Abstract

Objective

Older adult falls are a national issue comprising 3 million emergency department (ED) visits and significant mortality. We sought to understand whether ED revisits and hospitalisations for fallers differed from non-fall patients through a secondary analysis of a longitudinal, statewide cohort of patients.

Design

We performed a secondary analysis using the non-public Patient Discharge Database and the ED data from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. This is a 5-year, longitudinal observational dataset, which was used to assess outcomes for fallers and non-fall patients, defined as anyone who did not carry a fall diagnosis during this time period.

Setting

2005–2010 non-public Patient Discharge Database and the ED Data from the state of California.

Participants

Older adults 65 years and older

Main outcome measure

ED revisits and hospitalisations for fallers and non-fall patients.

Results

Patients who came to the ED with an index visit of a fall were more likely to be discharged home after their fall (61.1% vs 45.0%, p<0.001). Fallers who were discharged or hospitalised after their index visit were more likely to come back to the ED for a fall related complaint compared with non-fallers (median time: 151 days vs 352 days, p<0.001 and hospitalised: 45 days vs 119 days, p<0.01) and fallers who were initially discharged also returned to the ED sooner for a non-fall related complaint (median time: 325 days vs 352 days, p<0.001).

Conclusion

Fall patients tend to be discharged home more often after their index visit, but returned to the ED sooner compared with their non-fall counterparts. Given a faller’s rates of ED revisits and hospitalisations, EDs should consider a fall as a poor prognostic indicator for future healthcare utilisation.

Keywords: geriatric medicine, accident & emergency medicine, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first statewide, longitudinal secondary data analysis examining disposition and emergency department (ED) revisits of patients who came to the ED for a fall and compared fallers to all other older adults using a statewide database of approximately 3.8 million patients.

The use of administrative data limits our understanding of other associated variables such as comorbidities and true identification of a patient’s index visit for a fall.

The nature of the data does not allow us to understand the reason for fall, which is important for fall prevention purposes.

Background

Falls from older adults comprise nearly 3 million emergency department (ED) visits annually and account for 10% of all ED visits among those greater than age of 65 years.1 2 Mortality from falls increased by 110% from 1999 to 20163 and will rise as the population ages.

Adverse event rates for older patients who present to the ED after a fall is high. Over 70% of these patients are discharged after their ED visit, with the remaining 30% admitted to the hospital.1 Approximately, 36%–44% of patients who come to the ED after experiencing a fall experience a subsequent adverse event, including recurrent falls, ED visits or death within 1 year.4 5 Previous community-based falls prevention has helped prevent ED use and future hospitalisations. For instance, Mikolaizak et al found that older fallers who adhered to a paramedic-initiated assessment and intervention had fewer falls and fall-related ED presentations at 6 months.6 The PROFET trial showed that a multifactorial intervention for ED falls patients decreased recurrent falls and the odds of hospital admission at 12 months.7 However, it is not clear whether these adverse event rates are higher than those of non-fall patients. Identifying such patients can help risk stratify when deciding disposition, referring to outpatient services and recommending enrollment into community-based falls prevention programmes. To date, most studies on ED fall patients listing high adverse event rates are limited to one or few sites, are cross sectional or have no controls.2 5

We sought to explore whether the rate of ED revisits and hospitalisations among older fall patients differ significantly from non-fall patients in a large statewide cohort of ED patients that could be tracked longitudinally, with a specific interest on revisits for fall-related complaints. We hypothesised that fallers would revisit the ED and have more hospitalisations than their non-fall counterparts. Targeting at-risk older adults, particularly those discharged to home or home healthcare through community-based interventions or non-pharmacological clinical trials, is an underexplored, cost-effective mechanism with potential to reduce ED revisits and improve patient care.

Methods

Data sources

To determine the rate of ED revisits and hospitalisations for elderly patients who present to the ED after a fall, we used de-identified, patient-level data for the 2005–2010 non-public Patient Discharge Database (PDD) and the ED Data (EDD) from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. The PDD captures demographic and clinical data for all admissions to non-Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals in California. The EDD provides data on all ED encounters, including those patients discharged from the ED. We also used hospital utilisation data to capture hospital characteristics.

We included all adult patients aged 65 years and older that were seen in the ED. Fall patients were defined as patients who came for a fall-related complaint between 1 January 2005 and 12 December 2010 with the International Classification of Disease E codes E880.x-E888.x included anywhere in their visit (see figure 1). Non-fall patients were defined as all older patients seen in the ED between 1 January 2005 and 12 December 2010 with any other diagnosis. The censor time for death was 12 December 2011. More specifically, if a patient had non-fall visit before the fall visit for those aged >65 years, specific non-fall visit was not counted. However, if he/she had a non-fall visit after a fall visit, said patient was counted as a faller. For patients who never had a fall visit, all of their non-fall visits were counted.

Figure 1.

Falls diagnostic E codes.

The decision to use patient level in lieu of visit-level data stemmed from the need to look at both patient characteristics and longitudinal outcomes on disposition and revisits. As such, we obtained data, including age, sex, ethnicity/race, payer type and whether the visit was at a teaching versus non-teaching hospital. We calculated income based on zip code as a proxy8 and then examined disposition of the patient from the ED or after hospitalisation (ED death, or discharge from ED or hospital to an acute care facility, skilled nursing home or home with visiting nurse). This study used de-identified data but was approved by the institutional review board.

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient or public involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Outcomes

We examined the frequency of various dispositions (eg, where the patient was discharged to) from the ED between geriatric fall and non-fall patients. Our primary outcome was disposition and the median time to ED revisits for a fall between fall and non-fall patients. Our secondary outcome was the median time to an ED revisit for any reason between fall and non-fall patients. We also examined the frequency of at least one ED revisit for a fall as well as an ED revisit for any reason at 7 days and 30 days, 6 months and 1 year among fall and non-fall patients. We also performed a Kaplan-Meier analysis for time to revisit for any reason, controlling for age, sex, race, insurance, teaching and median income. For the sake of brevity, we termed those older adult patients who presented for a fall-related complaint as ‘fallers’ and those who did not fall as ‘non-fallers’.

Statistical analysis

We calculated differences in demographics using Wilcoxon, t-test or χ2 test where appropriate. We tested for differences of frequency of disposition type after initial ED visit between fall and non-fall patients using χ2 test. To access the median times to the ED revisits, we used a Cox model with a type 3 test of the effect of the eight-way classifications. To access survival rate to ED revisit, we fit a Cox model for the association of fall versus non-fall patients with time to each event, adjusting for age, sex, race, insurance, teaching hospital and median income. All analyses were completed using SAS V.9.4.

Results

The fall cohort predominantly consisted of women who were of 79.5 years of age compared with the non-fall cohort who were primarily men with an average age of 74.7 years (p<0.001). Fallers were also predominantly non-Hispanic white (71.3% vs 63.1%, p<0.001), seen primarily in non-teaching hospitals (92.5% vs 90.9%, p<0.001) with Medicare as their primary insurance (87% vs 80.9%, p<0.001). While non-fallers also predominantly used Medicare as their primary payer, they notably had a higher mix of non-Medicare primary payers, including commercial insurers (private), Medicaid and self-pay, compared with fallers. (table 1). Overall, fallers had a total of 4.76 million visits between 2005 and 2011, or approximately 4.78 visits per patient while non-fallers made 9.24 million visits in this time span or approximately 3.30 visits per patient (table 2A, B).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographics of elderly patients who fall to patients who did not fall

| Fall (N=997 524) |

Non-fall (N=2 805 508) |

P value | |

| Age (in years) | 79.5±8.3 | 74.7±7.9 | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 336 060 (33.7%) | 1 298 346 (46.3%) | <0.001 |

| Female | 661 152 (66.3%) | 1 506 065 (53.7%) | |

| Other | 312 (0.03%) | 1097 (0.04%) | |

| Ethnicity/race | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 710 852 (71.3%) | 1 770 408 (63.1%) | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 38 699 (3.9%) | 167 215 (6.0%) | |

| Hispanic | 133 594 (13.4%) | 433 837 (15.5%) | |

| Asian | 26 611 (2.7%) | 145 804 (5.2%) | |

| Other | 68 661 (6.9%) | 220 746 (7.9%) | |

| Unknown | 19 107 (1.9%) | 67 498 (2.4%) | |

| Median income | 67 290±24 323 | 66 563±24 330 | <0.001 |

| Payer type (primary insurance) | |||

| Self-pay | 14 471 (1.5%) | 57 962 (2.1%) | <0.001 |

| Medicare | 867 863 (87.0%) | 2 269 251 (80.9%) | |

| Medicaid | 19 220 (1.9%) | 106 590 (3.8%) | |

| Commercial Insurance/Commercial Health Maintenence Organization | 82 435 (8.3%) | 331 897 (11.8%) | |

| Other | 13 301 (1.3%) | 39 099 (1.4%) | |

| Missing | 30 (0.0%) | 170 (0.0%) | |

| Teaching hospital | |||

| No | 922 366 (92.5%) | 2 550 886 (90.9%) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 75 158 (7.5%) | 254 622 (9.1%) |

Table 2.

(A) Breakdown of all visits by year. (B) Fall versus non-fall generalised visit patterns

| Fall patients | Non-fall patients | Total | |

| A | |||

| Number of patients | 997 524 | 2 805 508 | 3 803 032 |

| Total visits | 4 769 880 | 9 245 450 | 14 015 330 |

| 2005 | 491 604 | 1 310 892 | 1 802 496 |

| 2006 | 554 715 | 1 258 444 | 1 813 159 |

| 2007 | 615 788 | 1 234 484 | 1 850 272 |

| 2008 | 687 179 | 1 280 194 | 1 967 373 |

| 2009 | 746 467 | 1 315 321 | 2 061 788 |

| 2010 | 807 063 | 1 370 785 | 2 177 848 |

| 2011 | 867 064 | 1 475 330 | 2 342 394 |

| B | |||

| Number of patients | 997 524 | 2 805 508 | 3 803 032 |

| Total visits | 4 769 880 | 9 245 450 | 14 015 330 |

| # visits per patient | 4.78±5.18* 3(2–6)† |

3.30±3.58 2(1–4) |

3.69±4.12 2(1–5) |

| # visits for fall patients | 1.53±1.05 1(1–2) |

NA | 0.40±0.86 0(0–1) |

| % revisit for fall patients | 291 025 | ||

*Mean±SD.

†Median (IQR).

Patients who came to the ED with an index visit of a fall were more likely to be discharged home after their fall (61.1% vs 45.0%, p<0.001) or sent directly to a skilled nursing facility (SNF) or an acute care facility from the ED (1.5% vs 0.3% and 0.2% vs 0.04%, respectively, p<0.001). Patients who came to the ED for non-fall related visit were more likely to be hospitalised (52.6% vs 35.7%); however, fallers who were admitted were more often transferred to an SNF or an acute care facility post-hospitalisation compared with non-fallers (47.5% vs 13.9% and 8.5% vs 4.9%, respectively, p<0.001), whereas non-fallers were more often discharged home post-hospitalisation (61.3% vs 23.3%, p<0.001) (table 3).

Table 3.

Type of disposition after initial ED visit for all patients (A), time to ED revisit for fallers (B) and time to ED revisit for non-fall patients (C)

| Frequency of disposition type after initial ED visit (A) | Median time to ED revisit among fall patients (B) | Median time to ED revisit for non-fall patients (C) | P value | |||||||

| Index visit: fall | Index visit: non-fall | P value | Reason for ED revisit: fall | Reason for ED revisit: any reason | Reason for ED revisit: any reason | |||||

| n | Days | n | Days | n | Days | n | Days | |||

| Discharge home from ED | 609 822 (61.13%) | 1 263 272 (45.03%) | <0.001 | 437 197 | 151.0 | 191 925 | 325.0 | 524 237 | 352.0 | <0.001 |

| Discharge with home health service from ED | 1519 (0.15%) | 1453 (0.05%) | 993 | 58.0 | 432 | 114.0 | 623 | 83.0 | ||

| Directly to SNF from ED | 15 387 (1.54%) | 9081 (0.32%) | 11 456 | 71.0 | 5247 | 137.0 | 5087 | 111.0 | ||

| Directly to acute care (IRF and LTCH) from ED | 2007 (0.20%) | 1166 (0.04%) | 1509 | 59.0 | 771 | 96.0 | 654 | 97.0 | ||

| ED death | 521 (0.05%) | 12 208 (0.44%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Other | 11 819 (1.18%) | 43 910 (1.57%) | 9321 | 30.0 | 5403 | 9.0 | 24 444 | 47.0 | ||

| Blank | 101 (0.01%) | 220 (0.01%) | 76 | 68.5 | 41 | 67.0 | 98 | 1.0 | ||

| Hospitalisation after ED visit | 356 348 (35.72%) | 1 474 198 (52.55%) | <0.001 | 269 385 | 45.0 | 109 751 | 242.0 | 956 264 | 119.0 | <0.001 |

| Then to acute care (IRF and LTCH) after hospitalisation | 30 363 (8.52%) | 72 214 (4.90%) | 28 514 | 5.0 | 12 452 | 69.0 | 64 385 | 4.0 | ||

| Then to SNF after hospitalisation | 169 084 (47.45%) | 204 991 (13.91%) | 134 491 | 40.0 | 53 465 | 246.0 | 150 005 | 35.0 | ||

| Then to residential care after hospitalisation | 4181 (1.17%) | 11 056 (0.75%) | 3338 | 64.0 | 1645 | 137.0 | 7950 | 86.0 | ||

| Discharge home after hospitalisation | 83 178 (23.34%) | 903 245 (61.27%) | 61 352 | 119.0 | 25 276 | 313.0 | 594 246 | 192.0 | ||

| Discharge home with health services after hospitalisation | 47 871 (13.43%) | 200 618 (13.61%) | 35 425 | 99.0 | 14 819 | 272.0 | 129 308 | 148.0 | ||

| Invalid/blank | 64 (0.02%) | 178 (0.01%) | 41 | 9.0 | 17 | 67.0 | 91 | 7.0 | ||

| Other | 3551 (1.00%) | 16 484 (1.12%) | 2556 | 17.0 | 1207 | 85.0 | 10 279 | 44.0 | ||

*Any reason excludes any visit pertaining to a fall.

ED, emergency department; IRF, inpatient rehabilitation facility; LTCH, long-term care hospital; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Fallers who were discharged after their index visit were more likely to come back to the ED for both a fall-related and non-fall-related complaint compared with non-fallers (median time: 151 days and 325 days vs 352 days, p<0.001) (table 3).

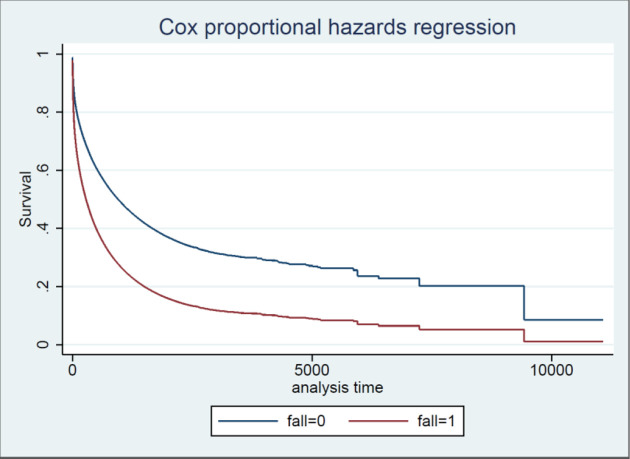

Fallers who were initially hospitalised returned to the ED sooner for another fall-related complaint compared with non-fall patients (45 days vs 119 days, p<0.001), but non-fallers returned earlier to the ED for any reason (excluding falls) compared with fallers (119 days vs 242 days, p<0.001) (see table 3). Furthermore, based on a Kaplan-Meier analysis, non-fallers had a lower probability of returning to the ED compared with fallers at each time point after adjusting for age, sex, race, insurance, teaching and median income (figure 2 and table 4).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve: time to emergency department revisit for any reason.

Table 4.

Survival time to ED revisit, fall versus non-fallers, adjusted for age, sex, race, insurance, teaching and median income (p=0.000)

| Days | Fall | Non-fall |

| 7 | 0.88 | 0.94 |

| 30 | 0.78 | 0.87 |

| 182 | 0.57 | 0.74 |

| 365 | 0.45 | 0.66 |

| 1826 | 0.18 | 0.38 |

It is worth noting that we could not calculate the rate of ED return among non-fallers for a fall-related visit as this would have placed them into the fallers cohort.

Discussion

Older adults who present to the ED with a fall between 2005 and 2010 were more likely to be older, female, non-Hispanic white, covered by Medicare and primarily present to community facilities as compared with those patients who presented to the ED for a non-fall-related complaint. Furthermore, fall patients were discharged home more often, but returned to the ED sooner for both a fall-related and non-fall-related complaint compared with their non-fall counterparts (p<0.001). This study is unique in that it is the first statewide, longitudinal secondary data analysis examining disposition and ED revisits of patients who came to the ED for a fall and compared fallers to all other older adults using a statewide database of approximately 3.8 million patients, but similar outcomes to a retrospective cohort study looking at fall-related, 30-day readmissions using the hospital cost and utilisation project data.9

This database shows that fallers appear to be a high-risk patient population who return to the ED much sooner than patients who did not fall for a second fall-related complaint regardless of whether they were admitted or discharged from their index ED visit. Often, fallers may minimise their reason for falling and are reluctant to engage in fall prevention efforts on their own.10 Also, most EDs do not do a comprehensive fall evaluation, thus missing many opportunities to address the risk factor that lead to the fall or prevent future falls.11 12 Although this study does not delineate the underlying reason for a fall or reason for their return ED visit, our findings suggest that this patient population warrants close evaluation, workup and follow-up to assess their reasons for falling and potential intervention.

Among hospitalised patients, non-fallers returned to the ED sooner than fallers for any other non-fall-related reason (p<0.001). This may be due to a sicker case-mix of non-fall patients reflected through the higher percentage of Medicaid among non-fallers or the higher percentage of non-fallers being treated at teaching hospitals containing tertiary services,13 14 or that more non-fallers were discharged home without services post-hospitalisation. However, this difference warrants further investigation.

Limitations

There were many limitations to this study including those inherent to the retrospective nature of this analysis. First, it is possible that what we classified as an index visit for a fall may not have been the actual first visit for a fall. Although some index visits for a fall may have occurred outside the state of California, we expect this number to be minimal. Second, because we are using administrative data, we have limited understanding of other important variables, including functional status, comorbidities and relative frailty of patients, which could contribute to the observed result. Third, as with any administrative dataset, there are potential errors due to miscoding, data linkage and missing data. However, these would not bias our study unless these errors were distributed unevenly across both categories of patients, which would be unlikely. Furthermore, while the dataset is statewide, results cannot be generalised across the entire country or other healthcare systems. Last, we do not have a reason for the fall, which is often important for fall prevention and may provide a better sense as to why patients who presented initially for a fall-related complaint are returning to the ED sooner than patients who did not fall.

Conclusion

This epidemiological study suggests that patients who fall are a sick patient population who are more likely to return to the ED for a second fall regardless of whether they are discharged or admitted and are more likely to return for any reason if discharged. Given the increasing rates of falls over time,2 providers should recognise the significance of a fall as a risk factor for future healthcare utilisation. Multiple studies have shown the benefit of multifactorial falls prevention interventions to decrease the rates of recurrent falls7 15 with a recent Cochrane Review underscoring the benefit of exercise and physical-therapy-based programmes as a particularly beneficial modality to decrease the rate of injurious falls.16 While the most recent randomized trial of multifactorial strategies did not show a benefit for community-based falls prevention for at-risk individuals, it did not assess prevention activities for ED patients after a fall and it also acknowledges that behaviour modification through exercise, one of the most important interventions for future fall prevention, was not underscored.17 18 Qualitative data indicates that patients who present to the ED may have more willingness for falls prevention10 and programmes should continue to capitalise on this motivation for secondary fall prevention strategies.19 Further studies should also look at the cause of falls and patients’ associated comorbidities as indicators for outcomes. EDs should also consider urgently referring discharged fall patients to physical therapy or an evidence-based exercise and/or falls prevention programme.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KS and SL conceived the initial study and drafted the manuscript. FL undertook the statistical analysis. FL, HE and ET contributed substantially to its revision. KS takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. Data may be obtained from a third party but are not publicly available. The data are not publicly available but can be obtained through written request to the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development.

References

- 1.Owens PL, Russo CA, Spector W, et al. Emergency department visits for injurious falls among the elderly. 80 Statistical Brief, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shankar KN, Liu SW, Ganz DA. Trends and characteristics of emergency department visits for fall-related injuries in older adults, 2003-2010. West J Emerg Med 2017;18:785–93. 10.5811/westjem.2017.5.33615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.QuickStats Age-Adjusted death rates from unintentional falls among adults aged ≥65 years, by sex — national vital statistics system, United States, 2000–2015. 66, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sri-on J, Tirrell G, Kamsom A, et al. A high-yield fall risk and adverse events screening questions from the stopping elderly accidents, death, and injuries (STEADI) guideline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu SW, Obermeyer Z, Chang Y, et al. Frequency of ED revisits and death among older adults after a fall. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33:1012–8. 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.04.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikolaizak AS, Lord SR, Tiedemann A, et al. Adherence to a multifactorial fall prevention program following paramedic care: predictors and impact on falls and health service use. results from an RCT a priori subgroup analysis. Australas J Ageing 2018;37:54–61. 10.1111/ajag.12465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Close J, Ellis M, Hooper R, et al. Prevention of falls in the elderly trial (PROFET): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 1999;353:93–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06119-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zip-code Characteristics: Mean and Median Household Income University of Michigan population studies center, Institute of social research, 2019. Available: https://www.psc.isr.umich.edu/dis/census/Features/tract2zip/index.html [Accessed Jun 2016].

- 9.Hoffman GJ, Liu H, Alexander NB, et al. Posthospital fall injuries and 30-day readmissions in adults 65 years and older. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e194276. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shankar KN, Taylor D, Rizzo CT, et al. Exploring Older Adult ED Fall Patients’ Understanding of Their Fall: A Qualitative Study. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2017;8:231–7. 10.1177/2151458517738440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tirrell G, Sri-on J, Lipsitz LA, et al. Evaluation of older adult patients with falls in the emergency department: discordance with national guidelines. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22:461–7. 10.1111/acem.12634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morello RT, Al et. Multifactorial falls prevention programmes for older adults presenting to the emergency department with a fall: systematic review and meta-analysis. Inj Prev 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation “Medicaid Enrollees Are Sicker and More Disabled than the Privately-Insured”. 14 The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, 2013. www.kff.org/medicaid/slide/medicaid-enrollees-are-sicker-and-more-disabled-than-the-privately-insured/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shahian DM, Nordberg P, Meyer GS, et al. Contemporary performance of U.S. teaching and nonteaching hospitals. Acad Med 2012;87:701–8. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318253676a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davison J, Bond J, Dawson P, et al. Patients with recurrent falls attending Accident & Emergency benefit from multifactorial intervention—a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2005;34:162–8. 10.1093/ageing/afi053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guirguis-Blake JM, Michael YL, Perdue LA. Interventions to prevent falls in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhasin S, Gill TM, Reuben DB, et al. A randomized trial of a multifactorial strategy to prevent serious fall injuries. N Engl J Med 2020;383:129–40. 10.1056/NEJMoa2002183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganz DA, Latham NK. Prevention of falls in community-dwelling older adults. N Engl J Med 2020;382:734–43. 10.1056/NEJMcp1903252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rimland JM, Abraha I, Dell’Aquila G, et al. Effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions to prevent falls in older people: a systematic overview. The SENATOR project ONTOP series. PLoS One 2016;11:e0161579 10.1371/journal.pone.0161579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.