Abstract

Telomeres are long (TTAGGG)n nucleotide repeats and an associated protein complex located at the end of the chromosomes. They shorten with every cell division and, thus are markers for cellular aging, senescence, and replicative capacity. Telomere dysfunction is linked to several bone marrow disorders, including dyskeratosis congenita, aplastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and hematopoietic malignancies. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) provides an opportunity in which to study telomere dynamics in a high cell proliferative environment. Rapid telomere shortening of donor cells occurs in the recipient shortly after HSCT; the degree of telomere attrition does not appear to differ by graft source. As expected, telomeres are longer in recipients of grafts with longer telomeres (e.g., cord blood). Telomere attrition may play a role in, or be a marker of, long term outcome after HSCT, but these data are limited. In this review, we discuss telomere biology in normal and abnormal hematopoiesis, including HSCT.

Keywords: Telomeres, bone marrow disorders, hematopoietic stem cell transplant

Introduction

The replicative capacity of human cells is limited by the inability of DNA polymerase to fully replicate the linear ends of the DNA1, a phenomenon called the “end-replication problem”. The physiologic solution to the end-replication problem was provided with the discovery of telomeres, the molecular structures at chromosome ends, and their maintenance enzyme, telomerase2. Studies of telomere biology now range from a detailed understanding of telomeric structure, function, and regulatory mechanisms, to evaluating their role in aging, and human disease susceptibility, such as aplastic anemia, pulmonary fibrosis, heart disease, chronic inflammatory conditions, and cancer.

Telomeres shorten with successive cell division and, when a critical length is reached, cellular senescence is triggered. During the first weeks after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), the transplanted stem cells undergo extensive cell division to reconstitute the recipients’ new hematopoietic cells; this process has the potential to cause significant telomere attrition. In this review, we evaluate the 1) relationship between normal telomere biology and cell growth and maturation in the hematopoietic system, 2) bone marrow disorders associated with telomere biology abnormalities, and 3) telomere dynamics after HSCT, and their potential role in transplant outcomes. Finally, we discuss the clinical implications and directions for research on the role of telomere biology in HSCT.

Telomere Biology in Hematopoietic Cells

Human Telomeres:

Telomeres consist of long (TTAGGG)n nucleotide repeats and an associated protein complex located at the end of the chromosomes. They are essential for maintaining chromosomal integrity by preventing chromosome end-to-end fusion3. Telomeres shorten with every cell division4, and therefore their length is a marker for cell aging, senescence and, replicative capacity. Telomere erosion in human cells represents a unique form of DNA damage, in which repair mechanisms are very limited5. When telomeres become critically short, cells become senescent and ultimately die. Alternatively, critically short telomeres may bypass senescence and continue to divide despite the presence of genetic instability. This is often associated with alterations in the p53 or Rb pathways, as observed in cancer cells6. Human studies show that telomeres shorten with age in almost all tissues, with the exception of the brain and heart (reviewed in7). Longitudinal studies suggest a positive relationship between the rate of telomere attrition and the individual’s baseline telomere length8,9; individuals with the longest telomeres at baseline appear to have the highest attrition rate overtime. However, the mechanism of this differential telomere length regulation is unknown.

Telomeres are maintained mainly by the telomerase ribonucleoprotein complex and the shelterin protein complex. The catalytic unit of telomerase consists of an RNA template (TERC), a reverse transcriptase protein (TERT), and the dyskerin protein complex. Telomerase is expressed in embryonic and adult stem cells, and in highly-proliferative cells such as germline cells, skin, intestine, and bone marrow10,11, but not in most other somatic cells12. Approximately 80 to 90% of cancer cells maintain telomere length by over-expressing telomerase13. However, a subset of cancers elongate telomeres through an alternative lengthening mechanisms (reviewed in14). The shelterin complex consists of six protein subunits: telomeric repeat-binding factors 1, and 2 (gene names TERF1 and TERF2), TRF1-interacting nuclear factor 2 (TINF2), TERF2-interacting protein 1 (TERF2IP), TIN2-interacting protein 1 (ACD), and protection of telomeres (POT1)15. Shelterin is essential for normal telomere maintenance and function by inhibiting telomeric DNA damage response, regulating telomerase, and inhibiting telomeric homologous recombination16.

Human telomere length varies significantly between individuals. In human somatic cells, telomere length ranges between 2–15 kilobases (Kb)17, and is often longer in females than males18. In addition, intra-individual tissue differences in telomere length have been observed19,20. However, within an individual, telomere length appears to be highly-correlated (i.e., individuals with longer telomeres in one tissue tend to have longer telomeres in other tissues)21–25.

Several methods are available to measure telomere length (reviewed in26,27). Terminal restriction fragment (TRF) measurement, based on Southern blots, is considered the gold standard. Other methods include: flow-FISH, which measures telomeres in leukocyte subsets; quantitative PCR (Q-PCR), which measures relative telomere length in extracted DNA as a ratio of telomere repeat copy number (T) to single gene copy number (S); and single telomere length analysis (STELA), a PCR method that measures chromosome-specific telomere length.

Telomere Dynamics in Hematopoietic Cells:

Proper telomere maintenance in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is important because of the need for continuous replication of blood cells throughout life. Telomeres shorten rapidly after birth and during childhood. Early studies demonstrated the presence of longer telomeres in umbilical cord HSCs (CD34+CD38−) than in the same cell population in adult bone marrow28 or in peripheral blood29. Telomere shortening in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) during the first 3 years of life was found to be more than fourfold higher than that observed in adults during a period of 3 years30. The profound rate of telomere attrition in the first years of life might reflect the expected rapid replication and expansion of hematopoietic stem cells early in life, followed by a decline in the rate of their replication thereafter31.

The presence of longer telomeres in umbilical cord blood (UCB) was not limited to stem cells, but was also observed in mature hematopoietic cells, including T-cells, B-cells, NK-cells, and granulocytes, compared with their adult counterparts29. Additional studies suggest that lymphocytes have longer telomeres than granulocytes at birth, followed by a high attrition rate in the first year for both cell types. More prominent telomere loss was observed in lymphocytes after the first year of life, resulting in shorter lymphocyte telomeres (as measured by flow-FISH) in old age (>60 years) when compared with that of granulocytes31. Telomere length differences between lymphocyte subsets have also been reported: adult peripheral blood B-lymphocytes were shown to have longer telomeres than T-lymphocytes32. This was thought to be due to differences in the rate of cell division between B and T cells33. In addition, CD8+ cells appear to have longer telomeres than CD4+ cells34.

In support of the replicative senescence theory, longer telomeres were found in hematopoietic progenitor cells (CD34+) than in subsets of mature cells (naïve and memory CD4+ and CD8+, and granulocytes). Both CD4+ and CD8+ naïve T-cells have longer telomeres than corresponding memory cells35, or effector cells34. The longer telomeres in naïve cells might be the result of their higher replicative needs. However, one study found longer telomeres in memory B-cells than naïve cells32, a finding that still requires explanation. Overall, telomere length appears to be related to the replicative history of hematopoietic cells and their progenitors but potentially important deviations from this pattern have yet to be explained. Future studies geared toward understanding telomere biology in HSCs subsets will be important in understanding HSC development and their lifespan.

Telomere Biology and Bone Marrow Related Disorders

Dyskeratosis Congenita

The discovery that mutations in dyskerin (DKC1) caused X-linked recessive dyskeratosis congenita (DC)36, and that these mutations resulted in abnormally short telomeres37, were the springboard for studies of telomere biology in inherited disorders. DC is a complex disorder, characterized by the diagnostic triad of nail dystrophy, lacy reticular pigmentation of the neck and upper chest, and oral leukoplakia38. Patients are at very high risk of bone marrow failure (BMF), myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML). By age 30 years, 80–90% of DC patients develop severe aplastic anemia that does not respond to immunosuppressive medications39; this is the main cause of death in those patients40. Patients with DC are also at high risk of pulmonary fibrosis41, and cancer (11-fold higher than the general population)42.

DC is genetically heterogeneous, including X-linked recessive, autosomal dominant, and autosomal recessive forms. Approximately 25% of patients with DC have the X-linked form with mutations in DKC1. DC is also caused by inherited mutations in other critical components of the telomere maintenance pathway, including TERC (autosomal dominant), TERT (autosomal dominant and recessive), TINF2 (autosomal dominant), NOP10 and NHP2 (both autosomal recessive) and, the most recently discovered autosomal recessive gene, TCAB143. A mutation in one of these seven genes is identified in about 60% of patients with classic DC. Although all the DC genes have not yet been discovered, it is important to note that all patients with DC have very short telomeres for their age. Telomere length measurement in leukocyte subsets by flow cytometry with fluorescent in situ hybridization (flow-FISH) is sensitive and specific in distinguishing patients with DC from unaffected family members, and from patients with other inherited BMF syndromes44. In another study using a different flow-FISH technique which determined relative telomere length in PBMC compared with a control cell line, all patients with DC had very short telomeres, but approximately 30% of patients with other BMF disorders also had telomere length ≤ 1st percentile45. Clinical testing of telomere length by flow-FISH is now recommended for all patients with BMF, if testing for Fanconi anemia is negative44,46.

Other Bone Marrow Failure Disorders:

Several studies have evaluated telomeres in patients with other inherited BMF syndromes e.g., Fanconi anemia, Diamond-Blackfan anemia, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria47. These studies suggest that some of these patients have shorter than average telomeres, but they are not as short as the very short telomeres which characterize DC. TL abnormalities in BMF syndromes other than DC have been observed primarily in granulocyte telomeres44, an observation that might reflect the rapid turnover of hematopoietic cells in response to the bone marrow stress associated with marrow aplasia. Alternatively, the shorter telomeres in these disorders could also be due (in part) to their underlying genetic defect in DNA damage repair, particularly in Fanconi anemia and Shwachman-Diamond syndrome48.

Similarly, patients with acquired BMF (i.e., aplastic anemia) also appear to have shorter telomeres than controls49, but not as short as those observed in DC45. Patients diagnosed with acquired BMF who have short telomeres are at high risk of relapse, clonal evolution, or mortality50. The short telomeres in acquired BMF were believed to be secondary to the accelerated proliferation of the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in response to marrow hypoplasia49. However, the presence of germline TERT or TERC mutations in approximately 10% of those patients48 suggests the presence of occult DC cases among patients diagnosed with acquired BMF. Making this distinction is complicated by the observed phenotypic variability in DC, and made even more challenging because the causative gene is still unknown in around 40% of patients with DC. Incorporating telomere length measurement in the initial diagnostic studies for patients with acquired BMF is important, particularly because treatment options and outcomes are different for patients with inherited BMF (occult DC) than for those with truly acquired disease39.

Myelodysplastic Syndromes

MDS are heterogeneous group of BMF disorders that are characterized by abnormal hematopoiesis, cellular dysplasia, and an increased risk of AML51. Patients with inherited or apparently acquired BMF are also at high risk of developing MDS42. MDS may be an intermediate stage between BMF and AML in these patients. In general, patients with MDS have shorter telomeres than healthy controls52. However, considerable variation in telomere length has been observed between patients with MDS53. The presence of TERT or TERC mutations in some patients with familial MDS, in the absence of known clinical features of DC, further illustrates the possible presence of occult DC in these individuals54. Germline mutations in TERT have been also reported in a subset of patients with AML55 who do not meet clinical criteria for DC, again, suggestive of a clinical spectrum of diseases related to mutations in telomere biology genes.

Telomere dynamics in MDS may also be associated with disease characteristics and prognosis. Specifically, patients with isolated monosomy 7 were shown to have longer telomeres than patients with other cytogenetic subtypes, an observation that may be a consequence of telomerase over-expression in that patient subgroup52. Another study showed that MDS patients with the shortest telomeres have low hemoglobin concentrations, high percentages of marrow blasts, and a high incidence of cytogenetic abnormalities56. Of note, telomerase activity did not correlate with clinical or prognostic parameters53,57.

A link between short telomeres in MDS and leukemic transformation was suggested in two studies56,58. However, in a study comparing telomere length and telomerase expression in MDS patients who did or did not progress to AML53, short telomeres were observed in a similar proportion of patients in both groups. It seems that telomerase over-expression may be the driving force; this was mainly noted in patients with MDS who progressed to AML. MDS may be characterized by an early defect in telomere maintenance mechanisms, followed by a later telomerase over-expression which may be associated with malignant transformation59.

Hematopoietic Malignancies

Telomere abnormalities have also been noted in patients with hematological malignancies47,59–61. In most of the reviewed studies, telomere length and/or telomerase activity were measured in blood or bone marrow cells in patients’ samples and compared with healthy individuals; consequently, the patient cells analyzed were often a mix of malignant and benign cells. In general, most patients with acute or chronic leukemia have short telomeres and high telomerase expression, with some variation by disease subtype. In a study comparing telomere length and telomerase activity in hematopoietic progenitor cells (CD34+) collected from normal individuals and from patients with different types of acute and chronic leukemia, short telomeres were observed in AML and chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) specimens, but not in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). On the other hand, telomerase activity in AML specimens was significantly higher than that of the controls, a moderate elevation was observed in CML, and no change in CLL62; this may be a consequence of telomere length variation in these diseases. In a recent study that directly compared telomere regulation in various acute leukemias, telomeres were the shortest in B-ALL, followed by T-ALL and then AML; short telomeres were also associated with higher telomerase expression in these patients63. In CML, a few studies compared malignant hematopoietic stem cells (BCR-ABL CD34+) with benign stem cells64,65 and confirmed the previously-observed telomeric dysregulation in the form of short telomeres and elevated telomerase activity.

Telomere biology in hematopoietic malignancies has been also associated with clinical characteristics and outcome. Higher telomerase levels have been associated with relapse, disease progression, and worse survival in adults with acute or chronic leukemia66–68, but not in children with ALL69. In CML, telomere shortening has been observed in serial peripheral blood samples collected from patients who progressed from chronic to blast phase70, and it was associated with faster time to progression in another study71. In addition, patients with CML in blast phase were reported to have significantly higher telomerase activity compared with those in the chronic phase72. High levels of telomerase in CML blast phase was also associated with additional cytogenetic changes and microsatellite abnormalities, indicating the development of genomic instability73. It is important to note that cytotoxic chemotherapy can shorten telomeres, mostly because of the hematopoietic cell regeneration required for recovery from drug-induced marrow suppression, while the use of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor, imatinib, in patients with CML was found to elongate previously shortened peripheral blood telomeres. This phenomenon was suggested to be due to the shift from Philadelphia chromosome positive (Ph+) to Ph- cells in patients’ blood in response to treatment74. A subsequent study of the effect of imatinib on telomere length found that it significantly down-regulatedD telomerase activity in primary leukemic cells through a direct action on TERT transcription75.

Role of Telomeres in HSCT

HSCT has become the treatment of choice for many hematologic malignancies, as well as other inherited and acquired bone marrow and immune system disorders. Annually, more than 30,000 autologous, and 15,000 allogeneic transplantation are performed worldwide76. Details about HSCT history, methods, early and late complications, as well as outcomes in selected diseases were reviewed in76. HSCT recipients receive a preparative regimen of chemotherapy with or without irradiation to eradicate malignant clone and/or induce immunosuppression prior to HSCT which permits engraftment. HSC preparations are then infused into the transplant recipient. The main sources of stem cells in HSCT are bone marrow, peripheral blood, and UCB. The infused stem cells undergo acute and rapid replication and proliferation (at much greater than normal rates) to reconstitute the recipient’s hematopoietic system. In most cases, peripheral blood cell counts and bone marrow cellularity normalize within 2–6 months after HSCT77. However, donor hematopoietic progenitor cell function remains deficient in the recipient for several years after transplantation78,79. Specifically, bone marrow CD34 cells from transplant recipients (at a median of 3 years post-transplant) have lower colony scores and cytokine concentrations in erythroid burst-forming units (BFU-Es), erythroid and myeloid colony forming units (CFU-Es), and colony forming units-granulocyte macrophage (CFU-GM)78.

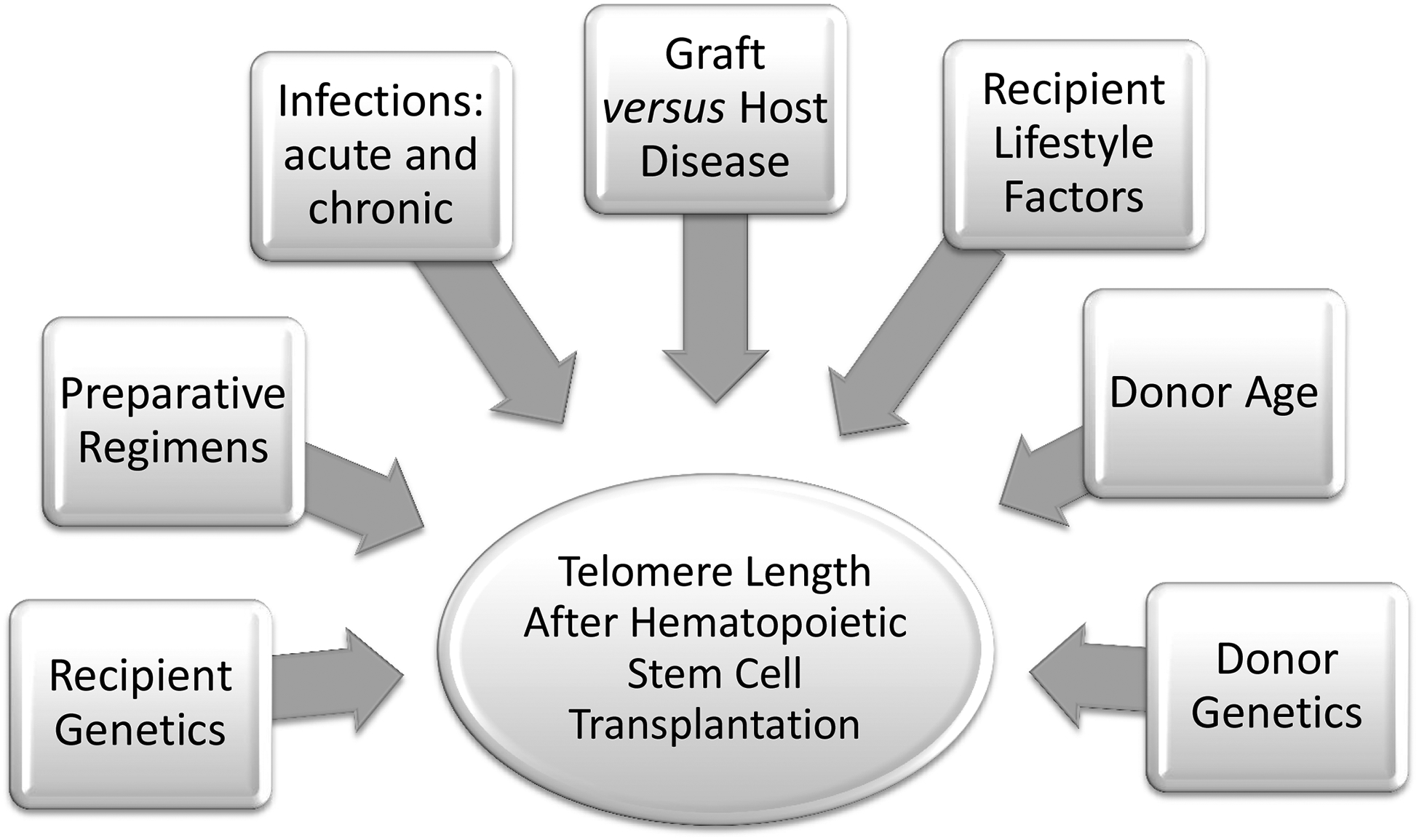

Proper telomere function is important in HSCT because telomeres shorten with each cell division; the donor HSCs undergo massive proliferation after infusion in order to achieve engraftment (Figure 1). The interplay of cell division and telomere shortening thus has potential to affect clinical outcome. A limited number of studies have evaluated the short and long-term telomere length dynamics after HSCT by comparing the donors’ blood or marrow telomeres to those within the cells transplanted into the recipients. In addition, some studies have evaluated the effect of telomere attrition on hematopoietic reconstitution, or on factors contributing to post-transplant telomere attrition.

Figure 1:

A model for telomere dynamics and outcomes after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Relative telomere length is shown on the Y-axis and relative time is on the X-axis. After infusion of donor hematopoietic stem cells (HSC), rapid telomere length attrition occurs then levels off to relatively normal, age-related rates. Critically short telomeres may occur earlier in HSCT recipients.

Telomere Dynamics After HSCT

After HSCT, telomeres in the recipient are typically shorter than in their matched donors80. This pattern has been reported in both autologous and allogeneic HSCT, suggesting that this effect is due to rapid HSC division on telomere length. In autologous transplantation, telomere shortening was most prominent in elderly recipients who had undergone several courses of pre-HSCT chemotherapy. This suggests that pre-transplant therapy which affects the bone marrow stroma and its micro-environment in the host may play a role in post-transplant telomere length regulation. In recipients of allogeneic transplantation, telomeres were shorter in those who received HSC from elderly donors than in those recipients who had younger donors81. This primarily reflects the fact that older donors have shorter telomeres because of the normal age-related telomere attrition in healthy individuals. Of note, one study suggested that the use of nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens did not prevent post-transplant telomere shortening in the recipient82.

Data from longitudinal studies with repeated telomere length measurements of the same individual83,84 showed rapid telomere length attrition in the first 12 months after HSCT in recipients of bone marrow grafts. This is followed by telomere shortening rates that were similar to the expected age-related decline seen in controls. The reported annual rates of telomere shortening vary based on the study and method of telomere length measurement. It has been estimated that post-HSCT telomere attrition rate in the first year is 537 ± 155 base pairs (bp), compared with an annual attrition rate of 221 ± 81 bp thereafter84. Looking more closely, Thornley and colleagues77 reported significantly shorter telomeres in the recipients at engraftment, 6, and 12 months post-transplant compared with donor telomere length before bone marrow harvest or after mobilized peripheral blood collection. Evaluation of the changes in recipients’ telomere length over the same time period did not find significant telomere attrition. This suggests that the maximum telomere attrition occurs within weeks after HSC infusion. These studies illustrate the utility of telomere length as a biomarker of the excessive cellular replication which occurs in order to achieve engraftment.

A similar, but less profound, pattern of post-HSCT telomere shortening has been observed in recipients of peripheral blood stem cell transplants (PBSCT). Compared with donors, the average neutrophil telomere shortening for bone marrow transplant (BMT) recipients was 321 ± 90 base pairs (bp) vs. 296 ± 127 bp for PBSCT recipients. A similar pattern was observed for telomere shortening in T cells (289 ± 133 bp for BMT recipients’ vs. 113 ± 379 bp for PBSCT recipients)84. At one year after transplantation, and in contrast to bone marrow stem cell transplantation, telomere length in PBSCT recipients was comparable to that of the donors in one study85. This observation needs to be confirmed. If true, this could be due to the presence of a higher number of HSC in PBSCs, with fewer cell divisions required to achieve engraftment86,87. However, the correlation between the number of infused HSCs and recipients’ telomere length was inconsistent between several studies81,84,88.

UCB is an important source of stem cells and their use in HSCT is growing. Telomeres in UCB cells are longer than those in other HSCT sources because they are acquired at birth, when telomeres are the longest and normal age-associated telomere attrition has not yet occurred. One study showed that the degree of post-transplant telomere attrition in UCB and PBSCT recipients at one-year was comparable (difference between donor and recipients TL ranged between 0.3–0.6 Kb in UCB, and 0.4–0.7 Kb in PBSC). As expected, the absolute TL was longer for UCB HSCT recipients89–91. In support of this finding, Ruella and colleagues reported that in both autologous and allogeneic transplants, post-transplant (median= 14 months) bone marrow telomere length reflected that of the grafted cells92.

It is conceivable that activation of telomerase may help in controlling post-transplant telomere attrition. For example, antigen stimulation of T cells derived from serially transplanted HSCs resulted in telomere elongation in wild type but not in telomerase deficient mice, suggesting that telomere elongation after antigen stimulation is telomerase-dependent93. A subsequent study showed that94 serially transplanted HSCs from telomerase deficient mice have lower replicative capacity (rounds to exhaustion=2 vs. 4 or more), and higher rate of telomere attrition (2-fold increase), when compared with that transplanted from wild type.

Studies of telomere length changes in long-term HSCT survivors are important in understanding the replicative capacity of the transplanted HSCs. This will become more important as transplant recipients survive for longer because there could be late graft failures if the donor cells have reduced replicative capacity due to shorter telomeres. Baerlocher and colleagues95 compared post-transplant peripheral blood telomere length in leukocyte subsets of long term HSCT survivors and their donors at the same time intervals and found that the recipients’ telomeres were shorter in all leukocyte subsets studied (granulocytes, naïve and memory T cells, B cells and natural killer cells). In the same study, shorter telomeres were associated with the presence of chronic graft versus host disease (GvHD) and receiving graft from a female donor. On the other hand, a small, but not statistically significant, telomere length difference between long term transplant survivors (median follow up was 18 years) and their donors was observed in another study96. The inconsistent results between the two studies might be related to the differences in recipient and donor factors, such as the donors’ gender and the presence of GvHD in the recipients.

While the literature on telomere dynamics after HSCT is growing, it is important to note that most of the available studies were cross-sectional in design, and included a very small number of participants. Survival bias may be of concern in studies that evaluated telomere length in long-term survivors. It is possible that transplant recipients with the shortest telomeres died early after transplantation and therefore were not represented in most of the available studies. A more comprehensive investigation is needed to answer some of the unsolved questions.

Factors Influencing Telomere Dynamics After HSCT

Telomere Dysfunction in the Recipient:

TERC knockout mice (TERC−/−) provide an experimental model in which to study the involvement of telomere biology in aging, cancer development, cardiovascular diseases and others. In general, TERC−/− mice lack detectable telomerase activity because they lack the telomerase RNA template, TERC. However, variability across generations has been noted. Telomere length in these mice shortens in subsequent generations by approximately 5 Kb. Phenotypic abnormalities do not appear until the 3rd generation97, most likely because mice telomeres are very long compared with humans (40–80 Kb vs. 10–15 Kb, respectively)98, and knocking out telomerase appears to cause gradual telomere shortening, at least in mice. Aging TERC−/− mice showed impaired bone marrow stromal cell function, with altered cytokine expression, that contribute to impaired engraftment of transplanted wild-type HSCs99. Additionally, HSCT did not rescue thymic function in these mice100. Taken together, these observations suggest a role of telomere biology on HSCT outcomes. Studies involving patients with DC and related telomere biology disorders provide a very important opportunity to better understand these interactions.

BMF is very common in patients with DC, and HSCT is the only option for cure. Large, prospective studies of HSCT outcomes in patients with DC have not yet been conducted, but compilations of case reports have yielded important insights. Collectively, severe organ toxicity, particularly in patients with DC who had received a myeloablative regimen, was the most common cause of death40. This observation highlights the importance of telomere maintenance on tissue repair, particularly after the exposure to DNA damaging agents in preparative regimens. In agreement with published reports, and in a case series of 11 patients with DC who were transplanted in different centers across the U.S., only 4 survived42. Of note, one of the survivors developed severe pulmonary fibrosis 8 years post-transplant. Late post-transplant graft failure has been reported in several recipients who had very short blood telomere lengths after engraftment101.

A recent report of a DC-specific non-myeloablative regimen, which included cyclophosphamide (single dose), fludarabine, alemtuzumab, and total body irradiation (200cGy) reported a favorable short term outcome in a small number of patients (67% survived with a median follow-up of 26.5 months), but long-term outcomes are unknown102. In DC, it is especially important to exclude or reduce the dose of agents with known pulmonary and liver toxicity, in order to minimize the risk of organ fibrosis. Identifying patients with DC prior to HSCT, through telomere length testing, is important not only for selecting the least toxic/most effective transplant regimen, but also for appropriate donor selection decision-making. Clinically normal family members of DC patients are at some risk of being silent carriers of the same genetic disorder, which would make them ineligible as donors. For example, an adult patient who received HSCT for aplastic anemia from his apparently-healthy matched sibling had a complicated post-transplant course, in the form of delayed engraftment with long-lasting neutropenia and died of sepsis approximately 6 month after transplantation103. The sibling donor – who had no clinical evidence to suggest DC when marrow stem cells were collected - was subsequently found to have the same TERC mutation as the recipient. Using telomere length as a diagnostic tool for DC in this setting is particularly important for patients who do not have a mutation in one of the known genes, and as a DC screening test for patients who do not present with the typical clinical triad.

Donor age:

Increasing donor age is associated with reduced overall and disease-free survival after HSCT. The presence of shorter telomeres in older donors suggests that their HSC may not have the same replicative capacity as HSC from younger donors. In a large follow-up study of 6,978 recipients of unrelated donor bone marrow HSCT104, statistically significant trends, based on increasing donor age 18 to 30 years, 31 to 45 years, and more than 45 years), were noted in five-year overall survival (33%, 29%, and 25%, respectively), cumulative incidence of severe acute (30%, 34%, and 34%), and chronic (44%, 48%, and 49%) GvHD. In addition, transplant recipients who received HSC from young donors were at lower risk of developing obstructive lung diseases105, including bronchiolitis obliterans106, secondary graft failure after initial engraftment107, and B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder108. The relatively limited cellular replicative capacity of older donor cells has also been reflected in solid organ transplantation. Donor age was found to be the strongest predictor for long term outcomes in renal transplantation, and was significantly associated with markers of cellular senescence in transplanted kidney109,110. Since telomere length shortens with age, it provides a biological explanation for the observed relationship between donor age and transplant outcome.

Inflammation and infections:

During the immediate course following HSCT, and even years after, transplant recipients are at risk of numerous complications, most commonly infections and GvHD. Long-term HSCT survivors who had chronic GvHD were more likely to have short telomeres in white blood cell subsets than those who did not95. This association could be explained by the fact that telomeres are sensitive to oxidative stress and chronic inflammation. Short telomeres have been reported in many chronic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis111, systemic lupus erythematosus112, ulcerative colitis113, atherosclerosis, and diabetes114. In addition, telomere shortening is associated with genetic variation in oxidative stress genes115, and genes regulating mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production116.

However, the observed association between short telomeres and chronic GvHD could also be explained by the use of immunosuppressive medication. In some instances, this effect seems to be agent-specific. Exposure of renal cells in vitro to cyclosporine A induced cellular senescence and shorter telomeres117. Exposure of human T-lymphocytes to cortisol was associated with a significant reduction in telomerase activity118. In a yeast study, TOR (Target of Rapamycin) inhibition suppressed cell death caused by inactivation of yeast telomere binding protein Cdc13p, but did not change telomere length119. It has been suggested that short telomeres in patients with GvHD correlates with karyotypic abnormalities and malignant transformation120.

Infections are common in HSCT and comprise one of the main causes of death in transplant recipients121. Chronic infections outside of the transplant setting, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) and hepatitis C (HCV), have been associated with short lymphocyte telomeres122,123. Chronic GvHD is an important risk factor for infectious events in HSCT recipients124, an association that is thought to be related to the immunosuppressive state that results from GvHD. HSCT recipients who have GvHD, or were exposed to repetitive infections, had short telomeres in isolated effective memory cells (CD27− CD4+), compared with healthy controls125. Further evidence from mouse models highlighted the interaction between telomere function and immune responses. In late generation TERC−/− mice, telomerase deficiency was associated with impaired antibody-mediated immune responses126. In wild-derived house mice accelerated telomere shortening was noted in response to antigenic stimulation, and repeated infection127. Taken together, these data suggest that recurrent infections shorten telomeres, which subsequently limit T cell proliferative capacity, and can impair the response to infection. Both chronic GvHD and inflammation may be important components of this association.

Lifestyle and behavioral factors:

Epidemiologic studies in non-HSCT populations suggest that various lifestyle factors, such as smoking, diet, and exercise, are associated with telomere length128–130. In addition to the medical complications related to HSCT, the same factors that affect telomere biology in the general population may also be important in HSCT recipients. For example, at least two studies suggest that a healthier lifestyle, defined by the presence of a lower BMI, more exercise, no smoking, and higher intake of fruits and vegetables was associated with longer telomeres131. Higher intake of dietary fiber and lower polyunsaturated fatty acid were associated with longer telomeres in the Nurses’ Health study128. Several studies have reported an association between smoking130,132,133 and short telomeres. Longer telomeres are associated with increased physical activity129, long-term use of hormonal replacement therapy134, less stressful lifestyle135 and healthier diets128.

There is accumulating evidence of a negative relationship between telomere length and psychosocial stress, a common observation in transplant recipients and their family members particularly in the peri-transplant period136. Shorter telomeres have been associated with mood disorders137, self reported stress135, and early social deprivation138. Additionally, levels of perceived stress and its duration were associated with lower telomerase activity, and higher oxidative stress index135. In a randomized controlled trial, a 3-month mediation program was associated with higher telomerase activity, believed to be mediated by decreased level of stress in the experimental group compared with control139. Additional studies have suggested that lifestyle modified the relationship between telomere length and atherosclerosis: healthier lifestyles in the form of more social support, lower meat consumption, as well as high fruit and vegetable consumption attenuated the risk of atherosclerosis in individuals with short telomeres140. Figure 2 provides examples of these environmental and lifestyle factors that might also affect the telomere biology of the donor cells in a HSCT recipient.

Figure 2:

Factors that may affect telomere length in HSCT recipients. Telomeres are sensitive to oxidative stress and DNA damage. Telomere length is associated with many factors, including age, genetics, and environmental exposures.

Abbreviations: HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; GvHD, graft versus host disease

Telomere Biology in Induced Pluripotent Stem cells (iPSCs)

The creation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has the potential to create a source of functioning differentiated cells, including hematopoietic cells. Similar to embryonic stem cells, iPSCs have self renewal, expansion, and differentiation capabilities141–143. This leads to the possibility of reprogramming patient-specific cells for use in HSCT. The current advances of human iPSCs in blood engineering were recently reviewed in144. Telomere dynamics in iPSCs and during stem cell differentiation are an important measure of cellular replicative capacity. Using iPSCs generated from mouse embryonic fibroblasts, Marion and colleagues145 showed that generated cells’ telomere length and telomere heterochromatin markers were similar to embryonic stem cells. Of interest, the generation of iPSCs from telomerase deficient mice was severely impaired; an observation that was recently confirmed in patients with DC phenotype caused by defects in telomerase complex genes (TERT, DKC1, or TCAB1)146. Telomeres were found to be significantly longer in iPSCs derived from human neonatal fibrblasts compared with the original cells147. They also progressively shortened after differentiation and reached a length similar to that of the differentiated fibroblasts. Telomere elongation in human iPSCs was associated with telomerase activation followed by telomerase down-regulation after differentiation. Of importance, the observed telomere elongation in iPSCs was independent of original cell age, where iPSCs derived from either old or young donors restored telomere length to that similar to embryonic stem cells. This observation was consistent in mice145 and human experiments148. Details about telomere restoration and dynamics during nuclear reprogramming have been recently reviewed in149,150.

Does Telomere Biology Have A Role In HSCT Outcome?

Survival after HSCT has shown significant improvement during recent decades, primarily due to advances in treatment modalities and supportive care. However, HSCT survivors are still at high risk of developing serious complications, including GvHD, serious infections, pulmonary complications, organ failure, and cancer151. The similarities between some of the post-HSCT complications and those associated with short telomeres in the general population suggest a role for telomere maintenance in short and long-term outcomes after HSCT.

Studies of the relationship between telomere defects, including short telomeres, and human diseases demonstrated an association with BMF, pulmonary and liver fibrosis, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, chronic inflammation, and premature aging47. In addition, epidemiological studies in the general population, show associations between short telomeres and excess risk of cancer, overall152, and in certain anatomic sites such as bladder, kidney, lung, head and neck153, and breast154. A recent meta-analysis155provided evidence of a modest association between short telomeres, comparing the shortest with the longest quartile, and cancer risk (OR=1.96, 95% CI=1.37–2.81). Data on the effect of post-HSCT telomere dynamics on long-term transplant outcomes are very limited. Late graft failure after primary engraftment has been suggested to be associated with short telomeres in 2 case reports101. A relationship between short telomeres and chronic GvHD has also been reported95, but it is not clear whether this relationship is specific to certain types of GvHD, such as fibrotic, or hematologic. Chronic GvHD in HSCT recipients is associated with elevated risk of second cancers156, an association that has been explained, in part, by the long term use of immunosuppressive medication in those patients157. The relationship between GvHD in HSCT recipients and short telomeres95, might explain, at least in part, cancer development in those patients; a hypothesis that needs to be tested.

A comprehensive assessment of the role of telomere length and its relationship to HSCT transplantation outcomes is needed. A longitudinal study with a large sample size would be essential to assessing changes of telomere length over time, starting with telomere length in infused cells, and to evaluating the effect of telomere dynamics on HSCT outcomes. If a relationship exists, it will be important identify factors affecting this dynamics, particularly those that can be modified, such as donor selection, type of preparative regimen, type of immunosuppressive medication, and/or recipient lifestyle.

Conclusions:

In healthy individuals, the gradual telomere loss in hematopoietic cells with age has been suggested to contribute to declines in hematopoiesis, immunosenescence, and malignant transformation. In HSCT, the telomeres of the donor, experience significant attrition once infused into the recipient, particularly during engraftment and in the first post-transplant year. The rate of telomere attrition does not seem to differ significantly by stem cell source. However, UCB transplants were associated with longer telomeres than other sources, mostly because UCB have longer telomeres at the beginning. Telomere length in the blood cells of HSCT donors is a biomarker of both their biological and physiological age, and may be correlated with long-term outcomes after HSCT. We hypothesize that transplant recipients who receive HSCT from a donor with short telomeres, or who experience severe telomere attrition as a result of transplant-related complications, may be at high risk of graft failure, second malignancies, and other complications. Large, prospective studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

Practice Points:

Incorporating telomere length measurement into the initial evaluation of patients with aplastic anemia (BMF) is currently the most cost-effective way to identify patients with BMF patients who have a telomere biology disorder.

Identifying patients with classic or occult dyskeratosis congenita (i.e., a telomere biology disorder) prior to HSCT is important transplant regimen decision-making (with consideration of non-myeloablative regimens).

Telomere length should be measured in potential HSCT donors who are related to a recipient with short telomeres because they may be clinically silent but carry the same genetic abnormality. This may result in graft failure.

In HSCT for DC (classic and occult) and related telomere biology disorders, it is important to exclude or reduce the dose of agents with known pulmonary and liver toxicity, to avoid potentially life-threatening end-organ fibrosis.

Research Agenda:

Identify the long term outcome of HSCT for patients with telomere biology disorders

Determine the best conditioning regimen for patients with telomere biology disorders

Determine the role of donor telomere length in recipients’ outcomes after HSCT

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Drs. Mark H. Greene, and Neelam Giri, Clinical Genetic Branch, National Cancer Institute, USA, for their critical review of the manuscript and their valuable comments.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Olovnikov AM. A theory of marginotomy. The incomplete copying of template margin in enzymic synthesis of polynucleotides and biological significance of the phenomenon. J Theor. Biol 1973; 41: 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greider CW, Blackburn EH. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts. Cell 1985; 43: 405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackburn EH. Structure and function of telomeres. Nature 1991; 350: 569–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harley CB, Futcher AB, Greider CW. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature 1990; 345: 458–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nalapareddy K, Jiang H, Guachalla Gutierrez LM, Rudolph KL. Determining the influence of telomere dysfunction and DNA damage on stem and progenitor cell aging: what markers can we use? Exp. Gerontol 2008; 43: 998–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harley CB, Vaziri H, Counter CM, Allsopp RC. The telomere hypothesis of cellular aging. Exp. Gerontol 1992; 27: 375–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takubo K, Aida J, Izumiyama-Shimomura N, Ishikawa N, Sawabe M, Kurabayashi R et al. Changes of telomere length with aging. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int 2010; 10 Suppl 1: S197–S206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nordfjall K, Svenson U, Norrback KF, Adolfsson R, Lenner P, Roos G. The individual blood cell telomere attrition rate is telomere length dependent. PLoS. Genet 2009; 5: e1000375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aviv A, Chen W, Gardner JP, Kimura M, Brimacombe M, Cao X et al. Leukocyte telomere dynamics: longitudinal findings among young adults in the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am. J Epidemiol 2009; 169: 323–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harle-Bachor C, Boukamp P. Telomerase activity in the regenerative basal layer of the epidermis inhuman skin and in immortal and carcinoma-derived skin keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1996; 93: 6476–6481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiyama K, Hirai Y, Kyoizumi S, Akiyama M, Hiyama E, Piatyszek MA et al. Activation of telomerase in human lymphocytes and hematopoietic progenitor cells. J Immunol. 1995; 155: 3711–3715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cong YS, Wright WE, Shay JW. Human telomerase and its regulation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 2002; 66: 407–25, table. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shay JW, Bacchetti S. A survey of telomerase activity in human cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 1997; 33: 787–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cesare AJ, Reddel RR. Alternative lengthening of telomeres: models, mechanisms and implications. Nat. Rev. Genet 2010; 11: 319–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Lange T Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev. 2005; 19: 2100–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palm W, de LT. How shelterin protects mammalian telomeres. Annu. Rev. Genet 2008; 42: 301–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martens UM, Zijlmans JM, Poon SS, Dragowska W, Yui J, Chavez EA et al. Short telomeres on human chromosome 17p. Nat. Genet 1998; 18: 76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moller P, Mayer S, Mattfeldt T, Muller K, Wiegand P, Bruderlein S. Sex-related differences in length and erosion dynamics of human telomeres favor females. Aging (Albany. NY) 2009; 1: 733–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butler MG, Tilburt J, DeVries A, Muralidhar B, Aue G, Hedges L et al. Comparison of chromosome telomere integrity in multiple tissues from subjects at different ages. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet 1998; 105: 138–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mondello C, Petropoulou C, Monti D, Gonos ES, Franceschi C, Nuzzo F. Telomere length in fibroblasts and blood cells from healthy centenarians. Exp. Cell Res 1999; 248: 234–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedrich U, Griese E, Schwab M, Fritz P, Thon K, Klotz U. Telomere length in different tissues of elderly patients. Mech. Ageing Dev 2000; 119: 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura K, Izumiyama-Shimomura N, Sawabe M, Arai T, Aoyagi Y, Fujiwara M et al. Comparative analysis of telomere lengths and erosion with age in human epidermis and lingual epithelium. J. Invest Dermatol 2002; 119: 1014–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takubo K, Izumiyama-Shimomura N, Honma N, Sawabe M, Arai T, Kato M et al. Telomere lengths are characteristic in each human individual. Exp. Gerontol 2002; 37: 523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thibeault SL, Glade RS, Li W. Comparison of telomere length of vocal folds with different tissues: a physiological measurement of vocal senescence. J Voice 2006; 20: 165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gadalla SM, Cawthon R, Giri N, Alter BP, Savage SA. Telomere length in blood, buccal cells, and fibroblasts from patients with inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Aging (Albany. NY) 2010; 2: 867–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baird DM. New developments in telomere length analysis. Exp. Gerontol 2005; 40: 363–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin KW, Yan J. The telomere length dynamic and methods of its assessment. J. Cell Mol. Med 2005; 9: 977–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lansdorp PM. Telomere length and proliferation potential of hematopoietic stem cells. J. Cell Sci 1995; 108 (Pt 1): 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hills M, Lucke K, Chavez EA, Eaves CJ, Lansdorp PM. Probing the mitotic history and developmental stage of hematopoietic cells using single telomere length analysis (STELA). Blood 2009; 113: 5765–5775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeichner SL, Palumbo P, Feng Y, Xiao X, Gee D, Sleasman J et al. Rapid telomere shortening in children. Blood 1999; 93: 2824–2830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rufer N, Brummendorf TH, Kolvraa S, Bischoff C, Christensen K, Wadsworth L et al. Telomere fluorescence measurements in granulocytes and T lymphocyte subsets point to a high turnover of hematopoietic stem cells and memory T cells in early childhood. J. Exp. Med 1999; 190: 157–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martens UM, Brass V, Sedlacek L, Pantic M, Exner C, Guo Y et al. Telomere maintenance in human B lymphocytes. Br. J. Haematol 2002; 119: 810–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Son NH, Murray S, Yanovski J, Hodes RJ, Weng N. Lineage-specific telomere shortening and unaltered capacity for telomerase expression in human T and B lymphocytes with age. J Immunol. 2000; 165: 1191–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rufer N, Dragowska W, Thornbury G, Roosnek E, Lansdorp PM. Telomere length dynamics in human lymphocyte subpopulations measured by flow cytometry. Nat. Biotechnol 1998; 16: 743–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kimura M, Gazitt Y, Cao X, Zhao X, Lansdorp PM, Aviv A. Synchrony of Telomere Length among Hematopoietic Cells. Exp. Hematol 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heiss NS, Knight SW, Vulliamy TJ, Klauck SM, Wiemann S, Mason PJ et al. X-linked dyskeratosis congenita is caused by mutations in a highly conserved gene with putative nucleolar functions. Nat. Genet 1998; 19: 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell JR, Wood E, Collins K. A telomerase component is defective in the human disease dyskeratosis congenita. Nature 1999; 402: 551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Savage SA, Alter BP. Dyskeratosis congenita. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am 2009; 23: 215–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al Rahawan MM, Giri N, Alter BP. Intensive immunosuppression therapy for aplastic anemia associated with dyskeratosis congenita. Int. J. Hematol 2006; 83: 275–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de la Fuente J, Dokal I. Dyskeratosis congenita: advances in the understanding of the telomerase defect and the role of stem cell transplantation. Pediatr. Transplant 2007; 11: 584–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Armanios M Syndromes of Telomere Shortening. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alter BP, Giri N, Savage SA, Rosenberg PS. Cancer in dyskeratosis congenita. Blood 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhong F, Savage SA, Shkreli M, Giri N, Jessop L, Myers T et al. Disruption of telomerase trafficking by TCAB1 mutation causes dyskeratosis congenita. Genes Dev. 2011; 25: 11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alter BP, Baerlocher GM, Savage SA, Chanock SJ, Weksler BB, Willner JP et al. Very short telomere length by flow fluorescence in situ hybridization identifies patients with dyskeratosis congenita. Blood 2007; 110: 1439–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du HY, Pumbo E, Ivanovich J, An P, Maziarz RT, Reiss UM et al. TERC and TERT gene mutations in patients with bone marrow failure and the significance of telomere length measurements. Blood 2009; 113: 309–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Savage SA, Bertuch AA. The genetics and clinical manifestations of telomere biology disorders. Genet. Med 2010; 12: 753–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Savage SA, Alter BP. The role of telomere biology in bone marrow failure and other disorders. Mech. Ageing Dev 2008; 129: 35–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Calado RT, Young NS. Telomere maintenance and human bone marrow failure. Blood 2008; 111: 4446–4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ball SE, Gibson FM, Rizzo S, Tooze JA, Marsh JC, Gordon-Smith EC. Progressive telomere shortening in aplastic anemia. Blood 1998; 91: 3582–3592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scheinberg P, Cooper JN, Sloand EM, Wu CO, Calado RT, Young NS. Association of telomere length of peripheral blood leukocytes with hematopoietic relapse, malignant transformation, and survival in severe aplastic anemia. JAMA 2010; 304: 1358–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Komrokji RS, Zhang L, Bennett JM. Myelodysplastic syndromes classification and risk stratification. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am 2010; 24: 443–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lange K, Holm L, Vang NK, Hahn A, Hofmann W, Kreipe H et al. Telomere shortening and chromosomal instability in myelodysplastic syndromes. Genes Chromosomes. Cancer 2010; 49: 260–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ohyashiki K, Iwama H, Yahata N, Tauchi T, Kawakubo K, Shimamoto T et al. Telomere dynamics in myelodysplastic syndromes and acute leukemic transformation. Leuk. Lymphoma 2001; 42: 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kirwan M, Vulliamy T, Marrone A, Walne AJ, Beswick R, Hillmen P et al. Defining the pathogenic role of telomerase mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Hum. Mutat 2009; 30: 1567–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Calado RT, Regal JA, Hills M, Yewdell WT, Dalmazzo LF, Zago MA et al. Constitutional hypomorphic telomerase mutations in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2009; 106: 1187–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ohyashiki JH, Iwama H, Yahata N, Ando K, Hayashi S, Shay JW et al. Telomere stability is frequently impaired in high-risk groups of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Clin. Cancer Res 1999; 5: 1155–1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gurkan E, Tanriverdi K, Baslamisli F. Telomerase activity in myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk. Res 2005; 29: 1131–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boultwood J, Fidler C, Kusec R, Rack K, Elliott PJ, Atoyebi O et al. Telomere length in myelodysplastic syndromes. Am. J Hematol 1997; 56: 266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deville L, Hillion J, Lanotte M, Rousselot P, Segal-Bendirdjian E. Diagnostics, prognostic and therapeutic exploitation of telomeres and telomerase in leukemias. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol 2006; 7: 171–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Telomeres Yamada O. and telomerase in human hematologic neoplasia. Int. J. Hematol 1996; 64: 87–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ohyashiki JH, Sashida G, Tauchi T, Ohyashiki K. Telomeres and telomerase in hematologic neoplasia. Oncogene 2002; 21: 680–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Engelhardt M, Mackenzie K, Drullinsky P, Silver RT, Moore MA. Telomerase activity and telomere length in acute and chronic leukemia, pre- and post-ex vivo culture. Cancer Res. 2000; 60: 610–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Capraro V, Zane L, Poncet D, Perol D, Galia P, Preudhomme C et al. Telomere deregulations possess cytogenetic, phenotype, and prognostic specificities in acute leukemias. Exp. Hematol 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brummendorf TH, Rufer N, Holyoake TL, Maciejewski J, Barnett MJ, Eaves CJ et al. Telomere length dynamics in normal individuals and in patients with hematopoietic stem cell-associated disorders. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 2001; 938: 293–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Drummond MW, Hoare SF, Monaghan A, Graham SM, Alcorn MJ, Keith WN et al. Dysregulated expression of the major telomerase components in leukaemic stem cells. Leukemia 2005; 19: 381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang Y, Fang M, Sun X, Sun J. Telomerase activity and telomere length in acute leukemia: correlations with disease progression, subtypes and overall survival. Int J Lab Hematol 2010; 32: 230–238. Epub 2009 Jul 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kubuki Y, Suzuki M, Sasaki H, Toyama T, Yamashita K, Maeda K et al. Telomerase activity and telomere length as prognostic factors of adult T-cell leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2005; 46: 393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Keller G, Brassat U, Braig M, Heim D, Wege H, Brummendorf TH. Telomeres and telomerase in chronic myeloid leukaemia: impact for pathogenesis, disease progression and targeted therapy. Hematol Oncol. 2009; 27: 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kleideiter E, Bangerter U, Schwab M, Boukamp P, Koscielniak E, Klotz U et al. Telomeres and telomerase in paediatric patients with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (T-ALL). Leukemia 2005; 19: 296–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boultwood J, Fidler C, Shepherd P, Watkins F, Snowball J, Haynes S et al. Telomere length shortening is associated with disease evolution in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Am. J. Hematol 1999; 61: 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boultwood J, Peniket A, Watkins F, Shepherd P, McGale P, Richards S et al. Telomere length shortening in chronic myelogenous leukemia is associated with reduced time to accelerated phase. Blood 2000; 96: 358–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ohyashiki K, Ohyashiki JH, Iwama H, Hayashi S, Shay JW, Toyama K. Telomerase activity and cytogenetic changes in chronic myeloid leukemia with disease progression. Leukemia 1997; 11: 190–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ohyashiki K, Iwama H, Tauchi T, Shimamoto T, Hayashi S, Ando K et al. Telomere dynamics and genetic instability in disease progression of chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2000; 40: 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brummendorf TH, Ersoz I, Hartmann U, Balabanov S, Wolke H, Paschka P et al. Normalization of previously shortened telomere length under treatment with imatinib argues against a preexisting telomere length deficit in normal hematopoietic stem cells from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 2003; 996: 26–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yamada O, Kawauchi K, Akiyama M, Ozaki K, Motoji T, Adachi T et al. Leukemic cells with increased telomerase activity exhibit resistance to imatinib. Leuk. Lymphoma 2008; 49: 1168–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Copelan EA. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. N. Engl. J Med 2006; 354: 1813–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thornley I, Sutherland R, Wynn R, Nayar R, Sung L, Corpus G et al. Early hematopoietic reconstitution after clinical stem cell transplantation: evidence for stochastic stem cell behavior and limited acceleration in telomere loss. Blood 2002; 99: 2387–2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Novitzky N, Mohammed R. Alterations in the progenitor cell population follow recovery from myeloablative therapy and bone marrow transplantation. Exp. Hematol 1997; 25: 471–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Podesta M, Piaggio G, Frassoni F, Pitto A, Mordini N, Bregante S et al. Deficient reconstitution of early progenitors after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997; 19: 1011–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brummendorf TH, Balabanov S. Telomere length dynamics in normal hematopoiesis and in disease states characterized by increased stem cell turnover. Leukemia 2006; 20: 1706–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Akiyama M, Asai O, Kuraishi Y, Urashima M, Hoshi Y, Sakamaki H et al. Shortening of telomeres in recipients of both autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000; 25: 441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lahav M, Uziel O, Kestenbaum M, Fraser A, Shapiro H, Radnay J et al. Nonmyeloablative conditioning does not prevent telomere shortening after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Transplantation 2005; 80: 969–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brummendorf TH, Rufer N, Baerlocher GM, Roosnek E, Lansdorp PM. Limited telomere shortening in hematopoietic stem cells after transplantation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 2001; 938: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Robertson JD, Testa NG, Russell NH, Jackson G, Parker AN, Milligan DW et al. Accelerated telomere shortening following allogeneic transplantation is independent of the cell source and occurs within the first year post transplant. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001; 27: 1283–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Roelofs H, de Pauw ES, Zwinderman AH, Opdam SM, Willemze R, Tanke HJ et al. Homeostasis of telomere length rather than telomere shortening after allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Blood 2003; 101: 358–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Champlin RE, Schmitz N, Horowitz MM, Chapuis B, Chopra R, Cornelissen JJ et al. Blood stem cells compared with bone marrow as a source of hematopoietic cells for allogeneic transplantation. IBMTR Histocompatibility and Stem Cell Sources Working Committee and the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Blood 2000; 95: 3702–3709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mahmoud H, Fahmy O, Kamel A, Kamel M, El-Haddad A, El-Kadi D. Peripheral blood vs bone marrow as a source for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999; 24: 355–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Notaro R, Cimmino A, Tabarini D, Rotoli B, Luzzatto L. In vivo telomere dynamics of human hematopoietic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1997; 94: 13782–13785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pipes BL, Tsang T, Peng SX, Fiederlein R, Graham M, Harris DT. Telomere length changes after umbilical cord blood transplant. Transfusion 2006; 46: 1038–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.de Pauw ES, Verwoerd NP, Duinkerken N, Willemze R, Raap AK, Fibbe WE et al. Assessment of telomere length in hematopoietic interphase cells using in situ hybridization and digital fluorescence microscopy. Cytometry 1998; 32: 163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Friedrich U, Schwab M, Griese EU, Fritz P, Klotz U. Telomeres in neonates: new insights in fetal hematopoiesis. Pediatr. Res 2001; 49: 252–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ruella M, Rocci A, Ricca I, Carniti C, Bodoni CL, Ladetto M et al. Comparative assessment of telomere length before and after hematopoietic SCT: role of grafted cells in determining post-transplant telomere status. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010; 45: 505–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Allsopp RC, Cheshier S, Weissman IL. Telomerase activation and rejuvenation of telomere length in stimulated T cells derived from serially transplanted hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp. Med 2002; 196: 1427–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Allsopp RC, Morin GB, DePinho R, Harley CB, Weissman IL. Telomerase is required to slow telomere shortening and extend replicative lifespan of HSCs during serial transplantation. Blood 2003; 102: 517–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Baerlocher GM, Rovo A, Muller A, Matthey S, Stern M, Halter J et al. Cellular senescence of white blood cells in very long-term survivors after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: the role of chronic graft-versus-host disease and female donor sex. Blood 2009; 114: 219–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.de Pauw ES, Otto SA, Wijnen JT, Vossen JM, van Weel MH, Tanke HJ et al. Long-term follow-up of recipients of allogeneic bone marrow grafts reveals no progressive telomere shortening and provides no evidence for haematopoietic stem cell exhaustion. Br. J. Haematol 2002; 116: 491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Blasco MA, Lee HW, Hande MP, Samper E, Lansdorp PM, DePinho RA et al. Telomere shortening and tumor formation by mouse cells lacking telomerase RNA. Cell 1997; 91: 25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chang S Modeling premature aging syndromes with the telomerase knockout mouse. Curr. Mol. Med 2005; 5: 153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ju Z, Jiang H, Jaworski M, Rathinam C, Gompf A, Klein C et al. Telomere dysfunction induces environmental alterations limiting hematopoietic stem cell function and engraftment. Nat. Med 2007; 13: 742–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Song Z, Wang J, Guachalla LM, Terszowski G, Rodewald HR, Ju Z et al. Alterations of the systemic environment are the primary cause of impaired B and T lymphopoiesis in telomere-dysfunctional mice. Blood 2010; 115: 1481–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Awaya N, Baerlocher GM, Manley TJ, Sanders JE, Mielcarek M, Torok-Storb B et al. Telomere shortening in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a potential mechanism for late graft failure? Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant 2002; 8: 597–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dietz AC, Orchard PJ, Baker KS, Giller RH, Savage SA, Alter BP et al. Disease-specific hematopoietic cell transplantation: nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen for dyskeratosis congenita. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011; 46: 98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fogarty PF, Yamaguchi H, Wiestner A, Baerlocher GM, Sloand E, Zeng WS et al. Late presentation of dyskeratosis congenita as apparently acquired aplastic anaemia due to mutations in telomerase RNA. Lancet 2003; 362: 1628–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kollman C, Howe CW, Anasetti C, Antin JH, Davies SM, Filipovich AH et al. Donor characteristics as risk factors in recipients after transplantation of bone marrow from unrelated donors: the effect of donor age. Blood 2001; 98: 2043–2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schultz KR, Green GJ, Wensley D, Sargent MA, Magee JF, Spinelli JJ et al. Obstructive lung disease in children after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood 1994; 84: 3212–3220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dudek AZ, Mahaseth H, DeFor TE, Weisdorf DJ. Bronchiolitis obliterans in chronic graft-versus-host disease: analysis of risk factors and treatment outcomes. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant 2003; 9: 657–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Davies SM, Kollman C, Anasetti C, Antin JH, Gajewski J, Casper JT et al. Engraftment and survival after unrelated-donor bone marrow transplantation: a report from the national marrow donor program. Blood 2000; 96: 4096–4102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gross TG, Steinbuch M, DeFor T, Shapiro RS, McGlave P, Ramsay NK et al. B cell lymphoproliferative disorders following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: risk factors, treatment and outcome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999; 23: 251–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Koppelstaetter C, Schratzberger G, Perco P, Hofer J, Mark W, Ollinger R et al. Markers of cellular senescence in zero hour biopsies predict outcome in renal transplantation. Aging Cell 2008; 7: 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.McGlynn LM, Stevenson K, Lamb K, Zino S, Brown M, Prina A et al. Cellular senescence in pretransplant renal biopsies predicts postoperative organ function. Aging Cell 2009; 8: 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Koetz K, Bryl E, Spickschen K, O’Fallon WM, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. T cell homeostasis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2000; 97: 9203–9208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Honda M, Mengesha E, Albano S, Nichols WS, Wallace DJ, Metzger A et al. Telomere shortening and decreased replicative potential, contrasted by continued proliferation of telomerase-positive CD8+CD28(lo) T cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Immunol 2001; 99: 211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.O’Sullivan JN, Bronner MP, Brentnall TA, Finley JC, Shen WT, Emerson S et al. Chromosomal instability in ulcerative colitis is related to telomere shortening. Nat. Genet 2002; 32: 280–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Salpea KD, Humphries SE. Telomere length in atherosclerosis and diabetes. Atherosclerosis 2010; 209: 35–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Starr JM, Shiels PG, Harris SE, Pattie A, Pearce MS, Relton CL et al. Oxidative stress, telomere length and biomarkers of physical aging in a cohort aged 79 years from the 1932 Scottish Mental Survey. Mech. Ageing Dev 2008; 129: 745–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Salpea KD, Talmud PJ, Cooper JA, Maubaret CG, Stephens JW, Abelak K et al. Association of telomere length with type 2 diabetes, oxidative stress and UCP2 gene variation. Atherosclerosis 2010; 209: 42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Jennings P, Koppelstaetter C, Aydin S, Abberger T, Wolf AM, Mayer G et al. Cyclosporine A induces senescence in renal tubular epithelial cells. Am. J Physiol Renal Physiol 2007; 293: F831–F838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Choi J, Fauce SR, Effros RB. Reduced telomerase activity in human T lymphocytes exposed to cortisol. Brain Behav. Immun 2008; 22: 600–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Qi H, Chen Y, Fu X, Lin CP, Zheng XF, Liu LF. TOR regulates cell death induced by telomere dysfunction in budding yeast. PLoS. One 2008; 3: e3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sloand EM, Pfannes L, Ling C, Feng X, Jasek M, Calado R et al. Graft-versus-host disease: role of inflammation in the development of chromosomal abnormalities of keratinocytes. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant 2010; 16: 1665–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Martin-Pena A, Aguilar-Guisado M, Espigado I, Parody R, Miguel CJ. Prospective study of infectious complications in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin. Transplant 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kitay-Cohen Y, Goldberg-Bittman L, Hadary R, Fejgin MD, Amiel A. Telomere length in Hepatitis C. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet 2008; 187: 34–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.van de Berg PJ, Griffiths SJ, Yong SL, Macaulay R, Bemelman FJ, Jackson S et al. Cytomegalovirus infection reduces telomere length of the circulating T cell pool. J Immunol. 2010; 184: 3417–3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Martin-Pena A, Aguilar-Guisado M, Espigado I, Parody R, Miguel CJ. Prospective study of infectious complications in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin. Transplant 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Fukunaga A, Ishikawa T, Kishihata M, Shindo T, Hori T, Uchiyama T. Altered homeostasis of CD4(+) memory T cells in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: chronic graft-versus-host disease enhances T cell differentiation and exhausts central memory T cell pool. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant 2007; 13: 1176–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Herrera E, Martinez A, Blasco MA. Impaired germinal center reaction in mice with short telomeres. EMBO J 2000; 19: 472–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ilmonen P, Kotrschal A, Penn DJ. Telomere attrition due to infection. PLoS. One 2008; 3: e2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Cassidy A, De V, I, Liu Y, Han J, Prescott J, Hunter DJ et al. Associations between diet, lifestyle factors, and telomere length in women. Am. J Clin. Nutr 2010; 91: 1273–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Cherkas LF, Hunkin JL, Kato BS, Richards JB, Gardner JP, Surdulescu GL et al. The association between physical activity in leisure time and leukocyte telomere length. Arch. Intern. Med 2008; 168: 154–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Valdes AM, Andrew T, Gardner JP, Kimura M, Oelsner E, Cherkas LF et al. Obesity, cigarette smoking, and telomere length in women. Lancet 2005; 366: 662–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Mirabello L, Huang WY, Wong JY, Chatterjee N, Reding D, Crawford ED et al. The association between leukocyte telomere length and cigarette smoking, dietary and physical variables, and risk of prostate cancer. Aging Cell 2009; 8: 405–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Morla M, Busquets X, Pons J, Sauleda J, MacNee W, Agusti AG. Telomere shortening in smokers with and without COPD. Eur. Respir. J 2006; 27: 525–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.McGrath M, Wong JY, Michaud D, Hunter DJ, De V, I. Telomere length, cigarette smoking, and bladder cancer risk in men and women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 2007; 16: 815–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lee DC, Im JA, Kim JH, Lee HR, Shim JY. Effect of long-term hormone therapy on telomere length in postmenopausal women. Yonsei Med. J 2005; 46: 471–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Epel ES, Blackburn EH, Lin J, Dhabhar FS, Adler NE, Morrow JD et al. Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2004; 101: 17312–17315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Packman W, Weber S, Wallace J, Bugescu N. Psychological effects of hematopoietic SCT on pediatric patients, siblings and parents: a review. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010; 45: 1134–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Simon NM, Smoller JW, McNamara KL, Maser RS, Zalta AK, Pollack MH et al. Telomere shortening and mood disorders: preliminary support for a chronic stress model of accelerated aging. Biol. Psychiatry 2006; 60: 432–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Drury SS, Theall K, Gleason MM, Smyke AT, De V, I, Wong JY et al. Telomere length and early severe social deprivation: linking early adversity and cellular aging. Mol. Psychiatry 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Jacobs TL, Epel ES, Lin J, Blackburn EH, Wolkowitz OM, Bridwell DA et al. Intensive meditation training, immune cell telomerase activity, and psychological mediators. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011; 36: 664–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Diaz VA, Mainous AG III, Everett CJ, Schoepf UJ, Codd V, Samani NJ. Effect of healthy lifestyle behaviors on the association between leukocyte telomere length and coronary artery calcium. Am. J Cardiol 2010; 106: 659–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 2007; 318: 1917–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 2007; 131: 861–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, Yabuuchi A, Huo H, Ince TA et al. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature 2008; 451: 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Dravid GG, Crooks GM. The challenges and promises of blood engineered from human pluripotent stem cells. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Marion RM, Strati K, Li H, Tejera A, Schoeftner S, Ortega S et al. Telomeres acquire embryonic stem cell characteristics in induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2009; 4: 141–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Batista LF, Pech MF, Zhong FL, Nguyen HN, Xie KT, Zaug AJ et al. Telomere shortening and loss of self-renewal in dyskeratosis congenita induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]