Abstract

Forensic entomology is the study of insects and other arthropods used in the solution of crimes. Most of entomological evidences strongly depend on accurate species identification. Therefore, new methods are being developed due to difficulties in morphological identification, including molecular methods such as High-Resolution Melting. In this study, we reported a new HRM primer set to identify forensically important Calliphoridae (blowflies) from Brazil. For such purpose, Calliphoridae species of forensic importance in Brazil were listed and confirmed by specialists. Mitochondrial COI sequences of those species were downloaded from databases and aligned, and polymorphic variations were selected for distinction between species. Based on it, HRM primers were designed. Forty-three fly samples representing six species were tested in the HRM assay. All samples had the COI gene sequenced to validate the result. Identifying and differentiating the six species proposed using a combination of two amplicons was possible. The protocol was effective even for old insect specimens, collected and preserved dried for more than ten years, unlike the DNA sequencing technique that failed for those samples. The HRM technique proved to be an alternative tool to DNA sequencing, with advantage of amplifying degraded samples and being fast and cheaper than the sequencing technique.

Keywords: Forensic entomology, Species identification, DNA Barcoding, BOLD, Melting curves, Diptera

Introduction

Morphology-based species identification, although widely used, may be difficult in cases of closely related species and damaged or degraded specimens (Galan, Pagès & Cosson, 2012; Sontigun et al., 2018b), and due to the lack of taxonomic keys and specialists (Chen, Hung & Shiao, 2004; Hebert, Ratnasingham & DeWaard, 2003). Technologies, such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), can help giving detailed information on the external morphological characteristics of the body and genitalia of adult blowflies and can help identify the immature forms (De Oliveira David, Rocha & Caetano, 2008; Mendonça et al., 2014a, 2014b; Sontigun et al., 2018a). The destruction of these characteristics, however, may lead to incorrect identification or non-identification (GilArriortua et al., 2014).

DNA barcoding, a powerful molecular tool, was created to overcome these barriers. Based on one or more standardized DNA regions—the mitochondrial Cytochrome Oxidase I gene (COI) in the case of animals (Hebert et al., 2003), and chloroplastidial and nuclear regions for plants (CBOL Plant Working Group, 2009; Kress et al., 2005) and fungi (Schoch et al., 2012)—barcoding allows identifying the species with enough accuracy and is applicable to many areas such as tracking of adulterations in food (Dawnay et al., 2016), beverages (De Castro et al., 2017), medicinal herbs (Bansal et al., 2018), identification of flies in forensic area (Jang et al., 2019; Oliveira et al., 2017; Rolo et al., 2013) and species that cannot be determined morphologically (Klippel et al., 2015), among others.

Insect specimens are used to estimate the post-mortem interval (PMI) in forensic entomology, which comprises the time from death to the discovery of the human corpse. It is based on the life cycle stage and the succession patterns of insects (Amendt, Krettek & Zehner, 2004; Catts & Goff, 1992). Furthermore, these insects are used to determine the cause of the death or whether the body was transported to a place other than that of death (Amendt et al., 2011; Zajac et al., 2016). The blowflies of family Calliphoridae (Insecta, Diptera) colonize the corpse before the other insects and provide most of the information about the PMI (Cooke et al., 2019). Families such as Muscidae, Sarcophagidae, Fanniidae and Phoridae are also forensically important, besides other insects of orders Coleoptera, the beetles, Hymenoptera, the wasps, ants and bees, and Lepidoptera, the butterflies (Amendt, Krettek & Zehner, 2004).

Usually, DNA barcoding technique uses fresh or preserved tissue samples to extract DNA since long amplicons are necessary (658 bp for COI, for example). However, in many circumstances, recovering sequences is not possible because only degraded DNA is available (Boyer et al., 2012), which is the major problem of specimens older than a decade (Hajibabaei et al., 2006). High resolution melting (HRM) analysis is an alternative method to sequencing to overcome this problem (Fernandes et al., 2017; Osathanunkul, Osathanunkul & Madesis, 2018). This is a RT-PCR-based and non-contaminated post-PCR technique that allows analyzing genetic variation in small PCR amplicons (usually 80–120 bp) by detecting small differences in the melting temperatures of the sequences through the melting curves (Wittwer, 2009; Wittwer et al., 2003). Furthermore, this method is cheaper and faster than Sanger sequencing, being a good alternative to be used by many laboratories (Wittwer, 2009). However, the scarcity or unavailability of HRM instruments can be a limitation of the technique. Although routinely qPCR instruments are designed to monitor fluorescence during DNA melting, not all allow performing the HRM analysis (Li et al., 2012). Also, the designed primers needs to follow some requirements to be successful, for example, amplification of short fragments, what can limit or hinder the application of HRM in some cases. Furthermore, some polymorphisms may not be distinguished by HRM, as there is a better differentiation between C/T and G/A or C/A and G/T than C/G or A/T (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, 2012; Słomka et al., 2017).

HRM is being used to identify a wide range of organisms such as animals (Klomtong, Phasuk & Duangjinda, 2016), plants (Mishra, Shukla & Sundaresan, 2018; Sun et al., 2016), fungi (Bezdicek et al., 2016), bacteria (Iacumin et al., 2015), and protozoa (Aghaei et al., 2014). In the specific case of insects, it was reported to identify forensic flies (Malewski et al., 2010) and mosquitos (Kang & Sim, 2013). However, the insect species addressed in each study are specific to each region of the planet. Thus, in this study, we reported a new HRM primer set to identify forensically important Calliphoridae (blowflies) in Brazil.

Materials and Methods

HRM primer design

Initially, Calliphoridae species forensically important in Brazil were listed based on literature and checked by specialists. Mitochondrial COI barcode sequences of those species were downloaded from BOLD Systems (available at www.boldsystems.org) (Ratnasingham & Hebert, 2007) (examples are shown in Supplemental File S2) and aligned through ClustalW in Bioedit software (Hall, 1999). Two regions containing polymorphic variations were selected for species distinction (Supplemental File S3). HRM primers were designed using Primer3 software (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3/) (Koressaar & Remm, 2007), flanking these regions and generating small amplicon sizes, as shown in Table 1. uMelt Melting Curve Predictions Software version 2.0.2 (available at https://www.dna-utah.org/umelt/um.php) was used to predict the melting temperature of each amplicon, enabling identifying each species based on its temperature variation.

Table 1. Primer sequences used in this study.

| Name | Direction | Sequence (5′→3′) | Ta (°C) | Amplicon size (bp) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRM_82F | Forward | AGTAGAAAATGGGGCTGGAA | 54 | 82 | This study |

| HRM_82R | Reverse | ATCAACTGATGCTCCTCCAT | |||

| HRM_124F | Forward | AATGTAATTGTAACAGCTCACG | 56 | 124 | This study |

| HRM_124R | Reverse | GTGGGAAAGCTATATCTGGAG | |||

| LCO-1490 | Forward | GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG | 51 | 658 | Folmer et al. (1994) |

| HCO-1490 | Reverse | TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAAT | |||

| C1-J-2495 | Forward | CAGCTACTTTATGAGCTTTAGG | 51 | 304 | Wells & Sperling (2001) |

| C1-N-2800 | Reverse | CATTTCAAGCTGTGTAAGCATC |

Sample and DNA isolation

For this study, 43 fly samples were used to validate the HRM assay. These samples included six Calliphoridae species (Chrysomya albiceps Wiedemann, 1819, Chrysomya megacephala Fabricius, 1794, Chrysomya putoria Wiedemann, 1830, Cochliomyia macellaria Fabricius, 1775, Lucilia cuprina Wiedemann, 1830, and Lucilia eximia Wiedemann, 1819), collected from different sites in Southeast Brazil, and identified through identification key (De Carvalho & De Mello-Patiu, 2008) and by the specialists Dr. Janyra Oliveira-Costa (Rio de Janeiro Scientific Police) and Dr. Patrícia Jacqueline Thyssen (Unicamp/São Paulo), as shown in the Supplemental File S1. Part of the samples had, approximately, eleven years of collection and was sent to us in dry conditions, another part had 6 years and was preserved in alcohol 70 °G.L and five fresh specimens of L. cuprina were supplied in absolute alcohol. Genomic DNA was isolated from 20 mg of thoracic muscles using NucleoSpin® Tissue Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Hoerdt, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentration and purity were evaluated using a NanoDrop™ 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). DNA samples were stored at −30 °C for further use.

PCR-HRM assay and data analysis

HRM with pre-amplification were performed on a LightCycler®96 real-time PCR instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Risch-Rotkreuz, Switzerland). The HRM-PCR reaction mixture (10 μL) contained 5 ng of genomic DNA, five µL of SsoFast™ EvaGreen® Supermix, 500 nM of each primer and ultrapure water up to the final volume. The samples were run in triplicate and a negative control was used in each experiment to exclude contamination. DNA amplification was achieved under the following conditions: first denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 54 and 56 °C, for 82 and 124 bp amplicon, respectively, for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. After amplification, PCR products were denatured at 95 °C for 1 min and renatured at 40 °C to form DNA duplexes. Melting curves were acquired by heating from 65 to 97 °C with 25 data acquisitions per degree. Data were analyzed using LightCycler®96 SW 1.1 version (Roche Diagnostics, Risch-Rotkreuz, Switzerland). Genotypes were identified by examining normalized melting curves, difference and derivative plots of the melting data. Melting temperature (Tm) data were statistically analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2010 and R statistical computing software (R Development Core Team, 2018) to the calculation of mean, standard deviation and confidence interval for each sample run in triplicate (Supplemental File S4).

DNA sequencing

Samples were previously sequenced to validate the results of HRM analysis. For this purpose, all samples were subjected to conventional PCR using universal COI primers. Table 1 shows an alternative primer pair to produce short fragment (385 bp) was used when universal primers failed. PCR products were purified using ExoSAP protocol. Sequencing was performed on an ABI 3500 DNA Sequencer (Thermo Fischer Scientific, USA) using BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit version 3.1 (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequences obtained were confronted with BOLD Systems (http://www.boldsystems.org) and GenBank to identify species. Similarity above 99% was considered identified.

Results and Discussion

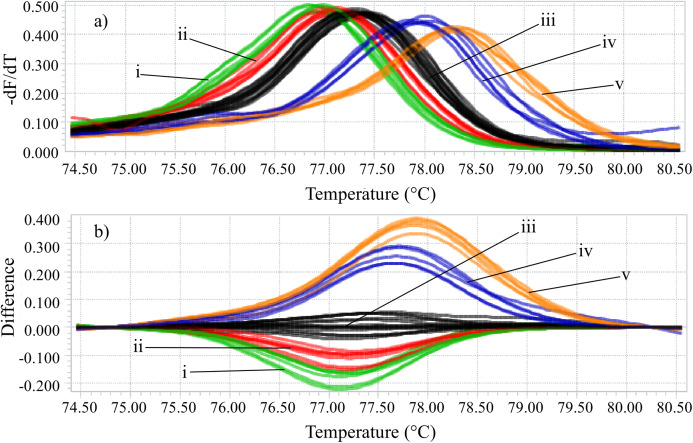

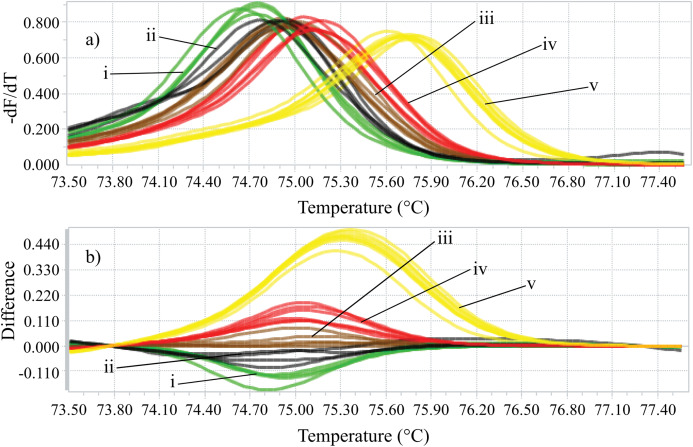

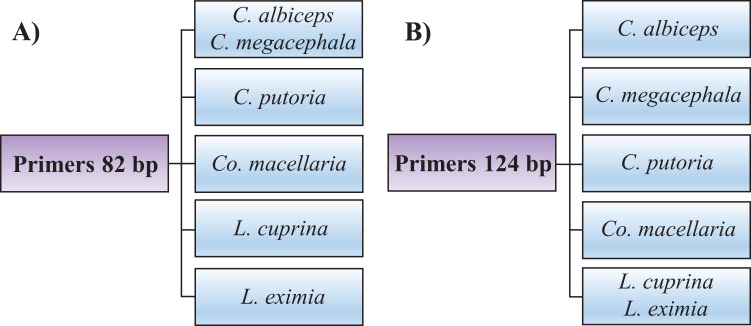

Identifying the six species proposed using two HRM amplicons was possible. Initially, an amplicon with 82 bp was used and the species L. eximia, L. cuprina, C. putoria, and Co. macellaria were distinguished, but C. megacephala and C. albiceps presented the same melting curves, as shown in Fig. 1. Complementarily, a second amplicon with 124 bp was used and it easily distinguished C. megacephala, Co. macellaria, C. albiceps, and C. putoria. The species L. cuprina and L. eximia could not be distinguished due to the similarity of their melting curves (Fig. 2). The second amplicon 124 bp allowed identifying the species that 82 bp amplicon could not differentiate (Fig. 3).

Figure 1. High-resolution melting analysis using COI primers (82 bp amplicon) for identification of Calliphoridae (blowflies) species.

(A) Normalized melting curves. (B) Difference plot curves using C. megacephala as reference genotype. Orange: L. eximia; Blue: L. cuprina; Black: C. megacephala and C. albiceps; Red: Co. macellaria; Green: C. putoria. (i) C. putoria; (ii) Co. macellaria; (iii) C. megacephala and C. albiceps; (iv) L. cuprina; (v) L. eximia.

Figure 2. High-resolution melting analysis using COI primers (124 bp amplicon) for forensic species.

(A) Normalized melting curves. (B) Difference plot curves using C. albiceps as reference genotype. Yellow: C. megacephala; Red: Co. macellaria; Brown: C. albiceps; Black: L. cuprina and L. eximia; Green: C. putoria. (i) C. putoria; (ii) L. cuprina and L. eximia; (iii) C. albiceps; (iv) Co. macellaria; (v) C. megacephala.

Figure 3. Flowchart showing species identification of blowflies using each of the HRM primers proposed, (A) 82 bp amplicon and (B) 124 bp amplicon.

The distinction of L. cuprina and L. eximia species by the 82 bp HRM amplicon was advantageous since most samples of L. eximia could not be amplified and sequenced using universal COI primers (658 bp fragment), only when we used a short fragment (385 bp). This fact led us to believe that L. eximia samples would be degraded (5 of 6 samples were in a dry state). Table 2 shows that the only L. eximia sample that could be identified by DNA sequencing was the one preserved in alcohol, which suggests DNA was probably degraded in those samples. DNA degradation could also explain why amplifying most of the old samples with the universal DNA barcoding primers was not possible (Hajibabaei et al., 2006). It also occured for old samples of C. albiceps and C. putoria. The amplification of large fragments does not occur when the DNA is broken in smaller fragments, but a shorter marker can be used for identification (Boyer et al., 2012).

Table 2. Percentage of samples with results using DNA sequencing and High-Resolution Melting when preservation condition and time since collection were analyzed.

| Condition | Number of samples | 650 bp fragment (%) | 300 bp fragment (%) | HRM 82 bp (%) | HRM 124 bp (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry | 13 | 0 | 100 | 92 | 46 |

| Alcohol | 25 | 100 | * | 92 | 80 |

| Fresh | 5 | 100 | * | 100 | 40 |

| Total | 43 | 68 | 30 | 91 | 65 |

| Ancient | 38 | 66 | * | 92 | 68 |

| Fresh | 5 | 100 | * | 100 | 40 |

| Total | 43 | 70 | 30 | 91 | 65 |

Note:

Samples sequenced only using 658 bp amplicon.

Our results confirmed the efficiency of alcohol 70 °G.L in the preservation of samples. The preservation in alcohol allowed the generation of DNA barcodes using the largest universal primers for 100% of the samples, even for old samples. This confirms that the use of this solvent can be an important ally in long-term conservation of flies, improving the sequence recovery rates (Elías-Gutiérrez et al., 2018). Similar results were also reported for other insects (Stein et al., 2013).

HRM was superior to DNA sequencing for dried (and possibly degraded) samples when the storage condition was considered, since each sample was amplified using the universal primers. The result was superior using 82 bp and similar using 124 bp amplicon in all of these samples, including the fresh samples and the samples preserved in alcohol. Thus, dry or degraded samples could be assayed with confidence by HRM.

The 82 bp amplicon showed to be effective for the molecular analysis of old specimens DNA with 92% of sample identification when the storage time was considered, while 124 bp amplicon identified only 68%. This 82 bp amplicon presented 92% of sample identification against 66% when compared with DNA sequencing. We only used specimens with more than a decade and degraded DNA to show HRM analysis is sufficient to distinguish species in difficult conditions.

Although DNA sequencing has been considered the best technique for species identification, it could not be efficient at identifying degraded samples amplifying large fragments. Moreover, this procedure is laborious and expensive. The HRM technique overcomes these problems since it can amplify and distinguish even species with degraded DNA (Boyer et al., 2012). This is a closed tube technique, reducing the contamination risks without using toxic reagents. In addition, the working time is short; sample analysis, detection of DNA polymorphisms, and distinctions between the melting curves can last about 2 h. Furthermore, HRM technique is cheaper than sequencing. Thus, adopting the HRM technique in laboratory routine and genetic studies is possible.

Conclusions

Our results support that the HRM analysis using our COI primer set is a powerful tool and sensitive technique for the identification and distinction of occurring Calliphoridae species in Brazil. The two amplicons designed can be reliably used to determine species identity, especially when morphological identification is not possible. Moreover, even ancient specimens collected and preserved dried for more than ten years, with possible degraded DNA, could be identified, unlike what occurs when using the DNA sequencing technique, which failed for those samples. New HRM assays should be performed in other blowfly forensic groups to facilitate the routine identification of species.

Supplemental Information

NRC = No Reference Cluster

Tm = melting temperature (mean of the samples run in triplicates)

SD = standard deviation

CI = confidence interval (95%)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Patrícia Jacqueline Thyssen for providing us with the samples used in this study, Dr. Márcia Flores da Silva Ferreira for the authorization to use the real time PCR equipment. We also thank the Graduate Program in Biotechnology of the Federal University of Espirito Santo, and group research, Geotechnology Applied to Global Environment (GAGEN).

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brazil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001, for the scholarship awarded to the Pablo Viana Oliveira. There was no additional external funding received for this study. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Pablo Viana Oliveira conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Francine Alves Nogueira de Almeida performed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Magda Delorence Lugon performed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Karolinni Bianchi Britto performed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Janyra Oliveira-Costa conceived and designed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Alexandre Rosa Santos analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Greiciane Gaburro Paneto conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed the data, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data are available as Supplemental Files and include Calliphoridae species samples and the COI sequences downloaded from BOLD Systems and GenBank (Table S2).

References

- Aghaei et al. (2014).Aghaei AA, Rassi Y, Sharifi I, Vatandoost H, Mollaie HR, Oshaghi MA, Abai MR, Rafizadeh S. First report on natural Leishmania infection of Phlebotomus sergenti due Leishmania tropica by high resolution melting curve method in South-eastern Iran. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2014;7(2):93–96. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amendt, Krettek & Zehner (2004).Amendt J, Krettek R, Zehner R. Forensic entomology. Naturwissenschaften. 2004;91(2):51–65. doi: 10.1007/s00114-003-0493-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amendt et al. (2011).Amendt J, Richards CS, Campobasso CP, Zehner R, Hall MJR. Forensic entomology: applications and limitations. Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology. 2011;7(4):379–392. doi: 10.1007/s12024-010-9209-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal et al. (2018).Bansal S, Thakur S, Mangal M, Mangal AK, Gupta R. DNA barcoding for specific and sensitive detection of Cuminum cyminum adulteration in Bunium persicum. Phytomedicine. 2018;50:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezdicek et al. (2016).Bezdicek M, Lengerova M, Ricna D, Weinbergerova B, Kocmanova I, Volfova P, Drgona L, Poczova M, Mayer J, Racil Z. Rapid detection of fungal pathogens in bronchoalveolar lavage samples using panfungal PCR combined with high resolution melting analysis. Medical Mycology. 2016;54(7):714–724. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myw032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer et al. (2012).Boyer S, Brown SDJ, Collins RA, Cruickshank RH, Lefort M-C, Malumbres-Olarte J, Wratten SD, Crandall KA. Sliding window analyses for optimal selection of mini-barcodes, and application to 454-pyrosequencing for specimen identification from degraded DNA. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(5):e38215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catts & Goff (1992).Catts EP, Goff ML. Forensic entomology in criminal investigations. Annual Review of Entomology. 1992;37(1):253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.37.010192.001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CBOL Plant Working Group (2009).CBOL Plant Working Group A DNA barcode for land plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(31):12794–12797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905845106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Hung & Shiao (2004).Chen W-Y, Hung T-H, Shiao S-F. Molecular identification of forensically important blow fly species (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in Taiwan. Journal of Medical Entomology. 2004;41(1):47–57. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke et al. (2019).Cooke T, Kulenkampff K, Heyns M, Heathfield LJ. DNA barcoding of forensically important flies in the Western Cape, South Africa. Genome. 2019;61(12):823–828. doi: 10.1139/gen-2018-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawnay et al. (2016).Dawnay N, Hughes R, Court DS, Duxbury N. Species detection using HyBeacon probe technology: working towards rapid onsite testing in non-human forensic and food authentication applications. Forensic Science International: Genetics. 2016;20:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Carvalho & De Mello-Patiu (2008).De Carvalho CJB, De Mello-Patiu CA. Key to the adults of the most common forensic species of Diptera in South America. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia. 2008;52(3):390–406. doi: 10.1590/S0085-56262008000300012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Castro et al. (2017).De Castro O, Comparone M, Di Maio A, Del Guacchio E, Menale B, Troisi J, Aliberti F, Trifuoggi M, Guida M. What is in your cup of tea? DNA verity test to characterize black and green commercial teas. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(5):e0178262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira David, Rocha & Caetano (2008).De Oliveira David JA, Rocha T, Caetano FH. Ultramorphological characteristics of Chrysomya megacephala (Diptera, Calliphoridae) eggs and its eclosion. Micron. 2008;39(8):1134–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elías-Gutiérrez et al. (2018).Elías-Gutiérrez M, Valdez-Moreno M, Topan J, Young MR, Cohuo-Colli JA. Improved protocols to accelerate the assembly of DNA barcode reference libraries for freshwater zooplankton. Ecology and Evolution. 2018;8(5):3002–3018. doi: 10.1002/ece3.3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes et al. (2017).Fernandes TJR, Costa J, Oliveira MBPP, Mafra I. COI barcode-HRM as a novel approach for the discrimination of hake species. Fisheries Research. 2017;197(April):50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2017.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folmer et al. (1994).Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Molecular Marine Biology and Biotechnology. 1994;3(5):294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan, Pagès & Cosson (2012).Galan M, Pagès M, Cosson J-F. Next-generation sequencing for rodent barcoding: species identification from fresh, degraded and environmental samples. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(11):e48374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GilArriortua et al. (2014).GilArriortua M, Saloña Bordas MI, Köhnemann S, Pfeiffer H, De Pancorbo MM. Molecular differentiation of Central European blowfly species (Diptera, Calliphoridae) using mitochondrial and nuclear genetic markers. Forensic Science International. 2014;242:274–282. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajibabaei et al. (2006).Hajibabaei M, Smith MA, Janzen DH, Rodriguez JJ, Whitfield JB, Hebert PDN. A minimalist barcode can identify a specimen whose DNA is degraded. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2006;6(4):959–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2006.01470.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall (1999).Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hebert et al. (2003).Hebert PDN, Cywinska A, Ball SL, DeWaard JR. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2003;270(1512):313–321. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert, Ratnasingham & DeWaard (2003).Hebert PDN, Ratnasingham S, DeWaard JR. Barcoding animal life: cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 divergences among closely related species. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2003;270:S96–S99. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacumin et al. (2015).Iacumin L, Ginaldi F, Manzano M, Anastasi V, Reale A, Zotta T, Rossi F, Coppola R, Comi G. High resolution melting analysis (HRM) as a new tool for the identification of species belonging to the Lactobacillus casei group and comparison with species-specific PCRs and multiplex PCR. Food Microbiology. 2015;46:357–367. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang et al. (2019).Jang H, Shin SE, Ko KS, Park SH. SNP typing using multiplex real-time PCR assay for species identification of forensically important blowflies and fleshflies collected in South Korea (Diptera: Calliphoridae and Sarcophagidae) BioMed Research International. 2019;2019(2):1–11. doi: 10.1155/2019/6762517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang & Sim (2013).Kang D, Sim C. Identification of Culex complex species using SNP markers based on high-resolution melting analysis. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2013;13(3):369–376. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klippel et al. (2015).Klippel AH, Oliveira PV, Britto KB, Freire BF, Moreno MR, Dos Santos AR, Banhos A, Paneto GG. Using DNA barcodes to identify road-killed animals in two atlantic forest nature reserves, Brazil. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0134877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klomtong, Phasuk & Duangjinda (2016).Klomtong P, Phasuk Y, Duangjinda M. Animal species identification through high resolution melting real time PCR (HRM) of the Mitochondrial 16S RRNA gene. Annals of Animal Science. 2016;16(2):415–424. doi: 10.1515/aoas-2015-0074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koressaar & Remm (2007).Koressaar T, Remm M. Enhancements and modifications of primer design program Primer3. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(10):1289–1291. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress et al. (2005).Kress WJ, Wurdack KJ, Zimmer EA, Weigt LA, Janzen DH. Use of DNA barcodes to identify flowering plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(23):8369–8374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503123102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al. (2012).Li F, Niu B, Huang Y, Meng Z. Application of high-resolution DNA melting for genotyping in lepidopteran non-model species: Ostrinia furnacalis (crambidae) PLOS ONE. 2012;7(1):e29664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malewski et al. (2010).Malewski T, Draber-Mońko A, Pomorski J, Łoś M, Bogdanowicz W. Identification of forensically important blowfly species (Diptera: Calliphoridae) by high-resolution melting PCR analysis. International Journal of Legal Medicine. 2010;124(4):277–285. doi: 10.1007/s00414-009-0396-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendonça et al. (2014a).Mendonça PM, Barbosa RR, Carriço C, Cortinhas LB, Dos Santos-Mallet JR, De Queiroz MMC. Ultrastructure of immature stages of Lucilia cuprina (Diptera: Calliphoridae) using scanning electron microscopy. Acta Tropica. 2014a;136(1):123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendonça et al. (2014b).Mendonça PM, Barbosa RR, Cortinhas LB, Dos Santos-Mallet JR, De Carvalho Queiroz MM. Ultrastructure of immature stages of Cochliomyia macellaria (Diptera: Calliphoridae), a fly of medical and veterinary importance. Parasitology Research. 2014b;113(10):3675–3683. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-4032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, Shukla & Sundaresan (2018).Mishra P, Shukla AK, Sundaresan V. Candidate DNA Barcode tags combined with high resolution melting (Bar-HRM) curve analysis for authentication of Senna alexandrina mill, with validation in crude drugs. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2018;9(283):288. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira et al. (2017).Oliveira PV, Matos NS, Klippel AH, Oliveira-Costa J, Careta FP, Paneto GG. Using DNA barcodes to identify forensically important species of Diptera in Espírito Santo state. Brazil Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology. 2017;60(e160106):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Osathanunkul, Osathanunkul & Madesis (2018).Osathanunkul M, Osathanunkul R, Madesis P. Species identification approach for both raw materials and end products of herbal supplements from Tinospora species. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2018;18(111):e84291. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2174-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team (2018).R Development Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: The R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ratnasingham & Hebert (2007).Ratnasingham S, Hebert PDN. BOLD: the barcode of life data system (www.barcodinglife.org) Molecular Ecology Notes. 2007;7(3):355–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01678.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche Diagnostics GmbH (2012).Roche Diagnostics GmbH LightCycler® 96 Operator’s Guide. 2012. https://lifescience.roche.com/documents/LightCycler96_Manual_Version2016.pdf https://lifescience.roche.com/documents/LightCycler96_Manual_Version2016.pdf Chapter A: System description. In: LightCycler® 96 Instrument.

- Rolo et al. (2013).Rolo EA, Oliveira AR, Dourado CG, Farinha A, Rebelo MT, Dias D. Identification of sarcosaprophagous Diptera species through DNA barcoding in wildlife forensics. Forensic Science International. 2013;228(1–3):160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch et al. (2012).Schoch CL, Seifert KA, Huhndorf S, Robert V, Spouge JL, Levesque CA, Chen W, Fungal Barcoding Consortium Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(16):6241–6246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117018109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontigun et al. (2018a).Sontigun N, Sanit S, Wannasan A, Sukontason K, Amendt J, Yasanga T, Sukontason KL. Ultrastructure of male genitalia of blow flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) of forensic importance. Acta Tropica. 2018a;179:61–80. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontigun et al. (2018b).Sontigun N, Sukontason K, Amendt J, Zajac B, Zehner R, Sukontason K, Chareonviriyaphap T, Wannasan A. Molecular analysis of forensically important blow flies in Thailand. Insects. 2018b;9(159):159. doi: 10.3390/insects9040159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein et al. (2013).Stein ED, White BP, Mazor RD, Miller PE, Pilgrim EM. Evaluating ethanol-based sample preservation to facilitate use of DNA barcoding in routine freshwater biomonitoring programs using benthic macroinvertebrates. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(1):e51273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun et al. (2016).Sun W, Li J, Xiong C, Zhao B, Chen S. The potential power of bar-HRM technology in herbal medicine identification. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2016;7:367. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Słomka et al. (2017).Słomka M, Sobalska-Kwapis M, Wachulec M, Bartosz G, Strapagiel D. High resolution melting (HRM) for high-throughput genotyping-limitations and caveats in practical case studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017;18(11):2316. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells & Sperling (2001).Wells JD, Sperling FAH. DNA-based identification of forensically important Chrysomyinae (Diptera: Calliphoridae) Forensic Science International. 2001;120(1–2):110–115. doi: 10.1016/S0379-0738(01)00414-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittwer (2009).Wittwer CT. High-resolution DNA melting analysis: advancements and limitations. Human Mutation. 2009;30(6):857–859. doi: 10.1002/humu.20951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittwer et al. (2003).Wittwer CT, Reed G, Gundry CN, Vandersteen JG, Pryor RJ. High-resolution genotyping by amplicons melting analysis using LCGreen. Clinical Chemistry. 2003;49(6):853–860. doi: 10.1373/49.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajac et al. (2016).Zajac BK, Sontigun N, Wannasan A, Verhoff MA, Sukontason K, Amendt J, Zehner R. Application of DNA barcoding for identifying forensically relevant Diptera from northern Thailand. Parasitology Research. 2016;115(6):2307–2320. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-4977-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

NRC = No Reference Cluster

Tm = melting temperature (mean of the samples run in triplicates)

SD = standard deviation

CI = confidence interval (95%)

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data are available as Supplemental Files and include Calliphoridae species samples and the COI sequences downloaded from BOLD Systems and GenBank (Table S2).