Abstract

This study uses commercial and Medicare Advantage claims data to compare medication fills, outpatient visits, and urine tests for opioid use disorder in January-May 2020 vs 2019.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has complicated the US response to the opioid use disorder (OUD) epidemic. Multiple stressors, including social isolation and unemployment, may have contributed to increased opioid use and overdoses.1 Meanwhile, outpatient visits have declined,2 raising concerns that patients receiving OUD treatment before the pandemic are no longer receiving the same level of services and that fewer patients may be starting treatment.

There has also been a rapid increase in telemedicine use, facilitated by expanded reimbursement and regulatory waivers, including the requirement for an in-person visit before a clinician can prescribe certain OUD medications (eg, buprenorphine).3 The extent to which telemedicine has changed access to OUD care is unclear.

We examined OUD treatment during the early months of the pandemic, including medication fills, outpatient visits, and urine tests, among privately insured individuals compared with 2019.

Methods

We analyzed data from OptumLabs Data Warehouse,4 which includes claims for commercial and Medicare Advantage enrollees who are overrepresented in the South and Midwest (eTable in the Supplement), for individuals aged 18 to 64 years continuously enrolled with medical, behavioral health, and pharmacy benefits from January through May in 2020 and in 2019. We divided these cohorts into patients already receiving OUD medication (ie, had a fill in January/February) and patients not already receiving it (no fill in January/February).

Outcomes for March through May were the weekly and cumulative percentages with (1) at least 1 OUD medication prescription or facility/clinician administration, (2) at least 1 OUD visit, and (3) at least 1 urine OUD toxicology test (eAppendix in the Supplement). We calculated the differences (with 95% CIs) between 2019 and 2020 percentages (Microsoft Excel for Office 365). Significance was defined as a confidence interval excluding 0. We also examined the proportion of weekly OUD visits delivered via telemedicine among patients with at least 1 OUD visit.

This study was deemed exempt from review by Harvard Medical School’s institutional review board. Informed consent was not obtained for this secondary data analysis.

Results

Enrollee demographics were similar for 2019 vs 2020 (eg, mean age, 42 years; 50% female). Among those continuously enrolled in January and February 2020, 92.78% remained enrolled through May (vs 93.44% in 2019); 7.15% were enrolled in Medicare Advantage.

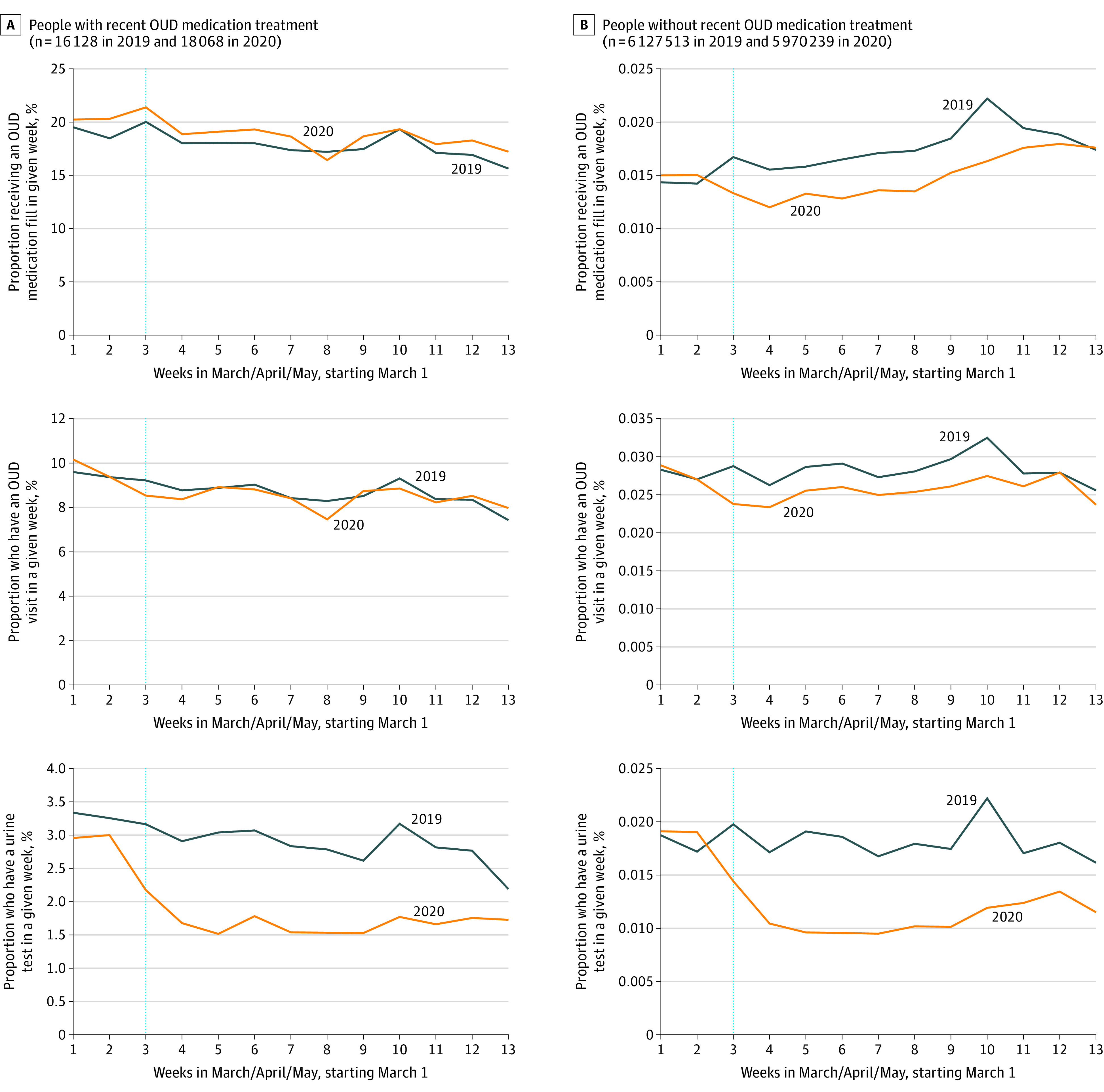

Among individuals already receiving OUD medication (n = 16 128, with 74.47% using buprenorphine, in 2019; n = 18 068, with 74.19% using buprenorphine, in 2020), more filled at least 1 OUD prescription in March through May 2020 than in March through May 2019 (67.99% vs 65.37%; difference, –2.62% [95% CI, –3.62% to –1.62%]) (Figure and Table). The percentage receiving at least 1 OUD visit in March through May was not significantly different in 2020 and 2019 (26.85% vs 27.20%; difference, 0.35% [95% CI, –0.59% to 1.30%]); the percentage receiving at least 1 urine test was lower in 2020 than 2019 (10.56% vs 13.81%; difference, 3.25% [95% CI, 2.55%-3.94%]). In 2020, OUD visits delivered via telemedicine increased from 0.48% in week 1 (week of March 1) to 23.53% in week 13.

Figure. Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) Medical Fills, OUD Visits, and Urine Tests in March Through May of 2019 and 2020.

This study uses 2019 and 2020 claims data from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse. The panels include individuals who were continuously enrolled in medical, behavioral health, and pharmacy benefits for January through May of the year in question. The dotted vertical line corresponds to the date of Medicare’s announced expanded telehealth coverage for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on March 17, 2020 (week 3). Recent OUD medication treatment is defined as at least 1 OUD medication fill in January or February of a given year. Among those with recent OUD medication treatment in 2020, OUD visits delivered via telemedicine increased from 0.48% in week 1 to 23.53% in week 13. Among those without recent OUD medication treatment, OUD visits delivered via telemedicine increased from 0.60% in week 1 of 2020 to 31.82% in week 13.

Table. Receipt of OUD-Related Care for March Through May 2019 vs March Through May 2020a.

| Cumulative No. (%) receiving OUD-related care, March-May | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receiving recent OUD medication treatment | Not receiving recent OUD medication treatment | |||||

| 2019 (n = 16 128) | 2020 (n = 18 068) | Difference, % (95% CI) | 2019 (n = 6 127 513) | 2020 (n = 5 970 239) | Difference, % (95% CI) | |

| OUD medication fills | 10 542 (65.37) | 12 284 (67.99) | –2.62 (–3.62 to –1.62) | 9661 (0.16) | 7431 (0.12) | 0.03 (0.03-0.04) |

| OUD-related visits | 4387 (27.20) | 4851 (26.85) | 0.35 (–0.59 to 1.30) | 8318 (0.14) | 7593 (0.13) | 0.01 (0.004-0.01) |

| Urine OUD toxicology tests | 2227 (13.81) | 1908 (10.56) | 3.25 (2.55 to 3.94) | 7056 (0.12) | 5025 (0.08) | 0.03 (0.03-0.04) |

Abbreviation: OUD, opioid use disorder.

This study uses 2019 and 2020 claims data from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse. The panels include individuals who were continuously enrolled in medical, behavioral health, and pharmacy benefits for January through May of the year in question. Recent OUD medication treatment is defined as at least 1 OUD medication fill in January or February of a given year. For both 2019 and 2020, the observation period included 13 weeks beginning on March 1.

Among individuals not receiving medication in January/February (n = 6 127 513 in 2019; n = 5 970 239 in 2020), the percentage receiving at least 1 fill in March through May 2020 was lower than 2019 (0.12% vs 0.16%; difference, 0.03% [95% CI, 0.03%-0.04%]). The percentage receiving at least 1 OUD visit in March through May (0.13% vs 0.14%; difference, 0.01% [95% CI, 0.004%-0.01%]) and the percentage receiving at least 1 urine test (0.08% vs 0.12%; difference, 0.03% [95% CI, 0.03%-0.04%]) were lower in 2020 than 2019. OUD visits delivered via telemedicine increased from 0.60% in week 1 of 2020 to 31.82% in week 13.

Discussion

During the first 3 months of the pandemic, among patients already receiving OUD medication, there was no decrease in medication fills or clinician visits. However, fewer individuals initiated OUD medications, and there was less urine testing across all patients. In recent research, OUD clinicians described that they could maintain care with existing patients via telemedicine during the pandemic but were uncomfortable initiating new patients with medication; they also reduced urine testing to protect patients from COVID-19 exposure.5 Also, fewer patients may be seeking care. Limitations include that the study population was 18 to 64 years old with private insurance or Medicare Advantage and the study period only extended through May 2020. Although individuals may have lost jobs and health insurance in 2020, the similar percentages continuing enrollment through May in 2019 and 2020 suggest no differential plan disenrollment.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

eTable. Regional Representation for Commercial and Medicare Advantage Enrollees in the Current Study Sample Relative to the US Population

eAppendix. Outcomes From Claims Data

References

- 1.Ochalek TA, Cumpston KL, Wills BK, Gal TS, Moeller FG. Nonfatal opioid overdoses at an urban emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. Published online September 18, 2020.doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehrotra A, Chernew M, Linetsky D, Hatch H, Cutler D, Schneider EC The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on outpatient visits: changing patterns of care in the newest COVID-19 hot spots. The Commonwealth Fund. Published online August 13, 2020. Accessed September 25, 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/aug/impact-covid-19-pandemic-outpatient-visits-changing-patterns-care-newest

- 3.Lin LA, Fernandez AC, Bonar EE. Telehealth for substance-using populations in the age of coronavirus disease 2019: recommendations to enhance adoption. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online July 1, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.OptumLabs OptumLabs and OptumLabs Data Warehouse (OLDW) Descriptions and Citation. OptumLabs; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uscher-Pines L, Sousa J, Raja P, Mehrotra A, Barnett M, Huskamp HA. Treatment of opioid use disorder during COVID-19: Experiences of clinicians transitioning to telemedicine. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;118:108124. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Regional Representation for Commercial and Medicare Advantage Enrollees in the Current Study Sample Relative to the US Population

eAppendix. Outcomes From Claims Data