Abstract

Background

The RNA interference (RNAi) pathway is a gene regulation mechanism that utilizes small RNA (sRNA) and Argonaute (Ago) proteins to silence target genes. Our previous work identified a functional RNAi pathway in the protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica, including abundant 27 nt antisense sRNA populations which associate with EhAgo2–2 protein. However, there is lack of understanding about the sRNAs that are bound to two other EhAgos (EhAgo2–1 and 2–3), and the mechanism of sRNA regulation itself is unclear in this parasite. Therefore, identification of the entire pool of sRNA species and their sub-populations that associate with each individual EhAgo protein would be a major step forward.

Results

In the present study, we sequenced sRNA libraries from both total RNAs and EhAgo bound RNAs. We identified a new population of 31 nt sRNAs that results from the addition of a non-templated 3–4 adenosine nucleotides at the 3′-end of the 27 nt sRNAs, indicating a non-templated RNA-tailing event in the parasite. The relative abundance of these two sRNA populations is linked to the efficacy of gene silencing for the target gene when parasites are transfected with an RNAi-trigger construct, indicating that non-templated sRNA-tailing likely play a role in sRNA regulation in this parasite. We found that both sRNA populations (27 nt and 31 nt) are present in the related parasite Entamoeba invadens, and are unchanged during the development. In sequencing the sRNAs associating with the three EhAgo proteins, we observed that despite distinct cellular localization, all three EhAgo sRNA libraries contain 27 nt sRNAs with 5′-polyphosphate (5′-polyP) structure and share a largely overlapping sRNA repertoire. In addition, our data showed that a fraction of 31 nt sRNAs associate with EhAgo2–2 but not with its mutant protein (C-terminal deletion), nor other two EhAgos, indicating a specific EhAgo site may be required for sRNA modification process in the parasite.

Conclusion

We identified a new population of sRNA with non-templated oligo-adenylation modification, which is the first such observation amongst single celled protozoan parasites. Our sRNA sequencing libraries provide the first comprehensive sRNA dataset for all three Entamoeba Ago proteins, which can serve as a useful database for the amoeba community.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-020-07275-6.

Keywords: RNAi, Small RNA, Small RNA sequencing, Argonaute, Small RNA oligo-adenylation, Parasite

Background

Thought to be evolved from an ancient anti-viral defense mechanism, RNA interference (RNAi) and its gene regulation pathways are conserved in most eukaryotic organisms [1–3]. RNAi can be triggered by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), which is processed by Dicer into short interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes. One strand of the siRNA duplex is then loaded into Argonaute (Ago) protein to form the RNA induced silencing complex (RISC). The RISC leads to the inactivation of target mRNAs through mechanisms of posttranscriptional or transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS/TGS) [4]. In addition to the above mentioned RNAi pathway, an amplified gene silencing mechanism involving the activity of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRPs) has been identified in plants, nematodes and fungi [5, 6]. RdRPs respond to a primary sRNA pool and generate secondary sRNAs. In plants and fungi, RdRPs use the cleaved mRNA as template to synthesize dsRNA which are then processed by Dicer to generate secondary sRNAs [5]. In Caenorhabditis elegans, RdRPs synthesize secondary sRNAs de novo. These secondary sRNAs are called 22G sRNAs for being 22 nt in size and with antisense orientation, having both 5′-end triphosphate structure and guanosine bias [7].

There are different classes of sRNAs including siRNAs, miRNAs, and Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) [8]. Recent studies have shown that sRNAs are modified for different cellular functions [9, 10]. Uridylation of siRNAs and piRNAs is observed in many systems including Chlamydomonas [11], C. elegans [12], Arabidopsis [13], Drosophila [14], and mammalian cells [15, 16]. Mono-adenylation is reported to have a stabilizing effect on mature miRNAs, and miRNA precursors are often modified by uridylation for degradation [14]. In fission yeast, a fraction of Argonaute-bound siRNAs are found with non-templated adenosines at the 3′-end [17]. Thus, sRNA modification with non-templated uridine(s) or adenosine(s) among these model organisms are used as a mechanism for regulating sRNAs: either leading to sRNA degradation (uridylation), miRNA protection (mono-adenylation) or sRNA turnover in fission yeast (di-adenylation and di-uridylation).

The protozoan parasite E. histolytica causes amebiasis, a major health concern in underdeveloped countries [18, 19]. The parasite has two life stages: a dormant, environmentally resistant cyst form and a proliferative trophozoite form, which is capable of causing invasive disease. Our previous work has identified a functional RNAi pathway in this parasite [20–23]. We found that E. histolytica has abundant 27 nt sRNAs with a 5′-polyP structure, a feature that is seen in the secondary sRNAs in C. elegans and nematode parasite Ascaris suum [7, 24]. There are three EhAgo proteins: EhAgo2–1 (EHI_186850), EhAgo2–2 (EHI_125650), and EhAgo2–3 (EHI_177170) that have distinct subcellular locations including the nucleus (EhAgo2–2), perinuclear ring (EhAgo2–1, EhAgo2–3), and cytosol (EhAgo2–3) [25]. Our structural domain analysis showed that all three EhAgos have a conserved PAZ and PIWI domain [25]. We demonstrated that EhAgo PAZ domains are essential for sRNA binding for all three EhAgos, and sRNA binding affects cellular localization of EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo2–3 but not EhAgo2–2 [25]. To better understand the RNAi mechanism(s) in this parasite, we ask three questions (i) what are the full spectrum of sRNA species in this parasite? (ii) do the three EhAgos bind different sRNA sub-populations? (iii) are sRNAs themselves regulated in Entamoeba?

In this report, we performed high throughput sRNA sequencing for size-fractionated total RNAs and three EhAgo-bound sRNAs. We demonstrated that two dominant sRNA populations are present: one at 27 nt and the other at 31 nt, with the latter containing non-templated 3–4 adenosines at the 3′-end, indicating an oligo-adenylation modification event of the sRNAs in the E. histolytica parasite. We further expanded our sRNA sequencing effort for 31 nt populations in the related reptilian parasite E. invadens, and found that the 31 nt sRNA populations are not changed during development. Using an RNAi-trigger gene silencing approach, we showed that the relative abundance of the two sRNA populations is reversed when a target gene is unable to be silenced. Sequencing of three EhAgo immunoprecipitation (IP) RNA libraries showed significant overlap of sRNA species, mainly targeting retrotransposons and ~ 226 genes that are silenced in this organism. We also found that there is a fraction of 31 nt sRNA reads that are in the EhAgo2–2 IP library but not in its mutant, nor the other two EhAgos IP libraries. Overall, our study provides the first comprehensive dataset for sRNAs bound to the three EhAgo proteins, which can serve as a useful database for the Entamoeba community. The finding of sRNAs with oligo-adenylation revealed an additional layer of sRNA regulation control and functional diversity in this single celled deep-branching eukaryotic pathogen.

Results

Two small RNA populations (27 nt and 31 nt) are identified in Entamoeba

In order to identify the complete spectrum of sRNA species in Entamoeba, including those that may have diverse structures, modifications, or may be less abundant, we decided to extensively explore the endogenous sRNA populations in E. histolytica by sequencing total RNA fractions (15-45 nt) from wildtype E. histolytica trophozoites. We fractionated the total RNA into two RNA size fractions (15-30 nt and 30-45 nt). The recovered RNAs from both fractions were cloned by 5′-P independent cloning method (using tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (TAP) to convert 5′-polyP into 5′-monoP) (Suppl. Table 1). Although we previously reported similar sRNA libraries, those libraries were on a small-scale sequencing level using Sanger sequencing or pyrosequencing approaches, and sRNAs identified were in the 15-30 nt range [21, 23]. The goal in this study is to provide a full account of Entamoeba sRNAs, including potential sRNA species with modifications, using the current Illumina deep sequencing platform.

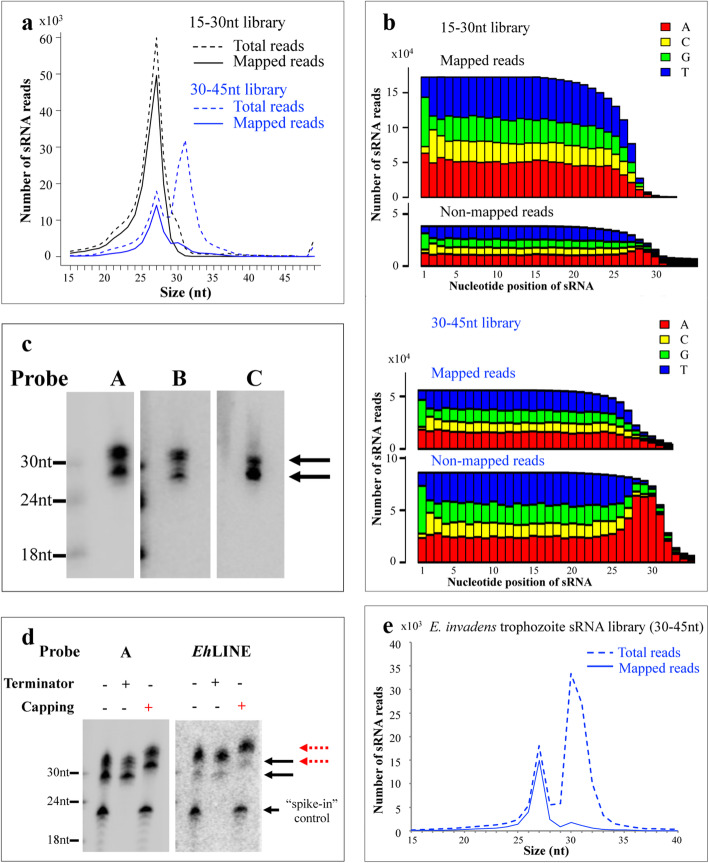

The sRNA size distribution of the two libraries (15-30 nt and 30-45 nt libraries) were cloned by TAP method, as shown in Fig. 1a. We observed only one sRNA population (a sharp 27 nt peak) for the 15-30 nt library, which matched with previous results [23]. However, for the 30-45 nt library, we identified two sRNA populations (peaks at 27 nt and 31 nt). The 27 nt peak is likely a carry-over from the abundant 27 nt population, but the peak at 31 nt was unexpected and new to us. We characterized and mapped the sRNA sequences from both libraries using a custom data processing pipeline (Suppl. Fig. 1). The unique reads were mapped to tRNA and rDNA sequences using Bowtie [26]; the remaining reads were aligned to the amebic EhLINEs (Long Interspersed Nuclear Elements), the genome, and transcriptome. This analysis revealed that most reads in 27 nt peak can be mapped to the genome. The sRNA reads in the 31 nt peak did not map to the genome (Table 1 and Fig. 1a). To understand why the 31 nt sRNAs could not be mapped to the genome, we plotted the nucleotide frequency at each position for the non-mapped reads and identified an oligo-A tail prominent at the 3′-end as the reason for these reads being not mapped to the genome (Fig. 1b). In order to map the 31 nt sRNA reads, we clipped the sequence reads after the 27 nt position using a custom Python script, then re-mapped to the genome. Our analysis revealed that these clipped sequences can now map to the genome, indicating that the non-templated 3–4 As were added to the existing 27 nt sRNAs (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

E. histolytica has two sRNA populations (27 nt and 31 nt) and 31 nt sRNA is oligo-A modified at 3′-end. a Size distribution for two size-fractionated sRNA libraries (15-30 nt and 30-45 nt). Both libraries were cloned using 5′-P independent cloning method (TAP). Total reads (dashed lines) and mapped reads (solid lines) are shown. The 15-30 nt size-fractionated library shows a single peak at 27 nt for both total and mapped reads. The 30-45 nt size-fractionated library has two sRNA peaks (27 nt and 31 nt) for the total reads, and only the 27 nt sRNAs, but not 31 nt sRNAs, can be mapped to genome. b Nucleotide distribution analysis for the mapped and non-mapped reads. There is a 5′-G bias for the first nucleotide in all populations. The 30–45 non-mapped reads show a 5′-G bias for the first nucleotide, and a string of 3 or 4 As are identified at 3′-end. After trimming of the 3′-end As, these reads can be remapped to the genome (Table 1) indicating non-templated oligo-A tailing event to the 27 nt sRNAs. c Northern blot detects both 27 nt and 31 nt sRNA populations. Three sRNAs (probes called A, B and C) were cloned in both size sRNA populations; Northern blot analysis detected signals at both sRNA sizes, indicating that the two sRNA species co-exist in the cell. A sRNA enriched RNA from E. histolytica trophozoites (20 μg) was used for each sample and probed with end-labeled [32P] oligonucleotide probes corresponding to the cloned sRNAs, see Suppl. Table 7 and Suppl. original blot for Fig. 1c. d Both 27 nt and 31 nt sRNA populations are resistant to cleavage by Terminator enzyme, they are shifted for one nucleotide distance via capping assay, indicating a 5′-polyP structure for both sRNA populations. A “spike-in” control of 22 nt RNA with a 5′-monoP is readily degraded by Terminator enzyme. An increase in size following treatment with capping enzyme indicates that RNAs have 5′-di- or tri-phosphate structure. The probe “A” and a probe specific to EhLINE were used (Suppl. Table 7 and Suppl. original blot for Fig. 1d.) e E. invadens 30-45 nt size-fractionated library has two sRNA peaks. Similar to E. histolytica, the 27 nt peak can be mapped to the genome but not 31 nt peak. The plot shows the trophozoite dataset (similar plots are observed for two other time point datasets, data not shown)

Table 1.

Genomic categories that are mapped by sRNA reads by size-fractionated total RNA libraries (TAP cloning method)

| Size-fractionated total RNA libraries, 5′ P-independent cloning, WT | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | 15-30nt (27nt sRNAs) | 30-45nt # (27nt and 31nt sRNAs) | 3'-end trimmed * (31nt sRNAs trimmed off oligo-As) |

| Total reads | 624,954 | 411,419 | |

| Unique (unique/total reads) | 242,277 (38.8%) | 171,309 (41.6%) | 86,031 |

| tRNAa,S | 2,343 (1.0%) | 2,848 (1.7%) | 1,035 (1.2%) |

| rRNAa,S | 12,957 (5.3%) | 18,235 (10.6%) | 450 (0.5%) |

| LINEsa,AS | 16,424 (6.8%) | 8,492 (5.0%) | 23,999 (27.9%) |

| Map to rest of genomea | 172,261 (71.1%) | 55,703 (32.5%) | 36,651 (42.6%) |

| Map to predicted ORFsa,AS | 124,770 (51.5%) | 37,145 (21.7%) | 27,508 (32%) |

| Not mapped to genome (%) | 38,292 (15.8%) | 86,031 (50.2%) | 23,896 (27.8%) |

a Number of unique reads divided by total unique reads

S Most reads are in sense orientation

AS Most reads are in antisense orientation

# Only 27nt sRNAs can be mapped to the genome, not 31nt sRNAs

* The 31nt sRNAs (non-mapped reads in 30-45nt library) were trimmed from 3' end into 27nt size, then they can be mapped to the genome.

We noticed that the reads that map to tRNA and rRNA are predominantly in the sense orientation. The tRNA and rRNA reads are inevitably present in almost all published sRNA sequencing libraries. These tRNA and rRNA reads are often considered partial degradation products as they are highly abundant in the cell, with a few exceptions [27, 28]. Of note, the number of reads that map to rRNA is significantly less in the category of 31 nt sRNAs (Table 1, 0.5% for 3′-end trimmed), compared to the non-modified 27 nt sRNAs (Table 1, 5.3% for 15-30 nt library and 10.6% for 30-45 nt library).

The E. histolytica genome is highly populated with retrotransposons and repeat elements including EhLINEs, EhSINEs (Short Interspersed Nuclear Elements), and EREs (Entamoeba Repeat Elements) [29]. There are thousands of copies of EhLINEs in the genome, but they are considered “inactive”. Genome sequencing has not identified any EhLINEs which have completed open reading frames (ORF) [30]. Interestingly, reads mapped to EhLINEs make up almost 28% of these 31 nt sRNAs compared with < 10% in the 27 nt sRNAs (the non-modified populations), indicating a possible link between retrotransposon control and sRNA modification in the parasite.

In order to determine if the sRNA species overlap between the 27 nt and 31 nt populations, we performed alignment analysis of the trimmed 31 nt sRNAs directly against the 27 nt sRNA reads. We found that most (85%) of the trimmed 31 nt reads can be mapped to the 27 nt reads, indicating a high overlap between two sRNA populations. Consequently, we found that both sRNA populations target almost the same set of genes, and the number of unique sRNAs mapped to these genes from both datasets are correlated (Suppl. Fig. 2A). However, the abundance of individual sRNA cloned in each population is not well correlated (Suppl. Fig. 2B), indicating that the abundance level of sRNAs within the two sRNA populations may be regulated differently within the cell.

We selected a few sRNAs which were cloned in both the 27 nt and 31 nt populations and designed probes based on the sequences of these chosen sRNAs. We detected the two expected sRNA sizes by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 1c). In addition, we tested susceptibility of both sRNA populations to capping enzyme and Terminator exonuclease. As shown in Fig. 1d, both sRNA populations are shifted one nucleotide higher by the capping enzyme treatment, indicating that these sRNAs have a 5′ di- or tri-phosphate structure. Additionally, both sRNAs are resistant to Terminator exonuclease treatment, which degrades 5′ mono-phosphate RNA. A pre-labeled radioactive 5′-mono-phosphate RNA (a spike-in control) is not shifted by capping enzyme but can be readily degraded by Terminator exonuclease. Taken together, both sRNA sequencing data and Northern blot analyses confirm that E. histolytica contains 27 nt as well as 31 nt sRNAs. Both sRNA populations have 5′-end polyP structure and the 31 nt sRNAs differ from the 27 nt sRNAs at 3′-end by non-templated 3 or 4 adenosines.

Both small RNA populations (27 nt and 31 nt) are unchanged during development of E. invadens

E. invadens is a reptilian parasite that is used to study amebic development in vitro [31, 32]. Previously, we sequenced the 27 nt sRNA population from E. invadens parasites, and mapped these sRNAs to ~ 700 genes with low expression levels [22]. However, these genes with antisense sRNAs appear to be not developmentally regulated as sequencing of the 27 nt population at four developmental time-points showed identical sRNA targeted gene sets [22]. We first sought to check whether the 31 nt population was also present in E. invadens. Total RNA samples from trophozoites, 72 h encysted parasites, and parasites after 8 h excystation were radioactively labeled and separated on a denaturing 15% polyacrylamide gel. Two sRNA bands can be easily detected at 27 nt and 31 nt sizes (Suppl. Fig. 3A), indicating that E. invadens has both sRNA populations. To sequence the 31 nt sRNA population, we size-fractioned the 30-45 nt RNA and made sRNA libraries using the TAP method for all three samples. Similar to the observation in E. histolytica, the size distribution and mapping features of these libraries all showed 27 nt and 31 nt peaks, and 31 nt peak reads could not be directly mapped to the genome (Fig. 1e). Nucleotide compositions of the 31 nt population clearly show an oligo-A tail (Suppl. Fig. 3B). Genome mapping of these three libraries and mapping of their tail-clipped sequences are shown in Suppl. Table 2. Thus, we conclude that E. invadens also contains a sRNA population with non-templated A-tail. Using a similar approach as outlined previously [22], we analyzed the genes that mapped by sRNA from 31 nt populations among trophozoite, 72 h encystation, and 8 h excystation libraries. The overlap from these libraries is significant as shown in Suppl. Fig. 3C, indicating that the development process does not affect these genes, matching previous results with the sRNA from the 27 nt population. In summary, endogenous genes with antisense sRNAs seemed to be “locked” for silencing during development, which is reflected in both 27 nt and 31 nt populations.

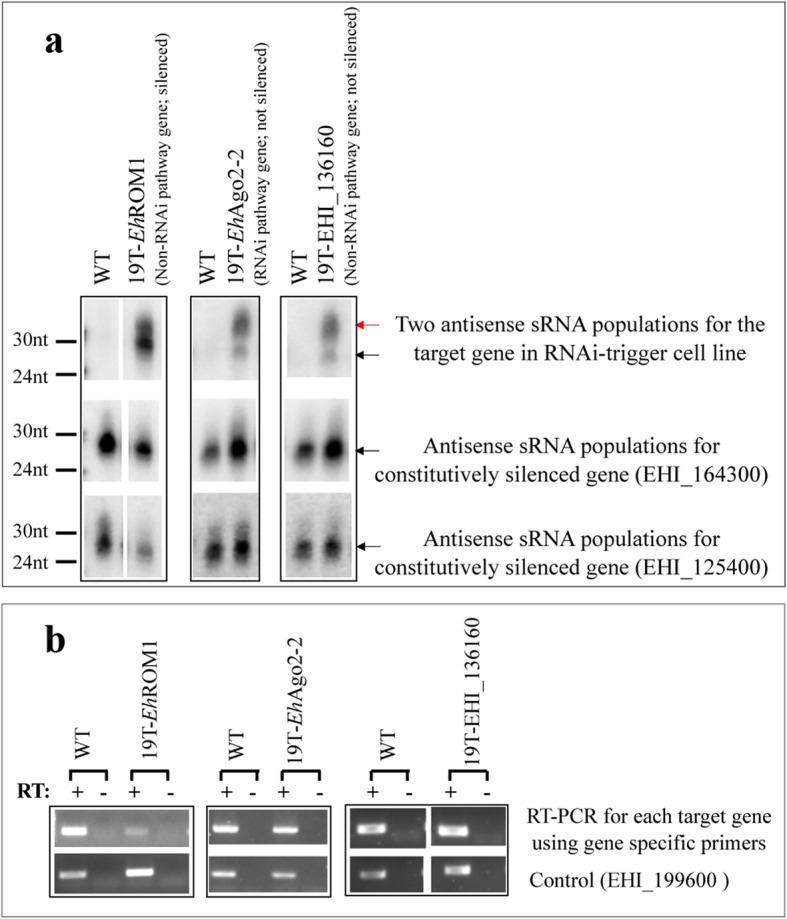

The relative abundance of two sRNA populations is linked to gene silencing efficacy

We sought to explore the possible role of sRNA oligo-adenylation in the regulation of sRNA turnover in amoeba, a function that was ascribed to the di-adenylation of siRNAs in yeast [17]. We used cell lines that were transfected with RNAi-trigger plasmids. This approach was previously developed in our lab [33–35], and utilizes an episomal plasmid to overexpress a “trigger” sequence fused in-frame with a target gene. A 132 bp region of an endogenously silenced gene of EHI_197520 is used as trigger sequence, and is termed 19 T. Figure 2a shows that there are two bands corresponding to the size of 27 nt and 31 nt sRNA populations and can be detected for each target gene. We also observed that the relative abundance of two sRNA populations is indicative as to whether or not the target gene is silenced: for the cell line in which the EhROM1 gene (E. histolytica rhomboid protease 1, an intramembrane protease [36]) is silenced (Fig. 2b, the gene is downregulated by approximately 5-fold), there are much higher levels of the 27 nt population than the 31 nt population (Fig. 2a, lane labeled as 19 T-EhROM1; the ratio of the sRNA bands (31 nt/27 nt) measured by densitometry is 0.57). In contrast, the cell line in which the EhAgo2–2 gene is not silenced (Fig. 2b, the change in gene expression is negligible, the fold change is 1.45), the 31 nt population is more abundant than the 27 nt population (Fig. 2a, lane labeled as 19 T-EhAgo2–2; the ratio of the sRNA bands (31 nt/27 nt) is 6.7). In addition, we attempted to silence a gene that is not involved in RNAi (EHI_136160, a putative calreticulin precursor), and observed a similar phenomenon whereby the target gene was not silenced but a prominent 31 nt sRNA band was detected (Fig. 2a and b for lanes labeled as 19 T-EHI_136360; the ratio of the sRNA bands (31 nt/27 nt) is 7.0; there is no change in gene expression, the fold change is 0.95). Control sRNAs for constitutively silenced genes (EHI_164300 and EHI_125400) have signal that correspond mostly to the 27 nt population. Thus, the two sRNA populations can be detected in the cell lines transfected with RNAi-trigger plasmids, and their abundance level is linked to gene silencing efficacy.

Fig. 2.

Northern blots detect relative abundance of two sRNA populations in RNAi-trigger cell lines. a Northern blot analysis detects antisense sRNA at both 27 nt and 31 nt sizes for each target gene. A gene specific sense probe was used for each target gene, and antisense signals are detected in the respective RNAi-trigger cell line. Relative abundance of sRNA populations: 27 nt > 31 nt in 19 T-EhROM1 cell line with EhROM1 gene silenced; in contrast, 27 nt < 31 nt in cell lines (19 T-EhAgo2–2, 19 T-EHI_136160), where the target genes are not silenced. The ratio of the sRNA bands (31 nt/27 nt) measured by densitometry is 0.57 for 19 T-EhROM1; 6.7 for 19 T-EhAgo2–2 and 7.0 for 19 T-EHI_136160. Antisense sRNAs to constitutively silenced genes EHI_164300 and EHI_125400 as controls, which further demonstrate the relative abundance pattern of 27 nt > 31 nt for the silenced genes. Red arrow points to 31 nt sRNA band, black arrow points to 27 nt sRNA band. See also Suppl. original blots for Fig. 2a. b Semi-quantitative RT-PCRs using gene specific primers. Gene expression levels of target gene were measured in RNAi-trigger cell lines: EhROM1 is silenced but the other two genes have equal expression in WT and RNAi-trigger cell lines. The fold change in gene expression compared to the control: 0.23 for 19 T-EhROM1; 1.45 for 19 T-EhAgo2–2 and 0.95 for 19 T-EHI_136160. EHI_199600 is used as a loading control and -RT samples are shown. All RT-PCRs are specific, as a single band was generated for each primer set

The three EhAgo proteins all bind to 27 nt sRNAs

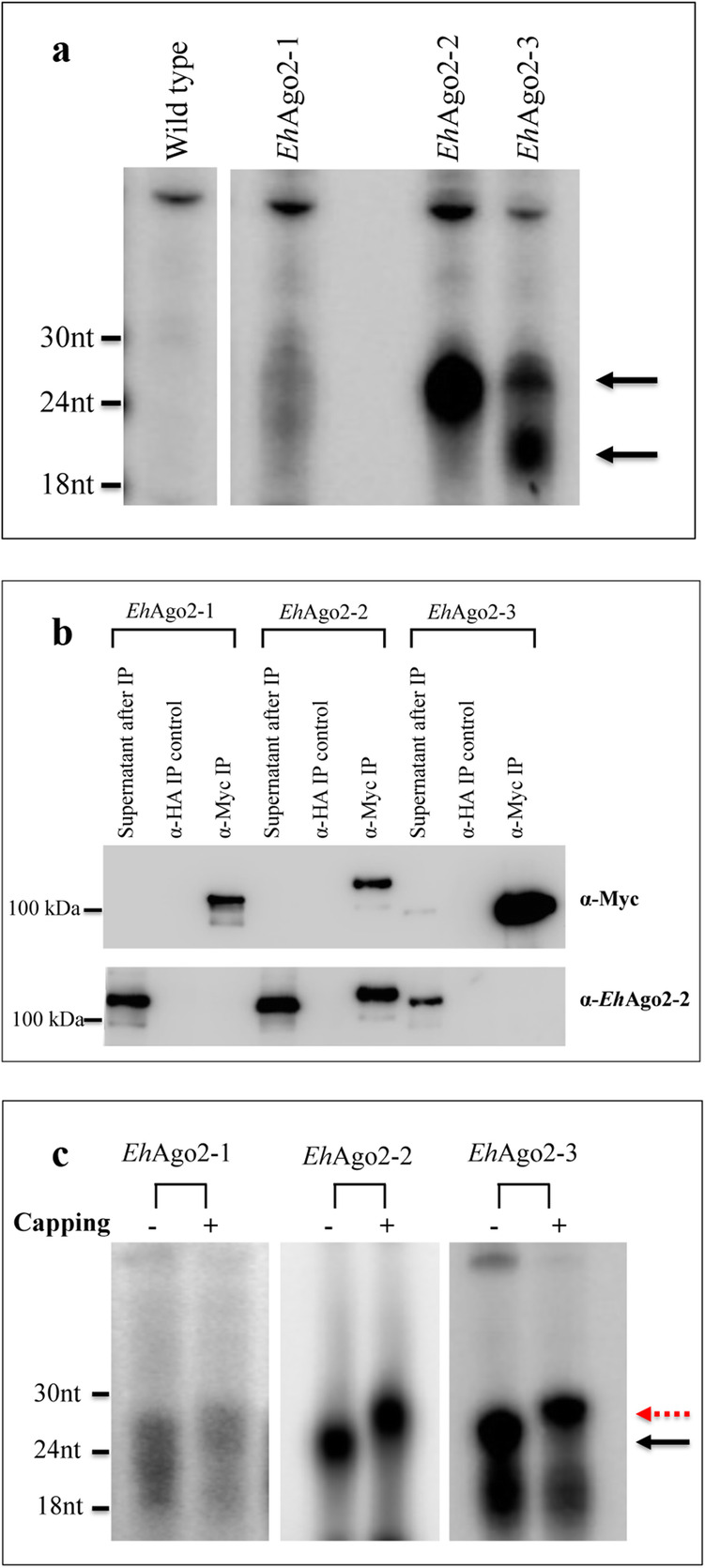

We recently reported that three E. histolytica Ago proteins have distinct subcellular localizations and demonstrated that the PAZ domain of each EhAgo controls sRNA binding [25]. To further characterize the sRNA populations that bind to each EhAgo, we used Myc-tagged EhAgo overexpression lines and performed anti-Myc IP to isolate RNAs associated with each Ago (Fig. 3a). For EhAgo2–2, a distinct 27 nt sRNA population was noted, as has been previously published [23]. For EhAgo2–1, the sRNAs were much less abundant and seen as a faint smear at the 20-30 nt range. For EhAgo2–3, two sRNA populations around sizes 27 nt and 21 nt were observed.

Fig. 3.

All three EhAgos associate with 27 nt sRNAs with 5′-polyP structure. a sRNA populations are bound to all three EhAgo proteins. Total RNA was prepared from anti-Myc IP using lysates from each Myc-tagged EhAgo overexpressing cell line and labeled with α-[32P]-pCp. A faint band ranging from 20 to 30 nt was noted for EhAgo2–1, a distinct 27 nt sRNA band identified for EhAgo2–2, and two sRNA populations at 27 nt and 21 nt was observed for EhAgo2–3. Arrows point to 27 nt and 21 nt sRNA bands. See also Suppl. original blots for Fig. 3a. b Western blot analysis detects a specific Myc signal for each EhAgo IP. Anti-Myc IPs along with control (anti-HA IP) were performed for three Myc-tagged EhAgo overexpressing cell lines. The Myc signal is detected at the expected size for each Myc-tagged EhAgo using anti-Myc antibody, and is absent in the control IP. The same membrane was stripped and re-probed using an anti-EhAgo2–2 antibody. The detected signal is only present in the EhAgo2–2 IP but not in the EhAgo2–1 IP nor EhAgo2–3 IP, showing the specificity of anti-Myc IP experiment. See also Suppl. original blots for Fig. 3b. c Capping assay demonstrates the 5′-polyP structure for the 27 nt sRNA populations. An increase in the sRNA size is observed for all three EhAgo sRNA populations, indicating that they have a 5′-polyP structure. The smaller sized RNAs below 24 nt size in EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo2–3 do not shift in size indicating that they do not have 5′-polyP structure. See also Suppl. original blots for Fig. 3c

We tested the specificity of the anti-Myc IP with additional controls. IP using control beads (anti-HA) showed no signal at the sRNA range when compared with anti-Myc IP for each EhAgo (Suppl. Fig. 4A). We also used Western blot analysis to demonstrate that each EhAgo has a specific Myc signal at the expected sizes which is absent in the control IP (Fig. 3b). The same membrane was stripped and probed using anti-EhAgo2–2 antibody. This demonstrated that the EhAgo2–2 was identified only in the EhAgo2–2 IP but not in the IP of EhAgo2–1 or EhAgo2–3, indicating that each IP is specific without cross-contamination with EhAgo2–2 (Fig. 3b). Of note, EhAgo2–2 is the only protein that is abundant enough to be detected in wildtype cell lysates by Western blot analysis; the other two EhAgos are expressed at low levels, which can only be detected in the overexpressing cell lines. Hence, we could not easily test the other two Ago proteins for cross-contamination [25]. Given that EhAgo2–2 is the most abundant Ago protein in Entamoeba and has the most abundant population of associated sRNAs, the ability to exclude its potential co-IP in EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo2–3 was important. Finally, we demonstrated that the sRNA population bound to each Ago was not affected by various high salt concentrations used in the IP wash (Suppl. Fig. 4B), indicating that each EhAgo binds strongly to the associated sRNA population. Based on these data, we concluded that the sRNA profile shown in Fig. 3a is specific to the given EhAgo protein being studied.

The sRNAs bound to the three EhAgo proteins have 5′-polyP structure

We have previously shown that sRNAs bound to EhAgo2–2 have a 5′-polyP structure [23], a feature similar to the 22G sRNA found in C. elegans and Ascaris [7, 24]. To determine if sRNAs bound to EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo2–3 also have a similar 5′-polyP structure, we performed an RNA capping assay [7, 23]. We show that 27 nt sRNAs associated with both EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo2–3 shifted in size by one nucleotide; however, the smaller size RNAs (18-24 nt) within the same sample were unchanged with the capping assay (Fig. 3c). Overall, the data indicate that 27 nt sRNAs that associate with EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo2–3 have a 5′-polyP structure, whereas the lower size sRNAs do not. In order to define the 5′-structure for the lower sized sRNAs, EhAgo2–3 IP sRNA sample was labeled at the 5′-end using either T4 polynucleotide kinase (PNK) or calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) plus T4 PNK (Suppl. Fig. 4C). The signal for PNK labeling can be seen for the lower sized band but not for the upper 27 nt band. However, as expected, both the upper and the lower bands can be seen by CIP + PNK labeling, indicating that the lower sized sRNAs likely have a 5′-OH structure. Thus, these sRNAs may arise from an RNA degradation process. Our capping assay and 5′-end labeling analysis indicated that the three EhAgos are all loaded with 5′-polyP sRNAs.

Characterization of sRNA populations bound to three EhAgo proteins

For a better understanding of the sRNAs associated with all three EhAgos, we performed high throughput sequencing of sRNA libraries generated from anti-Myc IP RNA samples. The sRNA sequencing libraries were made by a 5′-P independent cloning method using two separate enzymatic treatments (either TAP or RNA 5′-pyrophosphohydrolase (RppH), see Methods). A total of six sRNA libraries (three with each enzyme treatment) were constructed and their sequencing depth of total reads and unique reads is listed in Suppl. Table 1. Our IP sRNA libraries also included an important EhAgo2–2 mutant (EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR). This mutant protein did not alter sRNA binding but caused protein localization to change from the nucleus to the cytoplasm [25].

The overall mapping of sRNAs bound to the three EhAgo proteins is listed in Table 2 (Ago IP libraries based on RppH method) and in Suppl. Table 3 (Ago IP libraries based on TAP method). The percentage of reads that map to tRNA and rRNA are at similar levels among the three EhAgo libraries (0.5–1% for tRNA; 13–19% for rRNA). Of note, the mutant EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR IP library had fewer rRNA reads (3.7%) when compared with the wildtype EhAgo2–2 IP library (13.3%).

Table 2.

Genomic categories that are mapped by sRNA reads by EhAgo IP libraries

| 5′ P-independent cloning, α-Myc IP libraries | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Myc-EhAgo2-1 | Myc-EhAgo2-2 | Myc-EhAgo2-3 | Myc-EhAgo2-2△NLS-DR |

| Total reads | 1,944,425 | 2,298,495 | 1,705,678 | 1,498,720 |

| Unique (unique/total reads) | 419,279 (21.6%) | 599,121 (26.1%) | 241,012 (14.1%) | 391,003 (26.1%) |

| tRNAa,S | 4,407 (1.0%) | 4,944 (0.5%) | 1,919 (0.4%) | 2,028 (0.5%) |

| rRNAa,S | 80,844 (19.3%) | 79,488 (13.3%) | 47,678 (19.8%) | 14,344 (3.7%) |

| EhLINEsa,AS | 41,713 (9.9%) | 15,275 (2.5%) | 16,306 (6.8%) | 41,820 (10.7%) |

| Map to rest of genomea | 230,334 (54.9%) | 388,040 (64.8%) | 139,897 (58.0%) | 282,829 (72.3%) |

| Map to predicted ORFsa,AS | 168,968 (40.3%) | 284,402 (47.5%) | 109,020 (45.2%) | 213,451 (54.6%) |

| Not mapped to genome (%) | 61,981 (14.8%) | 111,374 (18.6%) | 35,212 (14.6%) | 49,982 (12.8%) |

a Number of unique reads divided by total unique reads

S Most reads are in sense orientation

AS Most reads are in antisense orientation

Our sequencing datasets for the three EhAgo sRNA libraries have few reads that mapped to EhSINEs and EREs, however there are substantial sRNA reads that mapped to EhLINEs. Among the three EhAgo proteins, EhAgo2–2 had significantly lower amounts of EhLINE-derived sRNAs (2.5% with EhAgo2–2; 9.9% with EhAgo2–1 and 6.8% with EhAgo2–3) (Table 2). For the mutant EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR, we observed a higher percentage of EhLINEs reads compared to the wildtype EhAgo2–2 (10.7% vs. 2.5%).

The largest category (40%) of reads that mapped to the genome belong to ORFs, indicating the second major source of endogenous sRNAs in Entamoeba are derived from gene coding regions. We categorized the genes to which the sRNAs mapped using both a cutoff (≥ 20 sRNAs map to a gene) and antisense/sense ratio (Antisense (ratio > 2), Mixed (ratio 0.5–2) and Sense (ratio < 2)). As seen in Table 3, the number of ORFs in the Antisense group is the largest among the three categories for all three EhAgo proteins and they overlap by a set of 226 ORFs (additional file 1). Both the TAP and RppH IP libraries rendered very similar results in terms of sRNA mapped genes, indicating the two different sRNA treatments work equally well, and sequencing depth used in this study is sufficient to identify the core ORFs targeted by sRNAs. Our data for all three EhAgo-bound sRNA libraries further demonstrated that genes with antisense sRNAs have very low expression levels and that the distribution of the antisense reads is biased to the 5′-end of genes (Suppl. Fig. 5A and B). Lastly, we used the sequences from EhAgo IP libraries to determine if E. histolytica antisense sRNAs have a “phased” feature. For the secondary sRNAs, “phase” means that they are generated on an RNA precursor transcript in a phased pattern initiated at a specific nucleotide position, with sRNAs starting positions occurring at regular intervals. We checked the first 540 bp region of each ORF for the mapped sRNA reads under a 27 bp window starting from the initiator ATG. The resulting frequency for each position (1–27) was plotted (Suppl Fig. 6). We found no apparent phased register for antisense sRNAs in Entamoeba, indicating that these sRNAs are likely not from Dicer processing.

Table 3.

Antisense sRNAs mapped genes overlap among three EhAgo IP libraries (TAP and RppH) and size-fractionated total RNA libraries (TAP)

| Three categories of genes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense (AS/S < 0.5) | Mixed (AS/S 0.5-2) | Antisense (AS/S >2) | Antisense (overlap among three EhAgos) | |||

| Libraries | ||||||

| α-Myc IP library | RppH | Myc-EhAgo2-1 | 116 | 13 | 319 | 226 |

| Myc-EhAgo2-2 | 178 | 60 | 297 | |||

| Myc-EhAgo2-3 | 81 | 36 | 255 | |||

| Myc-EhAgo2-2△NLS-DR | 73 | 24 | 300 | |||

| TAP | Myc-EhAgo2-1 | 79 | 31 | 324 | 238 | |

| Myc-EhAgo2-2 | 48 | 25 | 298 | |||

| Myc-EhAgo2-3 | 28 | 19 | 256 | |||

| Total RNA | TAP | 15-30nt size fraction | 57 | 68 | 244 | |

| 30-45nt size fraction* | 72 | 52 | 242 | |||

| 30-45nt size fraction with 3' end trimming# | 57 | 24 | 234 | |||

* most mapped reads are in 27nt peak

# most mapped reads are in 31nt peak

On a genome-wide scale, we used the Cuffdiff algorithm [37] to check if there are intragenic regions to which sRNAs from the three EhAgo IP libraries map differentially. This is an approach similar to our genome-wide RNA-Seq study for identifying loci with differential mapping of mRNAs [22, 38]. Pair-wise comparisons among the three EhAgo libraries identified a small number of loci with differential mapping of Ago-associated sRNAs. For example, 64 significant differences out of 2225 loci with mapped sRNAs were identified in the comparison between EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo2–2, and 51 out of 1734 loci were identified in the comparison between EhAgo2–3 and EhAgo2–2. These results again indicate that sRNAs bound to each of the three EhAgos have very similar targets throughout the genome.

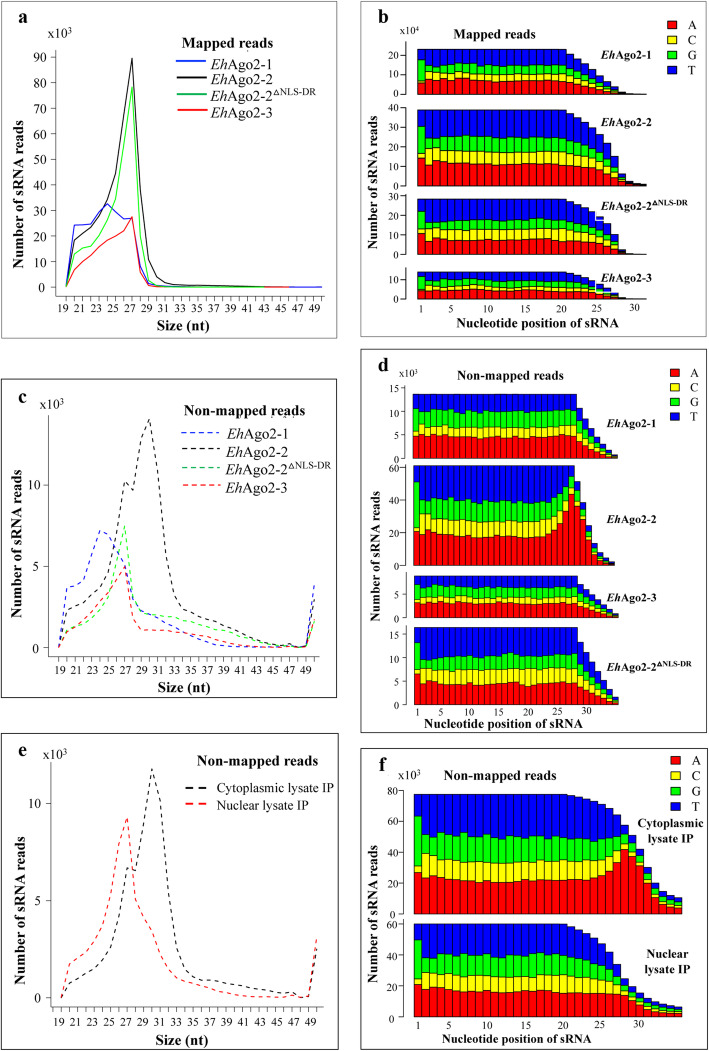

The sRNAs that bind EhAgo proteins are 27 nt in size and have a 5′-G bias

For the three EhAgo-associated sRNA libraries, we determined the size distribution of sRNAs cloned from both the TAP and RppH methods and found that they are similar (Fig. 4a and Suppl Fig. 7A), indicating both enzymatic treatments made no difference in converting these 5′-polyP sRNAs for library cloning. The 27 nt sRNA peak can be seen in all EhAgo libraries, with a sharp 27 nt peak for EhAgo2–2 and EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR. However, smaller size sRNAs are seen in EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo2–3 libraries by both TAP and RppH methods. This matches with the sRNA profile seen on the sRNA gel (Fig. 3a), where the lower sized RNAs have a 5′-OH structure and are likely a degradation product. In addition, we also checked the size distribution of the total reads (non-unique) for each library (Suppl. Fig. 8). There is a prominent peak at 27 nt and a very small peak at 21 nt in the EhAgo2–3 IP library, indicating the smaller 21 nt RNA band was not cloned efficiently (as expected, likely because of their 5′-OH structure).

Fig. 4.

Characterization of sRNA populations bound to three EhAgos. a Size distribution of the mapped reads (unique reads). Three EhAgo IP libraries and EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR IP library were made by RppH method. An sRNA 27 nt peak is observed in all IP libraries. Both EhAgo2–2 and EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR show a sharp 27 nt sRNA peak. EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo2–3 have a broad size distribution in addition to the 27 nt sRNA peak, which matches with the sRNA profile seen by pCp labeling. b Nucleotide distribution analysis for the mapped reads. 5′-G bias is evident for the first nucleotide in the mapped sRNA reads from all EhAgo IP libraries. c Size distribution for the non-mapped reads. It shows a peak at 31 nt only in EhAgo2–2 but not in the other two EhAgos or EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR. d Nucleotide distribution analysis for the non-mapped reads. Non-templated oligo-A tailing is present only in the EhAgo2–2 library not in the others. e Size distribution analysis for the non-mapped reads in nuclear and cytoplasmic EhAgo2–2 IP sRNA libraries. The 31 nt population is seen for cytoplasmic but not the nuclear EhAgo2–2 IP sRNA library. f Nucleotide distribution analysis for the non-mapped reads show oligo-A tailing for cytoplasmic EhAgo2–2 IP sRNA library

As the sRNAs bound to EhAgo2–2 have a G bias in the 5′-nucleotide position [21, 22], we checked the nucleotide composition of sRNAs in the EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo2–3 IP libraries. We plotted nucleotide frequency at each position for each unique sRNA read and found the 5′-G bias again (Fig. 4b and Suppl. Fig. 7B).

For reads in the EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo2–3 libraries, there are significant sRNA reads in the size range of 18-27 nt. We tested to see if the 5′-G bias feature was true for the smaller size sequences in these libraries. We extracted subsets of 23-24 nt and 27 nt reads from the three EhAgo libraries and compared their nucleotide composition (Suppl. Fig. 9). Both subsets show the 5′-G bias feature, indicating that 5′-end of sRNAs likely is intact between the two sampled 23-24 nt and 27 nt subsets. We did further mapping analysis of two subsets (23-24 nt reads against 27 nt reads) using Bowtie and found that the majority of reads in the 23-24 nt subset align perfectly to reads in the 27 nt subset (Suppl. Table 4). This indicates that the smaller reads are likely derived from 27 nt sRNA reads due to the degradation of 27 nt sRNAs at the 3′ end.

In order to determine if the actual sRNA species overlap among the three EhAgo libraries, we performed Bowtie alignment analysis of the EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo2–3 libraries, using EhAgo2–2 dataset as reference. We found that over 70% reads are aligned with reads in the EhAgo2–2 library (Suppl. Table 5), indicating the identities of sRNA pool significantly overlap for the three EhAgos. We also compared EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR with EhAgo2–2, and the overlap for these two libraries is 75%, indicating that the mutation does not affect sRNA binding to this protein. We had previously noted that the EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR can efficiently bind sRNA similar to the wildtype protein [25], and the sequencing now confirms that the EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR mutant does not have an alteration in its associated 27 nt sRNA population.

As an added note, the sequencing libraries for TAP EhAgo IP samples were made several years apart from the RppH EhAgo IP samples. Analysis for both libraries rendered very similar results in terms of sRNA mapping features, size distribution profile, 5′-G bias, and antisense sRNA mapped genes. Based on these data, we concluded that all three EhAgos bind to sRNA populations with significant overlap, mainly targeting retrotransposons and a core set of ~ 226 genes that are silenced in this organism.

A small fraction of EhAgo2–2-bound sRNAs are 31 nt sRNAs

Our sequencing data for the size-selected total RNAs showed that E. histolytica has a second sRNA population with a peak in the size of 31 nt, due to the non-templated additions of 3–4 adenosine(s) at the 3′-end of 27 nt sRNAs. In order to check if this 31 nt population can be associated to any specific EhAgo, we analyzed non-mapped sRNA reads for each of the EhAgo IP libraries. The size distribution of the non-mapped reads showed a 31 nt peak is only present in EhAgo2–2 but not in the other two EhAgo proteins or EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR (Fig. 4c). Additionally, the nucleotide distribution analysis for these non-mapped reads in EhAgo2–2 showed 5′-G bias for the first nucleotide, and a string of 3 or 4 As was identified at the 3′-end (Fig. 4d). These results indicate that EhAgo2–2 is the protein complex site involved in the oligo-adenylation of sRNA in the parasite.

Our previous work showed that cellular localization of EhAgo2–2 is mostly in the nucleus with low levels of protein in the cytoplasm. However, the EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR mutant is excluded from the nucleus [25, 39]. In order to see if oligo-adenylated sRNAs had a different distribution between the cytoplasm and nucleus, we performed cell fractionation for nuclear and cytoplasmic lysates based on previously published methods [40] using both Myc-EhAgo2–2 and Myc-EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR cell lines. The sRNAs isolated from anti-Myc IP samples are shown in Suppl. Fig. 10. As expected, the 27 nt sRNAs were significantly depleted in the nuclear fraction for EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR due to its protein localization to the cytoplasm. In contrast, the 27 nt sRNAs were found at almost equally high levels in both nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions for EhAgo2–2. We sequenced the sRNA libraries made from nuclear and cytoplasmic IP RNA samples. Sequence alignment data are shown in Suppl. Table 6. Both libraries had similar percentages for every mapped genomic category, except that the cytoplasmic IP library had a larger percentage of non-mapped reads (19%) than the nuclear IP library (11.8%) (Suppl. Table 6). The non-mapped reads from both libraries were further analyzed for the size distribution. Figure 4e demonstrates that the 31 nt population is present in EhAgo2–2 cytoplasmic IP but not in the EhAgo2–2 nuclear IP. Figure 4f shows these 31 nt sRNAs have oligo-A tails at the 3′-end by nucleotide distribution analysis.

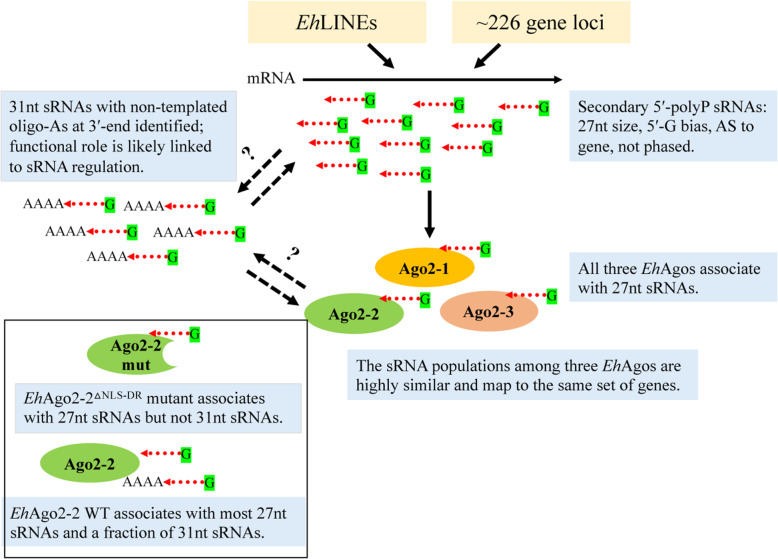

Our sequencing data for both total and Ago-bound RNAs show that E. histolytica has two sRNA populations, and the 31 nt sRNAs are formed from 27 nt sRNAs by oligo-adenylation at the 3′-end. We confirmed the presence of 27 nt and 31 nt sRNA populations for constitutively silenced genes, as well as for the genes that were targeted for the gene silencing using an episomal RNAi-trigger plasmid. All three EhAgos associate with 27 nt sRNAs with mostly overlapping features. Only EhAgo2–2 was found in partial association with 31 nt sRNAs, a process that appears to occur in the cytoplasm. Our finding of sRNA with oligo-adenylation modification is the first report of sRNA modifications among the pathogenic unicellular parasites which contain an RNAi pathway.

Figure 5 summarizes the findings in this study. We see that E. histolytica has abundant 5′-polyP 27 nt sRNAs, with sRNA features consistent with RdRP products (they are 5′-G biased, mostly antisense, and are not phased). The 27 nt sRNAs are loaded into three EhAgo proteins in a non-distinguishable manner. The endogenous sRNAs are mainly derived from EhLINEs and a core set of ~ 226 silenced gene loci. We identified a second sRNA population at 31 nt which is due to the modification of 27 nt sRNAs at the 3′-end with 3 or 4 As; These 31 nt sRNAs are found in partial association with EhAgo2–2 while the intact EhAgo2–2 RISC is in cytoplasm. The functional roles corresponding these non-templated sRNAs await further study.

Fig. 5.

E. histolytica endogenous sRNA populations and their association with EhAgos. E. histolytica has two endogenous sRNA populations: 27 nt and 31 nt sRNAs. Both largely align to either genomic EhLINEs or a core set of 226 silenced gene loci. These sRNAs have features such as 5′-polyP structure, 5′-G bias, antisense to gene, and not-phased. The 31 nt sRNAs differ from 27 nt sRNAs at the 3′-end with addition of non-templated 3 or 4 As. All three EhAgos associate to 27 nt sRNA populations and these sRNAs are largely overlapping. The 31 nt sRNAs are in partial association with EhAgo2–2 but not with other two EhAgos or mutant EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR (shown in the boxed area). The functional role of 31 nt sRNAs is linked to sRNA regulation, but the exact underlying mechanism for its biogenesis or function await further study. Red dotted arrows represent sRNAs (either with or without oligo-A tail). Solid black arrows indicate data supported by sRNA sequencing; dashed black two-way arrows with a question mark indicate possible routes for sRNA modification between two sRNA populations, or between 31 nt sRNAs and the EhAgo2–2-loaded 27 nt sRNAs

Discussion

The RNAi pathway regulates gene expression through Ago proteins and their bound sRNAs. Here, we performed high throughput sRNA sequencing to uncover sRNA species in E. histolytica, focusing on sRNAs that are from size-fractionated total RNA and sRNAs that are associated with the three amebic EhAgo proteins. Our sRNA sequencing data uncovered two sRNA populations in the parasite: 27 nt sRNA with 5′-polyP structure and a 5′-G bias and a second 31 nt sRNA population formed by oligo-adenylation of the 27 nt sRNAs at the 3′-end. We confirmed both populations by Northern blot analysis and showed that the abundance of the two sRNA populations is linked to gene silencing efficacy. The 31 nt sRNA populations are also present in the E. invadens; sequencing of the 31 nt population indicated that they are unchanged during development. While most sRNAs bound to EhAgo2–2 are the 27 nt population, a fraction of sRNA reads belong to 31 nt sRNAs and can be recovered from a sRNA library generated from cytoplasmic but not nuclear fractions. Despite each EhAgo protein having distinct cellular localization, sRNA sequencing data for the three EhAgos demonstrate that they mostly overlap and sRNAs that bind to all three EhAgo proteins largely target retrotransposons and a core set of ~ 226 genes marked for gene silencing.

The sRNA sequencing presented in this study provides a full account of the three EhAgo-bound sRNAs in E. histolytica. We identified a similar pool of sRNAs among all three EhAgos, indicating that the three EhAgos are probably loaded from the same pool of secondary sRNAs (Fig. 5). Differential loading of sRNA populations into different Agos has been reported in several model systems [41, 42]. As demonstrated in Drosophila and Arabidopsis, miRNAs and siRNAs are sorted into specific Ago proteins [43]; the first nucleotide at the 5′-end of the sRNA is used as selective identity for AGO loading: AGO1 has a preference for 5′-uridine, whereas AGO2 and AGO4 prefer 5′-adenosine [44]. C. elegans has 27 Ago proteins; some of these Agos are specific to either primary or secondary sRNAs based on sRNA sizes and 5′-end structures [7, 45, 46]. However, worm-specific WAGOs are semi-redundantly loaded with secondary 5′-polyP 22G sRNAs [47]. The four human Ago proteins mostly bind an overlapping set of sRNAs [48, 49], although some differences in miRNA loading and distribution were recently reported using deep sequencing methods [50, 51]. Our sRNA sequencing results revealed a similar sRNA dataset for three EhAgo proteins indicating a possible redundant function of these proteins for E. histolytica RNAi.

sRNAs are regulated through various modifications: uridylation of siRNAs has been reported across multiple organisms for its degradation role [9]; single adenylation of miRNA has been suggested for a stabilizing function [9, 10]. In yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the addition of non-templated nucleotides (1–2 adenosines or uridines) to the 3′-end leads to sRNA elimination [17]. We observed that the relative abundance of two sRNA populations is indicative as to whether or not the target gene is silenced by an RNAi-trigger plasmid. There are more 27 nt sRNAs relative to 31 nt sRNAs when a target gene is silenced, and vice versa. This may suggest parasites have a way to convert 27 nt sRNAs into oligo-adenylated 31 nt sRNAs; once sRNAs are adenylated, it can leads to their degradation. An alternative possibility could be that the 31 nt sRNA populations might represent the “inactive” sRNAs (not Ago-bound) that could convert to the “active” 27 nt sRNAs (Ago-bound). Further studies to identify the biological conditions and genetic pathways that contribute to sRNA modification and regulation will be important to pursue.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our data provide the first comprehensive dataset of the three E. histolytica Ago-bound sRNA populations. We identified a second population of 31 nt sRNAs that results from non-templated RNA-tailing of the 27 nt sRNA populations with the addition of 3–4 adenosines. The sRNA oligo-adenylation modification event is the first to be discovered among unicellular parasites. Future studies on the functional roles and identification of the protein complexes for oligo-adenylation will provide more insights on the biology of amebic sRNA regulation.

Methods

Parasite culture, plasmids and cell lines

The wildtype E. histolytica trophozoites (HM-1:IMSS) were grown axenically under standard conditions as described previously [23, 52]. Three EhAgo wildtype cell lines for overexpressing N-terminal Myc-tagged protein were constructed as in [25]. Myc-EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR is a mutant cell line of EhAgo2–2 that lacks NLS-DR-rich motif region as reported in [25]. The RNAi-trigger gene silencing plasmids (19 T-EhROM1 (EHI_197460) and 19 T-EhAgo2–2 (EHI_125650)) were made in previous studies [34, 35]. We made new cell lines by transfection of these plasmids in this study. For construction of plasmid 19 T-EHI_136160, the full-length gene of EHI_136160 was amplified from genomic DNA and cloned into the RNAi-trigger gene silencing vector using SmaI and XhoI sites, as reported in [34]. All parasite cell lines were maintained at 6 μg/ml G418. E. invadens strain IP-1 was cultured in LYI-S-2 at 25 °C as previously described [38]. We followed previously published methods for the encystation and excystation [22].

Cell lysis, cytoplasmic and nuclear enriched fractions and IP

The cell lysates were made using either WT parasite cells or transfected parasite cells. The basic lysis buffer contains 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM MgCl2, 10% (v/v) glycerol and 50 mM NaCl. The complete lysis buffer was made by adding basic lysis buffer with IGEPAL CA-630 (equivalent of NP-40) at 0.5% (v/v) plus 1 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF and 1X HALT EDTA free protease inhibitors (Thermo Scientific) and RNase inhibitor (1 unit/ml). The cells were lysed on ice for 15 min, and centrifuged at max speed using a bench top centrifuge at 4 °C for 30 min, and the supernatant was stored at − 80 °C.

Cytoplasmic and nuclear enriched fractions were isolated based on published methods [40, 53] with some changes: three T25 flasks of confluent parasite cells were collected, washed and resuspended in 3 ml of buffer A (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaCl) with protease inhibitors (1 μM leupeptin, 1 μM E-64-d, and 1X HALT protease inhibitor mixture) and incubated on ice for 15 min. IGEPAL was added to a final concentration of 0.5% (v/v), mixed briefly, and centrifuged for 10 min at 2000×g at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and adjusted with NaCl to 150 mM and stored at − 80 °C as the cytoplasmic fraction. For nuclear fraction, the pellet was then washed with 1000 μl of buffer A (without IGEPAL), followed by centrifugation for 10 min at 500×g and 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended in 500 μl of buffer C (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, and 0.5% IGEPAL) supplemented with protease inhibitors and passed through a 27G needle for 5 times to break the nuclei. The samples were centrifuged for 20 min at max speed at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and stored at − 80 °C as the nuclear fraction.

The IP protocol is identical to [25], which is an adaptation from [54]. Both anti-Myc and anti-HA beads (Thermo Scientific) were used for IP experiments. Typically, 20 μl packed beads were used for each IP. A total of 250 μl crude lysate was further diluted with an equal volume of complete lysis buffer giving a protein concentration around 1 μg/μl. The IP mixture was rotated for 2 h at 4 °C. After binding, the beads were washed 6 times at 4 °C (5 min each) using a low stringency wash buffer (the basic lysis buffer plus 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20, 0.1% (v/v) NP-40, 1 mM PMSF and 0.5X HALT EDTA free protease inhibitors). In order to assess the stringency of the protein-sRNA interaction for certain experiments, the last three washes (5 min each) had varied salt concentrations with NaCl at low (50 mM), medium (250 mM), and high (500 mM). After the final wash step, the beads were pelleted at max speed for 1 min at 4 °C, and the beads were used for RNA preparation or eluted for protein Western blot.

RNA isolation, pCp labeling and capping assay

For isolation of RNA from IP experiment, 300 ul of TRIzol (Invitrogen) reagent was added to the final IP beads, and total RNA was isolated using standard protocol. For total RNA/sRNA enriched RNA, we used the mirVana kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The procedures for the capping assay are similar as in [23]. The NEB Vaccinia capping system (New England Biolabs) was used for the capping assay. A reaction volume (20 μl) containing 2 μl of IP RNA or 10 μg sRNA-enriched RNA, 1X capping buffer, 1 μl vaccinia capping enzyme and 1 μl GTP (10 mM) and 1 μl SAM (2 mM). The reaction was incubated for 0.5 h at 37 °C. The capped RNAs were then extracted with acid phenol: chloroform. The radioactive labeling of 3′-end RNA was done by T4 RNA Ligase (New England Biolabs) using α-[32P]-pCp. For radioactive labeling of 5′-end RNA, we used KinaseMax kit (Thermo Scientific), either PNK or CIP + PNK reaction was set up using γ-[32P]-ATP following the manufacturer’s protocol. For the Terminator assay, total RNA (20 μg) was incubated with Terminator enzyme (30 °C for 1 h). A spike-in control (a pre-labeled radioactive 5′-monoP RNA) was included in the reaction as a substrate for Terminator Exonuclease. All RNA samples were resolved on a denaturing 15% polyacrylamide gel (7 M urea) and the radioactive signal was detected using a Phosphor screen and imaged on a Personal Molecular Imager (Bio-Rad).

Northern blot analysis

Northern blot protocol was performed as in [23]. A sRNA-enriched RNA sample (20 μg or 50 μg) was separated on a denaturing 15% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a membrane (Amersham™ Hybond™ -N+ Membrane, GE Healthcare). Probe DNA (Suppl. Table 7) was 5′-end labeled by PNK reaction using γ-[32P]-ATP. The [32P]-labeled DNA probe was then hybridized with membrane in perfectHyb buffer (Sigma) overnight at 37 °C. The membrane was washed using low (2X SSC, 0.1% SDS at 37 °C for 15 min) and medium (1X SSC, 0.1% SDS at 37 °C for 15 min) stringency conditions, and the radioactive signal was detected using a Phosphor screen and imaged on a Personal Molecular Imager (Bio-Rad). The ImageJ program was used for sRNA band quantification.

RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from parasites using TRIzol reagent according to its protocol. The cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA using SuperScript™ IV VILO™ Master Mix kit with ezDNase™ Enzyme (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to its suggested protocol. PCR conditions: one step denaturation: 94 °C for 30 s; 28 cycles: (94 °C for 15 s; 54 °C for 30 s; 72 °C for 60 s); final extension: 72 °C for 5 min. The primers used for RT-PCR can be found in Suppl. Table 7. The ImageJ program was used for PCR bands quantification.

Size fractionation of total RNA

We used 60 μg sRNA-enriched RNA (from WT parasites) for the size fractionation experiments. RNA was loaded onto a denaturing 15% polyacrylamide gel, and separation of RNA was monitored by small RNA ladder. The RNA gel was stained with SYBR gold (Thermo Scientific) and visualized under UV light. The gel sections corresponding to the desired sRNA size range were cut out and minced into small parts for overnight extraction using buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 0.3 M NH4OAc, 0.05% SDS). Extracted RNAs were then precipitated by isopropanol and resuspended in 20 μl water.

Library construction and sequencing

For EhAgo IP libraries, we combined three independent biological samples of anti-Myc IP RNAs for each EhAgo line. For these samples, we constructed sequencing libraries using two separate enzymatic treatments: either TAP (Epicentre, this product was discontinued in 2014) or RppH (NEB). Both TAP and RppH can convert RNA of 5′-polyP into 5′-monoP. The pooled IP RNAs or size-fractionated RNAs were treated under suggested enzyme conditions at 37 °C for 20 min and extracted by acid phenol: chloroform. All RNA libraries were made using the NEBNext multiplex small RNA library prep set for Illumina (NEB#E7300S) following the manufacturer’s protocol. After cDNA generation, we incorporated barcode primers to each library by PCR (10–12 cycles). We quantified samples using Nanodrop and pooled for Illumina sequencing using the MiSeq platform.

The RppH IP libraries for three EhAgos were sequenced more deeply than the TAP IP libraries, with depth of approximately 2 million reads among three EhAgos, which generated approximately two times more unique reads than the TAP IP libraries. We therefore relied on the RppH sequencing libraries for the majority of the analysis presented in the paper. Our IP sRNA libraries included one important EhAgo2–2 mutant (EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR) and EhAgo2–2 widetype nuclear and cytoplasmic IP samples, these samples were made using 5′-P independent cloning method based on RppH treatment. For all size-fractionated total RNA libraries, 5′-P independent cloning method (TAP) were used.

Bioinformatics analysis

We used the same data processing pipelines as described previously [21, 22]. Raw reads were first processed to remove barcodes. We then mapped sequences for the unique reads (processed using Unix uniq command) to E. histolytica tRNA, rDNA, repetitive elements, transcripts and genome using Bowtie v1.2.2 (bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net) with the parameters: -v1 --all. Amebic sequences were obtained from amoebadb.org. The length profile and nucleotide distribution at each position were determined as previously reported [21] using the R package ShortRead [55]. To identify genes targeted by sRNAs, we used ≥ 20 sRNA reads as a cutoff as previously described [22]. For sRNA phasing analysis, we followed the concept used in [56]. Three EhAgo IP libraries were used, the nucleotide position of the start of each antisense sRNA was obtained from Bowtie ORF alignment files. To simplify the question, we checked only the first 540 bp region of each ORF. The frequency of alignment of the first nucleotide of sRNAs to each position was calculated, and a custom R script was used to determine the count of reads at each position within a 27 bp window starting from the ATG. The resulting frequency for each position (1–27) was plotted.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Antisense sRNA mapped genes (226 genes) that overlap among three EhAgo IP libraries. Listed are 226 genes with gene ID and gene annotation. Also listed are three datasheets containing Antisense group genes for each EhAgo IP library: gene ID, antisense sRNA count, sense sRNA count, ratio of AS/S, gene expression in HM1.

Additional file 2: Suppl. Figure 1. Flow-chart of study design and bioinformatics analyses. For size fractionation libraries, total RNA from wildtype E. histolytica trophozoites or E. invadens three time points during development (trophozoite, 72 h encystation, and 8 h excystation) was size-fractioned, and cloned by 5′-P independent cloning method (TAP). For all EhAgo anti-Myc IP libraries, 5′-P independent cloning (either TAP or RppH enzyme treatment) was used to identify sRNA populations associating with each Ago protein. All samples were made following NEB’s sRNA library construction protocol and sequenced by Illumina MiSeq platform. The raw reads were separated by barcodes, and sRNA sequences were processed. Bowtie alignments (−v1) were performed against tRNA, rRNA, retrotransposon elements, the genome and ORFs. Suppl. Figure 2. Analysis of genes mapped with sRNA and sRNA abundance level between two sRNA populations. (A) Number of unique sRNAs mapped to genes from both 27 nt and 31 nt populations are correlated. Counts in log10 scale for 27 nt population in x-axis, counts in log10 scale for 31 nt population in y-axis. (B) The abundance of individual sRNAs in each population is poorly correlated. Although two sRNA populations have significant overlap, the abundance of individual sRNAs cloned in each population differs greatly. The 27 nt sRNA populations are shown in x-axis, 31 nt sRNA populations in y-axis. Both axes are in log10 scale. Suppl. Figure 3. E. invadens 31 nt sRNA populations are not changed during development. (A) Both sRNA populations (27 nt and 31 nt) are present in E. invadens during development. Total RNAs from three time points during development (trophozoite, 72 h encystation, and 8 h excystation) were labeled with α-[32P]-pCp, and separated on a denaturing 15% polyacrylamide gel. Arrows show two sRNA bands at 27 nt and 31 nt. (B) Nucleotide distribution analysis of the non-mapped reads from E. invadens trophozoite dataset. There is a 5′-G bias for the first nucleotide, and a string of 3 or 4 As at 3′-end (all three time-point libraries had a similar pattern, only trophozoite dataset is shown as an example). (C) Venn diagram illustrates that genes mapped at all three time point libraries overlap greatly. After trimming/removal of non-templated oligo-As, sRNA reads can be remapped to the genome. Most genes overlap among all three time-point libraries, indicating that the 31 nt sRNA populations are un-changed during development. Note that the trophozoite dataset is under-sequenced compared to the other two datasets, hence there are fewer mapped genes and all are found in other datasets. Suppl. Figure 4. Verification of specificity of sRNA binding to each of three EhAgos. (A) specific sRNA populations are observed in each EhAgo anti-Myc IP. The IP experiments were performed under the same conditions for both sample and the control using iso-antigenic beads. Anti-HA IP was used as a control and generates no signal at sRNA range demonstrating the specificity of the anti-Myc IP for each EhAgo. (B) The sRNA/Ago binding is unaffected by high salt concentration used in the IP wash. As shown, three NaCl concentrations for IP wash (low, medium, high) were used for anti-Myc IP experiments. Specific sRNA populations bound to each EhAgo can be identified under all wash conditions. (C) 5′-end labeling tests for sRNA populations bound to EhAgo2–3. The IP RNAs for both EhAgo2–2 and EhAgo2–3 were labeled at the 5′-end either by PNK using γ-[32P] ATP, or they were first treated with CIP, then labeled by PNK. For EhAgo2–3, the lower band (20 nt) can be seen by PNK labeling, and also be seen to some degree by CIP + PNK. The upper band (27 nt) can only be seen by CIP + PNK labeling, indicating that the 27 nt sRNAs have 5′-polyP structure, and the lower band (20 nt) is mostly 5′-OH. The EhAgo2–2 IP RNA is shown as a control, which has 27 nt sRNAs with 5′-polyP structure. Suppl. Figure 5. Antisense sRNA mapped genes among three EhAgo IP libraries are silenced in E. histolytica. (A) Boxplot of normalized gene expression for three group genes identified in each of three EhAgo IP libraries. Genes were divided into Antisense, Mixed and Sense groups based on the value of the AS/S sRNA ratio, see Table 3. Expression data were based on microarray data from E. histolytica trophozoites [57]. Gens in both Antisense and Mixed groups have very low expression levels. (B) sRNA distribution within the mapped genes using EhAgo2–2 dataset. This analysis was based on the bowtie transcript alignment files. Unique reads that mapped to ORFs (Table 2, map to predicted ORFs) were assigned a position value based on the position of the starting nucleotide of the aligned sRNA read within each gene. The gene length for each ORF was normalized to one. Histograms for sRNA reads (y-axis) was plotted from 5′ to 3′-end according to their relative position within all genes for each group (x-axis). 5′-bias was noted for sRNAs that are mostly in antisense orientation (shaded as blue), 3′-bias was noted for sRNAs that are mostly in sense orientation (shaded as magenta). Suppl. Figure 6. Antisense sRNAs in three EhAgo IP libraries show no phasing. For each of the three EhAgo IP libraries, the nucleotide position of the start of each AS sRNA was obtained by Bowtie ORF alignment files. For the first 540 bp of each ORF, the frequency of alignment of the beginning of each sRNA to each position was calculated, and a custom R script was used to determine the count of reads at each position within a 27 bp window starting from the initiator ATG. The resulting frequency for each position (1–27) was plotted. Suppl. Figure 7. Size and nucleotide distribution of the mapped unique reads for EhAgo IP libraries (TAP). (A) sRNA size distribution. Similar to EhAgo IP libraries (RppH) in Fig. 4a, EhAgo2–2 shows a sharp 27 nt sRNA peak, but EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo2–3 instead show a broad size distribution below its noticeable 27 nt sRNA peak. (B) Nucleotide distribution for sRNA reads. G bias is evident for the first nucleotide in mapped sRNA reads from all TAP IP libraries. Overall, both TAP and RppH IP libraries had similar results. Suppl. Figure 8. Size distribution of the raw reads for three EhAgo IP libraries (RppH). After barcode removal, raw reads are checked for size distribution, which contains all redundant reads. For EhAgo2–1, reads are broadly distributed at 20-30 nt range with noticeable peaks at 27 nt and 22 nt, which matches its profile seen in Fig. 3a. For EhAgo2–2, a sharp peak at 27 nt matches its profile in Fig. 3a. For EhAgo2–3, it has a sharp peak at 27n, and a much smaller peak at 22 nt. The obvious 20 nt band seen in Fig. 3 a was not efficiently picked up using our small RNA cloning method, further indicating these RNA species do not have 5′-polyP or 5′-monoP structure. Suppl. Figure 9. Comparison of two sampled subset reads: 23-24 nt subset versus the 27 nt subset in three EhAgo IP libraries (RppH). Unique genome mapped reads in Table 2 were sorted into a 23-24 nt subset and 27 nt subset for each EhAgo dataset. (A) The nucleotide distribution for each subset is plotted and show 5′-G bias feature is intact in 23-24 nt subset, indicating that smaller size reads are intact on 5′-end. (B) Bowtie mapping of 23-24 nt subset versus the 27 nt subset show most reads are aligned at position 1, indicating smaller subset reads are likely due to degradation of 27 nt sRNA on its 3′-end. Suppl. Figure 10. sRNA profile for anti-Myc IP RNAs using nuclear and cytoplasmic cell lysates. For EhAgo2–2, the 27 nt sRNAs are almost equally presented between two cell fractions. EhAgo2–2△NLS-DR is used as a control, as it is localized to the cytoplasm, the IP for nuclear lysate brings down few sRNAs. Suppl. Table 1. Summary of all libraries used in the study. Listed are raw and unique reads generated for each library. For EhAgo IP RNA libraries, 5′-P independent cloning method was based on either TAP or RppH enzyme treatment to convert 5′-polyP to 5′-monoP. For size-fractioned RNA libraries, 5′-P independent cloning method was based on TAP treatment. Suppl. Table 2. Genomic mapping for 31 nt sRNA population during E. invadens development. Raw and unique reads from E. invadens three time-points libraries during development (trophozoite, 72 h encystation, and 8 h excystation) were first mapped to genome (these are mostly 27 nt sRNAs carried over during gel separation), and non-mapped reads (mostly 31 nt sRNAs) were trimmed to 27nts and remapped to the genome. Listed are mapped unique reads and percentile for each category. Suppl. Table 3. Genomic categories that are mapped by sRNA for EhAgo IP libraries (TAP). The Bowtie alignments (−v1) were used for mapping to tRNAs, rRNAs and repetitive elements, and genome including ORFs. Listed are mapped unique reads and the percentiles are calculated in parenthesis. Suppl. Table 4. Bowtie analysis of two sampled subset reads, 23-24 nt subset vs. 27 nt subset. For mapped unique reads (Table 2, Map to rest of genome), two subsets were generated based on the size criteria. Numbers of reads aligned between 23 and 24 nt subset vs. 27 nt subset are listed. Over 60% reads in 23–24 subset can be found in 27 nt subset, and most are aligned at position 1, indicating the smaller reads are likely degradation product from 3′-end of 27 nt sRNA. Suppl. Table 5. Bowtie analysis of reads among three EhAgo IP libraries (RppH). We performed Bowtie alignment analysis of the unique reads in the EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo 2–3 libraries, using EhAgo2–2 dataset as reference. Listed are overlap with their percentage. Suppl. Table 6. Genomic categories that are mapped by sRNA for nuclear and cytoplasmic EhAgo2–2 IP libraries. The Bowtie alignments (−v1) were used for mapping to tRNAs, rRNAs and repetitive elements, and genome including ORFs. Listed are mapped unique reads and the percentiles are calculated in parenthesis. Suppl. Table 7. Oligo probes/primers used in this study. Original blot for Fig. 1c and d Original gel/blots used for Fig. 1c and d, refer to the figure legends in Fig. 1c and d. Original blot for Fig. 2a Original Northern blots used for Fig. 2A. ROM1 blots: three samples are loaded (WT, 19 T-LUC, 19 T-ROM1), both WT and 19 T-LUC are used as controls. The blot was first probed with ROM1 probe, which showed antisense sRNA signals of two populations with 27 nt > 31 nt. The blot was stripped and probed for two additional probes that are for endogenous sRNAs from genes EHI_ 164300 and EHI_ 125400, both showed two populations with 27 nt > 31 nt. For simplicity, only WT and 19 T-ROM1 were cropped and used in Fig. 2a. Ago2–2 blots: four samples are loaded (WT, 19 T-537 Ago2–2, 19 T-1064 Ago2–2, 19 T-FL Ago2–2). WT is used as control, three different length of Ago2–2 sequences (from 5′ ATG to the size indicated) were used as trigger. The blot was first probed with Ago2–2 probe, which showed antisense sRNA signals for all three trigger lines, two sRNA populations: 27 nt < 31 nt. The blot was stripped and probed for two additional probes that are for endogenous sRNAs from genes EHI_ 164300 and EHI_ 125400, both showed two populations with 27 nt > 31 nt. For simplicity reason, only WT and 19 T-FL Ago2–2 were cropped and used in Fig. 2a. EHI_136360 blot: three samples are loaded (WT, 19 T-EHI_136360, 19 T-EHI_136380). WT is used as control, two genes as listed were used as trigger. The blot was first probed with EHI_136360 probe, which showed specific antisense sRNA signals for two populations with 27 nt < 31 nt. The blot was stripped and probed for two additional probes that are for endogenous sRNAs from genes EHI_ 164300 and EHI_ 125400; both showed two populations with 27 nt > 31 nt. For simplicity, only WT and 19 T- EHI_136360 were cropped and used in Fig. 2a. Original gel picture for Fig. 2b. Semi-quantitative RT-PCRs using gene specific primers monitor the gene expression level of target gene in RNAi-trigger cell lines and control PCR for EHI_199600 was used as a loading control. For 19 T-EHI_136360, a second control line (19 T-luc) was included. Original blot for Fig. 3. (3A) Original blot, refer to the figure legends in Fig. 3a; (3B) Original Western blots of α-Ago2–2 and α-Myc, refer to the figure legends in Fig. 3b. (3C) Original blot for capping assay. Shown are two capping assay experiments for EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo2–3. Left panel contains IP RNAs from WT, EhAgo2–1, EhAgo2–3 under capping assay conditions. Both EhAgo2–1 and EhAgo2–3 samples showed upward migration of 27 nt sRNAs but not for the control. The 2nd experiment for EhAgo2–3 sample was repeated and shown in Right panel, with clear upward migration of 27 nt sRNAs. Also refer to the figure legends in Fig. 3c. Capping assay for IP RNAs EhAgo2–2 were done on a separate gel as shown. For simplicity, EhAgo2–1, EhAgo2–2, EhAgo2–3 were cropped and used in Fig. 3c.

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of the Singh lab for scientific discussions. We also thank Christopher Yip and Manu Sharma for their critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- RNAi

RNA interference

- sRNA

Small RNA

- Ago

Argonaute

- dsRNA

Double-stranded RNA

- siRNA

Short interfering RNA

- RISC

RNA induced silencing complex

- PTGS/TGS

Posttranscriptional / transcriptional gene silencing

- RdRPs

RNA-dependent RNA polymerases

- miRNAs

MicroRNAs

- piRNAs

Piwi-interacting RNAs

- TAP

Tobacco acid pyrophosphatase

- RppH

RNA 5′-pyrophosphohydrolase

- 5′-polyP

5′-polyphosphate

- PNK

Polynucleotide kinase

- CIP

Calf intestinal phosphatase

- LINEs

Long interspersed nuclear elements

- SINEs

Short interspersed nuclear elements

- EREs

Entamoeba Repeat Elements

- ORF

Open reading frame

- WT

Wild type

Authors’ contributions

The study was conceived and designed by HZ, US. HZ performed experiments, data analysis and drafted the manuscript. GE led and participated in bioinformatics analysis and gave input on the manuscript. NH performed the small RNA sequencing run. US supervised the project and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and accepted the final version of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by funds to U.S. from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI121084).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets of sRNA libraries generated and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. We also deposited all datasets to NCBI GEO (accession GSE157756).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Agrawal N, Dasaradhi PV, Mohmmed A, Malhotra P, Bhatnagar RK, Mukherjee SK. RNA interference: biology, mechanism, and applications. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67(4):657–685. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.657-685.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cerutti H, Casas-Mollano JA. On the origin and functions of RNA-mediated silencing: from protists to man. Curr Genet. 2006;50(2):81–99. doi: 10.1007/s00294-006-0078-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obbard DJ, Gordon KH, Buck AH, Jiggins FM. The evolution of RNAi as a defence against viruses and transposable elements. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 2009;364(1513):99–115. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ketting RF. The many faces of RNAi. Dev Cell. 2011;20(2):148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang C, Ruvkun G. New insights into siRNA amplification and RNAi. RNA Biol. 2012;9(8):1045–1049. doi: 10.4161/rna.21246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vazquez F, Hohn T: Biogenesis and biological activity of secondary siRNAs in plants. Scientifica (Cairo) 2013, 2013:783253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Pak J, Fire A. Distinct populations of primary and secondary effectors during RNAi in C. elegans. Science. 2007;315(5809):241–244. doi: 10.1126/science.1132839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghildiyal M, Zamore PD. Small silencing RNAs: an expanding universe. Nat Rev. 2009;10(2):94–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim YK, Heo I, Kim VN. Modifications of small RNAs and their associated proteins. Cell. 2010;143(5):703–709. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song J, Song J, Mo B, Chen X. Uridylation and adenylation of RNAs. Sci China Life Sci. 2015;58(11):1057–1066. doi: 10.1007/s11427-015-4954-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibrahim F, Rymarquis LA, Kim EJ, Becker J, Balassa E, Green PJ, Cerutti H. Uridylation of mature miRNAs and siRNAs by the MUT68 nucleotidyltransferase promotes their degradation in Chlamydomonas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(8):3906–3911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912632107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heo I, Joo C, Cho J, Ha M, Han J, Kim VN. Lin28 mediates the terminal uridylation of let-7 precursor MicroRNA. Mol Cell. 2008;32(2):276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao Y, Yu Y, Zhai J, Ramachandran V, Dinh TT, Meyers BC, Mo B, Chen X. The Arabidopsis nucleotidyl transferase HESO1 uridylates unmethylated small RNAs to trigger their degradation. Curr Biol. 2012;22(8):689–694. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burroughs AM, Ando Y, de Hoon MJ, Tomaru Y, Nishibu T, Ukekawa R, Funakoshi T, Kurokawa T, Suzuki H, Hayashizaki Y, et al. A comprehensive survey of 3′ animal miRNA modification events and a possible role for 3′ adenylation in modulating miRNA targeting effectiveness. Genome Res. 2010;20(10):1398–1410. doi: 10.1101/gr.106054.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones MR, Quinton LJ, Blahna MT, Neilson JR, Fu S, Ivanov AR, Wolf DA, Mizgerd JP. Zcchc11-dependent uridylation of microRNA directs cytokine expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(9):1157–1163. doi: 10.1038/ncb1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thornton JE, Du P, Jing L, Sjekloca L, Lin S, Grossi E, Sliz P, Zon LI, Gregory RI. Selective microRNA uridylation by Zcchc6 (TUT7) and Zcchc11 (TUT4) Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(18):11777–11791. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pisacane P, Halic M. Tailing and degradation of Argonaute-bound small RNAs protect the genome from uncontrolled RNAi. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15332. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haque R, Mondal D, Kirkpatrick BD, Akther S, Farr BM, Sack RB, Petri WA., Jr Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of acute diarrhea with emphasis on Entamoeba histolytica infections in preschool children in an urban slum of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69(4):398–405. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2003.69.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanley SL., Jr Amoebiasis. Lancet. 2003;361(9362):1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12830-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang H, Alramini H, Tran V, Singh U. Nucleus-localized antisense small RNAs with 5′-polyphosphate termini regulate long term transcriptional gene silencing in Entamoeba histolytica G3 strain. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(52):44467–44479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.278184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H, Ehrenkaufer GM, Hall N, Singh U. Small RNA pyrosequencing in the protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica reveals strain-specific small RNAs that target virulence genes. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]