Abstract

The present study was conducted to assess the behavioral preventive measures and the use of medicines and herbal foods/products among the public in response to Covid-19. A cross-sectional survey comprised of 1222 participants was conducted from 27 June to 20 July 2020. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to identify the differences in behavioral preventive practices across different demographic categories. To identify the factors associated with the use of preventive medicines and herbal foods/products, multivariable logistic regression was performed. Most participants adopted the recommended preventive practices such as washing hands more frequently (87.5%), staying home more often (85.5%), avoiding crowds (86%), and wearing masks (91.6%). About half of the smokers reported a decreased rate of smoking during the pandemic. Also, 14.8% took medicines, 57.6% took herbal foods/products, and 11.2% took both medicines and herbal foods/products as preventive measure against Covid-19. Arsenicum album, vitamin supplements, and zinc supplements were the most commonly used preventive medicines. Gender, age, and fear of Covid-19 were significantly associated with the use of both preventive medicines and herbal foods/products. For the management of Covid-19 related symptoms, paracetamol, antihistamines, antibiotics, and mineral (zinc and calcium) supplements were used most often. Most participants sought information from non-medical sources while using medicines and herbal products. Moreover, potentially inappropriate and unnecessary use of certain drugs was identified.

Introduction

Covid-19 is an infectious disease caused by a novel coronavirus named Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). First identified in December 2019 in China, Covid-19 was declared a pandemic in March 2020 by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. Bangladesh is one of the most affected countries by the Covid-19 pandemic, with 232,194 confirmed cases as of 30 July 2020 [2]. Bangladesh is a country with limited resources and a poor healthcare management system. The country is facing a multitude of challenges to fight this pandemic including insufficient testing, lack of public awareness, and inadequate facilities to treat Covid-19 patients [3, 4]. For instance, the capability of the government to treat Covid-19 patients is extremely limited, with only 733 intensive care unit (ICU) beds and fewer than 1,800 ventilators for critical support for a population of well over 16 million [5]. There have been reports of Covid-19 patients being denied treatments from public and private hospitals as these hospitals do not have the required facilities to treat Covid patients [5, 6].

Given the situation, hospital-based interventions cannot be a primary means of dealing with the pandemic in resource-limited countries like Bangladesh. Instead, efforts must be made to prevent the spread of the virus as much as possible. Recommended preventive measures include wearing masks, social distancing, washing hands regularly, and staying home as much as possible [7]. In absence of vaccines or antiviral therapy against Covid-19, experts have recommended the intake of vitamins, minerals, and herbal medicines in order to bolster the immune system in a bid to lower the risk and severity of infection [8–10].

The panic and fear surrounding the pandemic combined with misinformation have prompted the people to buy and hoard medicines [11, 12]. During the Covid-19 lockdown, access to health providers has been restricted significantly which is likely to make people more prone to self-medication and more dependent on less reliable sources such as social and digital media for medicine-related information. Therefore, it is very likely that there have been inappropriate and unnecessary uses of medicines by the Bangladeshi people in relation to the prevention and cure of Covid-19 symptoms.

The primary focus of this study was to explore what medicines and herbal products/foods are being used by the public as preventive measure against Covid-19, as well as to manage symptoms associated with Covid-19. To our best knowledge, this is the first study in any country to assess the use of medications among the public in response to Covid-19. We also assessed the behavioral preventive measures adopted by the public during the pandemic.

Methods

Study design and sampling

We performed a cross-sectional survey from 27 June to 20 July 2020 using a self-administered questionnaire. Data collection was conducted both in-person and online using purposive sampling to include participants of all ages and diverse educational and socioeconomic backgrounds. The online survey was conducted using google forms and participants were recruited via social media platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp. Since most internet users are young and live in urban areas, we also conducted in-person surveys to recruit participants from rural areas who might not have access to the internet. The in-person survey was done in different parts of the country including Dhaka, Manikganj, Cumilla, Tangail, and Nilphamari. Adults aged 18 years and above were eligible to participate in the survey. Regarding sample size, the goal was to include as many participants as possible. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Antimicrobial Resistance Action Center (ARAC), Animal Health Research Division, Bangladesh Livestock Research Institute (BLRI), Bangladesh (Approval no: ARAC:15/06/2020:03). Participants were made aware of the purpose of the study and were asked to provide consent before participating in the survey. During the in-person survey, written consent was obtained from the participants. And when participating online, participants were first asked if they were willing to participate in the survey and they had to click the “Yes” button before continuing to the next sections.

The questionnaire

The questionnaire (S1 File) consisted of three parts. The first part was for sociodemographic information such as age, gender, education, marital status, place of residence (rural or urban), presence of chronic disease, as well as participants’ fear of Covid-19. The second part contained four questions related to behavioral preventive measures adopted by the people such as washing hands, staying home, avoiding crowds, and wearing masks. Participants were also asked if there had been any changes in their smoking habits during the pandemic.

The third section asked questions about the participants’ use of medicines and herbal products/foods as preventive and curative measures against Covid-19. First, participants were asked whether they had experienced any Covid-19 related symptom or not. Those who did not experience any symptoms were asked if they had taken any medicine or herbal product as preventive measure to lower the risk of infection. As for those who experienced one or more symptoms associated with Covid-19, they were asked what medicines they had used to manage those symptoms, as well as if they had taken any medicine or herbal products/foods as preventive measure before the occurrence of symptoms. It should be mentioned that we relied on participants’ self-reports of symptoms instead of Covid-19 test results since only a very small percentage of the population is being tested, with only 6,985 people per million population [2]. To help participants with the identification of Covid-19 symptoms, a list of the common symptoms of Covid-19 (fever, dry cough, tiredness, sore throat, difficulty breathing) based on the WHO guidelines was provided with the questionnaire. Participants were also asked about the source of information/advice that influenced their choice of medications and herbal products. The questionnaire was translated to Bangla and pretested in a pilot survey of 10 people, and amendments were made where necessary.

Statistical analysis

The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, the behavioral preventive practices, the use of medicines and herbs, and the sources of medication-related information were analyzed descriptively. The number of behavioral preventive practices (washing hands, staying home, avoiding crowds, and wearing masks) adopted by each participant was summed up and scored from 0 to 4 (0 = when none of the preventive measures was adopted, 4 = when all of the preventive measures were adopted). To identify the differences in behavioral preventive practices across different demographic categories, the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test was performed. The Kruskal-Wallis test was preferred over ANOVA because the data was not normally distributed. To assess the factors associated with the use of preventive medicines and herbal foods/products, multivariable binary logistic regression was performed, calculating the adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Data analysis was performed in IBM SPSS version 25.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

A total of 1222 people participated in the survey. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 82 years, and the mean age was 30.77 (SD: 12.1 years). Among the respondents, 61.4% were male, 61.9% lived in urban areas, and 52.1% had received university (undergraduate and graduate) education. 13.6% were suffering from one or more chronic diseases. The fear of Covid-19 varied, with 15.6% reporting being not afraid at all while 28% said they were very afraid. Detailed characteristics of the participants are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

| Characteristic | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 750 (61) |

| Female | 466 (38) |

| Age | |

| 18–29 | 767 (63) |

| 30–44 | 277 (23) |

| 45–59 | 112 (9) |

| 60 and greater | 60 (5) |

| Residence | |

| Rural | 461 (38) |

| Urban | 756 (62) |

| Education | |

| Secondary or lower | 334 (27) |

| Higher secondary | 245 (20) |

| Undergraduate degree | 410 (34) |

| Graduate degree | 226 (19) |

| Marital status | |

| Unmarried | 662 (54) |

| Married | 559 (46) |

| Presence of chronic disease | |

| No | 1052 (86) |

| Yes | 166 (14) |

| Fear of Covid-19 | |

| Not afraid | 191 (16) |

| Somewhat/ Moderately afraid | 683 (56) |

| Very afraid | 342 (28) |

Behavioral preventive measures

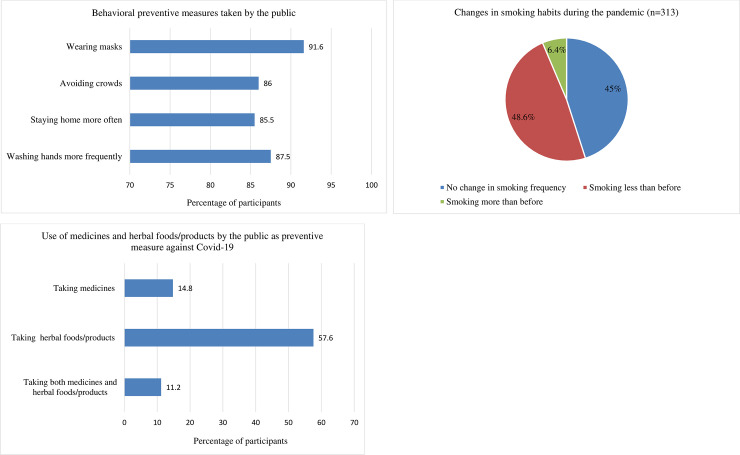

Most of the participants reported following the behavioral preventive guidelines such as frequent washing of hands (87.5%), staying home more often (85.5%), avoiding crowds (86%), and wearing masks (91.6%) (Fig 1A). Compliance with these practices was significantly higher among participants with higher education, participants who were females and of younger ages, and participants with a higher level of Covid-19 fear (Table 2). 25.6% (313) of the participants identified themselves as smokers, and 48.6% (152) of them said they were smoking less frequently than before the pandemic (Fig 1B).

Fig 1.

Behavioral preventive measures (A, B) and the use of preventive medicines and herbal products (C) among the public in response to Covid-19.

Table 2. Groupwise means and the results of the Kruskal-Wallis test on the differences in the number of behavioral preventive practices across different demographic categories.

| Variables | Number of preventive practices (Mean) | Standard Deviation | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 3.35 | 1.09 | |

| Female | 3.76 | 0.58 | |

| Age | 0.049 | ||

| 18–29 | 3.54 | 0.93 | |

| 30–44 | 3.48 | 0.95 | |

| 45–59 | 3.37 | 0.1 | |

| 60 and greater | 3.37 | 1.06 | |

| Residence | <0.001 | ||

| Rural | 3.25 | 1.17 | |

| Urban | 3.66 | 0.74 | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||

| Secondary or lower | 3.00 | 1.25 | |

| Higher secondary | 3.62 | 0.85 | |

| Undergraduate | 3.71 | 0.71 | |

| Graduate | 3.76 | 0.56 | |

| Marital status | 0.005 | ||

| Unmarried | 3.57 | 0.89 | |

| Married | 3.43 | 1.0 | |

| Presence of chronic disease | 0.81 | ||

| No | 3.50 | 0.96 | |

| Yes | 3.52 | 0.87 | |

| Fear of Covid-19 | <0.001 | ||

| Not afraid | 2.76 | 1.42 | |

| Somewhat/ Moderately afraid | 3.57 | 0.81 | |

| Very afraid | 3.80 | 0.6 |

Medication use

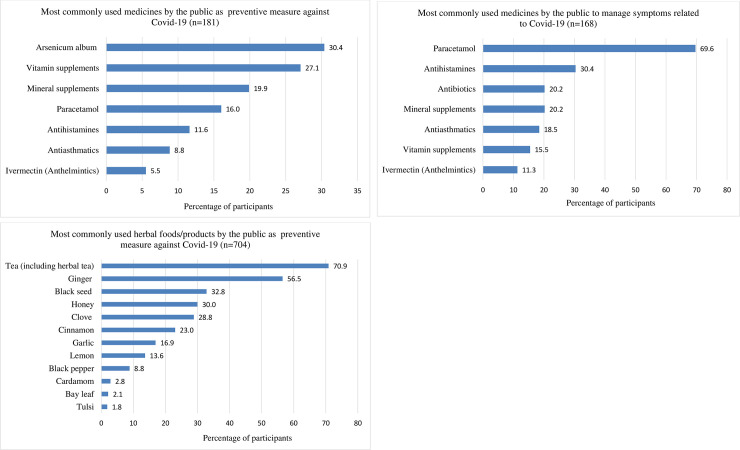

About 15% (181) of the participants took conventional (allopathic) and homeopathic medicines prophylactically in order to lower the risk of being infected with Covid-19 (Fig 1C). The most commonly used medicine was arsenicum album, a homeopathic formulation of arsenic trioxide. Other commonly used medicines were vitamin supplements (vitamin C, D, B, and multivitamins), mineral supplements (mostly zinc), paracetamol, antihistamines (fexofenadine, desloratadine, and chlorpheniramine), antiasthmatics (mostly montelukast), and ivermectin (Fig 2A). Results of regression analysis show that males were more likely to take preventive medicines compared to females (OR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.04–2.15). Moreover, People aged 60 and above were most likely to take preventive medicines, and the odds of taking medicines for those who were very afraid of the pandemic was 2.48 times (95% CI: 1.36–4.53) than that of participants who were not afraid at all (Table 3).

Fig 2.

Use of medicine for prevention (A) and management (B) of Covid-19 symptoms and the use of herbal foods/products for prevention (C) of Covid-19 (the cumulative percentage may be greater than 100 since many participants took more than one drug or herb).

Table 3. Results of multivariable logistic regression of the factors associated with the use of medicines and herbal food/products among the public as a preventive measure against Covid-19.

| Variables | Use of medicines as a preventive measure against Covid-19 | Use of herbal foods/ products as a preventive measure against Covid-19 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds ratios | 95% Confidence interval | P- value | Adjusted Odds ratios | 95% Confidence interval | P- value | |

| Gender | 0.03 | 0.016 | ||||

| Female | ref | ref | ||||

| Male | 1.49 | 1.04–2.15 | 0.73 | 0.57–0.94 | ||

| Age | 0.004 | 0.049 | ||||

| 18–29 | ref | ref | ||||

| 30–44 | 2.0 | 1.22–3.27 | 0.62 | 0.43–0.90 | ||

| 45–59 | 1.02 | 0.49–2.15 | 0.57 | 0.34–0.94 | ||

| 60 and greater | 2.93 | 1.37–6.30 | 0.76 | 0.4–1.44 | ||

| Residence | 0.117 | 0.329 | ||||

| Rural | ref | ref | ||||

| Urban | 1.36 | 0.93–2.0 | 0.87 | 0.66–1.15 | ||

| Education | 0.111 | 0.007 | ||||

| Secondary or lower | ref | ref | ||||

| Higher secondary | 1.43 | 0.84–2.45 | 0.91 | 0.62–1.32 | ||

| Undergraduate | 1.89 | 1.13–3.16 | 0.82 | 0.57–1.19 | ||

| Graduate | 1.38 | 0.79–2.41 | 1.56 | 1.03–2.34 | ||

| Marital status | 0.238 | 0.034 | ||||

| Unmarried | ref | ref | ||||

| Married | 1.32 | 0.83–2.11 | 1.44 | 1.03–2.02 | ||

| Presence of chronic disease | 0.776 | 0.682 | ||||

| No | ref | ref | ||||

| Yes | 1.07 | 0.66–1.73 | 1.08 | 0.75–1.56 | ||

| Fear of Covid-19 | 0.012 | <0.001 | ||||

| Not afraid | ref | ref | ||||

| Somewhat/ Moderately afraid | 1.89 | 1.07–3.35 | 2.58 | 1.84–3.63 | ||

| Very afraid | 2.48 | 1.36–4.53 | 2.03 | 1.39–2.97 | ||

ref, reference.

Around 20% (239) of the participants experienced one or more symptoms related to Covid-19 infections, and 70% (168) of them took medications to manage the symptoms. Paracetamol was the most commonly used drug, followed by antihistamines (mostly fexofenadine, desloratadine, cetirizine, and chlorpheniramine), antibiotics (mostly azithromycin, doxycycline, and amoxicillin), mineral supplements (zinc and calcium), antiasthmatics (montelukast and salbutamol), etc. (Fig 2B).

Use of herbal foods/products

A large number of participants (57.6%) reported having taken herbal foods/products to lower the risk of Covid-19 infection (Fig 1C). About 71% of them took tea (normal and herbal), while other herbal foods such as ginger, black seed, honey, and clove were used by 56.5%, 32.8%, 30%, and 28.8% respectively (Fig 2C). These herbs were taken alone or in combination with tea or hot water. Factors significantly associated with taking herbal foods/products were being female, young (18–29 years), married, and afraid of the pandemic. Also, participants with a graduate degree were more likely to take preventive herbal foods/products than those with a secondary degree or lower (OR: 1.56, 95% CI: 1.03–2.34) (Table 3).

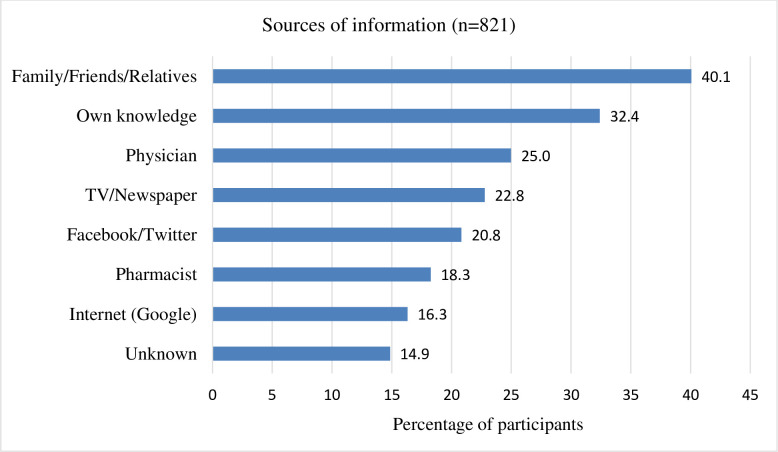

Source of information related to the use of medicines and herbal foods/products

When asked about the source of information related to their use of medicines or herbal foods/products, most participants said they had relied on the advice of family, friends, or relatives (40.1%). Different forms of media (print, digital, and social) were also major sources of information. Only 25% of the participants sought advice from physicians while 18% from pharmacists (Fig 3).

Fig 3. Sources of information related to the use of medicines and herbal foods/products by the public (the cumulative percentage is greater than 100 since many participants relied on more than one source of information).

Discussion

The present study was conducted at a time when the Covid-19 pandemic had reached its peak in Bangladesh [2], and we observed high rates of adoption of behavioral preventive measures (washing hands, staying home, avoiding crowds, and wearing masks), which was quite similar to the observations made in several earlier studies conducted in Bangladesh [13–15]. There was a decrease in cigarette smoking among half of the smokers. Studies have shown that smokers generally have a high risk of respiratory tract infections [16], and smoking can also be a risk factor for Covid-19 progression [17]. However, some participants reported an increase in smoking which can probably be attributed to the heightened stress, fear, and boredom associated with the pandemic and the lockdown.

A significant percentage of the participants had taken prophylactic medications, some of which were potentially unnecessary and inappropriate. For instance, the most used prophylactic medicine was the homeopathic medicine arsenicum album. Arsenicum album has been recommended as a prophylactic drug against Covid-19 by Vellingiri et al. [18], but there is no clinical evidence supporting its effectiveness against Covid-19 [19]. While there are claims that arsenicum album provides temporary relief against flu-symptoms, such claims are not proven and this drug is not currently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration [20]. Furthermore, homeopathy in general faces lots of criticism for being implausible, unscientific, and unreliable [21, 22]. Although it is hard to tell why so many people used this drug, one of the reasons may be the fact that the Ministry of Ayurveda, Yoga & Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy (AYUSH) of the neighboring country India recommended arsenicum album for prophylactic use against Covid-19 [19]. The media may also play a role in the popularity of arsenicum album. Many participants used paracetamols prophylactically although it should only be used to manage symptoms associated with Covid-19. Another notable case was the prophylactic use of ivermectin. Out of the ten participants who used ivermectin, only two sought advice from physicians. Similar cases of ivermectin self-medication have been reported in Brazil [23]. Prophylactic use of ivermectin for Covid-19 is not only unproven, but it can also be quite risky, especially when self-medicated [23].

Since there is no effective treatment of Covid-19 at this time, the intake of vitamins, minerals, and herbs can serve to boost the immune system which can subsequently lower risks of infection and disease progression [8–10]. In this study, many participants reported having taken vitamin D, C, B, and zinc supplements. The use of herbal foods/products was also very high, probably because these are readily available in most households in Bangladesh and are known for their medicinal values. Green tea and black tea polyphenols have been reported to show antiviral activities and may have applications in Covid-19 prophylaxis and treatment [24]. Other herbal products such as ginger, garlic, honey, and black seed have also been mentioned for their antiviral actions and potential action against Covid-19 [10, 25, 26]. However, it should be mentioned that some of the reported cases of the use of herbal foods/products in this study could be habitual and participants might have taken them without being aware of their association with Covid-19 prevention (for example tea).

When investigating the drugs used for the management of symptoms associated with Covid-19, our goal was to get an overview of the commonly used medicines in the community; assessment of hospital-based treatments or management of critical patients was beyond the scope of this study. Most people infected with Covid-19 experience only mild symptoms and intake of antipyretics (paracetamol) may be sufficient for that, according to WHO [27]. The national guidelines on clinical management of Covid-19 recommend paracetamol and fexofenadine for the management of mild symptoms as well as suggest the intake of zinc and vitamin C [28]. Similar to the guidelines, in this study, paracetamol, fexofenadine, and zinc supplements have been found to be the most commonly used medicines for symptom management.

In the present study, fear of Covid-19 has been the most important factor associated with the adoption of preventive measures among the public; those who reported being afraid of Covid-19 adopted a greater number of behavioral preventive practices and were more likely to take preventive medicines and herbs. No other study has yet investigated the association between Covid-19 fear and medication use among the public, but in a study conducted in Turkey, fear of the pandemic was associated with a higher level of engagement in preventive practices [29]. Another study among the Thai healthcare workers found that those who reported fear and anxiety were more likely to adopt preventive practices such as washing hands and wearing masks and personal protective equipment [30].

While the media (television, newspaper, Facebook, Twitter) have been playing a significant role in raising awareness about the pandemic, they have also contributed to the spread of misinformation surrounding Covid-19 [31, 32]. In this study, we have found a high reliance of the participants on the media for medication-related advice related to Covid-19. Therefore, it is important that the spread of misinformation through digital, print, and social media is contained as much as possible.

Limitations

The study has some limitations. First, the data collection was based on purposive sampling and so the findings of this study may not be generalized to the whole population. Second, we relied on self-reported data and so there is a possibility of social desirability bias where participants may prefer to give responses that are more appropriate or expected from them (like wearing mask or social distancing) instead of the responses that reflect their true behaviors.

Conclusions

In summary, we have observed a high adoption of behavioral preventive measures by the public. Also, a considerable number of participants have taken preventive medicines and herbal foods/products. Fear of Covid-19 has been identified as one of the most important factors associated with the adoption of behavioral preventive measures as well as the use of preventive medicines and herbal foods/products. For information pertaining to the use of medicines and herbs, most participants have relied on non-medical sources. Moreover, potential misuse and unnecessary use of certain drugs have been identified.

Supporting information

(PDF)

(SAV)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank FNU Hasan Al Monem for proofreading and copyediting our manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.WHO. Timeline: WHO's COVID-19 response 2020 [cited 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline/#event-73.

- 2.Worldometer. Worldometer; [cited 2020 30 July]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

- 3.Anwar S, Nasrullah M, Hosen MJ. COVID-19 and Bangladesh: Challenges and How to Address Them. Front Public Health. 2020;8:154–. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00154 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banik R, Rahman M, Sikder T, Gozal D. COVID- 19 in Bangladesh: public awareness and insufficient health facilities remain key challenges. Public Health. 2020;183:50–1. Epub 05/07. 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.04.037 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bangladesh Should Listen to its Health Workers. Human Rights Watch. June 21, 2020.

- 6.Covid-19: Hospitals continue to deny treatment. Dhaka Tribune. June 14th, 2020.

- 7.WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public [2 July 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public.

- 8.Jayawardena R, Sooriyaarachchi P, Chourdakis M, Jeewandara C, Ranasinghe P. Enhancing immunity in viral infections, with special emphasis on COVID-19: A review. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):367–82. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.015 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilashi M, Samad S, Yusuf SYM, Akbari E. Can complementary and alternative medicines be beneficial in the treatment of COVID-19 through improving immune system function? J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(6):893–6. Epub 05/20. 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.05.009 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panyod S, Ho C-T, Sheen L-Y. Dietary therapy and herbal medicine for COVID-19 prevention: A review and perspective. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine. 2020;10(4):420–7. 10.1016/j.jtcme.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhaka Tribune. Panic-buying creates shortage of ‘Covid-19 drugs’ in the market 21 June 2020. Available from: https://www.dhakatribune.com/health/coronavirus/2020/06/21/panic-buying-creates-shortage-of-covid-19-drugs-in-the-market.

- 12.The Daily NewNation. Panic hoarding pushes up medicine prices 16 June 2020. Available from: http://thedailynewnation.com/news/255379/panic-hoarding-pushes-up-medicine-prices.

- 13.Ferdous MZ, Islam MS, Sikder MT, Mosaddek ASM, Zegarra-Valdivia JA, Gozal D. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding COVID-19 outbreak in Bangladesh: An online-based cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(10):e0239254 10.1371/journal.pone.0239254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haque T, Hossain KM, Bhuiyan MMR, Ananna SA, Chowdhury SH, Islam MR, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP) towards COVID-19 and assessment of risks of infection by SARS-CoV-2 among the Bangladeshi population: An online cross sectional survey. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul A, Sikdar D, Hossain MM, Amin MR, Deeba F, Mahanta J, et al. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Towards Novel Corona Virus among Bangladeshi People: Implications for mitigation measures. medRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Zyl-Smit RN, Richards G, Leone FT. Tobacco smoking and COVID-19 infection. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(7):664–5. Epub 05/25. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30239-3 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patanavanich R, Glantz SA. Smoking is Associated with COVID-19 Progression: A Meta-Analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020:ntaa082 10.1093/ntr/ntaa082 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vellingiri B, Jayaramayya K, Iyer M, Narayanasamy A, Govindasamy V, Giridharan B, et al. COVID-19: A promising cure for the global panic. Science of The Total Environment. 2020;725:138277 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali I, Alharbi OML. COVID-19: Disease, management, treatment, and social impact. Sci Total Environ. 2020;728:138861–. Epub 04/22. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138861 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. National Library of Medicine; [cited 2020 2 August]. Available from: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=0d93edc4-ae6e-1e16-e054-00144ff8d46c.

- 21.Shang A, Huwiler-Müntener K, Nartey L, Jüni P, Dörig S, Sterne JAC, et al. Are the clinical effects of homoeopathy placebo effects? Comparative study of placebo-controlled trials of homoeopathy and allopathy. The Lancet. 2005;366(9487):726–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67177-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ernst E. Is homeopathy a clinically valuable approach? Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2005;26(11):547–8. 10.1016/j.tips.2005.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molento MB. COVID-19 and the rush for self-medication and self-dosing with ivermectin: A word of caution. One Health. 2020;10:100148 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100148 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mhatre S, Srivastava T, Naik S, Patravale V. Antiviral activity of green tea and black tea polyphenols in prophylaxis and treatment of COVID-19: A review. Phytomedicine. 2020:153286 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mustafa MZ, Shamsuddin SH, Sulaiman SA, Abdullah JM. Antiinflammatory Properties of Stingless Bee Honey May Reduce the Severity of Pulmonary Manifestations in COVID-19 Infections. Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020;27(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman MT. Potential benefits of combination of Nigella sativa and Zn supplements to treat COVID-19. Journal of Herbal Medicine. 2020;23:100382 10.1016/j.hermed.2020.100382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected: interim guidance, 13 March 2020 World Health Organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Services DGoH. National Guidelines on Clinical Management of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19). http://www.mohfw.gov.bd/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=22424&lang=en.

- 29.Yıldırım M, Geçer E, Akgül Ö. The impacts of vulnerability, perceived risk, and fear on preventive behaviours against COVID-19. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2020:1–9. 10.1080/13548506.2020.1776891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Apisarnthanarak A, Apisarnthanarak P, Siripraparat C, Saengaram P, Leeprechanon N, Weber DJ. Impact of anxiety and fear for COVID-19 toward infection control practices among Thai healthcare workers. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 2020:1–2. Epub 06/08. 10.1017/ice.2020.280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta L, Gasparyan AY, Misra DP, Agarwal V, Zimba O, Yessirkepov M. Information and Misinformation on COVID-19: a Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(27):e256–e. 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e256 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zarocostas J. How to fight an infodemic. The Lancet. 2020;395(10225):676 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF)

(SAV)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.