Abstract

Diabetes is a serious threat to global health and among the top 10 causes of death, with nearly half a billion people living with it worldwide. Treating patients with diabetes tend to become more challenging due to the progressive nature of the disease. The role and benefits of combination therapies for the management of type 2 diabetes are well-documented, while the comparative safety and efficacy among the different combination options have not been elucidated. We aimed to systematically synthesize the evidence on the comparative cardiovascular safety and efficacy of combination therapy with metformin-sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors versus metformin-sulfonylureas in patients with type 2 diabetes. We searched MEDLINE-PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and ClinicalTrials.gov up to 15 August 2019 without restriction in the year of publication. We included randomized controlled trials of patients with type 2 diabetes who were on metformin-sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors or metformin-sulphonylureas combination therapy at least for a year. The primary endpoints were all-cause mortality and serious adverse events, and the secondary endpoints were cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, hypoglycemia, and changes in glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), body weight, fasting plasma glucose, blood pressure, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. We used a random-effects meta-analysis model to estimate mean differences for continuous outcomes and risk ratio for dichotomous outcomes. We followed PICOS description model for defining eligibility and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 guidelines for reporting results. Of 3,190 citations, we included nine trials involving 10,974 participants. The pooled analysis showed no significant difference in all-cause mortality (risk ration [RR] = 0.93, 95% CI [0.52, 1.67]), serious adverse events (RR = 0.96, 95% CI [0.79, 1.17]) and adverse events (RR = 1.00, 95% CI [0.99, 1.02]) between the two, but in hypoglycemia (RR = 0.13, 95% CI [0.10, 0.17], P < 0.001). Participants taking metformin-sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors showed a significantly greater reduction in HbA1c (mean difference [MD] = − 0.10%, 95% CI [− 0.17, − 0.03], body weight (MD = − 4.57 kg, 95% CI [− 4.74, − 4.39], systolic blood pressure (MD = − 4.77 mmHg, 95% CI [− 5.39, − 4.16]), diastolic blood pressure (MD = − 2.07 mmHg, 95% CI [− 2.74, − 1.40], and fasting plasma glucose (MD = − 0.55 mmol/L, 95% CI [− 0.69, − 0.41]), p < 0.001. Combination therapy of metformin and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors is a safe and efficacious alternative to combination therapy of metformin and sulphonylureas for patients with type 2 diabetes who are at risk of cardiovascular comorbidity. However, there remains a need for additional long-term randomized controlled trials as available studies are very limited and heterogeneous.

Subject terms: Cardiology, Endocrinology, Medical research

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the top ten causes of death and one of the fastest-growing health problems of the twenty-first century, with 463 million people living with it worldwide in 2019 and this number estimated to be 700 million by 20451. The global direct health expenditure on diabetes mellitus in 2019 was estimated at US$ 760 billion and is expected to increase to a projected US$ 845 billion by 20452. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the most common and complex form of the disease and accounts for more than 90% of the estimated cases of diabetes, impacting the life expectancy, quality of life, and health of an individual1,3. Yet, there is no cure for T2DM, while its prevalence is largely increasing, with increased risk of complications including diabetic retinopathy, neuropathy, kidney damage, and microvascular and cardiovascular complications4–7. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a common complication and a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with T2DM8,9.

Despite the introduction of new medications, treating patients with diabetes tend to become more challenging due to the progressive nature of the disease10–14. The American Diabetes Association recommends lifestyle interventions (exercise, healthy eating, smoking cessation, and weight reduction) as the first step in treating newly diagnosed T2DM15. However, to achieve and maintain specific glycemic targets, the majority of patients require glucose-lowering drugs. Metformin is currently the first-line and widely used pharmacological therapy for patients with T2DM because of its potential benefits, including cardioprotective effect, loss of weight, and prevention of some comorbid diseases15–22. If lifestyle interventions and a maximally tolerated dose of metformin fail to achieve the glycemic target within 3 months follow-up, the regimen would be changed to combination therapy15.

Metformin-sulfonylurea combination therapy is the most widely used regimen in the management of T2DM23,24. Sulfonylureas are prescribed as second-line treatment options in the management of patients with T2DM, while they are still commonly prescribed as a first-line treatment as a substitute to metformin25. However, initiating treatment of T2DM with a sulfonylurea in place of metformin is associated with higher rates of ischaemic stroke, cardiovascular mortality, and hypoglycemia25–31. On the other side, the use of sulfonylureas as second-line treatments is associated with an increased risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction, all-cause mortality, and severe hypoglycemia, compared with metformin monotherapy; as a result, continuing metformin when introducing sulfonylureas appears to be safer than switching to another drug32. Such findings led to new requirements from licensing authorities that all new T2DM therapies should show cardiovascular efficacy and safety10.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2Is) are novel antidiabetic drugs that can inhibit sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 at the proximal tubule of the kidney. Those novel drugs can decrease renal glucose reabsorption, hyperglycemia, cardiovascular problems and they can increase urinary glucose excretion in patients with T2DM33–39. However, there is no clear evidence that shows the relative advantage of either metformin-sulphonylureas or metformin-SGLT2Is combination therapy on major treatment outcomes including CVD40. Management of T2DM remains challenging as choosing a second and/or third-line antidiabetic drug is personalized based on efficacy, risk of hypoglycemia, patient's comorbid conditions, impact on weight, side effects, and cost41. In particular, although most patients with T2DM require a combination pharmacological therapy, the choice of a best second-line drug is especially critical for the prevention of CVD. Thus, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was to compare the cardiovascular safety and efficacy of combination therapy of metformin-SGLT2Is and metformin-sulfonylureas in patients with T2DM.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review and meta-analysis has been registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database, ID: CRD4202015561642. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA 2015) guidelines43 for the design and reporting of the results.

Data sources and searches

We searched MEDLINE-PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), Embase (http://www.embase.com/), The Cochrane Library (http://www.cochranelibrary.com/), and ClinicalTtrials.gov (https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/) for completed studies that reported the safety and/or efficacy of metformin-SGLT2Is versus metformin-sulfonylureas combination therapies for patients with T2DM. We included RCTs without restriction on year of publication, but published in English language, up to 15 August 2019. The RCTs were needed to have at least a 1-year follow-up of patients. The keywords we used in different combinations using Boolean Operators were: metformin, biguanide, sodium-glucose co-transporter- 2 inhibitors, SGLT-2 inhibitors, dapagliflozin, canagliflozin, empagliflozin, ertugliflozin, sulfonylurea, gliclazide, glimepiride, glyburide, glibenclamide, glipizide, tolbutamide, type 2 diabetes mellitus, T2DM, cardiovascular outcomes, and randomized controlled trials (Supplementary file 1). All potentially eligible studies were considered for this review, irrespective of the primary outcomes. Manual searching was performed to find out additional eligible trials from the reference lists of key articles.

Eligibility

We formulated the study’s eligibility criteria using the PICOS (participants, interventions, comparison, outcomes, and study designs) description model44:

- Participants

- Patients with T2DM

- Man or woman of any age

- Who was taking a combination therapy of metformin-sulfonylurea or metformin-SGLT2Is

- Intervention

- A combination of metformin with any of the SGLT2Is, which could be dapagliflozin, canagliflozin, empagliflozin, or ertugliflozin.

- Comparator

- A combination of metformin with any of sulfonylureas compounds, which could be gliclazide, glipizide, glyburide, glibenclamide, or glimepiride.

- Outcomes

- Primary endpoints

- All-cause mortality

- Serious adverse events (SAEs).

- Secondary endpoints

- Cardiovascular mortality

- Non-fatal myocardial infarction

- Non-fatal stroke

- Hypoglycemia

- Changes in HbA1c

- Change in body weight,

- Changes in fasting plasma glucose (FPG)

- Changes in systolic blood pressure (SBP

- Changes in diastolic blood pressure (DBP)

- Changes in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)

- Changes in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C)

- Study design

- RCTs

- At least one-year duration of follow-up

- Published in English language

Study selection

Two independent authors examined the title and abstract of all searched studies. From the title and abstract of all studies identified by the database search, those studies duplicated and not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. The full texts of the remaining studies were further reviewed. Disagreements were resolved by consensus and if persisted, we arbitrated through discussion with a third author.

Data extraction

Two independent authors extracted the needed data from each RCTs. These include name of the first author, year of publication, trial registration, mean age of the participant, baseline average body weight, HbA1c, interventions, comparators, number of participants randomized, duration of follow-up, and patient-important outcomes. Data on the mean change of HbA1c (%), body weight (Kg), FPG (mmol/L), SBP (mmHg), DBP (mmHg), HDL-C (mmol/L), and LDL-C (mmol/L) were collected from baseline for continuous outcomes. The status and number of events were captured for the two groups, which include, death, hypoglycemia, adverse events (AEs), SAEs, SAEs related to study drugs, genital mycotic infection (GMI), and adverse cardiovascular events.

Assessment of risk of bias

We used the Cochrane risk of bias tool45 to assess the risk of bias in each included study and the risks were judged by two independent authors as “Low”, “Unclear”, or “High” based on the critical domains, including random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting. Disagreements were resolved by consensus and if persisted, we arbitrated through discussion with a third author.

Statistical analysis

We carried out meta-analysis using the computer software packages RevMan 5.346 to compare the cardiovascular safety and efficacy between the two combination therapies. Pooled results of continuous patient-important outcomes i.e., HbA1c, FPG, blood pressure, body weight, HDL-C, and LDL-C were reported using a mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Pooled results of binary outcomes i.e. all-cause mortality, AEs, AEs related to study drug, SAEs, SAEs related to study drug, hypoglycemic event, worsening of coronary artery disease, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), aortic aneurism, coronary artery occlusion (CAO) and GMI were summarized using risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI.

We used Mantel–Haenszel method47 to pool effect estimates of dichotomous outcomes and inverse variance for continuous outcomes. The analysis was conducted using a random-effects meta-analyses model as it assumes the observed estimates of the treatment can vary across studies because of the real differences in the treatment effect in each study as well as sampling variability (chance)48. We used Cochrane Q test49 to assess heterogeneity between studies, and I2 testing50 to quantify heterogeneity between studies, with values > 50% representing moderate-to-high heterogeneity. We carried out sensitivity and subgroup analysis by duration of the RCTs. We couldn’t conduct funnel plot and Egger test to check any possible reporting bias because the number of studies included in the meta-analyses are insufficient (less than 10 trials). We considered statistical analysis with a p-value < 0.05 statistically significant.

Results

Search results

We searched a total of 3,190 citations through the databases, of which we assessed 30 full-text studies for eligibility and found nine of them51–59 fulfilled the inclusion criteria. We excluded the rest 21 full-text articles23,24,60–78 mainly for they did not include SGLT2Is or sulfonylureas as a combination therapy; included a combination of more than two glucose-lowering drugs; included single glucose-lowering drug; data were driven from review or post hoc analysis of previous RCTs; had no active comparator; or had a duration of interventions less than a year (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study.

Study characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the nine RCTs included. Four RCTs51,54,56,59 used two different doses of SGLT2Is. The meta-analysis included all results of both doses for dichotomous outcomes but only a high dose of SGLT2Is for continuous outcomes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included RCTs.

| 1st author (year) | Registration | Age (year) | Weight (Kg) | HbA1c (%) | No. of pts | Intervention | Comparator | Follow –up (year) | Patient important outcomes | Met + SGLT2Is | Met + SU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ridderstråle (2018) 52 | NCT01167881 | ≥ 18 | 82.75 | 7–10 | 1545 (Male = 853, female = 692) | Metformin plus Empagliflozin 25 mg (n = 765) | Metformin plus Glimepiride 1–4 mg (n = 780) | 4 | HbA1c (%) | − 0.29 | − 0.10 |

| weight (Kg) | − 3.08 | 1.84 | |||||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | − 4.1 | 2.1 | |||||||||

| DBP (mmHg) | − 1.8 | 0.8 | |||||||||

| FPG (mmol//L) | − 0.3 | 0.4 | |||||||||

| AEs | 706 | 713 | |||||||||

| AEs related to drug | 221 | 277 | |||||||||

| SAEs | 161 | 153 | |||||||||

| SAEs related to drug | N/A | N/A | |||||||||

| Hypoglycemia | 23 | 218 | |||||||||

| Pt received rescue Rx | 176 | 265 | |||||||||

| Dyslipidemia | ↓fat | ↑fat | |||||||||

| GMI | 104 | 30 | |||||||||

| CV events | ↔ | ↑ | |||||||||

| Death | 8 | 8 | |||||||||

| Ridderstråle (2014) 53 | NCT01167881 | ≥ 18 | 82.75 | 7–10 | 1545 (Male = 853, female = 692) | Metformin plus Empagliflozin 25 mg (n = 765) | Metformin plus Glimepiride 1–4 mg (n = 780) | 2 | HbA1c | − 0.66 | − 0.55 |

| FPG | − 0.85 | − 0.17 | |||||||||

| Weight | − 3 | 1.5 | |||||||||

| SBP | − 3.1 | 2.5 | |||||||||

| DBP | − 1.8 | 0.9 | |||||||||

| AEs | 661 | 673 | |||||||||

| AEs related to drug | 190 | 252 | |||||||||

| SAEs | 119 | 89 | |||||||||

| Hypoglycemia | 19 | 189 | |||||||||

| Dyslipidemia | 41 | 39 | |||||||||

| GMI | 131 | 22 | |||||||||

| Pt’s HbA1c < 7% | 232 | 221 | |||||||||

| Pt received rescue Rx | 113 | 185 | |||||||||

| Death | 5 | 5 | |||||||||

| Hollander (2019) 54 | NCT01999218 | 58.2 ± 9.6 | 86.9 ± 19.6 | 7.8 ± 0.6 | 1315 (Male = 642, female = 673) | Metformin ≥ 1500 mg plus Ertugliflozin 15 mg and Metformin plus Ertugliflozin 5 mg (n = 880) | Metformin ≥ 1500 mg plus Glimepiride 1–8 mg (n = 435) | 2 | HbA1c | − 0.7 | − 0.4 |

| Weight | − 6.3 | 1.0 | |||||||||

| FPG | − 1.4 | − 0.5 | |||||||||

| SBP | − 3.2 | 2.1 | |||||||||

| DBP | − 1.5 | 0.7 | |||||||||

| HDL-C | ↑ | ↓ | |||||||||

| LDL-C | ↔ | ↔ | |||||||||

| Hypoglycemia | 35 | 77 | |||||||||

| AEs | 622 | 303 | |||||||||

| SAEs | 73 | 30 | |||||||||

| GMI | 67 | 3 | |||||||||

| SAEs related to drug | 4 | 1 | |||||||||

| Pt received rescue Rx | 60 | 31 | |||||||||

| Pt’s HbA1c < 7% | 228 | 123 | |||||||||

| Death | 9 | 1 | |||||||||

| Hollander (2017) 59 | NCT01999218 | 58.2 ± 9.6 | 86.8 ± 19.6 | 7.8 ± 0.6 | 1325 (Male = 642, female = 683) | Metformin ≥ 1500 mg plus Ertugliflozin 15 mg And Metformin plus Ertugliflozin 5 mg (n = 888) | Metformin ≥ 1500 mg plus Glimepiride 1–8 mg (n = 437) | 1 | HbA1c | − 1.2 | − 0.7 |

| FPG | − 2.3 | − 0.9 | |||||||||

| SBP | − 6.0 | 1.0 | |||||||||

| DBP | − 2.1 | 0.3 | |||||||||

| Weight | − 6.4 | 0.9 | |||||||||

| Sever hypoglycemia | 2 | 10 | |||||||||

| AEs | 525 | 269 | |||||||||

| SAEs | 45 | 12 | |||||||||

| Pt received rescue Rx | 41 | 14 | |||||||||

| SAE related to drug | 3 | 1 | |||||||||

| GMI | 56 | 3 | |||||||||

| HDL | ↑ | ↓ | |||||||||

| LDL | ↑ | ↓ | |||||||||

| Atherosclerosis | 0 | 1 | |||||||||

| History of PVD | 1 | 0 | |||||||||

| Pt’s HbA1c < 7% | 321 | 190 | |||||||||

| Death | 6 | 1 | |||||||||

| Del Prato (2015) 58 | NCT00660907 | 58.2 | 89.7 | 7.5 | 814 | Metformin 1500–2500 mg plus Dapagliflozin 2.5–10 mg (n = 406) | Metformin 1500–2500 mg plus Glipizide 5–20 mg (n = 408) | 4 | HbA1c (%) | − 0.10 | 0.20 |

| FPG (mg/dl) | − 13.3 | − 3.8 | |||||||||

| Weight (Kg) | − 3.65 | 0.73 | |||||||||

| SBP | − 3.69 | − 0.02 | |||||||||

| DBP | N/A | N/A | |||||||||

| HDL-C | N/A | N/A | |||||||||

| LDL-C | N/A | N/A | |||||||||

| AEs | 356 | 355 | |||||||||

| AEs related to drug | 127 | 127 | |||||||||

| SAEs | 75 | 81 | |||||||||

| SAEs related to drug | 9 | 7 | |||||||||

| Hypoglycemia | 4 | 46 | |||||||||

| Poor glycemic control | 156 | 182 | |||||||||

| Cardiovascular events | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| GMI | 5 | 3 | |||||||||

| Death | 2 | 5 | |||||||||

| Nauck (2014) 57 | NCT00660907 | 58.4 | 88 | 7.7 | 814 | Metformin ≥ 1500 mg plus Dapagliflozin 2.5–10 mg (n = 406) | Metformin ≥ 1500 mg plus Glipizide 5–20 mg (n = 408) | 2 | HbA1c | − 0.32 | − 0.14 |

| FPG | − 1.12 | − 0.68 | |||||||||

| Weight | − 3.7 | 1.4 | |||||||||

| SPB | − 2.7 | 1.2 | |||||||||

| DBP | N/A | N/A | |||||||||

| HDL-C | N/A | N/A | |||||||||

| LDL-C | N/A | N/A | |||||||||

| AEs | 337 | 338 | |||||||||

| AEs related to drug | 122 | 118 | |||||||||

| SAEs | 51 | 62 | |||||||||

| SAEs related to drug | 8 | 7 | |||||||||

| Hypoglycemia | 17 | 187 | |||||||||

| Aortic aneurysm | 0 | 1 | |||||||||

| AMI | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| CAO | 0 | 1 | |||||||||

| Ventricular arrhythmia | 1 | 0 | |||||||||

| Worsening CAD | 1 | 0 | |||||||||

| GMI | 60 | 12 | |||||||||

| Poor glycemic control | 55 | 74 | |||||||||

| Death | 0 | 4 | |||||||||

| Nauck (2011) 55 | NCT00660907 | 58.4 | 88 | 7.7 | 814 | Metformin 1500–2500 mg plus Dapagliflozin2.5–10 mg (n = 406) | Metformin1500–2500 plus Glipizide 5–20 mg (n = 408) | 1 | HbA1c (%) | − 0.52 | − 0.52 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | − 1.12 | − 1.59 | |||||||||

| Weight (Kg) | − 3.2 | 1.2 | |||||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | − 3.8 | 0.9 | |||||||||

| DBP (mmHg) | ↓ | ↑ | |||||||||

| HDL-C | ↑ | ↓ | |||||||||

| AEs | 318 | 318 | |||||||||

| AEs related to drug | 110 | 110 | |||||||||

| SAEs | 35 | 46 | |||||||||

| SAEs related to drug | 6 | 4 | |||||||||

| Hypoglycemia | 14 | 162 | |||||||||

| GMI | 50 | 11 | |||||||||

| Poor glycemic control | 1 | 15 | |||||||||

| Acute MI | 0 | 1 | |||||||||

| Worsening CAD | 1 | 0 | |||||||||

| Death | 0 | 3 | |||||||||

| Leiter (2015) 56 | NCT00968812 | 56.2 | 86.6 | 7.8 | 1450 | Metformin plus Canagliflozin 100 mg and Metformin plus canaglifloxin 300 mg (n = 968) | Metformin plus Glimepiride 1–8 mg (n = 482) | 2 | HbA1c (%) | − 1.39 | − 0.55 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | − 2.4 | − 0.6 | |||||||||

| Weight (Kg) | − 7.2 | 0.8 | |||||||||

| SBP | − 5.1 | 1.7 | |||||||||

| DBP | − 3.5 | − 0.02 | |||||||||

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 0.38 | 0.06 | |||||||||

| HDL-C | 0.21 | 0.00 | |||||||||

| Triglycerides | ↑ | ↔ | |||||||||

| Pt’s HbA1c < 7% | 448 | 212 | |||||||||

| AEs | 732 | 378 | |||||||||

| AEs related to drug | 297 | 134 | |||||||||

| SAEs | 94 | 69 | |||||||||

| Hypoglycemia | 73 | 197 | |||||||||

| GMI | 116 | 11 | |||||||||

| Death | 6 | 2 | |||||||||

| Cefalu (2013) 51 | NCT00968812 | 56.2 | 86.6 | 7.8 | 1450 | Metformin plus Canagliflozin 100 mg and Metformin plus canaglifloxin 300 mg (n = 968) | Metformin plus Glimepiride 1–8 mg (n = 482) | 1 | HbA1c | − 1.75 | − 0.81 |

| FPG | − 2.87 | − 1.02 | |||||||||

| Weight | − 7.7 | 0.7 | |||||||||

| SBP | − 7.9 | 0.2 | |||||||||

| DBP | − 4.3 | − 0.1 | |||||||||

| LDL-C | 0.37 | 0.05 | |||||||||

| HDL-C | 0.18 | − 0.01 | |||||||||

| Triglycerides | − 0.32 | − 0.01 | |||||||||

| Pt’s HbA1c < 7% | 541 | 264 | |||||||||

| AEs | 643 | 330 | |||||||||

| AEs related to drug | 263 | 113 | |||||||||

| SAEs | 50 | 39 | |||||||||

| Hypoglycemia | 51 | 165 | |||||||||

| GMI | 97 | 8 | |||||||||

| Death | 2 | 2 |

AEs adverse events, AMI acute myocardial infraction, CAD coronary artery disease, CAO coronary artery occlusion, CV cardiovascular, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, FPG fasting plasma glucose, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, SAEs serious adverse events, GMI genital mycotic infection, MI myocardial infraction, Rx treatment, SGLT2Is sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors, SU sulfonylurea, Met metformin, N/A not available.

Participant characteristics

From the nine RCTs, we polled and included 10,974 patients with T2DM who were in either of the two combination therapies at least for a year (Table 1).

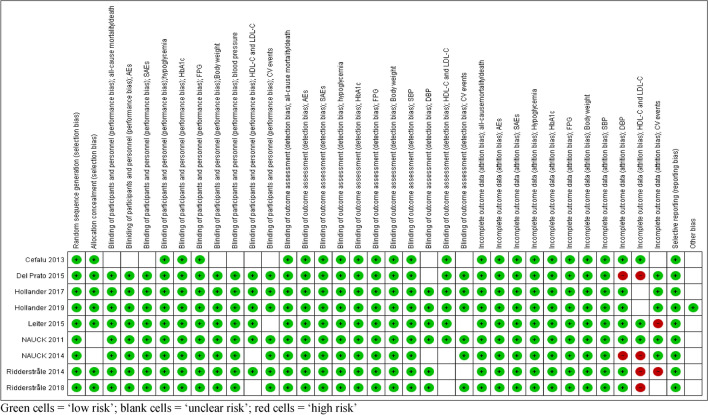

Methodological quality and risk of bias

The studies were found to be “low risk of bias” when these studies were subjected to the Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool for Quality Assessment of Randomized Controlled Trials (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgments about each 'risk of bias' item for included trials. Green cells = ‘low risk’; blank cells = ‘unclear risk’; red cells = ‘high risk’.

Efficacy and safety assessments

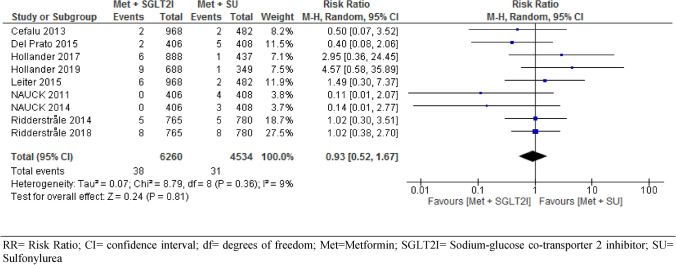

All-cause mortality

All the nine included RCTs involving 10,974 participants assessed all-cause mortality/death events between intervention and control groups. Our meta-analysis of pooled results revealed no significant difference in all-cause mortality/death events between patients with T2DM who were on metformin-SGIT2Is and metformin-sulphonylureas combination therapies (RR = 0.93, 95% CI [0.52, 1.67], p = 0.81), with statistically non-significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 9%) (Fig. 3). Subgroup analysis by duration of follow-up showed no significant difference in risk of death between the two groups, year 1 (RR = 0.66, 95% CI [0.12, 3.71], p = 0.64, year 2 (RR = 1.25, 95% CI [0.47, 3.32], p = 0.66, and year 4 (RR = 0.80, 95% CI [0.35, 1.84], p = 0.60) (S2).

Figure 3.

Comparison of all-cause mortality/death events between patients with T2DM who were on metformin-SGIT2I and metformin-sulphonylureas combination therapies. RR risk ratio; CI confidence interval; df degrees of freedom; Met metformin; SGLT2I sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor; SU sulfonylurea.

Cardiovascular events

Two trials55,57 evaluated the cardiovascular efficacy of metformin-SGIT2I versus metformin-sulphonylureas combination therapies. The studies followed-up 1,628 participants for coronary artery disease (CAD) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI). After 2 years follow-up, there was no significant difference observed in CAD (RR = 3.01, 95% CI [0.31, 28.92], p = 0.34) and AMI (RR = 0.63, 95% CI [0.08, 5.09], p = 0.66) between the two arms. One of the two trials57 further evaluated 814 patients for coronary artery occlusion (CAO) and aortic aneurism and reported no significant difference in the risk of developing these diseases between the two arms (S3).

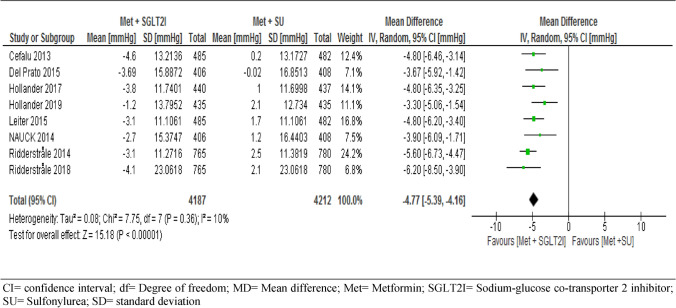

Of the nine trials included, eight trials followed-up 8,399 participants for changes in SBP and five trials followed-up 5,804 participants for changes in DBP from the baseline. The report showed a significant decreases for both SBP (MD = − 4.77, 95% CI [− 5.39, − 4.16] mmHg, p < 0.001) and DBP (MD = − 2.07, 95% CI [− 2.74, − 1.40] mmHg, p < 0.001) in patients taking metformin-SGIT2I combination therapy (Figs. 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Comparison of changes in systolic blood pressure between patients who were on metformin-SGIT2I and metformin-sulphonylureas combination therapies. CI confidence interval; df degree of freedom; MD mean difference; Met metformin; SGLT2I sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor; SU sulfonylurea; SD standard deviation.

Figure 5.

Comparison of changes in diastolic blood pressure between patients who were on metformin-SGIT2I and metformin-sulphonylureas combination therapies. CI confidence interval; df degree of freedom; MD mean difference; Met metformin; SGLT2I sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor; SU sulfonylurea; SD standard deviation.

Two trials51,56 assessed the change in HDL-C and LDL-C levels from baseline between the two arms. Both HDL-C and LDL-C levels were reduced in patients who received metformin-sulphonylureas combination therapies. However, the pooled effect was not statistically significant between the two arms in HDL-C (MD = 4.32, 95% CI [− 4.00, 12.64] mmol/L, p = 0.32), I2 = 99%) and LDL-C (MD = 3.63, 95% CI [− 3.96, 11.22] mmol/L, P = 0.35, I2 = 88%) (S14 & S15) respectively.

Adverse events

With pooled data from the nine trials, we found no statistically significant difference in the risk of developing adverse events between the two arms (RR = 1.00, 95% CI [0.99, 1.02], p = 0.66, I2 = 0% (Fig. 6). We performed a sensitivity analysis by removing the highest weighted study52 and found no significant difference in the risk of developing adverse events between the two arms (RR = 1.00, 95% CI [0.98, 1.02], I2 = 0%). The result of the subgroup analysis was consistent at different duration of follow-up (RR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.94, 1.03] at 1 year, RR = 1.00, 95% CI [0.97, 1.04] at 2 years and RR = 1.01, 95% CI [0.98, 1.04] at 4 years, with p = 0.57 for subgroup difference (S4). Seven RCTs assessed the risk of adverse events related to study drug, of which two RCTs showed lower risk in patients on metformin-sulphonylureas combination therapies but the pooled analysis showed no statistically significant difference (RR = 0.97, 95% CI [0.85, 1.10], p = 0.60, I2 = 69%, (S5). Subgroup analysis of the seven RCTs showed that risk of adverse events related to study drug was similar across different duration of the study, RR = 1.09, 95% CI [0.94, 1.26] at year one, RR = 0.94, 95% CI [0.75, 1.21] at year two, and RR = 0.89, 95% CI [0.73, 1.10] at year four.

Figure 6.

Risk of adverse events between patients who were on metformin-SGIT2I and metformin-sulphonylureas combination therapies. RR risk ratio; CI confidence interval; df degrees of freedom; Met metformin; SGLT2I sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor; SU sulfonylurea.

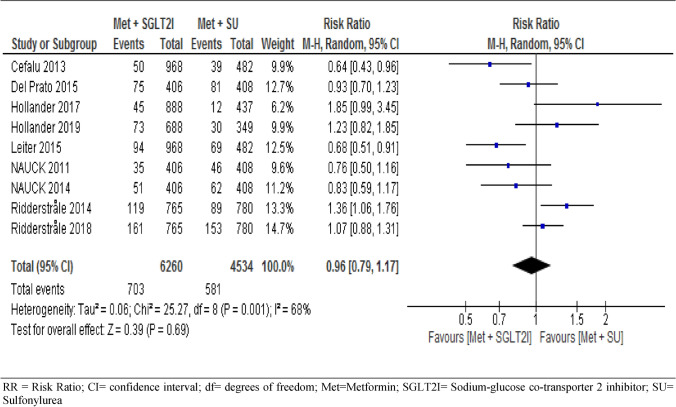

Serious adverse events

All included trials assessed the risk of serious adverse events during the study period, where our analysis of the pooled data showed no significant difference between the two groups (RR = 0.96, 95% CI [0.79, 1.17], with statistically significant heterogeneity across trials (I2 = 68%, p = 0.001) (Fig. 7). Consistently, subgroup analysis showed no significant difference between the two groups at year 1 (95% CI (RR = 0.92 [0.53, 1.59], I2 = 75%), year 2 (RR = 0.98 [0.69, 1.40], I2 = 80%), and year four (RR = 1.02 [0.87, 1.20], I2 = 0%), with subgroup differences of p = 0.92 and I2 = 0% (S6).

Figure 7.

Risk of serious adverse events between patients who were on metformin-SGIT2I and metformin-sulphonylureas combination therapies. RR risk ratio; CI confidence interval; df degrees of freedom; Met metformin; SGLT2I sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor; SU sulfonylurea.

Five trials assessed the risk of serious adverse events related to study drug. The pooled result of these trials showed that serious adverse events related to study drug were less frequent on patients taking metformin-sulphonylureas combination, but the pooled result was not significant at 95% CI (RR = 1.34 [0.75, 2.36] (S7).

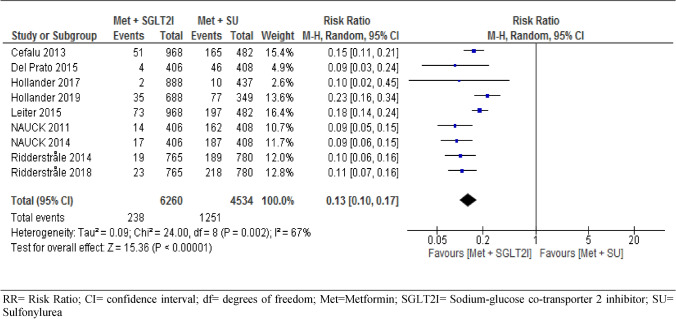

Hypoglycemic events

We analyzed hypoglycemic events on pooled results of the nine trials involving 10,794 T2DM patients, considering the occurrence of at least one hypoglycemic event during the follow-up period. Patients under metformin-SGIT2I combination therapy were found to experience significantly fewer hypoglycemic events as compared to patients under metformin-sulphonylureas combination therapy (RR = 0.13, 95% CI [0.10, 0.17], P < 0.001) I2 = 67%, p = 0.002) (Fig. 8). We performed sensitivity analysis by removing two low weighted trials58,59. However, the result of the remaining trials was similar to the nine trials in risk of hypoglycemia (RR = 0.13, 95% CI [0.10, 0.18, P < 0.001) with increased between study heterogeneity (I2 = 73%, P = 0.009). To see the robustness of the result, we did subgroup analysis at different duration of follow-up. However, the risk of experiencing hypoglycemic events was consistently more frequent under patients on metformin-sulfonylureas combination therapy at 95% CI RR = 0.12[0.08, 0.19], p < 0.001 at year one, RR = 0.15[0.10, 0.22], p < 0.001 at year two and RR = 0.10[0.07, 0.15], p < 0.001 at year four respectively. On the other hand, patients on metformin-SGLT2I were found to experience significantly higher GMI than patients on metformin-sulfonylureas combination therapy RR = 5.00, 95% CI [3.94, 6.33], p < 0.001 (S8).

Figure 8.

Risk of hypoglycemia between patients who were on metformin-SGIT2I and metformin-sulphonylureas combination therapies. RR risk ratio; CI confidence interval; df degrees of freedom; Met metformin; SGLT2I sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor; SU sulfonylurea.

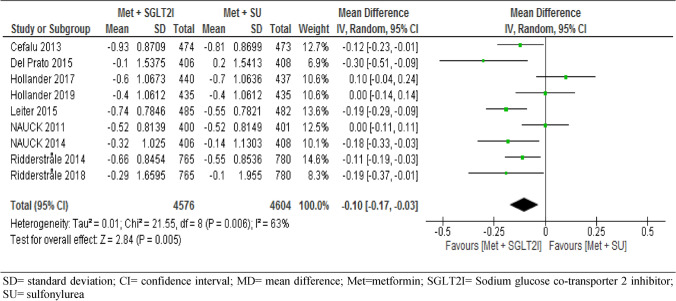

Glycated hemoglobin A1c

All the nine RCTs involving 9,180 participants assessed the changes in HbA1c (%) from baseline between the two arms. The pooled data of these trials showed significant difference in the mean difference of HbA1c between patients on metformin-SGLT2I and metformin-sulfonylureas combination therapies; MD = − 0.10, 95% CI [− 0.17, − 0.03] %, p = 0.005), I2 = 63%, p = 0.006) (Fig. 9). Interestingly, subgroup analysis by duration of follow-up showed a reduction of HbA1c from baseline was not statistically significant between the two groups at year-one, with MD = − 0.01[− 0.13, 0.11] %, I2 = 67%. However, metformin-SGLT2I induced a greater reduction in HbA1c from baseline after 2 years (MD = − 0.12[− 0.20, − 0.05] %, p = 0.001) and after 4 years (MD = − 0.24[− 0.37, − 0.10] %, p = 0.0007) (S9).

Figure 9.

Comparison of change in HbA1c (%) from baseline between patients who were on metformin-SGIT2I and metformin-sulphonylureas combination therapies. SD standard deviation; CI confidence interval; MD mean difference; Met metformin; SGLT2I sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor; SU sulfonylurea.

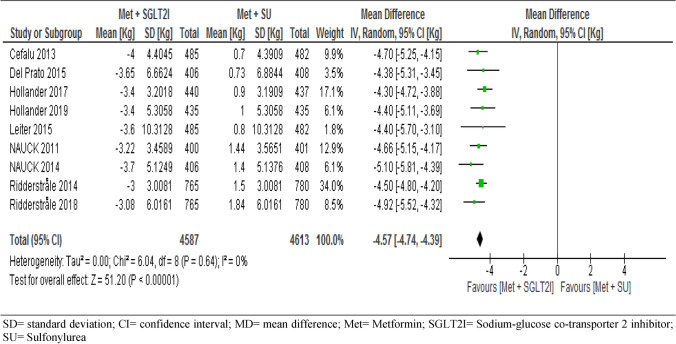

Bodyweight

All trials included in the meta-analysis assessed the change in body weight from baseline between the two groups. The pooled result showed that body weight of patients in the metformin-SGLT2I was significantly reduced from baseline compared to patients in the metformin-sulfonylureas (MD = − 4.57, 95% CI [− 4.74, − 4.39] kg, p < 0.001) (Fig. 10). We conducted a sensitivity analysis by removing the low weighted56 and the high weighted53 study and the result was consistent with the nine studies. Surprisingly, subgroup analysis also showed consistent results following different duration of follow-up that the mean difference of change in body weight from baseline at year one (MD = − 4.52 [− 4.79, − 4.24] kg, p < 0.001, at year two (MD = − 4.56 [− 4.81, − 4.31] kg, p < 0.001, and at year four (MD = − 4.76[− 5.27, − 4.26] kg, p < 0.0000, respectively (S10).

Figure 10.

Comparison of change in body weight (Kg) from baseline between patients who were on metformin-SGIT2I and metformin-sulphonylureas combination therapies. SD standard deviation; CI confidence interval; MD = mean difference; Met metformin; SGLT2I sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor; SU sulfonylurea.

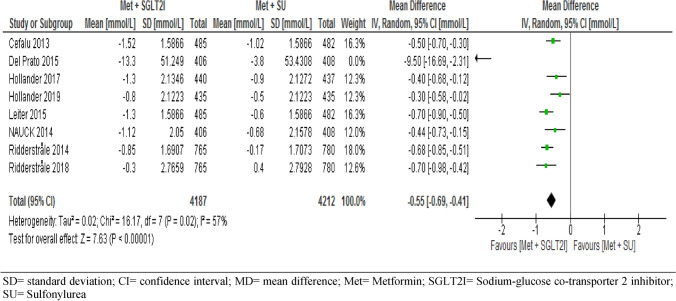

Fasting plasma glucose

Eight trials assessed the change in FPG level from baseline between the intervention and control. The pooled result showed that FPG level was significantly reduced from baseline with patients in the metformin-SGLT2I combination therapies (MD = − 0.55, 95% CI [− 0.69, − 0.41] mmol/L, p < 0.001, I2 = 57%) (Fig. 11). We conducted sensitivity analysis by removing one outlier with a low weighted study58. But the result was consistent with the eight study (MD = − 0.55, 95% CI [− 0.67, − 044], p < 0.001). Subgroup analysis of seven trials also showed consistent results following different duration of intervention and control that the mean difference of change in FPG level from baseline at year one (MD = − 0.47 [− 0.63, − 0.30] mmol/L, p < 0.001, I2 = 0%), at year two (MD = − 0.56 [− 0.74, − 0.38] mmol/L, p < 0.001, I2 = 59% and at year four (MD = − 0.70[− 0.98, − 0.42] mmol/L, p < 0.001) (S11).

Figure 11.

Comparison of change in FPG (mmol/L) from baseline between patients who were on metformin-SGIT2I and metformin-sulphonylureas combination therapies. SD standard deviation; CI confidence interval; MD mean difference; Met metformin; SGLT2I sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor; SU sulfonylurea.

Discussion

The result of this systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the risk of all-cause mortality/death events was not statistically significant between patients in the metformin-SGLT2I and metformin-sulfonylureas combination therapies. In agreement with our findings, a previous study reported a non-significant difference in all-cause mortality and cardiovascular death between the two arms40. Similarly, study77 also revealed a lower and statistically nonsignificant cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality in T2DM patients who were on metformin-sulfonylurea combination therapy. However, another study29 reported that the use of sulfonylureas as a second-line drug has significantly associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction and all-cause mortality.

The goal of durable glycemic control is to reduce the long-term risk of diabetes-related cardiovascular morbidity and mortality57. Recent studies showed that SGLT2Is have been shown to decrease cardiovascular events in treating high-risk patients with T2DM34. Likewise, the addition of empagliflozin to metformin therapy improves in patients with established CVD or heart failure78. Even though the current meta-analysis of metformin-SGLT2I combination showed a favorable effect on cardiovascular outcomes (acute myocardial infarction, aortic aneurism, coronary artery occlusion, and atherosclerosis), the pooled analysis was not statistically significant.

Lowering blood pressure is significantly important to reduce the risk of CVD and death in many patients with T2DM. A 10-mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure decreased the risk of major CVD events by 20%79. SGLT2Is induced a greater reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure73. Similar with the other findings, the pooled result of our study showed a reduction in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure with patients in the metformin-SGLT2Is combination therapy as compared with metformin-sulfonylureas, which might be due to the effect of SGLT2Is reducing renal glucose reabsorption and increasing urinary excretion51. Consistent with our findings, previous studies reported a greater increase from baseline in HDL-C and LDL-C in patients who were on SGLT2Is groups as compared with sulfonylureas51,54,56.

The result of this meta-analysis showed that the overall incidence of AEs was similar across the two arms, which is consistent with a trial reported by elsewhere59. However, metformin-SGLT2Is combination was associated with a higher episode of GMI which is similar to other meta-analysis reported an increased risk of GMI with SGLT2Is73. In addition, for both genders, the proportion of patients reporting symptoms of GMI was higher in the SGLT2Is group than in the sulfonylureas58. However, these infections respond to standard antimicrobial treatment and their incidence declines with time57. SAEs such as ketoacidosis, bone fractures, and pyelonephritis were rarely reported with metformin-SGLT2Is53, while the pooled result of the current study did not find a statistically significant difference between metformin-SGLT2I and metformin-sulfonylureas combinations. Even though the pooled analysis did not find statistically significant results, AEs related to study drug was observed more in patients with metformin-SGLT2Is, but more SAEs related to study drug in metformin-sulfonylureas. This might be due to the hypoglycemic effect of sulfonylureas and GMI as a result of SGLT2Is respectively.

Sulfonylureas as second-line drugs are associated with an increased risk of severe hypoglycemia79, and our study is in support of this. The hypoglycemic effect of sulfonylureas might be due to its insulin-dependent mechanism of action, while the less hypoglycemic effect of SGLT2Is is due to the non-insulin dependent mechanism of action.

Obesity is one of the main risk factors for T2DM and representing a major worldwide health problem. Lowering body weight is an important part of T2DM management. SGLT2Is has been associated with an added benefit of weight loss in patients with T2DM, whereas sulfonylureas are reported to increase body weight80. In support of this evidence, our study showed a 4.57 kg weight loss in metformin-SGLT2Is group than the metformin-sulfonylureas. The weight loss caused by SGLT2Is is probably due to the loss of calories via urine and glucose-induced osmotic diuresis51.

Long term glycemic control is the major goal of diabetes management to prevent both microvascular and macrovascular complications of DM81. Both metformin-SGLT2Is and metformin-sulfonylureas combinations are effective to control HbA1c for a short duration of follow-up. However, for a long duration of follow-up, metformin-SGLT2Is are more effective than metformin-sulfonylureas73. Our finding is consistent with this evidence where both groups were equally effective for a one-year duration of follow-up; however, as the duration of follow-up increases to 4 years, metformin-SGLT2Is combination showed a significant reduction from baseline in HbA1c. Eight previously conducted trials reported a higher reduction of FPG in patients randomized to metformin-SGLT2Is51–54,56–59, and our pooled result is in support of their finding as it showed reduction of FPG under patients on metformin-SGLT2Is.

This study reported important information about cardiovascular safety, efficacy, and cardiovascular risk factors control between the two combination therapies. However, we acknowledge that available studies are very limited and heterogeneous. There remains a need for additional long-term trials comparing the overall safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of metformin-SGLT2Is and metformin-sulfonylureas combination therapies.

Conclusion

Combination therapy of metformin and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors are a safe and efficacious alternative to combination therapy of metformin and sulfonylureas for patients with T2DM who are at risk of cardiovascular comorbidity. However, there remains a need for additional long-term randomized controlled trials as available studies are very limited and heterogeneous.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- AEs

Adverse events

- AMI

Acute myocardial infraction

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- CAO

Coronary artery occlusion

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- FPG

Fasting plasma glucose

- GMI

Genital mycotic infection

- HbA1C

Hemoglobin A1c

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- MD

Mean difference

- MI

Myocardial infraction

- RCT

Randomized controlled trials

- RR

Risk Ratio

- SAEs

Serious adverse events

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- SGLT2Is

Sodium-glucose Co-transporter 2 inhibitors

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Author contributions

D.G. (first author) was responsible for the conception of review protocol, study design, literature search, data extraction, quality assessment, data analysis, interpretation, and writing the original manuscript. D.G. (second author) and T.M. were responsible for the quality assessment and reviewing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This review did not receive any specific grant from any organization.

Data availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its supporting information files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-020-80603-8.

References

- 1.International Diabetus Federation. IDF diabetes atlas: 9th ed (International Diabetes Federation, Brussels). https://diabetesatlas.org/en/resources/ (2019).

- 2.Williams R, et al. Global and regional estimates and projections of diabetes-related health expenditure: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108072. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merino J, et al. Quality of dietary fat and genetic risk of type 2 diabetes: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;366:l4292. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vujosevic S, et al. Screening for diabetic retinopathy: New perspectives and challenges. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:337–347. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30411-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maddaloni E, et al. Time-varying risk of microvascular complications in latent autoimmune diabetes of adulthood compared with type 2 diabetes in adults: a post-hoc analysis of the UK Prospective Diabetes Study 30-year follow-up data (UKPDS 86) Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:206–215. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zweck E, Westenfeld R, Szendroedi J. oral semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 DIABETES. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;381:2075–2076. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1913157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asrih M, Gariani K. Impact of SGLT inhibitors on multiple organ defects in diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2020;16:411–418. doi: 10.2174/1573399815666191105151828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cosentino F, et al. Addressing cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A report from the European Society of Cardiology Cardiovascular Roundtable. Eur. Heart J. 2019;40:2907–2919. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steg PG, et al. Ticagrelor in patients with stable coronary disease and diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;381:1309–1320. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellary S, Tahrani AA, Barnett AH. Evidence-based prescribing of diabetes medications: are we getting closer? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:176–177. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whyte MB, et al. Disparities in glycaemic control, monitoring, and treatment of type 2 diabetes in England: A retrospective cohort analysis. PLoS Med. 2019;16:e1002942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manne-Goehler J, et al. Health system performance for people with diabetes in 28 low- and middle-income countries: A cross-sectional study of nationally representative surveys. PLoS Med. 2019;16:e1002751. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Z, et al. Medication management support in diabetes: A systematic assessment of diabetes self-management apps. BMC Med. 2019;17:127. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1362-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sattar N. Advances in the clinical management of type 2 diabetes: A brief history of the past 15 years and challenges for the future. BMC Med. 2019;17:46. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1281-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019: Abridged for primary care providers. Clin Diabetes. 2019;37:11–34. doi: 10.2337/cd18-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petrie JR, Rossing PR, Campbell IW. Metformin and cardiorenal outcomes in diabetes: A reappraisal. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2020;22:904–915. doi: 10.1111/dom.13984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blümel JE, et al. Metformin use is associated with a lower risk of osteoporosis in adult women independent of type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity. REDLINC IX study. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2020;36:421–425. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2020.1718092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shuai Y, Li C, Zhou X. The effect of metformin on gastric cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2020;22:1580–1590. doi: 10.1007/s12094-020-02304-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou J, et al. Meta-analysis: The efficacy of metformin and other anti-hyperglycemic agents in prolonging the survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann. Hepatol. 2020;19:320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.aohep.2019.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang K, Yang W, Dai H, Deng Z. Cardiovascular risk following metformin treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Results from meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tseng CH. Metformin use is associated with a lower risk of uterine leiomyoma in female type 2 diabetes patients. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019;10:2042018819895159. doi: 10.1177/2042018819895159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell MK, et al. Metformin treatment for diabetes mellitus correlates with progression and survival in colorectal carcinoma. Transl. Oncol. 2020;13:383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2019.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma M, Beckley N, Nazareth I, Petersen I. Effectiveness of sitagliptin compared to sulfonylureas for type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled on metformin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017260. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foroutan N, Muratov S, Levine M. Safety and efficacy of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors vs sulfonylurea in metformin-based combination therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Invest. Med. 2016;39:E48–62. doi: 10.25011/cim.v39i2.26481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Filion KB, et al. Sulfonylureas as initial treatment for type 2 diabetes and the risk of adverse cardiovascular events: A population-based cohort study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019;85:2378–2389. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng PC, et al. Comparing the effect of dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibitors and sulfonylureas on albuminuria in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus: A prospective open-label study. J. Clin. Med. 2019;8:1715. doi: 10.3390/jcm8101715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laires P, et al. Factors associated with physicians' decision to discontinue or down-titrate sulfonylureas for type 2 diabetes patients. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2019;19:71–79. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2018.1510774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGowan LD, Roumie CL. Sulfonylureas as second line treatment for type 2 diabetes. BMJ. 2018;362:3041. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Douros A, Dell'Aniello S, Yu HY, Filion KB. Sulfonylureas as second line drugs in type 2 diabetes and the risk of cardiovascular and hypoglycaemic events: Population based cohort study. BMJ. 2018;362:2693. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitlock RH, et al. A safety comparison of metformin vs sulfonylurea initiation in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: a retrospective cohort study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020;95:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mekuria AN, Ayele Y, Tola A, Mishore KM. Monotherapy with metformin versus sulfonylureas and risk of cancer in type 2 diabetic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Diabetes Res. 2019;2019:7676909. doi: 10.1155/2019/7676909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ke C, et al. Mortality and cardiovascular risk of sulfonylureas in South Asian, Chinese and other Canadians with diabetes. Can. J. Diabetes. 2017;41:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2016.08.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeFronzo RA, Davidson JA, Del Prato S. The role of the kidneys in glucose homeostasis: A new path towards normalizing glycaemia. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2012;14:5–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shehadeh N, Raz I, Nakhleh A. Cardiovascular benefit in the limelight: shifting type 2 diabetes treatment paradigm towards early combination therapy in patients with overt cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17:117. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0760-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santamarina M, Carlson CJ. Review of the cardiovascular safety of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and the clinical relevance of the CAROLINA trial. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2019;19:60. doi: 10.1186/s12872-019-1036-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marsico F, et al. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on major cardiovascular events in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus with or without established cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Heart J. 2020;2020:ehaa082. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malik AH, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with the use of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled Trials. Cardiol. Rev. 2020;28:116–124. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santos-Ferreira D, Gonçalves-Teixeira P, Fontes-Carvalho R. SGLT-2 inhibitors in heart failure and type-2 diabetes: Hitting two birds with one stone? Cardiology. 2020;145:311–320. doi: 10.1159/000504694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mirabelli M, et al. Long-Term effectiveness and safety of SGLT-2 inhibitors in an Italian cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Res. 2019;2019:3971060. doi: 10.1155/2019/3971060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madsen KS, et al. Metformin and second- or third-generation sulphonylurea combination therapy for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;4:CD012368. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012368.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Baar MJB, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors in combination therapy: From mechanisms to clinical considerations in type 2 diabetes management. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1543–1556. doi: 10.2337/dc18-0588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gebrie, D. Getnet, D. & Manyazewal, T. Cardiovascular safety and efficacy of combination therapy with metformin and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors versus metformin and sulfonylureas in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020155616 (2020).

- 43.Shamseer L, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guyatt GH, et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the questions and deciding on important outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011;64:395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higgins JPT. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2. New York: Wiley; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. (2014).

- 47.Suesse T, Liu I. Mantel-Haenszel estimators of a common odds ratio for multiple response data. Stat. Methods Appl. 2019;28:57–76. doi: 10.1007/s10260-018-0429-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riley RD, Higgins JP, Deeks JJ. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ. 2011;342:d549. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cefalu WT, et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin versus glimepiride in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin (CANTATA-SU): 52-Week results from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;382:941–950. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60683-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ridderstråle M, et al. Empagliflozin compared with glimepiride in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes: 208-Week data from a masked randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018;20:2768–2777. doi: 10.1111/dom.13457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ridderstråle M, et al. Comparison of empagliflozin and glimepiride as add-on to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes: A 104-week randomised, active-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:691–700. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hollander P, et al. Results of VERTIS SU extension study: safety and efficacy of ertugliflozin treatment over 104 weeks compared to glimepiride in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled on metformin. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2019;35:1335–1343. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2019.1583450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nauck MA, et al. Dapagliflozin versus glipizide as add-on therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes who have inadequate glycemic control with metformin: A randomized, 52-week, double-blind, active-controlled noninferiority trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2015–2022. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leiter LA, et al. Canagliflozin provides durable glycemic improvements and body weight reduction over 104 weeks versus glimepiride in patients with type 2 diabetes on metformin: A randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:355–364. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nauck MA, et al. Durability of glycaemic efficacy over 2 years with dapagliflozin versus glipizide as add-on therapies in patients whose type 2 diabetes mellitus was inadequately controlled with metformin. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16:1111–1120. doi: 10.1111/dom.12327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Del Prato S, et al. Long-term glycaemic response and tolerability of dapagliflozin versus a sulphonylurea as add-on therapy to metformin in type 2 diabetes patients: 4-year data. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2015;17:581–590. doi: 10.1111/dom.12459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hollander P, et al. Ertugliflozin compared with glimepiride in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled on metformin: The VERTIS SU Randomized Study. Diabetes Ther. 2017;9:193–207. doi: 10.1007/s13300-017-0354-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hanefeld M, Brunetti P, Schernthaner GH, Matthews DR, Charbonnel BH. One-year glycemic control with a sulfonylurea plus pioglitazone versus a sulfonylurea plus metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:141–147. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Comaschi M, Corsi A, Di Pietro C, Bellatreccia A, Mariz S. The effect of Pioglitazone as add-on therapy to metformin or sulfonylurea compared to a fixed dose combination of metformin and glibenclamide on diabetic dyslipidemia. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2008;18:373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gallwitz B, et al. 2-year efficacy and safety of linagliptin compared with glimepiride in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin: A randomized, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012;380:475–483. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60691-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Charokopou M, et al. The cost-effectiveness of dapagliflozin versus sulfonylurea as an add-on to metformin in the treatment of Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet. Med. 2012;32:890–898. doi: 10.1111/dme.12772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lavalle-González FJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin compared with placebo and sitagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes on background metformin monotherapy: A randomized trial. Diabetologia. 2013;56:2582–2592. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-3039-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brady EM, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing the glucagon like peptide-1 receptor agonist liraglutide to a sulphonylurea as add on to metformin in patients with established type 2 diabetes during Ramadan: The Treat 4 Ramadan Trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2014;16:527–536. doi: 10.1111/dom.12249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vaccaro O, et al. Effects on the incidence of cardiovascular events of the addition of pioglitazone versus sulfonylureas in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin (TOSCA.IT): A randomized, multicenter trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:887–897. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30317-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Home PD, et al. Rosiglitazone evaluated for cardiovascular outcomes in oral agent combination therapy for type 2 diabetes (RECORD): A multicenter, randomized, open-label trial. Lancet. 2009;373:2125–2135. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60953-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hsu PF, et al. Cardiovascular benefits of acarbose vs sulfonylureas in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018;103:3611–3619. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moon JS, et al. The effect of glargine versus glimepiride on pancreatic β-cell function in patients with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled on metformin monotherapy: Open-label, randomized, controlled study. Acta Diabetol. 2014;51:277–285. doi: 10.1007/s00592-013-0553-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ahrén B, Mathieu C, Bader G, Schweizer A, Foley JE. Efficacy of vildagliptin versus sulfonylureas as add-on therapy to metformin: Comparison of results from randomised controlled and observational studies. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1304–1307. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3222-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hong J, et al. Effects of metformin versus glipizide on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1304–1311. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Udiawar MV, Bain SC. Liraglutide in combination with metformin or sulfonylurea for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in adult patients. Clin. Med. Insights. 2012;4:251–261. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen Z, Li G. Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors compared with sulfonylureas in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Drug Invest. 2019;39:521–531. doi: 10.1007/s40261-019-00781-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li J, et al. Efficacy and safety of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors as add-on to metformin and sulfonylurea treatment for the management of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Endocr J. 2018;65:335–344. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ17-0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Milder TY, et al. Combination therapy with an SGLT2 inhibitor as initial treatment for type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2019;8:45. doi: 10.3390/jcm8010045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ahren B, et al. HARMONY 3: 104-week randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trial assessing the efficacy and safety of albiglutide compared with placebo, sitagliptin, and glimepiride in patients with type 2 diabetes taking metformin. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2141–2148. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ghotbi AA, et al. Association of hypoglycemic treatment regimens with cardiovascular outcomes in overweight and obese subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3746–3753. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Scheen AJ. The safety of empagliflozin plus metformin for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2018;17:837–848. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2018.1497159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ettehad D, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:957–967. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Apovian CM, Okemah J, O’Neil PM. Body weight Considerations in the management of type 2 diabetes. Adv Ther. 2019;36:44–58. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0824-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.American Diabetes Association Glycemic Targets: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2019;41:S55–S64. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its supporting information files.