Ubiquitination regulates selective substrate recognition of IKKβ.

Abstract

The classic NF-κB pathway plays crucial roles in various immune responses and inflammatory diseases. Its key kinase, IKKβ, participates in a variety of pathological and physiological processes by selectively recognizing its downstream substrates, including p105, p65, and IκBα, but the specific mechanisms of these substrates are unclear. Hyperactivation of one of the substrates, p105, is closely related to the onset of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Nfkb1-deficient mice. In this study, we found that IKKβ ubiquitination on lysine-238 was substantially increased during inflammation. Using mass spectrometry, we identified USP16 as an essential regulator of the IKKβ ubiquitination level that selectively affected p105 phosphorylation without directly affecting p65 or IκBα phosphorylation. Furthermore, USP16 was highly expressed in colon macrophages in patients with IBD, and myeloid-conditional USP16-knockout mice exhibited reduced IBD severity. Our study provides a new theoretical basis for IBD pathogenesis and targeted precision intervention therapy.

INTRODUCTION

The nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) pathway, which has been recognized for more than 30 years, has been found to be involved in a number of pathophysiological processes in various cells (1, 2). NF-κB, a protein complex that regulates gene transcription and is widely present in eukaryotic cells, can specifically bind to promoters or enhancers to promote the transcription and expression of multiple genes (3–5). The NF-κB signaling pathway is tightly correlated with the immune response and critical pathophysiological processes such as cell proliferation, transformation, and apoptosis (6, 7). The NF-κB family consists of five members, including p50 (encoded by Nfkb1), p52 (encoded by Nfkb2), p65 (encoded by RelA), c-rel (encoded by Rel), and relB (encoded by RelB) (4, 5). All five of these members contain a Rel homology domain in the N terminus, which is responsible for the binding of each member with DNA. In unstimulated cells, most of the NF-κB dimers present are inactive because they are bound to inhibitory factors in the cytoplasm (IκBα, IκBβ, IκBξ, IκBε, Bcl-3, and the precursor proteins p105 and p100) (8–11). In the classic NF-κB pathway, IκB kinases (IKKs), including IKKα and IKKβ, can be activated by numerous stimulators, such as bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1), T cell and B cell mitogens, viral double-stranded RNA, and various physical and chemical pressures (12, 13). The classic NF-κB pathway is dominated by the role of IKKβ, which phosphorylates IκB family members such as IκBα and p105 (14–16). Phosphorylated IκB family proteins release active NF-κB molecules into the nucleus through ubiquitin modification and proteasome-dependent degradation. IKKβ is involved in many pathophysiological processes and activates distinct substrates under different stimuli and regulatory mechanisms (15, 16). To perform appropriate functions in immune responses, IKKβ selectively recognizes and activates different substrates in a manner dependent on the precise posttranslational regulation of IKKs. Previous studies have revealed that IKKβ phosphorylates serine (S) 927 of p105 when activated by TNF-α, which is required for processing p105 into p50 (17). Schröfelbauer et al. (18) reported that NF-κB essential modifier (NEMO) selectively recruits activated IκBα as an adaptor but has no effect on the phosphorylation of p105. However, the underlying mechanism that determines the selective substrate recognition and activation of IKKβ remains unclear.

The classic NF-κB pathway plays essential roles in innate immune responses mediated by various myeloid cells, such as macrophages and neutrophils (19–22). When stimulated by LPS, TNF-α, or IL-1β, IKKβ promotes the nuclear translocation of p65 and p50 and induces the expression of inflammatory factors such as TNF-α, IL-12, IL-1β, and IL-6, which further lead to tissue damage (11, 23). Activation of the NF-κB pathway is also closely related to the onset of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (24). There is also some evidence indicating that Nfkb1 mutation contributes to the pathological features of IBD. The intestinal macrophages of IBD patients with mutant Nfkb1 exhibit continuous activation of NF-κB signaling, and mice carrying mutant Nfkb1 that cannot express p105 present spontaneous intestinal inflammation that is similar to IBD (25). In addition, IKKβ myeloid cell conditional knockout (KO) mice exhibit impaired sensitivity to experimental colitis and intestinal tumor generation (26). Therefore, the selective recognition and activation of p105 by IKKβ plays an important role in the onset of IBD. However, there is still a lack of clinical therapeutic drugs targeting NF-κB because of its widespread functions in the regulation of various physiological processes. The current strategies for suppressing NF-κB focus mainly on proteasome blockers, IKK inhibitors, nuclear translocation inhibitors, and DNA binding inhibitors. While these drugs inhibit the corresponding pathological processes, they also have a wide range of side effects, including renal toxicity and neuropathy, and can even promote tumor progression and recurrence (2, 27, 28). Therefore, these drugs cannot achieve clinically effective treatment of intestinal inflammation.

In this study, we found that p105 can still be mildly phosphorylated even without NEMO. Biochemical data have shown that IKKβ can be modified by nonproteolytic ubiquitination during activation of the classic NF-κB signal. This ubiquitination significantly inhibits the capacity of IKKβ to phosphorylate p105 without affecting another substrate, IκBα. By using mass spectrometry, we identified a deubiquitinase, Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 16 (USP16), that specifically binds IKKα and IKKβ but not NEMO. In mammalian cells, USP16 is expressed diffusely during mitosis and contributes to cell cycle processing. When cells enter mitosis, USP16 is phosphorylated during the G2-M transition and dephosphorylated in anaphase, which has been reported to correlate with H2A deubiquitination (29). USP16 specifically deubiquitinates histone H2A on lysine (K) 119 and K15 but not H2B in vivo, which leads to subsequent phosphorylation of H3 and chromosome segregation (30). When coupled with protein regulator of cytokinesis 1, USP16-mediated H2A deubiquitination has been shown to regulate embryonic stem cell (ESC) gene expression (31) and hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) function (32). In response to DNA damage, the HECT and RLD domain containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2 (HERC2)–dependent increase in the level of USP16 negatively regulates ubiquitin foci formation by H2AK119Ub and K15Ub (33). The human Usp16 gene is mapped on chromosome 21 and is one of the genes uniquely triplicated in Down syndrome. Current studies have shown that triple USP16 impairs the self-renewal of HSCs, as suggested by proliferation defects in normal fibroblasts and neural progenitors (34). Furthermore, USP16 is involved in human hepatocellular carcinoma, since USP16 down-regulation critically promoted tumor growth (35). Our recent study demonstrated that in activated T cells, USP16 specifically removes the K29-linked polyubiquitin chains of calcineurin A to regulate its activity. USP16 deficiency in T cells causes a reduction in peripheral T cells coupled with diminished autoimmune symptoms (36). However, the function of USP16 in nonproliferative cells remains unclear. Here, our results showed that macrophages and fibroblasts lacking USP16 showed significant decreases in p105 phosphorylation, while their IκBα phosphorylation remained comparable to that of their wild-type (WT) littermates. Consistently, NF-κB–targeted genes in macrophages showed a clear reduction in various inflammatory cytokines when stimulated with distinct agonists of Toll-like receptors (TLRs). Mice with conditional KO of USP16 in myeloid cells displayed severe reductions in the symptoms of dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)–induced colitis and related colon carcinogenesis.

RESULTS

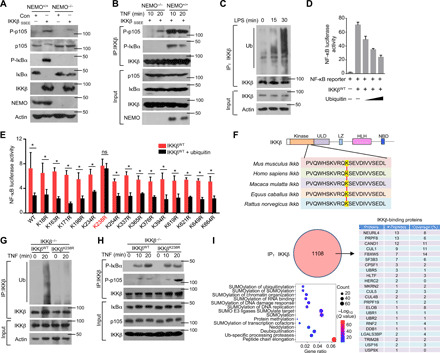

Ubiquitination of IKKβ inhibits its ability to phosphorylate p105

Previous evidence has revealed that NEMO has no effect on the phosphorylation of p65 or p105 but is specifically required for IκBα phosphorylation (18, 37). To validate this finding, we repeated the experiment by overexpressing constitutively active IKKβ (IKKβSSEE) in NEMO−/− fibroblasts, thus excluding the function of NEMO in IKKβ activation. Contrary to earlier observations, NEMO was indispensable for the phosphorylation of the IKK substrates p105 and IκBα (Fig. 1A). However, in contrast to IκBα, weak phosphorylation of p105 was observed under NEMO deficiency (Fig. 1A). In an in vitro kinase assay, high phosphorylation of IκBα proteins was found in WT cells, but no signals were detected in NEMO−/− fibroblasts. Consistently, TNF-α stimulation exhibited a weak capacity to induce p105 phosphorylation of p105 (Fig. 1B), suggesting that in vivo, IKKβ’s recognition of p105 is also regulated by additional factors.

Fig. 1. Ubiquitination of IKKβ inhibits the phosphorylation of p105.

(A) NEMO-deficient MEFs were reconstituted with the indicated constructs. The Western blot analysis results of p105 and IκBα phosphorylation and steady-state expression levels in these cells are shown. (B) By using these reconstituted MEFs, IKK kinase activity on different substrates was determined with an in vitro kinase assay in the presence of GST-IκBα or GST-p105. (C) Mouse BMDMs isolated from WT mice were stimulated with LPS. Whole-cell lysate (WL) was subjected to IP using an anti-IKKβ antibody, which was followed by IB analysis of the ubiquitination (Ub) level. (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with NF-κB luciferase reporters along with IKKβWT and ubiquitin expression plasmids. The readouts were normalized to Renilla luciferase activity and are presented as the fold changes relative to the values in untransfected cells. (E) IKKβWT (WT) and multiple site mutants were transfected into HEK293T cells. After 8 hours of TNF-α treatment, the cells were lysed for luciferase assays. ns, not significant. (F) Sequence alignment of Ub sites on IKKβ orthologs of different species. (G) IKKβWT and IKKβK238R were reconstituted into IKKβ−/− cells. WLs were subjected to IP using anti-IKKβ followed by Ub analysis. (H) IKK kinase activity was determined by kinase assays upon IP with an anti-IKKβ antibody. (I) HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-IKKβ and subjected to IP using anti-HA before mass analysis. The associated proteins of IKKβ are presented as indicated. The bars and error bars show the means ± SEMs. The significance of the differences in (E) was determined by the two-tailed Student’s t test. *P < 0.05.

In physiological processes, various posttranslational modifications (e.g., methylation, ubiquitination, and phosphorylation) lay foundations for the recruitment of downstream molecules and promotion of signaling cascades (38). Ubiquitination and deubiquitination are common and reversible posttranslational modifications of proteins that play precise regulatory roles in various physiological and biochemical reactions, especially immune responses (39, 40). Unexpectedly, IKKβ in primary bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) was rapidly ubiquitinated upon TLR4 agonist stimulation without any change in its protein level (Fig. 1C). Increased ubiquitination levels of IKKβ significantly impaired NF-κB transcriptional activity, as demonstrated by NF-κB luciferase reporter assays (Fig. 1D). To directly determine the potential ubiquitination sites on IKKβ, we generated a series of point mutants of IKKβ in which lysine (K) residues were replaced with arginine (R) residues. Mutation of K238 of human IKKβ caused the protein to be resistant to ubiquitination-induced activity impairment, whereas mutation at several other sites of IKKβ did not affect the suppressive function of ubiquitination (Fig. 1E). As shown in Fig. 1F, K238 is located in the kinase domain of IKKβ and is conserved among different species. To examine the role of K238 in signal transduction induced by IKKβ, we stably expressed WT IKKβ (IKKβWT) or IKKβ K238R (IKKβK238R) in mouse IKKβ−/− fibroblasts. The K238R mutation did not change the protein level of IKKβ at steady state from the WT control level (Fig. 1G). However, under TNF-α treatment, there was much less ubiquitination of IKKβK238R than of WT IKKβ (Fig. 1G). Reconstitution of the cells with IKKβK238R greatly promoted the phosphorylation of p105 without affecting the activation of IκBα (Fig. 1H), suggesting that the ubiquitination of IKKβ at K238 is specifically required to inhibit the phosphorylation of p105. To clarify the critical molecules involved in the IKKβ ubiquitination process, we analyzed the proteins interacting with IKKβ in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells with TNF stimulation. As shown in Fig. 1I, we identified 1108 proteins bound to IKKβ, 23 of which were associated with the ubiquitin modification process. In contrast to the numbers of molecules that promoted ubiquitination, we identified only two deubiquitinases, USP16 and USP9X. Our previous study provided evidence that p105 phosphorylation is specifically impaired in USP16−/− CD4+ T cells under T cell receptor stimulation (36), which implied that USP16 may contribute to the selective recognition of IKK substrates. Collectively, these data indicated that the USP16-mediated deubiquitination of IKKβ may be specifically involved in the phosphorylation and processing of p105.

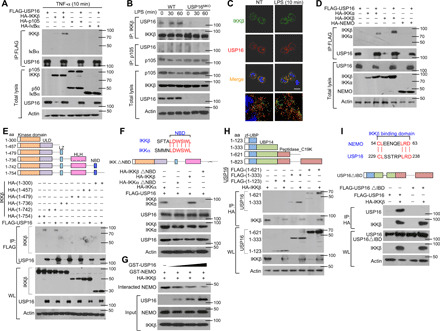

USP16 selectively interacts with IKKβ and IKKα

This observation raised a critical question regarding whether USP16 directly regulates IKKβ activity or p105 phosphorylation. Under TNF-α stimulation, coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays demonstrated that USP16 physically associated with IKKβ but not with p105 or IκBα in cotransfected HEK293T cells (Fig. 2A). To further confirm the interaction between endogenous USP16 and IKKβ, we generated USP16fl mice and crossed them with Lyz2-Cre mice to delete USP16 in myeloid cells, producing myeloid cell–specific USP16-KO (USP16MKO) mice (fig. S1A). Immunoblot (IB) analysis revealed loss of USP16 expression in the BMDMs but not in the T cells or B cells of USP16MKO mice (fig. S1B). The USP16MKO mice were born at the expected Mendelian ratios and exhibited normal growth and survival without any obvious abnormalities in the development of macrophages and neutrophils (fig. S1C). In addition, relative to WT mice, the USP16MKO mice exhibited no differences in the frequencies of T cells and B cells in the spleen (fig. S1D). The frequency of regulatory T cells among CD4+ splenic T cells in USP16MKO mice was comparable to that in WT mice (fig. S1E). USP16 deficiency in myeloid cells had no effect on T cell homeostasis (fig. S1F) or the frequencies of T helper 1 (TH1) and TH17 cells in the spleen (fig. S1G). The co-IP results revealed continuous interaction between endogenous USP16 and IKKβ in BMDMs, and LPS stimulation did not promote or suppress this association (Fig. 2B). In contrast to the situation in primary T cells, USP16 in BMDMs was constitutively located in the cytoplasm and significantly colocalized with IKKβ, as revealed by a marked increase in Pearson’s correlation coefficient (Fig. 2C and fig. S2A).

Fig. 2. USP16 specifically interacts with IKKβ but not p105 or IκBα.

(A) HEK293T cells were transfected with USP16-, IKKβ-, p105-, and IκBα-expressing plasmids. IB of HA was performed followed by IP with an anti-FLAG antibody on WLs. (B) The interaction among USP16, IKKβ, and p105 was assessed in WT and USP16-deficient BMDMs activated by LPS. WLs were subjected to IP using an anti-IKKβ or anti-p105 antibody and then to IB analyses of the associated USP16. (C) Confocal microscopy analysis of the colocalization of USP16, IKKβ, and DAPI in WT macrophages stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) as indicated. Scale bar, 5 μm. NT, nontreatment. (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. The interaction between USP16 and IKK components was evaluated by co-IP assay. (E and F) The associations between USP16 and various truncation mutants of IKKβ (E) or a USP16 interaction-defective mutant (IKKβ∆NBD) (F) were detected through the indicated IP and IB analyses. (G) USP16 competently bound to IKKβ and inhibited the interaction between IKKβ and NEMO. (H and I) The binding amounts of IKKβ and various truncation mutants of USP16 (H) or an IKKβ interaction-defective mutant (USP16∆IBD) (I) were detected by the indicated IP. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments. aa, amino acids.

IKKα and IKKβ contain similar functional domains; thus, we further evaluated the interaction of USP16 with IKKα and NEMO. Unexpectedly, USP16 could also associate with IKKα, but no signal of its binding to NEMO was detected (Fig. 2D). IKKβ and IKKα contain at least three critical domains, including a kinase domain in the N-terminal region, a leucine zipper that is required for homo- and heterodimerization, and a NEMO-binding domain (NBD). In transfected HEK293T cells, the results of co-IP revealed that the association between IKKβ and USP16 was dependent on the NBD of IKKβ (Fig. 2E). Sequence analysis revealed six conserved amino acids between IKKβ and IKKα in the NBD (Fig. 2F). Depletion of the NBD disrupted the interaction of USP16 with both IKKβ and IKKα (Fig. 2F), which further suggests that USP16 and NEMO may competitively bind to IKKβ and IKKα. Consistent with this hypothesis, the interaction of NEMO and IKKβ decreased significantly with increasing amounts of transfected USP16 (Fig. 2G).

USP16 contains a zinc finger ubiquitin-binding domain (zf-UBP), a UBP14 domain, and a peptidase domain (Fig. 2H). To map the crucial domains of USP16 that are responsible for its interaction with IKKβ, we generated distinct truncation mutants that lacked different domains. Co-IP indicated that the UBP14 domain is indispensable for USP16 binding to IKKβ (Fig. 2H). By comparison with NEMO, we identified five conserved amino acids that are important for binding between USP16 and IKKβ, as suggested by the disappearance of the signal upon deletion of the sequence (Fig. 2I). All of these data indicate that USP16 may regulate the activation of NF-κB by directly interacting with IKKs.

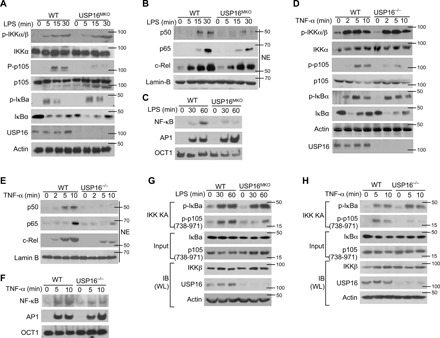

USP16 specifically promotes p105 phosphorylation

Usp16 acts as a histone H2A deubiquitinase to promote H2A deubiquitination and subsequent gene expression in ESCs and the hematopoietic system (31, 32). We thus performed an experiment to evaluate the ubH2A level in WT and USP16-deficient macrophages under LPS stimulation. In contrast to observations in ESCs and HSCs, USP16 deficiency did not increase ubH2A levels (fig. 2B). We next elucidated the role of USP16 in regulating the TLR- or TNF-α–mediated activation of canonical NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and downstream transcription factors. As shown in fig. S2C, USP16-deficient BMDMs displayed comparable activation of the MAPKs p38, ERK (extracellular signal–regulated kinase), and JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase). Compared with WT BMDMs, USP16-deficient BMDMs showed appreciable defects in the LPS-stimulated phosphorylation of p105 (Fig. 3A) but displayed no differences in the activation of IKKs and IκBα (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, we observed significant reductions in nuclear p50 levels and small decreases in nuclear-translocated c-Rel and p65 levels in LPS-stimulated USP16-deficient BMDMs (Fig. 3B). In response to LPS, USP16-deficient BMDMs showed clear reductions in NF-κB activation and comparable activating protein 1 (AP1) activation (Fig. 3C). Similar to other research, our previous study suggested that macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) induced the synthesis and nuclear translocation of noncanonical NF-κB during macrophage differentiation (21, 41). We thus evaluated p100 expression in the cytoplasm and the levels of p52 and RelB in the nucleus in WT and USP16-deficient macrophages. As shown in fig. S2D, we found no difference in the p100 level and p52 nuclear translocation between WT and USP16-deficient BM cells under M-CSF stimulation, suggesting that USP16 is dispensable for noncanonical NF-κB activation.

Fig. 3. IKK-induced p105 phosphorylation requires the participation of USP16.

(A) The phosphorylation of IKKs and their substrates in WLs of WT and USP16-deficient BMDMs was measured by IB analysis. (B) The amounts of each NF-κB member in cytoplasmic (CE) and nuclear (NE) extracts were detected by IB. (C) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) of NE extracts of WT and USP16-deficient BMDMs stimulated with LPS (1 μg/ml), as assessed with HRP-labeled NF-κB, AP1, or OCT1. (D to F) Similar analyses of the activation of IKKs (D) and transcription factors (E) were performed via IB and EMSA (E) in USP16−/− MEFs as described above. (G and H) IKK kinase assays and IB assays using WLs of LPS-stimulated BMDMs derived from WT and USP16MKO mice (G) or USP16−/− MEFs (H). The data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Similar to that observed in macrophages, the phosphorylation of p105 in USP16−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) was also impaired under TNF-α stimulation, although the activation of IKKs and IκBα was similar (Fig. 3D). Notably, USP16 deficiency greatly impaired the activation of NF-κB induced by TNF-α (Fig. 3, E and F). USP16 deficiency strongly inhibited the activation of p105 by the typical IKK complex under LPS stimulation, as revealed by an in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 3G). These phenomena were also observed in MEFs stimulated by TNF-α (Fig. 3H), suggesting that USP16 is specifically required for p105 phosphorylation but has no effect on another IKK substrate, IκBα.

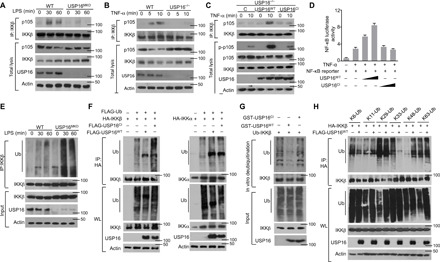

USP16 functions as a deubiquitinase of IKKβ and promotes its interaction with p105

To further clarify the underlying mechanism by which USP16 regulates p105 phosphorylation, we examined the physical interaction of endogenous p105 with IKKβ. As shown in Fig. 4A, USP16 is indispensable for the association between p105 and IKKβ, as suggested by the lack of a binding signal between these two molecules in USP16-deficient BMDMs. Consistently, the interaction between IKKβ and p105 in MEFs stimulated by TNF-α was also disrupted by the absence of USP16, indicating that USP16 is broadly essential for the binding of p105 and IKKβ in various cell types (Fig. 4B). We further detected the binding domain of IKKβ with p105 and IκBα by using the distinct truncation of IKKβ. A previous study indicated that IKKβ recruits IκBα depending on NEMO as a scaffold (2). NEMO interacts with a C-terminal sequence within IKKβ termed the NBD (3), which is far from the K238 ubiquitination site. In contrast to IκBα, the association of IKKβ with p105 did not require NEMO and thus is independent of its NBD domain. By using IKKβ truncation, we found that the interaction between IKKβ and p105 required the kinase domain (1-300) of IKKβ, as suggested by the co-IP assay (fig. S3A). We further generate the truncation of IKKβ kinase domain as N-terminal 1-200, 1-250, and 1-300. Co-IP assay indicated that the binding domain of IKKβ with p105 located at 200-250, where the K238 ubiquitination site falls into. Collectively, these data imply that K238 ubiquitination may selectively disrupt the interaction between IKKβ and P105 but has no effect on IκBα recognition (fig. S3B).

Fig. 4. USP16-mediated DUB of IKKβ is required for its binding to p105.

(A and B) The interaction between IKKβ and p105 was assessed in WT and USP16-deficient BMDMs stimulated by LPS (1 μg/ml) (A) or in TNF-α–treated USP16−/− MEFs (B) via IP with an anti-IKKβ antibody. (C) USP16-deficient MEFs were reconstituted with WT or catalytically inactive USP16. IB analysis of the interaction between IKKβ and p105 under TNF-α (50 ng/ml) stimulation was performed as indicated. (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with an NF-κB–luciferase reporter plasmid in the presence (+) or absence (−) of the indicated empty vector or expression plasmids. Luciferase assays were performed, and the results are presented as fold changes based on the empty vector group 36 hours after transfection. (E) IKKβ was isolated by IP (under denaturing conditions) from WLs of WT and USP16-deficient BMDMs and subjected to IB assays using anti-ubiquitin (top). Protein lysates were also subjected to direct IB (bottom). (F) HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-tagged ubiquitin along with the indicated expression plasmids. The ubiquitination levels of IKKβ and IKKα were examined by IB. Cell lysates were also subjected to direct IB (bottom three). (G) In vitro assays were used to evaluate USP16-mediated IKKβ DUB. Recombinant WT or inactive USP16 (USP16mut) was incubated with ubiquitinated IKKβ isolated from transfected HEK293T cells. Ubiquitination was detected by IB. (H) HEK293T cells were transfected with multiple ubiquitin mutants (mutations at K6, K11, K48, K63, K29, and K33) and the indicated expression plasmids. HA-tagged IKKβ was isolated by IP, and the ubiquitination level was then detected by IB. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

As a deubiquitinase, USP16 has been found to be required for calcium signal transduction in T cells and chromosomal segregation in ESCs (36). To characterize the deubiquitinase (DUB) activity of USP16, we stably expressed WT USP16 (USP16WT) or its catalytically inactive C205S mutant (USP16CI) in mouse USP16−/− fibroblasts. In these reconstituted USP16−/− fibroblasts, USP16WT, but not USP16CI, rescued the phosphorylation of p105 and the interaction between IKKβ and p105 (Fig. 4C). In addition, transfection of USP16WT, but not USP16CI, increased TNF-α–induced NF-κB activity in HEK293T cells, as demonstrated by NF-κB luciferase reporter assays (Fig. 4D and fig. S3C), suggesting that USP16 affects IKKβ in a manner dependent on its deubiquitinase activity. Furthermore, we evaluated the ubiquitination levels of IKKβ in macrophages under LPS stimulation. Although no effect on the protein levels of IKKβ was detected, USP16 deficiency significantly promoted the ubiquitination of endogenous IKKβ (Fig. 4E). We further evaluated the capacity of USP16 to deubiquitinate IKKβ in cotransfected HEK293T cells. USP16WT specifically removed the polyubiquitin chain from IKKβ but not from IKKα (Fig. 4F). USP16 mediated DUB of IKKβ directly, while the USP16CI mutant lost its ability to regulate IKKβ ubiquitination, as suggested by in vitro DUB assays (Fig. 4G). We next examined the subtypes of polyubiquitin chains conjugated to IKKβ, which could be removed by USP16 in cotransfected HEK293T cells. USP16 selectively removed K33-linked polyubiquitin chains from IKKβ and had moderate effects on K6- and K29-linked polyubiquitin chains (Fig. 4H). We further transfected hemagglutinin (HA)–tagged K33R-linked ubiquitin expression constructs into HEK293T cells. The results indicated that the K33R-linked polyubiquitin chain on IKKβ could not be removed by USP16 (fig. S3D), suggesting that K33-linked ubiquitination may be the major subtype of IKKβ ubiquitination. In general, the removal of a subtype of ubiquitination from a substrate in an overexpression system is accompanied by an artificial increase in another type of ubiquitination in vitro. However, this endogenous phenomenon needs to be further verified in primary cells. We thus evaluated the K48-linked ubiquitination of IKKβ in macrophages under LPS stimulation. Compared to the normal immunoglobulin G (IgG) control, we did not observe any sign of K48-linked ubiquitin on IKKβ in WT macrophages. In addition, we found no reduction in the K48-linked ubiquitination of IKKβ in USP16-deficient macrophages (fig. S3E). The various types of linkage are usually associated with different cellular functions, as K48-linked polyubiquitin chains are involved in proteasomal degradation. Our data indicated that there is no obvious difference in IKKβ protein levels in WT and USP16-deficient macrophages. As K238 is the critical ubiquitination site on IKKβ, we knocked down USP16 expression in both IKKβWT- and IKKβK238R-reconstituted IKKβ−/− MEF cells. With IKKβK238R, USP16 silencing no longer impaired the phosphorylation of p105 (fig. S3F).

USP16 is indispensable for the induction of canonical NF-κB–targeted genes

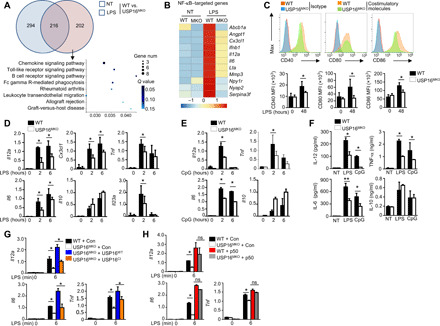

To elucidate the function of USP16 in regulating inflammatory responses, we monitored the major changes in mRNA abundance in the transcriptome. We identified only 202 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) induced by LPS in USP16-deficient BMDMs compared with WT littermates (fold change > 2; Fig. 5A). Ingenuity Pathway Analysis indicated that the major signaling pathway altered in USP16-deficient BMDMs was associated with the TLR signaling pathway and various immunological diseases (Fig. 5A). As expected, multiple NF-κB–targeted genes, including Il6, Il12a, and Ifnb, were specifically down-regulated in USP16-deficient BMDMs stimulated with LPS, as shown by the heatmap (Fig. 5B). The absence of USP16 not only suppressed the expression of inflammatory cytokines but also significantly inhibited the levels of costimulators, such as CD40, CD80, and CD86, on the surfaces of BMDMs (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5. USP16 is required for the induction of various NF-κB–targeted genes.

(A) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of DEGs between WT and USP16-deficient BMDMs under nontreatment or LPS-stimulated conditions for 6 hours. The KEGG analysis results of the enriched biological processes for these DEGs are shown. (B) Heatmap showing basal LPS-responsive (right) NF-κB–targeted genes among the DEGs of WT and USP16-deficient BMDMs. (C) Flow cytometry of the expression of CD40, CD80, and CD86 in WT and USP16-deficient BMDMs in response to LPS stimulation. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. (D and E) qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA (vertical axes) in WT or USP16-deficient BMDMs unstimulated (0 hour) or stimulated for 2 or 6 hours with LPS (100 ng/ml) (D) or CpG (25 nM) (E). (F) ELISA results for the indicated cytokines in the supernatants of WT or USP16-deficient BMDMs stimulated with LPS for 12 and 24 hours. (G) qRT-PCR analysis of the indicated genes in USP16-deficient BMDMs reconstituted with USP16WT and USP16CI and subjected to LPS stimulation. (H) qRT-PCR analysis of proinflammatory cytokine production in WT and USP16-deficient BMDMs reconstituted with p50. All qRT-PCR data are presented as the fold induction relative to the Actb mRNA level. The data are presented as the means ± SEMs and are representative of at least three independent experiments. The statistical analysis results show the variations among experimental replicates. Two-tailed unpaired t tests were performed. *P < 0.05.

We further confirmed the functions of USP16 in the LPS-mediated induction of proinflammatory cytokines by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assay. The results showed that USP16 acts as a common regulator of the induction of multiple proinflammatory cytokines by LPS (TLR4 ligand; Fig. 5D), CpG (TLR9 ligand; Fig. 5E), polyI:C (pIC; a TLR3 ligand; fig. S4A), and R848 (TLR7 ligand; fig. S4B). The same results were obtained by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which was used to evaluate the secreted cytokines (Fig. 5F). The genes rapidly induced by TNF were also significantly suppressed in USP16-deficient MEFs (fig. S4C).

The reconstitution of BMDMs with USP16WT greatly reversed the induction of multiple cytokines, but no similar effects were observed in the USP16CI-reconstituted group (Fig. 5G), which further indicates that the catalytic activity of USP16 is essential for its effects on IKKβ. p105 is proteolytically processed by the proteasome to generate p50, which acts as a transcription factor. We thus reconstituted WT and USP16-deficient BMDMs with a retroviral vector encoding p50, which eliminated the differences caused by USP16 deficiency (Fig. 5H). These results demonstrate the pivotal roles of USP16 in regulating p105 activation and proinflammatory cytokines.

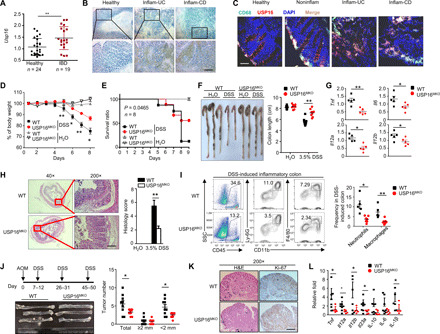

USP16 deficiency in macrophages suppresses the onset of colitis

To investigate the in vivo function of USP16 in regulating macrophage-mediated inflammatory diseases, we first examined the mRNA levels of USP16 in colon macrophages isolated from healthy donors or patients with IBD. Compared to those from healthy controls, macrophages from patients with IBD exhibited significantly increased amounts of USP16 (Fig. 6A). Public datasets also revealed higher expression of USP16 in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (UC) than in healthy donors (fig. S5A). The expression of USP16 in inflammatory areas was also higher than that in noninflammatory sections (fig. S5B). Correlation analysis showed that patients with higher USP16 mRNA levels in colon macrophages had obviously higher Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI) values (fig. S5C). Immunohistochemical analyses further revealed higher expression of USP16 in both Crohn’s disease and UC biopsy specimens than in normal control specimens (Fig. 6B). In contrast to USP16 in the intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) of healthy donors, USP16 exhibited significant colocalization with CD68 in UC and Crohn’s disease sections (Fig. 6C). A DSS-induced acute colitis model was further used to mimic the clinical pathogenesis of UC. We challenged WT and USP16MKO mice with 3% DSS for five successive days and then monitored their susceptibility by measuring body weight loss, stool consistency index (SCI) values, and survival ratios. As shown in Fig. 6 (D and E) and fig. S5C, lower body weight loss, lower SCI values, and lower survival ratios were observed in USP16MKO mice after DSS treatment than in control mice, but no difference was found between H2O-treated groups. Macroscopic analyses indicated significantly longer colons in the USP16MKO mice than in the WT mice under DSS-treated conditions (Fig. 6F). qRT-PCR assays revealed reduced mRNA levels of a series of proinflammatory cytokines in colonic macrophages isolated from USP16MKO mice (Fig. 6G). The increased expression of chemokines in macrophages is a major characteristic of IBD and stimulates the recruitment of leukocytes to the colon. In addition to proinflammatory cytokines, multiple chemokines derived from macrophages—including Cxcl1, Ccl2, Ccl3, Ccl7, Ccl8, and Ccl12—were also significantly reduced in DSS-treated USP16MKO mice (fig. S5D). These results indicated that USP16 deficiency is not only required for proinflammatory cytokine induction but also essential for chemokine expression. Consistently, histology analyses also displayed declining inflammation with less mucosal epithelium damage, characterized by reduced leukocyte infiltration (Fig. 6H). Flow cytometry indicated that the frequencies of colon-infiltrating total immune cells (CD45+), macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+), and neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+) in USP16MKO mice were significantly reduced compared with those in WT mice with DSS challenge (Fig. 6I). However, these differences are not due to the impaired development of macrophages and neutrophils in BM between WT and USP16MKO mice under DSS-induced inflammatory conditions (fig. S5E). We further evaluated the levels of p-p105 and p-IκBα in the infiltrating macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+) by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) assay in a DSS-induced colitis model. Compared to the WT control, the colonic macrophages in USP16MKO mice displayed a low level of p-p105 but no difference in p-IκBα level. These results are consistent with those observations under LPS stimulation in vitro (fig. S5F).

Fig. 6. USP16 deficiency in macrophages alleviates experimental colitis and inflammation-mediated colon carcinogenesis.

(A) CD11b- and CD68-positive colon macrophages were isolated from patients with UC or CD or from healthy donors. qRT-PCR was performed to analyze the USP16 mRNA levels. (B) Immunohistochemical examination of USP16 protein in inflammatory tissue samples of patients with IBD and in healthy samples. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Immunofluorescence images of USP16 and CD68 staining in human colon tissue sections. Scale bar, 50 μm. WT and USP16MKO mice were treated with 3% [(D) and (F) to (I)] or 3.5% (E) DSS (in drinking water) for five continuous days and then supplied with normal drinking water. (D and E) Body weight loss (D) and survival rates (E) of DSS-treated WT and USP16MKO mice. (F to H) Colon length (F), proinflammatory cytokine production (G), and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) histological staining (H) results for day 8 DSS-treated WT and USP16MKO mice (scale bar, 100 mm). (I) FACS analysis results for the total immune cells (CD45+), macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+), and neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+), presented in a representative plot for multiple mice (n = 4). (J) Schematic of mouse treatment with AOM/DSS. The colons of WT and USP16MKO mice were photographed. The numbers of tumors of different sizes were measured. (K) Representative images of Ki-67 staining of colon tumors of WT and USP16MKO mice (scale bar, 50 μM). (L) qRT-PCR assay of cytokine levels in colon tissue of AOM/DSS-treated WT and USP16MKO mice. All qRT-PCR data are presented as the fold induction relative to the Actb mRNA level. Photo credits of (B), (C), (F), (H), (J), and (K): Yu Zhang (Zhejiang University). The data are presented as the means ± SEMs and are representative of at least three independent experiments. The statistical analysis results show the variations among experimental replicates. Two-tailed unpaired t tests were performed. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

To further confirm the critical role of macrophages in DSS-induced colitis, we depleted the macrophages in DSS-treated WT mice with clodronate liposomes, which eliminated macrophages through programmed cell death (fig. S6A). Similar to USP16MKO mice, the WT mice with macrophage depletion displayed significantly reduced severity of colitis, as well as a substantially higher survival ratio (fig. S6B) and a lower body weight loss (fig. S6C) and SCI (fig. S6D). Consistently, longer colons were observed by macroscopic analyses in DSS-induced WT mice after clodronate liposome treatment (fig. S6E). Collectively, these data indicated an essential role of macrophage-specific USP16 in the onset of DSS-induced colitis.

Azoxymethane (AOM)/DSS administration is a well-accepted method for the establishment of colitis-associated colorectal cancer (CRC) models in mice. We next investigated the roles of USP16 in macrophages with regard to the triggering of colitis-associated CRC (42). Given their associated hypoactivation of colon macrophages, USP16MKO mice had fewer and smaller colon tumors than their WT littermates (Fig. 6J). However, USP16MKO mice exhibited similar proliferation rates to colon epithelial cells, as suggested by Ki-67 staining (Fig. 6K), although weak Ki-67 signals were detected in the colons of USP16MKO mice under normal conditions (fig. S6F). In addition, the mRNA levels of various inflammatory cytokines—including Tnf, Il12a, IL12b, Il23a, and Il1b—were decreased in the colon tissues of USP16MKO mice (Fig. 6K). This result indicates a clear pivotal effect of myeloid USP16-mediated canonical NF-κB in experimental colitis model establishment and CRC development.

DISCUSSION

CRC is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide. The development of CRC is a multistep process driven by the accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations that dysregulate the signaling network involved in the growth and survival of IECs (43). Chronic inflammatory conditions, as seen in patients with IBD, create a microenvironment that promotes CRC development and progression (44). DSS-induced colitis has been widely used as an animal model of human UC, an inflammatory condition that greatly increases the risk of colon cancer (45). However, the molecular mechanisms regulating intestinal inflammation and tumorigenesis are still poorly understood. Nevertheless, the transcription factor NF-κB is well recognized for its role in mediating colonic inflammation and tumorigenesis (46). NF-κB is often activated under inflammatory conditions and transactivates genes encoding various inflammatory mediators and factors involved in cell growth and survival. However, since NF-κB is essential for the immune response and various other physiological functions, global inhibition of NF-κB is highly toxic to patients. The inhibition of pathologically activated NF-κB requires a better understanding of the mechanisms mediating NF-κB regulation.

NF-κB activation is mediated by two major signaling pathways: the canonical and noncanonical pathways (9, 42–47). The canonical pathway involves the activation of a MAP3 kinase, Tak1, and its downstream kinase IKKβ, which mediates the degradation of IκBα and the nuclear translocation of RelA/p50 and c-Rel/p50 NF-κB dimers. For the activation of NF-κB signaling, IKKβ is phosphorylated by various inducers, such as TLR agonists, proinflammatory cytokines, and the oncoprotein Tax derived from human T cell leukemia virus 1. IKKβ is stimulated by signals transmitted through cell surface receptors that trigger its phosphorylation at S177 and S181 (48). This phosphorylation leads to a conformational change and kinase activation (14). Previously, IKKβ was reported to undergo K63-linked ubiquitination (49). Mutations in IKKβ at K171 lead to marked increases in kinase activation and K63-linked ubiquitination. These mutations result in persistent signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling activation that is independent of TNF-α or IL-6 stimulation. Furthermore, the K171R mutation was shown to cause constitutive phosphorylation of IKKβ during a screen of K residues in the kinase domain (50). Another report illustrated that IKKβ is polyubiquitinated at K555 by the E3 ligase KEAP1 in TNF-α–stimulated HEK293T cells, resulting in down-regulation of NF-κB signaling dependent on the 26S proteasome (37). In addition to polyubiquitination, IKKβ is conjugated with a single ubiquitin molecule (monoubiquitin) in human cells and activated by TAX, which is mediated by Ro52 (51).

There is a close link among phosphorylation, monoubiquitination, and the biological action of IKKβ. Chronic phosphorylation of IKKβ at S177/S181 leads to monoubiquitination at the T loop-proximal residue K163 (14). Monoubiquitination of IKKβ leads to down-regulation of NF-κB signaling; however, this process has been shown to be disrupted by the deubiquitinase/acetyltransferase YopJ (52). YopJ can acetylate IKKβ on the activation loop, thereby preventing the activation of IKKβ kinase activity, which, in turn, prevents the phosphorylation of IκB and protects IκB from degradation in response to TNF-α (52). IKKβ is also specifically modified with O-GlcNAc (N-acetylglucosamine) at the inactivating phosphorylation site at S733 in p53-deficient cells (53). O-GlcNAcylation of IKKβ is induced by high-glucose conditions and enhances NF-κB activity. IKKβ has also been reported to be a direct target for S-nitrosylation in Jurkat T cells. Endogenous S-nitrosylation on cysteine (C) 179 of IKKβ reduces the activation of IKKβ by TNF-α and inhibits IκB phosphorylation (54, 55). Although previous studies have shown that IKKβ can be modified by a variety of posttranslational modifications, no specific modification of IKKβ associated with p105 phosphorylation has been reported.

In this study, we found that IKKβ is ubiquitinated during activation of the canonical NF-κB signaling pathway. In particular, we have identified the deubiquitinase USP16 as a pivotal regulator of IKKβ ubiquitination and a potent factor promoting intestinal tumorigenesis. Although USP16 has been proven to be an adaptive immune mediator, its in vivo function in the innate immune response has not been clarified because of the lack of a viable animal model. Our results reveal that myeloid-conditional USP16 ablation disrupts the onset of colitis and intestinal tumorigenesis in animal models. We further demonstrated that loss of USP16 specifically causes inactivation of p105 in both BMDMs and MEFs, as indicated by low phosphorylation levels of p105 and low nuclear translocation of p50. These data establish USP16 and USP16-mediated IKKβ ubiquitination as a novel regulatory mechanism of NF-κB signaling and intestinal tumorigenesis and suggest an important role of USP16 in colitis-related CRC pathogenesis. We believe that our study substantially advances the field and has profound implications for therapeutic approaches.

METHODS

Mice and cell lines

USP16fl/fl mice with a B6 background were provided by the Model Animal Resource Information Platform, Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University. USP16fl/fl mice were crossed with Lyz2-Cre mice (from the Jackson laboratory; C57BL/6 background) for the F1 generation, and USP16fl/fl Lyz2-Cre+ [myeloid cell conditional USP16 KO (USP16MKO)] and USP16fl/fl Lyz2-Cre− (control) littermates from the F2 generation were used for the experiments. The outcomes of animal experiments were collected blindly and recorded on the basis of the ear-tag numbers of the experimental mice. The mice were maintained in a specific pathogen–free facility, and all mouse experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang University.

The Nemo−/− MEFs and HEK293T cell lines were provided by S.-c. Sun (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA). Primary MEFs were prepared from the WT and USP16−/− embryos at day 15 and were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

Human specimen analysis

All patient samples were from Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Hangzhou, China). Clinical biopsies were obtained from inflamed and normal tissues of patients with distinct autoimmune diseases and from healthy controls. The diagnosis was based on a standard combination of clinical, endoscopic, histological, and radiological criteria. Disease severity was assessed according to international standard criteria such as the CDAI.

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies targeting USP16 (B-3; 1:500), IKKα (B-8; 1:1000), IKKγ (B-3; 1:1000), IκBα (C-21; 1:1000), p65 (C-20; 1:1000), Lamin B (C-20; 1:1000), ERK (K-23; 1:2000), phospho-ERK (E-4; 1:1000), JNK2 (C-17; 1:1000), p38 (H-147; 1:1000), ubiquitin (P4D1; 1:1000), p105/p50 (E-10; 1:1000), and c-Rel (sc-71; 1:1000), as well as a control rabbit IgG (sc-2027), were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies targeting IKKβ (L570; 1:1000), phospho-IκBα (S32; 9241; 1:1000), phospho-JNK (T180/Y185; 9251; 1:1000), phospho-p38 (T180/Y182; 9211; 1:1000), phospho-IKKα/β (S176/180, 16A6), and phospho-p105 (S933; 18E6; 1:1000) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-actin (C-4; 1:10,000), anti-HA (12CA5), anti-FLAG (M2), horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated anti-HA (3F10), and anti-FLAG (M2) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-CD40-PE (phycoerythrin) (1C10), anti-CD80-APC (allophycocyanin) (16-10A1), and anti-CD86-FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate) (GL1) for costimulatory molecular analysis were purchased from eBioscience. Fluorescence-labeled antibodies are listed in the section describing the flow cytometry and cell sorting procedures.

LPS (derived from Escherichia coli strain 0127: B8) and CpG (2216) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. R848 and polyI:C were purchased from Amersham, and recombinant murine M-CSF was purchased from Peprotech.

Plasmids

HA-tagged IKKα/β/γ, p50, p65, p105, IκBα, ubiquitin, K6, K11, K29, K33, K48, and K63 plasmids in the PRK5 vector were provided by S.-c. Sun. The expression vector for HA-tagged human USP16 was provided by Z. Long (Life Sciences Institute, Zhejiang University, China), and we generated the USP16 C205S mutation plasmid by site-directed mutagenesis with KOD plus polymerase. USP16-WT and USP16-C205S complementary DNA (cDNA) were amplified and inserted into the pCLXSN (green fluorescent protein) retroviral vector and 3× flag-tagged pCMV7 vector. USP16 truncated variants (1-123, 1-333, and 1-621) were subcloned into 3× flag-tagged pCMV7 vectors by PCR. Truncated IKKβ variants (1-300, 1-457, 1-479, 1-736, 1-742, and 1-754) were subcloned into PRK5 vectors. The NBDs of IKKα and IKKβ were deleted via site-directed mutagenesis to generate HA-IKKα/βΔNBD plasmids. Glutathione S-transferase (GST)–USP16, NEMO, p105, and IκBα constructs for prokaryotic expression were generated by subcloning into the pGEX4T-1 vector. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Flow cytometry, cell sorting, and intracellular cytokine staining

Single-cell suspensions from spleens, lymph nodes, or BM were subjected to flow cytometry using CytoFLEX (Beckman Coulter) and the following fluorescence-labeled antibodies from eBioscience: Pacific Blue (PB)–conjugated anti-CD4 and anti-CD11c; PE-conjugated anti-B220, anti–IL-17A, and anti-F4/80; PerCP5.5-conjugated anti-Ly6G; APC-conjugated anti-CD3 and anti-CD62L; APC-CY7–conjugated anti-CD11b and anti-CD8; and FITC-conjugated anti–interferon-γ (IFN-γ), anti-CD44, and anti-Foxp3. For intracellular cytokine staining, T cells were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (0.5 μg/ml) plus ionomycin (1 μg/ml) for 3 hours and monensin (eBioscience, ×1000) for another 3 hours and then subjected to intracellular staining with FITC–IFN-γ and PE–IL-17A.

Histopathology

Intestines were removed from WT or USP16MKO mice, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, stained with hematoxylin and eosin solution, and then examined by light microscopy for histological changes. Two different investigators evaluated and determined the inflammation scores of randomly numbered slides.

ELISA and real-time qRT-PCR

Supernatants of in vitro cell cultures were analyzed via ELISA using a commercial assay system (eBioScience). For qRT-PCR, total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Molecular Research Center Inc.) and subjected to cDNA synthesis using ribonuclease H reverse transcription (Invitrogen) and oligo(dT) primers. qRT-PCR was performed in triplicate using an iCycler sequence detection system (Bio-Rad) and iQTM SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). The expression of individual genes was calculated with a standard curve and normalized to the expression of Actb. The gene-specific PCR primers (all for mouse genes) are shown in table S1.

Immunoblot and immunoprecipitation

Whole-cell lysates or subcellular extracts were prepared by lysing the cells in lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors and immediately subjected to IB analysis and IP. In the IP experiments, we pulled down IKKβ in macrophages by using an IKKβ antibody (anti-IKKβ). For transfection models, an expression vector encoding FLAG-tagged USP16 and truncations were transfected into HEK293 cells along with other expression vectors and then immunoprecipitated by anti-FLAG M2 antibody. The samples were resolved by 8.25% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). After electrophoresis, the separated proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore). For immunoblotting, the PVDF membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk. After incubation with a specific primary antibody, HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was applied. The positive immune reactive signal was detected by ECL (Amersham Biosciences).

In vitro kinase assays

IKKβ kinase was immunoprecipitated in cell lysates of LPS-stimulated macrophages and MEFs by IKKβ antibody and protein A/G-Sepharose. Beads were washed 3× with lysis buffer [20 mM tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 1% Triton X-100] and 2× with kinase assay buffer [50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 20 mM potassium citrate, and 10 mM dithiothreitol]. For kinase reaction in vitro, beads containing IKKβ were incubated with purified substrates (GST-IκBα or p105), 50 μM adenosine 5′-triphosphate, 10× kinase assay buffer, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail at 30°C for 30 min with occasional flicking. All kinase assay reactions were stopped with 5× SDS loading buffer, boiled at 100°C for 5 min, and then subjected to IB analysis.

Ubiquitination assays

HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-IKKβ, Flag-USP16, and Flag-Ubi (WT, K6, K11, K29, K33, K48, and K63) for 36 hours, and BMDMs were starved overnight for preparation. After pretreatment with MG132 (N-carbobenzyloxy-l-leucyl-l-leucyl-l-leucinal) for 2 hours (10 μM for HEK293T) or 1 hour (5 μM for BMDM), cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in two pellet volumes of radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 1% SDS] supplemented with protease inhibitors and 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide. Lysates were sonicated, boiled at 100°C for 5 min, diluted with RIPA buffer containing 0.1% SDS, and then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was incubated with a specific antibody (anti-HA 12CA5 for HEK293T/anti-IKKβ for BMDMs) and protein A-agarose for 4 hours at 4°C. After extensive washing, bound proteins were eluted with 2× SDS sample buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting. The ubiquitinated proteins were detected by IB using anti-ubiquitin (P4D1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti-FLAG-HRP (A8592; Sigma-Aldrich).

Luciferase reporter gene assays

HEK293 cells (2 × 105) were transfected by calcium phosphate precipitation with a firefly luciferase reporter driven by the NF-κB promoter, along with the mentioned cDNA expression vectors and the control Renilla luciferase reporter. At 36 hours after transfection, cells were lysed by 1× Passive Lysis Buffer with violent vibration for 15 min and then collected for dual-luciferase assays (Promega). Firefly luciferase activities were normalized to Renilla luciferase activities.

DSS-induced colitis

For lethality analysis, DSS (molecular mass, 36,000 to 50,000 Da; MP Biomedicals) was added to drinking water 3.5% (w/v) for 6 days followed by 2 days of regular water. Body weight was measured every other day for up to 8 days, and the mice were then sacrificed to enable colon length measurement, histology analysis, and immune cell isolation from the mucosa.

For the colorectal tumorigenesis model, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 10 mg of AOM (A5486, Sigma-Aldrich) per kilogram of body weight. After 6 days, 2% DSS was given in the drinking water for 6 days followed by regular drinking water for 2 weeks. This cycle was repeated twice more with 1.5% DSS, and the mice were sacrificed on day 80.

Colonic macrophages were isolated from colonic cells by FACS sorting using CD11b and F4/80 markers (double positive) as previously described (19). Inflammation cytokine gene expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR.

Macrophage preparation and stimulation

WT or macrophage-specific KO mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and BM cells were flushed from mouse tibias and femurs. BM cells were cultured in DMEM containing 20% FBS supplemented with M-CSF (10 ng/ml) for 5 days. After 5 days of culture, the macrophages were harvested and replated to obtain equal numbers of cells on different plates. For qRT-PCR and RNA-sequencing experiments, 3 × 106 cells per well were placed into a 12-well plate. For the IB experiment, 3 × 107 cells per time point were used.

BMDMs were starved overnight in medium supplemented with 1% FCS before being stimulated with LPS (1 μg/ml for IB experiments and 100 ng/ml for cytokine induction experiments), polyI:C (20 mg/ml), and CpG (2216, 5 mM). Total and subcellular extracts were prepared for IB assays, and total RNA was prepared for qRT-PCR assays.

RNA-sequencing analysis

BMDMs were generated and stimulated as previously described. RNA was purified with the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions and subjected to RNA-sequencing analysis. RNA sequencing was performed by the Life Science Institute Sequencing and Microarray Facility using an Illumina sequencer. The raw reads were aligned to the mm10 reference genome (build mm10) using Tophat2 RNA-sequencing alignment software. The mapping rate was 70% overall across all the samples in the dataset.

DEGs were identified in the count data using the R package DESeq2. Overlapping genes were analyzed for gene ontology biological processes using DAVID. DEGs (fold change of ≥1.5 or ≤1.5) of LPS-activated BMDMs versus nontreated BMDMs were analyzed. Overlapping genes were archived for network analysis. A network of interactions was constructed using STRING 10. Pathway enrichment analysis based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) was performed, and significantly enriched terms based on low P values and false discovery rates were used for further analysis.

Fluorescence microscopy

HEK293T cells were transfected with IKKβ and USP16 WT for 36 hours in a 12-well plate. Cells were stimulated with or without TNF-α (10 ng/ml) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. The sections were rinsed, preincubated with 5% blocking serum in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 1 hour, and then incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C, followed by a 1-hour incubation at room temperature with secondary antibodies. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-IKKβ (H-4; 1:100) from Sigma-Aldrich, anti-USP16 (B-3; 1:100) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and FITC–anti-CD68 from BioLegend. The secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 488–labeled anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa Fluor 546–labeled anti-mouse IgG (1:1000; Invitrogen). Nuclei were costained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Roche). Clinical biopsy tissues were stored at −80°C until they were processed to produce sections of 2 μm in thickness. Sections were processed as described above.

All the samples were imaged on an LSM 710 (Carl Zeiss) confocal microscope outfitted with a Plan-Apochromat 63× oil-immersion objective lens (Carl Zeiss). The data were collected using Carl Zeiss software ZEN (blue edition). Colocalization analyses were performed on 30 cells, and the results were expressed as Pearson’s coefficient (R).

LC-MS/MS analysis

HEK293T cells were plated 1 day before transfection at 3 ×106 cells per 15-cm tissue culture plate. Three plates per sample were transfected with HA-IKKβ. Cells were treated with 10 mM MG132 for 2 hours before lysis. Lysates were collected and immunoprecipitated as previously described.

All proteome samples were analyzed by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using an EASY nLC3000 connected to a Thermo Fisher Scientific Q Exactive HF-X MS system. MS data files were analyzed using MaxQuant software with the integrated Andromeda search engine. Data were searched against the human UniProt database (20,367 entries, release-2019_04) (SwissProt) supplemented with commonly observed contaminants.

Statistics

Data are presented as the means ± SEM. The two-tailed Student’s t test was used to compare the differences between two groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Bonferroni posttest were used for multiple comparisons. The Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test was used for the animal survival assay. P values of <0.05 were considered significant, and the level of significance is indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 6 software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Life Sciences Institute core facilities, Zhejiang University, for technical assistance. We also thank L.-r. Lu and S.-c. Sun for the expression plasmid. Funding: This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFA0800503), the Excellent Young Scientist Fund of NSFC (31822017), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LR19C080001), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771675, 32000628, and 81970484), Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province (2020C03075), and the Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province (2020C03075). Author contributions: Conceptualization, J.J. and Y.-y.L.; methodology, X.-t.M., L.-j.H., and Q.C.; investigation, J.-s.Y., T.H., Y.Z., Y.-n.L., T.-t.W., and J.-y.Z.; writing—original draft, J.J., J.-s.Y., and T.H.; writing—review and editing, J.J., J.-s.Y., and T.H.; visualization, J.J. and Y.-y.L.; supervision, J.J. and Y.-y.L.; funding acquisition, J.J. and Q.C. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: Sequence data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors and have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) BioProject with the primary accession code PRJNA503953.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/7/3/eabc4009/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Sen R., Baltimore D., Multiple nuclear factors interact with the immunoglobulin enhancer sequences. Cell 46, 705–716 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Q., Lenardo M. J., Baltimore D., 30 years of NF-κB: A blossoming of relevance to human pathobiology. Cell 168, 37–57 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayden M. S., Ghosh S., Shared principles in NF-κB signaling. Cell 132, 344–362 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilmore T. D., Introduction to NF-κB: Players, pathways, perspectives. Oncogene 25, 6680–6684 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Napetschnig J., Wu H., Molecular basis of NF-κB signaling. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 42, 443–468 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Q., Verma I. M., NF-κB regulation in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 725–734 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiDonato J. A., Mercurio F., Karin M., NF-κB and the link between inflammation and cancer. Immunol. Rev. 246, 379–400 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker R. G., Hayden M. S., Ghosh S., NF-κB, inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 13, 11–22 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun S.-C., The non-canonical NF-κB pathway in immunity and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17, 545–558 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun S.-C., Deubiquitylation and regulation of the immune response. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 501–511 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J., Huang X., Hao S., Wang Y., Liu M., Xu J., Zhang X., Yu T., Gan S., Dai D., Luo X., Lu Q., Mao C., Zhang Y., Shen N., Li B., Huang M., Zhu X., Jin J., Cheng X., Sun S.-C., Xiao Y., Peli1 negatively regulates noncanonical NF-κB signaling to restrain systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Commun. 9, 1136 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X., Wang Y., Yuan J., Li N., Pei S., Xu J., Luo X., Mao C., Liu J., Yu T., Gan S., Zheng Q., Liang Y., Guo W., Qiu J., Constantin G., Jin J., Qin J., Xiao Y., Macrophage/microglial Ezh2 facilitates autoimmune inflammation through inhibition of Socs3. J. Exp. Med. 215, 1365–1382 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu T., Gan S., Zhu Q., Dai D., Li N., Wang H., Chen X., Hou D., Wang Y., Pan Q., Xu J., Zhang X., Liu J., Pei S., Peng C., Wu P., Romano S., Mao C., Huang M., Zhu X., Shen K., Qin J., Xiao Y., Modulation of M2 macrophage polarization by the crosstalk between Stat6 and Trim24. Nat. Commun. 10, 4353 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Israël A., The IKK complex, a central regulator of NF-kappaB activation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a000158 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chariot A., The NF-κB-independent functions of IKK subunits in immunity and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 19, 404–413 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oeckinghaus A., Hayden M. S., Ghosh S., Crosstalk in NF-κB signaling pathways. Nat. Immunol. 12, 695–708 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salmerón A., Janzen J., Soneji Y., Bump N., Kamens J., Allen H., Ley S. C., Direct phosphorylation of NF-κB1 p105 by the IκB kinase complex on serine 927 is essential for signal-induced p105 proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 22215–22222 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schröfelbauer B., Polley S., Behar M., Ghosh G., Hoffmann A., NEMO ensures signaling specificity of the pleiotropic IKKβ by directing its kinase activity toward IκBα. Mol. Cell 47, 111–121 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin J., Xiao Y., Hu H., Zou Q., Li Y., Gao Y., Ge W., Cheng X., Sun S.-C., Proinflammatory TLR signalling is regulated by a TRAF2-dependent proteolysis mechanism in macrophages. Nat. Commun. 6, 5930 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeon S. G., Kim K. A., Chung H., Choi J., Song E. J., Han S.-Y., Oh M. S., Park J. H., Kim J.-I., Moon M., Impaired memory in OT-II transgenic mice is associated with decreased adult hippocampal neurogenesis possibly induced by alteration in Th2 cytokine levels. Mol. Cells 39, 603–610 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin J., Hu H., Li H. S., Yu J., Xiao Y., Brittain G. C., Zou Q., Cheng X., Mallette F. A., Watowich S. S., Sun S.-C., Noncanonical NF-κB pathway controls the production of type I interferons in antiviral innate immunity. Immunity 40, 342–354 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao Z., Li Y., Wang F., Huang T., Fan K., Zhang Y., Zhong J., Cao Q., Chao T., Jia J., Yang S., Zhang L., Xiao Y., Zhou J.-Y., Feng X.-H., Jin J., Mitochondrial dynamics controls anti-tumour innate immunity by regulating CHIP-IRF1 axis stability. Nat. Commun. 8, 1805 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang T., Gao Z., Zhang Y., Fan K., Wang F., Li Y., Zhong J., Fan H. Y., Cao Q., Zhou J., Xiao Y., Hu H., Jin J., CRL4DCAF2 negatively regulates IL-23 production in dendritic cells and limits the development of psoriasis. J. Exp. Med. 215, 1999–2017 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pai S., Thomas R., Immune deficiency or hyperactivity-Nf-κb illuminates autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 31, 245–251 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang M., Lee A. J., Fitzpatrick L., Zhang M., Sun S.-C., NF-κB1 p105 regulates T cell homeostasis and prevents chronic inflammation. J. Immunol. 182, 3131–3138 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greten F. R., Eckmann L., Greten T. F., Park J. M., Li Z.-W., Egan L. J., Kagnoff M. F., Karin M., IKKβ links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell 118, 285–296 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mina R., Cerrato C., Bernardini A., Aghemo E., Palumbo A., New pharmacotherapy options for multiple myeloma. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 17, 181–192 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perkins N. D., The diverse and complex roles of NF-κB subunits in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 121–132 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai S. Y., Babbitt R. W., Marchesi V. T., A mutant deubiquitinating enzyme (Ubp-M) associates with mitotic chromosomes and blocks cell division. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 2828–2833 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joo H.-Y., Zhai L., Yang C., Nie S., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Chang C., Wang H., Regulation of cell cycle progression and gene expression by H2A deubiquitination. Nature 449, 1068–1072 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang W., Lee Y.-H., Jones A. E., Woolnough J. L., Zhou D., Dai Q., Wu Q., Giles K. E., Townes T. M., Wang H., The histone H2A deubiquitinase Usp16 regulates embryonic stem cell gene expression and lineage commitment. Nat. Commun. 5, 3818 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gu Y., Jones A. E., Yang W., Liu S., Dai Q., Liu Y., Swindle C. S., Zhou D., Zhang Z., Ryan T. M., Townes T. M., Klug C. A., Chen D., Wang H., The histone H2A deubiquitinase Usp16 regulates hematopoiesis and hematopoietic stem cell function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E51–E60 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Z., Yang H., Wang H., The histone H2A deubiquitinase USP16 interacts with HERC2 and fine-tunes cellular response to DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 32883–32894 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adorno M., Sikandar S., Mitra S. S., Kuo A., Nicolis di Robilant B., Haro-Acosta V., Ouadah Y., Quarta M., Rodriguez J., Qian D., Reddy V. M., Cheshier S., Garner C. C., Clarke M. F., Usp16 contributes to somatic stem-cell defects in Down’s syndrome. Nature 501, 380–384 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qian Y., Wang B., Ma A., Zhang L., Xu G., Ding Q., Jing T., Wu L., Liu Y., Yang Z., Liu Y., USP16 downregulation by carboxyl-terminal truncated HBx promotes the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Sci. Rep. 6, 33039 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y., Liu R.-b., Cao Q., Fan K.-q., Huang L.-j., Yu J.-s., Gao Z.-j., Huang T., Zhong J.-y., Mao X.-t., Wang F., Xiao P., Zhao Y., Feng X.-h., Li Y.-y., Jin J., USP16-mediated deubiquitination of calcineurin A controls peripheral T cell maintenance. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 2856–2871 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee D.-F., Kuo H.-P., Liu M., Chou C.-K., Xia W., Du Y., Shen J., Chen C.-T., Huo L., Hsu M.-C., Li C.-W., Ding Q., Liao T.-L., Lai C.-C., Lin A.-C., Chang Y.-H., Tsai S.-F., Li L.-Y., Hung M.-C., KEAP1 E3 ligase-mediated downregulation of NF-κB signaling by targeting IKKβ. Mol. Cell 36, 131–140 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mann M., Jensen O. N., Proteomic analysis of post-translational modifications. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 255–261 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pickart C. M., Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 503–533 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Komander D., Rape M., The ubiquitin code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 203–229 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li T., Morgan M. J., Choksi S., Zhang Y., Kim Y.-S., Liu Z.-g., MicroRNAs modulate the noncanonical transcription factor NF-κB pathway by regulating expression of the kinase IKKα during macrophage differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 11, 799–805 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Robertis M., Massi E., Poeta M. L., Carotti S., Morini S., Cecchetelli L., Signori E., Fazio V. M., The AOM/DSS murine model for the study of colon carcinogenesis: From pathways to diagnosis and therapy studies. J. Carcinog. 10, 9 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arvelo F., Sojo F., Cotte C., Biology of colorectal cancer. Ecancermedicalscience 9, 520 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Terzić J., Grivennikov S., Karin E., Karin M., Inflammation and colon cancer. Gastroenterology 138, 2101–2114.e5 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lukas M., Inflammatory bowel disease as a risk factor for colorectal cancer. Dig. Dis. 28, 619–624 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karin M., NF-kappaB as a critical link between inflammation and cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1, a000141 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun S.-C., Non-canonical NF-κB signaling pathway. Cell Res. 21, 71–85 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delhase M., Hayakawa M., Chen Y., Karin M., Positive and negative regulation of IκB kinase activity through IKKβ subunit phosphorylation. Science 284, 309–313 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carter R. S., Pennington K. N., Arrate P., Oltz E. M., Ballard D. W., Site-specific monoubiquitination of IκB kinase IKKβ regulates its phosphorylation and persistent activation. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 43272–43279 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gallo L. H., Meyer A. N., Motamedchaboki K., Nelson K. N., Haas M., Donoghue D. J., Novel Lys63-linked ubiquitination of IKKβ induces STAT3 signaling. Cell Cycle 13, 3964–3976 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wada K., Niida M., Tanaka M., Kamitani T., Ro52-mediated monoubiquitination of IKKβ down-regulates NF-κB signalling. J. Biochem. 146, 821–832 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mittal R., Peak-Chew S.-Y., McMahon H. T., Acetylation of MEK2 and IκB kinase (IKK) activation loop residues by YopJ inhibits signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 18574–18579 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kawauchi K., Araki K., Tobiume K., Tanaka N., Loss of p53 enhances catalytic activity of IKKβ through O-linked β-N-acetyl glucosamine modification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 3431–3436 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reynaert N. L., Ckless K., Korn S. H., Vos N., Guala A. S., Wouters E. F. M., van der Vliet A., Janssen-Heininger Y. M. W., Nitric oxide represses inhibitory κB kinase through S-nitrosylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 8945–8950 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hess D. T., Matsumoto A., Kim S.-O., Marshall H. E., Stamler J. S., Protein S-nitrosylation: Purview and parameters. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 150–166 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/7/3/eabc4009/DC1