Summary

Lymphotoxin β-receptor (LTβR)-signalling orchestrates lymphoid neogenesis and subsequent tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS)1,2, associated with severe chronic inflammatory diseases spanning multiple organ systems3–6. How LTβR-signalling drives chronic tissue damage particularly in the lung, which mechanism(s) regulate this process, and whether LTβR-blockade might be of therapeutic value has remained unclear. Here we demonstrate increased expression of LTβR-ligands on adaptive and innate immune-cells, enhanced non-canonical NF-κB signalling and enriched LTβR-target gene expression in epithelial cells of lungs from patients with smoking-associated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and mice exposed to chronic cigarette smoke. Therapeutic inhibition of LTβR-signalling in young and aged mice disrupted smoking-related inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT), induced lung tissue regeneration, and reverted airway-fibrosis and systemic muscle wasting. Mechanistically, LTβR-signalling blockade dampened epithelial non-canonical NF-κB activation, reduced TGFβ-signalling in airways, induced regeneration by preventing epithelial cell-death and by activating Wnt/β-catenin-signalling in alveolar epithelial progenitor cells. These findings highlight that LTβR-signalling inhibition represents a viable therapeutic option combining anti-TLS, anti-apoptotic with tissue regenerative strategies.

Endogenous regenerative mechanisms of the lung are severely compromised in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the third leading cause of death worldwide7 with limited therapeutic options8. Consequently, the identification and therapeutic use of endogenous regenerative mechanisms is an important paradigm shift in our understanding and potential treatment of COPD9. Importantly, immune cells infiltrating the COPD lung are organized into tertiary lymphoid structures called inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT), which are observed during lung tissue destruction (emphysema) in both humans3,10–12 and mice13,14. iBALT formation requires the interaction of lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR) on stromal organizer cells with TNF superfamily members lymphotoxin α (LTα) and β (LTβ)1,2, expressed by activated lymphocytes during chronic inflammation15,16. LTβR stimulation subsequently triggers downstream non-canonical NF-κB signalling via the activation of NIK (NF-κB inducing kinase)17,18. However, the role of LTβR-signalling - in the development of lung tissue injury remains unexplored.

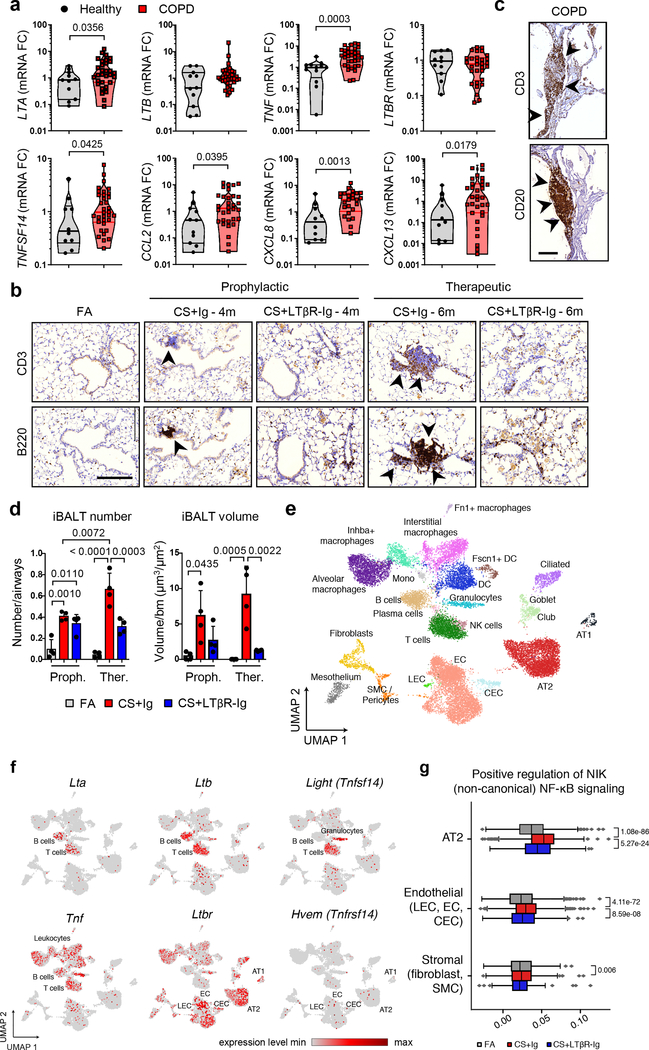

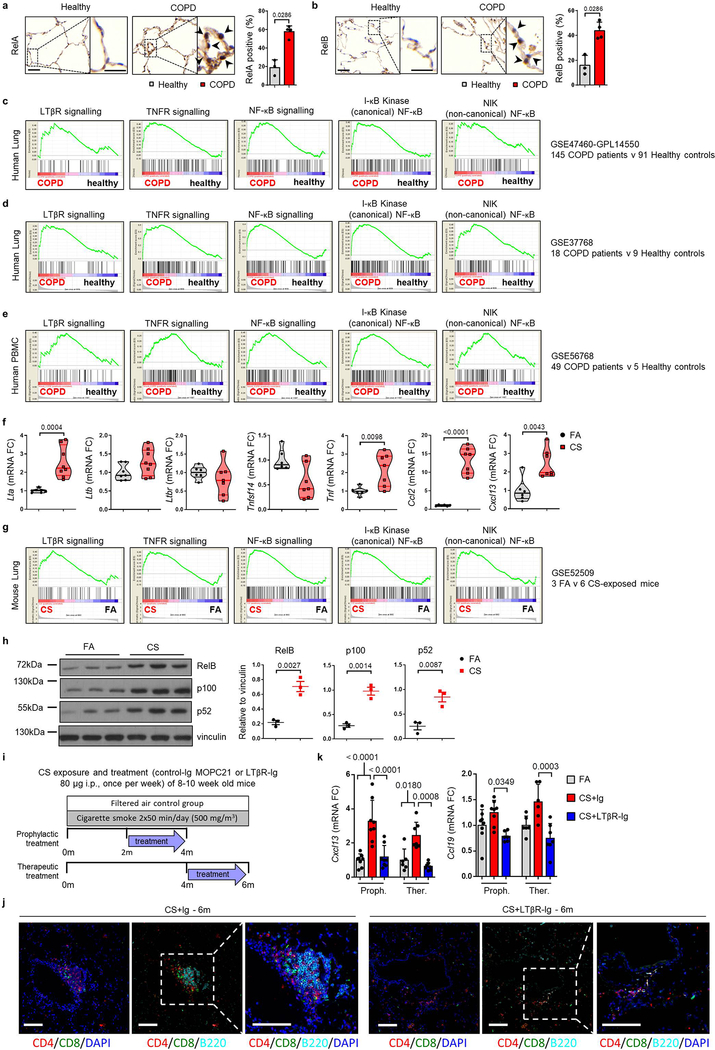

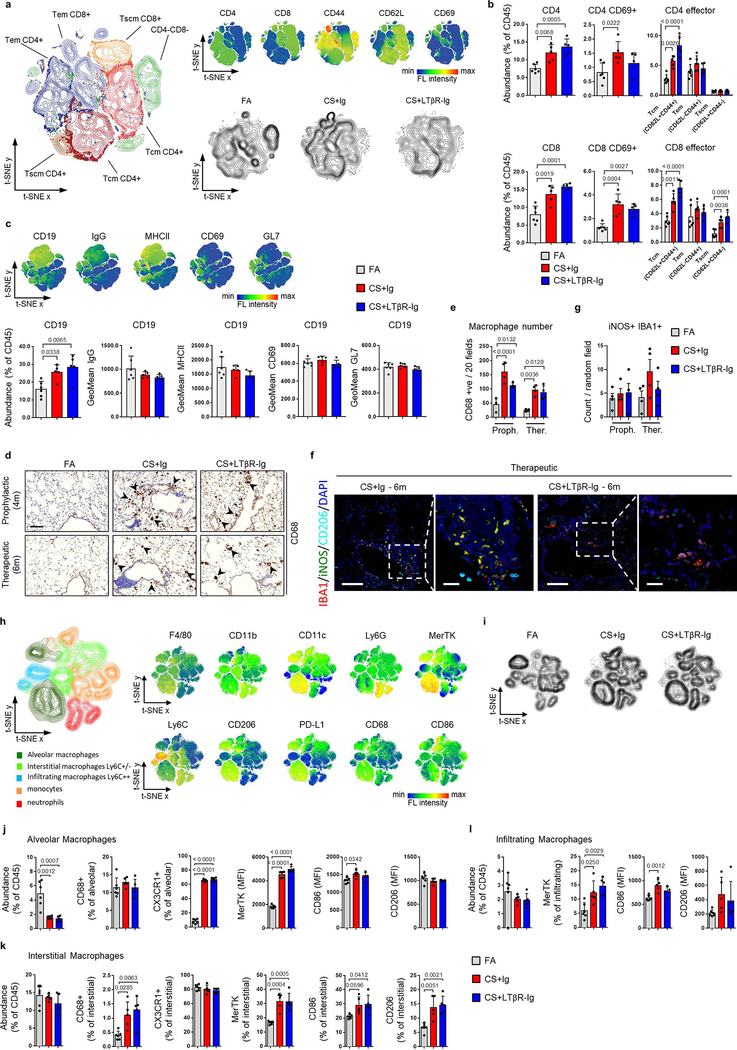

Analysis of lung samples from COPD patients revealed increased expression of signalling molecules LTA, TNFSF14 (LIGHT) and TNF, and downstream chemokines CCL2, CXCL8 and CXCL13 (Fig. 1a), mediated through increased nuclear translocation of NF-κB-associated transcription factors RelA and RelB in lung epithelium (Extended Data Fig. 1a–b). To validate, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of lung transcriptomic data from COPD patients (GSE47460 and GSE37768). Revealing enrichment of both, LTβR- and TNFR-signalling pathways, accompanied by enhanced IKK-dependent canonical and NIK-dependent non-canonical NF-κB signalling in COPD lungs (Extended Data Fig. 1c–d). Interestingly, similar enrichment was also found in PBMCs from COPD patients (GSE56768; Extended Data Fig. 1e). Similarly, mice exposed to chronic cigarette smoke (CS) for 6m displayed increased mRNA expression of Lta, Tnf, Ccl2 and Cxcl13 in lung tissue (Extended Data Fig. 1f). Furthermore, GSEA of our transcriptomics data set (GSE52509) demonstrated enrichment of LTβR-, TNFR- and both canonical and non-canonical NF-κB-signalling pathways in lungs of CS-exposed mice (Extended Data Fig. 1g), accompanied by increased protein levels of RelB, p100 and its cleaved product p52 (Extended Data Fig. 1h). Next, we analysed whether inhibition of LTβR-signalling might impair iBALT formation by applying distinct treatment strategies using a LTβR-Ig fusion protein19,20 (Extended Data Fig. 1i). CS exposure resulted in the development of iBALT, composed predominantly of organised B cell and T cell-clusters as early as 4m (Fig. 1b), reminiscent to that observed in COPD patients (Fig. 1c). LTβR-Ig treatment - in the presence of CS - led to significantly reduced iBALT formation with dispersed immune cells (Fig. 1b, d and Extended Data Fig. 1j), accompanied by a reduction of LTβR-signalling downstream targets, Cxcl13 and Ccl19 (Extended Data Fig. 1k). The effect of LTβR-Ig treatment was specific to a reduction in iBALT-incidence as multicolour flow cytometric analysis of adaptive immune cells revealed no significant effect upon their abundance or activation status (Extended data Fig. 2a–c). Furthermore, macrophages were not significantly reduced in the lungs of CS+LTβR-Ig compared to CS+Ig treated mice (Extended Data Fig. 2d–e). Multiplex immunofluorescence analysis suggested only subtle differences in myeloid populations upon LTβR-Ig treatment, a trend towards reduction was found in iNOS+ IBA1+ macrophages upon therapeutic LTβR-Ig treatment (Extended Data Fig. 2f–g). Multicolour flow cytometric analysis of interstitial macrophages in particular, revealed that both abundance and expression of inflammatory CD86+ and immune-modulatory CD206+ macrophage populations induced by CS-exposure were not reduced following therapeutic treatment with LTβR-Ig (Extended Data Fig. 2h–l).

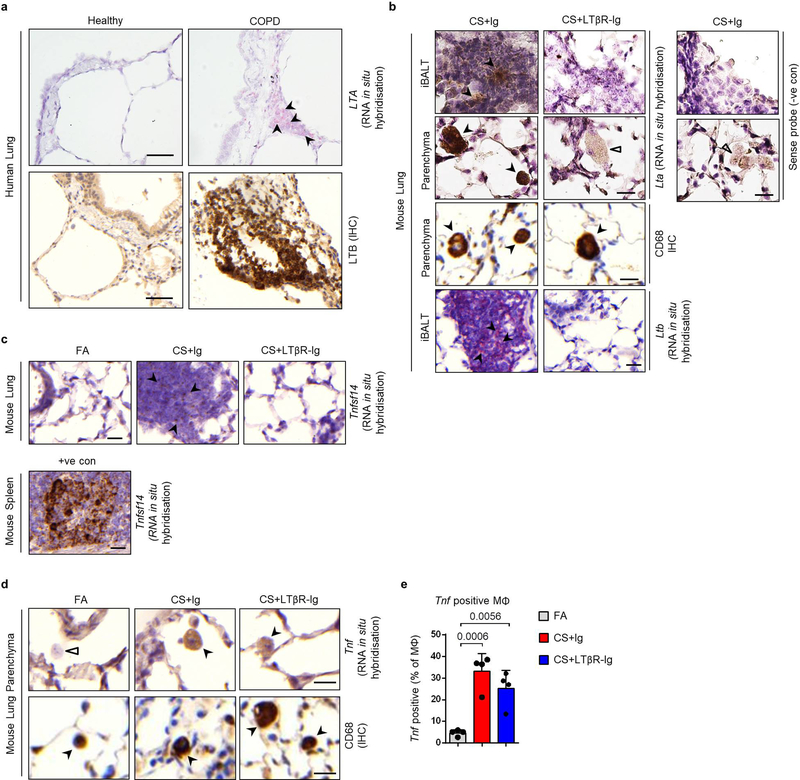

Fig. 1. LTβR-signalling is activated in COPD and inhibition disrupts iBALT in the lungs of CS-exposed mice.

a, mRNA expression levels of genes indicated determined by qPCR in lung core biopsies from healthy (n=11) and COPD patients (n=32). b, Representative images of immunohistochemical analysis for B220+ B cells and CD3+ T cells (brown signal, arrows, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 200μm) in lung sections from B6 mice exposed to FA or CS for 4m and 6m, plus LTβR-Ig or control Ig prophylactically from 2m - 4m (CS + LTβR-Ig – 4m) and therapeutically from 4m - 6m (CS + LTβR-Ig – 6m), see Extended Data Fig. 1i. (n=4 mice/group, repeated twice). c, Representative lung sections from COPD patients stained for CD20+ B cells and CD3+ T cells (brown signal, arrows, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 200μm, n=4). d, Quantification of lung iBALT from mice described in (b), as mean iBALT number/airway and volume of iBALT normalised to surface area of airway basement membrane (bm), data shown mean ± SD (n=4 mice/group, repeated twice, Proph., prophylactic; Ther., therapeutic). e-g, Cells from whole lung suspensions of B6 mice exposed to FA (n=3) or CS for 6m, plus LTβR-Ig (n=5) or control Ig (n=5) therapeutically, were analysed at 6m by scRNA-Seq (Drop-Seq). e, UMAP of scRNA-Seq profiles (dots) coloured by cell type. f, UMAP plots showing expression of genes indicated in scRNA-Seq profiles. g, Box and whiskers plot (box 25th-75th percentile, median line indicated and whiskers representing +/− 1.5 IQR) showing relative score for positive regulation of NIK (non-canonical) NFκB signalling pathway (GO:1901224) in cells indicated. Statistical significance indicated and was assessed using Wilcoxon rank-sum test on normalized, log transformed count values and corrected with Benjamini-Hochberg (g). P values indicated, Mann-Whitney one-sided test (a) and one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons Bonferroni test (g).

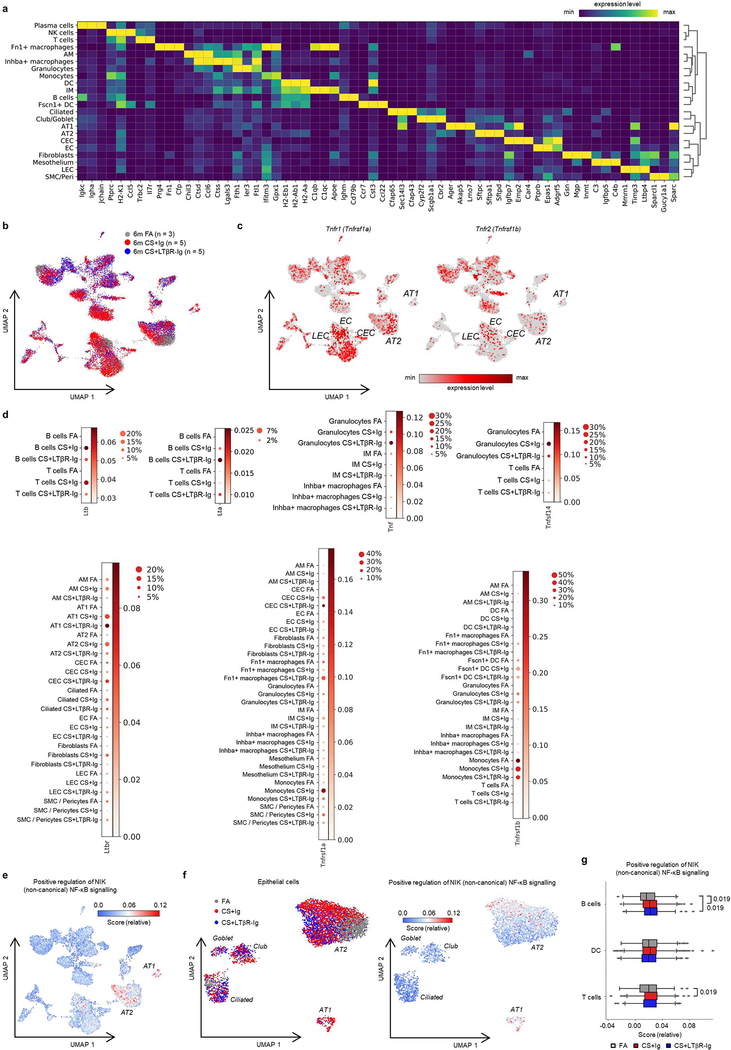

To further elucidate the cellular and molecular consequences of LTβR-inhibition, we investigated single cell RNA-Seq together with bulk transcriptomic and proteomic analyses. We grouped single cell transcriptomes from whole mouse lung tissue into 24 cell identities and observed cell type specific changes occurring upon CS exposure and LTβR-Ig treatment (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 3a–d). Lta and Ltb expression localised mainly to B and T cells, Tnfsf14 (an alternative LTβR ligand) to T cells and granulocytes, while Tnf was expressed by all leucocytes in the lung (Fig. 1f). Expression of Ltb but not Tnf was reduced upon LTβR-Ig treatment (Extended Data Fig. 3d), validated by cellular localization with in situ hybridisation and IHC (Extended data Fig. 4a–e). Concomitant with disease progression CS strongly induced a positive regulation of NIK-dependent non-canonical NF-κB signalling in alveolar epithelial type 2 (AT2) cells, which was significantly reduced upon LTβR-Ig treatment (Fig. 1g and Extended Data Fig. 3e–g). We found high levels of Ltbr mRNA expression on AT2 cells (Fig. 1f) indicating that NIK dependent NF-κB-signalling in AT2 cells can be triggered by LTβR-activation. In contrast, expression of Hvem, an additional receptor for Tnfsf14, was hardly detectable in lung tissue (Fig. 1f).

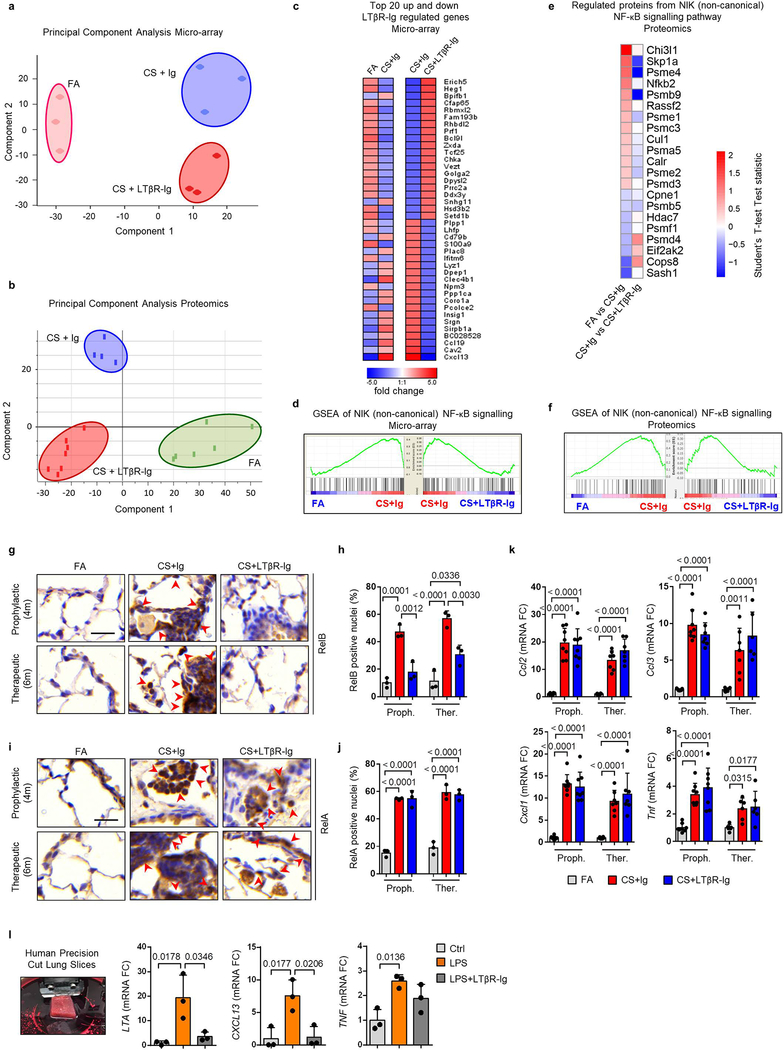

Bulk level principle component analyses revealed a distinct change in the lung transcriptome (Extended Data Fig. 5a) and proteome (Extended Data Fig. 5b) of CS+LTβR-Ig compared to CS+Ig treated mice, with non-canonical NF-κB targets Cxcl13 and Ccl19 to be amongst the most down regulated following LTβR-Ig treatment (Extended Data Fig. 5c). GSEA confirmed NIK-associated non-canonical NF-κB signalling to be reversed by LTβR-Ig treatment at transcriptomic and proteomic level (Extended Data Fig. 5d–f). LTβR-Ig treatment reduced CS-induced elevations of nuclear translocation of RelB in lung epithelial cells (Extended Data Fig. 5g–h). In contrast, nuclear translocation of RelA in lung epithelial cells was not affected upon LTβR-Ig treatment (Extended Data Fig. 5i–j), along with canonical NF-κB regulated genes Ccl2, Ccl3, Cxcl1 and Tnf (Extended Data Fig. 5k). Moreover, we demonstrated the clinical relevance of these findings by modelling COPD inflammation in human precision-cut lung slices (PCLS) ex vivo21,22. LPS stimulation resulted in increased expression of LTA, TNF and CXCL13, and treatment with human LTβR-Ig reversed the increase in LTA and CXCL13 but not canonical NF-κB-regulated TNF (Extended Data Fig. 5l). These data indicate that disruption of the LTβR-signalling pathway reverses CS-induced iBALT formation and modulates non-canonical NF-κB signalling in lung tissue.

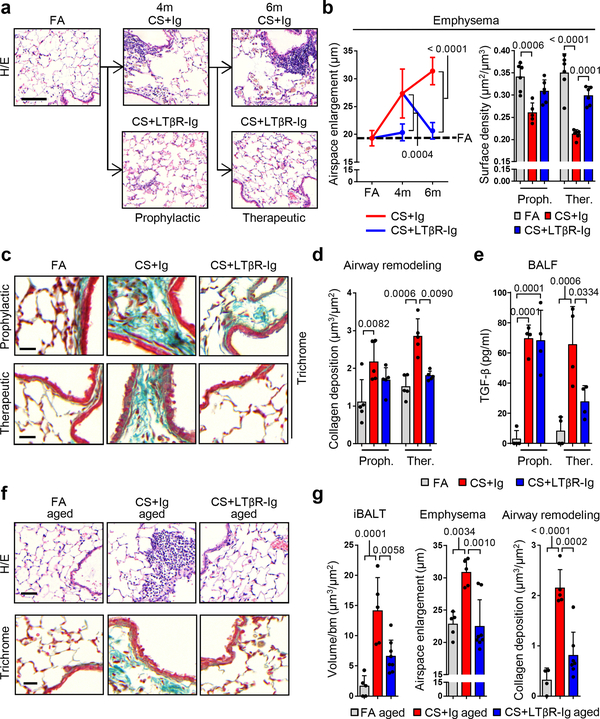

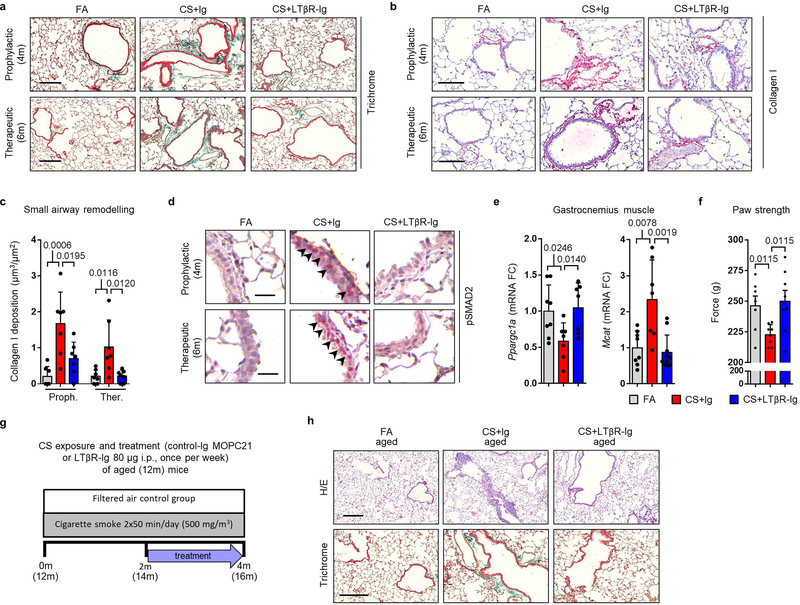

We next assessed whether reduction in LTβR-signalling and diminution of iBALT affected CS-associated lung pathogenesis. Quantitative morphological analyses of lung tissue damage (Fig. 2a) for airspace enlargement and alveolar surface density revealed that CS-induced emphysema was prevented by prophylactic LTβR-Ig treatment (Fig. 2b). Therapeutic treatment starting from 4m, a time point at which airspace damage was already fully established in mice14, led to full restoration of lung tissue - even under concomitant CS exposure (Fig. 2b). Further, quantification of collagen deposition around the airways, particularly the accumulation of collagen I, revealed that LTβR-Ig treatment is protective in the prophylactic group (Fig. 2c–d and Extended Data Fig. 6a–c) and induced regression of CS-mediated airway remodelling in the therapeutic group (Fig. 2c–d and Extended Data Fig. 6a–c). Airway remodelling processes are mediated via TGF-β signalling, propagated through phosphorylation of the receptor-regulated Smads23. In line, staining for phosphorylated Smad2 revealed high levels in airway epithelial cells of CS-exposed mice, which was strongly reduced following LTβR-Ig (Extended Data Fig. 6d). Importantly, levels of active TGF-β in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid increased following CS-exposure (Fig. 2e), and was reversed after therapeutic LTβR-Ig treatment.

Fig. 2. LTβR-Ig reverses emphysema in chronic CS-exposed young and aged mice.

a, Representative images of H/E stained lung sections (scale bar 100μm) from B6 mice exposed to FA or CS for 4m and 6m, plus LTβR-Ig or control Ig prophylactically from 2m - 4m analysed at 4m, and therapeutically from 4m - 6m analysed at 6m, see Extended Data Fig. 1i. (n=6 mice FA, 5 mice CS+Ig, 6 mice CS+LTβR-Ig groups, repeated twice). b, Quantification of airspace enlargement as mean chord length and alveolar surface area in lung sections from mice in (a) (n=6 mice FA, 5 mice CS+Ig, 6 mice CS+LTβR-Ig groups, repeated twice, Proph., prophylactic; Ther., therapeutic). c, Representative images of Masson’s Trichrome stained lung sections (scale bar 25μm) from mice in (a), (n=5 mice FA, 5 mice CS+Ig, 5 mice CS+LTβR-Ig groups, repeated twice). d, Quantification of airway collagen deposition normalised to surface area of airway basement membrane (bm) from sections in (c), (n=5 mice FA, 5 mice CS+Ig, 5 mice CS+LTβR-Ig groups, repeated twice). e, TGF-β levels determined by ELISA in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of mice described in (a) (n=4 mice FA, 4 mice CS+Ig, 4 mice CS+LTβR-Ig groups, repeated twice). f, Representative images of H/E and Masson’s Trichrome stained lung sections (scale bar 50μm) from 12m old B6 mice exposed to FA or CS for 4m, plus LTβR-Ig or control Ig from 2m – 4m and analysed at 4m, see Extended Data Fig. 6g. (n=5 mice FA, 5 mice CS+Ig, 8 mice CS+LTβR-Ig groups, repeated twice). g, Quantification of lung iBALT as volume of iBALT normalised to surface area of airway bm, quantification of airspace enlargement as mean chord length, from H/E sections in (f) and quantification of airway collagen deposition normalised to surface area of airway bm from Masson’s Trichrome sections in (f) (n=5 mice FA, 5 mice CS+Ig, 8 mice CS+LTβR-Ig groups, repeated twice). Data shown mean ± SD. P values indicated, one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons Bonferroni test.

COPD is further characterized by comorbidities, most prominently muscle wasting24. Thus, we analysed the systemic responses to therapeutic LTβR-Ig treatment in mice. Transcriptomic analysis of the gastrocnemius muscle suggested CS-induced modulation of Ppargc1a and Mcat25,26 were reversed following LTβR-Ig treatment (Extended Data Fig. 6e). Furthermore, a functional 4-paw muscle strength test revealed a significant deficit in mice after 6m CS exposure, which could be fully reversed upon LTβR-Ig treatment (Extended Data Fig. 6f).

We have previously shown that aged mice are predisposed to earlier development of CS-induced airway remodelling and emphysema via iBALT driven immune-aging27. To determine whether findings of this study are age-independent, we exposed aged mice (12m) to CS for 4m total, combined with therapeutic LTβR-Ig treatment under CS for 2m (Extended Data Fig. 6g). CS induced iBALT, emphysema, and airway remodelling were also prevented by LTβR-Ig treatment in aged mice (Fig. 2f–g and Extended Data Fig. 6h), indicating that our findings are age-independent.

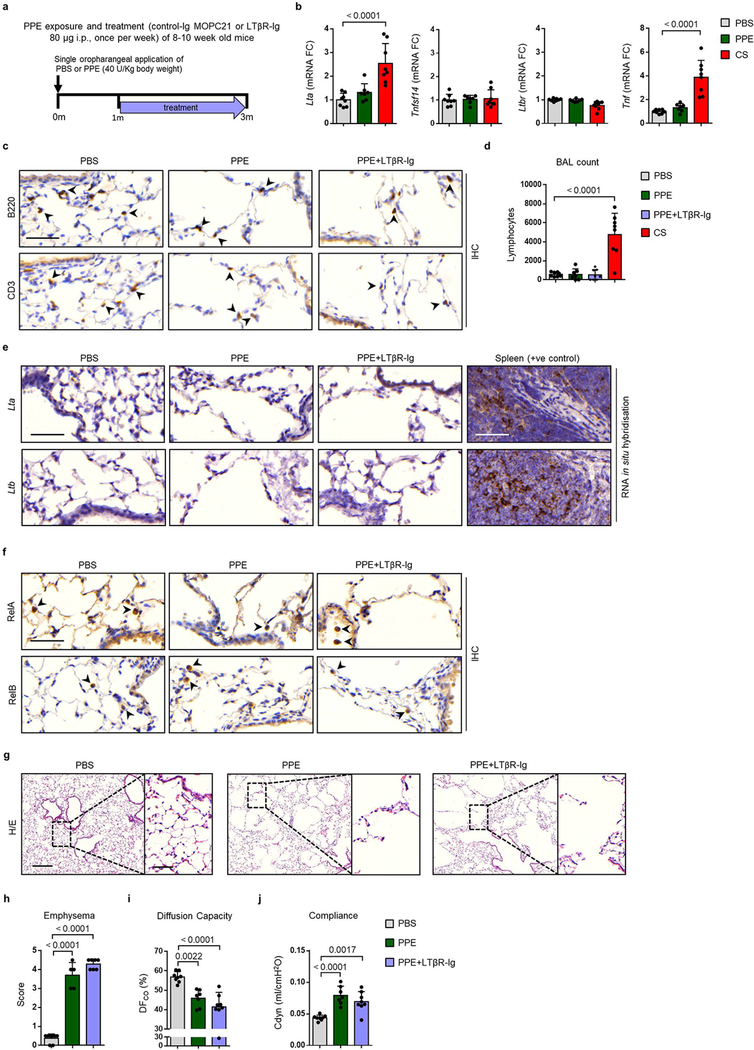

We next asked whether the therapeutic effect of LTβR-Ig on chronic smoking associated lung tissue is directly related to the blocking of LTβR-signalling. To address this, we examined the effect of LTβR-Ig treatment in the porcine pancreatic elastase (PPE)-induced emphysema model (Extended Data Fig. 7a), a LTβR-signalling and iBALT-independent mouse model (Extended Data Fig. 7b–c). We observed no detectable increase of mRNA expression of Lta, Ltb or Tnfsf14 (Extended Data Fig. 7b and e) or PPE-induced nuclear localisation of RelA and RelB in lung epithelial cells (Extended Data Fig. 7f). In contrast to the CS model, the PPE model displayed lower amounts of lymphocytes in BAL (Extended Data Fig. 7d). Histological analyses (Extended Data Fig. 7g–h) and lung function (Extended Data Fig. 7i–j) demonstrated that LTβR-Ig treatment could not reverse elastase-induced emphysema. This confirmed that LTβR-signal blockade is specifically relevant to iBALT mediated, LTβR-signalling induced emphysema.

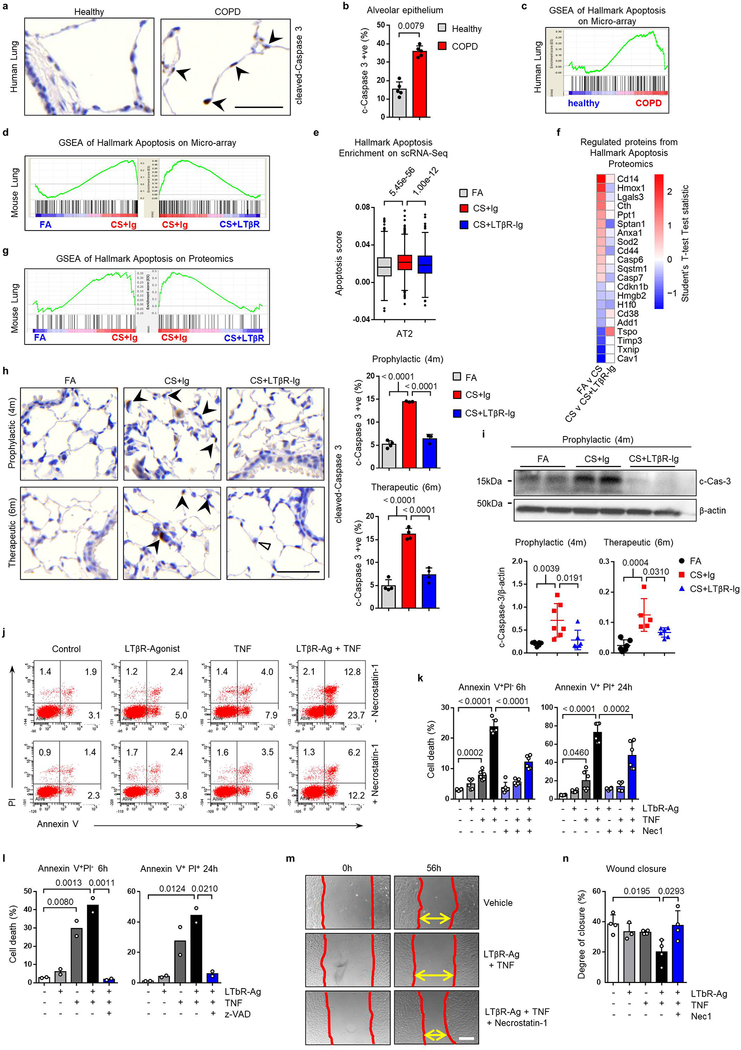

Next, we aimed at identifying how blocking LTβR-signalling promotes endogenous lung regeneration in emphysema. NIK is necessary for the activation of caspase-8 and subsequent downstream activation of caspase-3, by promoting the assembly of the RIP1/FADD/caspase-8 death complex following TNFR1 and LT stimulation28. Indeed, lung tissue sections from COPD patients demonstrated increased cleaved caspase-3-positive alveolar epithelial cells (Extended Data Fig. 8a–b). Furthermore, GSEA of lung tissue from COPD patients and CS-exposed mice showed enrichment of the apoptotic signature, which was reversed by LTβR-Ig treatment in mice (Extended Data Fig. 8c–d), and in AT2 epithelial cells as identified by single cell RNA-Seq (Extended Data Fig. 8e). This was confirmed by GSEA of whole lung proteome (Extended Data Fig. 8f–g), and by cleaved caspase-3 in both lung sections and lung lysates (Extended Data Fig. 8h–i). To examine LTβR-signalling in lung epithelial apoptosis, we stimulated mouse lung epithelial cells with LTβR-agonist and/or TNF (Extended Data Fig. 8j–k). Maximum cell death was achieved by combination of both, which was significantly reduced by inhibition of RIP1 kinase with necrostatin1 (Nec1) (Extended Data Fig. 8j–k). We validated that cell death was caspase-dependent, as it was completely abrogated in the presence of Z-Val-Ala-DL-Asp-fluoromethylketone (z-VAD-FMK), a pan-caspase inhibitor (Extended Data Fig. 8l). Interestingly, blocking apoptosis enabled partial wound regeneration in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 8m–n).

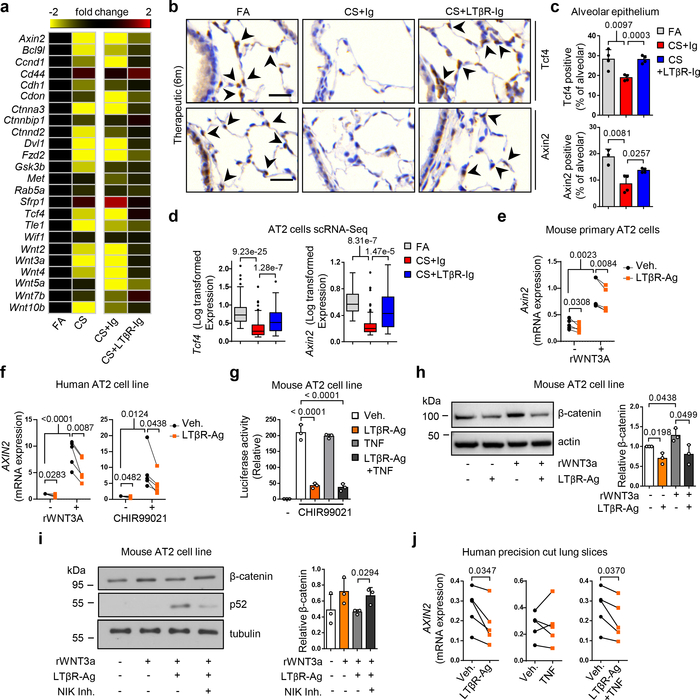

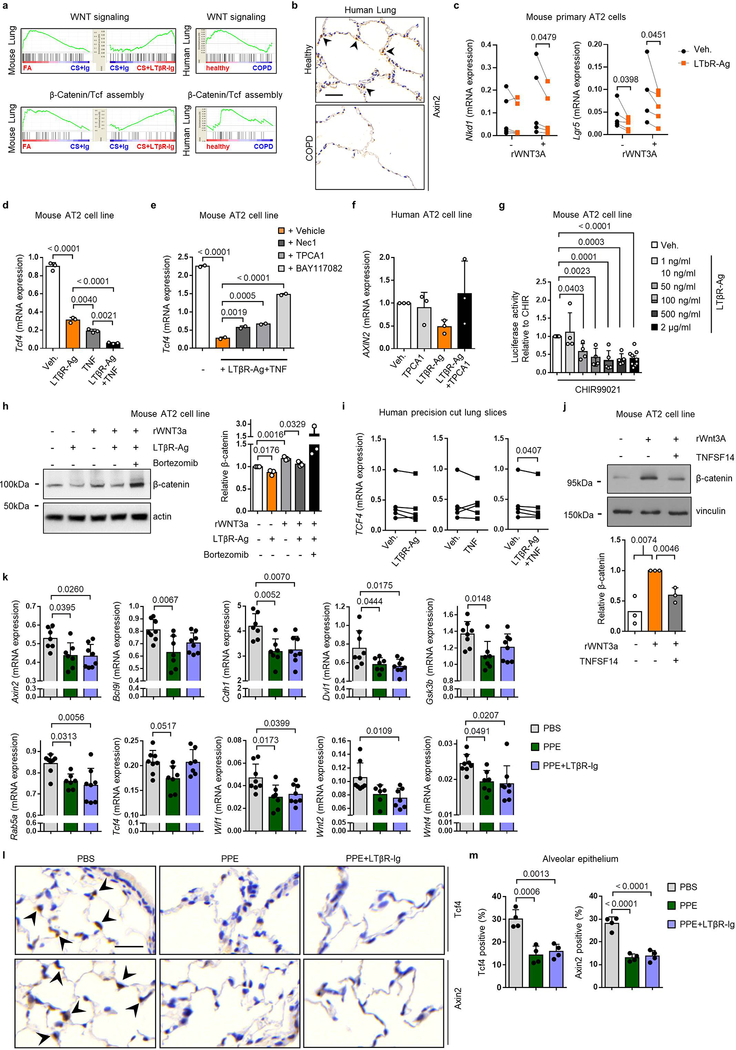

However, the mechanisms how blocking LTβR-signalling promotes lung regeneration (Fig. 2b and 2g), remained elusive. The developmental Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway is essential for lung development and homeostasis of progenitor AT2 stem cell function29,30. Our previous studies have demonstrated reduced Wnt/β-catenin signalling in COPD and have indicated that activation of Wnt/β-catenin signalling can induce lung repair21,31. In line, GSEA analysis of lung tissue transcriptomics (GSE47460) confirmed dampened Wnt/β-catenin signalling and reduced β-catenin/TCF transcription factor complex assembly in lung tissue from COPD patients, resulting in reduced Axin2 expression (Extended Data Fig. 9a–b). A similar pattern was found in lungs of CS+Ig-exposed mice (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 9a). Importantly, these transcriptional changes were significantly reversed by LTβR-Ig treatment (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 9a): combining immunostainings for the Wnt/β-catenin target-genes Tcf4 and Axin2 (Fig. 3b–c), and single cell RNA-seq analysis (Fig. 3d), we found that expression of these genes is specifically reduced in AT2 cells upon CS-exposure and is therapeutically restored upon LTβR-Ig treatment (Fig. 3b–d).

Fig. 3. Blocking LTβR-signalling induces Wnt/β-catenin in alveolar epithelial cells.

a, Heat map of mRNA abundance of Wnt signalling pathway genes determined by RT-qPCR from lungs of mice indicated at 6m. b, Representative images of immunohistochemical analysis for Tcf4 and Axin2 in lung sections from B6 mice treated as indicated (n=4 mice/group, brown signal, arrows, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 25μm). c, Quantification of alveolar epithelial cells positive for Tcf4 and Axin2 from (b). d, Normalised, Log transformed expression levels of Tcf4 and Axin2 in AT2 cells following scRNA-seq analysis. e, mRNA expression levels of Axin2 relative to Hprt, in primary murine AT2 cells with LTβR agonistic antibody (LTβR-Ag, 2 μg/ml) for 24h +/− rWNT3A (100ng/ml) (n=5 independent experiments). f, mRNA expression levels of AXIN2 relative to HPRT (normalized to Vehicle, Veh.) in A549 (human AT2) cell line with hLTβR-Ag (0.5 μg/ml) for 24h +/− rWNT3A (100ng/ml) and GSK-3β inhibitor (CHIR99021, 1μM) (n=5 independent experiments). g, Wnt/β-catenin luciferase reporter activity in MLE12 (murine AT2) cell line, activated with CHIR99021 (1μM) +/− LTβR-Ag (2 μg/ml) or rTNF (1 ng/ml) for 24h (n=3, representative of 5 independent experiments). h, Western blot analysis for β-catenin in MLE12 cells with LTβR-Ag (2 μg/ml) for 24h +/− rWNT3A (100ng/ml). Quantification relative to actin (n=3 independent experiments). For gel source data see Supplementary Fig 1. i, Western blot analysis for β-catenin and p52 in MLE12 cells with rWNT3A (200ng/ml) and LTβR-Ag (2 μg/ml) for 30h following 2h pre-treatment with NIK kinase specific inhibitor (Cmp1, 1μM). Quantification relative to tubulin (n=3 independent experiments). For gel source data see Supplementary Fig 1. j, mRNA expression level of AXIN2 relative to HPRT, in ex vivo human precision-cut lung slices stimulated for 24h with rTNF (20ng/ml) or hLTβR-Ag (2 μg/ml) (n=6 slices from individual lungs). Data shown mean ± SD (c, g-i), box and whiskers plots (box 25th-75th percentile, median line indicated and whiskers representing +/− 1.5 IQR) (d), individual lungs (e,j), or individual experiments (f). P values indicated, one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons Bonferroni test (g), Wilcoxon rank-sum test (two-sided) corrected with Benjamini-Hochberg (d), paired Student’s two-tailed t test (e,f,j), or Student’s two-tailed t test (c, h-i).

To establish a direct link between LTβR and Wnt/β-catenin signalling, primary AT2 cells and stable human and mouse cell lines were treated with LTβR-agonists, which led to a downregulation of the key Wnt/β-catenin target genes Axin2, Nkd1, Lgr5 and Tcf4 (Fig. 3e–f, Extended Data Fig. 9c–d). This was reversed by inhibiting NF-κB signalling (Extended Data Fig. 9e–f). Notably, ligand-independent β-catenin transcriptional reporter activity induced by GSK-3β inhibition was abrogated by LTβR-agonisation (Fig. 3g and Extended data Fig. 9g), thus suggesting intracellular signal modification downstream of the β-catenin destruction complex: Indeed, enhanced β-catenin degradation was observed upon LTβR-agonisation (Fig. 3h), which was reversed upon proteasome inhibition with bortezomib (Extended Data Fig. 9h). Targeting AT2 cells with the NIK kinase specific inhibitor Cmp132, reversed LTβR-agonist induced degradation of β-catenin (Fig. 3i), further confirming that LTβR-activation decreased Wnt/β-catenin signalling via NIK-dependent non-canonical NF-κB signalling. Furthermore, in a LTβR-signalling independent PPE-induced emphysema mouse model which also exhibits reduced Wnt/β-catenin signalling31 (Extended Data Fig. 7e–f), LTβR-Ig treatment neither reversed emphysema (Extended Data Fig. 7g–h), nor restored Wnt/β-catenin signalling (Extended Data Fig. 9k–m).

Importantly, both AXIN2 and TCF4 expression were also suppressed in ex vivo human PCLS stimulated with LTβR-agonist (Fig. 3j and Extended Data Fig. 9i). Of note, non-canonical NF-κB signalling induced by the alternative LTβR-ligand LIGHT (TNFSF14), also reduced β-catenin levels (Extended Data Fig. 9j).

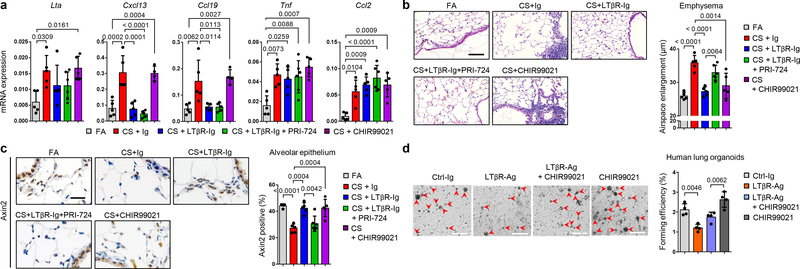

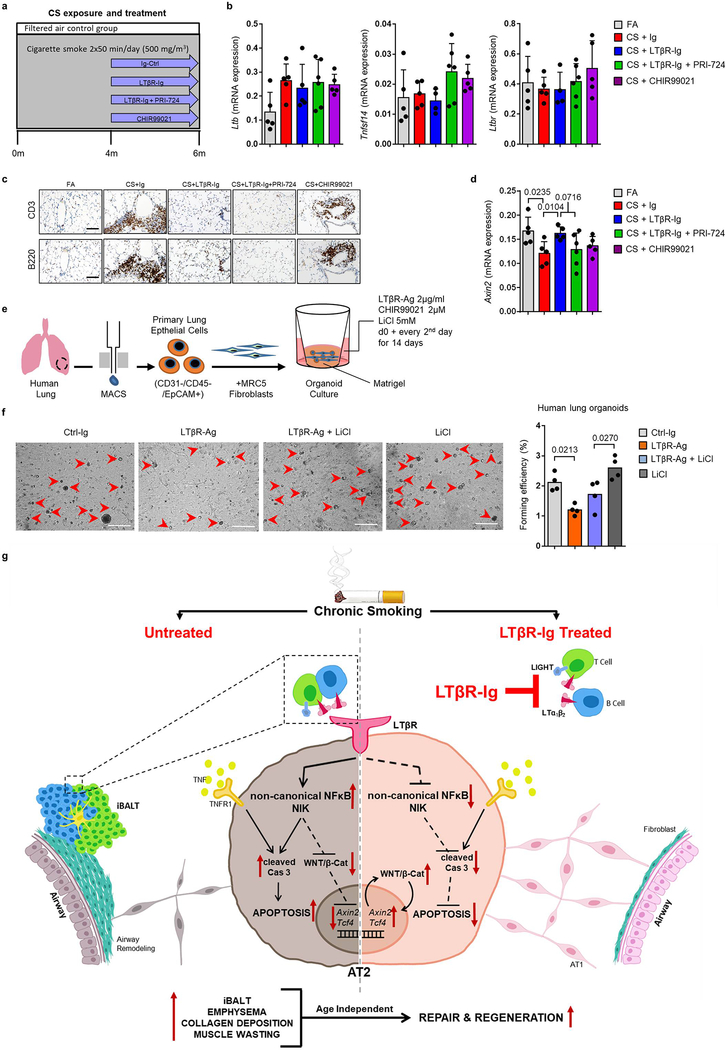

Finally, to test the hypothesis that LTβR-Ig treatment induces lung tissue regeneration following chronic CS exposure via endogenous Wnt/β-catenin signalling in vivo, mice were treated with (1) LTβR-Ig, (2) LTβR-Ig and the β-catenin/CBP inhibitor PRI-72433 and (3) CHIR99021, a WNT/β-catenin activator34 (Extended Data Fig. 10a). Similar to previous results (Fig 1b, d and Extended Data Fig 1k), LTβR-Ig treatment reduced the expression of Lta, Cxcl13 and Ccl19 (Fig. 4a) and reversed iBALT formation (Extended Data Fig. 10c). Ltb, Tnfsf14 and Ltbr levels (Extended Data Fig. 10b) as well as canonical NF-κB-signalling regulated Tnf and Ccl2 (Fig. 4a) again remained unchanged.

Fig. 4. Blocking WNT/β-catenin signalling reverses LTβR-Ig induced regeneration.

a-c, B6 mice were exposed to FA (n=5) or CS for 6m plus control Ig (n=5), LTβR-Ig (80 μg i.p., weekly, n=5), LTβR-Ig + beta-catenin/CBP inhibitor PRI-724 (0.6mg i.p., 2x weekly, n=6) or CHIR99021 (0.75mg i.p., weekly, n=5) from 4m – 6m, and analysed at 6m, see Extended Data Fig. 10a. a, Lung mRNA expression levels of genes indicated relative to Hprt determined by qPCR. b, Representative images of H/E stained lung sections (scale bar 100μm) and quantification of airspace enlargement as mean chord length. c, Representative images of immunohistochemical analysis for Axin2 in lung sections (brown signal, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 50μm) and quantification of alveolar epithelial cells positive for Axin2. d, Representative images and quantification of lung organoids from primary human AT2 cells cultured for 14d +/− human LTβR-Ag (2 μg/ml) and CHIR99021 (2μM), see Extended Data Fig. 10e (scale bar 500μm, n=2 replicates from 2 separate donors). Data shown mean ± SD, P values indicated, one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons Bonferroni test (a-d).

LTβR-Ig induced lung regeneration was similar to that triggered by treatment with CHIR99021 alone (Fig. 4b). In contrast, lung regeneration was significantly reduced by PRI-724 (Fig. 4b). This was accompanied by a significant reduction of Axin2-positive alveolar epithelial cells in CS-+Ig and CS+LTβR-Ig+PRI-724 (Fig. 4c). Notably, CS+LTβR-Ig or CS+CHIR99021 restored the number of Axin2-positive epithelial cells (Fig 4c). These data were also corroborated by analysis of Axin2 mRNA expression (Extended Data Fig. 10d). To test AT2 progenitor cell function, primary human AT2 cells were subjected to a lung organoid assay35. Organoid growth by human primary AT2 cells was functionally impaired by the activation of LTβR-signalling (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 10e). However, this phenotype was partially restored by activating Wnt/β-catenin signalling with CHIR99021 and LiCl (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig 10f).

In summary, analysing lung tissue from COPD patients and distinct mouse models we identified increased Lta and Ltb expression by B and T cells, as well as Tnfsf14 (LIGHT) expressed in T cells and granulocytes. We demonstrated a novel concept that therapeutic inhibition of LTβR-signalling restores lung architecture from smoking induced-emphysema and airway fibrosis. Blocking of LTβR-signalling abolished iBALT formation, apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells and re-initiated endogenous Wnt/β-catenin-driven alveolar regeneration. Mechanistically, activation of LTβR-signalling in progenitor AT2 cells decreased Wnt/β-catenin activity via non-canonical NF-κB signalling - through the non-canonical NF-κB inducing kinase, NIK (Extended Data Fig. 10g).

Analysis of lungs solely derived from end-stage COPD patients limited to delineate the earliest time points of iBALT/LTβR-signalling initiation during the progression of COPD-immunopathogenesis in our current study. However, it has been recently demonstrated that iBALT formation starts to become prevalent from moderate state of early COPD onwards, correlating with emphysema severity10,12. We believe it is imperative to conduct future (pre-) clinical studies incorporating LTβR-blockers and Wnt/β-catenin activators as a potential dual therapeutic approach. Our reported findings in chronic smoking-induced lung tissue pathogenesis may have additional implications in the context of other diseases associated with tertiary lymphoid structures/ LTβR-signalling, airway fibrosis and tissue regeneration, beyond COPD.

Methods

Human lung tissue core sampling

Lung core samples from explanted lungs of COPD patients undergoing lung transplantation were provided by Dr. Stijn Verleden (University of Leuven, Belgium) following ethical approval of the University of Leuven Institutional Review Board (ML6385). Patient demographics are highlighted in Supplementary Table 1. Immediately following transplant, lungs were air-inflated at 10 cm H2O pressure and fixed using constant pressure in the fumes of liquid nitrogen. Afterwards lungs were sliced using a band saw and sampled using a core bore. All participants provided informed written consent. For controls, unused donor lungs were collected under existing Belgian law which allows the use of declined donor lungs for research after second opinion inspection, and processed as above. Lungs were declined for various reasons (kidney tumor, logistics, presence of microthrombi). Upon receipt, lung cores were portioned for fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde followed by paraffin embedding, and total RNA isolation (peqGOLD Total RNA Kit, Peqlab).

Human precision cut lung slices

Tumor-free tissue from six patients who underwent lung tumor resection was used for the preparation of precision cut lung slices (PCLS) as described in detail previously36. Tissue was provided by the Asklepios Biobank for Lung Diseases (Gauting, Germany (project number 333–10)). All participants provided informed written consent, and the use of human tissue approved by the ethics committee of the Ludwig-Maximillian University (Munich, Germany (project number 455–12)). PCLS were cultivated in DMEM/Ham’s F12 medium supplemented with 0.1% FBS (Gibco, Life Technologies), 100U/ml penicillin-streptomycin and 2.5μg/ml amphotericin B (Sigma) at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere, and stimulated for 24h with 10μg/ml LPS (E. coli O55:B5, Sigma-Aldrich), 1ug/ml human LTβR-Ig fusion protein (kindly supplied by Jeffrey Browing, Biogen Idec), 20ng/ml recombinant human TNF (Cat. No. 300–01A, PeproTech) or 2 μg/ml agonistic antibody to human LTβR (clone BS1, Biogen Idec). Total RNA was isolated using peqGOLD Total RNA Kit (Peqlab).

Human lung organoid culture

Fresh human lung tissue from de-identified healthy donors were obtained through National Jewish hospital Human Lung Tissue Consortium (HLTC) and used following ethical approval by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Colorado and National Jewish Hospital under IRB exempt HS-2598. The HLTC obtains fresh lungs from Donor Alliance, our local organ procurement agency and the International Institute for the Advancement of Medicine. Primary human ATII cells were isolated as described previously37. Human lung organoid culture was adapted from previously described mouse lung organoid culture system38,39. Briefly, MRC-5 human foetal lung fibroblasts (ATCC) were proliferation-inactivated with 10μg/ml mitomycin C (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, USA) for 2 hours. 10,000 primary human lung EpCAM positive cells were resuspended in 50 μl media and diluted 1:1 with 10,000 MRC-5 cells in 50μl growth factor-reduced Matrigel (Corning, New York, USA). Cell mixture was seeded into 24-well plate 0.4 μm transwell inserts (Corning, New York, USA). Cultures were treated from day 0 and every 2nd or 3rd days in DMEM/F12 containing 5% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin, 2mM L-alanyl-L-glutamine, Amphotericin B (Gibco), insulin-transferrin-selenium (Gibco), 0.025μg/ml recombinant human EGF (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, USA), 0.1μg/ml Cholera toxin (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, USA), 30μg/ml bovine pituitary extract (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, USA), and 0.01μM freshly added all-trans retinoic acid (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, USA). 10 μM Y-27632 (Tocris) was added for the first 48 hours of culture. Organoids were imaged at day 14 using a Cytation1 cell imaging reader running Gen5 v3.08 software (Biotek, Winooski, USA) and quantified through ImageJ software (v1.52a, Bethesda, USA).

Animals and maintenance

8 to 10 week and 12 month old pathogen-free female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Charles River (Sulzfeld, Germany) and housed in rooms maintained at a constant temperature of 20–24°C and 45–65% humidity with a 12 hour light cycle. Animals were allowed food and water ad libitum. Mice were randomly allocated into experimental groups with no statistical methods used to predetermine sample size. Sample sizes were chosen based upon similar studies from the literature by ourselves and others and sufficient to detect statistically significant differences between groups. Quantitative morphometry on lung sections from mice was undertaken by readers blinded to the study groups. All animal experiments were approved by the ethics committee for animal welfare of the local government for the administrative region of Upper Bavaria (Regierungspräsidium Oberbayern) and were conducted under strict governmental and international guidelines in accordance with EU Directive 2010/63/EU.

Cigarette smoke (CS) exposure and LTβR-Ig treatment

Cigarette smoke (CS) was generated from 3R4F Research Cigarettes (Tobacco Research Institute, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY), with the filters removed. Mice were whole body exposed to active 100% mainstream CS of 500 mg/m3 total particulate matter (TPM) for 50 min twice per day for 4 and 6 months (m) in a manner mimicking natural human smoking habits as previously described40. The TPM level was monitored via gravimetric analysis of quartz fiber filters prior and after sampling air from the exposure chamber and measuring the total air volume. CO concentrations in the exposure chamber were constantly monitored by using a GCO 100 CO Meter (Greisinger Electronic, Regenstauf, Germany) and reached values of 288± 74 ppm. All mice tolerated CS-mediated CO concentrations without any sign of toxicity, with CO-Hb levels of 12.2 ± 2.4%.

In two parallel experiments, mice were treated with an LTβR-Ig fusion protein41 (80 μg i.p., weekly) (muLTβR-muIgG, kindly supplied by Jeffrey Browing, Biogen Idec) or control-Ig (MOPC21, Biogen Idec) for 2m, starting from 2m and 4m of CS exposure. Control mice were kept in a filtered air (FA) environment, but exposed to the same stress as CS-exposed animals. 24 h after the last CS exposure, mice were sacrificed. Experiments were performed twice, with n=8 animals per group.

Elastase application and LTβR-Ig treatment

Emphysema was induced in mice by a single oropharyngeal application of porcine pancreatic elastase (PPE, 40 U/kg body weight in 80 μl volume) as previously described42. Control mice received 80 μl of sterile PBS. Starting from day 28 after elastase application, mice were treated with an LTβR-Ig fusion protein (80 μg i.p., weekly) or control-Ig for 2 m. Experiments were performed twice, with n=8 animals per group.

4-paw muscle strength test

A grip strength meter system (Bioseb) was used to assess muscle strength in the mice. Mice holding onto a grid with 4 paws are slowly pulled away, the maximum force is recorded when the mouse releases the grid43. Each mouse was assessed three times over 1 minute, with the mean value being taken to represent the strength of an individual mouse. Body weight was also measured and taken into account for analysis.

Lung function measurements

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine, tracheostomized and the diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DFCO) calculated44. In brief, 0.8ml mixed gas (0.5% Ne, 21% O2, 0.5% CO and 78% N2) was instilled into the mice lungs and withdrawn 2s later for analysis on a 3000 Micro GC Gas Analyzer (Infinicon) running EZ IQ software v3.3.2 (Infinicon). DFCO was calculated as 1-(CO1/CO0)/(Ne1/Ne0) where 0 and 1 refers to the gas concentration before and after instillation respectively. Respiratory function was measured using a flexiVent system running Flexiware v7.6.4 software (Scireq). Mice were ventilated with a tidal volume of 10 ml/kg at a frequency of 150 breaths/min in order to reach a mean lung volume similar to that of spontaneous breathing. Testing of lung mechanical properties including dynamic lung compliance was carried out by a software-generated script that took four readings per animal.

Lung tissue processing

The right lung lobes were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, homogenized and total RNA isolated (peqGOLD Total RNA Kit, Peqlab). The left lobe was fixed at a constant pressure (20 cm fluid column) by intratracheal instillation of PBS buffered 6% paraformaldehyde and embedded into paraffin for histological analysis of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Masson’s Trichrome stained sections and for immunohistochemistry.

Generation of single cell suspensions from whole mouse lung tissue

Lung single cell suspensions were generated as previously described45,46. Briefly, after euthanasia, lung tissue was perfused with sterile saline through the heart and the right lung was tied off at the main bronchus. The left lung lobe was subsequently filled with 4% paraformaldehyde for later histologic analysis. Right lung lobes were removed, minced (tissue pieces at approx. 1 mm2), and transferred for mild enzymatic digestion for 20–30 min at 37°C in an enzymatic mix containing dispase (50 caseinolytic U/ml), collagenase (2 mg/ml), elastase (1 mg/ml), and DNase (30 μg/ml). Single cells were harvested by straining the digested tissue suspension through a 40 micron mesh. After centrifugation at 300 x g for 5 minutes, single cells were taken up in 1 ml of PBS (supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum), counted and critically assessed for single cell separation and overall cell viability. For Dropseq, cells were aliquoted in PBS supplemented with 0.04% of bovine serum albumin at a final concentration of 100 cells/μl.

Single cell RNA-sequencing using Dropseq

Dropseq experiments were performed according to previously published protocols45,47. Using a microfluidic device, single cells (100/μl) were co-encapsulated in droplets with barcoded beads (120/μl, purchased from ChemGenes Corporation, Wilmington, MA) at rates of 4000 μl/hr. Droplet emulsions were collected for 10–20 min/each prior to droplet breakage by perfluorooctanol (Sigma-Aldrich). After breakage, beads were harvested and the hybridized mRNA transcripts reverse transcribed (Maxima RT, Thermo Fisher). Unused primers were removed by the addition of exonuclease I (New England Biolabs). To improve the quality of the single cell transcripts and later the sequencing recovery, beads were subjected to Klenow enzyme treatment, as described for the Seq-Well single cell protocol48. Briefly, beads were incubated in freshly prepared 0.1M NaOH for 5 min while rotating and washed using TE-buffer (10mM Tris at pH 8.0, 1mM EDTA), supplemented with 0.01% Tween-20 (TE-TW buffer). Subsequently, beads were washed in TE-TW buffer and 1x TE buffer. Beads were resuspended in 200 uL/sample Klenow mix (cf. Seq-well protocol for details48) and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C at end-over-end rotation. After Klenow enzymatic treatment, beads were washed, counted, and aliquoted for pre-amplification (2000 beads/reaction, equals ca. 100 cells/reaction) with 12 PCR cycles (Smart PCR primer: AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT (100 μM), 2x KAPA HiFi Hotstart Ready-mix (KAPA Biosystems), cycle conditions: 3 min 95°C, 4 cycles of 20s 98°C, 45s 65°C, 3 min 72°C, followed by 9 cycles of 20s 98°C, 20s 67°C, 3 min 72°C, then 5 min at 72°C). PCR products of each sample were pooled and purified twice by 0.6x clean-up beads (CleanNA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Prior to tagmentation, complementary DNA (cDNA) samples were loaded on a DNA High Sensitivity Chip on the 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent) to ensure transcript integrity, purity, and amount. For each sample, 1 ng of pre-amplified cDNA from an estimated 1500 cells was tagmented by Nextera XT (Illumina) with a custom P5-primer (Integrated DNA Technologies). Single-cell libraries were sequenced in a 100 bp paired-end run on the Illumina HiSeq4000 using 0.2 nM denatured sample and 5% PhiX spike-in. For priming of read 1, 0.5 μM Read1CustSeqB (primer sequence: GCCTGTCCGCGGAAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTAC) was used.

Single cell RNA-seq data analysis

Following the sequencing the processing of next generation sequencing reads of the scRNA-seq data was performed as previously described47. Briefly, the Drop-seq computational pipeline was used (version 2.3.0) as previously described and STAR (version 2.5.3a) was used for the alignment of reads to the mm10 reference genome (provided by the Drop-seq group, GSE63269). For barcode filtering, we excluded barcodes with less than 200 detected genes.

Downstream analysis was performed using the Scanpy package49. During preprocessing steps we assessed the quality of our libraries and applied suitable filter criteria motivated by previously described pest practices50 with slight adjustments. After exploration of UMI counts and genes per cell for the combined count matrices, we retained barcodes with count numbers in the range of 400 to 6000 counts per cell and genes detected in at least 3 cells. A high proportion of transcript counts derived from mitochondria-encoded genes may indicate low cell quality, and we removed cells with a percentage of mitochondrial transcripts of larger than 20%.

The expression matrices were normalized with scran’s size factor based approach51 and log transformed via scanpy’s pp.log1p() function. In an additional step to mitigate the effects of unwanted sources of cell-to-cell variation, we calculated and regressed out the cell cycle score for each cell. Variable genes were selected sample-wise, excluding known cell cycle genes. Those genes being ranked among the top 4000 in at least 3 samples were used as input for principal component analysis. Clustering was performed via scanpy’s louvain method at resolution 2 and cell types manually annotated by using known marker genes. We encountered one unidentifiable cluster marked by low number of counts and high proportion of mitochondrial transcript enriched cells, thus we marked these cells as unqualified and additionally filtered it out. The visualization was obtained with the UMAP embedding specifying the input parameters as 50 PCs and 20 nearest neighbours. The final object encompassed 25095 genes across 21413 cells.

Scoring for enrichment of gene signatures of interest was performed by using scanpy’s tl.score_genes() function and the following gene lists: 1) Apoptosis score: 157 genes from our data set overlapping with Hallmark Apoptosis list from MSigDB. 2) positive regulation of NIK/NF-kappaB signaling: 76 Genes associated with the corresponding GO Term GO:1901224. Statistical significance was assessed by using Wilcoxon rank-sum test on normalized, log transformed count values and corrected with Benjamini-Hochberg. Single cell RNA-Seq metadata can be found in Supplementary Table 4. All code used for data visualization of the single cell RNA-Seq data can be found at https://github.com/theislab/2020_Inhibition_LTbetaR-signalling.

Proteome analysis of whole lung homogenates

Proteins have been loaded on SDS-gel, which ran only a short distance of 0.5 cm. After Commassie staining the total sample was cut out unfractionated and used for subsequent Trypsin digestion according to a slightly modified protocol described by Shevchenko et al.52 carried out on the DigestPro MSi robotic system (INTAVIS Bioanalytical Instruments AG).

Digested samples have been loaded on a cartridge trap column, packed with Acclaim PepMap300 C18, 5μm, 300Å wide pore (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and separated in a 180 min gradient from 3% to 40% ACN on a nanoEase MZ Peptide analytical column (300Å, 1.7 μm, 75 μm x 200 mm, Waters) and a UltiMate 3000 UHPLC system. Furthermore, eluting peptides have been analyzed by an online coupled Q-Exactive-HF-X mass spectrometer running software version Exactive Series 2.9 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a data depend acquisition mode where one full scan was followed by up to 12 MSMS scans of eluting peptides.

Proteomic data analysis

Mass spectrometry raw files were processed using the MaxQuant software53 (version 1.6.12.0). As previously described54, peak lists were searched against the mouse Uniprot FASTA database (version November 2016), and a common contaminants database by the Andromeda search engine.

All statistical and bioinformatics operations such as normalization, principal component analysis, annotation enrichment analysis and hierarchical clustering of z-scored MS-intensities were run with the Perseus software package (version 1.6.10.50)55. Proteomics data can be found in Supplementary Table 5.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) from the lungs of C57BL/6 mice exposed to FA for 6m (n=3), CS for 6m (n=3) and CS for 6m plus the LTβR-Ig fusion protein for the last 2m (therapeutic protocol, n=3) as described above. RNA quality was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, with high-quality RNA (RIN>7) being used for analysis. 300 ng of total RNA was amplified using the Illumina TotalPrep RNA Amplification kit (Ambion), then hybridized to Mouse Ref-8 v2.0 Expression BeadChips (Illumina). Staining and scanning were undertaken according to the Illumina expression protocol. Data was processed using the GenomeStudioV2010.1 software (gene expression module version 1.6.0) in combination with the MouseRef-8_V2_0_R3_11278551_A.bgx annotation file. The background subtraction option was used and an offset to remove remaining negative expression values introduced. CARMAweb was used for quantile normalization56. Statistical analyses were performed by utilizing the statistical programming environment R (v3.2.3, R Development Core Team), implemented in CARMAweb. Genewise testing for differential expression was carried out employing the limma t-test and Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction (FDR < 10%). Heat maps were generated using Genesis software (Release 1.7.7, Institute for Genomics and Bioinformatics, Graz University of Technology).

Flow cytometry analysis of lung

Single cell suspension was derived by using MACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to manufacturer`s instructions. Staining was performed using Live/Dead discrimination by ZombieDyeNIR according to the manufactureŕs instructions for lymphocytes and Live/Dead discrimination by fixable viability stain FVS620 (BD) for myeloid cells. After washing (~400g, 5min, 4°C), cells were stained in 25μl of titrated antibody master mix for 20min protected from light at 4°C and washed again57. Cells were analyzed using BD FACSFortessa running FACSDiva software v8.0.1. Data were analyzed using Flowlogic v7.3 and FlowJo v10.6.1. For tSNE representation myeloid cells were downsampled to 3000 live CD45+CD11b+ and/or CD11c+ cells; and lymphocytes were downsampled to 5000 live CD45+ cells. Antibodies used are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Quantitative real time RT-PCR

cDNA was synthesized from 1μg total RNA using Random Hexamers and MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (Applied Biosystems). mRNA expression was analyzed using Platinum SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix (Applied Biosystems) on a StepOnePlus™ 96 well Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Primers were designed using Primer-BLAST software (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/) or obtained from PrimerBank58 (https://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Relative expression of each gene was calculated relative to the housekeeping gene HPRT1 or Hprt1 as 2-ΔCt, and fold changes compared to control samples as 2-ΔΔCt values. Relative changes of selected genes were also presented as a heat map generated by Genesis software (Release 1.7.7, Institute for Genomics and Bioinformatics, Graz University of Technology).

Immunohistochemistry

3μm sections from human core samples or mouse left lung were deparaffinizing in xylene and rehydrated before treatment with 1.8% (v/v) H2O2 solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to block endogenous peroxidase. Heat induced epitope retrieval was performed in HIER citrate buffer (pH 6.0, Zytomed Systems) in a decloaking chamber (Biocare Medical). To inhibit nonspecific binding of antibodies, sections were treated with a blocking antibody (Biocare Medical). After overnight incubation with primary antibodies at 4°C sections were incubated with an alkaline phosphatase or HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Biocare Medical). Signals were amplified by adding chromogen substrate Vulcan fast red or 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Biocare Medical), respectively. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich) and dehydrated in xylene and mounted. Primary antibodies: rabbit anti-RelA/p65 (1:500, clone A, Cat. No. sc-109, Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-RelB (1:400, clone C-19, Cat. No. sc-226, Santa Cruz), mouse anti-CD20 (1:100, clone L26, Cat. No. MSK008, Zytomed Systems), rat anti-B220 (1:3000, clone RA3–6B2, Cat. No. 553084, BD Biosciences), rabbit anti-CD3 (1:500, clone SP7, Cat. No. RBK024, Zytomed Systems), rabbit anti-CD68 (1:100, polyclonal, Cat. No. ab125212, Abcam), rabbit anti-Collagen I (1:250, polyclonal, Cat. No. ab21286, Abcam), rabbit anti-pSMAD2 (1:500, polyclonal, Cat. No. AB3849, Merck Millipore), mouse anti-hLTB (1:1000, clone B27, kindly supplied by Jeffrey Browing, Biogen Idec), rabbit anti-cleaved caspase3 (1:300, polyclonal, Cat. No. 9661, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-TCF4 (1:100, polyclonal, Cat. No. ab185736, Abcam) and Rabbit anti-Axin2 (1:2000, polyclonal, Cat. No. ab32197, Abcam).

Multiplex immunofluorescence staining

Sequential immunostaining was performed on 3μm thick Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) murine lung sections. Briefly, heat mediated antigen retrieval was performed in citrate pH 6.0 (antibody Mix 1, ThermoFisher), or in EDTA pH 9.0 (antibody Mix 2, Novus) buffer. Antibody elution was performed between each staining cycle59. Antibodies used in Mix 1 were; Rat anti-CD4 (1:200, ThermoFisher #14–9766-82), Rat anti-CD8a (1:200, ThermoFisher #14–0808-82) and Rat anti-B220 (1:500, Biolegend #103202). Antibodies used in Mix 2 were; Rabbit anti-IBA1 (1:1000, VWR #100369–764), Rabbit anti-iNOS (1:100, Abcam #ab15323) and Rabbit anti-CD206 (1:500, ProteinTech #18704–1-AP). Secondary antibodies used were: anti-Rabbit 555 (1:500, Cell Signaling #4413S), anti-Rabbit 647 (1:500, Cell Signaling #4414S) and anti-Rat 647 (1:500, Cell Signaling #4418S).

Acquired images were processed using FIJI and the FIJI plugin HyperStackReg V5.660 (and Ved Sharma. 2018, December 13). ImageJ plugin HyperStackReg V5.6 (Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2252521). Autofluorescence acquired in non-relevant channels was substracted as appropriate. IBA1 and iNOS staining quantitation was performed using Ilastik (v1.3.3post2)61 and CellProfiler (v3.1.9)62.

RNA in situ hybridization

5μm sections from paraffin embedded mouse left lung or human core samples were used for in situ hybridization using the RNAscope® 2.5 HD Assay- BROWN (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions and the RNAscope® EZ-Batch™ Slide Processing System (Advanced Cell Diagnostics). The following probes from Advanced Cell Diagnostics were used; RNAscope® Probe-Mm-Lta (Cat. No. 317231), RNAscope® Probe-Mm-Ltb (Cat. No. 315681), RNAscope® Probe-Mm-Tnfsf14 (Cat. No. 411111), RNAscope® Probe-Mm-TNFa (Cat. No. 311081), RNAscope® Probe-Hs-LTA (Cat. No. 310461) and RNAscope® Negative Control Probe – DapB (Cat. No. 310043).

Quantitative morphometry

Design-based stereology was used to analyze sections using an Olympus BX51 light microscope equipped with a computer-assisted stereological toolbox (newCAST, Visiopharm) running Visopharm Integrator System (VIS) v6.0.0.1765 software, on H&E or Masson’s Trichrome stained lung tissue sections as previously described63,64. Air space enlargement was assessed by quantifying mean linear chord length (MLI) and alveolar surface density on 30 fields of view per lung using the x20 objective. Briefly, a line grid was superimposed on lung section images. Intercepts of lines with alveolar septa and points hitting air space were counted to calculate MLI applying the formula MLI = ∑Pair x L(p) / ∑Isepta x 0.5. Pair are the points of the grid hitting air spaces, L(p) is the line length per point, Isepta is the sum of intercepts of alveolar septa with grid lines. Alveolar surface density (SD) was calculated applying the formula SD = 2x ∑Isepta / ∑Psepta x L(p) where Psepta are the points of the grid hitting alveolar septa.

Volume of inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) and airway collagen normalized to the basal membrane was quantified on 50 fields of view per lung (using the x40 objective) by counting points hitting iBALT (PiBALT) or airway collagen (Pcollagen) and intercepts of lines with airways and vessels (Iairway+vessel). The volume was calculated by applying the formula V/S = ∑PiBALT/collagen x L(p) / ∑Iairway+vessel. Furthermore, the total number of iBALT was quantified in a whole lung tissue slide and normalized to total number of airways.

For quantification of immunohistochemistry stained lung tissue sections 20 random fields of view were assessed across each lung using the CAST system and x40 objective. The total number of CD68 positive cells was recorded. For RelA, RelB, caspase-3, Axin2 and Tcf4 counting the number of positive alveolar epithelial cells out of the total number of alveolar epithelial cells were recorded as a percentage.

Western blotting

20 μg of protein was separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad), blocked with 5% non-fat milk and immunoblotted overnight at 4°C with antibodies against RelB (1:1000, Clone D7D7W, Cat. No. 10544, Cell Signaling), p52 (and p100) (1:1000, polyclonal, Cat. No. 4882, Cell Signaling), cleaved caspase-3 (1:1000, polyclonal, Cat. No. 9661, Cell Signaling) and β-catenin (1:1000, clone 14, Cat. No. 610154, BD Biosciences). Antibody binding was detected with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and developed using Amersham ECL Prime reagent (GE Healthcare). Bands were detected and quantified using the Chemidoc XRS+ system running ImageLab v5.2.1 software (Bio-Rad) or using photographic film and ImageJ (v1.49o), and normalized to β-actin levels (anti-β-actin-peroxidase conjugated mouse monoclonal antibody, 1:50000, clone AC-15, Cat. No. A3854, Sigma-Aldrich), vinculin (anti-vinculin, 1:1000, clone 7F9, Cat. No. sc-73614, Santa Cruz) or tubulin (anti-tubulin, 1:5000, clone B-5–1-2, Cat. No. T6074, Sigma-Aldrich).

ELISA

Concentrations of active TGF-β in BALF were determined using a commercially available kit for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (eBioscience, ThermoFisher Scientific).

Primary mouse alveolar type 2 (pmAT2) cell isolation and culture

pmAT2 cells were isolated as previously described65–68. Briefly, mouse lungs were intratracheally inflated with dispase (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) followed by 300 μl instillation of 1% low gelling temperature agarose (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, USA). Lungs were minced and filtered through 100 μm, 20 μm and 10 μm nylon meshes (Sefar, Heiden, Switzerland). Negative selection of fibroblasts was performed by adherence on cell culture dishes for 30 minutes. Nonadherent cells were collected and white blood cells and endothelial cells were depleted with CD45 and CD31 magnetic beads respectively (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), according to manufacturer’s instructions. pmATII cells were resuspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS (Pan-Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany), 2 mM l-glutamine (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA), 100mg/l streptomycin, and 100 U/ml penicillin (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, USA), 3,6 mg/ml glucose (Applichem, Darmstadt, Germany) and 10 mM HEPES (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA) and cultured for 48 h to allow attachment. Cells were starved with 0.1% FBS containing medium and finally treated for 24h with an agonistic antibody to LTβR [2 μg/ml] (clone ACH6, kindly supplied by Jeffrey Browing, Biogen Idec) and recombinant mouse WNT3A [100 ng/ml] (Cat. No. 1324-WN, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

LA4 cell culture

The murine AT2-like cell line LA4 (CCL-196, ATCC) was maintained in Ham’s F12 medium containing NaHCO3 and stable glutamine (Biochrom AG), supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum (Gibco, Life Technologies), 100U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% non-essential amino acids (Biochrom AG) at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. The cell line was not authenticated. LA4 cell lines were routinely tested for Mycoplasma, and tested negative.

For LA4 apoptosis measurements, cells were seeded at 1×105 cells per well in 24-well plates. 24 h later, cells were stimulated for 6 and 24 h with an agonistic antibody to LTβR [2 μg/ml] (5G11, Cat. No. HM1079, Hycult Biotech), recombinant murine TNF-α [1 ng/ml] (Cat. No. 315–01A, PeproTech) or a combination thereof. To inhibit apoptotic signaling, cells were co-stimulated with Necrostatin-1 [50 μM] (Cat. No. N9037, Sigma-Aldrich) or Z-Val-Ala-DL-Asp-fluoromethylketone (z-VAD-FMK) [20 μM] (Cat. No. 627610, Merck Millipore). Apoptosis levels were analyzed using the Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit APC (eBioscience, ThermoFisher Scientific) and the stained cells were quantified on a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) with BD FACSDiva v6.1.3 software.

For the LA4 wound healing assay, a scratch was induced 24 h after seeding (time point 0h) and cells were stimulated for 24h as described above. Afterwards, cells were washed and cultured for a further 32h (time point 56h) in fresh medium. Wound closure was determined as the percentage of wound closure at 0 and 56h using AxioVision software (v4.9.1.0, Zeiss) to calculate the wound surface area.

To examine Wnt signalling cells were seeded at 1×105 cells per well in 24-well plates. 24 h later, cells were stimulated for 24 h with an agonistic antibody to LTβR [2 μg/ml] (clone ACH6, kindly supplied by Jeffrey Browing, Biogen Idec), recombinant murine TNF-α [1 ng/ml] (Cat. No. 315–01A, PeproTech) or a combination thereof. Additionally cells were pretreated for 1 h and then incubated for 24 h with necrostatin-1 [50 μM] (Cat. No. N9037, Sigma-Aldrich), TPCA-1 [10 μM] (Cat. No. T1452, Sigma-Aldrich) or BAY 11–7082 [10 μM] (Cat. No. B5556, Sigma-Aldrich). Total RNA was isolated using the peqGOLD Total RNA Kit (Peqlab).

A549 and MLE12 cell culture

Both the human AT2-like cell line A549 (CCL-185, ATCC) and murine AT2-like cell line MLE12 (CCL-2110, ATCC) were maintained in DMEM/F12 medium containing NaHCO3 and stable glutamine (Biochrom AG), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco, Life Technologies) and 100U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Both cell lines were not authenticated. Both cell lines were routinely tested for Mycoplasma, and tested negative.

For mRNA experiments cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 5×104 cells per well and for protein cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 2×105 cells per well. 24h later cells were stimulated in medium containing 0.1% fetal calf serum with, recombinant murine WNT3A (100 ng/ml, Cat. No. 1324-WN, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN or Cat. No. 315–20 Peprotech, Hamburg, Germany), CHIR99021 (1 μM, Cat. No. 4423, Tocris, Minneapolis, MN), an agonistic antibody to LTβR (for mouse 2 μg/ml clone ACH6, for human 0.5 μg/ml clone BS1 both kindly supplied by Jeffrey Browing, Biogen Idec), recombinant murine LIGHT (250–500 ng/ml, Cat. No. 664-LI-025/CF, R&D Systems), TPCA-1 (5 μM, Cat. No. T1452, Sigma-Aldrich) and Bortezomib (10 nM, (Millennium, Takeda, Cambridge, MA). Total RNA was isolated using the peqGOLD Total RNA Kit (Peqlab) and cellular lysates prepared in RIPA buffer.

In additional experiments, MLE12 cells were pre-treated 2h with the NIK kinase inhibitor (Cmp1, 1 μM, prepared in house) and stimulated for 30h with recombinant murine WNT3A (200 ng/ml, Cat. No. 1324-WN, R&D Systems), an agonistic antibody to LTβR (2 μg/ml, clone ACH6) or recombinant Flag-LIGHT (200 ng/ml, Cat: ALX-522–018-C010, Alexis Biochemicals). Cellular lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer for Western blot analysis.

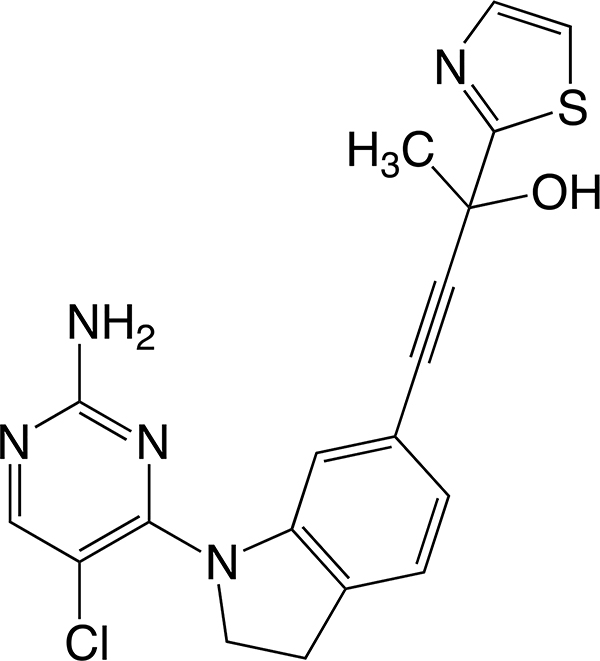

Synthesis of the NIK kinase inhibitor

The NIK kinase inhibitor (4-(1-(2-amino-5-chloro-4-pyrimidinyl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-indol-6-yl)-2-(1,3-thiazol-2-yl)-3-butyn-2-ol) Cmp1, was obtained according to the synthetic process described in WO 2009/158011 A1.

However, to improve the yields, the last step consisting of the Sonogashira coupling reaction between the aryl bromide and the alcyne using cuprous iodide and triethylamine as the catalysts in DMF was replaced by the use of palladium acetate and triphenylphosphine in the presence of DBU as the catalytic system in THF according to a recent publication69.

Wnt/β-catenin luciferase reporter assay

Wnt/β-catenin signaling was measured as previously described 37. In short, M50 Super 8x TOPflash and M51 Super 8x FOPflash plasmids 70, containing a firefly luciferase gene under the control of TCF/LEF binding sites (TOPflash) or mutated TCF/LEF binding sites (FOPflash) were used. MLE 12 cells were plated in 48-well plates at a density of 55.000 cells per well. The following day cells were transfected with either 75 ng/well of M50 Super 8x TOPflash plasmid or the negative control M51 Super 8x FOPflash using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA) in serum-free Opti-MEM medium (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA). After 6 hours of transfection, cells were stimulated for 24h with an agonistic antibody to LTβR [2 μg/ml] (clone ACH6, kindly supplied by Jeffrey Browing, Biogen Idec), recombinant murine TNF-α [1 ng/ml] (Cat. No. 315–01A, PeproTech) and CHIR99021 [1μM] (Cat. No. 4423, Tocris, Minneapolis, MN). Cells were lysed using Glo lysis buffer and luciferase activity was assayed using the Bright-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). Luciferase activity was determined using a luminescence plate reader (Berthold Technologies). Measured values were analyzed with WinGlow Software (MikroWin v4.41, Berthold Technologies) and TOPflash activity was normalized to FOPflash activity and expressed relative to control conditions.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

GSEA software (v4.0.1) from the Broad Institute (http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp)71,72 was used to determine the enrichment of gene lists in our microarray data generated above, proteomic data generated above and data obtained from series matrix files downloaded from the NCBI GEO database (GSE47460-GPL1455073, GSE37768, GSE56768 and GSE5250963). The following gene lists were examined; Hallmark collection v6.2 (Broad Institute), GO:0033209 tumor necrosis factor-mediated signaling pathway, GO:0051092 positive regulation of NF-kappaB transcription factor activity, GO:0043123 positive regulation of I-kappaB kinase NF-kappaB signaling, GO:0038061 NIK NF-kappaB signaling, GO:0008013 beta catenin binding, and GO:0060070 canonical WNT signaling. Gene lists for apoptosis were obtained from the Hallmark collection, and for LTβR signaling and NF-κB signaling from the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) Software (Qiagen).

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean values ± SD, with sample size and number of repeats indicated in the figure legends. One-way ANOVA with the multiple comparisons Bonferroni test was used to compare multiple groups. For comparisons between two groups unpaired or paired two-tailed Student’s t test was used. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 6 or 8 software (GraphPad Software).

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Canonical and non-canonical NFκB-signalling pathways are activated in the lungs of COPD patients and CS-exposed mice.

a-b, Representative images of immunohistochemical analysis for RelA (a) and RelB (b) (brown signal, indicated by arrows, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 50μm, zoomed area 25μm) in lung core biopsy sections from healthy (n=3) and COPD patients (n=4), with the quantification of RelA and RelB positive alveolar epithelial nuclei shown as mean ± SD. c-e, Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of the LTβR signalling, NF-κB signalling (gene lists from IPA software, Qiagen), TNFR-mediated signalling (GO:0033209), positive regulation of I-kappaB kinase NF-kappaB signalling (GO:0043123) and NIK NF-kappaB signalling (GO:0038061) pathways in publically available array data from lung tissue (GSE47460-GPL14550) of healthy (n=91) v COPD patients (n=145) (c), from lung tissue (GSE37768) of healthy (n=9) v COPD patients (n=18) (d) and from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (GSE56768) of healthy (n=5) v COPD patients (n=49) (e). f, mRNA expression levels of Lta, Ltbr, Tnfsf14 (Light), Tnf, Ccl2 and Cxcl13 determined by qPCR in whole lung from B6 mice exposed to filtered air (FA, n=6) or cigarette smoke (CS, n=8) for 6m, individual mice shown. g, GSEA of the pathways described in (c-e) in the publically available array data (GSE52509) of lungs from our mice exposed to filtere air (FA, n=3) and cigarette smoke (CS, n=6) for 4 and 6m. h, Western blot analysis for RelB, p100 and p52 in total lung homogenate from the mice described in (f). Quantification relative to vinculin of individual mice shown (n=3). For gel source data see Supplementary Fig 1. i, Schematic representation of the LTβR-Ig treatment protocol. j, Representative low and high magnification overlay images of Multiplex immunofluorescence staining to identify CD4 (Red), CD8 (Green), B220 (Turquoise) and DAPI (blue) counterstained lung sections (Scale bars 100μm, n=4) from B6 mice exposed to CS for 6m, plus LTβR-Ig fusion protein or control Ig (80 μg i.p., weekly) therapeutically from 4 to 6m, and analysed at 6m. k, mRNA expression levels of Cxcl13 and Ccl19 determined by qPCR in whole lung from B6 mice exposed to FA or CS for 4 and 6m, plus LTβR-Ig fusion or control Ig (80 μg i.p., weekly) prophylactically from 2 to 4m and analysed at 4m, and therapeutically from 4 to 6m and analysed at 6m (n=4 mice/group, repeated twice, pooled data shown). P values indicated, Mann-Whitney one-sided test (a-b), unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (f, h), one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons Bonferroni test (k).

Extended Data Fig. 2. Immune response in lungs of CS-exposed mice treated with LTβR-Ig.

a-c, Flow cytometry analysis of single cell suspensions for adaptive immune cells from whole lung of B6 mice exposed to FA (n=6) or CS for 6m, plus LTβR-Ig fusion (n=5) or control Ig (n=5) (80 μg i.p., weekly) from 4 to 6m and analysed at 6m. a, t-SNE plots showing the distribution and composition of CD4 and CD8 T cells as Tcm (CD62L+CD44+), Tem (CD62L−CD44+) and Tscm (CD62L+CD44−) (left) and t-SNE plots showing the distribution of the surface markers indicated (upper right) and global changes in composition with treatment (lower right). b, Abundance of the T cell populations indicated as a percentage of total CD45+ cells. c, Upper are t-SNE plots showing the distribution of CD19, IgG, MHCII, CD69 and GL7 positive cells, while lower is the abundance of CD19+ B cells as a percentage of total CD45+ cells and the geometric mean fluorescence intensity of the expressed markers indicated on CD19+ B cells. d-g, B6 mice were exposed to FA or CS for 4 and 6m, plus LTβR-Ig fusion protein or control Ig (80 μg i.p., weekly) prophylactically (Proph.) from 2 to 4m and analysed at 4 months and therapeutically (Ther.) from 4 to 6 months, and analysed at 6m. d, Representative images of immunohistochemical analysis for CD68 macrophages in lung sections from the mice (n=4 mice/group, brown signal indicated by arrow heads, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 100μm). e, Quantification of CD68 positive macrophages across 20 random fields of view from lung sections stained in (d) (n=4 mice/group). f, Representative low and high magnification overlay images of Multiplex immunofluorescence staining to identify IBA1 (Red), iNOS (Green), CD206 (Turquoise) and DAPI (blue) counterstained lung sections from mice at 6m (Scale bars 100μm and 25μm respectively, n=4 mice/group). g, iNOS and IBA1 double positive macrophages from Multiplex immunofluorescence staining on lung sections from mice treated both prophylactically and therapeutically was quantified using Ilastik and CellProfiler (n=4 mice/group). h-l, Flow cytometry analysis of single cell suspensions for myeloid cells from whole lung of B6 mice exposed to FA (n=6) or CS for 6m, plus LTβR-Ig fusion (n=5) or control Ig (n=5) (80 μg i.p., weekly) from 4 to 6m and analysed at 6m. h, t-SNE plots showing the distribution and composition of myeloid cells and surface markers indicated. i, t-SNE plots showing global changes in composition with treatment. j, Composition of CD45+Ly6g−F480+CD11c+ alveolar macrophages. k, Composition of CD45+Ly6g−F480+CD11c−CD11b+ interstitial macrophages. l, Composition of CD45+Ly6g−F480+CD11c−CD11b+Ly6chigh infiltrating macrophages. Data shown mean ± SD, P values indicated, one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons Bonferroni test (b, c, e, g, j-l).

Extended Data Fig. 3. Single cell RNA-Seq analysis of lungs from CS-exposed mice treated with LTβR-Ig.

Cells from whole lung suspensions of B6 mice exposed to FA (n=3) or CS for 6m, plus LTβR-Ig fusion protein (n=5) or control Ig (n=5) therapeutically from 4 to 6m, were analysed at 6m by scRNA-Seq (Drop-Seq). a, Heat map depicting the expression of key genes used in identifying the individual cell populations. b, UMAP of scRNA-Seq profiles (dots) coloured by experimental group. c, UMAP plots showing expression of genes indicated in scRNA-Seq profiles. d, Dot blot depicting the expression level (log transformed, normalised UMI counts) and percentage of cells in a population positive for Ltb, Lta, Tnf, Tnfsf14, Ltbr, Tnfrsf1a and Tnfrsf1b. e, UMAP plot showing the relative intensity of the positive regulation of NIK (non-canonical) NFκB signalling pathway (GO:1901224) across the scRNA-Seq profiles. f, UMAP plot of scRNA-Seq profiles (dots) of lung epithelial cells coloured by experimental group (left) and the relative intensity of the positive regulation of NIK (non-canonical) NFκB signalling pathway (GO:1901224) (right). g, Box and whiskers plot (box representing 25th-75th percentile, median line indicated and Tukey whiskers representing +/− 1.5 IQR) showing the relative score for the positive regulation of NIK (non-canonical) NFκB signalling pathway in the cell types indicated across the three groups. Statistical significance is indicated and was assessed using Wilcoxon rank-sum two-sided test on normalized, log transformed count values and corrected with Benjamini-Hochberg.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Analysis of Lta and LTb expression in human and murine lungs.

a, Representative images of in situ hybridisation analysis for LTA and immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis for LTB in lung sections from healthy and COPD patients (n=4, red signal indicated by arrow heads (LTA), brown signal (LTB) and haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 50μm. b, Representative images of in situ hybridisation analysis for Lta and Ltb in lung sections from B6 mice exposed to CS for 6m with LTβR-Ig fusion protein or control Ig (80 μg i.p., weekly) therapeutically for 4 to 6m, and analysed at 6m (n=4 mice/group, repeated twice), (brown positive staining (Lta) and red positive staining (Ltb) indicated by arrow heads, open arrow head unstained cells, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 20μm). Non-staining with sense probe in CS+Ig sections shown as negative control. Representative images of immunohistochemical analysis identifying CD68 positive macrophages (brown staining indicated by arrow heads) also shown. c, Representative images of in situ hybridisation analysis for Tnfsf14 (Light) in lung sections from mice described in (b) (n=4 mice/group) (brown positive staining indicated by arrow heads, open arrow head unstained cells, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 20μm), plus a spleen section shown as positive control. d, Representative images of in situ hybridisation analysis for Tnf in lung sections from mice described in (b) (brown positive macrophage indicated by arrow heads, open arrow head unstained macrophage, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 20μm). Representative immunohistochemical analysis identifying CD68 positive macrophages (brown staining indicated by arrow heads, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 20μm) also shown. e, Quantification of Tnf positive macrophages across 20 random fields of view per lung (n=4). Data shown mean ± SD. P values indicated, one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons Bonferroni test.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Inhibition of LTβR-signalling strongly reduces non-canonical but not canonical NF-κB-signalling in lung.

a, Principal component analysis of microarray data, using Mouse Ref-8 v2.0 Expression BeadChips (Illumina), undertaken on lung tissue from mice exposed to FA or CS for 6m, plus LTβR-Ig fusion or control Ig (80 μg i.p., weekly) therapeutically from 4 to 6m (n=3 mice/group). b, Principal component analysis of normalised z-scored MS-intensities from proteomics of whole lung lysates from mice exposed to FA (n=6) or CS for 6m, plus LTβR-Ig fusion (n=7) or control Ig (n=4) (80 μg i.p., weekly) from 4 to 6m. c, Heat map depicting the top 20 up and down LTβR-Ig regulated genes presented as fold change (FDR<10%) from the microarray data described in (a). Left, expression in CS+Ig relative to FA – exposed mice; Right, expression in CS+LTβR-Ig relative to CS+Ig – exposed mice. d, GSEA of the NIK (non-canonical) NF-κB signalling (GO:0038061) pathway of the microarray data from (a). e, Heat map of significantly regulated proteins from the NIK (non-canonical) NF-κB signalling (GO:0038061) pathway as determined by Student’s T-test Test statistic from the proteomics data described in (b). f, GSEA of the NIK (non-canonical) NF-κB signalling (GO:0038061) pathway of the normalised proteome data described in (b). g, Representative images of two independent experiments of immunohistochemical analysis for RelB in lung sections from B6 mice exposed to FA or CS for 4 and 6m, plus LTβR-Ig fusion or control Ig (80 μg i.p., weekly) prophylactically from 2 to 4m and analysed at 4m, and therapeutically from 4 to 6m and analysed at 6m (brown signal indicated by arrow heads, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 25μm). h, Quantification of RelB positive alveolar epithelial nuclei from the IHC sections in (g), n=3 mice/group. i, Representative images of two independent experiments of immunohistochemical analysis for RelA in lung sections from the mice described in (g) (brown signal indicated by arrow heads, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 25μm). j, Quantification of RelA positive alveolar epithelial nuclei from the IHC sections in (i), n=3 mice/group. k, mRNA expression levels of Ccl2, Ccl3, Cxcl1 and Tnf determined by qPCR in whole lung from the mice described in (g), n=4 mice/group, repeated twice, pooled data shown. l, mRNA expression levels of LTA, CXCL13 and TNF determined by qPCR in ex vivo human precision-cut lung slices stimulated for 24h with LPS (10μg/ml) in the presence or absence of human LTβR-Ig fusion protein (1μg/ml) (n=3 independent experiments from 3 separate lungs). Left image shows a representative picture of preparing a lung slice from the 3 independent experiments. Data shown mean ± SD. P values indicated, one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons Bonferroni test.

Extended Data Fig. 6. LTβR-Ig treatment reverses airway remodeling and comorbidities in chronic CS-exposed mice.

a, Representative images of Masson’s Trichrome stained lung sections (scale bar 200μm) from B6 mice exposed to FA or CS for 4 and 6m, plus LTβR-Ig fusion protein or control Ig (80 μg i.p., weekly) prophylactically from 2 to 4m and analysed at 4m, and therapeutically from 4 to 6m and analysed at 6m (n=4 mice/group, repeated twice). These are low magnification images of the sections depicted and quantified in Fig. 2c,d. b, Representative images of immunohistochemical analysis for collagen I (red signal, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 100μm) in lung sections from B6 mice described in (a). c, Quantification of small airway collagen deposition normalised to the surface area of airway and vessel basement membrane from the sections in (b), (n=7 mice FA, 7 mice CS+Ig, 7 mice CS+LTβR-Ig groups, from 2 independent experiments). d, Representative images of immunohistochemical analysis for phosphorylated Smad2 in lung sections from mice described in (a, n=4 mice/group, repeated twice) (red signal indicated by arrows, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 25μm). e, mRNA expression levels of Ppargc1a and Mcat determined by qPCR in gastrocnemius muscle from 6m mice described in (a) (n=4 mice/group, repeated twice, pooled data shown). f, 4-paw muscle strength test in mice at 6m treated as described in (a) (n=8 mice/group). g, Schematic representation of the LTβR-Ig treatment protocol in aged mice. h, Representative images of H/E and Masson’s Trichrome stained lung sections (scale bar 50μm) from 12m old B6 mice exposed to FA or CS for 4m, plus LTβR-Ig fusion protein or control Ig (80 μg i.p., weekly) from 2 to 4m and analysed at 4m. (n=5 mice FA, 5 mice CS+Ig, 7/8 mice CS+LTβR-Ig groups, repeated twice. These are low magnification images of the sections depicted and quantified in Fig. 2f,g.) Data shown mean ± SD. P values indicated, one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons Bonferroni test (c), Student’s two-tailed t test (e-f).

Extended Data Fig. 7. Disease development is not attenuated by LTβR-Ig treatment in iBALT independent emphysema.

a, Schematic representation of the LTβR-Ig treatment protocol in mice exposed to a single oropharangeal application of porcine pancreatic elastase (PPE) or PBS control. b, mRNA expression level fold changes (FC) of Lta, Tnfsf14 (Light), Ltbr and Tnf relative to Hprt, determined by qPCR in whole lung from B6 mice treated with a single oropharyngeal application of PBS (n=8), porcine pancreatic elastase (PPE, 40 U/kg body weight) analysed after 3m (n=7) or 4m chronic cigarette smoke exposure (CS) (n=8 mice/group). c, Representative images of immunohistochemical analysis for B220 positive B cells and CD3 positive T cells (brown signal, indicated by arrow heads, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 50μm) in lung sections from PBS and PPE treated mice described in (b) plus mice treated with PPE followed by LTβR-Ig fusion protein (80 μg i.p., weekly) 28d later for 2m (n=8 mice/group, repeated twice). d, Lymphocyte counts in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) from the mice described in (c) plus mice exposed to CS for 4m (n=8 mice/group). e, Representative images of in situ hybridisation analysis for Lta and Ltb in lung sections from mice described in (c), plus splenic positive controls, (brown staining, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 50μm) (n=4 mice/group, repeated twice). f, Representative images of immunohistochemical analysis for RelA and RelB in lung sections from B6 mice described in (c) (brown signal indicated by arrow heads, haematoxylin counter stained, scale bar 50μm) (n=4 mice/group, repeated twice). g, Representative images of H/E stained lung sections (scale bar 200μm and 50μm inset) from the lungs of mice described in (c) (n=8 mice/group, repeated twice). h, Emphysema scoring (1–5, 5 most severe) of lung sections from (f) (n=5 mice PBS, 5 mice PPE, 7 mice PPE+LTβR-Ig groups). i, Diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide (DFCO) in the lungs of mice described in (c) (n=8 mice PBS, 7 mice PPE, 8 mice PPE+LTβR-Ig groups). j, Dynamic compliance (Cdyn) pulmonary function data from the mice described in (c) (n=8 mice PBS, 7 mice PPE, 8 mice PPE+LTβR-Ig groups). Data shown mean ± SD. P values indicated, one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons Bonferroni test.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Inhibiting LTβR-signalling suppresses CS-induced apoptosis.