Key Points

Question

Among patients with vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy, what is the effect of initial treatment with intravitreous aflibercept vs vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation on vision?

Findings

In this randomized trial of 205 eyes among 205 participants, the mean visual acuity letter score over 24 weeks was 59.3 (Snellen equivalent, 20/63) for the aflibercept group vs 63.0 (Snellen equivalent, 20/63) for the vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation group, a difference that was not statistically significant.

Meaning

In participants with vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy, there was no statistically significant difference in visual acuity over 24 weeks following initial treatment with aflibercept vs vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation, but the study may have been underpowered to detect a clinically important benefit in favor of initial vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation.

Abstract

Importance

Vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy can cause loss of vision. The best management approach is unknown.

Objective

To compare initial treatment with intravitreous aflibercept vs vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation for vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized clinical trial at 39 DRCR Retina Network sites in the US and Canada including 205 adults with vison loss due to vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy who were enrolled from November 2016 to December 2017. The final follow-up visit was completed in January 2020.

Interventions

Random assignment of eyes (1 per participant) to aflibercept (100 participants) or vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation (105 participants). Participants whose eyes were assigned to aflibercept initially received 4 monthly injections. Both groups could receive aflibercept or vitrectomy during follow-up based on protocol criteria.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was mean visual acuity letter score (range, 0-100; higher scores indicate better vision) over 24 weeks (area under the curve); the study was powered to detect a difference of 8 letters. Secondary outcomes included mean visual acuity at 4 weeks and 2 years.

Results

Among 205 participants (205 eyes) who were randomized (mean [SD] age, 57 [11] years; 115 [56%] men; mean visual acuity letter score, 34.5 [Snellen equivalent, 20/200]), 95% (195 of 205) completed the 24-week visit and 90% (177 of 196, excluding 9 deaths) completed the 2-year visit. The mean visual acuity letter score over 24 weeks was 59.3 (Snellen equivalent, 20/63) (95% CI, 54.9 to 63.7) in the aflibercept group vs 63.0 (Snellen equivalent, 20/63) (95% CI, 58.6 to 67.3) in the vitrectomy group (adjusted difference, −5.0 [95% CI, −10.2 to 0.3], P = .06). Among 23 secondary outcomes, 15 showed no significant difference. The mean visual acuity letter score was 52.6 (Snellen equivalent, 20/100) in the aflibercept group vs 62.3 (Snellen equivalent, 20/63) in the vitrectomy group at 4 weeks (adjusted difference, −11.2 [95% CI, −18.5 to −3.9], P = .003) and 73.7 (Snellen equivalent, 20/40) vs 71.0 (Snellen equivalent, 20/40) at 2 years (adjusted difference, 2.7 [95% CI, −3.1 to 8.4], P = .36). Over 2 years, 33 eyes (33%) assigned to aflibercept received vitrectomy and 34 eyes (32%) assigned to vitrectomy received subsequent aflibercept.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among participants whose eyes had vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy, there was no statistically significant difference in the primary outcome of mean visual acuity letter score over 24 weeks following initial treatment with intravitreous aflibercept vs vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation. However, the study may have been underpowered, considering the range of the 95% CI, to detect a clinically important benefit in favor of initial vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02858076

This randomized trial compares the effects of initial treatment with intravitreous aflibercept vs vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation on visual acuity over 24 weeks among adults with vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Introduction

The global prevalence of proliferative diabetic retinopathy, the most advanced form of diabetic eye disease, is estimated to be approximately 1.4% among all individuals with diabetes.1 Vitreous hemorrhage from retinal neovascularization is a frequent occurrence of proliferative diabetic retinopathy and can cause acute, severe vision loss.2 Among eyes with previously untreated proliferative diabetic retinopathy in the DRCR Retina Network Protocol S, vitreous hemorrhage developed in 46% and 48% of eyes over 5 years despite treatment with panretinal photocoagulation and ranibizumab, respectively.3,4

Vitrectomy has been the standard treatment for nonclearing vitreous hemorrhage since the 1970s.5 Removal of the vitreous gel during surgery provides rapid clearance of hemorrhage, elimination of traction on neovascular vessels that contribute to recurrent vitreous hemorrhage, and intraoperative delivery of photocoagulation to treat neovascularization. Although surgical techniques have improved over the last 5 decades,6,7 the risk of complications remains.8,9 Thus, clinicians are highly interested in developing nonsurgical approaches.

A more recent method for managing vitreous hemorrhage is in-office intravitreous injection of an antivascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agent that stimulates regression of neovascularization.10 The goal of anti-VEGF treatment for vitreous hemorrhage is not to directly remove the hemorrhage, but to regress neovascularization to prevent rebleeding while the hemorrhage is absorbed.11,12

Despite the frequency of this common condition and 2 available treatment approaches, there are not well-established guidelines regarding how to treat vitreous hemorrhage to optimize visual outcomes. The hypothesis of the study was that visual acuity recovery would be faster with vitrectomy because the blood is mechanically cleared during surgery. The objective of this study was to determine the efficacy of initial treatment with aflibercept vs vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation for vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Methods

This DRCR Retina Network study (Protocol AB) adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.13 The ethics board associated with each site provided approval. Study participants provided written informed consent. An independent data and safety monitoring committee provided oversight. The study protocol appears in Supplement 1 and the statistical analysis plan appears in Supplement 2.

Study Population

We recruited adults with type 1 or 2 diabetes at 39 sites in the US and Canada. We collected participant-reported race/ethnicity based on fixed categories per the National Institutes of Health policy and consistent with the US Food and Drug Administration guidelines.14,15 We enrolled 1 eye per participant; eyes had vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy causing vision impairment (best-corrected visual acuity letter score ≤78 [Snellen equivalent, 20/32 or worse] with at least light perception) for which the investigator deemed an intervention was indicated. Patients were excluded if their eyes had known center-involved diabetic macular edema, retinal detachments from fibrosis or scar tissue pulling on the retina (ie, traction) that were involving or threatening the macula, rhegmatogenous retinal detachments, neovascular glaucoma, or prior vitrectomy. We permitted patients who had prior panretinal photocoagulation and intravitreous anti-VEGF injection if the injections were administered more than 2 months before hemorrhage onset.

Study Design

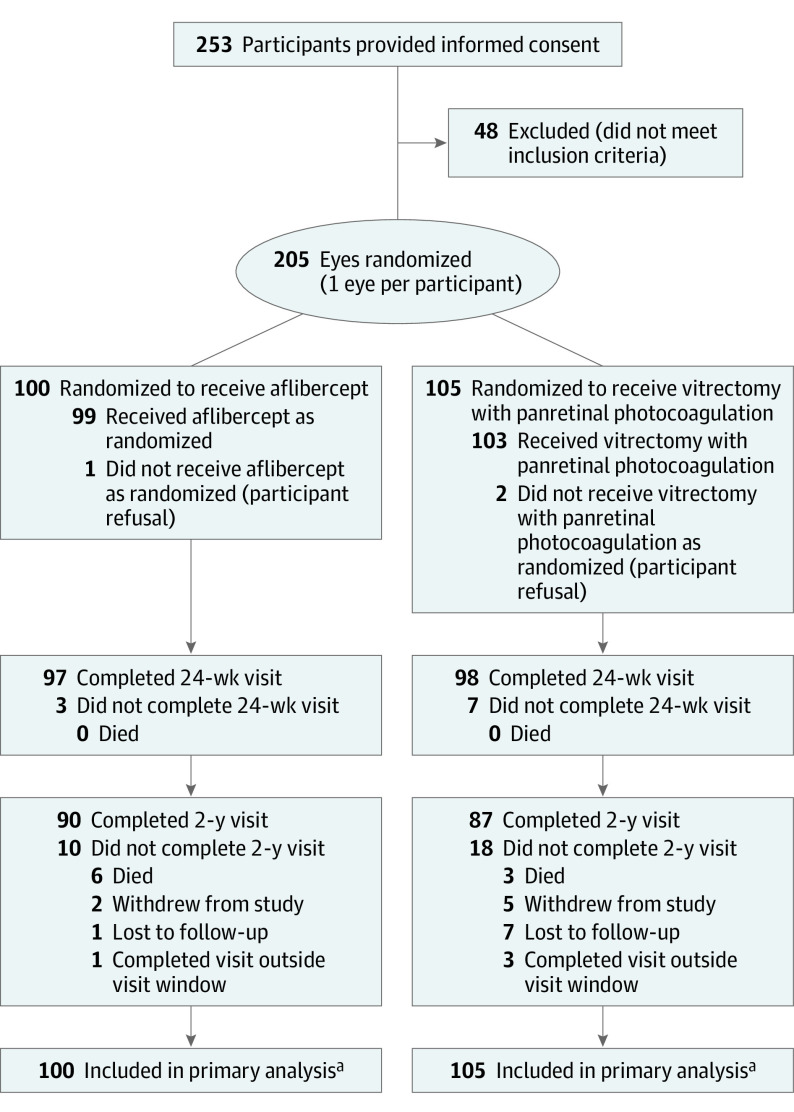

Randomization schedules were stratified by site with a 1:1 assignment ratio for initial treatment with intravitreous injections containing 2 mg of aflibercept (Eylea, Regeneron) or vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation (Figure 1). A statistician used computer-generated random numbers to create permuted block design randomization schedules (block sizes of 2 and 4). Treatment assignments were obtained by the study coordinator from the study website.

Figure 1. Randomization and Participant Flow in the Trial.

aMissing data were imputed via multiple imputation for the primary analysis of visual acuity over 24 weeks.

Participants were not formally screened before obtaining informed consent. The reasons for participant ineligibility were not systematically collected. Visit completion at 2 years was prespecified as completion of any study visit from 92 to 116 weeks.

Certified technicians obtained best-corrected visual acuity following protocol-defined refraction using electronic Early Treatment for Diabetic Retinopathy Study visual acuity testing16 at each visit and optical coherence tomography scans (if not precluded by media opacity from vitreous hemorrhage) at baseline and at weeks 24, 52, and 104. Retinal detachments were clinically assessed at each visit and during vitrectomy and, if needed, B-scan ultrasonography was performed. Visual acuity technicians were masked to treatment allocation; however, the investigators and participants were not.

Treatment Protocol

Eyes assigned to vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation underwent surgery within 2 weeks of randomization. Vitrectomy was performed according to the investigator’s usual routine using 23-gauge or smaller instruments with complete panretinal photocoagulation performed intraoperatively. Aflibercept could be given preoperatively but not intraoperatively or within 4 weeks after surgery. Four weeks after the vitrectomy, recurrent vitreous hemorrhage was treated with 2 monthly aflibercept injections and additional injections every 4 weeks at the discretion of the investigators. Repeat vitrectomy could be performed if the vitreous hemorrhage failed to clear after 2 aflibercept injections.

Eyes assigned to aflibercept received injections at baseline and at weeks 4, 8, and 12. At 16 weeks, injections were deferred if the complete fundus could be viewed and neovascularization was absent. At 24 weeks, injections were given unless the eye stabilized (2 consecutive visits with the size and density of the hemorrhage and neovascularization clinically unchanged since the last visit). Starting at 16 weeks, vitrectomy could be performed if there was persistent vitreous hemorrhage causing vision impairment following 2 monthly injections. Care during and following vitrectomy was the same as in the vitrectomy group.

All participants received aflibercept if the eye included in the study developed center-involved diabetic macular edema and visual acuity was 20/32 or worse and central subfield thickness met prespecified thresholds.17 Once initiated, treatment for macular edema followed the DRCR Retina Network anti-VEGF retreatment protocol.18 Participants whose contralateral eye, which was not included in the study, required anti-VEGF were treated with study-provided aflibercept.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was mean visual acuity letter score over 24 weeks calculated using area under the curve.19 Visual acuity is measured on a scale from 100 letters (Snellen equivalent, 20/10) to 0 letters (Snellen equivalent, <20/800); higher scores indicate better vision.

The prespecified secondary outcomes included mean visual acuity letter score, percentage of eyes 20/32 or better, and percentage of eyes 20/200 or worse at weeks 4, 12, 24, 52, and 104; mean visual acuity letter score over 104 weeks; and recurrent vitreous hemorrhage, retinal neovascularization, and central subfield thickness at weeks 24, 52, and 104. The percentage of eyes 20/20 or better, 20/40 or better, 20/800 or worse, and gain or loss of at least 30 letters were reported as tabulations without statistical comparison per the statistical analysis plan (Supplement 2). A prespecified secondary analysis of work productivity and activity impairment and an economic analysis are not reported.

The prespecified exploratory outcomes included an increase or decrease of at least 15 visual acuity letters and treatment for center-involved diabetic macular edema. Within-group frequency of aflibercept injections, panretinal photocoagulation, and vitrectomy (including frequency, timing, indication, and surgical details) also are presented.

A medical monitor, who was masked to treatment allocation, coded all adverse events according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities. Prespecified ocular and systemic adverse events included endophthalmitis, retinal detachment, retinal tear, cataract extraction, visually significant cataract (based on investigator judgment without standardized grading), ocular inflammation, elevated intraocular pressure, neovascular glaucoma, iris neovascularization, vascular events defined by Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration criteria, death, hospitalization, and any serious systemic adverse event.

Statistical Methods

A sample size of 162 was calculated, assuming a difference of 8 letters in mean visual acuity over 24 weeks, a standard deviation of 18 letters, 80% power, and an overall 2-sided type I error rate of 0.049. A mean difference of 5 letters has been used as the noninferiority limit for retinal diseases and a greater difference is needed for eyes with worse visual acuity such as those with vitreous hemorrhage.4,20,21 The sample size was increased to 200 to account for uncertainty in these assumptions.

The prespecified primary analysis was a multiple linear regression model with mean visual acuity over 24 weeks as the dependent variable and baseline visual acuity and lens status as covariates. Missing primary outcome data and secondary visual acuity outcomes were imputed with Markov chain–Monte Carlo multiple imputation. Prespecified sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome included analyses without imputation for missing outcomes, predictive mean matching imputation, Van der Waerden score transformation, robust regression using M-estimation, adjustment for additional covariates, and tipping point analyses. An analysis controlling for site effects was conducted post hoc. The prespecified subgroups of primary interest included prior panretinal photocoagulation, lens status, and age. The prespecified exploratory subgroups included prior treatment for diabetic macular edema, hemoglobin A1C level, vitreous hemorrhage duration, participant sex, and race/ethnicity. Differences in treatment effect between subgroups were evaluated by including an interaction term in the regression model.

Summary statistics were calculated from observed data. Complete case analyses were used for non–visual acuity outcomes. The regression models for the visual acuity outcomes included baseline visual acuity and lens status as covariates. The models for the other outcomes included baseline lens status as a covariate. Continuous outcomes were analyzed with multiple linear regression. Dichotomous outcomes were analyzed via logistic regression, risk differences were estimated by conditional standardization, and 95% CIs were estimated using the delta method.22 Kaplan-Meier estimates were plotted for time to event outcomes.23 Cox proportional hazards regression24 with lens status as a covariate was used for the development of center-involved diabetic macular edema. The proportional hazards assumption was verified using cumulative sums of Martingale residuals.25

The P values and 95% CIs were 2-sided. In the primary analysis, P < .049 was considered statistically significant. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, the findings for the analyses of the secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory. The analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Study Participants

From November 2016 to December 2017, 205 participants were randomly assigned to treatment with aflibercept (n = 100) or vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation (n = 105) (Figure 1). The final 2-year visit was completed in January 2020. Key baseline demographic and clinical factors were similar between groups (Table 1). Overall, the mean (SD) age was 57 (11) years, 115 (56%) were male, the mean hemoglobin A1c level was 8.5%, and the mean visual acuity letter score was 34.5 (Snellen equivalent, 20/200). At 24 weeks, 195 of 205 participants (95%) completed the visit; 177 of 196 participants (90% excluding 9 deaths) completed the 2-year visit.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics.

| Aflibercept (n = 100) |

Vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation (n = 105) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Participant characteristics, No. (%)a | ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 53 (53) | 62 (59) |

| Female | 47 (47) | 43 (41) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 56 (12) | 57 (11) |

| Self-reported race/ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 43 (43) | 41 (39) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 36 (36) | 47 (45) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 16 (16) | 11 (10) |

| Asian | 2 (2) | 5 (5) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (1) | 0 |

| >1 race | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Unknown or not reported | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Type of diabetesb | ||

| 1 | 17 (17) | 19 (18) |

| 2 | 83 (83) | 86 (82) |

| Duration of diabetes, mean (SD), yb | 19 (10) | 21 (11) |

| Insulin used | 78 (78) | 78 (74) |

| Hemoglobin A1c level, mean (SD), % | (n = 96) 8.7 (2.2) |

(n = 104) 8.3 (1.9) |

| Mean arterial pressure, mean (SD), mm Hgc | 102 (12) | 102 (12) |

| Disease or eventb | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 7 (7) | 15 (14) |

| Stroke | 5 (5) | 8 (8) |

| Kidney disease | 20 (20) | 18 (17) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD)d | (n = 85) 31 (7) |

(n = 93) 32 (7) |

| Daily cigarette smoking | ||

| Never | 60 (60) | 72 (69) |

| Prior | 27 (27) | 25 (24) |

| Current | 13 (13) | 8 (8) |

| Study eye characteristics, No. (%)a | ||

| Diabetic macular edema | ||

| Prior treatment | 29 (29) | 37 (35) |

| Prior treatment with anti-VEGF injection | 23 (23) | 28 (27) |

| Prior focal or grid laser photocoagulation | 15 (15) | 16 (15) |

| Diabetic retinopathy | ||

| Prior anti-VEGF injection | 23 (23) | 22 (21) |

| Prior panretinal photocoagulation | 42 (42) | 58 (55) |

| Approximate duration of vitreous hemorrhage, mo | ||

| <1 | 60 (60) | 57 (54) |

| 1-3 | 27 (27) | 27 (26) |

| 4-6 | 8 (8) | 6 (6) |

| 7-12 | 1 (1) | 6 (6) |

| >12 | 4 (4) | 9 (9) |

| Lens status at clinical examination | ||

| Phakic (natural lens) | 75 (75) | 81 (77) |

| Prosthetic intraocular lens | 25 (25) | 24 (23) |

| Visual acuitye | ||

| Letter score, mean (SD) | 35.6 (28.1) | 33.5 (28.8) |

| Snellen equivalent, mean | 20/200 | 20/250 |

| Letter score, median (IQR) | 37.0 (63.0-2.0) | 37.0 (62.0-0) |

| Snellen equivalent, median | 20/200 | 20/200 |

| Snellen equivalent range (letter score range) | ||

| 20/32-20/40 (78-69) | 17 (17) | 15 (14) |

| 20/50-20/80 (68-54) | 18 (18) | 24 (23) |

| 20/100-20/160 (53-39) | 13 (13) | 9 (9) |

| 20/200-20/800 (38-4) | 26 (26) | 24 (23) |

| Worse than 20/800 (≤3) | 26 (26) | 33 (31) |

| Traction retinal detachmentf | ||

| Yes (macula not threatened) | 5 (5) | 3 (3) |

| No | 95 (95) | 102 (97) |

| Intraocular pressure, mean (SD), mm Hgg | 16 (4) | 15 (3) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Some of the data are expressed as mean (SD) or median (IQR) as indicated.

Collected by chart review when possible or was self-reported.

Calculated as (⅔ × diastolic blood pressure) + (⅓ × systolic blood pressure) at enrollment.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Measured using electronic Early Treatment for Diabetic Retinopathy Study visual acuity testing on a scale from 100 letters (Snellen equivalent, 20/10) to 0 letters (Snellen equivalent, <20/800); higher scores indicate better vision. The data presented are the best-corrected visual acuity scores in the study eye following protocol-defined refraction.

Caused by the presence of retinal fibrosis or scarring that pulls on the retina.

Measured using a Goldmann Applanation tonometer (when available) or a Tono-Pen tonometer.

Study Treatments

Among participants in the aflibercept group, the mean number of aflibercept injections was 4.6 over 24 weeks and 8.9 over 2 years; 893 of 914 (98%) protocol-required injections were performed at completed visits (Table 2). The cumulative probability of vitrectomy over 2 years was 34% (95% CI, 26% to 45%) (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). During the first 16 weeks, 6 eyes underwent 7 vitrectomies (6 for retinal detachment and 1 for endophthalmitis) (eTable 1 in Supplement 3). Over 2 years, 33 eyes (33%) assigned to aflibercept received vitrectomy. Participants completed a median of 19 visits.

Table 2. Study Treatment During Follow-up.

| Aflibercept (n = 100) |

Vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation (n = 105) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Had ≥1 vitrectomy, No. (%)a | 33 (33) | 8 (8) |

| Timing of first vitrectomy, No. (%)a | ||

| Between 0 and <24 wk | 14 (14) | 5 (5) |

| Between 24 and <52 wk | 9 (9) | 3 (3) |

| Between 52 and 104 wk | 10 (10) | 0 |

| Panretinal photocoagulation, No. (%)a | ||

| During follow-up vitrectomy | 32 (32) | 4 (4) |

| Outside follow-up vitrectomy | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Had ≥1 intravitreous aflibercept injection, No. (%)b | 99 (99)c | 34 (32)d |

| No. of intravitreous aflibercept injections, mean (SD), wkb | ||

| Between 0 and <24 wk | 4.6 (1.3) | 0.3 (0.8) |

| Between 0 and 104 wk | 8.9 (4.6) | 2.3 (4.3) |

| No. of intravitreous aflibercept injections through 104 wk, No. (%)b | ||

| 0 | 1 (1)c | 71 (68) |

| 1-4 | 12 (12) | 11 (10) |

| 5-8 | 39 (39) | 12 (11) |

| 9-12 | 28 (28) | 6 (6) |

| ≥13 | 20 (20) | 5 (5) |

Excludes the initial vitrectomy and any procedures performed before or during the initial vitrectomy.

Includes the initial injection of aflibercept.

One participant refused treatment.

Twenty-one eyes (20%) received at least 1 aflibercept injection for center-involved diabetic macular edema; 20 eyes (19%) received at least 1 aflibercept injection for complications of proliferative diabetic retinopathy, which included vitreous hemorrhage.

Among participants in the vitrectomy group, 103 eyes (98%) underwent vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation (eTable 2 in Supplement 3) and 44 of 103 eyes (43%) received preoperative aflibercept. Repeat vitrectomy was performed in 8 eyes (8%) (Table 2 and eTable 2 in Supplement 3). Over 2 years, 34 eyes (32%) assigned to vitrectomy received subsequent aflibercept (mean, 2.3 injections over 2 years). There were 21 participants (20%) who received injections for diabetic macular edema and 20 participants (19%) who received injections for complications of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Participants completed a median of 12 visits.

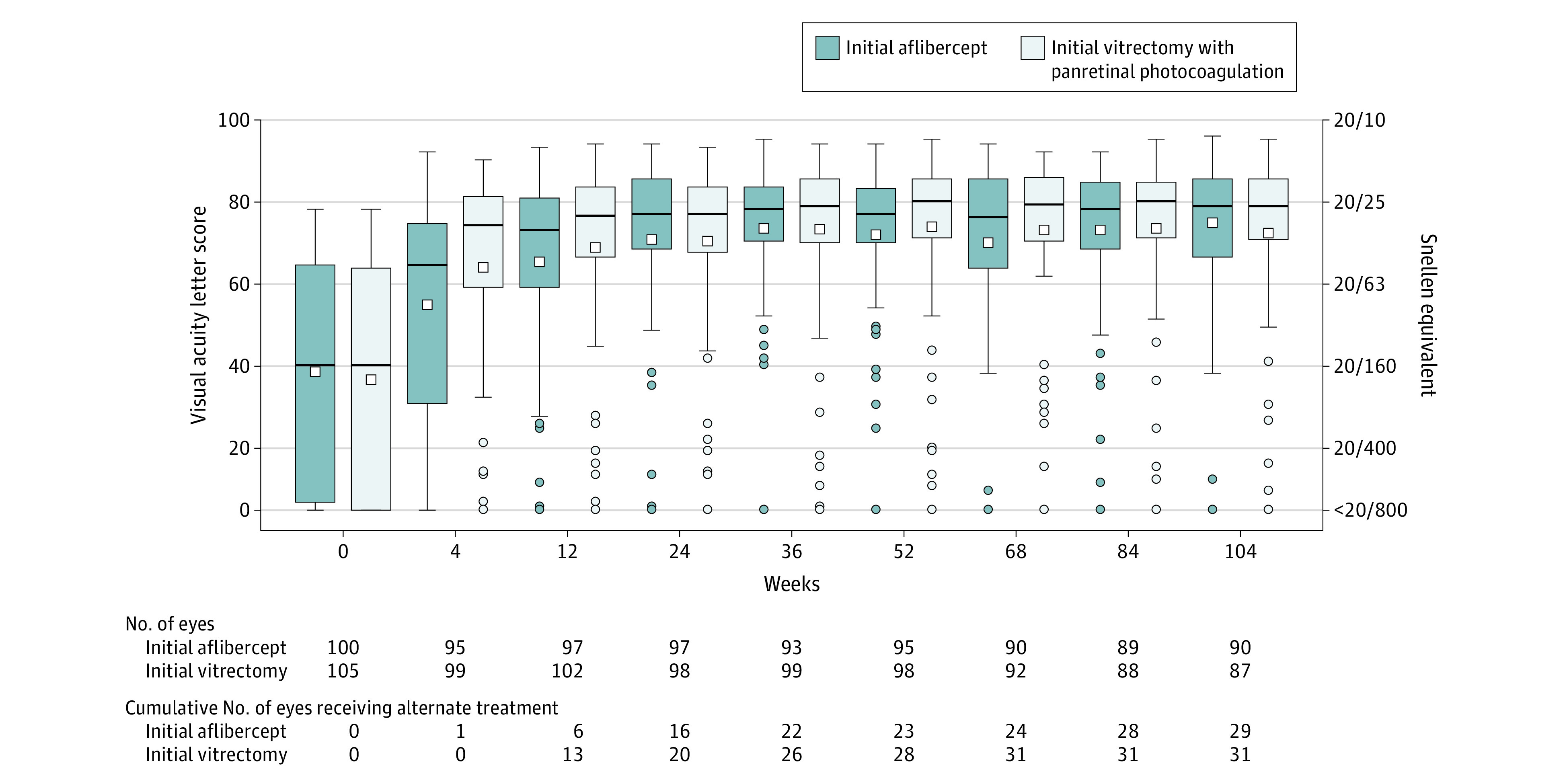

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome of mean visual acuity letter score over 24 weeks was 59.3 (Snellen equivalent, 20/63) (95% CI, 54.9 to 63.7) in the aflibercept group vs 63.0 (Snellen equivalent, 20/63) (95% CI, 58.6 to 67.3) in the vitrectomy group (adjusted difference, −5.0 [95% CI,−10.2 to 0.3], P = .06) (Table 3). Visual acuity improved faster with vitrectomy, but there was no difference at 24 weeks (Figure 2 and eFigure 2 in Supplement 3). The prespecified and post hoc sensitivity analyses provided estimated treatment effects of 3.9 to 6.3 letters better with vitrectomy and corresponding P values of .14 to .007 (eTable 3 in Supplement 3). There were no significant (P < .05) interaction effects to indicate that the difference between treatment groups varied in the primary preplanned subgroup analyses (lens status, prior panretinal photocoagulation, age; eTable 4 in Supplement 3).

Table 3. Primary and Secondary Visual Acuity Outcomes.

| Aflibercept | Vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation | Difference (95% CI)a,b | P valuea,c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjustedc | ||||

| Primary outcomed | |||||

| No. of participants over 24 wk | 97 | 98 | |||

| Visual acuity letter score (area under the curve), mean (SD) | 59.3 (21.9) | 63.0 (21.7) | −4.3 (−10.0 to 1.4) | −5.0 (−10.2 to 0.3) | .06 |

| Snellen equivalent, mean | 20/63 | 20/63 | |||

| Visual acuity letter score (area under the curve), median (IQR) | 65.0 (75.5 to 49.5) | 71.3 (77.5 to 57.4) | |||

| Snellen equivalent, median | 20/50 | 20/40 | |||

| Secondary outcomesd | |||||

| No. of participants at 4 wk | 95 | 99 | |||

| Visual acuity letter score, mean (SD) | 52.6 (29.4) | 62.3 (26.8) | −10.3 (−18.2 to −2.4) | −11.2 (−18.5 to −3.9) | .003 |

| Snellen equivalent, mean | 20/100 | 20/63 | |||

| Visual acuity letter score, median (IQR) | 63.0 (74.0 to 23.0) | 73.0 (81.0 to 56.0) | |||

| Snellen equivalent, median | 20/63 | 20/40 | |||

| Snellen equivalent range (visual acuity score), No. (%) | |||||

| 20/32 or better (≥74) | 24 (25) | 49 (49) | −24 (−37 to −11) | −28 (−42 to −14) | <.001 |

| 20/200 or worse (≤38) | 26 (27) | 18 (18) | 10 (−2 to 22) | 11 (−0 to 23) | .05 |

| No. of participants at 24 wk | 97 | 98 | |||

| Visual acuity letter score, mean (SD) | 69.4 (23.8) | 69.0 (23.1) | 0.1 (−6.3 to 6.6) | −0.5 (−6.7 to 5.7) | .88 |

| Snellen equivalent, mean | 20/40 | 20/40 | |||

| Visual acuity letter score, median (IQR) | 76.0 (85.0 to 67.0) | 76.0 (83.0 to 66.0) | |||

| Snellen equivalent, median | 20/32 | 20/32 | |||

| Snellen equivalent range (visual acuity score), No. (%) | |||||

| 20/32 or better (≥74) | 61 (63) | 59 (60) | 3 (−11 to 17) | 2 (−12 to 16) | .75 |

| 20/200 or worse (≤38) | 10 (10) | 10 (10) | 0 (−8 to 9) | 1 (−7 to 8) | .85 |

| No. of participants over 2 y | 90 | 87 | |||

| Visual acuity letter score (area under the curve), mean (SD) | 68.7 (15.0) | 70.0 (18.8) | −1.8 (−6.5 to 3.0) | −2.2 (−6.7 to 2.3) | .34 |

| Snellen equivalent, mean | 20/50 | 20/40 | |||

| Visual acuity letter score (area under the curve), median (IQR) | 70.5 (79.4 to 64.2) | 75.4 (82.1 to 65.8) | |||

| Snellen equivalent, median | 20/40 | 20/32 | |||

| No. of participants at 2 y | 90 | 87 | |||

| Visual acuity letter score, mean (SD) | 73.7 (16.4) | 71.0 (24.0) | 2.9 (−2.9 to 8.7) | 2.7 (−3.1 to 8.4) | .36 |

| Snellen equivalent, mean | 20/40 | 20/40 | |||

| Visual acuity letter score, median (IQR) | 78.0 (85.0 to 65.0) | 78.0 (85.0 to 69.0) | |||

| Snellen equivalent, median | 20/32 | 20/32 | |||

| Snellen equivalent range (visual acuity score), No. (%) | |||||

| 20/32 or better (≥74) | 56 (62) | 59 (68) | −2 (−17 to 12) | −3 (−17 to 11) | .68 |

| 20/200 or worse (≤38) | 3 (3) | 10 (11) | −7 (−14 to 0) | −6 (−13 to 1) | .08 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Missing data were imputed with Markov chain–Monte Carlo multiple imputation. The imputation model included treatment group, lens status, baseline visual acuity score, and visual acuity score at common follow-up visits.

The mean differences were estimated via multiple linear regression for continuous outcomes (positive values indicate better visual acuity scores with aflibercept; ie, aflibercept minus vitrectomy) and the risk differences were estimated via logistic regression and the delta method for binary outcomes (positive values indicate greater risk with aflibercept; ie, aflibercept minus vitrectomy).

Adjusted for baseline visual acuity and lens status.

Scores indicate best-corrected visual acuity in the study eye following protocol-defined refraction. Visual acuity was measured using electronic Early Treatment for Diabetic Retinopathy Study visual acuity testing on a scale from 100 letters (Snellen equivalent, 20/10) to 0 letters (Snellen equivalent, <20/800); higher scores indicate better vision.

Figure 2. Visual Acuity Letter Score Through 2 Years.

Within each box and whisker plot, the horizontal bar represents the median and the white square represents the mean. The top of the box is the third quartile (75th percentile) and the bottom of the box is the first quartile (25th percentile). Whiskers extend from the nearest quartile to the most extreme data point within 1.5 times the interquartile range; values beyond these limits are plotted as circles. The number of eyes completing each visit and the cumulative number of eyes that received alternative treatment through the visit (eg, aflibercept in the vitrectomy group or vitrectomy in the aflibercept group) appear below the plot. The best-corrected visual acuity was collected after protocol-defined refraction. Visual acuity was measured using electronic Early Treatment for Diabetic Retinopathy Study visual acuity testing on a scale from 100 letters (Snellen equivalent, 20/10) to 0 letters (Snellen equivalent, <20/800); higher scores indicate better vision.

Secondary Outcomes

The secondary outcome of mean visual acuity letter score at 4 weeks was 52.6 (Snellen equivalent, 20/100) (95% CI, 46.7 to 58.6) in the aflibercept group vs 62.3 (Snellen equivalent, 20/63) (95% CI, 57.0 to 67.7) in the vitrectomy group (adjusted difference, −11.2 [95% CI, −18.5 to −3.9], P = .003) (Table 3). At 24 weeks, the mean visual acuity letter score was 69.4 (Snellen equivalent, 20/40) (95% CI, 64.6 to 74.2) in the aflibercept group vs 69.0 (Snellen equivalent, 20/40) (95% CI, 64.4-73.6) in the vitrectomy group (adjusted difference, −0.5 [95% CI, −6.7 to 5.7], P = .88) (Table 3). A good visual acuity letter score of 74 letters or more (Snellen equivalent, 20/32 or better) occurred in 61 of 97 eyes (63%) in the aflibercept group vs 59 of 98 eyes (60%) in the vitrectomy group (adjusted difference, 2% [95% CI, −12% to 16%], P = .75). A poor visual acuity letter score of 38 letters or fewer (Snellen equivalent, 20/200 or worse) occurred in 10 eyes (10%) in each group (adjusted difference, 1% [95% CI, −8% to 7%], P = .85). Additional secondary and exploratory outcomes appear in eTable 5 and eTable 6 in Supplement 3.

The mean visual acuity letter score over 2 years was 68.7 (Snellen equivalent, 20/50) (95% CI, 65.6 to 71.9) in the aflibercept group vs 70.0 (Snellen equivalent, 20/40) (95% CI, 66.0 to 74.0) in the vitrectomy group (adjusted difference, −2.2 [95% CI, −6.7 to 2.3], P = .34) (Table 3). At 2 years, the mean visual acuity letter score was 73.7 (Snellen equivalent, 20/40) (95% CI, 70.2 to 77.1) in the aflibercept group vs 71.0 (Snellen equivalent, 20/40) (95% CI, 65.9 to 76.1) in the vitrectomy group (adjusted difference, 2.7 [95% CI, −3.1 to 8.4], P = .36). A good visual acuity letter score of 74 or more (Snellen equivalent, 20/32 or better) occurred in 56 of 90 eyes (62%) in the aflibercept group vs 59 of 87 eyes (68%) in the vitrectomy group (adjusted difference, −3% [95% CI, −17 to 11%], P = .68). A poor visual acuity letter score of 38 letters or fewer (Snellen equivalent, 20/200 or worse) occurred in 3 eyes (3%) in the aflibercept group vs 10 eyes (11%) in the vitrectomy group (adjusted difference, −6% [95% CI, −13% to 1%], P = .08).

Recurrent vitreous hemorrhage occurred at least once in 48 of 97 participants (49%) in the aflibercept group and 16 of 104 participants (15%) in the vitrectomy group (adjusted difference, 34% [95% CI, 22% to 46%], P < .001; eTable 7 in Supplement 3). The proportion of eyes with retinal neovascularization on clinical examination was significantly greater among participants in the aflibercept group vs participants in the vitrectomy group at 24 weeks (25 of 85 [29%] vs 3 of 92 [3%], respectively; adjusted difference, 25% [95% CI, 15% to 36%], P < .001) and at 2 years (20 of 88 [23%] vs 2 of 83 [2%]; adjusted difference, 20% [95% CI, 11% to 30%], P < .001).

Exploratory Outcomes

The proportion with center-involved diabetic macular edema at 24 weeks was 8% (7 of 87) in the aflibercept group vs 31% (28 of 90) in the vitrectomy group (difference, −23% [95% CI, −34% to −12%], P < .001) and was 17% (15 of 88) vs 21% (17 of 80), respectively, at 2 years (difference, −4% [95% CI, −16% to 8%], P = .48; eTable 8 in Supplement 3). The cumulative probability of receiving anti-VEGF injections for center-involved diabetic macular edema through 2 years was 18% in the aflibercept group vs 22% in the vitrectomy group (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.41 to 1.46], P = .42; eFigure 3 in Supplement 3).

Adverse Events

Endophthalmitis occurred in 1 eye (1%) in the aflibercept group (related to aflibercept injection) and in 2 eyes (2%) in the vitrectomy group (related to vitrectomy) (Table 4). In the aflibercept group, traction retinal detachment was identified at or before the first visit when vitreous hemorrhage subsided sufficiently to allow the investigator a clear view of the retina or the first vitrectomy (whichever occurred first) in 13 eyes (13%) and after that time in 9 eyes (9%). In the vitrectomy group, traction retinal detachment was first identified during the initial vitrectomy in 13 eyes (12%) and after the initial vitrectomy in 1 eye (<1%) (additional details appear in eTable 9 in Supplement 3). New or worsened rhegmatogenous retinal detachment was identified in 4 eyes (4%) assigned to aflibercept and in 5 eyes (5%) assigned to vitrectomy. Among phakic eyes, cataract extraction or visually significant cataract (per the investigator) occurred in 37 of 75 eyes (49%) in the aflibercept group and in 36 of 81 eyes (44%) in the vitrectomy group; cataract extraction was performed in 23 eyes (31%) and 22 eyes (27%), respectively.

Table 4. Adverse Events Through 2 Years.

| No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Aflibercept (n = 100) |

Vitrectomy and panretinal photocoagulation (n = 105) |

|

| Ocular adverse events occurring in study eyes: participants with ≥1 event | ||

| Cataract extraction or visually significant cataract on clinical examination (eyes with natural lens only) | (n = 75) 37 (49) |

(n = 81) 36 (44) |

| Visually significant cataract | (n = 75) 34 (45) |

(n = 81) 35 (43) |

| Cataract extraction | (n = 75)a 23 (31) |

(n = 81) 22 (27) |

| Adverse intraocular pressure event | 23 (23) | 25 (24) |

| Increase in intraocular pressure ≥10 mm Hg from baseline | 16 (16) | 17 (16) |

| Intraocular pressure ≥30 mm Hg at any visit | 8 (8) | 10 (10) |

| Initiation of medication not in use at baseline to lower intraocular pressure | 14 (14) | 16 (15) |

| Glaucoma procedure | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Retinal detachment | 23 (23) | 15 (14) |

| Traction retinal detachment | 22 (22) | 14 (13) |

| Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment | 4 (4) | 5 (5) |

| Ocular inflammation | 6 (6) | 4 (4) |

| Neovascularization of the iris | 2 (2) | 5 (5) |

| Retinal tear (without detachment) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) |

| Endophthalmitis | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Neovascular glaucoma | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Systemic adverse events: participants with ≥1 event | ||

| Serious adverse event | 42 (42) | 43 (41) |

| Hospitalization | 39 (39) | 41 (39) |

| Death | 6 (6) | 3 (3) |

| Vascular events defined by Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration criteria | ||

| Any event | 8 (8) | 7 (7) |

| Death due to vascular or unknown cause | 5 (5) | 3 (3) |

| Nonfatal stroke | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Nonfatal myocardial infarction | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

Among the 75 eyes with natural lens (ie, phakic eyes) in the initial aflibercept group at baseline, 27 underwent vitrectomy during follow-up. Of the 23 eyes that underwent cataract extraction, 9 had cataract extraction and no vitrectomy during follow-up, 3 had cataract extraction before undergoing vitrectomy (ie, these eyes were phakic at baseline but pseudophakic at time of first vitrectomy), and 11 had cataract extraction after their first vitrectomy.

At least 1 serious systemic adverse event occurred in 42 participants (42%) in the aflibercept group and in 43 participants (41%) in the vitrectomy group. Myocardial infarction, stroke, and death of vascular or unknown cause occurred in 8 participants (8%) in the aflibercept group and in 7 participants (7%) in the vitrectomy group. All adverse events appear in eTables 10 through 12 in Supplement 3.

Discussion

In this multicenter randomized clinical trial among participants whose eyes had vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy, there was no statistically significant difference in the primary outcome of mean visual acuity letter score over 24 weeks between eyes initially treated with intravitreous aflibercept injections vs those treated with vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation, but the 95% CI was wide, and the study may have been underpowered to detect a clinically important benefit in favor of initial vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation. Nonetheless, mean visual acuity was not significantly different between the groups at 12 weeks or at any visit thereafter through 2 years.

Most previous studies of vitrectomy for vitreous hemorrhage have been retrospective and involved a limited number of sites and surgeons.26,27,28 This study, however, was a multicenter randomized trial involving 87 investigators across 39 clinical sites. Surgeons could use their routine technique with prior specifications regarding only instrumentation gauge, panretinal photocoagulation, and perioperative anti-VEGF injection, which enabled collection of surgical data across a diversity of practices and enhanced the generalizability of these results. Importantly, because the protocol (Supplement 1) allowed crossover treatment for prespecified criteria, 1 in 3 eyes from each group received the alternate treatment (aflibercept or vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation) over 2 years. Thus, when following treatment approaches developed by the DRCR Retina Network investigators, many participants receive both therapies.

During vitrectomy, visible vitreoretinal traction is generally removed along with vitreous scaffolding. Therefore, most surgeries relieve retinal detachments with macular-threatening traction and help prevent subsequent traction retinal detachments. Only 1 eye developed traction retinal detachment after initial surgery in the vitrectomy group. Eyes starting treatment with aflibercept remained at risk for persistence, progression, or development of a traction retinal detachment. Some of the 22 traction retinal detachments noted after baseline were likely present at baseline but not visible because the vitreous hemorrhage precluded complete retinal viewing. Regardless of when the traction retinal detachments developed, 12 eyes (12%) in the aflibercept group underwent vitrectomy for traction retinal detachment, and the final visual acuity scores for eyes in the aflibercept group with traction retinal detachment were similar to eyes without traction retinal detachment (median, 20/32 for both).

Although visual outcomes were not significantly different between treatment groups from 12 weeks through 2 years, additional findings from this study may help clinicians guide therapeutic decisions for individuals with vitreous hemorrhage. The benefits of vitrectomy in this study included faster restoration of vision, reduced likelihood of recurrent vitreous hemorrhage, and greater resolution of neovascularization. In contrast, the aflibercept group experienced less frequent center-involved diabetic macular edema and avoided vitrectomy in two-thirds of participants. Based on prior results, panretinal photocoagulation may result in more peripheral visual field deficits than anti-VEGF agents injected in the eyes of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy.3,29 The decision to initiate treatment using anti-VEGF injections vs vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation is influenced by many factors, including anticipated likelihood of patient adherence with follow-up visits, medical comorbidities, access to specialized treatments or medications, and the need or desire to hasten visual recovery, particularly for patients whose fellow eye also does not have good vision.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, even though retention through 24 weeks and 1 year was excellent in both groups (93%-97%), retention was lower in the vitrectomy group vs the aflibercept group at 2 years (85% vs 96%, respectively), which could bias comparisons of 2-year outcomes if loss to follow-up was related to treatment efficacy.

Second, neither the investigators nor the participants could be masked to treatment allocation owing to the nature of the treatments; however, visual acuity technicians were masked to treatment allocation, which limits bias in the primary analysis.

Third, aflibercept was the only anti-VEGF agent used in this study; therefore, it is unknown whether similar results would be obtained with an alternative such as bevacizumab or ranibizumab.

Fourth, although the long-term effects of treatments in the population with diabetes are important, this trial did not address visual outcomes or durability of neovascularization regression beyond 2 years.

Conclusions

Among participants whose eyes had vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy, there was no statistically significant difference in the primary outcome of mean visual acuity letter score over 24 weeks following initial treatment with intravitreous aflibercept vs vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation. However, the study may have been underpowered, considering the range of the 95% CI, to detect a clinically important benefit in favor of initial vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation.

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eFigure 1. Time to First Vitrectomy in the Initial Aflibercept Group: Secondary Outcome

eFigure 2. Mean Visual Acuity Letter Score Through 2 Years by Treatment Group

eFigure 3. Time to First Treatment for Center-Involved Diabetic Macular Edema by Treatment Group: Exploratory Outcome

eTable 1. Indications for Vitrectomy During Follow-up by Treatment Group

eTable 2. Initial Vitrectomy in the Initial Vitrectomy Group

eTable 3. Sensitivity Analyses of Average Visual Acuity Score Over 24 Weeks by Treatment Group, Adjusted for Baseline Visual Acuity and Lens Status

eTable 4. Subgroup Analyses of Average Visual Acuity Score Over 24 Weeks by Treatment Group, Adjusted for Baseline Visual Acuity and Lens Status

eTable 5. Exploratory Visual Acuity Outcomes by Treatment Group

eTable 6. Additional Secondary Visual Acuity Outcomes by Treatment Group

eTable 7. Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy Complications by Treatment Group, Adjusted for Baseline Lens Status: Secondary Outcomes

eTable 8. Retinal Thickening by Treatment Group, Adjusted for Baseline Lens Status: Secondary and Exploratory Outcomes

eTable 9. New and Worsening Retinal Detachments by Treatment Group

eTable 10. Systemic Adverse Events by Treatment Group Through 2 Years

eTable 11. Ocular Adverse Events Occurring in Study Eyes by Treatment Group Through 2 Years

eTable 12. Ocular Adverse Events Occurring in Non-Study Eyes After the First Non-Study Eye Aflibercept Injection by Treatment Group Through 2 Years

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Thomas RL, Halim S, Gurudas S, Sivaprasad S, Owens DR. IDF Diabetes Atlas: a review of studies utilising retinal photography on the global prevalence of diabetes related retinopathy between 2015 and 2018. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107840. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duh EJ, Sun JK, Stitt AW. Diabetic retinopathy: current understanding, mechanisms, and treatment strategies. JCI Insight. 2017;2(14):e93751. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.93751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gross JG, Glassman AR, Liu D, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Five-year outcomes of panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(10):1138-1148. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.3255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gross JG, Glassman AR, Jampol LM, et al. ; Writing Committee for the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(20):2137-2146. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Machemer R, Blankenship G. Vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy associated with vitreous hemorrhage. Ophthalmology. 1981;88(7):643-646. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(81)34972-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Misra A, Ho-Yen G, Burton RL. 23-Gauge sutureless vitrectomy and 20-gauge vitrectomy: a case series comparison. Eye (Lond). 2009;23(5):1187-1191. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Recchia FM, Scott IU, Brown GC, Brown MM, Ho AC, Ip MS. Small-gauge pars plana vitrectomy: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(9):1851-1857. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khuthaila MK, Hsu J, Chiang A, et al. . Postoperative vitreous hemorrhage after diabetic 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155(4):757-763, 763.e1-763.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castellarin A, Grigorian R, Bhagat N, Del Priore L, Zarbin MA. Vitrectomy with silicone oil infusion in severe diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87(3):318-321. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.3.318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avery RL, Pearlman J, Pieramici DJ, et al. . Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) in the treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(10):1695.e1-1695.e15, e1691-e1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Randomized clinical trial evaluating intravitreal ranibizumab or saline for vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(3):283-293. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhavsar AR, Torres K, Glassman AR, Jampol LM, Kinyoun JL; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Evaluation of results 1 year following short-term use of ranibizumab for vitreous hemorrhage due to proliferative diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(7):889-890. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institutes of Health NIH policy and guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research. Accessed April 11, 2019. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/women_min/guidelines.htm

- 15.US Food and Drug Administration Collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials. Accessed April 11, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM126396.pdf?source=govdelivery&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery

- 16.Beck RW, Moke PS, Turpin AH, et al. . A computerized method of visual acuity testing: adaptation of the early treatment of diabetic retinopathy study testing protocol. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135(2):194-205. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(02)01825-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chalam KV, Bressler SB, Edwards AR, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Retinal thickness in people with diabetes and minimal or no diabetic retinopathy: Heidelberg Spectralis optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(13):8154-8161. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(13):1193-1203. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker CW, Glassman AR, Beaulieu WT, et al. ; DRCR Retina Network . Effect of initial management with aflibercept vs laser photocoagulation vs observation on vision loss among patients with diabetic macular edema involving the center of the macula and good visual acuity: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(19):1880-1894. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck RW, Maguire MG, Bressler NM, Glassman AR, Lindblad AS, Ferris FL. Visual acuity as an outcome measure in clinical trials of retinal diseases. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(10):1804-1809. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.06.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin DF, Maguire MG, Ying GS, Grunwald JE, Fine SL, Jaffe GJ; CATT Research Group . Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(20):1897-1908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Localio AR, Margolis DJ, Berlin JA. Relative risks and confidence intervals were easily computed indirectly from multivariable logistic regression. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(9):874-882. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53(282):457-481. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J Royal Stat Soc Series B (Methodological). 1972;34(2):187-220. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1972.tb00899.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin DY, Wei LJ, Ying Z. Checking the Cox model with cumulative sums of Martingale-based residuals. Biometrika. 1993;80(3):557-572. doi: 10.1093/biomet/80.3.557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostri C, Lux A, Lund-Andersen H, la Cour M. Long-term results, prognostic factors and cataract surgery after diabetic vitrectomy: a 10-year follow-up study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92(6):571-576. doi: 10.1111/aos.12325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta B, Sivaprasad S, Wong R, et al. . Visual and anatomical outcomes following vitrectomy for complications of diabetic retinopathy: the DRIVE UK study. Eye (Lond). 2012;26(4):510-516. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta B, Wong R, Sivaprasad S, Williamson TH. Surgical and visual outcome following 20-gauge vitrectomy in proliferative diabetic retinopathy over a 10-year period, evidence for change in practice. Eye (Lond). 2012;26(4):576-582. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maguire MG, Liu D, Glassman AR, et al. ; DRCR Retina Network . Visual field changes over 5 years in patients treated with panretinal photocoagulation or ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138(3):285-293. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.5939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eFigure 1. Time to First Vitrectomy in the Initial Aflibercept Group: Secondary Outcome

eFigure 2. Mean Visual Acuity Letter Score Through 2 Years by Treatment Group

eFigure 3. Time to First Treatment for Center-Involved Diabetic Macular Edema by Treatment Group: Exploratory Outcome

eTable 1. Indications for Vitrectomy During Follow-up by Treatment Group

eTable 2. Initial Vitrectomy in the Initial Vitrectomy Group

eTable 3. Sensitivity Analyses of Average Visual Acuity Score Over 24 Weeks by Treatment Group, Adjusted for Baseline Visual Acuity and Lens Status

eTable 4. Subgroup Analyses of Average Visual Acuity Score Over 24 Weeks by Treatment Group, Adjusted for Baseline Visual Acuity and Lens Status

eTable 5. Exploratory Visual Acuity Outcomes by Treatment Group

eTable 6. Additional Secondary Visual Acuity Outcomes by Treatment Group

eTable 7. Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy Complications by Treatment Group, Adjusted for Baseline Lens Status: Secondary Outcomes

eTable 8. Retinal Thickening by Treatment Group, Adjusted for Baseline Lens Status: Secondary and Exploratory Outcomes

eTable 9. New and Worsening Retinal Detachments by Treatment Group

eTable 10. Systemic Adverse Events by Treatment Group Through 2 Years

eTable 11. Ocular Adverse Events Occurring in Study Eyes by Treatment Group Through 2 Years

eTable 12. Ocular Adverse Events Occurring in Non-Study Eyes After the First Non-Study Eye Aflibercept Injection by Treatment Group Through 2 Years

Data sharing statement