Abstract

Patient experience is increasingly recognized as a measure of health care quality and patient-centered care and is currently measured through the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS). The HCAHPS survey may miss key factors important to patients, and in particular, to underserved patient populations. We performed a qualitative study utilizing semi-structured interviews with 45 hospitalized English- and Spanish-speaking patients and 6 focus groups with physicians, nurses, and administrators at a large, urban safety-net hospital. Four main themes were important to patients: (1) the hospital environment including cleanliness and how hospital policies and procedures impact patients’ perceived autonomy, (2) whole-person care, (3) communication with and between care teams and utilizing words that patients can understand, and (4) responsiveness and attentiveness to needs. We found that several key themes that were important to patients are not fully addressed in the HCAHPS survey and there is a disconnect between what patients and care teams believe patients want and what hospital policies drive in the care environment.

Keywords: patient expectations, patient engagement, patient feedback, patient, satisfaction

Introduction

Patient experience has been described as a cornerstone of high-value, high-quality health care (1). Institutions with higher measures of patient experience tend to score higher overall on measures of quality (2 -12). Over a decade ago, the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) was developed, and in 2010, it was deployed across US hospitals. However, because of issues with response rates, the length of the survey, and the fact that it might not cover key areas deemed important by patients, some experts are calling for a revision to the current HCAHPS framework (13,14).

The HCAHPS has a robust development history including guided focus groups dating back to the late 1990s and early 2000s (15 -17). However, these focus groups primarily included Medicare patients from relatively educated backgrounds and with limited diversity. Despite its robust upbringing, many questions exist about the best way to apply it and whether or not the various versions of HCAHPS may have inherent biases (18 -23). Additionally, over time, trends in hospitalization and patient expectations of care may have evolved.

It has been suggested that hospital care will advance by learning from patients and their families and involving them in efforts to monitor and improve care (24). Accordingly, we aimed to (1) explore concepts identified by hospitalized patients as being important to them during hospitalization, (2) explore concepts believed by physicians, nurses, and administrators to be important to patients during hospitalization, and (3) identify gaps and similarities between patient and health care professional perceptions and expectations.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted 45 semi-structured interviews with hospitalized patients and family members or caregivers and 6 focus groups with hospital-based health care professionals. The project period, including study design and implementation, interviews and focus groups, and analysis, was from October 2015 to August 2018. Focus groups with health care professionals were held from November 2016 to July 2017. Semi-structured interviews with hospitalized patients and their families were held from March 2016 to May 2017. Interviews with patients and focus groups with health care professionals occurred, for the most part, concurrently.

Setting and Participants

The study was conducted at a 525-bed safety-net hospital in Denver, Colorado. We used stratified purposeful typical case sampling to identify eligible hospitalized patients. Approximately 15% of Denver Health patients speak a language other than English, a large majority being Spanish and thus we sought to ensure that the distribution of patients, by age, gender, race/ethnicity, language, primary payer, and length of stay, was representative of the Denver Health patient population. We included Spanish-speaking patients as previous work has shown disparities in non-English-speaking groups with regard to patient experience. While we did not use patient education as a part of our sampling strategy because these data are not typically collected as a part of clinical care, our patient sample reflected the typical patient hospitalized at Denver Health. Eligible patients were adult English- or Spanish-speaking patients on an inpatient medical service, identified daily using a screening tool built within the electronic health record. Eligible health care professionals were physicians, nurses, nurse managers, mid-level administrators, and executives either directly involved in caring for hospitalized patients or responsible for patient experience and employed by the hospital. Patients or health care professionals who refused to participate, patients who lacked decisional capacity as determined by their primary care team, patients with hearing or speech impediments that precluded regular conversation, patients on hospice/comfort care, pregnant patients, and prisoners were excluded. Participants were recruited using in-person invitations for hospitalized patients and email/phone call invitations for health care personnel. Stratified purposeful typical case sampling was used to identify hospitalized patients. Patients without any exclusion criteria were invited after the second day of their hospitalization to participate in the study. Health care professionals were recruited using convenience sampling methods.

Patients and family members present were consented and interviewed in the patient’s private or semi-private hospital room. Spanish-speaking patients and family members present during the interview were consented and interviewed in Spanish by interviewers fluent in Spanish. Health care professionals were consented as a group, and focus groups were conducted in a private conference room.

Interview Guide

Semi-structured interviews with patients and family members present used open-ended questions to explore key attributes of an ideal experience during hospitalization. Focus groups used open-ended questions to explore what health care professionals believed patients felt was important during hospitalization. Questions were derived from HCAHPS survey domains and literature reviews. Interview and focus group guides are presented in Online Supplement 1. The ultimate purpose of our study was to inductively explore the perceptions of patients, physicians, nurses, and administrators with the goal of developing a conceptual framework from the themes and subthemes identified, and thus the semi-structured interview questionnaire served as a guide to start the conversation with patients and focus group participants.

Data Collection

Eligible patients were identified and consented by 1 of the 2 investigators (H.H. and L.M.) and interviewed by 1 of the 6 investigators (S.N., K.I., M.F., S.S., I.Q., and M.B.). Neither the interviewer nor any observers were wearing a white physician’s coat during interviews with patients and were not a member of the patient’s care team. Focus groups were led by 1 of the 4 investigators (S.N., S.S., M.B., and M.F.). Physicians, nurses, nurse managers, mid-managers, and executives were interviewed in separate focus groups to mitigate any group dynamic issues that could arise from potential power differentials. Two investigators (H.H. and L.M.) observed and augmented interview and focus group transcripts with written notes. Recruitment of participants was halted when no new codes or themes emerged during the analysis.

Interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded, de-identified, professionally translated, and transcribed. Any identifiers inadvertently captured on the audio files were removed during professional transcription and not retained in any way.

Analysis

Transcribed interviews and focus groups were coded by 3 study team members (A.K., H.H., and L.M.) using Atlas.ti software (version 7.5.6, Scientific Software Development GmbH). Disagreements in coding were discussed until a consensus was reached. A thematic analysis was conducted using an inductive method at the semantic level (25). Consensus across 6 team members (S.N., A.K., K.I., S.S., H.H., and L.M.) was reached through independent review of the interview and focus group data along with regular meetings to discuss identified themes and subthemes. A synthesis of results emerging from focus group analysis was summarized and compared to the qualitative results gleaned from the patient interviews with the goal of identifying congruent and dissonant themes.

Results

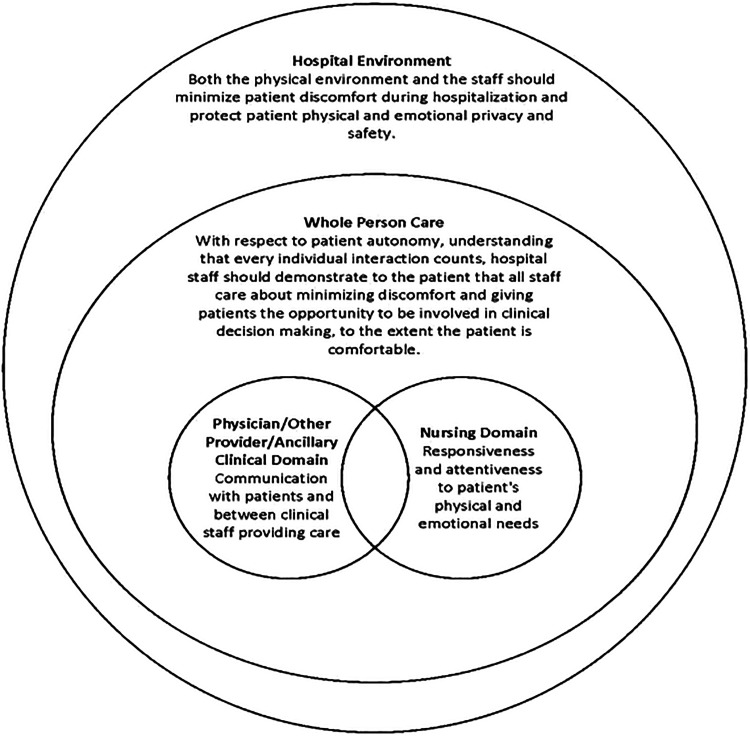

We approached 62 patients and interviewed 45 patients from March 22, 2016, to May 15, 2017. Forty-nine patients consented, with 4 subsequently excluded following consent. Thirteen patients declined or were excluded prior to consent. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the patients interviewed. Patient participants described 4 domains during their hospitalization that were important to them: (1) hospital environment including cleanliness and impact of hospital policies on patient autonomy, (2) whole-person care, (3) communication with and across care teams with words that patients can understand, and (4) responsiveness and attentiveness. Figure 1 presents a conceptual framework derived from the themes and subthemes from the patient and family interviews. Table 2 provides additional illustrative quotations for the themes and subthemes informing our conceptual framework.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics.

| Demographic value | English-speaking | Spanish-speaking |

|---|---|---|

| N = 22 | N = 23 | |

| Age | ||

| 18-29 | 3 (14) | 0 (0) |

| 30-39 | 1 (4) | 5 (22) |

| 40-49 | 2 (9) | 5 (22) |

| 50-59 | 8 (36) | 4 (17) |

| 60-69 | 5 (23) | 4 (17) |

| 70-79 | 3 (14) | 3 (13) |

| 80-89 | 0 (0) | 2 (9) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 14 (64) | 11 (48) |

| Male | 8 (36) | 12 (52) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black | 4 (18) | 0 (0) |

| Hispanic | 11 (50) | 23 (100) |

| White | 7 (32) | 0 (0) |

| Payer | ||

| Medically indigent | 1 (4.5) | 14 (61) |

| Medicaid | 11 (50) | 1 (4.5) |

| Medicare | 9 (41) | 7 (30) |

| Commercial/Denver Health Medical Plan | 1 (4.5) | 1 (4.5) |

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for patient interview themes and subthemes.

Table 2.

Patient and Family Themes and Subthemes With Exemplar Quotations.

| Theme and subthemes | Quotations |

|---|---|

| Hospital environments influence how patients perceive their care | |

| Importance of cleanliness of environment | “Nobody came to clean my room the whole weekend that I was there. For my whole stay. I thought that was awful because you know—without a clean room you’re bound to get infection. So I told my best friend and I guess he took care of it for me. I didn’t want to get nobody in trouble.” (patient 49) |

| Hospital rules, policies, and procedures affect patient perceptions of autonomy and contradict patient preferences |

“The doctors are discussing your personal business and here, this person over here listening [referring to roommate]. Like oh, you know. That’s not good. Isn’t that a compromise issue of doctor and patient information? What if she knows somebody that doesn’t like me? You can put a whole bunch of stuff on Facebook.” (patient 23) “The laboratory keeps coming in poking me when I’m telling them that I don’t have any more veins, and I’m all bruised up and they like just come and poke me and they expect that like you know I’m fine with it.” (patient 42) “But there are some things that bother me. I don’t like them, but perhaps it’s for my own good, so it won’t hurt me or it has to be due to my health, for my own good. They come here, they wake me up all the time, or I ask for a meal they can’t send me and they send over whatever they want.” (patient 34) |

| Whole person care that is patient-centered | |

| Importance of patient-centered care | “They actually come in and talk to you; you know the palliative care and the social workers and things like that. You actually see them before the medical team gets here in the morning. They send one of the people out and he gives you like an overview of what you’re going to be talking about. And then a little while later the whole team comes in so you’re not caught off guard about anything.” (patient 35) “The noise, the lighting and none of that bothers me. When I go to sleep I sleep but, for example, last night I was very sick and they didn’t let my wife stay over because we’re two men sharing the room. Well, I needed to have my wife there beside me, you understand?” (patient 45) |

| Seeing the patient as human, taking measures to avoid dehumanization | “They treat you like you’re a person. Like you’re worthy.” (patient 14) “The team here, I feel like they really care. And I feel like someone you know, not just a number to them.” (16) |

| Treating patients with empathy | “Then when I was in the bathroom I called for some help getting out, and I didn’t really get the help I was looking for. I could tell she just didn’t want to do it. It is hit and miss. It all depends on who’s working that day and what their work ethic and personality is.” (patient 43) “I haven’t been mistreated, not a bad looking face, nothing, nothing. On the contrary, we’re going to help you, we support you, you’re going to make it, this disease is no longer a negative one, it’s just like any other illness, you can live 32, 33 more years, like nothing is happening, you can have kids, you can have a family and I’m like…I mean, they took the negative stuff I had away from the disease.” (patient 26) |

| Clear communication with patient and care team | |

| Communicating in a way that patients can understand |

“First they talk among them, I don’t know the situation they’re seeing, everything, they come in, they talk to me, they listen to me lungs, they check up on me, whatever they must do, and sometimes among them they also talk a bit more, well, this is what will do, basically they consider this in group when the patient is there with them so that the patient will also know what’s happening, not just they come in and they say you’re going to use this blue drainer [references a medical device] and that’s it, go. They tell you, look, they’re going to give you this [references a medical device] for this and this and this reason. And we see this is the best thing for you but we also want to know how you feel about it. So they take you into account.” (patient 27) |

| Care teams need to communicate with each other | “I feel like it’s all communicated. I let them do the medical decisions, they’re smart. But they go over everything and the whole team comes. With the pharmacy, also three doctors come in here in the morning and they ask me. And we’re all on the same page with it. It’s so clear and I have an understanding of everything. It’s just real nice.” (patient 16) |

| Responsiveness and attentiveness | |

| Attention to patient’s physical and emotional needs | “The same way if it’s not ringing or not answering and you feel like you want to pee and you press it, nobody answers. You just have to keep on pressing it until somebody answers and I want to pee. I’ve peed myself already. I have to keep on pressing until somebody answers.” (patient 36) “Well, very good. See, last night one of them gave me a bath and please I’d like to take a bath but they don’t have a small chair so I can take a bath, oh, I’ll help you with your bath right now. And she went, she prepared the bath, she helped me take a bath and get dressed, what else can I ask?” (Patient 33) “I went to go get a CAT scan. The transportation lady, you know she—they put you in the wheelchair and they take you down there. I didn’t like how she pretty much just stuck me in the hallway when there’s a waiting area right there…? Yeah, there was men doing a lot of construction, and I had a really bad headache and I couldn’t—I was connected to all these, I call the leash. I couldn’t get up and move myself. I would like you know if there’s a waiting area right there, you know just to put patients that are waiting in a—that’s why it’s called the waiting room.” (patient 38) |

| Worthiness of care | |

| Past choices leading to blame and passivity in care |

“Once he comes in the morning [referring to provider], I don’t like to bother him again. I know he’s got a lot of other patients worse off than me. I feel like I ain’t worth it sometimes…probably because of the life I led, the drugs I’ve done and the way I’ve acted and—up to no good and stuff I guess.” (patient 3) |

Patient Themes

The Hospital Environment Influences How Patients Perceive Their Care

Hospital policies and procedures affect patient perceptions of autonomy and may contradict patient preferences

Participants described a lack of control, helplessness, lack of self-advocacy, and vulnerability during their hospitalization. Dependency on staff due to their physical limitations, hospital rules, and inconsistent staff response time made the hospital experience frustrating and intensified feelings of loss of control and vulnerability. Patients perceived that the priorities of the hospital (rules, policies, and procedures) were not in sync with patients’ preferences and that the hospital did not consider the patient when scheduling clinical activities such as rounding times, procedures, and blood draws. Patients suggested that hospitals should better align clinical workflows and care processes with patient comfort, rather than hospital staff convenience, as the primary motivator.

Lack of privacy was identified as a critical concern by patients and having to share hospital rooms with other sick patients was viewed as a lack of respect for patients and their privacy. Patients who reported having a roommate were particularly concerned about confidentiality, with respect to sensitive medical and psychiatric information. Disrupted sleep, noise, nudity of the room partners, and sharing the restroom with another ill person added additional stress to the patients.

Importance of cleanliness of the environment

The hospital environment (comfort, cleanliness, and privacy) was seen as a surrogate for how patients would be treated while hospitalized. Patients noted they were relieved when they saw that staff made efforts to keep the environment clean and patients as comfortable as possible. Many patients viewed factors such as a functional television, lights in accessible locations, consistent cleaning services, family being allowed to stay overnight, and quality of the food as important environmental factors that play a role in their comfort and well-being.

Whole Person Care With the Patient at the Center

Importance of patient-centered care

Participants described a desire for their hospital care providers to honor their preferences regarding autonomy and level of their own involvement in their care. Preferences varied regarding shared decision-making—some of the patients wanted to know less, while others wanted to know more. Some patients reported feeling comfortable deferring clinical decisions to clinical staff but wanted to understand the plan of care, thereby balancing the power dynamics between patients and their care team.

Seeing the patient as human, taking measures to avoid dehumanization, and treating patients with empathy

Patients described a strong desire for a human connection with their nurses, doctors, and other hospital staff. Patients saw even small gestures of kindness, such as calling their employer on their behalf to request sick days or finding a family member’s phone number, as going above and beyond the usual standard of care. Patients desired hospital staff to be resilient and pleasant, to appear to enjoy their jobs, to answer patients’ and families’ questions, to listen to patients, and to explain things in a way that patients and their families can understand. Patients perceived that what differentiates average care from exceptional care is looking beyond the tubes and machines to recognize that there is a human being behind them and treating patients like more than just a number.

Clear Communication Between the Patient and Care Team

Care teams need to communicate with each other

Receiving contradictory messages from different clinicians providing care was frustrating for patients. Patients perceived that the delays in procedures and changes in care plans reflected disorganization and conflict among the health care providers. Participants described wanting clear, consistent, and coordinated communication.

Communicating with words patients understand

Participants expressed wanting clinical staff to clearly explain their disease and treatment plan in a way that they understand. While patients did not mind clinical staff using medical terminology at the bedside, they expected that clinical staff would take the time to communicate with them in layman’s terms. While most participants expressed that they lacked a clear understanding of their disease due to an underlying lack of medical knowledge, they perceived that clinical staff could bridge this gap by taking time to explain information well.

Responsiveness and Attentiveness

Attention to patient’s physical and emotional needs

Patients noted that they expect respect, kindness, and attentiveness from their care team. Some described experiencing delays and inconsistencies in responsiveness to the call light and to their basic needs. Furthermore, having clear and accurate expectations regarding waiting times and other delays is important so patients are not left wondering about the status of their request or their clinical care. Participants noted that when immediate or anticipatory care did occur, it positively affected their experience. Participants further described a sense of emotional safety when staff had a confident demeanor and positive attitude and paused to take time to interact with patients as human beings.

Worthiness of Care

Past choices leading to self-blame and passivity in care

Due to their choices in the past, some participants blamed themselves for their disease and therefore tolerated suboptimal treatment in the hospital. They did not see themselves as worthy of better treatment and they were embarrassed to demand more from their care providers. Many participants did not speak up due to embarrassment, helplessness, lack of self-advocacy, a feeling of not wanting to get anyone in trouble, worrying that their care would be affected negatively, or not wanting to be a burden to the staff.

Focus Groups

Six focus groups were conducted with a total of 45 participants. The focus groups included 13 attending physicians, 10 nursing staff, 15 managers, and 7 executives. Administrators, physicians, and nurses were interviewed separately.

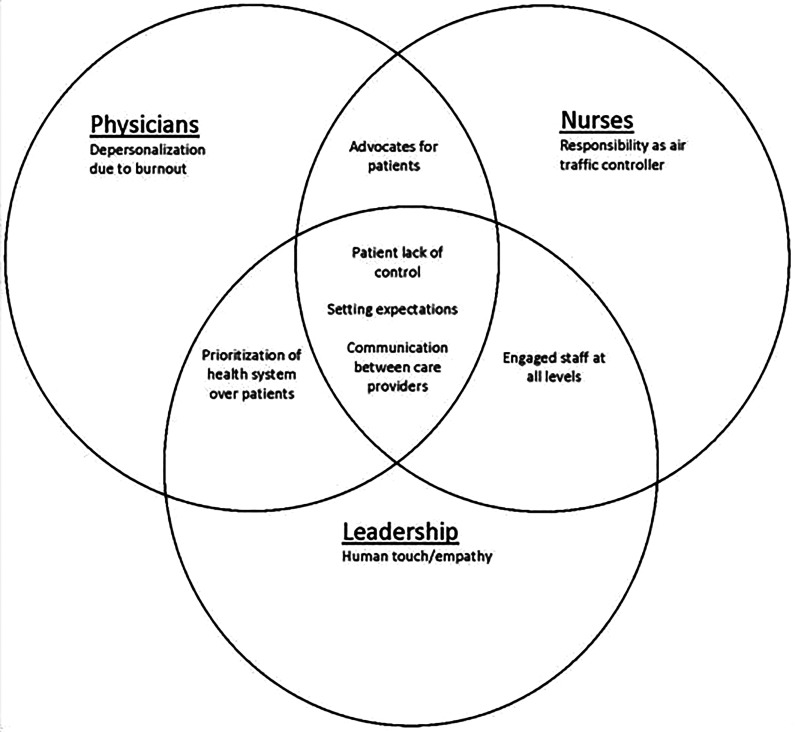

Several themes noted by patients such as lack of control, communication between care providers, empathy, staff engagement, expectation setting, and prioritization of health system goals over individual patients were also noted in the focus groups of physicians, nurses, and administrators. Online Supplement 2 provides illustrative quotations for the themes and subthemes identified. Figure 2 provides a diagram for the themes and subthemes from the focus groups highlighting commonalities between types of health care professionals and unique themes identified.

Figure 2.

Diagram of focus groups’ themes and subthemes.

While the themes from patient interviews and focus groups were similar, the physician focus group noted that despite feeling like they know what patients and families genuinely want and need while hospitalized, depersonalization occurs due to the stress of busy day-to-day work schedules and burnout from an unsustainable workload. The concept of having to direct or coordinate care was a unique finding from the nurse focus group, while health care administrators described the need for human touch and empathy from clinical staff when hospitalized.

Discussion

The most important findings of this study are (1) patients identified factors that are not currently captured in the HCAHPS surveys, such as how hospital policies and procedures impact their perceived autonomy, that whole-person care is important, and the need for cohesive communication between care team members; (2) while physicians, nurses, and administrators can articulate what patients find most important, patients’ experiences and staff focus groups indicate that hospitals struggle to bridge the gap between understanding patient needs and actually meeting those needs; (3) physicians noted that despite feeling like they know what patients and families genuinely want and need while hospitalized, depersonalization occurs due to the stress of busy day-to-day work schedules and burnout from an unsustainable workload; and (4) there is a subgroup of patients who expressed feeling a lack of worthiness and a reluctance to self-advocate.

The HCAHPS development began as early as the 1990s through a variety of focus groups, but these focus groups had several limitations, as they asked patients to recall hospitalizations as long as 1 year prior and utilized questions tailored to address a battery of ∼66 items (15 -17). Recent articles have cited the concerns that HCAHPS may not adequately cover key areas important to patients and has several logistical issues including length of the survey and high literacy level (13).

We found several domains not covered in the current HCAHPS survey that are likely important to high-quality care. These include hospital policies adversely impacting patient autonomy (26), communication between care teams (27), and whole-person care (28). With regard to policies, a variety of policies and procedures were referenced by patients, including the timing of procedures and when a patient is or is not allowed to eat/drink, visitation policies, and room sharing policies. Many of the references of policies by patients centered on patients reporting they felt as though they lacked autonomy and control. The lack of privacy due to having to share rooms is not new knowledge, with other studies reporting this same finding; however, to our knowledge, the HCAHPS survey does not include questions asking about privacy or whether the patient was in a shared room or not. While the HCAHPS survey includes questions exploring how nurses and physicians communicated with the patient, the HCAHPS survey instrument does not include questions about how the patient perceives the care team members communicated with each other. Our study corroborates the need to continue to ask patients about how they perceived nurses and physicians communicated with them and suggests there is also a need to ask patients how they perceived care team members communicated with each other about their care. Some of these domains could be incorporated into future surveys (ie, how well did your care team communicate with each other and how did hospital policies affect your hospital stay). Some of the confusion around hospital policies could likely be mitigated with improved patient-centered communication around patient preferences and an understanding of safety protocols.

In our safety-net population, we also found that certain patients may not feel worthy of advocating for themselves in particular when feeling that their illness may be due to previous poor choices. While this finding was noted in a smaller group of patients (N =3), this phenomenon may be more prevalent in hospital settings that serve underserved populations and thus may be a future area to potentially focus on. Additionally, we may have captured unique perspectives by interviewing patients in person during their hospitalization, as the lack of a reliable phone number or address may preclude some of our most vulnerable patients from responding to the HCAHPS survey. Our finding on whole-person care is similar to a recent study that reported that person-focused interventions could improve the patient experience (28). Recently published articles support the finding that hospital policies affect patient experience, and those policies need to be patient-centric and flexible (26). Similarly, another study found that patients in private rooms are more likely to report a top-box score for overall hospital rating, hospital recommendation, call button help, and quietness in HCAHPS (29).

We found that many of the themes noted by patients (lack of control, communication between care providers, empathy, staff engagement, expectation setting, and health system priorities) were also noted by health care professionals. In addition, we noted there were some unique themes identified during focus groups with physicians, nurses, and administrators. In particular, administrators described the need for human touch and empathy from health care staff when hospitalized. The concept of having to direct or coordinate care was a unique finding from the nurse focus group, while the concept of depersonalization and burnout was a unique finding from the physician focus groups. The health care professionals who agreed to participate in our focus groups came from a cross-section of units and departments. Depersonalization and burnout reported by the physicians who participated in our study are findings that have been described in the literature by other researchers and may serve as an explanation for why physicians feel unable to completely meet the needs of patients. Interestingly, focus group results illustrated that health care professionals’ own experience as a patient (or a patient’s family member) imparts an understanding that they are able to apply to their own work caring for patients. This concept is mirrored in perspective pieces published by clinicians (30). Our findings suggest that while health care professionals appear to have a genuine understanding of what patients want and need during their hospitalization, this awareness does not always translate into reliable fulfillment of these needs and wants as experienced by hospitalized patients.

Although the ideas expressed by health care professionals were mostly congruent with those expressed by patients, the experiences relayed by patients point to a gap in translating these ideas into clinical practice. Future work should be directed at understanding the reasons for this gap between health care professionals’ knowledge and everyday practice. For instance, it is plausible that clinical workload, cognitive load, competing demands, burnout, or systems factors may explain why these behaviors are not always modeled in daily practice.

Our findings also highlight the role of system-level barriers in hindering the patient-centeredness of policies and procedures that patients, families, caregivers, clinical staff, and administrators all deem important. Modifying policies and procedures governing activities such as clinical rounding, scheduling of procedures, and timing of blood draws would require a system-level change in hospital operations, which is challenging to execute. While certain policies protect our patients and families, others are likely detrimental to patients who are trying to heal, such as those that interrupt patient sleep or disallow patients from having family members or caregivers stay with them overnight. The need for standardized yet flexible processes has been recognized as a key strategic framework in patient-centered care (31). To stay competitive, health care organizations need to develop effective and efficient processes that are patient-centered, informed by the newest models of operation management and research, and designed for our patients and families.

Our study had several limitations. This study aimed to describe the experiences of patients, caregivers, and health care professionals at a safety-net hospital, and thus the results may not be applicable in other settings. In addition, there was a potential for participation bias if patients who declined to participate were different in some way from those who agreed to participate. Due to using a convenience sample for the focus groups, there is also a potential for selection bias among the health care professionals included in the study. Also, patients who did not speak English or Spanish were excluded from this study, and these patients may have had different experiences. We recognize that patient experience may vary according to language, race/ethnicity, or other cultural factors; however, this analysis was intended to propose a high-level framework. Future work should be conducted to explore these potential differences. Conducting the patient interviews while the patients were still hospitalized may have inhibited patients’ willingness to fully disclose their perceptions regarding their experience. They also would not have experienced the discharge process during that respective hospitalization and thus the needs around the discharge and transition process are not addressed in this study. Finally, interviews and focus groups were conducted by physicians, which could have influenced participant disclosures. However, to mitigate this potential issue, neither interviewers nor observers wore a white physician’s coat during interviews with patients or focus groups.

Our study also has several strengths. Because we interviewed patients during their hospital stay, their experience of hospital care was likely very real and fresh on their minds. We included both English- and Spanish-speaking patients, and the interviews were conducted by native English and Spanish speakers. This work incorporates a more diverse and underserved population than the original focus groups described by Sofaer et al., which included a predominantly white population (62.8%) and 57% of the participants had at least some college or 2-year degree or vocational school or higher education. Educational levels for the population who responded to HCAHPS at our institution was high school. We also sought the perspectives of the clinician and administrative team, which we believe are also important to understand. Few studies have paired patient, care team, and administrative perspectives.

Conclusions

We found several critical themes among hospitalized patients that are not currently captured in standard patient experience assessments. We found that there is a disconnect between what patients and clinical staff believe patients need and want and what hospital policies and environments drive in the care environment. Certain vulnerable populations may be less inclined to self-advocate regarding their needs, and additional measures may need to be taken to ensure the needs are met.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, WDPWSupplement1 for What Do Patients Want? A Qualitative Analysis of Patient, Provider, and Administrative Perceptions and Expectations About Patients’ Hospital Stays by Sansrita Nepal, Angela Keniston, Kimberly A Indovina, Maria G Frank, Sarah A Stella, Itziar Quinzanos-Alonso, Lauren McBeth, Susan L Moore and Marisha Burden in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental Material, WDPWSupplement_2 for What Do Patients Want? A Qualitative Analysis of Patient, Provider, and Administrative Perceptions and Expectations About Patients’ Hospital Stays by Sansrita Nepal, Angela Keniston, Kimberly A Indovina, Maria G Frank, Sarah A Stella, Itziar Quinzanos-Alonso, Lauren McBeth, Susan L Moore and Marisha Burden in Journal of Patient Experience

Author Biographies

Sansrita Nepal, MD, MBA, works as a hospitalist at Denver Health and is an assistant professor of Medicine at the University of Colorado. Her research interests include patient experience and resident education. She has an MBA in healthcare administration.

Angela Keniston, MSPH, is the director of Data and Analytics for the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Colorado. She has expertise in research design, mixed methods approaches, qualitative and quantitative methods, data collection, management and analysis, user-centered design, and stakeholder engagement planning and execution. She has worked for the last 15 years exploring how care for hospitalized patients, and how patients and families experience care during a hospitalization, might be improved, in particular for vulnerable, socio-economically disadvantaged patients.

Kimberly A Indovina, MD, is an assistant professor of Medicine at the University of Colorado and practices hospital medicine and palliative medicine at Denver Health.

Maria G Frank, MD, is a hospitalist and medical director of the Biocontainment Unit at Denver Health Hospital Authority. She is an associate professor of Medicine at the University of Colorado, School of Medicine.

Sarah A Stella, MD, is an internal medicine hospitalist at Denver Health and an associate professor of Medicine at the University of Colorado. She is passionate about improving health outcomes among patients with complex medical and social needs through community partnered research, healthcare systems improvement work, and advocacy.

Itziar Quinzanos-Alonso, MD, is an instructor of Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology. Working in the Rheumatology department at Denver Heath. A native of Mexico, her area of research expertise in underserved communities. Specifically, working with her colleagues at Denver Health she has focused on health literacy.

Lauren McBeth, BA, is a project coordinator and data analyst on the Data and Analytics team for the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Colorado Denver. She received her Bachelor of Arts in Psychology with an emphasis in Neuroscience from Concordia College in Moorhead, MN and has spent the last five years compiling and analyzing both quantitative and qualitative data for the purposes of improving patient care in the hospital inpatient setting.

Susan L Moore, PhD, MSPH, is an associate director at mHealth Impact Lab. She is the core lead at the Adult and Child Consortiuan for Health Outcomes Research (ACCORDS). She works at the Colorado School of Public Health and University of Colorado.

Marisha Burden, MD, is an academic hospitalist and division head of Hospital Medicine and, an associate professor of Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. She completed her undergraduate training at the University of Oklahoma and earned her medical degree from the University of Oklahoma School of Medicine graduating with the honor of Alpha Omega Alpha. She completed her residency at the University of Colorado in the hospitalist training track. Her interests include hospital systems improvement, which includes patient experience, patient flow, quality, and transitions of care. She is also very interested in promoting gender equity and is a member of the Department of Medicine Program to Advance Gender Equity and the AAMC Group on Women in Medicine and Science (GWIMS) Equity in Recruitment Task Force. She is an active member of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) and a senior fellow of Hospital Medicine.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The study was reviewed and approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB), University of Colorado, Denver. Written consent was obtained from all participants prior to conducting any interviews or focus groups and all participants received a copy of the consent form. Sansrita Nepal and Angela Keniston are co-first authors.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded for $25,000 through Department of Medicine Small Grant and $25,000 through Denver Health Foundation.

ORCID iD: Sansrita Nepal, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6951-7778

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6951-7778

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Kneeland PP, Burden M. Web exclusives. Annals for hospitalists inpatient notes—patient experience as a health care value domain in hospitals. Ann Int Med. 2018;168:HO2–HO3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bardach NS, Asteria-Penaloza R, Boscardin WJ, Dudley RA. The relationship between commercial website ratings and traditional hospital performance measures in the USA. BMJ Qual Safety. 2013;22:194–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alazri MH, Neal RD. The association between satisfaction with services provided in primary care and outcomes in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2003;20:486–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:41–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Girotra S, Cram P, Popescu I. Patient satisfaction at America’s lowest performing hospitals. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:365–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Glickman SW, Boulding W, Manary M, Richard S, Matthew TR, Robert JW, et al. Patient satisfaction and its relationship with clinical quality and inpatient mortality in acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:188–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Greaves F, Pape UJ, King D, Ara D, Azeem M, Robert MW, et al. Associations between Web-based patient ratings and objective measures of hospital quality. Ann Int Med. 2012;172:435–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Isaac T, Zaslavsky AM, Cleary PD, Landon BE. The relationship between patients’ perception of care and measures of hospital quality and safety. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:1024–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1921–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Narayan KM, Gregg EW, Fagot-Campagna A, Tiffany LG, Jinan BS, Corette P, et al. Relationship between quality of diabetes care and patient satisfaction. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95:64–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stein SM, Day M, Karia R, Hutzler L, Bosco JA., 3rd Patients’ perceptions of care are associated with quality of hospital care: a survey of 4605 hospitals. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30:382–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salzberg C, Kahn C, III, Foster N, Demehin A, Guinan M, Ramsey P, et al. Modernizing the HCAHPS Survey. 2019. Accessed November 22, 2019 https://www.aha.org/guidesreports/2019-07-24-modernizing-hcahps-survey

- 14. Pfeifer GM. Is it time to revise HCAHPS? Am J Nurs. 2019;119:14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sofaer S, Crofton C, Goldstein E, Hoy E, Crabb J. What do consumers want to know about the quality of care in hospitals? Health Serv Res. 2005;40:2018–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shaller D, Sofaer S, Findlay SD, Hibbard JH, Lansky D, Delbanco S. Consumers and quality-driven health care: a call to action. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;22:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cleary PD, Edgman-Levitan S. Health care quality. Incorporating consumer perspectives. JAMA. 1997;278:1608–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cleveland Clinic Orthopaedic Arthroplasty G. Press Ganey administration of hospital consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems survey result in a biased responder sample for hip and knee arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:2538–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee B, Hollenbeck-Pringle D, Goldman V, Biondi E, Alverson B. Are caregivers who respond to the child HCAHPS survey reflective of all hospitalized pediatric patients? Hosp Pediatr. 2019;9:162–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McFarland DC, Ornstein KA, Holcombe RF. Demographic factors and hospital size predict patient satisfaction variance—implications for hospital value-based purchasing. J Hosp Med. 2015;10:503–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rogo-Gupta LJ, Haunschild C, Altamirano J, Maldonado YA, Fassiotto M. Physician gender is associated with press Ganey patient satisfaction scores in outpatient gynecology. Women’s Health Issues. 2018;28:281–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garcia LC, Chung S, Liao L, Jonathan A, Magali F, Bonnie M, et al. Comparison of outpatient satisfaction survey scores for Asian physicians and non-Hispanic white physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e190027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen JG, Zou B, Shuster J. Relationship between patient satisfaction and physician characteristics. J Patient Exp. 2017;4:177–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Delbanco T. Hospital medicine: understanding and drawing on the patient’s perspective. DM. 2002;48:192–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitat Res Psych. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kash BA, McKahan M, Tomaszewski L, McMaughan D. The four Ps of patient experience: a new strategic framework informed by theory and practice. Health Mark Q. 2018;35:313–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rapport F, Hibbert P, Baysari M, Long JC, Seah R, Zheng WY, et al. What do patients really want? an in-depth examination of patient experience in four Australian hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shippee ND, Shippee TP, Mobley PD, Fernstrom KM, Britt HR. Effect of a whole-person model of care on patient experience in patients with complex chronic illness in late life. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35:104–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boylan MR, Slover JD, Kelly J, Hutzler LH, Bosco JA. Are HCAHPS scores higher for private vs double-occupancy inpatient rooms in total joint arthroplasty patients? J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:408–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Buckley LM. What about recovery. JAMA. 2019;321:1253–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Groene O. Patient centredness and quality improvement efforts in hospitals: rationale, measurement, implementation. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23:531–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, WDPWSupplement1 for What Do Patients Want? A Qualitative Analysis of Patient, Provider, and Administrative Perceptions and Expectations About Patients’ Hospital Stays by Sansrita Nepal, Angela Keniston, Kimberly A Indovina, Maria G Frank, Sarah A Stella, Itziar Quinzanos-Alonso, Lauren McBeth, Susan L Moore and Marisha Burden in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental Material, WDPWSupplement_2 for What Do Patients Want? A Qualitative Analysis of Patient, Provider, and Administrative Perceptions and Expectations About Patients’ Hospital Stays by Sansrita Nepal, Angela Keniston, Kimberly A Indovina, Maria G Frank, Sarah A Stella, Itziar Quinzanos-Alonso, Lauren McBeth, Susan L Moore and Marisha Burden in Journal of Patient Experience