Abstract

Nonlinearity plays a fundamental role in the performance of both natural and synthetic biological networks. Key functional motifs in living microbial systems, such as the emergence of bistability or oscillations, rely on nonlinear molecular dynamics. Despite its core importance, the rational design of nonlinearity remains an unmet challenge. This is largely due to a lack of mathematical modelling that accounts for the mechanistic basis of nonlinearity. We introduce a model for gene regulatory circuits that explicitly simulates protein dimerization—a well-known source of nonlinear dynamics. Specifically, our approach focuses on modelling co-translational dimerization: the formation of protein dimers during—and not after—translation. This is in contrast to the prevailing assumption that dimer generation is only viable between freely diffusing monomers (i.e. post-translational dimerization). We provide a method for fine-tuning nonlinearity on demand by balancing the impact of co- versus post-translational dimerization. Furthermore, we suggest design rules, such as protein length or physical separation between genes, that may be used to adjust dimerization dynamics in vivo. The design, build and test of genetic circuits with on-demand nonlinear dynamics will greatly improve the programmability of synthetic biological systems.

Keywords: mathematical modelling, genetic circuits, nonlinearity, systems biology, synthetic biology, protein dimerization

1. Introduction

Synthetic biology [1–3] is a growing field of research that uses engineering principles to design and implement human-defined computations in living cells. The development of complex mathematical modelling techniques [4,5], along with the advances in DNA synthesis and assembly [6], allows for the making of new-to-Nature networks of regulatory proteins—the so-called genetic circuits—with increasing information processing abilities. Relatively simple models of computation, like combinatorial [7] and sequential logic [8], have been successfully implemented in organisms such as bacteria [9], yeasts [10] or even mammalian cells [11]. Examples of these genetic circuits include logic gates [12,13], multiplexers [14], half-adders [15], counters [16] and memories [17]—and even more complex processes such as analogue [18,19] and distributed computations [20–22]. As well as generating fundamental insights into the workings of living systems, this (and many more) engineered system finds a broad range of applications in biotechnology and bioengineering [23,24]. Nevertheless, it could be argued that the field is in its infancy, since the vast differences between traditional silicon-based hardware and biological substrates suggest that there are powerful models of computation yet to be developed [25]. That is, the way synthetic constructs process information cannot get even close to that of natural biological systems.

Mathematical modelling, an essential component of synthetic biology, aids the design of increasingly complex genetic circuits by providing predictions of their dynamical performance [26,27]. By modelling the dynamics of gene expression (i.e. mechanistic steps going from genes to proteins), designs can be improved with information such as which DNA components are predicted [28] to perform better for a specific target function. That is, models answer questions that are difficult, if not at all impossible, to answer otherwise. However, the predictive power of models depends on the detail of the description of the physical processes they represent. There is one such process that, despite being of fundamental importance for genetic circuits and biological computation, has received relatively little attention to this end: the mechanistic understanding of nonlinear dynamics [29–32]; specifically, because of its relevance for genetic circuits, the nonlinearity that emerges from the dimerization of regulatory proteins [33]. Although dimerization is a well-known source of nonlinear dynamics, current mathematical models fail to provide a mechanistic description of it. The goal of this study is to overcome such limitations. Upon gene expression, most resulting proteins are monomers that need to interact to form dimers (or higher-order oligomers); it is only the protein in its final from that is active. Furthermore, dimerization is intertwined with other sources of nonlinearity [34], such as regulator–promoter interplay [35] (known as bursting). In the early days of synthetic biology, two landmark papers demonstrated that such nonlinear dynamics are at the core of relatively simple circuits. The first one implemented a ‘toggle switch’ [36]: a genetic circuit able to switch between two states according to external signals. The second one implemented what was called the ‘repressilator’ [37]: an oscillator based on a circuit of gene transcription repressors. Mathematical models of these two circuits show bistability and reliable oscillations (respectively) only if they account for nonlinear dynamics.

A non-trivial issue is that protein monomers have to meet in order for dimerization to happen. But, where do they meet? Nearly, 30 years ago, a paper titled ‘[…] it takes two to tango but who decides […] on the venue?’ [38] fired this question explicitly; soon after, another paper found experimental evidence for what they called co-translational dimerization [39]. The latter work established a difference between co-translational, which takes place during translation (from RNA into proteins), and post-translational dimerization pathways. However, current mathematical modelling accounts for the dimerization of proteins using abstract parameters without physical description. These parameters do not have a direct physical translation, which is abstracted away. That is, the values of these parameters do not inform us about specific mechanistic details that could be engineered in vivo. While Michaelis–Menten equations, for instance, use integer values for a physical parameter, Hill equations allow for unphysical non-integer values. Although somewhat effective, these modelling approaches abstract away dimerization into a black box, thus hiding it from the design process. The lack of description of the molecular details of nonlinearity limits the rational design of such behaviour. In contrast to prevailing approaches, our model aims at breaking that abstraction by providing parameters with direct physical interpretation. Therefore, the values of the parameters presented below correspond to the rules and principles that can be applied at the design stage in order to engineer a DNA device with an on-demand nonlinear behaviour.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. A model for co-translational dimerization

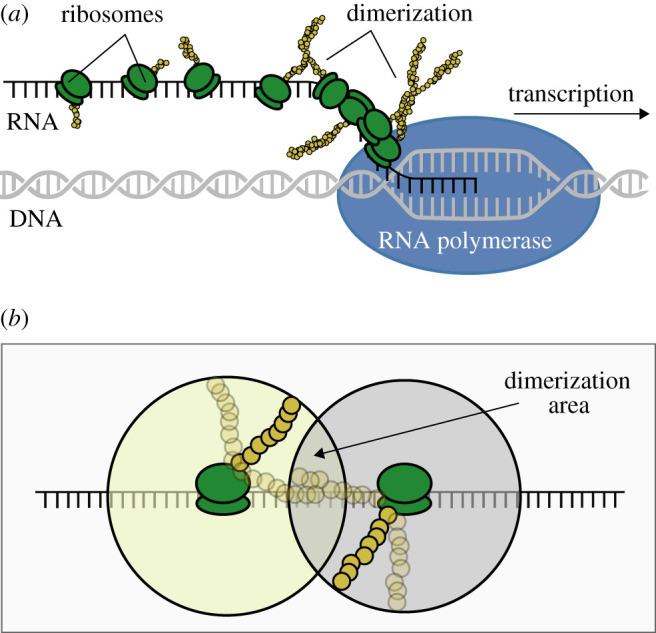

Transcription (of a gene into RNA) and translation (of RNA into proteins) rarely generate fully functional transcriptional regulators. Rather, the resulting proteins—or ‘monomers’—need to interact with others in order to form ‘dimers’ (figure 1a); for example, the repressor protein TetR, which is extensively used in synthetic biology, is a dimer. This suggests that any mathematical model that aims at simulating the dynamics of such a molecule (or that of a genetic circuit regulated by it) must account for the dimerization of the partially formed regulators generated after translation in order to result in robust predictions.

Figure 1.

Co-translational dimerization. (a) Upon DNA transcription by RNA polymerase, ribosomes bind the resulting RNA to translate it into proteins. There is more than one translation process at a given time, and ribosomes go along the RNA at different speeds, leading to the appearance of traffic jams. Our model simulates the process by which, when distance among ribosomes is short, partially formed monomers (represented in the figure by chains of yellow circles) dimerize with other partially formed monomers as they are being translated. (b) Detail of the translation-mediated dimerization area. The extension of this region depends on several physical features, such as the length of the protein to be translated or the distance between ribosomes; these constraints will affect nonlinearities due to protein dimerization.

Although typical modelling frameworks, such as Michaelis–Menten and Hill equations, already account for dimerization, matching this to its specific molecular mechanisms and features (in contrast to using abstract cooperativity values) is still an overarching challenge. Our model adds a detailed mechanism of translation, in which ribosomes bind RNA molecules in an asynchronous fashion; as a result, some ribosomes start translating very close to each other [40]. In this scenario, two partially formed monomers come into contact and dimerization starts, which has been termed co-translational dimerization (figure 1b) [39]. When ribosomes are at a long-enough distance apart, dimerization will take place in the cytoplasm (i.e. post-translational dimerization), where both monomers must meet before building a dimer. The model presented here accounts for these dynamics, which, in turn, shape the nonlinearity features (in final dimer formation) of the genetic circuit at stake.

In order to describe co-translational dimerization rates, the model first assumes that the arrival of a ribosome at the RNA is captured by a Poisson point process since discrete events occur independently at a given rate. The distribution of time between binding events (P(Δt)) is then given by the following equation:

| 2.1 |

where λ is the average binding rate of a ribosome to the RNA (i.e. when translation initiates), and Δt represents the time between such binding events. This time distribution, along with the experimentally obtained translation rate of ca 10 AA s−1 [41,42] (AA = amino acids), was used to calculate the distance between two consecutive ribosomes (Δx) and the length difference of the partially translated monomers being generated by them (Δr).

To calculate the fraction of dimerization that takes place during translation (versus after translation), the model defines the area where partially formed monomers can interact (figure 1b). While monomers are being formed, they are bound to the ribosome at one end and move within a sphere around the ribosome (with a radius based on the current length) at the other end. Although more complex geometries than a sphere may capture the monomer’s movements more accurately (e.g. a cone with continuously updated coordinates according to mRNA shape/orientation), the lack of experimental information on this makes it virtually impossible to define such a volume. Therefore, this model assumes a spherical movement around the ribosome bound to the mRNA. If two monomers are long enough, the volume where the spheres overlap shows where the monomers can interact. In this state, co-translational dimerization may start. The relative volume for these overlapping spheres (with distance between origins Δx and radii r and r + Δr) is

| 2.2 |

where the output is a relative value going from 0 (no overlap at all) to 1 (complete overlap of partially formed monomers), Δx is the distance between two ribosomes and r is the current length of the least transcribed monomer (see Methods for model derivation). The creation of dimers at each specific time difference and at a specific protein length is assumed to obey Michealis–Menten dynamics. Therefore, the calculation of the fraction of dimerization during translation (α) is given by the following equation:

| 2.3 |

where Rprotein is the final length of the protein and kD is a rate termed the reaction parameter that accounts for the likeliness of two AA chains dimerizing when they coexist in the same volume (a detailed derivation is available in the electronic supplementary material). Only after the calculation of whether or not two monomers meet/collide can the independent parameter kD determine if dimer formation occurs.

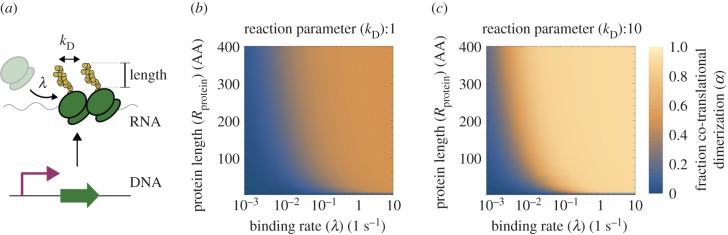

Figure 2 shows the resulting fraction of co-translated dimerization (α) in relation to key model parameters (figure 2a): the binding rate of the ribosomes (λ), the length of the monomers (measured in AAs) and the reaction parameter (kD). These results are shown for two different values of the reaction parameter (dimensionless), 1 (figure 2b) and 10 (figure 2c), at experimentally obtained values for the binding rate [43], λ ≈ 0.1 s−1. As observed here, α is a minimum (from 0 to ≈0.2) at lower values of λ and protein length; however, λ is the limiting rate here, since at very low values the protein length does not make a difference. This suggests that a very low binding rate (or low ribosome availability) would result in having no co-translational dimerization—or small values which could be neglected. However, as soon as λ increases, α gains importance, and this is also amplified by increasing the reaction parameter kD. This is because the more λ increases, the more ribosomes will bind to the RNA within a given time interval; as a consequence, ribosomes will be physically closer while translating and partially formed monomers will tend to overlap more (i.e. higher values at equation (2.2)).

Figure 2.

Mechanistic principles of co- versus post-translational dimerization dynamics. (a) Diagram showing the modelling parameters affecting dimerization types: ribosome binding (λ), the rate at which two partially formed monomers interact (kD) and protein length. (b) At a rate where monomers interact weakly (kD = 1, dimensionless) the fraction of co-translational dimerization (i.e. the total dimerization minus the dimerization in the cellular cytosol, divided by the total), α, as described by equation (2.3), responds primarily to ribosome binding: if binding increases (x-axis), α also increases (colour map). (c) The pattern in α when monomers strongly interact (kD = 10) is similar, but with a (much) sharper transition from lower to higher values.

The results shown in figure 2 suggest that there is a fragile equilibrium in the fraction of co-translational versus post-translational (i.e. in the cytosol) dimerization, which, in turn, would impact on the nonlinear dynamics of the system. Therefore, different values of α will modify the performance of genetic circuits that build on nonlinear reactions to achieve optimal behaviour. In what follows, we analyse how α may be used to alter oscillations and bistability.

2.2. Case study: programmable nonlinearity in a genetic oscillator

A general requirement in order to obtain oscillations from a biological system is that its kinetic machinery must be ‘sufficiently nonlinear’ [44]. Here, we build a mathematical model for a theoretical three-component genetic oscillator, based on the ‘repressilator’ equations [45]. The model accounts for the new parameter that represents the fraction of dimerization that takes place during translation (α), and simulates how this parameter can, by itself, modify the nonlinearity of the system.

This genetic circuit is formed by a ring of repressors (proteins that negatively regulate a promoter), where each one regulates its successor (figure 3a). As a result, the concentration of all three proteins within the circuit oscillates in time. The system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that represents the oscillator is described as follows. Firstly, the ODE that calculates the concentration of monomeric repressors is

| 2.4 |

where i ∈ 1, 2, 3 is a specific repressor protein, Rmono is the amount of repressor monomer in the cytosol (i.e. those monomeric regulators that did not dimerize during translation), kon is the expression rate of monomers when the promoter P is not repressed (thus fully active), kdeg represents the degradation rate of monomers, kdim is the rate of dimerization in the cytosol and α is the fraction of monomers that become dimers during co-translation dimerization (which will dissolve as dimers in the cytosol). Therefore, equation (2.4) reads as follows: the concentration of monomers equals their production minus their degradation, and minus their consumption into dimerization.

Figure 3.

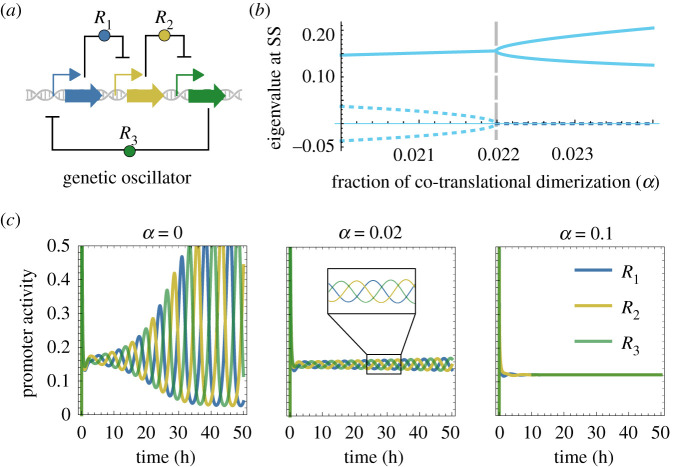

Impact of co-translational dimerization (α) on a genetic oscillator. (a) Diagram of a three-component genetic oscillator (as in [45])—each repressor protein (R) inhibits the expression of its successor. As a result, the concentration of each repressor oscillates in time. (b) Eigenvalue analysis, which shows a bifurcation point around α = 0.022. This suggests that the emergence of oscillations is highly dependent on the balance between co- and post-translational dimerization. Solid and dotted lines are the real and imaginary values of the eigenvalues in the Jacobian at equilibrium, respectively. SS, steady state. (c) Time-course simulations of the genetic oscillator at different values of α. As shown, reliable oscillations are lost for values indicated in (b).

Secondly, the ODE that calculates repressor dimers (i.e. the fully active protein) is given by

| 2.5 |

where Rdimer is the dimerized repressor (note that in this model all three repressors of the system are assumed to be dimers in its final form). Lastly, the next ODE calculates the fraction of promoter P that is active (i.e. it is not being repressed by any R)

| 2.6 |

where kun is the unbinding rate of any dimer from its cognate promoter P and 1/τs is the binding rate of the same two components. Note that promoter number i is repressed by a repressor number i − 1, where the previous element to i = 1 is i = 3, since the three genetic elements (1,2,3) are arranged in a ring.

Figure 3 shows how the parameter α alters the nonlinear patterns of the system, to the point that the circuit stops oscillating if the balance between co- and post-translational dimerization is beyond a bifurcation point (figure 3b). That is, higher values of α lead to a non-oscillating steady state (figure 3c). This bifurcation, beyond which the oscillatory behaviour vanishes, is around α = 0.022, which indicates that, even if the majority of dimers are formed in the cystosol, those that form during translation can drastically affect circuit behaviour. For the sake of comparison, the simulation where α = 0 is equivalent to a model that does not consider this effect.

The new parameter α introduces complexity to the mathematical model in that it limits the range of parameter values that generate oscillations—it could be argued that it is more difficult to get reliable oscillations with it than without it. However, it offers several pathways to modify nonlinearity in vivo, unlike traditional methods for nonlinear dynamics (e.g. Hill coefficients). Therefore, its predictive scope narrows the gap that goes from modelling results to in vivo experimentation.

2.3. Case study: programmabnle nonlinearity in a genetic toggle switch

A genetic toggle switch [36] is a device built from two mutually inhibitory repressors that is able to flip between stable states (figure 4), in which only one of the two proteins is at high expression while the other one is inhibited. The stability of the system, and also the number of stable states, depends intricately on nonlinear dynamics. Although there are examples of genetic switches where nonlinearity emerges from protein dilution [46,47], the most common way of achieving nonlinear dynamics (and bistability) comes from transcription cooperativity—in which protein dimerization plays a fundamental role.

Figure 4.

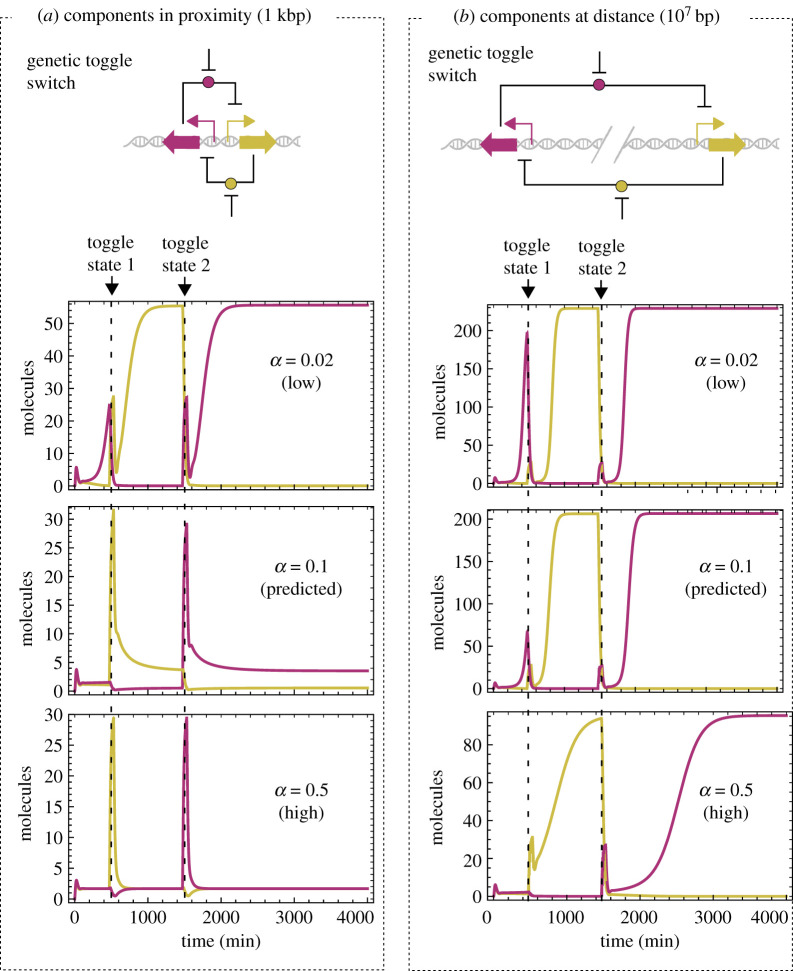

Impact of co-translational dimerization and intergenic distance on a genetic toggle switch. (a) The two circuit modules are located in proximity (i.e. sharing the same chromosomal position). In this scenario, only in the case of α being low is there enough nonlinearity to achieve bistability. (b) Genetic components are placed at a distance (i.e. different chromosomal location). The physical separation forces proteins to travel from their source gene to their target promoter—a nonlinear process which counteracts the effect of high α values. (a,b) The value of α = 0.1 (tagged as predicted) is our theoretical approximation; up to now, and to the best of our knowledge, this value has not been experimentally obtained.

Our model for the toggle switch is specified by equations (2.6), (4.1) and (4.2), but with two (instead of three) repressor proteins (which are also assumed to be dimers). Furthermore, we added complexity to the model by considering the intracellular spatial distribution of genes, based on our recent work on spatio-temporal design [35,48]. This feature helps to differentiate between local and global repressors; that is, repressors that are in the proximity of, or far from, their encoding gene. The core message was that the distance a protein must ‘travel’ from its source gene to its target promoter modifies regulation in a predictable fashion. Since the differentiation between local and global proteins intersects with the model we introduce here, where proteins dimerize during translation (i.e. local) or in the cytosol during free diffusion (i.e.global), we analysed the genetic switch considering both dynamics.

Figure 4 shows the results of simulating the switch with two different spatial set-ups, proximity (figure 4a) and distance (figure 4b), and three values for the fraction of co-translational dimerization (α) in each case. Interestingly, the two spatial configurations show different performances for the same level of α, which implies that both phenomena (intergenic separation and protein dimerization) are closely connected in shaping nonlinear dynamics.

When the genes of the switch are placed in proximity (figure 4a), only a low value of α generates sufficient nonlinearity for the system to show bistability. This is because the generation of dimers imposed by co-translational dimerization is fully linear—so the fewer the better. As soon as this value increases, more dimerization takes place during translation, leading to a system malfunction; although the switching still occurs to some extent (e.g. α = 0.5), output values are low, and the intrinsic stochasticity of biological systems would result in unstable states. However, moving genes far apart (figure 4b) restored the function of the system, even in the case of α = 0.5 (a value we predict to be higher than physically plausible). By increasing the separation between the genes, the dimers formed near the source are not immediately available to bind to the target promoter, since this is now at a long distance. As a result, such a linear process is now less relevant: co-translated dimers must ‘travel’ from the source to the target, resulting in a decreased promoter-binding rate, which, in turn, removes its involvement in total promoter-binding events. Unlike the proximity scenario, where performance was only achieved at low values for α, the distance set-up showed bistability at any value. This highlights the role played by intra-cellular distance for circuit design. An extra simulation where α = 0 (i.e. the co-translational dimerization effect is not considered) can be found in the electronic supplementary material.

Altogether, simulations suggest that the necessary conditions for the emergence of bistability could be rationally designed or fine-tuned, and mapped into biological specifications such as ribosome binding sites (RBSs) (which impact on α) or intergenic separation.

3. Conclusion

The design of increasingly complex biological circuits in living cells is a major challenge. The lack of robust predictive modelling—which accurately foresees the performance of a design before implementation—threatens to undermine the success of the field. Although model-based design [49] is a common practice, accurate predictions are difficult to obtain since the internal workings of the cell are still based on unclear dynamics. Here, we focus on modelling protein dimerization [33] within regulatory interactions, as a way to predict and rationally design nonlinearity.

For protein dimerization to take place, monomers must meet within the internal milieu of the cell. Although there are previous efforts that highlight the relevance of this issue [38,39], the mathematical formalization of the mechanistic details responsible for dimerization has received little attention. Our model explicitly simulates co- and post-translational dimerization, which occur during and after translation, respectively. While the former imposes a linear regime on the reaction, the latter boosts the emergence of nonlinear dynamics. By controlling the fraction of each dimerization type, the model suggests routes for fine-tuning nonlinearity in vivo to fit pre-defined functional requirements. Moreover, the model was coupled to a previous model on spatio-temporal design that accounts for the diffusion of molecules within the volume of the cell [48]. Simulations suggested that intergenic distance (i.e. the physical distance between two inter-regulated genes) plays a fundamental role in shaping dimerization dynamics. Specifically, the linear dynamics imposed by co-translational dimerization are less important if the two interacting genes are far apart; and that distance can be adjusted in vivo by assigning different chromosomal locations to circuit components. Since nonlinear dynamics are at the core of biological [30] and computing [32] systems, their rational design would enable the construction of biological circuits with enhanced information-processing capabilities. The model presented here paves the way towards that goal.

Simulation results suggest a number of strategies on how to implement control over nonlinearity in vivo. For instance, (i) protein length [50] (adding tags or extra AAs), (ii) choice of RBS [51], since stronger RBSs will result in closer ribosomes on the mRNA, or (iii) ribosome availability [52] (influencing binding rates)—let alone the modification of intergenic distance [35]. Future work along this line will focus on obtaining experimental measurements of the impact of co-translation based on the aforementioned implementation strategies. These will result in identifying the extent to which nonlinear dynamics can be adjusted on-demand. Furthermore, future theoretical work will aim at studying whether co-translational oligomerization could be modelled with a similar approach. Our model accounts for first-order interactions (i.e. monomers with monomers) but many functional transcription factors are, in fact, dimers of dimers. While the model, as is, can simulate the post-translational dimerization of co-translated dimers (thus representing regulators such as LacI, which is a tetramer), it cannot describe the formation of oligomers during translation. Although it is unlikely to play a major role in nonlinearity, this possibility will be targeted in future research.

As precision is increasingly required from synthetic constructs, we advocate for the rational design of nonlinearity—a fundamental feature of biological systems. The model introduced here demonstrated the in-principle feasibility of it, and provides baseline information for future in vivo implementation.

4. Methods

4.1. Modelling the distance between ribosomes

In the model presented here, the distance between two consecutive ribosomes (Δx) is determined by (i) the rate of translation and (ii) the difference in arrival time. This value is calculated as follows:

| 4.1 |

where xbp is the width of a base pair, ca 3 Å [53], and the factor of 3 comes from one AA being encoded by 3 bp.

This difference in arrival time (Δt) also leads to a difference in length (Δr) of partially translated proteins (or monomers). The calculation of the latter is captured by the next equation,

| 4.2 |

where xAA is the width of a contour length of an AA, also ca 3 Å [54].

The model assumes that this distance is constant until completing translation, which implies that the separation between ribosomes depends only on their binding times and not on sliding differences along the RNA.

4.2. Calculation of overlapping spheres

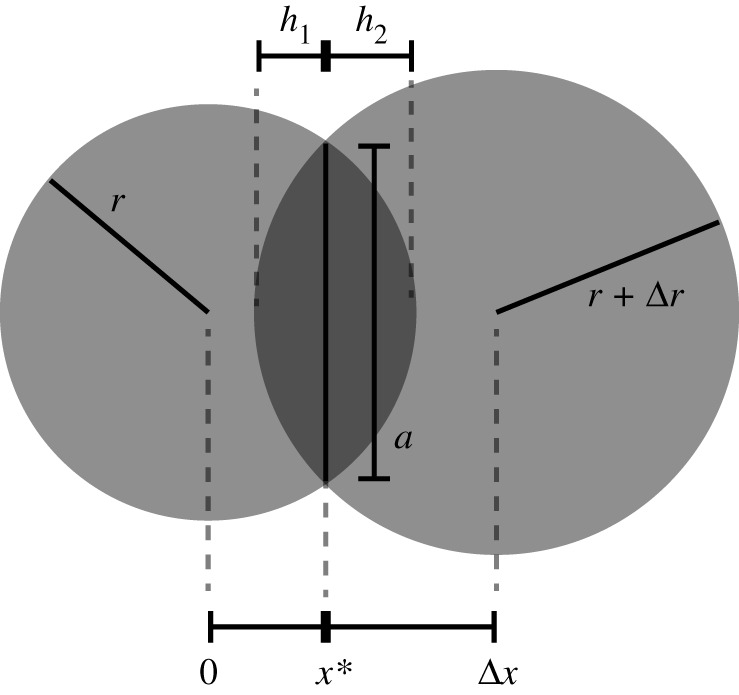

To calculate the overlap between the volumes of partially formed monomers we focus on a two-consecutive-ribosome scenario, which can be generalized to the ensemble of all ribosomes. In what follows, we show the derivation of equation (2.2) (i.e. overlapping fraction).

Here, we assume a system in which the two consecutive ribosomes have just initiated translation and are physically separated by a distance of Δx. The radii described by the partially formed monomers are r1 and r2, respectively. In this scenario, the spheres are then described by

| 4.3 |

and

| 4.4 |

Using these equations, the edges of the spheres meet at a circle in the yz plane at location x determined by

| 4.5 |

which can be solved for x*

| 4.6 |

The overlapping volume can be described as a combination of two spherical domes (figure 5) with the disc as described by equation (4.5) as the base. The volume of each dome is determined by

| 4.7 |

where a is the radius of the disc and h is the height of the dome. The value of h differs between the two domes and is r1 − x* and r2 − (Δx) + x* for the ribosome at the origin and the ribosome shifted by Δx, respectively. Assuming that the translation rate is constant, the length of the transcripts of consecutive ribosomes is r1 = r and r2 = r + Δr, with Δr as determined by equation (4.2). The ribosome arrival time also determines the distance between the ribosomes (Δx) via equation (4.1).

Figure 5.

Calculation of the spherical overlap between partially formed monomers. At the centre of each sphere, there is a ribosome bound to the RNA and that is actively translating. The radii (r and r + Δx) define the length of a monomer. Note that the dark grey overlapping section is composed of two spherical domes; for visualization purposes, here we show the two-dimensional analogous circular segments. The value of h is the height of the dome and a is the radius of its disc.

Supplementary Material

Data accessibility

All time simulations, bifurcation analyses, derivations and data visualization were done in Wolfram Mathematica 12.0. Notebooks are available at https://github.com/rstoof/TranslationMediatedDimerisation.

Authors' contributions

R.S. and Á.G.-M. designed the research. R.S. developed the model and performed simulations. Both authors interpreted the results and Á.G.-M. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the SynBio3D project of the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/R019002/1) and the European CSA on biological standardization BIOROBOOST (EU grant no. 820699). Á.G.-M. was also supported by grants from Comunidad de Madrid (Atraccion de Talento Program, grant no. 2019-T1/BIO-14053) and the Severo Ochoa Program for Centres of Excellence in R&D from the Agencia Estatal de Investigacion of Spain, grant no. SEV-2016-0672 (2017–2021).

References

- 1.De Lorenzo V, Danchin A. 2008. Synthetic biology: discovering new worlds and new words: the new and not so new aspects of this emerging research field. EMBO Rep. 9, 822–827. ( 10.1038/embor.2008.159) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amos M, Goñi-Moreno A. 2018. Cellular computing and synthetic biology. In Computational matter (eds S Stepney, S Rasmussen, M Amos), pp. 93–110. New York, NY: Springer.

- 3.Andrianantoandro E, Basu S, Karig DK, Weiss R. 2006. Synthetic biology: new engineering rules for an emerging discipline. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2, 2006-0028 ( 10.1038/msb4100073) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerosa L, Kochanowski K, Heinemann M, Sauer U. 2013. Dissecting specific and global transcriptional regulation of bacterial gene expression. Mol. Syst. Biol. 9, 658 ( 10.1038/msb.2013.14) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiße AY, Oyarzún DA, Danos V, Swain PS. 2015. Mechanistic links between cellular trade-offs, gene expression, and growth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E1038–E1047. ( 10.1073/pnas.1416533112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes RA, Ellington AD. 2017. Synthetic DNA synthesis and assembly: putting the synthetic in synthetic biology. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 9, a023812 ( 10.1101/cshperspect.a023812) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nielsen AAK, Der BS, Shin J, Vaidyanathan P, Paralanov V, Strychalski EA, Ross D, Densmore D, Voigt CA. 2016. Genetic circuit design automation. Science 352, aac7341 ( 10.1126/science.aac7341) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lou C. et al. 2010. Synthesizing a novel genetic sequential logic circuit: a push-on push-off switch. Mol. Syst. Biol. 6, 350 ( 10.1038/msb.2010.2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calles B, Goñi-Moreno Á, de Lorenzo V. 2019. Digitalizing heterologous gene expression in Gram-negative bacteria with a portable on/off module. Mol. Syst. Biol. 15, e8777 ( 10.15252/msb.20188777) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blount BA, Weenink T, Ellis T. 2012. Construction of synthetic regulatory networks in yeast. FEBS Lett. 586, 2112–2121. ( 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.01.053) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ausländer S, Ausländer D, Müller M, Wieland M, Fussenegger M. 2012. Programmable single-cell mammalian biocomputers. Nature 487, 123–127. ( 10.1038/nature11149) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang B, Kitney RI, Joly N, Buck M. 2011. Engineering modular and orthogonal genetic logic gates for robust digital-like synthetic biology. Nat. Commun. 2, 1–9. ( 10.1038/ncomms1516) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goñi-Moreno A, Amos M. 2012. A reconfigurable NAND/NOR genetic logic gate. BMC Syst. Biol. 6, 126 ( 10.1186/1752-0509-6-126) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moon TS, Clarke EJ, Groban ES, Tamsir A, Clark RM, Eames M, Kortemme T, Voigt CA. 2011. Construction of a genetic multiplexer to toggle between chemosensory pathways in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 406, 215–227. ( 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.12.019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong A, Wang H, Poh CL, Kitney RI. 2015. Layering genetic circuits to build a single cell, bacterial half adder. BMC Biol. 13, 40 ( 10.1186/s12915-015-0146-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedland AE, Lu TK, Wang X, Shi D, Church G, Collins JJ. 2009. Synthetic gene networks that count. Science 324, 1199–1202. ( 10.1126/science.1172005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonnet J, Yin P, Ortiz ME, Subsoontorn P, Endy D. 2013. Amplifying genetic logic gates. Science 340, 599–603. ( 10.1126/science.1232758) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daniel R, Rubens JR, Sarpeshkar R, Lu TK. 2013. Synthetic analog computation in living cells. Nature 497, 619–623. ( 10.1038/nature12148) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goñi-Moreno A, Amos M. 2012. Continuous computation in engineered gene circuits. Biosystems 109, 52–56. ( 10.1016/j.biosystems.2012.02.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goñi-Moreno A, Redondo-Nieto M, Arroyo F, Castellanos J. 2011. Biocircuit design through engineering bacterial logic gates. Nat. Comput. 10, 119–127. ( 10.1007/s11047-010-9184-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regot S. et al. 2011. Distributed biological computation with multicellular engineered networks. Nature 469, 207–211. ( 10.1038/nature09679) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goñi-Moreno A, Amos M. 2015. Discus: a simulation platform for conjugation computing. In Proc. 14th Int. Conf. On Unconventional Computation and Natural Computation, Auckland, New Zealand, 30 August--3 September 2015, pp. 181–191. New York, NY: Springer.

- 23.Chubukov V, Mukhopadhyay A, Petzold CJ, Keasling JD, Martín HG. 2016. Synthetic and systems biology for microbial production of commodity chemicals. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 2, 1–11. ( 10.1038/npjsba.2016.9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Lorenzo V. et al. 2018. The power of synthetic biology for bioproduction, remediation and pollution control. EMBO Rep. 19, e45658 ( 10.15252/embr.201745658) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grozinger L. et al. 2019. Pathways to cellular supremacy in biocomputing. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–11. ( 10.1038/s41467-019-13232-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandran D, Copeland WB, Sleight SC, Sauro HM. 2008. Mathematical modeling and synthetic biology. Drug Discov. Today: Disease Models 5, 299–309. ( 10.1016/j.ddmod.2009.07.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goñi-Moreno A, Carcajona M, Kim J, Martínez-García E, Amos M, de Lorenzo V. 2016. An implementation-focused bio/algorithmic workflow for synthetic biology. ACS Synth. Biol. 5, 1127–1135. ( 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao C, Blanchard AE, Lu T. 2017. An integrative circuit–host modelling framework for predicting synthetic gene network behaviours. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 1658–1666. ( 10.1038/s41564-017-0022-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ge H, Qian H. 2011. Non-equilibrium phase transition in mesoscopic biochemical systems: from stochastic to nonlinear dynamics and beyond. J. R. Soc. Interface 8, 107–116. ( 10.1098/rsif.2010.0202) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma’ayan A. 2017. Complex systems biology. J. R. Soc. Interface 14, 20170391 ( 10.1098/rsif.2017.0391) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaplan D, Glass L. 2012. Understanding nonlinear dynamics. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kia B, Lindner JF, Ditto WL. 2017. Nonlinear dynamics as an engine of computation. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 375, 20160222 ( 10.1098/rsta.2016.0222) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bouhaddou M, Birtwistle MR. 2014. Dimerization-based control of cooperativity. Mol. Biosyst. 10, 1824–1832. ( 10.1039/C4MB00022F) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janson NB. 2012. Non-linear dynamics of biological systems. Contemp. Phys. 53, 137–168. ( 10.1080/00107514.2011.644441) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goñi-Moreno A, Benedetti I, Kim J, de Lorenzo V. 2017. Deconvolution of gene expression noise into spatial dynamics of transcription factor–promoter interplay. ACS Synth. Biol. 6, 1359–1369. ( 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00397) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gardner TS, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. 2000. Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli. Nature 403, 339–342. ( 10.1038/35002131) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elowitz MB, Leibler S. 2000. A synthetic oscillatory network of transcriptional regulators. Nature 403, 335–338. ( 10.1038/35002125) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee KA. 1992. Dimeric transcription factor families: it takes two to tango but who decides on partners and the venue? J. Cell Sci. 103, 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gilmore R, Coffey MC, Leone G, McLure K, Lee PW. 1996. Co-translational trimerization of the reovirus cell attachment protein. EMBO J. 15, 2651–2658. ( 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00625.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitarai N, Pedersen S. 2013. Control of ribosome traffic by position-dependent choice of synonymous codons. Phys. Biol. 10, 056011 ( 10.1088/1478-3975/10/5/056011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vogel U, Jensen KF. 1994. The RNA chain elongation rate in Escherichia coli depends on the growth rate. J. Bacteriol. 176, 2807–2813. ( 10.1128/JB.176.10.2807-2813.1994) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Young R, Bremer H. 1976. Polypeptide chain elongation rate in Escherichia coli B/r as a function of growth rate. Biochem. J. 160, 185–194. ( 10.1042/bj1600185) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gorochowski TE, Chelysheva I, Eriksen M, Nair P, Pedersen S, Ignatova Z. 2019. Absolute quantification of translational regulation and burden using combined sequencing approaches. Mol. Syst. Biol. 15, 1–15. ( 10.15252/msb.20188719) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Novák B, Tyson JJ. 2008. Design principles of biochemical oscillators. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 981–991. ( 10.1038/nrm2530) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcia-Ojalvo J, Elowitz MB, Strogatz SH. 2004. Modeling a synthetic multicellular clock: repressilators coupled by quorum sensing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 10955–10960. ( 10.1073/pnas.0307095101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang D, Holtz WJ, Maharbiz MM. 2012. A genetic bistable switch utilizing nonlinear protein degradation. J. Biol. Eng. 6, 9 ( 10.1186/1754-1611-6-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan C, Marguet P, You L. 2009. Emergent bistability by a growth-modulating positive feedback circuit. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 842–848. ( 10.1038/nchembio.218) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stoof R, Wood A, Goñi-Moreno Á. 2019. A model for the spatiotemporal design of gene regulatory circuits. ACS Synth. Biol. 8, 2007–2016. ( 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watanabe L, Nguyen T, Zhang M, Zundel Z, Zhang Z, Madsen C, Roehner N, Myers C. 2018. ibiosim 3: a tool for model-based genetic circuit design. ACS Synth. Biol. 8, 1560–1563. ( 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00078) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Currin A, Swainston N, Day PJ, Kell DB. 2015. Synthetic biology for the directed evolution of protein biocatalysts: navigating sequence space intelligently. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 1172–1239. ( 10.1039/C4CS00351A) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reeve B, Hargest T, Gilbert C, Ellis T. 2014. Predicting translation initiation rates for designing synthetic biology. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2, 1 ( 10.3389/fbioe.2014.00001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Darlington APS, Kim J, Jiménez JI, Bates DG. 2018. Dynamic allocation of orthogonal ribosomes facilitates uncoupling of co-expressed genes. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–12. ( 10.1038/s41467-017-02088-w) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arnott S, Chandrasekaran R, Birdsall DL, Leslie AGW, Ratliff RL. 1980. Left-handed DNA helices. Nature 283, 743–745. ( 10.1038/283743a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ainavarapu SRK. et al. 2007. Contour length and refolding rate of a small protein controlled by engineered disulfide bonds. Biophys. J. 92, 225–233. ( 10.1529/biophysj.106.091561) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All time simulations, bifurcation analyses, derivations and data visualization were done in Wolfram Mathematica 12.0. Notebooks are available at https://github.com/rstoof/TranslationMediatedDimerisation.