ABSTRACT

Background

Adherence to a healthy diet has been associated with reduced risk of chronic diseases. Identifying nutritional biomarkers of diet quality may be complementary to traditional questionnaire-based methods and may provide insights concerning disease mechanisms and prevention.

Objective

To identify metabolites associated with diet quality assessed via the Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) and its components.

Methods

This cross-sectional study used FFQ data and plasma metabolomic profiles, mostly lipid related, from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS, n = 1460) and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS, n = 1051). Linear regression models assessed associations of the AHEI and its components with individual metabolites. Canonical correspondence analyses (CCAs) investigated overlapping patterns between AHEI components and metabolites. Principal component analysis (PCA) and explanatory factor analysis were used to consolidate correlated metabolites into uncorrelated factors. We used stepwise multivariable regression to create a metabolomic score that is an indicator of diet quality.

Results

The AHEI was associated with 83 metabolites in the NHS and 96 metabolites in the HPFS after false discovery rate adjustment. Sixty-three of these significant metabolites overlapped between the 2 cohorts. CCA identified “healthy” AHEI components (e.g., nuts, whole grains) and metabolites (n = 27 in the NHS and 33 in the HPFS) and “unhealthy” AHEI components (e.g., red meat, trans fat) and metabolites (n = 56 in the NHS and 63 in the HPFS). PCA-derived factors composed of highly saturated triglycerides, plasmalogens, and acylcarnitines were associated with unhealthy AHEI components while factors composed of highly unsaturated triglycerides were linked to healthy AHEI components. The stepwise regression analysis contributed to a metabolomics score as a predictor of diet quality.

Conclusion

We identified metabolites associated with healthy and unhealthy eating behaviors. The observed associations were largely similar between men and women, suggesting that metabolomics can be a complementary approach to self-reported diet in studies of diet and chronic disease.

Keywords: Alternate Healthy Eating Index, biomarker, diet quality, metabolites, metabolomics

Introduction

Diet quality involves the evaluation of both overall diet and the quality of individual food and nutrients (1, 2). Several indices have been validated to be used as measures of dietary patterns (2). Studies demonstrated that regardless of which index is used for diet quality assessment, adherence to a healthy diet has been associated with a reduced risk of chronic diseases (3–5). The Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI-2010), one measure of diet quality, has consistently predicted chronic disease outcomes in different populations (6, 7).

Much of our knowledge regarding the associations of diet quality with health outcomes stems from studies assessing dietary intake patterns using questionnaires or food diaries. These dietary intake measurement methods may differ between regions, and in some countries, there may be a lack of either validated questionnaires related to age and health status or food composition databases to analyze gathered dietary records (8). Therefore, many studies do not include a detailed diet assessment, which can lead to inconsistent findings (9). In addition, nutritional epidemiologists should be equipped with a variety of dietary assessment methods, including biochemical markers to capture individual differences in dietary intakes (10). As such, it is crucial to develop reliable and accurate methods that can aid in understanding the link between food patterns and metabolic health outcomes and may be a complementary approach to achieving accurate dietary assessments (11).

Recently, the hypothesis that associations may exist between dietary patterns and circulating metabolites has generated considerable interest. Evidence demonstrates that a metabolomics approach, as a sensitive analytical method, may be well suited to identify metabolites that can serve as dietary biomarkers in studies of health outcomes and may highlight underlying metabolic pathways related to diet (12, 13).

Several studies have investigated the associations of individual food groups with circulating metabolites, but few have examined overall healthy dietary patterns (14, 15). Most studies that have examined dietary patterns did not use a predefined approach to identify food groups (16, 17). Although a large study has explored the correlation of several dietary indices, including the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) 2010, the Alternate Mediterranean Diet Score, the World Health Organization Healthy Diet Indicator, and the Baltic Sea Diet (18) with serum metabolites, this study identified dietary patterns–related biomarkers in a sample of male Finnish smokers. As both metabolites and dietary patterns differ between males and females (19, 20), as well as between smokers and nonsmokers (21–23), whether the findings can be generalized to women and nonsmokers is not clear. Therefore, we performed the current study with the objective of identifying metabolites associated with the AHEI and its components among men in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) and women in the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS). The identified metabolites were further assessed to identify metabolite patterns related to healthy and unhealthy aspects of diet.

Methods

Study design and population

The NHS was initiated in 1976 when 121,700 female registered nurses, ages 30–55 y, completed a mailed questionnaire about their medical history and health behaviors (Supplemental Figure 1). Updated information has been collected using biennial questionnaires. In 1989–1990, blood samples were collected from 32,826 participants and mailed overnight on icepacks (24). After being divided into plasma, WBC, and RBC components, samples were stored at less than −130°C.

The HPFS was established in 1986 when 51,529 male health professionals, ages 40–75 y, responded to a mailed biennial questionnaire concerning medical history, lifestyle, and health behaviors (Supplemental Figure 1). In 1993–1995, 18,225 men provided blood samples, which were shipped, processed, and stored as described for the NHS samples (25).

Metabolomic profiles were measured in plasma samples from 1460 NHS and 1051 HPFS participants as part of several nested case-control studies. Specific endpoints included amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), pancreatic cancer (26), ovarian cancer (27, 28), and rheumatoid arthritis in the NHS, while ALS, pancreatic cancer (26), and prostate cancer (29) were evaluated in the HPFS. Because each study focused on disease incidence, all plasma samples from cases were collected prior to disease diagnosis.

Diet quality assessment

In both cohorts, dietary intake was assessed using a validated semiquantitative FFQ that was composed of 131 food items and completed approximately every 4 y (30). Data from the closest FFQ prior to blood collection were used to calculate the AHEI (7). The AHEI was derived from the following components: vegetables, fruit, whole grains, sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juice, nuts and legumes, red/processed meat, trans fat, long-chain n–3 (ω-3) fats (EPA + DHA), PUFA (no EPA or DHA), sodium, and alcohol (7). Among these components, higher intakes of sodium, sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juice, red/processed meat, and trans fat are assigned a lower score, whereas higher intakes of long-chain fats, whole grains, vegetables, and fruit are assigned a higher score. The score for each of the 11 components ranges from 0 (worst) to 10 (best) points, and the overall AHEI score ranges from 0 to 110 points (7).

Metabolite assessments

Profiles of plasma metabolites were measured as peak areas by LC-MS/MS metabolomics in Dr. Clary Clish's laboratory at the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University. All the information on profiling the metabolites has been described in detail elsewhere (31). Briefly, in polar metabolite profiling methods, reference standards of metabolites were used to obtain chromatographic retention times, MS multiple-reaction monitoring transitions, declustering potentials, and collision energies. Data related to negative ionization mode were obtained using a modified type of hydrophilic interaction chromatography method that was applied on an ACQUITY UPLC (Waters) coupled to a 5500 QTRAP triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX). A modified MS acquisition was used to acquire positive ionization mode data. In this method, all multiple-reaction monitoring transitions were performed in 1 method line. Plasma lipids were evaluated by a TRAP triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX), coupled to a 1200 Series Pump (Agilent Technologies) and an HTS PAL Autosampler (Leap Technologies) (32). MultiQuant1.2 software (AB SCIEX) was used for peak integration, and each identified peak was compared with standards as an identity confirmation. LC-MS/MS system sensitivity and chromatography quality were examined prior to each set of analyses (26). These analyses were performed at the beginning and after sets of 20 samples on the following reference samples: synthetic mixtures of reference metabolites (Sigma) and a lipid extract prepared from a pooled human plasma stock (Bioreclamation). Blinded quality control (QC) samples, 3 heparin plasma pools (NHS) or 3 EDTA plasma pools (HPFS), were included among study samples. We excluded all metabolites with CV >25% or intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) <0.4 among QC samples, no variability, or >10% missing across study samples. We also excluded metabolites not passing our pilot studies investigating the effect of delayed processing and within-person stability over time (28 in the NHS and 27 in the HPFS) (31).

The total number of metabolites assessed in our study was 212 in the NHS and 173 in the HPFS. The major categories of metabolites included amino acids and derivatives, amines, lipids, fatty acids, and bile acids.

Covariate assessment

Participants reported their height on the baseline questionnaire (i.e., 1976 in the NHS and 1986 in the HPFS). We used the closest questionnaires prior to blood draw to ascertain weight, recreational physical activity, and smoking status. Participants were asked to report the average amount of time per week dedicated to recreational physical activity. On the basis of the information from this validated questionnaire, weekly energy expenditure in metabolic equivalent hours was obtained (33). Information from all questionnaires prior to blood collection was used to assess history of hypercholesterolemia and hypertension. Total energy intake was calculated using the same FFQ that was used to assess diet quality.

Statistical analysis

In our analysis, the metabolites were log-transformed followed by cohort- and study-specific z scores to account for potential batch effects.

In our main analysis, associations between the AHEI (modeled as a continuous variable) and individual metabolites were examined using multivariable linear regression adjusted for age, BMI, fasting status, total caloric intake, total physical activity, smoking status, and case-control status. We estimated to have 80% power to observe an effect size of a 0.01-unit increase in transformed metabolite levels per 1-unit increase in AHEI score at α = 0.05 in the NHS and HPFS. We used the false discovery rate (FDR) procedure (34) to correct for testing multiple correlated hypotheses (35).

In a secondary analysis, we then employed canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) to describe how metabolites significantly associated with the AHEI in the linear regression model were related to the various components of the AHEI. CCA is a multivariable method that identifies relations between 2 data matrices (metabolites and AHEI components) that were measured on the same samples (36). In this approach, the metabolites identified as being associated with the AHEI are constrained to linear combinations of the AHEI components, adjusting for the described covariates. As the first axis (CCA1) was able to separate healthy from unhealthy AHEI components, we used the information summarized by this component for all CCA-related subsequent analyses. Based on the loadings of CCA1, we computed a score for each AHEI component and each metabolite by summing over the product between AHEI components/metabolite loadings and the assessed AHEI component/metabolite values in each sample.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of AHEI-related metabolites was subsequently used to cluster AHEI-related metabolites into different groups [i.e., principal components (PCs)] reflecting the independent sources of variation in the data (36, 37). Based on the variance of the components (examined by a scree plot) and the standard criterion of eigenvalues >1 (38), we selected PCs for further analysis. Then, to summarize the relation between the AHEI components and the constrained AHEI-linked metabolite values, we identified interpretable factors by running an exploratory factor analysis using varimax rotation and the number of PCs we selected before (38). We summed the standardized variable values within each factor to obtain a 1-dimensional score for each factor. The associations of these scores as our dependent variable with each AHEI component as our variable of interest were assessed using multivariable linear regression adjusting for appropriate covariates as well as controlling for multiple testing (FDR).

Finally, the data from 2 cohorts were restricted to metabolites measured in both the NHS and HPFS, then merged to determine a metabolomic-related AHEI score that applies to both men and women using a stepwise regression analysis. The merged data were randomly divided into discovery and validation data sets (70%/30%), which included equal proportions from the NHS and HPFS. The predicted AHEI score (based on the lipid-related metabolomic profile) was developed using stepwise regression in the discovery data set after adjustment for age and BMI. The metabolomic score was calculated as a linear combination of selected (P < 0.05) metabolites weighted by the β coefficients from the stepwise regression. To assess the performance of the score in the validation data set, we used the coefficients from the discovery data set and the measured metabolite values from the validation data set. Using all metabolites selected in the discovery data set, we ran 1 model in the validation data set to estimate the R-squared value. We also examined the correlation and partial correlation (adjusting for age and BMI) between the predicted AHEI score and the FFQ-based AHEI score in both the discovery and validation data sets. We used the statistical framework R 3.1.0 (www.rproject.org) (39) for the data analysis.

Results

Men and women in the highest quintile of the AHEI were older, were more physically active, and had lower BMI and total calorie intake (Tables 1 and 2). Participants with a higher AHEI score were less likely to be current smokers in the HPFS.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of participants from the Nurses’ Health Study with measured metabolomics by quintile of the Alternate Healthy Eating Index1

| Characteristic | Q1 (n = 262) | Q2 (n = 262) | Q3 (n = 263) | Q4 (n = 261) | Q5 (n = 262) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at blood draw, y | 55.88 (49.77–61.42) | 57.7 (51.44–63.21) | 58.33 (52.71–63.38) | 58.25 (52.58–63.5) | 58.83 (54.19–63.67) | 0.0003 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.39 (21.97–27.44) | 24.8 (22.46–27.45) | 24.56 (22.33–27.46) | 24.4 (22.14–28.27) | 23.65 (22.14–27.1) | 0.291 |

| Fasting status at blood draw | 0.590 | |||||

| Fasted | 171 (65) | 188 (72) | 183 (70) | 179 (69) | 177 (68) | |

| Total caloric intake, kcal/d | 1844.5 (1568.25–2155.75) | 1718 (1476–2074) | 1710 (1424.5–2064.5) | 1755 (1427–2130) | 1697 (1415.5–2026.5) | 0.003 |

| Total physical activity, MET-hours/wk | 6.5 (2.9–15.15) | 8.9 (3.2–18.75) | 10.5 (3.98–20.4) | 11.35 (4.57–26.6) | 15.2 (6.65–27.05) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status at blood draw | 0.30 | |||||

| Never | 118 (61) | 122 (63) | 118 (56) | 97 (48) | 124 (56) | |

| Past | 12 (6) | 10 (5) | 16 (8) | 16 (8) | 17 (8) | |

| No, unknown history | 28 (15) | 31 (16) | 42 (20) | 47 (23) | 40 (18) | |

| Current | 34 (18) | 30 (16) | 34 (16) | 44 (22) | 40 (18) | |

| Cases2 | 0.373 | |||||

| Cases | 97 (37) | 100 (38) | 97 (37) | 116 (44) | 102 (39) | |

| Controls | 165 (63) | 162 (62) | 166 (63) | 145 (56) | 160 (61) | |

| Original endpoint studies3 | 0.020 | |||||

| ALS | 21 (8) | 25 (10) | 21 (8) | 19 (7) | 25 (10) | |

| Pancreatic cancer | 61 (23) | 67 (26) | 70 (27) | 76 (29) | 72 (27) | |

| Ovarian cancer | 71 (27) | 87 (33) | 85 (32) | 103 (39) | 93 (35) | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 109 (42) | 83 (32) | 87 (33) | 63 (24) | 72 (27) | |

| History of high cholesterol at blood draw | 0.084 | |||||

| Yes | 61 (23) | 78 (30) | 70 (27) | 89 (34) | 74 (28) | |

| History of high blood pressure at blood draw | 0.717 | |||||

| Yes | 71 (27) | 72 (27) | 69 (26) | 59 (23) | 70 (27) |

Values are presented as median (IQRs) or n (%). Kruskal-Wallis and χ2 tests were used for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; MET, metabolic equivalent; Q, quintile.

Cases were from the endpoints including ALS, pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Metabolomics were originally assessed in nested case-control studies of these conditions.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of participants from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study with measured metabolomics by quintile of the Alternate Healthy Eating Index1

| Characteristic | Q1 (n = 204) | Q2 (n = 203) | Q3 (n = 203) | Q4 (n = 203) | Q5 (n = 203) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at blood draw, y | 62.54 (56.83–69.83) | 64.33 (55.41–69.59) | 63.58 (56.62–69.58) | 64.42 (57.29–69.42) | 65.25 (60.75–70.88) | 0.026 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.8 (23.7–28.6) | 25.6 (23.6–27.6) | 25.1 (23.6–27.4) | 25.1 (23.4–27.08) | 24.5 (23–26.9) | 0.001 |

| Fasting status at blood draw | 0.763 | |||||

| Fasted | 128 (63) | 130 (64) | 120 (59) | 123 (61) | 119 (59) | |

| Total caloric intake, kcal/d | 2065 (1758.25–2451) | 1991 (1584.5–2418.5) | 1889 (1525.25–2353.75) | 1928 (1535.5–2362) | 1833 (1490–2125) | <0.001 |

| Total physical activity, MET-hours/wk | 16.4 (6.5–41) | 25.55 (10.5–41.62) | 28.6 (12.1–46.5) | 28.25 (13.77–52.15) | 31 (14.4–47.6) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status at blood draw | 0.001 | |||||

| Never | 82 (40) | 99 (50) | 87 (43) | 87 (43) | 93 (46) | |

| Past | 96 (47) | 73 (36) | 101 (50) | 88 (44) | 98 (48) | |

| Current | 22 (11) | 21 (10) | 8 (4) | 11 (5) | 7 (3) | |

| Cases2 | 0.211 | |||||

| Cases | 108 (53) | 130 (64) | 117 (58) | 117 (58) | 124 (61) | |

| Controls | 96 (47) | 73 (36) | 86 (42) | 86 (42) | 79 (39) | |

| Original endpoint studies3 | 0.964 | |||||

| ALS | 13 (6) | 16 (8) | 16 (8) | 19 (9) | 12 (6) | |

| Pancreatic cancer | 50 (25) | 47 (23) | 51 (25) | 48 (24) | 49 (24) | |

| Prostate cancer | 141 (69) | 140 (69) | 136 (67) | 136 (67) | 142 (70) | |

| History of high cholesterol at blood draw | 0.006 | |||||

| Yes | 67 (33) | 82 (40) | 83 (41) | 91 (45) | 103 (51) | |

| History of high blood pressure at blood draw | 0.347 | |||||

| Yes | 53 (26) | 71 (35) | 58 (29) | 62 (31) | 65 (32) |

Values are presented as median (IQRs) or n (%). Kruskal-Wallis and χ2 tests were used for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; MET, metabolic equivalent; Q, quintile.

Cases were from the endpoints including ALS, pancreatic cancer, and prostate cancer.

Metabolomics were originally assessed in nested case-control studies of these conditions.

Individual metabolites associated with the AHEI and AHEI components

The AHEI was associated with 83 and 96 plasma metabolites in the NHS and HPFS, respectively (Table 3). For some metabolites, the R2 value was large (e.g., ≤19% of the variability of C10 acylcarnitine among HPFS samples was explained by the AHEI). Adjusting for chronic conditions (high cholesterol and hypertension) did not affect the associations and the R2 results (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Multivariable linear regression analyses for the association of the Alternate Healthy Eating Index with plasma metabolites using a false discovery rate correction1

| NHS (n = 1460) | HPFS (n = 1051) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolite | β | SE | R 2 | P value | β | SE | R 2 | P value |

| C10 carnitine | –0.0080 | 0.0028 | 0.1296 | 0.0048 | –0.0105 | 0.0028 | 0.1917 | 0.0002 |

| C12:1 carnitine | –0.0090 | 0.0028 | 0.1249 | 0.0013 | –0.0125 | 0.0029 | 0.1612 | 1.75 × 10−5 |

| C12 carnitine | –0.0076 | 0.0028 | 0.1091 | 0.0072 | –0.0123 | 0.0029 | 0.1440 | 3.01 × 10−5 |

| C14 carnitine | –0.0073 | 0.0029 | 0.0968 | 0.0111 | –0.0137 | 0.0030 | 0.0864 | 6.62 × 10−6 |

| C16:1 LPC | –0.0114 | 0.0033 | 0.0334 | 0.0007 | –0.0082 | 0.0036 | 0.0480 | 0.0234 |

| C18:0 CE | –0.0085 | 0.0034 | 0.0411 | 0.0122 | –0.0202 | 0.0036 | 0.0732 | 2.03 × 10−8 |

| C18:1 LPC | –0.0102 | 0.0034 | 0.0358 | 0.0024 | –0.0099 | 0.0034 | 0.1301 | 0.0037 |

| C18:1 LPE | –0.0104 | 0.0032 | 0.0849 | 0.0014 | –0.0103 | 0.0034 | 0.1319 | 0.0027 |

| C18:2 LPE | –0.0081 | 0.0033 | 0.0880 | 0.0136 | –0.0114 | 0.0035 | 0.1293 | 0.0010 |

| C18:2 SM | –0.0145 | 0.0032 | 0.0719 | 7.71 × 10−6 | –0.0205 | 0.0035 | 0.0575 | 9.05 × 10−9 |

| C20:4 LPE | –0.0122 | 0.0033 | 0.0413 | 0.0002 | –0.0172 | 0.0036 | 0.0456 | 2.28 × 10−6 |

| C20:5 CE | 0.0109 | 0.0034 | 0.0548 | 0.0014 | 0.0212 | 0.0036 | 0.0832 | 4.62 × 10−9 |

| C22:6 CE | 0.0196 | 0.0033 | 0.0880 | 5.76 × 10−9 | 0.0261 | 0.0035 | 0.1080 | 3.72 × 10−13 |

| C22:6 LPC | 0.0143 | 0.0033 | 0.0499 | 1.46 × 10−5 | 0.0190 | 0.0035 | 0.1239 | 6.53 × 10−8 |

| C22:6 LPE | 0.0095 | 0.0033 | 0.0578 | 0.0041 | 0.0216 | 0.0035 | 0.0882 | 1.62 × 10−9 |

| C32:1 DAG | –0.0080 | 0.0032 | 0.1709 | 0.0121 | –0.0096 | 0.0034 | 0.1259 | 0.0051 |

| C34:0 PS | 0.0083 | 0.0033 | 0.0818 | 0.0117 | 0.0159 | 0.0036 | 0.0635 | 1.47 × 10−5 |

| C36:0 PE | –0.0086 | 0.0033 | 0.0373 | 0.0093 | –0.0137 | 0.0036 | 0.0369 | 0.0001 |

| C36:1 DAG | –0.0093 | 0.0031 | 0.1676 | 0.0026 | –0.0118 | 0.0034 | 0.1465 | 0.0006 |

| C36:2 DAG | –0.0086 | 0.0031 | 0.1573 | 0.0061 | –0.0130 | 0.0035 | 0.1017 | 0.0003 |

| C36:2 PC plasmalogen | –0.0102 | 0.0033 | 0.0899 | 0.0018 | –0.0187 | 0.0034 | 0.1160 | 4.02 × 10−8 |

| C36:2 PE plasmalogen | –0.0150 | 0.0034 | 0.0399 | 1.34 × 10−5 | –0.0248 | 0.0036 | 0.0811 | 8.23 × 10−12 |

| C36:3 PE plasmalogen | –0.0121 | 0.0034 | 0.0362 | 0.0004 | –0.0237 | 0.0035 | 0.0834 | 4.61 × 10−11 |

| C36:4 PE plasmalogen | –0.0094 | 0.0034 | 0.0308 | 0.0053 | –0.0195 | 0.0035 | 0.0666 | 3.94 × 10−8 |

| C38:3 PE plasmalogen | –0.0104 | 0.0033 | 0.0766 | 0.0017 | –0.0204 | 0.0035 | 0.0772 | 1.05 × 10−8 |

| C38:4 PC plasmalogen | –0.0183 | 0.0033 | 0.0465 | 5.73 × 10−8 | –0.0299 | 0.0035 | 0.1059 | 5.06 × 10−17 |

| C38:5 PE plasmalogen | –0.0134 | 0.0033 | 0.0399 | 6.31 × 10−5 | –0.0223 | 0.0035 | 0.0697 | 5.82 × 10−10 |

| C38:6 PC | 0.0179 | 0.0033 | 0.0883 | 5.80 × 10−8 | 0.0239 | 0.0035 | 0.0920 | 2.90 × 10−11 |

| C38:6 PE | 0.0106 | 0.0033 | 0.0791 | 0.0013 | 0.0153 | 0.0036 | 0.0560 | 2.30 × 10−5 |

| C38:6 PE plasmalogen | –0.0112 | 0.0033 | 0.0304 | 0.0009 | –0.0153 | 0.0036 | 0.0426 | 2.25 × 10−5 |

| C38:7 PC plasmalogen | 0.0114 | 0.0033 | 0.0614 | 0.0006 | 0.0160 | 0.0036 | 0.0766 | 1.03 × 10−5 |

| C38:7 PE plasmalogen | 0.0103 | 0.0033 | 0.0496 | 0.0018 | 0.0161 | 0.0036 | 0.0491 | 9.43 × 10−6 |

| C40:10 PC | 0.0135 | 0.0032 | 0.0748 | 2.16 × 10−5 | 0.0189 | 0.0035 | 0.1016 | 1.30 × 10−7 |

| C40:6 PC | 0.0140 | 0.0033 | 0.0805 | 2.08 × 10−5 | 0.0201 | 0.0036 | 0.0636 | 3.42 × 10−8 |

| C40:6 PS | –0.0111 | 0.0032 | 0.0757 | 0.0007 | –0.0169 | 0.0035 | 0.0580 | 1.58 × 10−6 |

| C40:9 PC | 0.0182 | 0.0033 | 0.0898 | 2.91 × 10−8 | 0.0243 | 0.0035 | 0.0962 | 1.09 × 10−11 |

| C46:1 TAG | –0.0094 | 0.0032 | 0.1204 | 0.0038 | –0.0118 | 0.0034 | 0.1365 | 0.0006 |

| C46:2 TAG | –0.0088 | 0.0033 | 0.1142 | 0.0072 | –0.0114 | 0.0034 | 0.1349 | 0.0009 |

| C48:1 TAG | –0.0079 | 0.0032 | 0.1408 | 0.0143 | –0.0093 | 0.0034 | 0.1342 | 0.0068 |

| C48:2 TAG | –0.0097 | 0.0032 | 0.1421 | 0.0029 | –0.0128 | 0.0034 | 0.1303 | 0.0002 |

| C48:3 TAG | –0.0088 | 0.0033 | 0.1215 | 0.0073 | –0.0113 | 0.0035 | 0.1096 | 0.0012 |

| C50:3 TAG | –0.0088 | 0.0032 | 0.1611 | 0.0064 | –0.0117 | 0.0035 | 0.1018 | 0.0009 |

| C52:0 TAG | –0.0096 | 0.0031 | 0.1566 | 0.0020 | –0.0102 | 0.0034 | 0.1582 | 0.0029 |

| C52:1 TAG | –0.0089 | 0.0031 | 0.1946 | 0.0039 | –0.0116 | 0.0034 | 0.1632 | 0.0008 |

| C52:2 TAG | –0.0084 | 0.0031 | 0.1891 | 0.0075 | –0.0117 | 0.0035 | 0.1251 | 0.0009 |

| C54:1 TAG | –0.0124 | 0.0031 | 0.1712 | 5.96 × 10−5 | –0.0140 | 0.0034 | 0.1745 | 4.34 × 10−5 |

| C54:2 TAG | –0.0104 | 0.0031 | 0.1718 | 0.0008 | –0.0135 | 0.0035 | 0.1557 | 0.0001 |

| C54:3 TAG | –0.0080 | 0.0033 | 0.0897 | 0.0136 | –0.0113 | 0.0036 | 0.0836 | 0.0019 |

| C54:8 TAG | 0.0082 | 0.0032 | 0.0695 | 0.0116 | 0.0203 | 0.0036 | 0.0712 | 2.20 × 10−8 |

| C56:10 TAG | 0.0112 | 0.0032 | 0.0757 | 0.0005 | 0.0226 | 0.0036 | 0.0710 | 7.85 × 10−10 |

| C56:7 TAG | 0.0082 | 0.0032 | 0.0607 | 0.0121 | 0.0137 | 0.0036 | 0.0463 | 0.0002 |

| C56:8 TAG | 0.0150 | 0.0032 | 0.0826 | 3.90 × 10−6 | 0.0228 | 0.0036 | 0.0808 | 3.12 × 10−10 |

| C56:9 TAG | 0.0137 | 0.0032 | 0.0900 | 2.16 × 10−5 | 0.0252 | 0.0036 | 0.0917 | 3.44 × 10−12 |

| C58:11 TAG | 0.0152 | 0.0032 | 0.0882 | 3.18 × 10−6 | 0.0257 | 0.0035 | 0.0917 | 6.85 × 10−13 |

| C58:8 TAG | 0.0137 | 0.0033 | 0.0775 | 3.82 × 10−5 | 0.0241 | 0.0036 | 0.0808 | 3.87 × 10−11 |

| C58:9 TAG | 0.0172 | 0.0033 | 0.0895 | 1.69 × 10−7 | 0.0276 | 0.0035 | 0.1031 | 2.81 × 10−14 |

| C6 carnitine | –0.0087 | 0.0029 | 0.1063 | 0.0025 | –0.0113 | 0.0029 | 0.1497 | 0.0001 |

| C8 carnitine | –0.0075 | 0.0028 | 0.1263 | 0.0086 | –0.0094 | 0.0028 | 0.1850 | 0.0008 |

| C9 carnitine | –0.0104 | 0.0029 | 0.0210 | 0.0004 | –0.0120 | 0.0031 | 0.0439 | 0.0001 |

| NMMA | 0.0126 | 0.0029 | 0.0298 | 1.34 × 10−5 | 0.0126 | 0.0032 | 0.0332 | 8.28 × 10−5 |

| Pipecolic acid | 0.0072 | 0.0028 | 0.0235 | 0.0109 | 0.0151 | 0.0031 | 0.0371 | 1.51 × 10−6 |

| X1 methylnicotinamide | 0.0102 | 0.0028 | 0.0363 | 0.0003 | 0.0100 | 0.0032 | 0.0263 | 0.0017 |

| Adrenic acid | –0.0088 | 0.0035 | 0.1421 | 0.0112 | — | — | — | — |

| C18 carnitine | –0.0125 | 0.0030 | 0.0223 | 2.66 × 10−5 | — | — | — | — |

| C34:2 PE plasmalogen | –0.0089 | 0.0034 | 0.0318 | 0.0093 | — | — | — | — |

| C36:1 PC plasmalogen | –0.0123 | 0.0033 | 0.0542 | 0.0002 | — | — | — | — |

| C45:1 TAG | –0.0101 | 0.0032 | 0.1160 | 0.0017 | — | — | — | — |

| C45:2 TAG | –0.0079 | 0.0033 | 0.1163 | 0.0158 | — | — | — | — |

| C47:1 TAG | –0.0122 | 0.0032 | 0.1187 | 0.0002 | — | — | — | — |

| C47:2 TAG | –0.0107 | 0.0032 | 0.1291 | 0.0009 | — | — | — | — |

| C49:1 TAG | –0.0108 | 0.0032 | 0.1214 | 0.0007 | — | — | — | — |

| C49:2 TAG | –0.0130 | 0.0032 | 0.1342 | 5.16 × 10−5 | — | — | — | — |

| C49:3 TAG | –0.0118 | 0.0032 | 0.1471 | 0.0002 | — | — | — | — |

| C53:2 TAG | –0.0129 | 0.0031 | 0.1702 | 3.05 × 10−5 | — | — | — | — |

| C55:2 TAG | –0.0101 | 0.0031 | 0.1515 | 0.0012 | — | — | — | — |

| C55:3 TAG | –0.0088 | 0.0032 | 0.0556 | 0.0066 | — | — | — | — |

| C58:10 TAG | 0.0162 | 0.0033 | 0.0894 | 7.93 × 10−7 | — | — | — | — |

| C60:12 TAG | 0.0178 | 0.0033 | 0.0907 | 7.37 × 10−8 | — | — | — | — |

| C7 carnitine | –0.0153 | 0.0029 | 0.0877 | 1.06 × 10−7 | — | — | — | — |

| Cytosine | 0.0089 | 0.0029 | 0.0868 | 0.0020 | — | — | — | — |

| Docosahexaenoic acid | 0.0134 | 0.0034 | 0.1538 | 9.49 × 10−5 | — | — | — | — |

| Hydroxyproline | –0.0071 | 0.0029 | 0.0197 | 0.0138 | — | — | — | — |

| Thiamine | 0.0092 | 0.0028 | 0.0946 | 0.0009 | — | — | — | — |

| Asparagine | 0.0044 | 0.0028 | 0.0971 | 0.1228 | 0.0074 | 0.0031 | 0.0637 | 0.0179 |

| C14:0 SM | –0.0050 | 0.0033 | 0.0853 | 0.1248 | –0.0130 | 0.0037 | 0.0459 | 0.0004 |

| C14:1 carnitine | –0.0061 | 0.0028 | 0.1269 | 0.0302 | –0.0083 | 0.0029 | 0.1482 | 0.0048 |

| C16:0 CE | 0.0016 | 0.0034 | 0.0411 | 0.6370 | 0.0117 | 0.0037 | 0.0390 | 0.0016 |

| C16:0 LPE | 0.0014 | 0.0032 | 0.0558 | 0.6712 | 0.0089 | 0.0035 | 0.0937 | 0.0115 |

| C18:2 LPC | –0.0040 | 0.0033 | 0.1037 | 0.2271 | –0.0078 | 0.0033 | 0.1584 | 0.0208 |

| C2 carnitine | –0.0010 | 0.0029 | 0.0618 | 0.7397 | –0.0090 | 0.0030 | 0.0768 | 0.0032 |

| C22:0 ceramide d18:1 | –0.0070 | 0.0033 | 0.0990 | 0.0337 | –0.0168 | 0.0036 | 0.0848 | 2.76 × 10−6 |

| C24:0 ceramide d18:1 | –0.0048 | 0.0032 | 0.0833 | 0.1421 | –0.0110 | 0.0036 | 0.0453 | 0.0025 |

| C24:1 ceramide d18:1 | –0.0041 | 0.0032 | 0.0880 | 0.2005 | –0.0108 | 0.0037 | 0.0326 | 0.0036 |

| C24:1 SM | 0.0034 | 0.0034 | 0.0461 | 0.3064 | 0.0160 | 0.0036 | 0.0820 | 8.46 × 10−6 |

| C3 carnitine | 0.0016 | 0.0028 | 0.0927 | 0.5681 | –0.0132 | 0.0031 | 0.0587 | 2.31 × 10−5 |

| C32:0 PC | 0.0027 | 0.0032 | 0.0621 | 0.4027 | 0.0109 | 0.0036 | 0.0482 | 0.0029 |

| C34:1 DAG | –0.0064 | 0.0031 | 0.1764 | 0.0411 | –0.0090 | 0.0035 | 0.1287 | 0.0098 |

| C34:3 PE plasmalogen | –0.0058 | 0.0034 | 0.0185 | 0.0939 | –0.0137 | 0.0036 | 0.0409 | 0.0001 |

| C36:1 PC | –0.0066 | 0.0033 | 0.0455 | 0.0445 | –0.0116 | 0.0036 | 0.0440 | 0.0013 |

| C36:3 PC plasmalogen | –0.0071 | 0.0033 | 0.0898 | 0.0295 | –0.0168 | 0.0034 | 0.1029 | 1.39 × 10−6 |

| C36:3 PE | –0.0049 | 0.0033 | 0.0568 | 0.1399 | –0.0100 | 0.0036 | 0.1006 | 0.0053 |

| C36:5 PC plasmalogen A | 0.0065 | 0.0034 | 0.0109 | 0.0581 | 0.0144 | 0.0036 | 0.0580 | 7.61 × 10−5 |

| C36:5 PC plasmalogen B | –0.0068 | 0.0034 | 0.0236 | 0.0450 | –0.0112 | 0.0036 | 0.0308 | 0.0021 |

| C36:5 PE plasmalogen | –0.0056 | 0.0034 | 0.0345 | 0.0928 | –0.0100 | 0.0036 | 0.0450 | 0.0057 |

| C38:2 PE | –0.0033 | 0.0033 | 0.0421 | 0.3207 | –0.0176 | 0.0035 | 0.0575 | 8.48 × 10−7 |

| C38:4 PE | –0.0024 | 0.0033 | 0.0789 | 0.4636 | –0.0083 | 0.0036 | 0.0647 | 0.0207 |

| C38:5 PE | –0.0068 | 0.0033 | 0.0523 | 0.0380 | –0.0114 | 0.0036 | 0.0500 | 0.0018 |

| C44:0 TAG | — | — | — | — | –0.0081 | 0.0034 | 0.1448 | 0.0165 |

| C5 carnitine | 0.0027 | 0.0029 | 0.0841 | 0.3535 | –0.0081 | 0.0030 | 0.0774 | 0.0069 |

| C50:1 TAG | –0.0060 | 0.0031 | 0.1818 | 0.0541 | –0.0083 | 0.0034 | 0.1584 | 0.0150 |

| C50:2 TAG | –0.0073 | 0.0031 | 0.1923 | 0.0192 | –0.0088 | 0.0034 | 0.1373 | 0.0105 |

| C52:6 TAG | <0.0001 | 0.0032 | 0.0927 | 9.88 × 10−1 | 0.0081 | 0.0036 | 0.0356 | 0.0257 |

| C52:7 TAG | 0.0018 | 0.0032 | 0.0991 | 0.5698 | 0.0123 | 0.0036 | 0.0422 | 0.0007 |

| C54:7 TAG | 0.0047 | 0.0033 | 0.0452 | 0.1563 | 0.0144 | 0.0036 | 0.0475 | 7.49 × 10−5 |

| C58:7 TAG | 0.0069 | 0.0033 | 0.0580 | 0.0384 | 0.0112 | 0.0037 | 0.0429 | 0.0024 |

| Carnitine | 0.0030 | 0.0030 | 0.0536 | 0.3037 | –0.0112 | 0.0031 | 0.0459 | 0.0003 |

| Creatine | 0.0008 | 0.0029 | 0.0279 | 0.7890 | –0.0081 | 0.0031 | 0.0686 | 0.0077 |

Mutivariable linear regression adjusted for age at blood draw (years, continuous), BMI at blood draw (in kg/m2, continuous), fasting status at blood draw (fasted/not fasted), total caloric intake (kcal, continuous), total physical activity (metabolic equivalent–hours/wk, continuous), smoking status at blood draw (current, former, never), and case-control status. Within endpoints, metabolites were ln-transformed and then z-scored for combining with other endpoints. P values were false discovery rate corrected to account for multiple comparisons. P values < 0.05 indicate statistical significant associations. Blanks indicate that the metabolite was not measured. CE, cholesteryl ester; DAG, diacylglycerol; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE, lysophosphoethanolamine; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study; NMMA, N-methylmalonamic acid; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphoethanolamine; PS, phosphatidylserine; SM, sphingomyelin; TAG, triacylglycerol.

Among the significant metabolites, 63 metabolites were associated with the AHEI in both studies. However, some additional metabolites, even if they did not reach the P value threshold, had the same direction of association, almost identical magnitude, and similar R2 between the 2 cohorts. The identified compounds mostly belonged to lipid molecules, but the AHEI was significantly associated with some amino acids and vitamins in the NHS or HPFS.

Considering components rather than the AHEI score, 72 metabolites were added while 104 metabolites were the same as those associated with the AHEI score (Supplemental Table 1). The correlations between all measured lipids with the AHEI and its components are shown in Supplemental Figures 2 and 3. Regarding this analysis, metabolites that were strongly and directly correlated with the AHEI score were also highly directly correlated with omega-3 in the NHS [C60:12 triacylglycerols (TAGs)] and in the HPFS (C58:11 TAG). This finding is consistent with the regression results.

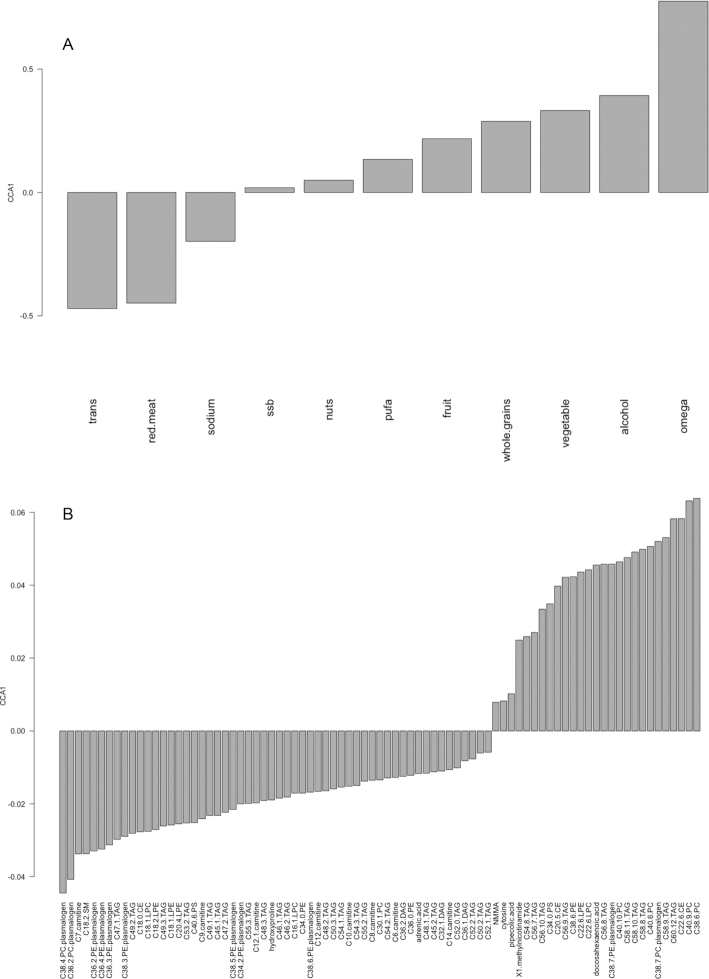

Healthy/unhealthy AHEI components and AHEI-associated metabolites

In the NHS, CCA analysis included 11 AHEI components and all 83 metabolites, which were significantly associated with the AHEI in the linear regression models. Based on CCA1, which separated healthy compared with unhealthy AHEI components, we defined healthy and unhealthy metabolites. Similar to the healthy and unhealthy AHEI components, metabolites with a negative loading on CCA1 fall into the unhealthy metabolite group and those with a positive loading are categorized as healthy metabolites (Figure 1). We observed that 27 metabolites were associated with healthy AHEI components, including ω-3 and whole grains, while 56 metabolites were related to the unhealthy AHEI components such as red meat, trans fatty acids, and sodium (Supplemental Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

The pattern of metabolites related to Alternate Healthy Eating Index components across the population: the barplot of CCA1 for the dietary factors (A) and the barplot of CCA1 for the metabolites (B) in the Nurses’ Health Study. CCA, canonical correspondence analysis; CE, cholesteryl ester; DAG, diacylglycerol; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE, lysophosphoethanolamine; NMMA, N-methylmalonamic acid; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphoethanolamine; PS, phosphatidylserine; SM, sphingomyelin; ssb, sugar-sweetened beverages; TAG, triacylglycerol; trans, trans fats.

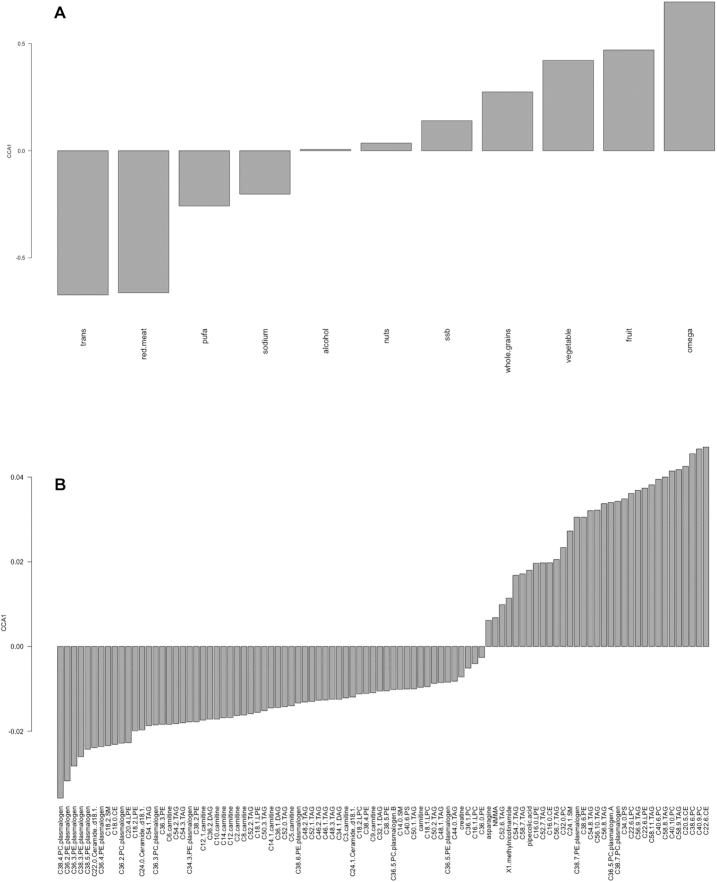

Likewise, in the HPFS, CCA analysis of the 96 metabolites that were associated with the AHEI in the multiple linear regression model was examined to address their associations with individual AHEI components and CCA1 separated healthy AHEI components from unhealthy ones, defining healthy and unhealthy metabolites (Figure 2). Among the AHEI-associated metabolites, 33 were linked to the healthy components, while 63 were related to the unhealthy ones (Supplemental Table 2). In particular, long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs), containing TAGs and phospholipids, were identified as markers of healthy diet and plasmalogens and acylcarnitines as markers of unhealthy diet. When comparing these 2 groups of metabolites across the cohorts, we noted 23 healthy and 40 unhealthy metabolites that overlapped between the NHS and HPFS (Supplemental Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

The pattern of metabolites related to Alternate Healthy Eating Index components across the population, the barplot of CCA1 for the dietary factors (A), and the barplot of CCA1 for the metabolites (B) in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. CCA, canonical correspondence analysis; CE, cholesteryl ester; DAG, diacylglycerol; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE, lysophosphoethanolamine; NMMA, N-methylmalonamic acid; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphoethanolamine; PS, phosphatidylserine; SM, sphingomyelin; ssb, sugar-sweetened beverages; TAG, triacylglycerol; trans, trans fats.

PUFAs were the only AHEI component that differed between the NHS and HPFS (with opposite directions of association in Figures 1 and 2); however, all other components had the same direction of association, with some variance in their magnitudes.

Metabolite groups associated with AHEI components

PCA identified 12 PCs in the NHS and 14 PCs in the HPFS consisting of correlated (within a PC) metabolites. Metabolites were consolidated into factors that reflected primary lipid classes (Tables 4 and 5). In particular, the first 2 factors reflected highly saturated and highly unsaturated long-chain TAGs, likely corresponding to differences in dietary fatty acid intake. Factors 10, 11, and 12 in the NHS and factors 9, 12, 13, and 14 in the HPFS did not include any metabolite with a factor loading ≥0.5, so they are not presented in Tables 4 and 5, respectively.

TABLE 4.

Nine factors identified from exploratory factor analysis following principal components analysis that account for 82% of the variance in metabolite levels in the Nurses’ Health Study1

| Factor 1 (Variance = 26%) | Factor 2 (Variance = 20%) | Factor 3 (Variance = 12%) | Factor 4 (Variance = 8.77%) | Factor 5 (Variance = 5.61%) | Factor 6 (Variance = 3.66%) | Factor 7 (Variance = 2.70%) | Factor 8 (Variance = 2.04%) | Factor 9 (Variance = 1.63%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Loading | ID | Loading | ID | Loading | ID | Loading | ID | Loading | ID | Loading | ID | Loading | ID | Loading | ID | Loading |

| C48:1 TAG | 0.98 | C56:8 TAG | 0.93 | C34:2 PE plasmalogen | 0.91 | C10 carnitine | 0.94 | C52:2 TAG | 0.55 | C18:1 LPC | 0.78 | C22:6 CE | 0.62 | C40:6 PS | 0.62 | C18:0 CE | 0.58 |

| C48:1 TAG | 0.98 | C56:8 TAG | 0.93 | C34:2 PE plasmalogen | 0.91 | C10 carnitine | 0.94 | C52:2 TAG | 0.55 | C18:1 LPC | 0.78 | C22:6 CE | 0.62 | C36:0 PE | 0.58 | C18:0 CE | 0.58 |

| C52:0 TAG | 0.86 | C58:8 TAG | 0.86 | C36:2 PE plasmalogen | 0.93 | C6 carnitine | 0.92 | C54:2 TAG | 0.62 | C16:1 LPC | 0.70 | C38:6 PC | 0.55 | ||||

| C52:1 TAG | 0.89 | C56:9 TAG | 0.97 | C36:2 PC plasmalogen | 0.63 | C8 carnitine | 0.93 | C54:3 TAG | 0.87 | C22:6 LPC | 0.52 | C40:9 PC | 0.54 | ||||

| C52:2 TAG | 0.72 | C56:7 TAG | 0.80 | C38:4 PC plasmalogen | 0.60 | C12 carnitine | 0.92 | C36:2 DAG | 0.67 | C18:1 LPE | 0.76 | C22:6 LPC | 0.51 | ||||

| C48:2 TAG | 0.97 | C58:9 TAG | 0.92 | C38:3 PE plasmalogen | 0.69 | C14 carnitine | 0.81 | C53:2 TAG | 0.63 | C18:2 LPE | 0.76 | ||||||

| C54:1 TAG | 0.80 | C58:10 TAG | 0.95 | C38:5 PE plasmalogen | 0.84 | C7 carnitine | 0.78 | C55:2 TAG | 0.52 | C20:4 LPE | 0.79 | ||||||

| C54:2 TAG | 0.68 | C60:12 TAG | 0.92 | C38:6 PE plasmalogen | 0.84 | C9 carnitine | 0.55 | C55:3 TAG | 0.84 | ||||||||

| C48:3 TAG | 0.91 | C20:5 CE | 0.59 | C36:3 PE plasmalogen | 0.93 | C12:1 carnitine | 0.90 | ||||||||||

| C50:3 TAG | 0.80 | C38:6 PC | 0.79 | C36:4 PE plasmalogen | 0.88 | adrenic acid | 0.64 | ||||||||||

| C32:1 DAG | 0.90 | C40:6 PC | 0.67 | ||||||||||||||

| C36:1 DAG | 0.81 | C40:10 PC | 0.77 | ||||||||||||||

| C36:2 DAG | 0.62 | C40:9 PC | 0.80 | ||||||||||||||

| C40:6 PS | 0.61 | C38:6 PE | 0.65 | ||||||||||||||

| C46:1 TAG | 0.97 | C22:6 LPC | 0.52 | ||||||||||||||

| C46:2 TAG | 0.95 | C56:10 TAG | 0.93 | ||||||||||||||

| C49:1 TAG | 0.92 | C54:8 TAG | 0.82 | ||||||||||||||

| C49:2 TAG | 0.93 | C58:11 TAG | 0.97 | ||||||||||||||

| C47:2 TAG | 0.97 | C38:7 PC plasmalogen | 0.61 | ||||||||||||||

| C45:1 TAG | 0.95 | C38:7 PE plasmalogen | 0.68 | ||||||||||||||

| C47:1 TAG | 0.94 | C22:6 LPE | 0.68 | ||||||||||||||

| C49:3 TAG | 0.87 | C34:0 PS | 0.71 | ||||||||||||||

| C53:2 TAG | 0.67 | docosahexaenoic acid | 0.64 | ||||||||||||||

| C55:2 TAG | 0.77 | ||||||||||||||||

| C45:2 TAG | 0.94 | ||||||||||||||||

Only metabolites with a factor load ≥0.5 were reported as composing a given factor. Principal component analysis and exploratory factor analysis were used. CE, cholesteryl ester; DAG, diacylglycerol; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE, lysophosphoethanolamine; PC, phosphatidylcholine;PE, phosphoethanolamine; PS, phosphatidylserine; TAG, triacylglycerol.

TABLE 5.

Factors identified from exploratory factor analysis following principal components analysis and accounting for 81% of the variance in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study1

| Factor 1 (Variance = 0.26) | Factor 2 (Variance = 0.16) | Factor 3 (Variance = 0.12) | Factor 4 (Variance = 0.078) | Factor 5 (Variance = 0.054) | Factor 6 (Variance = 0.039) | Factor 7 (Variance = 0.025) | Factor 8 (Variance = 0.020) | Factor 10 (Variance = 0.015) | Factor 11 (Variance = 0.015) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Loading | ID | Loading | ID | Loading | ID | Loading | ID | Loading | ID | Loading | ID | Loading | ID | Loading | ID | Loading | ID | Loading |

| C22:0 Ceramide d18 1 | 0.53 | C16:0 CE | 0.59 | C38:2 PE | 0.51 | C56:8 TAG | 0.80 | C2 carnitine | 0.68 | C18:1 LPC | 0.89 | C18:2 SM | 0.57 | C22:0 Ceramide d18 1 | 0.69 | C38:5 PE | 0.65 | C20:4 LPE | 0.63 |

| C48:1 TAG | 0.94 | C56:8 TAG | 0.52 | C36:2 PE plasmalogen | 0.82 | C58:8 TAG | 0.53 | C10 carnitine | 0.94 | C16:1 LPC | 0.66 | C24:1 Ceramide d18 1 | 0.69 | ||||||

| C50:1 TAG | 0.96 | C58:8 TAG | 0.62 | C36:5 PC plasmalogen B | 0.72 | C52:6 TAG | 0.73 | C6 carnitine | 0.86 | C18:2 LPC | 0.83 | C24:0 Ceramide d18 1 | 0.72 | ||||||

| C52:0 TAG | 0.89 | C56:9 TAG | 0.55 | C36:2 PC plasmalogen | 0.55 | C54:7 TAG | 0.85 | C8 carnitine | 0.91 | C22:6 LPC | 0.50 | ||||||||

| C52:1 TAG | 0.96 | C58:9 TAG | 0.59 | C36:3 PC plasmalogen | 0.68 | C56:9 TAG | 0.81 | C14:1 carnitine | 0.93 | C16:0 LPE | 0.61 | ||||||||

| C52:2 TAG | 0.91 | C20:5 CE | 0.81 | C38:4 PC plasmalogen | 0.57 | C56:7 TAG | 0.84 | C12 carnitine | 0.95 | C18:1 LPE | 0.79 | ||||||||

| C48:2 TAG | 0.95 | C22:6 CE | 0.85 | C34:3 PE plasmalogen | 0.89 | C58:9 TAG | 0.65 | C14 carnitine | 0.76 | C18:2 LPE | 0.74 | ||||||||

| C50:2 TAG | 0.96 | C32:0 PC | 0.61 | C38:3 PE plasmalogen | 0.70 | C58:7 TAG | 0.68 | C9 carnitine | 0.52 | C20:4 LPE | 0.60 | ||||||||

| C54:1 TAG | 0.90 | C38:6 PC | 0.92 | C38:5 PE plasmalogen | 0.87 | C56:10 TAG | 0.70 | C12:1 carnitine | 0.94 | ||||||||||

| C54:2 TAG | 0.89 | C40:6 PC | 0.81 | C38:6 PE plasmalogen | 0.86 | C52:7 TAG | 0.75 | ||||||||||||

| C54:3 TAG | 0.71 | C40:10 PC | 0.81 | C36:5 PE plasmalogen | 0.79 | C54:8 TAG | 0.77 | ||||||||||||

| C48:3 TAG | 0.92 | C40:9 PC | 0.92 | C36:3 PE plasmalogen | 0.89 | C58:11 TAG | 0.67 | ||||||||||||

| C50:3 TAG | 0.91 | C38:6 PE | 0.62 | C36:4 PE plasmalogen | 0.84 | ||||||||||||||

| C52:6 TAG | 0.52 | C22:6 LPC | 0.71 | ||||||||||||||||

| C32:1 DAG | 0.95 | C54:8 TAG | 0.50 | ||||||||||||||||

| C34:1 DAG | 0.92 | C58:11 TAG | 0.61 | ||||||||||||||||

| C36:1 DAG | 0.95 | C36:5 PC plasmalogen A | 0.73 | ||||||||||||||||

| C36:2 DAG | 0.86 | C38:7 PC plasmalogen | 0.82 | ||||||||||||||||

| C36:1 PC | 0.61 | C38:7 PE plasmalogen | 0.77 | ||||||||||||||||

| C38:4 PE | 0.71 | C22:6 LPE | 0.74 | ||||||||||||||||

| C36:3 PE | 0.61 | C24:1 SM | 0.69 | ||||||||||||||||

| C38:5 PE | 0.56 | C34:0 PS | 0.79 | ||||||||||||||||

| C40:6 PS | 0.56 | ||||||||||||||||||

| C46:1 TAG | 0.92 | ||||||||||||||||||

| C46:2 TAG | 0.92 | ||||||||||||||||||

| C44:0 TAG | 0.84 | ||||||||||||||||||

Only metabolites with a factor load ≥0.5 were reported as composing a given factor. Principal component analysis and exploratory factor analysis were used. CE, cholesteryl ester; DAG, diacylglycerol; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE, lysophosphoethanolamine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphoethanolamine; PS, phosphatidylserine; SM, sphingomyelin; TAG, triacylglycerol.

We examined the association of the AHEI components with metabolite factors (Table 6 and Table 7). Briefly, PUFA in both cohorts was negatively associated with factor 1 (composed of highly saturated long-chain TAGs). In the NHS, alcohol, ω-3, and PUFA were positively and trans fat was negatively associated with factor 2, which was composed of highly unsaturated long-chain TAGs and plasmalogens with highly unsaturated fatty acids. In the HPFS, however, alcohol and ω-3 were positively and red meat and trans fat were negatively related to factor 2. We also observed that factor 3 (composed of plasmalogens) was linked to red and processed meat in the NHS and red and processed meat and sugar-sweetened beverages in the HPFS. Furthermore, our findings revealed that the factor consisting of acylcarnitine derivatives (factor 4) was associated with alcohol only in men.

TABLE 6.

Association of AHEI components with AHEI-associated metabolite factors in the Nurses’ Health Study1

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Factor 6 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value |

| Healthy AHEI components | ||||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol | –0.03 | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.15 | 0.03 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.95 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.25 | –0.19 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Fruit | –0.01 | 0.03 | 0.68 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.47 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.79 | –0.04 | 0.03 | 0.20 |

| Grains | –0.03 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.09 | –0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | –0.01 | 0.03 | 0.79 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.85 |

| Nuts and legumes | –0.16 | 0.07 | 0.02 | –0.15 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.46 | –0.03 | 0.07 | 0.61 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.89 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.11 |

| ω-3 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.87 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.69 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.33 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.50 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PUFA | –0.08 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.02 | <0.001 | –0.02 | 0.02 | 0.44 | –0.02 | 0.02 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.56 | –0.02 | 0.02 | 0.34 |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages | –0.03 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.09 | –0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | –0.01 | 0.03 | 0.79 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.85 |

| Vegetables | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.74 | –0.01 | 0.02 | 0.47 | –0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | –0.03 | 0.02 | 0.07 | –0.01 | 0.02 | 0.73 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.23 |

| Unhealthy AHEI components | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sodium | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.07 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.41 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.19 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.06 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.79 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| Red and processed meat | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.08 | –0.08 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.09 | –0.05 | 0.05 | 0.26 |

| Trans fatty acids | –7.09 | 6.08 | 0.24 | –17.63 | 5.86 | <0.001 | –11.65 | 6.13 | 0.06 | 9.40 | 6.14 | 0.13 | 2.33 | 5.93 | 0.69 | 9.79 | 6.09 | 0.11 |

| Factor 7 | Factor 8 | Factor 9 | Factor 10 | Factor 11 | Factor 12 | |||||||||||||

| Characteristic | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value |

| Healthy AHEI components | ||||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol | 0.13 | 0.03 | <0.001 | –0.05 | 0.03 | 0.11 | –0.18 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.87 | 0.17 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.33 |

| Fruit | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.10 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.88 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.92 |

| Grains | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.71 | –0.08 | 0.03 | 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.45 | –0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | –0.05 | 0.03 | 0.10 |

| Nuts and legumes | –0.21 | 0.06 | <0.001 | –0.02 | 0.06 | 0.73 | –0.22 | 0.06 | <0.001 | –0.03 | 0.06 | 0.67 | –0.03 | 0.06 | 0.69 | –0.08 | 0.06 | 0.19 |

| ω-3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.37 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.54 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.03 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.32 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PUFA | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.67 | –0.07 | 0.02 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.82 | –0.01 | 0.02 | 0.60 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.80 | –0.01 | 0.02 | 0.76 |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.71 | –0.08 | 0.03 | 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.45 | –0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | –0.05 | 0.03 | 0.10 |

| Vegetables | –0.01 | 0.02 | 0.41 | –0.01 | 0.02 | 0.41 | –0.01 | 0.02 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.54 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.97 |

| Unhealthy AHEI components | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sodium | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.33 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.89 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.74 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.16 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.03 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.41 |

| Red and processed meat | –0.05 | 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.54 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Trans fatty acids | –7.94 | 5.79 | 0.17 | 1.09 | 5.82 | 0.85 | 4.88 | 5.72 | 0.39 | –1.63 | 5.73 | 0.78 | –5.07 | 5.71 | 0.37 | –6.52 | 5.65 | 0.25 |

Multivariable linear regression adjusted for the AHEI components score without the component of interest. P values were false discovery rate corrected to account for multiple comparisons. P values < 0.05 indicate statistical significant associations. Units: alcohol = drinks/d; fruit = servings/d; grains = g/d; nuts and legumes = servings/d; ω-3 = mg/d; PUFA = percentage of energy, sugar-sweetened beverages = servings/d; vegetables = servings/d; sodium = mg/d; red and processed meat = servings/d; trans fatty acids = percentage of energy. AHEI, Alternate Healthy Eating Index.

TABLE 7.

Association of AHEI components with AHEI-associated metabolite factors in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study1

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Factor 6 | Factor 7 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value |

| Healthy AHEI components | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.1066 | 0.11 | 0.02 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.2241 | –0.08 | 0.03 | 0.0014 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.0012 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.3332 | –0.15 | 0.03 | <0.0001 |

| Fruit | –0.01 | 0.03 | 0.7482 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.1645 | –0.02 | 0.03 | 0.4801 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.1168 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.3761 | –0.02 | 0.03 | 0.5758 | –0.02 | 0.03 | 0.4846 |

| Grains | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.2412 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.3725 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0142 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.2343 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.4538 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.3209 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.9660 |

| Nuts and legumes | –0.09 | 0.07 | 0.2150 | –0.18 | 0.07 | 0.0072 | –0.15 | 0.07 | 0.0383 | –0.11 | 0.07 | 0.1247 | –0.05 | 0.07 | 0.5073 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.1454 | –0.02 | 0.07 | 0.7296 |

| ω-3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.3899 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.0001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.4393 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.4403 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0515 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0978 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0074 |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.9343 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.6043 | –0.10 | 0.03 | 0.0022 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.4236 | –0.02 | 0.03 | 0.4831 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.1249 | –0.02 | 0.03 | 0.5457 |

| Vegetables | –0.03 | 0.02 | 0.2042 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.2596 | –0.01 | 0.02 | 0.4736 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.0263 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.8480 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.0034 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.4583 |

| Unhealthy AHEI components | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sodium | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0856 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.4479 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.8091 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.2779 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.3922 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.4961 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.7487 |

| Red and processed meat | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.7167 | –0.17 | 0.05 | 0.0005 | 0.28 | 0.05 | <0.0001 | –0.12 | 0.05 | 0.0232 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.2497 | –0.10 | 0.05 | 0.0704 | –0.03 | 0.05 | 0.6008 |

| PUFA | –0.06 | 0.02 | 0.0102 | –0.02 | 0.02 | 0.2967 | –0.01 | 0.02 | 0.5830 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.0688 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.8922 | –0.02 | 0.02 | 0.4349 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.3611 |

| Trans fatty acids | 8.14 | 6.19 | 0.1886 | –27.22 | 5.64 | <0.0001 | 2.10 | 5.96 | 0.7249 | 5.32 | 6.08 | 0.3817 | 13.97 | 6.07 | 0.0215 | 26.73 | 6.13 | <0.0001 | 10.37 | 5.84 | 0.0761 |

| Factor 8 | Factor 9 | Factor 10 | Factor 11 | Factor 12 | Factor 13 | Factor 14 | |||||||||||||||

| Characteristic | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value |

| Healthy AHEI components | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol | –0.02 | 0.03 | 0.4356 | –0.02 | 0.03 | 0.5336 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.0014 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.0857 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.4326 | –0.02 | 0.03 | 0.4510 | 0.11 | 0.02 | <0.0001 |

| Fruit | –0.04 | 0.03 | 0.1176 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.8630 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.4009 | –0.01 | 0.03 | 0.5856 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.2383 | –0.05 | 0.03 | 0.0609 | –0.03 | 0.03 | 0.2534 |

| Grains | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0085 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.9177 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.1047 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.1142 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.2342 | –0.01 | <0.001 | 0.0002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.3164 |

| Nuts and legumes | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.0154 | –0.05 | 0.07 | 0.4590 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.6174 | –0.15 | 0.07 | 0.0245 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.9080 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.0041 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.1067 |

| ω-3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.8543 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.8927 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.8915 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0004 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.4070 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0386 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0808 |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages | –0.03 | 0.03 | 0.3328 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.9514 | –0.04 | 0.03 | 0.2007 | –0.02 | 0.03 | 0.5658 | –0.01 | 0.03 | 0.7978 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.9519 | –0.04 | 0.03 | 0.1446 |

| Vegetables | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.7879 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.8636 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.1432 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.4763 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.4434 | –0.01 | 0.02 | 0.6817 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.1706 |

| Unhealthy AHEI components | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sodium | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.6128 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.2980 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.9802 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.9548 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.3563 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.1956 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.6236 |

| Red and processed meat | –0.07 | 0.05 | 0.1712 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.2533 | –0.02 | 0.05 | 0.7375 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.0006 | –0.13 | 0.05 | 0.0117 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.0025 | –0.10 | 0.05 | 0.0383 |

| PUFA | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.1671 | –0.07 | 0.02 | 0.0025 | –0.01 | 0.02 | 0.5486 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.6744 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.0029 | –0.03 | 0.02 | 0.1242 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.3903 |

| Trans fatty acids | 8.38 | 5.92 | 0.1568 | 7.07 | 5.90 | 0.2313 | 10.88 | 5.97 | 0.0684 | –15.49 | 5.80 | 0.0077 | 7.00 | 5.88 | 0.2345 | –5.95 | 5.83 | 0.3079 | 1.97 | 5.66 | 0.7278 |

Multivariable linear regression adjusted for the AHEI components score without the component of interest. P values were false discovery rate corrected to account for multiple comparisons. P values < 0.05 indicate statistical significant associations. Units: alcohol = drinks/d; fruit = servings/d; grains = g/d; nuts and legumes = servings/d; ω-3 = mg/d; PUFA = percentage of energy, sugar-sweetened beverages = servings/d; vegetables = servings/d; sodium = mg/d; red and processed meat = servings/d; trans fatty acids = percentage of energy. AHEI, Alternate Healthy Eating Index.

Metabolite score for the FFQ-based AHEI

As shown in Table 8, the AHEI was significantly associated (P < 0.05) with 39 metabolites in the stepwise analysis in both men and women (R2 = 0.33, multivariable-adjusted R2 = 0.29). The identified metabolites included 2 lysophosphatidylcholines, 2 lysophosphatidylethanolamines, 4 phosphatidylcholines, 1 phosphatidylethanolamine, 2 sphingomyelins, 8 triacylglycerols, 2 diacylglycerols, 1 cholesteryl ester, 6 plasmalogens, 5 acylcarnitines, 3 amino acids (glycine, leucine, and threonine), N-methylmalonamic acid, and trimethylamine-N-oxide. The R2 and adjusted R2 values, derived from the model run in the validation data set, were 0.28 and 0.22, respectively. When we set the significance level at 0.01, the AHEI was significantly associated with 21 metabolites (data not shown) with the R2 values of 0.25 and 0.21 (adjusted) in the validation data set.

TABLE 8.

Metabolite-derived Alternate Healthy Eating Index predictors in the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study divided into discovery and validation data sets (P < 0.05 in the discovery data set)1

| Discovery set (n = 1758) | Validation set (n = 753) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | β | SE | P value | β | SE | P value |

| (Intercept) | 58.63 | 3.32 | 8.45 × 10−62 | 50.88 | 5.12 | 3.37 × 10−21 |

| C10 carnitine | –5.59 | 2.00 | 0.0053 | –3.25 | 3.30 | 0.3257 |

| C12:1 carnitine | –2.45 | 1.15 | 0.0335 | –1.60 | 1.72 | 0.3534 |

| C12 carnitine | 3.79 | 1.18 | 0.0013 | 2.86 | 1.65 | 0.0836 |

| C18:1 LPE | 2.11 | 0.87 | 0.0158 | –0.05 | 1.23 | 0.9669 |

| C18:2 LPC | –5.53 | 1.02 | 7.92 × 10−8 | –0.32 | 1.49 | 0.8292 |

| C18:2 SM | –2.86 | 0.46 | 7.78 × 10−10 | –1.15 | 0.76 | 0.1330 |

| C18:3 CE | 2.05 | 0.63 | 0.0011 | 0.91 | 0.71 | 0.2021 |

| C2 carnitine | –1.39 | 0.58 | 0.0173 | –0.07 | 0.77 | 0.9269 |

| C20:4 LPE | –1.31 | 0.62 | 0.0346 | –0.67 | 0.95 | 0.4785 |

| C22:1 SM | 2.19 | 0.56 | 0.0001 | 0.25 | 0.86 | 0.7735 |

| C22:6 LPC | 5.47 | 0.85 | 1.67 × 10−10 | 1.33 | 1.12 | 0.2339 |

| C32:1 PC | –4.63 | 1.21 | 0.0001 | –3.31 | 1.27 | 0.0093 |

| C34:1 PC plasmalogen A | 1.90 | 0.61 | 0.0019 | 3.40 | 0.99 | 0.0006 |

| C34:2 PC plasmalogen | 1.42 | 0.67 | 0.0354 | –0.53 | 1.04 | 0.6120 |

| C36:2 DAG | 5.92 | 2.31 | 0.0106 | –0.98 | 2.92 | 0.7383 |

| C36:2 PE | 3.15 | 1.11 | 0.0048 | 2.99 | 1.46 | 0.0419 |

| C36:3 DAG | –5.14 | 1.99 | 0.0099 | 0.45 | 2.83 | 0.8732 |

| C36:4 PC A | 1.53 | 0.66 | 0.0210 | 0.62 | 1.08 | 0.5697 |

| C36:4 PC B | 3.22 | 0.81 | 8.13 × 10−5 | 1.56 | 1.03 | 0.1297 |

| C36:5 PE plasmalogen | 1.88 | 0.57 | 0.0010 | –1.26 | 0.89 | 0.1585 |

| C38:3 PC | –1.50 | 0.62 | 0.0154 | –0.20 | 1.03 | 0.8479 |

| C38:3 PE plasmalogen | –1.93 | 0.46 | 3.13 × 10−5 | –0.91 | 0.66 | 0.1714 |

| C38:4 PC plasmalogen | –2.12 | 0.58 | 0.0003 | –3.48 | 0.88 | 7.95 × 10−5 |

| C38:5 PE | –1.78 | 0.70 | 0.0118 | –1.35 | 1.07 | 0.2062 |

| C38:7 PE plasmalogen | –3.28 | 0.97 | 0.0008 | 0.63 | 1.19 | 0.5939 |

| C48:0 TAG | 2.87 | 1.23 | 0.0199 | 1.12 | 1.73 | 0.5169 |

| C48:2 TAG | –9.81 | 2.56 | 0.0001 | –0.97 | 2.30 | 0.6741 |

| C50:4 TAG | 4.34 | 1.53 | 0.0046 | 0.62 | 2.32 | 0.7886 |

| C54:1 TAG | –2.43 | 1.20 | 0.0427 | –2.26 | 1.43 | 0.1141 |

| C54:3 TAG | 3.22 | 1.53 | 0.0354 | 1.22 | 1.55 | 0.4296 |

| C54:7 TAG | –1.42 | 0.63 | 0.0251 | –2.04 | 1.15 | 0.0755 |

| C56:8 TAG | 2.96 | 1.23 | 0.0162 | –1.40 | 1.79 | 0.4317 |

| C58:11 TAG | –2.05 | 0.98 | 0.0372 | 3.73 | 1.60 | 0.0197 |

| C8 carnitine | 3.64 | 1.69 | 0.0316 | 1.51 | 2.83 | 0.5931 |

| Glycine | 0.77 | 0.34 | 0.0227 | 0.03 | 0.55 | 0.9604 |

| Leucine | –0.86 | 0.44 | 0.0492 | 0.19 | 0.57 | 0.7405 |

| NMMA | 1.21 | 0.32 | 0.0002 | 0.93 | 0.52 | 0.0746 |

| Threonine | –1.29 | 0.36 | 0.0003 | –0.42 | 0.55 | 0.4522 |

| Trimethylamine N-oxide | 0.88 | 0.30 | 0.0037 | 0.13 | 0.53 | 0.8067 |

Stepwise multivariable regression. CE, cholesteryl ester; DAG, diacylglycerol; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; LPE, lysophosphoethanolamine; NMMA, N-methylmalonamic acid; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphoethanolamine; SM, sphingomyelin; TAG, triacylglycerol.

We observed a significant moderate correlation between the predicted and FFQ-based AHEI scores of r = 0.40, P < 0.001 in the discovery data set and r = 0.31, P < 0.001 in the validation data set. Partial correlations adjusting for age and BMI were similar (r = 0.40, P < 0.001 and r = 0.29, P < 0.001) (not reported in Table 8).

Discussion

In our main analysis, we identified 83 metabolites in the NHS and 96 metabolites in the HPFS that were associated with the AHEI dietary quality index, including fatty acids, acylcarnitines, and amino acid derivatives, with 63 metabolites overlapping between men and women. In a secondary analysis, we found that healthy and unhealthy metabolite clusters largely overlapped between men and women. Furthermore, our results showed that unhealthy AHEI components were associated with highly saturated TAGs, plasmalogens, and acylcarnitines while healthy AHEI components were related to clusters of highly unsaturated TAGs. Furthermore, the metabolite score, which was based mostly on different lipid classes and amino acids, showed a significant correlation with the FFQ-based AHEI in our validation data set, suggesting that it may be used as an indicator of diet quality.

Adherence to healthy diet, reflected from higher AHEI score, was associated with lower risk of cardiovascular incidence and death from cardiovascular diseases (40–42). Research showed lipid species composed primarily of saturated or monounsaturated fatty acids were positively linked to cardiovascular death (43). Likewise, in our study, lipids with the number of carbon-carbon double bonds <5 regardless of the number of carbon atoms in the fatty acid chain(s) had inverse associations with the AHEI. In addition, plasmalogens with <7 double bonds in the fatty acid chains were inversely associated with the AHEI. While earlier research focused on the beneficial effects of PUFA (44), our study has documented that the number of double bonds in the fatty acid chains may influence the final biological activity of lipid compounds. As fatty acid desaturation is accomplished by enzymatic reactions in the body (45), we hypothesize that the healthy dietary pattern may lead to the activation of these enzyme systems. Although our metabolomics data do not allow us to infer fatty acids, the above idea about the number of double bonds in the fatty acid chains might represent one possible explanation underlying the link between diet quality and the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Similar comparison about the number of double bonds of fatty acid chains in ceramide was done in the study by Wang et al. (46), in which difference in ceramide fatty chains influenced the risk of CVD.

Prior studies of metabolomics and dietary patterns demonstrated that plasma lipid profiles were the dominant metabolites linked to dietary patterns (16, 18). Although a Mediterranean dietary intervention did not change ceramide concentrations in a recent study, it mitigated the adverse relation of higher levels of ceramide to risk of CVDs (46). Regarding our findings, high diet quality was positively associated with TAGs with long-chain acyl substituents. Interestingly, these specific metabolites (factors 1 and 2 in our study) were directly related to healthy AHEI components such as ω-3 and inversely associated with unhealthy AHEI components, including trans fats. Consistent with our results, past reports have revealed that very long-chain saturated fatty acids in plasma might be linked to healthy circulating lipid patterns, which contributed to a reduced risk of coronary heart disease (47). Likewise, higher concentrations of DHA-containing TAGs and phospholipids were associated with a lower risk of progression from coronary artery disease to coronary atherosclerosis in women (48). Therefore, TAGs, particularly those that contain LCFAs, may serve as potential nutritional biomarkers representing a high diet quality. Because of our metabolomics finding that TAGs containing LCFAs were positively associated with the AHEI score, we used data from a previous publication to examine correlations between specific fatty acids measured by GC and AHEI score (47). We found that plasma levels of long-chain ω-3 fatty acids were moderately correlated with participants’ AHEI score (r = 0.29). This finding provides support that triglycerides containing LCFAs may be a potential biomarker for a healthy diet. We also noted a weak inverse correlation (r = –0.15) between long-chain ω-6 fatty acids (mostly arachidonic acid) and the AHEI score, suggesting that the greater specificity of the GC method for fatty acids may provide a better indicator of this component of diet quality than the metabolomics analysis. It is interesting that the TAG patterns that were categorized as healthy metabolites in our study overlapped with the metabolites that were found to be associated with flavonoid intake (49), and thus our findings may not be entirely driven by fat intake but could also be explained by other healthy dietary components, such as flavonoids.

We observed that some metabolites, including acylcarnitines and plasmalogens, were negatively associated with the AHEI. We also observed positive associations between PCA-derived factors consisting of these metabolites and dietary components contributing to lower dietary quality scores. For example, red and processed meat was positively related to the plasmalogen factor (factor 3) in both the NHS and the HPFS. In addition, in the HPFS, an increased intake of alcohol and trans fat corresponded with higher plasma acylcarnitines (including C12 and C14 carnitine). It is currently unknown if adherence to high diet quality through a reduced intake of red and processed meat in men and women may lead to a decreased risk of chronic disorders by decreasing circulatory plasmalogens. However, elevated levels of acylcarnitine by-products in the body might induce activation of proinflammatory pathways (50). Our results suggest that acylcarnitines could play a role in the relation between low diet quality and an increased risk of chronic diseases. This observation tends to confirm findings from previous research indicating an association between carnitine levels and high intakes of red meat; whether carnitine is causally related to risk of CVD or is simply a biomarker of intake remains unclear (51). The intake of red meat was positively associated with acylcarnitine C18:0 (52). Also, increased levels of serum even‐chained acylcarnitines were found to be associated with higher CVD events (53).

Our CCA analysis highlighted metabolite profiles of healthy and unhealthy AHEI components. Although several metabolite associations differed between the 2 cohorts of men and women, 23 healthy and 40 unhealthy metabolites overlapped between the NHS and HPFS. Consistent with our previous findings, high-quality diets were associated with increased levels of circulating LCFA-containing TAGs and phospholipids, as discussed earlier, the potential biomarkers of high AHEI scores that may be associated with direct health benefits. However, low diet quality was associated with higher levels of some plasmalogens and acylcarnitines, which, as described above, are biologically plausible factors related to adverse health outcomes.

In addition, CCA showed a sex-related difference of metabolites associated with PUFA intake (PUFAs except EPA and DHA). In particular, our results suggest that PUFA intake was linked to healthy metabolites in women but unhealthy metabolites in men. The reason for this difference is unclear and could be a chance finding.

We replicated previous findings of a positive association between red meat intake and plasma acylcarnitine (16). It has been suggested that D, L isomers of C12 or C14 carnitine are involved in proinflammatory signaling (either in the expression of proinflammatory cytokines or in the phosphorylation of c-Jun amino-terminal kinase and extracellular signal–regulated kinase). Our findings on dietary pattern–metabolite associations were in contrast to those of studies conducted in female twins (54), male smokers (18), and female participants in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (55). In the study by Pallister et al. (54), for example, trans-4-hydroxyproline was characterized as a marker of red meat consumption and phenolic compounds as markers of fruit intake. A recent publication demonstrated that diet quality–related metabolite patterns differ depending on the components of diet quality indices (18). This might account for differences in findings as some of the other studies used diet-driven approaches (dietary patterns) rather than a predefined diet index as we did (15, 56, 57). In addition, our study did not include phenolic compounds. It should also be taken into account that the differences may in part be due to different metabolomics platforms. When results reported by Metabolon and the Broad Institute were compared, some variations were found across these 2 platforms (58).

Finally, based on the stepwise model, we developed a metabolomics score that is moderately correlated with the AHEI in both men and women. Although only lipid-related metabolites were included in our metabolomics score, we observed a significant correlation between the predicted and the FFQ-based AHEI scores. In the future, it might be interesting to investigate how this metabolomic score predicts disease outcomes.

Our study possesses a number of strengths. First, we had a large sample size and included healthy men and women, suggesting that our results may be applicable to a general population not defined by exposure or disease. Second, we documented for the first time, to our knowledge, associations of plasma metabolites with the AHEI, a predefined dietary index and a strong predictor of CVD, diabetes, and other health outcomes. Finally, we adjusted for several potential confounders. However, this study has some limitations that should be considered. First, the possibility of residual confounding due to unmeasured lifestyle factors and health conditions cannot be ruled out. Second, our research, like any observational study on dietary intake data, contains measurement error in both the dietary intake and biomarkers. However, studies suggest a strong correlation between FFQ-based dietary intakes and those from food records in the NHS and HPFS (59, 60). Third, our study focused on lipid-related metabolites as these represented the majority of the metabolites in our data set. As this type of data becomes widely available, studies including a more diverse set of metabolites will be able to add and complement our results. Finally, since the number of current smokers was too small in both the NHS and the HPFS, we were not able to perform the analyses stratified by smoking.

In summary, from panels of 212 metabolites in the NHS and 173 metabolites in the HPFS, the current study identified 83 AHEI-related metabolites in the NHS and 96 AHEI-associated metabolites in the HPFS. Of these metabolites, 63 overlapped between the cohorts of men and women. In addition, our study highlighted 23 healthy and 40 unhealthy metabolites in relation to healthy and unhealthy AHEI components. The majority of the healthy-related metabolites included LCFA-containing TAGs and phospholipids, while the unhealthy-related metabolites were mostly characterized by plasmalogens and acylcarnitines. These identified biomarkers may elucidate the biological mechanisms underlying the relation between the AHEI and health outcomes. Therefore, further studies are warranted to examine associations between these identified metabolite patterns with the risk of several diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Profiles of plasma metabolites were measured by LC-MS/MS metabolomics in Dr. Clary Clish's laboratory at the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows–––MB, WW, and EMP: designed the research; MB, OAZ, MKT, KLI, and EMP: conducted the research; MB, OAZ, and MKT: conducted the metabolomics quality control; MB, OAZ, EMP, MKT, and PK: ran the statistical analyses; MB: wrote the manuscript; WW, MKT, KLI, EBR, KMW, KHC, EWK, OAZ, and AHE: did revisions or provided critique; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Notes

Sources of support: The Health Professionals Follow-up Study and Nurses’ Health Study cohorts are supported by the following NIH grants: U01 CA 167552 and UM1 CA 186107, respectively. The salary of KLI was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council fellowship. The endpoint-specific grants are as follows: CA087969 (NIH) and W81XWH-13-1-0493 [Department of Defense (DOD)] (ovarian cancer), NS045893 (NIH) (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), CA130288 (DOD) with additional funding from the Lustgarten Foundation (pancreatic cancer), AR057327 (NIH) (rheumatoid arthritis), and CA167552 (NIH), CA090381 (NIH), Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (DF/HCC) Specialized Program in Research Excellence (SPORE) (prostate cancer).

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending application and approval.

Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 and Supplemental Figures 1–3 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/.

Abbreviations used: AHEI, Alternate Healthy Eating Index; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; CCA, canonical correspondence analysis; CVD, cardiovascular disease; FDR, false discovery rate; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study; LCFA, long-chain fatty acid; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study; PC, principal component; PCA, principal component analysis; QC, quality control; TAG, long-chain triacylglycerol.

Contributor Information

Minoo Bagheri, Channing Division of Network Medicine Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Nutrition, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Community Nutrition, School of Nutritional Sciences and Dietetic, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Walter Willett, Department of Nutrition, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Mary K Townsend, Department of Cancer Epidemiology, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, USA.

Peter Kraft, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Kerry L Ivey, Department of Nutrition, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Infection and Immunity Theme, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia.

Eric B Rimm, Channing Division of Network Medicine Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Nutrition, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Kathryn Marie Wilson, Channing Division of Network Medicine Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Karen H Costenbader, Channing Division of Network Medicine Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Elizabeth W Karlson, Channing Division of Network Medicine Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Elizabeth M Poole, Channing Division of Network Medicine Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

Oana A Zeleznik, Channing Division of Network Medicine Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

A Heather Eliassen, Channing Division of Network Medicine Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

References

- 1.Wirt A, Collins CE. Diet quality—what is it and does it matter?. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(12):2473–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gil Á, Martinez de Victoria E, Olza J. Indicators for the evaluation of diet quality. Nutr Hosp. 2015;31(3):128–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imamura F, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Fahimi S, Shi P, Powles J, Mozaffarian D. Dietary quality among men and women in 187 countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic assessment. Lancet Global Health. 2015;3(3):e132–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naicker A, Venter CS, MacIntyre UE, Ellis S. Dietary quality and patterns and non-communicable disease risk of an Indian community in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Health Popul Nutr. 2015;33(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM, Miller PE, Liese AD, Kahle LL, Park Y, Subar AF. Higher diet quality is associated with decreased risk of all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer mortality among older adults. J Nutr. 2014;144(6):881–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCullough ML, Feskanich D, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci EL, Rimm EB, Hu FB, Spiegelman D, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC. Diet quality and major chronic disease risk in men and women: moving toward improved dietary guidance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(6):1261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB, Hu FB, McCullough ML, Wang M, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J Nutr. 2012;142(6):1009–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bingham SA. Limitations of the various methods for collecting dietary intake data. Ann Nutr Metab. 1991;35(3):117–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall JR, Chen Z. Diet and health risk: risk patterns and disease-specific associations. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(6):1351S–6S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willett WC, Hu FB. The Food Frequency Questionnaire. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(1):182–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elmstahl S, Gullberg B. Bias in diet assessment methods—consequences of collinearity and measurement errors on power and observed relative risks. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(5):1071–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]