Abstract

Background

Disability is an increasingly important health-related outcome to consider as more individuals are now aging with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and multimorbidity. The HIV Disability Questionnaire (HDQ) is a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM), developed to measure the presence, severity and episodic nature of disability among adults living with HIV. The 69-item HDQ includes six domains: physical, cognitive, mental-emotional symptoms and impairments, uncertainty and worrying about the future, difficulties with day-to-day activities, and challenges to social inclusion. Our aim was to develop a short-form version of the HIV Disability Questionnaire (SF-HDQ) to facilitate use in clinical and community-based practice among adults living with HIV.

Methods

We used Rasch analysis to inform item reduction using an existing dataset of adults living with HIV in Canada (n = 941) and Ireland (n = 96) who completed the HDQ (n = 1037). We evaluated overall model fit with Cronbach’s alpha and Person Separation Indices (PSIs) (≥ 0.70 acceptable). Individual items were evaluated for item threshold ordering, fit residuals, differential item functioning (DIF) and unidimensionality. For item threshold ordering, we examined item characteristic curves and threshold maps merging response options of items with disordered thresholds to obtain order. Items with fit residuals > 2.5 or less than − 2.5 and statistically significant after Bonferroni-adjustment were considered for removal. For DIF, we considered removing items with response patterns that varied according to country, age group (≥ 50 years versus < 50 years), and gender. Subscales were considered unidimensional if ≤ 5% of t-tests comparing possible patterns in residuals were significant.

Results

We removed 34 items, resulting in a 35-item SF-HDQ with domain structure: physical (10 items); cognitive (3 items); mental-emotional (5 items); uncertainty (5 items); difficulties with day-to-day activities (5 items) and challenges to social inclusion (7 items). Overall models’ fit: Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.78 (cognitive) to 0.85 (physical and mental-emotional) and PSIs from 0.69 (day-to-day activities) to 0.79 (physical and mental-emotional). Three items were rescored to achieve ordered thresholds. All domains demonstrated unidimensionality. Three items with DIF were retained because of their clinical importance.

Conclusion

The 35-item SF-HDQ offers a brief, comprehensive disability PROM for use in clinical and community-based practice with adults living with HIV.

Keywords: Disability evaluation, Outcome measures, Patient reported outcomes, Item analysis, Item response theory

Background

In countries with access to antiretroviral therapy, HIV is now experienced as a chronic illness with more adults aging with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) [1–4]. Chronic conditions are more prevalent among people aging with HIV than the general population [5, 6] such as cardiovascular disease [7], bone and joint disorders [8, 9], diabetes [10], frailty [11], neurocognitive disorders [12, 13], and some forms of cancer [14]. This multimorbidity can increase the complexities of aging with HIV [15–18], collectively referred to as disability [17, 19]. Adults aging with HIV can face additional challenges of ageism, stigma, mental health issues, financial insecurity, access to long-term care housing, and lack of social support, adding further to the complexity of disability over the aging life course [20–23]. Hence, the emerging needs of adults aging with HIV require personalized and preventative approaches to multi-morbidity and disability.

The Episodic Disability Framework is a conceptual framework developed from the perspective of adults living with HIV that characterizes the multidimensional and episodic nature of disability [17, 19]. Dimensions of disability in the Framework include physical, cognitive, mental and emotional symptoms and impairments, difficulties carrying out day-to-day activities, challenges to social inclusion, and uncertainty about future health [17, 19]. This Framework, considered novel for its inclusion of uncertainty a key dimension of aging with chronic illness, conceptually underpinned the development of a new HIV-disability patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) [24].

Using categories in the Episodic Disability Framework, members of our team established the HIV Disability Questionnaire (HDQ), a PROM developed to describe the presence, severity and episodic nature of disability experienced living with HIV [24]. As the only known HIV-specific disability PROM derived and validated from the perspectives of adults living with HIV [24], the HDQ addresses gaps in previously existing health status measures by capturing uncertainty about the future and challenges to social inclusion [25]. The HDQ possesses sensibility, reliability and validity for use among community dwelling adults living with HIV in Canada, Ireland, the United States and United Kingdom, suggesting its international applicability and scope [26–29]. While the HDQ has potential for clinical utility, concerns exist that it is too lengthy and not feasible for use in the busy clinic or community-based setting [30]. Our aim was to develop a Short-Form version of the HIV Disability Questionnaire (SF-HDQ) to facilitate use in clinical and community-based practice among adults living with HIV.

Methods

We conducted a secondary analysis using data from adults living with HIV in Canada (n = 941) and Ireland (n = 96) who completed the HDQ, and fitted the data to the Rasch model to develop the SF-HDQ [31].

HIV Disability Questionnaire The HDQ includes 69-items grouped into six domains: (1) physical symptoms and impairments (20 items), (2) cognitive symptoms and impairments (3 items), (3) mental-emotional symptoms and impairments (11 items), (4) uncertainty about future health (14 items), (5) difficulties with day-to-day activities (9 items), and (6) challenges to social inclusion (12 items) [25, 32]. The questionnaire describes a range of health challenges a person might experience so that clinicians may better understand and address the disability needs of people aging with HIV. The HDQ possesses a 5-point ordinal response scale that measures the presence and severity of disability ranging from “0 = not at all” to “4 = an extreme amount”, and a binary response scale that captures the episodic nature of disability (yes = 1 or no = 0). The HDQ is scored as a simple sum transformed out of 100 whereby higher scores (range 0–100) indicate a higher presence, severity and episodic nature of disability.

Rasch analysis

We conducted a Rasch analysis, a popular method for developing PROMs, assessing cross-cultural validity, and guiding item reduction [31, 33–36]. Our approach to the conduct and reporting of this Rasch analysis were informed by the work and guidelines for reporting studies using Rasch analysis, developed by Alan Tennant [31, 33, 34, 37, 38]. The Rasch model uses a logistic function to indicate the probability that an individual responds to a particular item (response option) and is dependent on both the individual ability and the difficulty (or severity) of the item [39]. Items representing the latent construct (disability) are hierarchically ordered along the continuum of difficulty. Fitting ordinal response data, such as items in the HDQ, to the Rasch model transforms the score into an interval scale. As the items are hierarchically ordered, Rasch analysis allows an individual’s location on the continuum to be precisely estimated using few items, making it an ideal approach for item reduction [33–36]. For the development of the SF-HDQ, we conducted a Rasch analysis using a rating scale model [40] focused on the severity scale (0–4 response options). Given the Rasch model assumes unidimensionality, and our assumption that each domain of disability measures a distinct construct of disability, we conducted our analysis on each domain separately.

For each HDQ domain, we conducted the following analytical steps iteratively to examine overall model and item fit:

Rasch model fit We evaluated model fit statistics including Cronbach’s alpha and Person Separation Indices (PSI) to determine the extent to which the domains and individual items fit the Rasch model. We considered ≥ 0.70 as acceptable [31, 41]. We assessed the Chi Square statistic (χ2) with Bonferroni adjusted significance levels (alpha value = 0.05/number of items in the original domain), but did not consider it a determinant of model fit given its sensitivity to large sample sizes, which can overestimate lack of model fit [42].

-

Item thresholds We identified items with disordered thresholds, which suggest respondents may not be able to differentiate between response options (or degrees of disability severity). In such instances, if clinically meaningful, we merged response options of items with disordered thresholds to obtain ordered thresholds. Reordered items that still did not achieve ordered thresholds were considered for deletion [41].

We also examined the difficulty hierarchy of items by examining item characteristics curves and threshold maps illustrating the spread of logit values of all items for each domain.

Item fit statistics We examined observed and expected values and considered items with absolute standardized fit residuals > 2.5 for deletion [43, 44].

Differential item functioning (DIF) We examined measurement invariance and considered removing items with response patterns that varied according to country (Canada versus Ireland), age group (≥ 50 years versus < 50 years), and gender [34]. Items with significant DIF and > 1.0 logit difference between groups were considered for deletion [34].

Unidimensionality For each domain, we conducted a principal components analysis (PCA) of the residuals to ensure there were no additional latent factors after the Rasch factor had been accounted for in the model. We identified two item sets from the PCA (positively and negatively correlated items with the residuals) to derive separate person estimates and then conducted independent t-tests to determine the number of cases that significantly differed (0.05 level). Strict unidimensionality was confirmed when ≤ 5% of independent t-tests comparing possible patterns in residuals were significant [31, 37, 45].

We used RUMM2030 for the analysis [46]. We used a combination of Rasch and clinical reasoning to inform our final decisions to remove or retain items. We removed items considered for deletion one at a time and re-evaluated model and item-level fit after each item removal in order to identify the ideal domain item composition. We did not remove any items from the cognitive domain as we considered three items as the minimum number to comprise a latent variable representing a domain of disability [47, 48]. Co-authors (KKO, MD, RH, EN, GW, AMD) met on three occasions to review the Rasch model results for each domain and discussed decisions for item deletion or retention. After three iterations of preliminary model results, two authors (KKO and AMD) met to review model and item fit characteristics for each domain and to determine final item retention (or deletion), maximizing model fit while ensuring clinical relevance and utility of the questionnaire. We defined ‘clinical importance’ of an item as an item that represents a key component of the SF-HDQ domain determined by clinical and research expertise of the team, and supported by research evidence. In areas where we retained an item due to clinical importance, we provide references from the literature in the discussion to support our decision.

Sample size Our analysis was based on the assumption that at least 10 observations per response option are needed for item threshold analysis [49] and at least 50 participants are needed to determine item fit with the Rasch model [50]. Hence our sample of 1037, was sufficient for the analysis.

SF-HDQ scoring

We created a user-friendly scoring algorithm for each domain to convert raw summed SF-HDQ scores to the equivalent Rasch-based person logit scores. Using methodology described by Perruccio et al. [51], we fit a cubic function to regress Rasch-based person logit scores on the raw summed SF-HDQ scores, which was then transformed to an interval scale range of 0–100. The resulting formula for each SF-HDQ domain can then be used to yield simple Rasch-based interval SF-HDQ domain scores (range: 0–100) with higher scores indicating greater disability.

Results

Sample characteristics

The majority of participants were men (811/1037; 78%), median age of 47 years, of which 41% (427/1307) were ≥ 50 years of age. Participants reported living with a median of three concurrent health conditions in addition to HIV; most common conditions included mental health (e.g. anxiety and depression), muscle pain and joint pain. Description of participant characteristics based on country are provided in Table 1. Further detail on the characteristics of these sample populations have been published elsewhere [26, 52].

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants by country

| Characteristic | Canada (n = 941) | Ireland (n = 96) |

|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number (%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 740 (79%) | 71 (74%) |

| Women | 159 (17%) | 23 (24%) |

| Transgender | 19 (2%) | 2 (2%) |

| Two-spirited | 15 (2%) | – |

| Missing | 8 (1%) | – |

| Median age in years (25–75th percentile) | 48 (39–54) | 41 (34–48) |

| 50 years or older | 405 (43%) | 22 (23%) |

| Median time since HIV diagnosis in years (25–75th percentile) | 13 (6–21) | 9 (4–14) |

| Taking antiretroviral therapy | 851 (90%) | 84 (88%) |

| Undetectable viral load (< 40 copies/mL)b | 572 (67%) | 41 (85%) |

| Employment status (full-time or part-time) | 350 (37%) | 52 (54%) |

| Median number of concurrent health conditions (25–75th percentile) | 3 (1–6) | 1 (0–3) |

| Living with ≥ 2 concurrent health conditions in addition to HIV | 518 (72%) | 39 (41%) |

| Common concurrent health conditionsa | ||

| Mental health condition | 392 (42%) | 18 (19%) |

| Muscle pain | 308 (33%) | 21 (22%) |

| Joint pain | 282 (30%) | 22 (23%) |

| Addiction | 248 (26%) | 9 (9%) |

| Neurocognitive decline | 209 (22%) | 11 (12%) |

| Hepatitis Cc | 95 (10%) | 21 (22%) |

| Self-rated health status ‘very good’ | 274 (29%) | 34 (35%) |

Number of participants: n = 1037; Not all characteristics add to the total n due to missing responses

aConcurrent health conditions experienced by ≥ 20% of respondents in either sample

bBased on number of participants who confirmed they were taking antiretroviral therapy; out of 851 (Canadian) and 48 (Irish) samples respectively. Among Canadian sample, 44 (5%) could not remember or did not know their viral load

cIrish sample recruited from an HIV-Hep-C co-infection clinic

Rasch models for SF-HDQ domains

Overall across all six domains, we removed 34 items, resulting in a 35-item SF-HDQ with domain structure: physical (20 items reduced to 10); cognitive (3 items; none removed); mental-emotional (11 items reduced to 5); uncertainty (14 items reduced to 5); difficulties with day-to-day activities (9 items reduced to 5) and challenges to social inclusion (12 items reduced to 7).

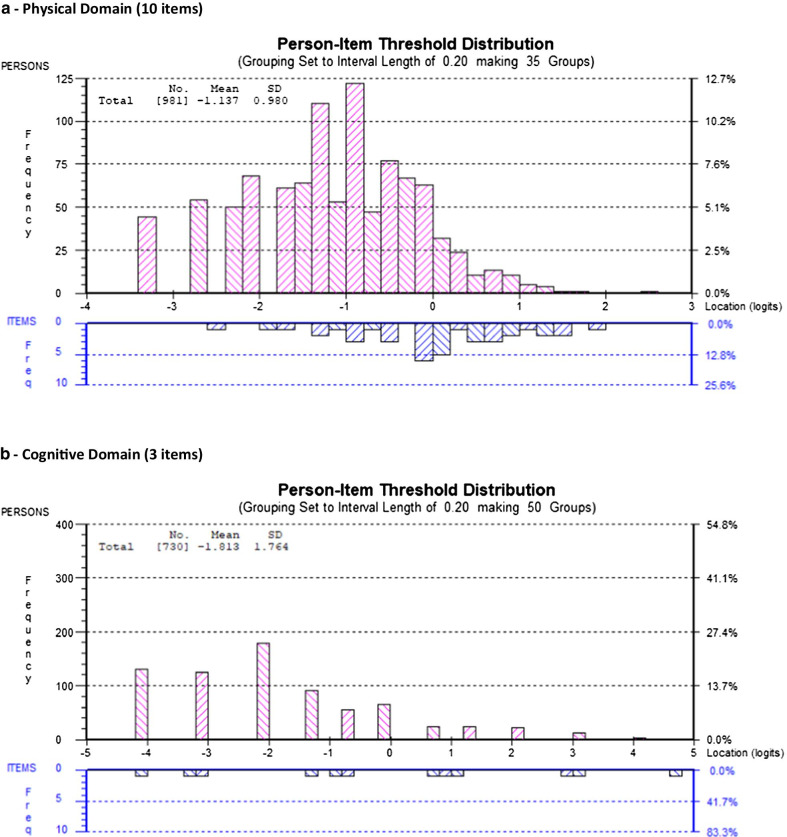

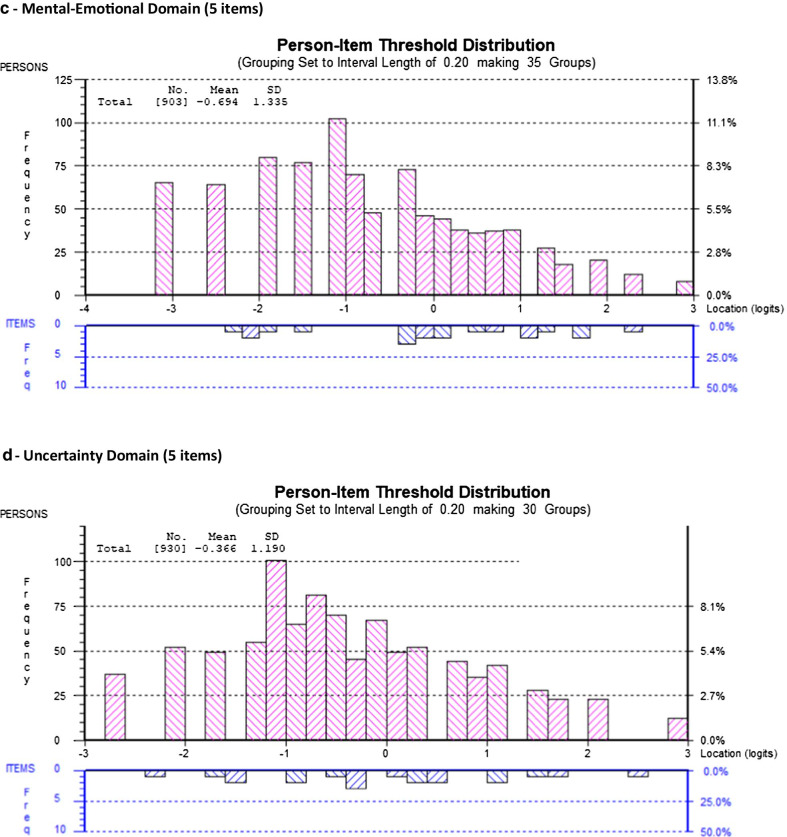

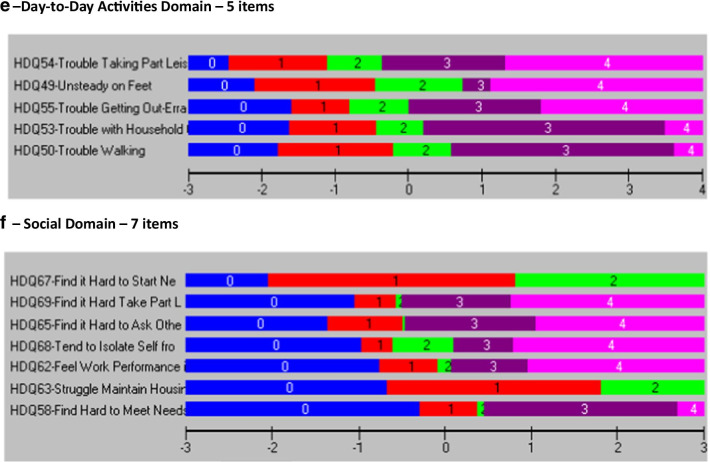

For all six models, Fig. 1 includes the person-item threshold distribution for each domain in the final models showing the distribution of item-levels (easiest to most difficult) for participants in the sample (Fig. 1a–f).

Fig. 1.

Person-item threshold distributions for final SF-HDQ domains

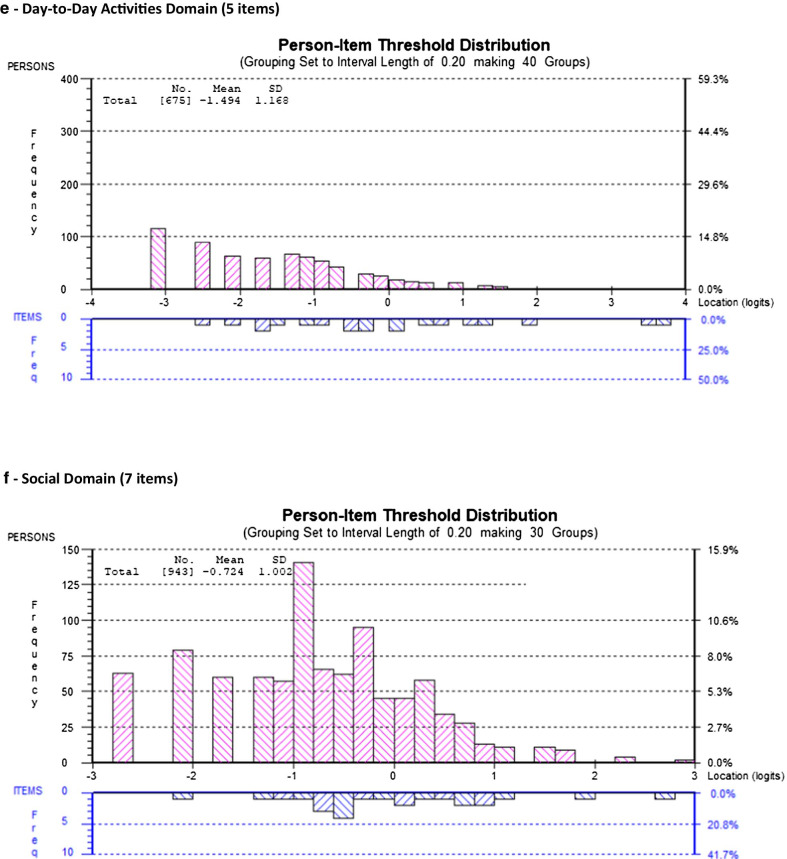

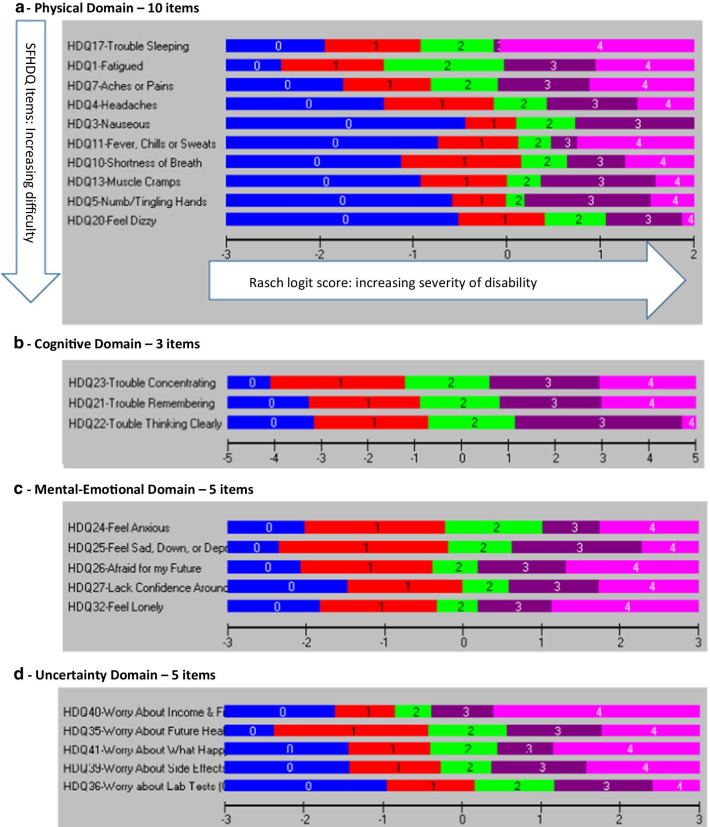

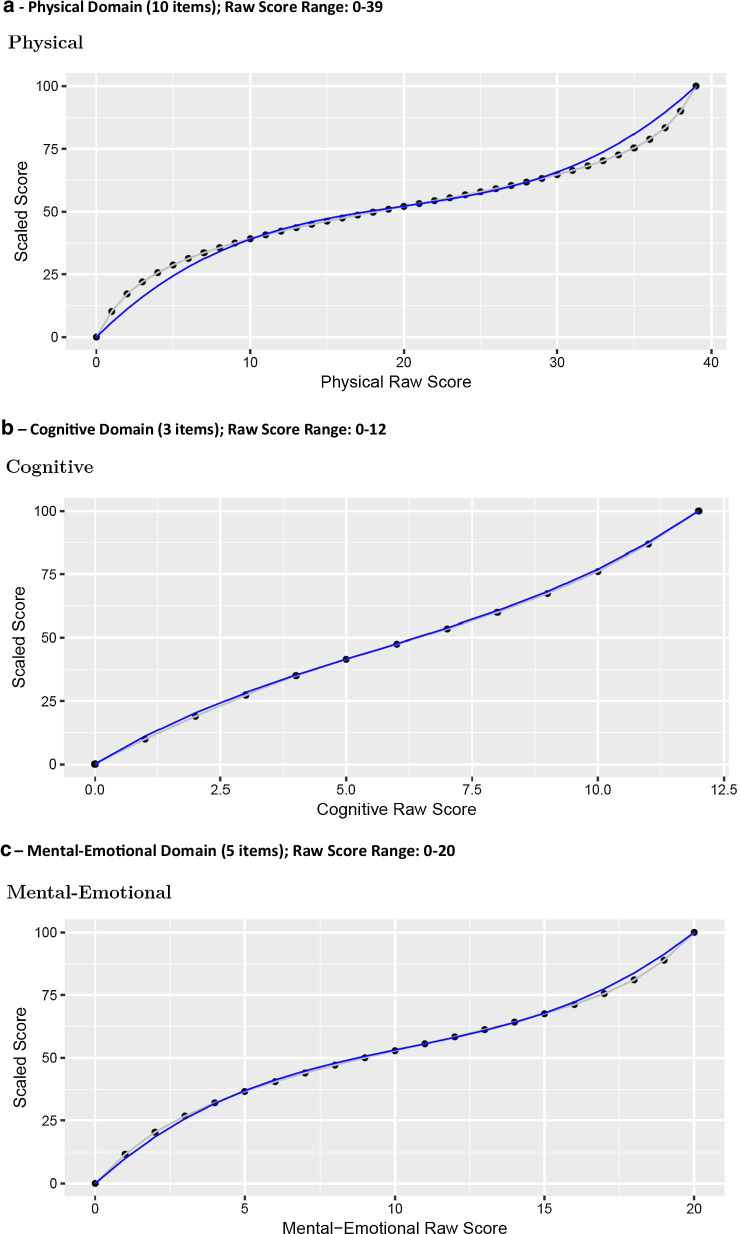

Figure 2 illustrates the item threshold map for each final SF-HDQ domain in order of increasing difficulty from top to bottom, and with severity levels increasing from left to right (Fig. 2a–f).

Fig. 2.

Item threshold map of the final model SF-HDQ domains in order of item difficulty. This figure illustrates the item threshold map for each final SF-HDQ domain in order of increasing difficulty from top to bottom, and with severity levels increasing from left to right (a–f). For example, in the physical domain 'trouble sleeping' is the item with least difficulty to 'feeling dizzy' which is the item with the most difficulty to score high levels of disability severity

Additional file 1 presents the model characteristics and fit statistics from the first to final iteration of the Rasch model for each domain outlining the step-wise process and decision-making to remove items. Additional file 2 includes the category probability curves for each item in the final SF-HDQ models. Additional file 3 provides an overview of the original HDQ items (69 items) and final proposed SF-HDQ items (35 items).

Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 provides an overview of model and item fit statistics for the resulting SF-HDQ items in each domain. Below we describe the Rasch model results for each domain.

Table 2.

Physical Domain (10 items) - Overview of final SF-HDQ item level and domain model fit statistics

| Item # | Final SF-HDQ items | Item level statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical domain | Location | SE | Residual | ChiSq χ2 | p value | |

| 1 | Fatigue | − 0.694 | 0.038 | − 0.276 | 13.544 | 0.140 |

| 3 | Nauseaa | 0.132 | 0.044 | − 0.748 | 18.549 | 0.029 |

| 4 | Headaches | 0.098 | 0.039 | 0.361 | 16.422 | 0.059 |

| 5 | Numbness or tingling in hands | 0.288 | 0.039 | 0.100 | 8.470 | 0.488 |

| 7 | Aches or pains | − 0.441 | 0.036 | − 1.399 | 21.204 | 0.012 |

| 10 | Shortness of breath | 0.240 | 0.041 | 0.061 | 15.153 | 0.087 |

| 11 | Fever, chills, or sweats | 0.162 | 0.039 | − 0.529 | 18.191 | 0.033 |

| 13 | Muscle cramps | 0.262 | 0.040 | − 2.120 | 13.636 | 0.136 |

| 17 | Trouble sleeping | − 0.761 | 0.034 | 2.141 | 14.346 | 0.111 |

| 20 | Feel dizzy | 0.714 | 0.045 | − 1.555 | 14.747 | 0.098 |

| Final model: physical domain—10 items (raw score range: 0–39) | ||||||

| Mean | − 1.137 | |||||

| Standard deviation | 0.980 | |||||

| Sample size | 981 | |||||

| Chi-square statistic (df) p value | 154.2609 (df: 90) p = 0.0003 | |||||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.84762 | |||||

| Person Separation Index | 0.79042 | |||||

| Unidimensionality t-test (% significant) | 0.41% | |||||

| Differential Item Functioning (DIF) | None | |||||

aHDQ3 rescored to 4 response categories (0–3)

Table 3.

Cognitive Domain (3 items) - Overview of final SF-HDQ item level and domain model fit statistics

| Item # | Final SF-HDQ items | Item level statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive domain | Location | SE | Residual | ChiSq χ 2 | p value | |

| 21 | Trouble remembering like appointments and when to take medication | − 0.072 | 0.058 | 2.764* | 20.271 | 0.005* |

| 22 | Trouble thinking clearly | 0.498 | 0.061 | − 1.078 | 34.33 | < 0.001a |

| 23 | Trouble concentrating | − 0.427 | 0.060 | − 0.918 | 21.292 | 0.003a |

| Final model: cognitive domain—3 items (raw score range: 0–12) | ||||||

| Mean | − 1.813 | |||||

| Standard deviation | 1.764 | |||||

| Sample size | 730 | |||||

| Chi-square statistic (df) p value | 75.8970 (df: 21); p < 0.001 | |||||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.77602 | |||||

| Person Separation Index | 0.70994 | |||||

| Unidimensionality t-test (% significant) | 1.23% | |||||

| Differential Item Functioning (DIF) | None | |||||

*Item fit residual for HDQ21 (2.764) significant (p < 0.017; Bonferroni: 0.05/3) but retained due to clinical importance and need for minimum of 3 items in domain

aSignificant residual (p < 0.017; Bonferroni: 0.05/3) but fit residual F value < ± 2.5

Table 4.

Mental-Emotional Domain (5 items) - Overview of final SF-HDQ item level and domain model fit statistics

| Item # | Final SF-HDQ items | Item level statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental-emotional domain | Location | SE | Residual | ChiSq χ 2 | p value | |

| 24 | Feel anxious | 0.128 | 0.044 | 0.385 | 11.297 | 0.256 |

| 25 | Feel sad, down, or depressed | 0.092 | 0.044 | − 1.798 | 20.480 | 0.015 |

| 26 | Afraid for my future | − 0.232 | 0.041 | 0.088 | 5.906 | 0.749 |

| 27 | Lack confidence around others | 0.216 | 0.042 | 0.610 | 9.372 | 0.404 |

| 32 | Feel lonely | − 0.203 | 0.04 | 1.256 | 6.858 | 0.652 |

| Final model: mental-emotional domain—5 items (raw score range: 0–20) | ||||||

| Mean | -0.694 | |||||

| Standard deviation | 1.335 | |||||

| Sample size | 903 | |||||

| Chi-square statistic (df) p value | 53.9124 (df: 45) p = 0.170297a | |||||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.84935 | |||||

| Person Separation Index | 0.79154 | |||||

| Unidimensionality t-test (% significant) | 1.14% | |||||

| Differential Item Functioning (DIF) | None | |||||

aChi-square statistic not significant (ideal outcome)

Table 5.

Uncertainty Domain (5 items) - Overview of final SF-HDQ item level and domain model fit statistics

| Item # | Final SF-HDQ items | Item level statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty domain | Location | SE | Residual | ChiSq χ2 | p value | |

| 35 | Worry about future health living with HIV | − 0.114 | 0.041 | − 1.295 | 25.455 | 0.002a |

| 36 | Worry about lab test results such as my CD4 count and viral load | 0.701 | 0.041 | 0.084 | 13.146 | 0.156 |

| 39 | Worry about the side effects of HIV treatments | 0.069 | 0.038 | 0.793 | 5.110 | 0.825 |

| 40 | Worry about income or financial security living with HIV | − 0.608 | 0.035 | 0.900 | 6.796 | 0.658 |

| 41 | Worry what might happen to my family and friends if have an episode of illness | − 0.048 | 0.037 | 0.618 | 7.220 | 0.614 |

| Final model: uncertainty domain—5 items (raw score range: 0–20) | ||||||

| Mean | − 0.366 | |||||

| Standard deviation | 1.190 | |||||

| Sample size | 930 | |||||

| Chi-square statistic (df) p value | 58.7265 (df: 45) p = 0.0965b | |||||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.82314 | |||||

| Person Separation Index | 0.78006 | |||||

| Unidimensionality t-test (% significant) | 1.72% | |||||

| Differential Item Functioning (DIF) | None | |||||

aSignificant residual (p < 0.004; Bonferroni: 0.05/14) but fit residual F value < ± 2.5

bChi-square statistic not significant (ideal outcome). HDQ43—removed as this item considered to be captured by HDQ35 worry about future health

Table 6.

Day-to-Day Activities Domain (5 items) - Overview of final SF-HDQ item level and domain model fit statistics

| Item # | Final SF-HDQ items | Item level statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day-to-day activities domain | Location | SE | Residual | ChiSq χ2 | p value | |

| 49 | Unsteady on my feet | − 0.170 | 0.052 | 0.837 | 8.166 | 0.518 |

| 50 | Trouble walking | 0.554 | 0.055 | 1.055 | 14.058 | 0.120 |

| 53 | Trouble doing household chores such as cleaning, doing dishes, laundry, and cooking | 0.407 | 0.052 | − 1.374 | 27.246 | 0.001a |

| 54 | Trouble taking part in leisure or recreation, such as exercise or dancing | − 0.647 | 0.048 | − 0.982 | 14.090 | 0.119 |

| 55 | Trouble getting out to do errands, such as grocery shopping, banking, or doctor’s appointments | − 0.145 | 0.049 | − 0.069 | 13.207 | 0.153 |

| Final model: day-to-day activities domain—5 items (raw score range: 0–20) | ||||||

| Mean | − 1.494 | |||||

| Standard deviation | 1.168 | |||||

| Sample size | 675 | |||||

| Chi-square statistic (df) p value | 76.7660 (df: 45) p = 0.002 | |||||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.79477 | |||||

| Person Separation Index | 0.69006 | |||||

| Unidimensionality t-test (% significant) | 0.74% | |||||

| Differential Item Functioning (DIF) | None | |||||

Person Separatoin Index (PSI) approaching the threshold of ≥ 0.70

aSignificant residual (p < 0.006; Bonferroni: 0.05/9) but fit residual F value < ± 2.5

Table 7.

Social Inclusion Domain (7 items) - Overview of final SF-HDQ item level and domain model fit statistics

| Item # | Final SF-HDQ items | Item level statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social domain | Location | SE | Residual | ChiSq χ2 | p value | |

| 58 | Find hard to meet the needs of those I care for | 0.808 | 0.040 | − 0.302 | 11.066 | 0.271 |

| 62 | Feel work performance limited (0 = not at all or not applicable) | 0.046 | 0.035 | 0.455 | 5.823 | 0.757 |

| 63 | Struggle to maintain safe and stable housing - DIF(country)a | 0.570 | 0.060 | − 0.297 | 22.579 | 0.007 |

| 65 | Find it hard to ask others for help when go through an episode of illness - DIF(country) | − 0.310 | 0.034 | − 0.442 | 7.370 | 0.599 |

| 67 | Find it hard to start new intimate, sexual relationships living with HIV (0 = not at all or not applicable)a | − 0.609 | 0.058 | 2.426 | 8.228 | 0.511 |

| 68 | Tend to isolate myself from others because I am HIV positive | − 0.172 | 0.034 | − 3.142 | 24.214 | 0.003* |

| 69 | Find it hard to take part in leisure or recreational things because can’t afford it - DIF(country) | − 0.333 | 0.033 | 0.134 | 6.398 | 0.700 |

| Final model: social domain—7 items (raw score range: 0–24) | ||||||

| Mean | − 0.724 | |||||

| Standard deviation | 1.002 | |||||

| Sample size | 943 | |||||

| Chi-square statistic (df) p value | 86.6772 df: 54; p = 0.025679 | |||||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.79355 | |||||

| Person Separation Index | 0.74478 | |||||

| Unidimensionality t-test (% significant) | 1.27% | |||||

| Differential Item Functioniong (DIF) | Significant DIF for country (defined as F value significant and > 1.0 logit difference between groups)—3 items (HDQ63; HDQ65; HDQ69)b | |||||

*Residuals: HDQ68 (isolate self)—significant residual > -2.5 (p < 0.004; Bonferroni: 0.05/11). This item may be referring to a ‘strategy’ (isolating self) that may lead to challenges to social inclusion rather than social inclusion itself. However we retained due to clinical importance, and because if we remove this item from the model, it worsens fit (PSI = 0.676; model not shown)

Rescoring: aRescored to 3 response categories (0–2)—HDQ63 and HDQ67 to achieve ordered thresholds

HDQ61: deleted because captured in HDQ62—which describes limitations rather than prevention (all or nothing)

bDifferential Item Functioning (DIF): Significant DIF for HDQ63, HDQ65, and HDQ69. Items retained given clinical importance and expected cultural differences related to disability between samples of Canadian and Irish participants

Physical domain (20 items to 10 items)

In the initial model (20 items) (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.903; PSI: 0.869), three of the 20 items in the physical domain (HDQ3-nausea, HDQ8-trouble swallowing, and HDQ15 – unintentionally losing weight) were disordered (Additional file 1; Physical Domain Initial Model 1). Upon examination of the item category probability curves (not shown), we reordered HDQ3 (nausea) by collapsing response category ‘3’ and ‘4’ (4 response categories); and HDQ8 (trouble swallowing) by collapsing response categories 1, 2, and 3 (3 response categories). HDQ15 (intentionally losing weight) did not make sense with reordering, hence we removed this item.

Among the remaining 19 items, we deleted 7 items in a step-wise fashion with fit residuals > ± 2.5: HDQ9 (decreased libido); HDQ2 (diarrhea); HDQ12 (weakness in muscles); HDQ8 (trouble swallowing); HDQ18 (vision problems); HDQ19 (trouble hearing); and HDQ16 (lack of appetite) (12-item model). We deleted HDQ6 (numbness or tingling in feet) due to DIF (age group) and removed HDQ6 (numbness or tingling in my feet) in order to merge with HDQ5 (numbness or tingling in hands) which we will refine to one SF-HDQ item (numbness or tingling in my hands or feet) in a future iteration of the tool. We deleted HDQ14 (stomach cramps) due to DIF (age group) and retained HDQ13 (muscle cramps) despite having a large residual due to its clinical importance and lack of strong correlation with HDQ7 (aches and pains) (not shown) suggesting muscle cramps is a distinct concept. We did not merge muscle and stomach cramp items given these items refer to distinct sources of pain. The final physical domain included 10 items. The 10-item model achieved adequate model and item fit statistics, unidimensionality, and no items with DIF (Table 2; Figs. 1a, 2a; Additional files 1, 2).

Cognitive domain (3 items)

We did not remove any items from the cognitive domain as the original scale included 3 items. The 3-item model achieved adequate fit statistics and no items with DIF. One item (HDQ21-trouble remembering) had a standardized fit residual > 2.5, however we retained this item due to clinical importance and the requirement for the minimum of 3 items required to comprise this domain (Table 3; Figs. 1b, 2b; Additional files 1, 2).

Mental-emotional domain (11 items to 5 items)

In the initial model (11 items) (Cronbach alpha: 0.928; PSI: 0.891), no items in the mental-emotional domain were disordered; there were 5 items with fit residuals > ± 2.5 statistically significant after Bonferroni adjustment (Additional file 1; Mental-Emotional Domain Initial Model 1). Among the original 11 items, we deleted 4 items in a step-wise fashion with fit residuals > ± 2.5 and/or statistically significant after Bonferroni-adjustment (in order from greatest residuals): HDQ28 (uncomfortable with how my body looks); HDQ33 (discouraged about future life options); HDQ29 (feel isolated even when around others); HDQ34 (feel shut out by friends or family); and HDQ30 (feel embarrassed around others) resulting in 6 remaining items. We subsequently deleted HDQ31 (feel guilty) as it had a high item fit residual (3.02) even though it was not significant, due to its lack of clinical importance in relation to other items. The final mental-emotional domain included 5 items. The 5-item model achieved adequate fit statistics and no items with DIF (Table 4; Figs. 1c, 2c; Additional files 1, 2).

Uncertainty (14 items to 5 items)

In the initial model (14 items) (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.918; PSI: 0.899), 5 items were disordered (HDQ42—worry about remaining in the workforce, volunteering or school; HDQ43-worry about dying; HDQ45—worry about legal issues related to HIV disclosure; HDQ47—worry about transmitting HIV; and HDQ48-putting life decisions on hold) (Additional file 1; Uncertainty Domain Initial Model 1). Upon examination of the item category probability curves (not shown), an attempt to reorder categories in items HDQ42, HDQ47 and HDQ48 was non sensical, hence we removed these items. Among the remaining 11 items, we rescored HDQ43 and HDQ45 by collapsing response options ‘3’ and ‘4’ (resulting in 4 response options). We subsequently deleted 5 items in a stepwise fashion with fit residuals > ± 2.5 and/or with significance after Bonferroni adjustment (in order from greatest residuals): HDQ46 (worry about what others think if they knew I was HIV positive); HDQ44 (worry about bodily appearance); HDQ45 (worry about legal issues of telling others about HIV status); HDQ37 (worry about having a serious illness); and HDQ38 (worry about what the outcome of my next episodic of illness might be).

Among the remaining 6 items, we deleted HDQ43 (worry about dying) as conceptually we considered this item could be captured in HDQ35 (worry about my future health). The final uncertainty domain included 5 items. The 5-item model achieved adequate fit statistics and no significant DIF (Table 5; Figs. 1d, 2d; Additional files 1, 2).

Difficulties with day-to-day activities (9 items to 5 items)

In the initial model (9 items) (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.881; PSI: 0.796), no items were disordered (Additional file 1; Difficulties with Day-to-Day Activities Domain Initial Model 1). Among the original 9 items, we deleted 2 items in a step-wise fashion with fit residuals > ± 2.5 and/or with significance after Bonferroni adjustment: HDQ56 (trouble keeping track of finances); HDQ52 (trouble eating, bathing, grooming, dressing).

Among the remaining 7 items, we deleted HDQ51 (trouble climbing stairs) because of DIF for age group, and HDQ57 (trouble getting around such as driving, or taking public transport) due to DIF for country, and we considered this item conceptually as capturing part of HDQ55 (trouble getting out to do errands) as running errands involves community mobility. The final day domain included 5 items. The 5-item model achieved adequate fit statistics and no items with DIF. (Table 6; Figs. 1e, 2e; Additional files 1, 2).

Social inclusion (12 item to 7 items)

In the initial model (12 items) (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.903; PSI: 0.862), 2 items were disordered (HDQ63—struggle to maintain housing; HDQ67-find it hard to start new intimate, sexual relationships living with HIV) (Additional file 1; Social Domain Initial Model 1). Upon examination of the item category probability curves (not shown), we rescored HDQ63 (housing) and HDQ67 (relationships) by collapsing response categories ‘1’ ‘2’ and ‘3’ resulting in 3 response categories for these two items.

Among the 12 items, we deleted 4 items in a step-wise fashion with fit residuals > ± 2.5 and/or with significance after Bonferroni adjustment: HDQ64 (find it hard to talk to others about illness); HDQ59 (find hard to fulfill role as family or community member); HDQ66 (find hard to start new friendships); HDQ60 (feel cut off from friends, networks, communities).

Among the remaining 8 items, we deleted HDQ61 (illness prevents me from doing volunteer or paid work or going to school) due to DIF for country and because this item was conceptually captured by HDQ62 (work performance is limited because of my illness) and is preferred because it describes the limitation rather than absolute inability or prevention of work. The final social domain included 7 items. The 7-item model achieved adequate fit statistics. HDQ68 (tend to isolate self from others) had a significant large item fit residual after Bonferroni adjustment (F value: − 3.1; p = 0.003), and significant DIF for country, however if deleted from the model, the fit worsened, and we retained due to item clinical importance (Table 7; Figs. 1f, 2f; Additional files 1, 2).

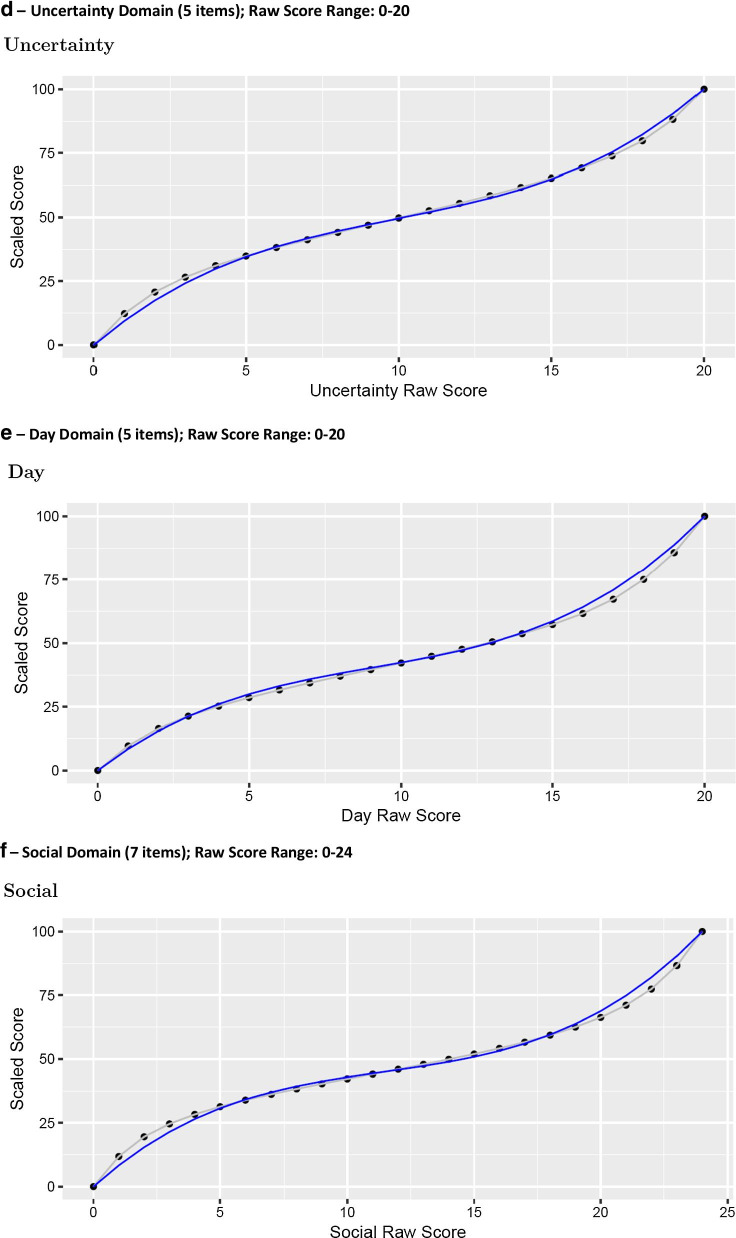

SF-HDQ scoring algorithms

Graphs in Fig. 3 (Fig. 3a–f) illustrate the person total sum score (total) against the Rasch person score, rescaled from logits to a score from 0 to 100 (grey line) for each domain. The blue line in Fig. 3 is the fitted (predicted) curve from the cubic function fit to those scores, scaled from 0 to 100.

Fig. 3.

Cubic models fitting raw SF-HDQ summary scores with scaled Rasch scores

Tables 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13 includes the Rasch-based, model predicted person score estimates for each value of a raw domain summed score for all six domains. We included predicted estimates for the original scale and the model predicted Rasch person-score on the 0–100 interval scale.

Table 8.

Conversation table - Physical domain (10 items)—raw summed scores to predicted Rasch person scores for SF-HDQ physical domain

| Physical domain (10 items) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Raw summed score—total Range: 0–39 |

Model predicted person score (location) | Model predicted person score (0–100 scale) |

| 0 | − 4.075 | 0 |

| 1 | − 3.261 | 6 |

| 2 | − 2.703 | 11 |

| 3 | − 2.321 | 16 |

| 4 | − 2.026 | 20 |

| 5 | − 1.783 | 24 |

| 6 | − 1.575 | 28 |

| 7 | − 1.393 | 31 |

| 8 | − 1.230 | 34 |

| 9 | − 1.083 | 37 |

| 10 | − 0.948 | 39 |

| 11 | − 0.823 | 41 |

| 12 | − 0.705 | 43 |

| 13 | − 0.594 | 45 |

| 14 | − 0.489 | 46 |

| 15 | − 0.387 | 47 |

| 16 | − 0.289 | 48 |

| 17 | − 0.194 | 49 |

| 18 | − 0.101 | 50 |

| 19 | − 0.009 | 51 |

| 20 | 0.082 | 52 |

| 21 | 0.173 | 53 |

| 22 | 0.264 | 54 |

| 23 | 0.356 | 55 |

| 24 | 0.450 | 56 |

| 25 | 0.546 | 57 |

| 26 | 0.645 | 59 |

| 27 | 0.748 | 60 |

| 28 | 0.856 | 62 |

| 29 | 0.970 | 64 |

| 30 | 1.093 | 66 |

| 31 | 1.226 | 68 |

| 32 | 1.371 | 71 |

| 33 | 1.535 | 74 |

| 34 | 1.722 | 77 |

| 35 | 1.943 | 81 |

| 36 | 2.215 | 85 |

| 37 | 2.573 | 90 |

| 38 | 3.107 | 95 |

| 39 | 3.903 | 100 |

Table 9.

Conversation table - Cognitive domain (3 items)—raw summed scores to predicted Rasch person scores for SF-HDQ cognitive domain

| Cognitive domain (3 items) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Raw summed score—total Range: 0–12 |

Model predicted person score (location) | Model predicted person score (0–100 scale) |

| 0 | − 5.086 | 0 |

| 1 | − 4.038 | 11 |

| 2 | − 3.069 | 20 |

| 3 | − 2.175 | 28 |

| 4 | − 1.367 | 35 |

| 5 | − 0.675 | 42 |

| 6 | − 0.036 | 48 |

| 7 | 0.601 | 54 |

| 8 | 1.286 | 61 |

| 9 | 2.083 | 68 |

| 10 | 3.013 | 77 |

| 11 | 4.156 | 87 |

| 12 | 5.560 | 100 |

Table 10.

Conversation table - Mental-Emotional domain (5 items)—raw summed scores to predicted Rasch person scores for SF-HDQ mental-emotional domain

| Mental-emotional domain (5 items) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Raw summed score—total Range: 0–20 |

Model predicted person score (location) | Model predicted person score (0–100 scale) |

| 0 | − 3.997 | 0 |

| 1 | − 3.098 | 10 |

| 2 | − 2.428 | 18 |

| 3 | − 1.930 | 26 |

| 4 | − 1.522 | 32 |

| 5 | − 1.174 | 37 |

| 6 | − 0.872 | 41 |

| 7 | − 0.604 | 45 |

| 8 | − 0.361 | 48 |

| 9 | − 0.135 | 51 |

| 10 | 0.082 | 53 |

| 11 | 0.295 | 56 |

| 12 | 0.509 | 58 |

| 13 | 0.730 | 61 |

| 14 | 0.964 | 64 |

| 15 | 1.219 | 68 |

| 16 | 1.505 | 72 |

| 17 | 1.841 | 78 |

| 18 | 2.264 | 84 |

| 19 | 2.867 | 91 |

| 20 | 3.726 | 100 |

Table 11.

Conversation table Uncertainty domain (5 items)—raw summed scores to predicted Rasch person scores for SF-HDQ uncertanity domain

| Uncertainty domain (5 items) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Raw summed score—total Range: 0–20 |

Model predicted person score (location) | Model predicted person score (0–100 scale) |

| 0 | − 3.683 | 0 |

| 1 | − 2.779 | 9 |

| 2 | − 2.155 | 17 |

| 3 | − 1.725 | 24 |

| 4 | − 1.393 | 30 |

| 5 | − 1.114 | 35 |

| 6 | − 0.868 | 39 |

| 7 | − 0.643 | 42 |

| 8 | − 0.431 | 45 |

| 9 | − 0.224 | 47 |

| 10 | − 0.020 | 50 |

| 11 | 0.187 | 52 |

| 12 | 0.398 | 55 |

| 13 | 0.620 | 57 |

| 14 | 0.857 | 61 |

| 15 | 1.117 | 65 |

| 16 | 1.411 | 70 |

| 17 | 1.758 | 75 |

| 18 | 2.194 | 82 |

| 19 | 2.811 | 90 |

| 20 | 3.683 | 100 |

Table 12.

Conversation table - Day-to-Day Activities domain (5 items)—raw summed scores to predicted Rasch person scores for SF-HDQ day-to-day activities domain

| Day domain (5 items) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Raw summed score—total Range: 0–20 |

Model predicted person score (location) | Model predicted person score (0–100 scale) |

| 0 | − 3.973 | 0 |

| 1 | − 3.103 | 8 |

| 2 | − 2.484 | 15 |

| 3 | − 2.043 | 21 |

| 4 | − 1.690 | 26 |

| 5 | − 1.388 | 30 |

| 6 | − 1.117 | 33 |

| 7 | − 0.867 | 36 |

| 8 | − 0.627 | 38 |

| 9 | − 0.394 | 40 |

| 10 | − 0.160 | 42 |

| 11 | 0.079 | 45 |

| 12 | 0.327 | 47 |

| 13 | 0.591 | 50 |

| 14 | 0.879 | 54 |

| 15 | 1.205 | 59 |

| 16 | 1.596 | 64 |

| 17 | 2.102 | 71 |

| 18 | 2.810 | 79 |

| 19 | 3.769 | 89 |

| 20 | 5.066 | 100 |

Table 13.

Conversation table Social domain (7 items)—raw summed scores to predicted Rasch person scores for SF-HDQ social domain

| Social domain (7 items) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Raw summed score—total Range: 0–24 |

Model predicted person score (location) | Model predicted person score (0–100 scale) |

| 0 | − 3.509 | 0 |

| 1 | − 2.627 | 8 |

| 2 | − 2.051 | 15 |

| 3 | − 1.675 | 21 |

| 4 | − 1.397 | 27 |

| 5 | − 1.172 | 31 |

| 6 | − 0.980 | 34 |

| 7 | − 0.810 | 37 |

| 8 | − 0.653 | 39 |

| 9 | − 0.505 | 41 |

| 10 | − 0.362 | 43 |

| 11 | − 0.222 | 44 |

| 12 | − 0.081 | 46 |

| 13 | 0.062 | 47 |

| 14 | 0.209 | 49 |

| 15 | 0.363 | 51 |

| 16 | 0.529 | 53 |

| 17 | 0.710 | 56 |

| 18 | 0.914 | 59 |

| 19 | 1.150 | 64 |

| 20 | 1.434 | 69 |

| 21 | 1.791 | 75 |

| 22 | 2.264 | 82 |

| 23 | 2.951 | 90 |

| 24 | 3.948 | 100 |

Additional file 4 provides the scoring algorithms for each domain that will yield simple Rasch-based interval SF-HDQ domain scores (range: 0–100) with higher scores indicating greater severity of disability.

Discussion

The Short-Form HIV Disability Questionnaire (SF-HDQ) is comprised of 35 items (reduced from the original 69-items) spanning six domains: physical (10 items), cognitive (3 items), mental-emotional (5 items), uncertainty (5 items), day-to-day activities (5 items), and social (7 items). Each domain yields an interval scale score derived from the Rasch model ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater severity of disability. Among the final 35 items, 3 were reordered: 1 item in the physical domain was rescored to 4 categories (HDQ3); and 2 items in social domain (HDQ63 and HDQ67) were rescored to 3 categories to result in ordered categories. All remaining items retained original five categories ranging from no challenge (0) to extreme difficulty (4).

Decisions to retain or remove items in the final SF-HDQ model required consideration of the Rasch model results in combination with clinical relevance of items. The development of the SF-HDQ involved multiple iterations to determine ideal fit that considered a combination of model fit indices, item fit indices (fit residuals), extent to which an item may be captured conceptually by another item in the domain, and clinical importance (Additional file 1). All but one domain met pre-specified criteria for model fit, demonstrated by domain Cronbach’s alphas and PSIs ≥ 0.70 with the exception of difficulties with day-to-day activities domain (PSI = 0.69) (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7). We considered this acceptable given the proximity to the threshold of model fit, and this model demonstrated ideal unidimensionality over other model iterations with PSIs ≥ 0.70 (Additional file 1). While three items in the final model (HDQ53, HDQ35, HDQ22) demonstrated significance for fit residuals, the absolute residual value was < 2.5, hence we retained them in the model. Two items (HDQ21, HDQ68) possessed significance for fit residuals > 2.5 or < − 2.5. We retained HDQ21 due to clinical importance [53, 54] and the need for a minimum of three items in the cognitive domain in order to comprise a latent variable [47, 48]. HDQ68 (tend to isolate self) may be referring to a ‘strategy’ that may lead to challenges to social inclusion rather than comprise the concept of social inclusion itself. Nevertheless, we retained due to clinical importance [55–58], and if removed from the model, it worsened fit (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7).

DIF for country resulted in three items in the social domain (HDQ63: housing; HDQ65: find it hard to ask others for help; HDQ69: find it hard to take part in leisure or recreational activities), which we retained due to their clinical importance (Table 7). DIF for country may be explained by the cultural differences that may exist between the Canadian and Irish participants and the willingness for participants to disclose their susceptibility to chronic illness and challenges living with HIV [59]. Differences in societal structures and diversity across health system settings can influence experiences and interpretations of disability. Future cross-cultural assessment of the SF-HDQ across countries will be important for determining international utility of the SF-HDQ in clinical and community-based practice [60, 61].

Each domain represents a dimension of disability, with its own domain scores that collectively describe the larger construct of disability. The scoring algorithms (Additional file 4) provide the opportunity to automatically generate domain scores with electronic administration using scoring software so that researchers, clinicians and adults living with HIV can obtain domain scores immediately upon completion. The scoring conversion charts (Tables 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) will allow clinicians who administer the SF-HDQ using paper-based methods in clinic to easily convert the raw summed domain score to the Rasch interval scale score (0–100). This, with the reduced length of the questionnaire, will enhance the clinical utility of the SF-HDQ.

Implications for practice and research

This study is the first to establish a PROM to assess the multi-dimensional nature of disability among adults aging with HIV. By retaining the six domain structure of the SF-HDQ, the PROM builds on the previously validated Episodic Disability Framework and HDQ with adults living with HIV [17, 19, 24, 25, 32]. Results will help to advance instrumentation and methods for PROM implementation to enhance feasibility, relevance and ease of use in clinical practice. For individuals aging with multimorbidity and complex health needs, PROMs should be embedded in individuals’ personalized needs and goals for care [62]. Standardized PROMs that capture the nature, fluctuation and extent of disability are critical to identify health priorities, to guide timely and appropriate care, and to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions for those aging with HIV [63–65]. The SF-HDQ has the potential to enhance person-provider communication, and identify an individual’s needs enhancing overall person-centered care [66, 67]. HIV-specific PROMs such as the SF-HDQ are particularly important for HIV care as it goes beyond traditional outcome measures of viral load or survival to describe person-centred outcomes (mental health, social inclusion, uncertainty) and their change over time, enhance communication by empowering adults aging with HIV to articulate their health challenges and needs, facilitate goal-setting, and guide referrals to available services. At the service delivery level, the SF-HDQ may help clinics or community-based organizations to better understand the changing needs of individuals as they age with HIV, evaluate the impact of interventions, programs and models of service delivery, and inform areas of resource allocation for future programming and service provision [68].

Our Rasch analysis focused on the severity scale of the HDQ building on our earlier work using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, and structural equation modeling to establish the domain structure and validate the six latent constructs that comprise disability in the HDQ, and examine relationships between dimensions of disability [25, 32, 52]. This work directly addresses one of the seven key research priorities in HIV, aging and rehabilitation to advance the development and use of PROMs in HIV and aging [69]. While our aim developing the SF-HDQ is to facilitate uptake for use in clinical and community-based practice, the SF-HDQ also may reduce respondent burden in research studies involving multiple PROMs administered in combination. Next steps include refinement of the SF-HDQ, such as minor wording revisions, questionnaire instructions, response option categories for the three reordered items, and the numbering (and order) of SF-HDQ items.

Our approach is not without limitations. Only 18% of the sample were women, which is below the estimated prevalence of women living with HIV in Canada (23%) and Ireland (29%) [70, 71], and few participants identified as trans or two spirited limiting our DIF analysis for gender. Furthermore, the difference in sample sizes across the Canadian and Irish samples (almost 10:1 ratio) may have increased the probability of type I error as well as reduced the power of DIF detection [72, 73]. The SF-HDQ was derived from adults aging with HIV in high income countries. While validation work is underway in South Africa with the original HDQ, future examination of the properties of the SF-HDQ with adults living with HIV in low or middle-income contexts is warranted. Future work should include measurement property assessment including cross-cultural validity of the SF-HDQ for use with adults living with HIV in countries where there may be different cultural perspectives of disability related to country. Lastly, our Rasch analysis was limited to cross-sectional HDQ data. Work is underway to examine the consistency of SF-HDQ scores with the Rasch model over time using long-form HDQ data with a sample of adults living with HIV engaged in an exercise intervention study in Canada [74].

Conclusions

The newly proposed 35-item SF-HDQ offers a brief yet comprehensive patient-reported outcome measure of disability to describe the nature and extent of disability experienced by adults living with HIV. The scoring algorithm offers a feasible way to convert raw summed domain scores to the Rasch-based score on an interval level scale ranging from 0 to 100. This shortened questionnaire and its new scoring algorithm may be used by clinicians, researchers, and other care providers working in busy clinical and community-based settings as a tool to comprehensively measure disability and to better identify the health-related needs of adults living with HIV.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1 Summary of Fit Statistics for the Initial to Final Models of the SF-HDQ Domains.

Additional file 2 Item Category Probability Curves for SF-HDQ Items (n=35 items).

Additional file 3 Overview of Original HDQ Items and Final SF-HDQ Items.

Additional file 4 Scoring Algorithms for SF-HDQ Domains.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Veronica Murrey (Cicely Saunders Institute, King’s College London) and Rachel Aubry (University of Toronto) for their contributions to this study. The authors also acknowledge members of the HIV Health and Rehabilitation Survey (HHRS) Study and Ireland HDQ Validation Study from which the original data for this study were derived. We thank participants from the HIV Health and Rehabilitation Survey (HHRS) study and Ireland HDQ Validation Study. We thank collaborators who were involved in the original studies from which these data were collected including the GUIDE Clinic, St. James’s Hospital, Dublin, Ireland; Open Doors, Dublin, Ireland; Realize, Canada; Toronto People With AIDS (PWA) Foundation; Dr. Peter AIDS Foundation (Vancouver), Nine Circles Community Health Centre (Winnipeg); AIDS Niagara; AIDS Committee of Durham Region; and AIDS Committee of Toronto.

Abbreviations

- DIF

Differential item functioning

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- HDQ

HIV Disability Questionnaire

- PCA

Principal components analysis

- PROM

Patient-reported outcome measure

- PSI

Person Separation Index/Indices

- SF-HDQ

Short-form HIV Disability Questionnaire

Authors’ contributions

KKO led the conceptual design of the study, acquisition of funding, recruitment and data collection from which the HDQ were derived, merging of the datasets, conducted the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. MD provided guidance on the Rasch approach, analysis and interpretations, and drafting the manuscript. AMD provided guidance on the Rasch analytical approach, analysis and interpretations, scoring algorithm, participated in acquisition of funding, and drafting the manuscript. RH participated in the acquisition of funding, analytical interpretations, and drafting the manuscript. EN and GW participated in the analytical interpretations and drafting the manuscript. LA conducted the analysis to develop the scoring algorithm and participated the drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a Fellowship from the British Academy for Humanities and Social Sciences and the National Institute On Aging of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Award Number R21AG062380). Kelly K. O’Brien (KKO) is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Episodic Disability and Rehabilitation. The British Academy, NIH, and Canada Research Chairs program did not have a role in the development of the study design, data collection or analysis, interpretation of results, or in writing this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during this study may be available by request to the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We received ethics approval from Research Ethics Boards (REB) at the University of Toronto, HIV/AIDS Research Ethics Board (Protocol #38152). This study involved a secondary data analysis with anonymized data sets from earlier studies whereby written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the original studies by individuals answering ‘yes’ to the question ‘I agree to participate in this research study’.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12955-020-01643-2.

References

- 1.Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet. 2013;382(9903):1525–1533. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61809-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Public Health Agency of Canada. Summary: estimates of HIV incidence, prevalence and proportion undiagnosed in Canada, 2014. Surveillance and Epidemiology Division, Professional Guidelines and Public Health ractice Division, Centre for Communicable Disease and Infection Control, Public Health Agency of Canada. 2015.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control. HIV among people aged 50 and over. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/olderamericans/index.html. Accessed 17 Dec 2020.

- 4.Yin Z, Brown AE, Hughes G, Nardone A, Gill ON, Delpech VC, et al. Over half of people in HIV care in the United Kingdom by 2028 will be aged 50 years or above (HIV in the United Kingdom 2014 Report: data to end 2013) London: Public Health England; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kendall CE, Wong J, Taljaard M, Glazier RH, Hogg W, Younger J, et al. A cross-sectional, population-based study measuring comorbidity among people living with HIV in Ontario. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasse B, Ledergerber B, Furrer H, Battegay M, Hirschel B, Cavassini M, et al. Morbidity and aging in HIV-infected persons: the Swiss HIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(11):1130–1139. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guaraldi G, Orlando G, Zona S, Menozzi M, Carli F, Garlassi E, et al. Premature age-related comorbidities among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(11):1120–1126. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balogun JA, Kaplan MT, Miller TM. The effect of professional education on the knowledge and attitudes of physical therapist and occupational therapist students about acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Phys Ther. 1998;78(10):1073–1082. doi: 10.1093/ptj/78.10.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown TT, Qaqish RB. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis: a meta-analytic review. AIDS. 2006;20(17):2165–2174. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801022eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vance DE, Mugavero M, Willig J, Raper JL, Saag MS. Aging with HIV: a cross-sectional study of comorbidity prevalence and clinical characteristics across decades of life. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2011;22(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erlandson KM, Schrack JA, Jankowski CM, Brown TT, Campbell TB. Functional impairment, disability, and frailty in adults aging with HIV-infection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11(3):279–290. doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0215-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2011;75(23):2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valcour V, Shikuma C, Shiramizu B, Watters M, Poff P, Selnes O, et al. Higher frequency of dementia in older HIV-1 individuals: the Hawaii aging with HIV-1 cohort. Neurology. 2004;63(5):822–827. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000134665.58343.8D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Gail MH, Hall HI, Li J, Chaturvedi AK, et al. Cancer burden in the HIV-infected population in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(9):753–762. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collaboration ATC. Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(8):e349–e356. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30066-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willard S, Holzemer WL, Wantland DJ, Cuca YP, Kirksey KM, Portillo CJ, et al. Does "asymptomatic" mean without symptoms for those living with HIV infection? AIDS Care. 2009;21(3):322–328. doi: 10.1080/09540120802183511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Brien KK, Bayoumi AM, Strike C, Young NL, Davis AM. Exploring disability from the perspective of adults living with HIV/AIDS: development of a conceptual framework. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:76. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erlandson KM, Allshouse AA, Jankowski CM, Mawhinney S, Kohrt WM, Campbell TB. Relationship of physical function and quality of life among persons aging with HIV infection. AIDS. 2014;28(13):1939–1943. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Brien KK, Davis AM, Strike C, Young NL, Bayoumi AM. Putting episodic disability into context: a qualitative study exploring factors that influence disability experienced by adults living with HIV/AIDS. J Int AIDS Soc. 2009;12(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Havlik RJ, Brennan M, Karpiak SE. Comorbidities and depression in older adults with HIV. Sexual Health. 2011;8(4):551–559. doi: 10.1071/SH11017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shippy RA, Karpiak SE. The aging HIV/AIDS population: fragile social networks. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(3):246–254. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331336850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siemon J, Blenkhorn L, Wilkins S, O'Brien KK, Solomon P. A grounded theory of social participation among older women living with HIV. Can J Occup Ther. 2013;80(4):241–250. doi: 10.1177/0008417413501153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roger KS, Mignone J, Kirkland S. Social aspects of HIV/AIDS and aging: a thematic review. Can J Aging La revue canadienne du vieillissement. 2013;32(3):298–306. doi: 10.1017/S0714980813000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Brien KK, Bayoumi AM, King K, Alexander R, Solomon P. Community engagement in health status instrument development: experience with the HIV disability questionnaire. Prog Community Health Partnersh Res Educ Action. 2014;8(4):549–559. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2014.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Brien KK, Solomon P, Bayoumi AM. Measuring disability experienced by adults living with HIV: assessing construct validity of the HIV Disability Questionnaire using confirmatory factor analysis. BMJ Open. 2014;4(8):e005456. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Brien KK, Solomon P, Bergin C, O'Dea S, Stratford P, Iku N, et al. Reliability and validity of a new HIV-specific questionnaire with adults living with HIV in Canada and Ireland: the HIV Disability Questionnaire (HDQ) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:124. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0310-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Brien KK, Bayoumi AM, Bereket T, Swinton M, Alexander R, King K, et al. Sensibility assessment of the HIV Disability Questionnaire. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(7):566–577. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.702848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Brien KK, Kietrys D, Galantino ML, Parrott JS, Davis T, Tran Q, et al. Reliability and Validity of the HIV Disability Questionnaire (HDQ) with adults living with HIV in the United States. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2019;18:2325958219888461. doi: 10.1177/2325958219888461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown DA, Simmons B, Boffito M, Aubry R, Nwokolo N, Harding R, et al. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the HIV Disability Questionnaire among adults living with HIV in the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional self-report measurement study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(7):e0213222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Brien KK, Vader K, Chan Carusone S, Baxter L, Ibanez-Carrasco F, Stewart A, et al., editors. Examining the utility of the HIV Disability Questionnaire (HDQ) in clinical practice: perspectives of adults aging with HIV and health care provdiers. In: 29th Annual Canadian conference on HIV/AIDS research; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Tennant A, McKenna SP, Hagell P. Application of Rasch analysis in the development and application of quality of life instruments. Value Health J Int Soc Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2004;7(Suppl 1):S22–S26. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.7s106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Brien KK, Bayoumi AM, Stratford P, Solomon P. Which dimensions of disability does the HIV Disability Questionnaire (HDQ) measure? A factor analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(13):1193–1201. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.949358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tennant A, Conaghan PG. The Rasch measurement model in rheumatology: what is it and why use it? When should it be applied, and what should one look for in a Rasch paper? Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(8):1358–1362. doi: 10.1002/art.23108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tennant A, Penta M, Tesio L, Grimby G, Thonnard JL, Slade A, et al. Assessing and adjusting for cross-cultural validity of impairment and activity limitation scales through differential item functioning within the framework of the Rasch model: the PRO-ESOR project. Med Care. 2004;42(1 Suppl):I37–48. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000103529.63132.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rusch T, Lowry PB, Mair P, Treiblmaier H. Breaking free from the limitations of classical test theory: Developing and measuring information systems scales using item response theory. Inf Manag. 2017;54:189–203. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2016.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cappelleri JC, Jason Lundy J, Hays RD. Overview of classical test theory and item response theory for the quantitative assessment of items in developing patient-reported outcomes measures. Clin Ther. 2014;36(5):648–662. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tennant A, Pallant JF. Unidimensionality matters. Rasch Meas Trans. 2006;20:1048–1051. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tennant A. Guidelines for reporting studies using Rasch analysis. https://www.medicaljournals.se/jrm/guidelines-for-reporting-studies-using-rasch-analysis. Accessed 17 Dec 2020.

- 39.Bond TG, Fox CM. Applying the Rasch model: fundamental measurement in the human sciences. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andrich D. A rating formulation for ordered response categories. Psychometrika. 1978;43(4):561–573. doi: 10.1007/BF02293814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dzingina M, Higginson IJ, McCrone P, Murtagh FEM. Development of a patient-reported palliative care-specific health classification system: the POS-E. The Patient. 2017;10(3):353–365. doi: 10.1007/s40271-017-0224-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brazier JE, Rowen D, Mavranezouli I, Tsuchiya A, Young T, Yang Y, et al. Developing and testing methods for deriving preference-based measures of health from condition-specific measures (and other patient-based measures of outcome) Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(32):1–114. doi: 10.3310/hta16320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bland JM, Altman DG. Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni method. BMJ. 1995;310(6973):170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6973.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith EV., Jr Detecting and evaluating the impact of multidimensionality using item fit statistics and principal component analysis of residuals. J Appl Meas. 2002;3(2):205–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.RUMM Laboratory Pty Ltd . RUMM2030. Western Australia: Duncraig; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kline P. An easy guide to factor analysis. New York: Routledge; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hatcher L. A step-by-step approach to using SAS for factor analysis and structural equation modeling. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Linacre JM. Optimizing rating scale category effectiveness. J Appl Meas. 2002;3(1):85–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Linacre JM. Investigating rating scale category utility. J Outcome Meas. 1999;3(2):103–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perruccio AV, Stefan Lohmander L, Canizares M, Tennant A, Hawker GA, Conaghan PG, et al. The development of a short measure of physical function for knee OA KOOS-Physical Function Shortform (KOOS-PS)—an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2008;16(5):542–550. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Brien KK, Hanna S, Solomon P, Worthington C, Ibanez-Carrasco F, Chan Carusone S, et al. Characterizing the disability experience among adults living with HIV: a structural equation model using the HIV disability questionnaire (HDQ) within the HIV, health and rehabilitation survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):594. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4203-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vance DE, Ross LA, Downs CA. Self-reported cognitive ability and global cognitive performance in adults with HIV. J Neurosci Nurs J Am Assoc Neurosci Nurses. 2008;40(1):6–13. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200802000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vance DE, Fazeli PL, Moneyham L, Keltner NL, Raper JL. Assessing and treating forgetfulness and cognitive problems in adults with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013;24(1 Suppl):S40–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoo-Jeong M, Hepburn K, Holstad M, Haardorfer R, Waldrop-Valverde D. Correlates of loneliness in older persons living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2020;32(7):869–876. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1659919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cahill S, Valadez R. Growing older with HIV/AIDS: new public health challenges. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):e7–e15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mazonson P, Berko J, Loo T, Kane M, Zolopa A, Spinelli F, et al. Loneliness among older adults living with HIV: the "older old" may be less lonely than the "younger old". AIDS Care. 2020:1–8. 10.1080/09540121.2020.1722311. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Harris M, Brouillette MJ, Scott SC, Smaill F, Smith G, Thomas R, et al. Impact of loneliness on brain health and quality of life among adults living with HIV in Canada. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;84(4):336–344. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shaw SJ, Huebner C, Armin J, Orzech K, Vivian J. The role of culture in health literacy and chronic disease screening and management. J Immigr Minor Health Center Minor Public Health. 2009;11(6):460–467. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Epstein J, Santo RM, Guillemin F. A review of guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires could not bring out a consensus. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(4):435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25(24):3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woodchis WP. Performance measurement for people with multimorbidity and complex health needs. Healthc Q. 2016;19(2):44–48. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2016.24698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Valderas JM, Kotzeva A, Espallargues M, Guyatt G, Ferrans CE, Halyard MY, et al. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(2):179–193. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9295-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Field J, Holmes MM, Newell D. PROMs data: Can it be used to make decisions for individual patients? A narrative review. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2019;10:233–241. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S156291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ovretveit J, Zubkoff L, Nelson EC, Frampton S, Knudsen JL, Zimlichman E. Using patient-reported outcome measurement to improve patient care. Int J Qual Health Care J Int Soc Qual Health Care ISQua. 2017;29(6):874–879. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzx108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cella D, Hahn EA, Jensen SE, Butt Z, Nowinski CJ, Rothrock N, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in performance measurement. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Calvert M, Kyte D, Price G, Valderas JM, Hjollund NH. Maximising the impact of patient reported outcome assessment for patients and society. BMJ. 2019;364:k5267. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k5267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bristowe K, Clift P, James R, Josh J, Platt M, Whetham J, et al. Towards person-centred care for people living with HIV: What core outcomes matter, and how might we assess them? A cross-national multi-centre qualitative study with key stakeholders. HIV Med. 2019;20(8):542–554. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O'Brien KK, Ibanez-Carrasco F, Solomon P, Harding R, Brown D, Ahluwalia P, et al. Research priorities for rehabilitation and aging with HIV: a framework from the Canada-International HIV and Rehabilitation Research Collaborative (CIHRRC) AIDS Res Ther. 2020;17(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s12981-020-00280-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Surveillance and Epidemiology Division, Professional Guidelines and Public Health Practice Division, Centre for Communicable Disease and Infection Control, Canada, Public Health Agency. Summary: estimates of HIV incidence, prevalence and Canada’s progress on meeting the 90-90-90 HIV targets, 20162018. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/summary-estimates-hiv-incidence-prevalence-canadas-progress-90-90-90.html. Accessed 17 Dec 2020.

- 71.UNAIDS. Ireland Country Factsheet 20192019. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/ireland. Accessed 17 Dec 2020.

- 72.Berrío AI, Herrera AN, Gómez-Benito J. Effect of sample size ratio and model misfit when using the difficulty parameter differences procedure to detect DIF. J Exp Educ. 2019;87(3):367–383. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2018.1435502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Herrera AN, Gómez J. Influence of equal or unequal comparison group sample sizes on the detection of differential item functioning using the Mantel-Haenszel and logistic regression techniques. Qual Quant. 2008;42:739. doi: 10.1007/s11135-006-9065-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.O'Brien KK, Bayoumi AM, Solomon P, Tang A, Murzin K, Chan Carusone S, et al. Evaluating a community-based exercise intervention with adults living with HIV: protocol for an interrupted time series study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(10):e013618. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1 Summary of Fit Statistics for the Initial to Final Models of the SF-HDQ Domains.

Additional file 2 Item Category Probability Curves for SF-HDQ Items (n=35 items).

Additional file 3 Overview of Original HDQ Items and Final SF-HDQ Items.

Additional file 4 Scoring Algorithms for SF-HDQ Domains.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during this study may be available by request to the corresponding author on reasonable request.