Abstract

Background

In the 8th edition of the melanoma staging system, stage III was divided into stages IIIA-IIID. Previous studies have found that the long-term survival rate of females is much higher than that of males. This study was designed to explore whether this sex-specific advantage still exists in the new staging subgroups.

Methods

We obtained data from individuals diagnosed with skin melanoma between 2004 and 2015 from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. A total of 8,726 patients with stage III disease were enrolled in the study (5,370 males and 3,356 females). Among these patients, 505 had stage IIID disease (370 males and 135 females).

Results

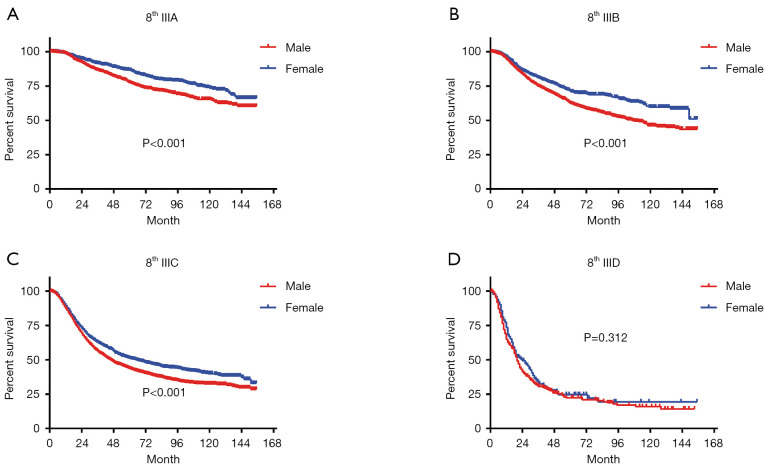

In the 7th edition of the staging system, there were significant sex-specific differences in overall survival (OS) and melanoma-specific survival (MSS) in each subgroup of stage III. In stages IIIA–IIIC in the 8th edition, there were also significant differences between males and females (P<0.001), but in stage IIID patients, there were no significant differences in either OS (P=0.312) or MSS (P=0.288). Cox analysis confirmed that stage IIID does not affect prognosis in males. Further research found no difference between males and females with stage IIID disease in any age subgroup.

Conclusions

We compared sex-specific survival differences in patients with stage III disease according to the 8th edition of the staging system. Females with stage IIIA–IIIC disease have better survival rates than males. However, among patients with stage IIID disease, there is no significant difference in survival between males and females.

Keywords: Melanoma; skin melanoma; Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER); TNM staging system; sex-specific

Introduction

Melanoma is the deadliest skin tumor. In developed countries, the incidence of skin melanoma is 9.3 per 100,000 people (1), and it accounts for 80% of deaths caused by skin tumors. Skin melanoma accounts for 1–2% of all cancer-related deaths. In recent years, skin melanoma has increased in incidence, with higher long-term survival rates (2,3).

The etiology of skin melanoma is not yet clear. Several factors, such as genetics and environmental exposure (e.g., ultraviolet (UV) rays, smoking, drug use, and drinking), probably affect the incidence of skin melanoma. Females have a clear advantage over males in terms of melanoma-specific survival (MSS). Several studies have verified the advantages of female sex in many countries and different populations; these advantages have included a low melanoma incidence and high long-term survival rates. Furthermore, these advantages of female sex have increased gradually in recent years and have been verified in all pathological stages of melanoma (4-7). However, there is no clear theoretical foundation that could account for this phenomenon.

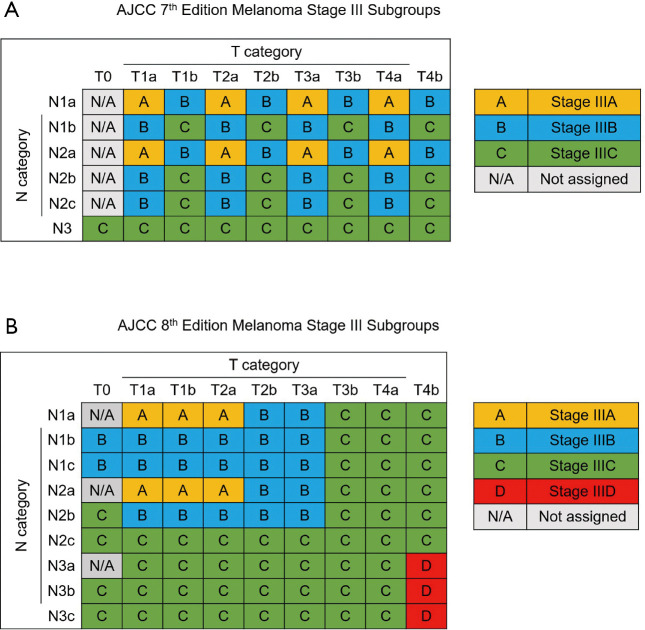

The 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for skin melanoma was published in 2017. The staging system for melanoma was adjusted by reducing the importance of the mitotic rate in the T category and adjusting the N category to include more details (8,9). Stage III was divided into 4 subgroups, with a new IIID subgroup, and the IIIA, IIIB and IIIC subgroups were adjusted (Figure 1). In past studies, the long-term survival rate in females was verified to be higher than that in males (10). However, no studies have investigated sex-specific survival based on the 8th edition of the staging system, especially in patients with stage III disease. Therefore, we selected skin melanoma patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database in the United States. The aim of our study was to evaluate sex-specific survival in patients with stage III disease based on the 8th edition of the staging system. The guidelines in the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement were followed in this study (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3332).

Figure 1.

AJCC stage III subgroups based on T and N categories (A) 7th edition (9). (B) 8th edition (8). N/A, not assigned. AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Methods

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments revised in 2013 or comparable ethical standards.

Patients were selected from the SEER database. The current SEER database is a population-based cancer registry sponsored by the National Cancer Institute of the United States. We selected individuals diagnosed with skin melanoma between 2004 and 2015. Based on the 7th and 8th editions of the melanoma staging system, patients diagnosed with pathological T0-T4b, N1a-N3c and M0 disease were enrolled. Other enrollment criteria included skin melanoma as the first malignant tumor, active follow-up, and positive histology. Patients were excluded if diagnosed during autopsy or if the cause of death was unknown.

Baseline data, including patient information (age, sex), and melanoma characteristics (location, subtype, Clark class, Breslow thickness, mitotic rate, and ulceration) were obtained from the SEER database. In this study, overall survival (OS) and melanoma-specific survival (MSS), which were collected from the SEER database through December 31, 2015, were used to evaluate the outcomes. OS and MSS were defined as the intervals from diagnosis until death from any cause or death as a result of melanoma, respectively.

Statistical analysis

We used one-way ANOVA with a multiple comparison post hoc test and a chi-square test to analyze all continuous and categorical variables with normal distributions. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to analyze data with nonnormal distributions after adjusting for multiple comparisons. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were estimated and compared with the log-rank test. Cox regression analysis was used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Risk factors with a P value <0.1 in the univariate analysis and with substantial clinical value were selected for the multivariate analysis. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS 24.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) were used for the analyses.

Results

A total of 8,726 stage III patients (5,370 males and 3,356 females) were enrolled in this study. According to the 8th edition of the staging system, 505 patients were classified as having stage IIID disease (370 males and 135 females). Baseline data are shown in Table 1. Among all stage III patients, the males were older (57.0±15.7 vs. 53.9±18.0 years, P<0.001) and had a worse Breslow thickness (316.3±241.2 vs. 290.5±231.5 mm, P<0.001). The trunk (42.2%) was the most frequent location of skin melanoma in males, while the lower limb and hip (38.3%) were most frequent in women. There were more Caucasians among the males with stage III (96.9% vs. 96.1%, P=0.045) and stage IIID (94.6% vs. 89.7%, P=0.049) disease (Table S1). The rate of ulceration was higher in males than in females (45.3% vs. 39.4%, P<0.001), and males had a lower mitotic rate (P=0.021). There was no difference between males and females with regard to the subtype of melanoma and Clark class.

Table 1. Baseline data of patients.

| All stage III patients (n=8,726) | Stage IIID patients (n=505) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n=5,370) | Female (n=3,356) | P value | Male (n=370) | Female (n=135) | P value | ||

| Age, years (%) | 57.0±15.7 | 53.9±18.0 | <0.001 | 59.1±15.5 | 61.2±18.1 | 0.121 | |

| <35 | 487 (9.1) | 523 (15.6) | <0.001 | 30 (8.1) | 11 (8.1) | 0.090 | |

| 35–54 | 1,705 (31.8) | 1,186 (35.3) | 100 (27.0) | 35 (25.9) | |||

| 55–74 | 2,490 (46.4) | 1,164 (34.7) | 176 (47.6) | 48 (35.6) | |||

| ≥75 | 688 (12.8) | 483 (14.4) | 64 (17.3) | 41 (30.4) | |||

| Location (%) | |||||||

| Head and neck | 1,022 (19.0) | 322 (9.6) | <0.001 | 75 (20.3) | 13 (9.6) | <0.001 | |

| Trunk | 2,265 (42.2) | 958 (28.6) | 144 (38.9) | 32 (23.7) | |||

| Upper limb and shoulder | 1,122 (20.9) | 787 (23.5) | 48 (13.0) | 19 (14.1) | |||

| Lower limb and hip | 951 (17.7) | 1,284 (38.3) | 101 (27.3) | 71 (52.6) | |||

| Others | 10 (0.2) | 5 (0.1) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | |||

| Subtype of melanoma (%) | |||||||

| Superficial spreading | 1,373 (25.6) | 884 (26.3) | 0.357 | 56 (15.1) | 16 (11.9) | 0.571 | |

| Nodular | 1,379 (25.7) | 774 (23.1) | 150 (40.5) | 65 (48.1) | |||

| Lentigo maligna melanoma | 47 (0.9) | 27 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | |||

| Acral lentiginous | 153 (2.8) | 134 (4.0) | 19 (5.1) | 12 (8.9) | |||

| Others | 281 (5.2) | 135 (4.0) | 23 (6.2) | 5 (3.7) | |||

| Melanoma not specified | 2,137 (39.8) | 1,402 (41.8) | 121 (32.7) | 37 (27.4) | |||

| Clark classification (%) | |||||||

| II | 102 (1.9) | 90 (2.7) | 0.103 | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0.857 | |

| III | 565 (10.5) | 352 (10.5) | 8 (2.2) | 3 (2.2) | |||

| IV | 3,300 (61.5) | 2,082 (62.0) | 144 (38.9) | 49 (36.3) | |||

| V | 690 (12.8) | 409 (12.2) | 160 (43.2) | 70 (51.9) | |||

| Unknown | 713 (13.3) | 423 (12.6) | 57 (15.4) | 13 (9.6) | |||

| Breslow thickness (mean ± SD) (%) | 316.3±241.2 | 290.5±231.5 | <0.001 | 727.9±205.2 | 699.3±208.6 | 0.234 | |

| <1.0 mm | 664 (12.4) | 483 (14.4) | <0.001 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.457 | |

| 1.1–2.0 mm | 1,539 (28.7) | 1,120 (33.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| 2.1–4.0 mm | 1,800 (33.5) | 1,030 (30.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| >4 mm | 1,359 (25.3) | 715 (21.3) | 369 (99.7) | 134 (99.3) | |||

| Unknown | 8 (0.1) | 8 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.7) | |||

| Mitotic rate (%) | |||||||

| <1 | 253 (4.7) | 160 (4.8) | 0.021 | 8 (2.2) | 1 (0.7) | 0.066 | |

| 1 | 427 (8.0) | 323 (9.6) | 10 (2.7) | 2 (1.5) | |||

| ≥2 | 2,322 (43.2) | 1,462 (43.6) | 183 (49.5) | 59 (43.7) | |||

| Unknown | 2,368 (44.1) | 1,411 (42.0) | 169 (45.7) | 73 (54.1) | |||

| Ulceration (%) | |||||||

| Yes | 2,434 (45.3) | 1,321 (39.4) | <0.001 | 369 (99.7) | 135 (100.0) | 0.546 | |

| No | 2,921 (54.4) | 2,026 (60.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Unknown | 15 (0.3) | 9 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | |||

Among the patients with stage IIID disease, there was no significant difference in age, and the average patient age was slightly older in women than in men (59.1±15.5 vs. 61.2±18.1 years, P=0.121). The Breslow thickness also showed the same trend (727.9±205.2 vs. 699.3±208.6 mm, P=0.234), and the baseline data were basically consistent among those with stage III disease.

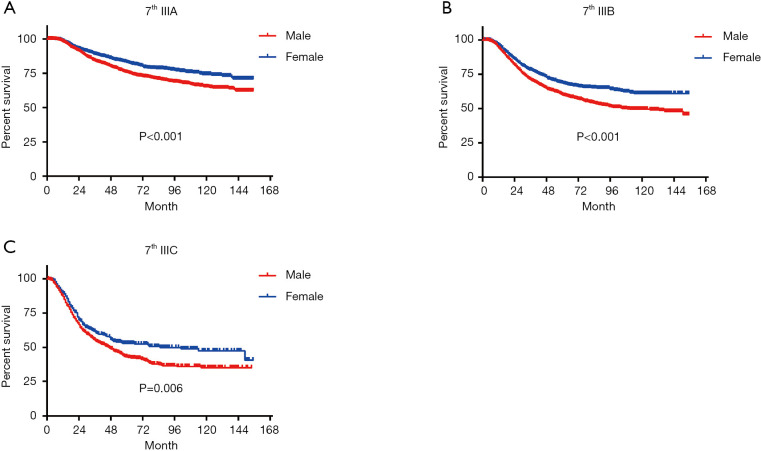

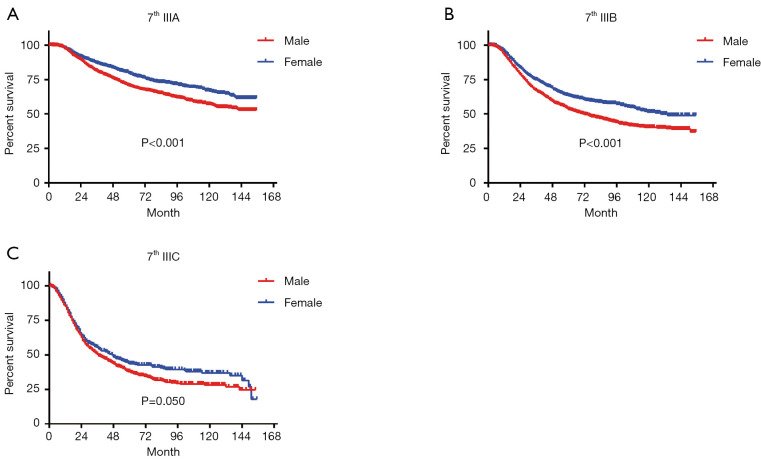

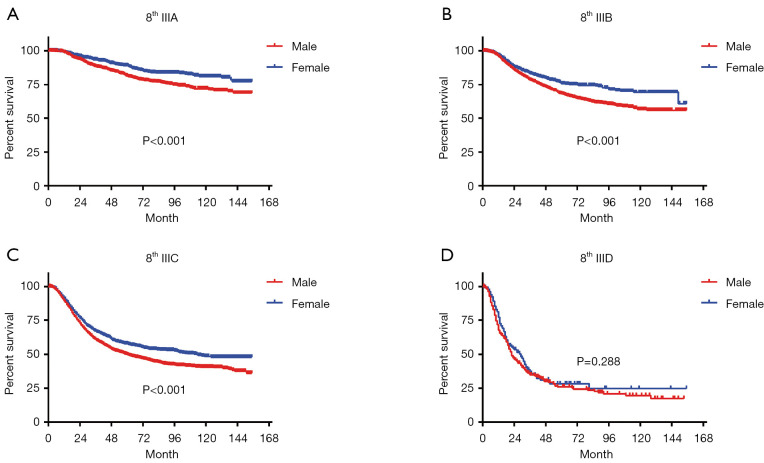

In terms of differences in sex-specific survival, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed significant differences in both OS and MSS between male and female patients with stage IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC disease based on the 7th edition of the staging system (Figures 2,3). The only nonsignificant difference in OS was among patients with stage IIIC disease (P=0.050, borderline significant). After classifying patients based on the 8th edition of the staging system, there were significant differences in both OS and MSS between males and females with stage IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC disease (P<0.001). However, among patients with stage IIID disease, neither OS (P=0.288) nor MSS (P=0.312) differed between males and females (Figures 4,5). There were more Caucasians among males with stage III and IIID disease. To determine whether there was a sex-specific survival advantage among white patients and nonwhite patients, we estimated the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with stage III and IIID disease. There was a significant difference in OS between males and females among white patients (P<0.001) and among nonwhite patients (P=0.002) with stage III disease. In contrast, no significant difference was observed in OS between males and females among white patients (P=0.323) and among nonwhite patients (P=0.840) with stage IIID disease (Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Long-term OS based on the 7th edition of the TNM staging system. (A) Stage IIIA; (B) stage IIIB; (C) stage IIIC. OS, overall survival.

Figure 3.

Long-term MSS based on the 7th edition of the TNM staging system. (A) Stage IIIA; (B) stage IIIB; (C) stage IIIC.

Figure 4.

Long-term OS based on the 8th edition of the TNM staging system. (A) Stage IIIA; (B) stage IIIB; (C) stage IIIC; (D) stage IIID. OS, overall survival.

Figure 5.

Long-term MSS based on the 8th edition of the TNM staging system. (A) Stage IIIA; (B) stage IIIB; (C) stage IIIC; (D) stage IIID. MSS, melanoma-specific survival.

Further Cox analysis suggested that among all stage III patients, after adjusting for age, tumor location, Breslow thickness, mitotic rate, and ulceration, males with stage III disease had a significantly increased risk of mortality (HR =1.431, 95% CI: 1.311–1.562, P<0.001) (Table 2). There were no significant difference in the factors used to adjust the analysis between males and females with stage IIID disease (HR =1.133, 95% CI: 0.847–1.517, P=0.400) (Table 3).

Table 2. Cox analysis of the sex-specific risk of mortality among all stage III patients.

| P value | HR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male vs. female | <0.001 | 1.431 | 1.311–1.562 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval. Models adjusted by age, location, Breslow thickness, mitotic rate, ulceration.

Table 3. Cox analysis of the sex-specific risk of mortality among all stage IIID patients.

| P value | HR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male vs. female | 0.400 | 1.133 | 0.847–1.517 |

Models adjusted by age, location, Breslow thickness, mitotic rate.

There was a significant difference in age between males and females with stage III disease but not among those with stage IIID disease. To verify whether age is related to survival, we further divided the patients into the following groups based on age: <55, 55–74 and ≥74 years. Cox analysis was performed in all groups. The results suggest that the risk of mortality in males is significantly higher than that in females in all age groups (P<0.001). In patients with stage IIID disease, there was no significant sex-specific difference in survival in any age group (Table 4).

Table 4. Cox analysis of the sex-specific risk of mortality among patients in different age groups.

| Age, years | All stage III patients | Stage IIID patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | ||

| <55 | <0.001 | 1.397 | 1.177–1.659 | 0.916 | 1.028 | 0.618–1.709 | |

| 55–74 | <0.001 | 1.566 | 1.275–1.924 | 0.440 | 1.175 | 0.780–1.771 | |

| ≥74 | <0.001 | 1.500 | 1.245–1.807 | 0.748 | 1.113 | 0.578–2.114 | |

Models adjusted by location, Breslow thickness, and mitotic rate.

Discussion

In the new 8th edition of the staging system, the staging of most tumors has been adjusted. For example, in esophageal adenocarcinoma, stage I has been redistributed. However, it was found that survival did not differ between patients with the new stages IA and IB (11). Skin melanoma staging was adjusted mainly in stage III, with the addition of another subgroup to further differentiate among patients with regard to survival. The application of the 8th edition of the staging system led to a the 5-year tumor-specific survival rate ranging from 93% (stage IIIA) to 32% (stage IIID), showing better discrimination than the 7th edition of the staging system, which ranged from only 78% (stage IIIA) to 40% (stage IIIC) (12).

Although the difference in survival between subgroups is very obvious in the 8th edition of the staging system, we observed a very interesting phenomenon. Among stage IIID patients, the survival advantage of female sex does not exist, which may be due to the combination of T4b + N3 in stage IIID disease (i.e., more lymph node metastasis and relatively advanced tumors). Hence, stage IIID patients experience a lower survival rate, which may affect the advantage of women (13). In patients with stages IIIA–IIIC disease, the tumor prognosis is better, making a sex-specific advantage more feasible. Therefore, males and females may have significantly different survival rates.

The higher female survival rates may be related to multiple factors. In this study, among patients with stage III disease, male patients were generally older; no such difference in age was observed in stage IIID patients. To verify whether the difference in survival was driven by age, we performed a Cox analysis of different age groups and found that the trend remained the same in each age group as in the entire group. The location of the disease may be one of the reasons for this observation. Some studies have found that the most common location of malignant melanoma in women is the lower limb, while that in men is the trunk. The surgical margins and external stresses differ in various parts of the body, which may lead to differences in prognosis (14-17). Our baseline data also confirm this distribution difference. Among all stage III patients, male patients had worse Breslow thickness and a higher ulceration rate, but no significant differences were observed in these factors between males and females with stage IIID disease. These factors were included as predictors of survival in melanoma patients according to the current 8th edition of the AJCC staging system. However, after adjusting for multiple factors, Cox analysis showed that there was still a significant difference in age between males and females among all patients with stage III disease but not among the subgroup of patients with stage IIID disease. On the other hand, some studies have suggested that women are more likely to apply sunscreen in their daily lives, thereby reducing their UV exposure, which is considered the most important environmental factor leading to skin melanoma and affecting prognosis (4,14,18). In addition, studies on stage I melanoma have found that only in the >60-year-old group is female sex associated with a higher survival rate (10). Moreover, pregnant women have better survival rates, possibly due to sex hormone secretion. However, there is no clear evidence to support this conjecture (19).

Genetics is also a potential factor affecting the survival advantage in females. Some studies have analyzed The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database and found that the missense mutation burden in males was significantly higher than that in females [median in males 298 vs. females 211.5; male to female ratio (M: F) =1.85, 95% CI: 1.44 to 2.39] (19). The link between the burden of missense mutations and the immune response may partially explain the survival advantages in females. Studies have found that inherited MC1R mutations at specific sites are associated with prolonged survival in females, whereas in males, these mutations do not affect survival (20). However, there are still few studies on the roles of genetics in sex-based differences, and there is no comprehensive theoretical basis.

In our study, a large number of samples were analyzed, and this real-world study provides information that more closely reflect the real situation than information obtained from RCTs, which use carefully selected patients populations. This study was performed to evaluate the sex-specific survival advantage, so we used Cox analysis and adjusted for multiple factors to ensure the reliability of the results.

There are also some limitations of our research. Although the overall sample size was very large, the number of patients with stage IIID disease was small, which may have affected the results. Although it is difficult to collect sufficient patient samples for some stages of disease, further large-scale controlled studies can still be expected to confirm this result.

Conclusions

In summary, we analyzed patients with stage III disease based on the 8th edition of the staging system. Among patients with stages IIIA–IIIC disease, female patients had a significantly higher survival rate than males. However, this sex-specific benefit did not exist among patients with stage IIID disease. This research can provide a theoretical basis for future clinical trials on diagnosis and prognosis.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 81800241), Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (SJCX20_0484) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (14380479).

Ethics Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments revised in 2013 or comparable ethical standards.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3332

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-3332). Dr. Mo serves as an unpaid Section Editor of Annals of Translational Medicine from Jan 2020 to Dec 2020. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87-108. 10.3322/caac.21262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Che G, Huang B, Xie Z, et al. Trends in incidence and survival in patients with melanoma, 1974-2013. Am J Cancer Res 2019;9:1396-414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaikh WR, Dusza SW, Weinstock MA, et al. Melanoma Thickness and Survival Trends in the United States, 1989 to 2009. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;108:djv294. 10.1093/jnci/djv294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang DD, Salciccioli JD, Marshall DC, et al. Trends in malignant melanoma mortality in 31 countries from 1985 to 2015. Br J Dermatol 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1111/bjd.19010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hieken TJ, Glasgow AE, Enninga EAL, et al. Sex-Based Differences in Melanoma Survival in a Contemporary Patient Cohort. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2020;29:1160-7. 10.1089/jwh.2019.7851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crocetti E, Fancelli L, Manneschi G, et al. Melanoma survival: sex does matter, but we do not know how. Eur J Cancer Prev 2016;25:404-9. 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Sharouni MA, Witkamp AJ, Sigurdsson V, et al. Sex matters: men with melanoma have a worse prognosis than women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019;33:2062-7. 10.1111/jdv.15760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma staging: Evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:472-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:6199-206. 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khosrotehrani K, Dasgupta P, Byrom L, et al. Melanoma survival is superior in females across all tumour stages but is influenced by age. Arch Dermatol Res. 2015;307:731-40. 10.1007/s00403-015-1585-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mo R, Chen C, Pan L, et al. Is the new distribution of early esophageal adenocarcinoma stages improving the prognostic prediction of the 8(th) edition of the TNM staging system for esophageal cancer? J Thorac Dis 2018;10:5192-8. 10.21037/jtd.2018.08.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanaki T, Stang A, Gutzmer R, et al. Impact of American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition classification on staging and survival of patients with melanoma. Eur J Cancer 2019;119:18-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haydu LE, Lo SN, McQuade JL, et al. Cumulative Incidence and Predictors of CNS Metastasis for Patients With American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th Edition Stage III Melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:1429-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pérez-Gómez B, Aragones N, Gustavsson P, et al. Do sex and site matter? Different age distribution in melanoma of the trunk among Swedish men and women. Br J Dermatol 2008;158:766-72. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08429.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gong HZ, Zhang S, Zheng HY, et al. The role of mechanical stress in the formation of plantar melanoma: a retrospective analysis of 72 chinese patients with plantar melanomas and a meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020;34:90-6. 10.1111/jdv.15933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheraghlou S, Christensen SR, Agogo GO, et al. Comparison of Survival After Mohs Micrographic Surgery vs Wide Margin Excision for Early-Stage Invasive Melanoma. JAMA Dermatol 2019;155:1-8. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Utjés D, Malmstedt J, Teras J, et al. 2-cm versus 4-cm surgical excision margins for primary cutaneous melanoma thicker than 2 mm: long-term follow-up of a multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet 2019;394:471-7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31132-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutiérrez-González E, Lopez-Abente G, Aragones N, et al. Trends in mortality from cutaneous malignant melanoma in Spain (1982-2016): sex-specific age-cohort-period effects. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019;33:1522-8. 10.1111/jdv.15565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lira FE, Podlipnik S, Potrony M, et al. Inherited MC1R variants in patients with melanoma are associated with better survival in women. Br J Dermatol 2020;182:138-46. 10.1111/bjd.18024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta S, Artomov M, Goggins W, et al. Gender Disparity and Mutation Burden in Metastatic Melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107:djv221. 10.1093/jnci/djv221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as