed to explore the effect of eating alone for those who live alone.

Because many unmarried and young men have moved to cities and bereaved and old women have stayed in rural communities in Korea, there are residential and cultural differences in mental health. Prior research has shown that those living in rural areas with low income levels tended to have increased levels of depression [42]. This study found that men are more likely to be depressed if they are living in a smaller population area in a rural area, followed by cities and metropolises. Moreover, the odds of suicidal ideation was higher in cities, followed by rural areas and metropolises. Women were, on the other hand, more likely to be depressed and higher suicidal ideation in cities unlike previous studies showed that women in rural areas were significantly more depressed [37, 42].

A major limitation of this study is its cross-sectional nature. The lack of longitudinal data meant we cannot comment on the causality of commensality; we do not know if eating together directly improved mental health, or if depression and suicidal ideation conversely caused participants to seek out company at mealtimes. In particular, we did not exclude or reclassify individuals who were previously diagnosed with depression, because we could not determine whether depression influences the likelihood of commensality or vice versa. We also did not account for the possibility that individuals may want to eat alone, and that such a choice may be positive depending on their own preferences and health. Given the wide range of factors affecting dietary changes in modern society, future studies should carefully separate the various causes of diet-related behaviors to clarify any links between commensality and mental health. And almost 20% participants in the datasets were excluded as missing values, non-specified or no answers in the self-reported health survey, particularly about diagnosis of depression. Considering the possibility of losing those with depression did not desire to answer, the results should be carefully interpreted.

Nevertheless, our study has important strengths. We considered important covariates (e.g., socioeconomic factors, chronic conditions) in our analysis of commensality, identifying statistically significant associations between eating habits and mental health that differed depending on household size and residence type (urban vs. rural). Notably, we were able to compare adults living alone but still ate commensally with those who lived with others and ate commensally. This analysis allowed us to focus specifically on the mental-health effects of eating alone that were distinct from cohabitation. Our findings should present directions for further research on the link between households and depression or suicide. In addition, through our inclusion of young and middle-aged adults, we expanded the applicability of the results compared with previous studies that focused only on the elderly. Finally, we examined social structure characteristics (e.g., income level) that may modulate the association between eating alone and depression/suicidal ideation in adults. Understanding these interactions could provide better policy directions for addressing mental health problems in a population.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provided evidence that commensality was important for mental health. We demonstrated the need to consider individual characteristics and social networks when examining this link. Thus, future studies should include these factors when exploring further questions on commensality, for instance whether an individual desires eating together or wishes to avoid it, and whether the causes underlying solitary eating differ in single vs. multi-person households. Overall, given that our data suggest social isolation from eating alone could deteriorate both physical and mental health, social workers, educators and also policy developers to be aware of the importance of eating together and develop and to promote programs that encourage commensality. Our results are valuable as a basic resource for panel data analysis or a nested case-control study to identify sequential and casual relationships between commensality and mental health.

Acknowledgements

All authors have seen and approved the study and have met requirements for authorship.

Authors’ contributions

All authors took part in the planning of the study. The statistical analyses were performed by YHS, SSO, SIJ, ECP, SHP all contributed to the interpretation of the results. YHS drafted the manuscript and it was corrected and approved by all authors.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by a faculty research grant of Yonsei University College of Medicine (6-2018-0174).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Institutional Review Board, Yonsei University Health System (IRB number: Y-2019-002) as an exempted study. Ethical approval was not required as KNHNES provides anonymous, secondary data that is publicly available for scientific use.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yoon Hee Son, Email: kityuni21@gmail.com.

Sarah Soyeon Oh, Email: sarahoh@yuhs.ac.

Sung-In Jang, Email: JANGSI@yuhs.ac.

Eun-Cheol Park, Email: ecpark@yuhs.ac.

References

- 1.Organization WH . Mental health atlas 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang X, Shen W, Wang C, Zhang X, Xiao Y, He F, Zhai Y, Li F, Shang X, Lin J. Association between eating alone and depressive symptom in elders: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:19. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0197-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White HJ, Haycraft E, Meyer C. Family mealtimes and eating psychopathology: the role of anxiety and depression among adolescent girls and boys. Appetite. 2014;75:173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White HJ, Haycraft E, Wallis DJ, Arcelus J, Leung N, Meyer C. Development of the Mealtime Emotions Measure for adolescents (MEM-A): gender differences in emotional responses to family mealtimes and eating psychopathology. Appetite. 2015;85:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park HM, Lee HS. Influencing predictors of suicidal ideation in the Korean middle age. Korean J Stress Res. 2013;21:323–329. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung MS, Song HY, Kim WJ. Convergence study of eating together and mental health within 20–30’s: using 6 th (2013-2015) Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VI) J Korea Converg Soc. 2018;9:287–298. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim AY, Lee S-H, Jeon Y, Yoo R, Jung H-Y. Job-seeking stress, mental health problems, and the role of perceived social support in university graduates in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33(19):e149. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho W, Takeda W, Oh Y, Aiba N, Lee Y. Perceptions and practices of commensality and solo-eating among Korean and Japanese university students: a cross-cultural analysis. Nutr Res Pract. 2015;9:523–529. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2015.9.5.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho SE, Nam B, Seo JS. Impact of eating-alone on depression in Korean female elderly: findings from the sixth and seventh Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2014 and 2016. Mood Emot. 2018;16:169. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danesi G. Pleasures and stress of eating alone and eating together among French and German young adults. Menu. 2012;1:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SA, Park E-C, Ju YJ, Nam JY, Kim TH. Is one’s usual dinner companion associated with greater odds of depression? Using data from the 2014 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2016;62(6):560–568. doi: 10.1177/0020764016654505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tani Y, Sasaki Y, Haseda M, Kondo K, Kondo N. Eating alone and depression in older men and women by cohabitation status: the JAGES longitudinal survey. Age Ageing. 2015;44:1019–1026. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yates L, Warde A. Eating together and eating alone: meal arrangements in British households. Br J Sociol. 2017;68:97–118. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yi S-W, Jung M, Kimm H, Sull J-W, Lee E, Lee KO, Ohrr H. Usual alcohol consumption and suicide mortality among the Korean elderly in rural communities: Kangwha Cohort Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70:778–783. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-206849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giacoman C. The dimensions and role of commensality: a theoretical model drawn from the significance of communal eating among adults in Santiago, Chile. Appetite. 2016;107:460–470. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.08.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischler C. Commensality, society and culture. Soc Sci Inf. 2011;50:528–48.

- 17.Pliner P, Bell R: A table for one: the pain and pleasure of eating alone. In Meals in science and practice. Elsevier; 2009: 169-189.

- 18.Sobal J. Dimensions of the meal: the science, culture, business, and art of eating. 2000. Sociability and meals: facilitation, commensality, and interaction; pp. 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeda W, Melby MK. Spatial, temporal, and health associations of eating alone: a cross-cultural analysis of young adults in urban Australia and Japan. Appetite. 2017;118:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berardelli I, Corigliano V, Hawkins M, Comparelli A, Erbuto D, Pompili M. Lifestyle interventions and prevention of suicide. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:567. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang JL, Schmitz N, Dewa CS. Socioeconomic status and the risk of major depression: the Canadian National Population Health Survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:447–452. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.090910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yiengprugsawan V, Banwell C, Takeda W, Dixon J, Seubsman S-A, Sleigh AC. Health, happiness and eating together: what can a large Thai cohort study tell us? Global J Health Sci. 2015;7:270. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v7n4p270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho SH, Chun H, Lee HS, Lee SW, Shim KW, Lee JY, Byun AR, Lee HY. The relationship between shared breakfast and skipping breakfast with depression and general health state in Korean adults: the 2014 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Korean J Fam Pract. 2018;8:441–447. doi: 10.21215/kjfp.2018.8.3.441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang Y, Kang S, Kim KJ, Ko H, Shin J, Song Y-M. The association between family mealtime and depression in elderly Koreans. Korean J Fam Med. 2018;39:340. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.17.0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prevention KCfDCa . Guide to the utilization of the data from the seventh Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chun J-D, Ryu SY, Han MA, Park J. Comparisons of health status and health behaviors among the elderly between urban and rural areas. J Agric Med Community Health. 2013;38:182–194. doi: 10.5393/JAMCH.2013.38.3.182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oh SS, Kim W, Han K-T, Park E-C, Jang S-I. Alcohol consumption frequency or alcohol intake per drinking session: which has a larger impact on the metabolic syndrome and its components? Alcohol. 2018;71:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park H. Meals and social solidarity: emotional sociology of eating together. J Soc Thoughts Cult. 2017;20:133–180. doi: 10.17207/jstc.2017.09.20.3.133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee S. The integrated approach of the social and psychological factors affecting suicidal ideation. Democratic Soc Policy Stud. 2016;30:104–139. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park B. The path analysis for mutual relationship of stress and depression that affect the suicidality: comparison of sex and age group. Health Soc Welf Rev. 2012;32:485–521. doi: 10.15709/hswr.2012.32.3.485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi R, Moon H-J, Hwang B-D. The influence of chronic disease on the stress cognition, depression experience and suicide thoughts of the elderly. Korean J Health Serv Manage. 2010;4:73–84. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwak Y, Kim Y. Association between mental health and meal patterns among elderly Koreans. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18:161–168. doi: 10.1111/ggi.13106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song EG, Yoon YS, Yang YJ, Lee ES, Lee JH, Lee JY, Park WJ, Park SY. Factors associated with eating alone in Korean adults: findings from the sixth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2014. Korean J Fam Pract. 2017;7:698–706. doi: 10.21215/kjfp.2017.7.5.698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bofill S. Aging and loneliness in Catalonia: the social dimension of food behavior. Ageing Int. 2004;29:385–398. doi: 10.1007/s12126-004-1006-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nam HJ, Lee SG. Suicidal ideation of elderly living alone in urban and rural areas, its related factors. J Agric Med Community Health. 2017;42:145–154. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tani Y, Kondo N, Takagi D, Saito M, Hikichi H, Ojima T, Kondo K. Combined effects of eating alone and living alone on unhealthy dietary behaviors, obesity and underweight in older Japanese adults: results of the JAGES. Appetite. 2015;95:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han S, Lee S. Quality of life of youth living alone: with the focus of social capital influence. J Converg Soc Public Policy. 2018;12:60–85. doi: 10.37582/CSPP.2018.12.1.60. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee YJ. Gender differences in factors associated with the severity of depression in middle-aged adults: an analysis of 2014 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Korea Converg Soc. 2018;9:549–559. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song E, Kim J-Y. The relationship between employment status and depression: mediating effects through income and psychosocial factors. Health Soc Welf Rev. 2012;32:228–259. doi: 10.15709/hswr.2012.32.1.228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song SY, Jeong YH. Association between eating alone and metabolic syndrome: a structural equation modeling approach. J Korean Diet Assoc. 2019;25:142. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim SY, Seo MS, Seo YJ. The factors affecting on the suicidal intention of single person households: based on the 6th(2013, 2015) Korea National Health and Nutrition Survey. Korean Soc Wellness. 2018;13:489–498. doi: 10.21097/ksw.2018.08.13.3.489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim Y. Depression symptoms experience among adults in Korea, 2012. Public Health Wkly Rep. 2014;7:819–820. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.