Key Points

Question

What are the learning constructs in dermoscopic image interpretation that represent an appropriate foundational proficiency for US dermatology resident physicians?

Findings

In this 2-phase modified Delphi survey of 26 pigmented lesion and dermoscopy experts, consensus was achieved identifying 32 diagnoses, 116 associated dermoscopic features, and 378 representative teaching images.

Meaning

A consensus was achieved among dermoscopy experts identifying the dermoscopic diagnoses, features, and images reflective of an appropriate foundational proficiency in dermoscopic image interpretation for dermatology residents; this list of validated objectives provides a consensus-based foundation of key learning points in dermoscopy to help residents achieve clinical proficiency.

Abstract

Importance

Dermoscopy education in US dermatology residency programs varies widely, and there is currently no existing expert consensus identifying what is most important for resident physicians to know.

Objectives

To identify consensus-based learning constructs representing an appropriate foundational proficiency in dermoscopic image interpretation for dermatology resident physicians, including dermoscopic diagnoses, associated features, and representative teaching images. Defining these foundational proficiency learning constructs will facilitate further skill development in dermoscopic image interpretation to help residents achieve clinical proficiency.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A 2-phase modified Delphi surveying technique was used to identify resident learning constructs in 3 sequential sets of surveys—diagnoses, features, and images. Expert panelists were recruited through an email distributed to the 32 members of the Pigmented Lesion Subcommittee of the Melanoma Prevention Working Group. Twenty-six (81%) opted to participate. Surveys were distributed using RedCAP software.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Consensus on diagnoses, associated dermoscopic features, and representative teaching images reflective of a foundational proficiency in dermoscopic image interpretation for US dermatology resident physicians.

Results

Twenty-six pigmented lesion and dermoscopy specialists completed 8 rounds of surveys, with 100% (26/26) response rate in all rounds. A final list of 32 diagnoses and 116 associated dermoscopic features was generated. Three hundred seventy-eight representative teaching images reached consensus with panelists.

Conclusions and Relevance

Consensus achieved in this modified Delphi process identified common dermoscopic diagnoses, associated features, and representative teaching images reflective of a foundational proficiency in dermoscopic image interpretation for dermatology residency training. This list of validated objectives provides a consensus-based foundation of key learning points in dermoscopy to help resident physicians achieve clinical proficiency in dermoscopic image interpretation.

This survery study examines consensus-based learning constructs that represent an appropriate foundational proficiency in dermoscopic image interpretation for dermatology resident physicians.

Introduction

Numerous studies have shown that the use of dermoscopy by experienced clinicians significantly improves in vivo diagnostic accuracy, increases confidence in clinical diagnoses, and decreases unnecessary biopsies.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 Dermoscopy use facilitates the detection of earlier-stage melanomas compared with visual inspection alone.6 Dermoscopy also has extensive applications beyond the diagnosis of pigmented lesions including use in keratinocyte carcinomas, infectious and inflammatory lesions, and disorders of the hair and nails.8

Although the use of dermoscopy among board-certified dermatologists has increased greatly in recent years, dermoscopy training in US residency programs has not universally increased at the same pace.10,11 In a 2017 survey, just 35% (43/122) of US dermatology resident physicians reported receiving dermoscopy training in their residency program, and 91% desired more dermoscopy training.12 A 2017 survey of dermatology resident physicians from 16 programs reported an average of 2 hours per year of dedicated dermoscopy lectures, and approximately half of resident physicians in 2013 and 2017 surveys noted dissatisfaction with level of dermoscopy training received.13,14 Inadequate training in dermoscopy has important implications because the diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy is strongly correlated with the amount of training received.1,15

Dedicated time working with a pigmented lesion specialist has been reported as one of the most effective means of learning dermoscopy.13 However, not all resident physicians have the opportunity to work with specialists during their training.13,14 Many instead turn to outside resources to learn dermoscopy, most commonly using textbooks or conference-based courses.12,14 Although these outside resources offer a substantial volume of information, most do not specify key resident physician learning constructs, may be overwhelming during independent study, and offer limited assistance for challenging cases encountered during clinical practice. To date, there are no resident physician–specific core competencies in dermoscopy, and a standardized outline of dermoscopy learning constructs for resident physicians could be a valuable tool to aid both formal and independent study.

This survey aimed to identify the dermoscopic diagnoses and features (with the term “features” encompassing dermoscopic structures and patterns) that pigmented lesion and dermoscopy experts think are most important for resident physicians to know on completion of their training. Experts also selected high-quality dermoscopic images that they felt were illustrative of each feature. This fundamental knowledge base in dermoscopy can provide a framework that can be built on throughout residency to achieve clinical excellence.

Methods

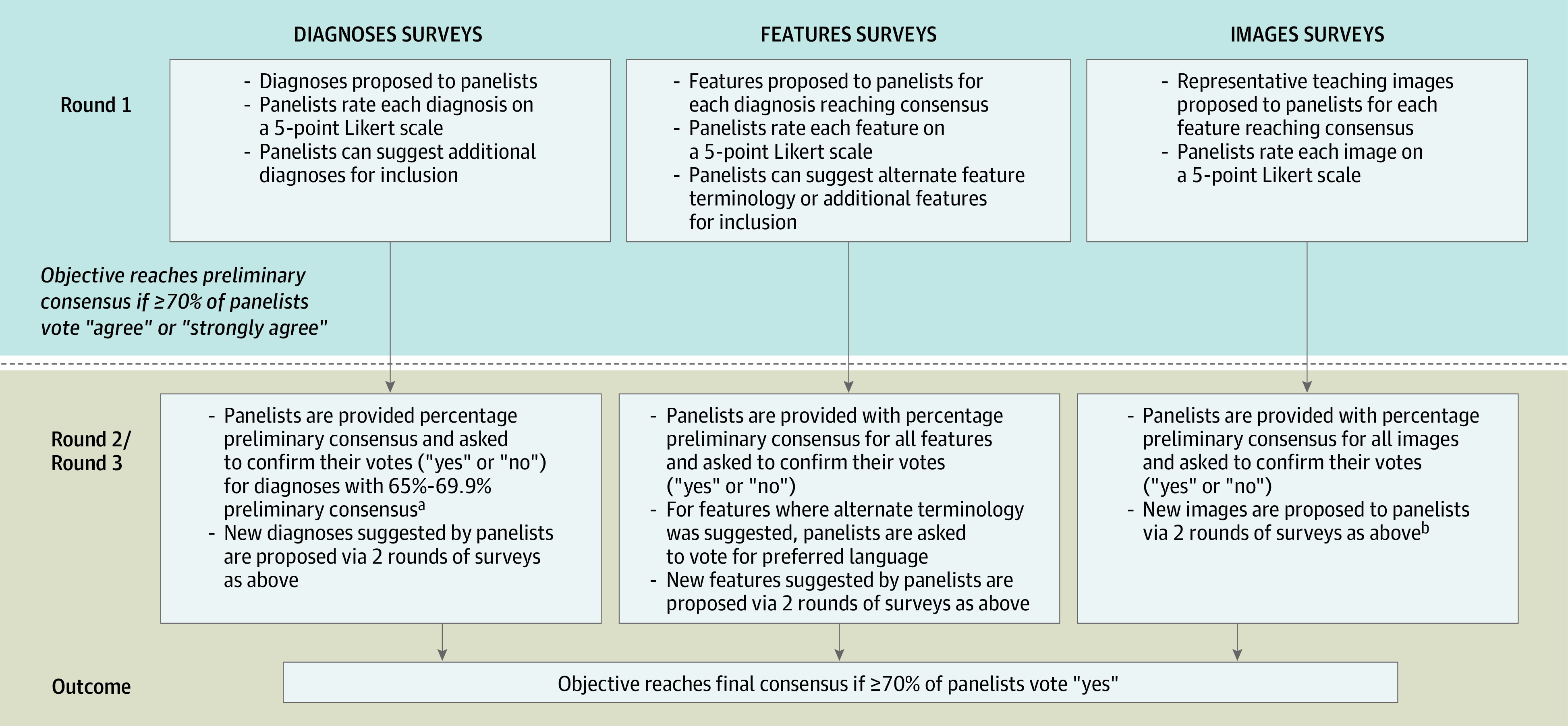

A 2-phase modified Delphi technique was used between May 29, 2019, and May 13, 2020, to identify expert consensus on 3 sets of objectives: (1) common dermatologic diagnoses with identifiable dermoscopic features, (2) associated dermoscopic features for each diagnosis that are either highly specific or commonly seen, and (3) representative teaching images for each feature (Figure 1). The list of proposed objectives was generated through review of recent publications, textbooks, conference materials, and expert discussion. Terminologies proposed reflected consensus language identified by the International Dermoscopy Society in 2016 as well as terms frequently encountered in the literature.16 Each objective was subject to 2 iterative rounds of surveying, with a threshold for consensus of greater than or equal to 70% agreement (indicated through panelist votes of “agree,” “strongly agree,” or “yes”). Panelists were instructed to vote positively only for the objectives that they believe comprised a minimum threshold for resident proficiency in dermoscopic image interpretation. Free-text comment boxes also allowed panelists to suggest additional objectives or modification of proposed terminology. A total of 8 survey instruments were designed and distributed using RedCAP, version 10.0.19 (Vanderbilt University), and a summary of results was distributed to panelists after each survey round. Specific survey methods for each objective are elaborated in Figure 1, and copies of each survey are available in the eMethods in the Supplement. This study was approved by the NYU Langone Health institutional review board (Study ID #i19-00203) on March 25, 2019.

Figure 1. Survey Methods.

aGiven the uniformity of positive responses from panelists for the initial list of diagnoses suggested in the diagnoses round 1 survey, diagnoses reaching preliminary consensus were accepted and not proposed in a second round. Diagnoses that were close but did not reach consensus (65%-69.9% of panelists voting “agree” or “strongly agree”) were surveyed back to panelists in a second round to ensure agreement on inclusion. There was greater diversity in panelists’ responses in the features and images surveys, and these objectives were therefore all surveyed to panelists in 2 sequential rounds.

bNew images were proposed to the expert panel for voting if: A, none of the offered images reached preliminary consensus; B, less than 50% of initially offered images reached preliminary consensus and panelists offered alternate dermoscopic images; or C, if multiple panelists had submitted comments expressing dissatisfaction with the initial images offered.

Panel Recruitment

Pigmented lesion and dermoscopy experts were invited to participate via an email circulated to the Pigmented Lesion Subcommittee of the Melanoma Prevention Working Group, with participating individuals making up the Dermoscopy Education Working Group (The Melanoma Prevention Working Group is affiliated with the Southwest Oncology Group and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group–American College of Radiology Imaging Network). Experts in this group are members of multiple academic institutions; see author affiliations for complete list. Panelists provided consent to be contacted via email for survey distribution.

Results

Panelist Demographics

A total of 32 experts were invited to participate in the survey, and 26 (81%) participated in round 1. Of the 26 experts who completed the first round, 100% completed all subsequent rounds of the survey. Sixteen of 26 panelists (61%) reported using dermoscopy for longer than 11 years, and all panelists reported a minimum of 6 to 10 years of dermoscopy experience. Twenty-four of 26 panelists (92%) specialized in pigmented lesions, dermoscopy, and/or melanoma, and 8 of 26 (31%) were directors of a pigmented lesion clinic at an academic institution. Twenty-four of 26 panelists (92%) reported teaching dermoscopy to resident physicians using clinic-based or lecture-based formats. Additional panelist demographic information can be found in the eTable in the Supplement.

Survey Results

Three sets of objectives were surveyed: diagnoses, features, and images. In the diagnoses surveys, panelists voted on a total of 52 diagnoses, with 32 reaching final consensus in the categories of “nonmelanocytic” (15), “benign melanocytic” (6), “melanoma” (4), and “special sites/other” (7). In the features surveys, panelists voted on a total of 142 dermoscopic features, with 116 reaching final consensus. In the images surveys, panelists voted on a total of 442 illustrative teaching images, with 378 reaching final consensus. An average of 3.3 images reached consensus for each feature. All surveyed diagnoses and features are presented in Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3, and an example of results for dermoscopic images proposed to panelists in the images surveys is shown in Figure 2. Of note, Figure 2C gives an example of an image that was rejected by the panel as not sufficiently representative of the designated feature, in this case comma vessels. The full collection of all dermoscopic images reaching consensus with panelists has been made available online.17

Table 1. Dermoscopic Characteristics of Nonmelanocytic Lesions.

| Diagnosis or feature | Round 1: positive response, % | Round 2: positive response, % |

|---|---|---|

| Basal cell carcinoma | 96 | |

| Leaflike structures | 96 | 100 |

| Blue-gray ovoid nests | 100 | 100 |

| Multiple blue-gray dots and globules (buckshot scatter) | 88 | 96 |

| Spoke-wheellike structures/concentric structures | 92 | 100 |

| Ulceration/erosion | 88 | 96 |

| White shiny blotches and strands | 85 | 89 |

| Arborizing blood vessels | 100 | 100 |

| Short fine telangiectasias (superficial BCC)a | 62 | 88 |

| Rosette signb | 42 | 12 |

| Shiny white to red structureless and milky pink areas (glasslike translucency)a,b | 27 | 12 |

| Actinic keratosis | 85 | |

| Rosette sign | 77 | 89 |

| Surface scale | 73 | 85 |

| Strawberry pattern (pink-red pseudonetwork +/– fine, wavy vessels [straight or coiled] surrounding hair follicles +/– white circles with central yellow clod [targetoid hair follicles])c | 85 | 96 |

| Pigmented actinic keratosis | 85 | |

| Gray dots | 81 | 89 |

| Annular-granular pattern (gray dots around follicular openings) | 71 | 92 |

| Rosette sign | 85 | 92 |

| Surface scalea | 89 | 100 |

| Rhomboidal structuresb | 62 | 35 |

| White circles with central yellow clod (targetoid hair folliclesb | 69 | 58 |

| Gray-brown pseudonetworkb | 58 | 27 |

| Moth-eaten bordera,b | 31 | 20 |

| Patent folliclesa,b | 38 | 40 |

| Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ) | 89 | |

| Surface scale | 81 | 100 |

| Peripheral brown/gray dots arranged linearly (pigmented SCCIS) | 77 | 92 |

| Glomerular (coiled)/dotted blood vesselsd | 96 | 100 |

| Brown circles (pigmented SCCIS)b | 54 | 27 |

| Keratoacanthoma | 85 | |

| Central keratin mass | 92 | 100 |

| Hairpin (looped) or serpentine (linear-irregular) blood vessels, usually at the periphery, with white-yellow haloe | 96 | 100 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 96 | |

| Yellow keratin mass/scale-crust | 85 | 100 |

| Ulceration/blood spots/hemorrhagef | 77 | 81 |

| White circles (“keratin pearls”) | 85 | 96 |

| Rosette sign | 81 | 92 |

| Glomerular (coiled) blood vessels | 88 | 100 |

| Hairpin vessels, usually with whitish halo | 92 | 96 |

| Polymorphic blood vessel morphologya,b | 42 | 28 |

| Linear irregular (serpentine) blood vesselsa,b | 42 | 32 |

| Solar lentigo | 96 | |

| Moth-eaten (sharply demarcated) borders | 100 | 100 |

| Homogenous light brown pigmentation | 92 | 92 |

| Networklike structures | 77 | 85 |

| Fingerprintlike structures (parallel lines)g | 96 | 100 |

| Simple lentigo (lentigo simplex) 85% | ||

| Symmetric with uniform pigment network | 88 | 85 |

| Seborrheic keratosis | 96 | |

| Milialike cysts | 100 | 100 |

| Comedolike openings | 100 | 100 |

| Moth-eaten (sharply demarcated) borders | 85 | 100 |

| “Fissures and ridges”/gyri and sulci/cerebriform pattern | 96 | 100 |

| Fat-fingers | 92 | 100 |

| Fingerprintlike structures | 85 | 96 |

| Hairpin (looped) vessels, usually with whitish halo | 96 | 100 |

| Networklike structuresa | 62 | 27 |

| Lichen planuswlike keratosis/benign lichenoid keratosis 89% | ||

| Coarse gray granularity | 92 | 96 |

| Peppering (evenly spaced gray dots) | 92 | 96 |

| Sharp, cut off borders (scalloped/moth-eaten)a | 73 | 84 |

| Pinpoint/dotted blood vesselsa,b | 31 | 16 |

| Pigment network remnanta,b | 46 | 32 |

| Hemangioma/angioma 96% | ||

| Red, blue-red, or maroon lacunae/lagoons with white septae | 100 | 100 |

| Blue-black coloring (when thrombosed) | 100 | 100 |

| Angiokeratoma | 96 | |

| Red/purple/black (“dark”) lacunae | 100 | 100 |

| Hemorrhagic crust | 88 | 85 |

| Whitish veila | 62 | 54 |

| Dermatofibroma | 96 | |

| Central scarlike white patch with delicate surrounding networklike structures | 100 | 100 |

| Ringlike globules | 81 | 89 |

| Central shiny white lines (crystalline structures) | 96 | 100 |

| Vascular structures (vascular blush) within scarlike white patcha,b | 50 | 52 |

| Clear cell acanthoma | 78 | |

| String of pearls (serpiginous) blood vessel pattern | 100 | 100 |

| Sebaceous hyperplasia 93% | ||

| Pale yellow lobules around a central follicular opening | 100 | 100 |

| Crown vessels | 100 | 100 |

| Poromaa,b | 35 |

Abbreviations: BCC, basal cell carcinoma; SCCIS, squamous cell carcinoma in situ.

Objective did not reach consensus.

Objective suggested by a panelist.

Panelists voted to use this language instead of “strawberry pattern (pink-red pseudonetwork + fine, wavy vessels [straight or coiled] surrounding hair follicles + white circles with central yellow clod [targetoid hair follicles]).”

Panelists voted to use this language instead of “glomerular (coiled) blood vessels.”

Panelists voted to use this language instead of “hairpin (looped) or serpentine (linear-irregular) blood vessels with white-yellow halo.”

Panelists voted to use this language instead of splitting into the 2 features “ulceration” and “blood spots/hemorrhage.”

Panelists voted equally between labeling this feature as “fingerprintlike structures” and “fingerprintlike structures (parallel lines). The latter was kept in order to be as inclusive as possible given equal outcomes in voting.

Table 2. Dermoscopic Characteristics of Melanocytic Lesions.

| Diagnosis or feature | Round 1: positive response, % | Round 2: positive response, % |

|---|---|---|

| Benign melanocytic lesions | ||

| Overview of benign nevi patterns | 96 | |

| Diffuse reticular network | 100 | 100 |

| Patchy reticular network | 100 | 100 |

| Peripheral reticular network with central hypopigmentation | 100 | 100 |

| Peripheral reticular network with central hyperpigmentation | 100 | 100 |

| Peripheral reticular network with central globules | 100 | 100 |

| Homogenous (tan, brown, blue, or pink) | 96 | 100 |

| Central network with evenly distributed peripheral globules | 100 | 100 |

| Globular pattern | 100 | 100 |

| Two-component pattern | 92 | 100 |

| Symmetric multicomponent pattern | 85 | 89 |

| Congenital melanocytic nevi | 96 | |

| Cobblestone pattern/globular pattern | 100 | 100 |

| Reticular network | 100 | 100 |

| Diffuse background pigmentation | 92 | 96 |

| Hypertrichosis | 81 | 92 |

| Perifollicular hyper/hypopigmentation | 88 | 100 |

| Target network/targetlike structures (globules or vessels within holes of network)a,b | 65 | 35 |

| Pigment dropouta,b | 31 | 16 |

| Keratin retentiona,b | 27 | 12 |

| Intradermal nevi | 96 | |

| Comma-shaped (curved) blood vessels | 100 | 100 |

| Homogenous (structureless) brown/tan pigmentationb,c | 85 | 96 |

| Blue nevi | 96 | |

| Homogenous blue pigmentation | 100 | 100 |

| Spitz nevi | 93 | |

| Vascular pattern (pink homogenous with dotted vessels) | 96 | 100 |

| Starburst pattern (with tiered globules/streaks) (radial streaming) | 100 | 100 |

| Negative network (reticular depigmentation) | 88 | 100 |

| White shiny lines (crystalline structures) | 81 | 96 |

| Globular patterna | 77 | 69 |

| Reticular patterna | 58 | 23 |

| Atypical patterna | 58 | 23 |

| Homogenous (pigmented) patterna | 46 | 19 |

| Recurrent (persistent) nevi | 93 | |

| Pigment within the scar, not extending beyond | 92 | 100 |

| Uniformity of pigment networka,b | 38 | 20 |

| Halo nevusa,b | 58 | |

| Melanoma | ||

| Overview of melanoma characteristics | 96 | |

| Atypical pigment network | 100 | 100 |

| Blue structures (blue-white veil, blue-gray structures)d | 96 | 100 |

| White shiny lines (crystalline structures) | 100 | 100 |

| Negative network | 100 | 100 |

| Irregular dots/globules | 100 | 100 |

| Irregular streaks (radial streaming, pseudopods) | 100 | 100 |

| Regression structures (white scarlike area and/or peppering)e | 96 | 100 |

| Peripheral brown structureless area | 88 | 96 |

| Angulated lines (extrafacial) | 85 | 100 |

| Atypical vascular pattern, polymorphous vessels (2+ types of blood vessels, eg, linear irregular and dotted vessels)f | 100 | 100 |

| Atypical blotch | 96 | 100 |

| Multiple hyperpigmented areasa,b | 31 | 32 |

| Asymmetry of border abruptnessa,b | 35 | 28 |

| Acral lentiginous melanoma | 96 | |

| Parallel ridge pattern | 100 | 100 |

| Irregular diffuse pigmentationg | 96 | 100 |

| Multicomponent patterng | 88 | 100 |

| Atypical fibrillar pattern | 88 | 96 |

| Lentigo maligna melanoma (melanoma on chronically sun-damaged skin of head/neck) | 96 | |

| Annular-granular pattern (gray dots around follicular openings) | 100 | 100 |

| Asymmetric pigmentation around follicular openings | 100 | 100 |

| Rhomboidal structures (angulated lines)h | 96 | 100 |

| Circle within a circle (isobar)i | 85 | 92 |

| Dark blotches with or without obliterated hair follicles | 100 | 100 |

| Amelanotic/hypomelanotic melanomab | 88 | |

| Scarlike depigmentation | 73 | 89 |

| Milky red areas | 100 | 100 |

| White shiny lines (crystalline structures) | 100 | 100 |

| Atypical vascular pattern, polymorphous vessels (2+ types of blood vessels, eg, linear irregular and dotted vessels)j | 100 | 100 |

| Melanoma arising within a nevusa,b,j | 85 | 35 |

| Nevoid melanomaa,b | 65 | |

| Desmoplastic melanomaa,b | 62 | |

Objective did not reach consensus.

Objective suggested by a panelist.

Panelists voted to use this language instead of “small foci of homogenous (structureless) brown/tan pigmentation.”

Panelists voted to use this language instead of making “blue-gray structures” and “blue-white veil” separate structures.

Panelists voted to use this language instead of “regression structures (white scarlike area with peppering).”

Panelists voted to use this language instead of “atypical vascular pattern, polymorphous vessels (2+ types of blood vessels).”

Panelists voted to keep these as separate features instead of combining the two into “chaotic/asymmetric pattern (eg, irregular diffuse pigmentation, multicomponent pattern).”

Panelists voted to use this language instead of “rhomboidal structures.”

Panelists voted to use this language instead of “target pattern (circle within a circle) (isobar).”

Panelists voted to use this language instead of “atypical vascular pattern, polymorphous vessels (2+ types of blood vessels).”

Table 3. Special Sites/Other.

| Diagnosis or feature | Round 1: positive response, % | Round 2: positive response, % |

|---|---|---|

| Dermoscopic features of the face | 96 | |

| Pseudonetwork pattern | 92 | 96 |

| Benign patterns of acral nevi | 96 | |

| Parallel furrow pattern (with pattern variations including single line, double line, single dotted line, double dotted line)a | 100 | 100 |

| Latticelike pattern | 100 | 100 |

| Fibrillar pattern (soles only) | 100 | 100 |

| Homogenous pattern | 88 | 100 |

| Peas in a pod pattern (parallel furrow + globules on ridges) (congenital nevi) | 96 | 100 |

| Dermoscopy of nailsb | ||

| Nevus of the nail | 96 | |

| Homogenous brown background coloration | 92 | 100 |

| Uniform band thickness, color, and spacing with parallel band configuration | 96 | 100 |

| Lentigo of the nail (melanotic macule of the nail) | 96 | |

| Multiple thin homogenous gray lines (or single gray band) +/– gray backgroundc | 88 | 100 |

| Melanoma of the nail | 96 | |

| Triangular shape of pigment band (band diameter wider at proximal end) | 96 | 100 |

| Pigmentation of periungual skin (micro-Hutchinson’s sign) | 100 | 100 |

| Brown to black dots/globules associated with longitudinal lines | 92 | 96 |

| Longitudinal brown/black lines with irregular spacing, width, coloration, or parallelism | 100 | 100 |

| Band width >3mm or >2/3 of nail plate widthb | 69 | 88 |

| Blurring of band bordersb,d | 50 | 52 |

| Subungual hemorrhage | 96 | |

| Well-circumscribed red-black dots or blotches | 100 | 100 |

| Distal streaks of red-brown coloration (“filamentous” distal end) | 96 | 100 |

| Homogenous red/purple/black coloration without melanin granules | 88 | 96 |

| Onychomatricomab,d | 46 | |

| Onychopapillomab,d | 46 | |

| Other | ||

| Scabiesb | 85 | |

| Delta-wing jet with contrail sign (small dark brown triangular structure located at the end of whitish structureless curved/wavy lines) | 100 | 100 |

| Trichoscopy (dermoscopy of the hair and scalp)b,d | 65 | 46 |

| Dermoscopy of mucosal surfacesb,d | 65 | 39 |

| Lichen planusb,d | 65 | 35 |

| Psoriasisb,d | 54 | |

| Vasculitisb,d | 46 | |

| Merkel cell carcinomab,d | 58 | |

Panelists voted to use this language instead of “parallel furrow pattern.”

Objective suggested by a panelist.

Panelists voted to use this language instead of “multiple thin homogenous gray lines +/– gray background.”

Objective did not reach consensus.

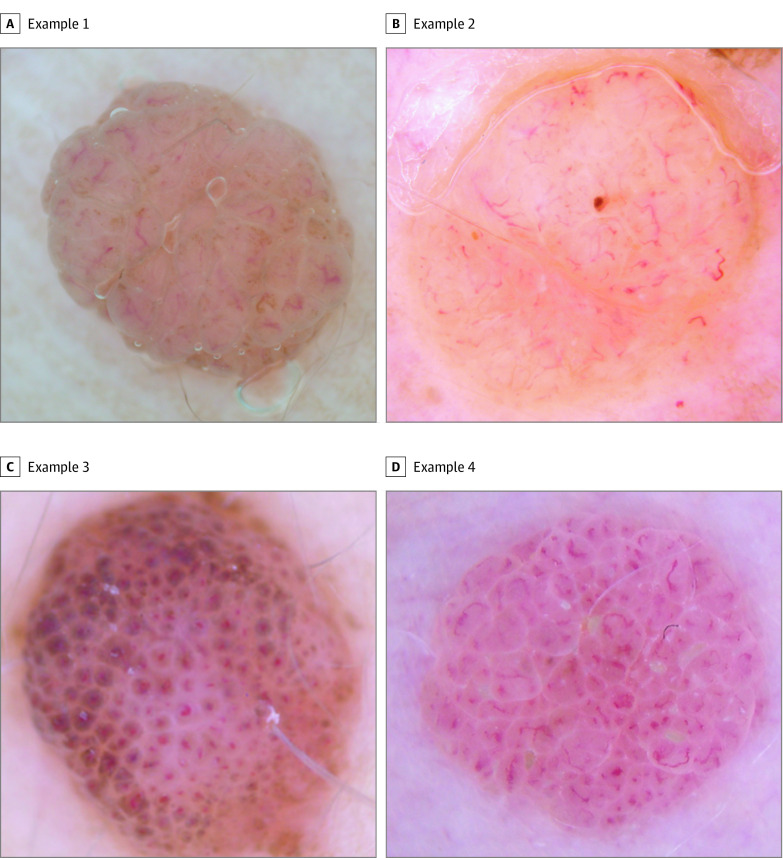

Figure 2. Dermoscopic Images Proposed to Panelists for the Feature “Comma-Shaped (Curved) Blood Vessels” for the Diagnosis “Intradermal Nevi”.

A, Round 1: 100% positive votes; round 2: 100% positive votes. B, Round 1: 92.3% positive votes; round 2: 100% positive votes. C, Round 1: 61.5% positive votes; round 2: 30.8% positive votes. D, Round 1: 92.3% positive votes; round 2: 100% positive votes. Most or all of panelists agreed that images A, B, and D were representative of the feature. For image C, 61.5% of panelists voted “agree” or “strongly agree” in the images round 1 survey. After being provided with this preliminary percent consensus, only 8 of 26 panelists (30.8%) voted in agreement of the image in the images round 2 survey. Thus, images A, B, and D reached consensus as representative teaching images, and image C did not reach consensus.

Narrative Comments

Experts were able to provide free-text feedback for each objective and at the completion of each survey, allowing for suggestions for new objectives or modification of existing objectives. Objective-specific feedback resulted in the inclusion of 6 additional diagnoses, 5 additional features, and 9 new dermoscopic images (Tables 1-3). Although proposed terminology for diagnoses and features was based on consensus terminology,16 in some cases the panelists felt that existing terminology required modification for the purpose of clarity. Panelists reached consensus on such modifications for 15 dermoscopic features, with rationale for the changes indicated by superscripts in Tables 1-3.

A specific instance of survey changes made in response to panelists’ comments occurred for the diagnosis “Melanoma arising within a nevus.” Although this diagnosis originally reached consensus in the diagnoses surveys, several panelists wrote in comments during the features surveys that they no longer agreed with its inclusion (eg, “I’m not sure that melanoma arising in a nevus needs to be separately taught, since any features concerning for melanoma would trump benign features”). The diagnosis was subsequently reproposed to panelists and failed to reach consensus, with just 9 of 26 experts (35%) voting for its inclusion.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to identify key learning constructs for resident physician–level foundational dermoscopy proficiency by conducting a modified Delphi survey. Our panel of 26 pigmented lesion and dermoscopy experts identified common dermoscopic diagnoses, associated features, and representative teaching images that they agreed all dermatology resident physicians should be expected to recognize on completion of residency. Panelists reached consensus on 32 diagnoses, 116 associated features, and 378 images.

In the diagnoses surveys, panelists most often agreed on the inclusion of diagnoses relating to cutaneous malignant abnormality and its precursors, such as actinic keratoses, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Consensus was also generally achieved for common benign lesions, such as melanocytic nevi and solar lentigines. Panelists were able to submit additional diagnoses for group consideration through free-text comments, and submissions that reached consensus included amelanotic melanoma, scabies, and 4 diagnoses in dermoscopic findings of nails.

Experts were less likely to reach consensus on uncommon malignant abnormalities or benign inflammatory lesions (eg, angiosarcoma, desmoplastic melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, psoriasis, or vasculitis). This is consistent with narrative feedback that, although dermoscopy has wide applications across a variety of malignant diseases, nonmalignant, infectious, and inflammatory disorders,8 some of these are outside of the scope of day-to-day practice, and resident physician–level proficiency should prioritize the recognition of malignant disease or features suggesting need for biopsy (eg, “As poroma and halo nevi are relatively uncommon, I feel less strongly about their inclusion”; “Given the broad applications of dermoscopy to multiple diagnoses, it will be important to limit the resident curriculum to entities where the greatest sensitivity and…specificity can be taught”). Importantly, panelists agreed that scabies was a diagnosis that all residents should be able to make on dermoscopic images. Panelists may have been more inclined to include this diagnosis due to its highly characteristic dermoscopic findings, which can help confirm diagnosis without need for additional testing.

Of note, the special sites “dermoscopy of hair (trichoscopy)” and “dermoscopy of mucosal surfaces” did not reach consensus, with 12 of 26 (46%) and 10 of 26 (39%) in final agreement, respectively. In write-in comments, panelists noted that, although they felt that these areas are “helpful to introduce trainees to,” they should not be included as a part of basic foundational learning. Lack of positive consensus may have also been reflective of the sample of panelists, who were primarily (24 of 26 [92%]) pigmented lesion specialists and may use the technique less frequently in these areas (eTable in the Supplement). Nevertheless, it is important to note that dermoscopy has substantial applications for use in disorders of the hair, scalp, and mucosal surfaces, and exposure to use of the technique in these areas can be a valuable component of resident education.8

The primary goal of dermoscopy education is the association of the visual appearance of a feature or constellation of features with a diagnosis. We found that dermoscopists may use varying terminologies to describe the same feature, so panelists were given the opportunity to suggest alternative language, which was then surveyed back to the group for consensus. Ultimately, the particular labels that residents use for dermoscopic features are of secondary importance for successful diagnostic use of the technique. Developing a vocabulary based on an agreed-upon language is important to facilitate communication and formalized learning.

Limitations

A potential limitation of the use of a web-based Delphi survey is that the multiple choice answer format may fail to adequately capture panelists’ opinions. To mitigate this, panelists were able to provide free-text feedback, and any suggestions for alternate wording or additional objectives were proposed to the full panel (as described). Comments and questions that arose during the survey were addressed in summaries sent out after each round. An additional limitation of the study is the small number of panelists invited to participate, most of whom practice in academic settings. This may have resulted in bias in the opinions expressed through the survey. We did include panelists from a broad geographic area in an attempt to collect a diverse range of viewpoints and mitigate such biases. Finally, competencies identified in this survey were developed specifically for United States dermatology residents, and translation to other educational cohorts may require specific attention.

Conclusions

Given the proven utility of dermoscopy in the detection of early-stage melanoma, improving resident education in dermoscopy should be a priority to best prepare the next generation of dermatologists. The inclusion of dermoscopy in the American Board of Dermatology's certification process (core and applied examinations) and the newly revised Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competencies for dermatology residency training, underscores the importance of quality resident physician education in dermoscopy. Dermoscopy education in US dermatology programs varies widely.10,11 Although there are numerous resources available for dermoscopy education, most are not specifically developed with resident education in mind. Many residents report a desire to learn more dermoscopy than is offered by their residency programs, and they rely on these outside resources to achieve competency in dermoscopy.12,13,14 The expert-validated set of dermoscopic diagnoses, features, and images included in this study has significant potential as a teaching curricula for dermatology resident education. Images from this study are now available online.17 We used a modified Delphi process to identify common dermoscopic diagnoses, associated features, and representative teaching images for basic resident physician proficiency in dermoscopy. This list of validated objectives provides a consensus-based foundation of key learning points in dermoscopy to help residents achieve clinical proficiency in the use of this valuable diagnostic tool. We hope that improved education during dermatology residency will translate into improved patient care during and after residency.

eTable. Respondent demographics (n=26)

eMethods. Survey data

References

- 1.Kittler H, Pehamberger H, Wolff K, Binder M. Diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3(3):159-165. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(02)00679-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carli P, De Giorgi V, Crocetti E, et al. Improvement of malignant/benign ratio in excised melanocytic lesions in the ‘dermoscopy era’: a retrospective study 1997-2001. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150(4):687-692. doi: 10.1111/j.0007-0963.2004.05860.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang SQ, Dusza SW, Scope A, Braun RP, Kopf AW, Marghoob AA. Differences in dermoscopic images from nonpolarized dermoscope and polarized dermoscope influence the diagnostic accuracy and confidence level: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34(10):1389-1395. doi: 10.1097/00042728-200810000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nehal KS, Oliveria SA, Marghoob AA, et al. Use of and beliefs about dermoscopy in the management of patients with pigmented lesions: a survey of dermatology residency programmes in the United States. Melanoma Res. 2002;12(6):601-605. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200212000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Rhee JI, Bergman W, Kukutsch NA. The impact of dermoscopy on the management of pigmented lesions in everyday clinical practice of general dermatologists: a prospective study. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(3):563-567. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09551.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolner ZJ, Yélamos O, Liopyris K, Rogers T, Marchetti MA, Marghoob AA. Enhancing skin cancer diagnosis with dermoscopy. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(4):417-437. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Chuchu N, et al. ; Cochrane Skin Cancer Diagnostic Test Accuracy Group . Dermoscopy, with and without visual inspection, for diagnosing melanoma in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD011902. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011902.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Micali G, Verzì AE, Lacarrubba F. Alternative uses of dermoscopy in daily clinical practice: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(6):1117-1132.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, Menzies SW. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(3):669-676. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08713.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terushkin V, Oliveria SA, Marghoob AA, Halpern AC. Use of and beliefs about total body photography and dermatoscopy among US dermatology training programs: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(5):794-803. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murzaku EC, Hayan S, Rao BK. Methods and rates of dermoscopy usage: a cross-sectional survey of US dermatologists stratified by years in practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):393-395. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel P, Khanna S, McLellan B, Krishnamurthy K. The need for improved dermoscopy training in residency: a survey of US dermatology residents and program directors. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7(2):17-22. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0702a03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu TP, Newlove T, Smith L, Vuong CH, Stein JA, Polsky D. The importance of dedicated dermoscopy training during residency: a survey of US dermatology chief residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(6):1000-1005. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen YA, Rill J, Seiverling EV. Analysis of dermoscopy teaching modalities in United States dermatology residency programs. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7(3):38-43. doi: 10.5826/dpc.070308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bafounta ML, Beauchet A, Aegerter P, Saiag P. Is dermoscopy (epiluminescence microscopy) useful for the diagnosis of melanoma? results of a meta-analysis using techniques adapted to the evaluation of diagnostic tests. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(10):1343-1350. doi: 10.1001/archderm.137.10.1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kittler H, Marghoob AA, Argenziano G, et al. Standardization of terminology in dermoscopy/dermatoscopy: results of the third consensus conference of the International Society of Dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(6):1093-1106. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dermoscopedia Academy Dermoscopedia. https://academy.dermoscopedia.org/Main_Page. Published 2020. Accessed September 1, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Respondent demographics (n=26)

eMethods. Survey data