Abstract

The transient elevation of cytosolic free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) induced by cold stress is a well‐established phenomenon; however, the underlying mechanism remains elusive. Here, we report that the Ca2+‐permeable transporter ANNEXIN1 (AtANN1) mediates cold‐triggered Ca2+ influx and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. The loss of function of AtANN1 substantially impaired freezing tolerance, reducing the cold‐induced [Ca2+]cyt increase and upregulation of the cold‐responsive CBF and COR genes. Further analysis showed that the OST1/SnRK2.6 kinase interacted with and phosphorylated AtANN1, which consequently enhanced its Ca2+ transport activity, thereby potentiating Ca2+ signaling. Consistent with these results and freezing sensitivity of ost1 mutants, the cold‐induced [Ca2+]cyt elevation in the ost1‐3 mutant was reduced. Genetic analysis indicated that AtANN1 acts downstream of OST1 in responses to cold stress. Our data thus uncover a cascade linking OST1‐AtANN1 to cold‐induced Ca2+ signal generation, which activates the cold response and consequently enhances freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, calcium signal, calcium‐permeable transporter AtANN1, freezing tolerance, OST1 kinase

Subject Categories: Membrane & Intracellular Transport, Plant Biology, Signal Transduction

Cold‐activated OST1 kinase phosphorylates ANNEXIN1 to boost calcium ion uptake and thus promotes expression of COR genes that enhance cold stress responses in Arabidopsis.

Introduction

Calcium (Ca2+), a universal second messenger, is involved in many aspects of plant development and responses to the environment. Abiotic and biotic stresses such as cold, heat, and salt, as well as pathogen infection, act on Ca2+‐permeable channels to cause transient increases in cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt). These Ca2+ signals (also known as Ca2+ signatures) convert external signals into diverse intracellular biochemical responses (Knight, 2002; Dodd et al, 2010; Finka et al, 2012; Tunc‐Ozdemir et al, 2013; Toyota et al, 2018; Jiang et al, 2019).

Low temperatures, with global climate change, are occurring more frequently and cause significant decreases in crop yield. Cold stress changes the fluidity of the plasma membrane, which may be sensed by Ca2+ channels and other plasma membrane proteins, triggering increased [Ca2+]cyt and activating cold stress responses (Zhu, 2016). A breakthrough study established that the G‐protein regulator Chilling Tolerance Divergence 1 (COLD1), coupled with Rice G‐protein α Subunit 1 (RGA1), mediates the cold‐induced influx of Ca2+ and confers cold sensing in rice (Oryza sativa) (Ma et al, 2015; Guo et al, 2018). However, it is unknown whether COLD1 itself functions as a Ca2+ channel or instead regulates the activity of a Ca2+ channel. In Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings, mechanosensitive Ca2+‐permeable channels Mid1‐Complementing Activity 1 (MCA1) and MCA2 contribute to cold‐induced influx of Ca2+ but are not the sole means of Ca2+ transport across the plasma membrane (Mori et al, 2018). Therefore, although it is well established that cold stress triggers a transient elevation of Ca2+ in the cytosol and organelles of plant cells, it is not yet fully understood how the cold‐induced Ca2+ signal is generated and controlled.

Annexins are a subfamily of phospholipid‐ and Ca2+‐binding proteins that are evolutionarily conserved across several kingdoms (Morgan et al, 2006; Laohavisit & Davies, 2011). The Arabidopsis genome harbors eight genes encoding annexins (Cantero et al, 2006), some of which regulate stress responses. Several studies have suggested that AtANN1 is a Ca2+‐permeable transporter that mediates the accumulation of [Ca2+]cyt in response to reactive oxygen species (ROS) and salt stresses (Lee et al, 2004; Laohavisit et al, 2012; Richards et al, 2014). Cold induces annexin expression in poplar leaves (Renaut et al, 2006). In wheat, two annexins accumulate at the plasma membrane in response to cold stress, and their insertion into the plasma membrane might be involved in regulating cold‐induced Ca2+ signaling (Breton et al, 2000). AtANN1 is upregulated by heat treatment and positively regulate the heat‐induced increase in [Ca2+]cyt and heat tolerance (Wang et al, 2015). Annexins regulate the transcription factor MYB30‐dependent Ca2+ signaling in response to oxidative and heat stresses (Liao et al, 2017). Moreover, AtANN1 interacts with AtANN4 in a Ca2+‐dependent manner to coordinately regulate drought and salt stress responses (Huh et al, 2010). A recent finding showed that AtANN4 regulates the generation of specific cytosolic Ca2+ signals under salt stress that are essential for activating the Salt Overly Sensitive (SOS) pathway (Ma et al, 2019). Moreover, the rice homolog, OsANN1, enhances heat tolerance by modulating the production of ROS (Qiao et al, 2015). Therefore, annexins function as Ca2+‐permeable transporters in regulating plant responses to adverse environmental cues.

When plants sense cold signal, they initiate comprehensive strategies that counteract the adverse effects of cold stress. One strategy is to biosynthesize protective substances, under the control of three key transcription factors in the C‐repeat Binding Factor/Dehydration‐Responsive Element‐Binding Factor 1 family (CBF/DREB1) (Thomashow, 1999; Jia et al, 2016; Zhao et al, 2016). CBF proteins bind directly to the promoters of Cold‐Regulated (COR) genes, some of which encode cryoprotective proteins or involve the accumulation of osmolytes that enhance plant freezing tolerance, and activate their expression (Stockinger et al, 1997; Liu et al, 1998; Thomashow, 1999). The expression of CBFs is rapidly induced by low temperatures, and the level of their expression is fine‐tuned by many positive and negative regulators, including transcription factors, E3 ligases, SUMO E3 ligases, and protein kinases (Guo et al, 2018; Liu et al, 2018a; Ding et al, 2020).

One of these protein kinases, Open Stomatal 1 (OST1), known for its involvement in the plant's response to abscisic acid (ABA), was reported to positively regulate freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis (Mustilli et al, 2002; Ding et al, 2015). ABA or cold can activate OST1 kinase activity by releasing the inhibition of type‐2C protein phosphatases on OST1 in an ABA‐dependent or independent manner, respectively (Ma et al, 2009; Park et al, 2009; Ding et al, 2015; Ding et al, 2019). Activated OST1 directly phosphorylates transcription factors localized at the nucleus such as ABRE‐binding proteins/factors (AREBs/ABFs) or Inducer of CBF Expression 1 (ICE1), enhancing their transcriptional activity and thereby activating the expression of ABA‐ or cold‐responsive genes, respectively (Furihata et al, 2006; Ding et al, 2015). In addition, cold‐activated OST1 interacts with and phosphorylates Basic Transcription Factor 3 (BTF3), BTF3L (BTF3‐Like), and two U‐box type E3 ligases (PUB25 and PUB26) in the nucleus, where it enhances BTF3(L)'s binding to and stabilization of CBF proteins and promotes the E3 activity of PUB25 and PUB26 (Ding et al, 2018; Wang et al, 2019). Furthermore, OST1 regulates stomatal movement by phosphorylating and activating the S‐type anion channel SLAC1 and K+ channel AKT1 at the plasma membrane (Lee et al, 2009; Sato et al, 2009). Together, these results indicate that OST1 plays key roles in regulating plant stress responses by participating in protein–protein interactions, enhancing the transcriptional or E3 activity of stress‐responsive proteins, or activating channels at the plasma membrane.

In this study, we report that AtANN1 mediates the generation of cold‐induced Ca2+ signals. Mutation of AtANN1 reduces the magnitude of the cold‐induced increase in [Ca2+]cyt and consequently decreases freezing tolerance. Furthermore, AtANN1 positively regulates the expression of CBFs and their regulons. In addition, cold‐activated OST1 phosphorylates AtANN1, thereby enhancing its Ca2+ transport activity, and further potentiating Ca2+ signaling. Our results thus unravel a critical link between OST1‐AtANN1 and specific cold‐triggered cytosolic Ca2+ signals in plant responses to cold.

Results

AtANN1 positively regulate plant freezing tolerance

Previous studies showed that cold shock triggers transient increases in [Ca2+]cyt, which is mediated by Ca2+‐permeable channels. Annexins are suggested to be Ca2+‐permeable transporters (Laohavisit et al, 2012; Ma et al, 2019), and cold induces annexin gene expression in poplar (Renaut et al, 2006) and protein accumulation of annexins at the plasma membrane in wheat (Breton et al, 2000). Therefore, we hypothesized that annexins might be involved in regulating plant response to cold. To test this hypothesis, we first examined the freezing tolerance of atann1 and atann4 mutants, and found that atann1 and atann4 mutants exhibited decreased freezing tolerance compared to the wild type (Figs 1A and EV1), indicating that annexins are indeed involved in regulating cold response in Arabidopsis.

Figure 1. AtANN1 mediates plants response to freezing tolerance in CBF‐dependent manner.

-

A–CFreezing phenotype (A), survival rate (B), and ion leakage (C) of Col‐0, atann1, and atann1 AtANN1 (#10) plants. Twelve‐day‐old plants grown on MS medium at 22°C were exposed to freezing temperatures (NA for non‐acclimation, −5°C, 30 min; CA for cold acclimation, −8°C, 40 min). Representative pictures are shown in (A).

-

D, EExpression of CBFs (D) and their targets (E) in Col‐0, atann1, and atann1 AtANN1 (#10) plants. Twelve‐day‐old plants grown on MS medium at 22°C were placed at 4°C for 3 h (D) or 24 h (E), and total RNA was extracted and subjected to qRT–PCR analysis. Relative transcript levels in untreated Col‐0 plants were set to 1.

Data information: In (B and C), the data represent means ± SE of three independent experiments, each with three technical repeats (n = 25 seedlings for each repeat). **P < 0.01, two‐tailed t‐test. In (D and E), the data represent means ± SD of three technical replicates (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, two‐tailed t‐test). Three independent experiments showed a similar result.

Figure EV1. AtANN1 and AtANN4 modulate plant freezing tolerance.

-

A, BmRNA (A) and the protein (B) levels of AtANN1 in the wild type (Col‐0), atann1 and atann1 AtANN1 (#4 and #10) seedlings. AtANN1 protein was detected with anti‐GFP antibody. HSP90 was used as a control.

-

C–EFreezing phenotype (C), survival rate (D), and ion leakage (E) of Col‐0, atann1, and atann1 AtANN1 (#4) plants. 12‐day‐old plants grown on MS medium at 22°C were exposed to freezing temperatures (NA for non‐acclimation, −5°C, 30 min; CA for cold acclimation, −8°C, 40 min). Representative pictures are shown in (C).

-

F, GFreezing phenotype (F) and survival rate (G) of Col‐0, atann4‐1, and atann4‐2 plants. 12‐day‐old plants grown on MS medium at 22°C were exposed to freezing temperatures (NA, −5°C, 30 min; CA, −8°C, 40 min). Representative pictures are shown in (F).

-

H, IFreezing phenotype (H) and survival rate (I) of Col‐0, atann1, atann4‐1 and atann1 atann4‐1 plants. 12‐day‐old plants grown on MS medium at 22°C were exposed to freezing temperatures (NA, −5°C, 30 min; CA, −8°C, 40 min). Representative pictures are shown in (H).

Data information: In (A), the data represent means ± SD of three technical replicates. In (D, E, G, and I), the data represent means ± SE of three independent experiments, each with three technical repeats (n = 25 seedlings for each repeat for D, E, and G, and n = 19 for I). In (D, E, and G), **P < 0.01, two‐tailed t‐test. In (I), different letters represent significant difference at P < 0.05 (one‐way ANOVA).

Source data are available online for this figure.

The non‐acclimated (NA) atann1 loss‐of‐function mutant (SALK_015426) (Lee et al, 2004) displayed lower survival rate than the wild type (Figs 1A and B and EV1A and B). After cold acclimation (CA) at 4°C for 3 days, the atann1 mutant also showed decreased freezing tolerance compared to the wild type (Fig 1A and B). Consistent with these results, the ion leakage, an indicator of membrane damage caused by freezing stress, was significantly increased in the atann1 mutant under NA and CA conditions (Fig 1C). Furthermore, the freezing sensitive phenotype of the atann1 mutant was fully rescued in two independent complementation lines harboring approximately 1.5 kb promoter and genomic DNA of AtANN1 tagged with green fluorescence protein (GFP; atann1 AtANN1 #10 and atann1 AtANN1 #4; Figs 1A–C, and EV1A–E), indicating that this freezing sensitivity is indeed caused by mutation of AtANN1. These data suggest that AtANN1 positively modulates constitutive (basal) and acquired freezing tolerance of Arabidopsis.

The atann4‐1 and atann4‐2 loss‐of‐function mutants (Ma et al, 2019) exhibited lower survival rates than the wild type with or without cold acclimation (Fig EV1F and G). We then generated an atann1 atann4‐1 double mutant by crossing and examined its freezing tolerance. The non‐acclimated atann1 atann4‐1 double mutant phenocopied atann1 and atann4‐1 single mutants, whereas the survival rate of the acclimated double mutant plants was lower than that of the single mutants (Fig EV1H and I), suggesting that AtANN1 and AtANN4 have redundant functions in acquired freezing tolerance. These results demonstrate that AtANN1 and AtANN4 are positive regulators of basal and acquired freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis.

To explore how AtANN1 regulates plant freezing tolerance, we examined the expression of CBF genes and CBF‐regulated genes, including GOLS3, COR15B, COR47, and KIN1, in wild‐type and atann1 mutant plants under cold stress. The expression of these genes in wild‐type and atann1 mutant plants were comparable at 22°C (Fig 1D and E). However, cold‐induction of CBF1, CBF2, and CBF3 was approximately 20–30% reduced in atann1 mutant compared to the wild type (Fig 1D). Moreover, cold‐induced expression of CBF target genes, COR47 and KIN1, was decreased 35%, and GOLS3 and COR15B was decreased up to 50% compared to the wild type (Fig 1E). These observations suggest that AtANN1 positively regulates plant acquired freezing tolerance at least partially by affecting the expression of CBFs and their target COR genes, with a more prominent effect on COR genes.

AtANN1 contributes to cold‐induced elevation of [Ca2+]cyt

AtANN1 was shown previously to act as a Ca2+‐permeable transporter (Laohavisit et al, 2012), and cold shock induces a rapid increase in [Ca2+]cyt in Arabidopsis (Knight et al, 1996). These findings prompted us to examine whether AtANN1 is involved in the cold shock‐induced increase in [Ca2+]cyt. To this end, 10‐day‐old wild‐type and atann1 mutant plants expressing aequorin, the Ca2+ reporter (Knight et al, 1991), were treated with an ice‐cold water and subjected to luminescence measurements with a cold charge‐coupled device (CDD) image system. After cold treatment, both wild type and atann1 showed an increase in luminescence signals. However, the luminescence signal intensity in atann1 was less half of that in wild type (Fig EV2A and B), although the aequorin protein levels in atann1 and wild type were comparable (Fig EV2C).

Figure EV2. Analysis of [Ca2+]cyt in atann1 mutant under cold stress.

-

A–CPseudocolor luminescence image of Ca2+‐dependent photons emitted by 10‐day‐old wild type (Col‐0), atann1, and atann1 AtANN1 complementation line (#10) after treatment with ice‐cold water (4°C water) (A). Seedlings grown at 22°C or treated with water at room temperature (22°C water) were used as controls. Luminescence signals were collected for 8 min and the color scale indicates photon counts per pixel (A, top), and photographs was taken as control (A, bottom). Analysis of relative luminescence signal intensity in (A) was shown (B). Aequorin protein levels of seedlings used in (A) detected with anti‐Aequorin antibody (C). HSP90 was used as a control.

-

DTime‐course analysis of [Ca2+]cyt dynamics between 10‐day‐old wild‐type (Col‐0) and ann1‐2 mutant after treatment with 4°C water (arrow shows the time point of treatment). Luminescence was recorded at 1‐s intervals. Quantification of the cold‐induced [Ca2+]cyt changes shown in the left. Peak [Ca2+]cyt indicates the highest [Ca2+]cyt after treatment.

-

ETime‐course analysis of cytosolic free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) dynamics in 10‐day‐old wild type (Col‐0), atann1, and atann1 AtANN1 complementation line (#10) after treatment with 22°C water or 22°C water containing 10 mM LaCl3 (arrow shows the time point of treatment). Luminescence was recorded at 1‐s intervals.

-

FTime‐course analysis of [Ca2+]cyt dynamics between 10‐day‐old wild‐type (Col‐0) and atann4‐1 mutant after treatment with 4°C water (left) or 22°C water (right). Luminescence was recorded at 1‐s intervals. Quantification of the cold‐induced [Ca2+]cyt changes shown in the left. Peak [Ca2+]cyt indicates the highest [Ca2+]cyt after treatment.

Data information: In (B), the data represent means ± SD (n = 8). Different letters represent significant difference at P < 0.05 (one‐way ANOVA). Three independent experiments showed a similar result. In (D–F), the data represent means ± SD (n = 15; **P < 0.01, two‐tailed t‐test). Three independent experiments showed a similar result.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Next, the [Ca2+]cyt changes in wild type and atann1 after cold shock was measured with a luminometer. [Ca2+]cyt was rapidly and dramatically induced by cold water (Fig 2A and B). However, the atann1 mutant showed a lower cold shock‐induced increase in [Ca2+]cyt than the wild type (Fig 2A and B). The cold shock‐induced [Ca2+]cyt elevation in the ann1‐2 mutant (SAIL_414_C01) expressing aequorin (Wang et al, 2015) was also diminished compared to that of the wild type (Fig EV2D). Moreover, the change of [Ca2+]cyt in the atann1 mutant was fully complemented by a genomic fragment of AtANN1 tagged with GFP (atann1 AtANN1 #10; Figs 2A and B, and EV2A and B). After treated the plants with lanthanum chloride (LaCl3), a widely used Ca2+ channel blocker, we found that the cold shock‐induced [Ca2+]cyt increase in wild type, atann1 and atann1 AtANN1 complementation plants was dramatically suppressed (Fig 2A and B). However, treatment with water at room temperature (22°C) did not obviously alter the [Ca2+]cyt in the presence or absence of LaCl3 (Fig EV2E).

Figure 2. OST1 interacts with the Ca2+‐permeable transporter AtANN1.

-

ATime‐course analysis of cytosolic free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) dynamics in 10‐day‐old wild type (Col‐0), atann1, and atann1 AtANN1 complementation line (#10) after treatment with ice‐cold water or ice‐cold water containing 10 mM LaCl3 (arrow shows the time point of treatment). Luminescence was recorded at 1‐s intervals.

-

BQuantification of the cold‐induced [Ca2+]cyt changes shown in (A). Peak [Ca2+]cyt indicates the highest [Ca2+]cyt after treatment.

-

CGST pull‐down assay showing that OST1 interacts with AtANN1 in vitro. Purified recombinant GST‐OST1, GST‐OST1G33R, or GST proteins from Escherichia coli were immunoprecipitated with GST beads and then incubated with MBP‐His‐AtANN1. Precipitated proteins were detected with anti‐GST and anti‐His antibodies.

-

DInteraction of OST1 and AtANN1 detected by bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays. The construct combinations were co‐transformed into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves and expressed for 2 days. The signal was detected by confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 25 µm. The fluorescence intensity was scanned using the ImageJ plot profile tool. The y‐axes indicate relative pixel intensity.

-

E, FInteraction of OST1 and AtANN1 detected by Co‐IP assays in Arabidopsis. Twelve‐day‐old OST1‐Myc overexpressing plants grown on MS medium at 22°C were placed at 4°C for 0, 0.5, 2 h, and total proteins were extracted and immunoprecipitated with anti‐Myc agarose beads. The wild type (Col‐0) treated with 4°C for 2 h was used as control. The OST1‐Myc protein was detected with anti‐Myc antibody, and the AtANN1 protein was detected with anti‐AtANN1 antibody. Representative pictures are shown in (E) and relative protein level in (F).

-

GCo‐IP assay showing the interaction between OST1 and AtANN1 in vivo. The construct combinations were expressed in N. benthamiana leaves. Total proteins were extracted after the N. benthamiana leaves treated with 4°C or 22°C and immunoprecipitated with anti‐Myc agarose beads. The proteins were detected with anti‐Myc and anti‐GFP antibodies.

Data information: In (A and B), the data represent means ± SD of 20 seedlings. Three independent experiments showed a similar result. In (F), the data represent means ± SD of three technical replicates. Different letters represent significant difference at P < 0.05 (one‐way ANOVA). In (C–G), representative data were shown, and at least three independent experiments showed a similar result.

Source data are available online for this figure.

We also measured [Ca2+]cyt in atann4‐1 mutant expressing aequorin with and without cold shock, and observed a similar scenario as noted for atann1: The cold shock‐induced increase in [Ca2+]cyt was lower in atann4‐1 than in the wild type (Fig EV2F). Together, these results indicate that AtANN1 and AtANN4 are important for mediating a rapid increase in [Ca2+]cyt upon cold stress.

AtANN1 interacts with OST1

We further dissected the effects of cold stress on AtANN1 mRNA and AtANN1 protein levels and found that AtANN1 transcript levels and protein levels were not obviously affected by cold stress (Appendix Fig S1 A and B).

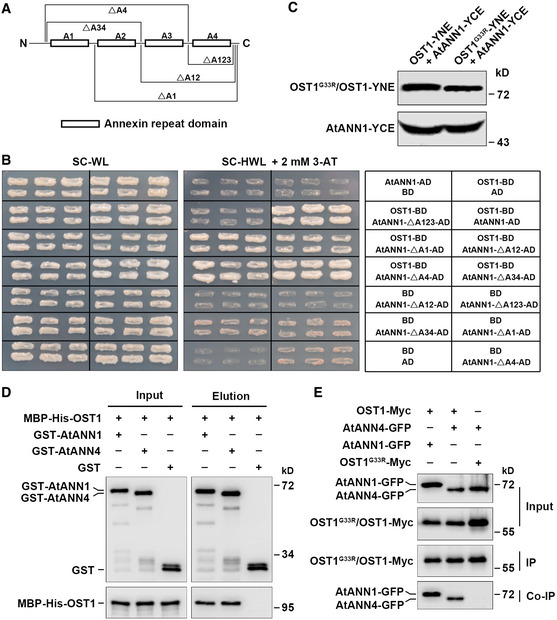

To explore how AtANN1 functions in cold response, we pursued to identify the interacting proteins of AtANN1. In our previous liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC‐MS/MS) analysis using transgenic plants overexpressing OST1‐Myc to identify OST1‐interacting proteins (Ding et al, 2015; Ding et al, 2018), AtANN1 was one of the candidate interacting proteins (Appendix Table S1). To verify the interaction between AtANN1 and OST1, we performed yeast two‐hybrid assays and observed that AtANN1 interacted with OST1 in yeast cells (Fig EV3A and B). AtANN1 has four annexin repeat domains (A1–A4). When A1, A12, A34, or A4 was deleted, the truncated proteins could interact with OST1 in yeast; however, the truncated protein failed to interact with OST1 when the first three domains were deleted (Fig EV3A and B). These results suggest that any one of the first three annexin repeat domains are sufficient for their interaction in yeast. In vitro pull‐down assays showed that GST‐OST1, but not GST, pulled down MBP‐His‐AtANN1 protein (Fig 2C). Interestingly, we found that OST1G33R, a form of OST1 with no kinase activity (Belin et al, 2006), failed to directly interact with MBP‐His‐AtANN1 in vitro (Fig 2C), possibly due to the lost kinase activity or conformation change caused by this mutation of OST1.

Figure EV3. AtANN1 and AtANN4 interact with OST1.

- Diagram of AtANN1‐truncated proteins used for the yeast two‐hybrid assays described in (B).

- The interaction of OST1 and AtANN1 in yeast cells. Yeast cells were grown on SC/–Trp/–Leu (–WL) medium for 2 days or SC/–His/–Trp/–Leu (–HWL) medium supplemented with 2 mM 3‐AT for 4 days.

- The protein level of AtANN1 and OST1/OST1G33R in BiFC assays described in Fig 2D. OST1‐YNE and OST1G33R‐YNE proteins were detected with anti‐Myc antibody. AtANN1‐YCE protein was detected with anti‐HA antibody.

- GST pull‐down assay showing that OST1 interacts with AtANN4 in vitro. Purified recombinant GST‐AtANN1, GST‐AtANN4, or GST proteins from E. coli were immunoprecipitated with GST beads and then incubated with MBP‐His‐OST1. Precipitated proteins were detected with anti‐GST and anti‐His antibodies.

- Co‐IP assay showing the interaction between OST1 and AtANN4 in vivo. The construct combinations were expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Total proteins were extracted and immunoprecipitated with anti‐Myc agarose beads. The proteins were detected with anti‐Myc and anti‐GFP antibodies.

Source data are available online for this figure.

A recent study revealed that AtANN1‐GFP was enriched at the plasma membrane and vesicles of non‐dividing cells and in the mitotic and cytokinetic microtubular arrays of dividing cells. Furthermore, AtANN1‐GFP was localized to the cytoplasmic strands of pavement and stomatal guard cells of the leaf epidermis (Tichá et al, 2020) (Appendix Fig S1C), overlapping with the reported localization of OST1 (Belin et al, 2006). These data suggest that that AtANN1 and OST1 might interact in vivo. We then performed co‐immunoprecipitation (co‐IP) assays using proteins extracted from Nicotiana benthamiana leaves co‐expressing AtANN1‐GFP/OST1‐Myc, AtANN1‐GFP/OST1G33R‐Myc, and AtANN1‐GFP/Myc and further confirmed that AtANN1‐GFP interacts with OST1‐Myc, but not with OST1G33R‐Myc in plants (Fig 2E). In planta interaction between AtANN1 and OST1 was confirmed by bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays in N. benthamiana epidermal cells confirmed the AtANN1‐OST1 interaction signals were overlapped with PIP2‐mcherry signals, a marker of plasma membrane (Entzian & Schubert, 2016) (Fig 2D). However, no interaction was observed between AtANN1 and OST1G33R (Fig 2D), although the respective fusion proteins were properly expressed (Fig EV3C). Furthermore, AtANN4 was shown to interact with OST1 in vitro and in vivo (Fig EV3D and E).

To examine whether the interaction between AtANN1 and OST1 is influenced by cold stress, we performed co‐IP assay using OST1‐Myc transgenic plants before and after cold treatment. Anti‐Myc agarose beads were used for IPed OST1‐Myc, and anti‐AtANN1 antibody was used to detect AtANN1 protein. Wild‐type Col‐0 was used as a control. We observed that AtANN1 was associated with OST1 and that this association was enhanced by treatment at 4°C (Fig 2E and F). This result was further verified by co‐IP assays using N. benthamiana leaves expressing both OST1‐Myc and AtANN1‐GFP with and without cold treatment (Fig 2G). Taken together, these data indicate that AtANN1 interacts with OST1 in plants, and that this interaction is promoted under cold stress.

AtANN1 acts downstream of OST1 to positively regulate freezing tolerance

To determine the genetic interaction between OST1 and AtANN1, we generated ost1‐3 atann1 mutants by crossing ost1‐3 and atann1 single mutants, and performed freezing tolerance assays. The ost1‐3 and atann1 single mutants displayed freezing hypersensitivity compared to the wild type under both acclimation and non‐acclimation conditions (Fig 3A–C). The ost1‐3 atann1 double mutants showed no greater decrease in freezing tolerance than that observed in atann1 and ost1‐3, indicating the effects of the two mutations were not additive (Fig 3A–C). Furthermore, we generated OST1‐Myc atann1 by crossing OST1‐Myc transgenic plants with atann1 mutant (Fig 3D and E). We found that OST1‐Myc transgenic plants exhibited enhanced freezing tolerance, which is consistent with the previous study (Ding et al, 2015). However, overexpression of OST1 failed to rescue the freezing sensitivity of atann1 (Fig 3F–H). These results collectively reveal that AtANN1 acts downstream of OST1 to positively regulate the plant freezing tolerance.

Figure 3. Genetic analysis of OST1 and AtANN1 .

-

A–CFreezing phenotype (A), survival rate (B), and ion leakage (C) of Col‐0, ost1‐3, atann1, and atann1 ost1‐3. Twelve‐day‐old plants grown on MS medium at 22°C were exposed to freezing temperatures (NA, −5°C, 30 min; CA, −8°C, 40 min). Representative pictures are shown in (A).

-

D, EOST1 gene expression (D) and protein levels of OST1 and AtANN1 (E) in Col‐0, OST1‐Myc, atann1, and OST1‐Myc atann1. OST1 and AtANN1 proteins were detected with anti‐Myc and anti‐AtANN1 antibodies. HSP90 was used as a control.

-

F–HFreezing phenotype (F), survival rate (G), and ion leakage (H) of Col‐0, OST1‐Myc, atann1 and OST1‐Myc atann1. 12‐day‐old plants grown on MS medium at 22°C were exposed to freezing temperatures (NA, −5°C, 30 min; CA, −8°C, 40 min). Representative pictures are shown in (F).

Data information: In (B, C, G and H), the data represent means ± SE of three independent experiments, each with three technical repeats (n = 19 seedlings for each repeat). Different letters represent significant difference at P < 0.05 (one‐way ANOVA). In (D), the data represent means ± SD of three technical replicates.

Source data are available online for this figure.

OST1 phosphorylates AtANN1 under cold stress

Given that OST1 interacts with AtANN1 and AtANN4, we asked whether OST1 phosphorylates AtANN1 and AtANN4. In vitro phosphorylation assays showed that AtANN1 and AtANN4 were directly phosphorylated by OST1 (Fig 4A and B). We also performed in‐gel kinase assays using GST‐AtANN1 as the substrate and total proteins extracted from wild‐type Col‐0 and the ost1‐3 knockout mutant with or without cold treatment. OST1 kinase activity was clearly detected in wild‐type Col‐0 but not in ost1‐3 mutant after cold treatment when GST‐AtANN1 served as the substrate (Fig 4C), suggesting that the cold‐activated OST1 phosphorylates AtANN1.

Figure 4. AtANN1 is phosphorylated by OST1 at S289.

-

A, BOST1 phosphorylates AtANN1 (A) and AtANN4 (B) in vitro. Purified recombinant MBP‐His‐OST1 was incubated with GST‐AtANN1, GST‐AtANN4, or GST in kinase reaction buffer with 1 µCi [γ‐32P] ATP for 30 min at 30°C, followed by separation with SDS–PAGE. Phosphorylated AtANN1 and AtANN4 were detected by autoradiography. Recombinant OST1, AtANN1, and AtANN4 were stained by Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB).

-

CIn‐gel kinase assays of OST1 in Col‐0 and ost1‐3 mutant under cold stress. Twelve‐day‐old Col‐0 and ost1‐3 mutant were treated at 4°C for 2 h. Total protein extracts were prepared and separated on a SDS–PAGE gel containing 0.2 mg/ml GST‐AtANN1 as a substrate and incubated with 70 µCi [γ‐32P] ATP. Top, autoradiograph; bottom, CBB staining.

-

DIn vitro kinase analysis of the indicated mutant forms of AtANN1 by OST1. After phosphorylation, the proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE and subjected to autoradiography. Top, autoradiograph; bottom, CBB staining.

-

EOST1 phosphorylates AtANN1 at S289 in vivo in LC/MS analysis. Total proteins were extracted from 12‐day‐old AtANN1‐Myc overexpressing plants treated at 4°C for 0, 10, 30, and 120 min, followed by trypsin digestion. Phosphopeptides were enriched for mass spectrometry analysis. Representative picture for 10 min was shown.

Data information: In (A–C), representative data were shown, and three independent experiments showed a similar result.

Source data are available online for this figure.

To further determine the phosphorylation residues of AtANN1 by OST1, we first generated a series of mutant constructs that inactivated each conserved putative phosphorylation site in AtANN1 with a serine/threonine to alanine substitution (AtANN1S101A, AtANN1S194A, AtANN1S289A, AtANN1T116A, and AtANN1T270A) and performed in vitro phosphorylation assays using these mutated proteins as substrates. Compared to the wild‐type AtANN1, the phosphorylation of AtANN1S101A, AtANN1S194A, AtANN1T116A, and AtANN1T270A by OST1 was decreased to different extent, whereas the phosphorylation of AtANN1S289A was largely abolished (Fig 4D). These assays suggested that S289 is a major residue for phosphorylation of AtANN1 by OST1, and the other four residues may have a minor contribution to the AtANN1 phosphorylation by OST1. In vitro LC‐MS/MS assays further confirmed the phosphorylation of AtANN1S289 by OST1 (Appendix Fig S2A).

We then performed a LC‐MS/MS assay using AtANN1‐Myc and AtANN1‐Myc ost1‐3 transgenic plants before and after cold treatment to determine whether AtANN1 is phosphorylated by OST1 in vivo. AtANN1 was phosphorylated at Ser289 in the AtANN1‐Myc transgenic plants after cold treatment at 4°C for 10, 30, and 120 min, but not in the AtANN1‐Myc transgenic plants without cold treatment or in the AtANN1‐Myc ost1‐3 transgenic plants with or without cold treatment (Fig 4E, and Appendix S2B). Taken together, these data collectively suggest that OST1 phosphorylates AtANN1 predominantly at Ser289 under cold conditions.

To dissect the biological function of AtANN1 phosphorylation in plants, we transformed the atann1 mutant with AtANN1:AtANN1S289A‐GFP and AtANN1:AtANN1S289E‐GFP (carrying the serine to glutamine mutation, a phosphomimic form of AtANN1), and examined the freezing tolerance of these transgenic plants. Both gene expression and protein analyses showed that they were expressed (Appendix Fig S2C and D). Like the wild‐type AtANN1 (Fig 1A–C), the survival rate and ion leakage of atann1 were fully rescued by the phosphomimic form AtANN1 S289E in two independent atann1 AtANN1 S289E lines (#5 and #7; Fig 5A–C, and Appendix Fig S3), but were not complemented by the non‐phosphorylatable form AtANN1S289A after freezing treatment (Fig 5D–F, and Appendix Fig S4). These data suggest that phosphorylation of AtANN1 at Ser289 is required for its function in regulating freezing tolerance.

Figure 5. The phosphorylation of AtANN1 by OST1 is required for plant freezing tolerances.

-

A–CFreezing phenotype (A), survival rate (B), and ion leakage (C) of Col‐0, atann1, and atann1 AtANN1S289E (#5) plants. 12‐day‐old plants grown on MS medium at 22°C were exposed to freezing temperatures (NA, −5°C, 30 min; CA, −8°C, 40 min). Representative pictures are shown in (A).

-

D–FFreezing phenotype (D), survival rate (E), and ion leakage (F) of Col‐0, Atann1, and atann1 AtANN1S289A (#16) plants. 12‐day‐old plants grown on MS medium at 22°C were exposed to freezing temperatures (NA, −5°C, 30 min; CA, −8°C, 40 min). Representative pictures are shown in (D).

Data information: In (B, C, E and F), the data represent means ± SE of three independent experiments, each with three technical repeats (n = 25 seedlings for each repeat). **P < 0.01, two‐tailed t‐test.

The Ca2+ transport activity of AtANN1 is enhanced by OST1

Next, we next examined whether OST1 can modulate the Ca2+ transport activity of AtANN1, using electrophysiological assays of AtANN1 in Xenopus oocytes microinjected with AtANN1 cRNA. Because Ba2+ has been used extensively for Ca2+ channel identification (Hamilton et al, 2000; Pei et al, 2000; Zhang et al, 2007), we used Ba2+ as the major charge‐carrying ion to measure Ca2+ channel‐like activity in the electrophysiological assays.

Control oocytes injected with ddH2O alone did not produce obvious currents, with or without 30 mM Ba2+ in the bathing solution, and oocytes injected with AtANN1 alone likewise failed to elicit currents in the absence of Ba2+ (Fig 6A and B). In the presence of 30 mM Ba2+, however, expression of AtANN1 produced substantial currents (Fig 6A and B). In addition, the currents produced by AtANN1 were fully blocked by LaCl3 (Fig 6A and B). These data suggest that AtANN1 has Ca2+ transport activity in Xenopus oocytes, which is consistent with the previous findings for AtANN1 in root cells (Laohavisit et al, 2012). The Ba2+ currents produced in Xenopus oocytes co‐expressing AtANN1 and OST1 were greater than those produced by expression of AtANN1 alone (Fig 6A–C), and similar results were obtained when 30 mM Ca2+ was used instead of Ba2+ (Fig EV4A–C). These data indicate that OST1 enhances the Ca2+ transport activity of AtANN1.

Figure 6. The Ca2+ transport activity of AtANN1 is enhanced by OST1.

- AtANN1 current recordings in Xenopus oocytes. Whole‐cell currents were recorded in Xenopus oocytes injected with ddH2O or with AtANN1, OST1, or AtANN1 + OST1 cRNA. Bath solution was described in Materials and Methods. The voltage protocol as well as time and current scale bars for the recordings are shown.

- Current–voltage (I–V) relationship of the steady‐state whole‐cell currents in Xenopus oocytes described in (A). Negative current is influx of cations into the oocytes.

- Percentage of total Xenophus oocytes in different nA range according to (A).

- AtANN1 current recordings in oocytes. Whole‐cell currents were recorded in Xenopus oocytes injected with ddH2O or with AtANN1, AtANN1 S289A, OST1, AtANN1 + OST1, and AtANN1 S289A + OST1 cRNA.

- Current–voltage (I–V) relationship of the steady‐state whole‐cell currents in Xenopus oocytes described in (D).

- Percentage of total Xenophus oocytes in different nA range according to (D).

Data information: In (A and D), representative data were shown. In (B and E), the data represent means ± SD of five oocytes. Three independent experiments showed a similar result.

Figure EV4. The Ca2+ transport activity of AtANN1 is enhanced by OST1.

- AtANN1 current recordings in Xenophus oocytes. Whole‐cell currents were recorded in oocytes with injection of cRNA of ddH2O, AtANN1, OST1 and AtANN1 + OST1.

- Current‐voltage (I–V) relationship of the steady‐state whole‐cell currents in Xenopus oocytes described in (A). Negative current is influx of cations into the oocytes.

- Percentage of total Xenophus oocytes in different nA range according to (A).

- Time‐course analysis of cytosolic free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) dynamics in 10‐day‐old wild‐type (Col‐0) and ost1‐3 mutant after treatment with 22°C water or 22°C water containing 10 mM LaCl3 (arrow shows the time point of treatment). Luminescence was recorded at 1‐s intervals. Quantification of the cold‐induced [Ca2+]cyt changes shown in the top. Peak [Ca2+]cyt in the bottom indicates the highest [Ca2+]cyt after treatment.

- The protein level of GST, GST‐AtANN1, GST‐AtANN1S289A, and GST‐AtANN1S289E in MST assays described in Fig 7C.

Data information: In (B), the data represent means ± SD of 5 oocytes. Three independent experiments showed a similar result. In (D), the data represent means ± SD of 20 seedlings. Three independent experiments showed a similar result.

Source data are available online for this figure

We next examined whether phosphorylation of AtANN1 by OST1 is the mechanism by which OST1 enhances AtANN1's Ca2+ transport activity. To test this possibility, we performed electrophysiological assays on Xenopus oocytes expressing AtANN1, AtANN1S289A, OST1/AtANN1, and OST1/AtANN1S289A. Both AtANN1 and AtANN1S289A had Ca2+ transport activity; however, the transport activity of AtANN1, but not AtANN1S289A, was enhanced by OST1 (Fig 6D–F). These data demonstrate that OST1 phosphorylates AtANN1 to enhance its Ca2+ transport activity.

We next examined whether OST1 regulates Ca2+ influx in response to cold stress by measuring Ca2+ levels in wild‐type and ost1‐3 mutant plants expressing aequorin with or without cold shock. There was no obvious difference of the [Ca2+]cyt in wild‐type and ost1‐3 mutant without cold shock (Fig EV4D). However, the [Ca2+]cyt was significantly lower in the ost1‐3 mutant than in the wild type after cold treatment (Fig 7A and B). Moreover, the cold shock‐induced increase in [Ca2+]cyt was also inhibited by LaCl3 (Fig 7A and B). These results collectively support the idea that OST1 regulates the cold‐induced increase in [Ca2+]cyt at least partially by phosphorylating the Ca2+‐permeable transporter AtANN1.

Figure 7. Phosphorylation of AtANN1 by OST1 promotes its Ca2+‐binding activity.

- Time‐course analysis of [Ca2+]cyt dynamics between 10‐day‐old wild‐type (Col‐0) and ost1‐3 mutant after treatment with ice‐cold water or ice‐cold water containing 10 mM LaCl3 (arrow shows the time point of treatment). Luminescence was recorded at 1‐s intervals.

- Quantification of the cold‐induced [Ca2+]cyt changes shown in (A). Peak [Ca2+]cyt indicates the highest [Ca2+]cyt after treatment.

- MST assays of the calcium‐binding affinity of GST‐AtANN1, GST‐AtANN1S289A, and GST‐AtANN1S289E. GST was used as a control.

- A proposed working model. Under normal conditions, OST1 protein kinase interacts with PP2C, which inhibits the kinase activity of OST1. AtANN1 is localized in the cytosol and at the plasma membrane. Under cold stress, OST1 is activated and phosphorylates AtANN1, which, on the one hand, enhances the Ca2+ transport activity of AtANN1, and, on the other, promotes the Ca2+‐binding activity of AtANN1. This dual role of phosphorylation results in increased cold stress‐induced [Ca2+]cyt. Consequently, AtANN1 indirectly facilitates the expression of CBFs and CORs to positively regulate plant freezing tolerance.

Data information: In (A and B), the data represent means ± SD of 20 seedlings (**P < 0.01, student t‐test). Three independent experiments showed a similar result. In (C), the data represent means ± SD of three biological replicates.

Previous studies suggest that the Ca2+‐binding affinity of annexins is regulated by their phosphorylation state (Konopka‐Postupolska et al, 2011; Ma et al, 2019). We thus examined whether the mutation of S289 of AtANN1 affects its Ca2+‐binding activity using Microscale Thermophoresis (MST) assays. The non‐phosphorylatable form GST‐AtANN1S289A had reduced Ca2+‐binding activity, whereas the phosphomimic form GST‐AtANN1S289E had slightly enhanced Ca2+‐binding activity compared to GST‐AtANN1 (Figs 7C and EV4E). Therefore, it appears that phosphorylation of AtANN1 at S289 modulates its Ca2+‐binding affinity; however, we cannot exclude the possibility that the reduced binding affinity of Ca2+‐AtANN1S289 might be caused by conformational changes of AtANN1 resulting from this mutation.

Discussion

Cold stress causes a dramatic and rapid increase in [Ca2+]cyt, which is required for proper COR gene expression (Knight et al, 1991; Knight et al, 1996). In this study, we report that the Ca2+ transporter AtANN1 is involved in cold‐induced elevation of [Ca2+]cyt. Biochemical and genetic evidence demonstrates that plasma membrane‐localized AtANN1 mediates rapid Ca2+ influx from apoplastic Ca2+ stores into the cytosol under cold stress and positively regulates COR expression and plant tolerance to freezing stress. In addition, OST1 is activated under cold stress and phosphorylates AtANN1 at Ser289, which enhances its Ca2+ transport activity, thereby potentially amplifying the Ca2+ signaling (Fig 7D).

It is well established that the transient [Ca2+]cyt elevation in plants occurs seconds after cold shock (Knight et al, 1991); however, due to the relatively low sensitivity of in‐gel kinase assays, the cold‐activated OST1 activity was barely detected within 30 min using this assay. Therefore, we instead used an IP‐MS/MS assay to assess OST1‐mediated AtANN1 phosphorylation in planta. We detected phosphorylation at Ser289 of AtANN1 in the 10‐min cold‐treated AtANN1‐Myc plants, but not in the non‐treated plants or in the AtANN1‐Myc ost1‐3 plants with or without cold treatment. These results suggest that OST1‐mediated phosphorylation of AtANN1 occurs within several minutes or possibly even within less time. OST1 has basal kinase activity under normal conditions (Ding et al, 2015), and this basal activity may also function in regulating AtANN1 activity. In addition, a previous study showed that continuous cold stimulation induces a biphasic increase in [Ca2+]cyt, with the first peak occurring within several seconds and second at several minutes (Short et al, 2012). Therefore, we propose that, besides affecting the first transient increase in [Ca2+]cyt, cold‐activated OST1 phosphorylates and enhances the Ca2+ transport activity of AtANN1, which consequently magnifies the second [Ca2+]cyt elevation under cold stress. Alternatively, considering that the cold‐induced cytoplasmic Ca2+ influx exhibits diurnal variation in guard cells, and circadian modulation of cold‐induced whole plant [Ca2+]cyt increases is correlated to the circadian pattern of RD29A induction (Dodd et al, 2006), it is possible cold‐activated OST1 regulates AtANN1‐mediated cytosolic calcium oscillations or circadian oscillations in the guard cells or whole plant under long‐term cold treatment. These hypotheses await further investigation. Our in‐gel kinase assay suggested that AtANN1 can also be phosphorylated by kinases other that OST1, possibly including other SnRK2s and CRPK1 (around 43 kDa) (Liu et al, 2017) and RAF2 (around 100 kDa). Three recent studies reported that RAF‐mediated activation of OST1 is required for ABA signaling and the osmotic stress response (Lin et al, 2020; Soma et al, 2020; Takahashi et al, 2020). Future studies should examine whether these kinases mediate AtANN1 phosphorylation and thereby modulate its Ca2+ transport activity under cold conditions.

Annexins have phospholipid‐ and Ca2+‐binding activities that are important for plant responses to stress (Morgan et al, 2006; Laohavisit & Davies, 2011). Previous studies demonstrated that AtANN1 acts as a Ca2+‐permeable channel‐like transporter with a role in regulating Ca2+ influx into the cytosol under salt and oxidative stress conditions (Lee et al, 2004; Laohavisit et al, 2012; Richards et al, 2014). AtANN4 was shown to promote Ca2+ influx under salt stress to activate the SOS pathway (Ma et al, 2019). In this study, we established that AtANN1 also functions as a Ca2+‐permeable channel‐like transporter in the plant response to cold stress. It should be noted that the cold‐induced increase in [Ca2+]cyt is not fully repressed in the atann1 mutant. This may be due to functional redundancy, as AtANN1 has seven homologs in Arabidopsis (Cantero et al, 2006). Indeed, we established that AtANN4 also modulates the cold‐induced increase in [Ca2+]cyt and freezing tolerance. It is worth noting that the Arabidopsis genome includes over 40 genes encoding putative Ca2+ channels (Ward et al, 2009). A previous study demonstrated that the Ca2+‐permeable mechanosensitive channels MCA1 and MCA2 mediate Ca2+ influx under cold stress (Mori et al, 2018). Therefore, some other Ca2+‐permeable transporters or channels may also regulate Ca2+ influx under cold stress.

Besides having Ca2+‐binding activity, plant annexins have sequences that strongly resemble the heme‐binding region of horseradish peroxidase, suggesting that they might also have peroxidase activity (Gorecka et al, 2005; Laohavisit et al, 2009; Qiao et al, 2015). In addition, overexpression of OsANN1 enhances thermotolerance by regulating H2O2 content and redox homeostasis (Qiao et al, 2015). These results suggest that the peroxidase activity of annexins may be important for their functions in plant responses to abiotic stress. In this study, we established that AtANN1 not only mediates cold acclimation in a CBF‐dependent manner, but also mediates basal freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. However, the mechanism by which AtANN1 regulates basal freezing tolerance is unknown. Considering that plant annexins might have peroxidase activity and the ROS play key roles in plant basal freezing tolerance (Laohavisit et al, 2009; Costa‐Broseta et al, 2018), it is possible that AtANN1 positively regulates plant basal freezing tolerance by inhibiting ROS overproduction.

Expression of the cold‐regulated gene KIN1 is regulated by Ca2+ influx under cold stress (Knight et al, 1996). Here we showed that loss of AtANN1 decreases the cold‐induced expression of CBFs and their downstream genes, GOLS3, COR15B, COR47, and KIN1. These results further support the importance of Ca2+ for cold‐responsive gene expression. However, it remains unclear how the AtANN1‐mediated Ca2+ signal regulates cold‐responsive gene expression. The Arabidopsis genome encodes many calmodulin (CaM)‐binding proteins (Reddy et al, 2011; Virdi et al, 2015; Edel et al, 2017), any of which could be involved in transducing the Ca2+ signal. CaM has two Ca2+‐binding domains, each consisting of paired EF‐hands, one at the N‐terminus and the other at the C‐terminus (Finn & Forsen, 1995). Some transcription factors (TFs) bind to Ca2+‐CaM, which allows the TFs to sense Ca2+ signals through a Ca2+‐CaM‐TF module. This mechanism may rapidly translate Ca2+ signals induced by environmental cues into changes in gene expression. In Arabidopsis, calmodulin‐binding transcription activator (CAMTA) family members, particularly CAMTA3, have been reported to regulate plant freezing tolerance by activating CBF expression (Doherty et al, 2009; Kim et al, 2013; Kidokoro et al, 2017). It will be interesting to explore whether Ca2+ regulates CAMTA activity and whether CAMTA3 plays a role in modulating cold‐responsive gene expression mediated by AtANN1. In addition to TFs, several Ca2+‐binding proteins, such as Ca2+‐dependent protein kinases (CDPKs), Calcineurin B‐like proteins (CBLs), and CBL‐interacting protein kinases (CIPKs), are reported to be involved in cold tolerance in plants (Kim et al, 2003; Liu et al, 2008; Liu et al, 2018b; Zhang et al, 2019). Whether these proteins are responsible for decoding specific cold‐induced Ca2+ signals merits further investigation.

Calcium spiking is a distinct behavior characterized by sharp increases in [Ca2+]cyt induced by abiotic and biotic stress, followed by decreases back to the basal level, even in the continued presence of the stimulus (Kudla et al, 2018). Therefore, the activity of calcium channels or transporters should be tightly controlled in plants. We found that the AtANN1 activity is promoted by OST1 under cold stress; however, it remains unknown how its activity is blocked in the attenuate stage. Upon long exposure of salt stress, SOS2‐mediated phosphorylation of AtANN4 was shown to be promoted by SCaBP8, which enhances the AtANN4‐SCaBP8 interaction, thereby consequently repressing AtANN4 activity (Ma et al, 2019). Recent findings have provided evidence that the activities of Ca2+ channels are controlled by CaMs and protein kinases (Ma et al, 2019; Tian et al, 2019; Yu et al, 2019). Moreover, the expression of AtANN genes are negatively regulated by MYB30 in response to heat stress (Liao et al, 2017). These findings may provide us with a strategy to study the mechanism by which Ca2+ transport activity of AtANN1 is repressed under non‐stress conditions.

Materials and Methods

Plants materials and growth conditions

The Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia‐0 and all plants used in this study were grown on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (Sigma‐Aldrich) containing 0.8% (w/v) agar and 2% (w/v) sucrose at 22°C under long‐day conditions (16‐h light/8‐h dark cycle). T‐DNA insertion mutants, atann1 (Salk_015426) (Lee et al, 2004; Laohavisit et al, 2012), ann1‐2 mutant (SAIL_414_C01) (Wang et al, 2015), atann4‐1 and atann4‐2 (Ma et al, 2019), and ost1‐3 (Salk_008068) (Ding et al, 2015), were used in this study. In addition, wild‐type Col‐0, atann1 mutants and the atann1 complemented line (atann1 AtANN1 #10) harboring aequorin were described previously (Laohavisit et al, 2012; Wang et al, 2015). ost1‐3 mutant harboring aequorin was generated by crossing ost1‐3 with wild‐type Col‐0 plants harboring aequorin described (Knight et al, 1991).

Plasmid construction and plant transformation

AtANN1 cDNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and cloned into pSuper1300, pGEX‐6P‐1, pMAL‐c2, YFPC (based on pGEMHE vector), and pGADT7 vectors to generate Super:AtANN1‐Myc, Super:AtANN1‐GFP, GST‐AtANN1, MBP‐His‐AtANN1, AtANN1‐YFPC and AtANN1‐pGADT7 (AtANN1‐AD) constructs, respectively. AtANN1 promoter fragment (1,566 bp) together with its genomic DNA was amplified and fused with GFP in the pCAMBIA1300 vector to obtain the desired constructs, AtANN1:AtANN1‐GFP, AtANN1:AtANN1S289A‐GFP (carrying a S289A mutation of AtANN1), and AtANN1:AtANN1S289E‐GFP (carrying a S289E mutation of AtANN1).

Using AtANN1‐pGEX‐6P‐1 plasmid as a template, site‐directed mutagenesis was carried out to obtain the mutated forms of AtANN1. They were amplified and cloned into pGEX‐6P‐1 vector to generate GST‐AtANN1S101A, GST‐AtANN1S194A, GST‐AtANN1S289A, GST‐AtANN1T116A, and GST‐AtANN1T270A constructs.

OST1 cDNA was amplified and cloned into pMAL‐c2 to obtain MBP‐His‐OST1 constructs. Using OST1‐pGEX‐4T‐1, OST1‐YNE and Super:OST1‐Myc (Ding et al, 2015) constructs as templates, site‐directed mutagenesis was performed to generate the kinase dead form of OST1. Then they were amplified and cloned into pGEX‐4T‐1, pSPYNE‐35S or pSuper1300 to create OST1G33R‐pGEX‐4T‐1, OST1G33R‐YNE and Super:OST1G33R‐Myc constructs. All primers used were listed in Appendix Table S2, and all vectors and constructs were listed in Appendix Table S3.

The Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101, which was transformed into the related constructs, was transformed into Arabidopsis plants. AtANN1:AtANN1‐GFP, AtANN1:AtANN1S289A‐GFP, and AtANN1:AtANN1S289E‐GFP constructs were transformed into the atann1 mutant. The transgenic plants were selected on MS medium containing hygromycin B. T3 or T4 homozygous transgenic plants were used in this study.

atann1 AtANN1 plants were transformed by floral dip to express cytosolic (apo)aequorin driven by the 35S promoter. The pGreen vector based on pMAQ containing 35S:Aequorin was transferred into A. tumefaciens GV3101 (Knight et al, 1991). All plants used in aequorin assays were at least three generations post‐transformation, and discharge levels were equivalent across genotypes.

[Ca2+]cyt determination

The [Ca2+]cyt determination assays were performed as previously described (Liao et al, 2017) with some modifications. The 10‐day‐old seedlings grown on MS medium were used for [Ca2+]cyt determination. First, the seedlings were soaked in 200 µl coelenterazine solution (final concentration 10 µM, 1% [v/v] ethanol, and 0.1% [v/v] Triton X‐100) in 1.5‐ml tubes for 5 h at 22°C in the dark (Knight et al, 1991). Experiments were performed without liquid in the tubes. Luminescence counts were recorded every 1 s. After 10 s of counting, 200 µl of ice‐cold water was injected into the tube in the luminometer sample housing. After 120 s of counting, the remaining aequorin was discharged by the addition of 200 µl discharge solution (containing 2 M CaCl2 and 20% [v/v] ethanol) for 120 s. The quantification of [Ca2+]cyt was performed as described (Rentel & Knight, 2004).

Freezing tolerance and ion leakage assays

The freezing tolerance and ion leakage assays were performed as previously described (Ding et al, 2015) with some modifications. Briefly, 12‐day‐old Arabidopsis seedlings grown on MS medium were treated with or without cold acclimation at 4°C for 3 days and then put into a freezing chamber (RUMED4501) when its temperature reached 0°C. Then, the temperature dropped by 1°C per hour until the desired temperature was reached. After freezing treatment, the seedlings were transferred to 4°C chamber in the dark for 12 h and then transferred to normal conditions for 3 days for recovery. The survival rates of the seedlings were counted by the ratio of the number of living seedlings to the number of total seedlings.

After 3‐day recovery, seedlings were soaked in 5 ml deionized water (sample S0) in 15 ml tubes, which were shaken at 22°C for 1 h. After that, the electrical conductivity was detected as S1. Next, the samples were heated at 100°C for 1 h, followed by shaking at 22°C for 1 h; the electrical conductivity was measured as S2. The ion leakage was calculated as (S1 − S0)/(S2 − S0) × 100%.

Quantitative real‐time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) from 12‐day‐old Arabidopsis seedlings grown on MS medium with or without cold treatment. Total RNA (3 µg) was treated with RNase‐free DNase I (Takara) to remove genomic DNA and then reverse‐transcribed with the M‐MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega). Quantitative real‐time PCR was carried out using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Takara) on a 7500 Real‐Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The method for calculating gene expression was performed as described (Shi et al, 2012).

Yeast two‐hybrid assays

The yeast two‐hybrid assays were performed as described (Ding et al, 2015). In brief, AtANN1‐pGADT7 and OST1‐pGBKT7, AtANN1‐ΔA1‐pGADT7, and OST1‐pGBKT7, AtANN1‐ΔA12‐pGADT7 and OST1‐pGBKT7, AtANN1‐ΔA123‐pGADT7 and OST1‐pGBKT7, AtANN1‐ΔA34‐pGADT7 and OST1‐pGBKT7, AtANN1‐ΔA4‐pGADT7 and OST1‐pGBKT7, AtANN1‐pGADT7 and pGBKT7 or OST1‐pGBKT7 and pGADT7 were transformed into the yeast strain AH109. The yeast cells were grown on SC–Leu–Trp (Clontech, 2 days at 28°C) or SC–Leu–Trp–His medium supplemented with 2 mM 3‐AT (Clontech, 4 days at 28°C).

In vitro pull‐down assays

The pull‐down assays were performed as described (Ding et al, 2015). Purified GST‐OST1, GST‐OST1G33R or GST proteins (10 µg) were incubated with GST agarose beads in PBS buffer containing 0.3% (v/v) NP‐40 (pull‐down binding buffer) at 4°C for 2 h and then washed with pull‐down binding buffer. The immunoprecipitated GST‐OST1, GST‐OST1G33R, or GST was incubated with 2 µg MBP‐His‐AtANN1 at 4°C for 2 h in pull‐down binding buffer. After five washes, the proteins were analyzed by immunoblot analysis. Anti‐His antibody (Beijing Protein Innovation, #AbM59012‐18‐PU) was used to detect MBP‐His‐AtANN1, and anti‐GST antibody (Beijing Protein Innovation, #AbM59001‐2H5‐PU) was used to detect GST‐OST1 and GST‐OST1G33R.

Co‐immunoprecipitation assays

The co‐IP assays were performed as previously described (Ding et al, 2015). In short, the total proteins were extracted from N. benthamiana leaves expressing Super:AtANN1‐GFP/Super:OST1‐Myc, Super:AtANN1‐GFP/Super:OST1G33R‐Myc or Super:AtANN1‐GFP/Super:Myc constructs with protein extraction buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2 and 0.1% [v/v] Triton X‐100) and then incubated with anti‐Myc agarose (Sigma‐Aldrich, #A7470) for 2 h at 4°C. After washing by protein extraction buffer for five times, the co‐immunoprecipitated products were separated by SDS–PAGE and detected with anti‐Myc (Sigma‐Aldrich, #M4439) and anti‐GFP (Abmart, #M20004H) antibodies.

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays

The constructs OST1‐YNE and AtANN1‐YCE or OST1G33R‐YNE and AtANN1‐YCE were transfected into N. benthamiana leaves for transient expression. The YFP fluorescence signal was detected by using a confocal microscope after 3‐day infiltration.

In vitro protein kinase assays

In vitro kinase assays were performed as previously described (Ding et al, 2015). The purified proteins MBP‐His‐OST1 together with GST‐AtANN1 or GST were incubated with kinase reaction buffer containing 20 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 50 µM ATP, and 1 µCi [γ‐32P] ATP at 30°C for 30 min and then heated at 100°C for 5 min with 5× loading buffer. The proteins were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and detected by Typhoon 9410 imager. Coomassie brilliant blue was used as a loading control.

In‐gel kinase assays

In‐gel kinase assays were performed as previously described (Ding et al, 2015). Total proteins were extracted from 12‐day‐old seedlings (control or exposed to 4°C) in protein extraction buffer containing 5 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 5 mM EGTA pH 8.0, 25 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 2 mM DTT, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 25 mM HEPES‐KOH pH 7.5. Then, the proteins were separated on a 10% (v/v) SDS–PAGE gel containing 0.2 mg/ml GST‐AtANN1. Then, the gel was washed three times with washing buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 0.5 mM DTT, 5 mM NaF, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 0.5 mg/ml BSA and 0.1% [v/v] Triton X‐100) at 22°C for 20 min each. The gel was incubated in renatured buffer containing 25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM NaF, and 0.1 mM Na3VO4 at 4°C for three stages, 1, 12, and 1 h. Next, the gel was incubated in kinase reaction buffer (40 mM HEPES‐KOH pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 12 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, and 2 mM EGTA) at 22°C for 30 min and then incubated in new kinase reaction buffer supplemented with 70 µCi [γ‐32P] ATP and 9 µl 1 mM cold ATP at 22°C for 1.5 h. The gel was washed five times by 5% (w/v) TCA and 1% (w/v) sodium pyrophosphate for 30 min each. The signal was detected by Typhoon 9410 imager.

Electrophysiological assays

The electrophysiological assays were performed as described (Xu et al, 2006). The cDNA sequence of OST1 was fused upstream of YFPN, and the sequence of AtANN1 or AtANN1S289A was fused upstream of YFPC in the pGEMHE vector (Geiger et al, 2009; Hua et al, 2012). The cRNAs of AtANN1‐YFPC, AtANN1S289A‐YFPC, and OST1‐YFPN were transcribed in vitro using the T7 RiboMAX Large Scale RNA Production System (Promega). The oocytes were injected with distilled water (40 nl, as a control), AtANN1 cRNA (20 ng in 40 nl), AtANN1S289A cRNA (20 ng in 40 nl), OST1 cRNA (20 ng in 40 nl), AtANN1 and OST1 cRNA mixture (10:10 ng in 40 nl), AtANN1S289A, and OST1 cRNA mixture (10:10 ng in 40 nl). Then, the injected oocytes were incubated in ND 96 solution containing 96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES‐KOH pH 7.5, and 1.8 mM CaCl2, and supplemented with 0.05 mg/ml gentamycin and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin at 17ºC for 2 days.

The two‐electrode voltage‐clamp technique was performed with a Gene‐Clamp 500B amplifier (Axon Instruments) at 22ºC. The microelectrodes were filled with 3 M KCl. The bath solution contained 2 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 185 mM mannitol, 10 mM MES‐Tris pH 5.5, supplemented with 30 mM BaCl2 (or CaCl2) before recording. The currents were digitized through a Digidata 1322A AC/DC converter with Clampex 9.0 software (Axon Instruments).

Mass spectrometry assays

To identify the putative phosphorylation site of AtANN1 by OST1 in vitro, 1 µg His‐OST1 and 10 µg GST‐AtANN1 purified proteins were incubated in 20 µl of protein kinase reaction buffer containing 20 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, and 50 µM ATP, at 30°C for 30 min. The reaction products were reduced by DTT and alkylated by IAM (Iodoacetamide), followed by digestion with trypsin (pH 8.5) at 37°C for 12 h. The results were analyzed by LC‐MS/MS as described (Liu et al, 2017).

For LC‐MS/MS analysis in vivo, total proteins were extracted from 12‐day‐old AtANN1‐Myc overexpressing line treated at 4°C for 10, 30 and 120 min. Protein digestion was performed using filter‐aided sample preparation (FASP) method with modifications (Wisniewski et al, 2009). Briefly, 100 µg proteins were dissolved with 50 mM ABC (NH4HCO3) solution, reduced by DTT at 56°C for 45 min and alkylated by IAM (Iodoacetamide) at 22°C for 30 min in the dark. The solution was transferred into a 10 K ultrafiltration tube (Vivacon 500, Satrorius), spinned at 14,000 g for 20 min with a new collection tube to collect digested peptides. The ABC solution was added into the ultrafiltration tube, and the digested peptide was washed into the collection tube. Phosphopeptides were enriched for LC‐MS/MS analysis.

Microscale thermophoresis assays

The microscale thermophoresis assays were performed as described (Entzian & Schubert, 2016; Ma et al, 2019). Briefly, the recombinant proteins were purified and replaced with PBST buffer (PBS, 0.005% Tween‐20, pH 7.4) using column A (Nano Temper Technologies). Then, 110 µl of 10 µM purified recombinant protein GST‐AtANN1, GST‐AtANN1S289A, GST‐AtANN1S289E or GST was labeled with 6 µl NHS NT‐647 dye in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. The labeled protein was collected by column B (Nano Temper Technologies) which was re‐equilibrated with HEPES buffer I (20 mM HEPES, 150 mM KCl, 0.5 mg/ml BSA, pH 7.4). The initial concentration of CaCl2 was 2 mM, and then was serially diluted with HEPES buffer II (20 mM HEPES, 150 mM KCl, pH 7.4). Finally, the serially diluted CaCl2 solution was mixed with 10 µl labeled protein. Samples were loaded into capillaries (Nano Temper Technologies) for analysis. The assays were performed with 20% LED power and 20% MST power. Signal thermophoresis and T‐jump data were used for calculating dissociation constant (K d).

Author contributions

SY directed the project. QL and SY designed the experiments. QL performed the experiments with the help of YD, YS, LM, YW, and KAW. QL, YD, CS, JMD, HK, MRK, ZG, YG, and SY discussed and interpreted the data. QL and YD draft the manuscript. JMD, HK, MRK, and SY revised the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Source Data for Expanded View and Appendix

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 2

Source Data for Figure 3

Source Data for Figure 4

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Zhen Li for helping with the LC‐MS/MS analysis and Dr. Adeeba Dark for technical support of aequorin lines. This work was supported by the grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (31920103002 and 31921001), the National Key Research and Development Project of China (SQ2020YFA050101‐02), the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council for funding (BB/K009869/1), and Beijing Outstanding University Discipline Program.

The EMBO Journal (2021) 40: e104559.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/) with the dataset identifier PXD022035.

References

- Belin C, de Franco PO, Bourbousse C, Chaignepain S, Schmitter JM, Vavasseur A, Giraudat J, Barbier‐Brygoo H, Thomine S (2006) Identification of features regulating OST1 kinase activity and OST1 function in guard cells. Plant Physiol 141: 1316–1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton G, Vazquez‐Tello A, Danyluk J, Sarhan F (2000) Two novel intrinsic annexins accumulate in wheat membranes in response to low temperature. Plant Cell Physiol 41: 177–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantero A, Barthakur S, Bushart TJ, Chou S, Morgan RO, Fernandez MP, Clark GB, Roux SJ (2006) Expression profiling of the Arabidopsis annexin gene family during germination, de‐etiolation and abiotic stress. Plant Physiol Biochem 44: 13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa‐Broseta A, Perea‐Resa C, Castillo MC, Ruiz MF, Salinas J, Leon J (2018) Nitric oxide controls constitutive freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis by attenuating the levels of osmoprotectants, stress‐related hormones and anthocyanins. Sci Rep 8: 9268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Li H, Zhang X, Xie Q, Gong Z, Yang S (2015) OST1 kinase modulates freezing tolerance by enhancing ICE1 stability in Arabidopsis . Dev Cell 32: 278–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Jia Y, Shi Y, Zhang X, Song C, Gong Z, Yang S (2018) OST1‐mediated BTF3L phosphorylation positively regulates CBFs during plant cold responses. EMBO J 37: e98228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Lv J, Shi Y, Gao J, Hua J, Song C, Gong Z, Yang S (2019) EGR2 phosphatase regulates OST1 kinase activity and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis . EMBO J 38: e99819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding YL, Shi YT, Yang SH (2020) Molecular Regulation of Plant Responses to Environmental Temperatures. Mol Plant 13: 544–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd AN, Jakobsen MK, Baker AJ, Telzerow A, Hou SW, Laplaze L, Barrot L, Poethig RS, Haseloff J, Webb AAR (2006) Time of day modulates low‐temperature Ca2+ signals in Arabidopsis . Plant J 48: 962–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd AN, Kudla J, Sanders D (2010) The language of calcium signaling. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61: 593–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty CJ, Van Buskirk HA, Myers SJ, Thomashow MF (2009) Roles for Arabidopsis CAMTA transcription factors in cold‐regulated gene expression and freezing tolerance. Plant Cell 21: 972–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edel KH, Marchadier E, Brownlee C, Kudla J, Hetherington AM (2017) The evolution of calcium‐based signalling in plants. Curr Biol 27: R667–R679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entzian C, Schubert T (2016) Studying small molecule‐aptamer interactions using MicroScale Thermophoresis (MST). Methods 97: 27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finka A, Cuendet AFH, Maathuis FJM, Saidi Y, Goloubinoff P (2012) Plasma membrane cyclic nucleotide gated calcium channels control land plant thermal sensing and acquired thermotolerance. Plant Cell 24: 3333–3348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn BE, Forsen S (1995) The evolving model of calmodulin structure, function and activation. Structure 3: 7–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furihata T, Maruyama K, Fujita Y, Umezawa T, Yoshida R, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi‐Shinozaki K (2006) Abscisic acid‐dependent multisite phosphorylation regulates the activity of a transcription activator AREB1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 1988–1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger D, Scherzer S, Mumm P, Stange A, Marten I, Bauer H, Ache P, Matschi S, Liese A, Al‐Rasheid KA et al (2009) Activity of guard cell anion channel SLAC1 is controlled by drought‐stress signaling kinase‐phosphatase pair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 21425–21430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorecka KM, Konopka‐Postupolska D, Hennig J, Buchet R, Pikula S (2005) Peroxidase activity of annexin 1 from Arabidopsis thaliana . Biochem Biophys Res Commun 336: 868–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo XY, Liu DF, Chong K (2018) Cold signaling in plants: insights into mechanisms and regulation. J Integr Plant Biol 60: 745–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton DWA, Hills A, Kohler B, Blatt MR (2000) Ca2+ channels at the plasma membrane of stomatal guard cells are activated by hyperpolarization and abscisic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 4967–4972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua D, Wang C, He J, Liao H, Duan Y, Zhu Z, Guo Y, Chen Z, Gong Z (2012) A plasma membrane receptor kinase, GHR1, mediates abscisic acid‐ and hydrogen peroxide‐regulated stomatal movement in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell 24: 2546–2561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh SM, Noh EK, Kim HG, Jeon BW, Bae K, Hu HC, Kwak JM, Park OK (2010) Arabidopsis annexins AnnAt1 and AnnAt4 interact with each other and regulate drought and salt stress responses. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 1499–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Ding Y, Shi Y, Zhang X, Gong Z, Yang S (2016) The cbfs triple mutants reveal the essential functions of CBFs in cold acclimation and allow the definition of CBF regulons in Arabidopsis . New Phytol 212: 345–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang ZH, Zhou XP, Tao M, Yuan F, Liu LL, Wu FH, Wu XM, Xiang Y, Niu Y, Liu F et al (2019) Plant cell‐surface GIPC sphingolipids sense salt to trigger Ca2+ influx. Nature 572: 341–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidokoro S, Yoneda K, Takasaki H, Takahashi F, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi‐Shinozaki K (2017) Different cold‐signaling pathways function in the responses to rapid and gradual decreases in temperature. Plant Cell 29: 760–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KN, Cheong YH, Grant JJ, Pandey GK, Luan S (2003) CIPK3, a calcium sensor‐associated protein kinase that regulates abscisic acid and cold signal transduction in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell 15: 411–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Park S, Gilmour SJ, Thomashow MF (2013) Roles of CAMTA transcription factors and salicylic acid in configuring the low‐temperature transcriptome and freezing tolerance of Arabidopsis . Plant J 75: 364–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight MR, Campbell AK, Smith SM, Trewavas AJ (1991) Transgenic plant aequorin reports the effects of touch and cold‐shock and elicitors on cytoplasmic calcium. Nature 352: 524–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight H, Trewavas AJ, Knight MR (1996) Cold calcium signaling in Arabidopsis involves two cellular pools and a change in calcium signature after acclimation. Plant Cell 8: 489–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight MR (2002) Signal transduction leading to low‐temperature tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana . Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 357: 871–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopka‐Postupolska D, Clark G, Hofmann A (2011) Structure, function and membrane interactions of plant annexins: an update. Plant Sci 181: 230–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudla J, Becker D, Grill E, Hedrich R, Hippler M, Kummer U, Parniske M, Romeis T, Schumacher K (2018) Advances and current challenges in calcium signaling. New Phytol 218: 414–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laohavisit A, Mortimer JC, Demidchik V, Coxon KM, Stancombe MA, Macpherson N, Brownlee C, Hofmann A, Webb AAR, Miedema H et al (2009) Zea mays annexins modulate cytosolic free Ca2+ and generate a Ca2+‐permeable conductance. Plant Cell 21: 479–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laohavisit A, Davies JM (2011) Annexins. New Phytol 189: 40–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laohavisit A, Shang ZL, Rubio L, Cuin TA, Very AA, Wang AH, Mortimer JC, Macpherson N, Coxon KM, Battey NH et al (2012) Arabidopsis annexin1 mediates the radical‐activated plasma membrane Ca2+‐ and K+‐permeable conductance in root cells. Plant Cell 24: 1522–1533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Lee EJ, Yang EJ, Lee JE, Park AR, Song WH, Park OK (2004) Proteomic identification of annexins, calcium‐dependent membrane binding proteins that mediate osmotic stress and abscisic acid signal transduction in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell 16: 1378–1391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SC, Lan WZ, Buchanan BB, Luan S (2009) A protein kinase‐phosphatase pair interacts with an ion channel to regulate ABA signaling in plant guard cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 21419–21424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao CC, Zheng Y, Guo Y (2017) MYB30 transcription factor regulates oxidative and heat stress responses through ANNEXIN‐mediated cytosolic calcium signaling in Arabidopsis . New Phytol 216: 163–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Li Y, Zhang Z, Liu X, Hsu CC, Du Y, Sang T, Zhu C, Wang Y, Satheesh V et al (2020) A RAF‐SnRK2 kinase cascade mediates early osmotic stress signaling in higher plants. Nat Commun 11: 613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Kasuga M, Sakuma Y, Abe H, Miura S, Yamaguchi‐Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K (1998) Two transcription factors, DREB1 and DREB2, with an EREBP/AP2 DNA binding domain separate two cellular signal transduction pathways in drought‐ and low‐temperature‐responsive gene expression, respectively, in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell 10: 1391–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HT, Gao F, Li GL, Han JL, Liu DL, Sun DY, Zhou RG (2008) The calmodulin‐binding protein kinase 3 is part of heat‐shock signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant J 55: 760–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Jia Y, Ding Y, Shi Y, Li Z, Guo Y, Gong Z, Yang S (2017) Plasma membrane CRPK1‐mediated phosphorylation of 14‐3‐3 proteins induces their nuclear import to fine‐tune CBF signaling during cold response. Mol Cell 66: 117–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Shi Y, Yang S (2018a) Insights into the regulation of CBF cold signaling in plants. J Integr Plant Biol 9: 780–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Xu C, Zhu Y, Zhang L, Chen T, Zhou F, Chen H, Lin Y (2018b) The calcium‐dependent kinase OsCPK24 functions in cold stress responses in rice. J Integr Plant Biol 60: 173–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Szostkiewicz I, Korte A, Moes D, Yang Y, Christmann A, Grill E (2009) Regulators of PP2C phosphatase activity function as abscisic acid sensors. Science 324: 1064–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Dai XY, Xu YY, Luo W, Zheng XM, Zeng DL, Pan YJ, Lin XL, Liu HH, Zhang DJ et al (2015) COLD1 confers chilling tolerance in rice. Cell 160: 1209–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Ye JM, Yang YQ, Lin HX, Yue LL, Luo J, Long Y, Fu HQ, Liu XN, Zhang YL et al (2019) The SOS2‐SCaBP8 complex generates and fine‐tunes an AtANN4‐dependent calcium signature under salt stress. Dev Cell 48: 697–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan RO, Martin‐Almedina S, Garcia M, Jhoncon‐Kooyip J, Fernandez MP (2006) Deciphering function and mechanism of calcium‐binding proteins from their evolutionary imprints. Biochim Biophys Acta 1763: 1238–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Renhu N, Naito M, Nakamura A, Shiba H, Yamamoto T, Suzaki T, Iida H, Miura K (2018) Ca2+‐permeable mechanosensitive channels MCA1 and MCA2 mediate cold‐induced cytosolic Ca2+ increase and cold tolerance in Arabidopsis . Sci Rep 8: 550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustilli AC, Merlot S, Vavasseur A, Fenzi F, Giraudat J (2002) Arabidopsis OST1 protein kinase mediates the regulation of stomatal aperture by abscisic acid and acts upstream of reactive oxygen species production. Plant Cell 14: 3089–3099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Fung P, Nishimura N, Jensen DR, Fujii H, Zhao Y, Lumba S, Santiago J, Rodrigues A, Chow TF et al (2009) Abscisic acid inhibits type 2C protein phosphatases via the PYR/PYL family of START proteins. Science 324: 1068–1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei ZM, Murata Y, Benning G, Thomine S, Klusener B, Allen GJ, Grill E, Schroeder JI (2000) Calcium channels activated by hydrogen peroxide mediate abscisic acid signalling in guard cells. Nature 406: 731–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao B, Zhang Q, Liu DL, Wang HQ, Yin JY, Wang R, He ML, Cui M, Shang ZL, Wang DK et al (2015) A calcium‐binding protein, rice annexin OsANN1, enhances heat stress tolerance by modulating the production of H2O2 . J Exp Bot 66: 5853–5866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy ASN, Ali GS, Celesnik H, Day IS (2011) Coping with stresses: roles of calcium‐ and calcium/calmodulin‐regulated gene expression. Plant Cell 23: 2010–2032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renaut J, Hausman JF, Wisniewski ME (2006) Proteomics and low‐temperature studies: bridging the gap between gene expression and metabolism. Physiol Plant 126: 97–109 [Google Scholar]

- Rentel MC, Knight MR (2004) Oxidative stress‐induced calcium signaling in Arabidopsis . Plant Physiol 135: 1471–1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards SL, Laohavisit A, Mortimer JC, Shabala L, Swarbreck SM, Shabala S, Davies JM (2014) Annexin 1 regulates the H2O2‐induced calcium signature in Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Plant J 77: 136–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]