Abstract

Introduction:

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) pulse amplitude, which determines the induced electric field magnitude in the brain, is currently set at 800–900 milliamperes (mA) on modern ECT devices without any clinical or scientific rationale. The present study assessed differences in depression and cognitive outcomes for three different pulse amplitudes during an acute ECT series. We hypothesized that the lower amplitudes would maintain the antidepressant efficacy of the standard treatment and reduce the risk of neurocognitive impairment.

Methods:

This double-blind investigation randomized subjects to three treatment arms: 600, 700, and 800 mA (active comparator). Clinical, cognitive, and imaging assessments were conducted pre-, mid- and post-ECT. Subjects had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, age range between 50 and 80 years, and met clinical indication for ECT.

Results:

The 700 and 800 mA arms had improvement in depression outcomes relative to the 600 mA arm. The amplitude groups showed no differences in the primary cognitive outcome variable, the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R) retention raw score. However, secondary cognitive outcomes such as the Delis Kaplan Executive Function System (DKEFS) Letter and Category Fluency measures demonstrated cognitive impairment in the 800 mA arm.

Discussion:

The results demonstrated a dissociation of depression (higher amplitudes better) and cognitive (lower amplitudes better) related outcomes. Future work is warranted to elucidate the relationship between amplitude, electric field, neuroplasticity and clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Electroconvulsive therapy, pulse amplitude, depression, cognition

INTRODUCTION

Despite the proven antidepressant efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for depressive episodes (1), neurocognitive impairment remains a major concern of treatment, especially in areas of episodic memory and executive function (2). Demographic (age, premorbid intelligence, years of education), depression severity, and ECT treatment parameters (pulse-width, dose-titration, amplitude, electrode placement) influence ECT-mediated neurocognitive outcomes (3). The impact of variable pulse amplitudes on clinical and cognitive outcomes has yet to be investigated.

Pulse amplitude, which dictates the induced electric field magnitude in the brain, is presently fixed at 800 or 900 milliamperes (mA) with modern ECT devices. However, such fixed amplitude values lack any clinical or scientific rationale (4). Computer modeling has shown that 800 mA pulse amplitude exceeds the neuronal activation threshold of the entire brain by more than six-fold, despite efforts to localize current density by changing electrode placements (5). Further, research in the late 1940s reported effective seizure induction with amplitude values that ranged between 233 to 544 mA (6). Lower pulse amplitudes reduce the magnitude of the induced electric field that could potentially decrease the risk of neurocognitive side effects. Case reports demonstrated that 500 to 600 mA is sufficient to generate seizure induction, although seizure morphology may be poorer compared to standard 800 mA (7, 8). Randomized trials that compared amplitudes assessed seizure efficiency but included no clinical outcomes (9, 10). Recent, small (n = 7–22) investigations have demonstrated that low amplitude ECT results in improvement of depression severity and reduced suicidal thoughts with concordant fewer neurocognitive side effects (11, 12). To date, larger, randomized controlled trials have yet to assess antidepressant and cognitive outcomes over a range of pulse amplitudes.

The present investigation was designed to assess the dose-response relationship between ECT pulse amplitude and antidepressant and cognitive outcomes (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02999269). Subjects were randomized to three different pulse amplitudes: 600, 700 and 800 mA with the latter representing the active comparator. Subjects received clinical, cognitive, and imaging assessments before, during (fixed after the sixth ECT treatment), and after the acute ECT series (variable number of treatments). The overall focus of this investigation was to determine the relationship between hippocampal electric field magnitude, neuroplasticity and clinical outcomes. Here, we report the clinical outcomes as a function of amplitude. Our primary clinical outcomes include depression severity (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale 24-item (HDRS24) total score (13)) and cognition (Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R) Percent Retention Raw Score (14)). In addition to the primary cognitive outcome, we assessed amplitude differences on secondary cognitive measures. We hypothesized that the higher amplitude arms would have a superior antidepressant response with increased cognitive risk.

METHODS

Participants

The University of New Mexico (UNM) Human Research Protections Office (HRPO) approved this investigation. All subjects signed procedural consent or assented to the research protocol with the surrogate medical decision-maker providing consent. Subjects were recruited from December 2016 to September 2019. Subjects had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (single episode or recurrent, non-psychotic or psychotic episodes, diagnosis confirmed with two independent psychiatric evaluations) and met the clinical indication for ECT. Additional inclusion criteria included right-handedness, which was confirmed with the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (15), and an age range between 50 and 80 years of age. This is the optimal age range to investigate targeted medial temporal lobe engagement and clinical outcomes. Older age is associated with an increased probability of antidepressant response (16, 17) and ECT-mediated cognitive impairment (18). Exclusion criteria included neurological or neurodegenerative disorder (e.g., history of head injury with loss of consciousness > 5 minutes, epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease), other psychiatric conditions (e.g., schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder), or substance (except nicotine) or alcohol use disorder, and contraindications to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In order to reduce medication confounds, all subjects tapered and discontinued their scheduled psychotropic medications prior to the baseline assessment, but as-needed medications were permissible for anxiety and insomnia: trazodone (maximal cumulative dose per day: 200mg), lorazepam (3mg) and quetiapine (200mg). All subjects who met eligibility criteria during active enrollment were offered participation in this study.

Clinical and cognitive assessments

Trained raters blinded to treatment-arm assignment performed the clinical and cognitive assessments at each visit. The assessments included the HDRS24 (13). The initial study visit included the ECT Appropriateness Scale to assess the indication for ECT (19), Maudsley Staging Method for Treatment Resistance (20), Medical History form to gauge overall medical burden, and Framingham Stroke Risk Profile to measure vascular burden (21).

The baseline visit included the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), a measure of global cognitive function to screen for preexisting global cognitive impairment (22) and the Test of Premorbid Function (TOPF), an estimate of premorbid intellectual function (23). The remaining cognitive measures were completed at each visit. The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R) measured learning and immediate recall of 12 semantically related words across three learning trials, delayed recall, and recognition memory (14). To minimize practice effects, we used alternate forms of the HVLT-R (Forms 1 and 4) and randomized the order across participants. (24). Following the published HVLT-R manual, we computed the HVLT-R retention raw score for our primary cognitive outcome measure (25). The percent retention score measured hippocampal-dependent memory function and reduced the possibility of over-estimating memory function from immediate and delayed free recall scores (25). The Dot Counting Test measured test-taking effort (26). The Delis Kaplan Executive Function System (DKEFS) measured processing speed, verbal fluency, inhibition, and cognitive flexibility (27). Specific measures from the DKEFS included Verbal Fluency, Category Fluency and Color-Word Interference. The entire neuropsychological battery was well tolerated with a completion time of less than 60 minutes.

Electroconvulsive therapy and study design

All subjects started the ECT series with right unilateral (d’Elia) electrode placement (28). Subjects were randomized and blinded to 600, 700, and 800 mA prior to the first ECT treatment. Subject randomization was completed with a random number generator prior to study initiation with a 1:1:1 ratio for each study arm. As determined by our preliminary data, 500 mA pulse amplitudes compromised efficacy (Supplemental Material Section 1). Subjects received clinical, neuropsychological, and imaging assessments pre- (V1), mid- (after the sixth ECT treatment, V2) and post-ECT (within one week of finishing the ECT series, V3). If subjects were non-responsive to the assigned pulse amplitude (< 25% reduction in from baseline HDRS24 at the second visit), subjects then received bitemporal (BT) electrode placement (800 mA, 1.0 milliseconds (ms) pulse width) for the remainder of the ECT series (29).

Subjects received ultrabrief pulse width (0.3 ms) until a planned interim data analysis (n = 47) to ensure that the experimental arms were equipoise with the active comparator. The analysis demonstrated a trend towards the lower efficacy of the 600 mA arm. We subsequently increased the pulse width from ultrabrief (0.3 ms) to brief (1.0 ms) all treatment arms for the remainder of the study (n = 15). The rationale for the increased pulse width, as approved by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the study Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB), was to improve the efficacy of the lower amplitude arm. The strength-duration curve established that lower pulse amplitudes required longer pulse widths to elicit neuronal activation potential (30, 31). Thus, we reasoned that the increased pulse width may improve the neuronal activation potential and the antidepressant efficacy of the 600 mA arm.

The first ECT session determined individual seizure thresholds with subsequent treatments provided at six times the seizure threshold with similar adjustments to pulse train duration and frequency across all amplitude arms (32) (Supplemental Material Section 2). Further adjustments to charge were permitted to ensure adequate seizure morphology and duration based on clinical judgment. Motor, electroencephalographic, and heart rate parameters were recorded for each treatment. The treating anesthesiologist determined the appropriate dose of methohexital, a general anesthetic, and succinylcholine, a depolarizing neuromuscular blocker.

Statistical Analyses

Clinical and demographic variables were assessed with chi-square or one-way analysis of variance. For the primary outcomes (change in HDRS24 and HVLT-R retention raw score), we performed a full longitudinal model with an unstructured repeated measures covariance matrix on subjects who completed the study in the assigned treatment arm. Missing values for the depression and cognitive variables (14% of values) were imputed using regression multiple imputation with five iterations (33). We completed imputation for seven subjects that did not complete the final post-ECT assessment and for sparse missing cognitive values. When a subject had all their values imputed for a variable, then that subject was removed from the analysis of that variable. In addition, we performed a separate analysis with subjects receiving bitemporal electrode placement between V2 and V3. For depression outcomes, the dependent variable was HDRS at each visit and the independent variables included progress (time within the ECT series: pre-, mid-, and post-ECT), amplitude, age, sex, pulse width and the following interactions: progress/amplitude, progress/sex, and progress/pulse width. For primary cognitive outcomes, the dependent variable was HVLT-R retention scores at each visit with the same model plus the Test of Premorbid Functioning Standard Scores as an additional covariate. In addition to our primary cognitive outcome, we assessed secondary outcomes for the additional cognitive measures using the same cognitive statistical model. Follow-up contrasts included the following: 1) longitudinal changes within each amplitude (e.g., HDRS24 differences in 600 mA subjects between V1 and V2); 2) amplitude contrasts during the mid- and post-ECT assessments (e.g., HDRS24 differences 600 and 700 mA at V2); 3) sex differences; and 4) pulse width differences. The amplitude contrasts were averaged for sex and pulse width with Tukey’s method for multiple pairwise comparisons.

RESULTS

Subject Demographic, Clinical, and Treatment Characteristics

Demographic, clinical, and neuropsychological data are summarized in Table 1 by treatment arm. The average age for the subjects (n = 62; 18 males) was 65.6 years (standard deviation (SD) 8.4). Twenty subjects had a depressive episode with psychotic features, and six had a single episode. The average duration of a depressive episode was 18.0 (SD 21.9) months. The number of previous depressive episodes was 4.1 (SD 3.9), and the average age of depression onset was 36.3 (SD 19.5) years. The lifetime duration of depressive episodes was 7.3 (SD 9.9) years. The average number of antidepressant treatment trials prior to ECT was between 3–4 antidepressant trials reflecting a moderate level of treatment resistance. The ECT Appropriateness Scale of 8.1 (SD 1.5) (maximal score of 10) supported the clinical indication for ECT.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

| Clinical and demographic features | 600mA (n = 20) | 700mA (n = 22) | 800mA (n = 20) | F or χ2 (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age: mean (SD) | 65.5 (8.3) | 64.4 (6.7) | 67.2(10.2) | 0.57 (0.57) |

| Sex: Male/Female | 5/15 | 5/17 | 8/12 | 0.93 (0.63) |

| Single episode/recurrent | 1/19 | 4/18 | 1/19 | 2.82 (0.24) |

| Psychotic/Non-psychotic | 5/15 | 9/13 | 6/14 | 1.28 (0.53) |

| Episode duration (months): mean (SD) | 16.5 (16.5) | 14.2 (20.0) | 23.7 (30.0) | 1.06 (0.35) |

| Number of episodes: mean (SD) | 4.9 (4.8) | 3.14 (3.2) | 4.32 (3.6) | 1.06 (0.35) |

| Age of onset (years): mean (SD) | 36.7 (17.9) | 40.5 (22.4) | 31.2(17.4) | 1.20 (0.31) |

| Lifetime duration (years): mean (SD) | 5.7 (4.3) | 7.3 (11.8) | 8.8 (11.3) | 0.50 (0.61) |

| Framingham Stroke Risk Profile (raw score): mean (SD) | 8.7 (3.9) | 7.6 (4.5) | 8.8 (3.7) | 0.49 (0.61) |

| ECT Appropriateness Scale: mean (SD) | 7.9 (1.7) | 8.4 (1.6) | 8.25 (1.4) | 0.49 (0.61) |

| Maudsley Treatment Failure: mean (SD) | 2.0 (1.1) | 1.9 (1.0) | 2.2 (1.1) | 0.42 (0.66) |

| Baseline MOCA: mean (SD) | 23.4 (3.4) | 24.1 (3.5) | 24.8 (3.0) | 1.00 (0.38) |

| ECT charge and seizure duration | ||||

| Titration step (% n) | 1 (0%) 2 (15%) 3 (60%) 4 (25%) |

1 (4.5%) 2 (54.5%) 3(4.1%) 4 (0%) |

1 (0%), 2 (50%) 3 (50%) 4 (0%) |

17.8 (.007) |

| Titration charge (mC): mean (SD) | 41.0 (21.0) | 32.3 (19.8) | 41.8 (29.4) | 1.06 (0.35) |

| Final step (% n) | 1 (0%) 2 (5%) 3 (40%) 4 (55%) |

1 (0%) 2 (22.7%) 3 (50%) 4 (27.3%) |

1 (0%) 2 (35%) 3 (45%) 4 (20%) |

8.6 (.07) |

| Final charge (mC): mean (SD) | 315.3 (102.2) | 286.7 (146.7) | 313.5 (182.7) | 0.25 (0.78) |

| Average charge (mC): mean (SD) | 241.0 (100.0) | 218.3 (115.5) | 230.3 (139.7) | 0.19 (0.83) |

| RUL treatment number: mean (SD) | 7.8 (2.4) | 8.1 (2.6) | 7.8 (2.8) | 0.14 (0.87) |

| EEG seizure duration (s): mean (SD) | 46.2 (14.8) | 51.2 (16.6) | 52.5 (18.2) | 0.83 (0.44) |

| Baseline Measures | ||||

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale - 24 items: mean (SD) | 36.95 (7.8) | 37.91 (7.5) | 33.75 (6.7) | 1.81 (0.17) |

| Hopkins Verbal Learning Test - Revised Retention Raw Score: mean (SD) | 68.4 (40.4) | 48.7 (36.9) | 59.65 (38.7) | 1.4 (0.26) |

F-statistic degrees of freedom (2, 59)

x2 degrees of freedom (2) for clinical and demographic features

x2 degrees of freedom (6) for titration steps

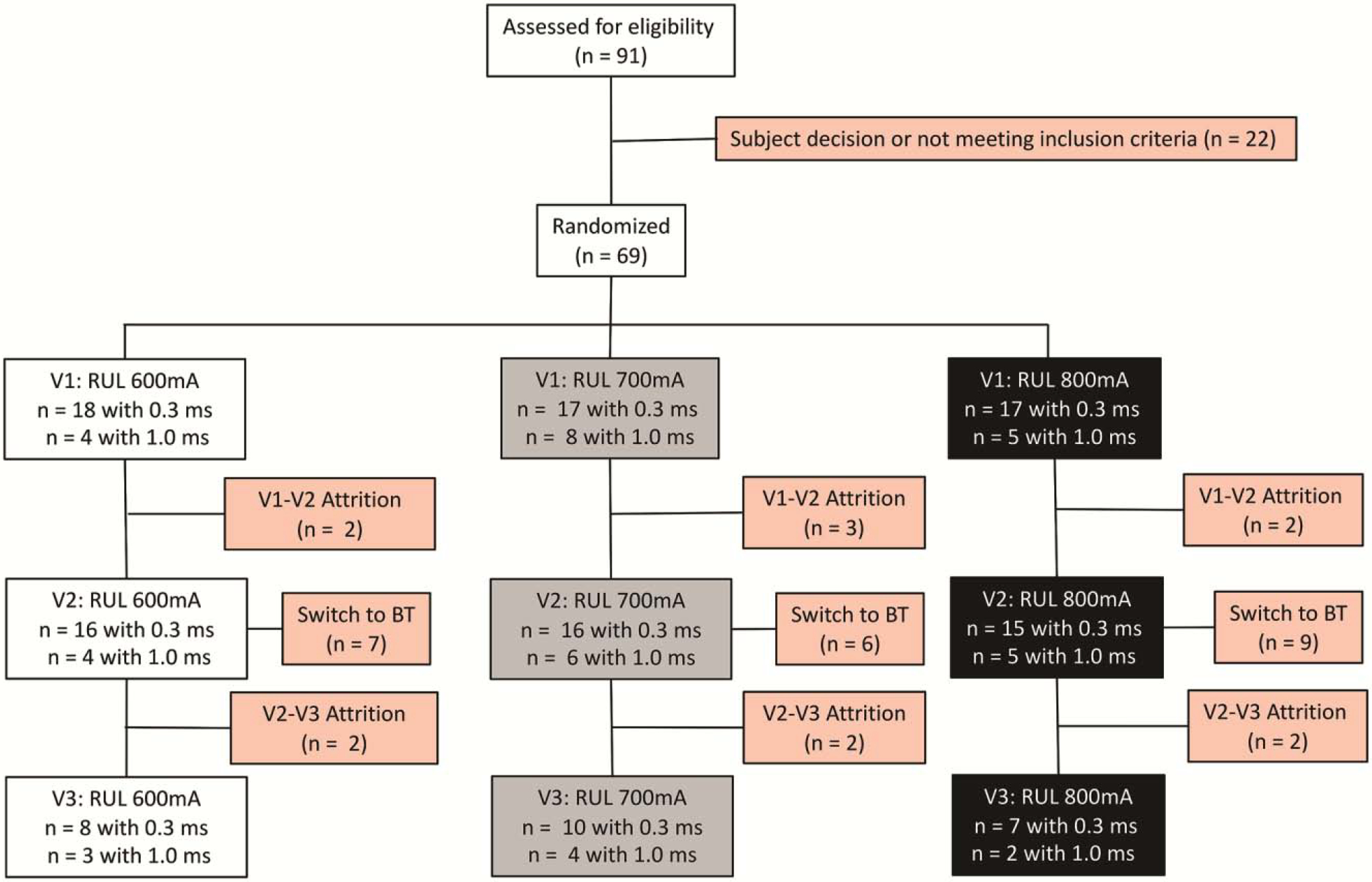

The subject flow is summarized in Figure 1. Subjects received an average of 10.5 (SD 3.3) treatments for the acute ECT series. Treatment arms reflected a difference in the initial titration step (“steps” defined as incremental increases in pulse train duration and frequency to induce seizure activity). The 600 mA arm required the fourth (final or highest) titration step in four of twenty subjects (x2(6) = 17.83, p = 0.007). However, the initial (F2,59 = 1.05, p = 0.35) and final charge (F2,59 = 0.25, p = 0.78) were similar across treatment arms. With the bitemporal electrode placement contingency, the overall response rate was 62.9% (39/62) and the remission rate was 40.3% (25/62). The attrition rate was 21.0% after randomization (13/62), which did not differ across treatment arms (x2(2) = 0.03, p = 0.98). The transition to bitemporal electrode placement was also similar across all treatment arms (x2(2) = 1.5, p = 0.46). Subjects had comparable side effects (headache, muscle aches, nausea) across amplitude arms but no serious adverse events.

Figure 1.

Subject flow from recruitment and screening to the post-ECT assessment.

Depression outcome: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale - 24 item (Figure 2)

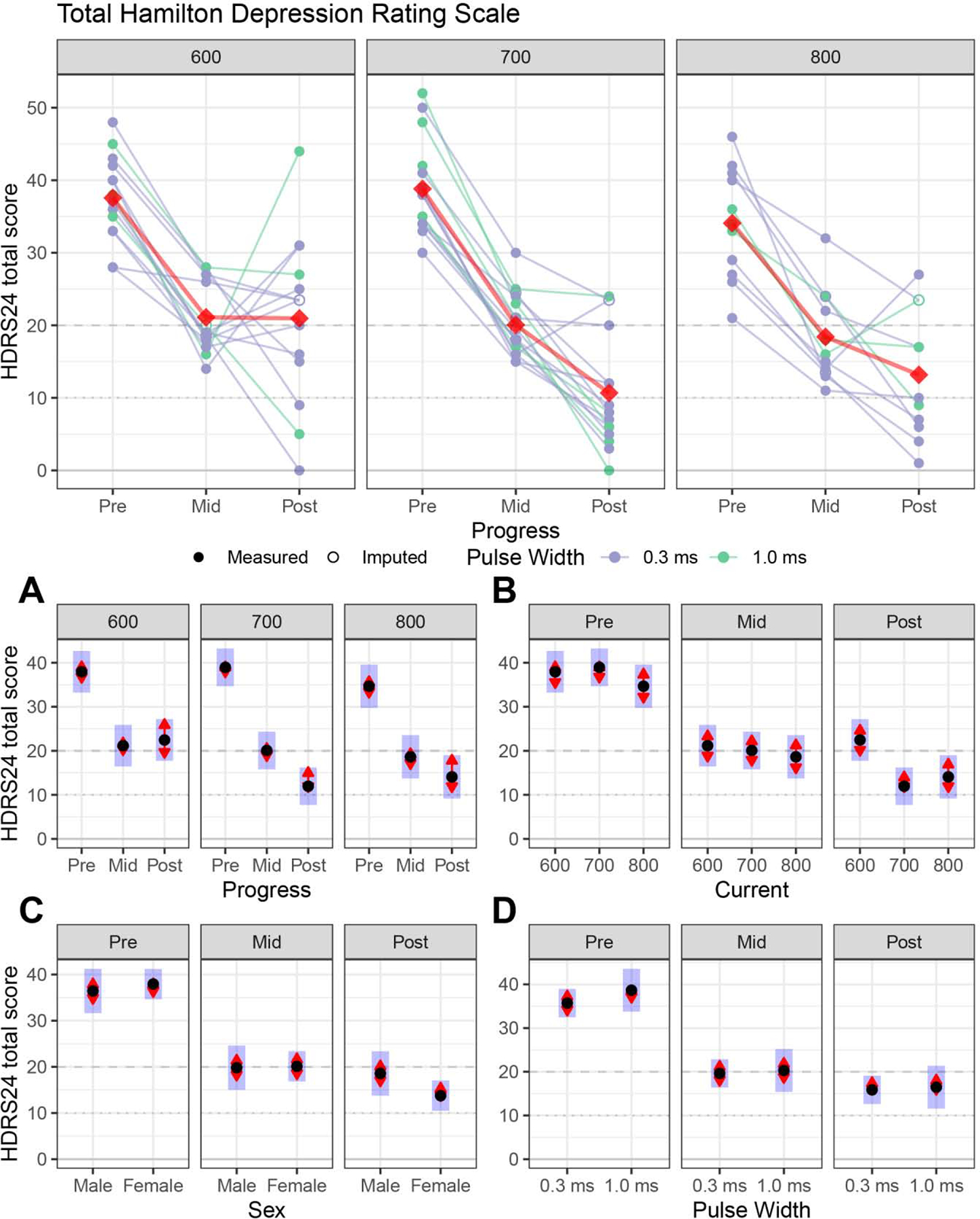

Figure 2:

Primary antidepressant outcome (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale 24-items, HDRS24) for right unilateral electrode placement. For the Figures A, B, C and D: The black dots are estimated marginal means, the blue bars are 95% confidence intervals, and the red arrows are for the comparisons between means; if the red “comparison arrow” from one mean does not overlap an arrow from another group, the difference is significant at a Tukey-HSD corrected significance level.

Figure 2A: Longitudinal changes within each amplitude. The 600, 700 and 800 mA arms had early improvement, but the 600 mA arm had a response plateau after the mid-ECT assessment.

Figure 2B: Amplitude contrasts at each assessment. Relative to the 600 mA arm, the 700 and 800 mA arms had lower (improved) post-ECT depression ratings.

Figure 2C: Sex differences. Male and female subjects did not have differences in depression outcome.

Figure 2D: Pulse width differences. Brief (1.0) and ultrabrief (0.3) pulse widths did not have differences in depression outcome.

Full longitudinal model:

Progress (F2, 72 = 211.43, p < 0.0001), amplitude (F2, 35 = 3.69, p = 0.04) and progress-by-amplitude interaction (F4, 72 = 2.65, p = 0.04) contributed to depression outcomes. Age (F1,35 = 0.46, p = 0.50), sex (F1,35 = 0.89, p = 0.35), pulse width (F1,35 = 0.33, p = 0.57), and the remaining interactions (p > 0.05) did not contribute to depression outcomes.

Longitudinal changes within each amplitude (Figure 2A):

The subjects in the 600 (pre-/post-ECT, t72 = 5.09, p < 0.0001), 700 (pre-/post-ECT, t72 = 9.80, p < 0.0001), and 800 mA (pre-/post-ECT, t72 = 6.44, p < 0.0001) conditions demonstrated improvement in depression severity. Subjects in the 600 mA arm had initial improvement (Pre-/Mid-ECT: t72 = 9.26, p < 0.0001) followed by a response plateau (Mid-/Post-ECT: t72 = −0.41, p = 0.91).

Amplitude contrasts at mid- and post-ECT (Figure 2B):

The mid-ECT contrasts by amplitude were similar (600/700 mA: t35 = 0.39, p = 0.92; 600/800 mA: t35 = 0.81, p = 0.70; 700/800 mA: t35 = 0.47, p = 0.88). The post-ECT contrasts by amplitude demonstrated lower (improved) post-ECT depression ratings in the 700 and 800 mA arms relative to 600 mA arm (600/700 mA: t35 = 3.72, p = 0.002; 600/800 mA: t35 = 2.66, p = 0.03), but the 700 and 800 mA arms did not differ (t35 = −0.70, p = 0.77). By the end of the ECT series, subjects in the 600 mA condition had a final HDRS24 total score 10 and 8 points higher than the 700 and 800 mA arms, respectively.

Sex and pulse width differences (Figures 2C and 2D):

Sex and pulse width had similar response trajectories and depression outcomes (p > 0.05).

Primary cognitive outcome: HVLT-R Retention Raw Score (Figure 3)

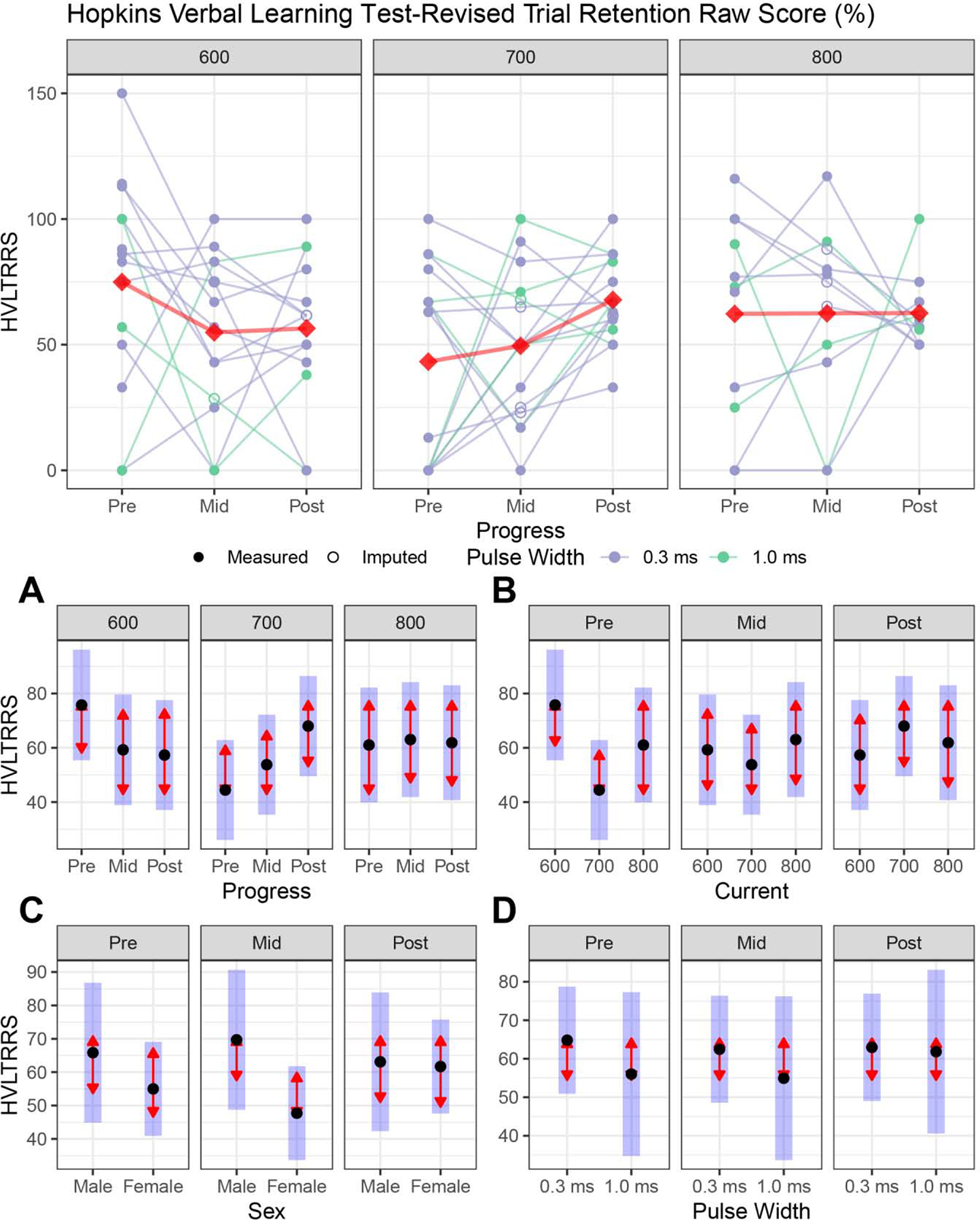

Figure 3:

Primary cognitive outcomes (Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised Retention Raw Scores, HVLT-R Retention Raw Score) for right unilateral electrode placement. For legend, see Figure 2.

Figure 3A: Longitudinal changes within each amplitude. HVLT-R Retention Raw Score performance was similar throughout the ECT series for each amplitude arm (see Figure 2A for figure legend).

Figure 3B: Amplitude contrasts at each assessment: Amplitude arms did not have HVLT-R Retention Raw Score differences at the mid- or post-ECT assessments.

Figure 3C: Sex differences. Male and female subjects did not have HVLT-R Retention Raw Score performance differences.

Figure 3D: Pulse width differences. Brief (1.0) and ultrabrief (0.3) pulse widths did not have HVLT-R Retention Raw Score differences.

Full longitudinal model:

Progress (F2,71 = 0.70, p = 0.50), amplitude (F2,35 = 1.03, p = 0.37), age (F1,35 = 0.74, p = 0.40), sex (F1,35 = 2.51, p = 0.12), pulse width (F1,35 = 0.36, p = 0.55), TOPF-Standard score total (F1,71 = 0.68, p = 0.41), and the interactions (p > 0.05) did not contribute to the HVLT-R Retention scores.

Longitudinal changes within each amplitude (Figure 3A):

All amplitude arms had similar HVLT-R retention performance throughout the ECT series (p > 0.05).

Amplitude contrasts at mid- and post-ECT (Figure 3B):

Mid-, and post-ECT contrasts demonstrated similar HVLT-R retention performance across all amplitude arms (P > 0.05).

Sex and pulse width differences (Figures 3C and 3D):

Sex and pulse width had similar HVLT-R retention score trajectories and outcomes (p > 0.05).

Secondary cognitive outcomes (Figure 4)

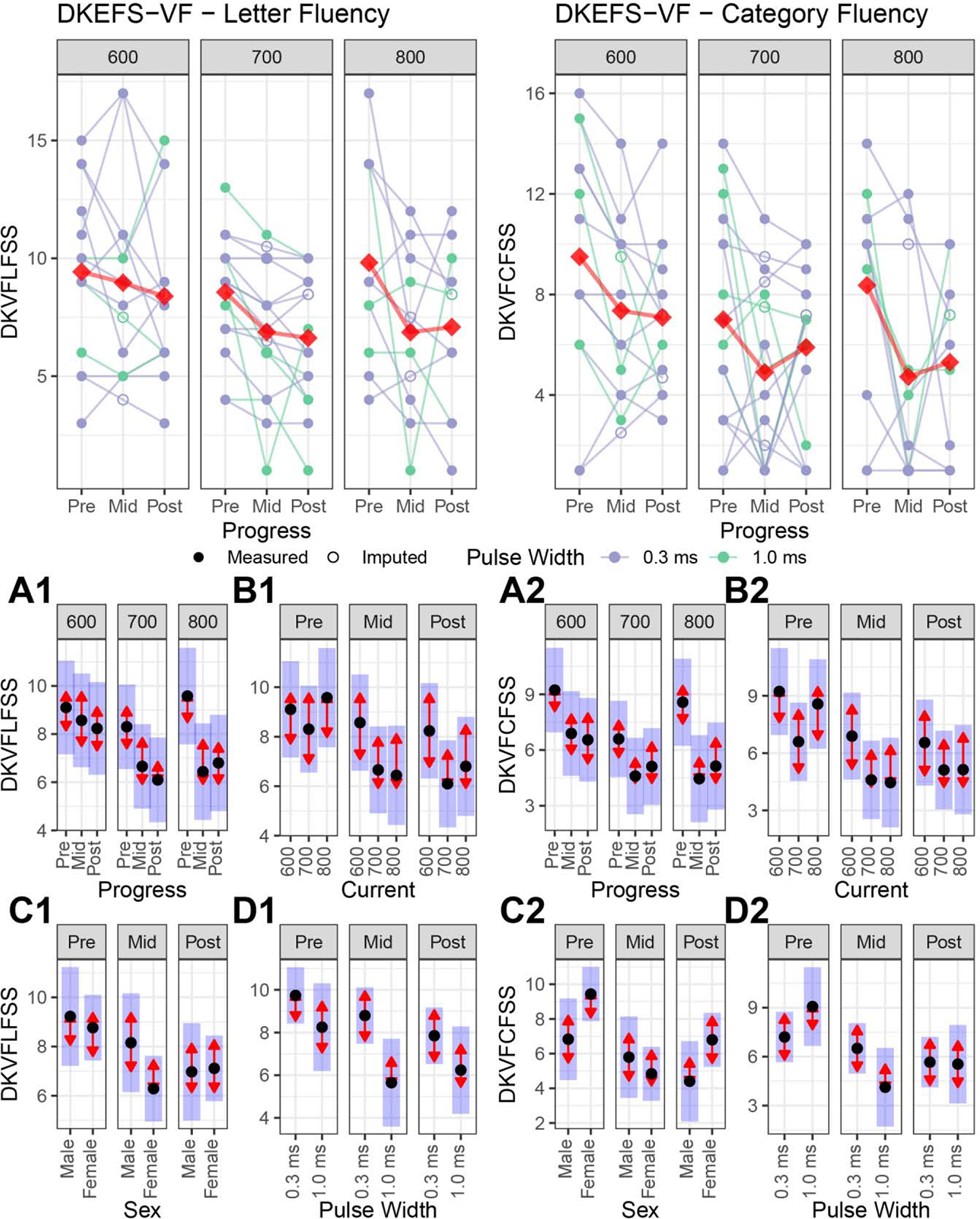

Figure 4:

Secondary cognitive outcomes included the Delis Kaplan Executive Function System (DKEFS) Letter and Category Fluency. For legend, see Figure 2.

Figure 4A: Longitudinal changes within each amplitude. For the Letter Fluency (A1), the 600 mA arm had no change in performance, but the 700 and 800 mA arms had impaired performance. For Category Fluency (A2), the 700 mA arm had no change in performance, but the 600 and 800 mA arms had impaired performance.

Figure 4B: Amplitude contrasts at each assessment: Amplitude arms did not have Letter (B1) or Category (B2) Fluency differences at the mid- or post-ECT assessments.

Figure 4C: Sex differences: Male and female subjects did not have Letter (C1) and Category (C2) Fluency performance differences.

Figure 4D: Pulse width differences. Brief pulse width (1.0 ms) was associated with worse Letter Fluency (D1) at the mid-ECT assessment, but the post-ECT assessment did not demonstrate Letter Fluency differences. Brief (1.0) and ultrabrief (0.3) pulse widths did not have Category Fluency (D2) differences.

We performed a likelihood-ratio test comparing the full model (with the “progress” variable) to the reduced models (without the progress variable and progress interactions). The likelihood ratio test indicates the degree that the progress variable explains the variability in the cognitive response variable. Large text statistics and small p-values indicate a greater relationship with the progress variable and cognitive outcome. Table 2 summarizes these results from most to least sensitive for the detection of ECT-induced cognitive impairment. We focused on the two most sensitive measures for detection of ECT cognitive impairment in our sample, the DKEFS Letter and Category and Fluency tests.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary cognitive measures. The likelihood-ratio test to assess ordered the neuropsychological tests from most to least sensitive to detect ECT-mediated cognitive impairment.

| Neuropsychological test | Likelihood ratio test statistic | Likelihood ratio p-value |

|---|---|---|

| DKEFS Category Fluency Scaled Score | 44.85 | 0.0000 |

| DKEFS Letter Fluency Scaled Score | 28.02 | 0.0018 |

| Dot Counting Mean Ungrouped Time | 20.25 | 0.0270 |

| Dot Counting Mean Grouped Time | 19.32 | 0.0363 |

| DKEFS Category Switching Accuracy Scaled Score | 17.42 | 0.0656 |

| HVLT Total Recall T-score | 17.18 | 0.0705 |

| DKEFS Color Word Interference Condition 3 Scaled Score | 16.39 | 0.0891 |

| DKEFS Color Word Interference Condition 4 Scaled Score | 13.05 | 0.2210 |

| HVLT-R Total Recall Raw Score | 12.52 | 0.2520 |

| HVLT-R Trial 1 Free Recall Raw Score | 12.15 | 0.2750 |

| HVLT-R Delayed Recall Raw Score | 11.56 | 0.3152 |

| HVLT-R Retention Raw Score | 10.29 | 0.4156 |

| HVLT-R Delayed Recall T-Score | 9.22 | 0.5112 |

DKEFS = Delis Kaplan Executive Function System

HVLT-R = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised

Full longitudinal model:

For Letter Fluency, progress (F2,71 = 11.15, p = 0.0001) and the Test of Premorbid Functioning (F1,71 = 15.42, p = 0.0002) contributed to the overall model. For Category Fluency, progress (F2,71 = 16.56, p < 0.0001), Test of Premorbid Functioning (F1,71 = 4.88, p = 0.03), and the progress-by-pulse width interaction (F2,71 = 7.69, p = 0.0009) contributed to the overall model.

Longitudinal changes within each amplitude (Figure 4A):

For the Letter Fluency, the 600 mA arm had no performance change (pre-/post-ECT: t71 = 1.13, p = 0.50). In contrast, the 700 and 800 mA arms had impaired Letter Fluency performance (700 mA pre-/post-ECT: t71 = 3.19, p = 0.006; 800 mA pre-/post-ECT: t71 = 3.46, p = 0.003). For Category Fluency, the 700 mA arm had no performance change (pre-/post-ECT: t71 = 1.53, p = 0.28). The 600 and 800 mA arms had impaired Category Fluency performance (600 mA pre-/post-ECT: t71 = 2.50, p = 0.04; 800 mA pre-/post-ECT: t71 = 3.06, p = 0.009).

Amplitude contrasts at mid- and post-ECT (Figure 4B):

Mid-, and post-ECT contrasts demonstrated similar Letter and Category Fluency performance across all amplitude arms (p > 0.05).

Sex and pulse width differences (Figures 4C and 4D):

For Letter Fluency, sex had similar trajectories and outcomes (p > 0.05). The progress-by-pulse width interaction for Letter Fluency was related to impaired mid-ECT performance for brief pulse width (t35 = 2.67, p = 0.01); the pulse width differences in Letter Fluency were no longer evident post-ECT (t35 = 1.36, p = 0.18). For Category Fluency, sex and pulse width had similar trajectories and outcomes (p > 0.05).

Subjects who were non-responsive to the assigned pulse amplitude received bitemporal electrode placement (800 mA, 1.0 ms pulse width) for the remainder of the ECT series. The bitemporal clinical and cognitive results are presented in Supplemental Material Section 3.

DISCUSSION

This double-blind, randomized clinical trial compared clinical and cognitive outcomes with ECT administered with 600 (experimental), 700 (experimental), and 800 mA (active comparator). The study sample included older subjects (age: 50 to 80 years) with a major depressive disorder who met clinical indications for ECT. Other ECT parameters (frequency, pulse train duration) were fixed within each amplitude arm and based on the initial seizure titration and subsequent adjustments to charge based on clinical judgment. The subjects randomized to the 600 mA arm had worse post-ECT depression outcomes relative to the 700 and 800 mA arms. The primary cognitive outcome, the HVLT-R Retention Raw Score, was insensitive to amplitude-mediated cognitive impairment. However, secondary cognitive outcomes, such as the DKEFS Verbal Fluency variables, were more sensitive to the detection of amplitude mediated neurocognitive impairment in the 800 mA arm. Overall, the results provide new evidence that amplitude is an important ECT parameter that differentially impacts antidepressant (higher amplitudes better) and cognitive (lower amplitudes better) outcomes.

The subjects in the 600 mA arm had inferior post-ECT depression outcomes. Our post-ECT depression outcomes diverge from previous investigations with 500 mA ECT that demonstrated improved depression outcomes (11, 12). The subjects randomized to the 600 mA arm in this study demonstrated an early mid-ECT response (25% reduction in HDRS24) that was equivalent to the 700 and 800 mA arms. The 600 mA subjects’ rate of improvement failed to continue in the second half of the ECT series with equivalent pre- and post-ECT depression outcomes. The reasons for the atypical low amplitude response trajectory are unclear but may be related to placebo response or the modest impact of seizure activity with sub-therapeutic stimulation. All treatment arms had similar seizure duration throughout the ECT series (forthcoming analysis will focus on seizure morphology related to pulse amplitude). Similar to RUL at seizure threshold and bitemporal with ultrabrief pulse width, the ineffectiveness of the 600 mA arm adds to the evidence that seizure activity is “necessary but not sufficient” for clinical response (34). Our results differ from recent low amplitude (500 mA) investigations that demonstrated improvement in depression severity (11, 12). This difference in findings could be related to study methodology as those investigations included relatively younger adult subjects (~ 40 years average), heterogeneous patient samples (mood and psychotic disorders), and different primary endpoints (seizure initiation or suicidality).

Contrary to the a priori hypothesis that the ECT amplitude conditions would have differential effects on memory function, this study found equivalent memory function across all three amplitude conditions. The findings of little change on the HVLT-R are similar with one prior study (35), but are in stark contrast to consistent evidence over the past three decades that have demonstrated that ECT negatively impacts verbal learning and memory (36, 37). The HVLT-R may have less cognitive demand than other complex verbal learning and memory measures (e.g., Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, California Verbal Learning Test) (38, 39), and highlights that ECT may impact memory function through effects on executive function. Indeed, research has found that elderly adults with major depressive disorder have executive dysfunction that moderates memory function (40), thus implicating frontotemporal neurocircuitry that underlies memory performance. While prior ECT research and new neuromodulation therapies (e.g., magnetic seizure therapy) (41) have aimed to minimize stimulation of the hippocampus in order to minimize or avoid memory adverse effects, it is possible that neuromodulation targeting needs to focus on both frontal and temporal lobe structures. As there is limited research regarding the complex association between memory, executive function, and ECT mediated cognitive adverse effect, future research is warranted to discern the underlying mechanisms by which ECT impacts cognition (42). This direction of research is supported by the findings in this study, which are consistent with prior research (36, 37) that ECT adversely impacts executive function, specifically letter (phonemic) fluency, inhibition, and cognitive flexibility.

Several limitations warrant discussion for interpretation of study findings. First, subjects discontinued scheduled antidepressant and antipsychotic medications prior to the first imaging assessment, but as-needed medications (lorazepam, quetiapine, trazodone) were permissible with dose restrictions during the ECT series. Second, our study focused on an older adult sample of ECT subjects (50–80 years) who received RUL ECT. The results may not be generalizable to younger adult ECT patients and other traditional (bitemporal or bifrontal) electrode placements. Third, our response and remission rates were modest and reflected the inclusive nature of subject recruitment (all subjects who met inclusion criteria were offered study participation) and mid-point demonstration of response in order to continue in the assigned treatment arm. Fourth, our study design included a change in pulse width (from 0.3 to 1.0 ms). The hypothesized rationale of increased efficacy in the lower amplitude arm with an increased pulse width (see Methods) was not supported. However, each amplitude arm had a very limited number of subjects with brief pulse width. The relationship between amplitude and pulse width will require more research.

The trade-off between clinical (improved with higher amplitudes) and cognitive (improved with lower amplitudes) outcomes demonstrates the trade-off between antidepressant and cognitive outcomes related to pulse amplitude. The majority of the subjects (n = 60) participated with neuroimaging acquisitions aligned with each clinical and cognitive assessment. Structural imaging (to be reported later) will determine electric field modeling for each subject and demonstrate significant variability within and overlap between each amplitude arm. Future work will address the translational implications of electric field variability within each amplitude arm. The “sweet spot” of antidepressant response and no cognitive impairment may be possible with individualized and precision amplitude dosing.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

What is the primary question addressed by this study?

What is the relationship between ECT pulse amplitude and antidepressant and cognitive outcomes?

What is the main finding of this study?

The subjects randomized to the 600 mA arm had worse post-ECT depression outcomes relative to the 700 and 800 mA arms. The primary cognitive outcome, the HVLT-R Retention Raw Score, was insensitive to amplitude-mediated cognitive impairment. The secondary cognitive outcomes, such as the DKEFS Verbal Fluency variables, were sensitive to the detection of amplitude mediated neurocognitive impairment in the 800 mA arm.

What is the meaning of the finding?

Overall, the results provide new evidence that amplitude is an important ECT parameter that differentially impacts antidepressant (higher amplitudes better) and cognitive (lower amplitudes better) outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: BRAIN Initiative (U01 MH111826, PI Abbott), National Institute of Mental Health Intramural Research Program (ZIAMH002955, PI Deng), Brain & Behavioral Research Foundation NARSAD Young Investigator Award (26161, PI Deng), and National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH119285, PI McClintock) supported this invesgiation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All authors report no disclosures to report.

Supplemental Material

1. Section 1: Preliminary data with 500 mA subjects

2. Section 2: Study-specific titration tables

3. Section 3: Bitemporal electrode placement depression and cognitive outcomes

References

- 1.UK ECT Review Group: Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2003; 361:799–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semkovska M,McLoughlin DM: Objective cognitive performance associated with electroconvulsive therapy for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biological psychiatry 2010; 68:568–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClintock SM, Choi J, Deng ZD, et al. : Multifactorial determinants of the neurocognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT 2014; 30:165–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peterchev AV, Rosa MA, Deng ZD, et al. : Electroconvulsive therapy stimulus parameters: rethinking dosage. J ECT 2010; 26:159–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng ZD, Lisanby SH,Peterchev AV: Electric field strength and focality in electroconvulsive therapy and magnetic seizure therapy: a finite element simulation study. J Neural Eng 2011; 8:016007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liberson WT: Brief stimulus therapy; psysiological and clinical observations. The American journal of psychiatry 1948; 105:28–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosa MA, Abdo GL, Lisanby SH, et al. : Seizure induction with low-amplitude-current (0.5 A) electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT 2011; 27:341–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayur P, Harris A,Gangadhar B: 500-mA ECT--A Proof of Concept Report. J ECT 2015; 31:e23–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chanpattana W: Seizure threshold in electroconvulsive therapy: Effect of instrument titration schedule. German Journal of Psychiatry 2000; [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swartz CM, Krohmer R,Michael N: ECT stimulus dose dependence on current separately from charge. Psychiatry research 2012; 198:164–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Youssef NA,Sidhom E: Feasibility, safety, and preliminary efficacy of Low Amplitude Seizure Therapy (LAP-ST): A proof of concept clinical trial in man. J Affect Disord 2017; 222:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Youssef NA, Ravilla D, Patel C, et al. : Magnitude of Reduction and Speed of Remission of Suicidality for Low Amplitude Seizure Therapy (LAP-ST) Compared to Standard Right Unilateral Electroconvulsive Therapy: A Pilot Double-Blinded Randomized Clinical Trial. Brain Sci 2019; 9: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton M: Rating depressive patients. The Journal of clinical psychiatry 1980; 41:21–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandt J,Benedict R: Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised: Professional Manual, Florida, PAR, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oldfield RC: The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 1971; 9:97–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tew JD Jr., Mulsant BH, Haskett RF, et al. : Acute efficacy of ECT in the treatment of major depression in the old-old. The American journal of psychiatry 1999; 156:1865–1870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Connor MK, Knapp R, Husain M, et al. : The influence of age on the response of major depression to electroconvulsive therapy: a C.O.R.E. Report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 9:382–390 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Squire LR,Chace PM: Memory functions six to nine months after electroconvulsive therapy. Archives of general psychiatry 1975; 32:1557–1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kellner CH, Popeo DM, Pasculli RM, et al. : Appropriateness for electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) can be assessed on a three-item scale. Medical hypotheses 2012; 79:204–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fekadu A, Wooderson S, Donaldson C, et al. : A multidimensional tool to quantify treatment resistance in depression: the Maudsley staging method. The Journal of clinical psychiatry 2009; 70:177–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Agostino RB Sr., Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. : General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008; 117:743–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. : The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool For Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 2005; 53:695–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wechsler D: Test of Premorbid Functioning, San Antonio, TX, The Psychological Corporation, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benedict RH: Effects of using same- versus alternate-form memory tests during short-interval repeated assessments in multiple sclerosis. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS 2005; 11:727–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark JH, Hobson VL,O’Bryant SE: Diagnostic accuracy of percent retention scores on RBANS verbal memory subtests for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2010; 25:318–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boone KB, Lu P,Herzberg D: Rey Dot Counting Test, Los Angeles, Western Psychological Services, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delis DC, Kaplan E,J K: Delis Kaplan Executive Function System, San Antonio, TX, The Psychological Corporation, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 28.d’Elia G: Unilateral electroconvulsive therapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1970; 215:1–98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kellner CH, Knapp R, Husain MM, et al. : Bifrontal, bitemporal and right unilateral electrode placement in ECT: randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry 2010; 196:226–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sackeim HA, Long J, Luber B, et al. : Physical properties and quantification of the ECT stimulus: I. Basic principles. Convulsive therapy 1994; 10:93–123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nowak LG,Bullier J: Axons, but not cell bodies, are activated by electrical stimulation in cortical gray matter. I. Evidence from chronaxie measurements. Exp Brain Res 1998; 118:477–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Devanand DP, et al. : A prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison of bilateral and right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy at different stimulus intensities. Archives of general psychiatry 2000; 57:425–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sv Buuren,Groothuis-Oudshoorn K: mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software. Journal of Statistical Software 2011; 45:1–67 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sackeim HA: Is the Seizure an Unnecessary Component of Electroconvulsive Therapy? A Startling Possibility. Brain Stimul 2015; 8:851–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vasavada MM, Leaver AM, Njau S, et al. : Short- and long-term cognitive outcomes in patients wtih major depression treated wtih electroconvulsive therapy. Journal of ECT 2017; 33:278–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Semkovska M,McLoughlin DM: Objective Cognitive Performance Associated with Electroconvulsive Therapy for Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biological Psychiatry 2010; 68:568–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lisanby SH, McClintock SM, Alexopoulos G, et al. : Neurocognitive Effects of Combined Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) and Venlafaxine in Geriatric Depression: Phase 1 of the PRIDE Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2020; 28:304–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lacritz LH, Cullum CM, Weiner MF, et al. : Comparison of the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised to the California Verbal Learning Test in Alzheimer’s Disease. Applied Neuropsychology 2001; 8:180–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lacritz LH,Cullum CM: The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test and CVLT: A Preliminary Comparison. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 1998; 13:623–628 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Butters MA, Young JB, Lopez O, et al. : Pathways linking late-life depression to persistent cognitive impairment and dementia. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2008; 10:345–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daskalakis ZJ, Dimitrova J, McClintock SM, et al. : Magnetic seizure therapy (MST) for major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McClintock SM, Choi J, Deng ZD, et al. : Multifactorial determinants of the neurocognitive effecdts of electroconvulsive therapy. Journal of ECT 2014; 30:165–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.