Abstract

Background

FAIR (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) next-generation sequencing (NGS) data analysis relies on complex computational biology workflows and pipelines to guarantee reproducibility, portability, and scalability. Moreover, workflow languages, managers, and container technologies have helped address the problem of data analysis pipeline execution across multiple platforms in scalable ways.

Findings

Here, we present a project management framework for NGS data analysis called PM4NGS. This framework is composed of an automatic creation of a standard organizational structure of directories and files, bioinformatics tool management using Docker or Bioconda, and data analysis pipelines in CWL format. Pre-configured Jupyter notebooks with minimum Python code are included in PM4NGS to produce a project report and publication-ready figures. We present 3 pipelines for demonstration purposes including the analysis of RNA-Seq, ChIP-Seq, and ChIP-exo datasets.

Conclusions

PM4NGS is an open source framework that creates a standard organizational structure for NGS data analysis projects. PM4NGS is easy to install, configure, and use by non-bioinformaticians on personal computers and laptops. It permits execution of the NGS data analysis on Windows 10 with the Windows Subsystem for Linux feature activated. The framework aims to reduce the gap between researcher in experimental laboratories producing NGS data and workflows for data analysis. PM4NGS documentation can be accessed at https://pm4ngs.readthedocs.io/.

Keywords: NGS sequence analysis; NGS pipelines; open source frameworks; FAIR, RNA-Seq; ChIP-Seq; ChIP-exo

Findings

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) data analysis has advanced the design, implementation, and execution of many complex computational biology pipelines. For computational biologists, pipelines are multi-step methods [1] that should follow the FAIR (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) Data Principles [2] and guarantee reproducibility, portability, and scalability [3]. Workflow languages and managers, Docker containers, and scientific computational notebooks have been adopted by the scientific community with the intention to improve the reproducibility, portability, maintainability, and shareability of computational pipelines.

Common Workflow Language (CWL) [4] is an open standard workflow language used to describe and implement complex pipelines, which uses interchangeable blocks. The resulting product is portable and scalable; it can be executed across a variety of hardware environments as dissimilar as personal laptops or the cloud. In addition, some workflow managers have been developed to manage and execute CWL workflows (e.g., Toil [5] and CWL-Airflow [6]). These systems allow the control, monitoring, and checking of workflows deployed on stand-alone Linux machines or in cloud environments. Similarly, software installation tools specifically dedicated to bioinformatics, such as Bioconda [7], and Docker containers standardizations, such as Biocontainers [8], are available and result in easier bioinformatics tool installation and management. These languages, systems, and technologies solve the problem for data analysis pipeline execution across multiple platforms in a scalable way.

Moreover, applications providing user-friendly interfaces for NGS data analysis without any programming knowledge have been published; PhenoMeNal [9] and BioWardrobe [10] are popular examples. These applications offer a web-based graphical user interface encapsulating different NGS data analysis pipelines. They were implemented to analyze large NGS datasets taking advantage of cloud infrastructures or bare metal clusters. However, they are complex systems that require technical expertise for their use, deployment, and maintenance. Moreover, most of them do not work on personal laptops or workstations because they require a complete GNU/Linux environment with high-performance computing (HPC) or cloud infrastructure software components.

NGS data management through a standard organizational structure, automatic project report, and the production of publication-ready figures is still a complex process that involves the integration of multiple components and knowledge of the standards for publication. Experimental laboratories, however, demand the use of NGS data analysis tools to verify sample quality. These quality control tests are frequently executed by non-bioinformaticians but are limited to the use of tools such as FastQC [11] for pre-processing quality control. Nevertheless, for high-throughput data, pre-processing quality control is not sufficient to guarantee quality standards. Even with a positive pre-processing quality report, samples could include contamination or a high level of read duplication that could compromise further analysis. Time and resources can be saved if experimental researchers are able to align their samples and execute post-processing quality controls in parallel with their experiments.

Here, we present PM4NGS, a computational framework for NGS data analysis that integrates all required components, including automatic creation of a standard organizational structure of directories and files, bioinformatics tool installation using Docker or Bioconda, and data analysis pipelines in CWL format. Pre-configured Jupyter notebooks with minimum Python code are included in PM4NGS to produce a project report and publication-ready figures. The framework is designed in a modular way that allows non-bioinformaticians a quick check and quality control of produced samples on a personal laptop. The authors would like to highlight that PM4NGS was designed as a fully interactive tool for data analysis on personal laptops or workstations. It can also be used as an educational tool to train new bioinformaticians on how to organize an NGS data analysis project showing a detailed view of the pipeline components.

Methods

Next-generation sequencing data analysis workflows

PM4NGS currently includes 3 NGS data analysis workflows: differential gene expression and gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis from RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) data, differential binding analysis from chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-Seq) data, and DNA motif binding detection from ChIP-exo data. These workflows are in demand by NGS data analysis researchers, but PM4NGS also can easily be modified to process other NGS technologies and data types, such as ATAC-Seq or END-Seq data.

The workflows included in PM4NGS are based on the ENCODE Data Coordinating Center Uniform Processing Pipelines [12].

Differential gene expression and GO enrichment from RNA-Seq

RNA-Seq has become a standard technique to measure RNA expression levels. It is frequently used in basic and clinical research [13]. Differential expression (DE) analysis is one of the most used applications for RNA-Seq and allows the comparison of RNA expression levels between multiple conditions [14]. Benchmark studies have compared DE analysis tools [15, 16]. Currently, the most common tools used for DE analysis are DESeq [14] and EdgeR [17]. DE analysis identifies gene expression–level alterations between conditions that can later be integrated with GO [18] annotations to identify key biological processes.

Our DE and GO enrichment pipeline comprises 5 steps, presented in Supplementary Table S1. The first step involves downloading samples from the NCBI SRA database [19], if necessary, or executing the pre-processing quality control tools on local samples. Subsequently, sample trimming, alignment, and quantification processes are executed. Once all samples are processed, groups of differentially expressed genes are identified per condition, using DESeq and EdgeR. Over- and under-expressed genes are reported by each program, and the intersection of their results is computed. Finally, once differentially expressed genes are identified, a GO enrichment analysis is executed to provide key biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components for identified genes. The pipeline can be accessed via GitHub repository [20].

Differential binding analysis from ChIP-Seq

ChIP-Seq is a method to study genomic regions enriched in a specific DNA-binding protein in a massively parallel DNA sequencing experiment. It has broad applications for studying different epigenetic marks processed through histone modifications or transcription factor (TF) binding events [21]. Our differential binding analysis pipeline from ChIP-Seq experiments is applicable to any protein used as an immuno-precipitable target. The workflow comprises 5 steps, as presented in Supplementary Table S2. The first step, sample download and quality control, is for downloading samples from the NCBI SRA database [19], if necessary, or for executing the pre-processing quality control tools on all samples. Sample trimming and alignment are executed next. Post-processing quality control on ChIP-Seq samples is executed using Phantompeakqualtools [22], as recommended by the ENCODE pipelines [23]. Then, a peak-calling step is performed using MACS2 [24], and peak annotation is executed with Homer [25]. Peak reproducibility is explored with IDR [26]. Finally, a differential binding analysis is completed with DiffBind [27]. The pipeline can be accessed via GitHub repository [28].

DNA motif binding detection from ChIP-exo data

ChIP-exo was developed by Rhee and Pugh [29] to improve the resolution of ChIP-Seq experiments. A phage exonuclease step is added to digest the 5′ end of the TF-unbound DNA after ChIP. ChIP-exo reduces the statistically enriched high-occupancy binding regions detected with ChIP-Seq to single-base accuracy [29]. The method has been widely adopted to study 1-base resolution of DNA protein bound regions, although the tools developed to analyze ChIP-Seq data do not take advantage of the ChIP-exo resolution. The pipeline presented is based on MACE [30], which was developed to take advantage of the characteristics of the ChIP-exo data that produce binding peaks with high sensitivity and specificity.

The 5-step workflow is presented in Supplementary Table S3. The first step, sample download and quality control, is for downloading samples from the NCBI SRA database [19], if necessary, or for executing the pre-processing quality control tools on all samples. After that, sample trimming and alignment are executed. Post-processing quality control on the ChIP-exo samples is performed using Phantompeakqualtools [22], as recommended by the ENCODE pipelines [23]. After that, peak calling is performed, using MACE [30]. Finally, DNA motif annotation is performed with the MEME Suite [31]. The pipeline can be accessed via GitHub repository [32].

The PM4NGS computational framework

A key factor in any computational biology experiment is organization and effective management of the data [33]. A standard project organizational structure is mandatory to properly handle the interaction of several components such as bioinformatics tools, genome annotations, databases, input data files, output data files, figures, and scientific computational notebooks. PM4NGS automatically generates a standard organizational structure that allows a researcher external to the project, after a quick view of the directories and files, to gain an understanding of the project structure and be able to easily find any relevant data file, input, or output.

Our framework is based on a popular, free Python tool called Cookiecutter [34]. This tool creates projects from previously defined templates. It has been used to generate projects as dissimilar as pre-defined websites or project structures for data science [35]. Cookiecutter requires a Python installation for its execution. A simple command can be executed on Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL), available from Windows 10 or direct use on Mac OS and Linux. In addition, the framework uses Jupyter Notebooks for data and workflow management. Jupyter is a free, open source, interactive web application that permits the distribution of life code in the form of computational notebooks. These computational notebooks are being used in data science, making data analysis shareable and reproducible [36, 37].

Fig. 1 is a schematic description of the PM4NGS project with input requirements, main components, and outputs created for each pipeline. The Project Creation step is performed by Cookiecutter with pre-defined project templates that are based on the data to be analyzed. PM4NGS uses as input a sample sheet in TSV format (see description in the documentation [38]), which describes the samples' location, conditions, and replicates. The 4 Project Components are described in greater detail in the section below.

Figure 1:

PM4NGS schematic structure. DGE = Digital Gene Expression; DBE = Differential Binding Event; CWL = Common Workflow Language.

Standard project organizational structure

Our project organizational structure is inspired by an article published by Noble [33]. We adapted his directory and file system structure to be compatible with the PM4NGS approach, which is executed as including a dedicated folder for computational notebooks and CWL workflows.

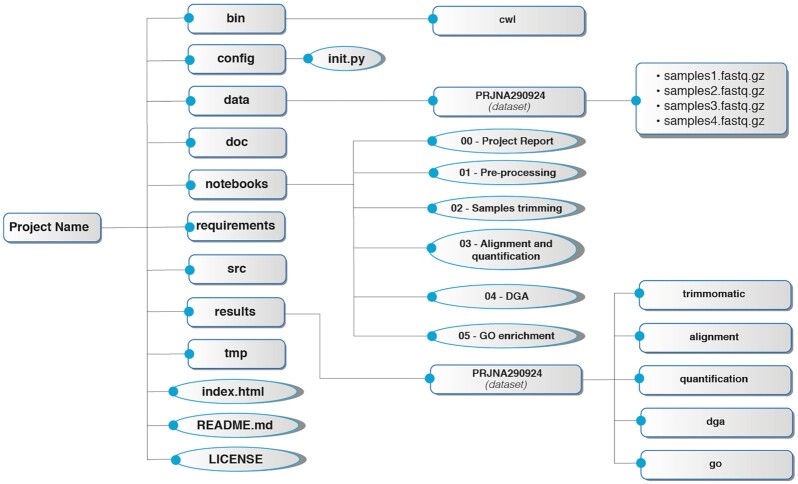

Fig. 2 shows the organizational structure created for a project. As an illustrative example, we describe the structure created for a differential gene expression and GO enrichment pipeline. First, a top-level directory is created with the project name. This directory is self-contained, which means that the transfer of the entire directory to another computational environment will ensure that all Jupyter Notebooks and CWL workflows will be executable elsewhere. See Box 1 for a full description of each folder inside the organizational structure.

Figure 2:

Organizational structure for an RNA-Seq–based project.

Box 1:

bin/cwl: the CWL workflows.

config: includes a file named "init.py," which defines all configurational variables for the project.

data: includes all data used as input for the project, as well as a directory for the dataset to be processed that contains all compressed FASTQ files.

doc: used to store all documentation written for the project.

notebooks: includes all Jupyter Notebooks used to analyze the data. The notebooks are numerated to show the order in which they should be executed, with the exception of the notebook "00–Project Report," which should be executed once all results are created.

requirements: includes extra requirements for the project, such as custom Python packages or Conda envs created during the analysis.

src: includes any custom source code created for the project.

results: this folder follows the same organizational structure that "data" does. It contains the "dataset" directory with all results from the workflow.

tmp: temporary folders used for CWL or Docker.

index.html: HTML file that will redirect to the 00–Project Report saved in HTML format for visualization in a browser (see [39]).

README.md: text file to add description about the project.

LICENSE: text file with a license description for project distribution.

Jupyter Notebook for data and workflow management

PM4NGS uses Jupyter Notebooks for data and workflow management. The notebooks are designed with minimum Python code, making them simple to understand and execute. For a standard analysis, notebooks can be executed without any modification. It is important to highlight that Jupyter Notebook was selected as the user interface in this project because it allows more advanced users to extend the analysis with customized workflows.

In addition, the entire workflow can be distributed in multiple notebooks, making it easy to understand and re-execute, if necessary. Furthermore, making the workflow interactive allows a visualization and check of the intermediate results, saving time and resources in case errors are detected.

All workflows include a notebook named "00–Project Report." This notebook should be executed after each step is finished. It will automatically create tables and figures that users can use to validate the data analysis process. This notebook also creates its own version in HTML format that can be used to share the results with collaborators or supervisors (see examples for an RNA-Seq project [39]).

Bioconda/Docker for bioinformatics tool management and execution

Software version management is also a key aspect of any computational experiment to obtain reproducible results. Computational technologies, such as Docker or Conda, have been developed to guarantee simple software version management for a non-expert user to implement computational environments straightforwardly.

Bioconda is a channel for the Conda package manager specialized on bioinformatics software. It contains >7,000 bioinformatics packages. Biocontainers is a project closely related to Bioconda, and it provides access to Bioconda packages through standardized containers. Both Bioconda and Bicontainers are community-driven projects that provide the infrastructure and basic guidelines to create, manage, and distribute bioinformatics packages.

PM4NGS adopted Docker (Biocontainers) or Conda (Bioconda) for software management and execution. Users can decide between them at the time of project creation, depending on their needs or infrastructure. The framework also can be used without these technologies, but tool availability and version should be ensured by the user.

If Conda is selected, a Conda directory, named "conda," will automatically be created inside the directory "bin" by cwltool and runtime execution. This environment can be recreated automatically if the project is moved to another computational environment. If Docker is selected, all Docker images required by the workflow will be pulled automatically by cwltool as required by the workflow to the local computer.

CWL tools and workflow specifications

The tools and workflows included in this framework are published in a separate Git repository [40]. This repository comprises 2 main directories. The first directory, named "tools," includes all computational tools used by the workflows in CWL format. The second folder, named "workflows," includes all workflows.

Each CWL tool includes 2 YAML files with suffixes "bioconda.yml" and "docker.yml." As indicated by its name, the bioconda.yml file stores the software requirements for executing the CWL tool using Conda (Bioconda). The files specify the package names and versions. The CWL runner will create a Conda environment and install the package, if it does not exist, at runtime.

The docker.yml file defines the Biocontainers Docker image to be used. This image will be pulled by the CWL runner at runtime. The bioconda.yml and docker.yml files defined for each computational tool can be used in any computational environment to recreate the same scenario in which the project was executed.

PM4NGS uses the Biocontainers Registry [41] through its Python interface named bioconda2biocontainer [42] to update the CWL docker images defined in the docker.yml file during project creation. The Bioconda package name and version defined in the bioconda.yml file is passed as an argument to the update_cwl_docker_from_tool_name method in bioconda2biocontainer, returning the latest Docker image available for the tool. PM4NGS, after cloning the CWL repository, parses the Bioconda package names and versions from the bioconda.yml files and updates all defined Docker images to its latest tags, modifying all docker.yml files.

The workflows are developed in a modular way, as defined by Cohen-Boulakia et al. [43], which means that the workflow steps are packed in sub-workflows that can be replaced if required. For instance, the workflow for the alignment and quality control of ChIP-Seq data includes a sub-workflow for sample alignment that uses BWA [44] and SAMtools [45], producing as output a sorted BAM file with an index. This sub-workflow could be replaced by a similar workflow using a different aligner without modifying the main workflow. For more detail on workflow steps, tools, and outputs, refer to Supplementary Tables S1–S3.

Each data analysis project created with PM4NGS will include a cloned version of the CWL repository. The workflow directory will be in the "bin" folder, as shown in Fig. 2. This guarantees that each project is self-consistent and will allow a user to keep updating the tools and workflows without affecting closed or active projects.

PM4NGS uses cwltool as CWL runner and the option "–parallel" to execute workflow steps in parallel. Multithreading tools uses the CWL variable "coresMin" to set the number of threads. Cwltool distributes the load using this variable and executes workflow steps until all available CPUs are in use. Tools that required a minimum RAM to be executed used the "minRAM" variable. The "maxRAM" variable is used to limit the amount of RAM that cwltool assigns to a step running the tool. These 2 variables are also used to determine the number of parallel steps to be executed.

Results and Discussion

PM4NGS was designed to be used on laptops or workstations. Execution is possible in any computational system that runs on 64-bit Linux, MAC OS, WSL, or a Linux virtual machine available on Windows.

The minimum computational resources required depends on the target organism of the samples. For analyzing human samples, a minimum of 32 GB of RAM is required owing to the size of the human genome. For analyzing bacterial samples, however, a minimum of 4 GB of RAM is enough.

The examples included in the supplementary materials were executed in a Dell Tower 5810 with 64 GB of RAM, 16-core Intel Xeon CPU E5–2640, and 1 TB of hard disk, using the Linux operating system OpenSUSE Leap 15.1 [46] and WSL with Ubuntu available from Windows 10 64-bit, 10 May 2019 update, downloaded from Microsoft [47].

Software requirements

The framework was developed to manage all software installation automatically. A minimum of Python 3.6 or later is required. In addition, if Conda will be used as a software manager, then a minimum version of Miniconda Python 3.7 64-bit should be installed. If, instead of Conda, Docker will be used, then the Docker Server should be installed. A more detailed description can be found in the project documentation [48].

For use in the WSL, any Linux distribution in the Microsoft Store can be used. We tested Ubuntu 20.04 and OpenSUSE Leap 15.1. Once the Linux distribution is available, the guidelines to follow are the same as those for the native Linux.

Input data

All implemented workflows require a sample sheet file during project creation. The file is copied to the "data/<DATASET>/" folder with name "sample_table.csv." Note that the variable "DATASET" is chosen during project creation, and it is the name used to identify the dataset to be analyzed. For example, if data in the NCBI SRA database will be analyzed, we recommend using the BioProject ID as the dataset name. This file should include ≥4 columns, and names are case sensitive: sample_name, file, condition, and replicate. See Box 2 for more description and example. PM4NGS uses the dataset encapsulation to allow multiple datasets using the same workflow version and notebooks.

Box 2:

Columns:

sample_name: Sample names, which can be different from the sample file name.

file: This is the absolute path or URL to the raw fastq file. For paired-end data the files should be separated using the Unix pipe | as in, e.g., SRR4053795_1.fastq.gz|SRR4053795_2.fastq.gz. HTTP and FTP URLs are also allowed and PM4NGS will download the data to the folder "data/<dataset_name>/" during project creation. This column should remain empty if the data are in the NCBI SRA database; PM4NGS will add a cell to the "01–Pre-processing QC" notebook to download the data using fastq-dump.

condition: Conditions to group the samples. Use only alphanumeric characters.

For RNA-Seq projects, the differential gene expression that compares these conditions will be generated. If there are multiple conditions, all comparisons will be generated. There must be ≥2 conditions.

For ChIP-Seq projects, differential binding events will be detected when comparing these conditions. If there are multiple conditions, all comparisons will be generated. There must be ≥2 conditions.

For ChIP-exo projects, the samples of the same condition will be grouped for the peak calling with MACE.

replicate: Replicate number for samples. If not replicated, this column is set to 1 for all samples.

See examples in the documentation [38].

If the project is analyzing data from the NCBI SRA database, the 01-Pre-processing QC Jupyter notebook will download the raw files, using fastq-dump to read the SRA accessions from the column "sample_name" in the sample_table.csv file. The raw files downloaded will be placed in the data/<DATASET>/ folder. If the samples are being provided by the users, however, the absolute path or URL needs to be defined in the sample sheet; PM4NGS will copy or download the samples to the data/<DATASET>/ folder. The naming convention defined in Box 2 should be followed.

Reference genome and annotations

All workflows require a reference genome and its annotations. The locations of these directories are defined during project creation but can be changed, in case of need, in the project configuration file config/init.py.

Depending on the NGS technology that needs to be analyzed, a short-read aligner is used. For RNA-Seq, the STAR [49] aligner is used. For ChIP-Seq and ChIP-exo, the BWA [44] aligner is used. The project documentation includes a detailed description of how to create the genome indexes for each aligner used by PM4NGS.

Supporting data

We analyzed 3 public BioProjects for demonstration purposes to show the functionality of the 3 workflows presented in this article (see Table 1). The links in Table 1 give access to the project report, in HTML format, automatically generated by PM4NGS.

Table 1:

BioProjects analyzed with the workflows

A detailed description of the procedure for downloading, installing, and configuring PM4NGS is available in the documentation [48]. The steps for analyzing each BioProject in Table 1 are described with execution time, results and figures, and troubleshooting and expected results.

Comparison with other frameworks

Workflow managers for NGS data analysis are publicly available. The open source solutions are Nextflow [52], CWL-Airflow [6], Arvados [53], REANA [54], and, more recently, SnakePipes [55]. With the exception of SnakePipes, all open source platforms require multiple steps to get a local version installed and configured. These steps demand high expertise in system administration and limit their use for non-bioinformaticians. Nextflow, SnakePipes, CWL-Airflow, and REANA only execute the workflows and do not offer user-friendly interfaces for managing the analysis data. Arvados has a limited local client "Arvados-in-a-box" that should be used for workflow development and is not intended for production use. It is focused on executing pipelines on Kubernetes [56], Minikube [57], and GKE [58]. BioWardrobe [10] is no longer supported as stated on the GitHub repository [59].

Commercial platforms, such as DNAnexus [60], DNAstar [61], Seven Bridges [62], and SciDAP [63], also provide web and desktop tools for NGS data analysis. They are designed to target HPC systems or cloud infrastructures and are not designed for use on personal laptops or workstations. In addition, platforms such as DNAnexus, Seven Bridges, and SciDAP constrain clients to use their computational infrastructure.

PM4NGS presents simple solutions to many of these problems. It is free; it is easy to install and use; it includes Jupyter Notebooks as a user interface; it allows the use of Docker or Conda; projects are self-contained through an organizational standard structure; and it automatically creates project reports and publication-ready figures.

Limitations

PM4NGS is currently limited to being executed on a single computer. Although it can execute multiple workflows in parallel, it does not include an implemented interface to submit jobs to HPC clusters or batch submissions to a cloud infrastructure. In addition, the number of available data analysis workflows is limited to 3, but this will be increased in the future.

The framework guarantees the repeatability, replicability, and shareability of the data analysis, following the definitions of Cohen-Boulakia et al. [43]. "Repeatability" means that, if the same analysis is executed multiple times, the results will be the same; "replicability" means that, if the same analysis is executed in different computational environments, the results will be the same; and "shareability" means that sharing a packaged data analysis with all its input data and conditions should guarantee repeatability and replicability. This framework does not, however, present a final solution for reproducibility and reuse because it does not include independent workflows to verify conclusions. In the case of differential gene expression analysis, 2 DGA tools, DESeq [14] and EdgeR [17], are used to corroborate the results with the aim of introducing a minimum level of reproducibility in the analysis.

Future improvements

We are working on implementing standard interfaces that allow users to submit workflows as batch submissions to private HPC clusters or to the different publicly available cloud providers. Users with technical expertise, however, can modify the current notebooks to submit jobs to their computational infrastructure. Furthermore, new pipelines are being implemented and tested for inclusion. Nevertheless, it is useful to highlight that existent workflows can be modified for analyzing other NGS technologies. These are important features, and we think that this framework could help researchers in experimental laboratories by providing a user-friendly tool for sample quality control and quick analysis.

Conclusion

PM4NGS is an open source framework that creates a standard organizational structure for NGS data analysis projects. It is easy to install and configure and is designed to be used by non-bioinformaticians on their personal computers or laptops. It permits execution of NGS data analysis on Windows 10 with the Windows Subsystem for Linux feature activated. Conda/Bioconda or Docker are used for bioinformatics tool management, allowing the framework to keep tool versions fixed for workflow reproducibility.

The users interact with Jupyter Notebooks with minimum Python code to process the data. The workflows are modular, which allows intermediate results to be inspected at any time. Project reports and publication-ready figures are also automatically created.

The 3 NGS data analysis workflows currently included in PM4NGS are based on the ENCODE Data Processing Pipelines.

Finally, we highlight that this framework aims to reduce the gap between researcher in experimental laboratories producing NGS data and the workflows for the data analysis. The complexity of working with multiple directories, data files, and programs on the Linux command line interface is completely managed by PM4NGS, allowing a researcher to focus on interpreting results.

Availability of Supporting Source Code and Requirements

Project name: PM4NGS

Project home page: https://pm4ngs.readthedocs.io/

Project repository: https://github.com/ncbi/pm4ngs

Pipeline repositories:

Operating system(s): Linux, MacOS, and Windows 10 (WSL)

Programming language: CWL, Python, BASH

Other requirements:

Conda/Bioconda or Docker

Jupyter Notebook

Poppler (https://poppler.freedesktop.org/)

CWL workflow:

Source: https://github.com/ncbi/cwl-ngs-workflows-cbb/

Main workflows CWL viewer URLs:

Sample download and quality control workflow: https://w3id.org/cwl/view/git/bab73c25f2358d9d76ffff13eeb39a5ece38a795/workflows/sra/download_quality_control.cwl

RNA-Seq alignment workflow:

ChIP-Seq and ChIP-exo alignment workflow:

ChIP-Seq peak-calling workflow:

ChIP-exo peak-calling workflow:

ChIPexo meme motif workflow:

License: Public Domain.

BiotoolsID: biotools: pm4ngs

An archival copy of the PM4NGS github repository is also available via the GigaScience database, GigaDB [64].

Additional Files

Supplementary Table S1: Differential gene expression analysis from RNA-Seq data. Workflow steps, notebooks, and tools. CWL available at: https://github.com/ncbi/cwl-ngs-workflows-cbb/

Supplementary Table S2: Differential binding analysis from ChIP-Seq data. Workflow steps, notebooks, and tools. CWL available at: https://github.com/ncbi/cwl-ngs-workflows-cbb/

Supplementary Table S3: DNA motif identification from ChIP-exo data. Workflow steps, notebooks, and tools. CWL available at: https://github.com/ncbi/cwl-ngs-workflows-cbb/

Abbreviations

ATAC-Seq: assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing; BWA: Burrows-Wheeler Aligner; ChIP-Seq: chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing; CPU: central processing unit; CWL: Common Workflow Language; DE: differential expression; FAIR: Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability; GO: Gene Ontology; HPC: high-performance computing; MACE: Model-based Analysis of ChIP-exo; NCBI: National Center for Biotechnology Information; NGS: next-generation sequencing; OS: operating system; RAM: random access memory; RNA-Seq: RNA sequencing; SRA: Sequence Read Archive; TF: transcription factor; WSL: Windows Subsystem for Linux.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NIH, NLM, NCBI).

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the workflows and manuscript preparation. R.V.A. designed and implemented the framework. R.V.A. executed all examples. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Marco Capuccini, Ph.D. -- 5/15/2020 Reviewed

Marco Capuccini, Ph.D. -- 11/8/2020 Reviewed

Artem Barski -- 6/4/2020 Reviewed

Artem Barski -- 10/27/2020 Reviewed

Nathan C. Sheffield -- 6/5/2020 Reviewed

Contributor Information

Roberto Vera Alvarez, Computational Biology Branch, National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, 8900 Rockville Pike, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20894, USA.

Lorinc Pongor, Developmental Therapeutics Branch and Laboratory of Molecular Pharmacology, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, 8900 Rockville Pike, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20894, USA.

Leonardo Mariño-Ramírez, Division of Intramural Research, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, 8900 Rockville Pike, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20894, USA.

David Landsman, Computational Biology Branch, National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, 8900 Rockville Pike, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20894, USA.

References

- 1. Perkel JM. Workflow systems turn raw data into scientific knowledge. Nature. 2019;573(7772):149–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJ, et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data. 2016;3:160018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Casadevall A, Fang FC. Reproducible science. Infect Immun. 2010;78(12):4972–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peter A, Michael R. C, Nebojša T, et al. Common Workflow Language, v1.0, . 2016, https://www.encodeproject.org/pipelines/. Accessed on December 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vivian J, Rao AA, Nothaft FA, et al. Toil enables reproducible, open source, big biomedical data analyses. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35(4):314–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kotliar M, Kartashov AV, Barski A. CWL-Airflow: a lightweight pipeline manager supporting Common Workflow Language. Gigascience. 2019;8(7), doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giz084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gruning B, Dale R, Sjodin A, et al. Bioconda: sustainable and comprehensive software distribution for the life sciences. Nat Methods. 2018;15(7):475–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. da Veiga Leprevost F, Gruning BA, Alves Aflitos S, et al. BioContainers: an open-source and community-driven framework for software standardization. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(16):2580–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peters K, Bradbury J, Bergmann S, et al. PhenoMeNal: processing and analysis of metabolomics data in the cloud. Gigascience. 2019;8(2), doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giy149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kartashov AV, Barski A. BioWardrobe: an integrated platform for analysis of epigenomics and transcriptomics data. Genome Biol. 2015;16:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Simon A. FastQC. 2012. http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/. Accessed on December 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Data Processing Pipelines. https://www.encodeproject.org/pipelines/. Accessed December 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, et al. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5(7):621–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11(10):R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Soneson C, Delorenzi M. A comparison of methods for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rapaport F, Khanin R, Liang Y, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of differential gene expression analysis methods for RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2013;14(9):R95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Smyth GK. Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(10):4288–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kodama Y, Shumway M, Leinonen R, International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration . The Sequence Read Archive: explosive growth of sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D54–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.PM4NGS RNA-seq repository https://github.com/ncbi/pm4ngs-rnaseq. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Steinhauser S, Kurzawa N, Eils R, et al. A comprehensive comparison of tools for differential ChIP-seq analysis. Brief Bioinform. 2016;17(6):953–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kharchenko PV, Tolstorukov MY, Park PJ. Design and analysis of ChIP-seq experiments for DNA-binding proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(12):1351–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Landt SG, Marinov GK, Kundaje A, et al. ChIP-seq guidelines and practices of the ENCODE and modENCODE consortia. Genome Res. 2012;22(9):1813–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 2008;9(9):R137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010;38(4):576–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li Q, Brown JB, Huang H, et al. Measuring reproducibility of high-throughput experiments. Ann Appl Stat. 2011;5(3):1752–79. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ross-Innes CS, Stark R, Teschendorff AE, et al. Differential oestrogen receptor binding is associated with clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nature. 2012;481(7381):389–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.PM4NGS ChIP-seq repository https://github.com/ncbi/pm4ngs-chipseq. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rhee HS, Pugh BF. Comprehensive genome-wide protein-DNA interactions detected at single-nucleotide resolution. Cell. 2011;147(6):1408–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang L, Chen J, Wang C, et al. MACE: model based analysis of ChIP-exo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(20):e156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, et al. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Web Server issue):W202–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.PM4NGS ChIP-exo repository. https://github.com/ncbi/pm4ngs-chipexo. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Noble WS. A quick guide to organizing computational biology projects. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5(7):e1000424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Greenfeld AR, Greenfeld DR. Cookiecutter: Better Project Templates. 2019. https://cookiecutter.readthedocs.io. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cookiecutter Data Science. 2019. https://drivendata.github.io/cookiecutter-data-science/. Accessed December 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gruning BA, Rasche E, Rebolledo-Jaramillo B, et al. Jupyter and Galaxy: easing entry barriers into complex data analyses for biomedical researchers. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(5):e1005425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Perkel JM. Why Jupyter is data scientists' computational notebook of choice. Nature. 2018;563(7729):145–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.PM4NGS sample sheet. https://pm4ngs.readthedocs.io/en/latest/pipelines/sampleSheet.html. [Google Scholar]

- 39.RNA-seq SRA paired data. https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/pm4ngs/examples/rnaseq-sra-paired/. [Google Scholar]

- 40.CWL NGS workflows CBB. https://github.com/ncbi/cwl-ngs-workflows-cbb. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bai J, Bandla C, Guo J, et al. BioContainers Registry: searching for bioinformatics tools, packages and containers. bioRxiv 2020, doi: 10.1101/2020.07.21.187609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vera Alvarez R, Perez-Riverol Y. bioconda2biocontainer. 2020. https://pypi.org/project/bioconda2biocontainer/. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cohen-Boulakia S, Belhajjame K, Collin O, et al. Scientific workflows for computational reproducibility in the life sciences: status, challenges and opportunities. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2017;75:284–98. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.OpenSUSE. https://www.opensuse.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Windows 10 update. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/software-download/windows10ISO. [Google Scholar]

- 48.PM4NGS documentation. https://pm4ngs.readthedocs.io/. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(1):15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.ChIP-seq hmgn1 data https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/pm4ngs/examples/chipseq-hmgn1/. [Google Scholar]

- 51.ChIP-exo data https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/pm4ngs/examples/chipexo-single/. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Di Tommaso P, Chatzou M, Floden EW, et al. Nextflow enables reproducible computational workflows. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35(4):316–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arvados website. https://arvados.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 54.reana: Reproducible research data analysis platform. http://reanahub.io/. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bhardwaj V, Heyne S, Sikora K, et al. snakePipes: facilitating flexible, scalable and integrative epigenomic analysis. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(2):4757–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kubernetes. https://kubernetes.io/. [Google Scholar]

- 57.minikube. https://minikube.sigs.k8s.io/docs/. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Google Kubernetes Engine. https://cloud.google.com/kubernetes-engine. [Google Scholar]

- 59.biowardrobe repository. https://github.com/Barski-lab/biowardrobe. [Google Scholar]

- 60.DNAnexus. www.dnanexus.com. [Google Scholar]

- 61.DNASTAR. www.dnastar.com. [Google Scholar]

- 62.SevenBridges. https://www.sevenbridges.com/. [Google Scholar]

- 63.SciDAP: Scientific Data Analysis Platform. https://scidap.com/. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Vera-Alvarez R, Pongor L, Mariño-Ramírez L, et al. Supporting data for “PM4NGS, a project management framework for next-generation sequencing data analysis”. GigaScience Database. 2020. 10.5524/100833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Vera-Alvarez R, Pongor L, Mariño-Ramírez L, et al. Supporting data for “PM4NGS, a project management framework for next-generation sequencing data analysis”. GigaScience Database. 2020. 10.5524/100833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Marco Capuccini, Ph.D. -- 5/15/2020 Reviewed

Marco Capuccini, Ph.D. -- 11/8/2020 Reviewed

Artem Barski -- 6/4/2020 Reviewed

Artem Barski -- 10/27/2020 Reviewed

Nathan C. Sheffield -- 6/5/2020 Reviewed