Abstract

Background

The Astana Declaration on Primary Health Care reiterated that PHC is a cornerstone of a sustainable health system for universal health coverage (UHC) and health-related Sustainable Development Goals. It called for governments to give high priority to PHC in partnership with their public and private sector organisations and other stakeholders. Each country has a unique path towards UHC, and different models for public-private partnerships (PPPs) are possible. The goal of this paper is to examine evidence on the use of PPPs in the provision of PHC services, reported challenges and recommendations.

Methods

We systematically reviewed peer-reviewed studies in six databases (ScienceDirect, Ovid Medline, PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Scopus) and supplemented it by the search of grey literature. PRISMA reporting guidelines were followed.

Results

Sixty-one studies were included in the final review. Results showed that most PPPs projects were conducted to increase access and to facilitate the provision of prevention and treatment services (i.e., tuberculosis, education and health promotion, malaria, and HIV/AIDS services) for certain target groups. Most projects reported challenges of providing PHC via PPPs in the starting and implementation phases. The reported challenges and recommendations on how to overcome them related to education, management, human resources, financial resources, information, and technology systems aspects.

Conclusion

Despite various challenges, PPPs in PHC can facilitate access to health care services, especially in remote areas. Governments should consider long-term plans and sustainable policies to start PPPs in PHC and should not ignore local needs and context.

Keywords: Public-private partnership, Primary health care, Health policy and system research, Decision-making

Background

Achieving the highest possible level of health is a fundamental right for every human being [1]. Two years ago, 40 years after signing the Declaration of Alma-Ata (1978) [2], world leaders reinstated that ‘strengthening Primary Health Care (PHC) is the most inclusive, effective and efficient approach to enhance people’s physical and mental health, as well as social well-being’ [3]. The Astana Declaration on PHC (2018) reiterated that PHC is a cornerstone of a sustainable health system for universal health coverage (UHC) and health-related Sustainable Development Goals. It also called for all stakeholders to work as partners while taking joint action to build stronger and sustainable PHC [3]. When implementing this Declaration, countries will choose their unique paths towards UHC. Regardless of their choice, all of them would require effective cooperation and involvement of all major stakeholders (i.e., patients, health professionals, the private sector, civil society, local and international partners, and others).

Previous studies have shown that, despite substantial contributions and previous successes, provision of PHC services solely via the public sector providers has its limitation and some potential problems are well-documented (e.g., shortage of human resources, inefficient institutional frameworks, inadequate quality and efficiency due to a lack of competition, particularly in remote and rural areas) [4, 5]. In response to these challenges, some suggested that public-private partnerships (PPPs) initiatives could help to make PHC services provision more effective and efficient [6–12]. PPPs are voluntary cooperative arrangements between two and more public and private sectors in which all participants agree to work together to achieve a common purpose or undertake a specific task and to share risks and responsibilities, resources and benefits [13]. The flexible nature of PPPs provides a framework for developing and adapting existing structures to meet the specific needs of each project [14]. For instance, among the objectives of PPPs could be the establishment of a sustainable financial system; capacity-building reforms and management reforms in the public and private sectors; preventing unintended outcomes in the growth of the private sector in health; cost control and improving the health of the community; facilitating socio-economic development; improving PHC services coverage, quality, and infrastructure; as well as increasing the demand for health services [15].

Local support and private initiatives could become viable when improving PHC performance under a PPP, particularly in a situation when PHC does not have the necessary facilities to provide services, the utilisation of PHC services provided by the public sector is low, and there is a lack of effective mechanisms to evaluate and monitor its performance [5]. Private providers may also play an important role in the management of public health problems, such as malaria, sexually transmitted diseases, and tuberculosis (TB) [4, 16]. It was previously shown that among the main reasons for service uptake from private PHC providers were better geographic access, shorter waiting times, more flexible opening hours, easier access to staff consultations and medication, and more confidentiality regarding disease-related symptoms [4, 17–20]. Moreover, the use of PPPs can significantly reassure and reduce the fear of privatising health care services [6]. Not surprisingly, PPPs are rapidly expanding and becoming an integral part of effective health interventions [21]. They have been tested as a means of ensuring the provision of comprehensive PHC service is efficient, effective, and fair [22]. PPPs are also often perceived as an innovative method that can produce desired results, particularly when the market fails to distribute health benefits to those who need them (i.e., disadvantaged and the poor people in developing countries) [23, 24].

Our scoping review aimed to examine evidence on the use of PPPs in the provision of PHC services and answer the following questions: What target groups have been assigned to receive PHC services via PPPs? What kind of PHC services and processes were provided via PPPs? What arrangements or methods have been used to transfer PHC services to a private sector? What are the results of the service delivery using PPPs? What is the experience of PHC service users? What were the lessons learnt?

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

Six databases (ScienceDirect, Ovid Medline, PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Scopus) were searched between September and October 2018 for studies reporting on PPPs models used in PHC services provision. We used the following search terms: PPP or public-private partnership(s), public-private participation, public-private collaboration, public-private engagement, public-private mix, in combination with PHC or primary health care, primary healthcare, health care, healthcare, public health. A detailed search strategy for each database can be found in Appendix. The publication language was restricted to English. There were no time restrictions. We supplemented our review by a grey literature search conducted using the World Health Organization databases and websites of private health institutions. Additionally, the references of all included papers were searched for articles not identified through electronic searches.

Study selection

The titles and abstracts of documents were assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Appendix) by two co-authors (NJ and LD). Any disagreements were be resolved by a third independent reviewer (JST). References were managed using EndNote X8 (Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA, USA).

Data extraction and synthesis

We extracted the following information from the studies included in the review: setting, objectives, type of study, services, type of model, results, challenge, and recommendation (Table 1). Based on extracted data, we identified themes related to challenges, design, and implementation recommendations of PPPs projects in PHC service provision.

Table 1.

Key features of studies included in the review

| Author, year | Location /setting | Objective(s) | Type of study | Services | Model type | Target group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed F, Nisar N, 2010 [15] | Pakistan | Examines barriers to further development of PPP in Pakistan | Narrative review | – | PPP (contracting out) | – |

| Ardian M et al., 2007 [13] | Indonesia | To describe a successful partnership between the district health department, a private company and non-governmental health care providers | Descriptive-case study | Case detection, treatment | PPP | TB case |

| Argaw MD et al., 2016 [25] | Ethiopia | To analyse health facility reports on malaria service delivery to assesses the magnitude of cases and adherence of health care workers on the national standards | Retrospective descriptive | Malaria diagnosis and treatment | PPP | Suspected of malaria |

| Arora V et al., 2004 [22] | India | To increase case notification in the revised national TB control program and to improve treatment outcome in the private sector through the implementation of dots principles | Intervention | Diagnosis and treatment of TB patients | PPM | Suspected of TB, Patient with TB |

| Baig M et al., 2014 [6] | India | Assess the nature and extent of primary health care services provided in PHCs managed by NGOs and Corporates, as compared to the government | A case study | Immunisation services, health promotion, treatment of common ailments, malaria management, delivery services | PPP | The people of a region |

| Balasubramanian R et al., 2006 [26] | India | To evaluate a rural public-private partnership model within the TB control program | Cohort | Case detection, treatment | PPP | TB case |

| Barr DA, 2007 [27] | USA | Provide an overview of the history of health-related PPPs during the past 20 years and describe a research protocol commissioned by the world health organisation to evaluate the effectiveness of PPPs in a research context | Descriptive protocol | – | PPP | – |

| Bourgeois DM et al., 2014 [28] | UK | Introducing an oral health collaborative promotion program called Live.Learn.Laugh | Narrative review | Educational and research services of oral health | PPP | Schools, kindergarten, mothers of students, the general population |

| Brad Schwartz J, Bhushan I, 2004 [7] | Cambodia | To examine the effects on immunisation equity of the large-scale contracting of primary healthcare services in rural areas of Cambodia | Intervention | Coverage targets and equity targets for all primary healthcare services, including immunisation of children | PPP | Five of nine rural districts which together have a population of over 1.25 M people |

| Chongwe G et al., 2015 [29] | Zambia | Determine the extent of private-sector capacity, participation, practices and adherence to national guidelines in the control of TB | Cross-sectional survey | Diagnose TB- manage a case of TB by providing drugs | PPM | TB case |

| Dewan PK et al., 2006 [8] | India | To review the characteristics of the PPM projects in India and their effect on case notification and treatment outcomes for TB | Literature review | Diagnosis and treatment of TB patients | PPM | Patients with TB and those suspected to have TB |

| Ejaz I et al., 2011 [30] | Pakistan | Presenting viewpoints of government, NGOs and donors in Pakistan about PPP | Qualitative | – | PPP | – |

| Engel N, van Lente H, 2014 [9] | India | Discuss three early PPMs from the point of view organisational innovation and control practices | Qualitative | – | PPM | – |

| Farahbakhsh M et al., 2012 [23] | Iran | Compare the performance quality of two cohorts of public and cooperative health centres in several health service delivery programs throughout 2001–2002 | Cross-sectional comparative | Immunisation, maternal, child healthcare, family planning, environmental health, school health, health education, outpatient visits | PPP (contracting out) | The population of the region (9000 to 17,000) |

| Fobosi S et al., 2017 [31] | South Africa | To inform future service development for sex workers and describe the North Star’s contribution to healthcare provision to this population in South Africa | Case study | Healthcare service package in roadside wellness clinics | PPP | Truck drivers, sex workers and their clients, and individuals from the surrounding communities that do not otherwise have access to clinics |

| Ganguly P et al., 2014 [32] | India | To explore the factors influencing private obstetricians’ decisions to enrol in the “Chiranjeevi Yojana” scheme, reasons behind their willingness or reluctance to continue, and the reasons why some choose never to participate at all | Qualitative | Providing free intrapartum care | PPP | Poor and tribal women |

| Ghanashyam B, 2008 [33] | India | A report on health care status in India and reviewing opinions for entering the private sector and participating in primary care | Descriptive | – | PPP | – |

| Gidado M, Ejembi C. 2009 [34] | Kaduna state, Nigeria | Comparing the roles of public and private health care facilities in the TB program and TB case management practices and treatment outcomes among patients managed in these health facilities | Comparative cross-sectional | Case detection, treatment | PPM | TB case |

| Gold J et al., 2012 [35] | Australia | Report of experience of partnering with a large private telecommunications provider in order to deliver a health promotion intervention using mobile phone text messages (SMS) | Descriptive | Send a promotional message to promote sexual health | PPP | Eligible mobile advertising subscribers |

| Handler AS, et al., 2015 [36] | USA | To illustrate how the Illinois breast and cervical cancer program as the public entity has partnered with private physicians, community clinics, and hospitals to effectively deliver breast and cervical cancer services to low-income women across Illinois | Qualitative | Provide quality screening, promote diagnostic services for early detection of breast and cervical cancer, disseminate culturally sensitive public information and education programs | PPP | Women of low income, racial/ethnic minorities, rarely or never screened, and older women |

| Harris DM, et al., 2012 [37] | USA | To raise awareness of the use of school salad bars as an important part of a comprehensive public health effort to improve child nutrition, to place 6000 salad bars in schools over 3 years | Perspective | Promote fruit and vegetable consumption among schoolchildren by school salad bars | PPP | School-age youth |

| Herman NG, 2008 [38] | New York city | Describes the program developed by New York College of Dentistry to improve New York city head start children’s oral health | Descriptive-case study | A comprehensive oral health program (educational, preventive and treatment services) | PPP | Preschool children in low-income families |

| Hirano D, 1998 [39] | USA | Provides an overview of the Arizona partnership for infant immunisation, a coalition of the Arizona Department of Health Services and its partners in the public and private sectors | Overview | Implementing the Arizona Department of Health Services infant immunisation action plan, improve service delivery, provider awareness, community awareness | PPP | All children 2 years of age by the year 2000 |

| Imtiaz A et al., 2017 [10] | Pakistan | To assess the utilisation of maternal and child health services before and after implementation of PPP in district Abbottabad, Pakistan | A cross-sectional study | Vaccination of children in an expanded program of immunisation, vaccination of women for tetanus toxoid, postnatal visits, family planning | PPP | Maternal and child |

| Joloba M et al., 2016 [40] | Uganda | Redesigned the TB specimen transport network and trained healthcare workers to improve multidrug-resistant TB detection | Intervention | Improving multidrug-resistant TB detection by TB specimen, transport network development and training, mapping and specimen referral to the national TB reference laboratory | PPP | Patients with TB and those suspected to have TB |

| Kell K et al., 2018 [11] | UK | Report the main outcomes of the past 12 years of partnership, in particular, the key outreach and figures of phase III evaluation | Descriptive | Phase I: 2005–2009 Multiple objective public health programs; Phase II: 2010–2013 Oral health education and promotion programs with a focus on children, patients, mother and infants, communities; Phase III: 2014–2016 School oral health program,21-days education program and world oral health day activities | PPP | Children, patients, mother and infants, communities |

| Kim HJ et al., 2009 [41] | Korea | To improve treatment outcomes in the private sector by developing a public-private collaboration model for strengthening health education and case holding activities with public health nursing in the private sector | Prospective cohort study | Diagnosis and treatment of TB patients | PPP | Patients with TB and those suspected to have TB |

| Kramer K et al., 2017 [42] | Tanzania | To comprehensively describe the functioning of the Tanzanian national voucher scheme and examines the effectiveness and equity of the scheme | Case study | Provide three voucher distribution models to increase the reach of target groups for insecticide-treated nets and long-lasting insecticidal nets | PPP | Pregnant women and infants |

| Kumar M, et al., 2005 [43] | India | Describe and analyse the outcomes of a pilot project PPP and laboratory-based surveillance | Intervention | Diagnosis, treatment | PPP | TB case |

| Kumar M, et al., 2016 [44] | India | To assess the function of mobile medical units in Jharkhand, India and to identify the factors influencing the utilisation of mobile medical units | Cross-sectional comparative | Provide curative as well as preventive services | PPP | People in 24 remote and hard-to-reach districts in Jharkhand, India |

| Loevinsohn B et al., 2005 [45] | USA | Examine the effectiveness of contracting, examine the extent to which anticipated difficulties occurred during implementation, make recommendations about future efforts in contracting | Review | – | PPP (contracting out) | – |

| Loevinsohn B, et al., 2009 [46] | Pakistan | To evaluate the performance of the contractor, health facility surveys, household surveys, and routinely collected information were used to compare the experimental district with a contiguous and equally poor district | Cross-sectional comparative | Provide a broad range of PHC services, including preventive, promotion and curative care | PPP | The population covered in Rahim Yar Khan, Pakistan |

| Lönnroth K, et al., 2004 [47] | India, Viet Nam, Kenya, India | To compare processes and outcomes of four PPM projects on dots implementation for tuberculosis control in New Delhi, India; Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam; Nairobi, Kenya; and Pune, India | Cross-project analysis | Diagnosis and treatment of TB patients | PPM | Patients with TB and those suspected to have TB |

| Miles K et al., 2014 [21] | Papua New Guinea | Describes a multifaceted PPP between a major oil and gas producer, the national Department of Health and associated development partners in Papua New Guinea | Descriptive | Providing HIV prevention, education and treatment services | PPP | The local population - HIV-infected people, basic HIV awareness education to church groups, community groups and local female sex workers |

| Mili D, Mukharjee K. 2014 [5] | India | To understand the reasons for participation of NGOs in the PPP program, gauge the extent of community involvement and the benefits accrued by the communities in this program | Cross-sectional | Provide basic health care services | PPP (contracting out) | The population of the poor and remote areas of Arunachala Pradesh, India |

| Mohanan M, et al., 2013 [48] | Gujarat, India | To evaluate the effect of the Chiranjeevi Yojana program, a PPP to improve maternal and neonatal health in Gujarat, India | Observational study | Maternity services | PPP | Maternal and neonatal among poor women |

| Mudyarabikwa O, Regmi K, 2016 [49] | UK | To assess to what extent PPPs would increase efficiency in public procurement of primary healthcare facilities | Qualitative | – | PPP | – |

| Murthy K, et al., 2001 [20] | India | To determine whether private practitioners and the government can collaborate with a non-governmental intermediary to implement directly observed treatment, short-course strategy (DOTS) effectively | Cross-sectional | Case detection, treatment | PPP | Patients with TB and those suspected to have TB |

| Newell JN et al., 2004 [50] | Nepal | To implement and evaluate a PPP to deliver the internationally recommended strategy dots for the control of TB in Lalitpur municipality, Nepal | Intervention | Diagnosis and treatment of TB patients | PPP | Patients with TB and those suspected to have TB |

| Newell JN et al., 2005 [51] | Nepal | To describe leadership, management and technical lessons learnt from the successful implementation of a PPP for TB control in Nepal | Qualitative | – | PPP | – |

| Njau R et al., 2009 [52] | Tanzania | Extensive literature review of various PPP models in health in scale and in scope which are aimed at advancing public health goals in developing countries | Case study | – | PPP | – |

| Oluoha C et al., 2014 [12] | Nigeria | To assess the contribution of the private health facilities in providing immunisation services in four local government areas | Retrospective descriptive | Immunisation services | PPP | Children |

| Pal R, Pal S, 2009 [53] | India | Analyse the progress and success of PHC in the new millennium | Perspective | – | – | – |

| Pérez-Escamilla R. 2018 [54] | China, India, South Africa, Germany, the United Kingdom, Brazil and Mexico | To identify the key factors of successful implementation of Mondelēz International Foundation-supported school-based PPPs in seven countries | Qualitative | Fostering healthy dietary and physical activity behaviours | PPP | Children, adolescents, women, mothers, pregnant women |

| Perry CL et al., 2015 [55] | USA | Introduces a special issue of seven articles on childhood obesity from the centre and the implications of this research for obesity prevention | Literature review | To address child health issues through research, service, and education | PPP | Child health |

| Quy H et al., 2003 [56] | Vietnam | To assess the impact on case detection of a PPM project linking private providers to the National TB Program | Intervention | Case detection. Treatment. | PPM | TB case |

| Ramiah I, Reich MR, 2006 [57] | Botswana | Analyses the multiple challenges that African Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Partnerships confronted in its first 4 years in the building and managing its relationships with other organisations and among African Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Partnerships partners | Qualitative | – | PPP | – |

| Rangan S et al., 2004 [58] | India | To develop a ‘model’ partnership between rural private medical practitioners and the revised national TB control program | Intervention | Diagnosis, treatment | PPM | TB case |

| Reviono R et al., 2017 [59] | Indonesia | To explore the case detection achievements of the tuberculosis program since ppm implementation in central Java, Indonesia in 2003 | Retrospective cohort study | Case detection, treatment | PPM | TB case |

| Ribeiro CA et al., 2016 [60] | Brazil | Describe public-private partnership in the prevention of influenza amongst industry workers in Ceara state, Brazil | Case study | Vaccination against influenza | PPP | Industry workers |

| Sheikh K et al., 2006 [61] | India | Review two studies on the private sector in India for TB and HIV, and highlight future policy directions for involving PPM in public health programs | Cross-sectional observational | Diagnosis, referrals, TB and AIDS treatment | PPM | Those suspected to have TB and AIDS |

| Sil et al., 2010 [62] | USA | To improve access to quality oral health care in central Massachusetts with the central Massachusetts oral health initiative | Case study | Oral health care | PPP | Mothers, pregnant women, children |

| Silow-Carroll S, 2008 [63] | USA | Describe the implementation of Iowa’s 1st Five Initiative: improving early childhood development services through public-private partnerships | Narrative review | Screening referrals and follow-up for mental health | PPP | All young children ages 0 to 5 years and their families |

| Sinanovic E, Kumaranayake L, 2006 [4] | South Africa | To evaluate the quality of care for the treatment of TB provided in different PPPs | Cross-sectional comparative | Case detection, treatment | PWP, PNP | TB case |

| Singh A et al., 2009 [64] | India | Investigating the provision of skilled nursing care and emergency care for the poor through a partnership with the private household in Gujarat, India | Observational study | Maternity services | PPP | Poor women |

| Tanzil S et al., 2014 [65] | Pakistan | Assess the range and quality of healthcare services at the basic health units in Sindh, Pakistan, administered by the district governments as compared to the basic health units which are being contracted and now managed by the peoples’ primary healthcare initiative | Cross-sectional survey | Primary health care services | PPP (contracting out) | The population of the district |

| Ullah ANZ et al., 2012 [66] | Bangladesh | Analyses the basic concepts and key issues of the existing collaboration between government and NGOs in health care | Qualitative | – | PPP | – |

| Uplekar M, 2003 [67] | Switzerland | Presents the guiding principles of PPM dots and major elements of the global strategy | Narrative review | – | PPM | – |

| Uplekar, 2016 [68] | Switzerland | To present a global perspective on the progress and prospects of expanding PPM for TB care and prevention | Perspective | – | PPM | – |

| van de Vijver S, et al., 2013 [69] | Sub-Saharan Africa | To describe a study design that integrates public health and private-sector approaches to lead to the development and introduction of a service delivery package for cardiovascular disease prevention among urban poor | Descriptive | Awareness Access to screening for CVD risk factors Treatment Seeking Long-term compliance | PPP | Korogocho, a Nairobi slum with a total population of 35,000, screening is for those over 35 years old |

| Zafar Ullah A, et al., 2006 [70] | Bangladesh | To develop and evaluate a PPP model to involve private medical practitioners in the TB control activities | Intervention | Diagnosis Treatment follow-up | PPP | TB case |

PPPs Public-Private Partnerships, TB Tuberculosis, NGO non-governmental organisations, PPM Public-Private Mix, PWP Public-Private Workplace Partnership, PNP Public-NGO Partnership

Results

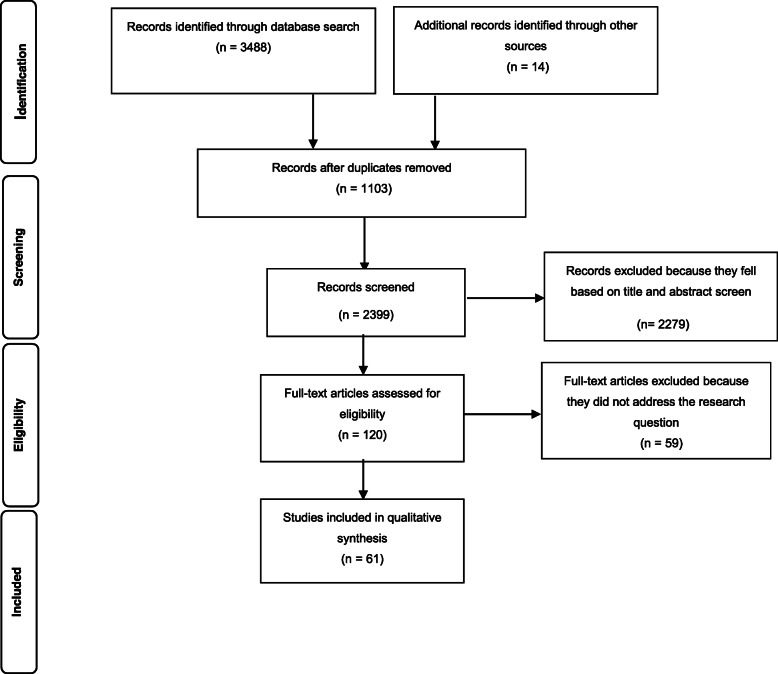

The results of the screening process are shown in Fig. 1. In total, 3488 documents were screened by title and abstract for possible inclusion in the review. Additional 14 documents were identified through the manual search. After screening all titles and abstracts, the full text of 120 documents was assessed against the eligibility and exclusion criteria, and 61studies were selected and included in the final review (Table 1). Of 61 selected studies, 32 studies were conducted in Asian countries; 11 studies in African countries; 11 studies in North and South American countries; one study was conducted in several different countries; three studies in the UK; two studies in Switzerland and one study in Australia. Of 61 selected studies, ten (16.3%) were descriptive, nine (14.7%) were qualitative, eight (13.1%) were case studies, eight (13.1%) were intervention studies, eight (13.1%) were reviews, seven (11.5%) were cross-sectional comparative studies, five (8.2%) were cross-sectional studies, three (4.2%) were cohort studies, and three (4.2%) were prospective studies. We observed that reported PPPs fell into one of the three broad categories: PPPs contracted out for basic PHC services, PPPs in health education and promotion programs, and PPPs in services for infectious diseases. Hence, we used this categorisation to summarise our findings.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart of study selection

PPPs contracted out for basic PHC services

A wide range of basic PHC services in Iran, England, Pakistan, India, Nigeria, Cambodia, Brazil, Arizona (US) and Bangladesh (i.e., prevention, promotion, and medical care, including maternal and child health care, family planning, environmental health, school health, health education, immunisation services, health promotion, common diseases treatment, malaria management, maternity services, postpartum services, and vaccination against influenza) was outsourced to PPPs and delivered to specific target groups (i.e., children, mothers, pregnant women, industrial workers, poor residents in the remote areas). The provision of these basic PHC services (infrastructure, procurement, and services management) was contracted out to private sector providers to facilitate better access and coverage of the population. The majority of studies reported that the provision of basic PHC services by private sector actors increased access to services, improved aspects of care, and resulted in various positive outcomes [5, 7, 10, 12, 23, 33, 39, 44–46, 49, 53, 60, 64, 65]. However, there was also some criticism as well. For example, Baig et al. [6] showed that the management of immunisation services, health promotion, disease treatment, and malaria by PPPs could also be seriously inadequate. Mahan et al. [35] also reported that due to being perceived as having poor quality by the local population, the uptake of institutional and maternal delivery provided in the private hospitals was low despite being offered free of charge.

PPPs in health education and promotion programs

Studies provided evidence regarding successful PPPs project implementation in the field of health education and promotion (i.e., oral health, sexual health, screening programs, and nutrition). For example, a PPP launched in 2010 by the FDI World Dental Federation and the Unilever measurably improved the oral health among children by encouraging children in kindergartens and schools, student mothers and the general population to brush teeth with a fluoride-containing toothpaste at least twice a day [11, 28]. The comprehensive Oral Health Program created by the New York Dental College [38] for preschool children from low-income families and the Central Massachusetts Oral Health Initiative (CMOHI) [62] in the US for mothers, pregnant women, and children, also increased access to oral health care.

In the field of sexual health in South Africa, the North Star Alliance (a not-for-profit, non-governmental organisation established in 2006) united the transport sector in its response to the AIDS pandemic. It provided healthcare service package in roadside wellness clinics for truck drivers, sex workers, and their clients, as well as individuals from surrounding communities that do not have access to clinics otherwise. They also referred patients with complications to other health facilities in collaboration with the government and other non-governmental organisations [31]. In Australia, a partnership between the research institutions and the telecommunications service provider was established to promote sexual health. The research institutes created the content of the sexual health campaign sent via text messages, while the telecommunications service provider performed randomisation of eligible mobile advertising subscribers for broadcasting the text messages [35].

In the field of breast and cervical cancer screening, in the US, the cooperation of a public institution with a group of private physicians, community clinics and hospitals led to a provision of better quality screening services. These included the provision of updated diagnostic services, the dissemination of educational, cultural and general information to low-income groups, racial and ethnic minorities, and senior women [36]. In South Africa, a package of interventions to prevent cardiovascular diseases among poor citizens was designed and implemented with the participation of the private sector, which had an overall positive reaction of the population [69]. In the field of mental health screening, a successful project was launched in Iowa (the US) through the Commonwealth Fund’s Assuring Better Child Health and Development II project. This project created a coalition of public and private partners that focused on designing, testing, and identifying best practices for enhancing health care providers’ mental health screening and referrals for all young children and their families, and ensuring effective coordination of assessment, intervention, follow-up, and communication back to the primary care practitioners [63].

In the field of nutrition, in 2010, in the US, the National Fruit & Vegetable Alliance, United Fresh Produce Association Foundation, the Food Family Farming Foundation, and the Whole Foods Market together launched the School Salad Bars initiative. This program provided resources and support to schools implementing the School Salad Bars initiative to raise awareness of the use of school salad bars, promote the consumption of fruits and vegetables among school students and improve their nutrition. This initiative resulted in an uptake of this program by approximately 700,000 students in 2012 [37]. Another successful global project was implemented in Asia (China and India), Africa (South Africa), Europe (Germany, United Kingdom), and Latin America (Brazil and Mexico). It fostered developing healthy diet habits and promoted the adoption of a physically active lifestyle among children, adolescents, women, mothers, and pregnant women [54].

In the field of health research, a successful PPP in Texas (the US) was established to prevent childhood obesity by focusing research on improvements in children, family, and community health through etiologic, epidemiologic, methodologic, and intervention research [55]. Other successful partnerships (e.g., Medicines for Malaria Venture and Global Alliance for TB Drug Development) have been implemented to facilitate universal access to essential drugs and health services, accelerate research and development in the fields of vaccines, diagnostics, and drugs for neglected diseases [52].

PPPs in services for infectious diseases

Studies also provided evidence regarding successful PPPs in the delivery of infectious disease services (i.e., malaria, TB, HIV/AIDS). PPPs in malaria case management in Tanzania and Ethiopia led to successful results and increased benefits among pregnant mothers, infants, and patients with malaria [25, 42]. PPPs formed by governments, international donors, and pharmaceutical companies in India and several African countries were also successfully used to control AIDS and provide diagnostic and treatment services to suspects and AIDS patients [57, 61]. PPPs were also used for the provision of diagnostic, treatment, and management of TB in Zambia, Vietnam, Indonesia, South India, Nigeria, Kenya, Nepal, Uganda, Korea, Bangladesh, and South Africa [4, 8, 13, 20, 22, 26, 29, 34, 40, 41, 43, 47, 50, 51, 56, 58, 59, 61, 66]. The following models of partnerships were reported: PPPs, Public-Private Mix (PPM), Public-Private Workplace Partnership (PWP), and Public-NGO Partnership (PNP). PWP and PNP models were used successfully to provide TB services in South Africa. Sites using PWP were reported to have the highest score of all aspects of quality of care (structure, process, and outcomes). PWP and PNP models were similar to solely public providers in terms of process quality, reflecting a very good knowledge of the treatment guidelines among both private and public providers [4]. PPM was used as a strategic initiative to engage all private and public health care providers in the fight against TB, using international health care standards [47, 71]. Unlike PPP, which is based on long-term contracts with risk sharing and decision-making and a high level of collaboration, PPM involves actors from all sectors for non-contractual collaboration with a vertical disease focus [72]. Overall, evidence suggests that the use of various models of partnerships led to an increase in the TB case detection rates and the success of curative services [4, 8, 13, 20, 22, 26, 29, 34, 40, 41, 43, 47, 50, 56, 58, 59, 61, 66]. Among the mechanisms and tools used to achieve this success were the design of referral forms and treatment cards, the implementation of the referral mechanism, the free distribution of medication, and the encouragement of patients to complete the course of treatment. Only two studies reported that participation of the private sector in TB control and care resulted in below the optimal level [29] and poor treatment outcomes [47].

Challenges and recommendations

Despite some positive outcomes and achievements, detailed analysis of studies results showed that partnerships between public and private sectors faced multiple challenges, particularly during the starting and implementation phases. We grouped these challenges into five areas: education, management, human resources, financial resources, and information and technology systems (Table 2).

Table 2.

Challenges of Public-Private Partnerships in Primary Healthcare

| Education | |

| ▪ Inadequate education for justification of people to participate in collaborative projects [38, 51] | |

| ▪ Insufficient knowledge of the private about testing and treatment procedures [51, 56, 61, 67] | |

| Management | |

| ▪ Lack of commitment of public and private sector managers and decision-makers [9, 51, 52, 58, 73] | |

| ▪ Lack of clear vision on the way forward [68, 70] | |

| ▪ Non-formulation of strategic direction for PPPs models by the government [70] | |

| ▪ Lack of accountability, poorly defined roles and lack of advisory committees [30, 52] | |

| ▪ The difficulty of coordinating different members, especially in the early stages [47, 66] | |

| ▪ Poor leadership skills [32] | |

| Human resource | |

| ▪ Lack of trust between the public and private sectors(9, 47, 54, 57, 70)s | |

| ▪ Disparities in power actors involved in partnership [15, 32] | |

| ▪ Limited access to people willing and able to participate in the private sector [32, 38] | |

| ▪ Lack of capacity of private practitioners and hospitals to undertake non-clinical tasks such as treatment supervision or prompt recording and reporting of required data [51, 61, 68] | |

| ▪ Lack of perceived ownership of the project by partners [42, 61] | |

| ▪ Reported disrespect and distrust of the public sector towards partners from the private sector [9, 67, 70] | |

| Financial resources | |

| ▪ Downsizing of social capital [15] | |

| ▪ Inadequate financial resources [28, 40, 42, 59, 68] | |

| ▪ Sustainability of the PPPs [49] | |

| ▪ Insecure funding [31, 68, 70] | |

| ▪ Lack of trust by private sector partners at the reimbursement system [51, 62] | |

| ▪ The unwillingness of the public sector to use financial incentives for private sector motivation [43, 67] | |

| ▪ Not setting the specified budget for PPP [9] | |

| Information and technology systems | |

| ▪ A weakness of the private sector in the documentation of services provided by the private sector [34, 35, 41, 49, 51, 53, 56, 63] | |

| ▪ Lack of consistent form of interaction between the public and private sectors due to different systems [9, 15, 51, 67] | |

| ▪ Lack of appropriate monitoring and reporting mechanisms [9, 15, 49, 67] | |

| ▪ Lack of clarity in policies regarding the implementation and evaluation of PPPs [15, 46, 70] | |

| ▪ Absence of support systems for supervision and record-keeping for private-sector employees [26, 58] | |

| ▪ Inefficient administrative system [61, 62] | |

| ▪ Weak capacity to collaborate or regulate [54, 57, 68, 70] | |

| ▪ Weakness in implementing regulations [68] | |

| ▪ Inadequate mechanisms to ensure continuity of care [68] | |

| ▪ Information gaps exist between public and private sector [10, 40, 57, 67] | |

| ▪ Absence of external performance assessment of PPPs [10] | |

| ▪ Lack of standard internal monitoring system [10] | |

| ▪ Failure to define an indicator for evaluation of PPPs [8, 9, 11] | |

| Others | |

| ▪ Low efficiency of the private sector in taking care of the poorest sectors of society [15] | |

| ▪ The poor capacity of the public sector to design and manage contracts with private organisations [10, 45, 68] |

PPP Public-Private Partnership

In education, among main problems were an inadequate level of knowledge related to testing and treatment procedures and inadequate knowledge for justification of people to participate in collaborative projects by providers [38, 51, 56, 61, 67]. In management, challenges encompassed lack of strategic vision and commitment from various partners, poorly defined roles and expectations, difficulties in member coordination, and a lack of leadership skills [2, 9, 30, 32, 47, 51, 52, 58, 66, 68, 70, 73]. In human resources, reported challenges related to a lack of trust between private and public partners, ownership identity, disparities in power, and lack of capacity to undertake non-clinical tasks by staff in private clinical settings [9, 15, 32, 38, 42, 47, 51, 54, 57, 61, 67, 68, 70]. For financial resources, issues were rooted in inadequate and insecure funding, questions over the long-term sustainability of PPPs, lack of trust in the reimbursement system used by private partners, and not accounting for PPPs in annual budgeting process [9, 15, 28, 31, 40, 42, 43, 49, 51, 59, 62, 67, 68, 70]. For information and technology systems, challenges originated from unclear policies and regulations regarding the implementation and evaluation of PPPs, problems with documentation and record-keeping in private sector providers, a weak capacity to collaborate between sectors or implement regulations, information gap and lack of standardisation, and lack of sufficient monitoring due to lack of defined indicators [8–11, 15, 35, 41, 46, 49, 51, 53, 56, 63, 67, 70]. Additional challenges arose from low efficiency of the private sector in taking care of the poorest strata of the population, as well as a lack of capacity of both sectors to engage with one another [10, 15, 46, 68].

Studies also provided recommendations on how to overcome reported challenges and create effective partnerships (Table 3). For example, in education this can be done by ensuring that only most up-to-date and evidence-based treatment guidelines are used in both sectors, conducting sensitisation workshops based on needs assessment, as well as developing effective information, education and communication strategies for the communities [13, 26, 28, 29, 34, 49, 63, 68]. In management, one could consider to streamline regular communication and coordination between collaborators, encourage commitment and engagement, ensure that there is appropriate legislation that supports the work of PPPs, clarify roles and responsibilities, set realistic goals and objectives, and ensure better coordination of collaboration [8, 9, 13, 35, 39, 46, 49, 53, 58, 61]. In human resources, it is vital to facilitate good communication between all members of PPPs, encourage a positive attitude towards PPPs, bring strong stakeholders into partnerships, and create a culture of respect, appreciation, and trust [9, 31, 47, 51–53, 57, 74, 75]. For financial resources, it is important to introduce financial incentives, ensure funding sustainability, and identify alternate financial suppliers [6, 28, 36, 56, 59, 69, 74]. For information and technology systems, one should consider placing quality assurance mechanisms, building appropriate legislative frameworks, setting up monitoring and documentation systems, using digital tools, and strengthening information systems [6, 9, 13, 15, 20, 54, 59, 61, 63, 75]. To support these efforts, it is important to have some flexibility in PPPs models and complement it by political and community support of PPPs [38, 51, 53, 61, 76].

Table 3.

Recommendations for effective Public-Private Partnerships in Primary Healthcare

| Education | |

| ▪ Improving training of the private health practitioners based on the latest treatment guidelines [13, 28, 29, 49, 51, 63] | |

| ▪ Ensuring the knowledge transfer of the most effective, latest and evidence-based treatment guidelines [29, 39, 47, 49] | |

| ▪ Effective information, education and communication strategies in the community [26] | |

| ▪ Conducting sensitisation workshops [67] | |

| ▪ Conducting retraining courses during participation based on needs assessment [6, 34] | |

| Management | |

| ▪ Choosing a strong interface to ensure coordination between partners [8, 9, 46, 47, 51, 57, 61, 67] | |

| ▪ Organising regular meetings to maintain communication and to foster and coordinate plans [9, 47, 62] | |

| ▪ Creating more commitment among partners [13, 21, 26, 47, 49, 51, 53, 58, 61, 62, 64, 70] | |

| ▪ Creation of a national policy document outlining schemes for PPP [61, 70] | |

| ▪ Having a clear delegation of duties and creating process indicators for initiating and sustaining partnerships with private providers [20, 30, 35, 53, 58, 61] | |

| ▪ Determining a shared vision, strong governance and effective management to achieve objectives [21, 35, 39, 53, 66, 70] | |

| Human resources | |

| ▪ Creating good communication between all members of the PPPs [9, 31, 51, 57, 70] | |

| ▪ Taking concerns of all members in initial seriously [51] | |

| ▪ Encouraging positive attitudes towards the PPPs, particularly during the initial stages [51, 53] | |

| ▪ Convincing the private sector that they will benefit from the PPPs [51, 61] | |

| ▪ Creating change thinking among staff [5, 9, 67] | |

| ▪ Attracting strong stakeholders into the partnership [47, 50, 51, 53, 57] | |

| ▪ Facilitating respectful relations in the partnership [9, 57, 70] | |

| ▪ Appreciating the attitude and performance of the staff [31] | |

| ▪ Maintaining transparency between sectors to build trust [9, 31, 32, 47, 52, 66, 70] | |

| Financial resources | |

| ▪ Introducing financial incentives for private sector motivation [4, 32, 56, 69] | |

| ▪ Ensuring availability of appropriate funds [6, 28] | |

| ▪ Taking the determination of sustainable financing for partnership seriously [49, 62] | |

| ▪ Identifying alternate financial suppliers [59] | |

| Information and technology systems | |

| ▪ Ensuring the existence of a quality assurance mechanism and program [6, 13, 20, 54, 59, 70] | |

| ▪ Establishing norms [15, 61] | |

| ▪ Tackling morality and accountability issues [15, 51, 65] | |

| ▪ Building a legislative framework [9, 15, 61, 70] | |

| ▪ Defining operational strategies [8, 15, 27, 58] | |

| ▪ Strengthening supervision of private sector [6, 9, 47, 51, 65] | |

| ▪ Setting a monitoring and documentation system for referrals [9, 13, 63] | |

| ▪ Strengthening the information system [39, 57, 67] | |

| ▪ Determining the appropriate referral structure [9, 61, 67] | |

| ▪ Using digital tools in facilitating project operations and also in ensuring adherence to protocols by both providers and patients [42, 68] | |

| ▪ Ensuring continuity in care for patients by the strength of provider networks and determine policies and program actions [31, 61] | |

| ▪ Establishing procedural requirement in getting the funds released timely for grant/reimbursement to the private partner [53] | |

| ▪ Creating a payment-based financial system [27, 32, 46, 69] | |

| Others | |

| ▪ Ensuring flexibility of the PPPs model to adapt to changing circumstances [28, 51] | |

| ▪ Encouraging political and community support for partnership [43, 53, 61, 68] |

PPP Public-Private Partnership

Discussion

We examined the global experience of PHC provision via PPPs for basic PHC services, health education and promotion programs, and services for infectious diseases. The majority of PPPs projects facilitated education and health promotion initiatives and were used to increase access and to facilitate the provision of prevention and treatment services (i.e., TB, malaria, and HIV/AIDS) for certain target groups. The challenges of providing PHC via PPPs were reported primarily for the starting and implementation phases of project execution. Reported challenges and recommendations on how to overcome them fell into one of five areas: education, management, human resources, financial resources, and information systems.

To improve the health care delivery system and to overcome the limitations of financial, technical, and human resources aspects, PPPs should be considered for future health reforms [3, 15, 77]. Governments already see the potential for private sector involvement in improving public health and PHC services delivery [74, 78], as they can bring benefits to the health care system, population health, and can lead to direct and indirect costs savings [79]. They also provide an opportunity for mutual learning between colleagues by stimulating the creation of new knowledge and infrastructure, increase transparency, which can provide greater accountability, public confidence, and result in a higher quality of care [75, 76]. PPPs can lead to improvements in efficiency and effectiveness in service provision and provide a necessary platform for social tests that can enable learning, for example, on how to handle the most unsustainable health problems. However, the opponents of PPPs believe that most PPPs are weak, as developing countries do not have the resources to monitor the quality of provided health services [80, 81]. Private medical providers are also accused of self-centred attitudes and non-interference in public works. However, some doctors working for the private sector might be willing to take part in partnerships to be able to fight TB and provide HIV/AIDS services for the target population together with the public sector employees and other health sector representatives. The role of private doctors also needs to be carefully analysed and should be supported in its processes when assuming responsibility as primary caregivers [61].

A partnership should not be formed unless the public sector is strong enough to ensure that it can provide appropriate training and health care services, monitor the outcomes, and have the ability to engage as a partner in PPPs [51]. Before designing any partnership, clear and achievable public interest goals should be considered. A government structure should then ensure that the goals are in line with the needs of stakeholders in public-private partnerships, and tools and mechanisms to measure progress and success are well-defined [82]. All partners should also be motivated and provided with incentives to ensure active engagement and participation [9, 51]. All individuals who participate in the partnership must have the appropriate level of bargaining power. Hence, to form a common attitude among all partners, sensitisation and persuasion training is also recommended [51, 82]. Another important element is transparent communication and accountability of all partners [30, 32, 81].

PPPs can have a better and more stable performance by improving existing healthcare infrastructure, deploying trained human resources, and, most importantly, by better monitoring doctors and professionals and managed organisations [67]. Although the implementation of a PPP model is not easy, it could be even harder to maintain it [51]. Sustainability of participatory models is one of the important issues. A lack of financial support and commitment, especially at the level of top executives, are among the issues that can distort the model’s sustainability [9, 51, 68]. Hence, the sustainability of each model of PPP depends on the ability, commitment, collaboration, and communication between the public and private sectors [9, 32, 51, 70].

Additionally, long-term planning and sustainability policies should be considered, as well as any additional health care costs. Alternative and sustainable funding sources should be identified, and PPPs must be prepared to respond to possible problems, seize the opportunities, anticipate external threats, and be flexible. The weaknesses and deficiencies of any partner involved in PPPs could potentially affect the provision and quality of PHC services. However, ultimately, it is the government and local health authorities that are responsible for PHC services provision to the population [27, 51, 68, 82].

Limitations

Our study is one of the first to review PHC services provision via PPPs. The key weaknesses of our review should, nonetheless, be kept in mind. First, our findings reflect the results of partnerships in PHC and left studies reporting on PPP use in hospitals and other healthcare sectors outside the scope of this review. Second, we only reviewed studies that were published in the English language, potentially leaving important studies reported and published in other languages.

Conclusion

Despite various challenges, PPPs could provide a good opportunity to facilitate access to health care services, especially in remote areas. However, it should be noted that the success of PPPs depends on the existence of transparency in relationships between partners, PPPs being flexible, having a sustainable financing source, mutual commitment, and the ability of the public sector to monitor and control the quality of services provided by the private sector. Therefore, governments should consider long-term plans and sustainable policies to start such partnerships and learn from the experience of other countries.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- PPP

Public-Private Partnership

- PHC

Primary Healthcare

- UHC

Universal Health Coverage

- PPPs

Public-Private Partnerships

- TB

Tuberculosis

- PPM

Public-Private Mix

- PWP

Public-Private Workplace Partnership

- PNP

Public-NGO Partnership

Appendix

Table 4.

Appendix: Search strategy

| Database | Keywords |

|---|---|

|

Science direct PubMed Embase Web of science |

A: PPP OR “public- private partnership” OR “public- private participation” OR “public -private collaboration” OR “public- private engagement” OR “Public- private mix” B: “Health care “OR “Healthcare” OR “public health” C: A AND B |

| Ovid Medline |

A: PPP OR “public- private partnership” OR “public- private participation” OR “public -private collaboration” OR “public- private engagement” OR “Public- private mix” B: PHC OR “Primary Health care “OR “Primary Healthcare” C: A AND B |

| Scopus |

A: PPP OR “public- private partnership” OR “public- private participation” OR “public -private collaboration” OR “public- private engagement” OR “Public- private mix” B: PHC OR “Primary Health care “OR “Primary Healthcare” OR “public health” C: A AND B |

| Inclusions criteria | All studies on public-private partnerships in primary health care delivery. |

| Exclusions criteria |

Studies published in any language other than English. Non-peer reviewed reports, documents and posters. Unpublished manuscripts. |

Authors’ contributions

DL and JN contributed to all phase of the study. TJS contributed to the initial idea of the study and guided it. MM and VSG made a substantial contribution to the study. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important content and approved the final version.

Funding

All stages of the research were funded by the Health Services Management Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nasrin Joudyian, Email: njoudiyan.9170@gmail.com.

Leila Doshmangir, Email: Doshmangirl@tbzmed.ac.ir.

Mahdi Mahdavi, Email: info.mahdavi@gmail.com.

Jafar Sadegh Tabrizi, Email: js.tabrizi@gmail.com.

Vladimir Sergeevich Gordeev, Email: v.gordeev@qmul.ac.uk, Email: vladimir.gordeev@lshtm.ac.uk.

References

- 1.World Health Organization: Constitution of the World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO Basic Documents; 1948.

- 2.World Health Organization. Declaration of Alma-Ata. International Conference on, Primary Health Care; Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic; Sept 6–12, 1978.

- 3.WHO . Astana declaration on primary health care: from Alma-Ata towards universal health coverage and sustainable development goals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinanovic E, Kumaranayake L. Quality of tuberculosis care provided in different models of public-private partnerships in South Africa. Int J Tuberculosis Lung Disease. 2006;10(7):795–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mili D, Mukharjee K. Public private partnership in health: a study in Arunachal Pradesh. J Datta Meghe Institute of Med Scie University. 2014;9(2):90–93. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baig M, Panda B, Das JK, Chauhan AS. Is public private partnership an effective alternative to government in the provision of primary health care? A case study in Odisha. J Health Manag. 2014;16(1):41–52. doi: 10.1177/0972063413518679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brad Schwartz J, Bhushan I. Improving immunization equity through a public-private partnership in Cambodia. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:661–667. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dewan PK, Lal S, Lonnroth K, Wares F, Uplekar M, Sahu S, et al. Improving tuberculosis control through public-private collaboration in India: literature review. Bmj. 2006;332(7541):574–578. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38738.473252.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engel N, van Lente H. Organisational innovation and control practices: the case of public–private mix in tuberculosis control in India. Sociology Health Illness. 2014;36(6):917–931. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imtiaz A, Farooq G, Haq ZU, Ahmed A, Anwer S. Public private partnership and utilization of maternal and child health services in DISTRICT ABBOTTABAD, PAKISTAN. J Ayub Med College Abbottabad. 2017;29(2):275–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kell K, Aymerich MA, Horn V. FDI–Unilever brush day & night partnership: 12 years of improving behaviour for better oral health. Int Dent J. 2018;68:3–6. doi: 10.1111/idj.12404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oluoha C, Umeh C, Ahaneku H. Assessing the contributions of private health facilities in a pioneer private-public partnership in childhood immunization in Nigeria. J Public Health Afr. 2014;5(1):40–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Ardian M, Meokbun E, Siburian L, Malonda E, Waramori G, Penttinen P, et al. A public-private partnership for TB control in Timika, Papua Province, Indonesia. The Int J Tuberculosis Lung Disease. 2007;11(10):1101–1107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.English LM, Guthrie J. Driving privately financed projects in Australia: what makes them tick? Accounting. Auditing Accountability J. 2003;16(3):493–511. doi: 10.1108/09513570310482354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed F, Nisar N. Public-private partnership scenario in the health care system of Pakistan/Projet de partenariat public-prive dans le systeme de sante du Pakistan. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16(8):910. doi: 10.26719/2010.16.8.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brugha R, Zwi A. Improving the quality of private sector delivery of public health services: challenges and strategies. Health Policy Plan. 1998;13(2):107–120. doi: 10.1093/heapol/13.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aljunid S. The role of private medical practitioners and their interactions with public health services in Asian countries. Health Policy Plan. 1995;10(4):333–349. doi: 10.1093/heapol/10.4.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arora V, Gupta R. Private-public mix: a prioritisation under RNTCP-an Indian perspective. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2004;46(1):27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lönnroth K, Thuong LM, Linh PD, Diwan VK. Utilization of private and public health-care providers for tuberculosis symptoms in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Health Policy Planning. 2001;16(1):47–54. doi: 10.1093/heapol/16.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murthy K, Frieden T, Yazdani A, Hreshikesh P. Public-private partnership in tuberculosis control: experience in Hyderabad, India. Int J Tuberculosis Lung Disease. 2001;5(4):354–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miles K, Conlon M, Stinshoff J, Hutton R. Public-private partnerships in the response to HIV: experience from the resource industry in Papua New Guinea. Rural Remote Health. 2014;14(3):2868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arora V, Lonnroth K, Sarin R. Improved case detection of tuberculosis through a public-private partnership. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2004;46(2):133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farahbakhsh M, Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Nikniaz A, Tabrizi JS, Zakeri A, Azami S. Iran's experience of health cooperatives as a public-private partnership model in primary health care: a comparative study in East Azerbaijan. Health Promotion Perspectives. 2012;2(2):287. doi: 10.5681/hpp.2012.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reich MR. Public-private partnerships for public health. Nat Med. 2002;6(6):617–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Argaw MD, Woldegiorgis AG, Abate DT, Abebe ME. Improved malaria case management in formal private sector through public private partnership in Ethiopia: retrospective descriptive study. Malar J. 2016;15(1):352. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1402-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balasubramanian R, Rajeswari R, Vijayabhaskara R, Jaggarajamma K, Gopi P, Chandrasekaran V, et al. A rural public-private partnership model in tuberculosis control in South India. Int J Tuberculosis Lung Dis. 2006;10(12):1380–1385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barr DA. A Research Protocol to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Public--Private Partnerships as a Means to Improve Health and Welfare Systems Worldwide. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):19-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Bourgeois DM, Phantumvanit P, Llodra JC, Horn V, Carlile M, Eiselé JL. Rationale for the prevention of oral diseases in primary health care: an international collaborative study in oral health education. Int Dent J. 2014;64:1–11. doi: 10.1111/idj.12126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chongwe G, Kapata N, Maboshe M, Michelo C, Babaniyi O. A survey to assess the extent of public-private mix DOTS in the management of tuberculosis in Zambia. African J Primary Health Care Family Med. 2015;7(1):1–7. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v7i1.692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ejaz I, Shaikh BT, Rizvi N. NGOs and government partnership for health systems strengthening: a qualitative study presenting viewpoints of government, NGOs and donors in Pakistan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):122. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fobosi S, Lalla-Edward S, Ncube S, Buthelezi F, Matthew P, Kadyakapita A, et al. Access to and utilisation of healthcare services by sex workers at truck-stop clinics in South Africa: a case study. S Afr Med J. 2017;107(11):994–999. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i11.12379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ganguly P, Jehan K, de Costa A, Mavalankar D, Smith H. Considerations of private sector obstetricians on participation in the state led “Chiranjeevi Yojana” scheme to promote institutional delivery in Gujarat, India: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):352. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghanashyam B. Can public-private partnerships improve health in India? Lancet. 2008;372(9642):878–879. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61380-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gidado M, Ejembi C. Tuberculosis case management and treatment outcome: assessment of the effectiveness of public-private mix of tuberculosis programme in Kaduna state, Nigeria. Annals African Med. 2009;8(1):25. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.55760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gold J, Hellard M, Lim M, Dixon H, Wakefield M, Aitken C. Public-private partnerships for health promotion: the experiences of the S5 project. Am J Health Educ. 2012;43(4):250–253. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2012.10599243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Handler AS, Henderson VA, Rosenfeld A, Rankin K, Jones B, Issel LM. Illinois breast and cervical cancer program: implementing effective public-private partnerships to assure population health. J Public Health Management Practice. 2015;21(5):459–466. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris DM, Seymour J, Grummer-Strawn L, Cooper A, Collins B, DiSogra L, et al. Let’s move salad bars to schools: a public–private partnership to increase student fruit and vegetable consumption. Childhood Obesity (Formerly Obesity and Weight Management) 2012;8(4):294–297. doi: 10.1089/chi.2012.0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herman NG, Rosenberg LR, Moursi AM. Public-private collaboration to improve oral health status of children enrolled in head start in New York City. N Y State Dent J. 2008;74(4):32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirano D. Partnering to Improve Infant Immunizations:: The Arizona Partnership for Infant Immunization (TAPII) Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(3):22–25. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(97)00038-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joloba M, Mwangi C, Alexander H, Nadunga D, Bwanga F, Modi N, et al. Strengthening the tuberculosis specimen referral network in Uganda: The role of public-private partnerships. J Infectious Diseases. 2016;213(suppl_2):S41–SS6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim HJ, Bai G-H, Kang MK, Kim SJ, Lee JK, Cho S-I, et al. A public-private collaboration model for treatment intervention to improve outcomes in patients with tuberculosis in the private sector. Tuberculosis Respiratory Diseases. 2009;66(5):349–357. doi: 10.4046/trd.2009.66.5.349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kramer K, Mandike R, Nathan R, Mohamed A, Lynch M, Brown N, et al. Effectiveness and equity of the Tanzania National Voucher Scheme for mosquito nets over 10 years of implementation. Malar J. 2017;16(1):255. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1902-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar M, Dewan P, Nair P, Frieden T, Sahu S, Wares F, et al. Improved tuberculosis case detection through public-private partnership and laboratory-based surveillance, Kannur District, Kerala, India, 2001–2002. Int J Tuberculosis Lung Disease. 2005;9(8):870–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar M, Kiran A, Kujur M. Assessment of mobile medical units functioning in Jharkhand, India. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2017;3(4):878–880. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loevinsohn B, Harding A. Buying results? Contracting for health service delivery in developing countries. Lancet. 2005;366(9486):676–681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loevinsohn B, Ul Haq I, Couffinhal A, Pande A. Contracting-in management to strengthen publicly financed primary health services—the experience of Punjab, Pakistan. Health Policy. 2009;91(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lönnroth K, Uplekar M, Arora VK, Juvekar S, Lan NT, Mwaniki D, et al. Public-private mix for DOTS implementation: what makes it work? Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:580–586. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mohanan M, Bauhoff S, La Forgia G, Babiarz KS, Singh K, Miller G. Effect of Chiranjeevi Yojana on institutional deliveries and neonatal and maternal outcomes in Gujarat, India: a difference-in-differences analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;92:187–194. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.124644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mudyarabikwa O, Regmi K. Public-private partnerships and efficiency in public procurement of primary healthcare infrastructure: a qualitative research in the NHS UK. J Public Health. 2016;24(2):91–100. doi: 10.1007/s10389-015-0701-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newell JN, Pande SB, Baral SC, Bam DS, Malla P. Control of tuberculosis in an urban setting in Nepal: public-private partnership. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:92–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Newell JN, Pande S, Baral S, Bam D, Malla P. Leadership, management and technical lessons learnt from a successful public-private partnership for TB control in Nepal. Int J Tuberculosis Lung Disease. 2005;9(9):1013–1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Njau R, Mosha F, De Savigny D. Case studies in public-private-partnership in health with the focus of enhancing the accessibility of health interventions. Tanzan J Health Res. 2009;11(4):235–49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Pal R, Pal S. Primary health care and public-private partnership: an indian perspective. Ann Tropical Med Public Health. 2009;2(2):46. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pérez-Escamilla R. Innovative Healthy Lifestyles School-Based Public–Private Partnerships Designed to Curb the Childhood Obesity Epidemic Globally: Lessons Learned From the Mondelēz International Foundation. Food Nutrition Bulletin. 2018;39(1_suppl):S3–S21. doi: 10.1177/0379572118767690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perry CL, Hoelscher DM, Kohl HW., III Research contributions on childhood obesity from a public-private partnership. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12(1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-12-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Quy H, Lan N, Lönnroth K, Buu T, Dieu T, Hai L. Public-private mix for improved TB control in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: an assessment of its impact on case detection. Int J Tuberculosis Lung Disease. 2003;7(5):464–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramiah I, Reich MR. Building effective public–private partnerships: experiences and lessons from the African comprehensive HIV/AIDS partnerships (ACHAP) Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(2):397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rangan S, Juvekar S, Rasalpurkar S, Morankar S, Joshi A, Porter J. Tuberculosis control in rural India: lessons from public-private collaboration. Int J Tuberculosis Lung Disease. 2004;8(5):552–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reviono R, Setianingsih W, Damayanti KE, Ekasari R. The dynamic of tuberculosis case finding in the era of the public–private mix strategy for tuberculosis control in Central Java, Indonesia. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1353777. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1353777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ribeiro CA, Vilma A, Medeiros KAB, de Araúo Morais KM. Public-private Partnership in the Prevention of influenza amongst industry Workers in Ceara State. Eur J Sustainable Development. 2016;5(3):527–531. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sheikh K, Porter J, Kielmann K, Rangan S. Public-private partnerships for equity of access to care for tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS: lessons from Pune, India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100(4):312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Silk H, Gusha J, Adler B, Sachs Leicher E, Finison LJ, Huppert ME, et al. The Central Massachusetts Oral health initiative (CMOHI): a successful public–private community health collaboration. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70(4):308–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silow-Carroll S. Iowa's 1st five initiative: improving early childhood developmental services through public-private partnerships: commonwealth fund. 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singh A, Mavalankar DV, Bhat R, Desai A, Patel S, Singh PV, et al. Providing skilled birth attendants and emergency obstetric care to the poor through partnership with private sector obstetricians in Gujarat, India. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:960–964. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.060228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tanzil S, Zahidie A, Ahsan A, Kazi A, Shaikh BT. A case study of outsourced primary healthcare services in Sindh, Pakistan: is this a real reform? BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):277. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ullah ANZ, Huque R, Husain A, Akter S, Islam A, Newell JN. Effectiveness of involving the private medical sector in the national TB control Programme in Bangladesh: evidence from mixed methods. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6):e001534. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uplekar M. Involving private health care providers in delivery of TB care: global strategy. Tuberculosis. 2003;83(1–3):156–164. doi: 10.1016/S1472-9792(02)00073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Uplekar M. Public-private mix for tuberculosis care and prevention. What progress? What prospects? Int J Tuberculosis Lung Disease. 2016;20(11):1424–1429. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van de Vijver S, Oti S, Cohen Tervaert T, Hankins C, Kyobutungi C, Gomez GB, et al. Introducing a model of cardiovascular prevention in Nairobi's slums by integrating a public health and private-sector approach: the SCALE-UP study. Glob Health Action. 2013;6(1):22510. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.22510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zafar Ullah A, Newell JN, Ahmed JU, Hyder M, Islam A. Government–NGO collaboration: the case of tuberculosis control in Bangladesh. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21(2):143–155. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czj014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.World Health Organization ,Global TB Programme ,20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva, Switzerland.

- 72.Whyle EB, Olivier J. Models of public–private engagement for health services delivery and financing in southern Africa: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(10):1515–1529. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shaikh B, Rabbani F, Safi N, Dawar Z. Contracting of primary health care services in Pakistan: is up-scaling a pragmatic thinking. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60(5):387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carlsson G, Nordström A. Global engagement for health could achieve better results now and after 2015. Lancet. 2012;380(9853):1533–1534. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61809-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Minow M. Public and private partnerships: accounting for the new religion. Harvard Law Review. 2003;116(5):1229–1270. doi: 10.2307/1342726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bloomfield P. The challenging business of long-term public–private partnerships: reflections on local experience. Public Adm Rev. 2006;66(3):400–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00597.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Doshmangir L, Moshiri E, Farzadfar F. Seven decades of primary healthcare during various development plans in Iran: a historical review. Archives Iranian Med. 2020;23(5):338–352. doi: 10.34172/aim.2020.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rajabi F, Esmailzadeh H, Rostamigooran N, Majdzadeh R, Doshmangir L. Future of health care delivery in Iran, opportunities and threats. Iranian J Public Health. 2013;42(Supple1):23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mitchell M. An overview of public private partnerships in health. International Health Systems Program Publication, Harvard School of Public Health. 2008.

- 80.Malmborg R, Mann G, Thomson R, Squire SB. Can public-private collaboration promote tuberculosis case detection among the poor and vulnerable? Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:752–758. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Widdus R. Public-private partnerships for health require thoughtful evaluation: SciELO Public Health; 2003. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Alexander N, Rowe S, Brackett RE, Burton-Freeman B, Hentges EJ, Kretser A, et al. Achieving a transparent, actionable framework for public-private partnerships for food and nutrition research. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(6):1359–1363. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.112805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.