Abstract

GTP-binding proteins are among the most important enzyme families that are involved in a plethora of biological processes. However, owing to the enormous diversity of the nucleotide-binding protein family, comprehensive analyses of the expression level, structure, activity, and regulatory mechanisms of GTP-binding proteins remain challenging with the use of conventional approaches. The many advances in mass spectrometry (MS) instrumentation and data acquisition methods, together with a variety of enrichment approaches in sample preparation, render MS a powerful tool for the comprehensive characterizations of the activities and expression levels of various GTP-binding proteins. We review herein the recent developments in the application of MS-based techniques, together with general and widely used affinity enrichment approaches, for the proteome-wide and targeted capture, identification and quantification of GTP-binding proteins. The working principles, advantages, and limitations of various strategies for profiling the expression level, activity, post-translational modifications, and interactome of GTP-binding proteins are discussed. It can be envisaged that future applications of MS-based proteomics will lead to a better understanding about the roles of GTP-binding proteins in different biological processes and human diseases.

Keywords: shotgun proteomics, targeted proteomics, GTP-binding proteins, small GTPases, post-translational modifications, activity-based protein profiling

1. Background

1.1. Classification of GTP-binding Proteins

In cells, guanosine mono-, di-, and triphosphates (GMP, GDP, GTP) constitute fundamental building blocks for signal transduction and are therefore central to a broad spectrum of cellular processes. GTP-binding proteins include septins, tubulins, dynamins, eukaryotic translation initiation/elongation factors, small guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) of the Ras superfamily, heterotrimeric G protein α subunit (Gα), etc. By shuffling between the GTP-bound active form and the GDP-bound inactive form, these proteins serve as molecular switches, as such they play essential roles in various cellular processes and diverse signaling networks. Their GTP-bound active conformation allows them to coordinate with effector molecules to confer specific biological responses (Takai, Sasaki et al. 2001).

The hydrolysis of GTP to GDP mediated by large GTPases fuels organelle re-organization, while for small GTPases, the GTP hydrolysis induces protein conformational changes and subsequently the interaction with downstream effectors to transmit extracellular signals. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) are two distinct classes of molecular chaperones that mediate the activities of small GTPases (Bos, Rehmann et al. 2007). In general, GEFs turn on signaling by catalyzing the exchange from GTPase-bound GDP to GTP, whereas GAPs terminate signaling by facilitating GTP hydrolysis (Bos, Rehmann et al. 2007, Cherfils and Zeghouf 2013). For certain small GTPases carrying C-terminal farnesyl or geranylgeranyl modifications, GDP/GTP switch involves alterations in cytosol/membrane localizations and is hence modulated by guanosine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (GDIs) (Cherfils and Zeghouf 2013).

Like other purine nucleotide-binding proteins (e.g. ATP-binding proteins), GTP-binding proteins usually harbor a consensus G1/Walker A motif GXXXXGK(S/T) (‘X’ represents any of the 20 natural amino acids), also referred to as phosphate-binding loop or P-loop (Dever, Glynias et al. 1987). G proteins share other sequence motifs of G2–G5, of which G3/switch II (DXXG) and G4 (N/TKXD) are well conserved and mechanistically important for Mg2+ binding and guanine ring recognition, respectively (Dever, Glynias et al. 1987, Bourne, Sanders et al. 1990, Wuichet and Sogaard-Andersen 2014).

1.2. Small GTPases

Accounting for the largest gene family of monomeric GTP-binding proteins, the human Ras superfamily of small GTPases is comprised of over 150 members (Figure 1), with highly evolutionarily conserved orthologs in Drosophila, C. elegans, S. cerevisiae, S. pombe, and plants (Yang 2002, Colicelli 2004, Wennerberg, Rossman et al. 2005). Based on structural similarities, they can be further classified into five families, Ras, Rho, Rab, Ran, and Arf, as well as the “orphan” or atypical GTPases RhoBTB1/2. The Ras family of GTPases respond to extracellular stimuli to regulate cellular gene expression, proliferation and survival; while the Rho family of GTPases couple the same stimuli to mediate gene expression and cytoskeleton organization (Bar-Sagi and Hall 2000, Jaffe and Hall 2005, Ridley 2006). The Rho family GTPases are also known for their roles in regulating cell shape and plasticity of cell migration (Raftopoulou and Hall 2004). The Rab and Arf families of GTPases control receptor internalization, intracellular vesicular trafficking and actin remodeling (Nielsen, Cheung et al. 2008, Hutagalung and Novick 2011). The Ran protein, the single member of the Ran subfamily, is the most abundant small GTPase in cells and is responsible for microtubule stability and nucleocytoplasmic transport (Sazer 1996).

Figure 1. Phylogenetic relationships and gene structure of the Homo Sapiens small GTPase genes.

The unrooted tree was generated using the MEGA v7.0 software with the full-length amino acid sequences of the Homo Sapiens small GTPase proteins using a Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method, including 1,000 boot-strap replications. All the protein sequences were aligned using ClustalW. The phylogenetic tree was generated using the FigTree v1.4.4 software (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). The five sub-families of small GTPase genes are highlighted with different colored tree branches.

Growing lines of evidence suggest that small GTPases and their regulators (i.e. GAPs and GEFs) may be potential therapeutic targets for treating a wide array of human diseases, including cancer and neurodegenerative diseases (Simanshu, Nissley et al. 2017, Kiral, Kohrs et al. 2018). Aberrant regulation of small GTPase expression has been shown to be involved in various types of cancer, including hepatocellular carcinoma (Rab1B, Rab4B, Rab10, Rab22A, and Rab24), non-small-cell lung carcinoma (Rab14, RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42), pancreatic carcinoma (Rab20, Rac1), colorectal cancer (Rab22A, Rac1B), and prostate cancer (Rab3B) (Recchi and Seabra 2012, Porter, Papaioannou et al. 2016).

Apart from aberrant protein expression, dysregulated activities of GTPase are commonly associated with various types of cancer. For example, K-Ras is the most well-known and frequently mutated Ras isoform observed in pancreatic cancer (70−90%) and colorectal cancer (30−50%) (Fernandez-Medarde and Santos 2011). The major oncogenic mutations in Ras gene can be mapped to amino acid residues G12, G13, and Q61 in the Ras proteins, which reside in the P-loop (residues 10−17) and the switch II (residues 59−76) regions and impair intrinsic and GAP-mediated GTP hydrolysis and aberrant cell signaling (Cox, Hein et al. 2014, Lu, Jang et al. 2016). Given the important functions of these proteins in signal transduction and trafficking, a better mechanistic understanding about their roles in disease development and progression may form the basis for designing strategies for the therapeutic interventions of human diseases.

1.3. Heterotrimeric G Proteins

Heterotrimeric G proteins consist of two functional subunits, an α subunit (Gα) and a tightly associated βγ complex (Gβγ), which play pivotal roles in signal transduction following the activation of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (Neer 1995, Neubig and Siderovski 2002). The Gα proteins, which constitute a family of 20 members, harbor the GTP-binding site and are associated with the βγ complex in its GDP-bound inactive state during the activation/deactivation cycle. Regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins are physiological GAPs of G proteins by stabilizing the transition state of GTP hydrolysis of Gα subunits, thereby stimulating their intrinsic GTPase activity (Siderovski, Hessel et al. 1996). Agonist-receptor binding triggers GDP/GTP exchange, a conformational change of Gα, subunit dissociation from the βγ complex, and ultimately downstream signaling cascades (Bollinger, Stergachis et al. 2016). It has been estimated that ~700 drugs, or approximately 35% of all approved drugs, target GPCRs (Sriram and Insel 2018). Therefore, GPCRs have profound clinical significance and constitute the largest family of protein targets for approved drugs (Sriram and Insel 2018).

1.4. Other GTP-binding Proteins

Tubulins (TUBB family), septins (SEPT family), and dynamins (DLP family), which are encoded by 27, 13 and 3 genes in mammals, respectively, are GTP-binding and membrane-interacting proteins with a highly conserved domain structure. The eukaryotic tubulin superfamily includes five distinct families, i.e. the α-, β-, γ-, δ-, and ϵ-tubulins, and a sixth family (ζ-tubulin) which is present only in Kinetoplastid protozoa (McKean, Vaughan et al. 2001). They are involved in various cellular processes, including cytoskeleton organization, microtubule formation (α and β tubulins), and membrane dynamics (McMurray and Thorner 2009, Schappi, Krbanjevic et al. 2014). Similarly, in eukaryotes, septins have been increasingly recognized as important building blocks in cytoskeletal network by modulating filament formation, cytokinesis and cell morphogenesis (Mostowy and Cossart 2012). Dynamins or dynamin-like proteins (DLPs) are another class of GTPases with important functions in endocytic membrane fission events and cytoskeleton filament network, which rely primarily on GTP hydrolysis-dependent polymerization (Ferguson and De Camilli 2012).

Aside from the above-mentioned GTP-binding proteins, several translational GTPases such as eukaryotic translation initiation/elongation factors (eIFs/eEFs) possess highly conserved GTP-binding pocket yet display distinct GTP hydrolysis rates (Maracci and Rodnina 2016). These small GTPases are involved with ribosome dissociation, codon-anticodon recognition and tRNA translocation (Maracci and Rodnina 2016).

1.5. Mass Spectrometry-based Proteomics Strategies

Proteomics is the global and targeted profiling of proteins in cells, tissues or organisms (Aebersold and Mann 2003). The advent of mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics makes tremendous contributions to the rapid development of methods for global and targeted proteomic profiling of biological samples of high diversity and complexity. In top-down proteomics, MS1 detects the m/z values of the intact protein ions, and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) provides sequence characterizations for large protein fragments, which is suitable for detection of proteoforms and small proteins (Catherman, Skinner et al. 2014). By contrast, bottom-up or shotgun proteomics provides peptide-centric characterizations to further facilitate comprehensive protein identification by analyzing proteolytic digests of a single or mixture of proteins (Zhang, Fonslow et al. 2013). Shotgun proteomics can usually be achieved by data-dependent acquisition (DDA), where the N most abundant peptide precursor ions (N = 3–20) detected in the MS1 survey scans are selected for fragmentation to generate MS/MS (Zhang, Fonslow et al. 2013). As such, the depth of proteome coverage in DDA analysis is largely dependent on sample complexity, which is influenced by background proteome and/or chromatographic separations.

One of the major challenges in shotgun proteomics is the unbiased identification and precise quantification of proteins in highly complex samples. Therefore, to address the growing needs for handling large-scale sample sets of high biological complexity, an emerging strategy termed sequential window acquisition of all theoretical mass spectra (SWATH-MS) on TripleTOF platforms was developed (Gillet, Navarro et al. 2012, Ludwig, Gillet et al. 2018). SWATH-MS is a specific variant of data-independent acquisition (DIA), from which MS/MS of all precursor ions in a given m/z range are continuously acquired in an unbiased fashion (Ludwig, Gillet et al. 2018). DIA is broadly applied for providing deep proteome coverage with accurate and reproducible quantification for large sample sets, and it requires high-confidence spectral libraries and powerful data analysis tools to mitigate the spectral complexity issue (Gillet, Navarro et al. 2012).

Targeted proteomic techniques such as multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM) on triple quadrupole (QQQ) mass spectrometers are routinely used in quantitative proteomics studies. Unlike global proteomic profiling with the conventional shotgun methods, targeted proteomic approach aims to deliver highly reproducible and sensitive measurements of target peptides and thus requires information about the analytes a priori. In the MRM mode, mass filtering of both the precursor and product ions is employed to provide high specificity for the quantification of target peptides, thus affording highly sensitive and reproducible analysis (Lange, Picotti et al. 2008). In contrast, parallel-reaction monitoring (PRM) is a recently developed paradigm for targeted quantitative proteomics typically performed on instruments with high resolution and accurate mass (HRAM) capability, e.g. the hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap or quadrupole time-of-flight mass analyzers (Peterson, Russell et al. 2012, Rauniyar 2015). Several studies showed that PRM and MRM display comparable linearity, dynamic range, precision, and reproducibility for protein quantification (Ronsein, Pamir et al. 2015, Nakamura, Hirayama-Kurogi et al. 2016, Hoffman, Fang et al. 2018). Some studies demonstrated that, leveraging high resolution and trapping capacities, PRM exhibits a wider dynamic range and higher selectivity than MRM (Peterson, Russell et al. 2012, Bourmaud, Gallien et al. 2016).

In this review, we summarize the recent advances in the use of MS-based global or targeted proteomic profiling strategies, along with upstream affinity enrichment, for the proteome-wide identification and quantification of GTP-binding proteins and GTPases, as well as global or targeted profiling of expression, activity, post-translational modifications and nucleotide-dependent interactomes of these proteins.

2. Proteomic studies of GTP-binding proteins

2.1. Chemoproteomic Profiling of GTP-binding Proteins

2.1.1. Activity-based Protein Profiling vs. Resin-based Affinity Capture

In the past decade, activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) has emerged as a growing area of chemical biology in systematic and functional proteomic profiling of distinct enzyme families, allowing for efficient enrichment and robust proteome-wide analysis (Adam, Sorensen et al. 2002, Cravatt, Wright et al. 2008). Structurally the ABPP probes comprise an affinity moiety for downstream enrichment and a chemically reactive group that targets a specific subproteome based on their unique structural or functional attributes (Wang, Tian et al. 2018).

Affinity capture techniques that harness agarose or sepharose beads immobilized with GTP (Sumita, Lo et al. 2016), γ-amino-hexyl-GTP (Jeong, Jang et al. 2018) and m7GTP (Szczepaniak, Zuberek et al. 2012) via γ-phosphate linkage were employed in several studies to enrich specific subsets of GTPases for downstream MS analyses. By introducing a spacer between nucleotides and resins to minimize undesirable hydrophobic interactions and/or to reduce non-specific interactions, these methods display reasonable performances in selective enrichment of GTP-binding proteins. Nevertheless, there are several disadvantages of employing nucleotide-based resins in affinity capture of GTP-binding proteins. First, the enrichment capacity of the resin could be significantly compromised by intrinsic GTPase-mediated hydrolysis of GTP. Second, the affinity of the immobilized GTP analog may differ significantly from that of the free analog, and this depends on resin conjugation sites and the resulting steric hindrance from the beads (Szczepaniak, Zuberek et al. 2012). Third, proteins bound to resins are subsequently eluted with elevated concentrations of GTP, which may lead to bias against those GTPases with slow nucleotide exchange rates and/or low GTP affinity. In order to better mitigate these limitations, numerous structurally similar reactive ABPP probes exploiting GTP or its analogs as scaffolds have been developed in recent years, which facilitated chemical proteomic interrogation of GTPases through active-site labeling.

In ABPP workflow, efficient probe labeling of GTP-binding proteins could be challenging in light of the relatively high intracellular concentrations of guanine nucleotides (~ 0.5 mM GTP, ~ 0.15 mM GDP), and nucleotide-free GTPase is inherently less stable and short-lived in vivo (Traut 1994). Therefore, depletion of endogenous competing guanine nucleotides from cell lysates prior to probe labeling is generally required and can be fulfilled by size exclusion chromatography (Rosenblum, Nomanbhoy et al. 2013). Moreover, given the well-established role of the Mg2+ cofactor in stabilizing nucleotide-bound states, addition of EDTA as a chelating agent was proven effective in drastically promoting GDP-GTP exchange rates (Zhang, Zhang et al. 2000, Korlach, Baird et al. 2004). As a result, probe-labeling can be sensitive toward EDTA-aided nucleotide exchange, raising the possibility that reactive affinity probes could be harnessed to monitor GTPase activities at the proteome-wide level.

2.1.2. Acyl-phosphate GTP Affinity Probes

In recent years, acyl phosphate nucleotide probes have been employed in chemical proteomic profiling of nucleotide-binding proteins. Patricelli et al. and Qiu et al. reported the syntheses, characterizations and applications of acyl nucleotide derivatives for chemoproteomic profiling of nucleotide-binding proteins (Patricelli, Szardenings et al. 2007, Qiu and Wang 2007). The acyl-phosphate adenosine nucleotide affinity probe was synthesized by conjugating ATP or ADP to N-(+)-biotinyl-6-aminohexanoic acid or N-(+)-biotinyl-3-aminopropanoic acid through a mixed anhydride on the terminal phosphate group (Figures 2A–2C). The resulting (+)-biotin-Hex-Acyl-ATP (BHAcATP) or biotin-LC-ATP were characterized by using purified adenosine nucleotide-binding proteins or whole-cell lysates. The working principles of the probe reside in covalent labeling of nucleotide-binding proteins at the Walker A nucleotide-binding motif through a reaction between the lysine (Lys) ε-amino group and the mixed carboxylic phosphoric anhydride moiety of the probe, resulting in amide bond formation and a (+)-biotin-Hex (+339.1616 Da) or (+)-biotin-Prop (+297.1147 Da) tag as variable modifications on the Lys residues. After tryptic digestion, the labeled peptides can be enriched by streptavidin beads for LC–MS/MS analysis. These studies led to selective labeling of at least 75% of the known human protein kinases in native proteomes (Patricelli, Szardenings et al. 2007).

Figure 2. The chemical structures of the ATP-affinity probes.

(A) Biotin-LC-ATP (B) (+)-biotin-Hex-Acyl-ATP (BHAcATP) (C) (+)-biotin-Hex-Acyl-ADP (BHAcADP)

The acyl-phosphate derivatives of GTP have also been developed into the commercially available lysine-reactive desthiobiotin-GTP probes for chemoproteomic interrogation of GTP-binding proteins (ActivX Biosciences, Figure 3A) (Rosenblum, Nomanbhoy et al. 2013). With this probe, a desthiobiotin tag (+196.1212 Da) can be conjugated with the side chain of Lys residue(s) located at the Walker A motif or P-loop of GTP-binding proteins after incubation with native cell lysates. Alternatively, active-site labeling can be monitored at the protein level using immunoblotting analysis (Toriyama, Toriyama et al. 2017). More importantly, ABPP in conjunction with downstream MS detection can be used as a powerful tool for both inhibitor-target binding determination and global profiling of inhibitor targets and off-targets in whole-cell protein lysate. In this vein, the acyl-phosphate GTP affinity probes are advantageous over some existing techniques that monitor GTPase activities by classification of different subfamilies in a high-throughput fashion. Most of these traditional techniques, such as quantitative fluorescence-based approaches, exhibit low-throughput and are time-consuming by virtue of the needs in protein engineering and/or chemical labeling (Korlach, Baird et al. 2004, Nalbant, Hodgson et al. 2004, Pertz, Hodgson et al. 2006, Schwartz, Tessema et al. 2008).

Figure 3. The Chemical structures of GTP acyl nucleotide affinity probes and labeling of GTP-binding proteins with these probes.

(A) The chemical structure of the desthiobiotin-GTP probe; (B) A schematic workflow illustrating the conjugation between the desthiobiotin-GTP probe and a GTP-binding protein; (C) The chemical structure of the desthiobiotin-C3-SGTP structure; (D) Isotope-coded desthiobiotin-C3-GTP probes. ‘H’ and ‘D’ designate hydrogen and deuterium atoms, respectively; (E) A schematic workflow illustrating the conjugation between the desthiobiotin-C3-GTP probe and a GTP-binding protein. Modified from (Xiao, Guo et al. 2013).

The reactive GTP affinity probes, in combination with LC–MS/MS quantification, were pursued to interrogate the GTP-binding proteome and to facilitate inhibitor screening (Lim, Westover et al. 2014). By employing the biotin-conjugated ATP/GTP acyl-phosphate probes (biotin-LC-ATP and biotin-LC-GTP) and a SILAC (stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture)-based quantitative proteomic workflow, Xiao et al. identified 349 ATP-binding proteins and 66 GTP-binding proteins in HL-60 cells (Xiao, Guo et al. 2013). Among them, small GTPases and G subunits were selectively labeled and enriched, and probe concentration-based competition experiments were carried out for systematic comparison of ATP- and GTP-binding affinities of proteins (Xiao, Guo et al. 2013). Similar results were obtained by Hunter et al., who demonstrated the use of desthiobiotin-GTP probe (Figure 3A, ActivX Biosciences) in characterizing SML-8-73-1, an active site inhibitor for the most prevalent oncogenic KRASG12C mutant found in pancreatic and colorectal tumors, and quantified over 100 GTP-binding proteins in MIA PaCa cell lysates. However, GTP and GDP bind to Ras proteins with sub-nanomolar affinity, and due to the gel filtration step preceding inhibitor incubation, the effective inhibition and efficient competition of the inhibitor with millimolar intracellular concentrations of endogenous guanine nucleotides need to be addressed by other assays (Hunter, Gurbani et al. 2014). In a later study, Okerberg et al. found that acyl phosphates of ATP (ATPAc, Ac = desthiobiotinyl) and GTP (GTPAc) were both effective in labelling known nucleotide binding sites via specific acylation of the conserved Lys residues (Okerberg, Dagbay et al. 2019). They also indicated that desthiobiotin displays superior properties in capture by and release from streptavidin beads compared to biotin. It is also worth noting that a comparison of the biotin- and desthiobiotin-conjugated probes did not yield a substantial difference. That being said, desthiobiotin tends to display higher chemical stability during post-labeling procedures, where in some instances biotin sulfoxide formation was observed as possible oxidation product of biotin during sample preparation (Villamor, Kaschani et al. 2013).

Bearing structural similarity to GTP, 6-thioguanosine triphosphate (SGTP), a metabolite of thiopurine drugs, can competitively block Rho-GEF binding and be incorporated into RNA (Poppe, Tiede et al. 2006). To systematically characterize cellular proteins that recognize SGTP at the whole proteome level, Xiao et al. devised a similar strategy by utilizing 6-thioguanosine triphosphate (SGTP) acyl-phosphate probe (desthiobiotin-C3-SGTP, Figure 3C) together with SILAC (Xiao, Ji et al. 2014). The method facilitated the identification of 165 putative SGTP-binding proteins with known GTP-binding gene ontology (GO) functions in Jurkat-T cell lysates (Xiao, Ji et al. 2014). It is of note that competitive labelings with SGTP vs. GTP probes, as well as with the SGTP probe at low (10 μM) and high (100 μM) concentrations, were employed for identifying proteins with selective binding to SGTP.

Very recently, Cai et al. developed a refined workflow by coupling the use of isotope-coded desthiobiotin-GTP acyl-phosphate probes (desthiobiotin-C3-GTP) with MRM analysis, which led to highly sensitive and reproducible quantification of 97 GTP-binding proteins in the SW480/SW620 pair of primary/metastatic colorectal cancer cells (Cai, Huang et al. 2018). The structures of these isotope-coded GTP affinity probes differ in the introduction of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) as a linker to increase the distance between GTP and the affinity handle (Figure 3D), thereby modifying the target proteins with a variable lysine conjugate of desthiobiotin-C3-L (+281.1740 Da) or desthiobiotin-C3-H (+287.2208 Da) (Figure 3E) (Cai, Huang et al. 2018). To facilitate MRM analysis, a Skyline spectral library that encompassed 605 tryptic peptides derived from 217 GTP-binding proteins was constructed, providing a valuable resource for studying GTP-binding subproteome. Among the 97 quantified GTP-binding proteins, more than 20 exhibited differential expression by at least 1.75-fold in paired metastatic and primary cancer cells. The applications of isotope-coded nucleotide affinity probes in studying other nucleotide-binding proteins such as ATP-binding proteins and kinases with the use of desthiobiotin-C3-ATP probes were also reported (Xiao, Guo et al. 2013, Guo, Xiao et al. 2014, Miao, Xiao et al. 2016). It is also noteworthy that this approach is readily applicable for the quantification of nucleotide-binding proteins in clinical samples (e.g., biological fluids and tissues), which are generally not amenable to metabolic labeling.

2.1.3. Photoreactive GTP Affinity Probes

Another type of GTP-derivatized affinity probe relies on photoaffinity labeling (PAL) that facilitates photoirradiation-induced covalent modifications of GTP-binding proteins at the nucleotide-binding pockets. A typical design of such photoaffinity probes contains an ultraviolet (UV) light-activated photocross-linking moiety and an enrichment handle such as biotin (Thomas, Brittain et al. 2017). Upon UV irradiation, a highly reactive intermediate is produced, followed by irreversible reaction of the probe with its protein targets; downstream capturing of probe-labeled proteins can then be facilitated by the enrichment moiety. The photoaffinity probes have been widely exploited in studying ligand-protein interactions and are applicable to whole-cell lysates or live cells in culture.

Kaneda et al. first demonstrated simple and efficient photoaffinity-based proteomic profiling of GTP-binding proteins (Kaneda, Masuda et al. 2007). The design of the probe features the incorporation of a diazirine moiety, the smallest photoreactive group that forms a reactive carbene upon UV irradiation (Figure 4A). Compared to many azido-GTP derivatives that are chemically labile under reduced conditions and not ideal for proteomic analysis, this probe allowed for photoaffinity cross-linking, subsequent tagging by the cleavable P-S bond, and chelation of GTP-binding proteins using Fe(III)-IMAC (immobilized metal affinity chromatography) mechanisms (Figure 4A) (Kaneda, Masuda et al. 2007). It was demonstrated that the diazirine-based PAL-GTP probe allows for the labeling and enrichment of a model GTP-binding protein, H-Ras (from the Ras superfamily of small GTPases).

Figure 4. Chemical structures of photoaffinity labeling (PAL)-GTP probes.

(A) The chemical structure and mechanisms of the multi-functional diazirine-based PAL-GTP probe. IMAC: immobilized metal affinity chromatography; (B) The chemical structure of GTP-2′−3′-diol-BP-yne; (C) The chemical structure of GTP-2′−3′-carbonate-BP-yne; (D) Conjugation of biotin tag via Cu(I)-catalyzed click-chemistry reaction. CuAAc: Cu(I)-catalyzed azide/alkyne cycloaddition; (E) BP-yne control. Modified from (Kaneda, Masuda et al. 2007, George Cisar, Nguyen et al. 2013).

Another example in this category is the GTP-BP-yne probe synthesized and characterized by George Cisar et al., where a benzophenone moiety was selected as a photoactivatable cross-linker while a bioorthogonal alkyne tag was employed as a click-chemistry handle for enrichment (Figures 4B, 4C) (George Cisar, Nguyen et al. 2013). A highly specific ‘click’ reaction, the Cu(I)-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), can effectively biotinylate the substrate proteins to enable downstream affinity purification with streptavidin beads and LC–MS/MS analysis (Figure 4D) (Dubinsky, Krom et al. 2012). They further described a strategy that combines PAL with multi-dimensional protein identification technology (MudPIT), which facilitated active-site labeling of more than 30 annotated GTP-binding proteins in lysate of HEK293 cells, including small GTPases and GTP1/OBG family. Their results also provided additional evidence for the flexibility of enzyme active-site labeling that does not require strict purine nucleotide selectivity. Two control probes were incorporated to reduce false-positive hits arising from non-specific binding: (1) excess GTP was added to compete away specific probe-protein interactions and (2) BP-yne (Figure 4E) was used as a control compound to identify any targets that were labeled arising from interaction with the non-nucleotide portion of the probe or due merely to high abundance of the target. Notably, ATP-binding proteins (26% among all hits), purine nucleotide-binding proteins and those without known GTP-binding annotation were also identified using this approach, which indicated a relatively high cross-reactivity of the probe as compared to the aforementioned acyl-phosphate probe (Patricelli, Szardenings et al. 2007, George Cisar, Nguyen et al. 2013).

2.1.4. Expanding the Designs of GTP Affinity Probes Using Inhibitor Structures

The concept of kinobeads was introduced in 2007 as a platform for profiling ATP-competitive small-molecule kinase inhibitors by coupling to ABPP-based chemical proteomic approaches (Bantscheff, Eberhard et al. 2007). Kinobeads are essentially sepharose beads immobilized with a set of broad-spectrum, ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors and can be used in affinity enrichment of kinases and other ATP-binding proteins. In light of the design of kinobeads, the chemistry of GTP affinity probes can be further extended to newly discovered GTPase inhibitors (Golkowski, Vidadala et al. 2017). Given the importance and high prevalence of KRAS oncogenic mutations in pancreatic and colorectal tumors, K-Ras inhibitors have been widely exploited as drug candidates (Lu, Jang et al. 2016). Lim et al. reported the synthesis of a GDP analogue, SML-8-73-1 (Figure 5A), and the prodrug derivatives, SML-10-57-1 (Figure 5B) and SML-10-70-1 (Figure 5C), which are selective, direct-acting covalent inhibitors of the KRASG12C mutant over wild-type (WT) Ras (Lim, Westover et al. 2014, Xiong, Lu et al. 2017).

Figure 5. The chemical structures of various GTPase inhibitors and reacting GTP analogues.

Shown are the structures of KRAS inhibitors SML-8-73-1 (A), SML-10-57-1 (B), and SML-10-70-1 (C); the structures of dynamin inhibitor Bis-T (D) and tubulin inhibitor CID 1067700 (E), N2-acryl-GTP (F) and N2-acryl-GppNHp (G). Modified from (Odell, Chau et al. 2009, Lim, Westover et al. 2014, Hong, Guo et al. 2015, Wiegandt, Vieweg et al. 2015)

In a related study, Odell et al. conjugated bis-tyrphostin (Bis-T, Figure 5D), a potent inhibitor of the phospholipid-stimulated GTPase activity of dynamin I, with diazirine and employed it for probing the ligand-binding site of dynamin I (Odell, Chau et al. 2009). In addition, Hong et al. reported that CID1067700 is a competitive inhibitor for nucleotide binding for multiple GTPases, including Rho, Ras and Rab small GTPases (Figure 5E) (Hong, Guo et al. 2015). Wiegandt et al. synthesized a series of reactive acryl derivatives of guanosine nucleotides, including N2-acryl-GTP (referred to as aGTP, Figure 5F) and N2-acryl-GppNHp (referred to as aGppNHp; Figure 5G), that are able to react covalently with strategically placed cysteines in GTPases to irreversibly lock them into their functional states (Wiegandt, Vieweg et al. 2015). These structures may facilitate the development of novel multiplexed inhibitor beads for more specific enrichment of the GTP-binding proteome.

2.2. Targeted Proteomic Profiling Coupled with Gel Electrophoresis

In addition to small-molecule probes, other profiling techniques take advantage of the distinct molecular weight distributions (15–37 kDa) of small GTPases for their enrichment prior to MS analyses. The whole-cell or tissue protein lysates can be first fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) prior to tryptic digestion to reduce sample complexity. Halvey et al. made the first attempt on the use of gel electrophoresis (Ge) coupled with LC–MRM (GeLC–MRM) to quantify mutant K-Ras variants in complex biological samples (Halvey, Ferrone et al. 2012). This method enabled robust and sensitive quantitation of K-Ras in DKs-8 and DKO-1 cells by choosing P-loop peptides unique to KRASWT (LVVVGAGGVGK) and KRASG13D (LVVVGAGDVGK). In a follow-up study, Beckler et al. quantified mutant and WT forms of K-Ras in exosomes isolated from mutant K-Ras-expressing DKO-1 cells (Beckler, Higginbotham et al. 2013). Moreover, global proteomic profiling by LC–MS/MS uncovered a number of exosomal proteins that are potentially regulated by mutant K-Ras.

Zhang et al. later described the development and application of a novel multiplexed assay for quantifying the activities of small GTPases, and the method involves effector pull-down and GeLC–MRM analysis (Zhang, Li et al. 2015). In particular, four Ras-binding domains (RBDs), including GST-Raf1-RBD (Ras isoforms), GST-Rhotekin-RBD (Rho isoforms), GST-PAK1-RBD (Rac isoforms and Cdc42) and GST-RalGDS-RBD (Rap isoforms), were employed for immunoprecipitation. Proteins were subsequently resolved on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel, and the 15−25 kDa region of the gel that contains the targeted small GTPases was excised and subjected to in-gel tryptic digestion and LC-MS/MS analysis. With the use of the heavy isotope-labeled peptides as standards, they were able to detect simultaneously 12 active small GTPases.

Large clostridial toxins (LCTs) such as TcdA and TcdB can trigger inflammasome activation, which may be positively regulated by glucosylation of small GTPases (Johnson and Chen 2012). With the development of a multiplexed and scheduled GeLC–MRM assay, Junemann et al. quantified LCT-induced mono-O-glucosylation levels of Rho and Ras small GTPases (Junemann, Lammerhirt et al. 2017). They further performed a proof-of-concept study by analyzing TcdA-induced glucosylation of GTPases to define the in vivo substrate specificity of LCTs, and by measuring glucosylation kinetics of RhoA/B, RhoC, RhoG, Ral, Rap1, Rap2, (H-/K-/N-)Ras, and R-Ras2 (Junemann, Lammerhirt et al. 2017). The heavy stable isotope-labeled protein internal standard was spiked into unlabeled samples and the extracted proteins were resolved on a 15% SDS-PAGE gel and the gel region of 15–25 kDa containing small GTPases was excised and digested in-gel with trypsin or chymotrypsin to generate proteolytic peptides (unmodified/glucosylated) for multiplexed MRM analysis. In total, 134 (for tryptic digestion) and 96 (for chymotryptic digestion) transitions from eight small GTPases were monitored in two scheduled LC–MRM runs (Junemann, Lammerhirt et al. 2017). Together, the substrate profiles of the three LCTs (TcdA, TcdB and TcsL) in Caco-2 cells were interrogated, and it was found that (H-/K-/N-)Ras and Rap(1/2) could be glucosylated by TcsL and TcdA, but not TcdB (Genth, Junemann et al. 2018).

On the basis of the aforementioned enrichment concept that exploits gel-based fractionation to reduce sample complexity, a novel targeted proteomic workflow was later established for high-throughput quantitative profiling of small GTPases (Huang, Qi et al. 2018). In brief, the method involves metabolic labeling using SILAC, enrichment of low-molecular-weight (15–37 kDa) small GTPases by SDS-PAGE, and scheduled LC–MS/MS analysis in the MRM mode. Owing to the substantially reduced complexity of the proteome emanating from SDS-PAGE fractionation, the method allows for reliable and high-throughput quantification of small GTPases of the Ras superfamily with relatively low protein inputs (5–100 μg) and without the need for chemoaffinity or immunoaffinity enrichment. The Skyline spectral library contained 432 distinct peptides representing 113 small GTPases encoded by unique genes. It is worth noting that all the 2686 targeted transitions monitored for each light-/heavy-isotope-coded peptide can be monitored in two LC runs by using scheduled MRM with a 6-min retention time duration (Escher, Reiter et al. 2012, Huang, Qi et al. 2018).

This method was further employed to examine the differences in abundance of small GTPase proteins in paired primary/metastatic melanoma cells: WM-115/WM-266–4, IGR39/IGR37 and WM793/1205Lu. Taking advantage of both the effective enrichment of small GTPases by gel-based fractionation and the analytical robustness of the scheduled MRM analysis, over 90 small GTPases were robustly quantified. This comparative targeted proteomic interrogation unveiled a substantial reprogrammed small GTPase expression profile during melanoma metastasis and led to the discovery of a previously unrecognized role of Rab38 in promoting melanoma metastasis through regulating matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 (Huang, Qi et al. 2018). Furthermore, by comparing the same samples analyzed by DDA and MRM methods, we found that the LC–MRM method outperformed the shotgun proteomic method in reproducibility and sensitivity. By harnessing the same targeted proteomic workflow, we also explored the roles of small GTPases associated with acquired resistance to tamoxifen in estrogen-receptor (ER)-positive MCF-7 breast cancer cells (Huang and Wang 2018) and metastatic transformation of colorectal cancer cells (Huang and Wang 2019).

More recently, we established a novel targeted quantitative proteomic assay adapted from the SILAC-based GeLC–MRM assay for high-throughput profiling of small GTPases in brain tissues of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients (Huang, Darvas et al. 2019). The scheduled GeLC–MRM assay involves the use of stable isotope-labeled (SIL) peptides that facilitate robust quantification of more than 80 small GTPases from tissue samples in a single LC–MRM run, with excellent throughput and reproducibility. Interestingly, the levels of RAB3A, RAB3D, and RAB27B proteins, which are involved with synaptic and secretory vesicles, were found to increase in brain tissue samples with elevated disease severity (Huang, Darvas et al. 2019). More recently, the application of GeLC–MRM assay facilitated by SIL peptides was extended to investigating the differential protein expression of small GTPases during adipogenesis in cultured murine cells, where a panel of small GTPases were down-regulated and Rab32 was found to play a previously unidentified role in inhibiting adipocytic differentiation (Yang, Huang et al. 2020). Collectively, these studies demonstrated the robustness of the adapted GeLC–MRM quantitative proteomic workflow in high-throughput interrogation of small GTPase proteome in mammalian cells and tissues.

Taking advantage of the distinct molecular weight distribution of heterotrimeric G protein subunits, similar enrichment strategy was also implemented in recent studies of G protein-mediated presynaptic signaling, where an MRM-based quantitative proteomic method was developed and applied for analyzing neuronal Gβ and Gγ subunits (Yim, McDonald et al. 2017, Yim, Betke et al. 2019). Based on their distinct molecular masses, Gβ and Gγ subunits were readily resolved by SDS-PAGE and subsequently digested in-gel with trypsin and analyzed by MRM using surrogate proteotypic peptides. Generally speaking, gel-based approach represents an orthogonal separation strategy to resolve background proteome complexity and has proven to be a simply yet efficient method to facilitate targeted MS analysis of a subset of GTP-binding proteins.

2.3. Targeted Proteomic Profiling Coupled with Effector Domain Pull-Down

With growing interest and advances in developing selective and covalent Ras inhibitors for therapeutic applications, targeted MS has been extensively employed in assessing Ras activation kinetics and inhibition efficiency. For example, Patricelli et al. and Lito et al. harnessed a combined Raf-RBD capture strategy and MRM-based assay to measure covalent target engagement by quantifying mutant-specific peptide derived from KRASG12C (LVVVGAGCVGK) upon treatment with Ras inhibitors ARS-107 and ARS-853 (Lito, Solomon et al. 2016, Patricelli, Janes et al. 2016). In recent investigations of covalent Ras inhibitors ARS-1620 (Janes, Zhang et al. 2018) and AMG 510 (Canon, Rex et al. 2019, Lanman, Allen et al. 2020), the same strategy was exploited by combining Ras effector domain pull-down with MRM quantification to ensure high sensitivity and specificity. Moreover, pull-down assays incorporating various types of RBDs were successfully employed for the isolation of active forms of up to 12 small GTPases prior to targeted MS analyses in the MRM mode, as discussed above (Zhang, Li et al. 2015).

2.4. Global Proteomic Profiling the Interactome of GTP-binding Proteins

2.4.1. Affinity Purification-Mass Spectrometry (AP–MS) for Small GTPase Analyses

Small GTPases play fundamental roles in cell proliferation/differentiation, cytoskeleton organization and membrane trafficking, and many of them engage in protein-protein interactions with upstream regulators and downstream effectors to execute proper biological functions (Cherfils and Zeghouf 2013). Hence, tremendous efforts have been devoted to identifying interacting partners of small GTPases, including their GEFs, GAPs and effectors. Among the existing techniques, AP–MS has been widely explored, with immune-enrichment coupled with quantitative MS analysis being the method of choice for high-throughput assessment of protein complexes and protein-protein interactions. For instance, Koch et al. described the use of nucleotide-free GTPases as baits for pull-down experiments and AP–MS analysis to identify unknown GEFs for a given small GTPase (Figure 6A) (Koch, Rai et al. 2016). Endogenous GMP, GDP and GTP were degraded via the reaction with alkaline phosphatase to ensure formation of stable GTPase-GEF complex. The Rab GTPase Sec4 was first biotinylated using the commercially available EZ-Link™ Maleimide-PEG2-Biotin and immobilized on streptavidin magnetic beads, and AP–MS results showed enrichment of its GEF, i.e. Sec2, in the subsequent pull-down experiments with GTP elution (Koch, Rai et al. 2016).

Figure 6. Schematic diagrams of AP–MS workflows for interrogating the interactomes of GTP-binding proteins.

(A) Enrichment of GEF proteins from biological samples based on the high-affinity binding of GEFs to nucleotide-free GTPases. Modified from (Koch, Rai et al. 2016); (B) Quantitative GTPase affinity purification (qGAP) assay for the systematic identification of interaction partners of Rho GTPases. Modified from (Paul, Zauber et al. 2017); (C) SILAC-based quantitative AP–MS workflow for the characterizations of the comparative and nucleotide-dependent (KRASWT/KRASG12D) interactomes of two K-Ras isoforms, KRas4a and KRas4b. Modified from (Zhang, Cao et al. 2018)

Paul et al. developed a quantitative GTPase affinity purification (qGAP) assay to identify systematically interaction partners of three prototypical Rho GTPases (Cdc42, Rac1, RhoA) and three additional Rho GTPases (RhoB, RhoC, RhoD) expressed as fusion proteins with glutathione S-transferase (GST) (Figure 6B) (Paul, Zauber et al. 2017). By coupling affinity pull-down and SILAC-based quantitative proteomics (for cultured cells) or label-free quantitation (for tissue samples), they identified novel effector proteins for the small GTPases that are dependent on their nucleotide loading state (Figure 6B). Similarly, by utilizing SILAC-based quantitative AP–MS methods, Zhang et al. interrogated the comparative and nucleotide-dependent (KRASWT/KRASG12D) interactomes of two K-Ras isoforms, KRas4a and KRas4b, suggesting previously unrecognized differential biological functions of the two isoforms, e.g. preferential KRas4a-Raf1 binding and the relevant signaling axis (Figure 6C) (Zhang, Cao et al. 2018).

To systematically identify Rab effectors in Drosophila melanogaster, a comprehensive set of 23 Drosophila Rabs that have at least one mammalian ortholog was chosen for AP–MS to identify the proteins bound to each recombinant Rab protein with the Q/L mutation to stabilize the GTP-bound form (Gillingham, Sinka et al. 2014). Over 25 interactions for 10 Drosophila Rabs were subsequently validated by yeast two-hybrid screening and in vitro binding (Gillingham, Sinka et al. 2014).

2.4.2. AP–MS for GEFs/GAPs

Known putative GAP and GEF proteins can also be used as baits in AP–MS to identify their substrate GTPases. Ke et al. utilized potential effector proteins of small GTPases as baits to identify small GTPases as potential interactors or substrates of the candidate GAP/GEF proteins (Ke, Lin et al. 2018). By coupling immunoprecipitation with LC–MS/MS analysis, Wilkinson et al. determined the interactomes of three GAP/GEF proteins at the postsynaptic density (PSD) signaling machinery of adult mouse cortex, i.e. the RasGAP Syngap1, the ArfGAP Agap2, and the RhoGEF Kalirin, where 280 interactions were identified (Wilkinson, Li et al. 2017).

2.4.3. AP–MS for Other GTP-binding Proteins

The central GTPase domain plays an essential role in mediating septin-septin interactions (Nakahira, Macedo et al. 2010). Renz et al. carried out a systematic screening for cell cycle-specific septin interactors by means of cell synchronization coupled with SILAC-based quantitative AP–MS workflow, resulting in the discovery of a total of 83 interaction partners in yeast cells (Renz, Oeljeklaus et al. 2016). Hecht et al. also exploited SILAC-AP–MS to examine the interaction network of SEPT9 in immortalized 1306 skin fibroblast cells and identified SEPT2, SEPT7, SEPT8 and SEPT11 in the interactome (Hecht, Rosler et al. 2019).

2.4.4. In vivo Proximity-dependent Biotinylation

To determine effectively neighboring interaction partners in live cells, BioID exploits the application of a promiscuous biotin ligase from Escherichia coli (BirA*) or an engineered peroxidase (APEX) fused to a bait that biotinylates proteins in close proximity (Roux, Kim et al. 2012). The resulting biotinylated interacting or proximal partners can be isolated with streptavidin beads and analyzed by LC–MS/MS following in-gel tryptic digestion (Roux, Kim et al. 2012, Rhee, Zou et al. 2013). Gillingham et al. adapted BioID to identify effectors and regulators of ectopically relocated mitochondrial forms of 11 human Rab GTPases, which led to the discovery of many known effectors and GAPs as well as candidate novel effectors (Gillingham, Bertram et al. 2019). Due to the occurrence of biotin labeling under physiological conditions, prospective effectors can be captured while using stringent washing conditions. The application of BioID with the GDP-locked form of the Rab GTPases, nonetheless, requires high conformational stability and tight binding with GEF in the nucleotide-free state to enable sensitive detection.

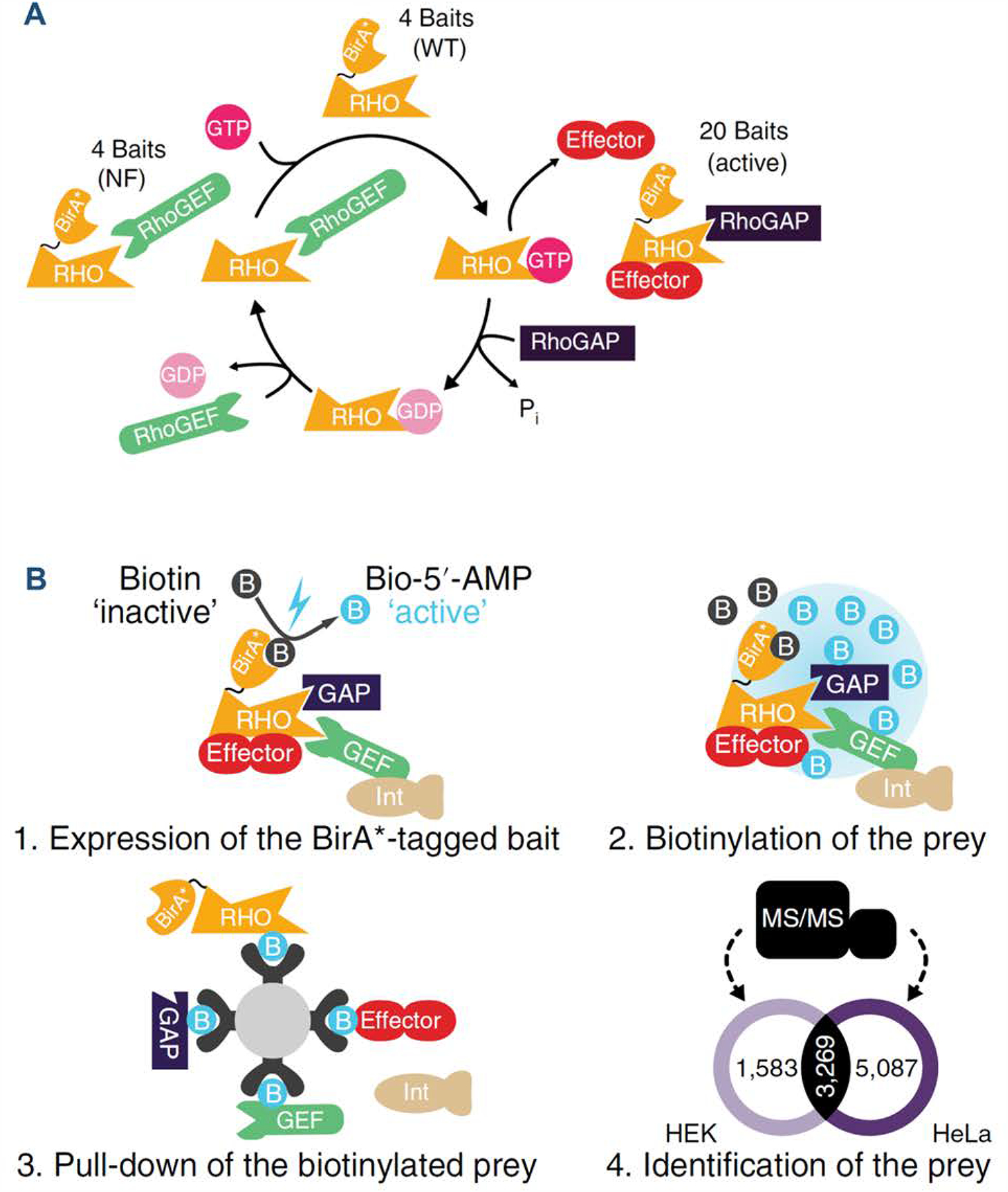

Very recently, Bagci et al. adopted the BioID workflow to define systematically the Rho family proximity interaction network and to reveal candidate RhoGEFs, RhoGAPs and effectors for classical and atypical Rho proteins (Bagci, Sriskandarajah et al. 2019). Comprehensive LC–MS/MS analyses of 28 bait proteins in total led to the discovery of 9,939 high-confidence proximity interactions in two cell lines (Figures 7A, 7B) (Bagci, Sriskandarajah et al. 2019). BirA*-Flag, BirA*-Flag-enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) and a membrane-targeted BirA*-Flag-eGFP were used as controls to filter out false-positive hits. To alleviate the limitations in nucleotide-dependent recognition of interacting partners of Rho GTPases, the authors used three types of baits, i.e. nucleotide-free Rho proteins, which have increased affinity towards GEFs; constitutively active Rho proteins that are more likely to interact with effector proteins and GAPs; and wild-type Rho proteins as activity controls (Bagci, Sriskandarajah et al. 2019). It can be envisaged that the BioID approach can be applied to the entire Ras superfamily of small GTPases to fill the knowledge gaps of many as yet discovered regulators and effectors.

Figure 7. Schematic workflow of BioID–MS in studying Rho GTPase interactomes.

(A) The Rho cycle and the strategy used to define the interactomes of Rho family members by BioID–MS. A total of 20 active, 4 nucleotide-free and 4 WT Rho GTPases were fused with BirA*; (B) Workflow of the BioID–MS approach performed in Flp-In T-Rex HEK293 and HeLa cell lines. Reprinted by permission from Springer Nature Customer Service Centre GmbH: Nat Cell Biol 22: 120–134 (“Mapping the proximity interaction network of the Rho-family GTPases reveals signalling pathways and regulatory mechanisms.”, Bagci, H., N. Sriskandarajah, A. Robert, J. Boulais, I. E. Elkholi, V. Tran, Z. Y. Lin, M. P. Thibault, N. Dube, D. Faubert, D. R. Hipfner, A. C. Gingras and J. F. Cote), COPYRIGHT 2019, Springer Nature. (Bagci, Sriskandarajah et al. 2019).

2.5. Investigations of Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs) of GTP-binding Proteins by Mass Spectrometry

GTP-binding proteins are known to be regulated by a plethora of PTMs, which are critical for the proper functions of these proteins. MS-based techniques have enjoyed extensive applications in elucidating sites and types of PTMs, including phosphorylation (Kano, Gebregiworgis et al. 2019), acetylation (Liu, Xiong et al. 2015), ubiquitination (Marotti, Newitt et al. 2002), and lipid modifications, including S-prenylation (Kho, Kim et al. 2004), N-myristoylation (Gao, Sun et al. 2017), and S-palmitoylation (Ji, Leymarie et al. 2013).

2.5.1. Phosphorylation

Phosphorylation is the most widespread type of PTMs in all eukaryotes and plays pivotal roles in signal transduction. By coupling in vitro kinase assay and phosphoproteomic profiling by LC–MS/MS, Jeong et al. revealed that phosphorylation on the conserved serine or threonine in the switch II domain of a subset of RAB GTPases (Rab3A/B/C/D, Rab5A/B, Rab8A/B, Rab10, Rab12, Rab29, Rab35 and Rab43) is mediated by LRRK2, which is a bona fide dual protein kinase/GTPase related to Parkinson’s disease (Jeong, Jang et al. 2018). Such LRRK2-mediated signaling cascades in Rab phosphorylation are believed to be associated with neurodegeneration. Their results were in agreement with an earlier study conducted by Stegar et al., where 52 Rab small GTPases were systematically screened by immunoprecipitation, tryptic digestion, and label-free LC–MS/MS quantification (Steger, Diez et al. 2017). Among the Rab proteins analyzed, 14 (Rab3A/B/C/D, Rab5A/B/C, Rab8A/B, Rab10, Rab12, Rab29, Rab35 and Rab43) were found to be specifically phosphorylated by LRRK2 (Steger, Diez et al. 2017).

Large-scale quantitative phosphoproteomic screening also facilitated the identification of a subnetwork of Rab GTPases as novel downstream targets of the PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1) (Lai, Kondapalli et al. 2015), whose mutations lead to autosomal recessive Parkinson’s diseases (Valente, Abou-Sleiman et al. 2004). Interestingly, PINK1 phosphorylates Rab GTPases at the highly conserved Ser111 in proximity to the functionally important switch II region, similar to the aforementioned LRRK2-induced phosphorylation of Rab GTPases. These findings together may provide novel mechanistic insights into the critical roles of Rab phosphorylation cascades in neurodegenerative diseases and their potential utility as biomarkers.

2.5.2. Covalent lipid modifications

Small GTPases and heterotrimeric G proteins can also undergo co- or post-translational lipid modifications to modulate their cytosol/membrane localization, including S-palmitoylation, N-myristoylation and S-prenylation (Wedegaertner, Wilson et al. 1995, Hang and Linder 2011). S-palmitoylation is a unique lipid modification in that it results in reversible modifications of the cysteine (Cys) residues with the attachment of a 16-carbon palmitic acid chain (Resh 2013). N-myristoylation, on the other hand, modifies the N-terminal glycine (Gly) residue within the consensus MGXX(S/T/C) sequence of nascent polypeptides co-translationally with a 14-carbon myristic acid chain (Resh 2013). Moreover, prenylation primarily occurs on the Cys residues within the C-terminal CAAX and CXC motifs (where ‘A’ and ‘X’ represent aliphatic and any amino acids, respectively), with the exception of Ran (Casey and Seabra 1996, Resh 2013). Protein prenylation usually involves the covalent attachments of farnesyl (15-carbon) and geranylgeranyl (20-carbon) moieties (a.k.a. farnesylation and geranylgeranylation, respectively) via a thioether linkage and are catalyzed by protein prenyltransferases (PPTase), respectively (Figure 8A) (Casey and Seabra 1996). Three distinct PPTases have been identified and can be classified into two main functional categories: the CAAX PPTases, consisting of farnesyltransferase (FTase) and geranylgeranyltransferase type I (GGTase-I); geranylgeranyltransferase type II (GGTase-II, also known as Rab GGTase or RGGTase) that recognizes a different motif and is thus referred to as a non-CAAX prenyltransferase (Maurer-Stroh, Washietl et al. 2003). A small percentage (0.5–2%) of mammalian proteins are estimated to be prenylated, which predominantly belong to the Ras superfamily of small GTPases and are catalyzed by GGTase-I or GGTase-II (McTaggart 2006). Prenylation remains essential for small GTPases to ensure proper membrane anchoring and localization to different intracellular compartments.

Figure 8. The Chemical structures of various isoprenoid derivatives used in global proteomic analysis of prenylated proteins and mechanistic studies of PPTases.

Shown are the structures of geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP), farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) (A); FPP-azide and GGPP-azide (B); C15Alk-OPP and C20Alk-OPP (C); YnF/YnGG and YnFPP/YnGGPP (D); and biotinylated-geranylpyrophosphate (BGPP) (E). Displayed in (F) is a schematic diagram of BGPP metabolic tagging workflow for LC/MS profiling of prenylome.

A handful of alternative strategies have emerged to characterize prenylated proteome and to decipher protein prenylation substrates with derivatized isoprenoid analogues by LC–MS/MS. Kho et al. pioneered a proteomic strategy that coupled detection of protein prenylation and enrichment for small GTPases, where they employed a tagging-via-substrate method relying on metabolic incorporation of azido farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP-azide) (Figure 8B) (Kho, Kim et al. 2004). Subsequent conjugation of the FPP-azide-modified proteome using a biotinylated phosphine capture reagent and affinity purification with streptavidin beads facilitated the isolation of farnesylated proteins at a proteome-wide scale. With a > 200-fold enrichment of modified proteins, 18 farnesylated proteins were identified by LC–MS/MS, accounting for 36–60% of the farnesylation subproteome (Kho, Kim et al. 2004). Later Labadie et al. reported the synthesis of eleven FPP analogues with ω-azide or alkyne moieties for bioorthogonal coupling reactions (Labadie, Viswanathan et al. 2007). These compounds were evaluated as substrates for alkylation of peptide co-substrates by yeast FTase, and five of them were shown to be alternative substrates for FPP.

Aside from using azide-derivatives of isoprenoids, Suazo et al. carried out global prenylome profiling in Plasmodium falciparum by utilizing LC–MS/MS following enrichment with alkyne-modified isoprenoid analogues FPP/C15Alk-OPP and GGPP/C20Alk-OPP (Figure 8C) (Suazo, Schaber et al. 2016). These probes facilitated the tagging of prenylated proteins via click reactions with biotin-azide for selective enrichment by streptavidin beads and subsequent proteomic profiling of the prenylome, which was later confirmed to be dominated by the Rab family of small GTPases (Suazo, Schaber et al. 2016). By combining alkyne-labeled farnesyl probe (AlkFOH) and chemoproteomic profiling with MS, Gisselberg et al. identified 20 high-confidence prenylated candidates in blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum and assessed the mechanism-of-action of antimalarial FTase inhibitors (Gisselberg, Zhang et al. 2017). More recently, Storck et al. employed a quantitative chemical proteomics strategy, which integrates cell-permeable and clickable alkyne-tagged prenylation probes YnF and YnGG (Figure 8D), to identify and validate protein targets with probe labeling through competition against natural isoprenoids (Storck, Morales-Sanfrutos et al. 2019). Both probes exhibited efficient labeling in the 20–25 kDa region based on in-gel fluorescence imaging analysis, which is in keeping with labeling of small GTPases. The application of the two probes led to the labeling of an orthogonal set of bands, suggesting that selective farnesyl and geranylgeranyl probes may provide an enhanced coverage of the entire complement of prenylated proteins.

The utility of biotin functionalized isoprenoid, i.e. biotinylated-geranylpyrophosphate (BGPP) (Figure 8E), was also explored as a novel class of protein prenylation substrate analogues that can be recognized by wild-type recombinant PPTases (Nguyen, Guo et al. 2009). The biotin-modified geranyl pyrophosphate analogue was only partially bioorthogonal in that Rab GGTase (GGTase-II), but not FTase or GGTase-I could efficiently recognize it as a substrate. In the presence of Rab GGTase and engineered FTase or GGTase-I, all prenylatable proteins can be tagged by BGPP and subsequently enriched by streptavidin beads (Figure 8F), thereby offering a proteome-wide method for assaying the prenylated proteome (“prenylome”), which comprises predominantly small GTPases of the Ras superfamily. In combination with the MudPIT technology, they successfully quantified the relative abundances of nearly all the 42 members of the Rab GTPase family in COS-7 cell lysates. More importantly, this method allows for the evaluation of the effects of PPTase inhibitors such as BMS3 on the prenylation profiles of these Rab GTPases in vivo. Cell lysates are subjected to in vitro prenylation using a recombinant Rab prenylation machinery and BGPP (Kohnke, Delon et al. 2013). In addition, Ali et al. reported a SILAC-based quantitative proteomic workflow encompassing in vivo prenylation of small GTPases by recombinant GGTase-I in the presence of BGPP (Ali, Jurczyluk et al. 2015). The method was used to probe the inhibitory effect of zoledronic acid on the prenylation levels of a total of 18 different Rab proteins in J774 macrophages. Later, a novel method was developed that capitalizes on the oxidation of the prenyl group and the cleavable properties of the resulting sulfoxide group in the gas phase to produce characteristic neutral losses that can distinguish farnesylation and geranylgeranylation in a single experiment (Bhawal, Sadananda et al. 2015).

2.5.3. Other PTMs

The small GTPases RhoA, RhoB and RhoC can be mono-ADP-ribosylated by C3 exoenzyme of Clostridium botulinum (C3bot). Quantitative profiling of ADP ribosylation of RhoA/B/C in HT22 cell lysates was achieved by incorporating SILAC-labeled internal standard in LC–MS/MS analyses (Schroder, Benski et al. 2018). Besides, reactive oxygen species (ROS)- and reactive nitrogen species (RNS)-mediated modifications of Cys118 in Ras proteins, e.g. S-glutathionylation and S-nitrosylation, were recently profiled by LC–MS/MS analysis (Ntai, Fornelli et al. 2018, Messina, De Simone et al. 2019).

2.6. Structural Profiling of GTPases

2.6.1. Native top-down mass spectrometry with ultraviolet photodissociation

Cammarata et al. first demonstrated the use of native mass spectrometry in conjunction with top-down ultraviolet photodissociation (UVPD) in probing conformational changes of KRASG12X (i.e. KRASG12C, KRASG12V, and KRASG12S) mutant proteins upon exchange of GDP for a non-hydrolyzable GTP analogue GppNHp (Cammarata, Schardon et al. 2016). Owing to the exceptional sequence coverage of UVPD–MS for proteins in unfolded or native states, the G12X mutant-induced conformations were revealed by differences in backbone fragmentation efficiency and generation of Holo (ligand-bound) fragment ions by UVPD. Similarly, Mehaffey et al. assessed the effects of the aforementioned KRASG12X mutations on the homo- and hetero-dimerization with a downstream effector protein Raf (Mehaffey, Schardon et al. 2019). To facilitate UVPD mapping of backbone cleavage, on-line size-exclusion chromatography was employed to separate the monomeric and dimeric protein complexes.

2.6.2. Native mass spectrometry in conjunction with guanine nucleotide analogues

Wiegandt et al. described the syntheses of reactive acryl derivatives of GTP (aGTP and aGppNHp; Figures 5F, 5G) and GDP (aGDP) that can form covalent bonds with strategically placed Cys residues in GTPases to irreversibly lock them into their functional states (Wiegandt, Vieweg et al. 2015). The acrylamide moieties in these derivatives can selectively react with sulfhydryl groups via Michael addition, and in the meantime non-specific reactions with distantly located Cys residues can be suppressed due to moderate electrophilicity of the acryl group. The covalent GTPase:acryl:nucleotide adducts can thus be selectively captured by native MS analyses.

Moghadamchargari et al. utilized high-resolution native ion-mobility mass spectrometry (IM–MS) to determine the kinetics and transition state of the intrinsic hydrolysis for K-Ras and its oncogenic mutants (Moghadamchargari, Huddleston et al. 2019). By employing this strategy, they unveiled, for the first time, the heterogeneity in enzyme binding with 2′-deoxy and 2′-hydroxy forms of GDP and GTP.

To evaluate conformational changes in monomeric GTPases upon nucleotide loading, hydrogen/deuterium exchange coupled with mass spectrometry (HDX–MS) is the method of choice for investigating protein complex and conformations. HDX–MS approaches have been broadly pursued in elucidating conformational changes and dynamic structural assembly that involve GPCR-Gs complex (Du, Duc et al. 2019), heterodimer formation of tubulin α and β subunits (Bennett, Chik et al. 2009), complex of covalent inhibitor and KRASG12C (Lim, Westover et al. 2014, Lu, Harrison et al. 2017), multi-domain GTPase dynamin (Srinivasan, Dharmarajan et al. 2016), and activation dynamics of Ras and Rho GTPases (Harrison, Lu et al. 2016).

Lastly, Furber et al. combined isolation of native secretory vesicles, labelling with fluorescent thiol-reactive reagents, and top-down proteomics for the analyses of Rab small GTPases (Furber, Backlund et al. 2019). Several Rab GTPases were not only consistently labeled by all three fluorescent thiol reagents but were also isolated in the cholesterol-enriched membrane proteome.

3. Concluding Remarks

Mass spectrometry (MS) constitutes a versatile tool for analyzing multiple aspects of GTP-binding proteins, including their abundances, activities, PTMs, interactions, and structural/conformational changes. The remarkable diversity in structures and functions of GTP-binding proteins confers enormous challenges in the analyses of these proteins. As a result, development of orthogonal MS-based techniques for global and targeted interrogations of the GTP-binding subproteome is often needed. In recent years, substantial advances have been made in MS instrumentation and in the developments of new tools for data acquisition and analysis. In this vein, compared with conventional discovery-based proteomic approaches (i.e. shotgun proteomics), targeted proteomic techniques offer better reproducibility, higher sensitivity and superior quantification accuracy for the subset of protein targets of interest. These recent developments have also been integrated into analytical methods for the interrogation of the abundance, activities and post-translational profiles of different GTP-binding proteins.

In the rapidly evolving field of chemical proteomics, ABPP-based workflow has been broadly employed as an invaluable tool for proteome-wide enrichment and analysis of GTP-binding proteins. We summarized herein the applications of ABPP-enabled chemoproteomic techniques involving the use of affinity capture resins, photoaffinity labeling probes, and nucleotide acyl-phosphate probes, and highlighted the technical features and some potential challenges to be addressed. Notably, by coupling affinity enrichment (e.g. with the use of reactive acyl nucleotide probes) with MRM-based quantification, robust analytical performance could be attained with substantially improved sensitivity and reproducibility, as compared with conventional DDA methods used in shotgun proteomics (Xiao, Guo et al. 2014, Miao, Xiao et al. 2016, Cai, Huang et al. 2018). That being said, using acyl phosphate backbones in studying GTP- and other nucleotide-binding proteins may suffer from compromised selectivity owing to non-specific labeling (Xiao, Guo et al. 2013). Off-target engagement of ATP-binding proteins due to the promiscuous reactivity of acyl phosphate may arise from the generic design of these probes in which structurally similar adenine/guanine nucleotide-based chemical scaffolds were employed (Montgomery, Sorum et al. 2014). As discussed by us and others, to eliminate non-specific interactions arising from the high reactivities of acyl phosphate functional groups, competition experiments using low (10 μM) and high (100 μM) concentrations of the probe can distinguish specific from non-specific labeling (Xiao, Guo et al. 2013, Xiao, Ji et al. 2014, Nordin, Liu et al. 2015, Dong, Gao et al. 2019).

A potential limitation may arise from the bulky affinity tag (i.e. biotin or desthiobiotin) and the resulting poor cell permeability and potentially compromised binding affinities of chemical probes or functionalized enzyme substrates. The introduction of less sterically hindered bioorthogonal functional groups, e.g. alkynyl and azido moieties, provides superior cell permeability and reaction kinetics for in situ labeling in living cells (Patterson, Nazarova et al. 2014). However, studies with the incorporation of these two types of chemical tags into isoprenoids suggested that substrate specificity may be affected, where alkynyl-isoprenoid probes generally render better sensitivity than their azido-tagged counterparts (Charron, Tsou et al. 2011). The adoption of other bioorthogonal groups such as triaryl phosphines, which conjugate with azides via Staudinger ligation, can also effectively mitigate cross-reactivity issues; hence, despite their relatively low reaction rates, triaryl phosphines are highly recommended for in vivo analysis (Patterson, Nazarova et al. 2014). It can be envisaged that a combination of orthogonal enrichment strategies and advanced quantitative proteomic techniques such as MRM, PRM and DIA will continue to improve the selectivity, sensitivity, reproducibility and accuracy in the chemical proteomic analysis of GTP-binding proteins.

It is also of note that GTP-derived probes are overall much less explored than the ATP analogs, and thus many strategies applied to the design and working principles of ATP probes may be adapted for GTP probes. For instance, in analogy to the concept of kinobeads in evaluating target profiles of kinase inhibitors under native conditions, functionalization of affinity-based enrichment handle with GTPase inhibitor scaffolds of diverse inhibitory mechanisms may allow for in-depth chemoproteomic characterizations of their modes of actions and active site-directed interactions with cellular protein targets. Multiplexed inhibitor beads (MIBs) that utilize broad-spectrum GTPase inhibitors may also provide a novel approach for proteome-wide enrichment of distinct classes of GTP-binding proteins. With intense interest in applying chemoproteomic platforms in the characterization of active-site competitive enzyme inhibitors to facilitate drug development, cautions need to be exerted regarding the potential cross-reactivities of chemical probes and the effects of conjugation sites on labeling efficiency. Moreover, data should be carefully interpreted so as to discriminate between bona fide interacting proteins and non-specific interactions.

Among the GTP-binding proteins, small GTPases of the Ras superfamily constitute the largest enzyme class and account for over 40% of the GTP-binding proteome. Multiple lines of research initiated the development and applications of novel targeted quantitative proteomic methods for high-throughput and reproducible profiling of small GTPases in cultured cells and patient-derived brain tissues that carry disease-relevant mutations. We believe that this is an important area of study because small GTPases of the Ras superfamily represent a class of crucial signaling molecules in cells, and aberrant expression of these proteins is implicated in various human diseases. In this regard, we developed and utilized MS-based approaches for targeted quantitative proteomic analysis of small GTPases of the Ras superfamily in cancer cells and tissues. By employing MRM, in conjunction with the use of SILAC or crude synthetic SIL peptides, we achieved high-throughput targeted quantitative profiling of the altered expressions of small GTPases accompanied with cancer metastasis and drug resistance in cultured human cancer cells, adipocyte differentiation in murine cells, and development of neurodegenerative diseases in patient-derived tissue samples (Huang, Qi et al. 2018, Huang and Wang 2018, Huang, Darvas et al. 2019, Huang and Wang 2019, Yang, Huang et al. 2020). By virtue of its superior sensitivity, reproducibility and specificity, MRM has been widely used for targeted proteomics during the past two decades; however, owing to the use of low-resolution mass analyzer in MS/MS analysis, the method is more susceptible to background interference from sample matrix. Future targeted assay development by using PRM or DIA is therefore highly recommended.

Apart from analyzing the expression levels of small GTPases, MS also found its widespread applications in studying the structure/conformation and interactome of GTP-binding proteins. For instance, MS, in conjunction with click chemistry or cellular proximity-based biotinylation, has been employed for interrogating the interactomes of some GTP-binding proteins and their regulatory proteins (GAPs, GEFs, and GDIs). Moreover, HDX–MS and top-down proteomic analysis have offered important insights into nucleotide-dependent conformational changes of GTPases.

Lastly, in the field of drug discovery, RBD capture in conjunction with MRM-based assay has increasingly been applied to interrogate covalent target occupancy for newly developed KRASG12C inhibitors (ARS-107 and ARS-853), which quantifies KRASG12C mutant-specific peptide (LVVVGAGCVGK) upon inhibition. Advanced designs for GTPase inhibitors with high affinity and specificity may facilitate the development of novel targeted proteomic assays for different families of GTPases.

Together, MS serves as a highly versatile analytical tool and has contributed vastly to many aspects of research on GTP-binding proteins. It can be envisaged that future advances in instrumentation, methods for data acquisition and analysis, and sample preparation strategies, will continue to promote the studies of GTP-binding proteins, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding about the biological functions of these proteins.

Acknowledgement.

This paper is dedicated to Professor Michael L. Gross for his outstanding achievements in the field of mass spectrometry, and for his inspirations, trainings, and support of young scientists in mass spectrometry. The authors would like to thank the National Institutes of Health for supporting this research (R01 CA210072), and M.H. was supported in part by an NRSA T32 Institutional Training Grant (T32 ES018827).

Abbreviations

- GDP

Guanosine diphosphate

- GTP

Guanosine triphosphate

- GTPases

Guanosine triphosphatases

- GEFs

Guanine nucleotide exchange factors

- GAPs

GTPase-activating proteins

- Gα

Heterotrimeric G protein α subunit

- GDIs

Guanosine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

Tandem mass spectrometry

- DDA

Data-dependent acquisition

- DIA

Data-independent acquisition

- MRM

Multiple-reaction monitoring

- PRM

Parallel-reaction monitoring

- ABPP

Activity-based protein profiling

- LC

Liquid chromatography

- SILAC

Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture

- PAL

Photoaffinity labeling

- MudPIT

Multi-dimensional protein identification technology

- SDS-PAGE

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- AP–MS

Affinity purification–mass spectrometry

- PTMs

Post-translational modifications

Biographies

Biography

Ming Huang completed her BSc (2010) in Chemical Biology at Sun Yat-sen University (China) and MSc (2012) in Bioanalytical Chemistry at Western University (Canada). Ming obtained her PhD degree (2019) in the Environmental Toxicology Graduate Program at University of California, Riverside, under the supervision of Prof. Yinsheng Wang. Her dissertation research projects were focused on the development and applications of targeted proteomics methods for high-throughput quantitative profiling of small GTPases of the Ras superfamily in cultured cancer cells and tissue samples to assess the roles of small GTPases in diseases and cellular response to environmental stimuli.

Yinsheng Wang obtained his Ph. D. degree from Washington University in 2001, working under the guidance of Profs. Michael L. Gross and John-Stephen A. Taylor. He is a Distinguished Professor in the Chemistry Department and the Environmental Toxicology graduate program at the University of California Riverside. His research interest encompasses DNA damage and mutagenesis, proteomics, and epigenetics. His group members employ inter-disciplinary approaches, encompassing mass spectrometry, synthetic chemistry, molecular biology, genetics, and genomics, to tackle their research projects.

References

- Adam GC, Sorensen EJ and Cravatt BF (2002). “Proteomic profiling of mechanistically distinct enzyme classes using a common chemotype.” Nature Biotechnology 20(8): 805–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aebersold R and Mann M (2003). “Mass spectrometry-based proteomics.” Nature 422(6928): 198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali N, Jurczyluk J, Shay G, Tnimov Z, Alexandrov K, Munoz MA, Skinner OP, Pavlos NJ and Rogers MJ (2015). “A highly sensitive prenylation assay reveals in vivo effects of bisphosphonate drug on the Rab prenylome of macrophages outside the skeleton.” Small GTPases 6(4): 202–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagci H, Sriskandarajah N, Robert A, Boulais J, Elkholi IE, Tran V, Lin ZY, Thibault MP, Dube N, Faubert D, Hipfner DR, Gingras AC and Cote JF (2019). “Mapping the proximity interaction network of the Rho-family GTPases reveals signalling pathways and regulatory mechanisms.” Nat Cell Biol 22: 120–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantscheff M, Eberhard D, Abraham Y, Bastuck S, Boesche M, Hobson S, Mathieson T, Perrin J, Raida M, Rau C, Reader V, Sweetman G, Bauer A, Bouwmeester T, Hopf C, Kruse U, Neubauer G, Ramsden N, Rick J, Kuster B and Drewes G (2007). “Quantitative chemical proteomics reveals mechanisms of action of clinical ABL kinase inhibitors.” Nat Biotechnol 25(9): 1035–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Sagi D and Hall A (2000). “Ras and Rho GTPases: a family reunion.” Cell 103(2): 227–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckler MD, Higginbotham JN, Franklin JL, Ham AJ, Halvey PJ, Imasuen IE, Whitwell C, Li M, Liebler DC and Coffey RJ (2013). “Proteomic analysis of exosomes from mutant KRAS colon cancer cells identifies intercellular transfer of mutant KRAS.” Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12(2): 343–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MJ, Chik JK, Slysz GW, Luchko T, Tuszynski J, Sackett DL and Schriemer DC (2009). “Structural mass spectrometry of the αβ-tubulin dimer supports a revised model of microtubule assembly.” Biochemistry 48(22): 4858–4870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhawal RP, Sadananda SC, Bugarin A, Laposa B and Chowdhury SM (2015). “Mass spectrometry cleavable strategy for identification and differentiation of prenylated peptides.” Anal Chem 87(4): 2178–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollinger JG, Stergachis AB, Johnson RS, Egertson JD and MacCoss MJ (2016). “Selecting Optimal Peptides for Targeted Proteomic Experiments in Human Plasma Using In Vitro Synthesized Proteins as Analytical Standards.” Methods Mol Biol 1410: 207–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos JL, Rehmann H and Wittinghofer A (2007). “GEFs and GAPs: critical elements in the control of small G proteins.” Cell 129(5): 865–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourmaud A, Gallien S and Domon B (2016). “Parallel reaction monitoring using quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer: Principle and applications.” Proteomics 16(15–16): 2146–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne HR, Sanders DA and McCormick F (1990). “The GTPase superfamily: a conserved switch for diverse cell functions.” Nature 348(6297): 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai R, Huang M and Wang Y (2018). “Targeted Quantitative Profiling of GTP-Binding Proteins in Cancer Cells Using Isotope-Coded GTP Probes.” Anal Chem 90(24): 14339–14346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammarata MB, Schardon CL, Mehaffey MR, Rosenberg J, Singleton J, Fast W and Brodbelt JS (2016). “Impact of G12 Mutations on the Structure of K-Ras Probed by Ultraviolet Photodissociation Mass Spectrometry.” J Am Chem Soc 138(40): 13187–13196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]