Abstract

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a life-threatening disease that often involves vascular remodeling. Although pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) are the primary participants in vascular remodeling, their biological role is not entirely clear. The present study analyzed the role of enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) in vascular remodeling of PH by investigating the behavior of PASMCs. The expression levels of EZH2 in PASMCs in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH), a type of PH, were detected. The role of EZH2 in PASMC migration was investigated by wound-healing assay following overexpression and knockdown. Functional enrichment analysis of the whole-genome expression profiles of PASMCs with EZH2 overexpression was performed using an mRNA Human Gene Expression Microarray. Quantitative (q)PCR was performed to confirm the results of the microarray. EZH2 expression levels increased in CTEPH cell models. The overexpression of EZH2 enhanced PASMC migration compared with control conditions. Functional enrichment analysis of the differentially expressed genes following EZH2 overexpression indicated a strong link between EZH2 and the immune inflammatory response and oxidoreductase activity in PASMCs. mRNA expression levels of superoxide dismutase 3 were verified by qPCR. The results suggested that EZH2 was involved in the migration of PASMCs in PH, and may serve as a potential target for the treatment of PH.

Keywords: enhancer of zeste homolog 2, hypoxic pulmonary arterial hypertension, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells, migration, functional enrichment analysis

Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a progressive and life-threatening disease characterized by increased pulmonary artery pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance. PH can be divided into five clinical types according to different etiologies (1). However, different categories of PH share a common pathogenesis of vascular remodeling involving thickening of pulmonary vasculature and invasive proliferation of smooth muscle cells (2). Pulmonary smooth muscle cell (PASMC) proliferation and migration to the intima of pulmonary arteries serve a critical role in the process of pulmonary vascular remodeling in PH (3).

The underlying mechanism and genes associated with PASMC migration in PH have not been fully elucidated. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), a histone methyltransferase highly expressed in multiple types of cancer, such as thyroid and prostate cancer (4,5), promotes tumor cell proliferation and migration via epigenetic regulation of cancer-associated gene expression levels (6). EZH2 expression levels are also associated with tumor invasiveness (7). Considering that epigenetic alterations have been reported in certain types of PH that can be regarded as a cancer-like disease, EZH2 may be involved in the pulmonary arterial remodeling process in PH (8–10). EZH2 has been demonstrated to be associated with hypoxia-induced PH in mice and participates in the proliferation and migration of PASMCs (11). To the best of our knowledge, however, there is little evidence to demonstrate how EZH2 functions in the pathogenesis of PASMC migration in PH.

Hypoxic pulmonary arterial hypertension (HPAH), a common type of PH, is caused by high altitude or persistent hypoxic conditions induced by pulmonary disease, particularly chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (1). Previous studies on HPAH demonstrated that structural remodeling in pulmonary arteries contributes to its development and occur over a relatively short time period (12,13). Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is another important form of PH characterized by one or multiple episodes of pulmonary embolism. Remodeling of distal pulmonary vessels following initial pulmonary thromboembolism may be responsible for the formation of CTEPH (14). The present study analyzed hypoxia-induced PASMCs and those isolated from the endarterectomized tissue of patients with CTEPH. In order to determine the role of EZH2 in PH, the effect of EZH2 on PASMC migration was investigated using human CTEPH cell models. Pathways that contribute to this process following EZH2 overexpression were also identified.

The present results revealed high expression levels of EZH2 in hypoxia-induced and CTEPH PASMCs. Furthermore, EZH2 affected PASMC migration. The present study also reported genome-wide characteristics of EZH2 overexpression. These results may provide insight into the mechanism associated with PH artery remodeling.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval

The present study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital of Capital Medical University. Written informed consent was provided by all patients before the procedure was initiated.

Cell preparation

Normal human PASMC line (N-PASMC; cat. no. 3110) was purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratories, Inc. and used for EZH2 transfection. Cells were cultured in smooth muscle cell growth medium (SMCM) (ScienCell Research Laboratories, Inc.), including smooth muscle basal medium, FBS (2%), smooth muscle cell growth supplement (1%), penicillin (200 µg/ml) and streptomycin (200 IU/ml). All cells were incubated in a 95% humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 21% O2 and passaged after reaching 80–90% confluence.

A total of three consecutive patients with CTEPH diagnosed by pulmonary angiography and right heart catheterization at Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital (Beijing, China) between January 2013 and December 2014 were enrolled in the study. The patients included two male patients and one female patient, aged between 49 and 61 years. All patients diagnosed with CTEPH met the following criteria after 3 months of effective anticoagulation treatment: Mean pulmonary arterial pressure ≥25 mmHg with normal wedge pressure ≤15 mmHg and at least one pulmonary segmental perfusion defect revealed by lung perfusion scanning or pulmonary artery occlusion detected by multi-detector computed tomography angiography or pulmonary angiography. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification was used to classify patients (15). Exclusion criteria included ventriculo-atrial shunt, malignancies, and other lung diseases. Clinical data were recorded.

PASMCs from patients with CTEPH were isolated and cultured as previously described (16,17). Briefly, pulmonary endarterectomy resection tissues from patients were cut into 1 mm3 pieces and then centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at room temperature. Following resuspension in SMCM, the resultant suspension was seeded in dishes and incubated in a 95% humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 1 week until PASMCs were observed from adherent tissue pieces. The PASMC phenotypes of isolated cells were characterized by immunofluorescence using monoclonal antibodies against human α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; 1:200; cat. no. ab124964; Abcam) and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (1:100; cat. no. sc-6956; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) respectively, for 1 h at room temperature. All cells were passaged after reaching 80–90% confluence prior to measurement of EZH2 expression levels.

Transient transfection of PASMCs

For EZH2 overexpression, the EZH2 gene was subcloned into the pEZ-M98 vector (GeneCopoeia, Inc.) to generate pM-EZH2. Cultured N-PASMCs were then transfected with pM-EZH2 vector using the Neon Transfection System (MPK5000) from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the supplier's instructions. Briefly, cells were cultured in 60-mm dishes to 70% confluency and then transfected with 2 µg plasmid DNA (1,375 V; 20 ms) at room temperature. Empty vector pEZ-M98 (pM) was used as a transfection control.

For EZH2 knockdown, PASMCs from CTEPH patient 3 were cultured in 60-mm dishes and transfected with 160 pmol small interfering (si)RNA (Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd.) and treated with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at room temperature, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sequences were sense, 5′-CCUGACCUCUGUCUUACUUTT-3′ and antisense, 5′-AAGUAAGACAGAGGUCAGGTT-3′. RNAi negative control that had no homology with mammalian genes was used as the transfection control. The RNAi negative control sequences were sense, 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′ and antisense, 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′. After 48 h, transfection efficiency was determined by both PCR and western blot analysis for EZH2.

Wound healing assay

At 12 h after transfection, the transfection mixture was replaced with 0.2% FBS, and a straight scratch was created using a 200-µl pipette tip on a monolayer of confluent PASMCs. Images were captured at 0 and 12 h after scratching to visualize migrated cells and wound healing using phase microscopy (magnification, ×40). The distance of cell movement from the wound edge into the wound area indicated the extent of cell migration. A total of 10 points, evenly spaced, were selected on each edge, and the minimum distance to the scratch edge was measured. The cell migration rate was calculated with the following formula: [Scratch width (0 h)-scratch width (12 h)]/scratch width (0 h) ×100%. The experiment was repeated three times, and the average value was calculated.

Gene microarray analysis

In order to evaluate the effect of EZH2 on PASMCs, total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) following EZH2 overexpression. mRNA expression levels were profiled using mRNA + lncRNA Human Gene Expression Microarray V4.0 (CapitalBio Corporation) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For microarray analysis, Agilent Feature Extraction (V10.7; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) was used for data extraction and quantification. Then, raw data were summarized and normalized at the transcript level using the GeneSpring GX program (V12.0; Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The unpaired t-test was applied to filter genes with differential expression in the control vs. experimental groups. Fold-change in differentially expressed mRNAs >2.0 and P<0.05 were considered to indicate a statistically significant difference between experimental and control groups. Certain differentially expressed genes were then validated by reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q)PCR.

Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway functional enrichment analysis

Following microarray screening for mRNAs from PASMCs transfected with pM-EZH2 and controls, the differentially expressed genes were grouped into functional categories by performing GO enrichment analysis according to the GO database (geneontology.org/), which categorizes genes into regulatory networks on the basis of ‘Biological Process’, ‘Molecular Function’ and ‘Cellular Function’. The P-value of the significance level for each gene with differential expression was estimated with Fisher's exact test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (18), BioCarta (19) and Reactome databases (20) with KOBAS software (version 3.0) (21). Significant enrichments were calculated and filtered by P<0.05.

RT-qPCR

Relative expression levels of EZH2, superoxide dismutase 3 (SOD3) and NADPH oxidase 1 (NOX1) were determined by RT-qPCR analysis. Total RNA was isolated from PASMCs with EZH2 transfection using TRIzol® (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RT was conducted using a ReverTra Ace qPCR kit (Toyobo Life Science). Briefly, 0.5 µg total RNA was first reverse transcribed using reverse transcriptase Mix at the following conditions: 37°C for 15 min and 98°C for 5 min; 4°C. qPCR quantification was performed as previously described (15). All experiments were performed in triplicate. The primer sequences were: EZH2 forward, 5′-AATCATGGGCCAGACTGGGAAGAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCTTGAGCTGTCTCAGTCGCATGT-3′; SOD3 forward, 5′-GGCCTCCATTTGTACCGAAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-AGGGTCTGGGTGGAAAGGT-3′; NOX1 forward, 5′-CCCCAAGTCTGTAGTGGGAGTT-3′ and reverse, 5′-CGCAGGCTCTTTGCCAAA-3′; and GAPDH forward, 5′-TGACTTCAACAGCGACACCCA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAA-3′. Human GAPDH was used as an endogenous control to normalize gene expression levels.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 13.0; SPSS, Inc.) Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired Student's t-test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

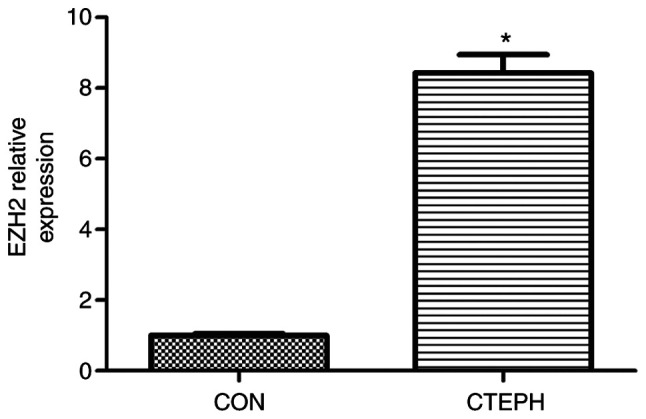

Increased EZH2 expression levels in PASMCs derived from patients with CTEPH

In order to analyze EZH2 expression levels, PASMCs were isolated from tissue obtained during endarterectomy from 3 patients with CTEPH. The clinical information for patients is summarized in Table SI. The mRNA expression levels of EZH2 were assessed in PASMCs from CTEPH patients. EZH2 mRNA expression levels were significantly increased in PASMCs from CTEPH patients, compared with control PASMCs (Fig. S1). PASMCs from CTEPH patient 3 exhibited the strongest EZH2 expression levels among the patients (Fig. 1 and Table SII).

Figure 1.

Relative expression levels of EZH2. The relative expression levels of EZH2 in normal control PASMCs and PASMCs from CTEPH patient 3 were assayed by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. *P<0.05 vs. CON. EZH2, enhancer of zeste homolog 2; PASMC, pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell; CTEPH, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; CON, control.

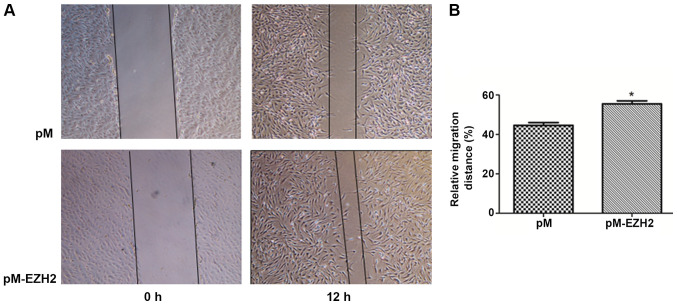

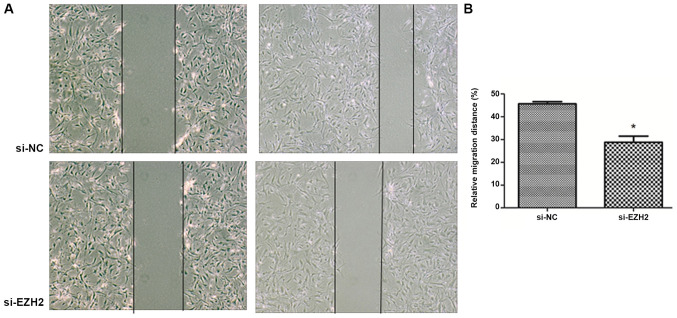

EZH2 affects PASMC migration

EZH2 expression levels were determined by western blot analysis following overexpression by pM-EZH2 vector and knockdown by siRNA (Fig. S2). The role of the EZH2 gene in affecting PASMC migration was then investigated by performing a wound healing assay. Following 12-h wounding, the gap scratched by a pipette tip was filled with more cells in the EZH2-overexpression group compared with the control. However, the distance of the scratch between the migration edges of the cells was significantly wider in the EZH2 interference group, compared with the control. The migration distance of N-PASMCs following EZH2 transfection was increased compared with that observed for the control. Silencing of EZH2 by siRNA significantly inhibited the migration of PASMCs derived from patients with CTEPH (Figs. 2 and 3). This indicated that EZH2 increased the migration of PASMCs and participated in the pathogenesis of PAH.

Figure 2.

EZH2 overexpression increases PASMC migration during wound healing. N-PASMCs were transfected with plasmid pEZ-M98-EZH2 (pM-EZH2) or pEZ-M98 (pM) plasmid only (control). A scratch was created using a 200-µl pipette tip on a confluent monolayer of cells. Cell migration distance was assayed as the distance from wound edges to the wound area. (A) Images obtained at 0 and 12 h in the pM-EZH2 and control groups. (B) Rate of cell migration in each group. *P<0.05 vs. pM. EZH2, enhancer of zeste homolog 2; PASMC, pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell; N, normal.

Figure 3.

EZH2 interference inhibits CTEPH PASMC migration during wound healing. PASMCs from CTEPH Patient 3 were transfected with siRNA (si-EZH2). Scrambled siRNA was used as the RNA interference NC (si-NC). A scratch was created using a 200-µl pipette tip on a confluent monolayer of cells. Cell migration distance was measured as the distance from wound edges to the wound area. (A) Images obtained at 0 and 12 h after wounding in the si-EZH2 and control groups. (B) Cell migration rate in each group. *P<0.05 vs. si-NC. EZH2, enhancer of zeste homolog 2; CTEPH, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; PAMSC, pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell; si, small interfering; NC, negative control.

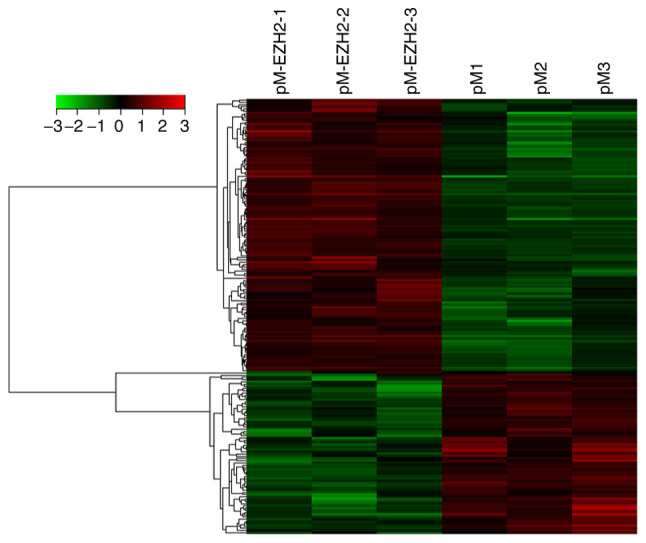

EZH2-associated differences in gene expression levels

N-PASMCs transfected with EZH2 and control were collected and microarray analysis was used to investigate changes in gene expression levels. A data set from the microarray was subjected to supervised hierarchical clustering analysis. Samples were divided into two groups based on differential expression levels of genes (Fig. 4). A total of 192 genes with statistically significant changes were detected. Among these, 122 genes were upregulated and 70 were downregulated following EZH2 transfection. The top 10 significantly up- or downregulated genes, including oncostatin M (OSM), Nod-like receptor (NLR)P12, IL-31, serum amyloid A2 (SAA2) and arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase activating protein (ALOX5AP), according to P-value are summarized in Table I.

Figure 4.

Supervised hierarchical cluster analysis of significantly differentially regulated genes from EZH2 overexpression and control pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Rows represent the differentially expressed genes; columns represent the samples. Gene expression levels are depicted according to the color scale. Color change from green to red indicates a change from down- to upregulation. EZH2, enhancer of zeste homolog 2.

Table I.

Top 10 significantly altered genes.

| A, Upregulated genes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gene symbol | P-value | Fold-change |

| OSM | 0.001 | 6.015 |

| FSHR | 0.009 | 4.793 |

| NLRP12 | 0.008 | 4.294 |

| LOC100996286 | <0.001 | 4.010 |

| LOC100131907 | <0.001 | 3.969 |

| CFAP61 | 0.001 | 3.876 |

| IL31 | 0.016 | 2.953 |

| SLC40A1 | 0.042 | 2.819 |

| CRX | 0.013 | 2.809 |

| lnc-DFNA5-3 | 0.006 | 2.675 |

| B, Downregulated genes | ||

| Gene symbol | P-value | Fold-change |

| SAA2 | 0.013 | 4.615 |

| C3orf67 | 0.015 | 4.593 |

| ABCC6 | 0.013 | 3.744 |

| SLC38A4 | 0.040 | 3.404 |

| TTN | 0.009 | 3.349 |

| ALOX5AP | 0.047 | 3.161 |

| LOC101929689 | 0.001 | 3.132 |

| C1orf229 | 0.011 | 3.132 |

| AP1S2 | 0.001 | 3.025 |

| lnc-CBWD5-1 | 0.010 | 3.022 |

GO and KEGG functional enrichment analysis reveals different genes are involved in inflammatory and immune processes

GO analysis of Cell Component revealed that differentially expressed genes were primarily enriched in ‘membranous components’ (data not shown). The GO analysis of Molecular Function revealed differentially expressed genes associated with ‘hydrogen ion channel activity’ and ‘oxidoreductase activity’ (data not shown). GO analysis of ‘Biological Process’, as shown in Table II, revealed a strong signature for ‘cellular response to pH’, ‘inflammation and the immune response’ related functions. Of the top 20 significant GO terms, 7 (35%) were concerned with ‘cellular response to pH’ or ‘response to metal ion’; 8 (40%) were involved in ‘regulation of interleukin-6 biosynthetic process’, ‘interleukin-6 biosynthetic process’, ‘negative regulation of interleukin-6 biosynthetic process’, ‘immune system process’ and ‘humoral immune response mediated by circulating immunoglobulin’ (Table II). NLRP12, toll-like receptor 9, complement C1q (C1Q)B and C chain were markedly enriched in these GO terms.

Table II.

Top 20 significant GO terms of differential genes.

| GO term | Genes | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular response to pH | HVCN1, KD1L3, NOX1 | 0.0002 |

| Response to metal ion | TTN, SLC18A2, SOD3, HVCN1, CYP11B1, SLC40A1, ZACN, ALOX5AP | 0.0003 |

| Negative regulation of interleukin-6 biosynthetic process | PRG4, NLRP12 | 0.0008 |

| Regulation of interleukin-18 production | TLR9, NLRP12 | 0.0008 |

| Response to transition metal nanoparticle | HVCN1, ZACN, SLC18A2, SOD3, SLC40A1 | 0.0008 |

| Negative regulation of interleukin-6 production | PRG4, NLRP12, TLR9 | 0.0011 |

| Interleukin-18 production | TLR9, NLRP12 | 0.0011 |

| Response to pH | HVCN1, PKD1L3, NOX1 | 0.0012 |

| Cellular response to acidic pH | PKD1L3, NOX1 | 0.0017 |

| Positive regulation of response to wounding | TLR9, OSM, NLRP12, ANO6, CPB2 | 0.0021 |

| Response to zinc ion | HVCN1, ZACN, SLC18A2 | 0.0025 |

| Humoral immune response mediated by circulating immunoglobulin | C1QC, C1QB, HLA | 0.0032 |

| Response to acidic pH | PKD1L3, NOX1 | 0.0039 |

| Mitotic chromosome condensation | TTN, CDCA5 | 0.0039 |

| Response to inorganic substance | TTN, SLC18A2, SOD3, HVCN1, CYP11B1, SLC40A1, ZACN, ALOX5AP | 0.0039 |

| Immune system process | PSMB11, RAB17, SLC7A10, PRG4, ANO6, PRKCG, CYP11B1, SLC40A1, INPP4B, IGSF6, C1QC, OSM, C1QB, TLR9, CD160, PYDC1, DPP4, HLA, MLF1, GCSAM, CCL3L3, IL31 | |

| Regulation of interleukin-6 biosynthetic process | PRG4, NLRP12 | 0.0051 |

| Cellular response to metal ion | HVCN1, ALOX5AP, CYP11B1, SLC40A1 | 0.0051 |

| Photoreceptor cell differentiation | CEP290, CRX, MYO7A | 0.0053 |

| Interleukin-6 biosynthetic process | PRG4, NLRP12 | 0.0062 |

GO, Gene Ontology.

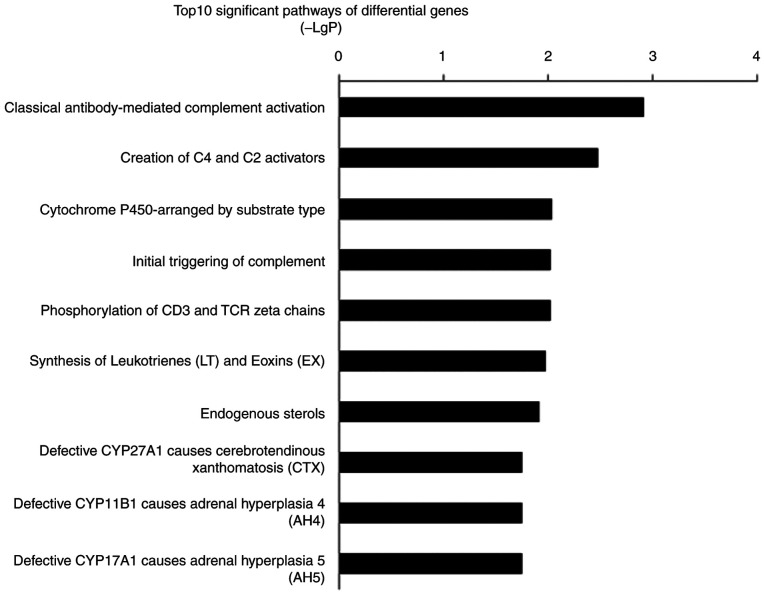

Pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes also implicated inflammation and the immune response-related pathways were involved in PASMCs migration mediated by EZH2. The most significant pathway was ‘classical antibody-mediated complement activation’ (P=0.001). The second most significant pathway, ‘Creation of C4 and C2 activators’, and fourth most significant pathway, ‘Initial triggering of complement’, were also associated with complement-associated pathways (P=0.03 and 0.09, respectively). The top 10 significant pathways included inflammatory and immune response mechanisms such as ‘phosphorylation of CD3 and TCR ζ chains’, ‘synthesis of leukotrienes (LT) and eoxins (EX)’ and the ‘cytochrome P450-arranged by substrate type’ (Fig. 5). The signature genes that regulated inflammatory and immune response processes included C1QC, CYP4F8 and ALOX5AP.

Figure 5.

Top 10 pathways with significant differences in gene expression levels. The criterion for significance was P<0.05. LgP (x-axis) represents the significance level. TCR, T-cell receptor.

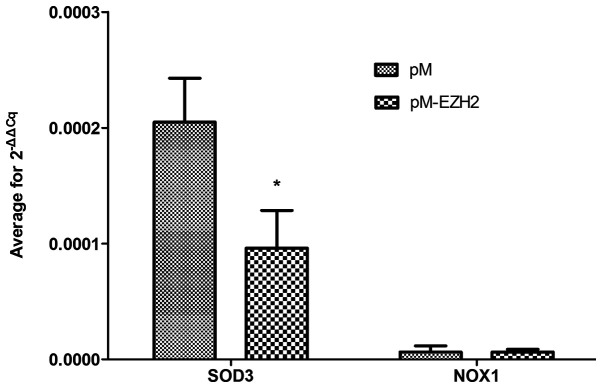

Validation of gene expression levels

SOD3 and NOX1 were selected for validation of mRNA expression levels via qPCR because functional analysis revealed that both genes were significantly enriched following EZH2 transfection. qPCR demonstrated that the mRNA expression level of SOD3 was decreased compared with the control (Fig. 6 and Table SIII), confirming the results of the microarray detection. However, NOX1 expression levels were not significantly altered.

Figure 6.

Validation of array data. Normal pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells were transfected with plasmid pM-EZH2 or pM plasmid only (control). Expression levels of SOD3 and NOX1 (n=3) were assayed by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. *P<0.05 vs. pM. EZH2, enhancer of zeste homolog 2; SOD3, superoxide dismutase 3; NOX1, NADPH oxidase 1.

Discussion

PASMCs are primary mediators of small pulmonary arterial remodeling, which is an important pathological process in the progression of PH. The proliferation and migration of PASMCs serve key roles in this process (22). Epigenetic changes are involved in the development of certain types of PH (10). Furthermore, our laboratory previously revealed that DNA methylation changes in PASMCs are associated with the pathogenesis of CTEPH (10,15). In the present study, upregulation of EZH2 was observed in PASMCs from patients with CTEPH and those induced by hypoxic conditions. Moreover, EZH2 affected the migration ability of N-PASMCs. Gene chips were used to identify the mechanism following EZH2 overexpression in N-PASMCs. Functional enrichment analysis revealed that pathophysiological pathways that participated in inflammatory and immune processes were controlled by EZH2-associated genes. The present study provides further understanding into vascular remodeling mechanisms underlying PH.

EZH2 is a conserved methyltransferase of histone H3K27, which promotes cell proliferation, migration and invasiveness in tumorigenesis via epigenetic modifications (23,24). HPAH and CTEPH are two common types of PH (1). PASMCs in HPAH and CTEPH exhibit proliferation and migration phenotypes similar to those of cancer cells (25,26). In the present study, EZH2 expression levels were increased in both hypoxia-induced and patient-derived PASMCs, which is consistent with a previous study in a hypoxia-induced PAH mouse model (11). However, unlike CTEPH, HPAH is rarely treated with surgery, thus tissue samples from patients with HPAH are difficult to obtain. Hypoxia-induced human PASMCs were therefore used instead of HPAH tissue samples for the measurement of EZH2 mRNA expression levels. The present study did not investigate EZH2 mRNA expression levels in HPAH and only focused on CTEPH because EZH2 mRNA levels could not be measured in cells from HPAH tissue. Increased migration ability of N-PASMCs overexpressing EZH2 and decreased migration ability of patient-derived PASMCs following EZH2 knockdown were confirmed, which was in line with previously reported changes in hypoxia-induced HPASMCs and cancer cells (11,27). Collectively, the present findings indicated that EZH2 may serve a role in the migration of PASMCs in PH vascular remodeling. However, no changes in the proliferation or apoptosis of PASMCs following EZH2 transfection (data not shown) were detected in the present study, which was inconsistent with findings previously reported by Aljubran et al (11). It was speculated that different PASMC phenotypes may partly explain this difference: Previous studies have demonstrated that there may be multiple phenotypically distinct SMC populations in pulmonary arteries, and these distinct populations may serve different functions (28,29).

EZH2-associated changes in gene expression levels and pathophysiological signaling pathways were investigated in the present study. The results identified a number of candidate genes, as well as pathophysiological pathways targeted by oxidoreductase activity, inflammation and immune processes, that provide a basis for further investigation of the mechanism of EZH2 in PH vascular remodeling. The present results revealed that three of the top 10 significantly upregulated genes (OSM, NLRP12 and IL-31) were closely associated with inflammatory and immune responses. As the most differentially upregulated gene, OSM is a secreted member of the IL-6 family and serves an important role in maintaining homeostasis of the internal environment under chronic inflammation (30). NLRP12 belongs to non-classical NLRP molecules and has been reported to regulate inflammation and tumorigenesis (31,32). IL-31 is a cytokine belonging to the IL-6 family and shares a common signaling receptor subunit with OSM (33). IL-6 has been reported to be involved in airway inflammation and remodeling in vascular remodeling (34,35). As is true for a number of proteins in the IL-6 family, the roles of IL-31 and OSM in vascular remodeling remain unclear. The microarray analysis identified SAA2 and ALOX5AP among the 10 most downregulated genes. This result appeared to contradict the proinflammatory roles of SAA2 and ALOX5AP reported in previous studies, which have established that SAA is expressed at increased levels in numerous inflammatory conditions, including trauma, infection and tumor growth, and secreted by the liver as an acute-phase protein (36–38). However, the potential roles of local SAA variants remain to be elucidated. De Buck et al (39) described the extrahepatic production of SAA variants by a number of types of tissues, such as brain and colon tissues, with differential expression levels of SAA1 and SAA2. Jumeau et al (40) also identified SAA1 as an important SAA acute-phase gene induced in human monocytes and derived macrophages in the presence of stimulants. The ALOX5AP gene is required for LT synthesis, which is involved in numerous types of inflammatory response (37). The present microarray analysis revealed downregulated expression levels of ALOX5AP (P=0.047). As demonstrated by Wang et al (41), microarrays may not provide accurate results when used to measure differential gene expression at levels near the threshold for detection. No significant change in the expression levels of ALOX5AP was detected (data not shown). Therefore, results reported in relation to ALOX5AP expression levels require further study.

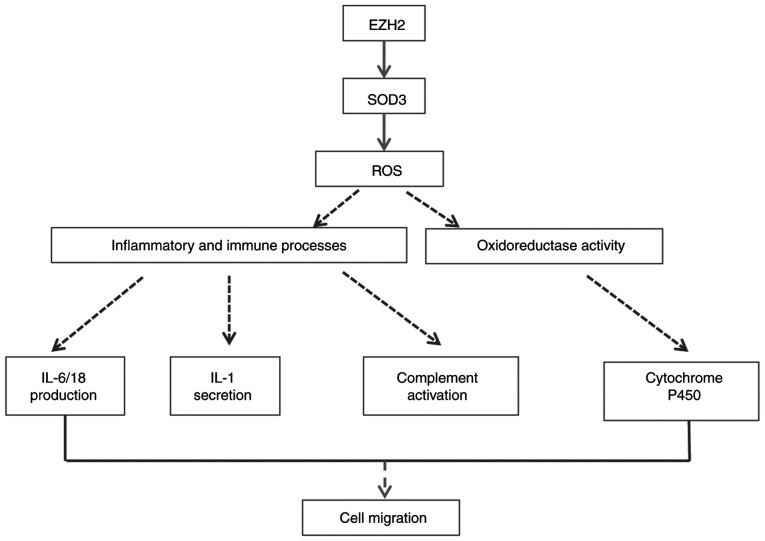

The present results demonstrated significant downregulation of SOD3 levels. In 2010, Archer et al (9) confirmed that deficiency of SOD2 causes PAH by impairing redox signaling and inducing PASMC phenotype transition, which is highly associated with epigenetic regulation by EZH2. Soon et al (42) also demonstrated that BMPR-II deficiency instigates the development of PAH by decreasing SOD3 expression levels and exaggerating the inflammatory response both in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, the role of EZH2 in PASMC migration may be associated with redox and inflammation reactions.

GO term enrichment analysis confirmed the aforementioned observations. GO analysis revealed immune system processes that involve IL-6, −18 and −1 and NF-κB regulation and complement activation predominated. Increasing evidence has confirmed that these inflammatory factors promote vascular remodeling in PH (43–45). Significantly enriched GO terms also included cellular response to hydrogen potential, pH and oxidoreductase activity, which are associated with abnormal energy metabolism in mitochondria, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and an acidic microenvironment. A potential mechanism of cancer-like abnormalities such as a PASMC phenotype shift in PH may be mitochondrial disorder and glycolysis, which is known as the Warburg phenotype in tumors (46–48). In PAH and cancer, abnormal mitochondrial metabolism and redox signaling lead to decreased ROS levels and a shift from oxidative to glycolytic metabolism (49). There is a close association between ROS and the occurrence and development of inflammation (50). Sutendra et al (51) reported that abnormalities of mitochondrial metabolism and decreased ROS levels are linked to the chronic inflammatory process in PAH and progressive expansion of SMC-like cells that obliterate the vascular lumen. SOD has been recognized as a redox-signaling molecule that regulates pulmonary vascular tone and structure and may have therapeutic potential in inflammation (52). Soon et al (42) reported that SOD3 loss is necessary for the proinflammatory phenotype in PAH. The aforementioned studies suggest that there may be an important interplay between ROS and inflammation in SMC. Therefore, we hypothesize that EZH2 may lead to epigenetic repression of SOD3, thus promoting PASMC migration in PAH via inflammatory and immune processes. This chain of events is consistent with the pathogenic mechanism of PAH (53).

Further pathway analysis supported these inflammatory changes, including effects on CD3 and TCR ζ chains and LT synthesis. Pathway analysis also identified a role for complement-associated pathways in the EZH2-mediated migration of PASMCs. A previous study revealed that C3 complement contributes to the development of hypoxia-induced PH in mice (54), and this process is associated with pulmonary vascular remodeling. C3 complement levels are significantly altered in patients with idiopathic PAH (55). In CTEPH, the inflammatory response has also been revealed to play a critical role (56–58).

A total of two genes significantly enriched in GO terms and pathways were selected to verify mRNA expression levels. The decreased expression levels of SOD3 were consistent with the microarray results. Potential mechanism pathways are presented in Fig. 7. The mechanisms of the aforementioned genes and clear functions modulated by EZH2 in PH should be investigated in further studies.

Figure 7.

Potential mechanism for EZH2 modulation. EZH2, enhancer of zeste homolog 2; SOD3, superoxide dismutase 3; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

There are limitations of the present study. First, increased PASMC migration was detected following EZH2 overexpression. Since increased SMC migration is a feature of the synthetic phenotype, the expression levels of synthetic phenotype markers should be assessed to determine the effects of EZH2 overexpression on the PASMC phenotype. Second, these findings indicated that EZH2 is increased in PASMC models of PH and provide a potential preliminary mechanism for the effects of EZH2 on PASMC migration in PH. However, the exact molecular mechanism requires further investigation. For example, T-cell coculture experiments should be performed to validate our finding that EZH2 may regulate inflammatory and immune processes. Third, the present findings are also limited by cell type, since there are distinct SMC populations in pulmonary arteries that may serve different functions. Further validation should be performed using different cells and patient-derived cell lines.

In conclusion, the role of histone methyltransferase EZH2 in PH was investigated. The results indicated that EZH2 promoted human PASMC migration and was increased in CTEPH PASMCs. The enrichment functions affected by EZH2 focused on inflammatory and immune processes. qPCR confirmed significantly altered gene expression levels of SOD3, which suggested an association between EZH2, SOD3, PASMC migration and inflammatory and immune processes in PAH. The present findings may aid the search for therapeutic targets for PH and further investigation on EZH2 in PH is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Capital's Funds for Health Improvement and Research (grant no. CFH 2018-2-2042).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

YW, XXH and DL performed the experiments. YW drafted the manuscript. JFL analyzed the data. YL analyzed and interpreted the data. TJ directed and designed the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital of Capital Medical University. Written informed consent was provided by all patients before the procedure was initiated.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, Celermajer D, Denton C, Ghofrani A, Gomez Sanchez MA, Krishna Kumar R, Landzberg M, Machado RF, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25 Suppl):D34–D41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiong PY, Potus F, Chan W, Archer SL. Models and molecular mechanisms of world health organization group 2 to 4 pulmonary hypertension. Hypertension. 2018;71:34–55. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.08824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi N, Chen SY. Mechanisms simultaneously regulate smooth muscle proliferation and differentiation. J Biomed Res. 2014;28:40–46. doi: 10.7555/JBR.28.20130130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masudo K, Suganuma N, Nakayama H, Oshima T, Rino Y, Iwasaki H, Matsuzu K, Sugino K, Ito K, Kondo T, et al. EZH2 overexpression as a useful prognostic marker for aggressive behaviour in thyroid cancer. In Vivo. 2018;32:25–31. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon JA, Lange CA. Roles of the EZH2 histone methyltransferase in cancer epigenetics. Mutat Res. 2008;647:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang CJ, Hung MC. The role of EZH2 in tumour progression. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:243–247. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao ZY, Cai MY, Yang GF, He LR, Mai SJ, Hua WF, Liao YJ, Deng HX, Chen YC, Guan XY, et al. EZH2 supports ovarian carcinoma cell invasion and/or metastasis via regulation of TGF-beta1 and is a predictor of outcome in ovarian carcinoma patients. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1576–1583. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nephew KP, Huang TH. Epigenetic gene silencing in cancer initiation and progression. Cancer Lett. 2003;190:125–133. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(02)00511-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Archer SL, Marsboom G, Kim GH, Zhang HJ, Toth PT, Svensson EC, Dyck JR, Gomberg-Maitland M, Thébaud B, Husain AN, et al. Epigenetic attenuation of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase 2 in pulmonary arterial hypertension: A basis for excessive cell proliferation and a new therapeutic target. Circulation. 2010;121:2661–2671. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.916098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Philibert RA, Sears RA, Powers LS, Nash E, Bair T, Gerke AK, Hassan I, Thomas CP, Gross TJ, Monick MM. Coordinated DNA methylation and gene expression changes in smoker alveolar macrophages: Specific effects on VEGF receptor 1 expression. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92:621–631. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1211632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aljubran SA, Cox R, Jr, Tamarapu Parthasarathy P, Kollongod Ramanathan G, Rajanbabu V, Bao H, Mohapatra SS, Lockey R, Kolliputi N. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 induces pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37712. doi: 10.1371/annotation/8580b50a-1556-4c86-aeb6-a88af839297a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stenmark KR, Fagan KA, Frid MG. Hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Circ Res. 2006;99:675–691. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000243584.45145.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groves BM, Reeves JT, Sutton JR, Wagner PD, Cymerman A, Malconian MK, Rock PB, Young PM, Houston CS. Operation everest II: Elevated high-altitude pulmonary resistance unresponsive to oxygen. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1987;63:521–530. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.2.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galiè N, Kim NH. Pulmonary microvascular disease in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:571–576. doi: 10.1513/pats.200605-113LR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barst RJ, McGoon M, Torbicki A, Sitbon O, Krowka MJ, Olschewski H, Gaine S. Diagnosis and differential assessment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(12 Suppl S):40S–47S. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Huang X, Leng D, Li J, Wang L, Liang Y, Wang J, Miao R, Jiang T. DNA methylation signatures of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Physiol Genomics. 2018;50:313–322. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00069.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogawa A, Firth AL, Yao W, Madani MM, Kerr KM, Auger WR, Jamieson SW, Thistlethwaite PA, Yuan JX. Inhibition of mTOR attenuates store-operated Ca2+ entry in cells from endarterectomized tissues of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L666–L676. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90548.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rouillard AD, Gundersen GW, Fernandez NF, Wang Z, Monteiro CD, McDermott MG, Ma'ayan A. The harmonizome: A collection of processed datasets gathered to serve and mine knowledge about genes and proteins. Database (Oxford) 2016;2016:baw100. doi: 10.1093/database/baw100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jassal B, Matthews L, Viteri G, Gong C, Lorente P, Fabregat A, Sidiropoulos K, Cook J, Gillespie M, Haw R, et al. The reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D498–D503. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie C, Mao X, Huang J, Ding Y, Wu J, Dong S, Kong L, Gao G, Li CY, Wei L. KOBAS 2.0: A web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39((Web Server Issue)):W316–W322. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humbert M. Pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: Pathophysiology. Eur Respir Rev. 2010;19:59–63. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00007309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Czermin B, Melfi R, McCabe D, Seitz V, Imhof A, Pirrotta V. Drosophila enhancer of Zeste/ESC complexes have a histone H3 methyltransferase activity that marks chromosomal Polycomb sites. Cell. 2002;111:185–196. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00975-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bracken AP, Pasini D, Capra M, Prosperini E, Colli E, Helin K. EZH2 is downstream of the pRB-E2F pathway, essential for proliferation and amplified in cancer. EMBO J. 2003;22:5323–5335. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang YX, Li JF, Yang YH, Zhai ZG, Gu S, Liu Y, Miao R, Zhong PP, Wang Y, Huang XX, et al. Renin-angiotensin system regulates pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell migration in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2018;314:L276–L286. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00515.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L, Liu J, Wang W, Qi X, Wang Y, Tian B, Dai H, Wang J, Ning W, Yang T, Wang C. Targeting IL-17 attenuates hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension through downregulation of β-catenin. Thorax. 2019;74:564–578. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varambally S, Cao Q, Mani RS, Shankar S, Wang X, Ateeq B, Laxman B, Cao X, Jing X, Ramnarayanan K, et al. Genomic loss of microRNA-101 leads to overexpression of histone methyltransferase EZH2 in cancer. Science. 2008;322:1695–1699. doi: 10.1126/science.1165395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frid MG, Moiseeva EP, Stenmark KR. Multiple phenotypically distinct smooth muscle cell populations exist in the adult and developing bovine pulmonary arterial media in vivo. Circ Res. 1994;75:669–681. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.75.4.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pugliese SC, Poth JM, Fini MA, Olschewski A, El Kasmi KC, Stenmark KR. The role of inflammation in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension: From cellular mechanisms to clinical phenotypes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;308:L229–L252. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00238.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rose-John S. Interleukin-6 family cytokines. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10:a028415. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a028415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karan D, Tawfik O, Dubey S. Expression analysis of inflammasome sensors and implication of NLRP12 inflammasome in prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4378. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04286-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen IC. Non-inflammasome forming NLRs in inflammation and tumorigenesis. Front Immunol. 2014;5:169. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hermanns HM. Oncostatin M and interleukin-31: Cytokines, receptors, signal transduction and physiology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2015;26:545–558. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyata M, Ito M, Sasajima T, Ohira H, Kasukawa R. Effect of a serotonin receptor antagonist on interleukin-6-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. Chest. 2001;119:554–561. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.2.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Unver N, McAllister F. IL-6 family cytokines: Key inflammatory mediators as biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2018;41:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye RD, Sun L. Emerging functions of serum amyloid A in inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;98:923–929. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3VMR0315-080R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Helgadottir A, Manolescu A, Thorleifsson G, Gretarsdottir S, Jonsdottir H, Thorsteinsdottir U, Samani NJ, Gudmundsson G, Grant SF, Thorgeirsson G, et al. The gene encoding 5-lipoxygenase activating protein confers risk of myocardial infarction and stroke. Nat Genet. 2004;36:233–239. doi: 10.1038/ng1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malle E, Sodin-Semrl S, Kovacevic A. Serum amyloid A: An acute-phase protein involved in tumour pathogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:9–26. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8321-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Buck M, Gouwy M, Wang JM, Van Snick J, Opdenakker G, Struyf S, Van Damme J. Structure and expression of different serum amyloid a (SAA) variants and their concentration-dependent functions during host insults. Curr Med Chem. 2016;23:1725–1755. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666160418114600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jumeau C, Awad F, Assrawi E, Cobret L, Duquesnoy P, Giurgea I, Valeyre D, Grateau G, Amselem S, Bernaudin JF, Karabina SA. Expression of SAA1, SAA2 and SAA4 genes in human primary monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0217005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Barbacioru C, Hyland F, Xiao W, Hunkapiller KL, Blake J, Chan F, Gonzalez C, Zhang L, Samaha RR. Large scale real-time PCR validation on gene expression measurements from two commercial long-oligonucleotide microarrays. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soon E, Crosby A, Southwood M, Yang P, Tajsic T, Toshner M, Appleby S, Shanahan CM, Bloch KD, Pepke-Zaba J, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II deficiency and increased inflammatory cytokine production. A gateway to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:859–872. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201408-1509OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Humbert M, Monti G, Brenot F, Sitbon O, Portier A, Grangeot-Keros L, Duroux P, Galanaud P, Simonneau G, Emilie D. Increased interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 serum concentrations in severe primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:1628–1631. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.5.7735624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Furuya Y, Satoh T, Kuwana M. Interleukin-6 as a potential therapeutic target for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Rheumatol. 2010;2010:720305. doi: 10.1155/2010/720305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang X, Coriolan D, Murthy V, Schultz K, Golenbock DT, Beasley D. Proinflammatory phenotype of vascular smooth muscle cells: Role of efficient Toll-like receptor 4 signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H1069–H1076. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00143.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonnet S, Michelakis ED, Porter CJ, Andrade-Navarro MA, Thébaud B, Bonnet S, Haromy A, Harry G, Moudgil R, McMurtry MS, et al. An abnormal mitochondrial-hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha-Kv channel pathway disrupts oxygen sensing and triggers pulmonary arterial hypertension in fawn hooded rats: Similarities to human pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2006;113:2630–2641. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.609008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sutendra G, Michelakis ED. The metabolic basis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cell Metab. 2014;19:558–573. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bonnet S, Archer SL, Allalunis-Turner J, Haromy A, Beaulieu C, Thompson R, Lee CT, Lopaschuk GD, Puttagunta L, Bonnet S, et al. A mitochondria-K+ channel axis is suppressed in cancer and its normalization promotes apoptosis and inhibits cancer growth. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:37–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Archer SL, Gomberg-Maitland M, Maitland ML, Rich S, Garcia JG, Weir EK. Mitochondrial metabolism, redox signaling, and fusion: A mitochondria-ROS-HIF-1alpha-Kv1.5 O2-sensing pathway at the intersection of pulmonary hypertension and cancer. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H570–H578. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01324.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cho KA, Suh JW, Lee KH, Kang JL, Woo SY. IL-17 and IL-22 enhance skin inflammation by stimulating the secretion of IL-1β by keratinocytes via the ROS-NLRP3-caspase-1 pathway. Int Immunol. 2012;24:147–158. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sutendra G, Dromparis P, Bonnet S, Haromy A, McMurtry MS, Bleackley RC, Michelakis ED. Pyruvate dehydrogenase inhibition by the inflammatory cytokine TNFα contributes to the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Mol Med (Berl) 2011;89:771–783. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yasui K, Baba A. Therapeutic potential of superoxide dismutase (SOD) for resolution of inflammation. Inflamm Res. 2006;55:359–363. doi: 10.1007/s00011-006-5195-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rabinovitch M, Guignabert C, Humbert M, Nicolls MR. Inflammation and immunity in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res. 2014;115:165–175. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bauer EM, Zheng H, Comhair S, Erzurum S, Billiar TR, Bauer PM. Complement C3 deficiency attenuates chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang J, Zhang Y, Li N, Liu Z, Xiong C, Ni X, Pu Y, Hui R, He J, Pu J. Potential diagnostic biomarkers in serum of idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir Med. 2009;103:1801–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Langer F, Schramm R, Bauer M, Tscholl D, Kunihara T, Schäfers HJ. Cytokine response to pulmonary thromboendarterectomy. Chest. 2004;126:135–141. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.von Haehling S, von Bardeleben RS, Kramm T, Thiermann Y, Niethammer M, Doehner W, Anker SD, Munzel T, Mayer E, Genth-Zotz S. Inflammation in right ventricular dysfunction due to thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2010;144:206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gu S, Su P, Yan J, Zhang X, An X, Gao J, Xin R, Liu Y. Comparison of gene expression profiles and related pathways in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Int J Mol Med. 2014;33:277–300. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.