Abstract

The AAA+ protein disaggregase, Hsp104, increases fitness under stress by reversing stress-induced protein aggregation. Natural Hsp104 variants might exist with enhanced, selective activity against neurodegenerative disease substrates. However, natural Hsp104 variation remains largely unexplored. Here, we screened a cross-kingdom collection of Hsp104 homologs in yeast proteotoxicity models. Prokaryotic ClpG reduced TDP-43, FUS, and α-synuclein toxicity, whereas prokaryotic ClpB and hyperactive variants were ineffective. We uncovered therapeutic genetic variation among eukaryotic Hsp104 homologs that specifically antagonized TDP-43 condensation and toxicity in yeast and TDP-43 aggregation in human cells. We also uncovered distinct eukaryotic Hsp104 homologs that selectively antagonized α-synuclein condensation and toxicity in yeast and dopaminergic neurodegeneration in C. elegans. Surprisingly, this therapeutic variation did not manifest as enhanced disaggregase activity, but rather as increased passive inhibition of aggregation of specific substrates. By exploring natural tuning of this passive Hsp104 activity, we elucidated enhanced, substrate-specific agents that counter proteotoxicity underlying neurodegeneration.

Research organism: C. elegans, S. cerevisiae

Introduction

Alternative protein folding and aberrant phase transitions underpin fatal neurodegenerative diseases (Chuang et al., 2018; Mathieu et al., 2020). Diseases such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) have distinct clinical manifestations but are united by the prominent pathological accumulation of misfolded protein conformers (Peng et al., 2020). The proteins implicated in each disease can adopt a range of misfolded conformations (Peng et al., 2020; Shorter, 2017). Thus, in PD, alpha-synuclein (αSyn) accumulates in toxic soluble oligomers and amyloid fibers that are a major component of cytoplasmic Lewy bodies in degenerating dopaminergic neurons (Gallegos et al., 2015; Gitler and Shorter, 2007; Kim et al., 2014b; Recasens and Dehay, 2014; Snead and Eliezer, 2014). Likewise, in ALS, the normally nuclear RNA-binding proteins, TDP-43 and FUS, accumulate in toxic oligomeric structures and cytoplasmic inclusions in different forms of disease (Gitler and Shorter, 2011; Johnson et al., 2009; Ling et al., 2013; March et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2011).

Protein disaggregation represents an innovative and appealing therapeutic strategy for the treatment of protein-misfolding disorders in that it simultaneously reverses: (a) loss-of-function phenotypes associated with sequestration of functional soluble protein into misfolded oligomers and insoluble aggregates; and (b) any toxic gain-of-function phenotypes associated with the misfolded conformers themselves (March et al., 2019; Shorter, 2008; Vashist et al., 2010). The AAA+ (ATPases Associated with diverse Activities) protein Hsp104 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ScHsp104) rapidly disassembles a diverse range of misfolded protein conformers, including amorphous aggregates, preamyloid oligomers, and amyloid fibers (DeSantis et al., 2012; DeSantis and Shorter, 2012b; Glover and Lindquist, 1998; Liu et al., 2011; Lo Bianco et al., 2008; Shorter and Lindquist, 2004; Shorter and Lindquist, 2006; Shorter and Southworth, 2019; Sweeny and Shorter, 2016). Hsp104 assembles into asymmetric ring-shaped hexamers that undergo conformational changes upon ATP binding and hydrolysis, which drive substrate translocation across the central channel to power protein disaggregation (DeSantis et al., 2012; Gates et al., 2017; Michalska et al., 2019; Shorter and Southworth, 2019; Sweeny and Shorter, 2016; Ye et al., 2019; Yokom et al., 2016). Each protomer is comprised of an N-terminal domain (NTD), nucleotide-binding domain 1 (NBD1), a middle domain (MD), NBD2, and a short C-terminal domain (Shorter and Southworth, 2019; Sweeny and Shorter, 2016). Hsp104 can disassemble preamyloid oligomers and amyloid conformers of several proteins associated with neurodegenerative disease, including αSyn, polyglutamine, amyloid-beta, and tau (DeSantis et al., 2012; Lo Bianco et al., 2008). Moreover, these protein-remodeling events result in neuroprotection. For example, Hsp104 suppresses protein-misfolding-induced neurodegeneration in rat and D. melanogaster models of polyglutamine-expansion disorders (Cushman-Nick et al., 2013; Vacher et al., 2005), and a rat model of Parkinson’s disease (Lo Bianco et al., 2008). Hsp104 is the only factor known to eliminate αSyn fibers and oligomers in vitro, and prevent αSyn-mediated dopaminergic neurodegeneration in rats (Lo Bianco et al., 2008). However, these activities have limits and high concentrations of Hsp104 can be required for modest levels of protein remodeling (DeSantis et al., 2012; Jackrel et al., 2014; Lo Bianco et al., 2008).

Previously, we circumvented limitations on Hsp104 disaggregase activity by developing a suite of potentiated Hsp104 variants, differing from wild-type (WT) Hsp104 by one or more missense mutations in the autoregulatory MD (Jackrel and Shorter, 2015). These potentiated Hsp104 variants antagonize proteotoxic misfolding of several disease-linked proteins, including TDP-43, FUS, TAF15, FUS-CHOP, EWS-FLI, polyglutamine, and αSyn (Jackrel et al., 2014; Jackrel and Shorter, 2014; Jackrel et al., 2015; Michalska et al., 2019; Ryan et al., 2019; Sweeny et al., 2020; Tariq et al., 2018; Yasuda et al., 2017). However, in some circumstances, these Hsp104 variants can also exhibit off-target toxicity (Jackrel et al., 2014; Jackrel and Shorter, 2014; Jackrel et al., 2015). Thus, uncovering other therapeutic Hsp104s with diminished propensity for off-target effects is a key objective (Mack et al., 2020; Tariq et al., 2019).

Hsp104 is conserved among all non-metazoan eukaryotes and eubacteria, and is also found in some archaebacteria (Erives and Fassler, 2015; Sweeny and Shorter, 2016). We have found that prokaryotic Hsp104 homologs exhibit reduced amyloid-remodeling activity compared to eukaryotic homologs (Castellano et al., 2015; DeSantis et al., 2012; Michalska et al., 2019; Shorter and Lindquist, 2004; Sweeny and Shorter, 2016). Nonetheless, natural Hsp104 sequence space remains largely unexplored. This lack of exploration raises the possibility that natural Hsp104 sequences may exist with divergent enhanced and selective activity against neurodegenerative disease substrates. Indeed, we reported that an Hsp104 homolog from the thermophilic fungus Calcarisporiella thermophila antagonizes toxicity of TDP-43, αSyn, and polyglutamine in yeast without apparent toxic off-target effects (Michalska et al., 2019). These findings support our hypothesis that natural Hsp104 homologs may have therapeutically beneficial properties.

Here, we survey a cross-kingdom collection of Hsp104 homologs from diverse lineages for their ability to suppress proteotoxicity from several proteins implicated in human neurodegenerative disease. We discovered that prokaryotic ClpB and hyperactive variants were ineffective, but prokaryotic ClpG could mitigate TDP-43, FUS, and α-synuclein toxicity. Several eukaryotic Hsp104 homologs emerged that selectively suppressed TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity. Mechanistic studies and mutational analysis suggest that these selective activities are not due to enhanced disaggregase activity. Rather, they are due to genetic variation that impacts a passive, aggregation-inhibition activity of Hsp104 homologs for select substrates. Thus, we establish that manipulating passive aggregation-inhibition activity of Hsp104 represents a novel route to enhanced, substrate-specific agents able to counter the deleterious protein misfolding that underlies neurodegenerative disease.

Results

Diverse Hsp104 homologs selectively suppress TDP-43 toxicity and aggregation in yeast

In yeast, galactose-inducible expression of several proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases, including αSyn (Outeiro and Lindquist, 2003), TDP-43 (Johnson et al., 2008), and FUS (Sun et al., 2011) results in their cytoplasmic aggregation and toxicity. These yeast models have proven to be powerful platforms that have enabled the discovery of several important genetic and small-molecule modifiers of disease protein aggregation and toxicity. Importantly, these modifiers have translated to more complex model systems including worm, fly, mouse, and neuronal models of neurodegenerative disease (Armakola et al., 2012; Barmada et al., 2015; Becker et al., 2017; Caraveo et al., 2014; Caraveo et al., 2017; Chung et al., 2013; Cooper et al., 2006; Dhungel et al., 2015; Elden et al., 2010; Fanning et al., 2019; Gitler et al., 2009; Jackrel et al., 2014; Jackson et al., 2015; Ju et al., 2011; Khurana et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2014a; Nuber et al., 2020; Su et al., 2010; Tardiff et al., 2013; Tardiff et al., 2012; Vincent et al., 2018). Indeed, potential therapeutics for ALS (e.g. ataxin 2 antisense oligonucleotide, ION541/BIIB105) and PD (e.g. stearoyl-CoA-desaturase inhibitor, YTX-7739) that have emerged from these studies are now entering phase 1 clinical trials. Coexpression of potentiated Hsp104 variants mitigates αSyn, TDP-43, and FUS toxicity in yeast (Jackrel et al., 2014; Jackrel et al., 2015; Tariq et al., 2019; Tariq et al., 2018). Moreover, the natural homolog Calcarisporiella thermophila Hsp104 (CtHsp104), but not ScHsp104, reduces TDP-43 and αSyn toxicity in yeast (Michalska et al., 2019).

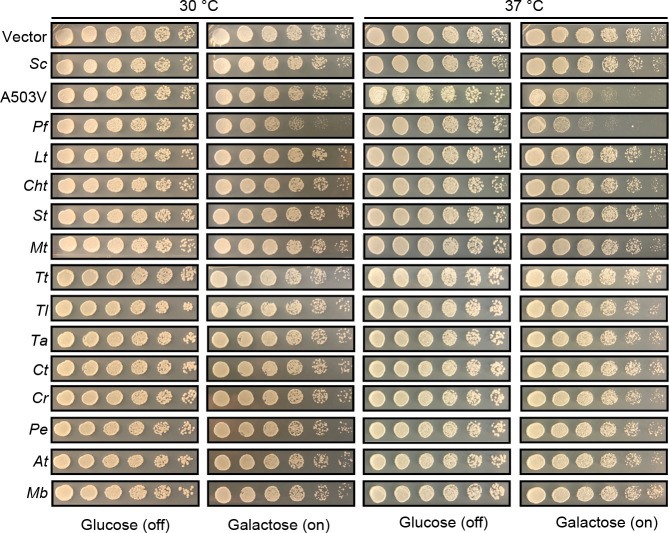

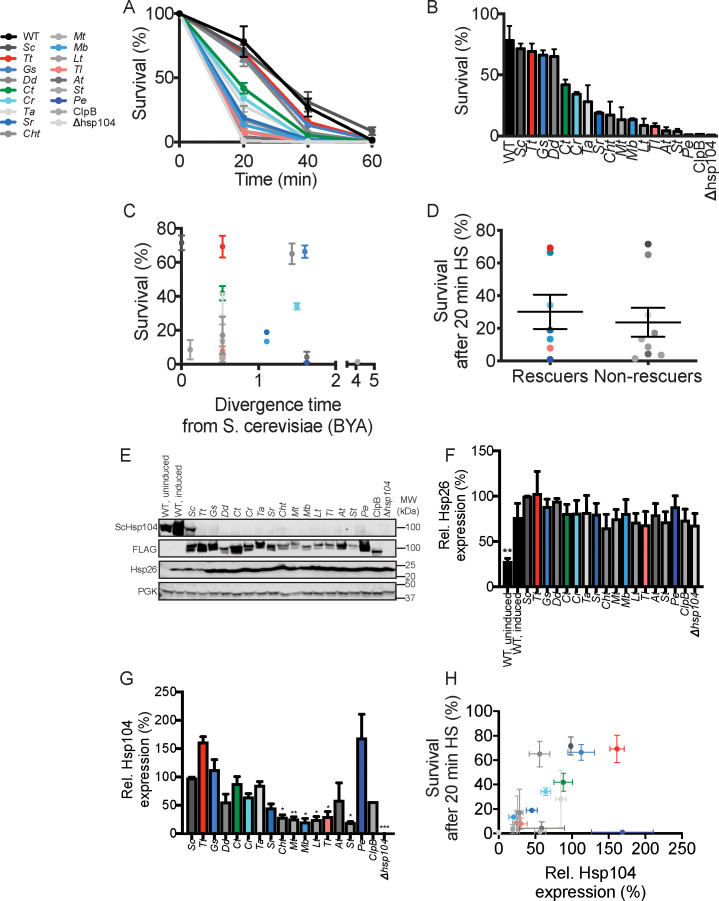

For a deeper exploration of natural Hsp104 sequence space, we screened a collection of 15 additional Hsp104 homologs from diverse eukaryotes spanning ~2 billion years of evolution and encompassing fungi (Thielavia terrestris, Thermomyces lanuginosus, Dictyostelium discoideum, Chaetomium thermophilum, Lachancea thermotolerans, Myceliophthora thermophila, Scytalidium thermophilum, and Thermoascus aurantiacus), plants (Arabidopsis thaliana and Populus euphratica), protozoa (Monosiga brevicollis, Salpingoeca rosetta, and Plasmodium falciparum), and chromista (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Galdieria sulphuraria) (Figure 1A; see Supplementary file 1 for homolog sequences, Figure 1—figure supplement 1 for an alignment of all homologs). All Hsp104 homologs, except the homolog from Plasmodium falciparum (Pf), were non-toxic to yeast at 30°C or 37°C (Figure 1—figure supplement 2). PfHsp104 was even more toxic than the potentiated Hsp104 variant, Hsp104A503V, at 37°C (Figure 1—figure supplement 2). This toxicity might reflect the very different role played by PfHsp104 in its host where it is not a soluble protein disaggregase. Rather, PfHsp104 has been repurposed as a key component of a membrane-embedded translocon, which transports malarial proteins across a parasite-encasing vacuolar membrane into erythrocytes (Bullen et al., 2012; de Koning-Ward et al., 2009; Ho et al., 2018).

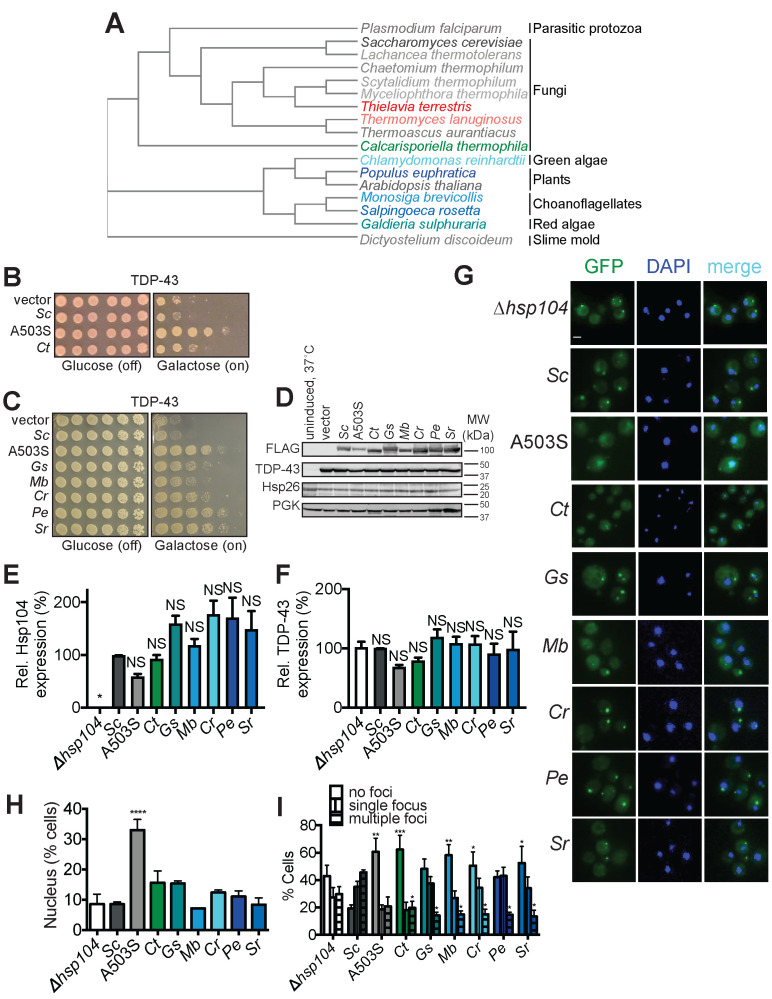

Figure 1. Diverse Hsp104 homologs suppress TDP-43 toxicity in yeast.

(A) Phylogenetic tree constructed using EMBL-EBI Simple Phylogeny tool from a multiple sequence alignment of the indicated Hsp104 homologs generated in Clustal Omega (see also Supplemental Information for alignments) showing evolutionary relationships between Hsp104 homologs studied in this paper. C. thermophila is in green, TDP-43-specific homologs are colored in shades of blue, αSyn-specific homologs are colored in red, and non-rescuing homologs are colored in shades of gray. (B) Δhsp104 yeast transformed with plasmids encoding galactose-inducible TDP-43 and the indicated galactose-inducible Hsp104 (either wild-type Hsp104 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the potentiated variant A503S, or the Hsp104 homolog from Calcarisporiella thermophila (Ct)) were serially diluted 5-fold and spotted onto glucose (expression off) or galactose (expression on). (C) Δhsp104 yeast transformed with plasmids encoding galactose-inducible TDP-43 and the indicated galactose-inducible Hsp104 (either wild-type Hsp104 from S. cerevisiae, the potentiated variant A503S, or homologs from Galdieria sulphuraria (Gs), Monosiga brevicollis (Mb), Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Cr), Populus euphratica (Pe), and Salpingoeca rosetta (Sr)) were serially diluted 5-fold and spotted onto glucose (expression off) or galactose (expression on). (D) Western blots confirm consistent expression of FLAG-tagged Hsp104s and proteotoxic protein substrates in yeast, and that neither Hsp104 expression nor TDP-43 expression induces upregulation of the endogenous heat-shock protein Hsp26. The first lane are isogenic yeast that have not been grown in galactose to induce Hsp104 and TDP-43 expression but instead have been pretreated at 37°C for 30 min to upregulate endogenous heat-shock proteins. 3-phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) is used as a loading control. Molecular weight markers are indicated (right). (E) Expression of the indicated Hsp104-FLAG relative to PGK was quantified for each strain. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare expression of ScHsp104-FLAG (Sc) to all other conditions. *p<0.05; NS, not significant. (F) TDP-43 expression relative to PGK was quantified for each strain. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare TDP-43 levels in the ∆hsp104 control to all other conditions. NS, not significant. (G) Representative images of yeast co-expressing TDP-43-GFPS11 (and separately GFPS1-10 to promote GFP reassembly) and the indicated Hsp104 homologs. Cells were stained with DAPI to visualize nuclei (blue). Scale bar, 2.5 µm. (H) Quantification of cells where TDP-43 displays nuclear localization. Values represent means ± SEM (n = 3 trials with >200 cells counted per trial). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare Δhsp104 to all other conditions. ****p<0.0001. (I) Quantification of cells with no, single, or multiple TDP-43 foci. Values represent means ± SEM (n = 3). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare the proportion of cells with either no or multiple TDP-43 foci between strains expressing different Hsp104 homologs and a control strain expressing ScHsp104. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

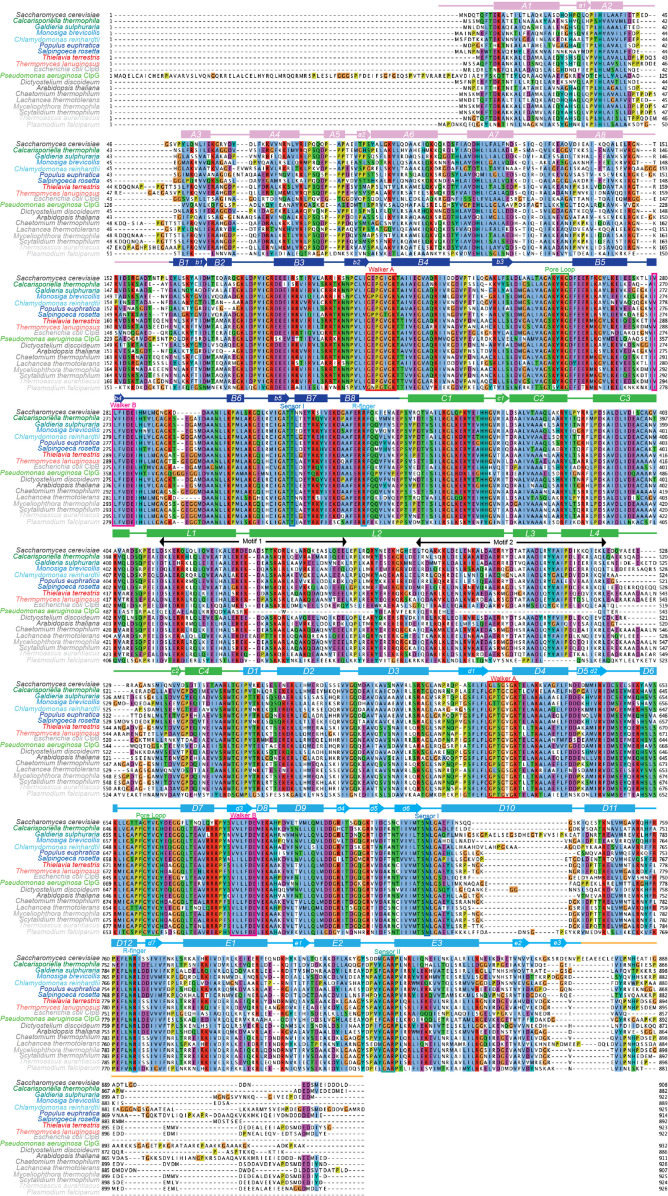

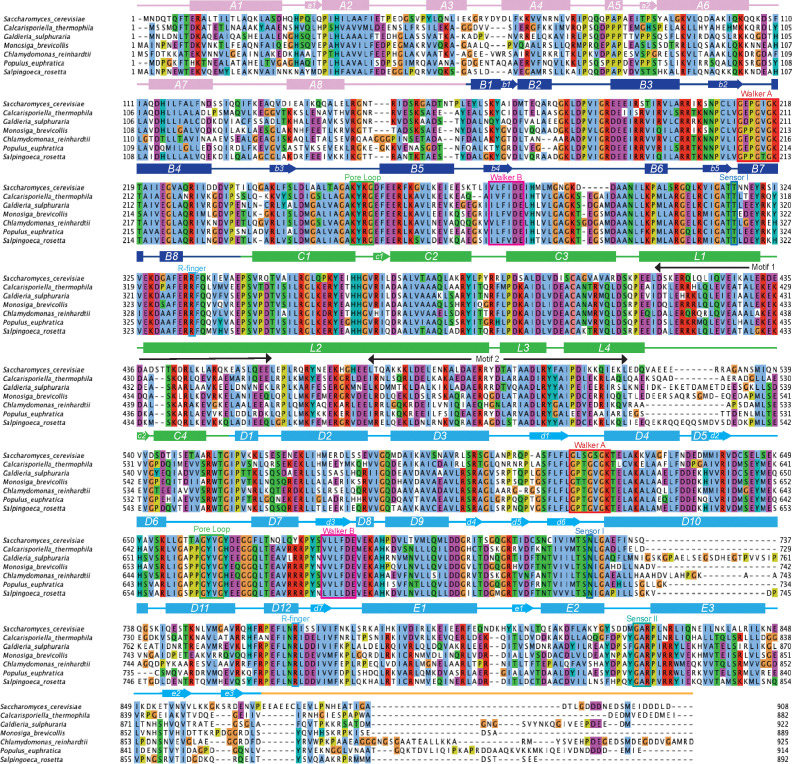

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Alignment of all Hsp104 homologs investigated in this study.

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. Hsp104 homologs do not typically induce temperature-dependent toxicity.

Figure 1—figure supplement 3. Suppression of TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity by select Hsp104 homologs is a substrate-specific effect.

Figure 1—figure supplement 4. Alignment comparing ScHsp104 to Hsp104 homologs that rescue TDP-43 toxicity.

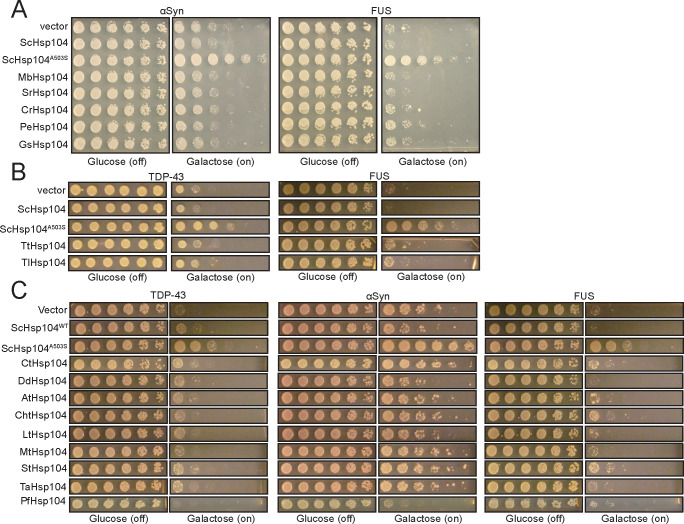

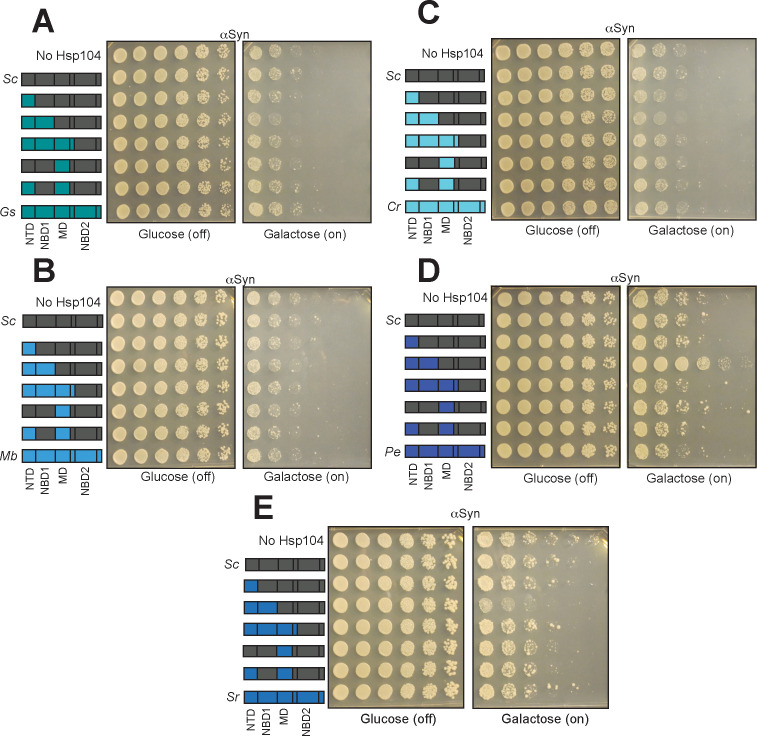

We screened the Hsp104 homologs for suppression of TDP-43, FUS, and αSyn proteotoxicity (Figures 1B,C and 2A,B, and Figure 1—figure supplement 3). The toxic Hsp104 homolog, PfHsp104, was unable to reduce TDP-43, FUS, and αSyn proteotoxicity (Figure 1—figure supplement 3C). By contrast, in addition to CtHsp104, which suppresses TDP-43 and αSyn toxicity (Figures 1B and 2A), five of these eukaryotic homologs (from protozoa: Monosiga brevicollis (Mb) and Salpingoeca rosetta (Sr), from chromista: Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Cr) and Galdieria sulphuraria (Gs), and the plant Populus euphratica (Pe)), suppress TDP-43 toxicity (Figure 1C; see Figure 1—figure supplement 4 for an alignment comparing TDP-43-rescuing homologs to ScHsp104). Interestingly, the Hsp104 homologs that suppress TDP-43 toxicity have minimal effect on αSyn and FUS toxicity (Figure 1—figure supplement 3A). Thus, we describe the first natural or engineered Hsp104 variants that diminish TDP-43 toxicity in a substrate-specific manner.

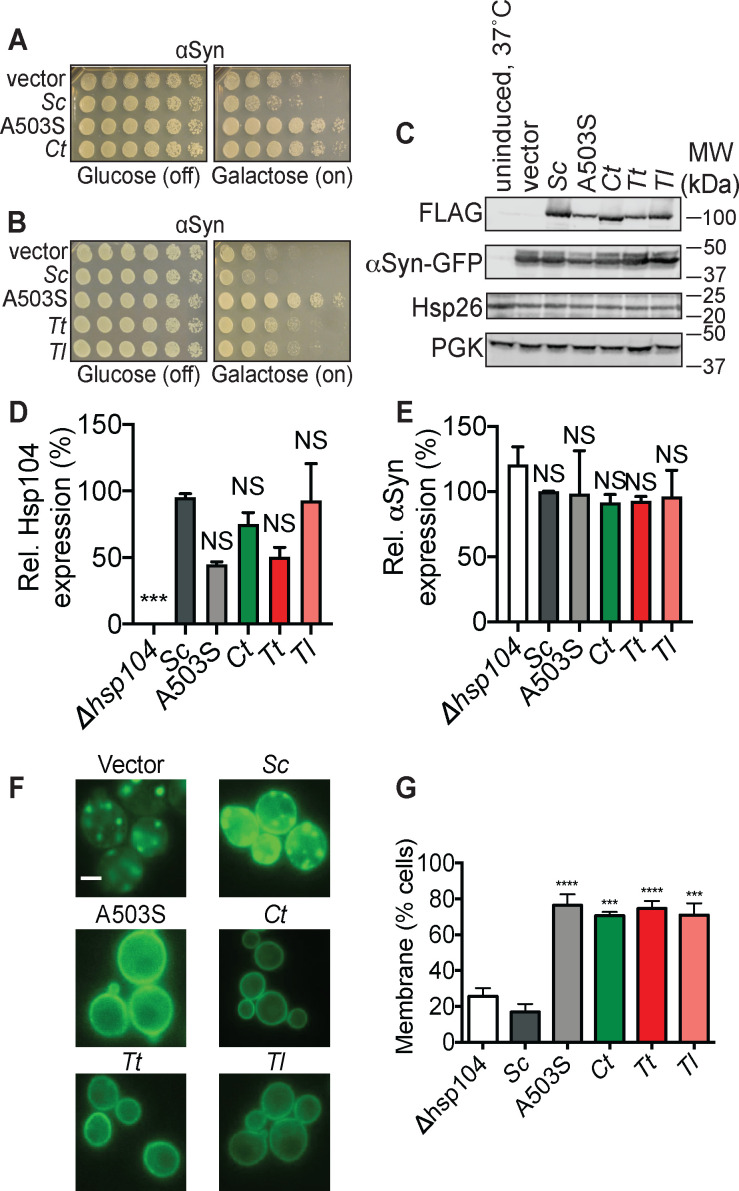

Figure 2. Hsp104 homologs from thermophilic fungi suppress αSyn toxicity in yeast.

(A) Δhsp104 yeast transformed with plasmids encoding galactose-inducible αSyn and the indicated galactose-inducible Hsp104 (either wild-type Hsp104 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the potentiated variant A503S, or the Hsp104 homolog from Calcarisporiella thermophila (Ct)) were serially diluted 5-fold and spotted onto glucose (expression off) or galactose (expression on). (B) Δhsp104 yeast transformed with plasmids encoding galactose-inducible αSyn and the indicated galactose-inducible Hsp104 (either wild-type Hsp104 from S. cerevisiae, the potentiated variant A503S, or homologs from Thielavia terrestris (Tt), and Thermomyces lanuginosus (Tl)) were serially diluted 5-fold and spotted onto glucose (expression off) or galactose (expression on). (C) Western blots confirm consistent expression of FLAG-tagged Hsp104s and proteotoxic protein substrates in yeast, and that neither Hsp104 expression nor αSyn-GFP expression induces upregulation of the endogenous heat-shock protein Hsp26. The first lane are isogenic yeast that have not been grown in galactose to induce Hsp104 and αSyn expression but instead have been pretreated at 37°C for 30 min to upregulate heat-shock proteins. PGK is used as a loading control. Molecular weight markers are indicated (right). (D) Expression of the indicated Hsp104-FLAG relative to PGK was quantified for each strain. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare expression of ScHsp104-FLAG (Sc) to all other conditions. ***p<0.001; NS, not significant. (E) αSyn-GFP expression relative to PGK was quantified for each strain. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare αSyn-GFP levels the ∆hsp104 control to all other conditions. NS, not significant. (F–G) Fluorescence microscopy of cells coexpressing αSyn-GFP and vector, ScHsp104WT, ScHsp104A503S, CtHsp104, TtHsp104, or TlHsp104. Scale bar, 2.5 µm. αSyn localization was quantified as the number of cells with fluorescence at the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic inclusions. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3 trials with >200 cells counted per trial). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare Δhsp104 to all other conditions. ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001.

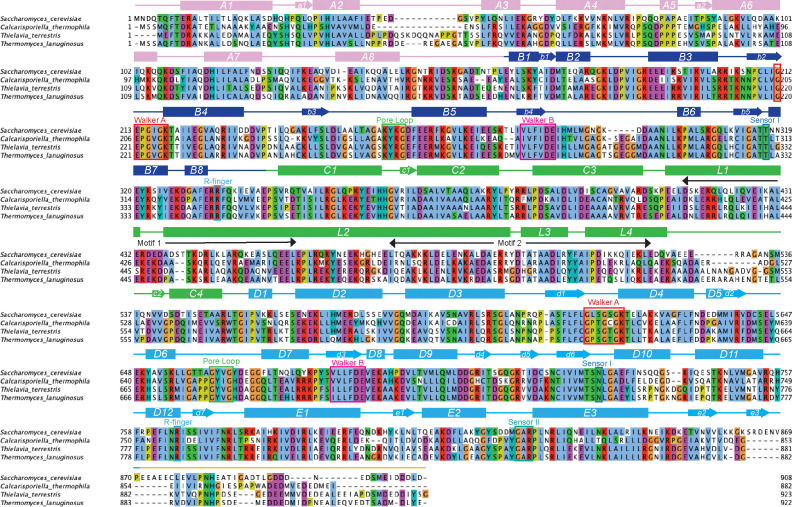

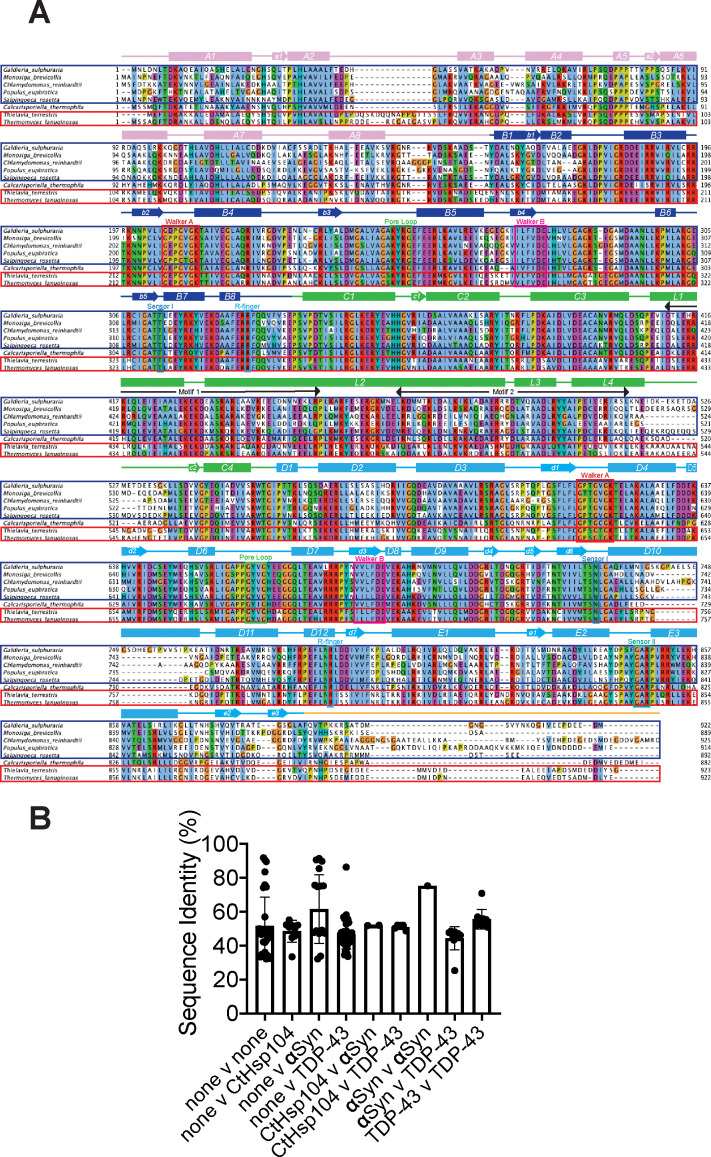

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Alignment comparing ScHsp104 to Hsp104 homologs that rescue αSyn toxicity.

Figure 2—figure supplement 2. Alignment comparing Hsp104 homologs that rescue TDP-43 toxicity to those that rescue αSyn toxicity.

Figure 2—figure supplement 3. ClpGGI robustly suppresses αSyn toxicity and confers thermotolerance to Δhsp104 yeast, whereas ClpB and hyperactive variants do not.

Expression of Hsp104 homologs did not vary significantly, nor did they significantly affect TDP-43 levels (Figure 1D–F), indicating that suppression of toxicity was not due to reduced TDP-43 expression. Moreover, levels of the small heat-shock protein, Hsp26, were similar in all strains and lower than in control strains that had been pretreated at 37°C to mount a heat-shock response (HSR) (Cashikar et al., 2005). Thus, expression of heterologous Hsp104s does not indirectly suppress TDP-43 toxicity by inducing a yeast HSR (Figure 1D).

Next, we examined how these Hsp104 homologs affect TDP-43 localization in our yeast model. In human cells, TDP-43 normally shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm, but in ALS, TDP-43 becomes mislocalized to cytoplasmic inclusions (Neumann et al., 2006). Expression of GFP-tagged TDP-43 (TDP43-GFP) in yeast recapitulates this phenotype (Figure 1G,H; Johnson et al., 2008; Johnson et al., 2009). Consistent with previous observations, expression of ScHsp104 does not affect TDP43-GFP cytoplasmic localization (Figure 1H) but slightly exacerbates formation of TDP43-GFP foci (Figure 1I). By contrast, the potentiated variant, Hsp104A503S, restores nuclear TDP-43 localization in ~40% of cells (Jackrel et al., 2014; Jackrel and Shorter, 2014; Figure 1H) and suppresses TDP-43 foci formation (Figure 1I). Cells expressing Hsp104 homologs that suppress TDP-43 toxicity (e.g. Ct, Gs, Mb, Cr, Pe, and Sr), show at most a modest increase in nuclear TDP43-GFP compared to control strains lacking Hsp104 (Δhsp104) or expressing ScHsp104 (Figure 1H). However, formation of cytoplasmic TDP43-GFP foci is suppressed by all these homologs (Figure 1I). Thus, TDP-43 toxicity can be mitigated in yeast by limiting TDP-43 inclusion formation without restoring nuclear localization. Indeed, PeHsp104 and SrHsp104 reduced TDP-43 toxicity as effectively as Hsp104A503S, but without restoring TDP-43 to the nucleus (Figure 1C,H).

Distinct Hsp104 homologs selectively suppress αSyn toxicity and inclusion formation in yeast

In addition to the five Hsp104 homologs that suppress TDP-43 toxicity, we discovered two new Hsp104 homologs (from Thielavia terrestris (Tt) and Thermomyces lanuginosus (Tl)) that suppress αSyn toxicity (Figure 2B; see Figure 2—figure supplement 1 for an alignment comparing αSyn-rescuing homologs to ScHsp104 and Figure 2—figure supplement 2 for an alignment comparing TDP-43-rescuing homologs to αSyn-rescuing homologs). Similar to the Hsp104 homologs that suppress TDP-43 toxicity, these Hsp104 homologs were selective and suppressed αSyn toxicity but had minimal effect on TDP-43 or FUS toxicity (Figure 1—figure supplement 3B). Eight of the fifteen Hsp104 homologs tested do not suppress TDP-43, αSyn, or FUS toxicity (Figure 1—figure supplement 3C). Expression of Hsp104 homologs did not vary significantly (Figure 2C,D). Hsp104 homologs suppressed αSyn toxicity without significantly affecting αSyn expression and without inducing an HSR as indicated by Hsp26 levels (Figure 2C,E).

We also examined how Hsp104 homologs that suppress αSyn toxicity affect αSyn localization in yeast. αSyn is a lipid-binding protein that mislocalizes to cytoplasmic Lewy bodies in Parkinson’s disease (Spillantini et al., 1997). Overexpression of αSyn in yeast recapitulates some aspects of this phenotype (Outeiro and Lindquist, 2003). Indeed, αSyn forms toxic cytoplasmic foci that are detergent-insoluble, contain high molecular weight α-syn oligomers, and cluster cytoplasmic vesicles akin to some aspects of Lewy pathology observed in PD patients (Araki et al., 2019; Fanning et al., 2020; Gitler et al., 2008; Jackrel et al., 2014; Jarosz and Khurana, 2017; Outeiro and Lindquist, 2003; Shahmoradian et al., 2019; Soper et al., 2008; Tenreiro et al., 2014). Cytoplasmic αSyn foci in yeast have also been reported to react with the amyloid-diagnostic dye, thioflavin-S (Franssens et al., 2010; Zabrocki et al., 2005). We observed that all Hsp104 homologs that suppress αSyn toxicity also restore αSyn localization to the plasma membrane in ~75% of cells (Figure 2F,G). Cells with membrane-localized αSyn showed no cytoplasmic αSyn foci (Figure 2F,G). Taken together, our results demonstrate that Hsp104 homologs that suppress TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity also suppress the formation of TDP-43 or αSyn inclusions.

Sequence characteristics of Hsp104 homologs

We next examined sequence relatedness among Hsp104 homologs in an effort to understand what sets Hsp104 homologs with particular toxicity-suppression characteristics apart. Hsp104 homologs with particular suppression characteristics cluster together phylogenetically (Figure 1A) although there are exceptions. Thus, while A. thaliana and P. euphratica are closely related species, AtHsp104 does not suppress TDP-43 toxicity while PeHsp104 does. We wondered whether Hsp104 homologs had particular sequence signatures that would predict their toxicity-suppression capacities. Multiple sequence alignments did not reveal any clear patterns to differentiate ScHsp104 from TDP-43-suppressing Hsp104s (Figure 1—figure supplement 4) or αSyn-suppressing Hsp104s (Figure 2—figure supplement 1). Similarly, there were no clear patterns differentiating TDP-43-suppressing Hsp104 homologs from αSyn-suppressing Hsp104 homologs (Figure 2—figure supplement 2A). We next calculated pairwise sequence identities between each possible pair of Hsp104 homologs (Supplementary file 2), and compared the average percent identity of pairs with similar and dissimilar toxicity-suppression profiles (Figure 2—figure supplement 2B). The mean pairwise identity between TtHsp104 and TlHsp104, which both suppress αSyn toxicity, was 76%, which was unsurprising given that these homologs are from two closely related species. The ten pairwise identities comparing Hsp104 homologs that both rescue TDP-43 had a mean of 56% (with range of 51–71%), while the ten pairwise identities comparing one Hsp104 homolog that suppresses TDP-43 to another that suppresses αSyn had a mean of 44% (with range of 25–49%). Thus, homologs that suppress TDP-43 or αSyn seem to be more similar to one another than between groups.

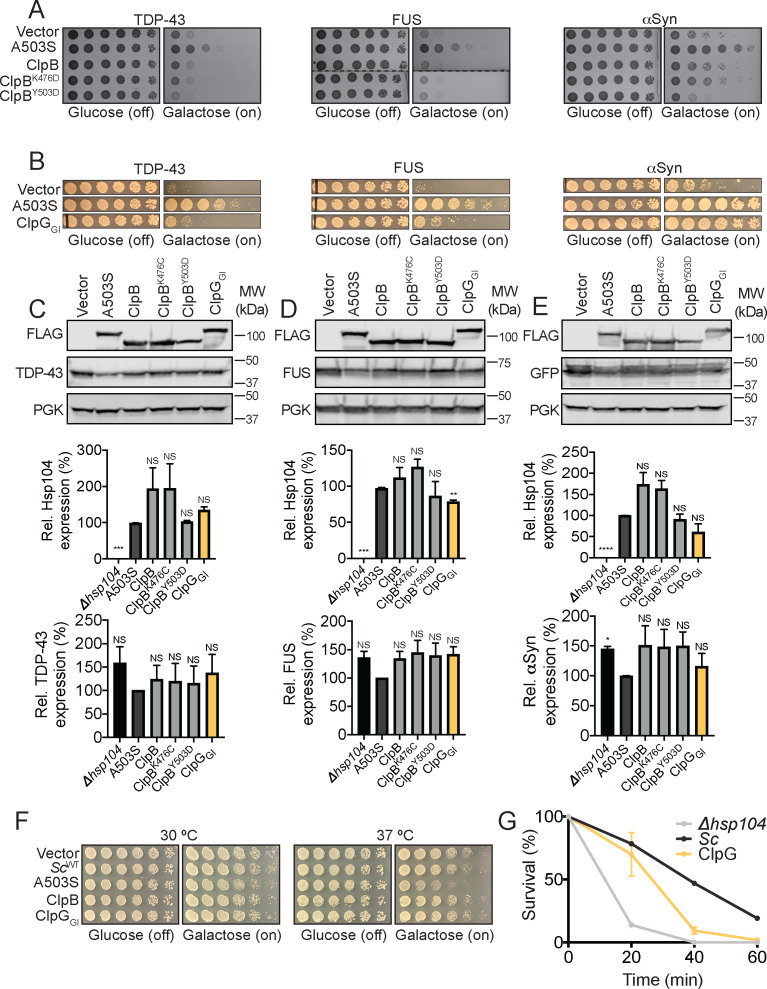

ClpGGI from Pseudomonas aeruginosa reduces TDP-43, FUS, and αSyn toxicity

In addition to the eukaryotic Hsp104 homologs discussed above, we also studied two prokaryotic Hsp104 homologs: ClpB from Escherichia coli and ClpGGI from the pathogenic bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa. WT ClpB does not suppress TDP-43, FUS, or αSyn toxicity (Figure 2—figure supplement 3A). We wondered whether ClpB activity could be enhanced via missense mutations in the MD, in analogy with Hsp104, so we also selected two previously-described hyperactive ClpB variants, ClpBK476D and ClpBY503D (Castellano et al., 2015; Oguchi et al., 2012; Rizo et al., 2019), to test for suppression of TDP-43, FUS, and αSyn toxicity. Neither ClpBK476D nor ClpBY503D suppressed TDP-43, FUS, or αSyn toxicity (Figure 2—figure supplement 3A). Thus, despite being able to exert forces of more than 50 pN and translocate polypeptides at speeds of more than 500 residues per second (Avellaneda et al., 2020), neither ClpB nor hyperactive ClpB variants are capable of suppressing TDP-43, FUS, or αSyn proteotoxicity in yeast.

Next, we tested ClpGGI, which bears significant homology to Hsp104 but is distinguished by an extended NTD and a shorter MD roughly corresponding to loss of MD Motif 2 (Lee et al., 2018; Figure 1—figure supplement 1). ClpGGI has been reported to be a more effective disaggregase than ClpB from E. coli (Katikaridis et al., 2019). Furthermore, we previously established that deleting Motif 2 from ScHsp104 yields a potentiated variant able to rescue TDP-43, FUS, or αSyn toxicity (Jackrel et al., 2015). Thus, we wondered whether ClpGGI might suppress TDP-43, FUS, or αSyn toxicity. Indeed, we found ClpGGI potently suppresses αSyn toxicity and slightly suppresses TDP-43 and FUS toxicity (Figure 2—figure supplement 3B). ClpB, ClpB variants, and ClpGGI all express robustly in yeast and do not affect TDP-43, FUS, or αSyn levels (Figure 2—figure supplement 3C–E). ClpB and ClpGGI are also not toxic to yeast when expressed at 37°C (Figure 2—figure supplement 3F). Thus, ClpGGI is a prokaryotic disaggregase with therapeutic properties and may represent a natural example of Hsp104 potentiation via loss of Motif 2 from the MD (Jackrel et al., 2015).

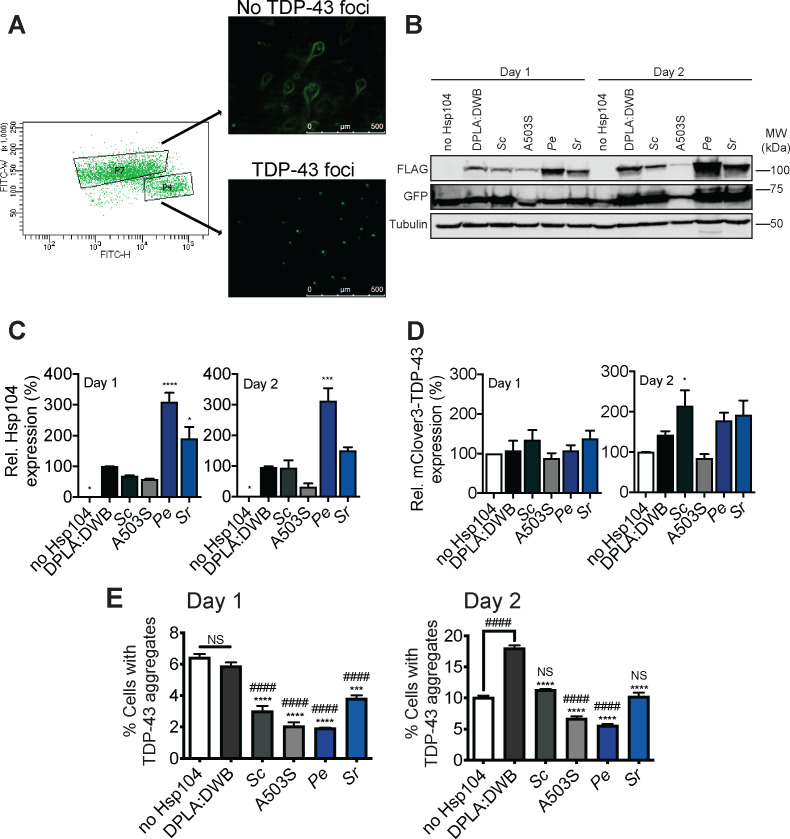

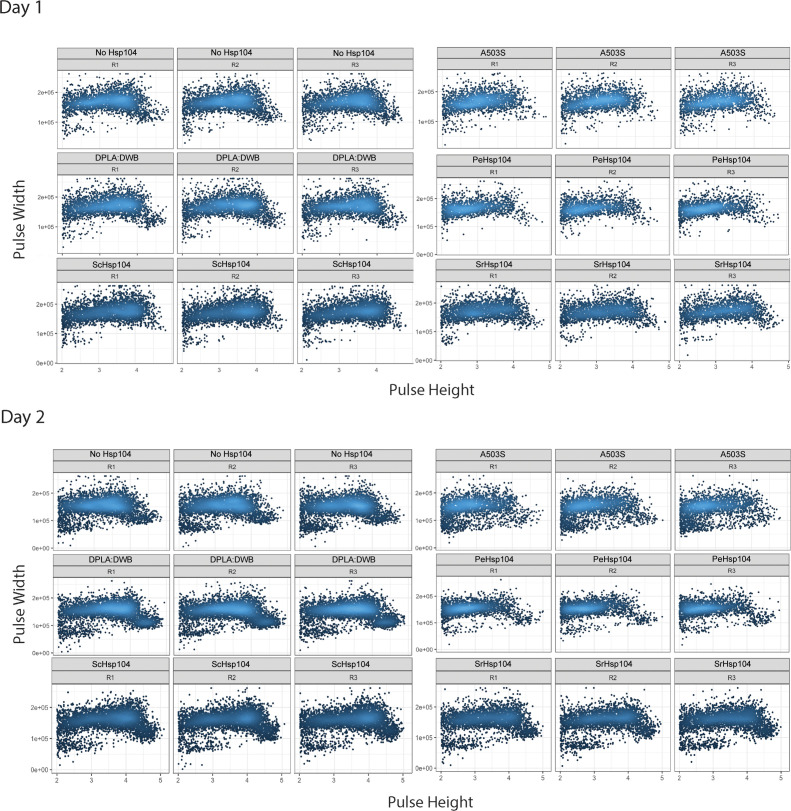

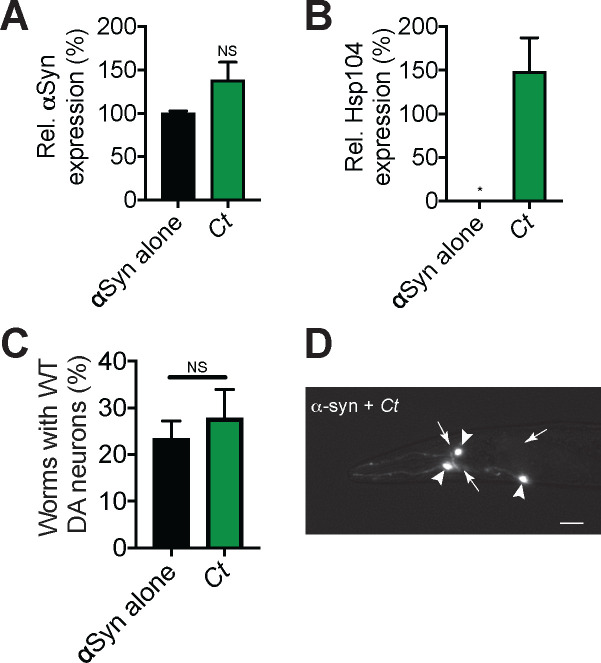

Hsp104 homologs prevent TDP-43 aggregation in human cells

We next examined whether Hsp104 homologs that suppress TDP-43 toxicity in yeast would have a beneficial effect in higher model systems. Expression of Hsp104 or potentiated variants in mammalian cells is well tolerated and can be cytoprotective (Bao et al., 2002; Carmichael et al., 2000; Mosser et al., 2004; Yasuda et al., 2017). Thus, we transfected human HEK293T cells with an inducible plasmid encoding fluorescently-tagged TDP-43 lacking a functional nuclear-localization sequence (mClover3-TDP43ΔNLS) to enhance cytoplasmic accumulation and aggregation (Guo et al., 2018; Winton et al., 2008). We co-transfected these cells with an empty vector or inducible plasmids encoding ScHsp104WT, the potentiated variant ScHsp104A503S, PeHsp104, SrHsp104, or a catalytically-inactive variant ScHsp104DPLA:DWB deficient in both peptide translocation (due to Y257A and Y662A mutations in NBD1 and NBD2 substrate-binding pore loops) and ATP hydrolysis (due to E285Q and E687Q mutations in NBD1 and NBD2 Walker B motifs) (DeSantis et al., 2012). PeHsp104 and SrHsp104 display the most potent and selective suppression of TDP-43 toxicity in yeast (Figure 1C). We monitored TDP-43 expression and aggregation by pulse-shape analysis of flow cytometry data (see Materials and methods) (Ramdzan et al., 2013) over time and quantified the percentage of cells bearing aggregates upon coexpression of each Hsp104 (Figure 3A, Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Expression of Hsp104 variants in HEK293T cells was confirmed by Western blot (Figure 3B,C). At both 24 hr and 48 hr post-transfection, PeHsp104 consistently accumulated to higher levels than other Hsp104 homologs (Figure 3B,C). We also monitored mClover3-TDP-43ΔNLS levels by Western blot (Figure 3B,D). None of the conditions tested led to significant reduction of TDP-43 expression (Figure 3B,D), although some conditions exhibited increased TDP-43 levels (Figure 3B,D). This finding suggests that Hsp104 variants do not merely affect accumulation of TDP-43 foci by reducing TDP-43 levels. At 24 hr post-transfection, all catalytically active Hsp104 variants significantly decreased the proportion of cells with TDP-43 aggregates compared to cells expressing no Hsp104 or cells expressing the catalytically-inactive ScHsp104DPLA:DWB (DeSantis et al., 2012; Figure 3E, left panel, Day 1). We were surprised that ScHsp104WT reduced the proportion of cells with TDP-43 aggregates at this time point, given that it does not reduce TDP-43 aggregation in yeast (Figure 1G; Figure 1I). However, at 48 hr post-transfection, cells expressing ScHsp104WT had a similar proportion of cells with TDP-43 aggregates as the vector control (Figure 3E, right panel, Day 2). By contrast, the catalytically-inactive variant ScHsp104DPLA:DWB had a significantly increased proportion of cells with TDP-43 aggregates compared to cells expressing no Hsp104 or ScHsp104WT (Figure 3E, right panel, Day 2). Strikingly, cells expressing the potentiated variant ScHsp104A503S or the TDP-43-specific variant PeHsp104 continued to show a significantly lower percentage of cells with TDP-43 aggregates (Figure 3E, right panel, Day 2). The TDP-43-specific variant SrHsp104, meanwhile, reduced TDP-43 aggregate burden at day 1 but not day 2, suggesting an intermediate effect (Figure 3E). Thus, while ScHsp104 and SrHsp104 show a short-lived suppression of TDP-43 foci formation, we define two Hsp104 variants, one engineered (A503S) and one natural (PeHsp104) that show an enduring reduction of TDP-43 foci in human cells.

Figure 3. Hsp104 homologs reduce TDP-43 aggregation in HEK293T cells.

(A) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with doxycycline-inducible constructs encoding mClover3-TDP-43ΔNLS. Protein expression was induced with 1 µg/ml doxycycline 6 hr post-transfection. At varying times, cells were sorted by FACS into populations lacking TDP-43 foci (P7) or cells with TDP-43 foci (P4). Representative fluorescent microscopy of sorted cells is shown at right. Scale bar, 500 µm. (B) At days 1 and 2 post-transfection, cells were processed for Western blot to confirm Hsp104-FLAG expression and mClover3-TDP-43ΔNLS (detected with a GFP antibody) expression. Tubulin is used as a loading control. Molecular weight markers are indicated (right). (C) Expression of the indicated Hsp104-FLAG relative to tubulin was quantified for each condition at day 1 (left) and day 2 (right) post-transfection. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare expression of DPLA:DWB to all other conditions. *p<0.01; ***p<0.001. (D) mClover3-TDP43ΔNLS expression relative to tubulin was quantified for each condition at day 1 (left) and day 2 (right) post-transfection. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare mClover3-TDP43ΔNLS levels in cells expressing no Hsp104 to all other conditions. *p<0.05. (E) At day 1 post-transfection, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to quantify cells bearing TDP-43 aggregates (E, left). Cells were also analyzed by flow cytometry at day 2 post-transfection (E, right) Values are means ± SEM (n = 3 independent transfections with 10,000 cells counted per trial). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare no Hsp104 (#) and DPLA:DWB (*) to all other conditions, and to each other. ###/***p<0.001; ####/****p<0.0001; NS, not significant.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Pulse-shape plots for HEK293T TDP-43ΔNLS co-transfection experiments.

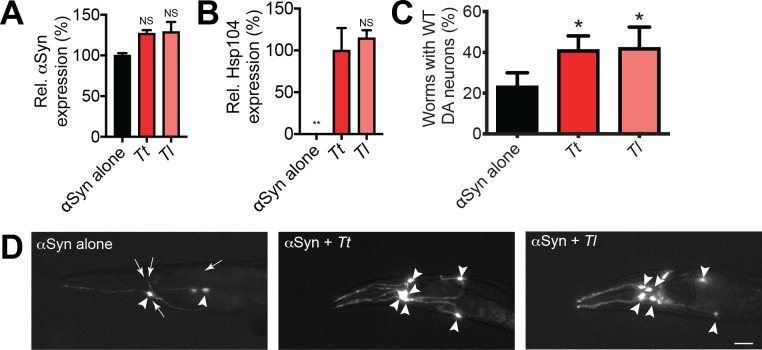

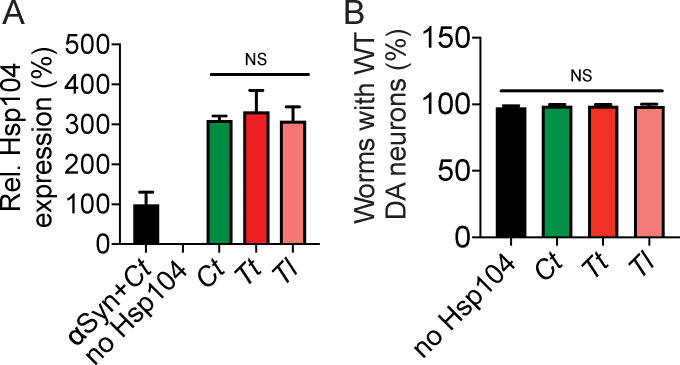

αSyn-selective Hsp104 homologs prevent dopaminergic neurodegeneration in C. elegans

To test whether TtHsp104, and TlHsp104, which selectively suppress αSyn toxicity in yeast, would likewise suppress αSyn toxicity in animals, we turned to a C. elegans model of Parkinson’s disease in which the dopamine transporter (dat-1) promoter is used to direct expression of αSyn to dopaminergic (DA) neurons (Cao et al., 2005). We generated transgenic worms expressing αSyn either alone or in combination with different Hsp104 variants in DA neurons, and confirmed Hsp104 and αSyn expression by qRT-PCR (Figure 4A,B). Only ~20% of worms expressing αSyn alone have a full complement of DA neurons at day 7 post-hatching (Figure 4C,D). WT Hsp104 from S. cerevisiae does not protect C. elegans DA neurons in this context (Jackrel et al., 2014). Coexpression of TtHsp104 or TlHsp104, which both selectively mitigate αSyn toxicity in yeast, both result in significant protection of DA neurons in C. elegans (~40% worms with normal DA neurons in each case) after 7 days post-hatching (Figure 4C,D). Additionally, Hsp104 homologs are not intrinsically toxic, as worms expressing DA neuron-localized Hsp104 homologs in the absence of αSyn have a full complement of neurons at 7 days post-hatching (Figure 4—figure supplement 1). The level of DA neuron protection conferred by TtHsp104 and TlHsp104 is comparable to that conferred by the potentiated Hsp104 variants, Hsp104A503S and Hsp104DPLF:A503V (Jackrel et al., 2014). Thus, our results demonstrate that natural, substrate-specific Hsp104 homologs can function in a wide variety of contexts, including in an intact animal nervous system.

Figure 4. Hsp104 homologs protect against αSyn-mediated dopaminergic neurodegeneration in C. elegans.

(A) qRT-PCR for the expression of αSyn and various Hsp104 homologs in transgenic C. elegans. αSyn expression was normalized to transgenic worms expressing αSyn alone. Values represent means ± SEM (N = 100 worms per transgenic line, three independent transgenic lines examined for each genotype). The expression of αSyn among all genotypes was not significantly different, as assessed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test to compare αSyn alone to all other conditions. (B) qRT-PCR for the expression of various Hsp104 homologs in transgenic C. elegans. Hsp104 expression was normalized to transgenic worms expressing both αSyn and TtHsp104 (Tt). Values represent means ± SEM (N = 100 worms per transgenic line, three independent transgenic lines examined for each genotype). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare TtHsp104 to all other conditions. **p<0.01; NS, not significant. (C) αSyn and the indicated Hsp104 homolog were coexpressed in the dopaminergic (DA) neurons of C. elegans. Hermaphrodite nematodes have six anterior DA neurons, which were scored at day seven posthatching. Worms are considered WT if they have all six anterior DA neurons intact (see methods for more details). TtHsp104 and TlHsp104 significantly protect dopaminergic neurons compared to αSyn alone. Values represent means ± SEM (n = 30 worms per genotype per replicate, three independent replicates). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare αSyn alone to all other conditions. *p<0.05. (D) Photomicrographs of the anterior region of C. elegans coexpressing GFP with αSyn. Worms expressing αSyn alone (left) exhibit an age-dependent loss of DA neurons. Worms expressing αSyn plus either Tt (middle) or Tl (right) exhibit greater neuronal integrity. Arrows indicate degenerating or missing neurons. Arrowheads indicate normal neurons. Scale bar, 10 µm.

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. Hsp104 homologs are not intrinsically toxic to C. elegans DA neurons.

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. CtHsp104 does not protect C. elegans DA neurons from αSyn-mediated degeneration.

Figure 4—figure supplement 3. CtHsp104 does not inhibit TDP-43 condensation in human cells.

We also assessed how CtHsp104 affects αSyn toxicity in C. elegans DA neurons (Figure 4—figure supplement 2) and TDP-43 aggregation in HEK293T cells (Figure 4—figure supplement 3). Surprisingly, CtHsp104 does not affect C. elegans DA neuron survival (Figure 4—figure supplement 2), despite robust suppression of αSyn-mediated toxicity and inclusion formation in yeast (Figure 2A, F, G; Michalska et al., 2019). CtHsp104 likewise fails to suppress TDP-43 aggregation in HEK293T cells (Figure 4—figure supplement 3) despite suppression of TDP-43 toxicity in yeast (Figure 1B; Michalska et al., 2019). The lack of CtHsp104-mediated neuroprotection in C. elegans and TDP-43 aggregation-inhibition activity in HEK293T cells may be due to the fact that CtHsp104 is promiscuous. By contrast, the substrate-specific Hsp104 homologs were more effective in metazoan model systems.

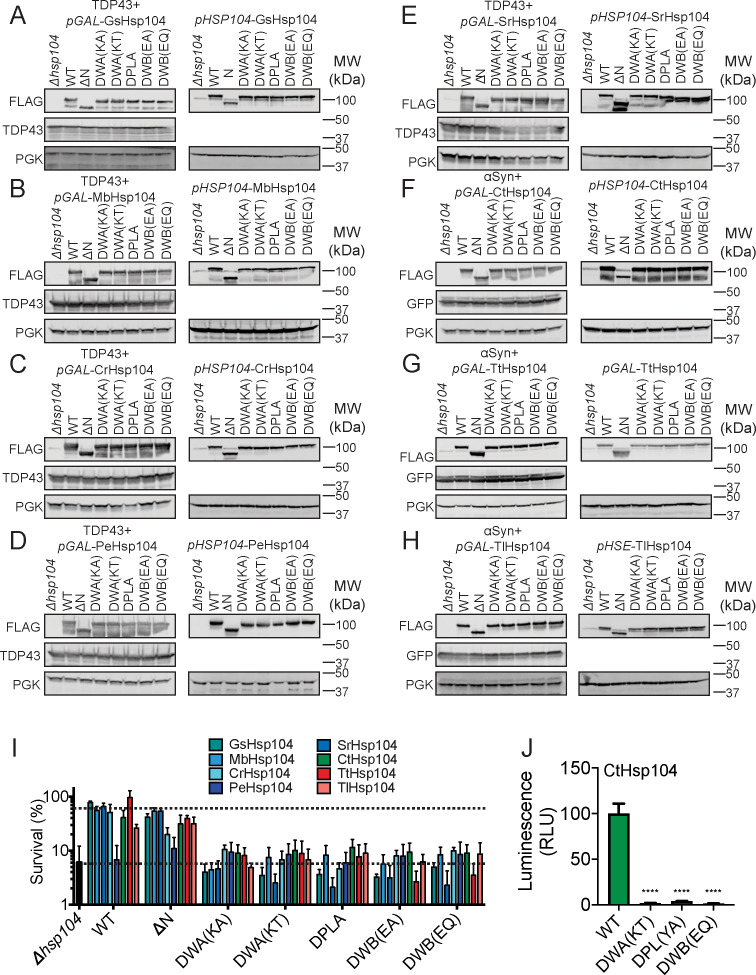

Differential suppression of proteotoxicity by Hsp104 homologs is not due to changes in disaggregase activity

Next, we sought to understand why some Hsp104 homologs suppress TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity while others do not. One possible explanation is that Hsp104 homologs differ in disaggregase activity, as has been the case with potentiated Hsp104 variants (Jackrel et al., 2014; Jackrel and Shorter, 2014; Jackrel et al., 2015; Tariq et al., 2019; Tariq et al., 2018; Torrente et al., 2016). Potentiated disaggregases typically display elevated ATPase and disaggregase activities, including having substantial disaggregase activity even in the absence of Hsp70 and Hsp40 chaperones (Figure 5—figure supplement 1A–C; Jackrel et al., 2014; Jackrel and Shorter, 2014; Jackrel et al., 2015; Tariq et al., 2019; Tariq et al., 2018; Torrente et al., 2016). This elevated activity can sometimes manifest as a temperature-dependent toxicity phenotype (Figure 1—figure supplement 2; Jackrel et al., 2014; Jackrel et al., 2015). However, the Hsp104 homologs we assess here (except for PfHsp104) are non-toxic under conditions where some potentiated Hsp104 variants, such as Hsp104A503V, are toxic (Figure 1—figure supplement 2). This finding hints that these natural homologs are not potentiated in the same way as engineered variants. To explore this issue further, we directly assessed whether the toxicity-suppression behavior of Hsp104 homologs could be explained by differences in disaggregase activity.

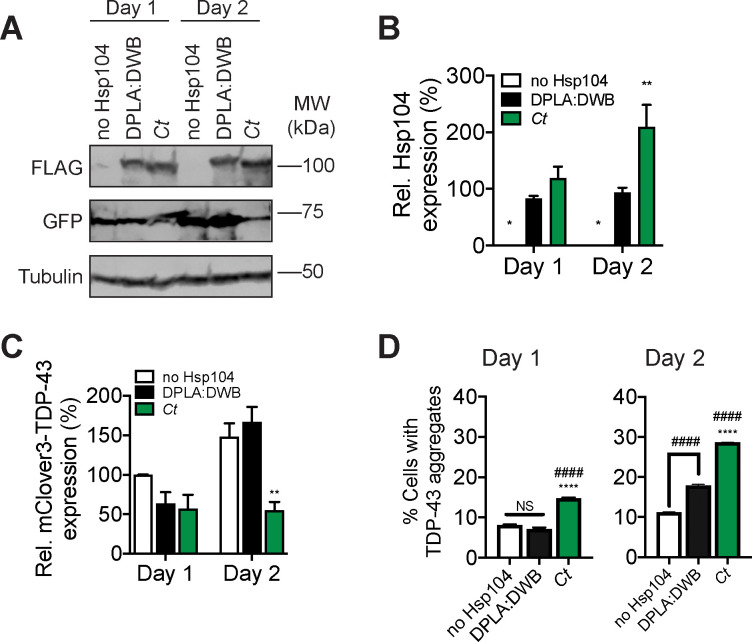

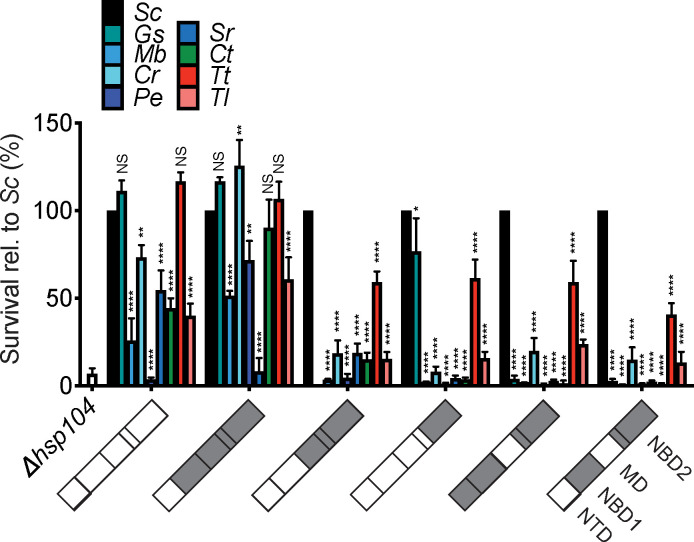

First, we tested how well our Hsp104 homologs conferred thermotolerance (i.e. the ability to survive a 50°C heat shock) to yeast. Hsp104 is an essential factor for induced thermotolerance in yeast (Sanchez and Lindquist, 1990), and Hsp104 homologs in bacteria and plants have similar functions in their respective hosts (Mogk et al., 1999; Queitsch et al., 2000). The ability of Hsp104 to confer thermotolerance depends on its disaggregase activity, which solubilizes proteins trapped in heat-induced protein assemblies (Glover and Lindquist, 1998; Parsell et al., 1994b; Parsell et al., 1991; Tessarz et al., 2008; Wallace et al., 2015). Thus, thermotolerance is a convenient in vivo proxy for disaggregase activity among different Hsp104 homologs. Indeed,~75% of WT yeast survive a 20 min heat shock at 50°C whereas ~1% of Δhsp104 mutants survive the same shock (Figure 5A,B). Expressing FLAG-tagged ScHsp104 from a plasmid effectively complements the thermotolerance defect of Δhsp104 yeast (Figure 5A,B). We generated transgenic yeast strains in which Hsp104 homologs are expressed under the control of the native S. cerevisiae HSP104 promoter (except for TtHsp104, which was expressed from pGAL-see Materials and Methods), and assessed the thermotolerance phenotypes of these strains. We observed a range of phenotypes. Specifically, 15 of 17 Hsp104s tested conferred some degree of thermotolerance above Δhsp104 alone (Figure 5A,B). The two exceptions were ClpB from E. coli and Hsp104 from Populus euphratica (Figure 5A,B). Some homologs, such as those from Thielavia terrestris, Galdieria sulphuraria, and Dictyostelium discoideum strongly complement thermotolerance while others were relatively weak (Figure 5A,B). Thermotolerance phenotypes are not explained by the evolutionary divergence time of a particular species from S. cerevisiae (Figure 5C). Thermotolerance phenotypes for Hsp104 homologs that reduce TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity do not differ noticeably from thermotolerance phenotypes for Hsp104 homologs that rescue neither TDP-43 nor αSyn toxicity (Figure 5D). Interestingly, ClpGGI confers a strong thermotolerance phenotype to Δhsp104 yeast (Figure 2—figure supplement 3G) while ClpB does not (Parsell et al., 1993), although both are from prokaryotes. This difference is likely due to the fact that ClpGGI is a stand-alone disaggregase and does not depend on Hsp70 and Hsp40 for disaggregation (Katikaridis et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2018) while ClpB is incompatible with yeast Hsp70 and Hsp40 (Krzewska et al., 2001; Miot et al., 2011; Parsell et al., 1993). Nevertheless, our results demonstrate that evolutionarily diverse Hsp104 homologs confer thermotolerance to Δhsp104 yeast, but differences in thermotolerance activity do not explain differences in suppression of TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity.

Figure 5. Hsp104 homologs function in induced thermotolerance but differences in thermotolerance activity do not explain suppression of TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity.

(A) WT or Δhsp104 yeast carrying a plasmid encoding the indicated Hsp104 homolog under the control of the native HSP104 promoter (except for TtHsp104, which was expressed from pGAL-see Materials and Methods) were pre-treated at 37°C for 30 min, treated at 50°C for 0–60 min, and plated. Surviving colonies were quantified after 2d recovery. Values represent means ± SEM (n = 3 independent transformations). (B) Hsp104 homologs ranked by thermotolerance performance after a 20 min heat shock at 50°C. (C) Survival after 20 min heat shock does not correlate with the evolutionary separation between a given species and S. cerevisiae. (D) Thermotolerance activity of Hsp104 homologs that suppress TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity ('Rescuers') does not noticeably differ from Hsp104 homologs that do not suppress TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity ('Non-rescuers'). (E) Expression of Hsp104 and Hsp26 before (uninduced) or after pretreatment at 37°C for 30 min (induced) was assessed by Western blot. Molecular weight markers are indicated (right). PGK serves as a loading control. An ScHsp104-specific antibody was used to detect untagged ScHsp104 or ScHsp104-FLAG. A FLAG antibody was used to detect Hsp104-FLAG. (F) Expression of Hsp26 relative to PGK was quantified for each strain. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare expression of Hsp26 in the WT, induced strain to all other conditions. **p<0.01. (G) Expression of Hsp104-FLAG relative to PGK was quantified for each strain. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare expression of ScHsp104-FLAG (Sc) to all other conditions. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. (H) Hsp104-FLAG expression is a weak predictor of yeast survival after 20 min heat shock. Values represent means ± SEM (n = 3). A simple linear regression yielded a coefficient of determination, R2 = 0.24.

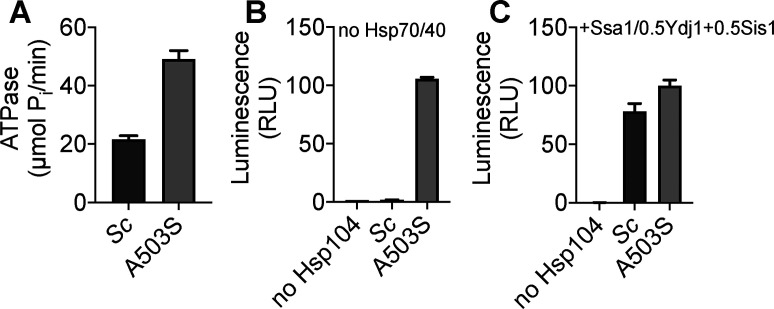

Figure 5—figure supplement 1. Biochemical comparison of wild-type ScHsp104 to the potentiated variant ScHsp104A503S.

Next, we assessed how differences in protein expression between strains may contribute to phenotypic differences. All strains mount an effective heat-shock response, as indicated by Hsp26 levels assessed by Western blot (Figure 5E,F). We also measured Hsp104-FLAG expression levels in each strain by Western blot (Figure 5E,G). Although expression of Hsp104 homologs is somewhat variable (Figure 5E,G), expression level is a poor predictor of thermotolerance (Figure 5H, R2 = 0.24).

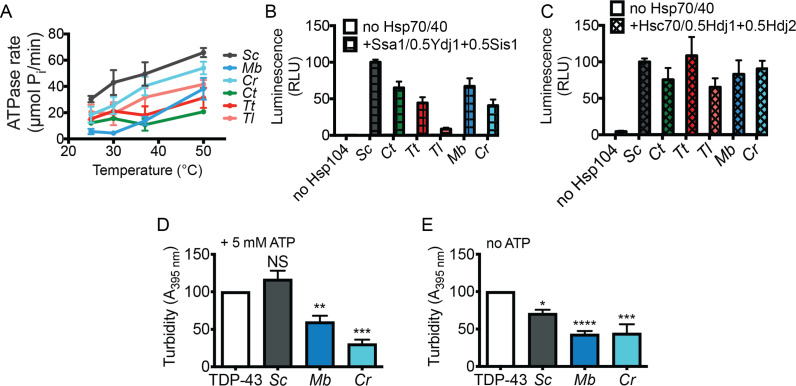

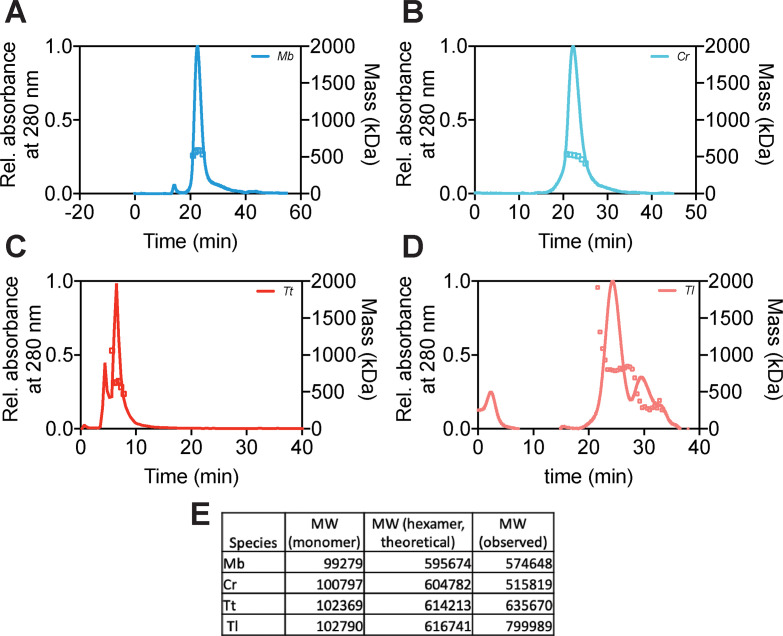

We next expressed and purified several Hsp104 homologs (MbHsp104, CrHsp104, TtHsp104, TlHsp104, ScHsp104, and CtHsp104) to define their biochemical properties. Hsp104 homologs likely form hexamers (Figure 6—figure supplement 1; Michalska et al., 2019), are active ATPases (which requires Hsp104 hexamerization [Mackay et al., 2008; Parsell et al., 1994a; Parsell et al., 1994b; Schirmer et al., 1998; Schirmer et al., 2001]), and display increased ATPase activity with increasing temperature (Figure 6A). These findings are consistent with the fact that Hsp104 is a disaggregase induced by thermal stress.

Figure 6. Hsp104 homologs are disaggregases in vitro but differences in disaggregase activity do not explain suppression of TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity.

(A) ATPase activity of the indicated Hsp104 homologs at different temperatures. Values represent means ± SEM (n = 3). (B) Luciferase aggregates (50 nM) were incubated with the indicated Hsp104 (0.167 µM hexamer) with or without 0.167 µM Ssa1, 0.073 µM Ydj1, and 0.073 µM Sis1 for 90 min at 25°C. Values represent means ± SEM (n = 3). (C) Luciferase aggregates were treated as in (B) but Ssa1, Ydj1, and Sis1 were replaced with Hsc70, Hdj1, and Hdj2. Values represent means ± SEM (n = 3). (D) TDP-43 (3 µM) was incubated in the presence of the indicated Hsp104 (6 µM) and 5 mM ATP, and turbidity was measured at 3 hr relative to TDP-43 aggregation reactions containing no Hsp104. Values represent means ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare TDP-43 alone to all other conditions. NS, not significant; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. (E) As in (D), except ATP was omitted and turbidity was measured at 2 hr. Values represent means ± SEM (n = 3). One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare TDP-43 alone to all other conditions. *p<0.05; ****p<0.0001; ***p<0.001.

Figure 6—figure supplement 1. Hsp104 homologs form hexamers.

Figure 6—figure supplement 2. Hsp104 homologs remodel SEVI fibrils.

Figure 6—figure supplement 3. Hsp104 homologs do not affect MBP-TEV-TDP43 cleavage by TEV protease.

We also investigated the disaggregase activity of Hsp104 homologs (which also requires hexamerization [Mackay et al., 2008; Parsell et al., 1994a; Parsell et al., 1994b; Schirmer et al., 1998; Schirmer et al., 2001]) by assessing their ability to disaggregate chemically-denatured luciferase aggregates in vitro (DeSantis et al., 2012; Glover and Lindquist, 1998). These aggregated structures are ~500–2,000 kDa or greater in size and cannot be disaggregated by Hsp70 and Hsp40 alone (Cupo and Shorter, 2020; Glover and Lindquist, 1998; Shorter, 2011). Typically, when combined with Hsp70 and Hsp40, ScHsp104 recovers ~10–30% of the native luciferase activity from these aggregated structures (Cupo and Shorter, 2020; Glover and Lindquist, 1998; Shorter, 2011). First, we compared the disaggregase activity of ScHsp104WT to the potentiated variant ScHsp104A503S, which exhibits elevated ATPase activity (Figure 5—figure supplement 1A; Jackrel et al., 2014). We found that ScHsp104A503S has enhanced luciferase disaggregation activity as expected in the absence of Hsp70 and Hsp40 (where ScHsp104 is inactive (Figure 5—figure supplement 1B)) and in the presence of Hsp70 and Hsp40 (Figure 5—figure supplement 1C; Jackrel et al., 2014). Next, we assessed the Hsp104 homologs, which could all disassemble and reactivate aggregated luciferase (Figure 6B,C). Luciferase disaggregation required the presence of Hsp70 and Hsp40 chaperones, which could be from yeast (Ssa1, Sis1, and Ydj1 Figure 6B) or human (Hsc70, Hdj1, and Hdj2 Figure 6C). The robust ATPase and disaggregase activity of the Hsp104 homologs provides strong evidence that they assemble in functional hexamers like ScHsp104. We did not observe differences in luciferase disaggregation activity of Hsp104 homologs that would readily explain selective suppression of TDP-43 toxicity versus αSyn toxicity (Figure 6B,C).

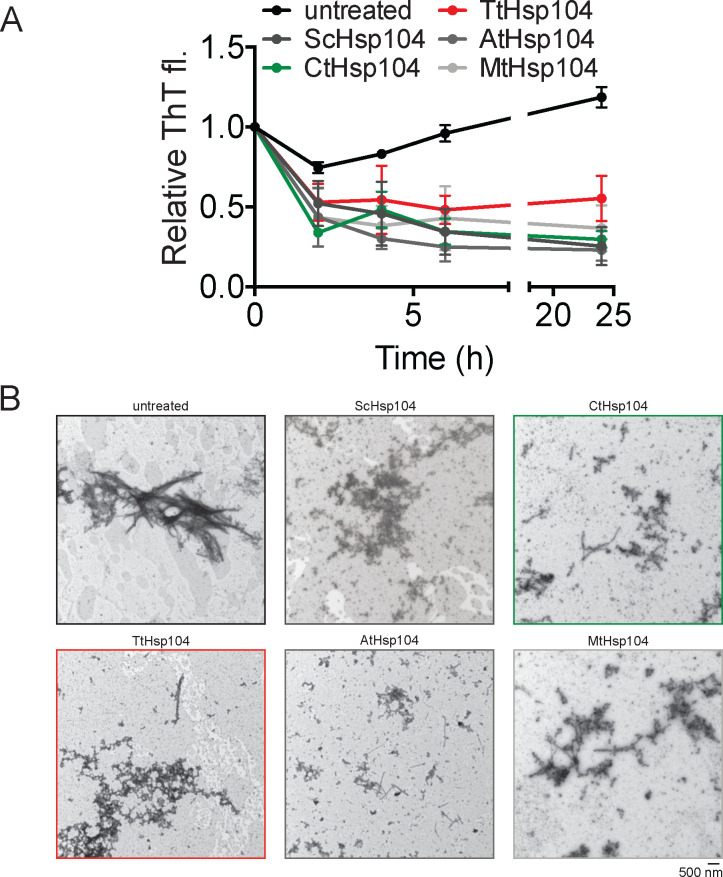

Next, we tested the activity of several Hsp104 homologs (ScHsp104, CtHsp104, TtHsp104, AtHsp104, and MtHsp104) against an ordered amyloid substrate, semen-derived enhancer of viral infection (SEVI) (Münch et al., 2007). As previously reported for ScHsp104 and CtHsp104 (Castellano et al., 2015; Michalska et al., 2019), all Hsp104 homologs tested rapidly remodeled SEVI fibrils (Figure 6—figure supplement 2A). Electron microscopy revealed that Hsp104 homologs remodeled SEVI fibrils into small, amorphous structures (Figure 6—figure supplement 2B). Thus, eukaryotic Hsp104 homologs are generally able to remodel amyloid fibrils, unlike prokaryotic ClpB or hyperactive variants that have limited ability to remodel SEVI amyloid (Castellano et al., 2015). However, there was not an obvious difference in amyloid-remodeling activity between homologs that suppress αSyn toxicity (CtHsp104 and TtHsp104) and those that do not (ScHsp104, AtHsp104, and MtHsp104). Taken together, these findings suggest that differences in proteotoxicity suppression by Hsp104 homologs is not simply due to differences in their general disaggregase activity.

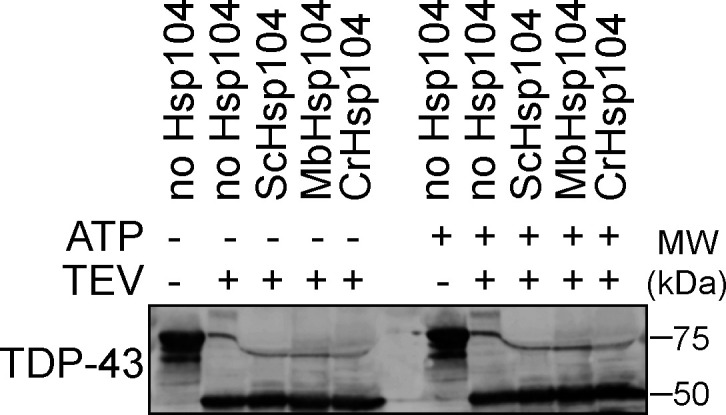

Hsp104 homologs can inhibit protein aggregation in an ATP-independent manner

Since differences in general disaggregase activity do not explain differences in proteotoxicity suppression among Hsp104 homologs, we wondered whether Hsp104 homologs may act instead to inhibit protein aggregation. To test this possibility, we reconstituted TDP-43 aggregation in vitro to test how Hsp104 homologs affect TDP-43 aggregation (Mann et al., 2019). We performed reactions in the presence (Figure 6D) or absence (Figure 6E) of ATP. Hsp104 from Monosiga brevicollis and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, which selectively suppress TDP-43 toxicity and foci formation in yeast, inhibit TDP-43 aggregation in vitro, whereas Hsp104 from S. cerevisiae has limited efficacy (Figure 6D,E). Hsp104-mediated inhibition of TDP-43 aggregation occurred in the presence or absence of ATP (Figure 6D,E). Hsp104 homologs did not inhibit TDP-43 aggregation merely by inhibiting cleavage of the MBP tag by TEV protease (Figure 6—figure supplement 3). Thus, unexpectedly, specific Hsp104 homologs likely suppress TDP-43 toxicity by inhibiting its aggregation in an ATP-independent manner.

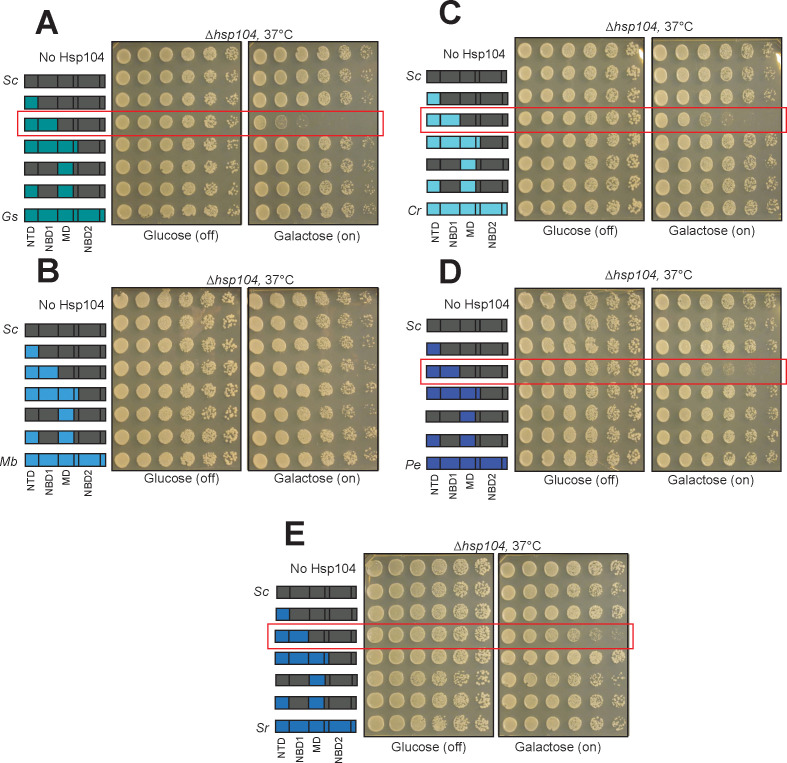

Hsp104 homologs can suppress toxicity of TDP-43 and αSyn in an ATPase-independent manner

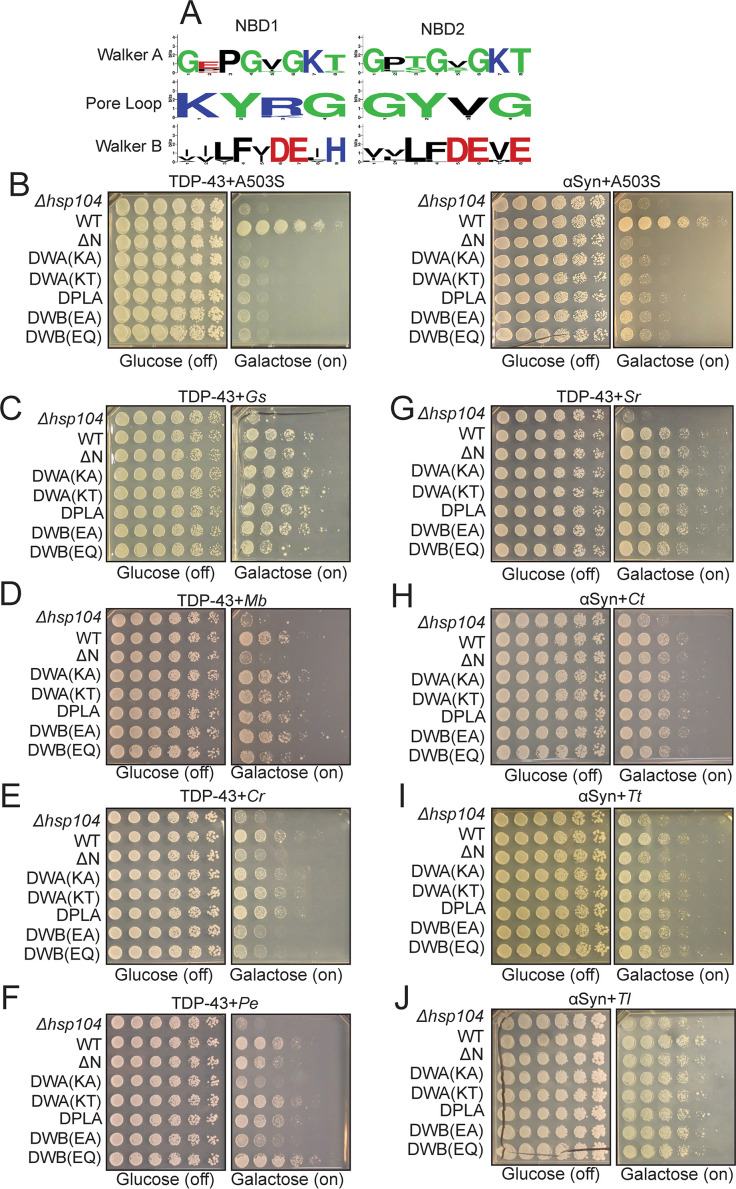

Hsp104 homologs inhibited TDP-43 aggregation in vitro in the absence of nucleotide, indicating a passive mechanism of action. We next tested whether Hsp104 homologs also employed a passive mechanism to suppress TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity in yeast. Thus, we generated a series of mutants for each Hsp104 homolog intended to disrupt their disaggregase activity. Hsp104 disaggregase activity is driven by: (1) ATP binding and hydrolysis, which are mediated by Walker A and Walker B motifs, respectively, and which drive conformational changes within the hexamer to support substrate translocation (DeSantis et al., 2012; Parsell et al., 1991; Ye et al., 2019), and (2) substrate translocation through the central pore of the hexamer, which is mediated by tyrosine-bearing pore loops (DeSantis et al., 2012; Gates et al., 2017; Lum et al., 2008; Lum et al., 2004). These motifs are highly conserved among all Hsp104 homologs (Figure 7A and Figure 1—figure supplement 1). We mutated: (1) conserved lysine residues in the Walker A motifs to either alanine or threonine (Hsp104DWA(KA) and Hsp104DWA(KT)) in NBD1 and NBD2 to impair ATP binding, (2) conserved glutamate residues in the Walker B motifs to either alanine or glutamine (e.g. Hsp104DWB(EA) or Hsp104DWB(EQ)) in NBD1 and NBD2 to impair ATP hydrolysis, and (3) conserved tyrosines in the pore loops to alanine (e.g. Hsp104DPLA) in NBD1 and NBD2 to impair substrate threading through the central hexamer pore (DeSantis et al., 2012). We also generated mutants lacking the NTD, which also plays a role in substrate binding and processing (Sweeny et al., 2015; Sweeny et al., 2020).

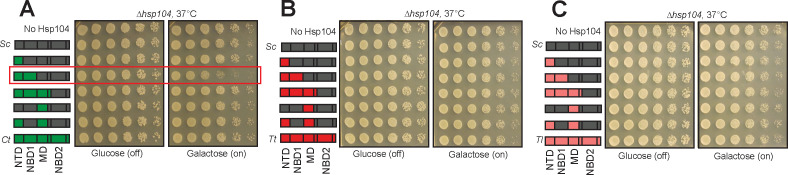

Figure 7. Hsp104 homologs can suppress toxicity of TDP-43 and αSyn in a manner that does not require conserved AAA+ motifs.

(A) WebLogo sequence logos demonstrating high conservation of Walker A, tyrosine-bearing pore loops, and Walker B motifs in both NBD1 and NBD2 across all Hsp104 homologs. (B–J) Spotting assays to define how mutations affect the ability of Hsp104 variants to suppress TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity. Within each panel, distinct yeast strains are spotted in rows and are labeled by the type of Hsp104 being expressed in each instance (Δhsp104, no Hsp104 being expressed; WT, Hsp104 variant with no additional mutations; ΔN, Hsp104 variant lacking an NTD; DWA(KA) and DWA(KT), Hsp104 variant with the indicated substitutions in the Walker A motifs; DPLA, Hsp104 variant with pore-loop tyrosines mutated to alanine; DWB(EA) and DWB(EQ), Hsp104 variant with the indicated substitutions in the Walker B motifs). (B) Spotting assay demonstrating that Hsp104A503S (A503S)-mediated suppression of TDP-43 (left) and αSyn (right) toxicity is inhibited by NTD deletion (ΔN) and mutations in Walker A (DWA(KA) and DWA(KT)), pore loop (DPLA), and Walker B (DWB(EA) and DWB(EQ)) motifs. (C) Spotting assay demonstrating that GsHsp104 (Gs)-mediated suppression of TDP-43 toxicity is resistant to NTD deletion (ΔN) as well as mutations in Walker A (DWA(KA) and DWA(KT)), pore loop (DPLA), and Walker B (DWB(EA) and DWB(EQ)) motifs. (D) Spotting assay demonstrating that MbHsp104 (Mb)-mediated suppression of TDP-43 toxicity is ablated by NTD deletion (ΔN) but is resistant to mutations in Walker A (DWA(KA) and DWA(KT)), pore loop (DPLA), and Walker B (DWB(EA) and DWB(EQ)) motifs. (E) Spotting assay demonstrating that CrHsp104 (Cr)-mediated suppression of TDP-43 toxicity is ablated by NTD deletion (ΔN) and mutations in Walker B (DWB(EA) and DWB(EQ)) motifs but is resistant to mutations in Walker A (DWA(KA) and DWA(KT)) and pore loop (DPLA) motifs. (F) Spotting assay demonstrating that PeHsp104 (Pe)-mediated suppression of TDP-43 toxicity is resistant to NTD deletion (ΔN) and mutations in pore loop (DPLA) motifs, but is partially sensitive to mutations in Walker A (i.e. suppression is ablated by DWA(KA) but not DWA(KT)) and Walker B (i.e. suppression is ablated by DWB(EA) but not DWB(EQ)) motifs. (G) Spotting assay demonstrating that SrHsp104 (Sr)-mediated suppression of TDP-43 is resistant to NTD deletion (ΔN) as well as mutations in Walker A (DWA(KA) and DWA(KT)), pore loop (DPLA), and Walker B (DWB(EA) and DWB(EQ)) motifs. (H) Spotting assay demonstrating that CtHsp104 (Ct)-mediated suppression of αSyn toxicity is resistant to NTD deletion (ΔN) as well as mutations in Walker A (DWA(KA) and DWA(KT)), pore loop (DPLA), and Walker B (DWB(EA) and DWB(EQ)) motifs. (I) Spotting assay demonstrating that TtHsp104 (Tt)-mediated suppression of αSyn toxicity is ablated by NTD deletion (ΔN) but is resistant to mutations in Walker A (DWA(KA) and DWA(KT)), pore loop (DPLA), and Walker B (DWB(EA) and DWB(EQ)) motifs. (J) Spotting assay demonstrating that TlHsp104 (Tl)-mediated suppression of αSyn toxicity is resistant to NTD deletion (ΔN) as well as mutations in Walker A (DWA(KA) and DWA(KT)), pore loop (DPLA), and Walker B (DWB(EA) and DWB(EQ)) motifs.

Figure 7—figure supplement 1. Hsp104 mutants are consistently expressed and are defective in thermotolerance.

We monitored expression of Hsp104 mutant proteins by Western blot, and found all mutants were expressed similarly to WT Hsp104, from either the galactose or native HSP104 promoter (Figure 7—figure supplement 1A–H). Yeast expressing Walker A, Walker B, or pore-loop mutant proteins are all severely impaired in thermotolerance compared to WT controls, while ΔN mutants are only mildly impaired in thermotolerance compared to WT proteins (Figure 7—figure supplement 1I). These findings are similar to thermotolerance phenotypes of ScHsp104 mutants that have been previously reported (DeSantis et al., 2012; Parsell et al., 1991; Sweeny et al., 2015). The only exception is PeHsp104, where the WT protein confers no thermotolerance benefit over Δhsp104 cells, which precludes any conclusions being drawn about the impact of mutations on this protein (Figure 5B and Figure 7—figure supplement 1I). To confirm that the Walker A, Walker B, or pore-loop mutations inactivate disaggregase activity in Hsp104 homologs at the pure protein level, we purified CtHsp104 variants with these mutations and assessed their effect on luciferase disaggregase activity. As expected, mutation of Walker A, Walker B, or pore-loop motifs eliminate CtHsp104 disaggregase activity (Figure 7—figure supplement 1J). Thus, we confirm that these mutations have a conserved effect on Hsp104 disaggregase activity.

Next, we examined how these mutations affect the ability of different Hsp104 homologs to reduce TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity in yeast. TDP-43 or αSyn expression levels were largely unaffected by Hsp104 mutants, as assessed by Western blot (Figure 7—figure supplement 1A–H). All of the aforementioned mutations strongly impair the ability of a potentiated Hsp104 variant, ScHsp104A503S, to suppress TDP-43 and αSyn toxicity (Sweeny et al., 2015; Torrente et al., 2016; Figure 7B). Thus, ScHsp104A503S suppresses TDP-43 and αSyn toxicity by a disaggregase-mediated mechanism that requires the NTD, ATP binding and hydrolysis, and substrate-engagement by conserved pore-loop tyrosines (Sweeny et al., 2015; Torrente et al., 2016). Remarkably, however, Hsp104 homolog-mediated suppression of TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity was largely unaffected by our specific alterations to Walker A, Walker B, or pore-loop residues (Figure 7C–J). For example, mutation of conserved pore-loop tyrosines to alanine had no effect on suppression of TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity (Figure 7C–J). Thus, canonical substrate translocation is likely not required for these Hsp104 homologs to mitigate TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity.

Likewise, in most cases, mutation of Walker A or Walker B motifs did not affect suppression of TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity (Figure 7C–J). There were, however, some exceptions. CrHsp104 was inhibited by mutations in the Walker B motifs (Figure 7E). Thus, CrHsp104 requires conserved Walker B motifs (but not conserved Walker A motifs) for optimal suppression of toxicity (Figure 7E). Notably, this requirement was not coupled to substrate translocation by conserved pore-loop tyrosines (Figure 7E). Additionally, PeHsp104 was modestly inhibited by K to A but not K to T substitutions in the Walker A motif and E to A but not E to Q substitutions in the Walker B motifs (Figure 7F). Thus, PeHsp104 likely requires some level of ATPase activity for optimal suppression of toxicity. It may be that the K to T substitution in the Walker A motif and the E to Q substitution in the Walker B motif do not have such large effects in this specific homolog. Regardless, any requirement for ATPase activity was not coupled to substrate translocation by conserved pore-loop tyrosines in PeHsp104 (Figure 7F). Importantly, the remaining Hsp104 homologs tested here (GsHp104, MbHsp104, SrHsp104, CtHsp104, TtHsp104, and TlHsp104) suppressed TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity by a mechanism that does not require ATPase activity or conserved pore-loop tyrosines that engage substrate in the Hsp104 channel (Figure 7C,D,H–J). Mechanistically, these findings suggest that toxicity suppression by the majority of Hsp104 homologs tested here (GsHp104, MbHsp104, SrHsp104, CtHsp104, TtHsp104, and TlHsp104) is primarily due to ATPase-independent activity against specific substrates, such as TDP-43 or αSyn, and not due to ATPase-dependent disaggregase activity or chaperone activity.

Suppression of TDP-43 toxicity by MbHsp104 and CrHsp104, and suppression of αSyn toxicity by TtHsp104 requires the NTD

Next, we sought to identify the requisite architecture of Hsp104 homologs that enables TDP-43 or αSyn proteotoxicity suppression. The engineered ScHsp104 variant, Hsp104A503S, requires the NTD to mitigate TDP-43 and αSyn toxicity (Figure 7B; Sweeny et al., 2015). TDP-43 or αSyn proteotoxicity suppression by several Hsp104 homologs (GsHsp104, PeHsp104, SrHsp104, CtHsp104, and TlHsp104) is not greatly affected by NTD deletion (Figure 7C,F,G,H,J). Interestingly, MbHsp104ΔN and CrHsp104ΔN are unable to suppress TDP-43 toxicity (Figure 7D,E), and TtHsp104ΔN is unable to suppress αSyn toxicity (Figure 7I). Thus, proteotoxicity suppression by these specific Hsp104 homologs requires their NTDs.

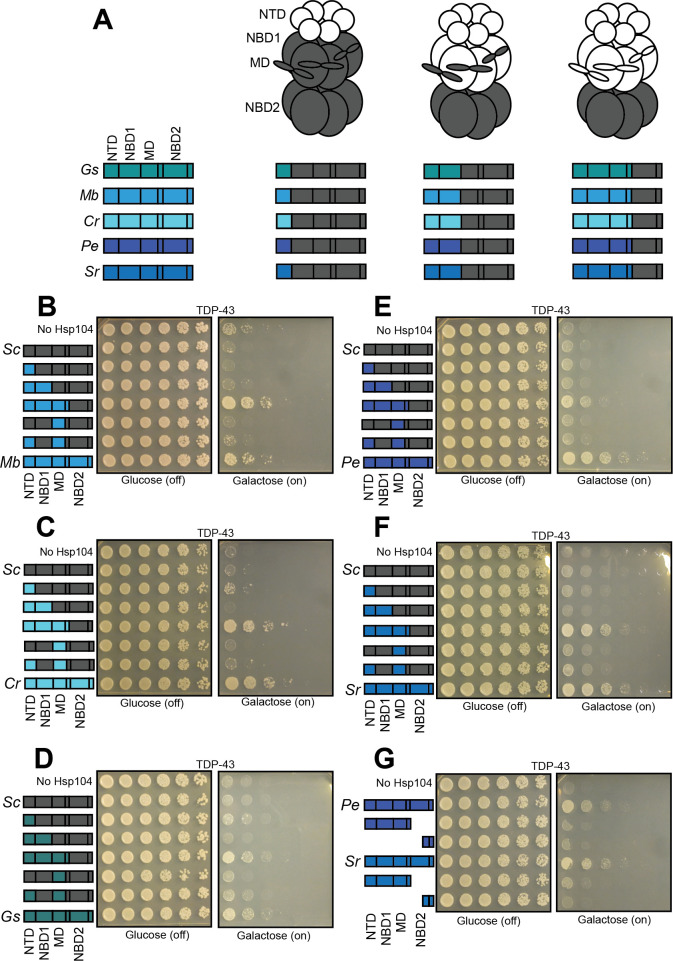

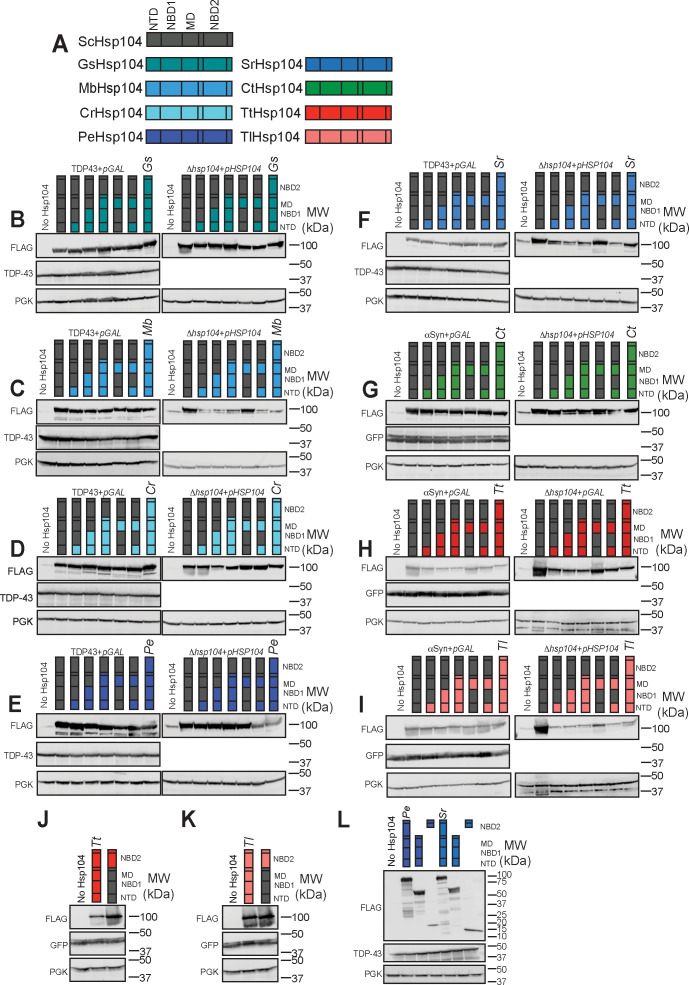

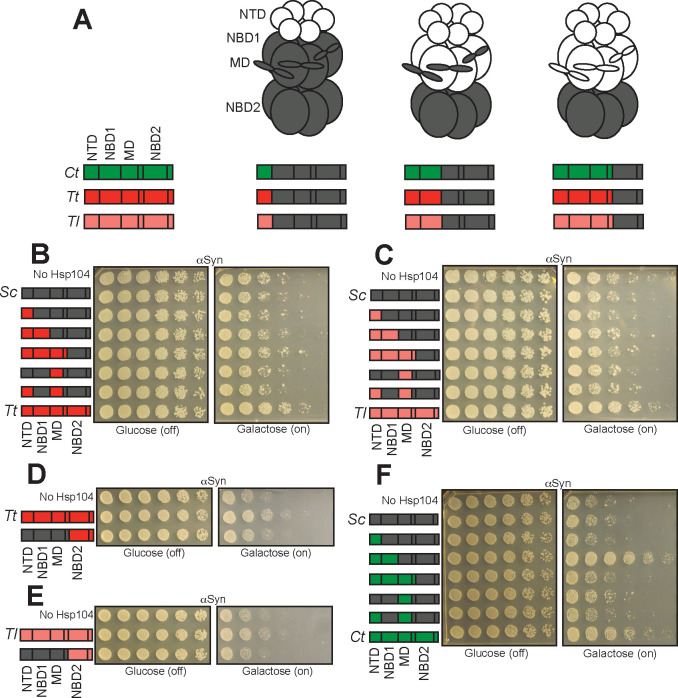

We wondered whether the NTDs might drive the toxicity-suppression phenotypes for MbHsp104, CrHsp104, and TtHsp104. To test this possibility as well as additional questions concerning domain requirements, we made a series of Hsp104 chimeras (Figures 8 and 9) in which we systematically replaced domains of ScHsp104 with the homologous domains from other Hsp104 homologs (see Figures 8A and 9A for illustration of domain boundaries and chimeras). Prior studies indicate that chimeric proteins formed between Hsp104 homologs can form hexamers that possess robust disaggregase activity in vitro and in vivo (DeSantis and Shorter, 2012a; Miot et al., 2011).

Figure 8. Interactions between the NTD, NBD1, and MD support TDP-43 toxicity suppression by Hsp104 homologs.

(A) Color codes and domain boundaries and labels of Hsp104 homologs. (B) Spotting assay of Δhsp104 yeast coexpressing TDP-43 and the indicated chimeric Hsp104s between ScHsp104 and MbHsp104 illustrates that chimeras possessing the NTD, NBD1, and MD from MbHsp104 copy the TDP-43 toxicity-suppression phenotype of MbHsp104. (C) Spotting assay of Δhsp104 yeast coexpressing TDP-43 and the indicated chimeric Hsp104 between ScHsp104 and CrHsp104 illustrates that chimeras possessing the NTD, NBD1, and MD from CrHsp104 copy the TDP-43 toxicity-suppression phenotype of CrHsp104. (D) Spotting assay of Δhsp104 yeast coexpressing TDP-43 and the indicated chimeric Hsp104 between ScHsp104 and GsHsp104 illustrates that chimeras possessing the NTD, NBD1, and MD from GsHsp104 copy the TDP-43 toxicity-suppression phenotype of GsHsp104. (E) Spotting assay of Δhsp104 yeast coexpressing TDP-43 and the indicated chimeric Hsp104 between ScHsp104 and PeHsp104 illustrates that chimeras possessing the NTD, NBD1, and MD from PeHsp104 copy the TDP-43 toxicity-suppression phenotype of PeHsp104. (F) Spotting assay of Δhsp104 yeast coexpressing TDP-43 and the indicated chimeric Hsp104 between ScHsp104 and SrHsp104 illustrates that chimeras possessing the NTD, NBD1, and MD from SrHsp104 copy the TDP-43 toxicity-suppression phenotype of SrHsp104. (G) Spotting assay of Δhsp104 strains coexpressing TDP-43 and either full-length PeHsp104 or SrHsp104, or monomeric fragments derived from these homologs demonstrates that Hsp104-mediated toxicity suppression is an emergent property of hexameric Hsp104.

Figure 8—figure supplement 1. Chimeric Hsp104s and proteotoxic substrates are consistently expressed in yeast.

Figure 8—figure supplement 2. Characterization of Hsp104 chimera specificity for TDP-43.

Figure 8—figure supplement 3. Characterization of the intrinsic toxicity of Hsp104 chimeras.

Figure 9. The NBD2:CTD unit of TtHsp104 and TlHsp104 contribute to suppression of αSyn toxicity.

(A) Color codes and domain boundaries and labels of Hsp104 homologs. (B) Spotting assay of Δhsp104 strains coexpressing αSyn and the indicated chimeric Hsp104 between ScHsp104 and TtHsp104 illustrates that no chimeras between ScHsp104 and TtHsp104 replicate the αSyn toxicity-suppressing phenotype of TtHsp104. (C) Spotting assay of Δhsp104 strains coexpressing αSyn and the indicated chimeric Hsp104 between ScHsp104 and TlHsp104 illustrates that no chimeras between ScHsp104 and TlHsp104 replicate the αSyn toxicity-suppressing phenotype of TlHsp104. (D, E) Spotting assays of Δhsp104 strains coexpressing the indicated chimeric Hsp104 and αSyn illustrates that the NBD2:CTD unit from TtHsp104 (D) or TlHsp104 (E) is not sufficient to copy the αSyn toxicity-suppression phenotype of TtHsp104 or TlHsp104. (F) Spotting assay of Δhsp104 strains coexpressing the indicated chimeric Hsp104 and αSyn illustrates that chimeras possessing the NTD and NBD1 from CtHsp104 copies the αSyn toxicity-suppressing phenotype of CtHsp104WT.

Figure 9—figure supplement 1. Thermotolerance activity of Hsp104 chimeras.

Figure 9—figure supplement 2. Toxicity of select chimeras between CtHsp104 and ScHsp104.

We found that replacing the NTD of ScHsp104 with the NTD of either MbHsp104 or CrHsp104 did not enable suppression of TDP-43 toxicity by the resulting chimeras (Figure 8B,C). Similarly, replacing the ScHsp104 NTD with the NTD from TtHsp104 did not enable suppression of αSyn toxicity by the resulting chimera (Figure 9B). Thus, proteotoxicity suppression by MbHsp104, CrHsp104, and TtHsp104 is not simply transmitted through or encoded by the NTD. Rather, the NTD must work together with neighboring domains of the same Hsp104 homolog to enable toxicity suppression.

Suppression of TDP-43 toxicity is enabled by NBD1 and MD residues in Hsp104 homologs

Based on our observation that suppression of TDP-43 and αSyn toxicity by MbHsp104, CrHsp104, and TtHsp104 is not conferred solely by the NTD (Figures 8B,C and 9B), and the observation that ΔN mutants of other homologs (GsHsp104, PeHsp104, SrHsp104, CtHsp104, and TlHsp104) retained their ability to reduce either TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity (Figure 7C,F,G,H,J), we reasoned that residues in other domains must also contribute to substrate selectivity. Within the ScHsp104 hexamer, the NTD interacts with NBD1 and the MD (Sweeny et al., 2020). Thus, we assessed additional chimeras by progressively replacing the NTD, NBD1 or MD of ScHsp104 for the homologous domain from another Hsp104 homolog (see Figures 8A and 9A for illustrations). Generally, the chimeras expressed well in yeast (Figure 8—figure supplement 1). We observed that chimeras consisting of the NTD, NBD1, and MD from a TDP-43-selective homolog appended to the NBD2 and CTD from ScHsp104 phenocopied the TDP-43 suppression phenotype associated with the homolog itself (Figure 8B–F). These same chimeras do not reduce αSyn toxicity (Figure 8—figure supplement 2A–E). Thus, these chimeras encompass the sequence determinants that are crucial for passive inhibition of TDP-43 aggregation. Chimeras where cognate NTD:NBD1:MD networks were disrupted do not reduce TDP-43 toxicity (Figure 8B–F). We conclude that genetic variation in NBD1 and the MD of Hsp104 homologs also contributes to mitigation of TDP-43 proteotoxicity.

Homolog-mediated suppression of TDP-43 toxicity requires the NBD2:CTD unit

Next, we tested whether NBD2 was required for suppression of TDP-43 toxicity by Hsp104 homologs, or whether expressing Hsp104 fragments encompassing the NTD, NBD1, and MD (which contain sequence determinants that reduce TDP-43 toxicity) would recapitulate the suppression of toxicity seen with the full-length homolog. We therefore co-expressed PeHsp1041-541and SrHsp1041-551 with TDP-43 in yeast. Neither of these fragments reduce TDP-43 toxicity (Figure 8G; see Figure 8—figure supplement 1L for accompanying Western blot). Two additional fragments, PeHsp104767-914 and SrHsp104781-892, which correspond to the small domain of NBD2 and the CTD also did not reduce TDP-43 toxicity (Figure 8G). Since these Hsp104 fragments are likely monomeric (Hattendorf and Lindquist, 2002; Mogk et al., 2003), we conclude that proteotoxicity suppression is an emergent property of hexameric Hsp104 homologs or chimeras.

The NBD2:CTD unit of TtHsp104 and TlHsp104 contribute to suppression of αSyn toxicity

For the αSyn-specific Hsp104 homologs, TtHsp104 and TlHsp104, chimeras consisting of NTD:NBD1:MD from TtHsp104 or TlHsp104 fused to NBD2:CTD from ScHsp104 were unable to reduce αSyn toxicity (Figure 9B,C). To test whether suppression of αSyn toxicity is encoded by residues within NBD2:CTD, we tested chimeras in which NTD:NBD1:MD were from ScHsp104 and NBD2:CTD was from either TtHsp104 or TlHsp104. However, these chimeras were also incapable of suppressing αSyn toxicity (Figure 9D,E; see Figure 8—figure supplement 1J,K for accompanying Western blots). Thus, these results suggest that additional residues or contacts in the NBD2:CTD unit are necessary but not sufficient for TtHsp104 and TlHsp104 to suppress αSyn toxicity.

Hsp104 chimeras display reduced thermotolerance

We next characterized the thermotolerance activity of all chimeras (Figure 9—figure supplement 1) to understand how perturbing cognate interdomain interactions affects the disaggregase activity of each chimera. All Hsp104 homologs except PeHsp104 have substantial thermotolerance activity (Figure 5A–B and Figure 9—figure supplement 1). However, only GsHsp104 and TtHsp104 have thermotolerance activities that are statistically indistinguishable from that of ScHsp104 (Figure 9—figure supplement 1). Chimeras generated by swapping the NTD alone generally retain thermotolerance activity at a level comparable to the homologs from which the NTD is derived. Interestingly, CrNTDScNBD1:MD:NBD2:CTD and CtNTDScNBD1:MD:NBD2:CTD displayed enhanced thermotolerance relative to CrHsp104 and CtHsp104 (Figure 9—figure supplement 1). Thus, whereas CrHsp104 and CtHsp104 are deficient in thermotolerance activity relative to ScHsp104, CrNTDScNBD1:MD:NBD2:CTD performs significantly better than ScHsp104 and CtNTDScNBD1:MD:NBD2:CTD is indistinguishable from ScHsp104 (Figure 9—figure supplement 1). These results suggest that in some cases NTD swaps do not perturb Hsp104 activity. However, in other cases the NTD swap reduced Hsp104 activity as with SrNTDScNBD1:MD:NBD2:CTD, which displayed minimal thermotolerance comparable to Δhsp104 cells (Figure 9—figure supplement 1).

Swaps of subsequent domains, either alone or in combination, impaired thermotolerance function (Figure 9—figure supplement 1). Some of the weak thermotolerance phenotypes may be attributable to low expression levels of certain chimeras from pHSP104. For instance, several chimeras between MbHsp104 and ScHsp104 are poorly expressed from pHSP104 (Figure 8—figure supplement 1C). Nonetheless, expression levels of chimeras alone are insufficient to explain their thermotolerance phenotypes: even specific chimeras that reduce TDP-43 toxicity and express well from pHSP104 (e.g. CrNTD:NBD1:MDScNBD2:CTD) fail to confer thermotolerance (Figure 9—figure supplement 1). This observation provides further evidence that the mechanism that enables Hsp104 homologs to suppress TDP-43 toxicity is distinct from Hsp104 disaggregase activity.

Non-cognate NTD:NBD1 units can yield toxic chimeras at 37°C

We next assessed the fitness effects intrinsic to the chimeras. We expressed all chimeras in Δhsp104 yeast at 37°C in the absence of any toxic substrate protein to observe any intrinsic toxicity associated with the chimeras themselves. We observed that NTD replacement alone does not cause toxicity (Figure 8—figure supplement 3 and Figure 9—figure supplement 2, third row in all panels). By contrast, replacing both the NTD and NBD1 resulted in toxicity in several cases (e.g. for GsHsp104, CrHsp104, PeHsp104, SrHsp104, and CtHsp104; Figure 8—figure supplement 3A,C,D,E and Figure 9—figure supplement 2A, boxed), although TtHsp104 and TlHsp104 (αSyn-specific variants) were exceptions (Figure 9—figure supplement 2B,C). Interestingly, no toxicity was observed in chimeras where the NTD, NBD1, and MD were replaced together (Figure 8—figure supplement 3 and Figure 9—figure supplement 2, fifth row), nor in chimeras where the MD was replaced alone (Figure 8—figure supplement 3 and Figure 9—figure supplement 2, sixth row) or in combination with the NTD (Figure 8—figure supplement 3 and Figure 9—figure supplement 2, seventh row). These findings suggest that altered non-cognate interactions between the transplanted NTD:NBD1 unit and the native ScMD can elicit off-target toxicity (Sweeny et al., 2020). Curiously, non-cognate interactions between a transplanted MD and the native ScNTD:NBD1 unit does not elicit that same effect. Thus, we suggest that the NTD:NBD1 unit plays a dominant role in regulating Hsp104.

Select chimeras mimic potentiated ScHsp104 variants to suppress αSyn toxicity

Interestingly, two chimeras consisting of cognate NTD:NBD1 pairs fused to MD:NBD2:CTD from ScHsp104 unexpectedly suppressed αSyn toxicity. First, a chimera consisting of the CtHsp104 NTD and NBD1 fused to the ScHsp104 MD, NBD2, and CTD suppressed αSyn toxicity even more strongly than CtHsp104WT (Figure 9F). Similarly, a chimera consisting of the PeHsp104 NTD and NBD1 fused to the ScHsp104 MD, NBD2, and CTD reduced αSyn toxicity (Figure 8—figure supplement 2D). This finding was particularly unexpected because full-length PeHsp104 is specific to TDP-43, and this same chimera is inactive against TDP-43 (Figure 8E). Both of these chimeras were toxic to yeast when expressed alone at 37°C (Figure 8—figure supplement 3D and Figure 9—figure supplement 2A, boxed). Thus, in these cases, disruption of interaction between the transplanted NTD:NBD1 unit and the ScMD appears to mimic potentiated ScHsp104 variants and enables suppression of αSyn toxicity. Indeed, mutations in ScHsp104 NTD and NBD1 that disrupt interactions with the MD can potentiate activity (Mack et al., 2020; Sweeny et al., 2020; Tariq et al., 2019; Ye et al., 2020).

Discussion

Here, we used yeast toxicity models to identify naturally occurring Hsp104 homologs, from diverse hosts, capable of buffering proteotoxicity of several proteins implicated in human neurodegenerative diseases. Among the prokaryotic homologs we tested, ClpB and hyperactive variants were inutile, whereas ClpG mitigated TDP-43, FUS, and αSyn toxicity. By contrast, eukaryotic Hsp104 homologs emerged that selectively suppressed TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity in yeast. Excitingly, eukaryotic Hsp104 homologs that selectively suppress TDP-43 toxicity in yeast also suppress TDP-43 aggregation in human cells. Likewise, eukaryotic Hsp104 homologs that selectively suppress αSyn toxicity in yeast also suppress αSyn toxicity-induced neurodegeneration in C. elegans. Thus, we suggest that, like previously-defined potentiated Hsp104 variants (Jackrel et al., 2014; Mack et al., 2020), these naturally-occurring Hsp104 variants may be able to mitigate proteotoxicity in a wide variety of circumstances, including in metazoan systems.

Several features of the eukaryotic Hsp104 homologs presented here contrast with potentiated Hsp104 variants. Eukaryotic Hsp104 homologs are substrate-specific and typically only suppress either TDP-43 or αSyn toxicity (the exception is CtHsp104). Indeed, we did not isolate any eukaryotic Hsp104 homologs capable of suppressing FUS toxicity. In contrast, potentiated Hsp104 variants typically are able to suppress toxicity of multiple toxic substrates (Jackrel et al., 2014; Jackrel and Shorter, 2014; Jackrel et al., 2015; Tariq et al., 2019; Tariq et al., 2018). Natural Hsp104 homologs also displayed no intrinsic toxicity (with the exception of PfHsp104), even when expressed at elevated temperatures. Thus, extant Hsp104 homologs have likely been filtered through natural selection to avoid deleterious and destabilizing sequences. In contrast, potentiated Hsp104 variants have predominantly been engineered by destabilizing the NBD1:MD interface (Jackrel et al., 2014; Jackrel et al., 2015; Sweeny et al., 2020; Tariq et al., 2019; Tariq et al., 2018; Ye et al., 2020). This difference is further reflected in fundamental mechanistic differences between how the eukaryotic Hsp104 homologs described here and potentiated Hsp104 variants operate to antagonize proteotoxic misfolding. Engineered Hsp104 variants are generally enhanced disaggregases (Jackrel et al., 2014; Jackrel and Shorter, 2014; Jackrel et al., 2015; Tariq et al., 2018). We hypothesize that in some cases these enhanced disaggregase and unfoldase activities may come at the cost of substrate specificity (e.g. by mistargeting natively-folded complexes for disassembly), analogous to trade-offs between speed and fidelity observed in other NTPase molecular machines, such as RNA polymerases (Fitzsimmons et al., 2018). However, the eukaryotic Hsp104 homologs presented here are not similarly enhanced disaggregases, and in fact do not require disaggregase activity to antagonize proteotoxic misfolding of TDP-43 or αSyn. Rather, they appear to act in an ATP-independent manner to inhibit protein aggregation and suppress toxicity of specific substrates.

The dual role of Hsp104 as a molecular chaperone capable of preventing aggregation in addition to a disaggregase capable of reversing protein aggregation has long been appreciated (Shorter and Lindquist, 2004; Shorter and Lindquist, 2006). Both of these activities require ATPase activity for maximum effect, although disaggregase activity is much more sensitive to reduced ATPase activity than inhibition of aggregation (Shorter and Lindquist, 2004; Shorter and Lindquist, 2006). Here, we find that diverse eukaryotic Hsp104 homologs suppress toxicity of select substrates in a manner that requires neither active ATPase domains nor substrate engagement by the canonical pore loops. Rather, we have uncovered genetic variation outside of these core AAA+ features that enables molecular recognition of specific substrates. Thus, in future work it will be important to tune this genetic variation to create designer disaggregases with highly specific molecular recognition. Indeed, we envision making modular disaggregases by combining potentiating mutations with molecular-recognition motifs to generate Hsp104 variants with enhanced specificity and disaggregase activity.

What sequence determinants of eukaryotic Hsp104 homologs enable their toxicity-suppression phenotypes? Hsp104 homologs that selectively suppress TDP-43 toxicity or selectively suppress αSyn toxicity are more similar to each other than between groups (average sequence identities of 56%, 76%, and 44%, respectively; Supplementary file 2 and Figure 2—figure supplement 2B). To further address this question, we first tested the effect of deleting the NTD on the toxicity-suppression phenotypes associated with Hsp104 homologs (Figure 7). We observed that suppression of TDP-43 toxicity by MbHsp104 and CrHsp104, and suppression of αSyn toxicity by TtHsp104, depends on the presence of the NTD of these homologs (Figure 7). The ScHsp104 NTD enables many aspects of ScHsp104 function, including hexamer cooperativity, substrate binding, amyloid dissolution, and proteotoxicity suppression by potentiated Hsp104 variants (Sweeny et al., 2015; Sweeny et al., 2020). We suggest that the NTD-dependent rescue phenotypes we observed may reflect a role of the NTD in collaboration with other cognate domains to enable effective substrate engagement.