Abstract

Objectives

This paper explores policies addressing migrant worker’s health and barriers to healthcare access in two middle-income, destination countries in Asia with cross-border migration to Yunnan province, China and international migration to Malaysia.

Design

Qualitative interviews were conducted in Rui Li City and Tenchong County in Yunnan Province, China (n=23) and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (n=44), along with review of policy documents. Data were thematically analysed.

Participants

Participants were migrant workers and key stakeholders with expertise in migrant issues including representatives from international organisations, local civil society organisations, government agencies, medical professionals, academia and trade unions.

Results

Migrant health policies at destination countries were predominantly protectionist, concerned with preventing transmission of communicable disease and the excessive burden on health systems. In China, foreign wives were entitled to state-provided maternal health services while female migrant workers had to pay out-of-pocket and often returned to Myanmar for deliveries. In Malaysia, immigration policies prohibit migrant workers from pregnancy, however, women do deliver at healthcare facilities. Mandatory HIV testing was imposed on migrants in both countries, where it was unclear whether and how informed consent was obtained from migrants. Migrants who did not pass mandatory health screenings in Malaysia would runaway rather than be deported and become undocumented in the process. Excessive attention on migrant workers with communicable disease control campaigns in China resulted in inadvertent stigmatisation. Language and financial barriers frustrated access to care in both countries. Reported conditions of overcrowding and inadequate healthcare access at immigration detention centres raise public health concern.

Conclusions

This study’s findings inform suggestions to mainstream the protection of migrant workers’ health within national health policies in two middle-income destination countries, to ensure that health systems are responsive to migrants’ needs as well as to strengthen bilateral and regional cooperation towards ensuring better migration management.

Keywords: health policy, public health, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first comparative qualitative study on health policies for migrant workers in two middle-income countries in Asia.

We offer practice and policy suggestions to mainstream migrant workers within national health policies.

Multiple stakeholders (health workers, civil society, government officials) insights were triangulated to identify cross-cutting themes.

Limitations included difficulties sampling migrant workers and lack of generalisable findings due to the qualitative nature of the study.

Introduction

International migration is an inevitable feature of today’s globalised world and is critical for the economic development of many nations. In 2017, 258 million international migrants were estimated worldwide, with 80 million residing in Asia.1 There are an estimated 164 million international migrant workers globally,2 many of whom face significant health risks from workplace accidents and poor working conditions, leading to physical and psychological morbidities.3 Despite these risks, just 6% of the global migration health literature focuses on migrant workers, relative to 25% on refugees and asylum seekers.4 By recent estimates, there will be close to 1.4 billion new working-age people in developing countries by 2050, of whom around 40% are unlikely to find meaningful employment in their home countries.5

This massive movement of people for work highlights the inevitability of economic growth and exchange, and yet international migrant workers are often considered a liability by destination countries despite their contributions to the economy. Potential health security and migrant control concerns have become essential policy drivers in many destination countries.6

In contrast, the right to the highest attainable standard of health, regardless of citizenship or immigration status, is enshrined in the WHO constitution and numerous human rights instruments.7 8 The right-based commitment to the health of migrant populations is reiterated in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the 2018 Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration.9–11 Among the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries and China, the ratification of international human rights treaties protecting the Right to Health is inconsistent, with only the Philippines and Indonesia, predominantly migrant-sending countries, ratifying the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families12 (table 1).

Table 1.

Ratification of international treaties protecting the right to health within ASEAN and China

| Country | International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights | Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women | International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights | International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination | Convention on the Rights of the Child | International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families |

| Migrant-sending countries* | ||||||

| Cambodia | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | x |

| Indonesia | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Lao PDR | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | x |

| Myanmar | √ | √ | x | x | √ | x |

| Philippines | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Vietnam | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | x |

| Migrant-receiving countries* | ||||||

| Brunei Darussalam | x | √ | x | x | √ | x |

| Malaysia | x | √ | x | x | √ | x |

| Singapore | x | √ | x | √ | √ | x |

| Thailand | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | x |

| China | √ | √ | x | √ | √ | x |

Source. United Nations treaty series online, 2019.99

*Predominantly.

ASEAN, Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Yunnan province, an important border province located in the southwest frontier area of China, shares substantial land borders (4060 km) with Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam.13 Through kinship networks, there are longstanding relationships of trade and ethnic interchange between local people along the four countries border lines.14 15 More recently, cross-border migration is enhanced by economic reform and the ‘opening up’ policies, especially with the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor, integral to the Belt and Road Initiative13 16 17. Largely due to economic disparities between the two countries, an increasing number of Myanmar citizens cross-national boundaries primarily in search of employment in China and others for marriage. Myanmar migrants are the fourth largest migrant community in China and most reside in Yunnan province.18

Malaysia, a vibrant Southeast Asian economy with relative political stability, is a magnet for low-skill, low-wage labour migrants from across the region and increasingly Asia. Between 2008 and 2018, the official numbers of documented migrant workers doubled from 1.1 to 2.2 million or 15% of the labour workforce in Malaysia.19 The number of undocumented workers in Malaysia is less certain, with estimates of all migrant workers ranging from 3.9 to 5.5 million, including undocumented workers.20 Of the 15 source countries, Indonesia (35%), Bangladesh (28%), Nepal (15%) and Myanmar (6%) are the largest contributors of migrant workers to Malaysia.21

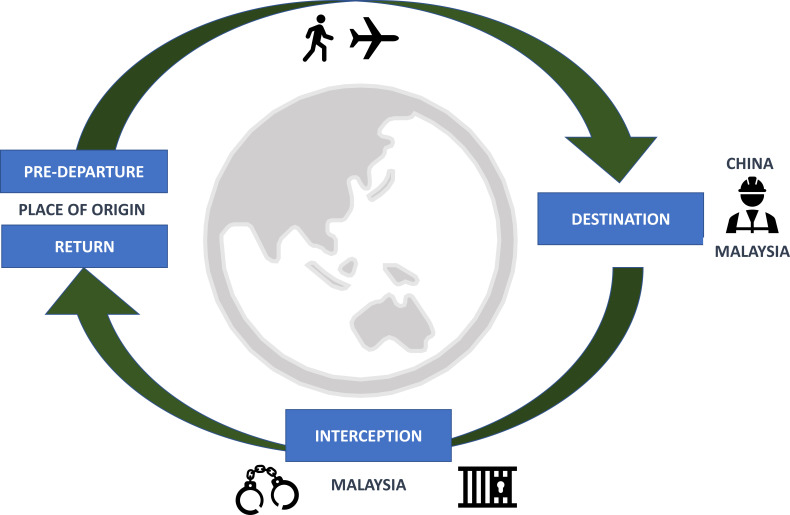

Increasingly, migration is circular with health outcomes influenced by the cumulative social determinants and health risks aggregated over the various phases of the migration cycle.22 23 In destination countries, migrant workers often fill undesirable low-skill, labour-intensive jobs in potentially health-damaging work environments and face numerous challenges including poor housing, discrimination, violence and exploitation, with restricted healthcare access.24–26 This paper explores policies that address migrant workers’ health and the barriers to healthcare access in two middle-income, destination countries in Asia with cross-border migration to Yunnan province, China and international migration to Malaysia (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Migration phases framework. Adapted from Zimmerman et al.22

Materials and methods

Study design

Qualitative methods were used in an exploratory, iterative design to describe and compare available healthcare policies and determine barriers in accessing healthcare experienced by migrant workers in Yunnan province, China and Malaysia.

Definition of terms

‘Migrant’ is a broad term. Here we focus on international labour migrants or migrant workers, both documented and undocumented, in Malaysia and Yunnan Province in China. Refugees, asylum seekers, victims of trafficking, people moving for marriage and expatriates are not included in this study.

A migrant worker or a foreign worker is defined here as a person who crosses international borders for the purpose of employment. Documented or regular migrants are authorised to enter, stay and partake in employment in a country and are in possession of legal documents such as passports and work permits. Undocumented or irregular migrants do not have the required documentation or authorisation to enter, reside or carry out remunerated activities in a country.27 28

Patient and public involvement

The topic guides for Malaysia and China were informed by review of literature and cross-country meetings to discuss research priorities. In Malaysia, purposive sampling of participants from a previous migration health workshop in November 201729 was conducted, with further snowball sampling until no new participants were identified. In China, purposive sampling was also used to select key informants in two study sites. Topic guides were slightly adapted throughout the study to account for participant’s priorities identified during interviews. Malaysia results were shared with research participants at a workshop in Kuala Lumpur in December 2019. In China, results were disseminated at the 10th International Conference on Public Health among Greater Mekong Sub-Regional Countries in November 2018.

Data collection

The health and welfare of migrant workers are contentious, with issues concerning immigration status being particularly sensitive. As such, we did not specifically target migrant workers only for interviews. We aimed to capture viewpoints of different stakeholders with expertise in migrant issues to obtain a broader understanding different policies and access to healthcare for this population. We conducted in-depth interviews with stakeholders including representatives from international organisations (IOs), local civil society organisations (CSOs), government agencies, medical professionals, academia, trade unions and others, in China and Malaysia.

Semistructured interview guides were developed to seek participants’ perspective on barriers to healthcare access for migrant workers. These guides were further customised to suit the organisational background of participants and were applied to both countries. Please see the interview guide in the online supplemental file.

bmjopen-2020-039800supp001.pdf (68.1KB, pdf)

Data collection was conducted between July and September 2018 in China and from July 2018 to July 2019 in Malaysia. Researchers purposefully recruited and interviewed migrant workers and key informants working closely with migrant workers. Further snowball sampling was conducted in each study site until the research teams agreed that additional interviews would not yield new information, as thematic saturation was reached.

In China, interviews were conducted with 23 participants in two-border counties, Rui Li City and Tenchong County in Yunnan Province. While interviews of 44 individuals were conducted in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. In China, individual interviews were conducted either in Mandarin or Myanmar language by two researchers (one researcher was able to speak the Myanmar language.) In Malaysia, individual interviews were conducted either in English or Bahasa Malaysia (Malay language) depending on the participants’ preference, by the multilingual research team. No interpreters were used. Table 2 describes the main characteristics of the study participants.

Table 2.

Characteristics of study participants

| China | Malaysia | |

| Organisation type | ||

| Local civil society organisations | 2 | 10 |

| International organisations | 0 | 4 |

| Trade unions | 0 | 3 |

| Medical doctors | 2 | 13 |

| Academia | 0 | 3 |

| Government officials | 4 | 2 |

| Industry | 0 | 5 |

| Migrant workers | ||

| Male | 4 | 2 |

| Female | 11 | 2 |

| Total | 23 | 44 |

Data analysis

The audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim into local languages. We conducted thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke, where themes or patterns of meaning within data were identified and reported using six phases: becoming familiar with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining themes and producing the report.30

Data analysis was conducted in an immersive, exploratory, iterative and inductive manner, initially separately in each country. Researchers in country teams reviewed and analysed transcripts independently, with regular discussions between researchers to refine codes and identify new themes. Transcripts were coded into emerging themes using NVivo V.12 Pro software and Microsoft Excel across research teams. Following initial analysis in both countries, selected quotations were extracted and were translated into English. Subsequently, the authors examined codes to identify the broader pattern of themes and subthemes across both countries. Desk review of policy documents including circulars, legal documents and memos served to contextualise and triangulate qualitative findings.

Reflexivity

Interviews in both countries were conducted by teams of academic researchers and medical doctors, that could be perceived as trusted authority figures. To minimise potential effects of social distance and power imbalances between researchers and participants, most interviews were conducted locations of the participants’ choosing, in a space they were comfortable in and at a time convenient to them. Migrant participants, in particular, were assured that they could refuse to answer questions or could choose to end the interview at any time. In doing so, we hoped that participants felt that they could exert a degree of control over the interview process.

Ethics

We sought to minimise harm to study participants by assuring anonymity and confidentiality. Written informed consent was obtained at recruitment. All participants agreed to be audio-recorded and quoted anonymously in publications. Given the sensitive nature of this research, patients were not asked to divulge personal identification information. Data were anonymised using pseudonyms and general descriptors without any identifying information. Study participation was entirely voluntary, and participants were informed that they could refuse to answer questions or terminate interviews at any point. We gave small gifts costing less than US$5 as tokens of appreciation for interviewees at both study sites. Electronic data such as audio files and transcripts were stored in secure servers, while other material was secured in locked cupboards at researcher’s offices.

Results

Study findings are presented by country and organised into major themes: policy setting, maternal and child health services, infectious disease and migrant workers, financial and language barriers to healthcare and health in detention. Table 3 summarises major study findings.

Table 3.

Main findings of the study

| China | Malaysia |

Policy setting

Maternal and child health services

Infectious diseases and migrant workers

Financial and language barriers to healthcare

|

Policy setting

Maternal and child health services

Infectious diseases and migrant workers

Financial and language barriers to healthcare

Health in detention

|

SPIKPA, Hospitalisation and Surgical Scheme for Foreign Workers.

China

Policy setting

Over the past two decades, the Chinese health system has undergone significant reform with the aim of providing safe, effective and affordable healthcare for citizens. Currently, Chinese citizens enjoy comprehensive medical services through government subsidised health insurance packages that are broadly location based and designed specifically for social groups such as urban employees, urban residents and rural residents. The policy for medical insurance as well as the household registry system, known as hukou, whereby citizens are registered by location of residence, has created ‘geographical barriers’ for internal migrants due to difficulties claiming health insurance across provinces.31 32 Despite growing numbers of international migrants, China lacks a cohesive national policy on the provision of healthcare for international migrant workers, who are not included in national health insurance schemes.

In contrast, Yunnan province has initiated several programmes to better facilitate the management of migrant workers. International Migrant Service and Management Centres have been established at border towns, such as Ruili city, the largest Sino-Burmese border port in Yunnan province. This centre established in June 2013, provides migrants with one-stop services to obtain the following documents: (1) health certificate, (2) work permit, (3) trading certificate and (4) temporary residential permit.33 According to local regulations, migrant workers who intend to temporarily reside in China for over a month are required to apply for these documents within 3 days of crossing the border and must have either a passport or a China-Myanmar border pass and an employment contract with a Chinese company for applications.34 China does not have mandatory predeparture health requirements for low-wage migrant workers.

According to officials interviewed, undocumented migrants are not allowed to work in China. The Chinese government conducts random inspections at border areas and those identified without the necessary documents are placed under temporary placement under the local police station before being repatriated to host countries within a few days. At the time of this study, there were no immigration detention centres in Yunnan province, China.

Specific health programmes for documented migrants in Yunnan province include maternal and child health services for non-citizen women and infectious disease prevention programmes at border areas.

Maternal and child health services

In border areas of Yunnan province, local health authorities provide a safe motherhood package for migrant women with legal identity certificates. Foreign spouses with legal marriage certificates are eligible for national health insurance with equal benefits as Chinese citizens. For example, the Health and Family Planning Commission of Whenshan prefecture, Yunnan issued guidelines for migrant maternal and child health services in January 2018. All migrant mothers, including foreigners who have stayed in Whenshan for more than 6 months, are eligible to obtain similar maternal and child health services as citizens.35 However, compared with foreign spouses, female migrant workers would have to pay out-of-pocket for these services, since she has no Chinese citizenship or household registration.

If a migrant worker is pregnant, she can visit any local hospital for maternity care. She would be eligible for hospital delivery, conditional on having antenatal records at that particular hospital. Owing to rigid guidelines, many foreign women were denied admission for delivery on account of their lacking antenatal records at specific hospitals.

My friend went to three hospitals before she was finally admitted for delivery. In the past, it was convenient to have children in X town. But now the government is strict on standardized medical management. Because she did not have an antenatal check-up at this hospital, there was no way to be admitted. Finally, we went to Y hospital. At that time her condition was very bad, very painful, as the baby was about to be born. So, the doctor let her stay, and finally, the child was born safely. Myanmar migrants used to choose to have children in X town. But now they must have tests and other records before they can be hospitalized. Many women have to go back to Myanmar to deliver a baby. Mei, female, migrant school administrator.

Infectious disease and migrant workers

According to government officials interviewed, Myanmar migrants, were perceived as a source of infectious disease transmission such as HIV and dengue fever due to their mobility and convoluted social relationships. Consequently, targeted infectious disease surveillance of non-citizens has become common practice at border townships.

HIV testing is compulsory for migrant workers entering China. To obtain a Health Certificate for International Travel, migrant workers must complete a post-arrival medical screening, which includes blood tests, urine tests, chest X-rays and mandatory HIV testing, within 3 days of arrival into China. Since the health certificate is only valid for a year, migrant workers must be screened annually for infectious diseases including HIV. These tests cost around US$20 and are paid for by the migrant worker.

Local health authorities also implement health intervention projects, including community-based health promotion campaigns targeting migrants at their settlements, for example, health education for landlords of migrants, distribution of free condoms and HIV screening. These activities are in addition to the mandatory screenings conducted by the immigration office to obtain health certificates. Although well intended, the excessive attention given to migrant workers with regards to infectious disease has inadvertently caused prejudice and stigmatisation. One community worker described the following:

We have a lot of Myanmar migrants here and it’s very difficult to do our work. We don't know their language. We don't have their phone number. Some people don't even have a cell phone. Many of them have come to X town, so they must have a temporary residence permit, and those in the factory have had to apply for a health card. They [government authorities] have already drawn blood and tested it. When we [health workers] go to the community, they don't want to do the blood test [migrants refuse]. They look for various excuses not to draw blood. When they see us in the community, they start running, and they don't come at all. It is perceived [by migrants] that we are drawing blood over and over again. They are disgusted and repelled. Chen, male, community health worker.

Although informed consent is obtained prior to screenings by the immigration office, our findings suggest that migrants’ understanding of health activities that they are consenting to is lacking. Language barriers and the lack of cultural sensitivity have likely exacerbated migrants’ distrust of healthcare providers.

The local government conditionally provides free antiretroviral treatment to HIV-infected Myanmar citizens. Two groups of Myanmar migrants are eligible, these are long-time residents who have stayed in China for at least 6 months with valid identity documents, and migrant wives with valid marriage documents (which may consist of a marriage certificate or a letter from the village office).36 To discourage foreign patients from coming to China to obtain free medical services, non-citizens are not provided with free investigations or hospitalisations for HIV infections.

Free services for all are not feasible since policies related to HIV treatment and health care are not consistent between the two countries. If we are the only ones offering free services, the patients from the Myanmar side would flood into China. We are not capable to deal with this situation due to limited financial and human resources which are allocated according to domestic population rather than international migrants. Yang, female, government official.

Resource constraints meant that policies were deliberately designed to discourage care seeking for HIV treatment among cross-border migrants in China.

Financial and language barriers to healthcare

Those interviewed revealed that Myanmar migrants rarely seek medical services in China, mainly due to financial and language barriers.

Medical treatment at public hospitals is expensive and unaffordable to low-wage migrant workers. Since they are not covered by health insurance, migrant workers are subject to high out-of-pocket payments when seeking care. Also, most employers will not pay for medical expenses or purchase medical insurance for employees. As such, most migrant workers resort to self-treatment or return to Myanmar border towns for healthcare.

People who come out to work are generally in good health. Most of us are young people. Old people [migrants] do not come out to work, because the cost of medicine is very expensive in China. It is not worth the money to see a doctor when you are sick. We will buy medicine for ourselves if we are ill [self-medicate]. If we have a slightly more serious illness, almost all of us will go back to Myanmar for treatment. Because seeing a doctor in China is too expensive. We usually go back to Myanmar to see a doctor for about 50 yuan (less than 10 USD), but in China, 50 yuan is not enough. If we must be hospitalized, we must pay a deposit of 5000 yuan (about 800 USD). That is impossible for us, Myanmar[workers] to get so much money all at once. We don't have to pay deposit in Myanmar, we pay the bill when we leave the hospital. Tok, male, migrant worker.

This participant implied that high healthcare costs in China deterred older workers from Myanmar from migrating.

One interviewee suggested that given the opportunity, Myanmar migrants would opt in to Chinese health insurance scheme, as that would lessen their financial burden while providing healthcare access.

China has good medical facilities. Rich Myanmar people will choose to see a doctor in China, but for the average Myanmar people, they cannot do the same. People have heard that China has health insurance, but Myanmar migrants can't buy it. For Myanmar migrants like us who live in China for a long time, we really want to be able to buy Chinese health insurance, and the grade of insurance can be divided into different amounts. Everyone can buy health insurance according to their own ability. There are many Myanmar laborers in China, it will be much more for them, if they have health insurance, they can also reduce the economic burden. Yang, female, migrant worker

Migrant workers tend to avoid public hospitals because of language barriers. Very few healthcare workers speak Myanmar languages, and migrants face difficulties in communicating and navigating the health system. Migrant workers often need to find a Chinese language interpreter, either a colleague or friend, to accompany them when seeking care at hospitals. This migrant worker expressed frustration at the lack of language-friendly services in China and suggested improvements.

My friends have told me that when they go to see a doctor, because the patients do not understand what the doctor says, and the doctors will be angry [with them] after asking many times [questions repeatedly].I hope there is a Chinese-Myanmar contrast (bilingual information) at every window of the hospital, so that we can know which department we should go to. The staff of the guidance desk should speak Burmese. If possible, I hope they can recruit Burmese-speaking doctors, so that it be much easier [for us]. I hope that doctors will be more patient, communicate with us with simple words and speak slowly, so we can understand. Nuinui, female, migrant worker.

While this participant described Burmese doctors as a possible solution to language barriers, we did not come across any instances of this occurring within two-border counties studied. Foreign doctors must pass the Chinese medical exams and have a valid medical diploma, making it very difficult to practise in China. Furthermore, there are no formal interpreter provisions in the Chinese health system, which is also the case in Malaysia.29

Malaysia

Policy setting

Being a net migrant-receiving country, Malaysia has several health policies in place for migrant workers. It is mandatory for foreign nationals seeking employment in Malaysia to have undergone a predeparture medical examination prior to entry into Malaysia. The Ministry of Health, Malaysia with the cooperation of migrant-sending countries selects clinics to conduct predeparture medical examinations of prospective workers. Predeparture medical examination generally consists of infectious disease screening for HIV and tuberculosis (TB).37

In addition, the Malaysian government established the Foreign Workers Medical Examination and Monitoring Agency (FOMEMA) to carry out pre-employment medical examinations, within the first month of arrival into Malaysia and subsequently annual medical examinations when renewing work permits, at private clinics approved by the FOMEMA. These medical examinations are paid for by employers, and all documented migrant workers are mandatorily tested for TB, HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, malaria, leprosy, pregnancy (for women), drug abuse, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cancer, epilepsy and psychiatric illness.38 39

Malaysia has a mixed public–private healthcare system. The public healthcare system is subsidised for citizens, but non-citizen fees are much higher.40 At the same time, a government-mandated compulsory insurance scheme, the Hospitalisation and Surgical Scheme for Foreign Workers (SPIKPA) provides documented workers with a maximum of RM 20 000 (US$4800) annually for in-patient care and surgery in public hospitals.41 Some employers pay for workers treatment at private clinics, but this is not a legal obligation, as such it is not standard practice.42

Maternal and child health services

Due to immigration requirements, female migrant workers are prohibited from marrying or becoming pregnant in Malaysia. Those testing positive for pregnancy will not be granted work permits and are subjected to deportation.43 44 While there are no specific public antenatal or delivery services offered for migrant workers in Malaysia, in practice women do give birth in healthcare facilities, often at private facilities and at high cost. While public healthcare facilities will not deny patients necessary medical care, healthcare providers are obliged to report undocumented workers to the police and immigration authorities. This physician explains the situation at public Maternal and Child Health Clinics.

It is very sad for refugees or illegal migrants who do not have any passport or documents [UNHCR cards or valid work permit], they will [need documents to] register at the counter. If they need to see the Family Medicine Specialist [FMS], foreigners, they have to pay extra – maybe RM 30 [8 USD] or something like that. They will register and pay the money, while she is inside seeing the doctor, the police are already outside, waiting for her. Once she is out, she will be caught by the police. This has happened many times at the ‘Klinik Ibu dan Anak’ [public Maternal and Child Health Clinic]. Dr Lucy, female, physician

Other CSO interviewees informed of incidents of undocumented migrant women being taken to immigration detention centres immediately after delivery at public hospitals.

Due to immigration restrictions at public facilities and the expense of antenatal care at private facilities, non-citizens tend to present late for booking and default follow-up. Some migrants prefer to deliver at home, assisted by traditional midwives. This doctor expressed concern that non-citizens often present late at hospitals for delivery, without prior antenatal follow-up.

They usually come in emergency, like ectopic[pregnancy] with abdominal pain. My colleagues, they will say, ‘Bila dah almost deliver baru datang?’ (Sarcastic: You only come to hospital when you’re about to deliver?). Because they didn’t follow up during the antenatal stage. Because of financial and other reasons, they only come at the late stage […]. Dr Nazirah, female, physician

Participants shared that the inadequate antenatal care, late presentation for hospital delivery and home deliveries may result in poor obstetric outcomes.

Infectious disease and migrant workers

The Malaysian government requires a predeparture medical examination to be conducted at designated clinics in migrant-sending countries. Some interviewed questioned the quality of medical screenings conducted in migrant-sending countries, due to the lack of regulation and potential corruption.

The medical tests done in the country of origin is not audited. So, there is a lot of instances where people do not pass the medical test, but they obtain a certificate and then they come here. When they come here, the requirement is that the medical test [pre-employment screening done on arrival in Malaysia] results must be submitted with the application to do your work permit. Only then will your work permit will be approved. What we see is, when they come here, they fail the medical test. Priya, female, civil society organisation.

In order to obtain a work permit, migrant workers are required to undergo a mandatory pre-employment medical examination within the first month of arrival. Mandatory annual medical examinations are conducted annually for the first 3 years, and subsequently every alternate year for a maximum of 10 years of employment in Malaysia. The consequence of failing these mandatory medical examinations is severe, as workers are denied work permits and are subjected to deportation. This interviewee informed that failing medical examinations is a possible reason for migrant workers to become undocumented.

Once they have got leprosy or mental health disease or… [ failed medical examination], they are deemed 'unfit' or unsuitable [for employment]. So, once you deem them unsuitable [unfit] in your medical examination, the employer has to send them back. And THAT is where a lot of problems arise. Because when they [migrant workers] come to know that they have to be sent back, they disappear. And they become 'undocumented'. This is a huge problem. Dr Amir, male, a doctor in private practice.

Some interviewed shared that screenings were for medically treatable conditions and should not preclude employment. This interviewee felt that infectious diseases, like TB, is of public health concern and should be treated on detection.

Yes, TB also, to some extent, it can be contained, right? And it is medically treatable. He [the migrant worker] is not incapable of working. The moment he has TB, what they do is, they pack him and send him back home. And (if) this guy doesn’t get back home and get treatment- he’s going to spread it to others. You’ve got to treat the disease before you actually send him back home. Rosa, female, country coordinator of an international organisation.

Medical doctors interviewed explained that while general consent is obtained for medical screenings, the consent obtained is not specific for HIV testing. There was also concern expressed on patient confidentiality, as employers are informed of investigation results.

We obtain a general consent for blood STD (sexually transmitted disease) investigation as our regulations, but not specifically for HIV. If found positive, we need to call the worker and the employer, as we need to explain to the employer the reason the worker needs to be sent back. So, confidentiality is affected there. Dr Sashi, male, a doctor in private practice.

Others expressed concern that migrant workers are not properly informed of test results and are uncertain of their infectious disease status even though testing is mandatory.

A lot of them just do not know [their status]. I think once they go through FOMEMA screening, the least they can do is be made aware of the HIV status. Of course, they wouldn’t be able to come in [to the country]. But it would be good for them to know, even if they are being sent back—to know their HIV status. John, male, an academic.

The implication is that workers were only informed of HIV test results in terms of pass or fail, and are not given detailed results, or post-test counselling.

Financial and language barriers to healthcare

Healthcare costs are a major barrier for migrant workers accessing healthcare in Malaysia. Participants felt that the coverage by the SPIKPA insurance is inadequate in compensating the considerably higher fees charged to non-citizens at public hospitals and clinics. Furthermore, SPIKPA does not cover outpatient treatment. Consequently, migrant workers are likely to pay out-of-pocket for healthcare.

We migrants only have insurance for hospitalisation. When we are ill, our employers say, ‘I can’t give you medicine. I won’t send you for treatment.’ Why? It costs a lot! If you want medication, it’s up to you. You buy yourself. Yat, male, migrant worker and union organiser

Migrant workers prioritise sending money home to families and are less willing to spend money on healthcare. Participants described healthcare avoidance and the use of traditional medicine as a common practice among migrant workers.

As there are no formal interpreters in the Malaysian healthcare system, we found that the common expectation is for migrant workers to learn the Malay language or to bring a companion to act as an informal translator. Healthcare providers also use various methods to communicate with patients including sign language, gestures, Google translate and others.

Doctors interviewed express frustration as language barriers hinder communication and patient management.

Those from Myanmar [have a] major barrier when it comes to communication. Bangladeshis pickup Malay very, very fast. They only need to work here about a year and then they will be able to have a full conversation with you. Whereas the Burmese, they are still very backward with the language. Nepalese, some of them can speak English quite well. The Myanmar group is very difficult. Very, very difficult. It’s literally sign language and acting out the illness, and all sorts of things. Dr Ram, male, a doctor in private practice

This medical practitioner explained that there were notable differences faced by different migrant populations and their ability to communicate in the Malay language.

Health in detention

Immigration offences like illegal entry and stay are criminal offences in Malaysia. Many undocumented workers are arrested and imprisoned, before being sent to immigration detention centres (immigration depots) to await deportation. To facilitate the process of deportation, embassies are contacted to issue travel documents. The duration of detention is often lengthy and dependant on the detainee’s ability to finance repatriation costs, including the purchasing of flight tickets.

[Some] embassies have allocations to help finance repatriation of their citizens in detention, but in a limited manner and [based] on the severity of the case. From my observation, most migrants have to get families to pay for tickets […] Ryan, male, member of a local civil society organisation.

Interviewees describe conditions at immigration detention camps as overcrowded and uncomfortable.

I have experience of visiting a Filipino who overstayed here, in X [immigration detention centre]. I think it’s not easy. They didn’t have anything. They [the authorities] didn't provide bedding, even a sleeping mat. They [inmates are] just sleeping on the floor, on the cement. And they didn’t have a toothbrush […]. Food is okay. It is limited, but still they can eat. But they had bad experience. They just sleep on the cement. Beth, female, a migrant worker representative at a local civil society organisation.

Others explained that healthcare services available at the camps were minimal, with only a paramedic stationed on-site. Detainees found to be ill are sent to public hospitals for further clinical management. Dr Goh, a physician who investigated conditions at an immigration detention centre following a major typhoid outbreak commented:

This lockup (depot) was designed for 750 people, however, from our investigation, we found out that there were almost 1500 people are staying in that centre. There was overcrowding. The conditions were not at all sanitary. The initial plans for the lockup were designed for a cook-someone who cooks for all the inmates. But we discovered that the inmates cook for each other. And the food that is provided there is mostly carbohydrate-based. And a lot of them (detainees) do not have proper supervision in terms of medication. For example, TB medication. DOTS (Directly observed treatment) is not carried out as per plan. Because there is a lack of manpower. Dr Goh, female, physician.

Discussion

We found that migrant health policies at destination countries were largely protectionist in nature, concerned with preventing the spread of communicable disease and the perceived excessive burden on national health systems due to in-migration.

In general, migrants are considered at particular risk for infectious diseases like HIV, TB and malaria, due to the relatively high disease prevalence, poor socioeconomic conditions and weak health systems at origin countries.23 45–48 Both Malaysia and China have mandatory medical screenings for migrant workers, with predeparture screenings at origin countries required by Malaysia and postarrival screenings enforced by Malaysia and Yunnan province, China.37 49 Contrary to narratives about migrants being infectious disease carriers, the reality may not be so dramatic. FOMEMA reported that just 3 in 100 migrant workers tested positive for infectious diseases in recent years.50 Mandatory medical screenings are part of labour migration policies that determines health status as an eligibility criterion for entry into a country and stay for employment.51 This is problematic from the human rights and ethical standpoints, as mandatory testing is conducted merely for immigration selection and not to improve the individuals’ health. Also, mandatory HIV testing of migrant workers contravenes with international standards for informed consent, confidentiality, counselling and referral to treatment and care services.52–55 Our findings from both Yunnan province and Malaysia suggest that informed consent for HIV testing may be inadequate, as migrants were unsure of tests conducted, without access to pretest and post-test counselling.

Our findings also suggest that communicable disease control programmes in Yunnan province, China are poorly received by migrants. Linguistic and culturally appropriate public health interventions are key to acceptance and cooperation among non-citizen populations.56–58 We caution against the inadvertent negative stereotyping and stigmatisation of migrants and suggest that public health interventions be guided by epidemiological evidence and conducted with sensitivity. Furthermore, the lack of medical services for individuals diagnosed with infectious disease both in China and Malaysia, combined with the fear of deportation, may hinder initiatives promoting testing of migrants.59 A more pragmatic approach towards disease control is needed without neglecting the provision of high-quality preventive and curative care, to ensure early detection and treatment of infections for the benefit of the individual migrant and society.51 60 61

All countries in ASEAN and China have ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, which recognises the right to sexual and reproductive health as fundamental to women’s health.62 A core minimum state obligation in fulfilling these international human rights agreements is the provision of access to quality, affordable maternal health services that would prevent maternal mortality. Unlike Yunnan province where maternal health services are available for non-citizens with certain administrative requirements, immigration policies in Malaysia are a barrier to the access of services at public facilities. The imposition of mandatory testing for pregnancy and HIV has been likened to a violation of the right to privacy and bodily integrity and is an example of conflict between immigration policy, human rights and public health.63

Highlighted in this paper are the financial, language and legal barriers to healthcare access in destination countries. Due to escalating healthcare costs and the revelation that foreigners were consuming a sizeable portion of the national health allocation, the Malaysian government substantially revised medical fees for non-citizens at public hospitals and clinics in 2014.40 64 Our findings suggest that the government-mandated SPIKPA insurance for documented migrants is easily breached due to high treatment costs.41 42 65 66

Previous studies support our findings that low-skilled international migrants in China are without health insurance.67 Although maternal and child health services are available for non-citizens in Yunnan province, the use of this service is questionable as stringent administrative requirements and out-of-pocket payments needed to finance care make hospital delivery inaccessible. Our findings in Malaysia and China suggest that high out-of-pocket payments and inadequate health insurance coverage are significant financial barriers to access, resulting in healthcare avoidance among migrants.

Language discrepancies may induce psychological stress, misunderstanding of health risks and medically significant communication errors impacting the quality and effectiveness of healthcare delivery.68–72 Countries like Malaysia receive migrant workers from a multitude of countries. Such diverse backgrounds pose a challenge to health systems in coping with distinctive languages and cultures.29 Not surprisingly, the implicit expectation of destination country health systems, seen here with examples from Malaysia and China, is for non-citizens to develop local language proficiency. We suggest that destination countries actively invest in developing migrant-sensitive health systems, engaging migrant communities as patient navigators and intercultural mediators, hiring professional interpreters and training culturally competent health professionals.73–75

Undocumented migrants are an especially vulnerable group, as they lack the legal and social protections given to their documented counterparts. Denying healthcare to undocumented migrants increases disparities among this already vulnerable group.76 Unlike Malaysia, China does not impose mandatory reporting between health facilities and immigration when undocumented migrants try to use services. The requirement for health workers in Malaysia to report non-citizens without appropriate documents,77 78 is likely to have far-reaching implications on public health, healthcare expenditure and clinical practice.76 79

Malaysia has 14 immigration centres nationwide,80 while there are none in Yunnan province, China. Determining who enters or stays in a country is a matter of state sovereignty. However, the threat of detention as a means of deterring irregular migration is problematic.81 82 While states have the authority to regulate migration through immigration enforcement, guarantees against arbitrary detention migrants are enshrined in international human rights instruments.83–85 The adverse health effects of detention on the mental and physical health of migrants are well catalogued.86–88 Conditions in immigration detention in Malaysia are reported here and elsewhere, as overcrowded, unsanitary and with insufficient medical care,89–92 representing a major public health challenge. The Mandela Rules, or the revised UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, which states the minimum standards for detention in prisons, are also applicable to immigration detention centres93 and Malaysia should open their immigration detention centres for an independent audit to ensure compliance with these minimum standards.

Low-wage migrants may return to home countries in poor health, requiring healthcare that is unavailable or unaffordable in countries of origin. With this is in mind, there are concerns about the transferability of destination countries’ social protection policies when migrants return to countries of origin. One such scheme that will test the portability of benefits is the recently introduced Employment Injury Scheme for Foreign Workers under the Malaysian Social Security Organization, which provides life-long cash payments for permanent disablement from injury or illness arising during the course of employment.94

We suggest that origin countries consider providing health insurance for the benefit of returning workers. One such example is the mandatory insurance coverage provided for overseas Filipino workers by employment agencies at no cost to the worker, as legislated by Philippines law.95

Improving migrant health requires commitment from both migrant-sending and receiving countries as well as bilateral and regional partnerships. Memorandum of understandings between migrant-sending and receiving countries could improve referral mechanisms to ensure proper treatment of returnees with an infectious disease or occupational injuries. Thailand has successful bilateral agreements with neighbouring Myanmar, allowing for cooperation via the Nationality Verification and One Stop Service Centre regularisation processes for migrants arriving in Thailand through irregular channels.96 The example of cross-border coordination mechanisms for migration and health as demonstrated by Thailand and Myanmar would benefit other strategic border areas with health concerns associated with population movement. Countries should also build on commitments made on regional platforms like the 2007 ASEAN Declaration on the Protection of the Rights of Migrant Workers to protect and promote the rights of migrant workers in the region.97 98

Malaysia and China are both upper middle-income countries with advanced health systems. However, protectionist policies lead to unequal treatment of migrant workers resulting in poorer availability of healthcare services compared with citizens. We hope that national efforts towards achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) include migrant workers, following the concept of ‘leave no-one behind’ envisioned in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.11

Our study has several limitations. Due to the sensitive nature of this study, we had difficulties obtaining interviews with migrant workers. Nevertheless, we were able to triangulate study findings by interviewing diverse key informants including representatives of civil society and IOs, trade unions and academia, medical doctors and government officials. As qualitative approaches were used in this study, findings are grounded to specific contexts and populations and this precludes generalisation of findings. Nevertheless, the experience gained by examining different perspectives gives us insights into health policy and barriers accessing healthcare in different settings. Also, while our study focuses on health in destination countries, we acknowledge that health and healthcare in origin countries and during the travel and return phase of migration may impact migrant well-being, thus have given some policy suggestions.

Conclusion

This study has unique contributions, as a comparative study of healthcare access and migrant health policy between China and Malaysia, two middle-income destination countries. We suggest options to mainstream the protection of migrant workers’ health within national health policies to ensure that health systems are responsive to migrants’ needs as well as to strengthen bilateral and regional cooperation towards ensuring better migration management.

Migration brings great benefits, fuelling socioeconomic growth in migrant-sending and receiving countries. Yet, insufficient attention is paid to the health of migrant workers. The intersectional nature of healthcare and immigration policy in destination countries commodify human life, contradicting with public health needs and ethical norms. We appeal to governments to use human rights principles and national commitment towards UHC to guide the provision of migrant inclusive and sensitive healthcare accessible to all, for the betterment of individual and population health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by The Atlantic Fellows for Health Equity in South East Asia based at The Equity Initiative, a program of The CMB Foundation.

Footnotes

TL and DR contributed equally.

Contributors: Both TL and DR conceptualised the study, analysed the data, managed the overall design of the study and wrote the draft. NSP provided comments on the draft and critically revised content. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: We are grateful for funding to conduct this research from the China Medical Board’s Equity Initiative [IF055-2018]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from Institutional Review Boards at University Malaya, Malaysia (UM.TNC2/UMREC-238) and Kunming Medical University, China (kmu42018049), as well as the Medical Research and Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health, Malaysia (NMRR-18-1309-42043).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.United Nations International migration report 2017-Highlights. United Nations, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popova N, Özel MH. ILO global estimates on international migrant workers: results and methodology. 2nd ed Geneva: International Labour Office, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hargreaves S, Rustage K, Nellums LB, et al. . Occupational health outcomes among international migrant workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e872–82. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30204-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sweileh WM, Wickramage K, Pottie K, et al. . Bibliometric analysis of global migration health research in peer-reviewed literature (2000-2016). BMC Public Health 2018;18:777. 10.1186/s12889-018-5689-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith R, Hani F. Labor mobility partnerships: expanding opportunity with a globally mobile workforce. Final report of the Connecting International Labor Markets Working Group. Washington: Centre for Global Development, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Health of migrants: the way forward: report of a global consultation. Madrid, Spain: World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization International Migration, Health & Human Rights. Health & Human Rights Publication Series Issue No4. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization Constitution of the World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations General Assembly Global compact for safe, orderly and regular migration A/RES/73/195. Nations U, ed New York, United States, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.United Nations Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tulloch O, Machingura F, Melamed C. Health, migration and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.UNDP The Right to Health. Right to Health for low-skilled labour migrants in ASEAN countries. Bangkok: UNDP, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhenming Z. China’s Opening-up Strategy and Its Economic Relations with ASEAN Countries-A Case Study of Yunnan Province. 435 Institute of Developing Economies, Japan External Trade Organization VRF Series, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bie QL, Zhou SY, Li CS. The impact of border policy effect on Cross-border ethnic areas. Int Arch Photogramm Remote Sens Spatial Inf Sci 2013;XL-4/W3:35–40. 10.5194/isprsarchives-XL-4-W3-35-2013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labour migration, gender and sexual and reproductive health and rights Women’s, gender and rights perspectives in health policies and programmes: Arrow for Change. 19, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yhome K. Emerging dynamics of the China-Myanmar economic corridor. Observer Research Foundation, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao H, Yang M. China-Myanmar economic corridor and its implications. East Asian Policy 2012;04:21–32. 10.1142/S1793930512000128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suqing T. Means of livelihood and living space of registered Burmese nationals living in the towns in the Sino-Burmese border area (in Chinese). J Ethnol 2017;8:75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Statistics Malaysia Labour Force Survey (LFS) time series statistics by state, 1982-2018, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwok-Aun L, Leng KY. Counting migrant workers in Malaysia: a needlessly persisting conundrum ISEAS perspective. Singapore: ISEAS: Yusof Ishak Institute, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Home Affairs Malaysia Number of foreign workers by state and sector until June 30, 2019. May 17, 2018 ed, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimmerman C, Kiss L, Hossain M. Migration and health: a framework for 21st century policy-making. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001034. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gushulak BD, MacPherson DW. Globalization of infectious diseases: the impact of migration. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38:1742–8. 10.1086/421268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benach J, Muntaner C, Delclos C, et al. . Migration and "low-skilled" workers in destination countries. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001043. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simkhada PP, Regmi PR, van Teijlingen E, et al. . Identifying the gaps in Nepalese migrant workers' health and well-being: a review of the literature. J Travel Med 2017;24:jtm/tax021. 10.1093/jtm/tax021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ang JW, Chia C, Koh CJ, et al. . Healthcare-seeking behaviour, barriers and mental health of non-domestic migrant workers in Singapore. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000213. 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.International Organization for Migration Key migration terms, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.IOM The UN migration agency No. 34 international migration law. Glossary on migration, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pocock NS, Chan Z, Loganathan T, et al. . Moving towards culturally competent health systems for migrants? applying systems thinking in a qualitative study in Malaysia and Thailand. PLoS One 2020;15:e0231154. 10.1371/journal.pone.0231154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meng Y, Han J, Qin S. The impact of health insurance policy on the health of the senior floating population—evidence from China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:2159 10.3390/ijerph15102159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng Y, Ji Y, Chang C, et al. . The evolution of health policy in China and internal migrants: continuity, change, and current implementation challenges. Asia Pac Policy Stud 2020;7:81–94. 10.1002/app5.294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yunnan Xinhua Net Creating a new comprehensive platform for the convenience of foreign personnals in Rui Li. 2019 ed, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruili People’s Government Office A interim management and service regulation for international migrants in Ruili City, issued on 30 September, 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wenshan Prefecture Health and Family Planning Commission The interim management plan for migrant pregnant women in Wenshan Prefecture of Yunnan Province, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Standing Committee of Yunnan Provincial People’s Congress Aids prevention and treatment regulations in Dehong Prefecture in Yunnan Province, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khairul Anuar A, Nooriah MS. Pre-employment screening & monitoring of the health of foreign workers. J Transl Med 2012;7. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jayakumar G. Pre-employment medical examination of migrant workers--the ethical and legal issues. Med J Malaysia 2006;61:516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Federation ME Practical guidelines for employers on the recruitment, placement, employment and repatriation of foreign workers in Malaysia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cruez AF, Phung A. New rules for foreigners going to gov't hospitals. The Sun Daily, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ministry of Health Malaysia Circular of the financial division No.1/2011: procedures for the administration of hospital admissions and medical claims for foreign workers under the foreign workers health insurance scheme (SPIKPA) at Ministry of health Malaysia hospitals, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loganathan T, Rui D, Ng C-W, et al. . Breaking down the barriers: understanding migrant workers' access to healthcare in Malaysia. PLoS One 2019;14:e0218669. 10.1371/journal.pone.0218669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Indonesian female factory workers: the gendered migration policy in Malaysia. People :Int Soc Sci J 2016;2:643–64. 10.20319/pijss.2016.s21.643664 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loganathan T, Chan ZX, de Smalen AW, et al. . Migrant women's access to sexual and reproductive health services in Malaysia: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:ijerph17155376. 10.3390/ijerph17155376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J-bao, Li Y-ling, Yang J, et al. . Proportions and correlates of recent HIV infections among newly reported HIV/AIDS cases in Dehong prefecture, Yunnan province during 2010-2011. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2012;33:991–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang B, Liang Y, Feng Y, et al. . Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus 1 infection in the last decade among entry travelers in Yunnan Province, China. BMC Public Health 2015;15:362. 10.1186/s12889-015-1683-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li L, Zhang YC, Yang YC, et al. . Risk behaviors among newly reported Burmese HIV infection in Dehong, Dai and Jingpo Autonomous Prefectures of Yunnan province, 2015. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2016;37:1596–601. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sadarangani SP, Lim PL, Vasoo S. Infectious diseases and migrant worker health in Singapore: a receiving country's perspective. J Travel Med 2017;24:jtm/tax014. 10.1093/jtm/tax014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leong CC. Pre-employment medical examination of Indonesian domestic helpers in a private clinic in Johor Bahru--an eight year review. Med J Malaysia 2006;61:592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bernama Fomema: three out of 100 foreign workers suffer from infectious diseases. The Sun Daily, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wickramage K, Mosca D. Can migration health assessments become a mechanism for global public health good? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:9954–63. 10.3390/ijerph111009954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.World Health Organization Consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services: 5Cs: consent, confidentiality, counselling, correct results and connection, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.CARAM Asia State of health of migrants 2007: mandatory testing. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 54.ILO The ILO code of practice on HIV/AIDS and the world of work: module, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 55.ILO Subregional Office for East Asia IOM Mandatory HIV testing for employment of migrant workers in eight countries of South-east Asia: from discrimination to social dialogue, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fleckman JM, Dal Corso M, Ramirez S, et al. . Intercultural competency in public health: a call for action to incorporate training into public health education. Front Public Health 2015;3:210–10. 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saether ST, Chawphrae U, Zaw MM, et al. . Migrants' access to antiretroviral therapy in Thailand. Trop Med Int Health 2007;12:999–1008. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laverack G. The challenge of promoting the health of refugees and migrants in Europe: a review of the literature and urgent policy options. Challenges 2018;9:32 10.3390/challe9020032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Littleton J, Park J, Thornley C, et al. . Migrants and tuberculosis: analysing epidemiological data with ethnography. Aust N Z J Public Health 2008;32:142–9. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khan MS, Osei-Kofi A, Omar A, et al. . Pathogens, prejudice, and politics: the role of the global health community in the European refugee crisis. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16:e173–7. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30134-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vignier N, Bouchaud O, Travel BO. Travel, migration and emerging infectious diseases. EJIFCC 2018;29:175–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.UN General Assembly Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women (CEDAW): resolution 34/180, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marin MLS. When crossing borders: recognising the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women migrant workers. Arrow for change 2013;19. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lau B. Foreigners' RM50mil healthcare debt forces the government to reform measures. MIMS Today, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Malay Mail Health Ministry hikes up Hospital fees for foreigners up to 230pc. Malay Mail, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nordin R, Abd Razak MF, Shapiee R, et al. . Health insurance for foreign workers in Malaysia and Singapore: a comparative study. Int J Bus Soc 2018;19:400–13. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maimaitijiang R, He Q, Wu Y, et al. . Assessment of the health status and health service perceptions of international migrants coming to Guangzhou, China, from high-, middle- and low-income countries. Global Health 2019;15:9. 10.1186/s12992-019-0449-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meuter RFI, Gallois C, Segalowitz NS, et al. . Overcoming language barriers in healthcare: a protocol for investigating safe and effective communication when patients or clinicians use a second language. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:371. 10.1186/s12913-015-1024-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilson E, Chen AHM, Grumbach K, et al. . Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:800–6. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0174.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Divi C, Koss RG, Schmaltz SP, et al. . Language proficiency and adverse events in US hospitals: a pilot study. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:60–7. 10.1093/intqhc/mzl069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hunt LM, de Voogd KB. Are good intentions good enough? Informed consent without trained interpreters. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:598–605. 10.1007/s11606-007-0136-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Moissac D, Bowen S. Impact of language barriers on quality of care and patient safety for official language minority Francophones in Canada. J Patient Exp 2019;6:24–32. 10.1177/2374373518769008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jongen C, McCalman J, Bainbridge R. Health workforce cultural competency interventions: a systematic scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:232. 10.1186/s12913-018-3001-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sirilak S, Okanurak K, Wattanagoon Y, et al. . Community participation of cross-border migrants for primary health care in Thailand. Health Policy Plan 2013;28:658–64. 10.1093/heapol/czs105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wasserman MR, Bender DE, Lee S-Y, et al. . Social support among Latina immigrant women: bridge persons as mediators of cervical cancer screening. J Immigr Minor Health 2006;8:67–84. 10.1007/s10903-006-6343-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Keith L, van Ginneken E. Restricting access to the NHS for undocumented migrants is bad policy at high cost. BMJ 2015;350:h3056. 10.1136/bmj.h3056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ministry of Health Malaysia Circular of the Director General of Health no.10/2001: guidelines for reporting illegal immigrants obtaining medical services at clinics and hospitals, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Malaysia Laws of. Act 153. Immigration Act 1959/63.

- 79.Edward J. Undocumented immigrants and access to health care: making a case for policy reform. Policy Polit Nurs Pract 2014;15:5–14. 10.1177/1527154414532694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zainal F. Immigration D-G: detainees treated humanely fed proper food. The Star Monday 2019;08. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Abubakar I, Aldridge RW, Devakumar D, et al. . The UCL-Lancet Commission on migration and health: the health of a world on the move. Lancet 2018;392:2606–54. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Global Detention Project Malaysia: issues related to immigration detention. submission to the universal periodic review of the human rights Council, Malaysia, 31st session, November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 83.United Nations International convention on the protection of the rights of all migrant workers and members of their families, 1990. Available: https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-13&chapter=4&clang=_en [Accessed 24 Nov 2018]. [PubMed]

- 84.UN General Assembly Universal declaration of human rights. 302 UN General Assembly, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- 85.UN General Assembly International covenant on civil and political rights (ICCPR): A/RES/21, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Filges T, Montgomery E, Kastrup M. The impact of detention on the health of asylum seekers: a systematic review. Research on Social Work Practice 2018;28:399–414. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Steel Z, Liddell BJ, Bateman-Steel CR, et al. . Global protection and the health impact of migration interception. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001038. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.von Werthern M, Robjant K, Chui Z, et al. . The impact of immigration detention on mental health: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2018;18:382–82. 10.1186/s12888-018-1945-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.United Nations Human Rights Council Report of the Working group on arbitrary detention: Malaysia: United Nations General Assembly, Human Rights Council, sixteenth session agenda item 3, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Suhakam Annual report. Malaysia: Human Rights Commission of Malaysia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Barron L. Refugees describe death and despair in Malaysian detention centres. The Guardian, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Suhakam Roundtable on alternatives to immigration detention, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 93.United Nations General Assembly The United Nations standard minimum rules for the treatment of prisoners (the Nelson Mandela rules. Nations U ed, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Official Website Social Security Organisation Medical benefits: SOCSO, 2018. Available: https://www.perkeso.gov.my/index.php/en/medical-benefit

- 95.Scalabrini Migration Center, OECD Development Pathways . The Philippines’ migration landscape. Interrelations between public policies, migration and development in the Philippines Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jirattikorn A. Managing migration in Myanmar and Thailand: economic reforms, policies, practices and challenges. ISEAS Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chavez JJ. Social policy in ASEAN: the prospects for integrating migrant labour rights and protection. Global Social Policy 2007;7:358–78. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nodzenski M, Phua KH, Bacolod N. New Prospects in Regional Health Governance: Migrant Workers’ Health in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Asia Pac Policy Stud 2016;3:336–50. 10.1002/app5.113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.United Nations Treaty Collection United Nations treaty series online, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-039800supp001.pdf (68.1KB, pdf)