Abstract

Increased striatal dopamine synthesis capacity has consistently been reported in patients with schizophrenia. However, the mechanism translating this into behavior and symptoms remains unclear. It has been proposed that heightened striatal dopamine may blunt dopaminergic reward prediction error signaling during reinforcement learning. In this study, we investigated striatal dopamine synthesis capacity, reward prediction errors, and their association in unmedicated schizophrenia patients (n = 19) and healthy controls (n = 23). They took part in FDOPA-PET and underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanning, where they performed a reversal-learning paradigm. The groups were compared regarding dopamine synthesis capacity (Kicer), fMRI neural prediction error signals, and the correlation of both. Patients did not differ from controls with respect to striatal Kicer. Taking into account, comorbid alcohol abuse revealed that patients without such abuse showed elevated Kicer in the associative striatum, while those with abuse did not differ from controls. Comparing all patients to controls, patients performed worse during reversal learning and displayed reduced prediction error signaling in the ventral striatum. In controls, Kicer in the limbic striatum correlated with higher reward prediction error signaling, while there was no significant association in patients. Kicer in the associative striatum correlated with higher positive symptoms and blunted reward prediction error signaling was associated with negative symptoms. Our results suggest a dissociation between striatal subregions and symptom domains, with elevated dopamine synthesis capacity in the associative striatum contributing to positive symptoms while blunted prediction error signaling in the ventral striatum related to negative symptoms.

Keywords: psychosis, reinforcement learning, computational psychiatry, PET, reversal learning, fMRI

Introduction

In schizophrenia, a hyperdopaminergic state in the striatum is a cornerstone in the neurobiological explanation of the disorder.1 Firstly, anti-dopaminergic neuroleptics are known to reduce psychotic symptoms. Secondly, there is meta-analytic evidence for increased presynaptic striatal dopamine function of schizophrenia patients,2,3 presumably mainly in the associative striatum.4 Nevertheless, there is heterogeneity concerning this hyperdopaminergic state in Sz,5 which challenges its interpretation as either a symptomatic state marker of psychosis or a longer enduring trait of schizophrenia. In favor of the “state” interpretation, striatal dopamine levels were associated with the degree of positive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia as well as bipolar disorder6 and decreased in schizophrenia patients in remission of positive symptoms.7 However, anti-dopaminergic medication did not affect the presynaptic dopamine levels in patients in one study in first-episode patients,8 suggesting that dopaminergic alterations might be a trait marker. Moreover, patients with comorbidities such as substance addictions showed decreased striatal dopamine release; however, amphetamine-induced dopamine release still correlated with increase in positive symptoms.9 Furthermore, some patients show psychotic symptoms while displaying normal or even decreased dopamine levels.10–12 This heterogeneity is still not fully understood.

How heightened striatal dopamine translates into schizophrenia symptoms in terms of cognition and behavior, ie, its functional role still remains to be elucidated. In that sense, many authors have proposed disturbed prediction errors as a mediating mechanism.13–16 In reinforcement learning, initially neutral cues gain values via associative pairing with a rewarding outcome. The reward prediction error serves as a teaching signal for updating these values reflecting the trial-by-trial difference between the perceived outcome and the expectation17–19 and thus mark relevant environmental events. In animal studies, phasic firing rates of dopaminergic midbrain neurons projecting to the striatum20,21 were found to reflect such reward prediction errors. In humans, the striatal BOLD response is interpreted to reflect such reward prediction error signals, which were found to be affected by (anti)dopaminergically acting agents. For instance, whereas L-DOPA increased striatal reward prediction error signals,22 they were decreased following methamphetamine23 as well as after dopamine antagonists.24 It was proposed that dysregulated striatal dopamine turnover, as reflected in heightened dopamine synthesis, may enhance the associability of events even if those were merely coinciding.25 In the same vein, heightened dopamine synthesis may cause spontaneous, not stimulus-driven dopamine release acting as prediction errors. Thus, in the absence of relevant stimuli such prediction error signals may cause the attribution of meaningfulness to coinciding, but actually irrelevant stimuli.13–16 While this theory has been influential in explaining positive symptoms, dysregulated dopamine release may also contribute to negative symptoms. The proposedly chaotic nature of prediction error signaling may reduce signal-to-noise ratio, and thus, prediction errors to actually relevant events may stand out less causing devaluation of relevant outcomes, which may reduce motivation and increase motivational negative symptoms.16 Human imaging studies reported striatal BOLD prediction error signaling to be decreased in schizophrenia patients receiving no antipsychotic medication26–28 (but see Ermakova et al29) and in youth at clinical high-risk for psychosis,30 whereas findings in medicated patients are more heterogeneous.31–36 Further brain regions, such as midbrain or DLPFC also showed reduced prediction error coding in patients with schizophrenia.29

To our knowledge, the proposed relationship between increased striatal dopamine synthesis and blunted reward prediction error signals has not been directly probed in patients with schizophrenia so far. This proposedly inverse relationship differs from what has been reported in healthy individuals. In the healthy state, dopamine synthesis capacity was positively associated with working memory37,38 and goal-directed decision making.39 Based on the literature, the relationship between dopamine and cognitive capacities might follow an inverted U-shape, ie, being positively directed in a low dopamine range and negatively at higher or even pathological levels.40

In the current study, we investigate the potential relationship between striatal dopamine synthesis capacity and striatal reward prediction error signaling in unmedicated patients with schizophrenia as well as in healthy controls. We measured dopamine synthesis capacity using positron emission tomography (PET) with [18F]Fluoro-3,4-dihydroxyphenyl-l-alanine (FDOPA). The striatal prediction error signal was assessed during a reversal-learning task via functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Compared to controls, we expected schizophrenia patients to display lower striatal reward prediction error signaling, higher striatal dopamine synthesis capacity, and an inverse relation between both measures.

Methods

Sample Characteristics

In order to measure striatal dopamine synthesis capacity, 20 unmedicated schizophrenia patients and 23 healthy controls (matched for age and gender) underwent fluorine-18-l-dihydroxyphenylalanine (18F-DOPA PET) PET. The sample size was based on a power-calculation assuming a large effect size41 with a power of 0.8 for the difference in striatal Kicer between schizophrenia patients and controls. In a separate fMRI session (days between PET and fMRI scan: mean = 15.5, median = 5, min = 1, max = 84), participants performed a reversal-learning paradigm (n = 21 patients [3 without PET] and n = 23 controls). Following exclusion due to structural abnormalities (n = 1 patient) and invalid behavioral responses during fMRI (n = 1 patient), the final PET sample included 19 unmedicated schizophrenia patients and 23 healthy controls (table 1), the fMRI sample also comprised 19 unmedicated schizophrenia patients and 23 healthy controls, and the overlapping PET and fMRI sample consisted of 16 patients and 23 controls. All patients met the ICD-10 criteria for the diagnosis of schizophrenia and were free of medication for at least 5 half-lives of previous antipsychotic treatment. We did not control for reasons why patients who had been medicated in the past discontinued antipsychotic medication. Schizophrenia patients were recruited at the inpatient and outpatient units as well as at the rescue centers of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy Campus Charité Mitte of the Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin as well as from the Psychiatric Schlosspark-Klinik Berlin. Verbal IQ was assessed using the Wortschatztest (vocabulary test).42 Controls reported no past or present Axis I disorder according to the Structural Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV.43 Exclusion criteria were general contraindications for MRI (eg, metal implants, pacemakers, claustrophobia). Psychopathology was assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)44 where we chose to use the 5 factors version due to better construct validity based on factor analytic evidence (positive [4 items], negative [6 items], disorganized/concrete [3 items], excited [4 items] and depressed [3 items] symptoms; please see supplementary table S1 for standard PANSS solution).45 Based on medical reports by the treating psychiatrists, patients had no current or past history of drug dependence, although patients reported consumption of alcohol (n = 7), THC (n = 6), and amphetamines (n = 4) meeting criteria for abuse according to ICD-10 (this information was not available for 2 patients; supplementary figure S1). We performed clinical evaluation and, if necessary, urine testing in order to detect possible current drug use. All participants gave written informed consent and received monetary compensation for study participation as well as the wins in the fMRI paradigm. The study was approved by the local medical ethics committee of the Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Table 1.

Demographics and Psychopathology of PET Sample

| Unmedicated Schizophrenia Patients (N = 19) | Healthy Individuals (N = 23) | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 12 males, 7 females | 16 males, 7 females | Χ 2(1) = 0.192, P = .661 |

| Age (y) | 33.2 ± 9.5 y (20–56) | 32.2 ± 8.2 (20–50) | t(37) = 0.365, P = .717 |

| Verbal IQ | 96.7 ± 10.3 (80–110) | 105.2 ± 7.3 (85–115) | t(35) = 3.0, P = .005 |

| Medication status | n = 6 drug-naïve n = 13 unmedicated | ||

| Duration of illness (y) | 4.6 ± 5.3 (0–18) | ||

| Age of illness onset (y) | 28.2 ± 10.7 (15–51) | ||

| 5F-PANSSa positive | 15.3 ± 3.4 (8–21) | ||

| 5F-PANSSa negative | 24.5 ± 5.2 (14–33) | ||

| 5F-PANSSa disorganized | 11.6 ± 2.7 (8–20) | ||

| 5F-PANSSa excited | 11.2 ± 2.7 (8–17) | ||

| 5F-PANSSa depressed | 10.6 ± 2.3 (7–15) | ||

| 5F-PANSSa total | 73.1 ± 10.9 (49–95) |

Note: Mean ± SD (minimum-maximum). PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

a5F-PANSS referring to the consensus 5 factors structure reported by Wallwork and colleagues.45

PET: Dopamine Synthesis Capacity

Dopamine synthesis capacity was characterized quantitatively by the FDOPA utilization rate constant Kicer (min−1) estimated by the graphical tissue-slope intercept method with the cerebellum (mask derived from WFU Pickatlas excluding the vermis) as reference region.46,47 The Patlak tissue-slope intercept method was applied on a voxel-by-voxel basis to the dynamic FDOPA-PET image frames (from 20 to 60 min after intravenous FDOPA injection). The parametric Kicer maps were spatially normalized to the anatomical space of the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) based on spatial normalization of the coregistered individual anatomical T1 images using the unified segmentation approach of SPM.48 Kicer values were extracted from 3 volumes of interest (VOI): limbic/ventral, sensorimotor, and associative striatum,49 separately for both hemispheres (for a depiction of these VOIs, see supplementary short animation). Group differences in mean Kicer values of those 6 VOIs were evaluated using a multivariate ANOVA with group (patients vs controls) as between-subjects factor.

Based on previous findings suggesting a bias through moderating effects of drug abuse on presynaptic dopamine function,9,50 we carried out exploratory linear regression analyses predicting striatal dopamine levels (for each of the 6 VOIs). As predictors, we entered comorbid substance abuse status coded with 3 dummy variables (alcohol, THC, amphetamines) as well as group (controls, patients). Note that none of the controls fulfilled ICD-10 criteria for substance abuse. Therefore and in order to rule out that effects of substance abuse on Kicer were not solely driven by controls we repeated the linear regression analyses in schizophrenia patients only.

Reversal Learning Task

In this task consisting of 160 trials, participants had to choose one out of 2 cards that probabilistically (0.8/0.2) led to wins or losses and these contingencies reversed several times. For a more detailed description of the task, see figure 1A, the supplementary material or the original publication.51 We tested for group differences in choosing the currently correct (=80% rewarded) card, the amount of missed trials as well as in repeating a choice after wins (“win-stay”) and switching after losses (“lose-shift”) using 2-sample t-tests (2-sided; 0.05 P-value threshold for statistical significance). Individual trial-by-trial choice data were analyzed using computational modeling techniques. The total model space contained 6 Rescorla Wagner learning models for prediction error (; equation 1) based updating of cue-action values (; equation 2), describing the probability of winning when choosing the respective stimulus.

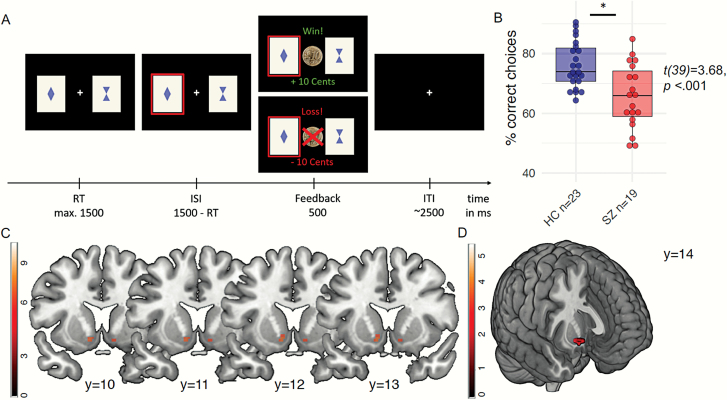

Fig. 1.

(A) Depiction of reversal learning paradigm. Every trial, subjects had to choose one out of 2 cards in order to receive either a win (+10 Eurocents) or a loss (-10 Eurocents). The cue-outcome contingencies were perfectly anti-correlated (0.8/0.2 rewards) and reversed several times following a longer stable period in the beginning and remained stable again at the end of the paradigm. (B) Reinforcement learning. Schizophrenia patients chose the correct option less often than healthy controls. (C) Striatal reward prediction error. Main effect of reward prediction error signaling across all participants in the bilateral ventral striatum (left: [−10/12/−8], t = 7.11, PFWE-corrected for the whole brain = .001; right: [10/12/10], t = 6.3, PFWE-corrected for the whole brain = .013; displayed at t > 6). (D) Reward prediction error group difference. Schizophrenia patients displayed decreased reward prediction error signaling compared to healthy controls ([12/14/−10], t = 3.43, PSVC for striatal PE = .011; displayed at t > 3).

| (1) |

| (2) |

The value trajectories estimated by the learning model were transformed into choice generation via a softmax with a free parameter for inverse decision noise (equation 3).

| (3) |

We set up a model-space containing 6 models, which either contained one learning rate (alpha) or 2 separate learning rates for win and loss trials (alpha win and alpha loss) and which differed in the value update of the unchosen cue, ie, no update of the unchosen option (single update), full update of the unchosen option (reflecting the anti-correlated task structure; full double update), and individual-weighted double update (by the free parameter κ). Please see the Supplementary for a more detailed description of the model space and priors (supplementary table S3).

FMRI: Striatal Prediction Error Analyses

For information on the fMRI sequence, preprocessing and first-level analysis (using SPM12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/), see the supplementary material. The individual trial-by-trial prediction error trajectory from the best-fitting model (SU-1alpha) was introduced as a parametric modulator on the single-subject-level. For group-level analysis, the individual contrast images for prediction errors were used in a 2-sample t-test for between-group comparisons (controls vs patients). Results are reported using FWE correction at the voxel level across the whole brain. The search volume for group comparisons and correlational analyses was restricted to voxels showing a significant main effect for reward prediction error signaling in the ventral striatum (PFWE-corrected < .05; total of 42 voxels centered around [−11/10/−9] and [11/12/−10]) across the entire sample.

Association Between PET Dopamine Synthesis Capacity and fMRI Reward Prediction Error Signal

In order to probe the association between striatal dopamine synthesis capacity and reward prediction error signaling, we carried out voxel-based analyses in SPM with the reward prediction error contrast images compared between groups with Kicer values entered as a covariate. Due to the limbic localization of the prediction error signal, we entered the individual Kicer values of the limbic striatum as covariates in 2 separate analyses for the left and right hemispheres, respectively. We probed the interaction of group (patients vs controls) with Kicer values (F-contrast), and followed up significant findings with post hoc t-tests within groups. We used small volume correction for the voxels in the unilateral striatum showing a main effect of prediction error signaling and applied Bonferroni-correction for multiple testing.

Association With Symptoms

In an exploratory approach, we probed the associations between psychopathology and striatal prediction error signals as well as with Kicer values using the positive and negative symptoms scale of the 5-factor PANSS-solution.45 For association with the fMRI reward prediction error signal, the respective PANSS factor scores were entered as covariates in separate 1-sample t-tests within SPM. Associations between Kicer values and PANSS scores were tested using Pearson correlation within SPSS25. For visualization and plotting we used the ggplot2-package in RStudio version 1.2.1555 and R version 3.6.0.

Results

Dopamine Synthesis Capacity: Kicer

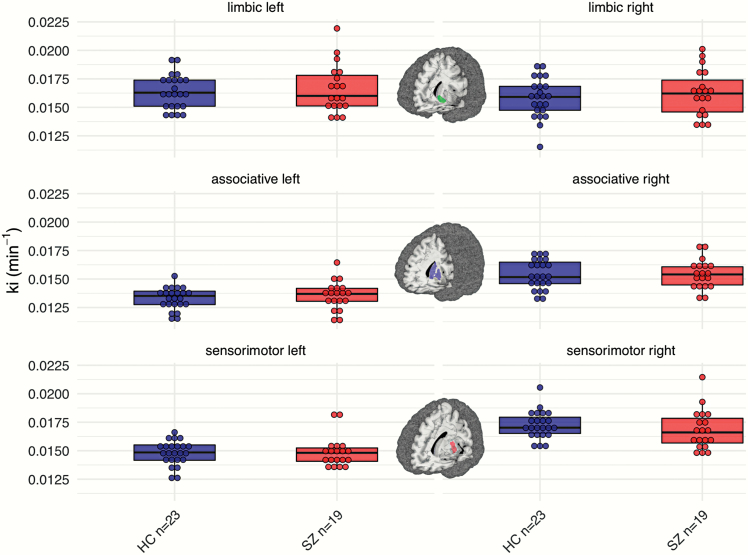

Schizophrenia patients and controls did not differ significantly in their striatal dopamine synthesis capacity (effect of group: F = 0.57, P = .46; figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Dopamine synthesis capacity. Patients with schizophrenia (the right/red boxplots within each panel) and controls (the left/blue boxplots) did not differ significantly in any of the striatal subregions (F = 0.64, P = .70). The brain figures depict the respective striatal subregion that was used for the parameter extraction of Kicer49 (for visualization purposes, data-points were stacked and binned with a bin-width of 0.0005).

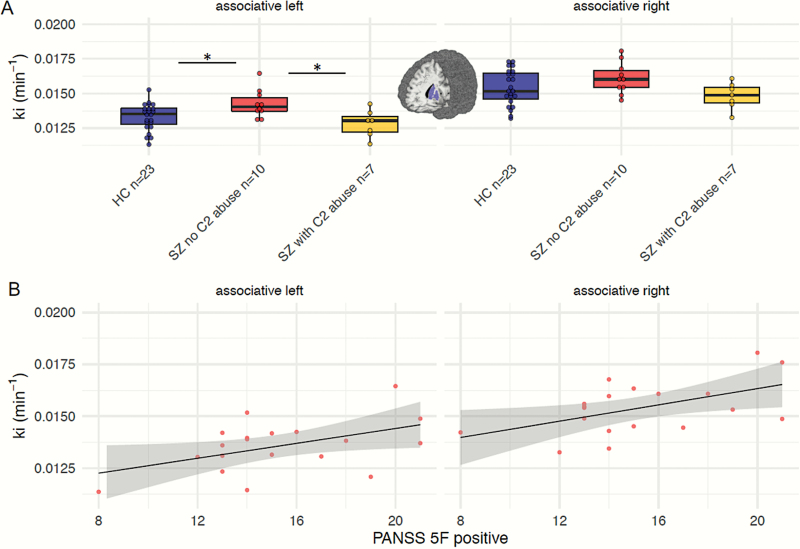

In exploratory analyses, we probed the moderating effects of comorbid drug abuse on presynaptic dopamine function9,50 using linear regression analyses. These regression models significantly explained variance in Kicer values of the left associative striatum (adjusted R2 = .17, F = 3.0, P = .031, betaAlcohol = −0.54, t = 3.11, P = .004; betagroup = 0.35, t = 1.85, P = .073; other betas P > .2) and left sensorimotor striatum (adjusted R2 = .21, F = 3.6, P = .015, betaAlcohol = −0.58, t = 3.39, P = .002; betaTHC = 0.31, t = 1.85, P = .074; other betas P > .3; other regression models P > .28). Repeating these regression analyses excluding controls revealed similar effects; diagnosis of alcohol abuse significantly predicted lower Kicer in the left associative striatum (adjusted R2 = .31, F = 3.7, P = .051, betaAlcohol = −0.64, t = 3.03, P = .01) and the left sensorimotor striatum (adjusted R2 = .42, F = 4.87, P = .018, betaAlcohol = −0.66, t = 3.43, P = .04). We followed up on these findings using post hoc Mann Whitney U-tests. Schizophrenia patients without alcohol abuse presented increased Kicer values in the left associative striatum compared to controls (U = 101.0, P = .033, Bonferroni-corrected for multiple testing) as well as compared to schizophrenia patients with alcohol abuse (U = 9, P = .03, Bonferroni-corrected; figure 3A). In the left sensorimotor striatum of schizophrenia patients, Kicer was higher in those without alcohol abuse compared to those with alcohol abuse (U = 6, P = .009, Bonferroni-corrected; supplementary figure S2). Patients with and without alcohol abuse did not significantly differ in clinical and demographic characteristics nor in psychopathology (supplementary table S2).

Fig. 3.

(A) Post hoc Kicer comparison between 3 subgroups. Splitting the schizophrenia sample into patients without and with comorbid alcohol abuse revealed that patients without alcohol abuse displayed increased Kicer-values in the left associative striatum compared to healthy individuals (HC; P = .033, Bonferroni-corrected) as well as to schizophrenia patients with alcohol abuse (P = .03, Bonferroni-corrected). (B) Positive symptoms from the 5-factor solution of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) were associated with higher dopamine synthesis capacity in the left (r = .48, P = .037) and right (r = .52, P = .023) associative striatum.

Reversal Learning and Striatal Reward Prediction Error Signaling

In the reversal learning paradigm, patients chose the correct option less often than healthy individuals (t = 3.7, P = .001), showed less win-stay behavior (t = 3.78, P = .001) and switched more often after losses (t = 2.2, P = .037; supplementary table S4 and figure 1B). We applied computational modeling to describe single-trial behavior comparing different reinforcement learning models and found that a single-update model with one learning rate explained the data best in both groups (for model comparison, see supplementary material). The inverse decision noise was decreased in schizophrenia patients (t = 3.0, P = .004), whereas the learning rate did not differ between groups (t = 2.9, P = .77) (supplementary material).

Reward prediction errors were coded across several brain areas, such as bilateral striatum, anterior orbital gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, angular gyrus, anterior and middle cingulate cortex, anterior insula, and cerebellum (all at PFWE-corrected for the whole brain = .05). See supplementary table S6 for all brain regions showing a main effect for the reward prediction error signal. Within the scope of this study, we focused on the reward prediction error BOLD response in the bilateral ventral striatum which was significantly activated in both healthy controls and patients with schizophrenia (main effect left: [−10/12/−8], t = 7.11, PFWE-corrected for the whole brain = .001; right: [10/12/10], t = 6.3, PFWE-corrected for the whole brain = .013; figure 1C; see supplementary material, section 2.2 for significant within-group effects). Across the whole brain, there was no group difference in reward prediction error signaling (supplementary material). Schizophrenia patients displayed decreased reward prediction error signaling in the right ventral striatum compared to controls ([12/14/−10], t = 3.43, PSVC for striatal PE = .013; figure 1D).

Association Between Dopamine Synthesis and Reward Prediction Error Signal

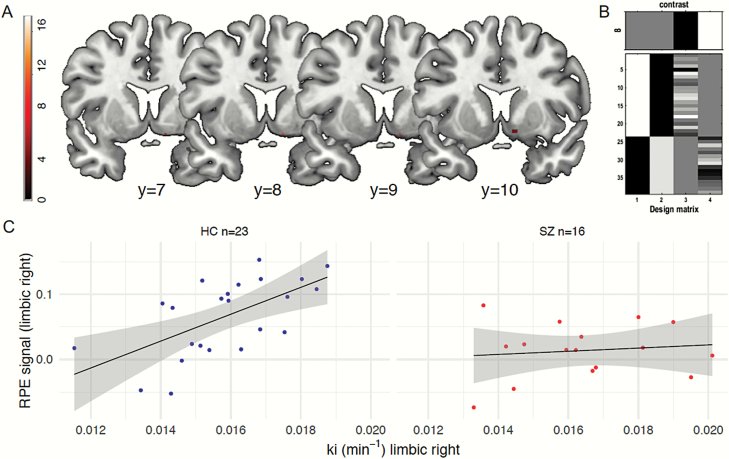

We tested for group differences in the association between striatal dopamine synthesis and the fMRI reward prediction error signal. For that, we carried out voxel-wise SPM analyses introducing limbic Kicer values as covariate and probing a group by covariate interaction (figure 4B for the design matrix). This revealed that groups differed in their correlation between Kicer values and reward prediction error signaling in the right ventral striatum (significant group by covariate interaction: [12/8/−12], F = 11.2, PSVC for right striatal reward prediction error (RPE) = .022, Bonferroni-corrected, figure 4A). Post hoc 1-sample t-tests within groups showed that there was a positive correlation between striatal reward prediction error signaling and Kicer values in the right ventral striatum in controls ([12/8/−12], t = 4.1, PSVC for right striatal RPE < .001), but no significant association in patients. No significant effect was found for the left limbic Kicer values. In order to test the robustness of this finding, we ran additional independent VOI-analyses predicting reward prediction error that were in line with our voxel-wise findings (supplementary material); limbic Kicer values predicted higher prediction error signaling (r = .608, adjusted R2 = .340, P = .002; based on independent VOI analysis) in controls, but not in patients (r = .12, adjusted R2 = .056, P > .6; figure 4C).

Fig. 4.

Association between dopamine synthesis capacity and reward prediction error. (A) The voxel-wise analysis revealed that groups differed in their correlation between right limbic striatal Kicer values and the reward prediction error signal in the same region ([12/8/−12], F = 11.2, PSVC for right striatal RPE = .022, Bonferroni-corrected). (B) The SPM design matrix using the individual reward prediction error contrast images with limbic Kicer as covariate allowing to test group-wise interaction effects. (C) In controls (left scatterplot), limbic Kicer values correlated with higher reward prediction error signaling (r = .608, adjusted R2 = .340, P = .002; based on independent VOI analysis). There was no significant association between both measures in schizophrenia patients (right scatterplot; r = .12, adjusted R2 = .056, P > 0 .6).

Correlation With Psychopathology

In exploratory analyses, positive symptoms correlated with Kicer values in the left (r = .48, P = .037) and right (r = .52, P = .023) associative striatum (figure 3B). There was no significant association between Kicer values and negative symptoms (P > .2). Striatal prediction error signaling in schizophrenia patients was negatively correlated with negative symptoms ([12/8/−10], t = 3.23, PSVC for striatal RPE = .039). There was no significant correlation between prediction error signaling and positive symptoms.

Discussion

In the current study, we found no difference in striatal dopamine synthesis capacity when comparing unmedicated schizophrenia patients to controls. However, exploratory post hoc analyses revealed that patients without comorbid alcohol abuse showed increased dopamine synthesis capacity in the associative striatum compared to controls as well as to schizophrenia patients with alcohol abuse. In addition, schizophrenia patients performed worse in reversal learning and showed decreased ventral striatal reward prediction error signaling. Probing the relationship between limbic dopamine synthesis capacity and prediction error revealed that higher dopamine synthesis capacity correlated with increased coding of the prediction error signal in controls, but this association was absent in schizophrenia patients.

We did not replicate the meta-analytic finding of heightened striatal dopamine synthesis capacity2,3 in our total sample of unmedicated patients. We had calculated our sample size based on a large effect size,41 which has decreased according to more recent meta-analyses.2,3,5,52 Thus, our study may have been insufficiently powered to detect a group difference in Kicer. Further, there were differences in our PET protocol compared to previous studies6,10,53–55 regarding no application of entacapone/carbidopa to block peripheral FDOPA metabolism (which might have decreased signal-to-noise ratio in our study) as well as shorter scanning duration (60 min compared to 95 min). However, a scanning duration of 60 min has been used before and was suggested to be valid56 (for further discussion, please see Avram et al7).

Alternatively, it was noted that patients with schizophrenia display more heterogeneity in PET measures of their dopaminergic system.5 Moderating factors on the dopaminergic system suggested by former studies include substance abuse9 as well as the degree of current psychotic symptoms.6 While none of our patients showed withdrawal signs, dependence or drug-induced psychosis, several patients met the ICD-10 criteria for abuse of alcohol. On the one hand, this reflected the high ecological validity of our sample, since up to 50% of schizophrenia patients have a comorbid diagnosis of alcohol or drug abuse.57,58 On the other hand, this comorbidity supposedly affected our PET findings, since striatal dopamine function was reported to be blunted in substance use patients,50,59,60 as well as in schizophrenia patients with comorbid substance dependency.9 Also, subjects with clinical high risk for schizophrenia who used cannabis showed reduced stress-induced dopaminergic responses in the striatum.61 When differentiating our patient sample according to alcohol abuse, we found that only patients without alcohol abuse showed elevated dopamine synthesis capacity in the associative striatum compared to controls and patients with alcohol abuse. This localization within the striatum is in line with evidence suggesting that dopamine synthesis capacity in schizophrenia patients is elevated mainly in the associative and sensorimotor subdivisions.52 This finding may point towards alcohol abuse as an important moderator of dopamine synthesis capacity in schizophrenia patients. Nevertheless, it remains an exploratory post hoc finding and should thus be treated with caution; replication remains warranted in future studies.

Higher dopamine synthesis capacity was associated with increased positive symptoms in a sample of schizophrenia as well as bipolar patients with current psychosis,6 suggesting dopamine synthesis capacity as a (transdiagnostic) state marker of the psychotic state. In our sample of unmedicated schizophrenia patients with comparatively high levels of current psychotic symptoms, we replicated a positive correlation between positive symptoms and dopamine synthesis capacity in the associative striatal subregion. Though it should be noted that we used the positive scale from the 5-factor solution45 instead of the standard44 PANSS scale as previous reports.6 Thompson et al. found that despite lower dopamine release in schizophrenia patients with comorbid substance dependence, the degree of amphetamine-induced DA release was positively associated with amphetamine-induced increase in positive symptoms.9 Similar to this latter finding, in the present study positive symptoms were related to dopamine synthesis capacity in patients displaying a comparably normal range of presynaptic dopamine function. A recent study reported even decreased dopamine synthesis levels in patients with remitted psychosis.7 Presumably, these findings might indicate a functional hypersensitivity of postsynaptic striatal D2 function in psychosis.62 Therefore, longitudinal studies targeting the dopaminergic system over the time-course of different illness stages are warranted.

In line with previous studies in unmedicated patients26–28 (but see Ermakova et al29) as well as in youth at risk for psychosis,30 patients were impaired in reversal learning on the behavioral level and displayed reduced coding of reward prediction error in the ventral striatum compared to controls. The prediction error signal serves as a crucial teaching signal in order to optimally learn from interacting with a dynamic environment.17–19 Aberrant prediction error signaling has been hypothesized to play an important role in the generation of both psychotic positive and motivational negative symptoms.14,16,63,64 In the reward domain, altered striatal reward signals were mainly associated with negative symptoms.31,65–67 Here, we found that reduced reward PE signaling in the right limbic striatum was associated with higher negative symptoms. This suggests that decreased neural coding of prediction error signals may blunt the incentive value of relevant and rewarding events, thus possibly causing decreased motivational behavior and experiences.16,64,67 Crucially, learning from rewards is a basic mechanism in everyday life and the described relationship between dysfunctional reward learning and motivation might be relevant beyond the scope of the investigated disorder. In line with that, reduced prediction error signaling was also correlated with increased anhedonia in patients suffering from major depression.68 With our acquired psychometrics, we cannot disentangle which negative symptoms, eg, anhedonia or amotivation, were specifically correlated with the reduced prediction error signal and whether they overlap with depressive symptoms. Therefore, future studies in patients with schizophrenia as well as depression should aim to dissociate this via more apt instruments, such as the Brief Negative Symptoms Scale69 and the Calgary Depression Scale.70 Whereas we focused strongly on the striatum, others have found decreased prediction error responses in the midbrain and DLPFC in schizophrenia patients.29 In our exploratory analyses (supplementary material), we did not observe group differences or correlations with striatal Kicer in those regions which might be explained via different task designs; our task only used 2 stimuli whereas more complex cognitive processes (and thereby different brain regions) might be engaged in learning tasks using more stimuli and reinforcement types.

Our results do not support the notion that the reduced ventral striatal reward prediction error signal in schizophrenia patients can be explained by local differences in dopamine synthesis capacity, as we did not observe group differences in limbic Kicer. Instead, we found that only in controls, limbic striatal dopamine synthesis capacity correlated positively with the reward prediction error signal in the same area. In controls, higher striatal dopamine synthesis was associated with better cognitive functions such as working-memory37,71 and goal-directed decision making.39 Such positive associations have also been reported for other markers of the dopamine system such as D2/3 availability,72 although a non-monotonic relationship depending on latent profiles characterized by, eg, education level and resting-state connectivity has been suggested, so that functional implications of dopamine levels may differ.72 Regarding associations between dopamine measures and functional MRI activation, both positive and negative associations have been reported: ventral striatal BOLD activation during reward processing was positively associated with striatal dopamine release,73,74 whereas striatal reward prediction error BOLD signal was inversely related to dopamine synthesis capacity.39,75 The latter findings are in contrast to those of the present study. These discrepancies might be due to the specific task solving strategies employed by participants in the respective tasks and studies. In a more complex sequential decision making task, limbic Kicer was positively associated with the degree to use a goal-directed, so-called model-based, strategy based on forward planning and accompanied by stronger coding of model-based PE related to that strategy and reduced coding of model-free striatal prediction errors.39 In the current study, participants used a basic strategy as reflected by the model comparison, which revealed that the single-update reinforcement learning model best explained the behavior in our sample.

In schizophrenia patients, we did not observe a significant association between dopamine synthesis capacity and reward prediction error in the limbic striatum, resulting in a significant group by covariate interaction. This indicates a dysregulation in the limbic ventral striatum in patients that is reflected in a prediction error signal decrease only. While the relationship between BOLD reward prediction error and dopamine remains a matter of debate (eg, Brocka et al76), some evidence links the striatal BOLD signal to stimulus-related dopamine release in the ventral tegmental area.77,78 Our results suggest that reduced reward prediction error in schizophrenia patients is not due to hyperdopaminergic state as characterized by increased dopamine synthesis capacity in the limbic striatum. Nonetheless, reduced prediction error signaling may be due to dysregulated, task-independent dopamine release, resulting in a decreased signal-to-noise ratio but not reflected in increased synthesis.2 Another explanation may be that the observed reduced coding of BOLD prediction error signal is due to non-dopaminergic mechanisms, such as increased cortical inhibition of striatal signaling.77

Limitations

Several limitations of our study have to be stated. First, our sample size was small, which decreased our power to detect group differences and correlations, with the correlations between psychopathology and neural measures not withholding correction for multiple comparisons. Information on (parental) education was not collected so that we cannot rule out that potential differences in education might have affected the observed group effects. However, the sample is rather large for a multi-modal approach in a highly symptomatic patient sample. Notably, all patients were unmedicated, which allowed us to investigate dopamine synthesis capacity without antipsychotic drug confounds.79 Secondly, we had heterogeneity regarding previous medication and illness duration, which might additionally affect dopamine synthesis capacity and could not be fully controlled in this study design. In the same regard, elevated dopamine synthesis capacity was suggested to be only apparent in patients who later responded to antipsychotic medication, while non-responders showed no significant elevation.8 In our sample, we had no information about treatment response due to the cross-sectional design. Therefore, we cannot rule out that our sample included non-responders to anti-dopaminergic treatment, potentially due to non-dopaminergic psychosis.11 Here, we utilized FDOPA-PET to study the presynaptic dopamine function. It should be noted that the relationships between different markers of the dopaminergic system remain understudied and may relate to different mechanisms, including dopamine synthesis and release.80,81 Lastly, prediction error coding appears in the context of predictive value representation. Due to our task-design, we could not address the latter though it reflects an important aspect in schizophrenia research.82,83

Conclusion

Taken together, we found that only in controls, limbic striatal dopamine synthesis capacity positively correlated with striatal prediction error signaling. Unmedicated and highly symptomatic patients only differed from controls in dopamine synthesis capacity when considering alcohol abuse as a moderating factor. In schizophrenia patients, reduced ventral striatal reward prediction error coding was related to negative symptoms and could not be explained by a limbic presynaptic hyperdopaminergic state. This association underlines the importance of this basic learning signal for motivational negative symptoms, while a hyperdopaminergic state in the associative striatum related to positive symptoms. Future longitudinal studies should investigate the effect of antipsychotics on the relationship between striatal dopamine synthesis capacity and prediction error signaling in schizophrenia patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of the participants who took part in this study. We thank Yu Fukuda, Rebecca Boehme, Tobias Gleich, Anne Pankow and Lorenz Deserno for assistance during data collection. The authors report no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft awarded to F.S. (Grant no. SCHL 1969/1-1/1-2/3-1/4-1) and R.B. (BU 1441/4-1/4-2). J.K. is supported by the Charité Clinician-Scientist Program of the Berlin Institute of Health. A.H. received funding from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (01GQ0411, 01QG87164, NGFN Plus 01 GS 08152, 01 GS 08159).

References

- 1. Carlsson A. Does dopamine play a role in schizophrenia? Psychol Med. 1977;7(4):583–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Howes OD, Kambeitz J, Kim E, et al. The nature of dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia and what this means for treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(8):776–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fusar-Poli P, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Striatal presynaptic dopamine in schizophrenia, part II: meta-analysis of [(18)F/(11)C]-DOPA PET studies. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(1):33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McCutcheon R, Beck K, Jauhar S, Howes OD. Defining the locus of dopaminergic dysfunction in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis and test of the mesolimbic hypothesis. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1301–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brugger SP, Angelescu I, Abi-Dargham A, Mizrahi R, Shahrezaei V, Howes OD. Heterogeneity of striatal dopamine function in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of variance. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;87(3):215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jauhar S, Nour MM, Veronese M, et al. A test of the transdiagnostic dopamine hypothesis of psychosis using positron emission tomographic imaging in bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(12):1206–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Avram M, Brandl F, Cabello J, et al. Reduced striatal dopamine synthesis capacity in patients with schizophrenia during remission of positive symptoms. Brain. 2019;142(6):1813–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jauhar S, Veronese M, Nour MM, et al. The effects of antipsychotic treatment on presynaptic dopamine synthesis capacity in first-episode psychosis: a positron emission tomography study. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85(1):79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thompson JL, Urban N, Slifstein M, et al. Striatal dopamine release in schizophrenia comorbid with substance dependence. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(8):909–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jauhar S, Veronese M, Nour MM, et al. Determinants of treatment response in first-episode psychosis: an (18)F-DOPA PET study. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(10):1502–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Demjaha A, Egerton A, Murray RM, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in schizophrenia associated with elevated glutamate levels but normal dopamine function. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75(5):e11–e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim S, Jung WH, Howes OD, et al. Frontostriatal functional connectivity and striatal dopamine synthesis capacity in schizophrenia in terms of antipsychotic responsiveness: an [(18)F]DOPA PET and fMRI study. Psychol Med. 2019;49(15):2533–2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gray JA. Integrating schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(2):249–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heinz A. Dopaminergic dysfunction in alcoholism and schizophrenia–psychopathological and behavioral correlates. Eur Psychiatry. 2002;17(1):9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kapur S. Psychosis as a state of aberrant salience: a framework linking biology, phenomenology, and pharmacology in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maia TV, Frank MJ. An integrative perspective on the role of dopamine in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81(1):52–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bush RR, Mosteller F. A mathematical model for simple learning. Psychol Rev. 1951;58(5):313–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rescorla RA, Wagner AR. A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcement. Classical Conditioning II: Current Research and Theory 1972;(2):64–99. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sutton RS, Barto AG. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. Vol. 1 Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schultz W. Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80(1):1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Steinberg EE, Keiflin R, Boivin JR, Witten IB, Deisseroth K, Janak PH. A causal link between prediction errors, dopamine neurons and learning. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(7):966–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pessiglione M, Seymour B, Flandin G, Dolan RJ, Frith CD. Dopamine-dependent prediction errors underpin reward-seeking behaviour in humans. Nature. 2006;442(7106):1042–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bernacer J, Corlett PR, Ramachandra P, et al. Methamphetamine-induced disruption of frontostriatal reward learning signals: relation to psychotic symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(11):1326–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Diederen KM, Ziauddeen H, Vestergaard MD, Spencer T, Schultz W, Fletcher PC. Dopamine modulates adaptive prediction error coding in the human midbrain and striatum. J Neurosci. 2017;37(7):1708–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miller R. Major psychosis and dopamine: controversial features and some suggestions. Psychol Med. 1984;14(4):779–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schlagenhauf F, Huys QJ, Deserno L, et al. Striatal dysfunction during reversal learning in unmedicated schizophrenia patients. Neuroimage. 2014;89:171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reinen JM, Van Snellenberg JX, Horga G, Abi-Dargham A, Daw ND, Shohamy D. Motivational context modulates prediction error response in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(6):1467–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murray GK, Corlett PR, Clark L, et al. Substantia nigra/ventral tegmental reward prediction error disruption in psychosis. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13(3):239, 267–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ermakova AO, Knolle F, Justicia A, et al. Abnormal reward prediction-error signalling in antipsychotic naive individuals with first-episode psychosis or clinical risk for psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(8):1691–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Millman ZB, Gallagher K, Demro C, et al. Evidence of reward system dysfunction in youth at clinical high-risk for psychosis from two event-related fMRI paradigms. Schizophr Res. April 15, 2019; doi:10.1016/j.schres.2019.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Culbreth AJ, Westbrook A, Xu Z, Barch DM, Waltz JA. Intact ventral striatal prediction error signaling in medicated schizophrenia patients. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2016;1(5):474–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Waltz JA, Xu Z, Brown EC, Ruiz RR, Frank MJ, Gold JM. Motivational deficits in schizophrenia are associated with reduced differentiation between gain and loss-avoidance feedback in the striatum. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2018;3(3):239–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hernaus D, Xu Z, Brown EC, et al. Motivational deficits in schizophrenia relate to abnormalities in cortical learning rate signals. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2018;18(6):1338–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dowd EC, Frank MJ, Collins A, Gold JM, Barch DM. Probabilistic reinforcement learning in patients with schizophrenia: relationships to anhedonia and avolition. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2016;1(5):460–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vanes LD, Mouchlianitis E, Collier T, Averbeck BB, Shergill SS. Differential neural reward mechanisms in treatment-responsive and treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2018;48(14):2418–2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morris RW, Vercammen A, Lenroot R, et al. Disambiguating ventral striatum fMRI-related BOLD signal during reward prediction in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(3):235, 280–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cools R, Gibbs SE, Miyakawa A, Jagust W, D’Esposito M. Working memory capacity predicts dopamine synthesis capacity in the human striatum. J Neurosci. 2008;28(5):1208–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Williams GV, Goldman-Rakic PS. Modulation of memory fields by dopamine D1 receptors in prefrontal cortex. Nature. 1995;376(6541):572–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Deserno L, Huys QJ, Boehme R, et al. Ventral striatal dopamine reflects behavioral and neural signatures of model-based control during sequential decision making. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(5):1595–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cools R, D’Esposito M. Inverted-U-shaped dopamine actions on human working memory and cognitive control. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(12):e113–e125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Howes OD, Kapur S. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: version III–the final common pathway. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(3):549–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schmidt K-H, Metzler P. Wortschatztest: WST. Weinheim: Beltz; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 43. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV® Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), Clinician Version, Administration Booklet. American Psychiatric Pub; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wallwork RS, Fortgang R, Hashimoto R, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D. Searching for a consensus five-factor model of the positive and negative syndrome scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1–3):246–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Patlak CS, Blasberg RG. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. Generalizations. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1985;5(4):584–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hoshi H, Kuwabara H, Léger G, Cumming P, Guttman M, Gjedde A. 6-[18F]fluoro-L-dopa metabolism in living human brain: a comparison of six analytical methods. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1993;13(1):57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Unified segmentation. Neuroimage. 2005;26(3):839–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Martinez D, Slifstein M, Broft A, et al. Imaging human mesolimbic dopamine transmission with positron emission tomography. Part II: amphetamine-induced dopamine release in the functional subdivisions of the striatum. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23(3):285–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nutt DJ, Lingford-Hughes A, Erritzoe D, Stokes PR. The dopamine theory of addiction: 40 years of highs and lows. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(5):305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Boehme R, Deserno L, Gleich T, et al. Aberrant salience is related to reduced reinforcement learning signals and elevated dopamine synthesis capacity in healthy adults. J Neurosci. 2015;35(28):10103–10111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McCutcheon R, Beck K, Jauhar S, Howes OD. Defining the locus of dopaminergic dysfunction in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis and test of the mesolimbic hypothesis. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1301–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jauhar S, Veronese M, Rogdaki M, et al. Regulation of dopaminergic function: an [18F]-DOPA PET apomorphine challenge study in humans. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(2):e1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jauhar S, McCutcheon R, Borgan F, et al. The relationship between cortical glutamate and striatal dopamine in first-episode psychosis: a cross-sectional multimodal PET and magnetic resonance spectroscopy imaging study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(10):816–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Howes OD, Montgomery AJ, Asselin MC, et al. Elevated striatal dopamine function linked to prodromal signs of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(1):13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cumming P, Gjedde A. Compartmental analysis of dopa decarboxylation in living brain from dynamic positron emission tomograms. Synapse. 1998;29(1):37–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Barnett JH, Werners U, Secher SM, et al. Substance use in a population-based clinic sample of people with first-episode psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Miles H, Johnson S, Amponsah-Afuwape S, Finch E, Leese M, Thornicroft G. Characteristics of subgroups of individuals with psychotic illness and a comorbid substance use disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(4):554–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Martinez D, Gil R, Slifstein M, et al. Alcohol dependence is associated with blunted dopamine transmission in the ventral striatum. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(10):779–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kamp F, Proebstl L, Penzel N, et al. Effects of sedative drug use on the dopamine system: a systematic review and meta-analysis of in vivo neuroimaging studies. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(4):660–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mizrahi R, Kenk M, Suridjan I, et al. Stress-induced dopamine response in subjects at clinical high risk for schizophrenia with and without concurrent cannabis use. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(6):1479–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Weinstein JJ, Chohan MO, Slifstein M, Kegeles LS, Moore H, Abi-Dargham A. Pathway-specific dopamine abnormalities in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81(1):31–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Heinz A, Schlagenhauf F. Dopaminergic dysfunction in schizophrenia: salience attribution revisited. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(3):472–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Corlett PR, Honey GD, Fletcher PC. Prediction error, ketamine and psychosis: an updated model. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(11):1145–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Radua J, Schmidt A, Borgwardt S, et al. Ventral striatal activation during reward processing in psychosis: a neurofunctional meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1243–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Juckel G, Schlagenhauf F, Koslowski M, et al. Dysfunction of ventral striatal reward prediction in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2006;29(2):409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Waltz JA, Schweitzer JB, Ross TJ, et al. Abnormal responses to monetary outcomes in cortex, but not in the basal ganglia, in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(12):2427–2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Rothkirch M, Tonn J, Köhler S, Sterzer P. Neural mechanisms of reinforcement learning in unmedicated patients with major depressive disorder. Brain. 2017;140(4):1147–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kirkpatrick B, Strauss GP, Nguyen L, et al. The brief negative symptom scale: psychometric properties. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(2):300–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E. Assessing depression in schizophrenia: the calgary depression scale. Br J Psychiatry 1993;163(S22):39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Landau SM, Lal R, O’Neil JP, Baker S, Jagust WJ. Striatal dopamine and working memory. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(2):445–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lövdén M, Karalija N, Andersson M, et al. Latent-profile analysis reveals behavioral and brain correlates of dopamine-cognition associations. Cereb Cortex. 2018;28(11):3894–3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Urban NB, Slifstein M, Meda S, et al. Imaging human reward processing with positron emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2012;221(1):67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Schott BH, Minuzzi L, Krebs RM, et al. Mesolimbic functional magnetic resonance imaging activations during reward anticipation correlate with reward-related ventral striatal dopamine release. J Neurosci. 2008;28(52):14311–14319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Schlagenhauf F, Rapp MA, Huys QJ, et al. Ventral striatal prediction error signaling is associated with dopamine synthesis capacity and fluid intelligence. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;34(6):1490–1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Brocka M, Helbing C, Vincenz D, et al. Contributions of dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic neurons to VTA-stimulation induced neurovascular responses in brain reward circuits. Neuroimage. 2018;177:88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ferenczi EA, Zalocusky KA, Liston C, et al. Prefrontal cortical regulation of brainwide circuit dynamics and reward-related behavior. Science. 2016;351(6268):aac9698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lohani S, Poplawsky AJ, Kim SG, Moghaddam B. Unexpected global impact of VTA dopamine neuron activation as measured by opto-fMRI. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(4):585–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Gründer G, Vernaleken I, Müller MJ, et al. Subchronic haloperidol downregulates dopamine synthesis capacity in the brain of schizophrenic patients in vivo. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(4):787–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Berry AS, Shah VD, Furman DJ, et al. Dopamine synthesis capacity is associated with D2/3 receptor binding but not dopamine release. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(6):1201–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Heinz A, Siessmeier T, Wrase J, et al. Correlation of alcohol craving with striatal dopamine synthesis capacity and D2/3 receptor availability: a combined [18F]DOPA and [18F]DMFP PET study in detoxified alcoholic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(8):1515–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Gold JM, Waltz JA, Matveeva TM, et al. Negative symptoms and the failure to represent the expected reward value of actions: behavioral and computational modeling evidence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(2):129–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Waltz JA, Gold JM. Motivational deficits in schizophrenia and the representation of expected value. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2016;27:375–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.