Abstract

The polar organizing protein Z (PopZ) is necessary for the formation of three-dimensional microdomains at the cell poles in Caulobacter crescentus, where it functions as a hub protein that recruits multiple regulatory proteins from the cytoplasm. Although a large portion of the protein is predicted to be natively unstructured, in reconstituted systems PopZ can self-assemble into a macromolecular scaffold that directly binds to at least ten different proteins. Here we report the solution NMR structure of PopZΔ134–177, a truncated form of PopZ that does not self-assemble but retains the ability to interact with heterologous proteins. We show that the unbound form of PopZΔ134–177 is unstructured in solution, with the exception of a small amphipathic α-helix in residues M10-I17, which is included within a highly conserved region near the N-terminus. In applying NMR techniques to map the interactions between PopZΔ134–177 and one of its binding partners, RcdA, we find evidence that the α-helix and adjoining amino acids extending to position E23 serve as the core of the binding motif. Consistent with this, a point mutation at position I17 severely compromises binding. Our results show that a partially structured Molecular Recognition Feature (MoRF) within an intrinsically disordered domain of PopZ contributes to the assembly of polar microdomains, revealing a structural basis for complex network assembly in Alphaproteobacteria that is analogous to those formed by intrinsically disordered hub proteins in other kingdoms.

Keywords: NMR spectroscopy, PopZ, Intrinsic Disorder, Molecular Recognition Feature, Hub Protein

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Biological systems are inherently complex, often involving multistep biochemical pathways and multiple levels of regulation among a large number of physically and functionally interacting components. In many cases, interactive networks are highly dynamic, changing rapidly in response to regulatory signals and adjusting their connectivity to accommodate a range of activities. Interestingly, there is a positive correlation between higher levels of complexity and higher levels of structural disorder in networking components [1, 2]. At the core of these networks are intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and their intrinsically disordered domains (IDDs) that have little or no native structure outside of their interactions with other proteins. Moreover, the disordered nature of the protein binding interface is inherent to the function of dynamic, multi-partner binding interfaces [3], hereafter referred to as interaction hubs.

In cases where the IDD serves as the hub interface, core interface regions of IDD hubs tend to be 10–50 amino acids in length [4]. The contact sequence on the IDD side of a hub is a conserved region called a Molecular Recognition Feature (MoRF). A prominent example of an IDD hub protein is the tumor suppressor protein p53, which physically interacts with numerous binding partners via IDDs with MoRFs located in the N-and C-terminal sections of the protein [5–7]. There are a number of other examples of IDD hubs in eukaryotic systems [8–10], and their inherent networking capability may have been important in supporting the expansion of organismal complexity in this kingdom [1, 11]. Furthermore, investigations of IDP structure and function have direct implications for cancer research, as IDPs account for 79% of proteins associated with human cancer [12].

The structures of IDDs at hub interfaces can be investigated through X-ray crystallography [7], nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [13–15], and single molecule techniques [16]. These show that the core of the binding interface consists of a short series of amino acids from the IDD, generally less than 20 residues in length, which acquire a relatively constrained structure as they make direct contact with the globular binding partner. The constrained amino acids usually adopt an irregular coiled conformation, but α-helices and β-strands have also been observed at IDD binding interfaces, and these are predicted at frequencies of approximately 20% and 5%, respectively [17]. The structural flexibility of the IDD also gives the core binding region conformational heterogeneity in the bound state [18–20], allowing the IDD to shift between a range of potential conformations across a dimpled binding energy landscape with no clear minimum, leading to what is called the “fuzzy complex” model [21].

In a typical bacterial proteome, 6% of the amino acids are predicted to be disordered and as many as 40% of proteins contain an IDD with the general characteristics of a protein interaction motif [17]. Given the observed correlation between organismal complexity and the number of IDDs and IDD hub proteins in a proteome [1, 11, 22, 23], it is not surprising that IDDs mediate the assembly of complex structures in bacteria. The C-terminal region of FtsZ is an IDD that interacts with at least six other proteins during assembly and closure of the division ring at mid-cell [24–26]. Complex structures are also found at bacterial cell poles. In many species, cell poles are sites for the assembly of flagella, pili, and stalks [27–30], and they can also serve as locations for multiprotein complexes that regulate chromosome replication and the directionality of chromosome segregation [31, 32]. A well-characterized example of complex cell pole organization is Caulobacter crescentus, in which at least 100 different proteins are localized to one or both cell poles over the course of the cell cycle [33].

In C. crescentus and other Alphaproteobacteria [34, 35], a self-assembling pole-localized scaffolding protein called polar organizing protein Z (PopZ) plays a key role in the assembly of polar complexes [36]. In the absence of PopZ, multiple regulatory proteins fail to be recruited to the cell poles, and chromosomal centromeres fail to dock at their polar destination [37, 38]. Because PopZ has the capacity to self-assemble into oligomers and higher ordered structures [39], overproduction of the protein results in expanded scaffolds, which recruit polar regulatory proteins across a larger area of the cell pole [37, 38]. PopZ will also assemble into large macromolecular complexes when expressed in E. coli cells, and these structures will selectively recruit co-expressed binding partners [40, 41]. Thus far, ten different Caulobacter proteins have been found to co-assemble with PopZ in this system, and these include cell cycle regulators, mediators of chromosome segregation, and factors associated with cell polarization [41–44]. Together with additional evidence that supports direct physical interaction, the conclusion is that PopZ is an interaction hub that facilitates the assembly of multiprotein complexes.

The first 133 amino acids of PopZ were predicted to be intrinsically disordered [41] and distinct from the C-terminal self-assembly domain [39]. The IDD includes a 25 amino acid sequence at the extreme N-terminus that is required for co-assembly with nine of the ten interaction partners identified in E. coli co-expression experiments. Within this N-terminal sequence is a highly conserved stretch of 10–15 amino acids that is predicted to be α-helical and may function as a MoRF [39].

In this work, we have utilized solution NMR spectroscopy to determine the major conformational states of the N-terminal 133 amino acids of PopZ (PopZΔ134–177). Truncation of the C-terminus of PopZ inhibits the formation of higher assembly, thus PopZΔ134−177 stays soluble in solution. We have previously shown that this truncated variant is sufficient for interacting with multiple heterologous binding partners, even in the absence of homo-oligomeric assembly [41]. NMR analyses reveal a largely disordered protein with an α-helical region close to the N-terminus. We also characterize the interaction between PopZ and one of its binding partners, a cell cycle regulatory protein called RcdA [41, 45, 46]. Our analyses revealed that the binding region comprises the N-terminal α-helix region and a few amino acids proximal to it. Introducing a point mutation in the binding helical region (I17A) diminished the binding capacity of PopZΔ134–177 to RcdA. Thus, we conclusively define a MoRF region within PopZ and gain mechanistic insight into the function of this intrinsically disordered bacterial hub protein.

Results and discussion

Structure of PopZΔ134−177 by NMR spectroscopy

2D and 3D high resolution solution NMR spectra were acquired using a 700 or 800 MHz NMR spectrometer of the truncated PopZΔ134−177, which includes the first 133 residues followed by a Leu-Glu linker and 6xHis-tag. All data were processed using NMRPipe [47] and analyzed using Sparky from NMRFAM [48]. Uniform peak widths and intensities of NMR spectral peaks indicate PopZΔ134–177 was in a stable state necessary for NMR study. The intrinsic disorder of PopZΔ134–177 is shown by the 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum with the characteristic narrow 1H chemical shift dispersion typically seen for IDPs (Fig. S1), with the exception of sidechain amine and amide resonances from arginine and glutamine residues, respectively. Comparatively, ordered proteins tend to have a wider dispersion of 1H resonances than proteins without a well-defined fold [49]. The disordered nature of PopZΔ134–177 is further supported by the distinct lack of abundance of long-range interactions in 1H-15N NOESY data. Standard triple resonance experiments were performed for protein backbone and sidechain resonance assignments including HNCA, HNcoCA, HNCO, HNcaCO, HNCACB, CBCAcoNH, CCcoNH, HBHANH, HBHAcoNH, and HcccoNH. As such, 84.7% of the protein backbone was assigned, including the Leu-Glu linker on the C-terminus of PopZΔ134–177. For simplicity, the linker residues are referred to as L134 and E135 in assignments. A full list of the assignments, representative strip plot for making assignments, and schematic showing backbone assignment completeness is presented in the Supplemental Information (Table S1, Fig. S2 and S3, respectively). Most of the missing assignments were due to the abundance of proline residues, which account for 20% of the PopZΔ134–177 sequence. We were able to obtain partial conformational information on some of the proline residues by calculating the differences between proline Cβ and Cγ chemical shifts [50]. This analysis indicates that 11 of the 25 proline residues are linked to the preceding amino acid by a peptide bond that is in the trans conformation. Additionally, we observed a number of low-intensity peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum that indicate small subpopulations of PopZΔ134–177 conformers. Many of the peaks corresponded to residues next to proline, suggesting that these subpopulations are comprised of species with peptide bonds in the cis configuration.

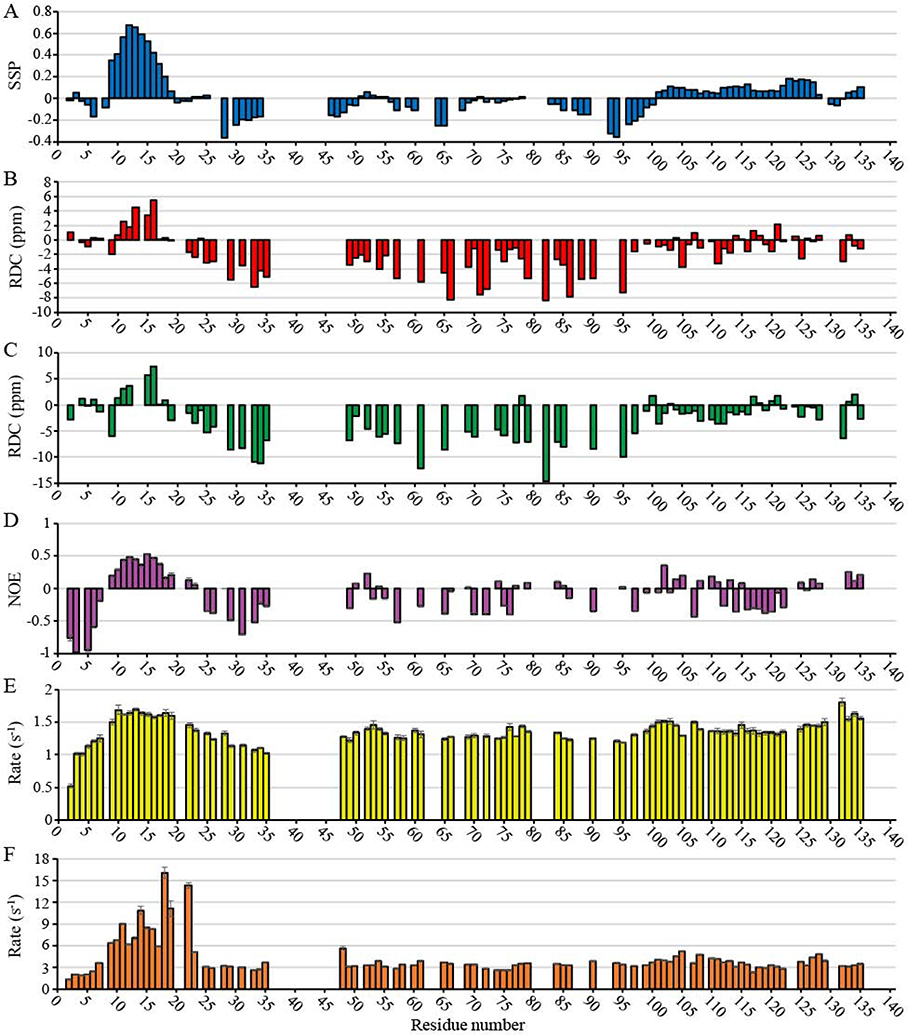

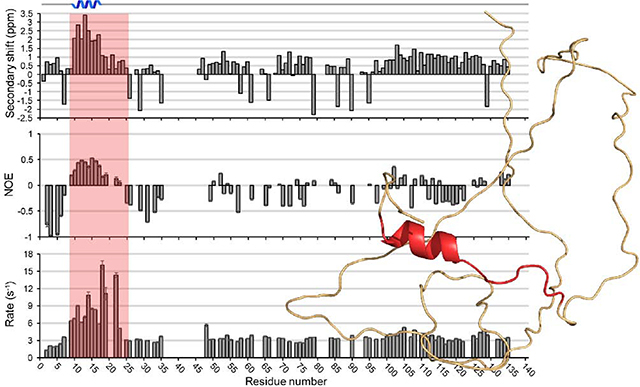

Carbon secondary chemical shifts are known to be strong reporters on secondary structural characteristics [51]. Typically, secondary chemical shifts are defined as the deviation of 13Cα, 13Cβ, and 13C (carbonyl) chemical shifts from those that are generated by random coil. 13Cβ secondary chemical shifts in PopZΔ134−177 spectra showed a continuous range of negative values between N-terminal residues T9-D25, while 13Cα secondary chemical shifts showed a range of positive values in this same region (Fig. S4). These data were plotted in a single structural propensity (SSP) plot [52] that indicates a helical motif in this part of the protein (Fig. 1A). Multiple correlations observed in the 15N- and 13C-edited NOESY-HSQC spectra support the existence of this helix (Fig. S5) including 45 sequential (|i – j|=1) and 13 medium-range (|i – j|≤ 4) correlations. Secondary chemical shifts tended to be more randomly oriented in the middle of the sequence (residues 46–100), as expected for an IDP. In the C-terminal region (residues 101–134), we observed a consistent, but small, α-helical propensity. In applying our data to the structural analysis program Ponderosa-C/S [53], we did not find evidence for a well-defined α-helix in the C-terminal region, although the consistent pattern of secondary shifts could indicate transient helical character.

Fig. 1. NMR characterization of PopZΔ134–177.

(A) Single structure propensity (SSP) plot showing predicted secondary structure domains across the PopZΔ134−177 sequence, where positive values represent helical propensity and negative values represent sheet propensity. (B) and (C) RDC measurements as a function of amino acid residue for a 5.4 mm (B) and 6.0 mm (C) outer diameter (OD) polyacrylamide gel axially stretched to 4.2 mm OD. (D) Heteronuclear NOE ratios observed as a function of amino acid residue. Positive values near the N-terminus are indicative of an ordered secondary structure. (E) R1 relaxation rates and (F) R2 relaxation rates observed as a function of amino acid residue. Larger values near the N-terminus are indicative of ordered secondary structure.

We obtained additional information on long-range orientation by measuring Residual Dipolar Coupling (RDC) in axially stretched polyacrylamide gels. We observed mostly negative couplings in the center of the sequence and a cluster of positive couplings in the suspected α-helical binding region, a pattern that is commonly observed for α-helices in this type of analysis [54]. The C-terminal region (residues 100–134) showed weaker couplings that were both positive and negative. We obtained dipolar coupling information for all residues except for 25 proline residues and 20 other residue couplings that could not be measured due to overlapping NH resonances (Fig. 1B and 1C).

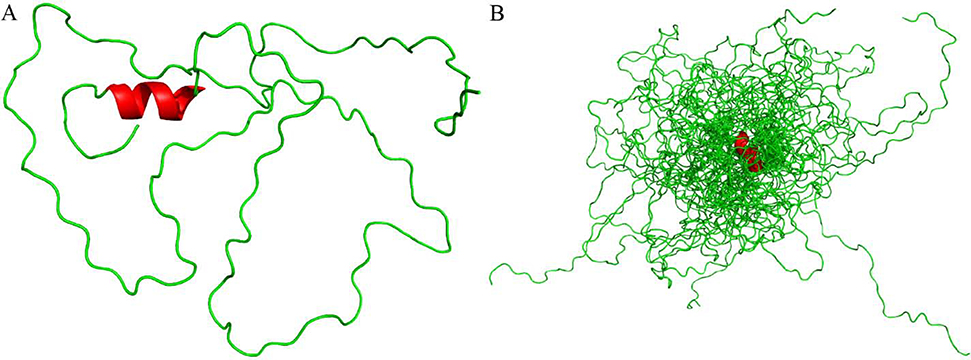

Torsion angle predictions for φ and ψ were generated from TALOS-N (Table S2). Chemical shift assignments, 15N-NOESY-HSQC and 13C-NOESY-HSQC peak lists, and RDC restraints were uploaded to Ponderosa-C/S server [53] for structure calculations. The 20 most favored structures were uploaded to the Protein Structure Validation Software [55] suite for validation. Global quality scores were good, and Ramachandran plots from MolProbity found 85.6% of all residues in most favored regions, 9.5% in allowed regions, and 4.9% in disallowed regions. 97.2% of ordered residues were in favored regions. A more detailed analysis of the validation is presented in Table S3. The 20 predicted structures show no other well folded secondary structure elements besides an N-terminus α-helix (M10-I17) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. PopZΔ134−177 structural ensemble.

(A) PopZΔ134−177 cartoon structure generated from Ponderosa-C/S [53] and visualized using PyMOL [58]. Green represents disorder along the sequence and red represents a short α-helical secondary structure on the N-terminus. (B) PopZΔ134−177 cartoon overlay of the top 20 best-evaluated structures generated from Ponderosa-C/S [53].

Additional analysis was carried out using the CIDER (Classification of Intrinsically Disordered Ensemble Regions) server [56], which is generally utilized to calculate and present the various sequence parameters commonly associated with disordered protein sequences. The analysis yielded low values for fraction of charged residues, FCR (0.256) and net charge per residue, NCPR (−0.195). Kappa (κ), a patterning parameter describing mixing vs. segregation of charged residues in the linear protein sequence was calculated to be 0.202, and omega (Ω), an analogous parameter that takes into consideration prolines [57], was 0.244. The CIDER results indicated that (i) the net charge per residue was generally negative with the exception of a small net positive region close to the N-terminus (Fig. S6A), (ii) the charged residues are relatively well-mixed with other residues throughout the protein primary sequence, and (iii) that the proline and charged residues were also well-mixed. The PopZΔ134–177 sequence is predicted by CIDER to fall within region 2 of the diagram of states (Fig. S6B), the boundary region between weak and strong polyampholytes. The CIDER results are summarized in Table S4.

Protein Dynamics

To obtain information of structure dynamics, we determined hetero NOE ratios (Fig. 1D) and longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation times, as well as their respective R1 and R2 relaxation rates (Fig. 1E and 1F, respectively), for the majority of the PopZΔ134–177 sequence. Global T1 and T2 values could not be accurately determined due to the disordered nature of the protein. Hetero NOE values showed primarily small magnitudes of negative sign. However, a range of positive NOE values, typically seen with α-helical character, was observed between residues T9 and R19. Additionally, we observed shorter T1 relaxation times for T9-R19 relative to other residues, and shorter T2 times across T9-E23 were also observed, and these local decreases are indicative of α-helical character.

PopZΔ134−177 binding studies

We and others have previously shown that PopZ binds to at least ten different binding partners [41–44]. Additionally, when 15N-enriched PopZΔ134−177 was mixed with saturating concentrations of two different unlabeled protein binding partners, we observed that both protein-bound conformations exhibited a nearly identical set of changes in 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra. This suggests that PopZΔ134−177 interacts with these two binding partners via the same set of amino acids. In this study, we have continued the binding experiments with one of those binding partners, RcdA. In C. crescentus, RcdA is co-localized with PopZ at one of the cell poles at the time of chromosome replication initiation [59], and it serves as an adaptor that interacts with specific protein substrates and links them to the ClpXP protease for degradation in vitro [60] and in vivo [44, 59]. PopZ interaction appears to be functionally separable from protease adaptor activity, suggesting that RcdA has multiple binding interfaces [61, 62]. By observing 1H-15N HSQC spectra of isotopically labeled PopZΔ134−177 under multiple RcdA concentrations and at a higher magnetic field (700 MHz), we obtained sufficient resolution for accurate peak identification even in congested regions of the spectra.

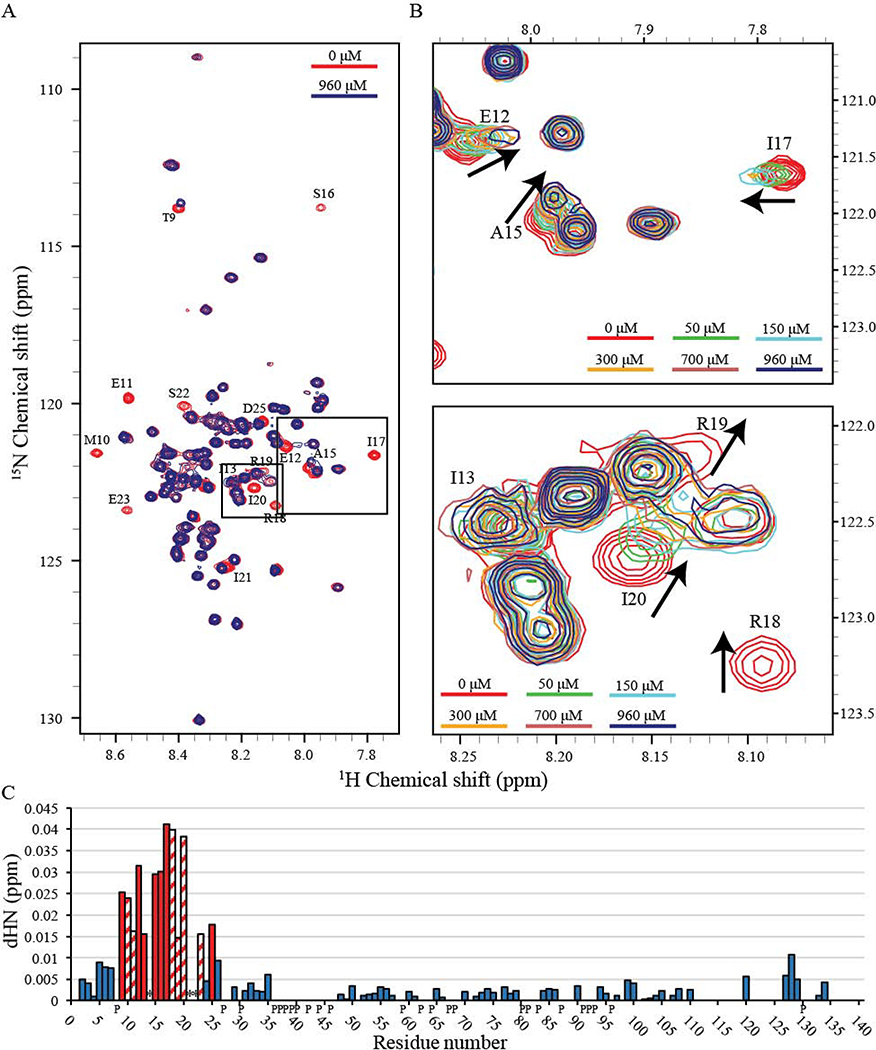

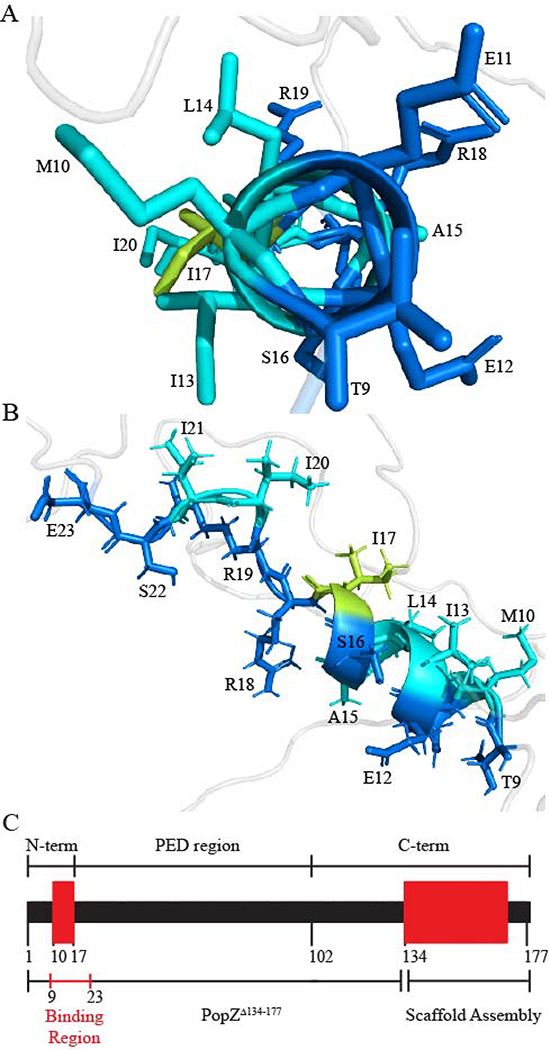

2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra were acquired from 130 μM 15N-enriched PopZΔ134−177 in the presence of unlabeled RcdA binding partner at a range of concentrations between 0 and 960 μM (Fig. 3A and 3B). Most PopZΔ134−177 NMR peaks remained unchanged in all conditions, indicating residues that do not interact with RcdA. For a minority of PopZΔ134−177 residues, increasing concentration of RcdA caused chemical shift perturbation and spectral broadening, and in some cases led to severe signal attenuation or loss of detection. Those peaks that display the greatest shifts and broadening likely indicate residues that interact directly with RcdA, while peaks that display moderate signal attenuation and chemical shift perturbation likely correspond to amino acids that participate in secondary or indirect binding interactions. Binding residues were determined by comparing combined ΔHN chemical shifts for each residue, where peaks undergoing a shift greater than the standard deviation were considered binding [63]. Combined ΔHN chemical shift perturbations (Fig. 3C) and peak intensity perturbations (Fig. S7) of PopZΔ134−177 upon binding to RcdA reveals that the binding motif of PopZΔ134−177 is between T9-E23 (Fig. 4 and Fig. S8), as peaks corresponding to these residues undergo both significant chemical shift perturbations and line broadening most likely due to direct interaction with RcdA, although potential secondary structure changes cannot be excluded. Residue D25 is expected to experience indirect binding effects, as it exhibits chemical shift perturbation but no significant broadening. Notably, the α-helix (M10-I17) determined by our structural model is found within the RcdA binding region. A schematic of full-sequence PopZ showing secondary structure elements and the proposed binding region is shown in Fig. 4C.

Fig. 3. Binding of PopZΔ134−177 to RcdA.

2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra overlay of 15N-enriched PopZΔ134−177 in solution with and without the RcdA binding partner exhibit spectral changes upon binding. Colored bars show RcdA concentration for each spectrum. (A) 130 μM PopZΔ134−177 with differing concentrations of RcdA: 0 μM (red) and 960 μM (blue). Peaks undergoing significant change are labeled. For simplicity, the spectra were shown without the sidechain region. Dashed boxes represent regions seen in (B). (B) Enlarged regions highlight changes upon increasing RcdA concentration. Arrows indicate direction of peak shift. Binding of RcdA resulted in the chemical shift perturbation and significant broadening of a number of peaks. The contours were lowered in the spectra with high concentration of RcdA to show weak peaks. (C) ΔHN combined chemical shift perturbations of PopZΔ134−177 upon binding to RcdA. Binding is indicated by the most pronounced chemical shift perturbations (red) found between residues T9-E23. The patterned columns represent residues that perturbed beyond detection before saturation was achieved. Therefore, the perturbation data from these patterned columns are from the last titration point where the peak was observed. Asterisks indicate residues with significant perturbations that we were not able to determine precisely due to severe peak overlap. “P” labels on the x-axis indicate proline residues which inherently cannot be observed in 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra.

Fig. 4. Binding motif of PopZΔ134–177.

(A) The amphipathic nature of the helix is shown from this perspective, where hydrophobic residues are colored cyan and hydrophilic residues are colored blue. I17, a critical residue for binding, is colored limon for distinction. Hydrogen atoms have been removed for simplicity. (B) The binding motif as viewed from the side. Structures were generated from Ponderosa-C/S [53] and visualized using PyMOL [58]. (C) Schematic of full sequence PopZ. Secondary structure elements are shown in red and disordered regions are shown in black. Sections are separated to show the N-terminus, proline-glutamate rich domain (PED), C-terminus, binding region, and scaffold assembly region.

While most perturbed peaks broadened beyond detection, some peaks were still detectable in the baseline when we significantly lowered the contour levels of the spectra (Fig. 3B). Residues L14, I21, and S22 are likely binding as well, but their exact chemical shift perturbation could not be determined due to extensive overlap with neighboring peaks. T9 and E23 (residues at the edge of the binding region) showed only a moderate amount of chemical shift perturbation and signal broadening, which is likely induced by secondary or indirect binding effects. D24 showed little change. The chemical shift perturbations that we observed in these experiments are closely matched with those produced by another binding partner, ChpT [41], indicating that the same subset of amino acids in PopZΔ134−177 participate in binding to both partners. We therefore conclude that residues T9-E23, which include an α-helix that spans M10-I17, act as a MoRF region that is directly responsible for interacting with at least two of its binding partners. Similar observations of chemical shift perturbations have been reported in the bound conformations of other MoRFs, including one in the C-terminal domain of p53 [9, 64, 65]. Interestingly, CIDER results indicated that the net charge per residue across the PopZΔ134−177 sequence is generally negative with the exception of a small net positive region in the MORF region due to residues R18 and R19 (Fig. S6A). This could suggest that the dispersion of positive and negative charge within the binding region is critical for the electrostatic interaction between PopZ and its protein binding partners.

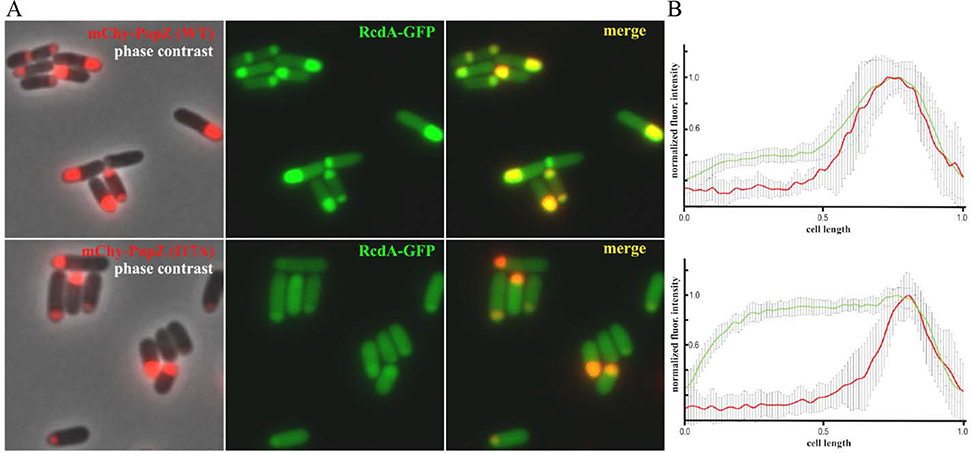

To obtain genetic evidence for the functionality of the predicted MoRF in PopZΔ134−177, we introduced a point mutation into the most highly conserved residue within the T9-E23 region by replacing Ile 17 with Ala (I17A). Notably, the 1H-15N HSQC spectral peaks corresponding to the α-helix were perturbed compared to wildtype PopZΔ134−177 spectra, indicating the I17A mutation disrupts the binding site. Adding excess RcdA (up to 1.0 mM) to 120 μM I17A PopZΔ134−177 did not induce spectral shifts or broadening (Fig. S9), indicating that binding did not occur. This indicates that I17 of PopZΔ134−177 is critical for binding RcdA in vitro. We also tested RcdA binding in an E. coli co-expression assay (Fig. 5). Here, RcdA was produced as a fusion protein with green fluorescent protein (RcdA-GFP) and co-expressed with either full-length wildtype PopZ or the full-length I17A mutant (each produced as fusions with mCherry for visualization by fluorescence microscopy). Due to the presence of the C-terminal self-assembly domain in full-length PopZ, both of the PopZ variants accumulated at the cell poles of the bacteria [39]. RcdA-GFP exhibited strong co-localization with wildtype PopZ, but much weaker co-localization with the I17A mutant, confirming the interaction defect.

Fig. 5. Localization of RcdA-GFP and wildtype or I17A mutant PopZ in an E. coli co-expression assay.

(A) Full-length wildtype PopZ (upper panels) or the I17A point mutant (lower panels) was fused to the C-terminus of mChy (red signal) and co-expressed in E. coli cells with RcdA-GFP (green signal). Single channel fluorescence images are overlayed on a phase contrast image (left panels), shown independently (center panels), or overlayed to show co-localization of fluorescent proteins (right panels). (B) Distributions of mChy-PopZ and RcdA-GFP are shown by plotting normalized fluorescent pixel intensities (Y-axis) as a function of cell length (X-axis), with cells oriented such that 0 marks open poles and 1 marks poles with mChy-PopZ foci (n=10). Bars show standard deviation between cells.

Discussion/Conclusions

In this work, we have structurally characterized the multi-protein binding domain of the alphaproteobacterial hub protein PopZ. Native PopZ is 177 amino acid residues in length, and we have investigated a truncated version, PopZΔ134−177, which includes the first 133 residues, a short linker, and 6xHis-tag. In the unbound form of PopZΔ134−177, we find that the critical binding motif includes a short α-helical segment between residues M10 and I17, with additional unstructured residues on either side. To analyze a bound form of PopZΔ134−177 and probe the binding interface, we used NMR titration studies against a binding partner, RcdA. We found that residues T9-E23 bind either directly or indirectly to the RcdA, forming a MoRF that may include a mixture of α-helical and coiled features. Residue I17, which lies at the center of the binding motif, remains critical for the interaction, and disruption of this residue leads to significant perturbation of the MoRF spectral peaks and drastic loss in binding. Adjacent to I17 lie R18 and R19, which contrast with the generally negative charge of PopZΔ134−177 in forming a small island of positive charge. Positive charges at these positions are evolutionarily conserved and are likely to be important for electrostatic interactions between PopZ and its binding partners. Consistent with this, changing R19 to glutamate contributes to the loss of binding affinity to ParA and ParB [66].

In earlier work we used NMR spectroscopy to demonstrate binding between PopZΔ134−177 and a different binding partner, ChpT [41]. Comparison of the spectra from RcdA and ChpT binding showed a nearly identical pattern of chemical shift perturbations, suggesting that both proteins interact with the same set of amino acids in PopZΔ134−177, even though these two proteins exhibit no sequence or structural homology [62, 67]. The only significant difference was in the peak corresponding to D25, located at the C-terminal end of the binding region, which did not show significant perturbation in complex with ChpT.

The cell cycle-dependent timing and intensity of polar localization of PopZ binding partners differ significantly and are not directly proportional to the localization pattern of PopZ. The transmembrane scaffolding protein SpmX is recruited by PopZ to the stalked pole [43], whereas transmembrane histidine kinases DivL and CckA, which are also direct binding partners of PopZ, are localized to the opposing swarmer pole or distributed between the two poles, respectively [68]. Other PopZ binding partners, including RcdA, ChpT and the protease adaptor protein CpdR [69], are localized transiently to the stalked pole. Such wide variation in timing and localization of PopZ binding partners could not occur if polar localization were determined simply by the ability to interact with PopZ, and this suggests the existence of regulatory mechanisms that affect PopZ interaction. Kinases, their downstream effectors, and other factors that regulate the production and degradation of the secondary messenger c-di-GMP exhibit highly polarized localization and activity in C. crescentus [70–72]. PopZ binds directly to some of the elements within these signaling networks, and in doing so it could establish feedback loops that reinforce polar asymmetry through a signal that increases or decreases PopZ’s affinity for certain binding partners. Protein phosphorylation is one potential signal, as interactions involving eukaryotic IDPs can be regulated in this manner [73–75]. The symmetry-break in C. crescentus could be established by cell division, if the PopZ that accumulates at the newly formed pole establishes different signaling complexes than PopZ at the old pole.

We have shown that the PopZ side of the binding interface includes an alpha helix. Binding helices are common in eukaryotic IDP hub domains, and there are multiple examples of interactions that are mediated by a single helix [76–79]. In many IDPs, relatively stable elements of secondary structure called αMoRFs form the core of the binding interface, and these are thought to aid binding by providing pre-formed structure that increases the stability of the bound complex [80–82]. Our structural analysis of PopZΔ134−177 demonstrates an αMoRF in Alphaproteobacteria, a feature that appears to be less common in bacterial proteomes than in eukaryotic proteomes [17]. Another bacterial protein with comparable structural and functional qualities is the divisome assembly protein FtsZ, which has a C-terminal IDP hub domain consisting of a disordered linker followed by a MoRF. In complex with different binding partners, FtsZ’s MoRF region can be partially α-helical [25, 83] or an extended linear motif [26]. For FtsZ, a destabilized αMORF may provide increased structural flexibility that allows binding to a wider range of binding surfaces. While our results suggest that the MoRF in PopZ is α-helical, transient unfolding is likely to occur, and some binding complexes may utilize other structural conformations of this region [84].

Since our analysis of secondary structure was limited to the unbound state of PopZΔ134−177, a remaining question is whether the helical region in the N-terminal MoRF of PopZΔ134−177 is altered upon interaction with binding partner proteins. For some IDPs, the transition from unbound to bound state involves the formation of additional α-helices [85], extension of a preformed helix [86], or stabilization of coil [87]. Similarly, the bound form of PopZΔ134−177 could acquire more complex structural character through stabilization of features on either side of the M10-I17 helix. Consistent with this, we find that the set of amino acids that undergo chemical shift perturbation during interaction extends out to residue D25 for RcdA or E23 for ChpT. We note that M10-I17 forms an amphipathic helix (Fig. 4A), and that the amphipathic nature of this structure would continue if the helix were extended to E23. Furthermore, secondary structural prediction algorithms consistently predict that the helix extends to at least I21 or S22 [46, 88]. Together, the evidence suggests that the helical portion of the PopZΔ134−177 αMoRF could include several amino acids beyond I17 in the bound form of PopZΔ134−177, though further studies will be needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Our finding that the I17A mutation inhibits the interaction between PopZ and RcdA is consistent with earlier studies, which show that cell division defects in a popZ deletion strain can be rescued by expression of wildtype PopZ. The I17A mutant cannot rescue the cell division defects in a popZ deletion strain, and the I17A mutant PopZ protein fails to recruit a direct binding partner, SpmX, to the cell pole [39, 43]. Similarly, PopZ bearing an I13A point mutation was found to be partially functional in rescuing popZ deletion phenotypes. We propose that the hydrophobic side of the amphipathic PopZ αMoRF (which includes I13 and I17) fits into a hydrophobic groove on RcdA, ChpT, SpmX, and other binding partners, in a manner that is analogous to the interaction of the amphipathic PUMA αMoRF with Mcl-1 [78]. Hydrophobic residues have been shown to increase binding affinity in MoRF regions [89], as demonstrated for PUMA [90] and other binding helices in IDPs [91, 92]. Mutations in charged and polar amino acids in the N-terminal region of PopZ appear to have variable effects on binding. For example, the E12K R19E double mutation inhibits binding to ParB but not ParA, while the S22P mutant inhibits binding to ParA but not ParB [66]. It may be that all or most of PopZ’s binding partners use contact with the hydrophobic side of the helix formed by M10-I17 to form a “fuzzy” binding intermediate [21], but that these interactions are not strong enough to lead to longer-term binding without additional contacts on other faces of the helix or peripheral contacts outside of the core helix.

In light of the fact that PopZ forms trimers, hexamers, and higher ordered structures in vivo [39, 46], it is also possible that multiple M10-I17+ MoRF helices work together to form a complex interface that binds the target protein. Although our results do not rule this model out, we note that our data was collected with a truncated form of PopZ that does not self-assemble [39]. A related question is how the large, ~80 amino acid disordered region on the C-terminal side of the αMoRF region of PopZ contributes to binding. While total deletion of the disordered region results in loss of PopZ function, it can be reduced to half size and also scrambled without having strong effects on the ability to interact with other proteins [41] or complement the popZ knockout phenotype in vivo [39]. This region may be a flexible linker that separates the PopZ C-terminal oligomerization domain (residues 134–177) from the MoRF, while also contributing to the structural disorder that facilitates “fuzzy complexes” between IDP and target proteins [21, 93]. We suggest that PopZΔ134−177 binds and reels the binding partners to the superstructure through sampling of its various disordered conformers, where a wide range of motion increases the likelihood of encountering and binding to other proteins in its local environment. This is similar to the fly-caster model for other IDPs [94], although there is no clear evidence to suggest that PopZ would fold upon binding. Oligomerization of full-length PopZ via the C-terminal domain, which is predicted to be highly structured, may act as an anchor around which these binding events occur. Another possibility that is not mutually exclusive is that the disordered domain creates a phase-separated droplet [95], and this may provide a microenvironment that is conducive to hub binding activity, as has been proposed for the organization of transcription factor complexes in eukaryotes [96].

Materials and methods

PopZΔ134−177 and RcdA protein expression and purification for NMR experiments

The expression and purification of PopZΔ134−177 protein was described previously [41]. Briefly, wild-type PopZΔ134−177 was cloned into the E. coli expression vector pET28a (Novagen) with a 6xHis-tag and Leu-Glu linker (strain YA#134, see Table S5. U-15N and U-13C, 15N enriched variants of PopZΔ134−177 were produced by expressing the proteins in minimal media supplemented either with 15NH4Cl (for uniform labeling with nitrogen-15) or 15NH4Cl and 13C6-glucose (for uniform labeling with nitrogen-15 and carbon-13), respectively. A plasmid carrying the PopZΔ134−177 gene with the I17A mutation was also constructed (strain YA#129, see Table S5. U-15N enriched I17A PopZΔ134−177 were expressed in minimal medium supplemented with 15NH4Cl. Isotopes were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.

PopZΔ134−177 was expressed for 12 hours by shaking at 37 °C after induction. Cell pellets were resuspended in Buffer A (25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole at pH 7.5) supplemented with Halt EDTA-free protease inhibitor and Benzonase nuclease. The cells were lysed using a French press. The protein was purified by two rounds of Ni-affinity chromatography using a Fast Protein Liquid Chromatography instrument (FPLC; GE Healthcare ÄKTA purifier 900 equipped with GE Healthcare HisTrap HP 1 ml column). The protein fractions were pooled and the buffer was exchanged to Buffer B (25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.5). The purity of the sample was analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie blue.

The expression and purification of the RcdA protein was described previously [41]. In short, natural abundance SUMO-RcdA fusion protein was expressed in E. coli by shaking the cells in LB medium for 12 hours at 21 °C after induction. Cell pellets were resuspended in Buffer C (20 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 20 mM imidazole at pH 7.5). Cells were lysed using a French press and the protein was purified by two rounds of Ni-affinity chromatography using FPLC. The protein was buffer exchanged into Buffer D (25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl at pH 7.5), and the fusion protein was cleaved by SUMO Express Protease (Lucigen). After cleavage, the protein samples were purified by Ni-affinity chromatography using FPLC. The protein was buffer exchanged to Buffer E (20 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2 at pH 7.5) for NMR experiments. The purity of the samples was analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie blue.

NMR spectroscopy

For NMR assignment experiments, the purified PopZΔ134−177 was buffer exchanged into Buffer F (50 mM phosphate, 50 mM citric acid, 20 mM NaCl, and 3 mM NaN3 at pH 5.5). D2O, NaN3, and DSS were added to a 5% v/v, 4 mM, and 0.2 mM final concentration, respectively, at a final PopZΔ134−177 concentration of 0.90 mM. The protein concentration was estimated using UV-Vis spectrophotometry (ε280 =2,980 cm−1 M−1). The NMR sample was packed into a 5-mm Shigemi NMR tube. The 2D 1H-15N Heteronuclear Single Quantum Correlation (HSQC) NMR spectrum and standard protein backbone and side-chain NMR spectra (including 3D HNCA, HNcoCA, HNCO, HNcaCO, HNCACB, CBCAcoNH, CCcoNH, HBHANH, HBHAcoNH, and HcccoNH, 15N- and 13C-edited NOESY) were collected at 25 °C on a Bruker AVANCE III HD 800 MHz NMR spectrometer (CUNY Advanced Science Research Center, New York, NY) equipped with a 5-mm triple resonance inverse TCI CryoProbe. All NMR data were processed using NMRPipe [47]. Analysis and assignments of the 2D and 3D data sets were carried out using NMRFAM-Sparky [48]. The assignment process was facilitated by using the PINE server for initial automated assignments [97, 98] before completing the assignments manually. The secondary chemical shift values were calculated by subtracting experimental chemical shift values from random coil values supplied by NMRFAM-Sparky. Relaxation and heteronuclear NOE data were analyzed using the Dynamics Center software package (Bruker BioSpin, Inc).

To characterize the binding site of PopZΔ134−177 to RcdA, a series of 130 μM 15N-enriched PopZΔ134−177 samples were prepared in the presence of varying concentration of RcdA in Buffer E: 0 μM RcdA (PopZΔ134−177 only), 50 μM RcdA, 100 μM RcdA, 150 μM RcdA, 200 μM RcdA, 300 μM RcdA, 500 μM RcdA, 700 μM RcdA, 900 μM RcdA, and 960 μM RcdA. 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra were collected on all samples at 25 °C on a Bruker AVANCE III HD 700 MHz NMR spectrometer (CUNY Advanced Science Research Center, New York, NY). Combined 1H and 15N chemical shift perturbations (ΔHN) were calculated using Equation 1,

| Eq. 1 |

where ΔH and ΔN are the chemical shift perturbations in ppm for 1H and 15N, respectively, and 0.15 is a scaling factor corresponding to the relative chemical shift dispersion in the 1H and 15N dimensions.

Residual dipolar coupling (RDC)

For RDC NMR experiments, the purified PopZΔ134−177 was buffer exchanged into Buffer F. The protein was concentrated and D2O, NaN3, and DSS were added to a 5% v/v, 4 mM, and 0.2 mM concentration, respectively, at a final PopZΔ134−177 concentration of 0.20 mM. The protein sample was used to rehydrate a 5.4 mm or 6.0 mm (outer diameter) gel previously cast and dehydrated (see RDC gel preparation below). The gel was stretched into a New Era Enterprises 4.2 mm (inner diameter) NMR tube for RDC NMR experiments. The 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectrum was collected at 25 °C on a Bruker AVANCE III HD 800 MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a 5-mm triple resonance inverse TCI CryoProbe.

RDC gel preparation

RDC gel preparation and sample preparation were performed using New Era Enterprises gel kits. A 5.4% acrylamide RDC gel was created by mixing 40% bis-acrylamide purchased from Bio-Rad with water and polymerized with 0.1% w/v ammonium persulfate and 0.1% v/v TEMED. This was cast in a New Era Enterprises gel stretching chamber and allowed to polymerize overnight at room temperature with the chamber sealed with parafilm to prevent leakage. The gel was removed from the chamber and dialyzed in pure water for 8 hours followed by a second round of dialysis in fresh water. The gel was then cut to approximately 2.1 cm in length using a razor blade and then dehydrated on a flat surface for 18–24 hours in a desiccator at room temperature. The dehydrated gel was placed back in the gel chamber and the gel was incubated overnight with the protein solution at 4 °C before being stretched into a New Era Enterprises 4.2 mm (inner diameter) NMR tube using a New Era Enterprises gel stretching kit. The end of the gel was slowly pressed out of the tube until approximately 2.1 cm in length was left in the tube. The protruding section of the gel was cut off using a razor blade.

Structural Constraints

Backbone angles and secondary structure elements were predicted using TALOS-N [99]. Xplor-NIH based calculations from the Ponderosa-C/S package [53] calculated the conformational states with the Ponderosa-X refinement option which utilized chemical shift values, distance constraints from 1H-15N HSQC NOESY and 1H-13C HSQC NOESY spectra, and residual dipolar coupling (RDC) constraints [100]. Weighting factors were kept at default values. Tolerance levels were set at 0.35, 0.35, and 0.025 ppm for N, C, and H, respectively. Constraint violations from the top 20 best-evaluated structures were analyzed using Ponderosa Analyzer [53, 101] and structural calculations were subsequently refined in iterative steps using the Constraints only-X option. Finally, an ensemble of 100 conformers was calculated using the final step option with a following explicit water refinement force field by Xplor-NIH [102]. The explicit water refinement consisted of the following steps: (1) immersion in a shell of water (7 Å) and energy minimization; (2) slow heating from 100 to 500 K in 100 K temperature steps with 200 molecular dynamics (MD) steps per temperature step with 3 fs time steps; (3) refinement at 500 K using 2000 MD steps with 4 fs time steps; (4) slow cooling from 500 K to 25 K in 25 K temperature steps with 200 MD steps per temperature step with 4 fs time steps; (5) 200 steps for final energy minimization [103]. The 20 best evaluated structures were submitted to the Protein Structure Validation Software (PSVS) [55] suite for structural validation.

CIDER analysis

Sequence analysis of PopZΔ134–177 (without the Leu-Glu linker and 6xHis-tag) was performed by accessing CIDER [56] at http://pappulab.wustl.edu/CIDER/analysis/.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Overnight cultures of E. coli bearing plasmids pACYC+mCherry-PopZ (or pACYC+mCherry-PopZ I17A) and pBAD+RcdA-GFP (strain YA#138, YA#142, see Table S5 were diluted 100-fold in fresh LB media and grown for 2 hours at 30 °C before stimulation of mChy-PopZ and RcdA-GFP expression with 100 μM IPTG and 0.005% arabinose, respectively. For induction of pACYC+mCherry-PopZ I17A, 140 μM IPTG was added to keep the expression equivalent to pACYC+mCherry-PopZ expression. Cells were immobilized on a 1% agarose gel pad and viewed with a Zeiss Axio Imager Z2 epifluorescence microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu Orca-Flash 4.0 sCMOS camera and a Plan-Apochromat 100x/1.46 Oil Ph3 objective. Zen Blue software was used for image capture and quantification. Ten representative cells from WT and I17A mutant PopZ samples were chosen. Cells with mChy-PopZ foci at both poles were excluded. Pixel intensities (after subtracting average background fluorescence) were measured along a straight line drawn lengthwise through the middle of the cells. Cubic spline interpolation was used to generate fluorescence intensity values for 100 equally spaced points on each line, and pixel intensities were normalized to 1 as the maximum value.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The polar organizing protein Z, PopZ, of Caulobacter crescentus functions as a hub protein and recruits multiple regulatory proteins from the cytoplasm to the cell pole

The NMR structure of a truncated form of PopZ reveals that PopZ is disordered in solution with the exception of a small amphipathic α-helix

A partially structured Molecular Recognition Feature (MoRF) of PopZ was identified as the protein binding domain

These data reveal structural and functional insights into the role of PopZ as a bacterial hub protein

Acknowledgements

This project was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (1R01GM118792) at the National Institutes of Health and the University of New Hampshire startup funds. We would also like to thank Dr. James Aramini at CUNY Advanced Science Research Center (ASRC) for data collection.

Abbreviations:

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- PopZ

polar organizing protein Z

- IDPs

intrinsically disordered proteins

- IDD

intrinsically disordered domains

- MORF

Molecular Recognition Feature

- RDC

residual dipolar coupling

- PSVS

Protein Structure Validation Software

- CIDER

Classification of Intrinsically Disordered Ensemble Regions

- NPCR

net charge per residue

- FCR

fraction of charged residues

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Accession numbers

BMRB ID: 30773; PDB ID: 6XRY

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Yruela I, Oldfield CJ, Niklas KJ, Dunker AK (2017). Evidence for a Strong Correlation Between Transcription Factor Protein Disorder and Organismic Complexity. Genome Biol Evol. 9:1248–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Babu MM (2016). The contribution of intrinsically disordered regions to protein function, cellular complexity, and human disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 44:1185–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cumberworth A, Lamour G, Babu MM, Gsponer J (2013). Promiscuity as a functional trait: intrinsically disordered regions as central players of interactomes. Biochem J. 454:361–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Malhis N, Jacobson M, Gsponer J (2016). MoRFchibi SYSTEM: software tools for the identification of MoRFs in protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 44:W488–W93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Furth N, Aylon Y, Oren M (2018). p53 shades of Hippo. Cell Death Differ. 25:81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Grossman SR (2001). p300/CBP/p53 interaction and regulation of the p53 response. Eur J Biochem. 268:2773–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Uversky VN (2016). p53 Proteoforms and Intrinsic Disorder: An Illustration of the Protein Structure-Function Continuum Concept. Int J Mol Sci. 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nyqvist I, Andersson E, Dogan J (2019). Role of Conformational Entropy in Molecular Recognition by TAZ1 of CBP. J Phys Chem B. 123:2882–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].O’Shea C, Staby L, Bendsen SK, Tidemand FG, Redsted A, Willemoes M, et al. (2017). Structures and Short Linear Motif of Disordered Transcription Factor Regions Provide Clues to the Interactome of the Cellular Hub Protein Radical-induced Cell Death1. J Biol Chem. 292:512–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jespersen N, Estelle A, Waugh N, Davey NE, Blikstad C, Ammon YC, et al. (2019). Systematic identification of recognition motifs for the hub protein LC8. Life Sci Alliance. 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Nagulapalli M, Maji S, Dwivedi N, Dahiya P, Thakur JK (2016). Evolution of disorder in Mediator complex and its functional relevance. Nucleic Acids Res. 44:1591–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].De Biasio A, Ibanez de Opakua A, Cordeiro TN, Villate M, Merino N, Sibille N, et al. (2014). p15PAF is an intrinsically disordered protein with nonrandom structural preferences at sites of interaction with other proteins. Biophys J. 106:865–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Delaforge E, Kragelj J, Tengo L, Palencia A, Milles S, Bouvignies G, et al. (2018). Deciphering the Dynamic Interaction Profile of an Intrinsically Disordered Protein by NMR Exchange Spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 140:1148–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mollica L, Bessa LM, Hanoulle X, Jensen MR, Blackledge M, Schneider R (2016). Binding Mechanisms of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: Theory, Simulation, and Experiment. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Schneider R, Blackledge M, Jensen MR (2019). Elucidating binding mechanisms and dynamics of intrinsically disordered protein complexes using NMR spectroscopy. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 54:10–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Melo AM, Coraor J, Alpha-Cobb G, Elbaum-Garfinkle S, Nath A, Rhoades E (2016). A functional role for intrinsic disorder in the tau-tubulin complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 113:14336–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yan J, Dunker AK, Uversky VN, Kurgan L (2016). Molecular recognition features (MoRFs) in three domains of life. Mol Biosyst. 12:697–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Toto A, Camilloni C, Giri R, Brunori M, Vendruscolo M, Gianni S (2016). Molecular Recognition by Templated Folding of an Intrinsically Disordered Protein. Sci Rep. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hadži S, Mernik A, Podlipnik Č, Loris R, Lah J (2017). The Thermodynamic Basis of the Fuzzy Interaction of an Intrinsically Disordered Protein. Angewandte Chemie (International Ed in English). 56:14494–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schwarten M, Sólyom Z, Feuerstein S, Aladağ A, Hoffmann S, Willbold D, et al. (2013). Interaction of Nonstructural Protein 5A of the Hepatitis C Virus with Src Homology 3 Domains Using Noncanonical Binding Sites. Biochemistry. 52:6160–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Fuxreiter M (2019). Fold or not to fold upon binding - does it really matter? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 54:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schad E, Tompa P, Hegyi H (2011). The relationship between proteome size, structural disorder and organism complexity. Genome Biol. 12:R120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dosztányi Z, Chen J, Dunker AK, Simon I, Tompa P (2006). Disorder and sequence repeats in hub proteins and their implications for network evolution. J Proteome Res. 5:2985–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ortiz C, Natale P, Cueto L, Vicente M (2016). The keepers of the ring: regulators of FtsZ assembly. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 40:57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Schumacher MA, Huang K-H, Zeng W, Janakiraman A (2017). Structure of the Z Ring-associated Protein, ZapD, Bound to the C-terminal Domain of the Tubulin-like Protein, FtsZ, Suggests Mechanism of Z Ring Stabilization through FtsZ Cross-linking. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 292:3740–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Schumacher MA, Zeng W (2016). Structures of the nucleoid occlusion protein SlmA bound to DNA and the C-terminal domain of the cytoskeletal protein FtsZ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 113:4988–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mignolet J, Panis G, Viollier PH (2018). More than a Tad: spatiotemporal control of Caulobacter pili. Curr Opin Microbiol. 42:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ardissone S, Viollier PH (2015). Interplay between flagellation and cell cycle control in Caulobacter. Curr Opin Microbiol. 28:83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kazmierczak BI, Schniederberend M, Jain R (2015). Cross-regulation of Pseudomonas motility systems: the intimate relationship between flagella, pili and virulence. Curr Opin Microbiol. 28:78–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ringgaard S, Yang W, Alvarado A, Schirner K, Briegel A (2018). Chemotaxis arrays in Vibrio species and their intracellular positioning by the ParC/ParP system. J Bacteriol. 200:e00793–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ramachandran R, Jha J, Chattoraj DK (2014). Chromosome segregation in Vibrio cholerae. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 24:360–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kloosterman TG, Lenarcic R, Willis CR, Roberts DM, Hamoen LW, Errington J, et al. (2016). Complex polar machinery required for proper chromosome segregation in vegetative and sporulating cells of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 101:333–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Werner JN, Chen EY, Guberman JM, Zippilli AR, Irgon JJ, Gitai Z (2009). Quantitative genome-scale analysis of protein localization in an asymmetric bacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106:7858–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Grangeon R, Zupan J, Jeon Y, Zambryski PC (2017). Loss of PopZ(At) activity in Agrobacterium tumefaciens by Deletion or Depletion Leads to Multiple Growth Poles, Minicells, and Growth Defects. Mbio. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Pfeiffer D, Toro-Nahuelpan M, Bramkamp M, Plitzko JM, Schuler D (2019). The Polar Organizing Protein PopZ Is Fundamental for Proper Cell Division and Segregation of Cellular Content in Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. Mbio. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Berge M, Viollier PH (2018). End-in-Sight: Cell Polarization by the Polygamic Organizer PopZ. Trends Microbiol. 26:363–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bowman GR, Comolli LR, Zhu J, Eckart M, Koenig M, Downing KH, et al. (2008). A polymeric protein anchors the chromosomal origin/ParB complex at a bacterial cell pole. Cell. 134:945–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ebersbach G, Briegel A, Jensen GJ, Jacobs-Wagner C (2008). A self-associating protein critical for chromosome attachment, division, and polar organization in caulobacter. Cell. 134:956–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Bowman GR, Perez AM, Ptacin JL, Ighodaro E, Folta-Stogniew E, Comolli LR, et al. (2013). Oligomerization and higher-order assembly contribute to sub-cellular localization of a bacterial scaffold. Mol Microbiol. 90:776–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lim HC, Bernhardt TG (2019). A PopZ-linked apical recruitment assay for studying protein-protein interactions in the bacterial cell envelope. Mol Microbiol. 112:1757–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Holmes JA, Follett SE, Wang H, Meadows CP, Varga K, Bowman GR (2016). Caulobacter PopZ forms an intrinsically disordered hub in organizing bacterial cell poles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113:12490–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Berge M, Campagne S, Mignolet J, Holden S, Theraulaz L, Manley S, et al. (2016). Modularity and determinants of a (bi-)polarization control system from free-living and obligate intracellular bacteria. Elife. 5:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Perez AM, Mann TH, Lasker K, Ahrens DG, Eckart MR, Shapiro L (2017). A Localized Complex of Two Protein Oligomers Controls the Orientation of Cell Polarity. Mbio. 8:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wang HB, Bowman GR (2019). SpbR overproduction reveals the importance of proteolytic degradation for cell pole development and chromosome segregation in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol Microbiol. 111:1700–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Duerig A, Abel S, Folcher M, Nicollier M, Schwede T, Amiot N, et al. (2009). Second messenger-mediated spatiotemporal control of protein degradation regulates bacterial cell cycle progression. Genes Dev. 23:93–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Bowman GR, Comolli LR, Gaietta GM, Fero M, Hong S-H, Jones Y, et al. (2010). Caulobacter PopZ forms a polar subdomain dictating sequential changes in pole composition and function. Mol Microbiol. 76:173–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A (1995). NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 6:277–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Lee W, Tonelli M, Markley JL (2015). NMRFAM-SPARKY: enhanced software for biomolecular NMR spectroscopy. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 31:1325–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Yao J, Dyson HJ, Wright PE (1997). Chemical shift dispersion and secondary structure prediction in unfolded and partly folded proteins. FEBS Lett. 419:285–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Schubert M, Labudde D, Oschkinat H, Schmieder P (2002). A software tool for the prediction of Xaa-Pro peptide bond conformations in proteins based on 13C chemical shift statistics. J Biomol NMR. 24:149–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Wishart DS, Sykes BD (1994). The 13C Chemical-Shift Index: A simple method for the identification of protein secondary structure using 13C chemical-shift data. J Biomol NMR. 4:171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Marsh JA, Singh VK, Jia Z, Forman-Kay JD (2006). Sensitivity of secondary structure propensities to sequence differences between alpha- and gamma-synuclein: Implications for fibrillation. Protein Sci. 15:2795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lee W, Stark JL, Markley JL (2014). PONDEROSA-C/S: client–server based software package for automated protein 3D structure determination. J Biomol NMR. 60:73–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Mohana-Borges R, Goto NK, Kroon GJA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE (2004). Structural characterization of unfolded states of apomyoglobin using residual dipolar couplings. J Mol Biol. 340:1131–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bhattacharya A, Tejero R, Montelione GT (2007). Evaluating protein structures determined by structural genomics consortia. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 66:778–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Das RK, Pappu RV (2013). Conformations of intrinsically disordered proteins are influenced by linear sequence distributions of oppositely charged residues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110:13392–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Martin EW, Holehouse AS, Grace CR, Hughes A, Pappu RV, Mittag T (2016). Sequence Determinants of the Conformational Properties of an Intrinsically Disordered Protein Prior to and upon Multisite Phosphorylation. J Am Chem Soc. 138:15323–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2r3pre, Schrödinger, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- [59].McGrath PT, Iniesta AA, Ryan KR, Shapiro L, McAdams HH (2006). A dynamically localized protease complex and a polar specificity factor control a cell cycle master regulator. Cell. 124:535–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Joshi KK, Berge M, Radhakrishnan SK, Viollier PH, Chien P (2015). An Adaptor Hierarchy Regulates Proteolysis during a Bacterial Cell Cycle. Cell. 163:419–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Joshi KK, Battle CM, Chien P (2018). Polar Localization Hub Protein PopZ Restrains Adaptor-Dependent ClpXP Proteolysis in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Taylor JA, Wilbur JD, Smith SC, Ryan KR (2009). Mutations that alter RcdA surface residues decouple protein localization and CtrA proteolysis in Caulobacter crescentus. J Mol Biol. 394:46–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Williamson MP (2013). Using chemical shift perturbation to characterise ligand binding. Progress In Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 73:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Xu HB, Ye H, Osman NE, Sadler K, Won EY, Chi SW, et al. (2009). The MDM2-Binding Region in the Transactivation Domain of p53 Also Acts as a Bcl-X-L-Binding Motif. Biochemistry. 48:12159–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kriwacki RW, Hengst L, Tennant L, Reed SI, Wright PE (1996). Structural studies of p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 in the free and Cdk2-bound state: conformational disorder mediates binding diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 93:11504–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Ptacin JL, Gahlmann A, Bowman GR, Perez AM, von Diezmann ARS, Eckart MR, et al. (2014). Bacterial scaffold directs pole-specific centromere segregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 111:E2046–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Blair JA, Xu QP, Childers WS, Mathews II, Kern JW, Eckart M, et al. (2013). Branched Signal Wiring of an Essential Bacterial Cell-Cycle Phosphotransfer Protein. Structure. 21:1590–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Tsokos CG, Perchuk BS, Laub MT (2011). A dynamic complex of signaling proteins uses polar localization to regulate cell-fate asymmetry in Caulobacter crescentus. Dev Cell. 20:329–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Iniesta AA, McGrath PT, Reisenauer A, McAdams HH, Shapiro L (2006). A phospho-signaling pathway controls the localization and activity of a protease complex critical for bacterial cell cycle progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 103:10935–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Lasker K, von Diezmann L, Zhou X, Ahrens DG, Mann TH, Moerner WE, et al. (2020). Selective sequestration of signalling proteins in a membraneless organelle reinforces the spatial regulation of asymmetry in Caulobacter crescentus. Nat Microbiol. 5:418–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Lori C, Ozaki S, Steiner S, Bohm R, Abel S, Dubey BN, et al. (2015). Cyclic di-GMP acts as a cell cycle oscillator to drive chromosome replication. Nature. 523:236–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Abel S, Chien P, Wassmann P, Schirmer T, Kaever V, Laub MT, et al. (2011). Regulatory cohesion of cell cycle and cell differentiation through interlinked phosphorylation and second messenger networks. Mol Cell. 43:550–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Dahal L, Shammas SL, Clarke J (2017). Phosphorylation of the IDP KID Modulates Affinity for KIX by Increasing the Lifetime of the Complex. Biophys J. 113:2706–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Yadahalli S, Neira JL, Johnson CM, Tan YS, Rowling PJE, Chattopadhyay A, et al. (2019). Kinetic and thermodynamic effects of phosphorylation on p53 binding to MDM2. Sci Rep. 9:693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Sharma S, Cermakova K, De Rijck J, Demeulemeester J, Fabry M, El Ashkar S, et al. (2018). Affinity switching of the LEDGF/p75 IBD interactome is governed by kinase-dependent phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 115:E7053–E62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Kussie PH, Gorina S, Marechal V, Elenbaas B, Moreau J, Levine AJ, et al. (1996). Structure of the MDM2 oncoprotein bound to the p53 tumor suppressor transactivation domain. Science. 274:948–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Follis AV, Chipuk JE, Fisher JC, Yun M-K, Grace CR, Nourse A, et al. (2013). PUMA binding induces partial unfolding within BCL-xL to disrupt p53 binding and promote apoptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 9:163–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Day CL, Smits C, Fan FC, Lee EF, Fairlie WD, Hinds MG (2008). Structure of the BH3 domains from the p53-inducible BH3-only proteins Noxa and Puma in complex with Mcl-1. J Mol Biol. 380:958–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Zor T, De Guzman RN, Dyson HJ, Wright PE (2004). Solution structure of the KIX domain of CBP bound to the transactivation domain of c-Myb. J Mol Biol. 337:521–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Liu X, Chen J, Chen J (2019). Residual Structure Accelerates Binding of Intrinsically Disordered ACTR by Promoting Efficient Folding upon Encounter. J Mol Biol. 431:422–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Giri R, Morrone A, Toto A, Brunori M, Gianni S (2013). Structure of the transition state for the binding of c-Myb and KIX highlights an unexpected order for a disordered system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110:14942–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Bienkiewicz EA, Adkins JN, Lumb KJ (2002). Functional consequences of preorganized helical structure in the intrinsically disordered cell-cycle inhibitor p27(Kip1). Biochemistry. 41:752–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Mosyak L, Zhang Y, Glasfeld E, Haney S, Stahl M, Seehra J, et al. (2000). The bacterial cell-division protein ZipA and its interaction with an FtsZ fragment revealed by X-ray crystallography. The EMBO journal. 19:3179–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Hsu W-L, Oldfield CJ, Xue B, Meng J, Huang F, Romero P, et al. (2013). Exploring the binding diversity of intrinsically disordered proteins involved in one-to-many binding. Protein Science: A Publication of the Protein Society. 22:258–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Karlsson E, Andersson E, Dogan J, Gianni S, Jemth P, Camilloni C (2019). A structurally heterogeneous transition state underlies coupled binding and folding of disordered proteins. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 294:1230–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Arai M, Sugase K, Dyson HJ, Wright PE (2015). Conformational propensities of intrinsically disordered proteins influence the mechanism of binding and folding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 112:9614–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Lacy ER, Filippov I, Lewis WS, Otieno S, Xiao L, Weiss S, et al. (2004). p27 binds cyclin-CDK complexes through a sequential mechanism involving binding-induced protein folding. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 11:358–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Laloux G, Jacobs-Wagner C (2013). Spatiotemporal control of PopZ localization through cell cycle-coupled multimerization. The Journal of cell biology. 201:827–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Warfield L, Tuttle LM, Pacheco D, Klevit RE, Hahn S (2014). A sequence-specific transcription activator motif and powerful synthetic variants that bind Mediator using a fuzzy protein interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 111:E3506–E13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Rogers JM, Oleinikovas V, Shammas SL, Wong CT, De Sancho D, Baker CM, et al. (2014). Interplay between partner and ligand facilitates the folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 111:15420–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Tuttle LM, Pacheco D, Warfield L, Luo J, Ranish J, Hahn S, et al. (2018). Gcn4-Mediator Specificity Is Mediated by a Large and Dynamic Fuzzy Protein-Protein Complex. Cell Rep. 22:3251–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Dogan J, Mu X, Engstrom A, Jemth P (2013). The transition state structure for coupled binding and folding of disordered protein domains. Sci Rep. 3:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Crabtree MD, Borcherds W, Poosapati A, Shammas SL, Daughdrill GW, Clarke J (2017). Conserved Helix-Flanking Prolines Modulate Intrinsically Disordered Protein:Target Affinity by Altering the Lifetime of the Bound Complex. Biochemistry. 56:2379–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Shoemaker BA, Portman JJ, Wolynes PG (2000). Speeding molecular recognition by using the folding funnel: the fly-casting mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 97:8868–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Harmon TS, Holehouse AS, Rosen MK, Pappu RV (2017). Intrinsically disordered linkers determine the interplay between phase separation and gelation in multivalent proteins. eLife. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Kribelbauer JF, Rastogi C, Bussemaker HJ, Mann RS (2019). Low-Affinity Binding Sites and the Transcription Factor Specificity Paradox in Eukaryotes. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 35:357–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Bahrami A, Assadi AH, Markley JL, Eghbalnia HR (2009). Probabilistic Interaction Network of Evidence Algorithm and its Application to Complete Labeling of Peak Lists from Protein NMR Spectroscopy. PLOS Computational Biology. 5:e1000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Lee W, Westler WM, Bahrami A, Eghbalnia HR, Markley JL (2009). PINE-SPARKY: graphical interface for evaluating automated probabilistic peak assignments in protein NMR spectroscopy. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 25:2085–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Shen Y, Bax A (2013). Protein backbone and sidechain torsion angles predicted from NMR chemical shifts using artificial neural networks. J Biomol NMR. 56:227–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Louhivuori M, Pääkkönen K, Fredriksson K, Permi P, Lounila J, Annila A (2003). On the Origin of Residual Dipolar Couplings from Denatured Proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 125:15647–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Lee W, Tonelli M, Markley JL (2015). NMRFAM-SPARKY: enhanced software for biomolecular NMR spectroscopy. Bioinformatics. 31:1325–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Schwieters CD, Bermejo GA, Clore GM (2018). Xplor-NIH for molecular structure determination from NMR and other data sources. Protein Sci. 27:26–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Nederveen AJ, Doreleijers JF, Vranken W, Miller Z, Spronk CA, Nabuurs SB, et al. (2005). RECOORD: a recalculated coordinate database of 500+ proteins from the PDB using restraints from the BioMagResBank. Proteins. 59:662–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.