Abstract

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is one of the leading causes of mortality around the world, and the inflammatory response plays a pivotal role in the progress of myocardial necrosis and ventricular remodeling, dysfunction and heart failure after AMI. Therapies aimed at modulating immune response after AMI on a molecular and cellular basis are urgently needed. Exosomes are a type of extracellular vesicles which contain a large amount of biologically active substances, like lipids, nucleic acids, proteins and so on. Emerging evidence suggests key roles of exosomes in immune regulation post AMI. A variety of immune cells participate in the immunomodulation after AMI, working together to clean up necrotic tissue and repair damaged myocardium. Stem cell therapy for myocardial infarction has long been a research hotspot during the last two decades and exosomes secreted by stem cells are important active substances and have similar therapeutic effects of immunomodulation, anti-apoptosis, anti-fibrotic and angiogenesis to those of stem cells themselves. Therefore, in this review, we focus on the characteristics and roles of exosomes produced by both of endogenous immune cells and exogenous stem cells in myocardial repair through immunomodulation after AMI.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction, exosome, immunomodulation, immune cells, stem cells

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) has long been a major cause of death in coronary artery disease worldwide despite the improved medical care 1, 2. When blood supply is abruptly blocked in coronary artery, massive cardiomyocytes undergo necrotic process and an intense inflammatory response is then triggered to clear necrotic debris. In the early phase of inflammation response dominated by immune cells after AMI, the intensive pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines are released to outbreak inflammatory process to digest damaged cells and extracellular matrix (ECM) tissue. In the next several days, the inflammatory phase gradually switches to reparative phase including inflammation resolution, neovascularization and scar formation. The expansion of immune cells and excessive prolonged inflammation response contribute to ischemic cardiomyopathy, which makes targeting inflammation response after myocardial infarction (MI) a potential strategy to attenuate myocardial dysfunction and heart failure (HF) 3, 4.

Exosomes, secreted by cells to extracellular space via exocytosis, is a vital way of intercellular communication. Formed by a lipid bilayer of plasma membrane origin and having multifarious biological cargo contents such as lipids, proteins, and RNAs, exosomes are involved in numerous physiological processes including immune regulation 5. In recent years, their roles in immune regulation on a molecular and cellular basis have been gradually unveiled in the context of AMI 6, 7. Meanwhile, immune cells and stem cells, which are important cell therapy for AMI, have been confirmed as promising strategies for immunomodulation of AMI 8, 9. Therefore, in this review we will summarize the characteristics and biological function of exosomes and the roles of exosomes derived from immune cells and stem cells in cardiac repair through modulation of immune responses post MI.

Exosomes: secreted vesicles for intercellular communications

Exosomes, a major subgroup of extracellular vesicles (EVs), generally range in size from 30 to 200 nm in diameter 10. They can be found in most body fluids including plasma, serum, saliva, amniotic fluid, breast milk, and urine 11, and they can be released by various cell types such as dendritic cells (DCs), mast cells, platelets 12, as well as mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) 13.

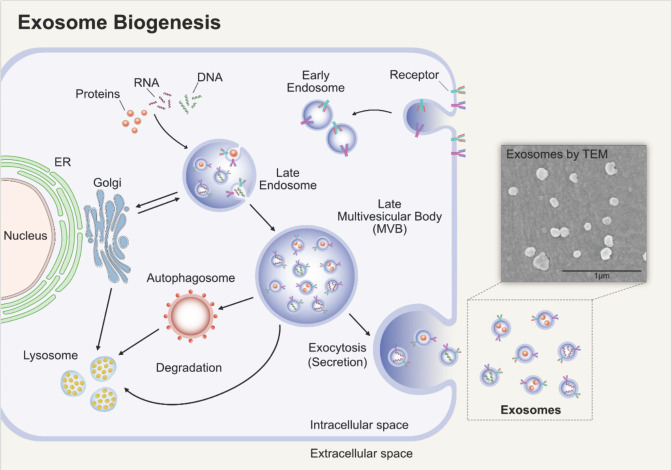

Exosomes will undergo double invagination of the plasma membrane. The first invagination is accompanied by endocytosis of parent cell, and then the early endosomes are generated in cytoplasma. Early endosomes can mature into late endosomes and finally multivesicular bodies (MVBs) or multivesicular endosomes. The MVBs will then undergo the second invagination of the plasma membrane, thus forming intraluminal vesicles (ILVs). There are two outcomes, to fuse with lysosomes or autophagosomes undergoing degradation or to fuse with the plasma membrane and release the ILVs, that is what we called exosomes 14 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Biogenesis of exosomes. Early endosomes are generated by endocytosis of parent cell. It will then undergo the second invagination of the plasma membrane, thus forming ILVs, and the endosomes that enclose the ILVs are MVBs. MVBs can fuse with the plasma membrane and release the ILVs, namely exosomes. Adapted with permission from 15, Copyright (2019).

Exosomes have been confirmed to be vital carriers of unique cargo of lipids, proteins and RNAs, which are usually distinct from the parent cell of its origin 14, 16. It has been proposed that exosomes bind to the plasma membrane of recipient cells via specific receptors and are either internalized by micropinocytosis to fuse with the membrane to release its contents of lipids, proteins and RNAs 17, 18 or are internalized by distinct endocytosis. Because of these characteristics that they have, exosomes seem to be capable of acting as vehicles for drug delivery to convey its RNA and protein contents.

Multiple cell types including cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, cardiac fibroblasts and immune cells work together to make the heart function properly. In response to distinct types of stress, different kinds of cardiac cells are able to secrete biological molecules to mediate intercellular communication in which exosome plays an essential role. For example, under ischemic conditions, miR-222 and miR-143 are abundant in exosomes derived from cardiomyocytes which stimulate the neovascularization following AMI 19. Endothelial cells, which are crucial for the establishment and maintenance of vascular integrity, could release exosomes that contain miR-214 to stimulate angiogenesis 20. Taken together, these data indicate the importance of exosomes in intercellular communications between different cell types.

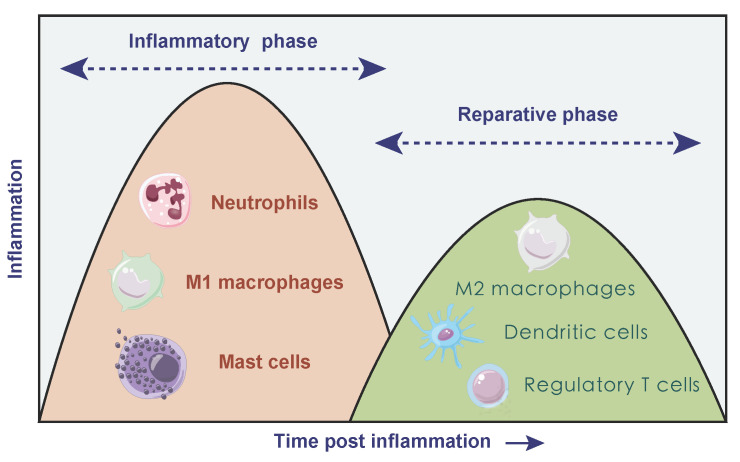

Two phases of inflammatory responses after AMI

Due to the necrosis of infarcted myocardium, vascular endothelial cell integrity and its barrier function are impaired accompanied with sudden massive loss of cardiomyocytes, facilitating the release of danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) 21. DAMPs are cytoplasmic or nuclear components that can be released into the extracellular environment due to cell necrosis, including heat shock proteins, high mobility group box 1. It can activate the immune system thus triggering immune responses 22 via binding to cognate pattern recognition receptors containing toll-like receptor/interleukin 1 receptors (TLR/IL1R) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors on surviving cardiomyocytes 23-28. In turn, receptor activation triggers intercellular crosstalk signal and results in the release of various pro-inflammatory mediators. Cardiomyocyte-released chemokines promote immune cell extravasation and recruitment through binding to the related chemokine receptors, and the up-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines [including tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin 1β (IL1B), interleukin 6 (IL6)] promote adhesive interactions between leukocytes and endothelial cells, thus leading to large amounts of inflammatory cells transmigrating into infarcted myocardium 29. In the early stage of AMI, neutrophils are recruited to the infarct area within hours after cardiac injury, reaching a peak at day 1-3 and declining to normal level at day 5-7 30. Then M1 macrophages dominate and participate in the phagocytosis of necrotic tissue together with neutrophils. Necrotic or damaged cells and ECM tissue are then digested and cleared, followed by a reparative phase over the next several days. The transition to the reparative phase depends on the timely suppression of the inflammatory response, and anti-inflammatory monocyte subtypes, lymphocytes and anti-inflammatory macrophages may be involved in this period 31. During the reparative phase, neutrophils rapidly undergo cell death, inducing a M2 phenotype conversion in macrophages and secretion of anti-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic cytokines such as IL10 and transforming growth factor beta (TGFB) which suppress inflammation and promote tissue repair. The polarization of macrophages stimulates the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and TGFB and then promotes angiogenesis and ECM synthesis 32. Besides, bone marrow derived DCs infiltrate the necrotic myocardium, predominantly during the reparative phase 33, 34. It seems like the filtration of DCs after AMI can control macrophage homeostasis thus modulating the postinfarction healing process 34. In addition, T cells and mast cells both participate in immune response to varying degree (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Temporal two different phases of inflammatory process after AMI. In inflammatory phase, neutrophils, M1 macrophages and mast cells dominated, accompanied with damaged cells and tissue digestion. During the following reparative phase, macrophages polarized towards anti-inflammatory type, and dendritic cells as well as regulatory T cells both participated in the resolution of inflammation.

The inflammatory process participates in clearing dead cells, facilitating scar formation whereas excessive or prolonged inflammation response leads to degradation of extracellular matrix, resulting in dilative remodeling and HF 35, which makes the process of immune response a novel target for the treatment of AMI and the prevention of HF.

Immune cell-derived exosomes in immunomodulation after AMI

The immune system plays a vital role in pathogens defense, inflammation response, and wound repair. Immune cells predominantly participate in clearing out cell debris, inflammation resolution and healing process post AMI 34, 36. Emerging evidence has indicated that exosomes derived from immune cells are essential in carrying out these functions 37. Exosomes have been increasingly researched and applied to the salvage of ischemic myocardium, from which we can speculate that exosomes from immune cells might become potential alternatives for the treatment of AMI patients.

Exosomes from macrophages

In the infarcted myocardium, two sequential sets of macrophages, namely M1 macrophage and M2 macrophage, dominate in two different phases of inflammatory process after AMI. In inflammatory phase, M1 macrophage, which is proinflammatory type, secretes massive pro-inflammatory mediators. In the reparative phase, M2 macrophage dominates in the infarcted myocardium and facilitates wound repair via myofibroblast activation, angiogenesis and ECM deposition.

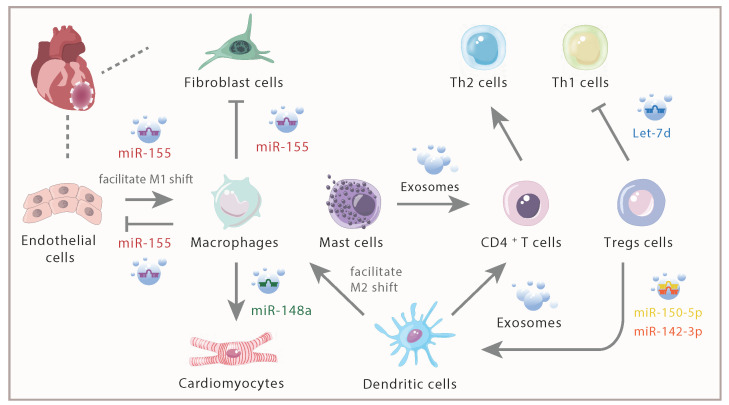

In injured heart, miR-155 derived from activated cardiac macrophages could be transferred into cardiac fibroblasts, thus inhibiting proliferation of fibroblasts, enhancing inflammation with the upregulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFA), IL1B, and C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2 (CCL2), decreasing collagen production and promoting cardiac rupture via targeting Son of Sevenless gene 1 and Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 1 38. Additionally, macrophages were also recipients of miR-155-enriched exosomes from endothelial cells, which further shifted the macrophage balance from anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages towards proinflammatory M1 macrophages 39. Further evidence confirmed that exosomes secreted by pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages exerted an anti-angiogenic effect and accelerated MI injury 40, which partly due to the highly expressed proinflammatory miR-155 contained in those exosomes and led to inhibition of angiogenesis and cardiac dysfunction. On the contrary, M2 macrophage-derived exosomes enhanced the viability of cardiomyocytes and reduced myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury in vivo mainly via highly expressed miR-148a 41. The elevation of miR-148a expression has also been proven to impair B cell tolerance via facilitating the survival of immature B cells by means of downregulating the expression of growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 45 alpha, phosphatase and tensin homolog (Pten) and BCL2-like 11 which encodes the pro-apoptotic factor Bim 42. Therefore, macrophages may be able to regulate immune responses by transferring miRNAs to B cells. Taken together, different contents including miR-155 and miR-148a derived from macrophages could effectively modulate immune response thus providing new targets for the treatment of AMI.

Exosomes from DCs

DCs, pivotal antigen-presenting cells, are key to the immunological response with different functions participating in immunity 43-45. Emerging evidence confirmed that DCs were involved in the pathophysiological mechanisms of various cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis, hypertension and HF 46, 47. In the infarcted myocardium, DCs were vital in recruiting and activating immune cells particularly macrophages and T cells, accompanied by a notably increase of inflammatory cytokines 48. Meanwhile, released EVs of DCs have been reported as an important way of mediating intercellular communication in immunity. Although the majority of studies of DC-derived exosomes focused on immunotherapy against various types of cancer, rising attention has been paid to the role of exosomes derived from DCs in AMI.

After AMI, DCs migrated to the infarction border zone and participated in the activation of lymphocytes and the initiation of immune responses 48, 49. Further study indicated that mice with DCs ablation showed enhanced and sustained expression of inflammatory cytokines (such as IL1B, IL18, and TNFA), prolonged ECM degradation and enhanced proinflammatory M1 macrophage recruitment after AMI 34. Injection of DCs to the infarcted mice induced a systemic activation of MI-specific regulatory T cells (Tregs) and facilitated an M2 macrophage shift, resulting in better wound healing and preserved left ventricular systolic function 50. Furthermore, the injection of exosomes secreted from DCs could directly activate CD4+ T cells through Th1 signaling pathway. Despite that the inflammatory cytokines were upregulated; the injection of exosomes derived from DCs effectively improved the cardiac function of mice post-MI 51. Considering that the activated CD4+ T cells could facilitate wound healing of the myocardium after AMI 36, it is reasonable to speculate that exosomes from DCs might activate CD4+ T cells to exert cardioprotective effects after infarction. But the experiments of Cai et al demonstrated that miR-142-3p enriched in exosomes derived from activated CD4+ T cells (CD4-activated Exos) targeted and inhibited the expression of Adenomatous Polyposis Coli, contributing to the activation of WNT signaling pathway and activation of cardiac fibroblast, thus evoking pro-fibrotic effects of cardiac fibroblasts. And the delivery of CD4-activated Exos into the heart aggravated cardiac fibrosis and caused post-MI dysfunction 52. Therefore, the cardioprotective effects of exosomes secreted from DCs deserve further research.

Exosomes from Tregs

Tregs are a specific subset of T lymphocytes with immunosuppressive effects, which counts 5-10% of CD4+ T cells in human peripheral blood 53. They are essential in enhancing the polarization of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages 54, 55, elevating the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines including IL10, IL4, IL13 and reducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines 54, 56. It has been confirmed that exosomes derived from Tregs could transfer miRNAs especially miR-150-5p and miR-142-3p to DCs accompanied with reduced immune reactions 57. MiR-150 was pivotal in attenuating immune responses of DCs and protecting cardiomyocytes from cell death under conditions of hypoxia 58. Additionally, miR-150 was a critical passive regulator of monocyte cell migration and suppressed pro-inflammatory cytokines production, leading to cardioprotective effects 59. Upregulation of miR-142-3p resulted in shrinking I/R damage-triggered infarct size, strengthening cardiac function and guarding against cardiomyocyte apoptosis 60. Meanwhile, exosomes from Tregs cells could transfer Let-7d to T helper 1 (Th1) cells and suppressed proliferation of Th1 cells and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines 61. Infiltration of Th1 cells led to cardiac fibroblasts activation, then cardiac fibroblasts transformed into myofibroblasts via integrin α4. In addition, Th1 cells induced Tgfb expression in myofibroblasts, which facilitated the formation of fibrillary ECM in the myocardium thus promoting cardiac fibrosis 62. Based on the above research, Tregs-derived exosomes may exhibit its cardioprotective effects by interacting with other immune cells.

Exosomes from mast cells

Mast cells have been directly linked to atherosclerotic plaque rupture which results in acute thrombotic occlusion of the coronary artery and thus leading to AMI 63. The inhibition of chymase secreted by mast cells led to reduced Tgfb expression accompanied with reduced myocardial fibrosis and cardiac dysfunction 64. Interestingly, tryptase secreted by mast cells contributed to the angiogenesis and promoted the healing process in the infarcted myocardium 65. To summarize, mast cells participate not only in the generation of MI but also in the reparative process via its diverse mediators.

A research confirmed that mast cells can exhibit its inflammatory and immunoregulatory functions via exosomes in addition to cell-to-cell contacts and cytokines release 66. The data also indicated that exosomes derived from mast cells were capable of activating B and T lymphocytes, suggesting that exosomes derived from mast cells may participate in the development and the amplification of both the specific and nonspecific inflammatory responses. Exosomes derived from mast cells also could partially promote the proliferation of CD4+ T cells and dramatically enhance the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells to Th2 cells 67, presenting an immunoregulatory effect (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Intercellular communication of immune cells and cardiac inherent cells via exosomes and its contents. In response to AMI, distinct immune cells infiltrated within the infarcted myocardium. Exosomes, with various derivation and different contents, played different roles in inflammation response.

Stem cell-derived exosomes in immunomodulation after AMI

Stem cell transplantation has been recognized as a highly attractive option for the treatment of infarcted myocardium while increasing evidence suggests that its cardioprotective effects mainly depend on paracrine way. Therefore, stem cell-derived exosomes transplantation is considered to be a promising treatment for MI. Besides, compared with endogenous immune cell derived exosomes, exogenous stem cells-derived exosomes are also inseparable from immune regulation. In this part, we mainly focus on exosomes derived from MSCs, cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) and cardiosphere cells (CDCs), and the mechanisms related to their cardioprotective functions are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summarization of the derivation, effective components, mechanisms and biological effects of stem cells-derived exosomes in different pathological status.

| Derivation of exosome | Effective components | Mechanisms | Biological effects | Pathological status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMMSCs | miR-25-3p↑ | miR-25-3p/Ezh2/Socs3 | inflammation↓ apoptosis↓ |

MI | 71 |

| BMMSCs | miR-185↑ | miR-185/Socs2 | inflammation infiltration↓ apoptosis↓ ventricular remolding↓ |

MI | 119 |

| BMMSCs | miR-125b↑ | miR-125b/Sirt7 | IL1B, IL6, and TNFA↓ apoptosis↓ |

I/R | 120 |

| BMMSCs | miR-182↑ | miR-182/Tlr4 | M2 macrophages polarization↑ | I/R | 72 |

| BMMSCs | LncRNA H19↑ | LncRNA H19/miR-675/Vegf and Icam1 | inflammation↓ angiogenesis↑ cardiomyocyte apoptosis↓ infarct size↓ cardiac function↑ |

MI | 74 |

| BMMSCs | LPS pre-conditioning | NFKB signaling pathway AKT1/AKT2 signaling pathway |

M2 macrophages polarization↑ M1 macrophages polarization↓ inflammation↓ |

MI | 73 |

| BMMSCs | ischemic myocardium-targeting peptide↑ | Not investigated | inflammation↓ apoptosis↓ fibrosis↓ vasculogenesis↑ cardiac function↑ |

MI | 75 |

| BMMSCs | indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase↑ | Not investigated | regulatory T-cells↑ CD8+ T-cells↓ pro-inflammatory cytokines↓ anti-inflammatory cytokines↑ allograft-targeting immune responses↓ cardiac allograft function↑ |

heart transplants | 121 |

| BMMSCs | miR-21↓ miR-15↓ |

Not investigated | inflammation↓ cardiac fibrosis↓ cardiac function↑ apoptosis↓ cell proliferation↑ |

AMI | 122 |

| BMMSCs | Not investigated | Not investigated | inflammation↓ neovascularization↑ |

AMI | 76 |

| BMMSCs | Not investigated | JAK2-STAT6 | inflammatory cells infiltration↓ pro-inflammatory macrophages↓ cardiac function↑ cardiac dilation↓ cardiomyocytes apoptosis↓ |

dilated cardiomyopathy | 123 |

| ADMSCs | Hypothermia combination | PI3K/AKT/GSK3B p-m-TOR |

TNFA and IL6↓ IL10↑ oxidative stress↓ apoptosis↓ |

I/R | 124 |

| ADMSCs | Not investigated | S1P/SK1/S1PR1 signaling | inflammatory response↓ M2 macrophages polarization↑ cardiac fibrosis↓ apoptosis↓ |

AMI | 82 |

| ADMSCs | miR-126↑ | Not investigated | inflammation↓ apoptosis↓ fibrosis↓ angiogenesis↑ |

AMI | 81 |

| ADMSCs | Not investigated | Not investigated | M2 macrophages polarization↑ | Pre-activated with inflammatory factors | 83 |

| hucMSCs | miR-181a ↑ | Not investigated Not investigated |

TNFA and IL6↓ IL10↑ |

I/R | 90 |

| hucMSCs | Encapsulated by hydrogel | Not investigated | inflammation↓ apoptosis↓ fibrosis↓ angiogenesis↑ |

AMI | 92 |

| MSCs | LncRNA KLF3-AS1 | LncRNA KLF3-AS1/miR-138-5p/Sirt1 | IL1B and IL18↓ cell apoptosis↓ pyroptosis↓ |

AMI | 125 |

| MSCs | Not investigated | PI3K/AKT Pathway | neutrophil infiltration ↓ macrophage infiltration↓ oxidative stress↓ adverse remodeling↓ |

I/R | 126 |

| CPCs | PAPPA↑ | IGF1/AKT and ERK1/2 | CD68+ macrophages↓ cardiomyocytes apoptosis↓ cardiac function↑ |

AMI | 99 |

| CDCs | miR-181b↑ | miR-181b/ Prkcd | CD68+ macrophage within infarcted tissue↓ Modify polarization of macrophage |

I/R | 106 |

| CDCs (EV) | Y RNA fragment | Not investigated | IL10↑ Infarct size↓ |

I/R | 107 |

| CDCs | Engineered with cardiomyocyte specific peptide | Not investigated | cardiac inflammation↓ fibrosis↓ cardiomyocyte apoptosis↓ cardiac retention↑ |

I/R | 110 |

| ESC | Not investigated | Not investigated | M2 macrophages↑ anti-inflammatory cytokine↑ cardiac remodeling↓ |

Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy | 127 |

miR: miRNA; EZH2: enhancer of zest homologue 2; SOCS: suppressor of cytokine signaling; SIRT7: sirtuin-7; IL1B: interleukin 1 beta; IL6: interleukin 6; TNFA: tumor necrosis factor alpha; TLR4: toll-like receptors 4; LncRNA H19: long non-coding rna h19; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; ICAM1: intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; NFKB: nuclear factor kappa-b; JAK2:Janus kinase 2; STAT6: signal transducer and activator of transcription 6; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; GSK3B: glycogen synthase kinase 3β; p-m-TOR/p-AMKP: phosphorylate-mammalian target of rapamycin/ phosphorylate-adenosine 5'-monophosphate -activated protein kinase; IL10: interleukin 10; S1P/SK1/S1PR1: sphingosine 1-phosphate/sphingosine kinase 1/ sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1; Sirt1: sirtuin-1; IL18: interleukin 18; PAPPA: pregnancy-associated plasma protein a; IGF1: insulin-like growth factors-1; ERK1/2: extracellular regulated protein kinases 1/2; PRKCD: protein kinase c delta.

MSC derived exosomes

MSCs are a group of adult stem cells with self-renewal and differentiation abilities and also immunomodulatory properties, and have been widely used in tissue repair and regeneration 68. They express CD73, CD90, and CD105, and don't express CD45, CD34, CD14, CD19, CD11b, and human leukocyte antigen DR isotype 69. Due to their characteristics of easy isolation, convenient acquisition and low immunogenicity, they have become the most promising stem cell type in the treatment of AMI. According to their original sources, MSCs can be divided into bone marrow derived MSCs (BMMSCs), adipose tissue derived MSCs (ADSCs), umbilical cord derived MSCs (ucMSCs), and so on. The view that main benefits of MSC therapy are derived from secreted factors acting on neighboring cells through paracrine way has already become a widely accepted point 70. As indispensable paracrine substances, exosomes derived from MSCs have proven to show similar effects as MSCs, including anti-apoptosis, promoting angiogenesis, and also immunomodulation in the treatment of AMI.

BMMSC-derived exosomes

Many studies have found that BMMSC-derived exosomes (BMMSC-Exos) can regulate the local inflammatory cytokines in infarcted myocardium. The injection of BMMSC-Exos could greatly repress inflammatory cytokines including IL1B, IL6 and TNFA which were induced by AMI, as well as targeting pro-apoptotic proteins like FASL and PTEN to alleviate MI mainly through miR-25 71. Further studies confirmed that BMMSC-Exos could promote the polarization of M1 macrophages to the M2 macrophages both in vivo and in vitro, thereby alleviating inflammation response. The miRNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis of BMMSC-Exos indicated that miR-182 was a potential candidate mediator for modifying macrophage polarization via targeting Tlr4 72. The immunoregulatory effects of BMMSC-Exos on macrophages can be further enhanced by artificial means including drug pretreatment and gene modification. Xu et al pretreated BMMSCs with low-dose lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and collected the exosomes (L-Exos). L-Exos had superior therapeutic effects on mediating macrophage polarization and further alleviated post-MI inflammation and cardiomyocyte apoptosis 73. Exosomes derived from BMMSCs pretreated with atorvastatin had an elevated level of lncRNA H19 and reduced the inflammatory cytokines with markedly promoting angiogenesis, minimizing infarct size and improving ventricular function post MI 74. Furthermore, engineered exosomes with ischemic myocardium targeting peptide exerted more accumulation in ischemic myocardium and enhanced therapeutic effects on attenuating inflammation and cardiomyocytes apoptosis 75. Meanwhile, BMMSC-Exos impaired T-cell function via inhibiting its proliferation, and also restrained the inflammation response as well as improved cardiac function 76. Until now, there is a lack of research focusing on BMMSC-Exos regulating other immune cells, but studies have shown that DCs could regulate macrophage polarization and the Tregs, and also participated in presenting antigens to T cells to activate CD4+ T cells 50, 51. As the regulation of BMMSC on DCs has been confirmed by many experiments 77, the regulation of DCs by BMMSC-Exos will further improve the understanding of the mechanism of exosomes to regulate immune response after AMI.

ADSCs-derived exosomes

The concentration of MSCs in adipose tissue is notably higher than in bone marrow (1% versus 0.01%) and other sources 78. Compared to the bone marrow, harvesting MSCs from adipose tissue is less invasive and has no ethical limitations 79. Similar to BMMSCs, ADSCs can differentiate into ectodermal, endodermal as well as the mesodermal lineage, and also exhibit immunomodulatory characteristics 80. During the inflammatory phase, M1 macrophage predominant in the infarcted myocardium and proinflammatory cytokines including IL6, IL1B, interferon γ (IFNG) and TNFA are elevated. When treated with exosomes derived from miR-126-overexpressing ADSCs, inflammatory cytokines expression and cardiac fibrosis were notably decreased 81. Further studies indicated that the immunomodulatory effects of ADSCs-derived exosomes might be associated with macrophage polarization. Deng et al. confirmed that ADSCs-derived exosomes treatment effectively promoted macrophage polarization to M2 type, which inhibited inflammatory responses and attenuated myocardial fibrosis by suppressing Nfkb and Tgfb1 expression 82. In addition, exosomes released from ADSCs under stimulation with IFNG and TNFA showed strengthened immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory effects 83.

HucMSCs derived exosomes

Compared with other MSCs, hucMSCs have the characteristics of low cost, low invasiveness, easy isolation, high cell content, high gene transfection efficiency and low immunogenicity, which arouse interests of scientists in tissue repair 84. Exosomes derived from hucMSC (hucMSC-Exos) are promising new treatment options for AMI. MiR-19a could suppress apoptosis of myocardial cells 85 and was detected to be lower in myocardial tissues of AMI compared to normal tissues, while hucMSC-Exos significantly increased the release of miR-19a and attenuated ischemic injury with decreased expression of inflammatory cytokines 86. Additionally, Shi et al. found that on day 2 after AMI, the pro-inflammatory factors were downregulated and anti-inflammatory factors were upregulated in the infarcted myocardial tissue in rats when treated with hucMSC-Exos 87, confirming that hucMSC-Exos were involved in regulating the local immune microenvironment after AMI. Since miR-181a has been confirmed to be associated with inflammatory-related disease 88 and was involved in Tregs activation 89, Wei et al. utilized exosomes derived from miR-181a overexpressing hucMSCs to alleviate the cardiac injury post I/R and they found the exosome treatment created an anti-inflammatory environment, and also increased Tregs polarization 90 which were capable of promoting the conversion of the pro-inflammatory phase to the pro-reparative phase and participating in wound healing through modulating macrophage differentiation 91. When encapsulated in functional peptide hydrogels, hucMSC-Exos exhibited increased retention within the myocardium and showed better immunomodulatory and cardioprotective effects 92. Based on the current limited experimental evidence, we believe that hucMSC-Exos also have strong immunoregulatory abilities, and they are quite promising in the treatment of AMI and deserve further research.

CPC derived exosomes

Progenitor cell is a kind of stem cell that is distinct from embryonic stem cell (ESC) for its predetermined differentiation fate and its limited potential of self-renewal as well as differentiation into other cell types 93. CPCs can differentiate into cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells 94. Although CPCs are considered as quiescent cells in physiological conditions, it is suggested that they can be activated in injury and may differentiate into cardiac cells 95. The translational relevance of CPCs in cardiac therapy has been proven in several studies, and promising results have been obtained in preclinical studies and clinical trials 96.

Studies have pointed out that CPCs have a strong ability to suppress immunity, and this effect is mainly mediated via paracrine way. When co-culture with CPCs, the proliferation of T cell was notably reduced accompanied with strong downregulation of IFNG and TNFA, and EVs play an important role in this process 97. In vivo, soluble junctional adhesion molecule-A in the conditioned medium from CPCs reduced neutrophils infiltration after AMI and reduced tissue damage by preventing excessive inflammation 98. Proteomics analysis demonstrated that pregnancy-related plasma protein A is one of the highest contents of CPC-derived exosomes in comparison to BMMSC-Exo, while the injection of CPC-derived exosomes exhibited less CD68+ macrophage infiltration, reflecting its immunomodulatory effects 99.

CDC derived exosomes

CDCs are a group of CPCs that have the ability to motivate endogenous mechanisms of cardiac repair and attenuate adverse ventricular remodeling 100, and also have been proven to improve cardiac function in a variety of heart diseases 101. CDC-derived exosomes (CDC-Exos) could also mitigate the myocardium damage caused by AMI, having the ability to relieve oxidative stress, reduce cell apoptosis and adverse ventricular remodeling, and facilitate angiogenesis after MI 102-105. Meanwhile, several experiments have demonstrated the immunoregulatory effects of CDC-Exos within the infarcted myocardium. Administration of CDC-Exos modified the polarization to M2 macrophage phenotype and enhanced the endogenous phagocytic capacity of macrophage, thus promoting the clearance of necrotic cell debris and also relieving excessive proinflammatory stress within the infarcted heart, facilitating the recovery of cardiac function after AMI. In this process, the highly expressed miR-181b in CDC-Exos which acted as a significant candidate mediator of CDC-induced macrophage polarization exerted its downstream functions by targeting protein kinase C delta (Prkcd) 106. Moreover, the high abundance of Y RNA fragment in EVs derived from CDCs could target macrophages and then enhanced IL10 protein secretion which could stimulate monocytes and prevent excessive inflammatory reactions 107, 108. CDC-derived EVs were also found to be involved in polarizing M1 macrophage to a proangiogenic phenotype through the upregulation of arginase 1 109. Besides, engineered CDCs with cardiomyocyte specific peptide endowed the exosomes with better targeting and retention ability and also superior immunoregulatory effects 110.

ESCs and induced pluripotent stem cells are regarded as highly attractive methods for the treatment of AMI. Their exosomes also have similar therapeutic effects 105, 111, 112, but specific studies focused on immunomodulation are still scarce.

Conclusions and Perspectives

The inflammatory response mediated by various immune cells as well as inflammatory factors play vital roles in the process of myocardial necrosis and repair after AMI. Excessive inflammation response or improper suppression of inflammation may both affect the myocardial repair, leading to ventricular remodeling, and deterioration of heart function and development of HF after AMI. As important mediators of cell communication, exosomes are crucial in regulating immune cells and immune responses after AMI, facilitating the reparative process of infarcted myocardium, preserving ventricular function via the communication between lymphocytes or between lymphocytes and cardiac intrinsic cells. Systemic deliveries of exosomes derived from immune cells have gradually been recognized as a potent new therapeutic option for the treatment of MI-damaged myocardium. Moreover, stem cell-derived exosomes also have powerful immunomodulatory and inflammation inhibitory effects. They can act by directly targeting inflammatory cells or regulating inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, exosomes from both endogenous immune cells and exogenous stem cells are potential therapeutic strategies, which are promising for the treatment of AMI and worthy of further research for improving the prognosis of patients with AMI. Additionally, exosomes hold great potential of being therapeutic drug delivery vesicles due to its natural material transportation properties and excellent biocompatibility characteristics. Well-designed engineered exosomes may provide opportunities to enhance its therapeutic effects, making it promising and inspiring tools for clinical use 113. For example, conjugating the exosomes derived from CDCs with cardiac homing peptide effectively enhanced its therapeutic efficacy in cardiac repair and decreased the effective dose of intravenously delivery 114.

Derived from various cells, the heterogeneity of exosome sizes and contents is capable of reflecting the state and types of origin, making exosomes possible biomarkers for disease diagnostics 115. For example, exosomes containing miR-24 and miR-210 changed significantly correlated well with cTNI levels in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting surgery, suggesting the potential role for exosomes as new biomarkers of myocardial injury 116. Circulating exosomes enriched in p53-responsive miRNAs including miR-34a, miR-192 and miR-194 have also been identified as prognostic biomarkers of MI 117. Although researches related to the application of exosomes derived from immune cells in cardiovascular diseases are scarce for now, circulating EVs derived from immune cells can act as biomarkers of other inflammation related diseases including chronic hepatitis C and nonalcoholic fatty liver 118. It is worthy of expecting that the identification of novel biomarkers from immune cell-derived exosomes will grow rapidly.

In conclusion, exosomes are emerging as important mediators of intercellular communication and exosomes derived from immune cells and stem cells are pivotal therapeutic tools in the treatment of AMI. Moreover, advanced modification strategies and detection methods in exosomes will provide us with great tools as therapeutic interventions and biomarkers for AMI. Considering the potential of being new generation of bio-nano drugs, exosomes have advantages in the field of cell-free therapy for cardiac repair post AMI as well as other diseases, and might produce enormous social and economic benefits.

Acknowledgments

Writing this review was supported by grants from CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (grant number 2016-12M-1-009), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No.2017YFC1700503), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81573957, No.81874461 and No.82070307).

Abbreviations

- AMI

acute myocardial infarction

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- HF

heart failure

- MI

myocardial infarction

- EV

extracellular vesicles

- DC

dendritic cell

- MSC

mesenchymal stromal cell

- MVB

multivesicular body

- ILV

intraluminal vesicle

- DAMP

danger-associated molecular pattern

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- IL1R

interleukin-1 receptor

- IL1B

interleukin 1β

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TNFA

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- IL

interleukin

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- TGFB

transforming growth factor beta

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- CCL2

c-c motif chemokine ligand 2

- I/R

ischemia/reperfusion

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- IFNG

interferon-γ

- Treg

regulatory T cell

- Th1

T helper 1

- CD4-activated Exos

exosomes derived from activated CD4+ T cells

- CPC

cardiac progenitor cell

- CDC

cardiosphere cell

- ESC

embryonic stem cell

- BMMSC

bone marrow derived MSCs

- ADSC

adipose tissue derived MSCs

- ucMSC

umbilical cord derived MSCs

- BMMSC-Exo

BMMSC-derived exosomes

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- hucMSC-Exos

hucMSC-derived exosomes

- CDC-Exos

CDC-derived exosomes

- PRKCD

protein kinase c delta

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP. et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abyu G. et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases for 10 Causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ong SB, Hernández-Reséndiz S, Crespo-Avilan GE, Mukhametshina RT, Kwek XY, Cabrera-Fuentes HA. et al. Inflammation following acute myocardial infarction: Multiple players, dynamic roles, and novel therapeutic opportunities. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;186:73–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frangogiannis NG. Regulation of the inflammatory response in cardiac repair. Circ Res. 2012;110:159–73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins PD, Morelli AE. Regulation of immune responses by extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:195–208. doi: 10.1038/nri3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaput N, Théry C. Exosomes: immune properties and potential clinical implementations. Semin Immunopathol. 2011;33:419–40. doi: 10.1007/s00281-010-0233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barile L, Moccetti T, Marbán E, Vassalli G. Roles of exosomes in cardioprotection. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:1372–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung M, Dodsworth M, Thum T. Inflammatory cells and their non-coding RNAs as targets for treating myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol. 2018;114:4. doi: 10.1007/s00395-018-0712-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wysoczynski M, Khan A, Bolli R. New Paradigms in Cell Therapy: Repeated Dosing, Intravenous Delivery, Immunomodulatory Actions, and New Cell Types. Circ Res. 2018;123:138–58. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pegtel DM, Gould SJ. Exosomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2019;88:487–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-111902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin J, Li J, Huang B, Liu J, Chen X, Chen XM. et al. Exosomes: novel biomarkers for clinical diagnosis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2015;2015:657086. doi: 10.1155/2015/657086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Théry C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:569–79. doi: 10.1038/nri855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai RC, Arslan F, Lee MM, Sze NS, Choo A, Chen TS. et al. Exosome secreted by MSC reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res. 2010;4:214–22. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367:eaau6977. doi: 10.1126/science.aau6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurunathan S, Kang MH, Jeyaraj M, Qasim M, Kim JH. Review of the Isolation, Characterization, Biological Function, and Multifarious Therapeutic Approaches of Exosomes. Cells. 2019;8:307. doi: 10.3390/cells8040307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, Sjöstrand M, Lee JJ, Lötvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:654–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montecalvo A, Larregina AT, Shufesky WJ, Stolz DB, Sullivan ML, Karlsson JM. et al. Mechanism of transfer of functional microRNAs between mouse dendritic cells via exosomes. Blood. 2012;119:756–66. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parolini I, Federici C, Raggi C, Lugini L, Palleschi S, De Milito A. et al. Microenvironmental pH is a key factor for exosome traffic in tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34211–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ribeiro-Rodrigues TM, Laundos TL, Pereira-Carvalho R, Batista-Almeida D, Pereira R, Coelho-Santos V. et al. Exosomes secreted by cardiomyocytes subjected to ischaemia promote cardiac angiogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113:1338–50. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Balkom BW, de Jong OG, Smits M, Brummelman J, den Ouden K, de Bree PM. et al. Endothelial cells require miR-214 to secrete exosomes that suppress senescence and induce angiogenesis in human and mouse endothelial cells. Blood. 2013;121:3997–4006. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-478925. s1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prabhu SD, Frangogiannis NG. The Biological Basis for Cardiac Repair After Myocardial Infarction: From Inflammation to Fibrosis. Circ Res. 2016;119:91–112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin L, Knowlton AA. Innate immunity and cardiomyocytes in ischemic heart disease. Life Sci. 2014;100:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.01.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timmers L, Pasterkamp G, de Hoog VC, Arslan F, Appelman Y, de Kleijn DP. The innate immune response in reperfused myocardium. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;94:276–83. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arslan F, de Kleijn DP, Pasterkamp G. Innate immune signaling in cardiac ischemia. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:292–300. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Haan JJ, Smeets MB, Pasterkamp G, Arslan F. Danger signals in the initiation of the inflammatory response after myocardial infarction. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:206039. doi: 10.1155/2013/206039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghigo A, Franco I, Morello F, Hirsch E. Myocyte signalling in leucocyte recruitment to the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;102:270–80. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mann DL. The emerging role of innate immunity in the heart and vascular system: for whom the cell tolls. Circ Res. 2011;108:1133–45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newton K, Dixit VM. Signaling in innate immunity and inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a006049. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frangogiannis NG. The immune system and cardiac repair. Pharmacol Res. 2008;58:88–111. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma Y, Yabluchanskiy A, Lindsey ML. Neutrophil roles in left ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2013;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frangogiannis NG. The inflammatory response in myocardial injury, repair, and remodelling. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:255–65. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK, Aikawa E, Stangenberg L, Wurdinger T, Figueiredo JL. et al. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3037–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan X, Anzai A, Katsumata Y, Matsuhashi T, Ito K, Endo J. et al. Temporal dynamics of cardiac immune cell accumulation following acute myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;62:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anzai A, Anzai T, Nagai S, Maekawa Y, Naito K, Kaneko H. et al. Regulatory role of dendritic cells in postinfarction healing and left ventricular remodeling. Circulation. 2012;125:1234–45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.052126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christia P, Frangogiannis NG. Targeting inflammatory pathways in myocardial infarction. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013;43:986–95. doi: 10.1111/eci.12118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hofmann U, Beyersdorf N, Weirather J, Podolskaya A, Bauersachs J, Ertl G. et al. Activation of CD4+ T lymphocytes improves wound healing and survival after experimental myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation. 2012;125:1652–63. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.044164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu R, Gao W, Yao K, Ge J. Roles of Exosomes Derived From Immune Cells in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:648. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang C, Zhang C, Liu L, A X, Chen B, Li Y. et al. Macrophage-Derived mir-155-Containing Exosomes Suppress Fibroblast Proliferation and Promote Fibroblast Inflammation during Cardiac Injury. Mol Ther. 2017;25:192–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He S, Wu C, Xiao J, Li D, Sun Z, Li M. Endothelial extracellular vesicles modulate the macrophage phenotype: Potential implications in atherosclerosis. Scand J Immunol. 2018;87:e12648. doi: 10.1111/sji.12648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu S, Chen J, Shi J, Zhou W, Wang L, Fang W. et al. M1-like macrophage-derived exosomes suppress angiogenesis and exacerbate cardiac dysfunction in a myocardial infarction microenvironment. Basic Res Cardiol. 2020;115:22. doi: 10.1007/s00395-020-0781-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dai Y, Wang S, Chang S, Ren D, Shali S, Li C. et al. M2 macrophage-derived exosomes carry microRNA-148a to alleviate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via inhibiting TXNIP and the TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2020;142:65–79. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2020.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonzalez-Martin A, Adams BD, Lai M, Shepherd J, Salvador-Bernaldez M, Salvador JM. et al. The microRNA miR-148a functions as a critical regulator of B cell tolerance and autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:433–40. doi: 10.1038/ni.3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–52. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pulendran B, Tang H, Manicassamy S. Programming dendritic cells to induce T(H)2 and tolerogenic responses. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:647–55. doi: 10.1038/ni.1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ. et al. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Worbs T, Hammerschmidt SI, Förster R. Dendritic cell migration in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:30–48. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dieterlen MT, John K, Reichenspurner H, Mohr FW, Barten MJ. Dendritic Cells and Their Role in Cardiovascular Diseases: A View on Human Studies. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:5946807. doi: 10.1155/2016/5946807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kretzschmar D, Betge S, Windisch A, Pistulli R, Rohm I, Fritzenwanger M. et al. Recruitment of circulating dendritic cell precursors into the infarcted myocardium and pro-inflammatory response in acute myocardial infarction. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;123:387–98. doi: 10.1042/CS20110561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang J, Yu ZX, Fujita S, Yamaguchi ML, Ferrans VJ. Interstitial dendritic cells of the rat heart. Quantitative and ultrastructural changes in experimental myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1993;87:909–20. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.3.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choo EH, Lee JH, Park EH, Park HE, Jung NC, Kim TH. et al. Infarcted Myocardium-Primed Dendritic Cells Improve Remodeling and Cardiac Function After Myocardial Infarction by Modulating the Regulatory T Cell and Macrophage Polarization. Circulation. 2017;135:1444–57. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu H, Gao W, Yuan J, Wu C, Yao K, Zhang L. et al. Exosomes derived from dendritic cells improve cardiac function via activation of CD4(+) T lymphocytes after myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;91:123–33. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cai L, Chao G, Li W, Zhu J, Li F, Qi B. et al. Activated CD4(+) T cells-derived exosomal miR-142-3p boosts post-ischemic ventricular remodeling by activating myofibroblast. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:7380–96. doi: 10.18632/aging.103084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang YM, Alexander SI. IL-2/anti-IL-2 complex: a novel strategy of in vivo regulatory T cell expansion in renal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1503–4. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013070718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tiemessen MM, Jagger AL, Evans HG, van Herwijnen MJ, John S, Taams LS. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce alternative activation of human monocytes/macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19446–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706832104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hu H, Wu J, Cao C, Ma L. Exosomes derived from regulatory T cells ameliorate acute myocardial infarction by promoting macrophage M2 polarization. IUBMB life. 2020 doi: 10.1002/iub.2364. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weirather J, Hofmann UD, Beyersdorf N, Ramos GC, Vogel B, Frey A. et al. Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells improve healing after myocardial infarction by modulating monocyte/macrophage differentiation. Circ Res. 2014;115:55–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tung SL, Boardman DA, Sen M, Letizia M, Peng Q, Cianci N. et al. Regulatory T cell-derived extracellular vesicles modify dendritic cell function. Sci Rep. 2018;8:6065. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24531-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu J, Yao K, Guo J, Shi H, Ma L, Wang Q. et al. miR-181a and miR-150 regulate dendritic cell immune inflammatory responses and cardiomyocyte apoptosis via targeting JAK1-STAT1/c-Fos pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:2884–95. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu Z, Ye P, Wang S, Wu J, Sun Y, Zhang A. et al. MicroRNA-150 protects the heart from injury by inhibiting monocyte accumulation in a mouse model of acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2015;8:11–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.000598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao Z, Qu F, Liu R, Xia Y. Differential expression of miR-142-3p protects cardiomyocytes from myocardial ischemia-reperfusion via TLR4/NFkB axis. J Cell Biochem. 2019 doi: 10.1002/jcb.29506. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Okoye IS, Coomes SM, Pelly VS, Czieso S, Papayannopoulos V, Tolmachova T. et al. MicroRNA-containing T-regulatory-cell-derived exosomes suppress pathogenic T helper 1 cells. Immunity. 2014;41:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nevers T, Salvador AM, Velazquez F, Ngwenyama N, Carrillo-Salinas FJ, Aronovitz M. et al. Th1 effector T cells selectively orchestrate cardiac fibrosis in nonischemic heart failure. J Exp Med. 2017;214:3311–29. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaartinen M, Penttilä A, Kovanen PT. Accumulation of activated mast cells in the shoulder region of human coronary atheroma, the predilection site of atheromatous rupture. Circulation. 1994;90:1669–78. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.4.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kanemitsu H, Takai S, Tsuneyoshi H, Nishina T, Yoshikawa K, Miyazaki M. et al. Chymase inhibition prevents cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction after myocardial infarction in rats. Hypertens Res. 2006;29:57–64. doi: 10.1291/hypres.29.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Somasundaram P, Ren G, Nagar H, Kraemer D, Mendoza L, Michael LH. et al. Mast cell tryptase may modulate endothelial cell phenotype in healing myocardial infarcts. J Pathol. 2005;205:102–11. doi: 10.1002/path.1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Skokos D, Le Panse S, Villa I, Rousselle JC, Peronet R, David B. et al. Mast cell-dependent B and T lymphocyte activation is mediated by the secretion of immunologically active exosomes. J Immunol. 2001;166:868–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li F, Wang Y, Lin L, Wang J, Xiao H, Li J. et al. Mast Cell-Derived Exosomes Promote Th2 Cell Differentiation via OX40L-OX40 Ligation. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:3623898. doi: 10.1155/2016/3623898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Song N, Scholtemeijer M, Shah K. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Immunomodulation: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2020;41:653–664. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D. et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–7. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sid-Otmane C, Perrault LP, Ly HQ. Mesenchymal stem cell mediates cardiac repair through autocrine, paracrine and endocrine axes. J Transl Med. 2020;18:336. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02504-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peng Y, Zhao JL, Peng ZY, Xu WF, Yu GL. Exosomal miR-25-3p from mesenchymal stem cells alleviates myocardial infarction by targeting pro-apoptotic proteins and EZH2. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:317. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2545-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhao J, Li X, Hu J, Chen F, Qiao S, Sun X. et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes attenuate myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury through miR-182-regulated macrophage polarization. Cardiovasc Res. 2019;115:1205–16. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu R, Zhang F, Chai R, Zhou W, Hu M, Liu B. et al. Exosomes derived from pro-inflammatory bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells reduce inflammation and myocardial injury via mediating macrophage polarization. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:7617–31. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huang P, Wang L, Li Q, Tian X, Xu J, Xu J. et al. Atorvastatin enhances the therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes in acute myocardial infarction via up-regulating long non-coding RNA H19. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:353–67. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang X, Chen Y, Zhao Z, Meng Q, Yu Y, Sun J. et al. Engineered Exosomes With Ischemic Myocardium-Targeting Peptide for Targeted Therapy in Myocardial Infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008737. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Teng X, Chen L, Chen W, Yang J, Yang Z, Shen Z. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Improve the Microenvironment of Infarcted Myocardium Contributing to Angiogenesis and Anti-Inflammation. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;37:2415–24. doi: 10.1159/000438594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vadivel S, Vincent P, Sekaran S, Visaga Ambi S, Muralidar S, Selvaraj V. et al. Inflammation in myocardial injury- Stem cells as potential immunomodulators for myocardial regeneration and restoration. Life Sci. 2020;250:117582. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Câmara DAD, Shibli JA, Müller EA, De-Sá-Junior PL, Porcacchia AS, Blay A. et al. Adipose Tissue-Derived Stem Cells: The Biologic Basis and Future Directions for Tissue Engineering. Materials (Basel) 2020;13:3210. doi: 10.3390/ma13143210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Orbay H, Tobita M, Mizuno H. Mesenchymal stem cells isolated from adipose and other tissues: basic biological properties and clinical applications. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:461718. doi: 10.1155/2012/461718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li CY, Wu XY, Tong JB, Yang XX, Zhao JL, Zheng QF. et al. Comparative analysis of human mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and adipose tissue under xeno-free conditions for cell therapy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:55. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0066-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Luo Q, Guo D, Liu G, Chen G, Hang M, Jin M. Exosomes from MiR-126-Overexpressing Adscs Are Therapeutic in Relieving Acute Myocardial Ischaemic Injury. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;44:2105–16. doi: 10.1159/000485949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Deng S, Zhou X, Ge Z, Song Y, Wang H, Liu X. et al. Exosomes from adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate cardiac damage after myocardial infarction by activating S1P/SK1/S1PR1 signaling and promoting macrophage M2 polarization. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2019;114:105564. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2019.105564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Domenis R, Cifù A, Quaglia S, Pistis C, Moretti M, Vicario A. et al. Pro inflammatory stimuli enhance the immunosuppressive functions of adipose mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes. Sci Rep. 2018;8:13325. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31707-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hoffmann A, Floerkemeier T, Melzer C, Hass R. Comparison of in vitro-cultivation of human mesenchymal stroma/stem cells derived from bone marrow and umbilical cord. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2017;11:2565–81. doi: 10.1002/term.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ma Z, Lan YH, Liu ZW, Yang MX, Zhang H, Ren JY. MiR-19a suppress apoptosis of myocardial cells in rats with myocardial ischemia/reperfusion through PTEN/Akt/P-Akt signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:3322–30. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202003_20700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Huang L, Yang L, Ding Y, Jiang X, Xia Z, You Z. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes transfers microRNA-19a to protect cardiomyocytes from acute myocardial infarction by targeting SOX6. Cell Cycle. 2020;19:339–53. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2019.1711305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shi Y, Yang Y, Guo Q, Gao Q, Ding Y, Wang H. et al. Exosomes Derived from Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Fibroblast-to-Myofibroblast Differentiation in Inflammatory Environments and Benefit Cardioprotective Effects. Stem Cells Dev. 2019;28:799–811. doi: 10.1089/scd.2018.0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ghorbani S, Talebi F, Chan WF, Masoumi F, Vojgani M, Power C. et al. MicroRNA-181 Variants Regulate T Cell Phenotype in the Context of Autoimmune Neuroinflammation. Front Immunol. 2017;8:758. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ghorbani S, Talebi F, Ghasemi S, Jahanbazi Jahan Abad A, Vojgani M, Noorbakhsh F. miR-181 interacts with signaling adaptor molecule DENN/MADD and enhances TNF-induced cell death. PloS One. 2017;12:e0174368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wei Z, Qiao S, Zhao J, Liu Y, Li Q, Wei Z. et al. miRNA-181a over-expression in mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes influenced inflammatory response after myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Life Sci. 2019;232:116632. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kino T, Khan M, Mohsin S. The Regulatory Role of T Cell Responses in Cardiac Remodeling Following Myocardial Infarction. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:5013. doi: 10.3390/ijms21145013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Han C, Zhou J, Liang C, Liu B, Pan X, Zhang Y. et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell derived exosomes encapsulated in functional peptide hydrogels promote cardiac repair. Biomater Sci. 2019;7:2920–33. doi: 10.1039/c9bm00101h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Birket MJ, Mummery CL. Pluripotent stem cell derived cardiovascular progenitors-a developmental perspective. Dev Biol. 2015;400:169–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Barreto S, Hamel L, Schiatti T, Yang Y, George V. Cardiac Progenitor Cells from Stem Cells: Learning from Genetics and Biomaterials. Cells. 2019;8:1536. doi: 10.3390/cells8121536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rezaie J, Rahbarghazi R, Pezeshki M, Mazhar M, Yekani F, Khaksar M. et al. Cardioprotective role of extracellular vesicles: A highlight on exosome beneficial effects in cardiovascular diseases. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:21732–45. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pagano F, Picchio V, Angelini F, Iaccarino A, Peruzzi M, Cavarretta E. et al. The Biological Mechanisms of Action of Cardiac Progenitor Cell Therapy. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2018;20:84. doi: 10.1007/s11886-018-1031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.van den Akker F, Vrijsen KR, Deddens JC, Buikema JW, Mokry M, van Laake LW. et al. Suppression of T cells by mesenchymal and cardiac progenitor cells is partly mediated via extracellular vesicles. Heliyon. 2018;4:e00642. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liu M-L, Nagai T, Tokunaga M, Iwanaga K, Matsuura K, Takahashi T. et al. Anti-inflammatory peptides from cardiac progenitors ameliorate dysfunction after myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001101. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Barile L, Cervio E, Lionetti V, Milano G, Ciullo A, Biemmi V. et al. Cardioprotection by cardiac progenitor cell-secreted exosomes: role of pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A. Cardiovasc Res. 2018;114:992–1005. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sousonis V, Nanas J, Terrovitis J. Cardiosphere-derived progenitor cells for myocardial repair following myocardial infarction. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:2003–11. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dutton LC, Dudhia J, Catchpole B, Hodgkiss-Geere H, Werling D, Connolly DJ. Cardiosphere-derived cells suppress allogeneic lymphocytes by production of PGE2 acting via the EP4 receptor. Sci Rep. 2018;8:13351. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31569-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lang JK, Young RF, Ashraf H, Canty JM Jr. Inhibiting Extracellular Vesicle Release from Human Cardiosphere Derived Cells with Lentiviral Knockdown of nSMase2 Differentially Effects Proliferation and Apoptosis in Cardiomyocytes, Fibroblasts and Endothelial Cells In Vitro. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gallet R, Dawkins J, Valle J, Simsolo E, de Couto G, Middleton R. et al. Exosomes secreted by cardiosphere-derived cells reduce scarring, attenuate adverse remodelling, and improve function in acute and chronic porcine myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:201–11. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Namazi H, Mohit E, Namazi I, Rajabi S, Samadian A, Hajizadeh-Saffar E. et al. Exosomes secreted by hypoxic cardiosphere-derived cells enhance tube formation and increase pro-angiogenic miRNA. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:4150–60. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Namazi H, Namazi I, Ghiasi P, Ansari H, Rajabi S, Hajizadeh-Saffar E. et al. Exosomes Secreted by Normoxic and Hypoxic Cardiosphere-derived Cells Have Anti-apoptotic Effect. Iran J Pharm Res. 2018;17:377–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.de Couto G, Gallet R, Cambier L, Jaghatspanyan E, Makkar N, Dawkins JF. et al. Exosomal MicroRNA Transfer Into Macrophages Mediates Cellular Postconditioning. Circulation. 2017;136:200–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cambier L, de Couto G, Ibrahim A, Echavez AK, Valle J, Liu W. et al. Y RNA fragment in extracellular vesicles confers cardioprotection via modulation of IL-10 expression and secretion. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9:337–52. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ouyang W, Rutz S, Crellin NK, Valdez PA, Hymowitz SG. Regulation and functions of the IL-10 family of cytokines in inflammation and disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:71–109. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mentkowski KI, Mursleen A, Snitzer JD, Euscher LM, Lang JK. CDC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Reprogram Inflammatory Macrophages to an Arginase 1-Dependent Pro-Angiogenic Phenotype. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2020;318:H1447–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00155.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mentkowski KI, Lang JK. Exosomes Engineered to Express a Cardiomyocyte Binding Peptide Demonstrate Improved Cardiac Retention in Vivo. Sci Rep. 2019;9:10041. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46407-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Khan M, Nickoloff E, Abramova T, Johnson J, Verma SK, Krishnamurthy P. et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived exosomes promote endogenous repair mechanisms and enhance cardiac function following myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2015;117:52–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ong SG, Lee WH, Zhou Y, Wu JC. Mining Exosomal MicroRNAs from Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells-Derived Cardiomyocytes for Cardiac Regeneration. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1733:127–36. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7601-0_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Liu C, Su C. Design strategies and application progress of therapeutic exosomes. Theranostics. 2019;9:1015–28. doi: 10.7150/thno.30853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Vandergriff A, Huang K, Shen D, Hu S, Hensley MT, Caranasos TG. et al. Targeting regenerative exosomes to myocardial infarction using cardiac homing peptide. Theranostics. 2018;8:1869–78. doi: 10.7150/thno.20524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.He C, Zheng S, Luo Y, Wang B. Exosome Theranostics: Biology and Translational Medicine. Theranostics. 2018;8:237–55. doi: 10.7150/thno.21945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Emanueli C, Shearn AI, Laftah A, Fiorentino F, Reeves BC, Beltrami C. et al. Coronary Artery-Bypass-Graft Surgery Increases the Plasma Concentration of Exosomes Carrying a Cargo of Cardiac MicroRNAs: An Example of Exosome Trafficking Out of the Human Heart with Potential for Cardiac Biomarker Discovery. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Matsumoto S, Sakata Y, Suna S, Nakatani D, Usami M, Hara M. et al. Circulating p53-responsive microRNAs are predictive indicators of heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2013;113:322–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wen C, Seeger RC, Fabbri M, Wang L, Wayne AS, Jong AY. Biological roles and potential applications of immune cell-derived extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2017;6:1400370. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2017.1400370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Li Y, Zhou J, Zhang O, Wu X, Guan X, Xue Y. et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomal microRNA-185 represses ventricular remolding of mice with myocardial infarction by inhibiting SOCS2. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;80:106156. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.106156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chen Q, Liu Y, Ding X, Li Q, Qiu F, Wang M. et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-secreted exosomes carrying microRNA-125b protect against myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury via targeting SIRT7. Mol Cell Biochem. 2020;465:103–14. doi: 10.1007/s11010-019-03671-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.He J-G, Xie Q-L, Li B-B, Zhou L, Yan D. Exosomes Derived from IDO1-Overexpressing Rat Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Immunotolerance of Cardiac Allografts. Cell Transplant. 2018;27:1657–83. doi: 10.1177/0963689718805375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Shao L, Zhang Y, Lan B, Wang J, Zhang Z, Zhang L. et al. MiRNA-Sequence Indicates That Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Exosomes Have Similar Mechanism to Enhance Cardiac Repair. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:4150705. doi: 10.1155/2017/4150705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sun X, Shan A, Wei Z, Xu B. Intravenous mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes ameliorate myocardial inflammation in the dilated cardiomyopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;503:2611–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Chai HT, Sheu JJ, Chiang JY, Shao PL, Wu SC, Chen YL. et al. Early administration of cold water and adipose derived mesenchymal stem cell derived exosome effectively protects the heart from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11:5375–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mao Q, Liang X-L, Zhang C-L, Pang Y-H, Lu Y-X. LncRNA KLF3-AS1 in human mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes ameliorates pyroptosis of cardiomyocytes and myocardial infarction through miR-138-5p/Sirt1 axis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:393. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1522-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Arslan F, Lai RC, Smeets MB, Akeroyd L, Choo A, Aguor EN. et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes increase ATP levels, decrease oxidative stress and activate PI3K/Akt pathway to enhance myocardial viability and prevent adverse remodeling after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res. 2013;10:301–12. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Singla DK, Johnson TA, Tavakoli Dargani Z. Exosome Treatment Enhances Anti-Inflammatory M2 Macrophages and Reduces Inflammation-Induced Pyroptosis in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy. Cells. 2019;8:1224. doi: 10.3390/cells8101224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]