Abstract

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most widespread internal mRNA modification in humans. Despite recent progress in understanding the biological roles of m6A, the inability to install m6A site-specifically in individual transcripts has hampered efforts to elucidate causal relationships between the presence of a specific m6A and phenotypic outcomes. Here we demonstrate that nucleus-localized dCas13 fusions with a truncated METTL3 methyltransferase domain and cytoplasm-localized fusions with a modified METTL3:METTL14 methyltransferase complex can direct site-specific m6A incorporation in distinct cellular compartments, with the former fusion protein having particularly low off-target activity. Independent cellular assays across multiple sites confirm that this targeted RNA methylation (TRM) system mediates efficient m6A installation in endogenous RNA transcripts with high specificity. Finally, we show that TRM can induce m6A-mediated changes to transcript abundance and alternative splicing. These findings establish TRM as a tool for targeted epitranscriptome engineering to help reveal the effect of individual m6A modifications and dissect their functional roles.

Editorial summary

The most abundant RNA modification in humans, m6A, can be installed at specified RNA sequences in cells, enabling functional studies.

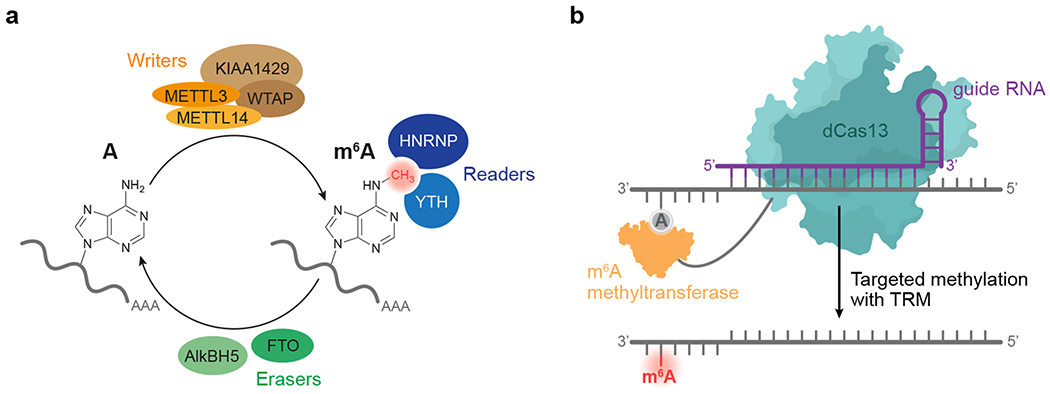

Dynamic covalent modifications to DNA and proteins play fundamental roles in regulating gene expression1. RNA has recently been shown to tune gene expression through its own set of post-transcriptional modifications, including pseudouridine (Ψ), 5-methylcytosine (m5C), N1-methyladenosine (m1A), and N6-methyladenonsine (m6A)2,3. Among known endogenous cellular RNA modifications, m6A is the most abundant within eukaryotic mRNA4, and has been demonstrated to alter chromatin accessbility5, RNA splicing6, nuclear export of RNA7, RNA stability8,9 and translation efficiency10 (Fig. 1a). Advances in high-throughput sequencing techniques for transcriptome-wide m6A mapping11,12 have also linked m6A to a wide range of cellular functions, including stem cell proliferation and differentiation13, cellular heat shock response14, spermatogonia differentiation15, maternal-to-zygotic transition16, X-chromosome inactivation17, DNA damage response18, circadian clock function19, tumorigenesis20, long-term memory creation21, and anti-tumor immunity22. Aberrant m6A methylation has also been implicated in diseases such as acute myeloid leukemia and glioblastoma23–25. Despite a growing appreciation of the importance of m6A and other RNA modifications in biology and disease, our understanding of their specific functions continues to lag far behind that of many DNA and protein modifications, in part because of the lack of methods to site-specifically install RNA modifications in a target transcript in living cells.

Figure 1. Overview of cellular modification of adenine to m6A in mRNA, and design of a targeted RNA methylation system.

(a) METTL3 and METTL14 form a “writer” complex that catalyzes S-adenosyl methionine (SAM)-dependent methylation of the N6 of adenine in cellular mRNA. Additional components influence the formation and activity of this core complex. FTO and ALKBH5 (“erasers”) remove the methyl group of m6A. “Readers” recognize the mark on RNA and direct it to various outcomes. (b) Proposed strategy for targeted RNA methylation (TRM). A programmable RNA-binding protein such as dCas13 when fused to an appropriate methyltransferase complex mediates the guide RNA-specified methylation of A to m6A site-specifically in a target transcript.

In humans, methylation of mRNA to form m6A is mediated by a 184-kD heterodimer of methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) and methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14)26 (Fig. 1a). Within this complex, METTL3 catalyzes the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) to adenine within the ssRNA sequence motif DRACH (D=A, G, or U; R=A or G; H=A, C, or U), while METTL14 scaffolds substrate RNA binding27–29. Along with associated accessory proteins that regulate its activity, METTL3:METTL14 co-transcriptionally methylates nascent mRNA within nuclear speckles30. Opposing this m6A “writer” complex, AlkB homolog 5 (AlkBH5) and fat-mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) oxidatively demethylate m6A within the same DRACH motif, thus serving as “erasers”31,32. Within mRNA transcripts, m6A modifications recruit “reader” proteins from the m6A-recognizing YT521-B homology33 (YTH) or heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) families34,35 (Fig. 1a). Upon binding m6A, these readers affect RNA splicing, nuclear export, translation, and degradation to ultimately alter the cellular abundance of methylated transcripts and their protein products36–38. Together, these components are thought to install, remove, and read m6A modifications in mRNA to post-transcriptionally coordinate gene expression.

The current study of m6A in biological processes relies on global knock down or overexpression of these m6A writers, erasers, and readers within cells. While illuminating, such studies are limited by the bulk nature of these experiments in which the methylation state of tens of thousands of sites on many transcripts are altered, rather than focusing methylation on a single site within a transcript of interest. Tools that instead mediate programmable installation of m6A39 would enable the functional interrogation of specific m6A sites and more directly reveal causal relationships between individual m6A modifications and phenotype.

The CRISPR-associated nuclease Cas13 has been shown to bind and cleave single-stranded RNA targeted by a complementary guide RNA40–42. We speculated that tethering catalytically inactivated Cas13 (dCas13) to m6A writers could allow programmable installation of m6A at sites specified by a Cas13 guide RNA. In this study we elucidate m6A methyltransferase kinetics in vitro, fuse modified methyltransferase components to dCas13, characterize activity in bacteria and mammalian cells, and ultimately establish a targeted RNA methylation system (TRM) that enables site-directed m6A installation in target transcripts in both the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 1b). Using transcriptome-wide MeRIP-seq and differential RNA-seq, we show that off-target methylation from TRM, while detectable, is limited in scope in both bacteria and human cells. Lastly, we effect m6A-mediated changes in RNA abundance and alternative splicing using TRM, thereby demonstrating its functional utility. By enabling programmable methylation of specific adenines within transcripts of interest with minimal perturbation of background methylation states, TRM will facilitate the elucidation of causal relationships between m6A and biological phenotype.

Results

In vitro characterization of m6A methyltransferase

An ideal targeted RNA methylation system maximizes the likelihood that m6A installation occurs at the target site(s) rather than at the vast excess of non-target As in the transcriptome. To achieve high TRM specificity, we envisioned that using an m6A methyltransferase domain with impaired substrate engagement (reflected by a modest Km) but strong catalytic activity (kcat) would make RNA methylation highly dependent on the binding of a fused dCas13 domain to the target RNA. The increase in effective molarity of RNA upon dCas13 binding in principle should selectively overcome the modest Km for on-target RNA loci, imparting specificity.

As only METTL3 contains a SAM-dependent active site within the METTL3:METTL14 m6A writer complex27–29, we hypothesized that METTL3 could methylate adenine on its own and serve as a binding-impaired methyltransferase, ideal for fusion to a programmable RNA-binding protein such as dCas13. To explore this idea, we purified and measured the kinetics of METTL3 alone and the METTL3:METTL14 complex by monitoring the transfer of 14C from a radiolabeled SAM cofactor to an RNA substrate43. Although the Vmax of METTL3 was reduced ~3 fold in the absence of METTL14, its Km was impaired by more than 40-fold, from 18 nM for METTL3:METTL14 to >900 nM for METTL3 (Supplementary Fig. 1). These data suggest that METTL3 or METTL3 variants may serve as ideal fusion partners to dCas13 in a TRM system, as the elevated local concentration of RNA upon dCas13 binding to the target transcript can rescue the high Km of METTL3 alone and provide specificity for the target RNA.

Design of TRM candidate fusions

Using these insights, we selected Km-impaired adenosine methyltransferases to fuse to dCas13. To further weaken non-specific RNA-binding affinity of full-length METTL3, we removed the zinc finger RNA-binding motifs from METTL3 to create METTL3ΔZF, referred to as M3 hereafter. While M3 could not be expressed and purified in E. coli in amounts sufficient for kinetic characterization, it proved to be an active and useful methyltransferase in experiments described below. In addition to M3, we also fused M3 to the METTL3-interacting domain of METTL14 (residues 111-456, referred to as M14 hereafter) as a second binding-impaired methyltransferase candidate. Inspection of the METTL3:METTL14 heterodimer structure bound to SAM (PDB 5IL1)28 revealed that an M14–linker–M3 fusion architecture could sterically occlude the native conformation of the heterodimer (Supplementary Fig. 2a). We therefore proceeded with M3 and M3–(GGS)10–M14 (hereafter referred to as M3M14) as candidate methyltransferases to develop programmable RNA methylation systems.

We fused M3 and M3M14 to a catalytically inactive Cas13b variant from Prevotella sp. P5-125 (PspCas13b Δ984-1090 H133A, referred to as dCas13 hereafter) due to its reported RNA targeting activity in RNA base editors44,45. Examination of the crystal structure of Prevotella buccae Cas13b (PbuCas13b, PDB 6DTD)46, which shares 40% homology with PspCas13b, showed that the N-terminus is buried within the core of the protein (Supplementary Fig. 2b). We therefore tethered dCas13 by its C-terminus to M3 (dCas13–M3) and M3M14 (dCas13–M3M14) using flexible XTEN and (SGGS)2-XTEN-(SGGS)2 linkers47, respectively (Fig. 2a).

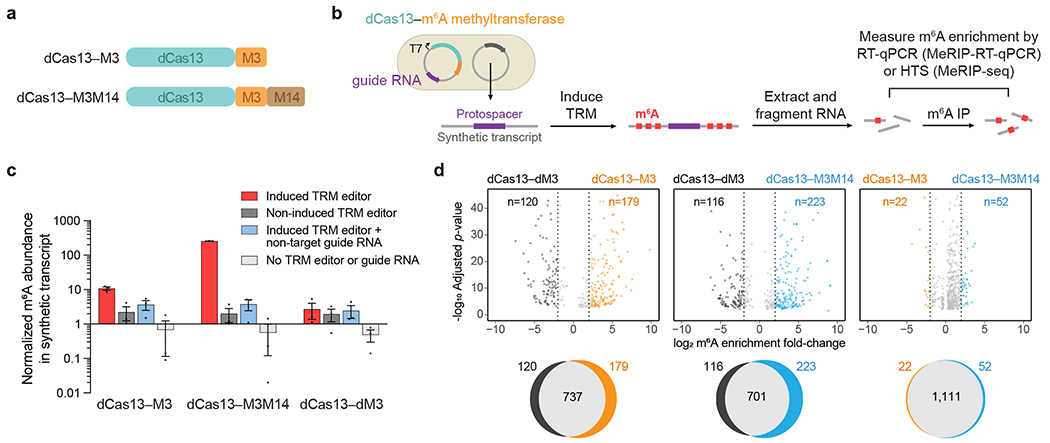

Figure 2. Validation of targeted RNA methylation (TRM) in E. coli.

(a) METTL3273-580 (M3) or METTL3359-580–(GGS)10–METTL14111-456 (M3M14) methyltransferases were fused to catalytically-impaired PspCas13b Δ984-1090 (dCas13) to generate dCas13–M3 or dCas13–M3M14 TRM editors. (b) Plasmids transformed into E. coli encode IPTG-inducible TRM editors with a guide RNA targeting a synthetic transcript. After targeted methylation, cellular total RNA was purified, fragmented, and immunoprecipitated with anti-m6A antibodies. Enrichment of m6A was measured by target-specific RT-qPCR (MeRIP-RT-qPCR) or transcriptome-wide high-throughput sequencing (MeRIP-seq). (c) Target transcript m6A abundance measured by MeRIP-RT-qPCR under four conditions: induced TRM editor with transcript-targeting guide, non-induced editor with transcript-targeting guide, induced editor with a non-target guide, and cells lacking TRM editor and guide plasmid. The methyltransferase-inactive control was dCas13–M3D395A (dCas13–dM3). Values and error bars reflect the mean±s.e.m. of n=3 independent biological replicates. (d) Top: differential m6A enrichment of all methylated adenines in E. coli expressing synthetic transcript-targeting guide RNAs and the indicated TRM editors. For the comparisons above, only differentially methylated sites with statistical significance (P<0.001) are shown. Bottom: Venn diagrams depicting overlap of all methylated m6A sites for the above comparisons. 42,418 total m6A motifs (RRACH) are susceptible to modification within the E. coli transcriptome. MeRIP-seq analysis was performed with n=3 independent biological replicates. Statistical significance was calculated using a logs likelihood-ratio test with false discovery rate correction.

Validation of TRM in bacteria

To evaluate these candidate TRM constructs in a cellular context, we first targeted RNA methylation in bacteria. We introduced into E. coli a DNA plasmid encoding dCas13-methyltransferase fusions under an IPTG-inducible promoter and a constitutively-expressed Cas13 guide RNA. A second plasmid encoded a synthetic target transcript containing m6A methylation motifs (GGACU) surrounding a guide RNA-targeting sequence (Fig. 2b). To measure m6A modification of the target transcript, we used RT-qPCR to quantify enrichment of RNA fragments immunoprecipitated with m6A antibodies (MeRIP-RT-qPCR). We observed substantial m6A methylation of the target substrate only upon induction of dCas13–M3 or dCas13–M3M14 expression, but not a catalytically impaired mutant methyltransferase, dCas13–M3D395A (dCas13–dM3) (Fig. 2c). Co-expression of active dCas13–methyltransferase fusions with a non-targeting guide RNA also resulted in minimal target methylation, establishing that guide RNA targeting is necessary for m6A installation. We confirmed these findings with an orthogonal m6A measurement assay in which we selectively captured the target transcript and detected m6A by immunostaining (Supplementary Fig. 3). Collectively, these results demonstrate the ability of both dCas13–M3 and dCas13–M3M14 to methylate RNA targets in a guide RNA-programmed manner.

To assess the specificity of TRM editors in E. coli, we extracted and fragmented cellular mRNA after editing, then sequenced the RNA fragments enriched with m6A antibodies (MeRIP-seq)11,48. For each sample, we evaluated the number of modified sites out of 42,418 RRACH m6A motifs susceptible to off-target methylation within the E. coli transcriptome. We found that dCas13–M3 and the inactive dCas13–dM3 control produced 916 and 857 modified m6A sites, respectively, of which a large majority (737) were shared in both conditions and only 179 of 42,418 possible sites were hypermethylated by dCas13–M3 (Fig. 2d). In comparison, the more active dCas13–M3M14 construct induced the methylation of 924 sites, of which 223 of 42,418 possible sites were hypermethylated compared to the inactive methylase control. These results suggest that dCas13–M3 and dCas13–M3M14 in E. coli promote modest off-target RNA modification that correlates with their methylation activity.

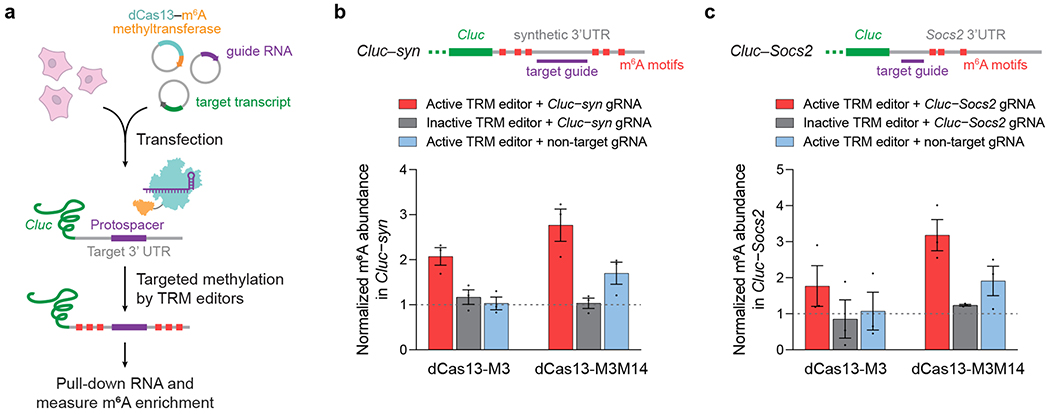

Methylation of reporter transcripts in mammalian cells

Next, we sought to test site-specific m6A installation in human cells. We designed guide RNAs targeting a synthetic RNA substrate placed on the 3’ UTR of Cypridina luciferase (Cluc) mRNA, then targeted m6A motifs surrounding the substrate’s protospacer sequence with TRM editors transfected in HEK293T cells (Fig. 3a). MeRIP-RT-qPCR of this synthetic reporter (Cluc–syn) revealed increased (2- to 3-fold) methylation from reporter-targeted dCas13–M3 and dCas13–M3M14, but none from methyltransferase-inactive constructs (Fig. 3b). We observed a smaller increase (1.5-fold) in m6A modification from dCas13–M3M14 when combined with a non-targeting guide RNA, suggesting modest off-target methylation by this construct. We confirmed these results by targeting a second reporter transcript, in which we fused the endogenous 3’ UTR of the suppressor of cytokine signaling (Socs2) transcript onto Cluc (Fig. 3c). We detected similar increases in m6A incorporation by dCas13–M3 and dCas13–M3M14 (1.8- to 3-fold, respectively), and once again observed modest reporter methylation (2-fold) from non-targeted dCas13–M3M14.

Figure 3. Methylation of reporter transcripts in human cells.

(a) HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids encoding a TRM editor, Cas13 guide RNA, and the targeted Cluc reporter transcript containing a 3’ UTR methylation target. (b) Methylation of a synthetic 3’ UTR fused to Cypridina luciferase (Cluc–syn) by TRM editors. (c) Methylation of the Socs2 3’ UTR fused to Cypridina luciferase (Cluc–Socs2) by TRM editors. Inactive TRM editors contain a methyltransferase-inactivating D395A mutation within M3. Values and error bars reflect the mean±s.e.m. of n=3 independent biological replicates.

We performed transcriptome-wide MeRIP-seq of these TRM fusions targeting the Cluc–Socs2 reporter to further characterize their site-specificity in human cells. In agreement with MeRIP-RT-qPCR results, MeRIP-seq revealed elevated m6A enrichment at the targeted site in the presence of dCas13–M3 and dCas13–M3M14 with active methyltransferases and reporter-targeting guide RNAs (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b). We also observed a small increase in m6A levels from non-targeted dCas13–M3M14, but not dCas13–M3, providing further evidence of the former’s modest off-target activity. Despite these data, we only observed methylation at the intended Socs2 3’UTR m6A sites for both editors, suggesting a high degree of TRM specificity within the targeted RNA (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Taken together, these results indicate that dCas13 fusions to modified methyltransferase domains can selectively and efficiently install m6A on exogenous reporter RNAs in human cells, with dCas13–M3 offering especially low levels of off-target methylation.

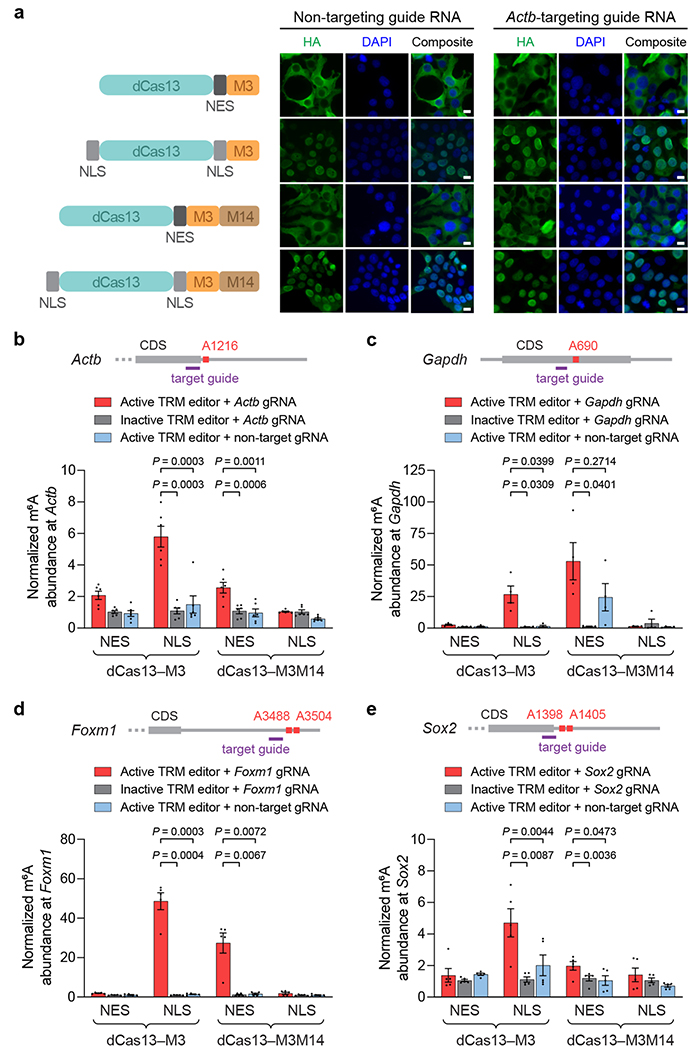

Engineered cytoplasm- and nucleus-localized TRM editors

Since human m6A readers exist within both the cytoplasm and nucleus, TRM editors localized to either part of the cell may access different RNAs and may have distinct biological properties. We therefore engineered cytoplasm- and nucleus-localized TRM construct variants by adding a nuclear export signal (NES) or nuclear localization signal (NLS) sequence to each, generating dCas13–M3nes, dCas13–M3nls, dCas13–M3M14nes, and dCas13–M3M14nls (Fig. 4a). We immunostained HEK293T cells transfected with editors bearing C-terminal HA epitopes, and confirmed that NES-tagged editors localized in the cytoplasm and both NLS-tagged editors localized in the nucleus (Fig. 4a). To investigate whether RNA targeting affects editor localization, we visualized constructs co-transfected with a guide RNA targeting the transcript of beta-actin (ACTB), which is known to mediate nuclear co-export of associated proteins49. Surprisingly, we observed that all editors still localized to their intended cellular compartments (Fig. 4a), suggesting minimal co-export of nucleus-localizing constructs with Actb mRNA. These findings demonstrate that the intracellular localization of TRM editors can be reliably controlled with localization tags.

Figure 4. Cellular localization of TRM editors and targeted methylation of endogenous transcripts in human cells.

(a) Left: nucleus- and cytoplasm-localized TRM editor variants. NES = nuclear export signal; NLS = nuclear localization signal. Right: representative immunofluorescence images of HEK293T cells transfected with HA-tagged TRM editors and non-targeting or Actb-targeting guide RNAs. Green = HA tag; blue = DAPI. Scale bars represent 10 μm. The experiment was independently performed twice with similar results. (b-e) Methylation by nucleus- and cytoplasm-localized TRM editors targeting endogenous (b) Actb A1216, (c) Gapdh A690, (d) Foxm1 A3488 and A3504, and (e) Sox2 A1398 and A1405. Guide RNAs used for targeting each transcript are shown in purple. Inactive TRM editors contain a methyltransferase-inactivating D395A mutation within M3. Values and error bars reflect the mean±s.e.m. of n=6 (b), n=4 (c), or n=5 (d,e) independent biological replicates. P values were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Next, we explored the possibility that dCas13 binding on its own may alter RNA stability or translation efficiency. We transfected HEK293T cells with nucleus- or cytoplasm-localized dCas13, a vector expressing a Cluc reporter transcript and Gaussia luciferase (Gluc) internal control, and guide RNAs targeting Cluc (Supplementary Fig. 5a). To assess RNA stability and translation of the targeted Cluc, we measured Cluc RNA abundance and luminescence activity. Using guides tiling the Cluc coding region, we observed that dCas13 binding did not affect Cluc RNA or protein levels (Supplementary Fig. 5b). As m6A modifications are more commonly found within mRNA UTRs11,48, we next targeted endogenous 5’ and 3’ UTRs fused to Cluc. We observed minimal alteration of Cluc RNA abundance or translation when we targeted dCas13 to the Nanog 3’ UTR fused to Cluc (Cluc–Nanog), or the Cluc–syn and Cluc–Socs2 3’ UTR reporters described above (Supplementary Fig. 5c). In contrast, targeting the 5’ UTRs of Hspa1a and Hsph1 fused to Cluc (Hspa1a–Cluc and Hsph1–Cluc, respectively) with cytoplasm-localized dCas13 resulted in up to a 61% decrease in Cluc protein production, but no effect on RNA abundance (Supplementary Fig. 5d). Interestingly, only cytoplasm-localized dCas13 caused this reduction, implying that 5’ UTR binding may interfere with ribosome scanning and RNA translation. Taken together, these experiments suggest that dCas13 targeting does not strongly affect RNA abundance, but can reduce translation efficiency at 5’ UTRs in cytoplasmic mRNA.

Methylation of endogenous transcripts in human cells

Using the above suite of cytoplasm- and nucleus-localized TRM editors, we sought to install m6A modifications on endogenous transcripts in HEK293T cells. We first targeted adenine A1216 within the 3’ UTR of Actb mRNA, which is methylated to a low degree in these cells50. Overexpression of METTL3 increased A1216 methylation, indicating that this site is regulated by endogenous m6A writers. (Supplementary Fig. 6a). To test if TRM can direct higher levels of m6A at this site in human cells, we measured Actb methylation resulting from all four TRM constructs with guide RNAs specific for a protospacer ending 8 bp 5’ of the Actb A1216 site.

After transfection of these components, we observed that dCas13–M3nls and dCas13–M3M14nes robustly installed m6A at Actb A1216, increasing methylation by 2- to 5-fold (Fig. 4b). Methyltransferase-inactive variants of these constructs, which are expressed at levels comparable to their active TRM counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 7), did not increase methylation. We also evaluated if an Actb-targeting guide RNA with the M3 or M3M14 methyltransferase domains alone but without dCas13 could promote dCas13-independent methylation. These components lacking dCas13 produced no increase in Actb methylation above that of non-targeting controls (Supplementary Fig. 6b), confirming that dCas13 is required for targeted methylation. To validate these results with an additional endogenous target transcript, we targeted A690 within the coding region of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA, which is also methylated to a low extent (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Consistent with the above results, we detected substantial Gapdh methylation by dCas13–M3nls and dCas13–M3M14nes in a manner dependent on a Gapdh-targeting guide RNA, active methyltransferase, and their fusion to dCas13 (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 8b,c).

To demonstrate TRM editing at biologically important m6A sites, we next targeted the transcripts of forkhead box protein M1 (FOXM1), for which hypomethylation has been implicated in glioblastoma51,52, and SRY-box 2 (SOX2), for which methylation mediates stem cell differentiation53. While both transcripts are endogenously methylated in HEK293T cells12, they were amenable to further m6A modification by METTL3 overexpression (Supplementary Fig. 9a and 10a). To determine if TRM editors could stimulate greater Foxm1 and Sox2 methylation, we used guide RNAs specific for their 3’ UTR m6A sites. In agreement with results for Actb and Gapdh targets, we found that dCas13–M3nls and dCas13–M3M14nes significantly increased m6A levels of Foxm1 (50- and 28-fold, respectively) and Sox2 (4- and 1.7-fold, respectively) only when fused to dCas13 and supplied with targeting guide RNAs and active methyltransferase (Fig. 4d,e and Supplementary Fig. 9b and 10b).

To confirm these results with an antibody-independent, single-base resolution method, we measured site-specific m6A incorporation using MazF-qPCR54,55, which exploits the ability of m6A to disrupt cleavage of ACA motifs by the ssRNA ribonuclease MazF (Supplementary Fig. 11a)56. Applying this method to probe two targeted adenines amenable to this approach, Gapdh A690 and Sox2 A1398, we observed reduced MazF digestion of both m6A sites edited by only dCas13–M3nls and dCas13–M3M14nes compared to methyltransferase-inactive editor and non-targeting guide RNA controls (Supplementary Fig. 11b,c). These results indicate increased m6A modification of these targeted adenines, consistent with MeRIP-RT-qPCR results. Collectively, these results from two orthogonal methylation assays across four target transcripts establish that dCas13–M3nls and dCas13–M3M14nes can site-specifically install m6A in a programmable manner.

Targeting specificity of TRM

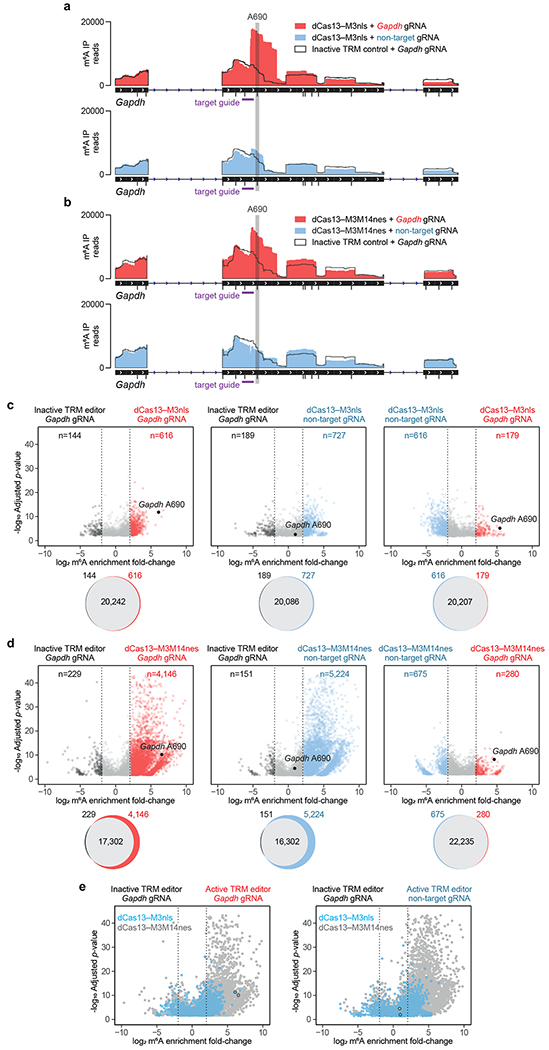

Next, we elucidated the editing window of these two most active TRM constructs (dCas13–M3nls and dCas13–M3M14nes). We first targeted Gapdh A690 with a guide RNA positioned 8 bp 5’ of the site, then measured methylation across the entire Gapdh transcript using MeRIP-seq. This experiment revealed substantially elevated m6A levels at only the intended site within Gapdh, suggesting that TRM editors can achieve site specificity within the target mRNA (Fig. 5a,b). We similarly targeted Actb A1216 with TRM editors and also observed increased methylation at only this m6A site within Actb mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 12a,b). To further characterize the TRM editing window, we tiled guide RNAs at varying distances from Actb A1216 and Gapdh A690, then measured their methylation by dCas13–M3nls and dCas13–M3M14nes. For both editors, we detected maximal Actb and Gapdh methylation using guide RNAs targeting 30 bp sites that end 8-15 bp 5’ of the target adenine (Supplementary Fig. 13a,b). These results together suggest that TRM editors are most active ~10 bp 3’ of the targeted protospacer on an RNA substrate and can install m6A at defined adenines within a chosen transcript.

Figure 5. Specificity and off-target methylation of TRM editors.

(a,b) Gapdh read coverage of m6A-immunoprecipitated (m6A IP) RNA from MeRIP-seq of transfected HEK293T cells. Gapdh A690 was targeted with (a) dCas13–M3nls or (b) dCas13–M3M14nes with the following conditions: active editor with a target guide RNA, inactive editor with a target guide RNA, and active editor with a non-target guide RNA. All DRACH motifs susceptible to TRM modification are shown as black tick marks underneath the IGV track. The target guide RNA (purple) and targeted A690 site (grey) are shown. (c,d) Differential m6A enrichment of >21,000 methylated sites in HEK293T cells transfected with (c) dCas13–M3nls or (d) dCas13–M3M14nes and Gapdh A690-targeting or non-target guide RNAs. Top: differential methylation of m6A sites between conditions indicated above. Only differentially methylated sites with statistical significance (P<0.001) are shown. Bottom: Venn diagrams depicting overlap of all methylated m6A sites for the above comparisons. (e) Overlay of dCas13–M3nls (blue) and dCas13–M3M14nes (grey) differential methylation with the following comparisons: left, active editors with Gapdh guide RNAs vs. inactive editors with Gapdh guide RNAs; right, active editors with non-target guide RNAs vs. inactive editors with Gapdh guide RNAs. The targeted Gapdh A690 site is outlined in black. Inactive TRM editors contain a methyltransferase-inactivating D395A mutation within M3. MeRIP-seq analysis was performed with n=5 independent biological replicates. Statistical significance was calculated using a logs likelihood-ratio test with false discovery rate correction.

Even a small editing window of ~10 bp likely contains multiple adenines susceptible to methylation by TRM. However, we hypothesized that TRM editors might inherit the intrinsic DRACH sequence context preference of METTL3:METTL14, which would confine TRM editing to bona fide m6A motifs and confer greater specificity for a targeted m6A site. To test this hypothesis, we determined the consensus sequence of m6A-immunoprecipitated RNA fragments in MeRIP-seq, comparing background m6A peaks to those newly installed by TRM. Neither dCas13–M3nls nor dCas13–M3M14nes substantially changed the total cellular m6A consensus sequence compared to the inactive control (Supplementary Fig. 14). As the average mRNA contains only 3-5 candidate sites for m6A modification3,38, these findings suggest that TRM may be suitable to target a single adenine within a specified transcript.

Off-target methylation by TRM editors in human cells

To ensure that high TRM activity does not result in substantial non-specific methylation, we next characterized their transcriptome-wide off-target editing. We first measured the effect of TRM methylation on the total m6A content within human cells by capturing cellular mRNA and staining with anti-m6A antibodies. Compared to a methyltransferase-inactive control, dCas13–M3nls produced no significant difference in m6A abundance (Supplementary Fig. 15). However, dCas13–M3M14nes modestly increased m6A levels by 1.3-fold, suggesting a higher degree of off-target methylation for this pseudo-heterodimeric TRM construct.

To determine whether these changes in m6A content affect the distribution of transcriptome-wide RNA methylation, we targeted Gapdh A690 with both TRM editors and profiled changes in global m6A peaks using MeRIP-seq. In agreement with MeRIP-RT-qPCR data, we observed >50-fold m6A enrichment of A690 by dCas13–M3nls and dCas13–M3M14nes when co-transfected with a Gapdh-targeting guide RNA, but not a non-targeting guide RNA (Fig. 5c,d). Examining the rest of the transcriptome revealed that dCas13–M3nls, compared to an inactive control, installed only 600-750 additional m6A markers out of >21,000 detected, regardless of the guide RNA used (Fig. 5c). In contrast, dCas13–M3M14nes induced 4,000-5,500 new m6A peaks (out of >21,000 detected) (Fig. 5d). To further probe this effect, we targeted Actb A1216 and found similar levels of non-specific methylation, with dCas13–M3M14nes generating 3- to 6-fold more off-target m6A peaks than dCas13–M3nes (Supplementary Fig. 16a,b). These dCas13–M3M14nes off-targets tended to cluster on sites with low endogenous methylation, whereas dCas13–M3nls off-targets did not show this bias (Supplementary Fig. 17a,b). Consistent with this trend, dCas13–M3M14nes alters the global distribution of m6A within mRNAs and lncRNAs to a larger extent than dCas13–M3nls (Supplementary Fig. 18a–e). Taken together, these data indicate that dCas13–M3M14nes methylates its non-specific substrates to a substantially greater degree than dCas13–M3nls (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 16c), without a clear benefit in on-target activity.

To examine whether this off-target methylation from TRM editors is sufficient to perturb a substantial fraction of the transcriptome, we performed differential RNA-seq analysis on dCas13–M3nls and dCas13–M3M14nes co-transfected with a non-targeting guide RNA. Comparison of these constructs to methyltransferase-inactive controls revealed very few (<40 out of >15,000 total genes analyzed) genes with significantly (FDR-corrected p<0.05 and >2-fold change) altered transcript abundances (Supplementary Fig. 19a,b), suggesting that off-target methylation does not by itself appreciably alter levels of cellular transcripts.

Next, we compared TRM editors to a recently described m6A editor system39 in which a METTL3-METTL14 single-chain methyltransferase domain is fused to RNA-targeting Cas9. This M3M14–dCas9 writer, unlike TRM editors, requires the delivery of a synthetic PAMmer oligonucleotide in addition to a guide RNA for targeting transcripts. To evaluate the on-target and off-target activity of M3M14–dCas9, we transfected HEK293T cells with M3M14–dCas9, PAMmer, and guide RNAs targeting Actb A1216, then performed MeRIP-seq. We observed >50-fold on-target m6A enrichment over an inactive control, similar to results from MeRIP-seq of dCas13–M3nls and dCas13–M3M14nes (Supplementary Fig. 16a,b and 20a,b). However, M3M14–dCas9 supplied with non-targeting guide RNAs and PAMmers also resulted in >4-fold m6A enrichment of Actb A1216, suggesting a substantial degree of non-specific methylation. Consistent with these findings, M3M14–dCas9 targeting Actb installed 2,590 additional m6A modifications out of 16,800 detected (15.4%), comparable to the 3,116 off-target modifications out of 22,266 detected (14.0%) induced by dCas13–M3M14nes (Supplementary Fig. 16b and 20b). In contrast, dCas13–M3nls, which lacks a METTL14 RNA-binding domain, generated 5.5-fold lower frequency of off-target modifications (588 out of 21,017 detected, 2.8%) (Supplementary Fig. 16a). Thus, while all three m6A writer systems exhibit comparable on-target efficiency, only dCas13–M3nls offers much reduced off-target activity.

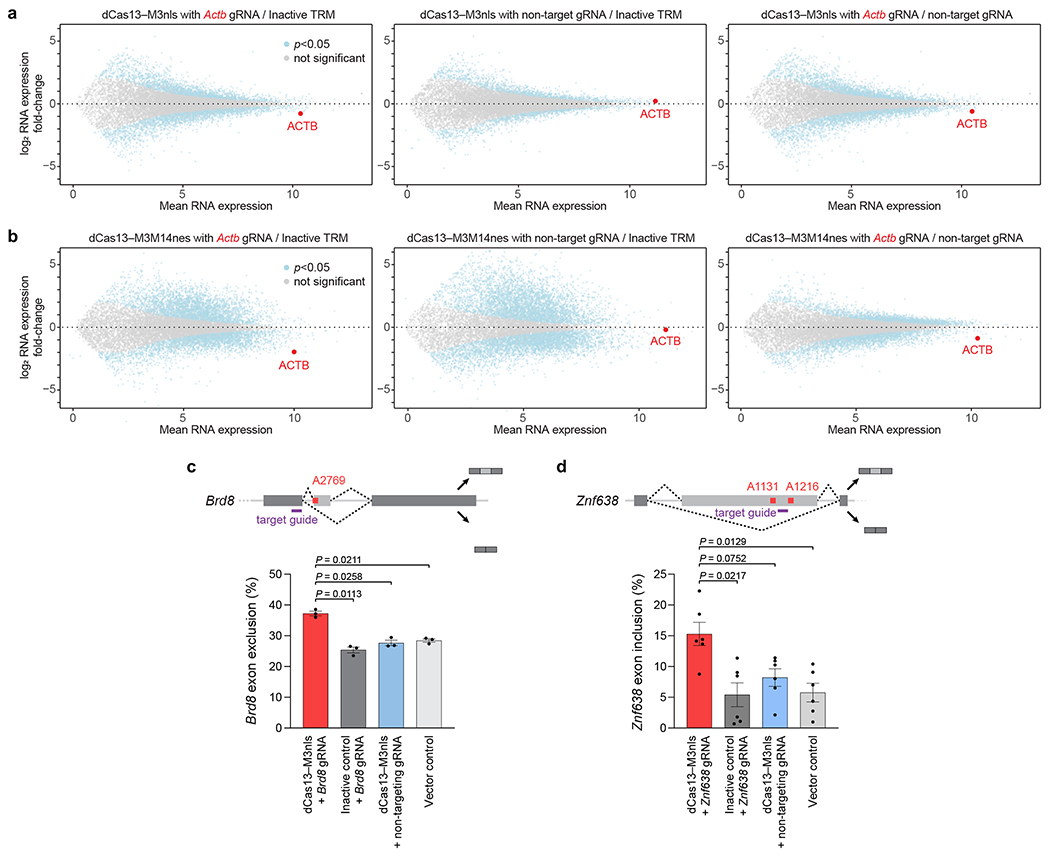

Targeted RNA perturbation with TRM

One major effect of altering adenine methylation is to increase or decrease the expression of methylated mRNA9,10. For example, Actb A1216 methylation has been previously reported to promote Actb degradation39. To explore whether the TRM editors characterized above can result in similar changes, we targeted Actb A1216 with dCas13–M3nls and dCas13–M3M14nes in HEK293T cells, then performed differential RNA-seq. Compared to methyltransferase-inactive and non-targeting guide RNA controls, dCas13–M3nls and dCas13–M3M14nes caused substantial 35-42% and 45-70% decreases in Actb mRNA levels, respectively (Fig. 6a, b). As expected, TRM editors co-transfected with non-targeting guides did not affect Actb RNA amounts. These findings show that site-specific methylation is required for triggering the reduction of Actb mRNA levels, demonstrating that TRM editors can direct m6A incorporation to influence m6A-dependent RNA processing.

Figure 6. TRM effect on RNA abundance and alternative splicing.

Differential RNA expression of HEK293T cells transfected with (a) dCas13–M3nls or (b) dCas13–M3M14nes and either Actb A1216-targeting or non-targeting guide RNAs. The targeted Actb gene is marked in red. Inactive TRM control indicates editors containing a methyltransferase-inactivating M3 D395A mutation with an Actb-targeting guide RNA. Non-target gRNA indicates methyltransferase-active TRM editors with a non-targeting guide RNA as a control. Differential RNA-seq analysis was performed with n=5 independent biological replicates. Statistical significance was calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test with false discovery rate correction. Alternative splicing of (c) Brd8 and (d) Znf638 in HEK293T cells transfected with dCas13–M3nls and the indicated guide RNAs (purple) for targeting m6A sites shown (red). Exon exclusion or inclusion indicates the percentage of RNA isoform lacking or containing the alternatively-spliced exon, respectively. Values and error bars reflect the mean±s.e.m. of n=3 (c) or n=6 (d) independent biological replicates. P values were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

We next targeted the methylation of Gapdh A690, which has not been shown to be a physiological m6A site in HEK293T cells. In contrast to the results for Actb, we observed that neither dCas13–M3nls nor dCas13–M3M14nes affected Gapdh transcript abundance (Supplementary Fig. 21a,b), despite the ability of both constructs to efficiently install m6A (Fig. 4c, 5a,b, and Supplementary Fig. 11b). The lack of RNA abundance changes from m6A incorporation in this transcript may reflect the lack of evidence that Gapdh A690 is interrogated by m6A readers.

In addition to its effect on RNA degradation, m6A has been found to mediate alternative splicing of modified pre-mRNA in the nucleus6,34,57,58. To determine whether nucleus-localized dCas13–M3nls could affect mRNA isoform abundances, we targeted an m6A site within the alternatively-spliced exon 21 of bromodomain-containing protein 8 (Brd8). We observed that methylation by dCas13–M3nls increased exon 21 exclusion by >30% (Fig. 6c), consistent with m6A’s known effect on Brd8 exon skipping57. Treatment with non-targeting guide RNAs or methyltransferase-inactive dCas13–dM3nls abolished this effect, indicating that exon exclusion is dependent on m6A installation. To investigate a second splicing target, we next methylated exon 2 of zinc finger protein 638 (Znf638) using dCas13–M3nls. Consistent with previous studies of m6A-mediated Znf638 splicing58, we detected >2-fold elevated Znf638 exon 2 inclusion driven by TRM activity (Fig. 6d). Taken together, these findings establish that TRM editors can induce two known biological consequences of m6A, the degradation and alternative splicing of targeted RNA substrates, through methylation of specific adenines.

Discussion

Here we coupled the RNA targeting capability of CRISPR-Cas13 with RNA methyltransferases that generate m6A to develop a targeted RNA methylation system for programmable manipulation of the epitranscriptome. We demonstrate that TRM operates broadly on a range of RNA targets with low off-targeting activity and can alter cellular processing of RNA in a methylation-dependent manner.

Beyond the clear difference in localization between the two TRM editors, dCas13–M3nls offers key advantages over dCas13–M3M14nes. First, dCas13–M3nls induces substantially less non-specific off-target methylation than dCas13–M3M14nes (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 16). Second, the nuclear localization of dCas13–M3nls allows targeting of mRNA 5’ UTRs without a reduction in translation efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 5). Finally, m6A installation by dCas13–M3nls within the nucleus preserves the opportunity for m6A-modified transcripts to be recognized and regulated by nuclear m6A readers, a feature we exploited to stimulate targeted changes in alternative RNA splicing (Fig. 6c,d). For these reasons, we recommend the use of dCas13–M3nls to minimize off-target activity, maximize TRM targeting scope, and allow the perturbation of m6A-mediated phenotypes within the nucleus. When cytoplasmic methylation is necessary, dCas13–M3M14nes offers an alternative.

These advantages of dCas13–M3nls distinguish the TRM system developed here from the recently reported M3M14–dCas9 m6A editor, which uses METTL3 and METTL14 fusions to RNA-targeting Cas939. We show that the lack of a METTL14 RNA-binding domain within dCas13–M3nls results in less off-target methylation compared to dCas13–M3M14nes and M3M14–dCas9 (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 16 and 20). In addition, TRM constructs do not require any laboratory-synthesized components such as the modified PAMmer oligonucleotides59 used by the Cas9-directed m6A editor system39, and thus can be genetically encoded in their entirety. TRM is therefore compatible with delivery strategies including viral transduction that cannot easily deliver cargo that contains a synthetic component. Finally, in contrast to M3M14–dCas9, which only functions in the cytoplasm39, the nucleus-localized dCas13–M3nls developed in this work enables 5’ UTR targeting and the ability to affect m6A-dependent nuclear processing events, such as alternative splicing58, microRNA maturation34,60, nuclear export7, and chromatin accessibility5.

In light of these strengths, we anticipate that the TRM editors developed in this study will illuminate functional relationships between m6A and phenotype, and advance basic research on m6A biology. While additional work lies ahead to further optimize TRM efficiency and specificity, and to explore the expansion of this approach to include other RNA modifications, this study represents a key step towards the development of a precision tool kit to enable site-specific control of the epitranscriptome in cell culture and in living organisms.

Methods

General methods and molecular cloning.

TRM construct and reporter plasmids used in this study were assembled using Uracil-Specific Excision Reagent (USER) cloning. Briefly, deoxyuracil-containing primers (Integrated DNA Technologies or Eton Biosciences) were used to amplify DNA fragments with Phusion U Green Multiplex PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher), using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel containing 0.01% ethidium bromide (v/v) and imaged with a G:Box gel imager (Syngene) to confirm their identity. DNA fragments with deoxyuracil incorporated near the 5’ ends were then assembled using USER Enzyme, CutSmart Buffer, and DpnI restriction enzyme (New England BioLabs) per manufacturer’s protocol. To clone guide RNA plasmids, oligos encoding spacer sequences (Integrated DNA Technologies or Eton Biosciences) were annealed and golden-gate cloned into PspCas13b guide RNA cassettes. One Shot Mach1 Chemically Competent E. coli cells (Thermo Fisher) were transformed with assembled plasmids and grown overnight on LB agar plates with the proper maintenance antibiotic. Colonies containing correct plasmids were grown overnight in 2xYT medium with maintenance antibiotic, and plasmids were purified with either Spin Miniprep Kits (Qiagen) or Plasmid Plus Midi Kits (for mammalian cell transfections, Qiagen) with endotoxin removal. DNA concentration and purity were determined using a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher).

Plasmid construct design.

TRM editors were constructed by fusing candidate methyltransferases to the C-terminus of PspCas13b Δ984-1090 H133A (dCas13) via an XTEN linker (SGSETPGTSESATPES) for M3 editors or an (SGGS)2-XTEN-(SGGS)2 linker for M3M14 editors. M3 editors used the METTL3273-580 methyltransferase domain, and M3M14 editors used METTL3359-580 tethered to METTL14111-456 by a flexible (GGS)10 linker. Nucleus-localized TRM constructs introduced an HIV nuclear localization signal (LQLPPLERLTL) at the C-terminus of dCas13, whereas cytoplasm-localized constructs incorporated SV40 bipartite nuclear export signals (KRTADGSEFESPKKKRK) at both dCas13 termini. dCas13 was amplified from pC0054-CMV-dPspCas13b-longlinker-ADAR2DD(E488Q/T375G), a gift from Feng Zhang (Addgene plasmid #103870), for subcloning into the ABE61 plasmid backbone with constitutive expression under a CMV promoter. M3M14-dCas9 plasmids were constructed by fusing METTL3369-580-(GGS)6-METTL14116-402 to Cas9 D10A/H840A within the pCMV-BE2 vector backbone via an XTEN linker. METTL3 and METTL14 domains in TRM editors and M3M14-dCas9 were commercially synthesized (Genscript) with the same mammalian codon optimization. Methyltransferase-inactive TRM editors and M3M14-dCas9 constructs were generated by installing a METTL3 D395A mutation. Cas13 guide RNAs were Golden-gate cloned into pC0043-PspCas13b-crRNA, a gift from Feng Zhang (Addgene plasmid #103854), which has constitutive guide RNA expression under a U6 promoter. Cas9 guide RNAs were Golden-gate cloned into a vector bearing the S. pyogenes Cas9 crRNA backbone under constitutive expression by a U6 promoter.

Methyltransferase kinetics.

METTL3 and METTL3/14 complex was obtained from Active Motif (catalog #31567, 31570). The methyltransferase activity of METTL3 and METTL3-14 complex was measured using a radioactivity-based assay43. Radio-labeled S-adenosyl-L-methionine (3H-SAM) and biotinylated unmethylated N6-adenine single stranded RNA (ssRNA) were used as substrates (Supplementary Table 1). All assays were performed using 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 0.01 %NP-40, 10U of RNaseOUT (Life Technologies) buffer. For determination of kinetic parameters, protein concentrations and reaction time were optimized to obtain linear initial velocities. To determine the Kmapp values for ssRNA, a saturating concentration of SAM was used (1 μM) and ssRNA substrate was titrated into the assay mixture containing the enzyme and aliquots of the reaction was stopped at various time points by heating to 90 °C for 5 min. After reaction, the biotinylated ssRNA was captured in a FlashPlate (PerkinElmer) coated with streptavidin. The amount of methylated m6A ssRNA was quantified by scintillation counting (count per minute, cpm) on a TopCount microplate reader (PerkinElmer). The Km and Vmax values were calculated using Prism software.

Bacterial RNA purification and m6A immunoprecipitation.

Chemically competent E. coli Tuner (DE3) cells were purchased from Millipore-Sigma. E. coli Tuner cells were cultured at 37 °C in LB media with shaking at 200 rpm overnight. Bacterial E. coli Tuner culture was pelleted by centrifuge at 6000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. To lyse, each bacterial pellet was resuspended in preheated Max bacterial enhancement reagent (Thermo Fisher), heated at 95 °C for 5 min, and cooled on ice for 2 min. RNA was then extracted via TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher) and further purified with RNeasy Spin columns (Qiagen) including an on-column DNAaseI treatment to remove residual DNA. Ribosomal RNA was removed using RiboZero (Illumina). Ribo-depleted RNA was fragmented to 200-300 by addition of 50 mM MgCl2 and incubated at 85 °C for 4 min.

m6A immunoprecipitation (MeRIP) is based on the previously described m6A-seq protocol62 with several modifications: 30 μL of protein G magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher) were washed twice by IP buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% NP-40 in nuclease-free H2O), resuspended in 500 μL of IP buffer, and tumbled with 5 μg anti-m6A antibody (New England BioLabs) at 4 °C overnight. Following 2 washes in IP buffer, the antibody-bead mixture was resuspended in 500 μL of the IP reaction mixture containing 10ug of fragmented total RNA, 100 μL of IP buffer, and 5 μL of RNasin Plus RNase Inhibitor (Promega) and incubated at least 4 h at 4 °C. After incubation the low/high salt-washing method was applied: briefly the RNA reaction mixture was washed twice in 1,000 μL of IP buffer, twice in 1,000 μL of low-salt IP buffer (50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% NP-40 in nuclease-free H2O), and twice in 1,000 μL of high-salt IP buffer (500 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% NP-40 in nuclease-free H2O) for 10 min each at 4 °C. After washing, the m6A-enriched fragmented RNA was eluted from the beads in 200 μL of RLT buffer supplied in RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) for 5 min at room temperature. The mixture was transferred to an RNA Clean & Concentrator-5 spin column (Zymo Research) and further purified via manufacturer’s instructions.

Bacterial RT-qPCR.

RNA was isolated and converted to cDNA using a 1-step RNA-to-Ct (Thermo Fisher) kit according to manufacturer’s protocol. RT-qPCR was performed and quantified on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). All reactions were run in technical triplicate. Target Ct values where normalized to the geometric mean of internal controls, including an internal housekeeping gene and RNA spike-in controls to account for variability in RNA amounts. Resulting normalized values were compared to target Ct values in cells containing only the synthetic target vector using the 2−ΔΔCt method63.

Fluorometric targeted RNA methylation assay.

Total RNA from E. coli Tuner (DE3) cells was purified as described above and adjusted to a volume of 200 μL. Total RNA was denatured at 75 °C for 5 min and incubated at 42 °C for 10 min with 1 μg of dual biotin labeled DNA probe complimentary to a unique 30 base region within the synthetic target. Probe annealed target RNA was bound to 100 μL of μMACS Streptavidin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) and incubated at 4 °C for 15 min. Magnetic separation was done with a μColumn (Miltenyi Biotec). RNA:probe was passed over the μColumn and washed twice with 150 uL TE buffer. Probe bound RNA was eluted by adding 150 μL of H2O warmed to 90 °C. Eluted RNA was purified and concentrated using a MiniElute column (Zymo Research). Resulting RNA concentration was determined using a Qubit RNA HS assay kit (Thermo Fisher). RNA was serial diluted and m6A was quantified with the EpiQuik m6A RNA methylation quantification kit (Epigentek) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Flourometric m6A signal was measured on an Infinite Pro M1000 plate reader (Tecan) at 530EX/590EM nm.

Bacterial MeRIP-seq.

Ribosomal RNA was removed using RiboZero (Illumina). Ribo-depleted RNA was fragmented to 200-300 by addition of 50 mM MgCl2 and incubated at 85 °C for 4 min. RNA libraries were constructed using SMARTer PrepX Apollo NGS library prep system (Takara) following manufacturer’s protocol. Libraries were normalized and ran on a NextSeq 550 sequencer (Illumina) using single-read 75 cycle kit. Resulting reads were aligned to the bacterial K12 transcriptome using HISAT2 (John Hopkins University) with reference annotation Escherichia coli strain K12 NCBI (2001). Peak calling was performed using Fisher’s exact test as employed in the (m6Amonster) package considering only bins with 30 or more counts, a peak cutoff false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.05, and a peak cutoff ratio of 1. Peaks consistent between at least two replicates were kept in the final peak list.

Mammalian cell culture conditions.

All experiments involving mammalian cells were performed in HEK293T cell lines (American Type Culture Collection (ATCC)). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium plus GlutaMAX (DMEM, Thermo Fisher) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS). HEK293T cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and maintained at confluency below 80%. Different cell passages were used for each biological replicate.

HEK293T transfection.

Unless otherwise noted, HEK293T cells were seeded on 24-well poly-D-lysine plates (Corning) at approximately 120,000 cells per well in culture medium. At 80% confluency approximately 16 h after plating, cells were transfected with 1400 ng TRM editor plasmid and 600 ng Cas13 guide RNA plasmid using 2.5 μl Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher) in Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Media (Thermo Fisher). A full list of Cas13 guide RNAs used in this work is given in Supplementary Table 2. For M3M14-dCas9 experiments, cells were transfected in the same manner with M3M14-dCas9 and single guide RNA plasmids at a mass ratio of 5:3. Immediately following, PAMmer oligonucleotides (Integrated DNA Technologies) were transfected using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Cas9 single guide RNAs and PAMmers used in this work are shown in Supplementary Table 3. Unless otherwise noted, cells were cultured for 48 h post-transfection before total RNA extraction.

Mammalian RNA isolation and purification.

HEK293T cells were washed with PBS, then lysed with TRIzol (Thermo Fisher) and cleaned using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) or Direct-zol RNA Miniprep (Zymo Research) kits with DNaseI treatment following manufacturer’s protocol. Prior to poly(A) enrichment, total RNA was supplemented with 40 nM DNA oligos (Integrated DNA Technologies, Supplementary Table 4) that hybridize to the guide RNA transfected within HEK293T cells and heated at 72 °C for 3 min. Guide-quenching oligos contained a 2’,3’-dideoxycytidine modification at the 3’ end to prevent primer extension in downstream reverse transcription reactions. mRNA was separated from quenched total RNA with Dynabeads Oligo(dT)25 (Thermo Fisher) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Mammalian m6A immunoprecipitation and RT-qPCR.

Poly(A) enriched RNA was fragmented in solution of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM MgCl2 and heated at 95 °C for exactly 8 min. m6A-modified and unmodified control RNAs (New England BioLabs) were dosed into fragmented RNA, and a portion was saved as input RNA. Remaining fragmented RNA was subjected to m6A immunoprecipitation based on the previously described m6A-seq protocol62 with several modifications: 30 μL of protein G magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher) were washed twice by IP reaction buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% NP-40 in nuclease-free H2O), resuspended in 500 μL of reaction buffer, and tumbled with 5 μg anti-m6A antibody (New England BioLabs) at 4 °C overnight. Following 2 washes in reaction buffer, the antibody–bead mixture was resuspended in 500 μL of the reaction mixture containing 10 μg of fragmented total RNA, 100 μL of reaction buffer, and 5 μL of RNasin Plus RNase Inhibitor (Promega) and incubated at least 4 h at 4 °C. To remove unbound RNA, samples were washed 5 × with each of the following buffers: reaction buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% NP-40 in nuclease-free H2O), low-salt reaction buffer (50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% NP-40 in nuclease-free H2O), and high salt reaction buffer (500 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% NP-40 in nuclease-free H2O). RNA was eluted in RLT buffer (Qiagen) and purified with RNA Clean & Concentrator-5 kits (Zymo Research).

Purified RNA was reverse-transcribed with High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA (Thermo Fisher) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Resulting cDNA was pre-amplified with SsoAdvanced PreAmp Supermix (Bio-Rad) using qPCR forward and reverse primers (Supplementary Table 5) according to manufacturer’s protocol. qPCR was performed with IQ Multiplex Powermix (Bio-Rad) using TaqMan probes (Bio-Rad) specific for the targeted m6A site and reference controls (Supplementary Table 5). All reactions were performed and quantified on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) in technical triplicate. For m6A target sites with multiple probes, the geometric mean was taken for the resulting Ct qPCR values. To account for variability in RNA amounts, target Ct values where normalized to the geometric mean of the following internal controls: a methylated EEF1A1 control transcript, m6A-modified RNA spike-in controls (New England BioLabs), and a non-targeted region on the TRM-targeted transcript. Resulting normalized values were compared to target Ct values from a pUC19-only transfection control using the 2−ΔΔCt method63.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

A 3× hemagglutinin (3×HA) epitope tag (YPYDVPDYAYPYDVPDYAYPYDVPDYA) was cloned onto the C-terminus of TRM editor constructs. HEK293T cells were grown on poly-D-lysine/laminin 12 mm coverslips (Corning) placed on 24-well plates. At 60% confluency, each coverslip was transfected with 125 ng 3×HA-tagged editor plasmid and 375 ng guide RNA plasmid, using 1 μL Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo) according to manufacturer’s protocol. After 48 h of incubation, culture media was aspirated, and coverslips were washed once with PBS. Cells were fixed by incubating in 4% PFA (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 30 min. Cells were then washed with PBS 3 × and permeabilized with PBS + 0.1% Triton (PBST) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were stained with a mouse anti-HA primary antibody (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology 2367) in blocking buffer (3% BSA in PBST) for 12 h at 4 °C. Cells were then washed 5 × with PBST and stained with a goat anti-mouse IgG, AF488 secondary antibody (1:800, Thermo Fisher A-11029) in blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Cover slips were finally washed 3 × with PBST and mounted onto microscope slides (VWR) with ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Invitrogen). Images were acquired using an Axioplan 2 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss) and analyzed with MetaMorph version 7.8 and ImageJ version 2.0.0-rc-69/1.52i.

Measurement of luciferase RNA and protein expression.

To generate luciferase reporter constructs, Cypridina luciferase (Cluc) driven by a CMV promoter and Gaussia luciferase (Gluc) driven by an EF1-α promoter were cloned onto the same vector. 5’ UTR and 3’ UTR sequences for Cluc reporters were synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies) and cloned onto Cluc. Both luciferases were expressed from the same vector, allowing Gluc to serve as a dosing control for Cluc targeting.

For luciferase experiments, HEK293T cells were plated at 20,000 cells per well in 96-well culture plates (VWR). Each well was transfected at 75% confluency 16 h later with 250 ng TRM editor plasmid, 150 ng Cas13 guide RNA plasmid, and 12.5 ng dual-luciferase reporter vector using 0.5 μL Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were cultured for 48 h post-transfection before media containing secreted luciferase was removed. Luciferase activity was measured from 20 μl of harvested media diluted 1:5 in PBS using Pierce Cypridina and Pierce Gaussia Luciferase Flash Assay kits (Thermo Fisher). All luciferase activity measurements were performed as biological replicates on a Biotek Synergy 4 plate reader with an injection protocol.

To measure luciferase transcript abundance, RNA was isolated and converted to cDNA using a 2-step Cells-to-Ct (Thermo Fisher) kit with 10 min (2× longer than suggested) DNaseI treatment to ensure degradation of plasmid DNA. All other steps were carried out according to manufacturer’s protocol. qPCR was performed on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) with technical and biological triplicates using TaqMan probes (Bio-Rad) for Cluc and Gluc transcripts. Samples for luciferase activity measurement and luciferase RNA quantification were taken from the same cells. For both RNA and protein measurement, Cluc signal was normalized by Gluc dosing control.

Western blotting.

HEK293T cells in 6-well plates were transfected with 2.8 μg 3×HA-tagged TRM editor and 1.2 μg non-targeting guide RNA. After 48 h, cells were washed with PBS and lysed in 200 μl RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher) with PMSF and cOmplete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche). Lysate was denatured at 95 °C, 1 μl per sample was loaded into a 10-well NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris gel (Thermo Fisher), and gel was dry-transferred to a 0.2 μm PVDF (polyvinylidene difluoride) membrane (Thermo Fisher) using an iBlot 2 Dry Blotting System (Thermo Fisher) for 7 min at 20 V. Membranes were stained with mouse anti-HA (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology 2367) and rabbit anti-Histone H3 (1:2500, Abcam ab1791) in Odyssey Blocking Buffer in TBS (LI-COR) overnight at 4 °C. After washing 3× with TBST (TBS + 0.5% Tween-20), membranes were incubated with IRDye-labeled secondary antibodies goat anti-mouse 680RD (LI-COR 926-68070) and donkey anti-rabbit 800CW (LI-COR 926-32213) diluted 1:5000 in Odyssey Blocking Buffer for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was finally washed 3× with TBST, then imaged on an Odyssey Imaging System (LI-COR).

MazF single nucleotide m6A modification detection.

10 technical replicates of 3 biological replicates of polyA+ RNA were plated in a 384 well PCR plate (Applied Biosystems) using a Mantis microfluidic dispensing system (FORMULATRIX), facilitating precise dispensing at small volumes. RNA was prepared by mixing 15 ng of polyA-enriched RNA in two conditions: One containing 10 units of MazF enzyme (Takara), MazF buffer (40mM Na2P04 pH 7.5, 0.05% Tween 20), and 1 U of RNaseOUT; and the other containing MazF buffer and RNaseOUT only. Cleavage and control reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and then heat denatured for 4 min to stop the cleavage reaction. MazF treated and control samples where reverse transcribed using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA (Thermo Fisher) kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol at 1/4 volume added using Mantis microfluidic dispensing system. Differential MazF cleavage of the target RNA transcript was quantified by qPCR with IQ Multiplex Powermix (Bio-Rad) using two TaqMan probes (Bio-Rad) one targeting the cleavage site the other targeting an uncleaved section of the target transcript. All reactions were performed and quantified on a CFX384 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad).

MeRIP-sequencing.

Total RNA from 4 biological replicates of each condition was poly(A)-enriched using Dynabeads Oligo(dT)25 (Thermo Fisher) and fragmented to a mean size of 200-300 nucleotides by incubation in 50 mM MgCl2 for 8 min at 95 °C. A portion of fragmented RNA was saved as input. Remaining RNA samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C rotating with protein G magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher) coated with EpiMark anti-m6A antibody (New England BioLabs). Washes and elution were performed on a Biomek liquid handler (Beckman Coulter). To remove unbound RNA, samples were washed five times with each of the following buffers: reaction buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% NP-40 in nuclease-free H2O), low-salt reaction buffer (50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% NP-40 in nuclease-free H2O), and high salt reaction buffer (500 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% NP-40 in nuclease-free H2O). RNA was eluted with RLT buffer (Qiagen) and purified with MyOne Silane Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher). RNA libraries for the RNA input, collected supernatant, and IP were constructed using SMARTer PrepX Apollo NGS library prep system (Takara) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The size distributions of the resulting libraries were assessed using the Tapestation D1000 screen tape (Agilent Technologies), normalized, and sequenced on a NextSeq 550 (Illumina) using a single read 75 cycle kit.

MeRIP sequencing analysis.

MeRIP-seq reads were trimmed for quality using the TrimGalore version 0.6.2 aligned to the human transcriptome using HISAT2 (Johns Hopkins University) with reference annotation UCSC hg38. For transcriptome-based methylation detection, the R package MeTDiff was used to detect differential m6A methylation64. m6A peak calling and differential methylation of the transcriptome was evaluated using five input and IP replicates for each condition with peak cutoff and peak differential cutoffs set to 0.05 and reads with a mapping quality < 20 filtered out. MeTDiff calculates P values using a logs likelihood-ratio test with Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate correction. We created a consensus list of peaks by including peaks that were consistent between three samples. Peaks consistent between at least 3 replicates where kept in the final consensus peak list. The top 4,000 peaks where selected for de novo motif discovery and performed using HOMERv4.10.65 The Guitar R package was used to plot mRNA and lnRNA density coverage.

Quantification of mRNA m6A content.

mRNA was purified from HEK293T cells co-transfected with TRM editors and non-targeting guide RNAs. RNA concentration was quantified with Qubit RNA HS Assay (Thermo Fisher) and normalized to 18.75 ng/μL. To measure % m6A, 150 ng (8 μL) of diluted mRNA was used for the EpiQuik m6A RNA methylation quantification kit (Epigentek) according to manufacturer’s protocol. A standard curve and both negative and positive controls were used. Colorimetric m6A signal was measured at 450 nm on an Infinite Pro M1000 plate reader (Tecan) and sample absorbance was subtracted from negative control background absorbance for analysis.

RNA-sequencing.

HEK293T cells were transfected with TRM editors combined with non-targeting guide RNAs and total RNA was harvested after 48 h. Total RNA was polyA enriched as described above. Sequencing libraries were prepared using polyA-enriched RNA on a SMARTer PrepX Apollo NGS library prep system (Takara) following manufacturer’s protocols. Libraries were normalized with a Qubit dsDNA HS Assay (Thermo Fisher) and sequenced on a NextSeq 550 (Illumina) using high output v2 kits (Illumina) with 75 cycles. Reads were aligned to a custom hg38 transcriptome containing dCas13 with reference UCSC hg38. Fastq files were filtered with TrimGalore version 0.6.2 (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore) to remove low-quality bases, unpaired sequences, and adaptor sequences. Trimmed reads were aligned to a Homo sapiens genome assembly GRCh38 with a custom Cas13 gene entry by aligning reads with STAR version 2.7.0d (1st pass) followed by a second STAR alignment using generated splice sites from the 1st pass to create a 2-pass STAR Alignment. RSEM version 1.3.1 was used to quantify transcript abundance. The limma-voom package66,67 was used to normalize gene expression levels and perform differential expression analysis with batch effect correction.

Measurement of alternative splicing.

HEK293T cells were plated at 20,000 cells per well in 96-well culture plates (VWR). Each well was transfected at 75% confluency with 250 ng TRM editor plasmid and 150 ng Cas13 guide RNA plasmid using 0.5 μL Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. As a vector control, 400 ng of pUC19 plasmid was also transfected. After 48 h post-transfection, RNA was isolated and converted to cDNA using a 2-step Cells-to-Ct (Thermo Fisher) kit with 10 min (2× longer than suggested) DNaseI treatment to ensure degradation of genomic DNA. All other steps were carried out according to manufacturer’s protocol. Semi-quantitative PCR was performed in 20 μL reactions with Q5 Hot-Start High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England BioLabs), 1 μL of cDNA, and 0.5 μM of each forward and reverse primer (Integrated DNA Technologies, Supplementary Table 6). All PCR reactions were performed for 35 cycles. Amplified cDNA was diluted 1:20 in nuclease-free H2O then run on a Tapestation D1000 or D5000 screen tape (Agilent Technologies). Size abundances of each splicing isoform were integrated to quantify exon exclusion and inclusion.

Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data Availability.

Key plasmids from this work are available from Addgene (depositor: David R. Liu) and other plasmids are available upon request. All unmodified reads for sequencing-based data in the manuscript are available on the NCBI Sequence Read Archive, accession number PRJNA559201. Amino acid sequences of TRM editors reported in this study are provided in the Supplementary Sequences.

Code Availability.

All scripts used in this study are available at https://github.com/CwilsonBroad/

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Harvard Bauer Core facility staff for assistance with automatic liquid handling and NGS library preparation; J. Nelson, A. Anzalone, and R. Chen for helpful discussions; the Pattern team at the Broad Institute for data visualization assistance; and A. Hamidi for assistance editing the manuscript. This work was supported by the Ono Pharma Foundation, U.S. NIH RM1 HG009490, U01 AI142756, and R35 GM118062, and HHMI. C.W. is the Marion Abbe Fellow of the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (DRG-2343-18). P.J.C. is supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

D.R.L. is a consultant and co-founder of Beam Therapeutics, Prime Medicine, Editas Medicine, and Pairwise Plants, companies that use genome editing. D.R.L., P.J.C., and C.W. have filed patent applications on aspects of this work.

References

- 1.Goldberg AD, Allis CD & Bernstein E Epigenetics: a landscape takes shape. Cell 128, 635–638, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.006 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoernes TP & Erlacher MD Translating the epitranscriptome. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 8, doi: 10.1002/wrna.1375 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao BS, Roundtree IA & He C Post-transcriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18, 31–42, doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.132 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer KD & Jaffrey SR The dynamic epitranscriptome: N6-methyladenosine and gene expression control. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 15, 313–326, doi: 10.1038/nrm3785 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu J et al. N(6)-methyladenosine of chromosome-associated regulatory RNA regulates chromatin state and transcription. Science, eaay6018, doi: 10.1126/science.aay6018 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao W et al. Nuclear m(6)A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Molecular cell 61, 507–519, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.012 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roundtree IA et al. YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N(6)-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. Elife 6, doi: 10.7554/eLife.31311 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi H et al. YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N(6)-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res 27, 315–328, doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 505, 117–120, doi: 10.1038/nature12730 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X et al. N(6)-methyladenosine Modulates Messenger RNA Translation Efficiency. Cell 161, 1388–1399, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dominissini D et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 485, 201–206, doi: 10.1038/nature11112 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer Kate D. et al. Comprehensive Analysis of mRNA Methylation Reveals Enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near Stop Codons. Cell 149, 1635–1646, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batista PJ et al. m(6)A RNA modification controls cell fate transition in mammalian embryonic stem cells. Cell stem cell 15, 707–719, doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.019 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou J et al. Dynamic m(6)A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature 526, 591–594, doi: 10.1038/nature15377 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu K et al. Mettl3-mediated m(6)A regulates spermatogonial differentiation and meiosis initiation. Cell Res 27, 1100–1114, doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.100 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao BS et al. m(6)A-dependent maternal mRNA clearance facilitates zebrafish maternal-to-zygotic transition. Nature 542, 475–478, doi: 10.1038/nature21355 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patil DP et al. m(6)A RNA methylation promotes XIST-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature 537, 369–373, doi: 10.1038/nature19342 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiang Y et al. RNA m6A methylation regulates the ultraviolet-induced DNA damage response. Nature 543, 573–576, doi: 10.1038/nature21671 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhong X et al. Circadian Clock Regulation of Hepatic Lipid Metabolism by Modulation of m(6)A mRNA Methylation. Cell reports 25, 1816–1828 e1814, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.068 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaffrey SR & Kharas MG Emerging links between m(6)A and misregulated mRNA methylation in cancer. Genome medicine 9, 2, doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0395-8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Z et al. METTL3-mediated N(6)-methyladenosine mRNA modification enhances long-term memory consolidation. Cell Res 28, 1050–1061, doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0092-9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han D et al. Anti-tumour immunity controlled through mRNA m(6)A methylation and YTHDF1 in dendritic cells. Nature 566, 270–274, doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0916-x (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engel M & Chen A The emerging role of mRNA methylation in normal and pathological behavior. Genes Brain Behav, doi: 10.1111/gbb.12428 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaffrey SR & Kharas MG Emerging links between m6A and misregulated mRNA methylation in cancer. Genome medicine 9, 2, doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0395-8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cui Q et al. m6A RNA Methylation Regulates the Self-Renewal and Tumorigenesis of Glioblastoma Stem Cells. Cell reports 18, 2622–2634, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.059 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol 10, 93–95, doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1432 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sledz P & Jinek M Structural insights into the molecular mechanism of the m(6)A writer complex. Elife 5, doi: 10.7554/eLife.18434 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X et al. Structural basis of N(6)-adenosine methylation by the METTL3-METTL14 complex. Nature 534, 575–578, doi: 10.1038/nature18298 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang P, Doxtader KA & Nam Y Structural Basis for Cooperative Function of Mettl3 and Mettl14 Methyltransferases. Mol Cell 63, 306–317, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.041 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scholler E et al. Interactions, localization, and phosphorylation of the m(6)A generating METTL3-METTL14-WTAP complex. RNA 24, 499–512, doi: 10.1261/rna.064063.117 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng G et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell 49, 18–29, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jia G et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol 7, 885–887, doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X & He C Reading RNA methylation codes through methyl-specific binding proteins. RNA Biol 11, 669–672, doi: 10.4161/rna.28829 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alarcon CR et al. HNRNPA2B1 Is a Mediator of m(6)A-Dependent Nuclear RNA Processing Events. Cell 162, 1299–1308, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.011 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu N et al. N(6)-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature 518, 560–564, doi: 10.1038/nature14234 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi H, Wei J & He C Where, When, and How: Context-Dependent Functions of RNA Methylation Writers, Readers, and Erasers. Molecular cell 74, 640–650, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.04.025 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Y, Hsu PJ, Chen YS & Yang YG Dynamic transcriptomic m(6)A decoration: writers, erasers, readers and functions in RNA metabolism. Cell Res 28, 616–624, doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0040-8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyer KD & Jaffrey SR Rethinking m(6)A Readers, Writers, and Erasers. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 33, 319–342, doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060758 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu X-M, Zhou J, Mao Y, Ji Q & Qian S-B Programmable RNA N6-methyladenosine editing by CRISPR-Cas9 conjugates. Nature Chemical Biology, doi: 10.1038/s41589-019-0327-1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abudayyeh OO et al. RNA targeting with CRISPR-Cas13. Nature 550, 280–284, doi: 10.1038/nature24049 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.East-Seletsky A et al. Two distinct RNase activities of CRISPR-C2c2 enable guide-RNA processing and RNA detection. Nature 538, 270–273, doi: 10.1038/nature19802 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abudayyeh OO et al. C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector. Science 353, aaf5573, doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5573 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li F et al. A Radioactivity-Based Assay for Screening Human m6A-RNA Methyltransferase, METTL3-METTL14 Complex, and Demethylase ALKBH5. Journal of biomolecular screening 21, 290–297, doi: 10.1177/1087057115623264 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cox DBT et al. RNA editing with CRISPR-Cas13. Science, doi: 10.1126/science.aaq0180 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abudayyeh OO et al. A cytosine deaminase for programmable single-base RNA editing. Science 365, 382, doi: 10.1126/science.aax7063 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slaymaker IM et al. High-Resolution Structure of Cas13b and Biochemical Characterization of RNA Targeting and Cleavage. Cell Reports 26, 3741–3751.e3745, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.02.094 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schellenberger V et al. A recombinant polypeptide extends the in vivo half-life of peptides and proteins in a tunable manner. Nat Biotechnol 27, 1186–1190, doi: 10.1038/nbt.1588 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meyer KD et al. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3’ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell 149, 1635–1646, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nelles DA et al. Programmable RNA Tracking in Live Cells with CRISPR/Cas9. Cell 165, 488–496, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.054 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu N et al. Probing N6-methyladenosine RNA modification status at single nucleotide resolution in mRNA and long noncoding RNA. RNA 19, 1848–1856, doi: 10.1261/rna.041178.113 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cui Q et al. m(6)A RNA Methylation Regulates the Self-Renewal and Tumorigenesis of Glioblastoma Stem Cells. Cell Rep 18, 2622–2634, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.059 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang S et al. m(6)A Demethylase ALKBH5 Maintains Tumorigenicity of Glioblastoma Stem-like Cells by Sustaining FOXM1 Expression and Cell Proliferation Program. Cancer Cell 31, 591–606 e596, doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.02.013 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Geula S et al. m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naive pluripotency toward differentiation. Science 347, 1002–1006, doi: 10.1126/science.1261417 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia-Campos MA et al. Deciphering the “m(6)A Code” via Antibody-Independent Quantitative Profiling. Cell 178, 731–747.e716, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.06.013 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Z et al. Single-base mapping of m6A by an antibody-independent method. Science Advances 5, eaax0250, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax0250 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Imanishi M, Tsuji S, Suda A & Futaki S Detection of N6-methyladenosine based on the methyl-sensitivity of MazF RNA endonuclease. Chemical Communications 53, 12930–12933, doi: 10.1039/C7CC07699A (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bartosovic M et al. N6-methyladenosine demethylase FTO targets pre-mRNAs and regulates alternative splicing and 3′-end processing. Nucleic Acids Research 45, 11356–11370, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx778 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xiao W et al. Nuclear m6A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Molecular Cell 61, 507–519, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.012 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Connell MR et al. Programmable RNA recognition and cleavage by CRISPR/Cas9. Nature 516, 263–266, doi: 10.1038/nature13769 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]