Abstract

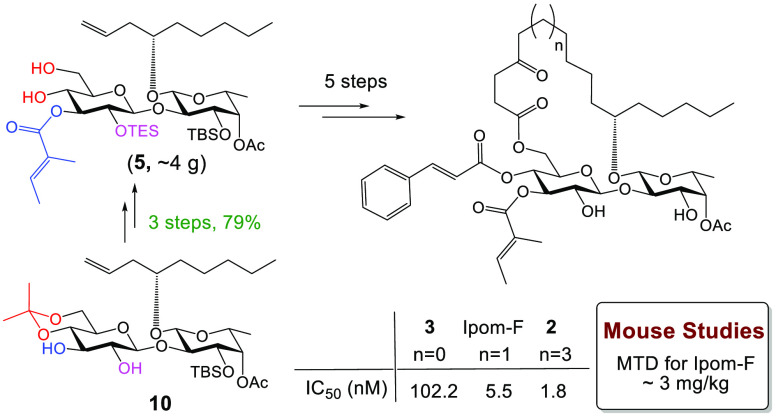

Two new ring-size-varying analogues (2 and 3) of ipomoeassin F were synthesized and evaluated. Improved cytotoxicity (IC50: from 1.8 nM) and in vitro protein translocation inhibition (IC50: 35 nM) derived from ring expansion imply that the binding pocket of Sec61α (isoform 1) can accommodate further structural modifications, likely in the fatty acid portion. Streamlined preparation of the key diol intermediate 5 enabled gram-scale production, allowing us to establish that ipomoeassin F is biologically active in vivo (MTD: ∼3 mg/kg).

Since its discovery between 2005 and 2007,1,2 the ipomoeassin family of resin glycosides (Figure S1) has attracted considerable attention from the synthetic chemistry community3 because ipomoeassins D (Figure S1) and F (Figure 1) exhibited potent cytotoxicity with low nanomolar IC50 values against A2780 human ovarian cancer cells.1,2 To date, three independent total syntheses of ipomoeassin F have been achieved.4−6 Facilitated by the diverse total syntheses, the ensuing medicinal chemistry studies significantly improved our understanding of the structure–activity relationship (SAR) of ipomoeassin F,7−10 leading to the successful development of various functional probes.11 Subsequent chemical proteomics investigations using these molecular probes eventually revealed that ipomoeassin F acts as a potent protein-translocation inhibitor by targeting the pore-forming subunit of the Sec61 complex (Sec61α, protein transport protein Sec61 subunit alpha isoform 1) at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane.11

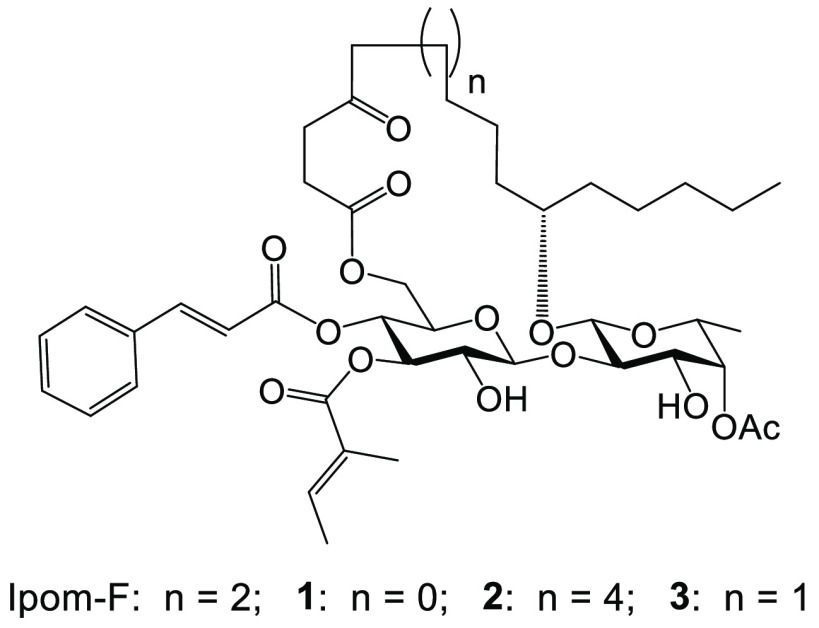

Figure 1.

Structures of ipomoeassin F (Ipom-F) and its ring-size-varying analogues, 1–3.

Besides ipomoeassin F, six other families of chemical entities have been identified as protein-translocation inhibitors targeting Sec61α.12 Interestingly, excluding the synthetic compound eeyarestatin I,13 all the other Sec61α inhibitors belong to one of the distinct classes of macrocyclic natural products with different ring sizes: cotransins (21-membered),14,15 apratoxins (25-membered),16,17 mycolactone (12-membered),18−23 decatransin (30-membered),24 coibamide A (22-membered),25,26 and ipomoeassins (20-membered).1,2 Thus, it appears that a macrocyclic ring is a preferred structural feature among Sec61α-targeting inhibitors. Furthermore, this variation in ring sizes between known inhibitors made us wonder whether the current ring size is already optimal for each macrocycle.27,28 However, no such SAR explorations have been reported. To address how ring size may affect the biological activity of ipomoeassin F, one of the most potent Sec61 inhibitors identified to date, we designed two new analogues (1 and 2, Figure 1) with an 18-membered and 22-membered ring, respectively.

Following our previous synthesis,6 however, we were unable to obtain 4-oxo-6-heptenoic acid S2 (see the inset, Scheme S1), an essential intermediate for synthesizing analogue 1. Consequently, we revised our plan to synthesize the 19-membered ring analogue 3 (Figure 1) instead. Detailed discussion on the design and synthesis of 3 can be found in the Supporting Information.

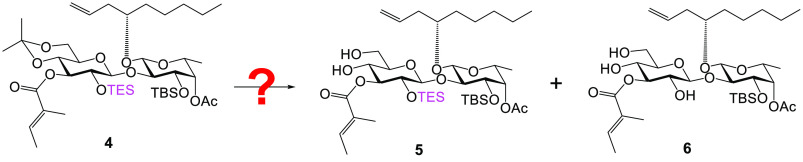

At this stage, the need for gram-scale quantities of S1 for animal studies as well as the synthesis of 22-membered ring analogue 2 prompted an improvement of our established synthesis. To this end, a new diol intermediate 5 (Table 1) was designed to replace S1 (see Scheme S2 in the Supporting Information for a detailed discussion). To synthesize 5 from its precursor 4, it was essential to tackle the challenge of how to chemoselectively and efficiently remove the isopropylidene moiety in the presence of TES (Table 1).

Table 1. Optimization of Chemoselective Removal of Isopropylidenea.

Reaction conditions: 50 mg of 4 in 1 mL solvent at room temperature.

The ratios were determined by 1H NMR analyses of the crude reaction mixture.

Our journey started with camphorsulfonic acid (CSA) in methanol, the common conditions for removing isopropylidene (S9 to S1, Scheme S2). As speculated, isopropylidene was more sensitive to acid-catalyzed hydrolysis, and the desired diol 5 was generated in a greater quantity; however, a significant amount of unwanted triol 6 following TES removal was also detected (entry 1, Table 1). We then thought we might minimize the TES cleavage by slowing down the reaction speed, which could be achieved by decreasing solvent polarity (entry 1, Table S1) or switching to a weaker acid (acetic acid, entries 2–4, Table S1). Unfortunately, such conditions did not result in efficient conversion of 4 to 5. While struggling with multiple failures, we were encouraged by a serendipitous discovery: leaving compound 4 in deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) for about a week led to a clean and almost quantitative formation of 5 (entry 2, Table 1). Hence, we thought that a trace amount of acid in chloroform (CHCl3) might be key to this success. To our delight, performing the reaction in CHCl3 acidified with either aqueous HCl or trifluoroacetic acid (CF3COOH, TFA) showed very promising results (entries 3–6, Table 1). Ultimately, we opted for 5 equiv of TFA in CHCl3 for deisopropylidenation because such conditions best avoided the formation of 6. After a simple workup, the crude product could be applied directly for the next step without further purification.

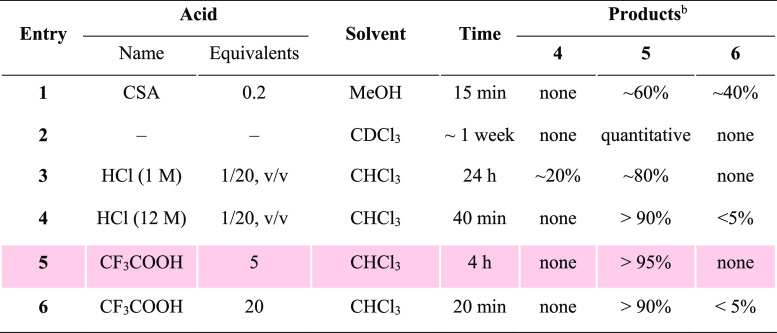

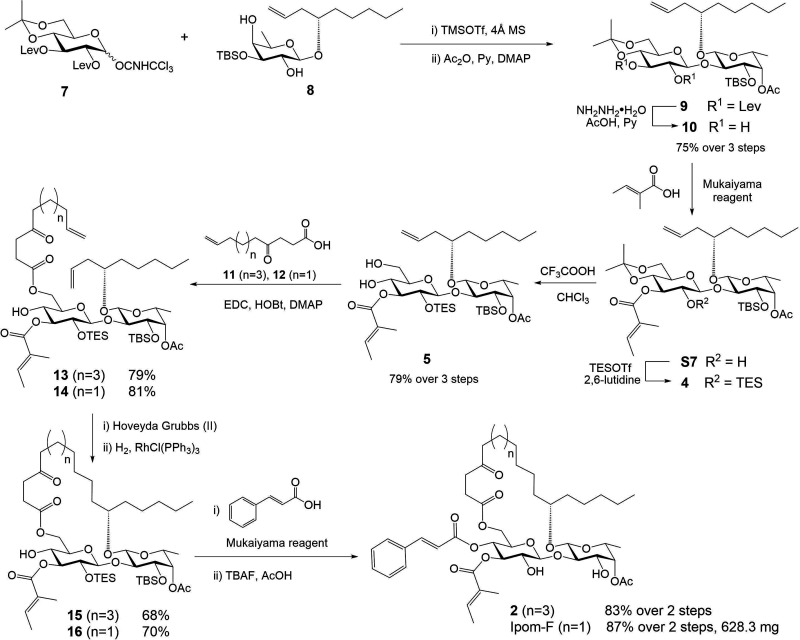

Building upon our previous experience,6,29 we next explored production of precursor 4 from disaccharide 9 which could be efficiently prepared from glucose donor 7 and fucose acceptor 8 (Scheme 1). The 2″,3″-diol intermediate 10 was then obtained by removing the two levulinoyl (Lev) groups. Subsequent regiospecific incorporation of tiglate,9 followed by silylation with TESOTf, afforded 4 in high yield. After 4″,6″-diol 5 was attained from 4, 4-oxo-10-undecenoic acid 11 was introduced to the 6″-OH position in 5 by EDC-mediated coupling. The acquired diene intermediate 13 was then subjected to the ring-closing metathesis conditions, followed by hydrogenation over Wilkinson’s catalyst, to furnish macrocycle 15 with free 4″-OH in good yield. The final 22-membered ring analogue 2 was obtained by a second Mukaiyama esterification with cinnamic acid, followed by removal of the TES and TBS groups with TBAF and AcOH.

Scheme 1. Optimized Total Syntheses of 22-Membered Ring Analogue 2 and Ipomoeassin F (Ipom-F).

With both analogues 2 and 3 in hand, we evaluated their cytotoxicity against two human breast cancer cell lines using the AlamarBlue or MTT assay (Table 2). Compared to ipomoeassin F, decreasing the ring size by one carbon atom caused a significant loss in cytotoxicity (∼18-fold for MDA-MB-231 and ∼33-fold for MCF7). Interestingly, increasing the ring size by two carbon atoms enhanced cytotoxicity by 3–4-fold when compared to that with ipomoeassin F. Taken together, these results demonstrate that it is possible to alter the biological activity of ipomoeassin F by modifying the fatty acid chain and that the cytotoxicity of the analogues tested appears to increase concomitant with structural expansion of the macrocyclic ring.

Table 2. Cytotoxicity (IC50, nM) of Ipomoeassin F and Its Analogues 2 and 3a.

| ring size | MDA-MB-231 | MCF7 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 22 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.7 |

| ipomoeassin F | 20 | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 13.4 ± 2.2 |

| 3 | 19 | 102.2 ± 9.8 | 445.1 ± 13.3 |

The data were obtained from at least three independent experiments.

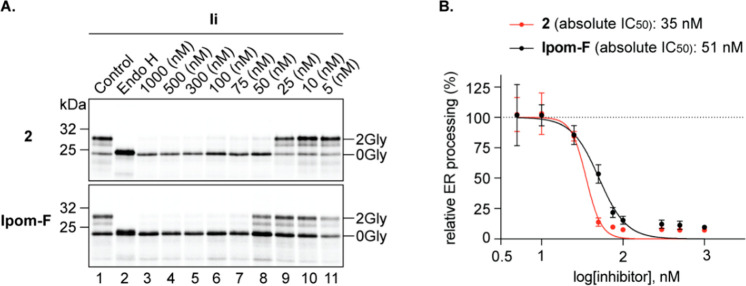

We have previously shown that the strong, reversible binding of ipomoeassin F to Sec61α induces a substantial, yet selective, blockade of Sec61-mediated protein translocation at the ER membrane,11 and we further posited that the subsequent wide-ranging inhibition of cellular protein secretion was the principal molecular basis for the cytotoxicity and cell death conferred by ipomoeassin F.11 Given that ring expansion of ipomoeassin F markedly enhanced its toxicity in cells, we next assessed the effect of analogue 2 on Sec61-mediated protein translocation using an established in vitro system. This approach uses the N-linked glycosylation of proteins as a robust reporter for the translocation of radiolabeled proteins into the lumen ER microsomes.20,30

Based on our previous characterization of the eeyarestatins,31 mycolactone,30 and ipomoeassin F,11 we studied the effects of analogue 2 on the membrane insertion of Ii (short form of HLA class II histocompatibility antigen gamma chain, isoform 2), a type II integral membrane protein. Ii was synthesized in the presence of decreasing (1000–5 nM) concentrations of the ring-expanded analogue 2 and compared to a similar titration using ipomoeassin F (Figure 2A). As judged by the reduction in the level of protein N-glycosylation that is observed (Figure 2A, upper panel, 0Gly versus 2Gly forms), analogue 2 effectively inhibited the membrane integration of Ii in vitro. Strikingly, 50 nM of analogue 2 induces an almost complete blockade in the membrane integration of Ii, whereas, at the same concentration, ipomoeassin F had only a moderate effect as compared to the non-inhibitor control (Figure 2A, cf. lanes 1 and 8 for both panels). Further analysis of the efficiency of Ii membrane integration in the presence of analogue 2 yielded an estimated IC50 value of ∼35 nM (Figure 2B). When compared to our previously reported IC50 value of ∼50 nM for ipomoeassin F,11 this confirms the increased potency of analogue 2 as an inhibitor of Sec61-mediated protein translocation. We attribute the even more pronounced cytotoxic effect of analogue 2 (Table 2) to its global inhibition of a broad range of Sec61-dependent protein substrates that are expressed in cells. Future studies will compare the effects of ipomoeassin F and analogue 2 on the Sec61-dependent translocation of other membrane and secretory proteins.

Figure 2.

Analogue 2 is a more potent inhibitor of Sec61-mediated protein translocation than ipomoeassin F in vitro. (A) Phosphorimages of the membrane-associated products of the type II integral membrane protein Ii synthesized in the presence of 1000–5 nM concentrations of analogue 2 and ipomoeassin F (Ipom-F) were resolved by SDS-PAGE. N-Glycosylated species (2Gly) were distinguished from nonglycosylated (0Gly) products using endoglycosidase H (Endo H, lane 2). (B) Efficiency of Ii membrane integration was estimated using the ratio of signal intensity for the 2Gly/0Gly forms and expressed relative to the control. The IC50 value of analogue 2 was estimated using nonlinear regression as previously described for Ipom-F (51 nM).11 Each phosphorimage depicts experiments performed using a translation master mix, to which Ii mRNA and different compound concentrations were added prior to translation and analysis of the membrane-associated fraction. In B, the analogue 2 data were derived from three independent experiments (n = 3) and compared to that of Ipom-F (previously reported data11).

To date, biological studies of ipomoeassin F and its analogues have been limited to cell-free systems and cultured mammalian cells. Despite high potency in these systems, it remains unclear whether ipomoeassin F would be active when used at the animal level. To evaluate ipomoeassin F in vivo, we first needed a sufficient amount of material. To achieve this goal, we intentionally scaled up early steps during the synthesis of ring-expanded analogue 2 to acquire ∼4 g of diol 5 (Scheme 1). Simply by switching to 9-carbon 4-oxo-8-nonenoic acid 12, ∼0.6 g of ipomoeassin F was obtained, and with enough material in hand, we proceeded to evaluate ipomoeassin F for general toxicity using laboratory mice. Compared to the negative vehicle control, the mice did not survive at doses above 3 mg/kg, whereas doses below 3 mg/kg were generally well-tolerated (see the Experimental Section). Therefore, the in vivo maximum tolerated dose (MTD) for ipomoeassin F is determined as ∼3 mg/kg (6 intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections, once every 3 days). Given the clear in vivo efficacy already demonstrated by analogues of apratoxin A/E32 and coibamide A,33 our data show that future assessment of ipomoeassin F and/or its analogues in tumor xenograft models is warranted.

In conclusion, we developed a highly efficient three-step transformation from 2″,3″-diol 10 to 4″,6″-diol 5 consisting of regioselective esterification, quantitative silylation, and chemoselective deisopropylidenation (Scheme 1), a process that further improves the total synthesis of ipomoeassin F by resulting in an overall yield of 12.4% (previously 3.8%6 and 4.0%9). Furthermore, we have established for the first time that ipomoeassin F is biologically active in vivo, and the MTD is highly valuable for future therapeutic evaluations of ipomoeassin F. Moreover, the synthesis and biological evaluation of analogues 2 and 3 constitute the first ring-size focused SAR exploration among all of the natural macrocyclic inhibitors of Sec61-dependent protein translocation discovered to date. The enhanced potency of the ring-expanded analogue 2 delivers the encouraging message that there is unexplored chemical space in the binding pocket of Sec61α, and the creation of chimeric molecular hybrids between ipomoeassin F and other macrocycles, such as the incorporation of peripheral functionalities in the cyclodepsipeptides, may offer new insights into how small molecule ligands interact with Sec61α at the molecular level.34 This will facilitate the future development of more potent and/or more selective molecules targeting protein biogenesis at the ER.

Experimental Section

General Methods

All chemicals were obtained commercially and were used as received. Unless noted otherwise, all reactions were conducted in oven-dried glassware under an inert atmosphere (nitrogen/argon). Reactions were monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC), and TLC plates were visualized under UV light (254 nm) or by charring with 5% (v/v) H2SO4 in EtOH. Purification of crude products by column chromatography was carried out on silica gel (230–450 mesh). All 1D and 2D NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker 300 or 400 MHz spectrometer. An Autopol III automatic polarimeter was employed to measure optical rotations at 25 ± 1 °C for solutions in a 1.0 dm cell. Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry by electrospray ionization was utilized to analyze high-resolution mass spectra (HRMS).

Synthetic Procedures and Analytical Data

General Procedure for Synthesis of 4-Oxo-alkenoic Acids

To a combination of iodine (trace amount), magnesium turnings (11 mmol), and anhydrous THF (10 mL) was added a small portion of bromoalkene (1 mmol), and the mixture was heated to trigger the radical reaction. Then the rest of the bromoalkene (10 mmol) was added dropwise in 30 min, and the mixture was refluxed for 3 h until the magnesium turnings were largely consumed to form the Grignard reagent. The reaction mixture was cooled to rt and then was added dropwise in 30 min to a cold (−20 °C) solution of succinic anhydride (10 mmol) and CuI (1 mmol) in anhydrous THF (10 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at −20 °C for 1 h and then was allowed to warm to ambient temperature and stirred overnight. TLC (silica, 1:4 EtOAc–hexanes with 0.5% AcOH) showed the reaction was complete. HCl (1 M, 10 mL) was added to quench the reaction, and resulting mixture was stirred for 10 min followed by evaporation in vacuo to remove THF. The aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL × 2 times), and the combined organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:6 → 1:3 containing 0.5% AcOH) to give 4-oxo-alkenoic acids.

4-Oxo-7-octenoic Acid S3:

White solid; yield 12%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.99 (br, 1H, COOH), 5.90–5.68 (m, 1H, CH2=CH−), 5.11–4.88 (m, 2H, CH2=CH−), 2.76–2.67 (m, 2H), 2.66–2.58 (m, 2H), 2.55 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 2.38–2.27 (m, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 208.0, 178.8, 136.8, 115.3, 41.6, 36.8, 27.7, 27.6. The 1H, 13C{1H} NMR data were in accordance with the literature.35−37

4-Oxo-10-undecenoic Acid 11:

White solid; yield 21%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.65 (br, 1H, COOH), 5.90–5.70 (m, 1H, CH2=CH−), 5.11–4.85 (m, 2H, CH2=CH−), 2.78–2.68 (m, 2H), 2.66–2.59 (m, 2H), 2.45 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 2.08–2.00 (m, 2H), 1.66–1.55 (m, 2H), 1.46–1.24 (m, 4H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 208.9, 178.7, 138.8, 114.4, 42.6, 36.7, 33.5, 28.6, 28.6, 27.7, 23.6.

4-Oxo-8-nonenoic Acid 12:

White solid; yield 15–30%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.03 (br, 1H, COOH), 5.90–5.68 (m, 1H, CH2=CH−), 5.15–4.92 (m, 2H, CH2=CH−), 2.82–2.70 (m, 2H), 2.67–2.59 (m, 2H), 2.46 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 2.15–1.93 (m, 2H), 1.80–1.62 (m, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 208.7, 178.6, 137.9, 115.3, 41.8, 36.8, 33.0, 27.7, 22.7. The 1H, 13C{1H} NMR data were in accordance with the literature.35

Compound S5

To a cooled (0 °C) solution of S1 (186 mg, 0.232 mmol), EDC (88.8 mg, 0.462 mmol), HOBt (70.9 mg, 0.463 mmol), and DMAP (113.2 mg, 0.926 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (20 mL) was added 4-oxo-7-octenoic acid S3 (see Supporting Information) (41.6 mg, 0.266 mmol). The reaction was allowed to warm to ambient temperature and stirred overnight. At this point, TLC (silica, 1:3 EtOAc–hexanes) showed the reaction was complete. The mixture was successively washed with aqueous 1 M HCl (20 mL) and saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (20 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:4 → 1:2) to give diene S5 (185 mg, 85%): [α]D25 +8.2 (c 1 CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.98–6.90 (m, 1H, Me–CH=C(Me)–C=O), 6.20–6.05 (m, 1H, CH2=CH–CH2−), 5.86–5.73 (m, 1H, CH2=CH–CH2−), 5.15–4.90 (m, 7H, 2 × CH2=CH–CH2–, H-1-Glup, H-3-Glup, H-4-Fucp), 4.43 (dd, J = 11.6, 3.6 Hz, 1H, H-6-Glup), 4.37 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, H-1-Fucp), 4.32 (dd, J = 12.0, 2.0 Hz, 1H, H-6-Glup), 4.06 (t, J = 8.8, 8.0 Hz, 1H, H-2-Fucp), 3.89 (dd, J = 9.2, 4.0 Hz, 1H, H-3-Fucp), 3.68–3.61 (m, 2H, H-5-Fucp, −CH2–CH–CH2−), 3.60–349 (m, 2H, H-2-Glup, H-4-Glup), 3.47–3.39 (m, 1H, H-5-Glup), 2.91 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H, OH), 2.85–2.50 (m, 6H), 2.40–2.26 (m, 4H), 2.13 (s, 3H, CH3–C=O), 1.89–1.77 (m, 6H, CH3–CH=C(CH3)–C=O), 1.64–1.46 (m, 2H), 1.42–1.22 (m, 6H), 1.14 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H, H-6-Fucp), 0.93–0.85 (m, 12H), 0.80 (s, 9H), 0.15 (s, 3H, CH3–Si), 0.10 (s, 6H, 2 × CH3–Si), 0.02 (s, 3H, CH3–Si); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 207.0, 173.1, 170.9, 169.0, 138.5, 136.9, 136.1, 128.2, 116.3, 115.3, 100.8, 99.9, 80.7, 78.7, 74.15, 74.09, 73.8, 73.7, 73.4, 70.1, 68.9, 63.4, 41.7, 38.6, 37.1, 34.4, 31.9, 27.7, 27.6, 25.82 (×3C), 25.81 (×3C), 24.6, 22.6, 22.59, 21.0, 18.1, 17.6, 16.7, 14.4, 14.0, 12.0, −3.2, −4.0, −4.3, −5.3; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C48H84NaO14Si2 [M + Na]+ 963.5292, found 963.5291.

Compound S6

At room temperature, second generation Hoveyda–Grubbs catalyst (17.0 mg, 0.027 mmol) was added in one portion to a solution of diene S5 (170 mg, 0.181 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (100 mL). After the reaction mixture was refluxed overnight, TLC (silica, 1:2 EtOAc–hexanes) showed the reaction was complete. The solution was cooled and then concentrated. The acquired crude product was purified by flash chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:2 → 1:1) to give cycloalkene isomers (124.0 mg, 75%) as a colorless syrup. Subsequently, the obtained cycloalkene was dissolved in EtOH (4 mL), and Wilkinson’s catalyst (25.3 mg, 0.027 mmol) was added in one portion to the solution at room temperature. After being stirred under an atmosphere of hydrogen (1 atm) overnight, the reaction mixture was filtered through a pad of Celite, followed by washing with EtOAc. The resulting filtrate was concentrated, and the yielded crude product was purified by flash chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:5 → 1:3) to give S6 (100.7 mg, 81%) as a white foam: [α]D25 +3.3 (c 1 CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.99–6.90 (m, 1H, Me–CH–C(Me)–C=O), 5.05 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H-1-Glup), 5.02–4.93 (m, 2H, H-3-Glup, H-4-Fucp), 4.80–4.68 (m, 1H, H-6-Glup), 4.32 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H-1-Fucp), 4.13 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-2-Fucp), 4.09–4.00 (m, 1H, H-6-Glup), 3.89 (dd, J = 8.8, 3.2 Hz, 1H, H-3-Fucp), 3.70–3.61 (m, 1H, H-5-Fucp), 3.52–3.31 (m, 4H, H-2-Glup, H-4-Glup, H-5-Glup, −CH2–CH–CH2−), 2.96 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, OH), 2.94–2.78 (m, 2H), 2.60–2.38 (m, 4H), 2.11 (s, 3H, CH3–C=O), 1.90–1.80 (m, 6H, CH3–CH–C(CH3)–C=O), 1.79–1.62 (m, 4H), 1.60–1.21 (m, 12H), 1.13 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H, H-6-Fucp), 0.94–0.84 (m, 12H), 0.81 (s, 9H), 0.17 (s, 3H, CH3–Si), 0.17 (s, 3H, CH3–Si), 0.10 (s, 3H, CH3–Si), 0.01 (s, 3H, CH3–Si); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 210.2, 172.5, 170.9, 168.3, 138.2, 128.4, 102.5, 100.6, 83.2, 78.2, 74.9, 74.4, 73.9, 73.6, 73.5, 68.4, 62.9, 42.2, 36.7, 35.4, 33.8, 32.0, 29.3, 27.9, 25.8 (×6C), 24.9, 23.9, 23.2, 22.6, 21.0, 18.1, 17.6, 16.7, 14.4, 14.0, 12.1, −3.3, −3.9, −4.1, −5.3; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C46H82NaO14Si2 [M + Na]+ 937.5130, found 937.5135.

19-Membered Analogue 3

2-Chloro-1-methylpyridinium iodide (CMPI, 15.6 mg, 0.061 mmol), N,N-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP, 9.3 mg, 0.076 mmol), and Et3N (21 μL, 0.15 mmol) were added to a solution of S6 (28.0 mg, 0.031 mmol) and cinnamic acid (6.8 mg, 0.046 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (3 mL) at 0 °C. The reaction was allowed to warm to ambient temperature and stirred for 3 h. At this point, TLC (silica, 1:3 EtOAc–hexanes) showed the reaction was complete. The mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL) and successively washed with aqueous 1 M HCl (20 mL) and saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (20 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was used directly for the final deprotection without further purification. To a solution of the obtained residue in THF (2 mL) were added AcOH (160 μL, 2.8 mmol) and TBAF (1 M solution in THF, 1.40 mL, 1.40 mmol) at rt. The reaction was stirred at rt for 36 h. At this point, TLC (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:1) showed the reaction was complete. The mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL) and successively washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (20 mL) and brine (20 mL) and dried over Na2SO4. Evaporation of the solvent followed by purification of the residue by column chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:2 → 1:1) to give 3 (19.8 mg, 79% over two steps) as a white foam: [α]D25 −71.8 (c 0.5 CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.61 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H, Ph–CH=C−), 7.58–7.45 (m, 2H, 2 × ArH), 7.43–7.35 (m, 3H, 3 × ArH), 6.95–6.85 (m, 1H, Me–CH–C(Me)–C=O), 6.32 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H, Ph–CH=CH−), 5.31 (t, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H, H-4-Glup), 5.18–5.12 (m, 1H, H-4-Fucp), 5.07 (t, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H, H-3-Glup), 4.80 (dd, J = 12.8, 2.8 Hz, 1H, H-6-Glup), 4.63 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H-1-Glup), 4.37 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H-1-Fucp), 3.90 (dd, J = 9.6, 3.6 Hz, 1H, H-3-Fucp), 3.88–3.81 (m, 1H, H-6-Glup), 3.78–3.60 (m, 4H, H-2-Glup, H-5-Glup, H-2-Fucp, H-5-Fucp), 3.58–3.46 (m, 1H, −CH2–CH–CH2−), 3.21–3.08 (m, 1H), 2.86–2.73 (m, 1H), 2.68–2.56 (m, 2H), 2.54–2.43 (m, 1H), 2.35–2.25 (m, 1H), 2.18 (s, 3H, CH3–C=O), 1.80–1.68 (m, 8H), 1.67–1.55 (m, 2H), 1.53–1.11 (m, 15H), 0.89 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 210.2, 171.7, 170.8, 169.3, 165.4, 146.1, 140.2, 134.0, 130.6, 128.9 (×2C), 128.3 (×2C), 127.5, 116.6, 106.7, 101.8, 84.5, 81.4, 76.7, 74.5, 72.8 (×2C), 72.7, 68.8, 66.4, 61.0, 42.4, 36.6, 35.8, 35.5, 31.8, 29.1, 29.0, 25.1, 25.0, 24.9, 22.6, 20.9, 16.3, 14.6, 14.1, 11.9. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C43H60NaO15 [M + Na]+ 839.3825, found: 839.3833.

Glucosyl donor 7

7 was prepared from d-glucose through 7 steps with an overall yield of 42.8% (see the Supporting Information for the synthetic scheme). d-Glucose (40.0 g, 222 mmol) was added to a mixture of Ac2O (170 mL) and HClO4 (1.3 mL) at 0 °C over 20 min. The reaction mixture was stirred at the same temperature for 1 h. Pyridine (3.5 mL) was added at 0 °C to quench the reaction. The solvents were evaporated in vacuo, and then coevaporated with toluene. Then to a cold (0 °C) solution of the obtained residue and ethanethiol (19.2 mL, 267 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (500 mL) was added dropwise boron trifluoride diethyl etherate (110 mL, 889 mmol) in 30 min. Then, the mixture was stirred at rt for 6 h. The reaction mixture was poured into crushed ice, and the excess boron trifluoride diethyl etherate was neutralized by the careful addition of 2 M aq. NaOH solution. The organic layer was washed with brine, dried (Na2SO4), and concentrated in vacuo to provide a yellowish syrup. To a solution of yellowish syrup in MeOH was added sodium methoxide (1.2 g). The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 h at rt. Neutralization of the reaction mixture with acidic ion-exchange resin (Amberlite IR-120 H+) and the organic phase was concentrated. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (EtOAc–MeOH, 10:1) to give S10 (37.8 g, 76% over three steps) as a white solid. To a solution of S10 (37.8 g, 169 mmol) in DMF (300 mL) containing TsOH·H2O (0.64 g, 3.4 mmol) was added 2-methoxypropene (19.4 mL, 202 mmol) under nitrogen atmosphere. The resulting mixture was stirred for 6 h at rt until completion (EtOAc–hexanes, 1:1). The reaction was quenched with Et3N (2 mL) and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:2 → 2:1) to give compound S11(38) (38.1 g, 86%) as a colorless syrup. DCC (37.1 g, 180 mmol) was added to a 0 °C CH2Cl2 (200 mL) solution of S11 (19.8 g, 74.9 mmol), levulinic acid (20.9 g, 180 mmol) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (1.83 g, 15.0 mmol). The reaction was allowed to warm to ambient temperature and stirred overnight. The reaction mixture was diluted with ether (400 mL) and hexanes (200 mL), stirred for 20 min then filtered through a pad of Celite using ether (50 mL) as the eluent and the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo. To a 0 °C solution of the residue in acetone (900 mL) and water (100 mL) was added NBS (40.0 g, 225 mmol) and the reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min before quenched with sat. NaHCO3. The mixture was concentrated in vacuo, dissolved in CH2Cl2 and washed with sat. NaHCO3. The organic layer was dried (Na2SO4), concentrated in vacuo and the residue was purified by column chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 2:1) to afford the desired hemiacetal S12 (24.5 g, 78.4% over two steps). To a solution of the obtained hemiacetal (24.4 g, 58.6 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (200 mL) was added trichloroacetonitrile (23.5 mL, 23.4 mmol), and 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undecene (DBU) (0.87 mL, 5.9 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 2 h at rt and then was concentrated. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 2:1) to afford the glucosyl donor 7 (27.6 g, 84%). [α]D25 +50.2 (c 1 CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.71, 8.64 (2s, 1H, OCNHCCl3), 6.44 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H, H-1), 5.49 (t, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.12 (dd, J = 10.0, 4.0 Hz, 1H, H-2), 3.98–3.88 (m, 2H, H-5, H-6), 3.86–3.70 (m, 2H, H-4, H-6), 2.88–2.46 (m, 8H, 2 × CH3–CO(CH2)2CO), 2.17 (s, 3H, CH3-CO(CH2)2CO), 2.15 (s, 3H, CH3-CO(CH2)2CO), 1.49, 1.48 (2s, 3H, (CH3)2C), 1.40, 1.39 (2s, 3H, (CH3)2C). The 1H NMR data were in accordance with the literature.7

Fucosyl acceptor 8

8 was prepared from D-fucose through 6 steps with an overall yield of 42.0% following the procedure we developed previously (see the Supporting Information for the synthetic scheme).9

Disaccharide diol 10

A mixture of donor 7 (8.70 g, 15.5 mmol), acceptor 8 (5.68 g, 14.1 mmol), and 4 Å molecular sieves (7 g) in anhydrous, redistilled CH2Cl2 (200 mL) was stirred under an N2 atmosphere for 30 min and then cooled to −50 °C. TMSOTf (255 μL, 1.41 mmol) was added to the mixture. Then the reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min, at the end of which time TLC (silica, 1:2 EtOAc–hexanes) showed the reaction was complete. Then the reaction mixture was quenched with pyridine (0.5 mL) and filtered. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo and the residue was used without further purification for the next step. The residue was dissolved in pyridine (80 mL) followed by addition of Ac2O (30 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at rt overnight. The mixture was successively washed with aqueous 1 M HCl (200 mL), saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (200 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (200 mL), and the combined organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, concentrated in vacuo and the residue was used without further purification for the following Lev deprotection step. To a solution of the obtained residue in CH2Cl2 (200 mL) was added a premade cocktail (hydrazine monohydrate/AcOH/pyridine) 120 mL and the reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 1 h, at which point, TLC (silica, 1:2 EtOAc–hexanes) showed the reaction was complete. The reaction was quenched with acetone (10 mL), washed with brine (100 mL). The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (EtOAc–hexanes, 1:3 → 1:2) to give 10 (6.81 g, 75% over three steps) as a white solid.

Preparation of hydrazine monohydrate/AcOH/pyridine cocktail: 5 mL hydrazine monohydrate was added dropwise to a cold solution of AcOH and pyridine (mol ratio 1/1, total 150 mL).

Diol 10

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.94–5.75 (m, 1H, CH2=CH-CH2−), 5.14–4.95 (m, 3H, CH2=CH–CH2–, H-4-Fucp), 4.62 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H-1-Glup), 4.40 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H-1-Fucp), 3.95–3.77 (m, 4H, 2 × H-6-Glup, H-2-Fucp, H-3-Fucp), 3.76–3.54 (m, 5H, H-3-Glup, H-4-Glup, H-5-Fucp, −CH2–CH-CH2–, OH), 3.48–3.38 (m, 1H, H-2-Glup), 3.36–3.25 (m, 1H, H-5-Glup), 2.57 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H, OH), 2.40–2.22 (m, 2H), 2.13 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 3H), 1.58–1.47 (m, 5H, (CH3)2C), 1.45 (s, 3H, (CH3)2C), 1.40–1.20 (m, 6H), 1.14 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H, H-6-Fucp), 0.93–0.85 (m, 12H), 0.18 (s, 3H, CH3–Si), 0.16 (s, 3H, CH3–Si); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.7, 134.6, 116.9, 104.5, 101. 4, 99.8, 79.3, 79.2, 76.6, 73.2, 72.9, 72.7, 72.6, 68.8, 68.3, 62.1, 38.1, 34.0, 31.8, 29.0, 25.9(3), 24.3, 22.6, 20.8, 19.0, 17.8, 16.4, 14.0, −4.4, −4.7. The 1H, 13C NMR data were in accordance with the literature.7

Synthesis of diol 5 through an efficient three step conversion

2-Chloro-1-methylpyridinium iodide (CMPI, 2.38 g, 9.32 mmol), N,N-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP, 1.52 g, 12.4 mmol) and Et3N (4.3 mL, 31.1 mmol) were added to a solution of 10 (4.02 g, 6.21 mmol) and tiglic acid (684 mg, 6.84 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (150 mL) at 0 °C. The reaction was allowed to warm to ambient temperature and stirred for 6 h. At this point, TLC (silica, 1:3 EtOAc–hexanes) showed the reaction was complete. To the reaction mixture was then added 2,6-lutidine (3.60 mL, 31.1 mmol) and TESOTf (2.81 mL, 12.4 mmol) at rt. The reaction was complete after stirred for 2 h based on TLC (silica, 1:6 EtOAc–hexanes). The mixture was successively washed with aqueous 1 M HCl (150 mL), saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (150 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with CH2Cl2 (200 mL), and the combined organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, concentrated in vacuo. The residue was then dissolved in CHCl3 (200 mL) and CF3COOH (2.40 mL, 31.1 mmol) was added at rt. The reaction mixture was stirred for 4 h, at which point, TLC (silica, 1:2 EtOAc–hexanes) showed the reaction was complete. Et3N (8.6 mL, 62.1 mmol) was added to quench the reaction. Evaporation of the solvent followed by purification of the residue by flash chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:3 → 1:1) to give compound 5 (3.96 g, 79% over three steps) as a white foam. [α]D25 +9.6 (c 1 CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.00–6.89 (m, 1H, Me–CH=C(Me)-C = O), 6.09–5.92 (m, 1H, CH2=CH-CH2−), 5.15–4.98 (m, 3H, CH2=CH–CH2–, H-4-Fucp), 4.97 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, H-1-Glup), 4.92 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, H-3-Glup), 4.28 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H-1-Fucp), 3.99 (t, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H, H-2-Fucp), 3.96–3.83 (m, 2H, H-6-Glup, H-3-Fucp), 3.81–3.73 (m, 1H, H-6-Glup), 3.70–3.58 (m, 3H, H-4-Glup, H-5-Fucp, −CH2–CH-CH2−), 3.52 (dd, J = 8.8, 7.6 Hz, 1H, H-2-Glup), 3.41–3.32 (m, 1H, H-5-Glup), 2.69 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 2.37–2.25 (m, 3H), 2.14 (s, 3H, CH3-C = O), 1.90–1.79 (m, 6H, CH3-CH–C(CH3)-C = O), 1.67–1.45 (m, 2H), 1.40–1.23 (m, 6H), 1.14 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H, H-6-Fucp), 0.96–0.83 (m, 21H, (CH3)3C–Si, (CH3CH2)3–Si, lipid–CH3), 0.65–0.51 (m, 6H, (CH3CH2)3–Si), 0.16 (s, 3H, CH3–Si), 0.11 (s, 3H, CH3–Si); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.9, 169.0, 138.6, 135.5, 128.2, 116.3, 101.2, 100.5, 80.7, 79.1, 75.3, 74.5, 74.0, 73.5, 73.3, 70.6, 68.9, 62.2, 38.4, 34.3, 31.8, 25.8 (×3C), 24.6, 22.6, 21.0, 17.7, 14.4, 14.0, 12.1, 6.8 (×3C), 5.0 (×3C), −4.1, −4.3; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C40H74NaO12Si2 [M + Na]+ 825.4612, found 825.4610.

Compound 14

To a cooled (0 °C) solution of 5 (3.68 g, 4.58 mmol), EDC (1.76 g, 9.16 mmol), HOBT (1.40 g, 9.16 mmol), and DMAP (2.24 g, 18.3 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (100 mL) was added 4-oxonon-8-eneoic acid 12 (897 mg, 5.27 mmol). The reaction was allowed to warm to ambient temperature and stirred overnight. At this point, TLC (silica, 1:3 EtOAc–hexanes) showed the reaction was complete. The mixture was successively washed with aqueous 1 M HCl (50 mL) and saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (50 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:4 → 1:2) to give diene 14 (3.54 g, 81%): [α]D25 +4.5 (c 1 CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.00–6.88 (m, 1H, Me–CH–C(Me)–C=O), 6.22–6.05 (m, 1H, CH2=CH–CH2−), 5.84–5.68 (m, 1H, CH2=CH–CH2−), 5.18–4.85 (m, 7H, 2 × CH2=CH–CH2–, H-1-Glup, H-3-Glup, H-4-Fucp), 4.43 (dd, J = 12.0, 4.0 Hz, 1H, H-6-Glup), 4.38–4.23 (m, 2H, H-1-Fucp, H-6-Glup), 4.00 (t, J = 9.2, 7.6 Hz, 1H, H-2-Fucp), 3.89 (dd, J = 9.2, 3.6 Hz, 1H, H-3-Fucp), 3.68–3.59 (m, 2H, H-5-Fucp, −CH2–CH–CH2−), 3.58–3.47 (m, 2H, H-2-Glup, H-4-Glup), 3.46–3.38 (m, 1H, H-5-Glup), 2.92 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H, OH), 2.83–2.51 (m, 4H), 2.45 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.35–2.26 (m, 2H), 2.13 (s, 3H, CH3–C=O), 2.09–2.02 (m, 2H), 1.87 (s, 3H, CH3–CH–C(CH3)–C=O), 1.82 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH3–CH–C(CH3)–C=O), 1.73–1.48 (m, 4H), 1.40–1.21 (m, 6H), 1.13 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H, H-6-Fucp), 0.95–0.72 (m, 21H, (CH3)3C–Si, (CH3CH2)3–Si, lipid–CH3), 0.63–0.52 (m, 6H, 3 × CH3CH2–Si), 0.15 (s, 3H, CH3–Si), 0.10 (s, 3H, CH3–Si); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 208.6, 173.2, 170. 9, 168.7, 138.4, 137.8, 136.2, 128.2, 116.0, 115.3, 100.9, 100.3, 80.8, 78.6, 74.1, 74.2, 73.9, 73.5, 73.4, 69.9, 68.9, 63.3, 41.8, 38.5, 37.1, 34.4, 33.0, 31.9, 27.8, 25.8 (×6C), 24.6, 22.7, 22.6, 21.0, 17.6, 16.7, 14.4, 14.0, 12.0, 6.8, 5.0, −4.2, −4.3; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C49H86NaO14Si2 [M + Na]+ 977.5449, found 977.5445.

Compound 16

At room temperature, second generation Hoveyda–Grubbs catalyst (350 mg, 0.56 mmol) was added in one portion to a solution of diene 14 (3.54 g, 3.71 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (1.8 L). After the reaction mixture was refluxed overnight, TLC (silica, 1:2 EtOAc–hexanes) showed the reaction was complete. The solution was cooled and then concentrated. The acquired crude product was purified by flash chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:2 → 1:1) to give cycloalkene isomers (3.23 g, 94%) as a colorless syrup. Subsequently, the obtained cycloalkene was dissolved in EtOH (25 mL), and Wilkinson’s catalyst (645 mg, 0.70 mmol) was added in one portion to the solution at room temperature. After being stirred under an atmosphere of hydrogen (1 atm) overnight, the reaction mixture was filtered through a pad of Celite, followed by washing with EtOAc. The resulting filtrate was concentrated, and the yielded crude product was purified by flash chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:5 → 1:3) to give 16 (2.40 g, 74%) as a colorless syrup: [α]D25 +3.1 (c 1 CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.02–6.91 (m, 1H, Me–CH–C(Me)–C=O), 5.05–4.94 (m, 3H, H-1-Glup, H-3-Glup, H-4-Fucp), 4.85–4.74 (m, 1H, H-6-Glup), 4.38 (br, 1H, H-1-Fucp), 4.15–4.08 (m, 1H, H-6-Glup), 4.07–4.00 (m, 1H, H-2-Fucp), 3.98–3.89 (m, 1H, H-3-Fucp), 3.72–3.64 (m, 1H, H-5-Fucp), 3.56 (br, 1H, H-5-Glup), 3.49–3.36 (m, 3H, H-2-Glup, H-4-Glup, −CH2–CH–CH2−), 3.15 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H, OH), 3.00–2.87 (m, 1H), 2.75–2.55 (m, 3H), 2.52–2.43 (m, 1H), 2.39–2.25 (m, 1H), 2.11 (s, 3H, CH3–C=O), 1.92–1.82 (m, 6H, CH3–CH–C(CH3)–C=O), 1.81–1.72 (m, 1H), 1.71–1.22 (m, 17H), 1.13 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H, H-6-Fucp), 0.95–0.82 (m, 18H), 0.65–0.50 (m, 6H, 3 × CH3CH2–Si), 0.17 (s, 3H, CH3–Si), 0.12 (s, 3H, CH3–Si); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 210.2, 172.5, 170.9, 168.1, 137.8, 128.5, 101.1, 100.5, 81.7, 78.1, 74.5, 74.1 (×2C), 73.7 (×2C), 69.0, 68.8, 63.5, 41.9, 37.2, 34.9, 33.4, 32.0, 29.7, 29.1, 28.6, 28.3, 25.8, 25.0, 24.6, 23.5, 22.6, 21.0, 17.7, 16.7, 14.4, 14.1, 12.1, 6.9 (×6C), 5.0 (×3C), −4.2, −4.3; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C47H84NaO14Si2 [M + Na]+ 951.5292, found 951.5290.

Ipomoeassin F

2-Chloro-1-methylpyridinium iodide (CMPI, 330.0 mg, 1.29 mmol) and N,N-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP, 263.0 mg, 2.15 mmol) were added to a solution of 16 (800 mg, 0.861 mmol) and cinnamic acid (153 mg, 1.03 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (20 mL) at 0 °C. The reaction was allowed to warm to ambient temperature and stirred for 6 h. At this point, TLC (silica, 1:2 EtOAc–hexanes) showed the reaction was complete. The mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (50 mL) and successively washed with aqueous 1 M HCl (50 mL) and saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (50 mL) and dried over Na2SO4. The solvents were evaporated, and the residue was used directly for the final deprotection without further purification. To a solution of the obtained residue in THF (10 mL) were added AcOH (1.4 mL, 24.8 mmol) and TBAF (1 M solution in THF, 12.4 mL, 12.4 mmol) at rt. The reaction was stirred at rt for 12 h. At this point, TLC (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:1) showed the reaction was complete. The mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (100 mL) and successively washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (50 mL) and brine (50 mL) and dried over Na2SO4. Evaporation of the solvent followed by purification of the residue by column chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:2 → 1:1) to give ipomoeassin F (628.3 mg, 87% over two steps) as a white foam: [α]D25 −62.1 (c 1 CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.64 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H, Ph–CH=C−), 7.54–7.45 (m, 2H, 2 × ArH), 7.43–7.35 (m, 3H, 3 × ArH), 6.95–6.85 (m, 1H, Me–CH–C(Me)–C=O), 6.35 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H, Ph–CH=CH−), 5.32 (t, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H, H-4-Glup), 5.19–5.09 (m, 2H, H-3-Glup, H-4-Fucp), 4.62 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H-1-Glup), 4.54 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H, OH), 4.47 (dd, J = 12.4, 3.6 Hz, 1H, H-6-Glup), 4.41 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, H-1-Fucp), 4.15 (dd, J = 12.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H, H-6-Glup), 3.96–3.88 (m, 2H, OH, H-3-Fucp), 3.80–3.58 (m, 5H, H-2-Glup, H-5-Glup, H-2-Fucp, H-5-Fucp, −CH2–CH–CH2−), 2.88–2.38 (m, 6H), 2.19 (s, 3H, CH3–C=O), 1.80–1.72 (m, 6H, CH3–CH–C(CH3)–C=O), 1.72–1.62 (m, 2H), 1.58–1.45 (m, 4H), 1.42–1.22 (m, 12H), 1.19 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H, H-6-Fucp), 0.90 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 210.0, 171.8, 171.7, 168.9, 165.4, 146.2, 139.9, 134.0, 130.6, 128.9 (×2C), 128.3 (×2C), 127.6, 116.7, 105.7, 100.2, 82.8, 79.8, 76.0, 74.0, 72.7, 72.6, 72.5, 68.8, 67.4, 61.8, 41.9, 37.6, 34.4, 33.1, 31.9, 29.1, 29.0, 28.3, 24.7, 24.5, 23.5, 22.6, 20.9, 16.3, 14.6, 14.1, 12.0. The 1H, 13C NMR data were in accordance with the literature.6,9

Compound 13

To a cooled (0 °C) solution of 5 (150 mg, 0.187 mmol), EDC (71.6 mg, 0.374 mmol), HOBt (57.2 mg, 0.374 mmol), and DMAP (91.3 mg, 0.747 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (20 mL) was added 4-oxoundec-10-eneoic acid 11 (see Supporting Information) (42.6 mg, 0.215 mmol). The reaction was allowed to warm to ambient temperature and stirred overnight. At this point, TLC (silica, 1:3 EtOAc–hexanes) showed the reaction was complete. The mixture was successively washed with aqueous 1 M HCl (20 mL) and saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (20 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:4 → 1:2) to give diene 13 (146 mg, 79%): [α]D25 +4.7 (c 1 CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.02–6.88 (m, 1H, Me–CH–C(Me)–C=O), 6.20–6.04 (m, 1H, CH2=CH–CH2−), 5.87–5.72 (m, 1H, CH2=CH–CH2−), 5.14–4.86 (m, 7H, 2 × CH2=CH–CH2–, H-1-Glup, H-3-Glup, H-4-Fucp), 4.45 (dd, J = 12.0, 4.0 Hz, 1H, H-6-Glup), 4.38–4.26 (m, 2H, H-1-Fucp, H-6-Glup), 4.00 (t, J = 9.2, 7.6 Hz, 1H, H-2-Fucp), 3.90 (dd, J = 9.2, 3.6 Hz, 1H, H-3-Fucp), 3.68–3.60 (m, 2H, H-5-Fucp, −CH2–CH–CH2−), 3.59–3.48 (m, 2H, H-2-Glup, H-4-Glup), 3.46–3.39 (m, 1H, H-5-Glup), 2.88 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H, OH), 2.82–2.51 (m, 4H), 2.44 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 2.35–2.26 (m, 2H), 2.13 (s, 3H, CH3–C=O), 2.09–2.01 (m, 2H), 1.88 (s, 3H, CH3–CH–C(CH3)–C=O), 1.83 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H, CH3–CH–C(CH3)–C=O), 1.67–1.49 (m, 4H), 1.43–1.22 (m, 10H), 1.14 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H, H-6-Fucp), 0.95–0.80 (m, 21H, 2 × (CH3)3C, lipid–CH3), 0.65–0.50 (m, 6H, 3 × CH3CH2–Si), 0.15 (s, 3H, CH3–Si), 0.11 (s, 3H, CH3–Si); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 208.8, 173.2, 170. 9, 168.8, 138.8, 138.4, 136.2, 128.2, 116.1, 114.4, 101.0, 100.3, 80.8, 78.6, 74.4, 74.2, 73.9, 73.5, 73.4, 70.0, 68.9, 63.4, 42.6, 38.6, 37.0, 34.4, 33.5, 31.9, 28.6(23), 28.6(17), 27.8, 25.8 (×6C), 24.6, 23.6, 22.6, 21.0, 17.7, 16.7, 14.4, 14.0, 12.1, 6.8, 5.0, −4.2, −4.3; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C51H90NaO14Si2 [M + Na]+ 1005.5762, found 1005.5758.

Compound 15

At room temperature, second generation Hoveyda–Grubbs catalyst (13.0 mg, 0.021 mmol) was added in one portion to a solution of diene 13 (136 mg, 0.138 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (100 mL). After the reaction mixture was refluxed overnight, TLC (silica, 1:2 EtOAc–hexanes) showed the reaction was complete. The solution was cooled and then concentrated. The acquired crude product was purified by flash chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:2 → 1:1) to give cycloalkene isomers (120.2 mg, 91%) as a colorless syrup. Subsequently, the obtained cycloalkene (86.7 mg, 0.091 mmol) was dissolved in EtOH (4 mL), and Wilkinson’s catalyst (16.8 mg, 0.018 mmol) was added in one portion to the solution at room temperature. After being stirred under an atmosphere of hydrogen (1 atm) overnight, the reaction mixture was filtered through a pad of Celite, followed by washing with EtOAc. The resulting filtrate was concentrated, and the yielded crude product was purified by flash chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:5 → 1:3) to give 15 (65.1 mg, 75%) as a white foam: [α]D25 +3.5 (c 0.5 CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.00–6.89 (m, 1H, Me–CH–C(Me)–C=O), 5.05–4.95 (m, 2H, H-3-Glup, H-4-Fucp), 4.93 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, H-1-Glup), 4.56 (dd, J = 12.0, 4.0 Hz, 1H, H-6-Glup), 4.36 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, H-1-Fucp), 4.21 (dd, J = 12.0, 4.0 Hz, 1H, H-6-Glup), 3.99 (t, J = 9.2, 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-2-Fucp), 3.92 (dd, J = 9.2, 3.2 Hz, 1H, H-3-Fucp), 3.70–3.63 (m, 1H, H-5-Fucp), 3.62–3.45 (m, 4H, H-2-Glup, H-4-Glup, H-5-Glup, −CH2–CH–CH2−), 3.21 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H, OH), 2.90–2.81 (m, 1H), 2.72–2.46 (m, 4H), 2.43–2.30 (m, 1H), 2.13 (s, 3H, CH3–C=O), 1.88 (s, 3H, CH3–CH–C(CH3)–C=O), 1.82 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH3–CH–C(CH3)–C=O), 1.81–1.72 (m, 1H), 1.62–1.22 (m, 21H), 1.14 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H, H-6-Fucp), 0.97–0.85 (m, 21H, 2 × (CH3)3C, lipid–CH3), 0.68–0.52 (m, 6H, 3 × CH3CH2–Si), 0.16 (s, 3H, CH3–Si), 0.11 (s, 3H, CH3–Si); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 210.4, 172.7, 170.9, 168.2, 137.9, 128.5, 101.1, 100.3, 81.4, 78.1, 74.4, 74.2, 73.7, 73.5, 73.1, 70.3, 68.8, 63.8, 41.8, 37.6, 34.6, 34.0, 32.1, 29.4, 29.0, 28.3, 27.6, 27.4, 25.8, 25.3, 24.6, 22.8, 22.6, 21.0, 17.7, 16.7, 14.4, 14.1, 12.1, 6.8 (×6C), 5.0 (×3C), −4.2, −4.3; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C49H88NaO14Si2 [M + Na]+ 979.5605, found 979.5602.

22-Membered Analogue 2

2-Chloro-1-methylpyridinium iodide (CMPI, 13.9 mg, 0.054 mmol), N,N-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP, 8.3 mg, 0.068 mmol), and Et3N (19 μL, 0.14 mmol) were added to a solution of 15 (26.0 mg, 0.027 mmol) and cinnamic acid (6.0 mg, 0.041 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (3 mL) at 0 °C. The reaction was allowed to warm to ambient temperature and stirred for 12 h. At this point, TLC (silica, 1:3 EtOAc–hexanes) showed the reaction was complete. The mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL) and successively washed with aqueous 1 M HCl (20 mL) and saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (20 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was used directly for the final deprotection without further purification. To a solution of the obtained residue in THF (2 mL) were added AcOH (63 μL, 1.1 mmol) and TBAF (1 M solution in THF, 0.55 mL, 0.55 mmol) at rt. The reaction was stirred at rt for 12 h. At this point, TLC (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:1) showed the reaction was complete. The mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL) and successively washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (20 mL) and brine (20 mL) and dried over Na2SO4. Evaporation of the solvent followed by purification of the residue by column chromatography (silica, EtOAc–hexanes, 1:2 → 1:1) to give 22-membered analogue 2 (19.4 mg, 83% over two steps) as a white foam: [α]D25 −51.6 (c 0.5 CHCl3); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.66 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H, Ph–CH=C−), 7.58–7.48 (m, 2H, 2 × ArH), 7.45–7.38 (m, 3H, 3 × ArH), 6.95–6.84 (m, 1H, Me–CH–C(Me)–C=O), 6.35 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H, Ph–CH=CH−), 5.30 (t, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H, H-3-Glup), 5.25–5.19 (m, 1H, H-4-Fucp), 5.18 (t, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H, H-4-Glup), 4.66 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-1-Glup), 4.48–4.40 (m, 2H, H-1-Fucp, H-6-Glup), 4.32 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H, OH), 3.98 (dd, J = 12.0, 6.8 Hz, 1H, H-6-Glup), 3.88–3.68 (m, 7H, H-2-Glup, H-5-Glup, H-2-Fucp, H-3-Fucp, H-5-Fucp, −CH2–CH–CH2–, OH), 2.88–2.75 (m, 1H), 2.68–2.51 (m, 3H), 2.46 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.23 (s, 3H, CH3–C=O), 1.80–1.72 (m, 6H, CH3–CH–C(CH3)–C=O), 1.62–1.48 (m, 6H), 1.41–1.23 (m, 16H), 1.20 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H, H-6-Fucp), 0.88 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 209.5, 171.6, 171.4, 167.8, 165.6, 146.6, 139.0, 134.0, 130.7, 128.9 (×2C), 128.3 (×2C), 127.7, 116.5, 102.8, 100.0, 79.7, 77.9, 74.3, 72.9, 72.1, 71.9, 70.7, 69.4, 68.7, 62.4, 42.2, 37.2, 34.4, 33.1, 31.8, 28.6, 28.5, 28.3, 27.9, 27.8, 24.7, 23.7, 23.4, 22.6, 21.0, 16.2, 14.5, 14.0, 12.0; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C46H66NaO15 [M + Na]+ 881.4294, found 881.4294.

Cell Culture

The human breast cancer cells (MCF7 and MDA-MB-231) were cultured by following a previously established protocol.9

AlamarBlue or MTT Cytotoxicity Assay

Cytotoxicity assays were performed as previously described.9 Briefly, after cell counting, 100 μL of cell suspension was seeded in a 96-well plate (2500 cells/well), which was incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were treated with 100 μL of the freshly made working solution of a test compound for 72 h. Afterward, the media were removed, and 200 μL of the fresh medium containing 10% of AlamarBlue (resazurin) (3 mg/27.15 mL) or MTT (5 mg/mL) stock solution was added to each well. After further incubation for another 3 h, Fluorescence of metabolic resorufin or absorbance of formazan was detected by a microplate reader (BioTek Synergy H1).

Activities of ipomoeassin F and analogues 2 and 3 against MDA-MB-231 or MCF7 cells were tested by the AlamarBlue or MTT assay, respectively. The GraphPad Prism 6 software was used to plot curves of % viability versus concentration and to calculate IC50 values.

In Vitro Membrane Insertion Assay

Preparation of mRNA Templates

Linear DNA of the short form of human HLA class II histocompatibility antigen gamma chain (Ii; P04232, isoform 2, residues 17–232) was generated by PCR and transcribed into RNA using SP6 polymerase (Promega).

In Vitro Translation and Insertion into ER Microsomes

Membrane insertion assays were performed as previously described.11 Briefly, translation reactions (20 μL) were performed in nuclease-treated rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega) in the presence of EasyTag EXPRESS 35S protein labeling mix containing [35S] methionine (PerkinElmer) (0.533 MBq; 30.15 TBq/mmol). Amino acids minus methionine (Promega) were added to 25 μM each, 5% (v/v) compound (concentration as indicated in figures, from stock solutions in DMSO), or an equivalent volume of DMSO, and nuclease-treated ER microsomes (from stock with OD280 = 44/mL) were added to 6.5% (v/v). Lastly, 10% volume of in vitro transcribed Ii mRNA (from 400 to 600 ng/μL stocks) was added, and translation reactions were performed for 20 min at 30 °C. Following incubation with 0.1 mM puromycin for 5 min at 30 °C to ensure translational termination and ribosome release, membrane-associated fractions were isolated by centrifugation through an 80 μL high-salt cushion (0.75 M sucrose, 0.5 M KOAc, 5 mM Mg(OAc)2, 50 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.9) at 100,000g for 10 min at 4 °C in a TLA100 rotor (Beckmann). Membrane pellets were suspended directly in SDS (sodium dodecyl sulfate) sample buffer (0.02% bromophenol blue, 62.5 mM, 4% (w/v) SDS, 10% (v/v) glycerol, pH 7.6, 1 M dithiothreitol) and, where indicated, treated with 1000 U of endoglycosidase H (New England Biolabs) for 30 min at 37 °C prior to analysis. All samples were denatured for 10 min at 70 °C prior to resolution by SDS-PAGE (16% polyacrylamide gels, 120 V, 120 min); gels were fixed (20% MeOH, 10% AcOH) for 5 min, dried (BioRad gel dryer) for 2 h at 65 °C, and following exposure to a phosphorimaging plate for 24–72 h, radiolabeled products were visualized using a Typhoon FLA-7000 (GE Healthcare).

Quantitative Analysis

Using AIDA v.5.0 (Raytest Isotopenmeβgeräte), the ratio of the signal intensity for the 2Gly/0Gly forms was used as a readout to estimate the efficiency of integration into the ER membrane. This value was then expressed relative to the matched DMSO control in order to derive the mean relative ER insertion from three (n = 3, analogue 2) or four (n = 4, Ipom-F, previously reported data11) independent experiments. IC50 value estimates were determined in Prism 8 (GraphPad) using nonlinear regression to fit data to a curve of variable slope (four parameters) using the least-squares fitting method in which the top and bottom plateaus of the curve were defined as 0 and 100%, respectively.

Determination of the Maximum Tolerated Dose

To reduce the number of animals (C57BL/6 female mice) used in the determination of MTD, we used a “narrow down” approach (successive rounds of treatment of animals). Because the data on the ipomoeassin F cytotoxicity on animals were not available, we selected the starting dose range for the first group of mice (group 1) for MTD study based on the results of paclitaxel on mice.39−41 Using 5% DMSO and 95% peanut oil (Sigma) as the delivery vehicle, we performed intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections (150 μL) in C57BL/6 female mice (∼8 weeks old) every 3 days over a course of 3 weeks or until the end point was reached. The end point was defined by a 15% loss of body weight and/or signs of distress and/or inability to eat/drink for the treated mice. When mice showed any of these signs, they were euthanized. The first group of mice were treated with 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mg/kg body weight of ipomoeassin F (one mouse/each dose). After four injections, all the mice died or were sacrificed except for the mouse being treated with vehicle only (0 mg/kg body weight). Based on these results, we treated the second group (group 2) of C57BL/6 female mice with 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mg/kg body weight of ipomoeassin F (one mouse/each dose). In the second group, the mice treated with 3, 4, and 5 mg/kg body weight died or were sacrificed after five injections, and the mice treated with 1 and 2 mg/kg body weight survived after six injections. Accordingly, we treated the third group (group 3) of mice with 2 and 3 mg/kg body weight of ipomoeassin F (one mouse/each dose). In the third group, both mice survived after six injections. Based on these results, the MTD of ipomoeassin F was estimated to be ∼3 mg/kg body weight under the conditions used in this study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant No. 2R15GM116032-02A1 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and a Ball State University (BSU) Provost Startup Award (to W.Q.S.), together with Wellcome Trust Investigator Award in Science ref no. 204957/Z/16/Z (to S.H.). L.E.A. is the recipient of BSU honors college research grants from 01/2020–12/2020.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.0c01659.

Structures of the ipomoeassins; synthetic schemes for analogue 3 and intermediates S1, 5, 7, and 8; table for optimization of chemoselective removal of isopropylidene to make 5 (PDF)

Biological assay data; 1H, 13C NMR and HRMS spectra of all synthesized new compounds (COSY, HSQC, and HMBC NMR for representative compounds) (PDF)

FAIR data, including the primary NMR FID files, for compounds 2–5, 7, and 10–13 (ZIP)

FAIR data, including the primary NMR FID files, for compounds 14–16, S3, S5, S6, and ipomoeassin F (ZIP)

Author Contributions

△ G. Zong and Z. Hu contributed equally as first author.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Cao S.; Guza R. C.; Wisse J. H.; Miller J. S.; Evans R.; Kingston D. G. I. Ipomoeassins A–E, Cytotoxic Macrocyclic Glycoresins from the Leaves of Ipomoea squamosa from the Suriname Rainforest1. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 487–492. 10.1021/np049629w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S.; Norris A.; Wisse J. H.; Miller J. S.; Evans R.; Kingston D. G. I. Ipomoeassin F, a new cytotoxic macrocyclic glycoresin from the leaves of Ipomoea squamosa from the Suriname rainforest. Nat. Prod. Res. 2007, 21, 872–876. 10.1080/14786410600929576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürstner A.; Nagano T. Total Syntheses of Ipomoeassin B and E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 1906–1907. 10.1021/ja068901g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano T.; Pospíšil J.; Chollet G.; Schulthoff S.; Hickmann V.; Moulin E.; Herrmann J.; Müller R.; Fürstner A. Total Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of the Cytotoxic Resin Glycosides Ipomoeassin A–F and Analogues. Chem. - Eur. J. 2009, 15, 9697–9706. 10.1002/chem.200901449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postema M. H. D.; TenDyke K.; Cutter J.; Kuznetsov G.; Xu Q. Total Synthesis of Ipomoeassin F. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 1417–1420. 10.1021/ol900086b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong G.; Barber E.; Aljewari H.; Zhou J.; Hu Z.; Du Y.; Shi W. Q. Total Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Ipomoeassin F and Its Unnatural 11R-Epimer. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 9279–9291. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b01765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong G.; Aljewari H.; Hu Z.; Shi W. Q. Revealing the Pharmacophore of Ipomoeassin F through Molecular Editing. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 1674–1677. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong G.; Hirsch M.; Mondrik C.; Hu Z.; Shi W. Q. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of fucose-truncated monosaccharide analogues of ipomoeassin F. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 2752–2756. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.04.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong G.; Whisenhunt L.; Hu Z.; Shi W. Q. Synergistic Contribution of Tiglate and Cinnamate to Cytotoxicity of Ipomoeassin F. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 4977–4985. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b00409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong G.; Sun X.; Bhakta R.; Whisenhunt L.; Hu Z.; Wang F.; Shi W. Q. New insights into structure–activity relationship of ipomoeassin F from its bioisosteric 5-oxa/aza analogues. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 144, 751–757. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong G.; Hu Z.; O’Keefe S.; Tranter D.; Iannotti M. J.; Baron L.; Hall B.; Corfield K.; Paatero A. O.; Henderson M. J.; Roboti P.; Zhou J.; Sun X.; Govindarajan M.; Rohde J. M.; Blanchard N.; Simmonds R.; Inglese J.; Du Y.; Demangel C.; High S.; Paavilainen V. O.; Shi W. Q. Ipomoeassin F Binds Sec61α to Inhibit Protein Translocation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 8450–8461. 10.1021/jacs.8b13506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luesch H.; Paavilainen V. O. Natural products as modulators of eukaryotic protein secretion. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2020, 37, 717. 10.1039/C9NP00066F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross B. C. S.; McKibbin C.; Callan A. C.; Roboti P.; Piacenti M.; Rabu C.; Wilson C. M.; Whitehead R.; Flitsch S. L.; Pool M. R.; High S.; Swanton E. Eeyarestatin I inhibits Sec61-mediated protein translocation at the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 4393–4400. 10.1242/jcs.054494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison J. L.; Kunkel E. J.; Hegde R. S.; Taunton J. A substrate-specific inhibitor of protein translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature 2005, 436, 285. 10.1038/nature03821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon A. L.; Garrison J. L.; Hegde R. S.; Taunton J. Photo-Leucine Incorporation Reveals the Target of a Cyclodepsipeptide Inhibitor of Cotranslational Translocation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 14560–14561. 10.1021/ja076250y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Law B. K.; Luesch H. Apratoxin A Reversibly Inhibits the Secretory Pathway by Preventing Cotranslational Translocation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009, 76, 91–104. 10.1124/mol.109.056085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paatero A. O.; Kellosalo J.; Dunyak B. M.; Almaliti J.; Gestwicki J. E.; Gerwick W. H.; Taunton J.; Paavilainen V. O. Apratoxin Kills Cells by Direct Blockade of the Sec61 Protein Translocation Channel. Cell Chem. Biol. 2016, 23, 561–566. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song F.; Fidanze S.; Benowitz A. B.; Kishi Y. Total Synthesis of the Mycolactones. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 647–650. 10.1021/ol0172828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall B. S.; Hill K.; McKenna M.; Ogbechi J.; High S.; Willis A. E.; Simmonds R. E. The Pathogenic Mechanism of the Mycobacterium ulcerans Virulence Factor, Mycolactone, Depends on Blockade of Protein Translocation into the ER. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004061 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna M.; Simmonds R. E.; High S. Mechanistic insights into the inhibition of Sec61-dependent co- and post-translational translocation by mycolactone. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 1404–1415. 10.1242/jcs.182352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotzke J. E.; Kozik P.; Morel J.-D.; Impens F.; Pietrosemoli N.; Cresswell P.; Amigorena S.; Demangel C. Sec61 blockade by mycolactone inhibits antigen cross-presentation independently of endosome-to-cytosol export. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114, E5910–E5919. 10.1073/pnas.1705242114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chany A.-C.; Casarotto V.; Schmitt M.; Tarnus C.; Guenin-Macé L.; Demangel C.; Mirguet O.; Eustache J.; Blanchard N. A Diverted Total Synthesis of Mycolactone Analogues: An Insight into Buruli Ulcer Toxins. Chem. - Eur. J. 2011, 17, 14413–14419. 10.1002/chem.201102542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-J.; Kishi Y. Total Synthesis and Stereochemistry of Mycolactone F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 1842–1844. 10.1021/ja7111838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junne T.; Wong J.; Studer C.; Aust T.; Bauer B. W.; Beibel M.; Bhullar B.; Bruccoleri R.; Eichenberger J.; Estoppey D.; Hartmann N.; Knapp B.; Krastel P.; Melin N.; Oakeley E. J.; Oberer L.; Riedl R.; Roma G.; Schuierer S.; Petersen F.; Tallarico J. A.; Rapoport T. A.; Spiess M.; Hoepfner D. Decatransin, a new natural product inhibiting protein translocation at the Sec61/SecYEG translocon. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 1217–1229. 10.1242/jcs.165746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina R. A.; Goeger D. E.; Hills P.; Mooberry S. L.; Huang N.; Romero L. I.; Ortega-Barría E.; Gerwick W. H.; McPhail K. L. Coibamide A, a Potent Antiproliferative Cyclic Depsipeptide from the Panamanian Marine Cyanobacterium Leptolyngbya sp. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 6324–6325. 10.1021/ja801383f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranter D.; Paatero A. O.; Kawaguchi S.; Kazemi S.; Serrill J. D.; Kellosalo J.; Vogel W. K.; Richter U.; Mattos D. R.; Wan X.; Thornburg C. C.; Oishi S.; McPhail K. L.; Ishmael J. E.; Paavilainen V. O. Coibamide A Targets Sec61 to Prevent Biogenesis of Secretory and Membrane Proteins. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15, 2125–2136. 10.1021/acschembio.0c00325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowski R. S.; Wuest W. M. Twelve-membered macrolactones: privileged scaffolds for the development of new therapeutics. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2017, 89, 169–191. 10.1111/cbdd.12783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selwood D. L. Macrocycles, the edge of drug-likeness chemical space or Goldilocks zone?. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2017, 89, 164–168. 10.1111/cbdd.12922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong G.; Shi W. Q. In Strategies and Tactics in Organic Synthesis; Harmata M., Ed.; Academic Press: 2017; Vol. 13, pp 81–110. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna M.; Simmonds R. E.; High S. Mycolactone reveals substrate-driven complexity of Sec61-dependent transmembrane protein biogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 130, 1307–1320. 10.1242/jcs.198655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamayun I.; O’Keefe S.; Pick T.; Klein M.-C.; Nguyen D.; McKibbin C.; Piacenti M.; Williams H. M.; Flitsch S. L.; Whitehead R. C.; Swanton E.; Helms V.; High S.; Zimmermann R.; Cavalié A. Eeyarestatin Compounds Selectively Enhance Sec61-Mediated Ca2+ Leakage from the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019, 26, 571–583. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q.-Y.; Liu Y.; Luesch H. Systematic Chemical Mutagenesis Identifies a Potent Novel Apratoxin A/E Hybrid with Improved in Vivo Antitumor Activity. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 861–865. 10.1021/ml200176m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao G.; Wang W.; Ao L.; Cheng Z.; Wu C.; Pan Z.; Liu K.; Li H.; Su W.; Fang L. Improved Total Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Coibamide A Analogues. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 8908–8916. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gérard S. F.; Hall B. S.; Zaki A. M.; Corfield K. A.; Mayerhofer P. U.; Costa C.; Whelligan D. K.; Biggin P. C.; Simmonds R. E.; Higgins M. K. Structure of the Inhibited State of the Sec Translocon. Mol. Cell 2020, 79, 406–415. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen J. C.; Leonard J.; Aggarwal V. K. A Novel Asymmetric Azaspirocyclisation Using a Morita-Baylis-Hillman-Type Reaction. Synlett 2010, 2010, 579–582. 10.1055/s-0029-1219210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster R. C.; Suitor J. T.; Bennett A. W.; Wallace S. Transition Metal-Free Reduction of Activated Alkenes Using a Living Microorganism. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 12409–12414. 10.1002/anie.201903973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jassem A. M.; Al-Ajely H. M.; Almashal F. A. K.; Chen B. Application of the Cleavable Isocyanide in Efficient Approach to Pyroglutamic Acid Analogues with Potential Biological Activity. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2019, 89, 2562–2570. 10.1134/S1070363219120363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy B.; Field R. A.; Mukhopadhyay B. Synthesis of a tetrasaccharide related to the repeating unit of the O-antigen from Escherichia coli K-12. Carbohydr. Res. 2009, 344, 2311–2316. 10.1016/j.carres.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak K. M.; Nomoto K.; Lapidus R. G.; Wu Y.; Carozzi V.; Cavaletti G.; Hayakawa K.; Hosokawa S.; Towle M. J.; Littlefield B. A.; Slusher B. S. Comparison of Neuropathy-Inducing Effects of Eribulin Mesylate, Paclitaxel, and Ixabepilone in Mice. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 3952–3962. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang D.; Sui M.; Zhong W.; Huang Y.; Fan W. Different administration strategies with paclitaxel induce distinct phenotypes of multidrug resistance in breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2013, 335, 404–411. 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya J.; Bellucci J. J.; Weitzhandler I.; McDaniel J. R.; Spasojevic I.; Li X.; Lin C.-C.; Chi J.-T. A.; Chilkoti A. A paclitaxel-loaded recombinant polypeptide nanoparticle outperforms Abraxane in multiple murine cancer models. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7939. 10.1038/ncomms8939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.