Abstract

Background

Individuals’ perceptions of their fecundity, or biological ability to bear children, have important implications for health behaviors, including infertility help-seeking and contraceptive use. Little research has examined these perceptions among US women.

Methods

This cross-sectional study examines perceptions of one’s own fecundity among US women aged 24–32 who participated in the 2009–2011 rounds of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 cohort. Analyses were limited to 3,088 women who indicated that they or their partners never received a doctor’s diagnosis regarding fertility difficulties.

Results

67% of women in the sample perceived their hypothetical chances of becoming pregnant as very likely; the remainder perceived their chances as somewhat likely (13%), not as likely (15%), or provided a “don’t know” response (6%). 26% of Black women and 19% of Latina women perceived themselves as not very likely to become pregnant, compared with only 12% among non-Black/non-Latina women (p<0.001). Only 6% of women with a college degree perceived their chances of becoming pregnant as not very likely, compared with 36% among women without a high school degree (p<0.001). Racial/ethnic and educational differences persisted in fully adjusted models. Other factors associated with fecundity self-perceptions include partnership status, parity, fertility expectations, sexual activity, prolonged exposure to pregnancy for at least 6 and/or 12 months without becoming pregnant, and self-rated health.

Conclusions

Findings indicate that self-perceived fecundity differs systematically by demographic and other characteristics. This phenomenon should be investigated further to understand how it may influence disparities in health behaviors and outcomes.

Keywords: self-perceived fecundity, infertility, fertility awareness, health beliefs

Introduction

Fecundity, or the biological capacity to have a live birth (Zegers-Hochschild et al., 2017), remains largely unknown to individuals as they move across the reproductive life course. Because there are no gold standard biomarkers of fecundity, individuals’ perceptions of their ability to become pregnant may be based on various sources, including past experience, characteristics of menstrual cycles, experiences of family members, and medical conditions associated with subfertility. Some of this information, however, may be misleading, as prior research suggests that women’s own fecundity perceptions may not be medically accurate (Polis and Zabin, 2012, Gemmill, 2018). For example, a U.S. survey of unmarried individuals aged 18–29 found that 13% of men and 19% of women believed that they were very likely to be infertile (Polis and Zabin, 2012), which is much larger than the estimated prevalence of infertility in this age group (Chandra et al., 2013).

Individuals’ perceptions of their fecundity—whether accurate or not—have important implications over the life course, including potential influences on fertility help-seeking behavior (White et al., 2006a, White et al., 2006b), contraceptive use (Gemmill, 2018, Britton et al., 2019), and the timing of family formation (Schmidt, 2008). Although the literature thus far has focused on these limited outcomes, the potential impact of fecundity perceptions may extend to other health and life course domains as well.

Despite their potential impact, there has been limited research on individuals’ perceptions of their own fecundity in the general population, including sources of information or indicators that inform these perceptions. However, as delayed childbearing (Mills et al., 2011, Gossett et al., 2013), advancement of assisted reproductive technologies (Sunderam et al., 2018, Waldby, 2015), and public conversations around infertility become more commonplace (Feasey, 2019, Sangster et al., 2015, Willson et al., 2019), individuals are increasingly exposed to messages about possible limitations to their “biological clocks” than they were decades ago. Moreover, most prior research on self-perceptions or related topics (e.g., fertility awareness) has focused on non-representative samples (e.g., college students; Whitten et al., 2013, Meissner et al., 2016) or select populations (e.g., unmarried individuals; Polis and Zabin, 2012), but given known disparities in infertility and treatment-seeking by race/ethnicity, education, and other factors (Greil et al., 2011a, Bitler and Schmidt, 2012, Craig et al., 2019, Kelley et al., 2019), it is imperative to examine self-perceptions of fecundity in the general population. Here, we make an important contribution to the literature by examining self-perceived fecundity in a nationally representative sample of US young adult women who are aged 24–32—an age range where the estimated population-level burden of impaired fecundity is relatively low compared with women over age 35 (Chandra et al., 2013)—and who have never received a medical diagnosis of infertility.

Materials and methods

Data

This cross-sectional analysis used data from the 2009–2011 rounds of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) 1997 cohort, a panel survey of 8,984 males and females in the United States who were first interviewed in 1997, when participants were aged 12 to 17 (Round 1). Subsequent rounds of the survey were conducted annually until 2011, and then biennially thereafter.

Self-perceived fecundity

In 2009 (Round 13), when participants were aged 24 to 30, the NLSY-97 administered questions concerning women’s experiences and perceptions of their biological ability to have a child. Any respondents who were not interviewed in 2009 were asked these questions in 2010 or 2011. Self-perceived fecundity was assessed via the following vignette: “The next [question is] about your biological ability to have a child. In answering [this question], please imagine that you wanted to have a child. Suppose you started to have unprotected intercourse today. What is the percent chance you would have a child within the next two years?” If a respondent stated that a child was not wanted within this time frame, the interviewer asked her to focus on her biological ability to have a child.

Most participants provided numerical responses ranging from 0–100%, with higher values indicating higher perceived probability of becoming pregnant within two years; a small proportion of women (6%) were coded with a “don’t know” response. From those who provided a numeric response, we created a three-category measure of perceived fecundity based on (1) cut points derived from the probability distribution and (2) similar constructs used in prior literature (Polis and Zabin, 2012, Gemmill, 2018). The resulting categories correspond to women perceiving themselves to be “very likely” to become pregnant within two years (75–100% chance), “somewhat likely” to (50–74% chance), or “not as likely” to (less than 50% chance). Those coded with a “don’t know” response were excluded in primary analysis, but were analyzed separately in a sensitivity analysis.

Covariates

We drew upon a range of demographic, contextual, situational, experiential, and health-related measures that were collected in the survey. All covariates were measured in the same year as the measurement of fecundity perceptions unless noted otherwise.

Demographic variables included a continuous measure of age (respondents were aged 24–32 at the time fecundity perceptions were measured), and categorical measures of race/ethnicity and education. Race/ethnicity (measured in the baseline interview in 1997) included non-Black/non-Latina, non-Latina Black, and Latina. The non-Black/non-Latina category comprised women who identify as White (93%), Asian or Pacific Islander (4%), or something else (3%). Education was coded as less than high school, high school degree, some college, and college degree or higher.

We included two measures that capture economic and health-related resources. The first is a measure of household income poverty level, which quantified respondents’ household income ratio to the federal poverty line; this ratio was coded as a five-category variable: <100%, 100–199%, 200–299%, 300–399%, 400% or more. The second measure, coded as a binary indicator variable, accounts for whether the respondent reported having any health insurance at the time of the survey (vs. none).

Contextual characteristics such as geographic location may be associated with normative differences in childbearing expectations and differential exposure to sex education content during adolescence (Gold and Nash, 2001), both of which may influence perceived fecundity. Therefore, the contextual measures we used include urban/rural residence and region of residence (Northeast, North Central, South, and West), measured in the baseline round (1997), when participants were aged 12 to 17.

The situational factors we considered pertain to women’s partnership status, sexual activity, childbearing history, and childbearing expectations. We used a combined measure of marital and cohabiting status to create four partnership categories: never married and not cohabiting; never married and cohabiting; currently married; and divorced, widowed, or separated. Respondents were also asked if they engaged in any sexual intercourse in the past year; we coded this as a binary variable (any sex vs. no sex). Parity was coded into a binary variable scored 1 for women who report at least one biological child and 0 for nulliparous women. To account for differences in motivation for pregnancy, we included a direct measure of stated expectations for future children assessed via the following question: “Altogether, how many (more) children do you expect to have?” We coded this as a binary variable indicating whether a respondent expects to have any children in the future or not.

Women who never receive a medical diagnosis of infertility may base their perceptions on biological indicators of subfertility. To examine the potential influence of this type of information, we used two different experiential measures that were available in the survey. The first measure was a binary variable indicating whether a respondent reported having multiple miscarriages or stillbirths. The second variable was derived from two questions asking if a respondent was unable to conceive a child after 6 or 12 months of unprotected intercourse in a row; we combined these responses into a three-category variable: no reported absence of conception after 6 or 12 months of unprotected sex; absence of conception after 6 months, but not 12 months; and absence of conception after 12 months. It should be noted that the last category, 12 or more months of unprotected intercourse in a row without conception, meets the criteria for a clinical diagnosis of infertility (Zegers-Hochschild, 2017).

In addition to using indicators of experienced subfertility, we relied on a general measure of self-rated health to account for a broad range of health-related experiences that might influence perceived fecundity. The categories included excellent, very good, good, and fair/poor.

Finally, we employed a measure of financial literacy to control for numeracy, or the ability to understand and use numerical information. We did this to both control for the complexities of the perceived fecundity measure used as well as for potential difficulties with quantifying probability of pregnancy (Reyna et al., 2009). We used the first question in a set of financial literacy measures that were originally designed by Lusardi and Mitchell to measure knowledge of financial concepts in social surveys (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2005, Lusardi and Mitchell, 2008). The question is: “Suppose you had $100 in a savings account and the interest rate was 2% per year. After 5 years, how much do you think you would have in the account if you left the money to grow?” Possible responses included: more than $102, exactly $102, or less than $102. Those providing incorrect responses or stating they do not know were coded as having lower numeracy.

Analytic sample

We first limited our sample to women who provided either a numerical or “don’t know” response to the perceived fecundity measure (n=3,903). We then excluded women who indicated that they or their partners had ever received a doctor’s diagnosis regarding fertility difficulties (n=224). Women who reported that they or their partners were sterilized by the time of the survey were also excluded from analysis (n=197). We further excluded women who were currently pregnant at the time of the survey (n=184), as well as women who ever reported a same-sex partner (n=85; during data collection, women who reported a same-sex partner were often assigned a value of 0% for likelihood of pregnancy in the next two years). Lastly, women with missing responses on any of the experienced subfertility measures were excluded (n=125). The final sample comprised 3,088 women.

Statistical analysis

We used multinomial logistic regression models to examine relationships between covariates and the three discrete outcomes of perceived fecundity. We estimated four separate nested models that examine the salience of three different sets of factors: demographic/contextual, situational, and experiential factors/self-rated health. (See Table 1 for list of variables in each category). Model 1 estimated the baseline relationship between demographic and contextual factors with perceived fecundity. Model 2 added situational factors to the baseline model (Model 1), while Model 3 excluded situational factors and added experiential factors and a measure of self-rated health to Model 1. The last model, Model 4, contained all measures in the same model. All four models controlled for numeracy to account for potential difficulties in responding to the perceived fecundity measure (Reyna et al., 2009).

Table 1.

Percentage of women in the sample, by selected characteristics, according to perceived likelihood of becoming pregnant and having a child within two years of unprotected intercourse.

| Perceived likelihood of future pregnancy | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | All (N=3,088) | Not very likely (N=556) | Somewhat likely (N=416) | Very likely (N=1,954) | “Don’t know” (N=162) | p-value | |||||

| Demographic and contextual factors | |||||||||||

| Age | 0.011 | ||||||||||

| 24-26 | 1366 | 44.2 | 212 | 37.3 | 194 | 45.0 | 881 | 45.3 | 79 | 47.1 | |

| 27-28 | 1238 | 39.0 | 229 | 40.0 | 168 | 40.6 | 787 | 39.0 | 54 | 32.2 | |

| 29-32 | 484 | 16.9 | 115 | 22.7 | 54 | 14.4 | 286 | 15.7 | 29 | 20.7 | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Non-Black, Non-Latina | 1570 | 72.4 | 184 | 57.6 | 175 | 64.1 | 1105 | 76.4 | 106 | 82.6 | |

| Black | 849 | 15.4 | 235 | 26.8 | 151 | 23.0 | 433 | 12.0 | 30 | 9.2 | |

| Latina | 669 | 12.1 | 137 | 15.6 | 90 | 12.9 | 416 | 11.6 | 26 | 8.3 | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| <High school | 270 | 7.1 | 101 | 16.9 | 52 | 11.0 | 104 | 4.3 | 13 | 5.4 | |

| High school | 686 | 20.9 | 186 | 32.2 | 106 | 24.3 | 362 | 17.9 | 32 | 18.0 | |

| Some college | 1199 | 37.1 | 203 | 37.2 | 163 | 36.8 | 778 | 37.6 | 55 | 32.4 | |

| ≥College degree | 915 | 35.0 | 61 | 13.6 | 94 | 27.9 | 698 | 40.3 | 62 | 44.2 | |

| Region at baseline | 0.002 | ||||||||||

| West | 691 | 21.4 | 91 | 15.0 | 73 | 17.1 | 494 | 23.7 | 33 | 20.8 | |

| Northeast | 529 | 17.9 | 8s1 | 15.2 | 64 | 17.4 | 345 | 18.2 | 39 | 22.4 | |

| North Central | 685 | 25.9 | 111 | 23.9 | 98 | 27.3 | 440 | 26.2 | 36 | 25.4 | |

| South | 1183 | 34.8 | 273 | 45.9 | 181 | 38.2 | 675 | 31.9 | 54 | 31.4 | |

| Lived in an urban area at baseline | 0.700 | ||||||||||

| No | 687 | 28.3 | 127 | 29.6 | 98 | 31.0 | 424 | 27.6 | 38 | 28.1 | |

| Yes | 2275 | 71.7 | 402 | 70.4 | 297 | 69.0 | 1454 | 72.5 | 122 | 71.9 | |

| Has health insurance | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| No | 806 | 24.9 | 184 | 31.6 | 126 | 29.5 | 454 | 22.4 | 42 | 26.1 | |

| Yes | 2281 | 75.1 | 372 | 68.5 | 290 | 70.5 | 1499 | 77.6 | 120 | 73.9 | |

| Income as a % of federal poverty level | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| <100 | 540 | 15.0 | 186 | 30.6 | 88 | 18.6 | 242 | 10.9 | 24 | 13.9 | |

| 100-199 | 514 | 18.3 | 106 | 22.7 | 85 | 22.1 | 295 | 16.4 | 28 | 21.5 | |

| 200-299 | 448 | 16.9 | 77 | 17.2 | 57 | 16.6 | 299 | 17.6 | 15 | 9.1 | |

| 300-399 | 366 | 13.6 | 48 | 10.1 | 46 | 12.9 | 255 | 14.5 | 17 | 13.0 | |

| ≥400 | 856 | 36.2 | 69 | 19.5 | 92 | 29.9 | 646 | 40.6 | 49 | 42.5 | |

| Situational factors | |||||||||||

| Partnership status | <.001 | ||||||||||

| Never-married, not cohabitating | 1336 | 39.4 | 273 | 43.2 | 214 | 47.5 | 757 | 35.5 | 92 | 55.4 | |

| Never-married, cohabitating | 555 | 18.6 | 100 | 19.6 | 55 | 13.5 | 377 | 19.8 | 23 | 13.5 | |

| Married | 973 | 34.7 | 127 | 26.2 | 116 | 30.7 | 693 | 38.3 | 37 | 24.9 | |

| Divorced/ separated/widow ed | 216 | 7.3 | 55 | 11.0 | 29 | 8.3 | 123 | 6.4 | 9 | 6.3 | |

| Parous | <.001 | ||||||||||

| No | 1391 | 50.2 | 150 | 30.0 | 194 | 54.0 | 924 | 51.1 | 123 | 82.6 | |

| Yes | 1693 | 49.8 | 405 | 70.0 | 221 | 46.1 | 1028 | 48.9 | 39 | 17.4 | |

| Expects at least one future child | <.001 | ||||||||||

| No | 793 | 24.2 | 307 | 56.8 | 90 | 20.9 | 372 | 17.8 | 24 | 17.4 | |

| Yes | 2204 | 75.8 | 244 | 43.2 | 319 | 79.1 | 1534 | 82.2 | 107 | 82.6 | |

| Any sex in last year | <.001 | ||||||||||

| No | 492 | 13.6 | 138 | 20.8 | 80 | 18.0 | 237 | 10.4 | 37 | 22.4 | |

| Yes | 2542 | 86.4 | 405 | 79.2 | 329 | 82.0 | 1692 | 89.7 | 116 | 77.7 | |

| Experiential factors and self-rated health | |||||||||||

| >1 miscarriage or stillbirth | 0.002 | ||||||||||

| No | 2984 | 96.8 | 525 | 93.8 | 400 | 95.8 | 1901 | 97.3 | 158 | 97.8 | |

| Yes | 104 | 3.2 | 31 | 6.2 | 16 | 4.3 | 53 | 2.7 | 4 | 2.2 | |

| Experience of impaired fecundity | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| None | 2145 | 70.8 | 301 | 50.1 | 258 | 60.3 | 1457 | 76.4 | 129 | 81.3 | |

| No pregnancy after 6 months, but not after 12 months, of unprotected sex | 206 | 6.7 | 43 | 8.9 | 30 | 8.2 | 128 | 6.3 | 5 | 2.2 | |

| No pregnancy after 12 months of unprotected sex | 737 | 22.6 | 212 | 41.0 | 128 | 31.5 | 369 | 17.3 | 28 | 16.5 | |

| Self-rated health | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Excellent | 673 | 23.1 | 102 | 17.6 | 73 | 17.2 | 460 | 25.2 | 38 | 25.7 | |

| Very good | 1170 | 39.4 | 156 | 29.8 | 156 | 38.9 | 786 | 41.2 | 72 | 43.6 | |

| Good | 928 | 28.7 | 202 | 34.9 | 139 | 34.3 | 551 | 26.7 | 36 | 23.8 | |

| Fair/poor | 317 | 8.8 | 96 | 17.7 | 48 | 9.6 | 157 | 6.9 | 16 | 6.9 | |

| Numeracy | |||||||||||

| Low Numeracy | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| No | 2190 | 77.6 | 351 | 68.1 | 302 | 80.1 | 1424 | 79.1 | 113 | 79.6 | |

| Yes | 669 | 22.4 | 158 | 31.9 | 82 | 19.9 | 397 | 20.9 | 32 | 20.4 | |

We conducted three sensitivity analyses. First, we excluded women who stated that they expect no children in the future. These women were excluded because the vignette used in the perceived fecundity measure may not sufficiently prime women to focus on their biological ability to have a child and may instead draw responses that are rooted in their expectations or desires (Shreffler et al., 2016), especially for women who have completed childbearing. Second, we used ordinary least squares regression to model the relationship between continuous values of perceived fecundity and measures among those who provided a numeric value of perceived fecundity. Third, we examined the likelihood of providing a “don’t know” response versus a numeric response.

We used multiple imputation by chained equations to impute missing values of covariates (Royston and White, 2011); measures with the largest number of missing values were household poverty level (12%), numeracy (7%), urban residence (4%), and expectations for future children (3%). We weighted all analyses to account for complex sampling design and cohort attrition. Because the dataset is publicly available and does not include identifying information, the study is exempt from institutional review board review.

Results

Descriptive Results

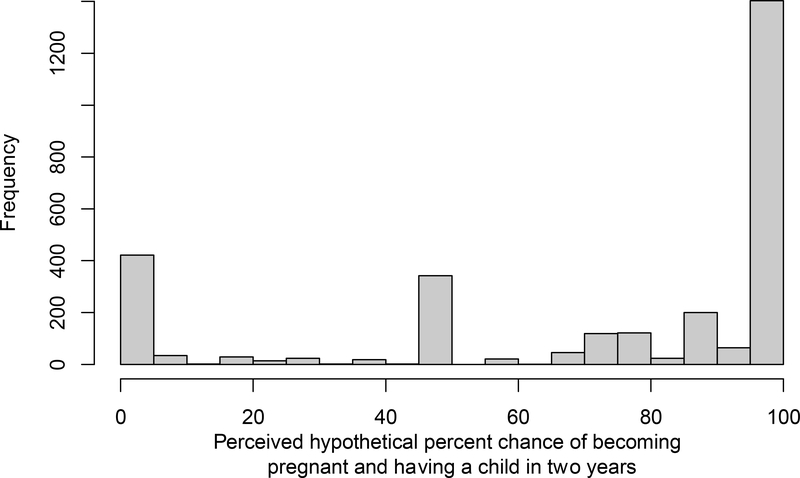

Figure 1 displays the distribution of responses assessing reported probability of becoming pregnant and having a child within two years among the 2,926 members of the sample who provided a numeric value. Around two-thirds of the sample (67%) reported that their likelihood of pregnancy was 75% or more (“very likely”), while 13% reported a probability ranging from 50 to 74% (“somewhat likely”). 15% reported that their probability of becoming pregnant was less than 50% (“not very likely”), and the remainder (6%) provided a “don’t know” response. Heaping of numeric values, whereby respondents tend to report certain values more than others nearby, is also evident in the figure; 10% said a 0% chance, another 11% said 50%, and 45% said 100%.

Figure 1.

Distribution of responses assessing respondents’ perceived hypothetical percent chance of becoming pregnant and having a child within two years of unprotected intercourse.

(Note: among the 2,926 participants providing numeric responses.)

Table 1 provides further description of responses to the self-perceived fecundity measure for the entire sample and by respondent characteristics; distributions are presented for the entire sample and separately for each of the four categories of perceived fecundity. Nearly all characteristics, with the exception of living in an urban area during adolescence, were associated with self-perceived fecundity at the bivariate level. In general, we find that more advantaged women (i.e., women with more education, higher levels of income, and health insurance) are more likely to perceive themselves as very likely to have a future pregnancy. We also find that women who report multiple miscarriages, women who have not become pregnant after 12 months of unprotected sex, and women who rate their health as fair or poor are more likely to perceive themselves as not very likely to become pregnant.

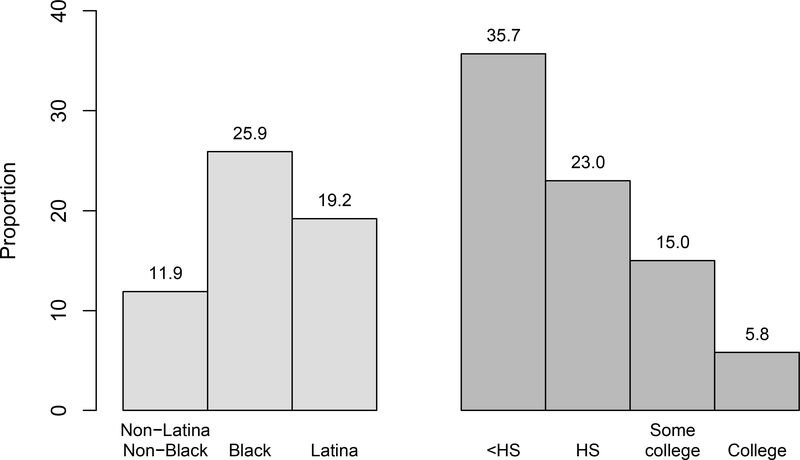

In bivariable analysis, we also find evidence that perceived fecundity is socially patterned by race/ethnicity and education. Figure 2 displays the proportion of women in each racial/ethnic and education subgroup who considered themselves to be not very likely to become pregnant. A quarter (26%) of Black women and 19% of Latina women perceived themselves as not very likely to become pregnant, compared with only 12% among non-Black/non-Latina women (p<0.001). Figure 2 also shows a marked education gradient; around a quarter to one-third of women with a high school degree or less were in the “not very likely” category, compared with only 6% of college-educated women (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Proportion of women in each category who perceived their hypothetical chance of becoming pregnant and having a child within two years of unprotected intercourse as not very likely (i.e. <50% chance).

Multivariable Results

Results from our four nested multinomial logistic regression are presented in two separate panels to improve readability. Table 2a presents relative risk ratios for women in the “not very likely” (i.e., low) category, whereas Table 2b presents relative risk ratios for those in the “somewhat likely” category; women in the “very likely” category are the reference group in both tables.

Table 2a.

Relative risk ratios and 95% CIs from multinomial regression models assessing associations between selected characteristics and perceived likelihood becoming pregnant and having a child within two years of unprotected intercourse. Results shown compare women in the “not very likely” category to those in the “very likely” category.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Demographic and contextual factors | Model 1 + situational factors | Model 1 + experiential factors and self-rated health | Full model | ||||

| Age (years) | 1.18 (1.09, 1.27) | *** | 1.12 (1.03, 1.21) | ** | 1.16 (1.08, 1.25) | *** | 1.10 (1.02, 1.20) | * |

| Race/ethnicity (ref: Non-Black, Non-Latina) | ||||||||

| Black | 2.01 (1.50, 2.70) | *** | 1.82 (1.33, 2.50) | *** | 2.00 (1.49, 2.70) | *** | 1.74 (1.26, 2.41) | *** |

| Latina | 1.50 (1.12, 1.99) | ** | 1.55 (1.13, 2.14) | ** | 1.52 (1.16, 2.00) | ** | 1.62 (1.20, 2.19) | ** |

| Education (ref: High school) | ||||||||

| <High school | 1.84 (1.22, 2.76) | ** | 1.81 (1.17, 2.79) | ** | 1.59 (1.03, 2.45) | * | 1.56 (0.97, 2.49) | |

| Some college | 0.63 (0.46, 0.85) | ** | 0.71 (0.51, 0.99) | * | 0.71 (0.53, 0.97) | * | 0.81 (0.58, 1.12) | |

| ≥College degree | 0.28 (0.19, 0.42) | *** | 0.35 (0.23, 0.54) | *** | 0.39 (0.26, 0.58) | *** | 0.47 (0.31, 0.72) | ** |

| Region at baseline (ref: West) | ||||||||

| Northeast | 1.31 (0.83, 2.07) | 1.38 (0.83, 2.30) | 1.28 (0.82, 1.99) | 1.37 (0.84, 2.24) | ||||

| North Central | 1.48 (1.02, 2.15) | * | 1.51 (1.01, 2.26) | * | 1.36 (0.95, 1.96) | 1.39 (0.94, 2.07) | ||

| South | 1.81 (1.29, 2.54) | ** | 1.80 (1.16, 2.58) | ** | 1.69 (1.20, 2.39) | ** | 1.70 (1.16, 2.48) | * |

| Lived in an urban area at baseline (ref: No) | 0.90 (0.65, 1.26) | 0.90 (0.63, 1.28) | 0.90 (0.65, 1.24) | 0.86 (0.61, 1.20) | ||||

| Has health insurance (ref: No) | 0.95 (0.73, 1.25) | 1.00 (0.75, 1.34) | 0.97 (0.73, 1.28) | 1.04 (0.76, 1.41) | ||||

| Income as a % of federal poverty level (ref: ≥400) | ||||||||

| <100 | 2.26 (1.49, 3.42) | *** | 1.49 (0.93, 2.38) | 2.41 (1.58, 3.68) | *** | 1.48 (0.92, 2.38) | ||

| 100-199 | 1.66 (1.06, 2.59) | * | 1.32 (0.81, 2.15) | 1.55 (0.99, 2.44) | 1.18 (0.72, 1.93) | |||

| 200-299 | 1.39 (0.92, 2.09) | 1.15 (0.73, 1.81) | 1.40 (0.93, 2.11) | 1.16 (0.74, 1.83) | ||||

| 300-399 | 1.13 (0.68, 1.88) | 1.07 (0.63, 1.83) | 1.13 (0.68, 1.90) | 1.06 (0.62, 1.83) | ||||

| Low Numeracy (ref: No) | 1.29 (0.95, 1.75) | 1.24 (0.91, 1.67) | 1.26 (0.92, 1.73) | 1.19 (0.87, 1.63) | ||||

| Partnership status (ref: Never-married, not cohabitating) | ||||||||

| Never-married, cohabitating | 0.88 (0.60, 1.28) | 0.73 (0.50, 1.08) | ||||||

| Married | 0.63 (0.46, 0.87) | ** | 0.53 (0.38, 0.74) | *** | ||||

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 1.03 (0.57, 1.86) | 0.90 (0.49, 1.62) | ||||||

| Parous (ref: No) | 0.88 (0.60, 1.28) | 0.82 (0.58, 1.16) | ||||||

| Expects at least one future child (ref: No) | 0.25 (0.19, 0.32) | *** | 0.24 (0.18, 0.31) | *** | ||||

| Any sex in last year (ref: No) | 0.68 (0.48, 0.98) | * | 0.49 (0.33, 0.72) | *** | ||||

| >1 miscarriage or stillbirth (ref: No) | 1.38 (0.77, 2.46) | 1.69 (0.91, 3.14) | ||||||

| Experience of impaired fecundity (ref: None) | ||||||||

| No pregnancy after 6 months, but not after 12 months, of unprotected sex | 1.78 (1.15, 2.75) | * | 2.42 (1.50, 3.90) | *** | ||||

| No pregnancy after 12 months of unprotected sex | 2.76 (2.09, 3.63) | *** | 3.58 (2.69, 4.76) | *** | ||||

| Self-rated health (ref: Excellent) | ||||||||

| Very good | 0.98 (0.71, 1.36) | 1.05 (0.76, 1.44) | ||||||

| Good | 1.26 (0.93, 1.72) | 1.18 (0.87, 1.61) | ||||||

| Fair/poor | 1.73 (1.14, 2.64) | * | 1.79 (1.16, 2.75) | ** | ||||

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Table 2b.

Relative risk ratios and 95% CIs from multinomial regression models assessing associations between selected characteristics and perceived likelihood becoming pregnant and having a child within two years of unprotected intercourse. Results shown compare women in the “somewhat likely” category to those in the “very likely” category.

| Characteristic | Model 1 Demographic and contextual factors | Model 2 Model 1 + situational factors | Model 3 Model 1 + experiential factors and self-rated health | Model 4 Full model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.01 (0.94. 1.09) | 1.03 (0.95,1.12) | 1.00 (0.93. 1.08) | 1.02 (0.94. 1.11) | ||||

| Race/ethnicity (ref: Non-Black. | ||||||||

| Non-Latina) | ||||||||

| Black | 2.03 (1.57, 2.62) | *** | 1.97(1.53,2.55) | *** | 1.97(1.51, 2.56) | *** | 1.82 (1.38, 2.39) | *** |

| Latina | 1.36 (0.93, 1.99) | 1.41 (0.96. 2.08) | 1.35(0.93. 1.96) | 1.40 (0.95, 2.05) | ||||

| Education (ref: High school) | ||||||||

| <High school | 1.78 (1.04, 3.07) | * | 2.05(1.17.3.58) | * | 1.66 (0.96. 2.88) | 1.93 (1.09.3.42) | * | |

| Some college | 0.74 (0.53, 1.04) | 0.67 (0.47, 0.94) | * | 0.81 (0.59, 1.12) | 0.74(0.53, 1.04) | |||

| ≥College degree | 0.61 (0.43. 0.88) | ** | 0.45 (0.30, 0.68) | *** | 0.75 (0.52, 1.09) | 0.57 (0.37, 0.86) | ** | |

| Region at baseline (ref: West) | ||||||||

| Northeast | 1.32(0.82, 2.12) | 1.37(0.84, 2.23) | 1.28 (0.80. 2.04) | 1.33 (0.81,2.18) | ||||

| North Central | 1.43 (0.89. 2.29) | 1.51 (0.93,2.43) | 1.35(0.84, 2.17) | 1.42 (0.87, 2.33) | ||||

| South | 1.36(0.90, 2.07) | 1.42 (0.93,2.18) | 1.32(0.87. 2.02) | 1.40 (0.90. 2.18) | ||||

| Lived in an urban area at baseline (ref: No) | 0.81 (0.59, 1.11) | 0.78 (0.56,1.10) | 0.80 (0.58, 1.10) | 0.75 (0.54, 1.06) | ||||

| Has health insurance (ref: No) | 0.81 (0.62, 1.06) | 0.88 (0.67, 1.16) | 0.82 (0.63. 1.07) | 0.92 (0.70, 1.21) | ||||

| Income as a % of federal poverty level (ref: ≥400) | ||||||||

| <100 | 1.26 (0.80, 2.00) | 1.26 (0.77, 2.07) | 1.35(0.85, 2.15) | 1.31 (0.79, 2.15) | ||||

| 100-199 | 1.31 (0.88. 1.95) | 1.41(0.92,2.16) | 1.25 (0.84. 1.87) | 1.32 (0.86, 2.02) | ||||

| 200-299 | 1.03 (0.65, 1.62) | 1.11 (0.69,1.80) | 1.04(0.66. 1.64) | 1.13 (0.70, 1.84) | ||||

| 300-399 | 1.03 (0.65, 1.64) | 1.13(0.70,1.81) | 1.02 (0.64, 1.62) | 1.12 (0.69, 1.80) | ||||

| Low Numeracy (ref: No) | 0.83(0.61, 1.11) | 0.85 (0.63, 1.15) | 0.83(0.62, 1.11) | 0.85 (0.63, 1.16) | ||||

| Partnership status (ref: Never- married, not cohabitating) | ||||||||

| Never-married, cohabitating | 0.58 (0.42, 0.80) | ** | 0.50 (0.35, 0.70) | *** | ||||

| Married | 0.86 (0.60, 1.23) | 0.77(0.53, 1.10) | ||||||

| Divorced'separated'widowed | 1.09(0.67, 1.79) | 1.01 (0.61. 1.67) | ||||||

| Parous (ref: No) | 0.54 (0.39, 0.75) | *** | 0.52 (0.38, 0.72) | *** | ||||

| Expects at least one future child (ref: No) | 0.94(0.67, 1.34) | 0.93 (0.66. 1.31) | ||||||

| Any sex in last year (ref: No) | 0.76(0.53. 1.09) | 0.63 (0.43, 0.94) | * | |||||

| >1 miscarriage or stillbirth (ref: No) | 1.22 (0.63, 2.35) | 1.37(0.69, 2.72) | ||||||

| Experience of impaired fecundity (ref: None) | ||||||||

| No pregnancy after 6 months, but not after 12 months, of unprotected sex | 1.51 (0.90. 2.54) | 1.93 (1.13,3.29) | * | |||||

| No pregnancy after 12 months of unprotected sex | 1.98(1.44,2.73) | *** | 2.40(1.68, 3.42) | *** | ||||

| Self-rated health (ref: Excellent) | ||||||||

| Very good | 1.32(0.94, 1.85) | 1.38(0.98, 1.94) | ||||||

| Good | 1.52 (1.08,2.14) | * | 1.59(1.12, 2.26) | * | ||||

| Fair/poor | 1.36 (0.82, 2.25) | 1.36(0.81,2.28) | ||||||

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Model 1 in Table 2a includes demographic and contextual measures, as well as a control variable for numeracy. Results first show that older women in the sample are more likely to report low perceived fecundity compared with younger women (adjRRR=1.18; 95% CI 1.09, 1.27). Results also show that the differences by race/ethnicity and education observed in bivariable analysis hold after adjusting for other factors. Black and Latina women are more likely to rate their fecundity as low compared with non-Black/non-Latina women (adjRRR=2.01 [95% CI 1.50, 2.70] and adjRRR=1.50 [95% CI 1.12, 1.99], respectively). Compared with women who were raised in the West, women raised in the North Central and South census regions were also more likely to rate their fecundity as low. In multivariable analyses, there were no significant relationships between living in an urban area at baseline, having health insurance, or numeracy. However, women in the lowest poverty categories had significantly higher risk of rating their fecundity as low compared to women with higher incomes.

Continuing our focus on women who report their fecundity as low (vs. “very likely” to become pregnant), we now turn to Model 2 in Table 2a, which adds situational factors to Model 1. After controlling for factors in Model 1, married women, women who expect children in the future, and women who were sexually active in the last year are all less likely to rate their fecundity as low. However, parity is not associated with the risk of reporting one is not very likely to become pregnant after adjusting for other factors. With the exception of income level, all factors associated with low perceived fecundity in the first model remain significant, although some relative risk ratios become attenuated.

The results for Model 3 consider how experiential factors are related to perceived fecundity after adjusting for respondent characteristics in Model 1. Results show that women who engage in regular, unprotected sex for at least 6 months without a pregnancy and women who rate their health as fair or poor are independently more likely to report low perceived fecundity.

Model 4 includes all measures in the same model. Results from the full model largely parallel those from Models 1–3, although there are a few differences. First, only women with a college degree are significantly different from women with a high school. Second, income level is not associated with self-perceived fecundity after adjusting for all other measures.

Parallel results displaying relative risk ratios for the likelihood of being in the “somewhat likely” category (vs. “very likely”) are shown in Table 2b. Results are somewhat similar to those observed in Table 2a. For example, in Model 4, we see similar relationships across many of the measures analyzed, although measures for age, region at baseline, and expectations for children do not significantly distinguish between women who perceived themselves as somewhat likely to become pregnant and very likely to become pregnant. We also see that while Latina women were more likely to rate their fecundity as low (vs. “very likely”) compared with non-Latina/non-Black women; Latina women did not have an elevated risk of being in the “somewhat likely” category. Last, in contrast to the results shown in Table 2a, parity is also significantly associated with being in the “somewhat likely” category.

Sensitivity Analysis

The results of our three sensitivity analyses are shown in Appendix Tables A.1–A.3. The results presented in Appendix Tables A.1a and A.1b, which are limited to women who expect children in the future, are largely similar to results from the main analyses. We also find similar patterns when we use continuous values of perceived fecundity as an outcome measure (Appendix Table A.2). Finally, in models investigating the likelihood of providing a “don’t know” response versus a numeric response (Appendix Table A.3), Black women (vs. non-Black/non-Latina women) and parous women were significantly less likely to provide a “don’t know” response.

Discussion

In the current study, we find that self-perceptions of subfertility among U.S. women aged 24–32 without a medical diagnosis of infertility are much more common than estimated prevalence data would suggest (Chandra et al., 2013). In other words, many women in this age group perceive themselves to be less fecund than they likely are. Importantly, Black and Latina women, women with less education, and women with lower incomes were independently more likely to perceive their fecundity as low compared to their counterparts across several models that adjust for a range of covariates, including experienced subfertility, self-rated health, partnership status, and intentions for future children.

Interestingly, our findings indicate that the women most likely to delay marriage and childbearing—namely White women and women with more education (Mathews and Hamilton, 2014)—are less likely to perceive themselves as subfertile compared with Black or Latina women and women with less education. Because self-perceptions of fecundity likely shape one’s willingness to delay childbearing (Schmidt, 2008), investigating the role of such perceptions on family formation and fertility behaviors, including use or interest in egg freezing technologies (Brown and Patrick, 2018, Stevenson et al., 2019), offers a promising avenue of further research.

That Black and Latina women, women with lower incomes, and women with less education were more likely to perceive their fecundity as low also merits further investigation. While these demographic groups have historically had higher total fertility rates in the U.S. compared with White women, women with higher incomes, and women with more education (Sweeney and Riley, 2014; Guzzo and Hayford 2020), prior research has shown that the burden of infertility and impaired fecundity often falls disproportionately on women of color (Craig et al., 2019; Chandra, Copen, & Stephen, 2013). Moreover, access to assisted reproductive technology does not align with need, as White, advantaged women are more likely to use such services compared with other populations (Griel et al., 2011a; Chandra et al., 2014). Thus, it might be that disparities in actual infertility and treatment seeking partly explain these patterns.

More generally, because fecundity self-perceptions have important implications for health behaviors—including infertility help-seeking and contraceptive use—further research is needed to examine how differences in self-perceptions across the population contribute to stratified reproduction and associated health disparities (Colen, 1986, Lee, 2019). Given that health differences by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status are fundamentally driven by social and structural inequalities in the US, rather than inherent biological differences (Link and Phelan, 1995, Williams and Collins, 1995, Ford and Airhihenbuwa, 2010), considering the social pathways that underlie the associations we found would be of particular interest.

We have limited knowledge of what informs self-perceptions of fecundity in the general population. Here, we show that some of these self-perceptions are likely based on past experiences with subfertility as well as self-reported general health, but we lacked other types of measures of factors that may inform perceptions. Prior research has shown, for example, that in addition to information from medical providers, women may base their assessment on proxy indicators about a family member or peer’s experience (Polis and Zabin, 2012, Sandelowski et al., 1990). Therefore, qualitative data are needed to explore the cognitive processes and inputs underlying perceptions. Such research should be conducted across a range of socioeconomic and racial/ethnic groups, since women may rely on culturally distinct schemas or cognitive structures when forming beliefs (Johnson-Hanks et al., 2011).

This study has several limitations. First, we use an unvalidated measure of self-perceived fecundity from a secondary data source. We note, however, that there are no validated measures of fecundity self-perceptions in the literature. Rather, the limited scholarship on this topic involves various measures that may capture different constructs and are likely influenced by individual notions of what it means to be “infertile” (Greil et al., 2011). Another limitation with the measure we use is that the vignette does not explicitly state sexual frequency over the hypothetical two-year period; this omission may also influence responses if women have different experiences or expectations around coital frequency and exposure to the risk of pregnancy. Additionally, the wording of the question uses the term “child,” rather than “pregnancy,” which may have also influenced women’s responses. Finally, our sample was limited to women ages 24 – 32. Including both younger and older women would have provided a broader examination of perceived fecundity, but we were limited by the available dataset. Future research should examine perceived fecundity among all women of reproductive age to be able to make meaningful comparisons across age groups.

Implications for Practice and/or Policy

Taken together, our findings suggest that there is a need for better education around fertility awareness, as well as more accurate information for women about their “actual” fecundity, including the need for medical advances that provide objective measures of reproductive potential (Kyweluk, 2020). Indeed, in taking a reproductive justice perspective, it is critical that women are armed with information throughout their reproductive life course so that they can make informed decisions about when and whether to have a child (Ross and Solinger, 2017). Basic education from providers, the internet, or within the sexual health curriculum may be helpful to close knowledge gaps and potentially align perceptions with more accurate estimates based on age and average time to become pregnant (Daniluk and Koert, 2015, Boivin et al., 2018). Given that we are continuously learning more about women’s reproductive life cycles through ongoing national surveys like the National Survey of Family Growth and different methodological approaches to measure impaired fecundity (Thoma et al. 2013), curricula need to be comprehensive and updated with validated, reputable sources (CDC 2017).

Given the dearth of research around self-perceived fecundity, its antecedents, and its sequelae, our findings are a necessary first step and call for further work in this area. Priorities for future research include: 1) improved measurement of self-perceptions, including the development of validated measures; 2) a deeper understanding of how self-perceptions are formed, how they impact behavior, and why they differ across demographic groups; and 3) identifying messaging and delivery mechanisms that can effectively target faulty inferences around fecundity. Achieving these aims would bring the sexual and reproductive health field closer to ensuring that women can meet their reproductive goals and more in line with a reproductive justice framework.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jennifer Johnson-Hanks and Joshua Goldstein for their helpful comments and support throughout this project.

Funding Statement: This work was partially funded by an NICHD grant for Interdisciplinary Training in Demography [grant number T32-HD007275].

Biographies

Alison Gemmill, PhD, MPH is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Her research aims to improve the health of women and children using a population-health and life-course perspective.

Erica Sedlander, DrPH, MPH is a Research Scientist at the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University. Her work strives to improve women’s health by using mixed methods to examine factors that affect behavior change.

Marta Bornstein, MPH is a PhD candidate in the Department of Community Health Sciences at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health. Her research focuses on sexual and reproductive health among marginalized populations in the United States and internationally.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bitler MP and Schmidt L Utilization of infertility treatments: the effects of insurance mandates. Demography. 2012; 49: 125–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boivin J, Koert E, Harris T, O’Shea L, Perryman A, Parker K, and Harrison C An experimental evaluation of the benefits and costs of providing fertility information to adolescents and emerging adults. Human Reproduction. 2018; 33: 1247–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Britton LE, Judge-Golden CP, Wolgemuth TE, Zhao X, Mor MM, Callegari S, and Borrero S Associations between perceived susceptibility to pregnancy and contraceptive use in a national sample of women veterans. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2019; 51: 211–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown E and Patrick M Time, anticipation, and the life course: egg freezing as temporarily disentangling romance and reproduction. American Sociological Review. 2018; 83: 959–982. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. Key Listings from the National Survey of Family Growth. Accessed April 24th, 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/key_statistics/i_2015-2017htm#impaired

- 6.Chandra A, Copen CE and Stephen EH. Infertility and impaired fecundity in the United States, 1982–2010: data from the National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports. 2013; 67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandra A, Copen CE, and Stephen EH. Infertility Service Use in the United States: Data From the National Survey of Family Growth, 1982–2010. National Health Statistics Reports. 2014; 73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colen S “With Respect and Feelings”: Voices of West Indian Child Care Workers in New York City Pp. 46–70 in All American Women: Lines That Divide, Ties That Bind, edited by Cole JB. New York, Free Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craig LB, Peck JD, and Janitz AE The prevalence of infertility in American Indian/Alaska Natives and other racial/ethnic groups: National Survey of Family Growth. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2019; 33: 119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniluk JC and Koert E Fertility awareness online: the efficacy of a fertility education website in increasing knowledge and changing fertility beliefs. Human Reproduction. 2015; 30: 353–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feasey R Infertility: private confessions in a public arena In: Infertility and Non-Traditional Family Building, pp. 37–86, Palgrave Macmillan, Cham; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford CL and Airhihenbuwa CO Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: toward antiracism praxis. American Journal of Public Health. 2010; 100: S30–S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gemmill A Perceived subfecundity and contraceptive use among young adult U.S. women. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2018; 50: 119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gold RB and Nash E State-level policies on sexuality, STD education. Guttmacher Policy Review. 2001; 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gossett DR, Nayak S, Bhatt S, and Bailey SC What do healthy women know about the consequences of delayed childbearing? Journal of Health Communication. 2013; 18: 118–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greil AL, McQuillan J, Shreffler KM, Johnson KM, and Slauson-Blevins KS Race-ethnicity and medical services for infertility: stratified reproduction in a population-based sample of U.S. women. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2011a; 52: 493–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greil A, McQuillan J, and Slauson-Blevins K The social construction of infertility. Sociology Compass. 2011b; 5: 736–746. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guzzo KB, and Hayford SR Pathways to parenthood in social and family contexts: Decade in review, 2020. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2020; 82:117–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson-Hanks JA, Bachrach CA, Morgan SP, and Kohler HP Understanding family change and variation: Toward a theory of conjunctural action. Dordrecht: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelley AS, Qin Y, Marsh EE, and Dupree JM Disparities in access to infertility care in the United States: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2013–16. Fertility and Sterility. 2019; 112: 562–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kyweluk MA Quantifying fertility? Direct-to-consumer ovarian reserve testing and the new (in)fertility pipeline. Social Science & Medicine. 2020; 245: 112697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee M I wish I had known sooner: stratified reproduction as a consequence of disparities in infertility awareness, diagnosis, and management. Women & Health. 2019; 59: 1185–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Link BG and Phelan J Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995; Spec: 80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lusardi A, Mitchell OS Financial literacy and planning: implications for retirement wellbeing. (Available:) http://www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/behmacro/2005-11/lusardi.pdf Date: 2005. Date accessed: March 5, 2020.

- 25.Lusardi A, Mitchell OS Planning and financial literacy: How do women fare? American Economic Review. 2008; 98: 413–417 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathews TJ and Hamilton BE First births to older women continue to rise NCHS data brief, no 152. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meissner C, Schippert C, and von Versen-Höynck F Awareness, knowledge, and perceptions of infertility, fertility assessment, and assisted reproductive technologies in the era of oocyte freezing among female and male university students. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 2016; 33: 719–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mills M, Rindfuss RR, McDonald P, te Velde E, and ESHRE Reproduction and Society Task Force. Why do people postpone parenthood? Reasons and social policy incentives. Human Reproduction Update. 2011; 17: 848–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polis CB and Zabin LS Missed Conceptions or Misconceptions: Perceived Infertility Among Unmarried Young Adults in the United States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2012; 44: 30–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reyna VF, Nelson WL, Han PK, and Dieckmann NF How numeracy influences risk comprehension and medical decision making. Psychological Bulletin. 2009; 135: 943–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross L and Solinger R Reproductive Justice: An Introduction. University of California Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Royston P and White IR Multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE): implementation in Stata. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011; 45. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandelowski M, Holditch-Davis D, and Harris BG Living the life: Explanations of infertility. Sociology of Health and Illness. 1990; 12: 195–215. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sangster SL and Lawson KL Is any press good press? The impact of media portrayals of infertility on young adults’ perceptions of infertility. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2015; 37: 1072–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidt L Risk preferences and the timing of marriage and childbearing. Demography. 2008; 45: 439–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shreffler K, Tiemeyer S, Dorius C, Spierling T, Greil A, and McQuillan J Infertility and fertility intentions, desires, and outcomes among US women. Demographic Research. 2016; 35: 1149–1168. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevenson E, Gispanski L, Fields F, Cappadora M, and Hurt M Knowledge and decision making about future fertility and oocyte cryopreservation among young women. Human Fertility. 2019; 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sunderam S, Kissin DM, Crawford SB, Folger SG, Boulet SL, Warner L, …, and Barfield WD Assisted Reproductive Technology Surveillance — United States, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Surveillance Summaries. 2018; 67: 1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sweeney MM, & Raley RK (2014). Race, Ethnicity, and the Changing Context of Childbearing in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 40(1), 539–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thoma ME, McLain AC, Louis JF, King RB, Trumble AC, Sundaram R, Buck Louis GM Prevalence of infertility in the United States as estimated by the current duration approach and a traditional constructed approach. Fertility & Sterility. 2013; 99: 1324–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waldby C ‘Banking time’: egg freezing and the negotiation of future fertility. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2015; 17: 470–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.White L, McQuillan J, Greil AL, and Johnson DR Infertility: Testing a helpseeking model. Social Science & Medicine. 2006a; 62: 1031–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White L, McQuillan J, and Greil AL Explaining disparities in treatment seeking: The case of infertility. Fertility and Sterility. 2006b; 85: 853–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whitten AN, Remes O, Sabarre KA, Khan Z, and Phillips KP Canadian university students’ perceptions of future personal infertility. Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013; 3: 561–568. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams DR and Collins C US socioeconomic and racial differences in health: patterns and explanations. Annual Review of Sociology. 1995; 21: 349–386. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willson SF, Perelman A, and Goldman KN “Age is just a number”: how celebrity-driven magazines misrepresent fertility at advanced reproductive ages. Journal of Women’s Health. 2019; 28: 1338–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, Racowsky C, de Mouzon J, Sokol R, … and van der Poel S The International Glossary on Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017. Fertility and Sterility. 2017; 108: 393–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.