Abstract

Low muscle mass and frailty are especially prevalent in older women and may be accelerated by age-related inflammation. Habitual physical activity throughout the life span (lifelong exercise) may prevent muscle inflammation and associated pathologies, but this is unexplored in women. This investigation assessed basal and acute exercise-induced inflammation in three cohorts of women: young exercisers (YE, n = 10, 25 ± 1 yr, : 44 ± 2 mL/kg/min, quadriceps size: 59 ± 2 cm2), old healthy nonexercisers (OH, n = 10, 75 ± 1 yr, : 18 ± 1 mL/kg/min, quadriceps size: 40 ± 1 cm2), and lifelong aerobic exercisers with a 48 ± 2 yr aerobic training history (LLE, n = 7, 72 ± 2 yr, : 26 ± 2 mL/kg/min, quadriceps size: 42 ± 2 cm2). Resting serum IL-6, TNF-α, C-reactive protein (CRP), and IGF-1 were measured. Vastus lateralis muscle biopsies were obtained at rest (basal) and 4 h after an acute exercise challenge (3 × 10 reps, 70% 1-repetition maximum) to assess gene expression of cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-4, IL-1Ra, TGF-β), chemokines (IL-8, MCP-1), cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX-1, COX-2), prostaglandin E2 synthases (mPGES-1, cPGES) and receptors (EP3–4), and macrophage markers (CD16b, CD163), as well as basal macrophage abundance (CD68+ cells). The older cohorts (LLE + OH combined) demonstrated higher muscle IL-6 and COX-1 (P ≤ 0.05) than YE, whereas LLE expressed lower muscle IL-1β (P ≤ 0.05 vs. OH). Acute exercise increased muscle IL-6 expression in YE only, whereas the older cohorts combined had the higher postexercise expression of IL-8 and TNF-α (P ≤ 0.05 vs. YE). Only LLE had increased postexercise expression of muscle IL-1β and MCP-1 (P ≤ 0.05 vs. preexercise). Thus, aging in women led to mild basal and exercise-induced inflammation that was unaffected by lifelong aerobic exercise, which may have implications for long-term function and adaptability.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY We previously reported a positive effect of lifelong exercise on skeletal muscle inflammation in aging men. This parallel investigation in women revealed that lifelong exercise did not protect against age-related increases in circulating or muscle inflammation and that preparedness to handle loading stress was not preserved by lifelong exercise. Further investigation is necessary to understand why lifelong aerobic exercise may not confer the same anti-inflammatory benefits in women as it does in men.

Keywords: acute exercise, inflammaging, inflammation, lifelong exercise, skeletal muscle

INTRODUCTION

Although the average life expectancy of women is ∼2.5 yr longer than that of men (50), health span (or disability-free life span) does not follow the same pattern (14, 16). In fact, women are more often affected by chronic conditions such as heart disease (86), osteoarthritis (68), Alzheimer’s (13) and other dementias (9), and physical frailty (16). Frailty, along with age-related skeletal muscle wasting or sarcopenia, is correlated with loss of independence and overall mortality (28, 29, 35). To aid in avoiding complications of age-related muscle decline, it is of great concern to continue to optimize strategies for protecting skeletal muscle mass and function into old age, especially in women.

In studies of predominantly male populations (33, 43–45), lifelong aerobic exercise appears to serve as a natural anti-inflammatory treatment and is associated with attenuated skeletal muscle mass decline. Mechanistically, this is thought to be the result of the complex molecular interplay between inflammatory signaling factors in skeletal muscle and muscle protein balance at rest and following exercise. Gene-level expression of key inflammatory signaling factors (e.g., cytokines, prostaglandins, chemokines, and their receptors) within skeletal muscle may signify the overall inflammatory burden, and thus the health, of muscle tissue. Furthermore, overt inflammation within a given tissue such as skeletal muscle may not be reflected systemically (3, 42). Thus, investigating the presence of chronic basal inflammation within the muscle may provide insight into the capacity of skeletal muscle to participate in its wide-ranging functions (e.g., locomotion and movement, metabolism, endocrine signaling, and immune preparedness).

Resistance exercise training is the most well-recognized countermeasure for age-related muscle wasting (34), and inflammation plays a critical role in its mechanism of action. Timely initiation and subsequent resolution of inflammation (7) facilitate protein accretion at the crux of long-term muscle hypertrophy (5, 53), a key outcome of resistance exercise training that may forestall or reverse the effects of aging. However, an inflammatory response to exercise that is dysregulated by aging (e.g., delayed and/or prolonged) may contribute to impaired ability to adapt to exercise and overall reduced or unchanged—rather than bolstered—muscle health (12, 66, 83). Supporting this, high basal inflammatory gene expression in skeletal muscle appears to be predictive of poor muscle hypertrophy in response to progressive resistance exercise training (42, 72), whereas anti-inflammatory drug consumption improves the efficacy of short-term resistance exercise training to protect or restore muscle mass in older adults (76, 78–80). Overall, the available evidence suggests that proper management of exercise-induced inflammation is critical for long-term skeletal muscle adaptation to stress.

Older women may demonstrate blunted hypertrophy in response to a resistance exercise regimen, especially with advancing age (18, 60). Our previous evidence suggests that this may be a consequence of heightened proteolytic signaling following acute resistance exercise (59) and/or impaired or delayed overall skeletal muscle signaling activity (61), and dysregulated inflammation may be linked to this phenomenon. Postmenopausal women may be particularly susceptible due to reductions in anti-inflammatory estrogen (31, 47, 82) that reportedly influences the response to acute exercise (1, 21, 48). Taken together, these findings point to the importance of prevention, rather than attempted reversal, of sarcopenia in older women.

We have previously shown that short-term (12 wk) aerobic training in older women reduces skeletal muscle proteolytic signaling (30), and lifelong aerobic exercise in women is partially protective of declines in cardiovascular fitness (20) and myofiber size (19), but not overall muscle mass (6). Presently, it remains unknown whether lifelong aerobic training in women confers long-term anti-inflammatory benefits. Based on findings in males (33), we hypothesized that lifelong aerobic exercise would partially attenuate the age-related increase in basal inflammation and preserve the inflammatory response to acute exercise. To investigate this, we performed a targeted analysis of the inflammatory profile in circulation and skeletal muscle of three cohorts of women: young exercisers, older nonexercisers, and lifelong aerobic exercisers.

METHODS

Subjects

This investigation included three cohorts of women: old lifelong exercisers (LLE, n = 7), old healthy nonexercisers (OH, n = 10), and young exercisers (YE, n = 10) (Table 1). Subjects were recruited from the greater Muncie, Indiana, area by newspaper advertisements, mailed flyers, and personal interaction. More extensive subject characteristics and more details regarding the recruitment and screening process, along with cardiovascular and skeletal muscle profiles, are presented by our research team elsewhere (6, 20). Enrolled individuals were free from acute or chronic illness (cardiac, pulmonary, liver, or kidney abnormalities; cancer; uncontrolled hypertension; insulin- or noninsulin-dependent diabetes; or other known metabolic disorders), free from orthopedic limitations (including any artificial joints), and they did not smoke or participate in other forms of tobacco use. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ball State University. For the YE group, all testing was timed according to the participants’ menstrual cycles, such that the serum cytokine blood draw and exercise challenge with skeletal muscle biopsies (approximately 1 mo later) occurred during the early follicular phase (days 1–7 after menstruation). All study procedures, risks, and benefits were explained to the subjects before giving written consent to participate.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Variable | Young Exercisers | Lifelong Exercisers | Old Healthy Nonexercisers |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 10 | 7 | 10 |

| Age, yr | 25 ± 1* | 72 ± 2 | 75 ± 1 |

| Height, cm | 167 ± 2 | 164 ± 2 | 157 ± 2 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 | 27 ± 1* |

| Body fat, % | 23 ± 1* | 30 ± 2† | 41 ± 2 |

| Circulating estrogen, pg/mL | 178 ± 30* | 83 ± 16 | 105 ± 10 |

| , mL/kg/min | 44 ± 2* | 26 ± 2† | 18 ± 1 |

| Quadriceps CSA, cm2 | 59 ± 2* | 42 ± 2 | 40 ± 1 |

| Quadriceps strength, Nm | 138 ± 10† | 105 ± 9 | 82 ± 4 |

| Quadriceps 1RM, kg | 80 ± 6* | 54 ± 4 | 42 ± 2 |

| Quadriceps power, W | 404 ± 38* | 221 ± 20 | 146 ± 10 |

| Steps per day | 11,518 ± 1,404* | 7,463 ± 683† | 6,801 ± 823 |

Values are means ± SE; n = no. of subjects. Additional cardiovascular and skeletal muscle data, as well as details of body fat (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry), maximal oxygen consumption (), muscle size (MRI) and function, and steps-per-day measurements are presented by us elsewhere (6, 20). BMI, body mass index; CSA, cross-sectional area; OH, old healthy; 1RM, 1-repetition maximum; , maximal oxygen consumption.

P ≤ 0.05 versus other groups.

P ≤ 0.05 versus OH.

Exercise histories were collected and extensively reviewed for all lifelong exercisers as previously described (20). Briefly, subjects were asked to report exercise mode, frequency, duration, intensity, competitive nature, and athletic achievements on a decade-by-decade basis, beginning at age 20. Subjects of the LLE group were aerobic exercisers (primarily runners and cyclists) who had a history of participating in a structured exercise on average 5 ± 1 days/wk for 7 ± 1 h/wk for 48 ± 2 yr (Table 2). Generally, women in the LLE group participated in running, cycling, swimming, skiing, dancing, and/or yoga for the majority of the reported exercise history. Notably included in the LLE group were several individuals who continue to compete in local, regional, and national races, including one subject who cycled ∼4,000 mi the year before testing and a national-level masters track and field athlete. Although OH control subjects were not involved in any structured exercise training, participation in leisure activities (e.g., golfing, leisurely walking, and community service) was not grounds for exclusion. YE consisted of active individuals who exercised 4–6 days/wk for ∼7 h/wk.

Table 2.

Exercise Training Histories

| Young Exercisers (n = 10) | Lifelong Exercisers (n = 7) | Old Healthy Nonexercisers (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total training years | 5 ± 1 | 48 ± 2 | - |

| Lifetime average | |||

| Frequency, day/wk | - | 4.6 ± 0.3 | - |

| Duration, h/wk | - | 6.6 ± 0.6 | - |

| Intensity* | - | 1.9 ± 0.1 | - |

| Current decade | |||

| Frequency, day/wk | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | - |

| Duration, h/wk | 7.3 ± 1.1 | 6.8 ± 1.0 | - |

| Intensity* | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | - |

Values are means ± SE. Lifetime average reflects current decade exercise habits for young exercisers.

Levels of self-reported training intensity were 1 (light), 2 (moderate), and 3 (hard).

In the case that a subject reported more than one training intensity, values were weighted and averaged (e.g., 80% of training at a 2 and 20% of training at a 3 resulted in an overall intensity of 2.2). More detailed exercise training histories are presented by us elsewhere (20).

Serum Inflammatory Markers

Methods for assessment of inflammatory factors have been reported previously by our research team (33). A resting, fasted blood draw was taken for measurement of circulating inflammatory markers. Samples were analyzed (LabCorp, Muncie, IN) for serum C-reactive protein (latex immunoturbidimetry), IL-6 and TNF-α (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), and IGF-1 (immunochemiluminometric assay).

Acute Exercise and Skeletal Muscle Biopsies

To provide a novel, unaccustomed muscle loading stimulus for both the untrained OH and aerobically trained cohorts, subjects completed a resistance exercise challenge of the knee extensors, consisting of three sets of 10 repetitions at 70% 1-repetition maximum (1RM), with 2-min rest between each set. When completed chronically, this acute exercise stimulus elicits significant increases in muscle size and strength in young and old individuals (60, 67, 74, 75, 87). Muscle biopsies (4) of the vastus lateralis were obtained before and 4 h after the resistance exercise challenge. This postexercise time point reflects a suitable time for interrogating the expression of numerous intramuscular regulators of muscle adaptation, including cytokine activity (38, 57–59, 61, 89). All biopsies were obtained in the fasted state (≥10 h), after at least 30 min of supine rest. Subjects remained in the laboratory and rested quietly during the 4-h postexercise period. Subjects also refrained from structured exercise and aspirin consumption for 72 h, alcohol consumption for 24 h, and caffeine the morning of the trial.

Following each muscle biopsy, excess blood, visible fat, and connective tissue were removed, and a portion of the muscle (∼20 mg) to be used for mRNA analysis was immediately frozen and then stored in liquid nitrogen. Before analysis, the muscle was transferred to 0.5 mL of RNAlater-ICE (Ambion, Austin, TX) and stored at −20°C until analysis. A portion of the muscle to be used for immunohistochemistry was oriented longitudinally in a mounting medium (tragacanth gum, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) atop a cork, frozen in isopentane cooled in liquid nitrogen, and subsequently stored in liquid nitrogen until analysis.

Gene Expression Measurements

Inflammatory factors listed in Table 3 were assessed in vastus lateralis skeletal muscle homogenates using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Muscle mRNA analyses were completed on all 27 subjects for basal expression (i.e., preexercise) and on 26 subjects for the 4-h postexercise (i.e., one individual from OH did not undergo the postexercise biopsy).

Table 3.

Nomenclature, gene information, and mRNA primer characteristics

| Common Name | Gene Name | Accession No. | Sequence (5′ → 3′) | Amplicon Size, bp | mRNA Region, bp | Annealing Temp, °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proinflammatory cytokines | ||||||

| IL-6 | IL6 | NM_000600.4 |

CTATGAACTCCTTCTCCACAAGCGCCTT GGGGCGGCTACATCTTTGGAATCTT |

127 | 61–187 | 60 |

| TNF-α | TNF | NM_000594.3 |

CCCAGGCAGTCAGATCATCTTCTCGAA CTGGTTATCTCTCAGCTCCACGCCATT |

149 | 390–538 | 60 |

| IL-1β | IL1B | NM_000576.2 |

GGATATGGAGCAACAAGTGGTG CGCAGGACAGGTACAGATTCT |

113 | 661–773 | 61 |

| Anti-inflammatory cytokines | ||||||

| IL-10 | IL10 | NM_000572.2 |

GGCGCTGTCATCGATTTCTTCC GGCTTTGTAGATGCCTTTCTCTTG |

101 | 430–530 | 60 |

| IL-4 | IL4 | NM_000589.3a |

TCTTCCTGCTAGCATGTGCC TGTTACGGTCAACTCGGTGC |

128 | 100–227 | 60 |

| IL-1Ra | IL1RN | NM_173842.2b |

AGCTGGAGGCAGTTAACATCA ACTCAAAACTGGTGGTGGGG |

102 | 375–476 | 60 |

| TGF-β | TGFB1 | NM_000660.6 |

ACCAACTATTGCTTCAGCTCCA GAAGTTGGCATGGTAGCCCT |

120 | 1683–1802 | 60 |

| PGE2/COX pathway components | ||||||

| COX-1 v1e | PTGS1 | NM_000962 |

CCCAGGAGTACAGCTACGAGCAGTTCTT CCAGCAATCTGGCGAGAGAAGGCAT |

101 | 1327–1427 | 60 |

| COX-1 v2e* | PTGS1 | NM_080591 |

GTCCAGTTCCAATACCGCAACCGCAT CCACCGATCTTGAAGGAGTCAGGCAT |

92 | 1237–1328 | 60 |

| COX-2f | PTGS2 | NM_000963.3 |

TTGCTGGCAGGGTTGCTGGTGGTA CATCTGCCTGCTCTGGTCAATGGAA |

86 | 1381–1466 | 60 |

| cPGESg | PTGES3 | NM_006601.6 |

AGGCCCGCCCACCAGTTCGC AGTCCCTTCGATCGTACCACTTTGCAG |

82 | 254–335 | 60 |

| mPGES-1h | PTGES | NM_004878.4 |

CGGAAGAAGGCCTTTGCCAACC GGGTAGATGGTCTCCATGTCGTTCC |

125 | 171–295 | 60 |

| EP3i | PTGER3 | NM_198715.2c |

CTGGTCTCCGCTCCTGATAA TTCAGTGAAGCCAGGCGAAC |

132 | 1113–1244 | 60 |

| EP4j | PTGER4 | NM_000958.2 |

GCTCGTGGTGCGAGTATTCGTCAACC TCCAGGGGTCTAGGATGGGGTTCA |

122 | 1453–1574 | 60 |

| Chemokines and macrophage surface markers | ||||||

| IL-8k | CXCL8 | NM_000584.3 |

GCTCTGTGTGAAGGTGCAGTTTTGCCAA GGCGCAGTGTGGTCCACTCTCAAT |

135 | 153–287 | 60 |

| MCP-1l | CCL2 | NM_002982.3 |

GCAATCAATGCCCCAGTCAC CTTGAAGATCACAGCTTCTTTGGG |

123 | 152–274 | 60 |

| CD16bm | FCGR3B | NM_001271037.1 |

CCAGGCCTCGAGCTACTTCA TGCCAAACCGATATGGACTTCT |

121 | 441–561 | 60 |

| CD163 | CD163 | NM_004244.5d |

CCCAGTGAGTTCAGCCTTTA TCAGCAGCAGTCTTAGGAATC |

140 | 3600–3739 | 60 |

One primer was designed for each variant of COX-1 based on our previous research (85). Top sequence reflects the forward primer and bottom sequence reflects the reverse primer. EP, E-prostanoid receptor; IL-6, interleukin-6; mPGES, microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase; TGF-β: transforming growth factor β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α

Primers detect variant 1 isoform 1 (NM_000589.3).

Primers detect all variants: variant 1 isoform 1 (NM_173842.2), variant 2 isoform 2 (NM_173841.2), variant 3 isoform 3 (NM_000577.4), variant 4 isoform 4 (NM_173843.2), and variant 5 isoform 4 (NM_001318914.1).

Primer detects variant 4 isoform 4 (NM_198714.1), variant 5 isoform 5 (NM_198715.2), variant 6 isoform 6 (NM_198716.1), variant 7 isoform 7 (NM_198717.1), variant 8 isoform 8 (NM_198718.1), variant 9 isoform 4 (NM_198719.1), and variant 11 isoform 4 (NM_001126044.1).

See text for definitions of abbreviations. Other aliases:

Prostaglandin-endoperoxidase synthase 1;

Prostaglandin-endoperoxidase synthase 2;

Prostaglandin E synthase 3;

Prostaglandin E synthase;

Prostaglandin E receptor 3;

Prostaglandin E receptor 4;

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8;

C-C motif chemokine ligand 2;

Fc fragment of IgG receptor IIIb.

Total extraction and RNA quality check.

Total RNA was extracted in TRI Reagent RT (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH). The quality and integrity [means ± SE; RNA integrity number (RIN) = 8.35 ± 0.05] of extracted RNA (84.80 ± 4.16 ng/µL) were evaluated using an RNA 6000 Nano LabChip kit on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) as previously described (26, 76).

Real-time polymerase chain reaction.

Oligo (dT)-primed first-strand cDNA was synthesized (96–144 ng of total RNA, depending on magnitude of target gene expression) using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For each target, quantification of mRNA levels was performed in duplicate in a 72-well Rotor-Gene Q Centrifugal Real-Time Cycler (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P0 (RPLP0) was selected as a housekeeping/reference gene, as previously done in human muscle (33, 46). RPLP0 was similar among the three groups at baseline (CT: 19.34 ± 0.04) and stable after exercise (CT: 19.15 ± 0.03). All primers used in this study were mRNA specific (on different exons and/or crossing over an intron) and designed for qPCR [Vector NTI Advance 9 software (Invitrogen) and Primer Design Tool (Entrez) NCBI/Primer-BLAST program] using SYBR Green chemistry (26). Primer details are presented in Table 3. A melting curve analysis was generated for all PCR runs to validate that only one product was present. For each run, a serial dilution curve was made using cDNA from a known amount (500–2,000 ng) of human skeletal muscle RNA (Ambion, Austin, TX) or human muscle samples collected in our laboratory. The amplification calculated by the Rotor-Gene software was specific and highly efficient (efficiency = 1.00 ± 0.01; R2 = 0.98 ± 0.00; slope = 3.34 ± 0.03). Basal gene expression among YE, LLE, and OH was compared using the 2−ΔCT (arbitrary units) method. Gene expression before and after the resistance exercise challenge was compared using the 2−ΔΔCT (fold-change) relative quantification method, as previously described (37, 38, 69, 78). On the basis of the principle of the calculation, the preexercise value and the associated variability should be very close to 1 for each group.

In the present study, this was true of all genes analyzed, and preexercise 2−ΔΔCT values were not statistically different among the groups (P > 0.05). Therefore, to simplify interpretation, preexercise expression for each gene is graphically represented as a dotted line at 1.0-fold.

Immunohistochemistry

For detection of skeletal muscle macrophages, transverse sections (7 µm) for histochemical analysis were cut on a microtome-cryostat (HM 525, Microm, Walldorf, Germany) at −20°C. Before staining, sections were air-dried in a humidified chamber for 30 min, then fixed in cold (−20°C) acetone for 10 min and rehydrated in PBS for 5 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 0.3% peroxide. Sections were incubated in anti-CD68 primary antibody (1:100 dilution in PBS, M0718, Dako, Carpinteria, CA) at 4°C overnight (15 h) in a humidified chamber. Sections were treated using HistoStain Kit (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD) and visualized using aminoethyl carbazole (AEC) single solution substrate (Invitrogen), then counterstained with hematoxylin (Gill No. 3, Sigma) for 30 s. All analyses included a CD68 negative control (no primary antibody during incubation) and an internal positive control [skeletal muscle biopsy obtained following a damaging exercise protocol similar to those shown to elicit macrophage infiltration (85)]. Macrophage abundance is represented as CD68+ cells/100 fibers [the number of CD68+ cells relative to the number of muscle fibers assessed (average: 139 ± 4 fibers per subject), multiplied by a factor of 100] and CD68+ cell density [number of CD68+ cells in an analyzed area of muscle (average: 644,572 ± 8,408 µm2 per subject)]. All measurements were completed by two independent investigators and averaged to represent each sample.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare subject characteristics, training histories, serum inflammatory factor levels, macrophage parameters, and basal gene expression (2−ΔCT method) among the three groups. A two-way ANOVA (group × time) was completed to evaluate gene expression (2−ΔΔCT method) in response to exercise. Where no difference between LLE and OH was found, the two older groups were collapsed to assess the impact of aging on basal gene expression and postexercise expression levels independent of training status. Post hoc comparisons were made with Tukey’s test. Significance was declared at P ≤ 0.05. Trends were reported when P > 0.05 and <0.10 (three instances). Data are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics

Subject characteristics are reported in detail in previous publications from our research team (6, 20) and recapitulated in Tables 1 and 2. Notably, circulating estrogen was 53% lower in LLE and 41% lower in OH than in YE (P ≤ 0.05). Additionally, exhibited a hierarchical pattern such that OH < LLE < YE, whereas quadriceps cross-sectional area (CSA), power, and strength measured via 1RM were significantly higher in YE and not different between the two older cohorts.

Basal Circulating Inflammatory Factors

Serum concentrations of inflammatory factors are presented in Table 4. CRP tended to be more abundant in LLE and OH combined (+180%) versus YE (P = 0.09). Both older groups had significantly lower circulating IGF-1 than YE (62% lower in OH and 60% lower in LLE, P ≤ 0.05). No differences were noted across the groups for circulating IL-6 or TNF-α.

Table 4.

Basal serum concentrations of inflammatory factors and intramuscular macrophage abundance

| Young Exercisers | Lifelong Exercisers | Old Healthy Nonexercisers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum inflammatory factors | |||

| IL-6, pg/mL | 2.6 ± 1.5 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 3.2 ± 0.6 |

| TNF-α, pg/mL | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.3 |

| CRP, mg/L | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 2.5 ± 0.9 |

| IGF-1, ng/mL | 223 ± 20 | 89 ± 9* | 84 ± 7* |

| Intramuscular macrophage abundance | |||

| CD68+ cells/100 fibers | 5.3 ±1.2 | 5.0 ± 0.6 | 5.2 ± 1.1 |

| CD68+ cells/mm2 | 10.8 ± 2.0 | 10.1 ± 1.3 | 11.7 ± 2.1 |

Values are means ± SE. IL-6, interleukin-6.

P ≤ 0.05 versus YE.

Basal Muscle Macrophage Abundance

Skeletal muscle macrophage parameters are also shown in Table 4. The number of CD68+ cells per 100 muscle fibers and CD68+ cell density was not different across the three groups (P > 0.05).

Basal Skeletal Muscle Inflammation

Proinflammatory muscle cytokines are shown in Fig. 1A. Significantly higher expression of IL-6 was noted in the older cohorts combined versus YE (P ≤ 0.05); both LLE and OH likely contributed to this effect, since the expression of IL-6 was very similar between LLE (+114% vs. YE) and OH (+113% vs. YE). LLE exhibited lower expression of IL-1β (−75% vs. OH, P ≤ 0.05). No differences in expression of TNF-α or expression of anti-inflammatory genes (Fig. 2A) were detected across groups.

Fig. 1.

Basal expression (A) and exercise-induced fold-change (B) in expression of proinflammatory cytokines in vastus lateralis skeletal muscle homogenate of young exercisers (YE), lifelong exercisers (LLE), and old healthy (OH). The dashed line at 1.0-fold represents preexercise fold-change for each group, derived from the 2−ΔΔCT calculation (see methods). AU, arbitrary units; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α. *P ≤ 0.05 versus YE, ‡P ≤ 0.05 versus OH, **P ≤ 0.05 versus preexercise.

Fig. 2.

Basal expression (A) and exercise-induced fold-change (B) in expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines in vastus lateralis skeletal muscle homogenate of young exercisers (YE), lifelong exercisers (LLE), and old healthy (OH). The dashed line at 1.0-fold represents preexercise fold-change for each group, derived from the 2−ΔΔCT calculation (see methods). AU, arbitrary units; IL-1Ra, interleukin 1 receptor antagonist; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β. **P ≤ 0.05 versus preexercise.

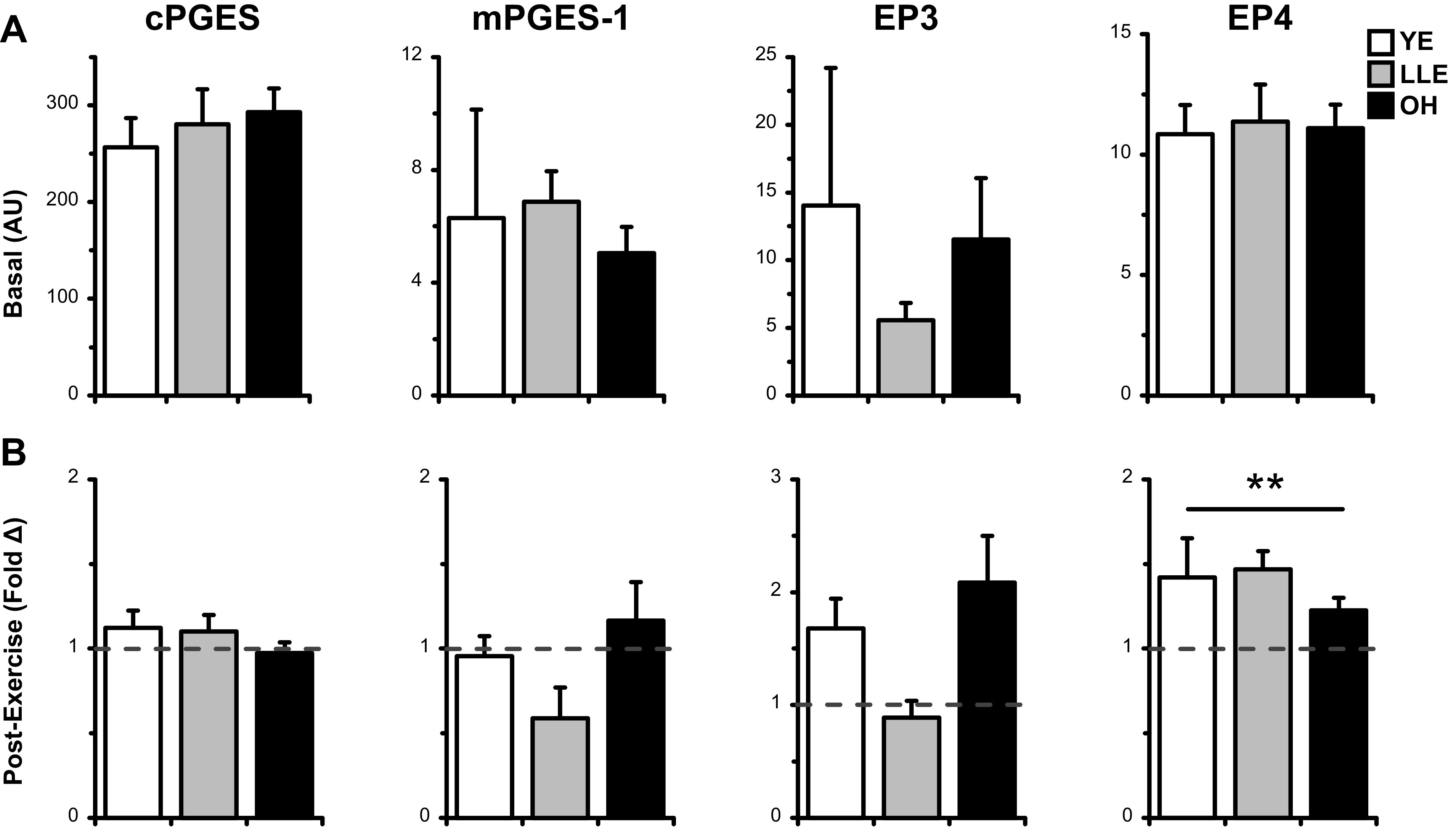

Skeletal muscle cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes are shown in Fig. 3A. Although the older cohorts (LLE and OH) combined exhibited higher expression of COX-1v1 (+70%, P ≤ 0.05 vs. YE), only OH showed elevated COX-1v2 (+92%, P ≤ 0.05 vs. YE), the more prevalent isoform of COX-1 in skeletal muscle (85). COX-2 was not different across the groups, nor was the expression of genes encoding downstream components of the prostaglandin (PG)E2/COX pathway (Fig. 4A). Skeletal muscle signaling factors, including chemokines IL-8 and MCP-1, along with macrophage surface markers CD163 and CD16b, are shown in Fig. 5A. Expression of these factors was not different across the groups at baseline (P > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Basal expression (A) and exercise-induced fold-change (B) in expression of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes in vastus lateralis skeletal muscle homogenate of young exercisers (YE), lifelong exercisers (LLE), and old healthy (OH). The dashed line at 1.0-fold represents preexercise fold-change for each group, derived from the 2−ΔΔCT calculation (see methods). AU, arbitrary units; v1, variant 1; v2, variant 2. *P ≤ 0.05 versus YE.

Fig. 4.

Basal expression (A) and exercise-induced fold-change (B) in expression of PGE2/COX pathway components in in vastus lateralis skeletal muscle homogenate of young exercisers (YE), lifelong exercisers (LLE), and old healthy (OH). The dashed line at 1.0-fold represents preexercise fold-change for each group, derived from the 2−ΔΔCT calculation (see methods). AU, arbitrary units; cPGES, cytosolic prostaglandin E2 synthase; COX, cyclooxygenase enzyme; EP, E-prostanoid receptor; mPGES, microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase. **P ≤ 0.05 versus preexercise.

Fig. 5.

Basal expression (A) and exercise-induced fold-change (B) in expression of chemokines and macrophage surface markers in vastus lateralis skeletal muscle homogenate of young exercisers (YE), lifelong exercisers (LLE), and old healthy (OH). The dashed line at 1.0-fold represents preexercise fold-change for each group, derived from the 2−ΔΔCT calculation (see methods). AU, arbitrary units; CD, cluster of differentiation; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1. *P ≤ 0.05 versus YE, **P ≤ 0.05 versus preexercise.

Effects of Acute Resistance Exercise

Following acute RE, skeletal muscle IL-6 expression (Fig. 1B) was significantly elevated (1.8-fold, P ≤ 0.05), driven by a 2.8-fold increase in YE that was not seen in the older cohorts. Despite this strong effect, post hoc test revealed P = 0.06. In contrast, TNF-α was significantly upregulated in only the older cohorts after exercise (1.5-fold, P ≤ 0.05). Only LLE demonstrated an increase in expression of IL-1β following acute resistance exercise (2.9-fold, P ≤ 0.05).

Expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 2B) was generally unchanged after exercise, with the exception of IL-1Ra (1.7-fold overall, P ≤ 0.05). In the PGE2/COX pathway (Figs. 3B and 4B), COX-2 gene expression had a tendency to increase after acute resistance exercise (1.6-fold overall, P = 0.09), and downstream PGE2 receptor EP4 was significantly upregulated after resistance exercise (1.4-fold overall, P ≤ 0.05). No other components of the PGE2/COX pathway were altered by exercise.

Expression of skeletal muscle intercellular signaling factors was different across the groups after resistance exercise (Fig. 5B). Both aging cohorts demonstrated increased postexercise expression of skeletal muscle IL-8 (1.2-fold vs. 0.8-fold in YE, P ≤ 0.05). Only LLE demonstrated an increase in MCP-1 expression (2.6-fold, P ≤ 0.05), and the overall increase in CD16b expression (2.1-fold, P ≤ 0.05) was largely driven by LLE (2.8-fold, P = 0.08). No changes were seen in CD163 expression after acute exercise.

DISCUSSION

Although we previously reported other health benefits of lifelong aerobic exercise in this cohort (6, 19, 20), this study is the first to examine skeletal muscle inflammation in lifelong exercising women at rest and following an unaccustomed exercise stimulus. Findings suggest that it may be important to consider other modes of exercise throughout the life span (e.g., resistance training, high-intensity interval training, or a combination) for preservation of the inflammatory profile in aging women. Although the effects of aging were subtle rather than dramatic, lifelong aerobic exercise does not appear to protect against age-related changes in inflammation in older women at rest or in response to an unaccustomed loading stimulus. These results contrast with our previous findings in men, and it could be of great interest to understand how sex-specific patterns in basal and postexercise muscle inflammation may reflect and/or contribute to differential aging phenomena between the sexes.

Basal Inflammatory Profile

The overall subtle effects of aging highlight the generally good health of the OH cohort as a reference. Despite differences across study cohorts, circulating inflammatory factors such as CRP and TNF-α are lower in the present study in comparison to reported values in larger studies of inflammaging (2, 11). Thus, it may be reasonable to conclude that the activity status of both the OH and LLE groups is protective against overt subclinical systemic inflammation, while the skeletal muscle environment is differentially affected by aging.

The observed inflammatory burden in skeletal muscle of the older cohorts is a phenomenon well supported by other literature, including IL-6 (41, 42) and components of the PGE2/COX pathway (36). The role of this pathway in the regulation of skeletal muscle mass at rest and after exercise is highlighted in studies showing a beneficial effect of drugs that inhibit COX (76, 79, 80). In general, the effects of aging were not reversed or slowed by lifelong exercise in women. The lower expression of muscle IL-1β in LLE women suggests a potential compensatory effect, but no other genes followed this pattern: even anti-inflammatory genes that were upregulated by lifelong aerobic exercise in men, such as IL-10, TGF-β, and EP4 (33), were not different in LLE women.

Previously, we reported that in LLE women, skeletal muscle metabolic parameters such as mitochondrial enzyme activity and muscle capillarization were completely preserved (20), but age-related declines in cardiovascular fitness and skeletal muscle mass were still apparent (6, 20). Of particular note, lifelong exercise partially attenuated muscle mass decline in men, but not in women (6), even though the women in the present study reported similar exercise training histories (Table 2) as men in our previous report (20). Furthermore, the difference in absolute in LLE relative to OH women (+37%) was nearly identical to that between LLE and OH men in our previous report (+38%), highlighting similar aerobic fitness in LLE groups compared with untrained counterparts. Thus, while it is unlikely that overall lifetime dose of aerobic exercise is the primary driver for the apparent sex difference, these discrepancies may be the result of an underlying biological difference.

Others have investigated the apparently divergent processes of skeletal muscle aging in men and women (62, 63). Several important considerations may be involved in these apparent sex differences. First, the hormonal milieu is different between men and women and within each sex across the life span (25), as our previous findings have corroborated (20). The anti-inflammatory (31, 47, 82) and potentially proanabolic (22, 23) benefits of estrogen are lost after menopause that has been suggested as a potential contributor to skeletal muscle deficits later in life (47, 84). Others have reported that hormonal changes associated with menopause lead to endothelial dysfunction, regardless of premenopausal physical activity level (65). It is possible that skeletal muscle undergoes similar changes. However, based on our prior evidence that the metabolic profile (including capillarization) of muscle in LLE women is well-preserved (20), it is reasonable to speculate that muscle health may be more adaptable in LLE than in untrained women, contingent on the proper exercise dose.

Skeletal muscle fiber type distribution may play a role in the homeostatic balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory factors: we (36) and others (55) have previously shown differential abundance of inflammatory factors such as muscle cytokines and prostaglandin pathway components in type I (slow, aerobic) versus type II (fast, glycolytic) muscle fibers. It is possible that the differential inflammatory environment in the muscle of aging women versus men is a product of differential capacity to produce and secrete these factors due to sex differences in fiber type distribution (63, 70) or divergence in the muscle aging process (63). Finally, it is possible that both environmental and intrinsic influences begin to impact gene skeletal muscle at a younger age than we have examined herein, as previous studies have suggested heightened muscle inflammatory burden in a group as young as 60 yr (42). Future investigations may seek to elucidate mechanisms underlying inflammation in middle-aged women to optimize exercise regimens that might prevent the onset of chronic basal inflammation in older age.

Inflammatory Response to Acute Exercise

We previously outlined the study rationale for introducing a resistance exercise bout to an aerobically trained cohort (33). Briefly, we reasoned that this unaccustomed exercise would both provide a novel stimulus to the skeletal muscle of all three study groups and also provide insight into acute mechanisms underlying long-term hypertrophic potential. In LLE men (33), we reported a generally preserved response to this stimulus, whereas old untrained men exhibited an altered, more proinflammatory response (summarized in Table 5). Presently, the overall response to acute exercise was altered by aging in women regardless of training status. Nevertheless, we noted several differential responses in the LLE cohort that may warrant continued investigation.

Table 5.

Key differences in muscle gene expression following resistance exercise

| Women |

Men |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YE | LLE | OH | YE | LLE | OH | |

| IL-6 | ↑ | |||||

| TNF-α | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | |||

| IL-1β | ↑ | |||||

| IL-1Ra | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | |||

| TGF-β | ↑ | |||||

| COX-2 | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | |||

| cPGES | ||||||

| EP3 | ↑ | |||||

| EP4 | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| IL-8 | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | |||

| MCP-1 | ↑ | |||||

| CD16b | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| CD163 | ||||||

Women and men underwent an identical exercise stimulus; muscle gene expression in men is reported in previous work from our group (33). Arrow (↑) denotes significantly (P ≤ 0.05) increased gene expression postexercise versus preexercise. COX-2, cyclooxygenase enzyme-2; cPGES, cytosolic prostaglandin E2 synthase; EP, E-prostanoid receptor; IL-6, interleukin-6; IL-1Ra, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist; mPGES, microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β.

Increased postexercise expression of IL-6 was seen in YE, as is frequently documented in response to acute resistance exercise in healthy young adults (15, 38, 41, 81). Both older groups displayed elevated IL-6 expression at baseline but appeared to have a blunted or (perhaps) delayed response to acute resistance exercise. IL-6 plays an important metabolic role in skeletal muscle signaling (24, 88), including facilitating progression from the pro- to anti-inflammatory phases of the acute response to exercise (51, 71). The observed difference between the young and old cohorts [as others have shown with different exercise stimuli (27, 73)] may indicate that older muscle is more likely to remain in an exercise-induced proinflammatory state longer than young muscle. Increased expression of TNF-α and IL-8 in both older groups suggests a more stress-related response to the resistance exercise challenge, as we have previously shown in skeletal muscle of old healthy nonexercising men at the same time point (33). This salient difference illustrates that lifelong aerobic exercise was apparently inadequate to preserve the acute response to resistance exercise in aging women.

Despite this, the postexercise myokine milieu was different between the two older groups, with expression of several genes exclusively (e.g., IL-1β, MCP-1) or predominantly (e.g., CD16b) responsive to exercise in LLE. Both MCP-1 and CD16b are involved with intercellular communication: the former as a chemoattractant for infiltrating monocytes (32, 39) and the latter as a macrophage surface receptor upstream of cytokine production (31). Importantly, we did not detect any differences across the groups with regard to basal macrophage abundance (Table 4), and it is not likely that additional macrophages were recruited between the preexercise and 4 h time point, since this process typically requires days (40, 49). Therefore, differences in CD16b more likely reflect a response to exercise in the resident macrophages. Increased CD16b expression is seen in naïve skeletal muscle following an unaccustomed bout of exercise (17), and data from cell culture models indicate that low estrogen may promote CD16b activity and subsequent cytokine production (31). Along with heightened signaling through IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-8, and MCP-1, LLE muscle may be able to compensate for the dysregulated response to acute resistance exercise with a heightened capacity to recruit macrophages following an insult. Indeed, others have shown impaired macrophage communication capacity with advancing age (56), and it is possible that lifelong aerobic exercise protects against age-related macrophage dysregulation. Given the study design using only a single postexercise time point, it remains unknown whether skeletal muscle inflammation might be resolved more quickly in the muscle of highly trained older women. This may be elucidated in future investigations with larger sample sizes and/or muscle biopsies at additional postexercise time points.

No major changes were seen in the activity of the PGE2/COX pathway following exercise. However, the present data support our previous findings that COX-2 and EP4 gene expression are upregulated following acute resistance exercise (33, 85). Although differential patterns are beginning to emerge for postexercise expression of mPGES-1 and EP3 (both doubled in OH vs. LLE after acute RE), these patterns did not attain statistical significance. Thus, the apparent benefits of COX-inhibitors in increasing exercise-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy (76, 79, 80) may be best understood by examining the PGE2/COX pathway at additional postexercise time points. Supporting this, PGE2 is heightened in the muscle at 24 h postexercise (77).

Although not a primary focus of this investigation, the response to acute resistance exercise was not identical between young women and young men (Table 5), as others have also demonstrated (1, 48). Presently, expression of both IL-6 and IL-1Ra was elevated in skeletal muscle of young women after acute exercise, whereas expression was unchanged in young men (33). Certainly, additional factors in a larger sample size would need to be considered to understand whether the observed patterns point to sex differences in postexercise inflammatory burden, energy metabolism (51), and/or other key molecular responses. Future studies investigating the skeletal muscle transcriptome and other molecular phenotypes (e.g., proteome, methylome) in response to exercise are likely to provide valuable insight (54, 64).

Limitations and Future Directions

A limitation of this study is the smaller sample size in contrast to a parallel investigation in a cohort of men (n = 41 total) (33). A consequence of societal norms and opportunities for men and women during the 1960s and 1970s is that the popularity of structured exercise as a hobby for women lagged behind that for men; thus, the available population is considerably smaller. Furthermore, while a potential study limitation is that we did not include a young untrained group, it is unlikely that young adults considered sedentary by today’s standards appropriately represent either of the older cohorts during their youth. Nevertheless, comparison of lifelong exercisers and old healthy adults to recreationally active, untrained young adults might provide insight into whether an individual’s age, sex, training status, and/or duration of training differentially impact muscle inflammatory gene expression at rest and after exercise. This is especially critical in women, given the comparative dearth of research examining muscle health.

The unique group of women in the present study provides novel insight into potential mechanisms underlying sex differences in aging muscle. Future investigations might be able to leverage an increasingly large population of lifelong exercising women to establish whether patterns seen in the present study are upheld. For instance, basal expression of both IL-10 and IL-1Ra exhibited a hierarchical pattern such that YE < LLE < OH, but we were not able to detect significant differences across the groups. Additionally, it could be meaningful to establish whether large fold-changes such as the 2.9-fold increase in IL-4 expression in the LLE cohort are upheld in a study with higher statistical power.

This investigation aids in laying the foundation for future studies into sex-dependent mechanisms of muscle aging and the potential of lifelong exercise to offset these effects. Although we observed potential differential capacity for signaling with macrophages based on gene expression in LLE women, it may be important to consider other mechanisms of communication in the response to exercise, for example, exosome-like vesicles (8, 10). Furthermore, continued investigation is needed to understand the optimal strategy for preserving the response to exercise with aging in women, which may include alternative modes of exercise (e.g., high-intensity interval or resistance training) and/or management of hormonal imbalances or inflammation using pharmaceutical treatments.

Conclusions

Although the beneficial effects of lifelong exercise are becoming increasingly apparent (6, 19, 20, 52), it is imperative to prioritize the study of both sexes to fully optimize exercise recommendations for aging women and men. In this study of three cohorts of women, we observed modest age-related increases in skeletal muscle and circulating inflammation, most of which were not influenced by lifelong aerobic exercise. Furthermore, following an acute bout of unaccustomed exercise, skeletal muscle gene expression indicates a proinflammatory response in the muscle of older women, regardless of training status. Whether lifelong trained skeletal muscle is able to facilitate quicker resolution of this inflammation via intercellular signaling remains a possibility that warrants continued investigation. Overall, this study highlights the need for a better understanding of skeletal muscle physiology in aging women to guide exercise prescription, maintain physical function, and preserve quality of life with advancing age.

GRANTS

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant AG038576.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.M.L., R.K.P., B.J., U.R., S.W.T., and T.A.T. conceived and designed research; K.M.L., R.K.P., B.J., U.R., S.W.T., and T.A.T. performed experiments; K.M.L., R.K.P., B.J., and T.A.T. analyzed data; K.M.L., R.K.P., B.J., U.R., S.W.T., and T.A.T. interpreted results of experiments; K.M.L., R.K.P., and T.A.T. prepared figures; K.M.L., R.K.P., and T.A.T. drafted manuscript; K.M.L., R.K.P., B.J., U.R., S.W.T., and T.A.T. edited and revised manuscript; K.M.L., R.K.P., B.J., U.R., S.W.T., and T.A.T. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all study participants as well as staff and graduate students that assisted with this project. In particular, we acknowledge Andrew M. Jones for assistance with macrophage data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbasi A, de Paula Vieira R, Bischof F, Walter M, Movassaghi M, Berchtold NC, Niess AM, Cotman CW, Northoff H. Sex-specific variation in signaling pathways and gene expression patterns in human leukocytes in response to endotoxin and exercise. J Neuroinflammation 13: 289, 2016. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0758-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Álvarez-Rodríguez L, López-Hoyos M, Muñoz-Cacho P, Martínez-Taboada VM. Aging is associated with circulating cytokine dysregulation. Cell Immunol 273: 124–132, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bamman MM, Ferrando AA, Evans RP, Stec MJ, Kelly NA, Gruenwald JM, Corrick KL, Trump JR, Singh JA. Muscle inflammation susceptibility: a prognostic index of recovery potential after hip arthroplasty? Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 308: E670–E679, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00576.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergström J Muscle electrolytes in man. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 14: 1–110, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biolo G, Maggi SP, Williams BD, Tipton KD, Wolfe RR. Increased rates of muscle protein turnover and amino acid transport after resistance exercise in humans. Am J Physiol 268: E514–E520, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.268.3.E514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambers TL, Burnett TR, Raue U, Lee GA, Finch WH, Graham BM, Trappe TA, Trappe S. Skeletal muscle size, function, and adiposity with lifelong aerobic exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 128: 368–378, 2020. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00426.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chazaud B Inflammation during skeletal muscle regeneration and tissue remodeling: application to exercise-induced muscle damage management. Immunol Cell Biol 94: 140–145, 2016. doi: 10.1038/icb.2015.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidsen PK, Gallagher IJ, Hartman JW, Tarnopolsky MA, Dela F, Helge JW, Timmons JA, Phillips SM. High responders to resistance exercise training demonstrate differential regulation of skeletal muscle microRNA expression. J Appl Physiol (1985) 110: 309–317, 2011. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00901.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derreberry TM, Holroyd S. Dementia in women. Psychiatr Clin North Am 40: 299–307, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drummond MJ, McCarthy JJ, Fry CS, Esser KA, Rasmussen BB. Aging differentially affects human skeletal muscle microRNA expression at rest and after an anabolic stimulus of resistance exercise and essential amino acids. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E1333–E1340, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90562.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrucci L, Corsi A, Lauretani F, Bandinelli S, Bartali B, Taub DD, Guralnik JM, Longo DL. The origins of age-related proinflammatory state. Blood 105: 2294–2299, 2005. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrucci L, Penninx BW, Volpato S, Harris TB, Bandeen-Roche K, Balfour J, Leveille SG, Fried LP, Md JM. Change in muscle strength explains accelerated decline of physical function in older women with high interleukin-6 serum levels. J Am Geriatr Soc 50: 1947–1954, 2002. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher DW, Bennett DA, Dong H. Sexual dimorphism in predisposition to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 70: 308–324, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freedman VA, Wolf DA, Spillman BC. Disability-free life expectancy over 30 years: a growing female disadvantage in the US population. Am J Public Health 106: 1079–1085, 2016. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gjevestad GO, Hamarsland H, Raastad T, Ottestad I, Christensen JJ, Eckardt K, Drevon CA, Biong AS, Ulven SM, Holven KB. Gene expression is differentially regulated in skeletal muscle and circulating immune cells in response to an acute bout of high-load strength exercise. Genes Nutr 12: 8, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12263-017-0556-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gordon EH, Peel NM, Samanta M, Theou O, Howlett SE, Hubbard RE. Sex differences in frailty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp Gerontol 89: 30–40, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2016.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon PM, Liu D, Sartor MA, IglayReger HB, Pistilli EE, Gutmann L, Nader GA, Hoffman EP. Resistance exercise training influences skeletal muscle immune activation: a microarray analysis. J Appl Physiol (1985) 112: 443–453, 2012. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00860.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greig CA, Gray C, Rankin D, Young A, Mann V, Noble B, Atherton PJ. Blunting of adaptive responses to resistance exercise training in women over 75y. Exp Gerontol 46: 884–890, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gries KJ, Minchev K, Raue U, Grosicki GJ, Begue G, Finch WH, Graham B, Trappe TA, Trappe S. Single-muscle fiber contractile properties in lifelong aerobic exercising women. J Appl Physiol (1985) 127: 1710–1719, 2019. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00459.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gries KJ, Raue U, Perkins RK, Lavin KM, Overstreet BS, D’Acquisto LJ, Graham B, Finch WH, Kaminsky LA, Trappe TA, Trappe S. Cardiovascular and skeletal muscle health with lifelong exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 125: 1636–1645, 2018. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00174.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hackney AC, Kallman AL, Ağgön E. Female sex hormones and the recovery from exercise: Menstrual cycle phase affects responses. Biomed Hum Kinetics 11: 87–89, 2019. doi: 10.2478/bhk-2019-0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansen M Female hormones: do they influence muscle and tendon protein metabolism? Proc Nutr Soc 77: 32–41, 2018. doi: 10.1017/S0029665117001951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansen M, Kjaer M. Influence of sex and estrogen on musculotendinous protein turnover at rest and after exercise. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 42: 183–192, 2014. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helge JW, Stallknecht B, Pedersen BK, Galbo H, Kiens B, Richter EA. The effect of graded exercise on IL-6 release and glucose uptake in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol 546: 299–305, 2003. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.030437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horstman AM, Dillon EL, Urban RJ, Sheffield-Moore M. The role of androgens and estrogens on healthy aging and longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 67: 1140–1152, 2012. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jemiolo B, Trappe S. Single muscle fiber gene expression in human skeletal muscle: validation of internal control with exercise. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 320: 1043–1050, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jozsi AC, Dupont-Versteegden EE, Taylor-Jones JM, Evans WJ, Trappe TA, Campbell WW, Peterson CA. Aged human muscle demonstrates an altered gene expression profile consistent with an impaired response to exercise. Mech Ageing Dev 120: 45–56, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(00)00178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kojima G Frailty as a predictor of disabilities among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil 39: 1897–1908, 2017. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1212282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kojima G Frailty as a predictor of nursing home placement among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Geriatr Phys Ther 41: 42–48, 2018. doi: 10.1519/JPT.0000000000000097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Konopka AR, Douglass MD, Kaminsky LA, Jemiolo B, Trappe TA, Trappe S, Harber MP. Molecular adaptations to aerobic exercise training in skeletal muscle of older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 65A: 1201–1207, 2010. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kramer PR, Kramer SF, Guan G. 17 Beta-estradiol regulates cytokine release through modulation of CD16 expression in monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. Arthritis Rheum 50: 1967–1975, 2004. doi: 10.1002/art.20309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurihara T, Warr G, Loy J, Bravo R. Defects in macrophage recruitment and host defense in mice lacking the CCR2 chemokine receptor. J Exp Med 186: 1757–1762, 1997. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lavin KM, Perkins RK, Jemiolo B, Raue U, Trappe SW, Trappe TA. Effects of aging and lifelong aerobic exercise on basal and exercise-induced inflammation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 128: 87–99, 2020. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00495.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavin KM, Roberts BM, Fry CS, Moro T, Rasmussen BB, Bamman MM. The importance of resistance exercise training to combat neuromuscular aging. Physiology (Bethesda) 34: 112–122, 2019. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00044.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu P, Hao Q, Hai S, Wang H, Cao L, Dong B. Sarcopenia as a predictor of all-cause mortality among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 103: 16–22, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu SZ, Jemiolo B, Lavin KM, Lester BE, Trappe SW, Trappe TA. Prostaglandin E2/cyclooxygenase pathway in human skeletal muscle: influence of muscle fiber type and age. J Appl Physiol (1985) 120: 546–551, 2016. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00396.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Louis E, Raue U, Yang Y, Jemiolo B, Trappe S. Time course of proteolytic, cytokine, and myostatin gene expression after acute exercise in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985) 103: 1744–1751, 2007. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00679.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu H, Huang D, Ransohoff RM, Zhou L. Acute skeletal muscle injury: CCL2 expression by both monocytes and injured muscle is required for repair. FASEB J 25: 3344–3355, 2011. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-178939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malm C, Nyberg P, Engstrom M, Sjodin B, Lenkei R, Ekblom B, Lundberg I. Immunological changes in human skeletal muscle and blood after eccentric exercise and multiple biopsies. J Physiol 529: 243–262, 2000. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKay BR, Ogborn DI, Baker JM, Toth KG, Tarnopolsky MA, Parise G. Elevated SOCS3 and altered IL-6 signaling is associated with age-related human muscle stem cell dysfunction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 304: C717–C728, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00305.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merritt EK, Stec MJ, Thalacker-Mercer A, Windham ST, Cross JM, Shelley DP, Craig Tuggle S, Kosek DJ, Kim JS, Bamman MM. Heightened muscle inflammation susceptibility may impair regenerative capacity in aging humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 115: 937–948, 2013. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00019.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mikkelsen UR, Agergaard J, Couppé C, Grosset JF, Karlsen A, Magnusson SP, Schjerling P, Kjaer M, Mackey AL. Skeletal muscle morphology and regulatory signalling in endurance-trained and sedentary individuals: The influence of ageing. Exp Gerontol 93: 54–67, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Minuzzi LG, Rama L, Bishop NC, Rosado F, Martinho A, Paiva A, Teixeira AM. Lifelong training improves anti-inflammatory environment and maintains the number of regulatory T cells in masters athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol 117: 1131–1140, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00421-017-3600-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Minuzzi LG, Rama L, Chupel MU, Rosado F, Dos Santos JV, Simpson R, Martinho A, Paiva A, Teixeira AM. Effects of lifelong training on senescence and mobilization of T lymphocytes in response to acute exercise. Exerc Immunol Rev 24: 72–84, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murach K, Raue U, Wilkerson B, Minchev K, Jemiolo B, Bagley J, Luden N, Trappe S. Single muscle fiber gene expression with run taper. PLoS One 9: e108547, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nedergaard A, Henriksen K, Karsdal MA, Christiansen C. Menopause, estrogens and frailty. Gynecol Endocrinol 29: 418–423, 2013. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2012.754879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Northoff H, Symons S, Zieker D, Schaible EV, Schäfer K, Thoma S, Löffler M, Abbasi A, Simon P, Niess AM, Fehrenbach E. Gender- and menstrual phase dependent regulation of inflammatory gene expression in response to aerobic exercise. Exerc Immunol Rev 14: 86–103, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paulsen G, Crameri R, Benestad HB, Fjeld JG, Mørkrid L, Hallén J, Raastad T. Time course of leukocyte accumulation in human muscle after eccentric exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42: 75–85, 2010. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181ac7adb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Payne CF Aging in the Americas: disability-free life expectancy among adults aged 65 and older in the United States, Costa Rica, Mexico, and Puerto Rico. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 73: 337–348, 2018. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscle as an endocrine organ: focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiol Rev 88: 1379–1406, 2008. doi: 10.1152/physrev.90100.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perkins RK, Lavin KM, Raue U, Jemiolo B, Trappe SW, Trappe TA. Effects of aging and lifelong aerobic exercise on expression of innate immune components in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985). First published September 24, 2020. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00615.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phillips SM, Tipton KD, Aarsland A, Wolf SE, Wolfe RR. Mixed muscle protein synthesis and breakdown after resistance exercise in humans. Am J Physiol 273: E99–E107, 1997. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.1.E99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pillon NJ, Gabriel BM, Dollet L, Smith JAB, Sardón Puig L, Botella J, Bishop DJ, Krook A, Zierath JR. Transcriptomic profiling of skeletal muscle adaptations to exercise and inactivity. Nat Commun 11: 470, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13869-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Plomgaard P, Penkowa M, Pedersen BK. Fiber type specific expression of TNF-alpha, IL-6 and IL-18 in human skeletal muscles. Exerc Immunol Rev 11: 53–63, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Przybyla B, Gurley C, Harvey JF, Bearden E, Kortebein P, Evans WJ, Sullivan DH, Peterson CA, Dennis RA. Aging alters macrophage properties in human skeletal muscle both at rest and in response to acute resistance exercise. Exp Gerontol 41: 320–327, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Raue U, Jemiolo B, Yang Y, Trappe S. TWEAK-Fn14 pathway activation after exercise in human skeletal muscle: insights from two exercise modes and a time course investigation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 118: 569–578, 2015. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00759.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raue U, Slivka D, Jemiolo B, Hollon C, Trappe S. Myogenic gene expression at rest and after a bout of resistance exercise in young (18-30 yr) and old (80-89 yr) women. J Appl Physiol (1985) 101: 53–59, 2006. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01616.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Raue U, Slivka D, Jemiolo B, Hollon C, Trappe S. Proteolytic gene expression differs at rest and after resistance exercise between young and old women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 62: 1407–1412, 2007. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.12.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Raue U, Slivka D, Minchev K, Trappe S. Improvements in whole muscle and myocellular function are limited with high-intensity resistance training in octogenarian women. J Appl Physiol (1985) 106: 1611–1617, 2009. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91587.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Raue U, Trappe TA, Estrem ST, Qian HR, Helvering LM, Smith RC, Trappe S. Transcriptome signature of resistance exercise adaptations: mixed muscle and fiber type specific profiles in young and old adults. J Appl Physiol (1985) 112: 1625–1636, 2012. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00435.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Riddle ES, Bender EL, Thalacker-Mercer AE. Expansion capacity of human muscle progenitor cells differs by age, sex, and metabolic fuel preference. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 315: C643–C652, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00135.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roberts BM, Lavin KM, Many GM, Thalacker-Mercer A, Merritt EK, Bickel CS, Mayhew DL, Tuggle SC, Cross JM, Kosek DJ, Petrella JK, Brown CJ, Hunter GR, Windham ST, Allman RM, Bamman MM. Human neuromuscular aging: Sex differences revealed at the myocellular level. Exp Gerontol 106: 116–124, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2018.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sanford JA, Nogiec CD, Lindholm ME, Adkins JN, Amar D, Dasari S, Drugan JK, Fernández FM, Radom-Aizik S, Schenk S, Snyder MP, Tracy RP, Vanderboom P, Trappe S, Walsh MJ, Adkins JN, Amar D, Dasari S, Drugan JK, Evans CR, Fernandez FM, Li Y, Lindholm ME, Nogiec CD, Radom-Aizik S, Sanford JA, Schenk S, Snyder MP, Tomlinson L, Tracy RP, Trappe S, Vanderboom P, Walsh MJ, Lee Alekel D, Bekirov I, Boyce AT, Boyington J, Fleg JL, Joseph LJO, Laughlin MR, Maruvada P, Morris SA, McGowan JA, Nierras C, Pai V, Peterson C, Ramos E, Roary MC, Williams JP, Xia A, Cornell E, Rooney J, Miller ME, Ambrosius WT, Rushing S, Stowe CL, Jack Rejeski W, Nicklas BJ, Pahor M, Lu C, Trappe T, Chambers T, Raue U, Lester B, Bergman BC, Bessesen DH, Jankowski CM, Kohrt WM, Melanson EL, Moreau KL, Schauer IE, Schwartz RS, Kraus WE, Slentz CA, Huffman KM, Johnson JL, Willis LH, Kelly L, Houmard JA, Dubis G, Broskey N, Goodpaster BH, Sparks LM, Coen PM, Cooper DM, Haddad F, Rankinen T, Ravussin E, Johannsen N, Harris M, Jakicic JM, Newman AB, Forman DD, Kershaw E, Rogers RJ, Nindl BC, Page LC, Stefanovic-Racic M, Barr SL, Rasmussen BB, Moro T, Paddon-Jones D, Volpi E, Spratt H, Musi N, Espinoza S, Patel D, Serra M, Gelfond J, Burns A, Bamman MM, Buford TW, Cutter GR, Bodine SC, Esser K, Farrar RP, Goodyear LJ, Hirshman MF, Albertson BG, Qian W-J, Piehowski P, Gritsenko MA, Monore ME, Petyuk VA, McDermott JE, Hansen JN, Hutchison C, Moore S, Gaul DA, Clish CB, Avila-Pacheco J, Dennis C, Kellis M, Carr S, Jean-Beltran PM, Keshishian H, Mani DR, Clauser K, Krug K, Mundorff C, Pearce C, Ivanova AA, Ortlund EA, Maner-Smith K, Uppal K, Zhang T, Sealfon SC, Zaslavsky E, Nair V, Li SD, Jain N, Ge YC, Sun Y, Nudelman G, Ruf-zamojski F, Smith G, Pincas N, Rubenstein A, Anne Amper M, Seenarine N, Lappalainen T, Lanza IR, Sreekumaran Nair K, Klaus K, Montgomery SB, Smith KS, Gay NR, Zhao B, Hung C-J, Zebarjadi N, Balliu B, Fresard L, Burant CF, Li JZ, Kachman M, Soni T, Raskind AB, Gerszten R, Robbins J, Ilkayeva O, Muehlbauer MJ, Newgard CB, Ashley EA, Wheeler MT, Jimenez-Morales D, Raja A, Dalton KP, Zhen J, Suk Kim Y, Christle JW, Marwaha S, Chin ET, Hershman SG, Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Rivas MA; Molecular Transducers of Physical Activity Consortium . Molecular Transducers of Physical Activity Consortium (MoTrPAC): mapping the dynamic responses to exercise. Cell 181: 1464–1474, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Santos-Parker JR, Strahler TR, Vorwald VM, Pierce GL, Seals DR. Habitual aerobic exercise does not protect against micro- or macrovascular endothelial dysfunction in healthy estrogen-deficient postmenopausal women. J Appl Physiol (1985) 122: 11–19, 2017. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00732.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schaap LA, Pluijm SM, Deeg DJ, Harris TB, Kritchevsky SB, Newman AB, Colbert LH, Pahor M, Rubin SM, Tylavsky FA, Visser M; Health ABC Study . Higher inflammatory marker levels in older persons: associations with 5-year change in muscle mass and muscle strength. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64A: 1183–1189, 2009. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Slivka D, Raue U, Hollon C, Minchev K, Trappe S. Single muscle fiber adaptations to resistance training in old (>80 yr) men: evidence for limited skeletal muscle plasticity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R273–R280, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00093.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Srikanth VK, Fryer JL, Zhai G, Winzenberg TM, Hosmer D, Jones G. A meta-analysis of sex differences prevalence, incidence and severity of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 13: 769–781, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Standley RA, Liu SZ, Jemiolo B, Trappe SW, Trappe TA. Prostaglandin E2 induces transcription of skeletal muscle mass regulators interleukin-6 and muscle RING finger-1 in humans. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 88: 361–364, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Staron RS, Hagerman FC, Hikida RS, Murray TF, Hostler DP, Crill MT, Ragg KE, Toma K. Fiber type composition of the vastus lateralis muscle of young men and women. J Histochem Cytochem 48: 623–629, 2000. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Steensberg A, Fischer CP, Keller C, Møller K, Pedersen BK. IL-6 enhances plasma IL-1ra, IL-10, and cortisol in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 285: E433–E437, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00074.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thalacker-Mercer A, Stec M, Cui X, Cross J, Windham S, Bamman M. Cluster analysis reveals differential transcript profiles associated with resistance training-induced human skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Physiol Genomics 45: 499–507, 2013. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00167.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Toft AD, Jensen LB, Bruunsgaard H, Ibfelt T, Halkjaer-Kristensen J, Febbraio M, Pedersen BK. Cytokine response to eccentric exercise in young and elderly humans. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283: C289–C295, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00583.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Trappe S, Godard M, Gallagher P, Carroll C, Rowden G, Porter D. Resistance training improves single muscle fiber contractile function in older women. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C398–C406, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.2.C398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Trappe S, Williamson D, Godard M, Porter D, Rowden G, Costill D. Effect of resistance training on single muscle fiber contractile function in older men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 89: 143–152, 2000. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Trappe TA, Carroll CC, Dickinson JM, LeMoine JK, Haus JM, Sullivan BE, Lee JD, Jemiolo B, Weinheimer EM, Hollon CJ. Influence of acetaminophen and ibuprofen on skeletal muscle adaptations to resistance exercise in older adults. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300: R655–R662, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00611.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Trappe TA, Fluckey JD, White F, Lambert CP, Evans WJ. Skeletal muscle PGF(2)(alpha) and PGE(2) in response to eccentric resistance exercise: influence of ibuprofen acetaminophen. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86: 5067–5070, 2001. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Trappe TA, Liu SZ. Effects of prostaglandins and COX-inhibiting drugs on skeletal muscle adaptations to exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 115: 909–919, 2013. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00061.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Trappe TA, Ratchford SM, Brower BE, Liu SZ, Lavin KM, Carroll CC, Jemiolo B, Trappe SW. COX inhibitor influence on skeletal muscle fiber size and metabolic adaptations to resistance exercise in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 71: 1289–1294, 2016. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Trappe TA, Standley RA, Jemiolo B, Carroll CC, Trappe SW. Prostaglandin and myokine involvement in the cyclooxygenase-inhibiting drug enhancement of skeletal muscle adaptations to resistance exercise in older adults. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 304: R198–R205, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00245.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vella L, Markworth JF, Peake JM, Snow RJ, Cameron-Smith D, Russell AP. Ibuprofen supplementation and its effects on NF-κB activation in skeletal muscle following resistance exercise. Physiol Rep 2: e12172, 2014. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Villa A, Rizzi N, Vegeto E, Ciana P, Maggi A. Estrogen accelerates the resolution of inflammation in macrophagic cells. Sci Rep 5: 15224, 2015. doi: 10.1038/srep15224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Visser M, Pahor M, Taaffe DR, Goodpaster BH, Simonsick EM, Newman AB, Nevitt M, Harris TB. Relationship of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha with muscle mass and muscle strength in elderly men and women: the Health ABC Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 57: M326–M332, 2002. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.5.M326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vitale G, Cesari M, Mari D. Aging of the endocrine system and its potential impact on sarcopenia. Eur J Intern Med 35: 10–15, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Weinheimer EM, Jemiolo B, Carroll CC, Harber MP, Haus JM, Burd NA, LeMoine JK, Trappe SW, Trappe TA. Resistance exercise and cyclooxygenase (COX) expression in human skeletal muscle: implications for COX-inhibiting drugs and protein synthesis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R2241–R2248, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00718.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Westerman S, Wenger NK. Women and heart disease, the underrecognized burden: sex differences, biases, and unmet clinical and research challenges. Clin Sci (Lond) 130: 551–563, 2016. doi: 10.1042/CS20150586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Williamson DL, Gallagher PM, Carroll CC, Raue U, Trappe SW. Reduction in hybrid single muscle fiber proportions with resistance training in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 91: 1955–1961, 2001. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.5.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wolsk E, Mygind H, Grøndahl TS, Pedersen BK, van Hall G. IL-6 selectively stimulates fat metabolism in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 299: E832–E840, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00328.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang Y, Creer A, Jemiolo B, Trappe S. Time course of myogenic and metabolic gene expression in response to acute exercise in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985) 98: 1745–1752, 2005. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01185.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]