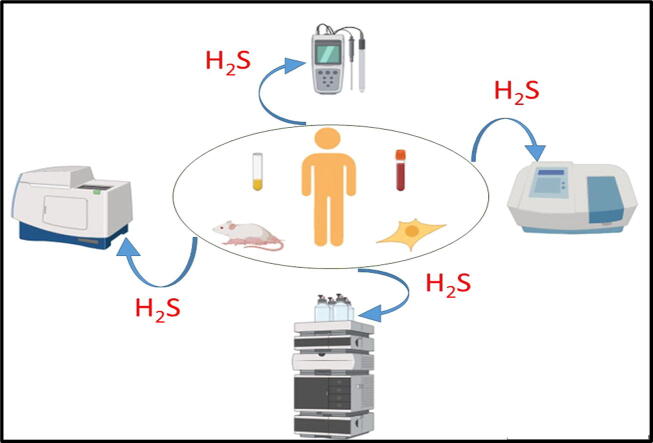

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Hydrogen sulfide H2S, in vivo detection, Fluorescent probes, Colorimetric probes, Chemiluminescent probes, Chromatographic bioanalysis, Chromatographic methods, Electrochemical sensors

Abstract

Background

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is currently considered among the endogenously produced gaseous molecules that exert various signaling effects in mammalian species. It is the third physiological gasotransmitter discovered so far after NO and CO. H2S was originally ranked among the toxic gases at elevated levels to humans. Currently, it is well-known that, in the cardiovascular system, H2S exerts several cardioprotective effects including vasodilation, antioxidant regulation, inhibition of inflammation, and activation of anti-apoptosis. With an increasing interest in monitoring H2S, the development of analysis methods should now follow.

Aim of review

This review stages special emphasis on the several analytical technologies used for its determination including spectroscopic, chromatographic, and electrochemical methods. Advantages and limitations with regards to the application of each technique are highlighted with special emphasis on its employment for H2S in vivo measurement i.e., biofluids, tissues.

Key Scientific Concepts and important findings of Review

Fluorescence methods applied for H2S measurement offer an attractive non-invasive and promising approach in addition to its selectivity, however they cannot be considered as H2S-specific probes. On the other hand, colorimetric assays are among the most common methods used for in vitro H2S detection, albeit their employment in vivo H2S measurement has not yet been possible . Separation techniques such as gas or liquid chromatography offer higher selectivity compared to direct spectrophotometric or fluorescence methods especially for suitable for endpoint H2S measurements i.e. plasma or tissue samples. Despite all the developed analytical procedures used for H2S determination, the need for highly selective, much work should be devoted to resolve all the pitfalls of the current methods.

Introduction

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is an important gaseous signaling molecule that sits with nitric oxide and carbon monoxide as the biologically active family of “gaseous mediators” or “gasotransmitters” [1]. It is produced at low concentrations in mammalian systems mainly via enzymatic interconversions of sulfur-containing substrates to fulfill a vast number of biological functions in almost every organ [2]. For example, in the central nervous system it acts as a neuromodulator [3] in addition to its effect for controlling perception of pain and neuronal potentiation [4]. In the cardiovascular system, it causes vasodilation and protects vasculature from reperfusion injury [5], [6]. Asides, H2S plays other pivotal biological roles viz., angiogenesis, anti-inflammation, inhibition of insulin signaling, regulation of blood pressure [7], and even involved in longevity [8]. On the other hand, H2S also participates in many pathological activities of various diseases, such as Parkinson's disease [9], Alzheimer's disease [10], Down's syndrome [11] and diabetes [12]. Owing to its vast involvement in various physiological processes, H2S‐based therapeutics have been recently investigated [1]. Consequently, it is of great importance to develop fast and sensitive determination methods to scrutinize H2S levels. However, in vivo monitoring and detection of H2S faces many serious challenges owing to its promiscuous chemical properties such as volatility, high reactivity, and rapid catabolism. Asides, H2S presents, under physiological conditions, pH 7.4 and 37 °C, in different chemical ionization forms i.e. approximately 18.5% H2S, 81.5% hydrosulfide anion (HS ـــ) and a negligible contribution of S2- [13]. Moreover, it might also exist in different bound forms such as acid-, base-labile and reducible forms, which are utilized in liberating free hydrogen sulfide following physiological stimuli in biological systems [14]. In addition, the extraction and sample treatment of H2S may face interference from the biological matrices such as proteins present in blood, plasma, serum and cells [15], [16] thus the real concentration of H2S in different biological samples was in debate for a long time due to the disaccording reported data [17].

Owing to the previously mentioned challenges for H2S determination, developed analytical methodologies should fulfill certain criteria to be successfully implemented including sufficient sensitivity for endogenous H2S, real-time monitoring for H2S level changes and high selectivity for H2S over other endogenous bio-thiols (ex. glutathione, cysteine …) or other ions present in the blood or tissues under investigation. Hence, a plethora of different analytical methods has evolved for H2S measurements such as fluorescence-based assays [18], colorimetric sensors [19], chromatographic methods (HPLC and GC) [20] and electrochemical methods (ion-selective electrodes and polarographic H2S sensors) [21]. However, each of these techniques has its advantages and limitations. Colorimetric and chromatographic assays have been used for the bulk measurement of both plasma and tissue H2S, however, they do not have the capability for real-time monitoring of H2S within intact tissues or living cells, in addition, they are denounced to be sample-destructive. On the other hand, fluorescence-based sensors have been developed to meet these challenges and to provide sensitive and biocompatible detection tools for H2S not only within certain tissues but also within subcellular organelles. Ion selective electrodes have also been widely used as an effective method to measure the H2S in different biological matrices with distinct advantages of low detection limit and fast response, however, vigorous alkaline conditions are required to convert H2S and HS− to S2− as this is the only form the electrode can measure. Unfortunately, liberation of sulfur from other biomolecules has been detected at such conditions which could lead to an overestimation of molecular H2S concentrations.

Several reviews have reported on the different analytical approaches applied for the determination of this gaseous signaling molecule [18], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]. However, most of these reviews focused only on spectroscopic techniques with special emphasis on probe materials [18], [19], [29], design strategies [27], [30], and detection mechanisms [28], [31]. Asides, very few reports have discussed other analytical methodologies such as electrochemical and chromatographic methods [21], [22]. In this review, we summarize the information about the currently available state-of-the-art analytical techniques used to measure physiological H2S levels. The reported methods were organized into categories following their instrumentation type and then subdivided based on their working principle. Also, the advantages and limitations of these methods have been addressed to guide researchers through the appropriate analytical tool to choose for their application.

Fluorescence-based sensors

While chromatographic assays and electrochemical sensors have been used to determine H2S levels in the blood, homogenized tissues, and cell lysates [32], these methods are mostly less suited for its determination in living biological specimens. Though, fluorescence techniques have attracted much attention as sensors offering excellent sensitivity, good selectivity, rapid response, and non-invasive detection with a high spatiotemporal resolution for both in vitro and in vivo imaging as typically needed for quantifying H2S. Moreover, fluorescence-based sensors offer real-time H2S monitoring not only within certain tissues but also within subcellular organelles. Therefore, the evolution of H2S- fluorescence probes is considered one of the most rapid-growing areas in the field of H2S biology [17]. Though, a substantial increase in the number of developed small molecule-based sensors was remarked in the past decade. Diverse small organic compounds and metal chelates have been explored with different H2S-reaction sites. Recently, nanotechnology was implemented for the development of effective and highly sensitive fluorescent nanosensors used for H2S detection [33] as typical in the detection of other signaling molecules or drugs.

Monitoring H2S in subcellular structures is considered crucial for biomarkers discovery and related drug discovery. Therefore, the emergence of organelle-targeted fluorescent probes is essential for subcellular imaging revealing the physiological and pathological functions of these highly reactive, interactive, and interconvertible molecules during diverse biological events, which are significant for the understanding of diseases etiology. Organelle-targeted fluorescent probes should encompass three moieties: targeting groups, fluorophores, and recognition units. Many cellular organelles-targeting scaffolds were coupled with the fluorophore and the H2S-recognition moieties. For example, the mitochondrial-targeting entities comprise positively charged groups as triphenylphosphonium, quaternary ammonium, isoquinolinium, acridine, indolium, and pyridium [34]. Whereas the sulfide-recognition entities include azides, nitro, hydroxylamine, dinitrophenyl, NBD. After reaching subcellular locations of interest, probes can subsequently react with free sulfide through and.specific reaction mechanisms and consequently fluorescence response measurements via turn-on, -off, or ratiometric, which enables the monitor of targeted species in different organelles [35], [36].

The determination of endogenous H2S in vivo presents indeed many challenges due to its low concentration, short half-life time with fast catabolism, and high reactivity. Although there are limits of measurement techniques and the quantification of biological H2S levels is debated, H2S physiological levels may range from 50 to 160 µM in the mammalian brain, to 30 nM–100 µM in the peripheral blood, 25 µM in the synovial fluid of non-inflammatory arthritic patients [37], 8.9 nM in mice liver tissue [38]. An ideal fluorescent probe should thus fulfill the following criteria:

-

i)

to be sufficiently sensitive for endogenous H2S detection and real-time monitoring for the changes in H2S fluxes in living cells,

-

ii)

to react rapidly (spontaneously) under physiological conditions (i.e., aqueous solutions, blood, plasma) without the need of organic solvents or surfactant.

-

iii)

to display high selectivity and not to interact with other endogenous bio-thiols (i.e., glutathione, cysteine …) or other ions present in blood or tissues under investigation.

-

iv)

to exhibit very low or no cytotoxicity to be promising for further development (bio-compatible & bio-degradable).

-

v)

to emit in the near-infrared preferably at 700–900 nm as this permits greater tissue penetration, causes less cellular photo-damage or phototoxicity and minimizes the interference from background auto-fluorescence. The emission is preferably accompanied by large Stokes shift, as small Stokes shifts may lead to measurement errors such as auto-quenching and/or excitation back-scattering [39]

-

vi)

to be functionalized to target certain subcellular organelles (mitochondria, lysosome, nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, …), certain cells (hepatocytes, ….), tissues, or organs.

Based on H2S main chemical properties i.e., nucleophilicity, reducibility, and metal precipitation capability, researchers have developed a large number of fluorescent molecules which can be classified according to their H2S-reactive sites or chemical reaction-based sensors as detailed in the next sections and summarized in Table 1 highlighting the main advantages, disadvantages, and applications of each probe.

Table 1.

Representative examples of certain fluorescent sensors for H2S determination with the advantages and disadvantages of each probe.

| N° | Sensor | Properties & Applications | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| F1 |  |

Adv.: emission in the NIR (700 nm) Disadv.: relative long response (sulfide-sensor reaction) time (30 min), detection medium contains DMF, unsatisfactory selectivity (2- & 5-fold increased selectivity versus O2– & GSH/Cys, respectively) Application: living Cells (HEK293T cells) |

[40] |

| F2 |  |

Adv.: emission in the NIR (˃ 700 nm), Stokes shift = 90 nm; low LOD (80 nM); detection medium: 100% aqueous Disadv.: relative high response time (20 min) Application: living Cells (RAW264.7) Macrophage cells |

[56] |

| F3 |  |

Adv.: near infrared emission (670 nm) with large Stokes shift (150 nm) Disadv.: detection medium contains high DMSO concentration (50%), long response time (60 min), high LOD 3050 nM Application: bovine serum, living cells (HeLa & MCF-7), tissues (fresh rat liver cancer slice) & live mice (monitoring localized diffusion after a dorsal skin-pop injection) |

[165] |

| F4 |  |

Adv.: targeting lysosome (morpholine moiety), Disadv.: medium contains 10% DMF, small Stokes shift (25 nm) λex/em = 530/555 nm Application: exogenous & endogenous H2S in lysosomes of living cells (HeLa) |

[44] |

| F5 |  |

Adv.: 35-fold fluorescence enhancement, mitochondria-targeted and 1st time target nucleus Disadv.: photosensetive, large response time (60 min), detection medium contains DMSO (2%), not specified LOD, small Stokes shift (45 nm) λex/em = 405 – 450 nm Application: living cells (HeLa) |

[43] |

| F6 |  |

Adv.: near infrared emission (710 nm), detection medium aqueous (PBS) Disadv.: long response time (40 min); small Stokes shift (60 nm), Application: mitochrondria / human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 T & HeLa cells |

[52] |

| F7 |  |

Adv.: good hepatocyte-targeting, excellent water solubility, low cytotoxicity, fast response (within 1 min), high selectivity, good sensitivity (LOD 126 nM) Application: hepatocyte-targeting |

[51] |

| F8 |  |

Adv.: wide pH range (4–9), good sensitivity (LOD = 10 nM) Disadv.: relative long response time (15 min), the medium contains ethanol (25%), UV excitation (340 nm) Application:in vitro exogenous H2S in HeLa (human cervical cancer cell) and L929 (murine aneuploid fibrosarcoma cell) |

[49] |

| F9 |  |

Adv.: both excitation and emission in the NIR (755/809 nm), aqueous medium, large linear range 0 – 350 µM, wide pH range 4.2 – 8.2 Disadv.: relative small Stokes shift (54 nm), moderate quantum yield (0.11); 12.7 fold fluorescence enhancement, the long response time (60 min); biothiols as GSH & Cys interfere with H2S determination Application: living cells (RAW264.7) |

[41] |

| F10 |  |

Adv.: 13-fold fluorescence enhancement, satisfactory sensitivity (LOD 500 nM), Quantum yield 0.12 λex/em = 435 / 544 nm Disadv.: very long response time (120 min); Interference with sod. ascorbate Application: living cells (Astrocyte cells) |

[42] |

| B) Electrophile-based probes (containing 2,4-dinitrophenyl moiety) | |||

| F11 |  |

Adv.: very fast response time (4 sec.), NIR emission (680 nm), 115 fold fluorescence enhancement, linearity range (1–10 µM), good sensitivity (LOD = 11 nM), satisfactory Stokes shift (90 nm λex/em = 590/680 nm), aqueous detection medium (PBS), low cytotoxicity against different cellular lines Application: lysosome-targeting/cell (HeLa) and mice (monitoring localized diffusion after intraperitoneal injection) |

[59] |

| F12 |  |

Adv.: relative rapid response time (10 min), NIR emission (663 nm), very large Stokes shift (244 nm), 105-fold fluorescence enhancement, good sensitivity (LOD = 42 nM), good selectivity, linear range 0 – 50 µM, wide pH range (6 – 10), good quantum yield = 0.22 Disadv.: detection medium contains DMSO (30%), not for acidic pH Application: exo & endogenous H2S in vitro (HeLa cells) |

[166] |

| F13 |  |

Adv.: rapid response time (4 min), 32-fold fluorescence enhancement, good quantum yield (0.45); good sensitivity (LOD = 150 nM) linear range 0 – 100 µM, pH range (5 – 10), aqueous detection medium (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid buffer) Disadv.: GSH reacts with the probe but at a lesser extent (slower rate) than sulfide Application: target endoplasmic reticulum, endogenous & exogenous H2S imaging in living cells |

[167] |

| F14 |  |

Adv.: NIR fluorescent probe, linear range (12–38 μM), large Stokes shift (97 nm, λex/em = 543 nm / 640 nm) Disadv.: high LOD 3090 nM, very long response time (170 min) & time-dependent fluorescence increase, certain anions as dihydrogen phosphate respond to the probe, The sensor was not tested against biological thiols (GSH, Cys,…..) to evaluate their possible interferences. Application: detect molecular H2S in the gaseous state, H2S in real water, red wine and living cells (MCF-7 (human breast carcinoma) cells) |

[94] |

| F15 |  |

Adv.: rapid response (3 min); near-infrared fluorescent probe, 11-fold fluorescence enhancement; large Stokes shift (107 nm, λex/em = 557 / 664 nm), quantum yield (0.11), linear range (0 to 30 μM) with LOD (68.2 nM), high selectivity Disadv.: medium contains DMSO & disodium phosphate dodecahydrate Application: living cells (Hela cells) / mitochondria-targeting |

[168] |

| F16 |  |

Adv.: NIR emission, 169-fold fluorescence enhancement, LOD = 121 nM, pH range 5 – 8.5, good selectivity Disadv.: time – dependent fluorescence increase (linearly up-to 180 min); small Stokes shift (49 nm, λex/em = 590/639 nm), detection medium contains DMSO (10%) Application: HeLa cells / lysosome-targeting |

[67] |

| F17 |  |

Adv.: rapid response time (less than1 min), fluorescence enhancement 130-fold, very large Stokes shift (221 nm, λex/em = 445/666 nm), good sensitivity (LOD = 6 nM) Disadv.: detection medium contains DMSO (20%) Application: HeLa cells/mice |

[63] |

| F18 |  |

Adv.: good sensitivity (LOD = 50 nM), wide linear range 0 – 275 µM, Stable over wide pH range, good selectivity, large Stoches shift (140 nm, λex/em = 415 / 555 nm) Disadv.: slow response time (40 min), 6-fold fluorescence enhancement, detection medium contains DMSO (2.5%) Application: spiked rat urine samples, exogenous & artificially generated endogenous H2S in living cells (Hela) &in vivo living Caenorhabditis elegans (nematodes) |

[64] |

| F19 |  |

Adv.: relative rapid response time (2 min), NIR emission (652 nm), 35-fold FL enhancement, good sensitivity (LOD = 10 nM), good selectivity, large Stokes shift (128 nm, λex/em = 512 / 652 nm), Stable over 6 – 10 pH, Linear range 0 – 30 µM Disadv.: weak quantum yield (0.067), detection medium contains high organic solvent DMF (50%), not for acidic pH Application: imaging exogenous H2S in Hela cells & artificially generated endogenous H2S in RAW264.7 cells, in vivo (Kunming mice) |

[65] |

| F20 |  |

Adv.: relative rapid response time (10 min), good selectivity, high sensitivity (LOD = 0.89 nM), wide linear range 2 nM – 1500 nM, Low cytotoxicity Disadv.: small Stokes shift (54 nm, λex/em = 480/534 nm) Application: living cells (MCF7) |

[62] |

| B) Electrophile-based probes (containing NBD (7-nitro-1,2,3- benzoxadiazole)) | |||

| F21 |  |

Adv.: 45-fold fluorescence enhancement, satisfactory Stokes shift (75 nm, λex/em = 405/480 nm), 1st fluorescent probe based on thiolysis of NBD amine Disadv.: relative slow response time (30 min), low sensitivity (LOD = 9000 nM), Application: living cells (HEK293 & HeLa cells) |

[72] |

| F22 |  |

Adv.: mitochondria-targeting, 68-fold fluorescence enhancement, low cytotoxicity, biocompatible, good selectivity. Disadv.: slow response time (40 min), moderate sensitivity (LOD = 2460 nM), small Stokes shift (53 nm λex/em = 394 / 532 nm) and detection medium contains CH3CN (10%) Application: HeLa cells (Mitochondria). |

[71] |

| F23 |  |

Adv.: 45-fold fluorescence enhancement, good sensitivity (LOD = 56 nM), good selectivity, good Sockes shift (92 nm, λex/em = 394/486 nm) Disadv.: response time (20 min), narrow pH range (7.4–8.5), medium contains DMSO (10%) Application: H2O2-induced H2S release in Yeast cells |

[66] |

| F24 |  |

Adv.: rapid response (~3 min), 4.5-fold fluorescence enhancement, Quantum yield = 0.36, linear range (0–30 μm), satisfactory sensitivity (LOD = 580 nM), pH rang (6–8.5) Disadv.: sulfites ions react but at a lesser extent than sulfides, small Stokes shift (22 nm, λex/em = 567/589 nm) Application: H2O2‐induced H2S biogenesis in living cells. |

[68] |

| F25 |  |

Adv.: rapid response time (5 min), 17-fold fluorescence enhancement, LOD = 9.6 nM, pH range 5 – 8, good selectivity Disadv.: detection medium contains DMSO (10%); small Stokes shift (49 nm, λex/em = 590 / 639 nm) Application: HeLa cells / Lysosome-targeting |

[67] |

| B) Electrophile-based probes (containing aromatic carbonyl with adjacent α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compound) | |||

| F26 |  |

Adv.: relative rapid response time (20 min), 13-fold fluorescence enhancement, better quantum yield = 0.208 Disadv.: small red shift (Stokes shift = 45 nm, λex/em = 465 / 510 nm) with low sensitivity (LOD = 5000 nM), detection medium contains DMSO (1%) & time-dependent (0 – 60 min) fluorescent increase Application:in vitro HeLa cells |

[73] |

| F27 |  |

Adv.: satisfactory Stokes shift 55 nm, pH range (5–8), Disadv.: energetic excitation (308 nm), Medium contains DMSO (10%), limited sensitivity (high LOD 1700 nM), Application: living cells (Vero) |

[74] |

| F28 |  |

Adv.: good sensitivity (LOD = 160 nM), linear range (0 – 10 µM), wide pH range (3 – 9), large Stokes shift (108 nm, λex/em = 445 – 577 nm) Disadv.: long response time (40 min), detection medium contains DMSO Application: HepG2 cells and Chlorella |

[75] |

| B) Electrophile-based probes (containing (disulfide or selenenyl sulfide) benzoate ester) | |||

| F29 |  |

Adv.: fluorescence enhancement 15-fold; good selectivity, good sensitivity LOD = 790 nM, large Stokes shift (108 nm, λex/em = 345/453 nm), linear range (0–300 µM) Disadv.: long response time (30 min); energetic excitation wavelength, detection medium contains CH3CN (30%) and CTAB 1 mM Application: endogenous and exogenous H2S in HeLa cells, Drosophila. melanogaster and C. elegans |

[169] |

| F30 |  |

Adv.: NIR emission, good sensitivity LOD (1.1 nM), large Stokes shift (120 nm, λex/em = 560/680 nm) Disadv.: long response time (30 min), detection medium: containing 50% DMSO/PBS Application: living cells |

[76] |

| F31 |  |

Adv.: 10-fold fluorescence enhancement, linear range: 2–14 μM; LOD 25.7 nM, pH range (7–10), Disadv.: relative long reaction time (15 min), biothiols as (L- Cys, Hcy, GSH) were tested at the same H2S concentrations (50 μM) medium contains DMF (10%), Application: living cells (HeLa) |

[170] |

| F32 |  |

Adv.: NIR emission, Quantum yield (0.19), 22-fold fluorescence enhancement, pH range 6–12, good sensitivity 36 nM, large Stokes shift (129 nm, λex/em = 510/639 nm) Disadv.: narrow linear range (1–6 μM), the medium contains DMF (10%), the long response time (60 min), biothiols as (L- Cys, L-methionine) reacts with the probe but at the lesser extent and they were tested at lower concentrations (50 μM vs 20 μM H2S) Application: target mitochondria, in vitro (HeLa cell), in vivo (mice) |

[80] |

| |||

| F33 |  |

Adv.: 100% aqueous medium, rapid response time (instantaneous), large Stokes shift (161 nm, λex/em = 256, 417 nm), good selectivity, no cytotoxicity (up to 100 µM, WST-1 cells) Disadv.: UV excitation range (energetic), relative low sensitivity (LOD = 3900 nm), pH range is not checked Application: living cells, HeLa cells treated with exogenous H2S |

[83] |

| F34 |  |

Adv.: 100% aqueous medium, rapid response time (1 min), satisfactory Stokes shift (55 nm, λex/em = 375, 430 nm), high quantum yield (0.65), good sensitivity (205 nM), Disadv.: biothiols as Cys react with the sensor but at a lesser extent than sulfide Application: living cells (HeLa), in vivo (Zebra fish) |

[171] |

| F35 |  |

Adv.: satisfactory sensitivity (LOD 250 nM), good aqueous solubility, the rapid response time (less than 1 min), satisfactory Stokes shift (66 nm, λex/em: 480/546 nm) Disadv.: biothiols as Cys & GSH were tested at the same concentration (20 µM) as NaHS (not relevant to physiological concentration ratios). Application: living cells, HeLa cells treated with exogenous H2S |

[172] |

| F36 |  |

Adv.: NIR emission, fast response time (30 sec), good sensitivity (LOD 92 nM), good aqueous solubility, large Stokes shift (95 nm, λex/em: 530/625 nm) Disadv.: highly pH-dependent fluorescence, narrow pH range (7–8), the medium contains MeOH (75%). Application: human serum and bovine serum albumin, living cells, (C-6 cells) treated with exogenous H2S |

[82] |

Reduction-based fluorescence compounds:

These compounds contain an easily reducible group such as azide [40], nitro [41], or hydroxylamine [42], which act generally as fluorescence quenchers. These quenchers are linked to a fluorophore nucleus such as coumarin [43], rhodamine [44], chromone [45], cyanine [41], benzopyran derivative [46], dansyl [47], naphthalimide either as a molecular sensor [42], [48] or incorporated in a nanosensor [49]. The reaction proceeds via their reduction to their corresponding amines under physiological conditions.

H2S-activated fluorescent sensors are mainly based on the difference of emission wavelength and quantum yield before and after reaction with free sulfide or measuring differential fluorescence response at two different wavelengths. Based on the fluorescence signal(s) and post-measurement data analysis, such category can be further subdivided into:

-

i)

Fluorescence Turn-on: Principle entails measuring the increase in fluorescence emission. Since the first reported probe based on the reduction of non-fluorescent azides to fluorescent amines, compound F1, many azide-containing probes were developed, Table 1. Although compound F1 exhibits fluorescence emission in the near infra-red region (700 nm) and was used for monitoring H2S in HEK293 T cells it displays lower selectivity with relatively long response time (30 min) [40]. Another compound F4 was developed to target lysosome, containing a spirolactam moiety which opens in lysosomal acidic microenvironments, while its azide group is reduced by H2S giving a fluorescent derivative, albeit it exhibits small Stokes shift [44]. Whereas compound F5, was synthesized to target the mitochondria and for the first time to target the nucleus, however, it suffers from photosensitivity alongside a slow response (60 min) [43]. A sensitive fluorogenic nanoprobe containing azide having a good sensitivity (LOD = 18 nM) was introduced to determine H2S in vitro (living cells and mice serum) and the differentiation between sera of diabetic and non-diabetic mice [50]. Recently, a hepatocyte-targeting sensor, F7 containing galactosyl moiety was developed due to the specific recognition of ASGPR over-expressed in hepatocytes by galactose group. It displays fast response (≈ 1 min) with good selectivity and sensitivity (LOD = 126 nM) [51].

-

ii)

Fluorescence Turn –Off: It is based on measuring the decrease in fluorescence emission. Many sensors were developed exhibiting “turn-off” fluorescence response, Table 1. for example compound F9 contains an azide group linked to rhodamine derivative as a fluorophore [52]. This compound was used for quantifying H2S in human embryonic kidney 293 T cells and could target mitochondria but it suffers from relatively long response time (40 min). Another boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY) derivative was developed to detect H2S in normal human oral fibroblast cells with good sensitivity 170 nM but still suffers from long response time (20 min) in a medium containing 33% methanol [53]. Organic solvents have certain limitations which may hamper further development for in vivo applications. For example, DMSO exhibits hemolytic activity and a significant effect on cellular membrane permeability. Moreover, it induces apoptosis of the vascular endothelial cells [54], whereas ethanol mediates for red blood cell hemolysis [55].

-

iii)

Ratiometric analysis: It measures the intensity ratio changes at two emission wavelengths which generally offers more accurate results than turn-on and turn-off because it does not generate false positive/negative signals nor it is affected by analyte-independent interfering factors, such as the excitation source fluctuation, sample matrix background light scattering and autofluorescence, the microenvironment around the probe, and variation of the local concentration of the probe [33]. The first ratiometric fluorescent probe is an azido-heptamethine cyanine dye (compound F2) that exhibits emission in NIR (greater than700 nm) with good sensitivity (LOD = 80 nM) and was found able to detect changes in H2S levels in macrophage RAW264.7 cells, though to display long response time (20 min) as its only caveat [49], [56].

Recently, a portable H2S analyzer was proposed as a simple determination of H2S in both aqueous solution and plasma using a fluorescent probe. The developed method was applied and validated for the quantification of H2S in plasma of cardiovascular patients [15]. The developed fluorescent sensor relied on the use of an azide derivative (an H2S reduction-based mechanism) [47]. However, this probe was not examined against the most abundant biothiols as GSH which represents a limitation for its biological application. Moreover, the derivatizing medium contains tween 20 which is known for its hemolytic activity [57] and to account for its validation using plasma and not on whole blood. Another recent study developed a microfluidic method for the measurement of sulfide in blood plasma that relied on using the same fluorescent sensor dansyl azide, which confirmed the plasma matrix interference. Though a dilution step 3.3-fold dilution is required to reduce plasma interaction with exogenous sulfide [58].

Electrophile-based probes

These chemicals encompass at least one or two electrophilic centers to be attacked via nucleophilic addition/substitution reaction to yield a thio-derivative, followed by another intramolecular nucleophilic addition/substitution of H2S to the probe. This results in one or two fluorescent compounds

-

i)

2,4-dinitrophenyl-based probes: The 2,4-dinitrophenyl moiety acts as a quencher of the fluorophore moiety via photo-induced electron transfer (PET). 2,4-Dinitrophenyl moiety can be linked to the fluorophore nucleus such as cyanine [59], xanthene [60], pyridinium derivative [46], pyrimidine derivative [61], functionalized graphene quantum dots [62] via an ether linkage, or a sulfonamide linkage to fluorophore as dicyanoisophorone [63], curcumin [64], coumarin [65].

The reaction with H2S proceeds via nucleophilic addition of H2S to the probe generating a thiol derivative which undergoes subsequent intramolecular nucleophilic substitution (thiolysis) and cleavage of the linkage (i.e., ether, sulfonamide, and ester) liberating the fluorophore (parent fluorescent dye).

As illustrated in Table 1, this family of compounds exhibits various advantages according to the fluorophore derivatives being employed leading to emission in NIR as compounds F11, 12, 15, 17, 19 with very large Stokes shift (244 nm) exemplified in compound F12. Certain intracellular organelles could be targeted as lysosome (F17), endoplasmic reticulum (F13), or mitochondria (F15). A sensitive fluorescent sensor, F23 (LOD = 11 nM) contains an ether-linkage and cyanine derivative (fluorophore) was developed to react instantaneously with H2S (4 sec) exhibiting 115-fold fluorescence enhancement (Turn-on). It offers a water-soluble sensor that has been used in cellular imaging (HeLa and HepG2), lysosomes, and in vivo in mice [59]. The fluorescence enhancement is generally reflecting the increase in the fluorescence intensity in the presence of sulfide compared to that of the probe alone under the give reaction conditions (Time, temperature, pH, ….…).

The first developed sensor containing sulphonamide linkage was that of compound F17, as a new selective reaction site for H2S, between the 2,4-dinitrophenyl moiety (quencher) and dicyanoisophorone (fluorophore) exhibited high sensitivity (LOD = 6 nM), rapid response (less than 1 min), large Stokes shift (221 nm) and has been used in cellular imaging and in vivo in mice [63].

Graphene quantum dots-based sensor, F20 offers the highest sensitivity (LOD 0.89 nM) of this family with wide linear range (2 – 1500 nM) and used for H2S detection in MCF7 but it displays excitation /emission out of the NIR with relative short Stokes shift and relative long response time (10 min).

-

ii)

NBD (7-nitro-1,2,3- benzoxadiazole)-based probes: The 7-nitro-1,2,3- benzoxadiazole acts as a quencher of the fluorophore. The fluorophore moiety can belong to coumarins [66], rhodamine B amines [68], [69], Tetrahydro [5] helicene [70], naphthalimide [71] all linked to NBD via different linkers as ether or thioether bond. As the reaction proceeds, under physiological pH via the attack of the nucleophilic sulfhydryl group to the probe generating a thiol derivative which undergoes subsequent intramolecular nucleophilic substitution (thiolysis), liberating the non-fluorescent thio-NBD derivative and the fluorophore. Therefore, all the NBD-based H2S sensors exhibit turn off–on fluorescence response.

As illustrated in Table 1, compound F21 was the first synthesized NBD-based H2S sensor used for its detection in vitro in living cells (HEK293 and HeLa cells) [72], after which many NBD-based H2S sensors were developed to improve sensor features such as sensitivity level [66], or to target certain organelles as lysosomes using compound F25 [67] or mitochondria using compound F22 [71]).

-

iii)

Aromatic carbonyl with adjacent α,β-unsaturated carbonyl-based probes (Michael acceptor):

The reaction in these probes proceeds via two mechanisms. First, it involves a double nucleophilic addition in which H2S attacks the aromatic carbonyl group generating a thiol derivative which undergoes subsequent Michael addition to yield the acrylate ester (α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compound (Michael acceptor) leading to cyclic fluorescent thio-derivative [73], [74]. Second, it functions via a double nucleophilic attack, initially through HS- nucleophilic substitution generating a thiol derivative that undergoes subsequent intramolecular nucleophilic addition that leads to cyclic non-fluorescent compound (Turn-off) carbazole derivative [75]. As illustrated in Table 1, compounds F26-28 were used for in vitro H2S cellular imaging (HeLa, Vero, and HepG2 cells), albeit they use relatively energetic excitation wavelengths (308–465 nm) with subsequent increased risk of cellular photo-damage or phototoxicity. Furthermore, these sensors displayed a relatively long response time (20–40 min) and moreover failing to attain high sensitivity (160 nM – 5000 nM).

-

iv)

Probes containing (disulfide or selenenyl sulfide) benzoate ester-linked to a fluorophore

The reaction proceeds via two consecutive nucleophilic substitutions initially through HS- nucleophilic substitution generating a thiol derivative which undergoes subsequent intramolecular nucleophilic substitution and cleavage leading to a fluorophore and cyclic non-fluorescent thio-compound [76], [77]. The first disulfide-based sensors were developed [78] with the drawback of overconsumption of biothiols and thus high probe loading was needed. Certain biothiols (RSH) as glutathione, L-cysteine, and Homocysteine could undergo the first substitution step consuming part of the sensor but could not proceed beyond. As these biothiols do not possess more than one replaceable proton, which prevents the achievement of the second nucleophilic substitution step and consequently blocking the cyclization and the fluorophore liberation. It is worth noting that glutathione (GSH) represents the most abundant cellular biothiols (1–10 mM) [79]. Though GSH should be evaluated its potential interference at least (1 mM) 10 times H2S biological concentrations which were in the nano-micromolar range [38]. Many sensors were tested even at a higher GSH/H2S concentration ratio (20x) as in the case of compounds F11, F15, F19, and F26. However, the selectivity is questionable for certain sensors which evaluated at lower GSH/H2S concentration ratio or even at the same sulfide concentration as in the case of compounds F31 and F32. As shown in Table 1, compounds belonging to this family of sensors exhibit emission in NIR with very large Stokes shift (120 and 129 nm) and display good sensitivity (LOD = 1.1 and 36 nM) as exemplified in compounds F30 and F32, respectively. Certain intracellular organelles could be targeted as mitochondria to detect H2S as compound F53. However, biothiols still show slight interference [80], which may be attributed to the contribution of other nucleophilic centers in these interfering molecules leading to cyclization and liberation of the fluorophore.

As the pKa of H2S (6.9) is lower than that of most abundant cellular biothiols such as GSH (9.2), Hcys (8.9), Cys (8.3), indicating that H2S has a stronger nucleophilicity than other biothiols under physiological conditions pH (7.4). However, it is still somewhat difficult to distinguish GSH/Hcys/Cys from H2S simply via nucleophilic reaction-based strategies and affecting quantification results due to such interference

Probes induced metal-sulfide precipitation

- These probes (metal–ligand compounds) contain a fluorescent moiety, chelating agent, and transition metal cations as Cu2+, Zn2+, Hg2+, with to act as a quencher (Turn-off) [29]. The fluorescence turn-on, is driven by precipitation of the metal sulfide (CuS, ZnS, Ksp = 6.4 X 10-36, 1.6 × 10-24) [81], [82].

As shown in Table 1, a copper-based H2S fluorescent sensor compound F33 was synthesized, containing anthracene derivative (fluorophore) attached to azamacrocyclic ring (ligand) as a Cu2+-chelator to form a stable metal complex [83]. The paramagnetic Cu2+ center serves to quench the fluorophore's fluorescence upon H2S binding to Cu2+, which is then extracted from the azamacrocyclic ring resulting in enhanced fluorescence. The probe compound F33 exhibited a fast response with good selectivity for in vitro fluorescence imaging of cellular H2S in HeLa cells treated with exogenous H2S. A zinc-based sensor F36, exhibits emission in NIR with fast response displaying good sensitivity (LOD = 92 nM). It is used for H2S monitoring and quantification in living cells (C-6) and human and bovine sera. However, this sensor is highly pH-dependent with a narrow pH range (7–8).

Nanotechnology has been increasingly implemented in the development of nanosensor based on metal-sulfide precipitation. A turn-on fluorescent probe based on Cu-porphyrin coordination complex combined with gold nanoparticles was developed and applied for H2S in vitro measurement in two carcinoma cell lines (A549 and H1299 cells). Although this nanosensor exhibited NIR emission (650 nm) and good sensitivity (LOD = 17 nM) and selectivity against most interfering ions and biothiols, certain biothiol as Cys showed cross-reaction but at a less extent than sulfide, asides from its relatively slow response time (20 min) than H2S itself [84]. Another fluorescent nanosensor based on carbon quantum dots/silver nanoparticles (CQDs-AgNPs) exhibits one of the most sensitive methods with an LOD = 0.4 nM. This sensor was used for the in vivo monitoring of H2S basal level (3.08 µM) and cerebral H2S level in rat brain during the calm/ischemia states, whereas the linear detection level ranged from 0.001 to 1.9 µM [85]. An easily synthesized fluorescent gold-based nanoclusters were recently reported for H2S detection in living cells (SMMC-7721). This sensor offers several advantages as good aqueous solubility, biocompatibility, high selectivity, wide linear range (27 picoM – 850 µM), and with an outstanding LOD (24 picoM) [86].

However, Cu (II) containing probes, turn-on via CuS precipitation may be interfered by other biological reducing species such as NO, HNO, which occur via metal displacement by His and Cys, reduction of Cu(II) to Cu(I), or hampered by other competitive pathways to remove the metal quencher [87]. Though, a more selective or even specific chemical reaction may be needed to overcome the interfering endogenous similar chemical species or other competitive pathways. Taking into consideration the chemical properties of H2S and the expected sulfide form. [48]

| H2S(g) ⇌ H2S[48] ⇌ HS- + H+ ⇌ S2- + 2H+(1) |

According to pka of H2S, temperature, and medium pH, H2S equilibrates with its two anions HS− and S2−where the three forms exist at different proportions and Eq.1 represents the real dynamics of H2S in solution [13]. However, and according to Le Châtelier’s principle, this equilibrium will continuously shift to either side. For example, it has been reported that half of H2S escapes from solution in five minutes in cell culture wells and 0.5 min in the Langendorff heart apparatus [88]. In subcellular organelles the relative free sulfide proportions, from 90% of HS– in mitochondria (pH = 8) to more than 90% of H2S in lysosomes (pH = 4.7) [89]. Therefore, according to the reaction mechanism and the effective working pH, H2S-probe is destined selectively to one form of the three H2S species. Considering that certain H2S-sensors were selectively reacted with the unionized form (H2S) in a reduction-based reaction (azide, nitro, hydroxylamine,…) [23], [14]. Whereas electrophile-based probes based on the double nucleophilic attack were destined to the most abundant physiological sulfide ion (HS-) [90], while metal displacement-based reactions (Cu2+, Zn2+, Hg2+,….) are destined selectively to the dianionic counterpart (S2-) [91]. It is worth mentioning that most of the analytical methods used mainly Na2S, the least abundant physiological sulfide ion (S2-), in different pH media to carry out either in vitro or in vivo investigations [15], [47], [92], [93], [94].

Colorimetric based assays

Colorimetric methods are assays that are based on spectral changes upon the interaction of chromogen with a particular analyte. Such changes could be monitored using simple instrumentation i.e. spectrophotometers. Colorimetric methods have particularly been employed for H2S determination (Table 2) due to ease of use, fast reaction time and characteristic absorption bands to overcome interference especially in the case of biological samples [95].

Table 2.

Representative examples of certain colorimetric sensors for H2S detection with the advantages and disadvantages of each probe.

| Probe | Principle | Properties & applications | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine | Spectrophotometric detection of the developed methylene blue dye at 670 nm after trapping of H2S with Zn2+. |

Adv.: a simple protocol Disadv.: lack of selectivity for H2S, not suitable for in vivo H2S determination Application:in vitro samples |

[97] |

| NBD-Cl | Thiolysis of NBD-Cl upon reaction with H2S to form nitrobenzofurazan thiol (Pluth red) via a nucleophilic aromatic substitution reaction |

Adv.: fast reaction time, used for both biological and environmental applications, selective. Application: fetal bovine serum |

[98] |

| Azine based sensor | Deprotonation of the sensor –OH |

Adv.: selective, fast response time (less than a minute) Disadv.: low sensitivity (LOD 18.2 μM) Application: human and mouse sera |

[95] |

| 1-(2-Pyridylazo)-2-naphthol-Cu2+ | Displacing Cu+2 from its complex through a metal S2- formation |

Adv.: enhanced sensitivity with LOD 2.5 µM Disadv.: No biological studies or real sample analysis Application: aqueous H2S |

[99] |

|

Adv.: detection of gaseous H2S with LOD 16 ppb Application: gaseous H2S |

[100] | ||

| Boron-dipyrromethene-Cu2+ |

Adv.: good selectivity for the H2S, LOD (0.167 μM), fast reaction time Disadv.: no biological studies or real sample analysis Application: aqueous H2S |

[92] | |

| Ag NPs /Nafion polymer | The reaction of Ag NPs with S2- to form Ag2S with strong absorbance band at 310 nm |

Adv.: simple microplate-based colorimetric assay Application: mouse liver homogenate |

[101] |

| Ag NPs / Nafion/ PVP polymer |

Adv.: wide linear dynamic range for H2S (6.25 to 50 μM) with LOD 1 uM. Application: C6 glioma cells |

[102] | |

| Ag NPs in a layer-by-layer polyelectrolyte multilayer film | UV–vis measurement of the formed Ag2S@Ag NPs at 430 nm. |

Adv.: wide linear range 10 nM to 5 μM Disadv.: long reaction time (2 h for detection) Application: cellular endogenous H2S gas. |

[173] |

| Dopamine functionalized AgNPs | Decrease in the plasmon absorbance of AgNPs at 400 nm with a color change from bright yellow to dark brown observed by the naked eye. |

Adv.: environmentally friendly, LOD 0.03 µM Disadv.: narrow linear range from 2 to 15 µM, Application: fetal bovine serum |

[174] |

| PPF-AgNPs | Decrease in PPF-AgNPs absorption band at 400 nm upon reaction with H2S |

Adv.: good sensitivity and specificity, fast response time Application: various biological and environmental samples |

[103] |

| Ag/Au core–shell nanoprism | Decrease in Ag/Au core–shell nanoprism absorption band at NIR region upon reaction with H2S |

Adv.: SPR peak is located in the NIR region Disadv.: long time (30 min) Application: serum |

[104] |

| Decrease in Ag/Au core–shell nanoprism absorption band at NIR region upon reaction with H2S |

Adv.: HS-SDME methodology, smartphone nanocolorimetry based detection set up, sensitive LOD 7 nM (UV − vis), and 65 nM(SCN). Application: egg and milk |

[175] | |

| Au–Ag core–shell | Quantification of RGB color variation of the Au–Ag core–shell resulting from the formation of Ag2S on the particle surface. |

Adv.: RGB colorimetric analysis, linear (50 nM to 100 μM) Disadv.: long time (20 min) Application: cell culture medium and the blood serum |

[176] |

| Au/AgI dimeric nanoparticles | The color variation of the Au–Ag core–shell due to the formation of Ag2S on the particle surface. AgI increases the probe selectivity |

Adv.: linear (0 to 80 μM) with LOD of 0.5 μM (UV–vis spectrophotometer) Application: HepG2 cell |

[105] |

| Glutathione capped AuNPs | AuNPs aggregation upon reaction with H2S via ligand exchange reaction which results in a color change from red to purple/blue |

Adv.: simple Disadv.: lower sensitivity level LOD (5 μM with a UV/vis spectrophotometer |

[106] |

| Fluorosurfactant functionalized gold nanorods (FSN-AuNRs) | FSN-AuNRs exhibits blue color changing to purple upon reaction with H2S due to surface ligand substitution and aggregation of FSN-AuNRs |

Adv.: capable of evaluating the activity of CBS Application: human and mouse serum samples |

[107] |

| Au@TPt-NCs | Deactivation of the Au@TPt-NCs catalytic activity on (TMB / H2O2 system) upon reaction with H2S |

Adv.: static headspace extraction was applied, with LOD 7.5 nM Application: newborn cattle serum |

[108] |

| AuNRs | Deactivation of etching activity of (TMB /HRP) on AuNRs upon reaction with H2S |

Adv.: linear range 0.05–50 μM with a LOD of 19 nM Application: monitoring extracellular H2S in rat brain |

[177] |

Classical colorimetric methods

One of the earliest and most common methods used for H2S measurements is the methylene blue reaction of sulfide with N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine, in the presence of ferric chloride to yield a blue color that could be measured spectrophotometrically at 670 nm [96]. The method was later modified by trapping H2S with zinc acetate to remove interference from other chromophores that might be present in the sample followed by acidification and subsequent formation of the dye [97]. However, several critical issues were observed when H2S was determined in biological samples viz., lack of selectivity and sensitivity, formed dimer and trimer of methylene blue that do not obey Beer’s law, and finally, color formation is time-dependent which requires careful monitoring. On the other hand, Pluth's group reported a colorimetric method based on thiolysis of NBD-derived electrophiles; NBD-Cl reacts with H2S via nucleophilic aromatic substitution reaction to form thioether followed by thiol formation of the unique color of NBD-SH (Pluth red) [98]. This method exhibited detection limit as low as 210 nM (buffer) and 380 nM (fetal bovine serum) and high selectivity for H2S even in the presence of other biologically-relevant nucleophiles such as glycine, serine, tyrosine, lysine, glutathione, and N-acetyl-cysteine. In another report for colorimetric H2S determination, a new azine based sensor was developed for the selective determination of H2S in physiological conditions. The method is based on deprotonation of one of the sensor –OH protons via reaction with H2S resulting in a color change detected at 450 nm. The azine sensor exhibits a detection limit at 18.2 μM and has been applied successfully for H2S quantitation in spiked mouse and human sera [95].

Displacement of copper complexes

Another colorimetric approach used for H2S determination is through displacing a metal from its coordinated chromophore via metal sulfide formation resulting in a color change. This approach has been widely employed for H2S measurement due to its rapid response, reversibility, and robustness. Among the different metals-ligands displacement systems, copper complexes are the most widely employed sensors for H2S analysis due to the very low solubility product of the formed CuS. Asides, the outstanding plasticity of the copper sphere facilitates Cu-complexes formation with a variety of chelating ligands [31].

Copper complex of 1-(2-pyridylazo)-2-naphthol was synthesized for the colorimetric sensing of aqueous sulfide with a pink to yellow color change upon displacement of Cu2+ from its complex [99]. Interestingly, the same probe has been developed for the quantification of gaseous H2S via impregnating the probe with alkali on paper support [100]. The alkali will trap and convert the acidic H2S gas to sulfide ion with a color change from pink to yellow. The probe could be coupled with a handheld colorimeter and a smartphone allowing quantification of H2S gas or for its rapid detection with LOD of 16 ppb of gas. In another study, BODIPY and 8-aminoquinoline were incorporated for designing a colorimetric probe employed for H2S detection. The probe forms 1:1 complex with Cu2+ in HEPES buffer with a decrease in the absorption band at 569 nm and an increase of a new band at 520 nm with a color change from pink to orange in rather fast reaction time. This method displays excellent selectivity towards sulfide over other competitive anions and thiols and with LOD of 0.167 μM in aqueous media [92].

Nanomaterials based colorimetric analysis

A recent colorimetric approach used for H2S detection and quantification is based on the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) optical traits of metal nanoparticles e.g. Ag NPs and Au NRs [19]. Compared to conventional colorimetric methods, plasmonic metal nanoparticles provide an exciting avenue for rapid and accurate determination of H2S due to its higher photostability, lower photobleaching and intensity fluctuations, much higher scattering cross-section and extinction molar coefficients (REF). Exploiting the affinity of Ag+ to S2-, a wide range of colorimetric methods have been developed for H2S determination. For example, Jaroszx et al. [101] reported a microplate-based colorimetric assay using Nafion polymer doped with Ag+ ions for H2S determination. Nafion polymer served as a template for Ag NPs synthesis where the formed Ag2S NPs showed a strong UV absorbance at 310 nm. The same principle has been implemented in another study where polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) was utilized for Ag NPs construction being applied for measuring endogenous H2S concentration in living C6 glioma cells [102]. Cross-linked polymer cages have been also employed as a potential medium for novel Ag NPs fabrication that was used in H2S determination e.g. cross-linked polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane-formaldehyde polymer (PPF) [103]. PPF-AgNPs exhibit strong absorption at 400 nm which decreased quantitatively upon reaction with H2S due to the formation of Ag2S shell on the surface of PPF-AgNPs. The PPF-AgNPs exhibited excellent selectivity towards sulfide against other thiols and anionic species due to the specific Ag–S interaction within a linear range of 0.7–10 μM and a detection limit of 0.2 μM. Analysis of H2S in various water and biological samples e.g. spring waste, urine, human serum and fetal calf serum using this novel probe have been demonstrated.

It is worth to note that some reports raised though doubt about the selectivity of silver nanoprobes for H2S quantification, particularly in real samples with complicated matrices due to their susceptibility for oxidation in the presence of coordination agents such as hydrogen peroxide. Hence, several approaches were attempted to increase the selectivity of these nanoprobes via silver coating with a thin gold layer to form Ag/Au core–shell nanoprism that protect Ag from direct reaction with interfering species thus increasing the latter’s selectivity toward H2S [104]. The defects in gold outer layer lateral walls allow reaction of only strong etching agents such as hydrogen sulfide with Ag nanoprisms and mitigate against interaction with other anions. This method exhibited a wide linear dynamic range from 0.1 and 10 μM with a detection limit of 54 nM and was applied for H2S detection in serum. Interestingly, the same core–shell nanoprism has also been used in another study coupled with headspace single-drop microextraction (HS-SDME) to quantify H2S. Smartphone nanocolorimetry (SNC) and UV − vis spectrophotometry were utilized to measure the change of Ag/Au core–shell SPR peak as a result of H2S etching and both to demonstrate potential application for determining H2S levels in real biological samples (egg and milk). In contrary to previous reports that employed Au as a protective shield for Ag NPs, Zeng et al [105] reported another strategy to increase Ag NPs selectivity based on engineering Au/AgI dimeric nanoparticles where the AgI acts as sensing agent and the Au acts as the signal-receptor core. Based on the fact that AgI exhibits the lowest solubility product among all silver halides, very few interfering compounds can react with stable AgI shell. These Au/AgI NPs have been immobilized into agarose gels to produce a solid form of “test strips” that has been applied successfully to determine H2S gas concentrations released from Hep G2 cells during their cultivation.

Similar to AgNPs, AuNPs have been also widely used for H2S determination due to the strong Au-S interaction. Such assays are based on the induction of AuNPs aggregation by inter-AuNPs crosslinking to result in color changes that can be easily observed by naked eyes (qualitative) or spectrophotometers (quantitative). For example, glutathione capped AuNPs have been used as an H2S sensor via a ligand exchange reaction where sulfide will replace glutathione molecule on the AuNPs surface resulting in AuNPs aggregation and subsequent color change [106]. In a similar study, non-ionic fluorosurfactant capped with gold nanorods (FSN-AuNRs) has also been reported for the determination of H2S [107]. In contrary to AuNPs, gold nanorods (AuNRs) possess two plasmon absorption bands responsible for their unique color change upon H2S induced aggregation. This method exhibits high specificity towards sulfide over other anions and has been applied successfully for the determination of biological H2S in both human and mouse serum as well as determining the activity of cystathionine β-synthase activity, the enzyme responsible for H2S production. Interestingly, another AuNPs colorimetric strategy used for H2S quantitative estimation is based on the H2S-induced deactivation of (gold core)@(ultrathin platinum shell) nanocatalysts (Au@TPt-NCs) [108]. Upon target introduction, Au@TPt-NCs were deactivated to different degrees depending on H2S levels, static headspace extraction was used with the Au@TPt-NCs as an effective sample pretreatment method for this system. This method displayed higher sensitivity for H2S determination with a linear range of 10–100 nM and LOD of 7.5 nM. Asides, the method was applied for H2S measurement in spiked real samples such as newborn cattle serum and although it is expedited route for the sensitive determination of biological H2S in vitro samples, it has not been validated yet in vivo.

Phosphorescence analysis

Unlike fluorescence, phosphorescence is characterized by much longer emission lifetime which demonstrates its superiority in the bioimaging field [109]. Besides, the slow process of light re-emission entails the elimination of autofluorescence short-lived interference and improves S/N ratios. Among different phosphorescence probes for H2S determination, transition metal complexes are known for their simple synthesis procedures and easy tuning of photophysical properties [110]. Novel iridium (III)-based luminescent turn on–off-on probe has been developed for the in vitro and in vivo determination of sulfide ion [111]. This method is based on quenching of iridium (III) probe by Fe3+, followed by restoring its luminescence upon the addition of sulfide. The probe exhibited a linear range from 0.01 to 1.5 mM, with LOD of 2.9 μM, and was successfully applied for sulfide imaging in living cells. In another report, an H2S-associated phosphorescence turn-on probe was developed based on the in situ capturing of sulfide by Zn2+ and Mn2+ to form Mn-doped ZnS quantum dots [112]. These dots emit orange phosphorescence allowing elimination of autofluorescence interference from biological matrix and was thus employed for H2S quantification in fetal calf serum with LOD of 0.2 μM.

Chemiluminescent analysis

Unlike other analytical techniques, chemiluminescence (CL) methods offer higher sensitivity and the wide dynamic range since the CL signal can be generated in the absence of any light sources which eliminates any background signal and improves the signal to noise for in vivo studies. Hence, they have been widely applied for the detection of disease biomarkers [113], [114], including H2S.

Among different CL systems, the reaction between luminol and hydrogen peroxide in the presence of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) as a catalyst is widely applied due to its simplicity and enhanced CL signal intensity. This triple system has been applied recently for H2S determination in which H2S deactivates HRP resulting in CL quenching of the system in a quantitative manner [115]. The method exhibits a linear dynamic range of 0.78–40 μM with a detection limit of 0.30 μM and has been applied successfully for H2S determination in rat brain microdialysis. Another method used the irreversible reaction of H2S with two masked azide-luminol scaffolds has been reported [116]. H2S mediates the reduction of the azide moiety liberating luminol or isoluminol with enhanced CL intensity in the presence of H2O2 / HRP. The isoluminol based probe displays excellent selectivity for H2S over a wide range of other biologically relevant reactive sulfur species, including thiols. Hence, it has been applied to measure the enzymatically produced H2S effectively.

Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) is another luminescent process where an electrochemical reaction is employed to generate excited luminophore on an electrode surface via electron-transfer reactions [117]. ECL systems have been widely applied in H2S detection due to their simplified optical setup, superior sensitivity, and low background signal level. For example, a cyclometallic iridium(III) complex has been synthesized as luminophore with high ECL intensity during cyclic voltammetry that quenches upon reacting with H2S [118]. ECL signal of the system decreased linearly upon reacting with H2S over a concentration range 40–140 μM with an estimated LOD of 11 nM. Another sensitive ECL was developed based on quenching ECL signal of the activated CdS nanocrystals film upon reaction with H2S on a glass carbon electrode, in presence of other co-reactants such as H2O2 and citric acid, via bonding of sulfide to excess Cd2+ ions on the nanocrystals surface [119]. The method showed a wide linear range spanning from 5 nM to 20 μM and has been successfully applied for the determination of H2S in calf serum. Furthermore, NBD-amine, a sensitive compound to H2S, has been integrated with Ru(bpy)32+-doped silica nanoprobe for sulfide quantification [120]. Nafion was used to immobilize Ru(bpy)32+-doped silica on the surface of a glassy carbon electrode. The methods showed a linear range from 0.1 to 1 × 10-4 nM, LOD 1.7 × 10-6 nM and applied successfully to spiked human serum.

Cataluminescence (CTL) is another type of chemiluminescence in which the catalytic oxidation of analytes occurs on the surface of a solid material [121]. Among different types of CTL, metal-based catalysts represent the main type that exhibits high sensitivity for H2S determination namely mesoporous SnO2 [122], α‐Fe2O3 [123], [124], microsphere In2O3 [125] and several alkaline‐earth metal salts viz., CaCO3, SrCO3 and BaCO3 [126]. Also, metal–organic frameworks are also used for H2S determination due to their large surface area, good thermal stability, and metal catalytic sites. ZIF-8 and Zn3(BTC)2·12 H2O are two examples of metal–organic frameworks whose LODs are 3.0 and 4.4 ppm for H2S analysis, respectively [127]. Nevertheless, metal-based catalysts suffer from high cost, environmental pollution by heavy metals, and poor long-term stability. Albeit, these limitations can be overcome using metal-free catalysts such as nanocarbon catalysts which are stable on the long-terms, environmentally friendly, cost-effective, and highly selective. Silicon carbide (SiC) is a promising metal-free carbon material with distinct catalytic potential that has been enhanced by controlling its morphology through ion doping with fluorine [128]. SiC CTL signals display a linear relationship for H2S quantitation in the range of 6.1–30.4 ppm with LOD 3.0 ppm.

Chromatographic methods

Although chromatographic methods for H2S analysis could not be applied for real-time monitoring, they offer higher selectivity and specificity compared to direct spectrophotometric or fluorescence measurements. Separation technique as gas and liquid chromatography coupled to different sensitive detectors are considered as the mainstays for analysis of biological samples [38]. Chromatographic techniques are applied for H2S detection in a wide range of biological matrices including breath [129], saliva [130], heart tissue, and urine [131], plasma, tissue, and cell culture lysates [26].

Chromatographic methods used in H2S analysis include:

-

i)

GC coupled to different detectors as electrochemical [132], electron capture [133], flame photometry [134], mass spectrometry [135], [136], ion mobility spectrometry [137].

-

ii)

LC coupled to different detectors as spectrophotometry [138], spectrofluorimetry [139], atomic fluorescence spectrometry [140], mass spectrometry [141], and electrochemical [142].

These chromatographic coupled techniques represent the most used chromatographic methods for H2S analysis. However, these coupled techniques were used for different applications i.e., ion chromatography coupled to electrochemical detector was used for sulfide determination in water [143], in rat and human brain tissue [144], in rat brain different regions (brainstem, cerebellum hippocampus, striatum, and cortex) [145], in its liberation by the dithiothreitol treatment of brain tissue [146], in organic-rich, anaerobic waters from peat bogs [147], and in gastrointestinal contents and whole blood [142].

Generally, pre-column derivatization, (i.e., with methylene blue, pentafluorobenzyl bromide, etc) is required for H2S detection. Therefore, during the derivatization step, the biomolecule-bound sulfur pool presents significant interferences during the analysis of biological samples alongside rigorous analytical precautions to be followed [22], [148]

H2S exists either in a gaseous state (unionized form) or liquid phase (unionized and two ionized forms). Unionized H2S could be directly trapped (gaseous state) or liberated from its liquid phase in the headspace above the sample and was then directly analyzed by GC coupled to different detectors, as flame photometry and sulfur chemiluminescence detection. While H2S in the liquid phase generally needs precolumn derivatization followed by GC or LC analysis [149]. Table 3 summarizes the analysis of sulfide using different chromatographic methods. Gas chromatographic analysis of sulfides was initially carried out via its pentafluorobenzyl derivative detection using mass spectrometry [150]. This technique was applied to post mortem analysis in forensic studies for sulfide fatal toxicity [151] and to investigate blood sulfide as a marker of bowel fermentation processes [93]. Later on, sulfide analysis was achieved in the headspace for tissue homogenates [38] or post silylation in human sera [152]. GC–MS analysis of human breath revealed the contribution of H2S in oral malodor and halitosis [129]. Moreover, GC–MS analysis of human serum revealed elevation of H2S level in a certain serious type of heart attack (ST-elevation myocardial infarction) [152].

Table 3.

Representative examples of certain chromatographic methods for H2S analysis.

| Chromatographic method | Properties and applications | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ion-interaction RP-HPLC /spectrophotometry |

Adv.: relatively simple protocol (methylene blue formation) Disadv.: need pre-column derivatization of sulfide, affect acid-labile sulfides Application: brain tissue and rumen fluid of cattle |

[138] |

| 2 | Micro distillation/ ion chromatography / fluorescence detection |

Adv.: acceptable recoveries (94–101%) Disadv.: low sensitivity (2.5 µM), non-selective for free sulfides (bound form/acid-labile), long preparation time (3 hrs/50℃) Application: gut contents (0.2 to 2.8 µmol/g wet feces) and whole blood sulphide (10–100 µM). |

[142] |

| 3 | RP-HPLC / fluorescence |

Adv.: sensitive (0.02 pmol) Disadv.: need pre-column derivatization of sulfide with monobromobimane, long incubation time (30 min), long analysis time (~20 min) Application: plasma of mice |

[26] |

| 4 | RP-HPLC/mass spectrometry (ESI) |

Adv.: good linear range 1–1000 nM, uses a novel stable isotope-coded (2-iodoacetanilide) Disadv.: used precolumn derivatizing agent (2-Iodoacetanilide) Application: HepG2 (750 µM) cells in vitro |

[141] |

| 5 | Gas dialysis/Ion chromatography/ electrochemical detection |

Adv.: 95–99% Recovery Disadv.: need gas dialysis pretreatment, post-mortum analysis & couldn’t be applied for real-time monitoring Application: rat and human brain |

[144] |

| 6 | HS-GC–MS (EI) |

Adv.: generation of H2S in hermetically closed GC headspace vials, use a specific H2S internal standard (N2O), Disadv.: relative narrow linear range (12.5 – 62.5 µM), low sensitivity LOD (1 µM), at high concentration of CO2, it coelutes with the internal standard (N2O) & consequently affects H2S quantification Application: quantify H2S in H2S fatal intoxication cases (post-mortem) |

[178] |

| 7 | GC/MS (full scan) |

Disadv.: requires a derivatization step and provide relatively not absolute amounts Application: blood (serum) |

[136] |

| 8 | GC–MS (SIM mode) |

Adv.: sensitive (96 ng/ml), linear range (10 – 100 µM) Disadv.: long incubation time (4 h) with a derivatizing agent (pentafluorobenzyl bromide), the possibility of interference of GSH & sulfur-containing amino acids Application: whole blood, blood levels of sulphide of healthy controls (35–80 μM) |

[93] |

| 9 | GC/sulfur chemiluminescence detection |

Adv.: selective, sensitive (15 pg/injected sample), rapid analysis time (H2S less than 2 min), linear range (0 – 14 ng/injected sample) Disadv.: time-consuming for sample preparation and GC run cycle. Application: artificially induced H2S production in tissue homogenate |

[179] |

A coupling electrochemical detector (ECD) with ion chromatography (IC) was applied for the determination of the sulfide in brain tissue. However, the main limitation resides in the liberation of the acid-labile sulfur during the high acidic extraction protocol [22]. Another example of IC coupled to ECD was investigating the protein-rich diet effect on sulfide level in the gut contents and whole blood [142]. Monobromobimane was the derivatizing agent for H2S in alkaline medium (pH 9.5) and analyzed by HPLC coupled with fluorescence detection which offers good sensitivity compared to that obtained with the methylene blue method [26], whereas via coupling with a mass spectrometer, (ESI–MS), it surpasses other methods concerning sensitivity and specificity[141].

A validated liquid chromatography-masss spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method for the determination of H2S in various biological matrices by determination of a derivative of hydrogen sulfide and monobromobimane named sulfide dibimane (SDB) was used to measure its levels in a broad range of biological matrices, such as blood, plasma, tissues, cells, and enzymes, across different species [153]. The later technique revealed diurnal H2S fluctuations in mice plasma [154].

Our aim in this review is not though to provide an inclusive overview of all chromatographic methods used in the assessment of biological H2S, but rather to highlight certain examples of chromatographic techniques available as tools for its determination.

Electrochemical determination of H2S

Electrochemical methods offer an improved expedited route for real-time detection of H2S in biological samples due to their low detection limit, high sensitivity and selectivity, miniaturization capabilities, fast response time, and absence of chemical reagents [21]. Among different types of electrochemical sensors, potentiometric ion-selective electrodes and polarographic sensors have been employed extensively for H2S determination in biological samples.

Ag/Ag2S ion-selective electrode (ISE) is one of the most commonly used potentiometric methods for measuring sulfide ion in biological systems. This method was first reported fifty years ago by Mason et al. for measuring sulfide concentration in plasma with limited details of the methodology [155]. A full detailed procedure for plasma sulfide concentrations measurement using this electrode was later reported by Khan et al. [156]. Orion Research used this method to develop a commercial sulfide sensitive electrode (Model 9616, Orion Research, Beverly, MA) that has been widely used in serum H2S measurement [157]. Interestingly, Lazar Research Laboratories (Los Angeles, CA) has developed another small commercial Ag/Ag2S ISE known as ArrowH2S™ that measures H2S in volumes down to 10 µl directly in its micro containers with 100 nM detection limit, thus preventing H2S loss from the sample and increasing the accuracy of its measurement [7]. However, Ag/Ag2S electrodes exhibit some disadvantages such as the requirement for rendering the medium alkaline via adding “antioxidant buffer” to shift the H2S equilibrium into the S2− ions which are the only form of H2S that the electrode can measure [158], [159]. Asides, the electrode must be reconditioned (typically for 1 h in 5 mM Na2S) to ensure that no silver is exposed to the surface otherwise, selectivity is lost [160]. Other potentiometric sulfide sensors based on the reversible electrochemical reaction of a redox mediator viz., ferricyanide and conductive polymer as sensing film have been also reported [161], [162]. These methods exhibit high reproducibility and sensitivity.

Polarography is another reliable electrochemical technique that has been applied for the determination of H2S in whole blood and tissues [21]. It has the advantage of real-time monitoring even for free H2S gas without altering the sample. The first polarographic sensor used for H2S determination in biological samples is based on a Clark-type oxygen electrode [163]. Platinum wires were used as the anode and cathode altogether with an alkaline K3[Fe(CN)6] as an internal electrolyte solution held in the sensor tip reservoir using H2S-permeable membrane and a sensor housing of polyether ether ketone. During H2S measurement, [Fe(CN)6]3− is reduced to [Fe(CN)6]4− while H2S gas is oxidized to HS− then S0 upon its permeation through the membrane layers. A current proportional to H2S concentration is produced upon electrochemical oxidation of [Fe(CN)6]4− back into [Fe(CN)6]3− on the surface of the platinum electrode. Following this sensor, another miniature polarographic H2S sensor was developed having several advantages including sensitive detection limit (10 nM) and low response time (20–30 s) posing it as an ideal sensor for kinetic studies of H2S metabolism in broken cell systems, intact tissues, and whole organisms [164]. Moreover, the sensor could be combined with other real-time polarographic sensors such as polarographic oxygen sensor and polarographic nitric oxide sensor owing to its higher selectivity to determine the correlation of these species with H2S in biological systems. Additionally, an ultra-micro polarographic H2S sensor having a diameter of only 100 μm has been developed offering several advantages, including durability for long-term use, rapid response time, and absence of sleeves and filling solutions [21]. Despite the numerous advantages for H2S polarographic sensors as one of the widely used techniques for real-time H2S measurement, their main disadvantage lies in the necessity of liquid electrolytes in their design which are prone to dryness and leakage in addition to the possible large residual current associated with impurities in the samples.

Conclusion

Owing to the major clinical importance of H2S as the third gasotransmitter, a wide variety of quantification methods have been developed for its measurement in biological systems. In contrast to colorimetric, ion-selective electrodes, and chromatographic methods, fluorescence offers an attractive non-invasive and promising approach accounting for the substantial increase in the number of newly developed fluorescent probes in the past few years. Although a lot of effort has been made towards fluorescence imaging, it faces challenges such as the low levels of endogenous H2S and the presence of many interfering bio-molecules. Asides, tissue penetration, fluorophore stability at high excitation wavelengths have also largely limited their application for in vivo H2S quantification. Although fluorescence sensors offer good selectivity they cannot be considered as H2S-specific probes, as biothiols may interact, even at a lesser extent, with these sensors. Consequently, significant work has to be done towards developing highly sensitive and selective fluorescent probes for such purpose. Promising fluorescent probes, for monitoring the endogenous short-lived H2S, are expected to meet certain requirements, such as a photostability, NIR optical window, enhanced fluorescence, fast and sensitive response, specificity or high selectivity, water solubility and low cytotoxicity. On the other hand, colorimetric assays are among the earliest and most common methods used for in vitro H2S detection, however, their employment in vivo H2S measurement has not yet been possible even after the introduction of plasmonic metal nanoparticles that have provided an expedited route for rapid and accurate detection of H2S in plasma. Separation techniques as gas or liquid chromatography offer higher selectivity compared to direct spectrophotometric or fluorescence H2S measurements, albeit they also could not be applied for H2S real-time monitoring. These methods are suitable for endpoint measurements i.e. plasma or tissue samples. Despite a myriad of developed analytical procedures used for H2S determination, the need for highly selective, highly sensitive, biocompatible, reproducible, and accurate H2S measurement methods seems imperative to untangle the non-resolved pitfalls of the current methods.

Compliance with ethics requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Farag thanks Jesour grant number 30, Academy of Scientific Research and Technology, ASRT, Egypt for funding.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

References

- 1.Zheng Y., Yu B., De La Cruz L.K., Roy Choudhury M., Anifowose A., Wang B. Toward Hydrogen Sulfide Based Therapeutics: Critical Drug Delivery and Developability Issues. Med Res Rev. 2018;38(1):57–100. doi: 10.1002/med.21433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li L., Moore P. Putative biological roles of hydrogen sulfide in health and disease: a breath of not so fresh air? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29(2):84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide as a neuromodulator. Mol Neurobiol. 2002;26(1):13–19. doi: 10.1385/MN:26:1:013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunha T.M., Dal-Secco D., Verri W.A., Guerrero A.T., Souza G.R., Vieira S.M. Dual role of hydrogen sulfide in mechanical inflammatory hypernociception. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;590(1):127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elrod J.W., Calvert J.W., Morrison J., Doeller J.E., Kraus D.W., Tao L. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104(39):15560–15565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705891104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang G., Wu L., Jiang B., Yang W., Qi J., Cao K. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine gamma-lyase. Science (New York, NY) 2008;322(5901):587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1162667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]