Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this scoping review is to determine if and how sex and gender have been incorporated into low back pain (LBP) clinical practice guidelines (CPG), and if sex and gender terms have been used properly.

Methods

CPGs were searched on MEDLINE, Embase, NICE, TRIP and PEDro from 2010 to 2020. The inclusion criteria were English language, CGPs within physiotherapy scope of practice and for adult population with LBP of any type or duration. Three pairs of independent reviewers screened titles, abstracts and full texts. Guidelines were searched for sex/gender-related terms and recommendations were extracted. The AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II) was used to evaluate the quality of the CPGs.

Results

Thirty-six CPGs were included, of which 15 were test-positive for sex or gender terms. Only 33% (n=5) of CPGs incorporated sex or gender into diagnostic or management recommendations. Sixty percent of guidelines (n=9) only referenced sex or gender in relation to epidemiology, risk factors or prognostic data, and made no specific recommendations. Overall, there was no observable relationship between guideline quality and likeliness of integrating sex or gender terms. The majority of guidelines used sex and gender terms interchangeably, and no guidelines defined sex or gender.

Conclusion

CPGs did not consistently consider sex and gender differences in assessment, diagnosis or treatment of LBP. When it was considered, sex and gender terms were used interchangeably, and considerations were primarily regarding pregnancy. Researchers should consider the importance of including sex-based and/or gender-based recommendations into future LBP CPGs.

Keywords: back injuries, gender, lumbar spine

What is already known?

Back pain is one of the most common conditions seen by family doctors and physiotherapists.

Low back pain is highly prevalent with up to 80% of people experiencing at least one back pain episode in their lifetime.

There are known sex and gender differences in the epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of low back pain.

What are the new findings?

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) do not consistently consider sex and gender differences in the assessment, diagnosis or treatment of low back pain.

When sex or gender terms are considered, the terms are used interchangeably without regard to their strict definitions.

When CPGs did consider sex or gender, the considerations primarily related to pregnancy, which is a subterm of sex, as it does not refer to sex but rather a transient period that is specific to one sex.

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is defined as pain located in the area between the posterior lower margins of the 12th ribs and the gluteal folds, and may occur with associated lower limb pain/neurological involvement.1 2 LBP can be classified as acute (less than 6 weeks), subacute (6 to 12 weeks) or chronic (greater than 12 weeks).2 The origin of LBP is multifactorial, and is divided into non-specific LBP (NSLBP), specific, and serious pathologies.3 According to the 2017 Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study, LBP was ranked number one for years lived with disability in 1990, 2007 and 2017, with increasing rates of occurrence for all ages.4

LBP research indicates significant differences between genders regarding prevalence, degree of disability and number of comorbidities; which are all higher in individuals who identify as women.5 Despite known differences, research studies that focus on LBP inconsistently report or fail to integrate sex or gender differences into their design, analysis and conclusions,6 and it is common to observe sex and gender terms used interchangeably. This practice can not only lead to misinterpretation of results, but also impact how evidence is applied.

In 2009, the Government of Canada made changes to the Health Portfolio in order to acknowledge the differing needs of men and women in relation to health, and defined sex and gender as independent descriptors.7 Sex was defined as a set of biological attributes in humans and animals that is most often associated with physical and physiological features of an individual (ie, reproductive/sexual anatomy).7 Sex was categorised as female or male, accounting that there are many variations in the biological attributes that are sex, and how the attributes may be expressed.7 Gender was referred to as the socially constructed role, behaviour, expression or identity of an individual (ie, girls, boys, women, men, gender diverse) and influences how people perceive themselves and others.7 Gender is often seen as binary (girl/woman and boy/man) but there is great diversity in how individuals experience and express gender.7 The 2016 Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) guidelines were designed for both authors and peer reviewers, with the intention of standardising sex and gender reporting in research.8 In 2017 Tannenbaum et al6 examined how sex and gender were integrated into Canadian clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for non-communicable disease. Tannenbaum et al6 found that only 35% of guidelines made sex or gender specific recommendations, and only 25% of the studies used sex and gender terms correctly.6 Currently there are no reviews that specifically examine sex and gender considerations in LBP CPGs.

Objectives

The primary objective of this scoping review was to systematically examine if and how sex and gender was incorporated into LBP CPGs for adult populations, as it related to diagnosis, epidemiology, prognosis, risk factors and interventions. The secondary objective was to determine how sex and gender concepts have been used. The final objective was to determine if sex and gender representation was considered in the development of the guideline committee. A scoping review approach, which aims to provide a broad overview of a topic in order to identify key concepts and gaps in the literature, was deemed most appropriate due to the lack of known research on the topic of sex and gender in relation to LBP.9

Methods

The methodological framework for conducting scoping reviews, that was established by Arksey and O’Malley,10 and enhanced by Levac and colleagues,11 was used. The first five steps were followed, however, the sixth and final step, consulting with key stakeholders, was not performed, as a result of time constraints.11 This scoping review also followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for reporting guidelines for scoping reviews.12 The protocol for this scoping review was registered with OSF prior to title and abstract screening, in order to maintain transparency and reduce bias13 (10.17605/OSF.IO/7S9BD).

Inclusion criteria

All CPGs issued by a multinational committee, within the scope of physiotherapy (PT), with an adult population (18 years or older) focusing on primary LBP, were eligible for inclusion. LBP conditions that primarily related to cancer, fracture, infection, inflammatory diseases or other serious pathologies were excluded. All durations of LBP were eligible for inclusion. The methods were based off of the protocol by Oliveira et al,14 but due to the high volume of guidelines, and recognising that sex and gender were unlikely to be considered prior to 2009, the inclusion criteria was adjusted after registration.13 After full-text screen, a limit of the past 10 years was applied and only the most recent version of a CPG was included, unless different topics were addressed. Only guidelines that were published in English were eligible.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was how sex and gender had been incorporated into healthcare recommendations within CPGs. Recommendations pertaining to diagnosis, epidemiology, prognosis, risk factors and interventions were considered. The secondary outcome addressed whether or not sex and gender concepts had been used as per the definitions that were previously outlined by the Government of Canada.7 Additionally, we examined whether diversity of sex and gender were considered in the development of the guideline research committee.

Search strategy

A search for CPGs was conducted on MEDLINE via Ovid (1946 to March 8 2020), Embase (1974 to March 9 2020), National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (1999 to March 9 2020), Turning Research into Practice Medical Database (TRIP) (1997 to March 17 2020) and Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) (1999 to March 9 2020). There were no date limits applied. The following key terms were used in the search: low back pain and clinical practice guideline. A McMaster University (Ontario, Canada) Health Sciences Librarian was consulted to refine the search strategy. A comprehensive outline of the search strategy and the specific terms that were used can be found in online supplemental appendix A. This study excluded grey literature due to resource constraints. A manual search for CPGs included in the reference lists of the included studies was performed.

bmjsem-2020-000972supp001.pdf (82.7KB, pdf)

All eligible studies were imported to Covidence15 for removal of duplicates and screening. A pilot screen was completed by all reviewers for the first 10 titles/abstracts and full texts to ensure consistency. Three pairs of investigators (TR and HH, TC and MK and SR and CT) independently screened titles/abstracts and full texts. Any disagreements were discussed between the pair of reviewers, and if a consensus was not reached, a third-party investigator (LM) was consulted.

Data extraction and analysis

The same calibration process, using the first three studies, was performed for data extraction procedures. Data extraction and quality assessment was completed by the same pair of reviewers that were previously referenced. Any discrepancies were handled in the same way that was previously mentioned.

Based on the methodology of Tannenbaum et al,6 the included CPGs were first screened electronically for keywords: sex, gender, women, men, woman, man, boy, girl and pregnan*. A guideline was categorised as text-positive if it included any keywords in the main text. In this review, pregnancy was considered to be a subterm related to sex, recognising that it is a transient period of time in a female’s life, rather than a sex-specific term.

Text-positive guidelines were grouped into four categories based on how sex and gender differences were incorporated into the guidelines. Category 1 was recommended evidence-based sex-related or gender-related diagnostic approach,6 Category 2 referred to a sex-related or gender-related management approach,6 Category 3 ‘made reference to sex or gender within epidemiological data, risk factors or prognostic data, but did not make suggestions for diagnosis or clinical management’,6 and Category 4 ‘mentioned sex or gender keywords superficially’.6 In this review, the term superficial was used to describe the use of sex or gender terms without additional context or consideration as it relates to the literature or guideline recommendations. Further analysis considered the correct use of ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ terms, as defined by the Government of Canada.7 If the correct use could not be determined, guidelines were rated as ‘unclear’. Lastly, investigators examined whether the authors considered sex and gender representation in the development of each guideline committee.

Methodological quality assessment

The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II)16 tool was used to assess the quality of the CPGs.16 A calibration of the first three CPG’s was completed prior to completing the quality assessment in pairs. A threshold of 60% was used to evaluate the overall quality for the final score of each domain of the AGREE II.16 17 When ≥5 domains had a score of greater than 60%, the guideline was defined as high quality.17 When three or four of the domains had a score of greater than 60% and when less than or equal to two domains scored greater than 60%, the guidelines were defined as average quality and low quality, respectively.17 The total score of each guideline and the domains were calculated. The median scores were used to examine any superficial relationships between the quality of the guideline and the likeliness of integrating sex or gender terms.

Results

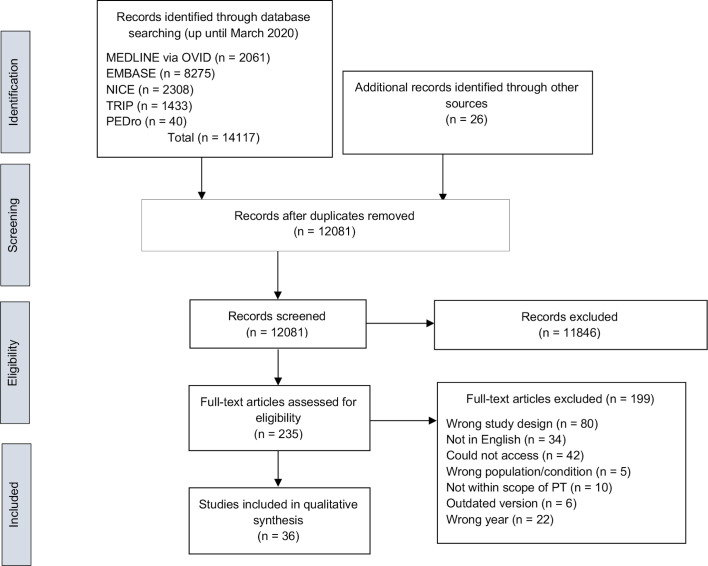

The electronic searches conducted from 2010 to March 2020 identified 14 117 studies (see figure 1 for PRISMA flow diagram). We identified 235 CPGs, from which, 199 were excluded. Reasons for exclusion included: being published before 2010 (n=22), wrong study design (n=80), not accessible in English (n=34), wrong patient population (n=5), not within the scope of physiotherapy (n=10), outdated version of CPG (n=6) or inaccessible (n=42) (online supplemental appendix B). Thirty-six CPGs were included in the review.18–53

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

bmjsem-2020-000972supp002.pdf (161.8KB, pdf)

Study characteristics

Most of the guidelines were from the USA (31%),23 26–30 38 39 43 45 48 Canada (11%)19 20 49 52 and North America (8%).25 34 35 The majority of CPGs (42%) made recommendations in relation to a combination of NSLBP and specific LBP,18–20 23 24 29 33 37 39 43 47 48 50–52 or NSLBP (39%) alone.21 22 25 27 28 30 36 42 44–46 49 53 Four CPGs (11%) focussed on specific LBP,26 32 34 35 two (5%) focussed on LBP prevention40 41 and one CPG (3%) focussed on a combination of NSLBP, specific LBP and pathological LBP.31

The majority of the guidelines (53%) made reference to all durations of LBP.18 19 21 22 24 25 27 29–31 33 38 39 42 43 49–51 53 Five CPGs (14%) made recommendations based on a combination of acute, subacute or chronic LBP,20 45 47 48 52 four (11%) referred strictly to chronic,26 28 37 44 two (5%) were in relation to acute LBP23 46 and the remaining six CPGs (17%) did not specify duration.32 34–36 40 41 There were two CPGs that focussed on diagnosis,30 39 nine focussed on management19 24 28 32 43 44 47 52 53 and four CPGs focussed on prevention.21 36 40 41 The majority of the CPGs provided information on both diagnosis and management of LBP.18 20 22 23 25–27 29 31 33–35 37 38 42 45 46 48–51

Inclusion of sex/gender terms

There were n=15 (42%) text-positive CPGs for sex and gender terms18 20 23 27 29 30 37 38 41 42 44 46 48 49 53 and n=21 (58%) text-negative CPGs19 21 22 24–26 28 31–36 39 40 43 45 47 50–52 when pregnancy-related terms were included. Table 1 depicts the categories for text-positive guidelines, and the AGREE II16 score for each text-positive and text-negative guideline. Category 1 and/or Category 2 guidelines which related to diagnosis and management, respectively, made up 33% of the text-positive guidelines. There were two CPGs that were identified as both Category 1 and Category 2,23 48 and three guidelines that were identified as only Category 2.44 53 Nine CPGs were identified as Category 3 (60%)20 27 29 30 37 38 41 42 46 making reference to sex or gender terms in relation to epidemiology, prognosis or risk factors. There was only one Category 4 guideline, which superficially mentioned sex or gender terms49 without providing further context.

Table 1.

Sex and gender text-positive clinical practice guidelines and text-negative clinical practice guidelines with the corresponding AGREE II score

| Author | Organisation and country | Title | OA* | Quality† |

| Category 1 and 2‡ | ||||

| Chiodo et al 201023 | University of Michigan Health System (USA) | Acute low back pain: guidelines for clinical care (with consumer summary) | 4.5 | Low |

| Thorson et al 201848 | Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (USA) | Low back pain, adult acute and subacute | 5.5 | Average |

| Category 2§ | ||||

| Arvin et al 201618 | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) | Low back pain and sciatica in over 16 s: assessment and management - NICE guideline | 5.5 | High |

| Rached et al 201344 | Brazilian Association of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (Brazil) | Chronic non-specific low back pain: rehabilitation | 3.5 | Average |

| Zhao et al 201653 | Institute of Acupuncture and Moxibustion (China) | Clinical practice guidelines of using acupuncture for low back pain | 2.5 | Low |

| Category 3¶ | ||||

| Bussières et al 201820 | Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative (Canada) | Spinal manipulative therapy and other conservative treatments for low back pain: a guideline from the Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative (with consumer summary) | 6 | High |

| Delitto et al 201227 | American Physical Therapy Association (USA) | Low back pain clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association (with consumer summary) | 4.5 | Low |

| Hegmann et al 201629 | American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (USA) | Low back disorders | 4.5 | Low |

| Hegmann et al 201930 | American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (USA) | Diagnostic tests for low back disorders | 5 | Average |

| Lee et al 201337 | British Pain Society (UK) | Low back and radicular pain: a pathway for care developed by the British Pain Society. | 3.5 | Low |

| Pangarkar et al 201938 | US Department of Veteran Affairs / US Department of Defence (USA) | VA/DoD clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and treatment of low back pain | 4 | Average |

| Petit et al 201641 | French Society of Occupational Medicine (France) | French good practice guidelines for management of the risk of low back pain among workers exposed to manual material handling: hierarchical strategy of risk assessment of work situations | 2.5 | Low |

| Picelli et al 201642 | The Italian Conference on Pain in Neurorehabilitation (Italy) | Headache, low back pain, other nociceptive and mixed pain conditions in neurorehabilitation. Evidence and recommendations from the Italian Consensus Conference on Pain in Neurorehabilitation | 4 | Average |

| Staal et al 201346 | Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (Netherlands) | KNGF clinical practice guideline for physical therapy in patients with low back pain | 3 | Average |

| Category 4** | ||||

| LBP working group toward optimised practice 2017 | LBP working group toward optimised practice (Canada) | Evidence-informed primary care management of low back pain | 3.5 | Low |

| Text-negative guidelines†† | ||||

| Brosseau et al 201219 | Ottawa Methods Group (Canada) | Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on therapeutic massage for low back pain | 4 | Low |

| Cheng et al 201221 | Guideline Development Working Group (Hong Kong) | Evidence-based guideline on prevention and management of low back pain in working population in primary care | 4 | Low |

| Chenot et al 201722 | National Programme for Disease Management Guidelines (Germany) | Clinical practice guideline: non-specific low back pain | 3 | Low |

| Chou et al 201824 | Global Spine Care Initiative (Global) | The Global Spine Care Initiative: applying evidence-based guidelines on the non-invasive management of back and neck pain to low-income and middle-income communities | 4 | Low |

| Chutkan et al 202025 | North American Spine Society (North America) | Evidence-based clinical guidelines for multidisciplinary spine care: diagnosis and treatment of low back pain | 5 | Average |

| Deer et al 201926 | Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Consensus Group (USA) | The MIST guidelines: the lumbar spinal stenosis consensus group guidelines for minimally invasive spine treatment | 3 | Low |

| Globe et al 201628 | Council on Chiropractic Guidelines and Practice Parameters (USA) | Clinical practice guideline: chiropractic care for low back pain | 5.5 | High |

| Hussein et al 201631 | Malaysian Association for the Study of Pain, Spine Society Malaysia (Malaysia) | The Malaysian low back pain management guidelines | 2.5 | Low |

| Jun et al 201732 | Korean Institute of Oriental Medicine (Korea) | Korean medicine clinical practice guideline for lumbar herniated intervertebral disc in adults: an evidence-based approach | 4 | Low |

| Kassolik et al 201733 | Polish Society of Physiotherapy, the Polish Society of Family Medicine and the College of Family Physicians (Poland) | Recommendations of the polish society of physiotherapy, the Polish society of family medicine and the college of family physicians in Poland in the field of physiotherapy of back pain syndromes in primary healthcare | 4 | Average |

| Kreiner et al 201335 | North American Spine Society (North America) | An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis (update) | 4 | Low |

| Kreiner et al 201434 | North American Spine Society (North America) | An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy | 4 | Low |

| Kuijer et al 201436 | Dutch Government Occupational Health and Safety (Netherlands) | An evidence-based multidisciplinary practice guideline to reduce the workload due to lifting for preventing work-related low back pain | 4.5 | Average |

| Patel et al 201639 | American College of Radiology (ACR) (USA) | ACR appropriateness criteria low back pain | 4 | Average |

| Petit et al 201640 | French Society of Occupational Medicine (France) | Pre-employment examination for low back risk in workers exposed to manual handling of loads: French guidelines | 3 | Low |

| Qaseem et al 201743 | American College of Physicians (USA) | Non-invasive treatments for acute, subacute and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians | 5 | Average |

| Sparks et al 201745 | Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of Washington (USA) | Non-specific back pain guideline | 3.5 | Low |

| Stochkendahl et al 201747 | Danish Health Authority (Denmark) | National clinical guidelines for non-surgical treatment of patients with recent onset low back pain or lumbar radiculopathy | 4.5 | Average |

| Valdecañas 201750 | Philippine Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine (Philippines) | Clinical practice guidelines on the diagnosis and management of low back pain | 4 | Low |

| Van Wambeke et al 201751 | Belgian Healthcare Knowledge Centre (Belgium) | Low back pain and radicular pain: assessment and management | 6 | High |

| Wong et al 201752 | Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration (Canada) | Clinical practice guidelines for the non-invasive management of low back pain: a systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management Collaboration | 3.5 | Low |

*Overall assessment score.

†High quality was defined when 5 or more domains scored >60%, average quality when 3 or 4 domains scored > 60% and low quality when ≤ 2 domains scored >60%.

‡Recommended evidence-based sex-related or gender-related diagnostic or management approach.

§Recommended evidence-based sex-related or gender-related management approach.

¶Made reference to sex or gender within epidemiological data, risk factors or prognostic data, but did not make suggestions for diagnosis or clinical management.

**Mentioned sex or gender keywords superficially.

††Did not mention sex or gender terms in text.

AGREE II, Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II; DoD, Department of Defence; LBP, low back pain; VA, Veteran Affairs.

When pregnancy-related terms were excluded from the results, the lack of sex and gender integration was more pronounced (online supplemental appendix C). No guidelines made reference to sex or gender considerations in relation to LBP diagnosis, and only one guideline considered gender differences in management.23 Eight guidelines made reference to sex or gender terms in relation to epidemiology, prognosis or risk factors.20 27 29 30 37 41 42 46 These results further depict the lack of sex or gender considerations beyond pregnancy.

bmjsem-2020-000972supp003.pdf (83.3KB, pdf)

Sex/gender keywords

Examples of paraphrased quotes retrieved from all of the text-positive CPGs were depicted in table 2. The quotes were organised by their respective categories (1 to 4), based off of the methodology by Tannenbaum et al.6 Within Category 1 there were two guidelines that provided recommendations for contraindications against imaging techniques for pregnancy.23 48 One of the guidelines gave an additional Category 1 recommendation with regards to clinical examination.48 For example, flexion and extension movements were contraindicated during clinical exams of patients who were pregnant.48 Within Category 2, there were five studies that gave specific management recommendations in regard to pregnancy considerations.18 23 44 48 53 Pregnancy-specific recommendations included rehabilitation strategies, contraindications to electrotherapy, precautions to acupuncture and precautions or contraindications for certain medications.18 23 44 48 53 There was only one guideline within Category 2 that provided a management recommendation that was not specific to pregnancy.23 The recommendation made reference to avoiding trunk extension/flexion exercises in women at risk for osteoporosis.23 The majority of the Category 1 and Category 2 recommendations were for specific considerations in pregnancy.

Table 2.

Summary of the use of sex and gender terms in relation to the respective category

| Author / national body | Paraphrased quote from guideline |

| Category 1: Recommends evidence-based sex-related or gender-related diagnostic approach | |

| Chiodo et al 201023 | IMAGING: X-rays, CT scans and bone scans are contraindicated during pregnancy. Consultation with a radiologist is strongly advised when considering MRI scanning during pregnancy. |

| University of Michigan Health System (USA) | |

| Thorson et al 201848 | CLINICAL EXAM: The physical examination is similar to non-pregnant patients with low back pain, although lumbar flexion will be limited as the pregnancy progresses. |

| Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (USA) | IMAGING: Lumbar radiographs are routinely avoided during pregnancy due to concern for fetal health. MRI is the test of choice for severe pregnancy-related low back pain. |

| Category 2: Recommends evidence-based sex-related or gender-related management approach | |

| Arvin et al 201618 | RADIOFREQUENCY DENERVATION: The Guideline Development Group (GDG) agreed that this recommendation (indications for referral for appropriateness of radiofrequency denervation) would equally apply for pregnant women and this should be considered on a case by case basis. |

| National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) | MEDICATION: The Guideline Development Group (GDG) agreed that British National Formulary (BNF) guidance should be followed for all pharmacological recommendations, including considerations for pregnant women, and therefore did not consider that separate recommendations were required for pregnant women. |

| Chiodo et al 201023 | REHABILITATION: In older women or persons at risk for osteoporosis, trunk extension exercises are preventive, while trunk flexion exercises may increase the risk of osteoporotic fractures. Pregnant women with back pain may want to discuss with their obstetrical care provider different positions, strategies and methods of pain relief. This may include anaesthesia consultation (for labour and delivery) or referral to hospital or community based prophylactic back classes specifically designed for pregnancy. |

| University of Michigan Health System (USA) | MEDICATION: Medications are limited and should be appropriate for a pregnant woman. |

| Rached et al 201344 | ULTRASOUND: Therapeutic ultrasound is contraindicated in areas, such as in the eyeball, pregnant uterus, plastic endoprosthesis components, methacrylate and the heart. |

| Brazilian Association of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (Brazil) | ELECTROTHERAPY: Percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (acupuncture and electrical stimulation) is contraindicated in pacemaker users, individuals with epilepsy, heart problems, cognitive impairments and during the first 3 months of pregnancy, especially in the lumbar and abdominal areas. |

| Thorson et al 201848 | EPIDURAL STERIOD INJECTIONS: Pregnancy is a contraindication due to the use of fluoroscopy. |

| Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (USA) | |

| Zhao et al 201653 | COMPLEMENTARY MED: Acupotomy is applied very cautiously for women during menstruation or pregnancy. Moxibustion should be applied very cautiously for pregnant patients or patients with sensory impairment. |

| Institute of Acupuncture and Moxibustion (China) | |

| Category 3: Referred to sex or gender within epidemiology data, risk factors or prognostic data, but did not make recommendations | |

| Bussières et al 201820 | CARE SEEKING BEHAVIOURS: Most people with low-back pain consult a health provider for this issue. It is more common for women to seek care along with individuals with previous low back pain, poor general health and more disabling or more painful episodes. |

| Canadian Chiropractic Guideline Initiative (Canada) | |

| Delitto et al 201227 | EPIDEMIOLOGY: Low back pain (LBP) prevalence appears to vary based on factors like sex, age, education and occupation; with women having a higher prevalence than men. |

| American Physical Therapy Association (USA) | RISK FACTORS: Risk factors for LBP that relate to the individual include genetics, gender, age, body build, strength and flexibility. Women may have almost three times the risk of back pain as men. |

| Hegmann et al 201629 | RISK FACTORS: The factors that predict unresponsiveness to epidural glucocorticosteroid injections include potential sex differences. Male gender is at higher risk for ankylosing spondylitis. |

| American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (USA) | Risk factors for spondylolysis include increasing age and male gender. Risk factors for degenerative spondylolisthesis include age and female gender. |

| Hegmann et al 2019 30 | RISK FACTORS: Epidemiological studies suggest the risk factors for degenerative back conditions include ageing, male sex, obesity, heredity and systemic arthrosis. Risk factors for spondylolysis include increasing age and being of male sex. Risk factors for degenerative spondylolisthesis include age and being of female sex. |

| American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (USA) | |

| Lee et al 201337 | EPIDEMIOLOGY: The number of people suffering with chronic pain in England varies between 14% of the youngest men and 59% of the oldest women (mean 31% men, 37% women). |

| British Pain Society (UK) | |

| Pangarkar et al 201938 | EPIDEMIOLOGY: More than two-thirds of pregnant women experience LBP and symptoms typically increase with advancing pregnancy. |

| US Department of Veteran Affairs / US Department of Defence (USA) | |

| Petit et al 201640 | EPIDEMIOLOGY: Half of male unskilled workers and one-third of female unskilled workers are exposed to manual material handling. |

| French Society of Occupational Medicine (France) | |

| Picelli et al 201642 | RISK FACTOR: Demographic risk factors for the onset and the clinical course of LBP include age, gender, body mass index (BMI) and educational level. A stronger correlation between LBP and a high BMI (>30) has been reported in women than in men. |

| The Italian Conference on Pain in Neurorehabilitation (Italy) | |

| Staal et al 201346 | RED FLAGS: (Ankylosing spondylitis) Onset of low back pain before age 20 years, male sex, iridocyclitis, history of unexplained peripheral arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease, pain mostly nocturnal, morning stiffness >1 hour, less pain when lying down or exercising, good response to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (Netherlands) | |

| Category 4: Mentioned sex or gender keywords superficially | |

| LBP working group toward optimised practice 2017 | EXCLUSION CRITERIA: Pregnant women |

| LBP working group toward optimised practice (Canada) | |

Category 3 CPGs were most prevalent (n=9) and integrated sex and gender terms most frequently.20 27 29 30 37 38 41 42 46 Category 3 CPGs integrated sex or gender terms into epidemiology, risk factors and care-seeking behaviours.20 27 29 30 37 38 41 42 46 CPGs reported that women tend to have a higher prevalence of LBP and are more likely to seek care for LBP20 27 37 42 One pregnancy-specific reference was made within Category 3, stating that two-thirds of pregnant women experience LBP.38 Category 3 was the only category that referenced male sex or gender, stating that men, more often than women, experience LBP as a result of manual material handling.41 Men also have a higher risk of developing ankylosing spondylitis and spondylolysis.29 30 46 The only CPG that was considered Category 4, referenced pregnancy within the exclusion criteria.49

Appropriateness of sex/gender use

None of the identified text-positive CPGs provided a definition of sex or gender within the guideline,18 20 23 27 30 37 38 41 42 44 46 48 49 53 and only three CPGs30 42 46 had appropriate use of the terms according to the Government of Canada.7 Two CPGs did not contain enough information to determine if the terms were used properly.27 41 The remaining 10 CPGs had inappropriate use of sex and gender terms, for example, using gender terms when relating to biological attributes.18 20 23 29 37 38 44 48 49 53 Only one CPG considered sex and gender representation in the formation of the guideline committee.39

Methodological quality assessment

The total score for each domain of the AGREE II16 as well as the final overall quality was determined for each guideline (online supplemental appendix D). Of the 36 evaluated guidelines, 418 19 28 51 were high quality (11%), 1225 30 33 36 38 39 42–44 46–48 were average quality (33%) and 2019 21–24 26 27 29 31 32 34 35 37 40 41 45 49 50 52 53 were low quality (56%). Only two guidelines20 51 reached an acceptable (≥60%) score in all six AGREE II16 domains. The remaining CPGs had at least one domain with a low score (<60%). Of all domains, Domain 4 (‘Clarity of Presentation’) had the highest mean quality score 79% and Domain 5 (‘Applicability’) had the lowest mean quality score 22%. The overall median AGREE II16 score of all CPGs, as well as text-positive CPGs, was 4 with an IQR of 1. There was no observable relationship between the quality of the guideline and likeliness of integrating sex or gender terms. There were five guidelines22 29 30 37 47 for which the referenced methodology or appendices were not in English, thus the scores may not be a true representation of their methodological quality.16

bmjsem-2020-000972supp004.pdf (80.3KB, pdf)

Discussion

Major findings

Overall, the CPGs identified in this scoping review had poor integration of sex and gender considerations, and the majority of CPGs did not mention sex or gender terms. When sex or gender terms were mentioned, they were primarily in relation to epidemiology, risk factors or prognostic data. There were few CPGs that integrated any sex or gender differences into their recommendations regarding diagnosis or treatment of LBP. The majority of the time, recommendations were for specific considerations in pregnancy.18 23 44 48 53 The majority of guidelines used inappropriate terms when referring to either sex or gender. Often, sex and gender terms were used interchangeably, and there was very limited separation between the use of the biological sex terms and social gender terms. Only one guideline committee acknowledged if diversity of sex and gender was considered in the development of the committee.39 No CPG provided a definition of sex or gender within the guideline.

The findings of this review had both consistencies and inconsistencies to a similar study conducted by Tannenbaum et al.6 Tannenbaum et al6 found that 67% of the included CPGs were text-positive for sex or gender terms. Thirty-five per cent of text-positive CPGs fell under Category 1 and Category 2 recommendations (reported screening, diagnosis or management considerations specific to sex or gender), and the majority of CPGs (41%) made reference to sex or gender considerations in epidemiological or risk factors. It is clear that this scoping review had a much lower text-positive response than Tannenbaum et al,6 with only 42% of CPGs being text-positive. The inconstancies found between the number of text-positive guidelines may be due to differences in study methodology. Tannenbaum et al6 only included Canadian studies, whereas this review was expanded to international guidelines. Research funders in Canada, such as the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR), are a driving force behind sex and gender integration in Canadian research.54 Canadian guidelines may be more likely to integrate sex and gender considerations into research, compared with other countries, as a result of the CIHR.

Tannenbaum et al6 excluded studies that had key words specific to pregnancy, whereas this review included pregnancy as a sex term in order to be more inclusive. The majority of Category 1 and Category 2 recommendations in this review were related to pregnancy. When pregnancy terms were omitted, there were no guidelines that made reference to diagnosis, and only one guideline that referred to management. Sex and gender considerations need to go beyond pregnancy, teratogenicity or breastfeeding, and consider more complex interactions such as specific and non-specific LBP. Future studies should integrate sex and gender terms in relation to all age milestones, rather than solely focussing on transient periods, such us pregnancy. This approach to sex and gender integration would make recommendations applicable to a broader population.

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review used rigorous methodology to ensure low risk of bias and quality of reporting. The methodological framework for scoping reviews by Arksey and O’Malley,10 and Levac et al11 was used. The PRISMA guidelines for reporting were also followed.12 The study protocol was registered with OSF prior to title and abstract screening to ensure transparency of the process and reduce potential bias.13 A comprehensive search strategy was used, which was developed in partnership with a librarian. In addition, the AGREE II16 was used to evaluate the quality of the included CPGs.16

Restricting the language to English only was a limitation of this review. This review only considered CPGs and excluded primary literature. It is possible that our results do not represent the current state of sex-based and gender-based primary research pertaining to LBP. Another limitation was limiting the inclusion criteria to the past 10 years. Earlier CPGs that integrated sex and gender terms may have been excluded by this narrow timeline. A 10-year cut-off was chosen because government bodies and experts began recognising the importance of sex and gender considerations in the literature after 2009.8 54 We recognised that these changes would take a year or more to integrate into research, therefore, before 2010, it was unlikely that CPGs integrated sex or gender terms.

Conclusion

This review provided insight on the current use of sex and gender terms in CPGs related to LBP. Integration of sex and gender considerations has the potential to guide future clinical practice and research, specifically regarding differences in the diagnosis, prognosis and management of LBP. This review is intended to be eye-opening for LBP researchers regarding the fact that sex and gender are not being integrated in current CPGs. The use of guides, such as the SAGER guidelines, should become a priority in the future.8 This review highlights that there are known sex and gender differences in management, epidemiology, risk factors and care-seeking behaviours in LBP, which should be considered during physiotherapy practice. Future research should consider examining both the inclusion and appropriateness of the use of a larger spectrum of gender specific terms (ie, non-binary), as current knowledge on this area of gender integration and research regarding LBP is limited. Clinicians should educate themselves on the differences between sex/gender and be cautious when using LBP recommendations from current CPGs.

Footnotes

Twitter: @gazzimacedo

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it first published. The provenance and peer review statement has been included.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Study design, data collection and analysis were performed by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Dionne CE, Dunn KM, Croft PR, et al. A consensus approach toward the standardization of back pain definitions for use in prevalence studies. Spine 2008;33:95–103. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e7f94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton AK, Balagué F, Cardon G, et al. Chapter 2. European guidelines for prevention in low back pain : November 2004. Eur Spine J 2006;15 Suppl 2:s136–68. 10.1007/s00586-006-1070-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet 2018;391:2356–67. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30480-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 2018;392:1789–858. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fehrmann E, Kotulla S, Fischer L, et al. The impact of age and gender on the ICF-based assessment of chronic low back pain. Disabil Rehabil 2019;41:1190–9. 10.1080/09638288.2018.1424950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tannenbaum C, Clow B, Haworth-Brockman M, et al. Sex and gender considerations in Canadian clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. CMAJ Open 2017;5:E66–73. 10.9778/cmajo.20160051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Government of Canada . Health Portfolio sex and gender-based analysis policy. in: Gov. can, 2017. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/transparency/corporate-management-reporting/heath-portfolio-sex-gender-based-analysis-policy.html

- 8.Heidari S, Babor TF, De Castro P, et al. Sex and gender equity in research: rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Res Integr Peer Rev 2016;1:2. 10.1186/s41073-016-0007-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daudt HML, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team's experience with Arksey and O'Malley's framework. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:48. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rathbone T, Cimek T, Riazi S. Protocol for sex and gender considerations in low back pain clinical practice guidelines: a scoping review 2020 10.17605/OSF.IO/7S9BD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. Eur Spine J 2018;27:2791–803. 10.1007/s00586-018-5673-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veritas Health Innovation . Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. Agree II: advancing Guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Can Med Assoc J 2010;182:E839–42. 10.1503/cmaj.090449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doniselli FM, Zanardo M, Manfrè L, et al. A critical appraisal of the quality of low back pain practice guidelines using the agree II tool and comparison with previous evaluations: a EuroAIM initiative. Eur Spine J 2018;27:2781–90. 10.1007/s00586-018-5763-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arvin B, Bernstein I, Blowey S. Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management - NICE guideline, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brosseau L, Wells GA, Poitras S, et al. Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on therapeutic massage for low back pain. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2012;16:424–55. 10.1016/j.jbmt.2012.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bussières AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F, et al. Spinal manipulative therapy and other conservative treatments for low back pain: a guideline from the Canadian chiropractic guideline initiative. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2018;41:265–93. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2017.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng L, KKS L, Lam WK. Evidence-Based guideline on prevention and management of low back pain in working population in primary care. Xianggang Uankeyixueyuan Yuekan Hong Kong Pract 2012;34:106–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chenot J, Greitemann B, Kladny B. Non-Specific low back pain. Dtsch Arzteblatt Int 2017;114:883–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiodo AE, Alvarez DJ, Graziano GP. Acute low back pain: guidelines for clinical care [with consumer summary], 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chou R, Côté P, Randhawa K, et al. The global spine care initiative: applying evidence-based guidelines on the non-invasive management of back and neck pain to low- and middle-income communities. Eur Spine J 2018;27:851–60. 10.1007/s00586-017-5433-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chutkan NB, Lipson AC, Lisi AJ. Evidence-Based clinical guidelines for multidisciplinary spine care: diagnosis and treatment of low back pain 2020.

- 26.Deer TR, Grider JS, Pope JE, et al. The mist guidelines: the lumbar spinal stenosis consensus group guidelines for minimally invasive spine treatment. Pain Pract 2019;19:250–74. 10.1111/papr.12744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delitto A, George SZ, Dillen LV. Low back pain clinical practice guidelines linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association [with consumer summary]. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2012;42:A1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Globe G, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C, et al. Clinical practice guideline: chiropractic care for low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2016;39:1–22. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2015.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hegmann KT, Travis R, Belcourt R. Low back disorders, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hegmann KT, Travis R, Belcourt RM, et al. Diagnostic tests for low back disorders. J Occup Environ Med 2019;61:e155–68. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hussein AMM, Singh D, Mansor M. The Malaysian low back pain management guidelines, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jun JH, Cha Y, Lee JA, et al. Korean medicine clinical practice guideline for lumbar herniated intervertebral disc in adults: an evidence based approach. Eur J Integr Med 2017;9:18–26. 10.1016/j.eujim.2017.01.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kassolik K, Rajkowska-Labon E, Tomasik T, et al. Recommendations of the Polish Society of physiotherapy, the Polish Society of family medicine and the College of family physicians in Poland in the field of physiotherapy of back pain syndromes in primary health care. Fmpcr 2017;3:323–34. 10.5114/fmpcr.2017.69299 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kreiner DS, Hwang SW, Easa JE, et al. An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy. Spine J 2014;14:180–91. 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kreiner DS, Shaffer WO, Baisden JL, et al. An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis (update). Spine J 2013;13:734–43. 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.11.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuijer PPF, Verbeek JH, Visser B, et al. An evidence-based multidisciplinary practice guideline to reduce the workload due to lifting for preventing work-related low back pain. Ann Occup Environ Med 2014;26:16. 10.1186/2052-4374-26-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee J, Gupta S, Price C, et al. Low back and radicular pain: a pathway for care developed by the British pain Society. Br J Anaesth 2013;111:112–20. 10.1093/bja/aet172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pangarkar SS, Kang DG, Sandbrink F, et al. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:2620–9. 10.1007/s11606-019-05086-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel ND, Broderick DF, Burns J, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria Low Back Pain. J Am Coll Radiol 2016;13:1069–78. 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petit A, Rousseau S, Huez JF, et al. Pre-Employment examination for low back risk in workers exposed to manual handling of loads: French guidelines. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2016;89:1–6. 10.1007/s00420-015-1040-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petit A, Mairiaux P, Desarmenien A, et al. French good practice guidelines for management of the risk of low back pain among workers exposed to manual material handling: hierarchical strategy of risk assessment of work situations. Work 2016;53:845–50. 10.3233/WOR-162258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Picelli A, Buzzi MG, Cisari C, et al. Headache, low back pain, other nociceptive and mixed pain conditions in neurorehabilitation. Evidence and recommendations from the Italian consensus conference on pain in neurorehabilitation. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2016;52:867–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:514–30. 10.7326/M16-2367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rached R, da RCDP, Alfieri FM. Lombalgia inespecífica crônica: reabilitação. Rev Assoc Médica Bras 2013;59:536–53. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sparks A, Cohen A, Adjao S. Back pain. Kais perm clin Guidel, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Staal J, Hendriks E, Heijmans M. KNGF clinical practice guideline for physical therapy in patients with low back pain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stochkendahl MJ, Kjaer P, Hartvigsen J, et al. National clinical guidelines for non-surgical treatment of patients with recent onset low back pain or lumbar radiculopathy. Eur Spine J 2018;27:60–75. 10.1007/s00586-017-5099-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thorson D, Campbell R, Massey M. Low back pain, adult acute and subacute. insT clin Syst Improv, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Toward Optimized Practice (TOP) Low Back Pain Working Group . Evidence-Informed primary care management of low back pain: clinical practice guideline. toward optimized practice, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valdecañas C, Ephraim D. Clinical practice guidelines on the diagnosis and management of low back pain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Wambeke P, Desomer A, Ailliet L. Clinical guideline on low back pain and radicular pain. Tijdschr Voor Geneeskd 2017;73:1182–95. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong JJ, Côté P, Sutton DA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the noninvasive management of low back pain: a systematic review by the Ontario protocol for traffic injury management (optima) collaboration. Eur J Pain 2017;21:201–16. 10.1002/ejp.931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao H, LIU B-yan, LIU Z-shun, et al. Clinical practice guidelines of using acupuncture for low back pain. World J Acupunct Moxibustion 2016;26:1–13. 10.1016/S1003-5257(17)30016-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Government of Canada CI of HR . Sex, gender and health research. in: can. insT. health Res 2019. [Epub ahead of print: 4 Jul 2020] https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50833.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjsem-2020-000972supp001.pdf (82.7KB, pdf)

bmjsem-2020-000972supp002.pdf (161.8KB, pdf)

bmjsem-2020-000972supp003.pdf (83.3KB, pdf)

bmjsem-2020-000972supp004.pdf (80.3KB, pdf)