Abstract

Aims

Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists (GLP‐1 RAs) are the recommended first injectable therapy in type 2 diabetes. However, long‐term persistence is suboptimal and partly attributable to gastrointestinal tolerability, particularly during initiation/escalation. Gradual titration of fixed‐ratio combination GLP‐1 RA/insulin therapies may improve GLP‐1 RA gastrointestinal tolerability. We compared gastrointestinal adverse event (AE) rates for iGlarLixi versus GLP‐1 RAs during the first 12 weeks of therapy, including a sensitivity analysis with IDegLira.

Materials and methods

The PICO framework was used to identify studies from MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL searches using a proprietary, web‐based, standardized tool with single data extraction. Gastrointestinal AEs were modelled using a Bayesian network meta‐analysis (NMA), using fixed and random effects for each recommended dose (treatment‐specific NMA) and class (drug‐class NMA).

Results

Treatment‐specific NMA included 17 trials (n = 9030; 3665 event‐weeks). Nausea rates were significantly lower with iGlarLixi versus exenatide 10 μg twice daily (rate ratio: 0.32; 95% credible interval: 0.15, 0.66), once‐daily lixisenatide 20 μg (0.35; 0.24, 0.50) and liraglutide 1.8 mg once daily (0.48; 0.23, 0.98). Rates were numerically, but not statistically, lower versus once‐weekly semaglutide 1 mg (0.60; 0.30, 1.23) and dulaglutide 1.5 mg (0.60; 0.29, 1.26), and numerically, but not statistically, higher versus once‐weekly exenatide (1.91; 0.91, 4.03). Sensitivity analysis results were similar. In a naïve, pooled analysis, vomiting was lower with iGlarLixi versus other GLP‐1 RAs.

Conclusions

During the first 12 weeks of treatment, iGlarLixi was generally associated with less nausea and vomiting than single‐agent GLP‐1 RAs. Enhanced gastrointestinal tolerability with fixed‐ratio combinations may favour treatment persistence.

1. INTRODUCTION

Achieving and maintaining glycaemic goals for people with type 2 diabetes are important to reduce diabetes‐associated complications. 1 A number of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists (GLP‐1 RAs) are currently approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, and may be classified according to their plasma half‐life, as either short‐acting (exenatide and lixisenatide) or long‐acting (liraglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide extended‐release and semaglutide). Although all GLP‐1 RAs reduce fasting and postprandial glucose (PPG) levels, short‐acting GLP‐1 RAs show greater reductions in PPG versus longer‐acting agents, and have greater effects on slowing gastric emptying. 2 Given their high glucose‐lowering efficacy, association with weight loss, low risk of hypoglycaemia, 3 capacity to reduce cardiovascular risk factors, 4 and beneficial effect on multiple pathophysiologic abnormalities in type 2 diabetes, 5 , 6 GLP‐1 RAs are currently recommended as the first injectable therapy for people with type 2 diabetes who need treatment intensification. 7 Despite this, outcomes of real‐world studies indicate that long‐term persistence with GLP‐1 RA therapy is suboptimal. For example, in a study of people treated with exenatide or liraglutide in the United States, <50% of the population demonstrated optimal adherence. 8 A number of factors may contribute to poor long‐term persistence with GLP‐1 RA therapy, including gastrointestinal (GI) tolerability, 9 dislike of injectable administration, cost and lower than expected efficacy. 10

GI adverse events (AEs), in particular, are regarded as a major reason for a low persistence rate. In reviews of clinical trials involving GLP‐1 RA therapy, nausea was reported to occur in 24%‐60% of participants, vomiting 5%‐15% and diarrhoea 9%‐20%. 11 , 12 In a survey of 443 physicians who reported on patient discontinuation of GLP‐1 RA therapy in the previous 6 months, nausea/vomiting was considered to be the cause in 43.8% of cases. Of 194 patients who were surveyed in the same study, nausea and vomiting were two major reasons for GLP‐1 RA discontinuation, being reported by 64% and 45% of patients, respectively. 10

GI AEs are known to occur early after initiation of therapy and during treatment escalation. 13 , 14 Although GI AEs may sometimes persist with long‐term use, there is evidence showing that after initiation of exenatide twice daily, the incidence of nausea peaked at weeks 4‐6 and declined thereafter, and that after initiation of liraglutide, the incidence of nausea was highest during the first 4 weeks of treatment. 14 Results of another study suggested that after initiation of lixisenatide, ‘the onset of gastrointestinal adverse reactions was observed during the first 5 weeks of the study in the majority of cases’. 15

By virtue of their small, incremental, gradual titration and thus reduced exposure to the GLP‐1 RA component, and possibly because a lower dose of GLP‐1 RA may be needed to achieve the required glucose lowering, fixed‐ratio combination (FRC) therapies of insulin/GLP‐1 RA may be associated with enhanced GI tolerability relative to their GLP‐1 RA components when administered alone. 9 , 16 Current FRC therapies of insulin/GLP‐1 RA include iGlarLixi (insulin glargine 100 U/mL/lixisenatide 33 μg/mL) and IDegLira (insulin degludec 100 U/mL/liraglutide 3.6 mg/mL). Studies indicate that GI AEs were lower for the FRCs versus their respective single‐agent GLP‐1 RA. 9 , 12 , 16 While these studies highlight the lower rates of GI AEs for single comparisons of FRC therapies against their specific GLP‐1 RA components, comparisons have not been made across the entire GLP‐1 RA class.

Given this absence of head‐to‐head comparison of iGlarLixi versus GLP‐1 RA therapies (other than lixisenatide) when administered alone, we performed a systematic literature review and network meta‐analysis (NMA) to compare the GI tolerability profile of iGlarLixi with short‐ or long‐acting single‐agent GLP‐1 RA therapies during the first 12 weeks of treatment. To broaden evaluation across the FRC class and strengthen the assessment, a sensitivity analysis including IDegLira was also performed.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A protocol was developed a priori and reviewed by a technical expert panel. Reporting followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 17

2.1. Data sources and searches

Systematic literature searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL were performed to identify randomized controlled trials with weekly data for any GI AE in adults (≥18 years) with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes who were naïve to GLP‐1 RAs. Searches of studies performed in any setting and published in English were conducted from inception date to September 2018 (and the previous 2 years for conferences). The full electronic search strategy for articles obtained from MEDLINE is shown in Table S1.

2.2. Study selection

The PICO framework [P, patient or population; I, intervention; C, comparator; O, outcome(s)] 18 was used to identify relevant studies. Only studies that included or were highly likely to include individuals who were naïve to GLP‐1 RA therapy at entry were examined. To ascertain the suitability of studies that did not specifically state whether participants were naïve to GLP‐1 RA therapy, the following exclusion criteria were used: previous treatment with any glucose‐lowering drug within 3 months of the trial; use of any treatment other than oral glucose‐lowering agents that could affect blood glucose concentration; and use of a GLP‐1 RA before screening. Permitted interventions included GLP‐1 RAs (e.g. albiglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, liraglutide, lixisenatide, semaglutide, taspoglutide) with or without oral antidiabetic (OAD) background therapy (e.g. sodium‐glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors, thiazolidinediones, sulfonylureas, metformin); iGlarLixi; and IDegLira. Comparators included any of the above or OAD/insulin combinations.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

A proprietary, web‐based, standardized data extraction tool [Digital Outcome Conversion (DOC) Data 2.0; Doctor Evidence LLC, Santa Monica, California, USA] 19 was used to conduct a single extraction with two layers of quality control whereby each data point was double‐checked, followed by a global second check to look for outliers. The system has safeguards to prevent input of impossible data into each field. All characteristics were collected as reported in each paper and synonyms were bound before analysis using the DOC Data platform. The revised Cochrane risk‐of‐bias tool 2 (Rob2) 20 was used to assess the risk of bias at the outcome level. Outcomes were reported as the number of participants with a GI AE per week. Each participant could contribute to multiple events over time, but only the first event was counted each week. Study withdrawal and drug discontinuation due to GI AEs were also examined.

2.4. Data synthesis and analysis

A Bayesian NMA was used to model cumulative data for the first 12 weeks of treatment, using both fixed and random‐effects models. The recommended, fully titrated dose of each GLP‐1 RA was examined, both individually (termed Treatment‐Specific Network) and when grouped according to class (short‐ or long‐acting agent; termed Drug‐Class Network). GI AEs (nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea) were extracted from tables or, if necessary, from plots using digitization software (DOC Data 2.0). 19 Data were collected from individual trials at weekly intervals to assess ‘early’ GI AEs. Analysis at specific time points (e.g. 2, 4, 8 and 12 weeks) was limited because too few GI AEs were reported to conduct analyses at 8 and 12 weeks. Therefore, the cumulative number of event‐weeks (weeks in which a person had one or more episodes) over the first 12 weeks was analysed using an NMA with Poisson likelihood. Heterogeneity was verified for each pairwise comparison using the I 2 statistic and inconsistency was assessed using both node splitting and Bucher tests. Model selection was conducted using the deviance information criterion according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence conventions. 21 This criterion provides a measure of model fit that penalizes for model complexity. The primary aim was comparison of the GI tolerability profile of iGlarLixi with short‐ or long‐acting, single‐agent GLP‐1 RA therapies, but the protocol and statistical analysis plan also allowed sensitivity analyses in which the FRC IDegLira was added to the network. For outcomes for which an NMA was not deemed feasible, a naïve pooled analysis was conducted. Two sensitivity analyses were conducted, i.e. one adding IDegLira to the network, and the other restricting the analysis to open‐label trials (an analysis restricting the included studies to double‐blind trials was not feasible, as the network was too sparse). Significance was assessed at the .05 level. Model parameters were estimated using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo method implemented in the JAGS software package (version 4.3). A first series of 20 000 iterations from the JAGS sampler were discarded as ‘burn‐in’, and the inferences were based on additional 30 000 iterations using two chains. For all analyses, model convergence was assessed through trace plots, density plots and Gelman‐Rubin‐Brooks (shrink factor) plots.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Systematic literature review results

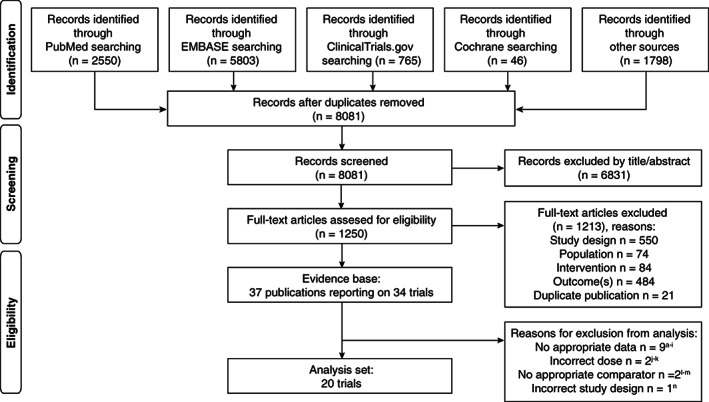

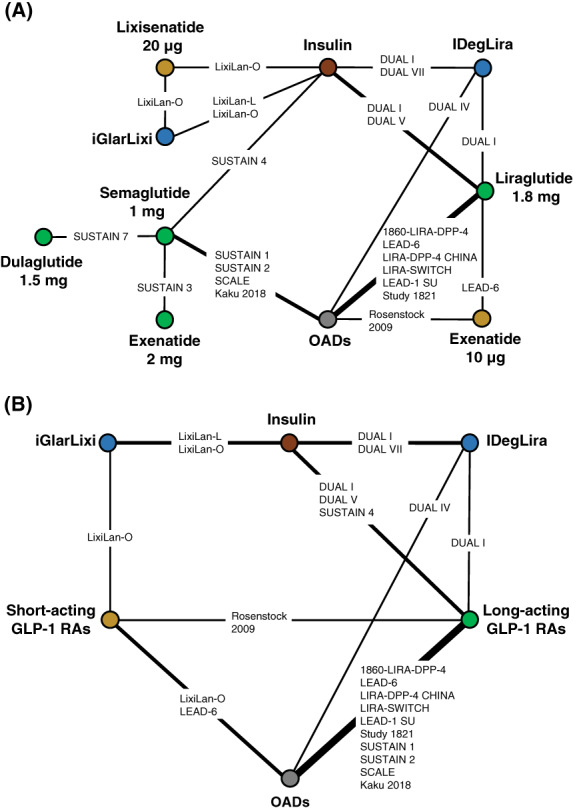

After removal of duplicates, 8081 records were screened, and 37 publications reporting on 34 trials met the PICO inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Of these, 14 trials were excluded from the analysis set. The reasons were no appropriate data (nine trials), incorrect dose for the intervention (two trials), no appropriate comparator (two trials) and incorrect study design (one trial) (Figure 1). Up to 20 trials were included in the treatment‐specific NMA for nausea (Figure 2, Table 1), which formed a connected network. The risk of bias assessment is shown in Table S2 and baseline characteristics for the trials included in the analysis set are provided in Table S3. Trials were generally similar for the baseline characteristics of age, glycated haemoglobin and other clinical variables, but there were some sources of heterogeneity, namely differences in type 2 diabetes duration and study populations. For example, most trials included metformin as a background therapy and had recruited individuals who were receiving a second or third OAD therapy, but some included those receiving a first OAD therapy. Two trials enrolled only Japanese participants, while the remainder of trials enrolled predominantly white participants. No important heterogeneity was found between the studies for pairwise comparisons when more than one study was available, and no heterogeneity was found between the studies for the effect of OADs (control group). As such, these differences were assumed not to be treatment effect modifiers, and further analyses within each group were not pursued.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. aNauck MA, Stewart MW, Perkins C, et al. Diabetologia 2016;59:266‐274; bPratley RE, Nauck MA, Barnett AH, et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:289‐297; cGiorgino F, Benroubi M, Sun JH, Zimmermann AG, Pechtner V. Diabetes Care 2015;38:2241‐2249; dDungan KM, Povedano ST, Forst T, et al. Lancet. 2014;384:1349‐1357; eDerosa G, Franzetti IG, Querci F, et al. Diabet Med 2012;29:1515‐1523; fRatner R, Nauck M, Kapitza C, Asnaghi V, Boldrin M, Balena R. Diabet Med 2010;27:556‐562; gWysham C, Blevins T, Arakaki R, et al. Diabetes Care 2014;37:2159‐2167; hLingvay I, Desouza CV, Lalic KS, et al. Diabetes Care 2018;41:1926‐1937; iSeino Y, Terauchi Y, Osonoi T, et al. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018;20:378‐388; jReusch J, Stewart MW, Perkins CM, et al. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014;16:1257‐1264; kHollander P, Lasko B, Barnett AH, et al. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:238‐247; lWysham CH, MacConell L, Hardy E. Diabetes Care 2016;39:1768‐1776; mRosenstock J, Rodbard HW, Bain SC, et al. J Diabetes Complications. 2013;27:492‐500; nSeino Y, Stjepanovic A, Takami A, Takagi H; study investigators. J Diabetes Investig 2018;9:127‐136

FIGURE 2.

A, Nausea treatment‐specific network. B, Nausea drug‐class network. Nodes represent treatments; lines connect every head‐to‐head comparison. IDegLira was included for sensitivity analysis only. FRC, fixed‐ratio combination; GLP‐1 RAs, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists; IDegLira, FRC of insulin degludec and liraglutide; iGlarLixi, FRC of insulin glargine and lixisenatide; OAD, oral antidiabetics

TABLE 1.

Trials included in treatment‐specific and drug‐specific NMA for nausea

| Trial | Treatment‐specific NMA | Drug‐class NMA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without IDegLira | With IDegLira | Without IDegLira | With IDegLira | |

| 1860‐LIRA‐DPP‐4 44 | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| DUAL‐I 45 | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| DUAL‐IV 46 | Excluded | Included | Excluded | Included |

| DUAL‐V 47 | Excluded | Included | Excluded | Included |

| DUAL‐VII 48 | Excluded | Included | Excluded | Included |

| Kaku K 2018 49 | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| LEAD‐1 SU 50 | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| LEAD‐6 51 | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| LIRA‐DPP‐4 CHINA 52 | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| LIRA‐SWITCH 53 | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| LixiLan‐L 9 | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| LixiLan‐O 12 | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Rosenstock J 2009 54 | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| SCALE 55 | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Study 1821 56 | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| SUSTAIN 1 57 | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| SUSTAIN 2 58 | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| SUSTAIN 3 59 | Included | Included | Excluded | Excluded |

| SUSTAIN 4 60 | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| SUSTAIN 7 61 | Included | Included | Excluded | Excluded |

Abbreviations: IDegLira, FRC of insulin degludec and liraglutide; NMA, network meta‐analysis

The raw data of the outcomes used in the analysis are shown in Table S4. Based on this, two networks using the recommended GLP‐1 RA dose were considered for nausea: a treatment‐specific NMA and a drug‐class (short‐ and long‐acting GLP‐1 RAs) NMA. For both networks, the estimated pairwise heterogeneity was zero throughout and all P‐values for inconsistency were ≥.195. Data for vomiting were not reported in all studies, and neither were they reported as consistently defined variables across different studies. Therefore, the network for vomiting was disconnected from iGlarLixi and analysis of this outcome using an NMA was not feasible. To provide further information on this outcome, a naïve pooled analysis (i.e. findings from the active treatment arms were pooled) 22 was used to assess vomiting. Other GI outcomes such as diarrhoea were under‐reported and an NMA was not feasible. Other AEs such as pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma were reviewed, but there were insufficient data for analysis.

3.2. Analysis outcomes

3.2.1. Treatment‐specific network meta‐analysis results

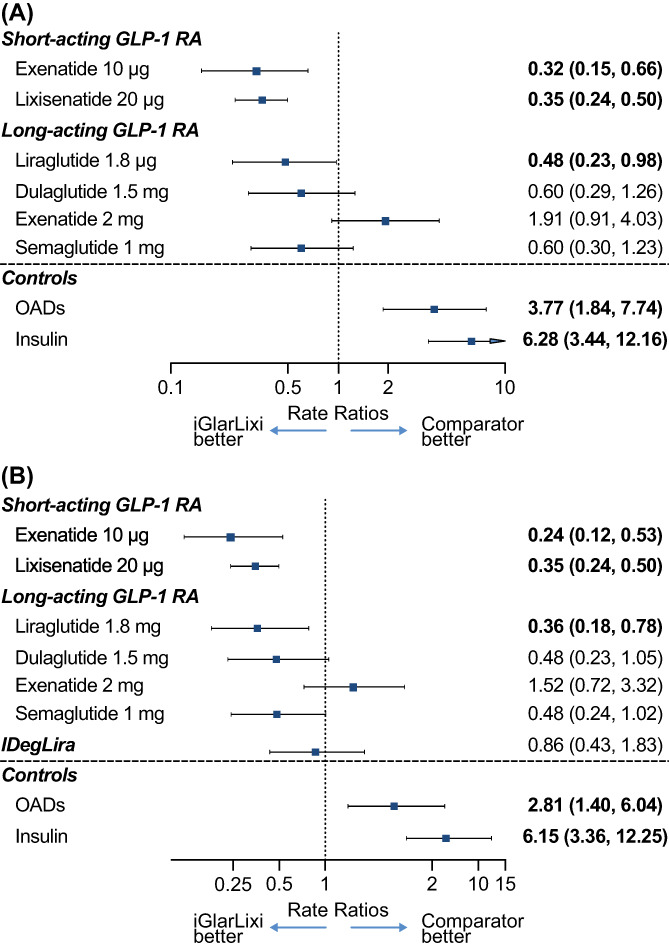

The 17 trials included in the treatment‐specific NMA involved 9030 individuals reporting on 3665 event‐weeks. The list of included trials and the resulting network of evidence are presented in Figure 2A, Table 1. In the treatment‐specific fixed‐effect NMA model, nausea rates for iGlarLixi were significantly lower than those for titrated doses of exenatide 10 μg twice daily [rate ratio: 0.32; 95% credible interval (CrI): 0.15, 0.66], once‐daily lixisenatide 20 μg (0.35; 95% CrI: 0.24, 0.50) and once‐daily liraglutide 1.8 mg (0.48; 95% CrI: 0.23, 0.98) (Figure 3). Nausea rates for iGlarLixi were numerically, but not statistically, lower versus semaglutide 1 mg once weekly (0.60; 95% CrI: 0.30, 1.23) or dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly (0.60; 95% CrI: 0.29, 1.26), and were numerically, but not statistically, higher versus exenatide 2 mg once weekly (1.91; 95% CrI: 0.91, 4.03) (Figure 3A).

TABLE 2.

| A: Drug‐class random‐effects NMA model for nausea | |||||

| Rate ratio (95% credible interval) | |||||

| iGlarLixi | 0.52 (0.11, 3.60) | 0.80 (0.16, 5.98) | 8.16 (1.64, 72.98) | 9.95 (2.66, 64.85) | |

| Short‐acting GLP‐1 RAs | 1.54 (0.44, 5.40) | 15.67 (4.67, 63.34) | 19.12 (4.77, 81.24) | ||

| Long‐acting GLP‐1 RAs | 10.21 (5.57, 22.13) | 12.40 (3.93, 43.04) | |||

| OADs | 1.21 (0.29, 4.48) | ||||

| Insulin | |||||

| B: Drug‐class random‐effects NMA model for nausea at 12 weeks – sensitivity analysis including IDegLira | |||||

| Rate ratios (random effects; 95% credible interval) | |||||

| iGlarLixi | 0.49 (0.09, 3.64) | 0.69 (0.12, 5.41) | 6.71 (1.19, 60.76) | 12.01 (2.64, 85.41) | 1.65 (0.26, 16.01) |

| Short‐acting GLP‐1 RAs | 1.41 (0.38, 5.49) | 13.68 (3.78, 60.93) | 24.69 (5.91, 114.62) | 3.38 (0.65, 19.95) | |

| Long‐acting GLP‐1 RAs | 9.71 (4.95, 21.56) | 17.43 (5.42, 59.84) | 2.37 (0.66, 9.63) | ||

| OADs | 1.80 (0.47, 6.43) | 0.25 (0.06, 0.96) | |||

| Insulin | 0.14 (0.04, 0.49) | ||||

| IDegLira | |||||

Note: Results are rate ratios with 95% credible intervals of row versus column treatment. Results in bold type show statistical significance at the .05 level. For the sensitivity analysis, the random‐effects model was favoured.

Abbreviations: FRC, fixed‐ratio combination; GLP‐1 RA, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist; IDegLira, FRC of insulin degludec and liraglutide; iGlarLixi, FRC of insulin glargine and lixisenatide; NMA, network meta‐analysis; OAD, oral antidiabetic.

FIGURE 3.

A, Treatment‐specific fixed‐effect NMA model for nausea with iGlarLixi versus other GLP‐1 RAs, OADs and insulin. B, Treatment‐specific NMA model for nausea at 12 weeks – sensitivity analysis including IDegLira. Results are rate ratios with 95% credible intervals. Results in bold type show statistical significance at the .05 level. For the sensitivity analysis, the random‐effects model was favoured. FRC, fixed‐ratio combination; GLP‐1 RA, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist; IDegLira, FRC of insulin degludec and liraglutide; iGlarLixi, FRC of insulin glargine and lixisenatide; NMA, network meta‐analysis; OADs, oral antidiabetics

3.2.2. Pooled analysis of vomiting adverse events

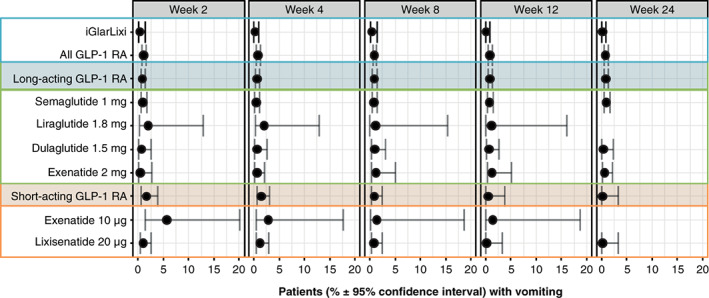

As an NMA was not feasible for vomiting, a pooled analysis of vomiting episodes per week was conducted based on the random‐effects meta‐analysis. The results suggest that during the first 12 weeks of treatment, vomiting was experienced by fewer individuals who received treatment with iGlarLixi compared with single‐agent short‐ or long‐acting GLP‐1 RAs. At week 12, the incidence of vomiting for those who received iGlarLixi was 0.12% [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.02‐0.85] compared with 0.54% (95% CI: 0.08‐3.76) for short‐acting GLP‐1 RAs and 0.83% (95% CI: 0.51‐1.34) for long‐acting GLP‐1 RAs. Results showing the proportions of individuals with vomiting at all specified time points are detailed in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Proportion of individuals with vomiting (based on random‐effects meta‐analysis). FRC, fixed‐ratio combination; GLP‐1 RA, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist; iGlarLixi, FRC of insulin glargine and lixisenatide

3.2.3. Drug‐class network network meta‐analysis results

In total, 16 trials were included in the drug‐class random‐effects NMA model. These involved 7686 individuals (Figure 2B). In this model, the rate ratio (95% CrI) for iGlarLixi versus short‐acting GLP‐1 RAs was 0.52 (95% CrI: 0.11, 3.60) and 0.80 (95% CrI: 0.16, 5.98) versus long‐acting GLP‐1 RAs (Table 2A).

3.2.4. Sensitivity analyses

For the sensitivity analyses that included IDegLira, the treatment‐specific NMA included 20 trials involving 11 351 individuals. Results for the comparison of iGlarLixi with single‐agent GLP‐1 RAs were comparable with those of the main analysis. The rate ratio for nausea for iGlarLixi versus IDegLira was 0.86 (95% CrI: 0.43, 1.83; Figure 3B). In total, 19 trials involving 10 007 individuals were included in the drug‐class network sensitivity analysis that included IDegLira. As for the treatment‐specific NMA, these results (Table 2B) were similar to the main analysis, and there was no definitive difference in nausea rates between iGlarLixi and IDegLira, although the direction of the estimate for iGlarLixi with IDegLira was reversed (rate ratio: 1.65) and the CrI was wide (95% CrI: 0.26, 16.01). Results of the sensitivity analysis restricted to open‐label trials are summarized in Table S5‐A and S5‐B. These results were comparable with those of the principal analysis.

4. DISCUSSION

While GLP‐1 RAs have an established benefit‐risk profile and are increasingly recommended in clinical practice, 3 real‐world studies show there is considerable non‐persistence with GLP‐1 RA therapy either when used alone 23 or as part of a free‐dose combination with basal insulin. 24 For example, a study across six European countries showed that the rate of persistence with therapy after 1 year post‐index was 5.9%‐44.4% for exenatide twice daily, 15.5%‐40.0% for lixisenatide, 22.2%‐57.5% for liraglutide, 24.7%‐44.2% for exenatide once weekly and 36.8%‐67.2% for dulaglutide. 25 A propensity score matched analysis of data from Truven Health's MarketScan Research Databases showed that individuals treated with dulaglutide had significantly higher adherence versus exenatide once weekly (0.72 vs. 0.61; P < .0001) or liraglutide (0.71 vs. 0.67; P < .0001), and were more persistent with therapy (% patients achieving PDC ≥0.80: dulaglutide vs. exenatide once weekly; 54.2% vs. 37.9%, P < .0001; dulaglutide vs. liraglutide; 53.5% vs. 44.3%; P < .0001). 26 Results from a retrospective cohort study (IMS LifeLink database) that assessed persistence with GLP‐1 RA therapy in adults from Italy showed that at 6 months after treatment initiation, patients prescribed exenatide twice daily had the lowest persistence (35%) and those prescribed dulaglutide had the highest (62%). Rates for exenatide weekly, liraglutide once daily, and lixisenatide once daily were 47%, 50% and 40%, respectively. Over the entire follow‐up, median persistence varied from 73 days with exenatide twice daily to >300 days with dulaglutide. 27

The lack of persistence with GLP‐1 RA therapy is thought, at least in part, to be attributable to GI AEs, which are the most frequently reported treatment‐related AEs associated with this drug class, occurring predominantly during treatment initiation and titration. 11 , 14 In the absence of head‐to‐head clinical study data comparing the incidence of GI AEs with iGlarLixi versus other short‐ or long‐acting GLP‐1 RA therapies administered alone, this NMA was conducted to compare the GI tolerability profile of the FRC iGlarLixi with single‐agent GLP‐1 RA therapies during the first 12 weeks of treatment. A sensitivity analysis with IDegLira was included to broaden results and provide further understanding of the FRC class. The results show that during the first 12 weeks of treatment initiation, compared with many single GLP‐1 RA therapies, iGlarLixi is associated with lower rates of nausea (per the NMA), and vomiting (per the naïve pooled analysis). Results for the IDegLira sensitivity analysis were consistent with the primary analysis.

When basal insulin/GLP‐1 RA FRCs such as iGlarLixi and IDegLira are used, the dose of the GLP‐1 RA component is increased or decreased in a fixed ratio with the insulin dose, and is changed in small increments, facilitating gradual titration. It is important to note that FRCs are not fixed‐dose combinations; rather, doses are guided by the insulin component, following titration schedules similar to those used for titrating insulin, 28 , 29 thus providing flexibility in dosing, with the GLP‐1 RA component increasing in proportion to the insulin dose. The starting dose of the GLP‐1 RA component is lower than when given alone, and the gradual titration appears to result in improved GI tolerability. Furthermore, the final dose of the GLP‐1 RA component within the FRC may be less than that when administered as a single‐agent GLP‐1 RA. For example, in the LixiLan‐O study, the final dose of lixisenatide in iGlarLixi was 16‐17 μg 30 rather than the 20 μg used as monotherapy. There is evidence that the maximal effect of lixisenatide on PPG concentrations is achieved at a dose of 12.5 μg, and as such, it may not be necessary to use the maximal available dose. 31 Similarly, in the DUAL‐1 study, mean liraglutide doses were lower for the IDegLira group than for the liraglutide group (1.4 vs. 1.8 mg at week 26). 16 This could explain why iGlarLixi and IDegLira were associated with enhanced GI tolerability relative to their GLP‐1 RA components administered as single agents. In the LixiLan‐O trial, rates of overall GI AEs (21.7% vs. 36.9%), nausea (9.6% vs. 24.0%) and vomiting (3.2% vs. 6.4%) were lower for iGlarLixi than for lixisenatide. 12 Real‐world studies with FRCs also suggest enhanced tolerability with potential for greater treatment persistence. Results from a real‐world, multicentre, retrospective chart review of 611 European adults with type 2 diabetes who started IDegLira ≥6 months before data collection, showed that of the 109 participants who discontinued IDegLira within 12 months, GI adverse effects accounted for only 4.6% of cases, with 29.4% of the group discontinuing due to insufficient efficacy and 16.5% due to high cost. 32

The results of the current analysis reveal that during the first 12 weeks of treatment, iGlarLixi is associated with lower rates of nausea and vomiting versus the single‐agent short‐acting GLP‐1 RA therapies exenatide 10 μg and lixisenatide 20 μg. iGlarLixi was also associated with a lower rate of nausea compared with the long‐acting GLP‐1 RA liraglutide 1.8 mg, and with a non‐statistically significant reduced rate versus dulaglutide 1.5 mg and semaglutide 1 mg. Nausea rates with iGlarLixi were not lower than those with exenatide once weekly. A period of 6‐8 weeks is required to reach steady state after administration of exenatide once weekly, 33 , 34 , 35 which may result in improved GI tolerability compared with other GLP‐1 RAs.

In a recent analysis of GI AEs after administration of exenatide once weekly, exenatide twice daily, or liraglutide, 14 upper GI AEs were found to be less common with exenatide once weekly versus exenatide twice daily and liraglutide, and rates of lower GI AEs were comparable across treatments, with the exception of diarrhoea, which occurred more frequently with liraglutide than with exenatide once weekly. In keeping with this report, 14 we found similar rates of nausea for GLP‐1 RAs in the present study. Possible reasons for the variance in GI AEs between different GLP‐1 RAs include differences in pharmacokinetics and the potential for differences in capacity to cross the blood‐brain barrier. Consequently, there were differences in rates of centrally mediated AEs, although this has only been assessed in preclinical studies in mice. 36 Another consideration is that sustained exposure of the GLP‐1 receptor is known to cause tachyphylaxis for the effects of exogenous GLP‐1 on the slowing of gastric emptying. 37 It is possible that a reduced effect of long‐ versus short‐acting GLP‐1 RAs to slow gastric emptying may contribute to the lower incidence of GI AEs with long‐acting GLP‐1 RAs; however, it has recently been demonstrated that exenatide once weekly slows gastric emptying significantly even at steady‐state concentrations. 38 Moreover, the suppression of energy intake by lixisenatide is not related to slowing of gastric emptying or changes in intragastric meal distribution. 39 It is notable that recent updates to titration schemas for weekly GLP‐1 RA therapies have incorporated extended titration steps for up to 4 weeks to help minimize GI AEs. 40 , 41 , 42

The strengths of our analysis include a comprehensive literature search based on standardized prespecified search criteria, with confounding reduced by using only studies with the recommended titrated dose of each GLP‐1 RA. Limitations include both the variability in definitions of GI AEs and the self‐reporting of GI AEs, which may be influenced either by the expectation that they will occur (nocebo effect) or by an opinion that one treatment is less likely to cause GI AEs than another (precebo effect). 43 Other limitations include the lack of data feasibility to construct an NMA for vomiting or diarrhoea, lack of information about changes in weight of the study participants, and differences in properties of lixisenatide and liraglutide that may contribute to the outcomes observed with iGlarLixi and IDegLira. The findings of this analysis could be further explored in additional analyses of the FRC class through head‐to‐head studies, and by the addition of real‐world studies to assess the potential long‐term benefits of minimizing GI AEs during early treatment.

In conclusion, this study suggests a mitigation of GI AEs with the gradual titration of GLP‐1 RA via FRC therapy compared with single‐agent GLP‐1 RAs. In this NMA, lixisenatide in the FRC of iGlarLixi was associated with clinically meaningful lower rates of GI AEs compared with those observed with many single‐agent GLP‐1 RAs, but not exenatide once weekly. The results help inform healthcare providers about differences between GLP‐1 RA‐containing therapies and may allow for individualization of therapy in people with type 2 diabetes to improve their experience and persistence with therapy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

C.K.R. has received research funding from AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis and Sanofi, and has participated in advisory boards for Allergan (now AbbVie). T.W. has received travel support from Novartis and Sanofi, and research funding from AstraZeneca and Novartis. V.R.A. has served as a consultant for Adocia, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BD, Duke, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi and Zafgen, and has received research support from Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca/BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Calibra, Eisai, Premier/Fractyl, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi and Theracos. C.W. was employed by Doctor Evidence at the time of the study. S.K. is an employee of Doctor Evidence, which has received funding from Sanofi, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis and Novo Nordisk. C.W. and P.G. are employees and stockholders of Sanofi. A.S. was an employee and stockholder of Sanofi at the time of study conduct. M.H. has participated in advisory boards and/or symposia for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis and Novo Nordisk.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.K.R. interpreted the data and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. T.W. interpreted the data and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. V.R.A. was involved in the study design and data interpretation, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. C.W. was involved in the study design, data analysis and data interpretation, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. S.K. analysed and interpreted the data, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. P.G. was involved in the study design, data analysis and data interpretation, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. A.S. was involved in the study design and data interpretation, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. M.H. interpreted the data and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Qualified researchers may request access to patient level data and related study documents including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, statistical analysis plan, and dataset specifications. Patient level data will be anonymized and study documents will be redacted to protect the privacy of our trial participants. Further details on Sanofi's data sharing criteria, eligible studies, and process for requesting access can be found at: https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/

Supporting information

Table S1 Example full electronic search strategy.

Table S2 Risk of bias assessment results.

Table S3 Study characteristics.

Table S4 Raw data of the outcomes used for analyses and effect estimates with CIs for each study.

Table S5 A Drug‐class random‐effects NMA model for nausea – sensitivity analysis restricted to open‐label trials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This analysis was funded by Sanofi US, Inc. The authors received medical writing support for the preparation of this manuscript provided by Helen Jones, PhD, CMPP, of Evidence Scientific Solutions, funded by Sanofi US, Inc.

Rayner CK, Wu T, Aroda VR, et al. Gastrointestinal adverse events with insulin glargine/lixisenatide fixed‐ratio combination versus glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A network meta‐analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23:136–146. 10.1111/dom.14202

REFERENCES

- 1. Einarson TR, Acs A, Ludwig C, Panton UH. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review of scientific evidence from across the world in 2007–2017. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meier JJ, Rosenstock J, Hincelin‐Méry A, et al. Contrasting effects of lixisenatide and liraglutide on postprandial glycemic control, gastric emptying, and safety parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes on optimized insulin glargine with or without metformin: a randomized, open‐label trial. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1263‐1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hinnen D. Glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptor agonists for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2017;30:202‐210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Giorgino F, Shaunik A, Liu M, Saremi A. Achievement of glycaemic control is associated with improvements in lipid profile with iGlarLixi versus iGlar: a post hoc analysis of the LixiLan‐L trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:2712‐2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DeFronzo RA. Banting lecture. From the triumvirate to the ominous octet: a new paradigm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2009;58:773‐795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DeFronzo RA, Eldor R, Abdul‐Ghani M. Pathophysiologic approach to therapy in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl 2):S127‐S138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Diabetes Association . 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes‐2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:S98‐S110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnston SS, Nguyen H, Felber E, et al. Retrospective study of adherence to glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the United States. Adv Ther. 2014;31:1119‐1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Trujillo JM, Roberts M, Dex T, Chao J, White J, LaSalle J. Low incidence of gastrointestinal adverse events over time with a fixed‐ratio combination of insulin glargine and lixisenatide versus lixisenatide alone. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:2690‐2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sikirica MV, Martin AA, Wood R, Leith A, Piercy J, Higgins V. Reasons for discontinuation of GLP1 receptor agonists: data from a real‐world cross‐sectional survey of physicians and their patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2017;10:403‐412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meier JJ. GLP‐1 receptor agonists for individualized treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8:728‐742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosenstock J, Aronson R, Grunberger G, et al. Benefits of LixiLan, a titratable fixed‐ratio combination of insulin glargine plus lixisenatide, versus insulin glargine and lixisenatide monocomponents in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on oral agents: the LixiLan‐O randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:2026‐2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bettge K, Kahle M, Abd El Aziz MS, Meier JJ, Nauck MA. Occurrence of nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea reported as adverse events in clinical trials studying glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists: a systematic analysis of published clinical trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:336‐347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Horowitz M, Aroda VR, Han J, Hardy E, Rayner CK. Upper and/or lower gastrointestinal adverse events with glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists: incidence and consequences. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:672‐681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ratner RE, Rosenstock J, Boka G, on behalf of the DRI6012 Study Investigators. Dose‐dependent effects of the once‐daily GLP‐1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2010;27:1024‐1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gough SC, Bode B, Woo V, et al. Efficacy and safety of a fixed‐ratio combination of insulin degludec and liraglutide (IDegLira) compared with its components given alone: results of a phase 3, open‐label, randomised, 26‐week, treat‐to‐target trial in insulin‐naive patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:885‐893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Doctor Evidence . Digital Outcome Conversion (DOC). Program developed by Doctor Evidence, 301 Arizona Ave, Suite 301, Santa Monica, CA 90401, USA https://drevidence.com/doc-analytics. Accessed January 14, 2020.

- 20. Cochrane Methods . RoB 2: a revised Cochrane risk‐of‐bias tool for randomized trials. https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/resources/rob‐2‐revised‐cochrane‐risk‐bias‐tool‐randomized‐trials. Accessed February 17, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21. Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, Ades AE. NICE DSU Technical Support Document 2: A Generalised Linear Modelling Framework for Pairwise and Network Meta‐Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. London, England: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, Walter SD. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:683‐691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weiss T, Iglay K, Carr R, Pratap Mishra A, Yang L, Rajpathak S. Real‐world adherence and discontinuation of GLP‐1 receptor agonist (GLP‐1 RA) therapy in type 2 diabetes (T2D) patients in the United States. Poster presented at the 2019 American Diabetes Association Congress, San Francisco, CA, USA, June 7‐11, 2019. Poster 984‐P.

- 24. Lin J, Lingohr‐Smith M, Fan T. Real‐world medication persistence and outcomes associated with basal insulin and glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptor agonist free‐dose combination therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes in the US. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;9:19‐29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Divino V, Boye KS, Lebrec J, DeKoven M, Norrbacka K. GLP‐1 RA treatment and dosing patterns among type 2 diabetes patients in six countries: a retrospective analysis of pharmacy claims data. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10:1067‐1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alatorre C, Fernández Landó L, Yu M, et al. Treatment patterns in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists: higher adherence and persistence with dulaglutide compared with once‐weekly exenatide and liraglutide. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:953‐961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Federici MO, McQuillan J, Biricolti G, et al. Utilization patterns of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Italy: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9:789‐801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Soliqua Highlights of Prescribing Information . 2019. http://products.sanofi.us/soliqua100-33/Soliqua100-33.pdf. Accessed July 14, 2020.

- 29. Xultophy Highlights of Prescribing Information . 2019. https://www.novo-pi.com/xultophy10036.pdf. Accessed July 14, 2020.

- 30. Davies MJ, Russell‐Jones D, Barber TM, et al. Glycaemic benefit of iGlarLixi in insulin‐naive type 2 diabetes patients with high HbA1c or those with inadequate glycaemic control on two oral antihyperglycaemic drugs in the LixiLan‐O randomized trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:1967‐1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pablo Frias J, Lorenz M, Roberts M, et al. Impact of lixisenatide dose range on clinical outcomes with fixed‐ratio combination iGlarLixi in patients with type 2 diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35:689‐695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Price H, Blüher M, Prager R, et al. Use and effectiveness of a fixed‐ratio combination of insulin degludec/liraglutide (IDegLira) in a real‐world population with type 2 diabetes: results from a European, multicentre, retrospective chart review study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:954‐962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cui YM, Guo XH, Zhang DM, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of single‐ and multiple‐dose exenatide once weekly in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes. 2013;5:127‐135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fineman M, Flanagan S, Taylor K, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of exenatide extended‐release after single and multiple dosing. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011;50:65‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Iwamoto K, Nasu R, Yamamura A, et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of exenatide once weekly in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr J. 2009;56:951‐962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hunter K, Hölscher C. Drugs developed to treat diabetes, liraglutide and lixisenatide, cross the blood brain barrier and enhance neurogenesis. BMC Neurosci. 2012;13:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Umapathysivam MM, Lee MY, Jones KL, et al. Comparative effects of prolonged and intermittent stimulation of the glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptor on gastric emptying and glycemia. Diabetes. 2014;63:785‐790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jones KL, Huynh LQ, Hatzinikolas S, et al. Exenatide once weekly slows gastric emptying of solids and liquids in healthy, overweight people at steady‐state concentrations. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:788‐797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jalleh R, Pham H, Marathe CS, et al. Acute effects of lixisenatide on energy intake in healthy subjects and patients with type 2 diabetes: relationship to gastric emptying and Intragastric distribution. Nutrients. 2020;12:1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. OZEMPIC (semaglutide) injection, for subcutaneous use. Highlights of prescribing information. 2017. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/209637lbl.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2019.

- 41. Nauck MA, Petrie JR, Sesti G, et al. A phase 2, randomized, dose‐finding study of the novel once‐weekly human GLP‐1 analog, semaglutide, compared with placebo and open‐label liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:231‐241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Trautmann ME, Han J, Ruggles J. Early pharmacodynamic effects of exenatide once weekly in type 2 diabetes are independent of weight loss: a pooled analysis of patient‐level data. Clin Ther. 2016;38:1464‐1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Irvine EJ, Tack J, Crowell MD, et al. Design of treatment trials for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1469‐1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pratley R, Nauck M, Bailey T, et al; 1860‐LIRA‐DPP‐4 Study Group. One year of liraglutide treatment offers sustained and more effective glycaemic control and weight reduction compared with sitagliptin, both in combination with metformin, in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, parallel‐group, open‐label trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65:397‐407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gough SC, Bode BW, Woo VC, et al. One‐year efficacy and safety of a fixed combination of insulin degludec and liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes: results of a 26‐week extension to a 26‐week main trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:965‐973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rodbard HW, Bode BW, Harris SB, et al; Dual Action of Liraglutide and insulin degludec (DUAL) IV trial investigators. Safety and efficacy of insulin degludec/liraglutide (IDegLira) added to sulphonylurea alone or to sulphonylurea and metformin in insulin‐naïve people with type 2 diabetes: the DUAL IV trial. Diabet Med. 2017;34:189‐196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lingvay I, Pérez Manghi F, Garcia‐Hernández P, et al; DUAL V Investigators. Effect of insulin glargine up‐titration vs insulin degludec/liraglutide on glycated hemoglobin levels in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes: the DUAL V randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:898‐907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Billings LK, Doshi A, Gouet D, et al. Efficacy and safety of IDegLira versus basal‐bolus insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled on metformin and basal insulin: the DUAL VII randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1009‐1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kaku K, Yamada Y, Watada H, et al. Safety and efficacy of once‐weekly semaglutide vs additional oral antidiabetic drugs in Japanese people with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:1202‐1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Marre M, Shaw J, Brändle M, et al. Liraglutide, a once‐daily human GLP‐1 analogue, added to a sulphonylurea over 26 weeks produces greater improvements in glycaemic and weight control compared with adding rosiglitazone or placebo in subjects with type 2 diabetes (LEAD‐1 SU). Diabet Med. 2009;26:268‐278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G. et al; LEAD‐6 Study Group. Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26‐week randomised, parallel‐group, multinational, open‐label trial (LEAD‐6). Lancet. 2009;374:39‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zang L, Liu Y, Geng J, et al. Efficacy and safety of liraglutide versus sitagliptin, both in combination with metformin, in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes: a 26‐week, open‐label, randomized, active comparator clinical trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:803‐811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bailey TS, Takács R, Tinahones FJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching from sitagliptin to liraglutide in subjects with type 2 diabetes (LIRA‐SWITCH): a randomized, double‐blind, double‐dummy, active‐controlled 26‐week trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:1191‐1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rosenstock J, Reusch J, Bush M, Yang F, Stewart M, Albiglutide Study Group . Potential of albiglutide, a long‐acting GLP‐1 receptor agonist, in type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial exploring weekly, biweekly, and monthly dosing. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1880‐1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Davies MJ, Bergenstal R, Bode B, et al. Efficacy of liraglutide for weight loss among patients with type 2 diabetes: the SCALE diabetes randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:687‐699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nauck MA, Stewart MW, Perkins C, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly GLP‐1 receptor agonist albiglutide (HARMONY 2): 52 week primary endpoint results from a randomised, placebo‐controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled with diet and exercise. Diabetologia. 2016;59:266‐274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sorli C, Harashima SI, Tsoukas GM, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly semaglutide monotherapy versus placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 1): a double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group, multinational, multicentre phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:251‐260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ahrén B, Masmiquel L, Kumar H, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly semaglutide versus once‐daily sitagliptin as an add‐on to metformin, thiazolidinediones, or both, in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 2): a 56‐week, double‐blind, phase 3a, randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:341‐354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ahmann AJ, Capehorn M, Charpentier G, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly semaglutide versus exenatide ER in subjects with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 3): a 56‐week, open‐label, randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:258‐266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Aroda VR, Bain SC, Cariou B, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly semaglutide versus once‐daily insulin glargine as add‐on to metformin (with or without sulfonylureas) in insulin‐naive patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 4): a randomised, open‐label, parallel‐group, multicentre, multinational, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:355‐366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pratley RE, Aroda VR, Lingvay I. et al; SUSTAIN 7 InvestigatorsSemaglutide versus dulaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 7): a randomised, open‐label, phase 3b trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:275‐286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Example full electronic search strategy.

Table S2 Risk of bias assessment results.

Table S3 Study characteristics.

Table S4 Raw data of the outcomes used for analyses and effect estimates with CIs for each study.

Table S5 A Drug‐class random‐effects NMA model for nausea – sensitivity analysis restricted to open‐label trials.

Data Availability Statement

Qualified researchers may request access to patient level data and related study documents including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, statistical analysis plan, and dataset specifications. Patient level data will be anonymized and study documents will be redacted to protect the privacy of our trial participants. Further details on Sanofi's data sharing criteria, eligible studies, and process for requesting access can be found at: https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/