Abstract

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are chronic diseases that are by far the leading cause of death in the world. Many occupational hazards, together with social, economic and demographic factors, have been associated to NCDs development. Genetic susceptibility or environmental exposures alone are not usually sufficient to explain the pathogenesis of NCDs, but can be integrated in a more complex scenario that can result in pathological phenotypes. Epigenetics is a crucial component of this scenario, as its changes are related to specific exposures, therefore potentially able to display the effects of environment on the genome, filling the gap between genetic asset and environment in explaining disease development. To date, the most promising biomarkers have been assessed in occupational cohorts as well as in case/control studies and include DNA methylation, histone modifications, microRNA expression, extracellular vesicles, telomere length, and mitochondrial alterations.

Key words: Epigenetics, occupational exposures, non-communicable diseases

Abstract

«Esposizione occupazionale e rischio di sviluppare malattie croniche non trasmissibili: il ruolo dei marcatori molecolari ed epigenetici». Le malattie croniche non trasmissibili (MCNT) sono la principale causa di morte nel mondo e molti rischi professionali, fattori sociali, economici e demografici, sono stati associati al loro sviluppo. In genere, l’ereditarietà genetica e le diverse esposizioni ambientali, se considerate singolarmente, non sono sufficienti a spiegare la patogenesi delle MCNT. Occorre integrare questi fattori in uno scenario più complesso per poter comprendere quale sia il loro contributo nell’insorgenza delle malattie. L’epigenetica è una componente cruciale di questo scenario poiché le modificazioni epigenetiche sono legate a esposizioni specifiche e quindi potenzialmente in grado di rappresentare gli effetti dell’ambiente sul genoma, colmando così il divario tra l’assetto genetico e le esposizioni ambientali e permettendo di chiarire i meccanismi molecolari implicati nello sviluppo delle malattie. Attualmente i biomarcatori più promettenti, quali metilazione del DNA, le modificazioni degli istoni, l’espressione di microRNA, le vescicole extracellulari, la lunghezza telomerica e le alterazioni mitocondriali, sono stati valutati in ambito occupazionale mediante studi epidemiologici di coorte e caso/controllo. (il testo in italiano dell’articolo è a pag. 184).

Occupational and lifestyle factors role in non-communicable disease development

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are chronic diseases that are by far the leading cause of death in the world, representing 71% of all annual deaths (WHO, 2018; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases). The four main types of NCDs are cardiovascular diseases (like heart attacks and stroke), cancer, chronic respiratory diseases (such as chronic obstructed pulmonary disease and asthma) and diabetes. The risk of NCDs is increased by modifiable behaviors, such as tobacco use, physical inactivity, and unhealthy diet. Many occupational hazards, together with social, economic and demographic factors, have also been associated to NCDs development, in particular with chronic respiratory diseases and cardiovascular diseases. Moreover, high levels of occupational stress, isolated living conditions, worksite food catering services, nocturnal work shifts and other related factors have been shown to affect NCD development (13).

Same exposure, different risk: theimportance of detecting the hypersusceptible subjects

Occupational risks have been identified by observations of increased morbidity or mortality among specific populations of workers. Hypersusceptibility is defined as a condition characterized by a set of risk factors that make some people more susceptible than others to certain exposures (37, 72, 107). Risk factors include distinct categories, as genetic asset and lifestyle/occupational factors. Genetic susceptibility variants are inherited traits at the bases of biological variability, and contribute to determine the individual molecular response to environmental insults. Lifestyle/occupational factors include all non-genetic forces experienced during life, such as nutritional status, drug use, socioeconomic status, behavioral traits, occupational and environmental exposures (37, 107). Both these components are crucial in the onset of several diseases, such as NCDs, which are often associated with older age groups, although evidences show that 15 million of all deaths attributed to NCDs occur between the ages of 30 and 69 years. Of these “early” deaths, over 85% are estimated to occur in low- and middle-income countries, where several environmental exposures reach high levels and occupational conditions are often life threatening.

As an example, to investigate a population of workers, we cannot avoid considering concurrent risk factors that are well represented in the general population, such as obesity. Obesity is a condition of increased chronic low-grade inflammation, which results in an increased susceptibility to cardiovascular risk associated with particulate exposure. For this reason, the inclusion of several hypersusceptibility factors must be taken into account to obtain a comprehensive understanding of individual risk of developing NCDs.

Epigenetics at the crossroads between genetics, environmental exposures and disease

Genetic susceptibility or environmental exposures alone are not usually sufficient to explain the pathogenesis of NCDs, but should be integrated in a more complex scenario that can result in pathological phenotypes. Epigenetics is a crucial component of this scenario, as its changes are related to specific exposures, therefore potentially able to display the effects of environment on the genome, filling the gap between genetic asset and environment, in explaining disease development. As the epigenome is a plastic entity modified by the environment and some modifications are detectable in accessible tissues (e.g. peripheral blood, urine, buccal cells, etc.) and show long-term stability, epigenetic pattern might be considered as a memory of occupational/environmental exposures experienced throughout life (57, 77).

In this last decade, the Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS) have clearly established that high-penetrance disease-associated genetic variants cause defined functional consequences (e.g. nonsynonymous amino acid changes or truncated proteins). On the other hand, a large portion of low-penetrance variants are difficult to interpret, as they do not cause downstream functional changes able to determine per se a pathogenic effect. Epigenetics might offer an opportunity to disentangle how these variants impact the effects of occupational/environmental exposures, clarifying their role as risk factors in NCD onset (58). The effects of a particular genetic variant can be modulated by epigenetic modifications, associated for instance with occupational/environmental exposures, able to limit the expression of the corresponding allele (111, 114).

Altered epigenetic states have been shown to be associated with a wide range of NCDs including cancer (94, 112, 119), cardiovascular diseases (1), neurodegeneration and aging (44, 71, 103), psychiatric (75, 104, 120) and autoimmune diseases (30, 68, 74), all of which are known to be influenced also by occupational/environmental exposures (57).

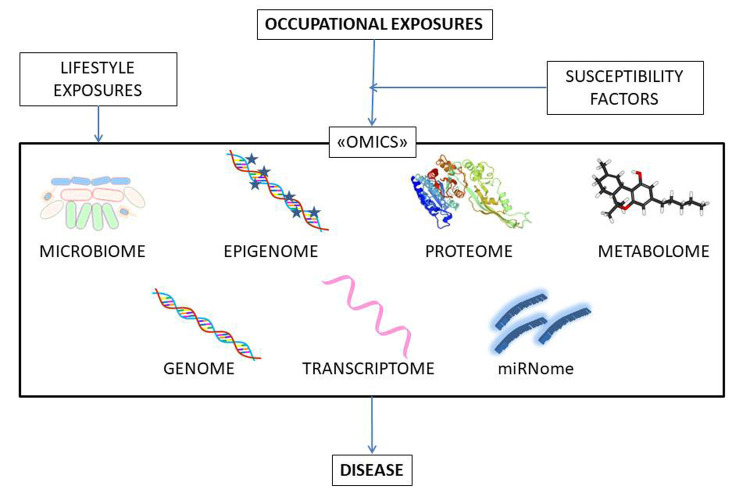

Besides epigenomics, “Omics” includes genomics, transcriptomics, miRNomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and microbiomics (figure 1). The emerging field of omics – i.e. large-scale data-rich biological measurements- provides new opportunities to advance our knowledge in the field. A deep analysis of this topic goes beyond the purpose of the present review, but a useful introduction can be found in the review by Karczewski and Snyder (53).

Figure 1.

The emerging field of “omics” includes a variety of large-scale data-rich biological measurements and provides new opportunities to better understand how occupational exposure, lifestyle factors and susceptibility factors can modulate disease risk

Novel biomarkers

While genetic mutations are relatively rare events and, once acquired, cannot be reverted, epigenetic changes are dynamic and can allow the cells to adapt their functioning in response to every stimulus. At the same time, as epigenetic profiles can reflect several diseases, they can help to explain the molecular mechanisms underlying the disease risks, and can also be considered as suitable clinical biomarkers (both diagnostic and prognostic) of several NCDs, among which the most consolidated is cancer (39, 78).

In order to be able to detect the epigenetic changes induced by the external environment, high sensitive and specific biomarkers are needed. Moreover, the ideal biomarker should be easy to measure, not only in a research laboratory setting.

DNA methylation, histone modifications, microRNA expression, extracellular vesicles, telomere length, and mitochondrial alterations are promising biomarkers to be used in occupational settings.

DNA methylation

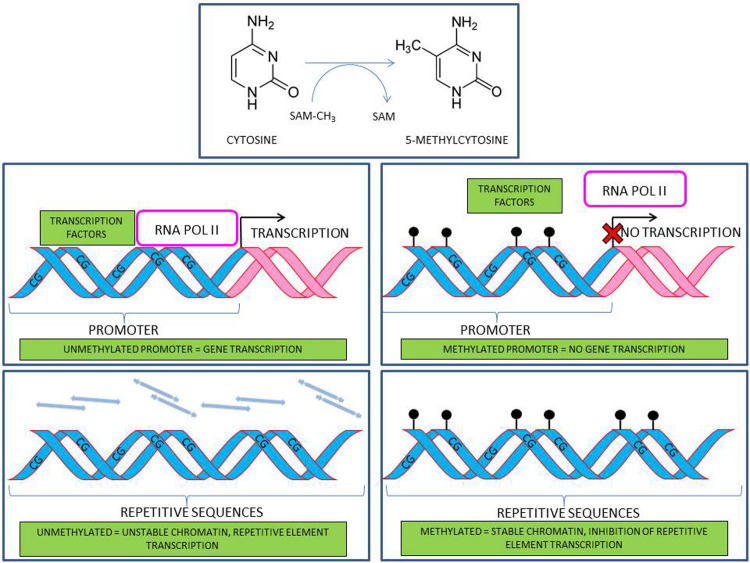

DNA methylation represents the best-characterized epigenetic modification. It implies the addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of the cytosine DNA base, giving rise to a 5-methyl-cytosine (figure 2). In differentiated cells, only cytosine followed by a guanine can be efficiently methylated by specific enzymes, called DNA methyltransferase. All the known DNA methyltransferases use S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) as the methyl donor (76). Patterns of DNA methylation are established early during development, with two critical waves of methylation and demethylation occurring during embryogenesis. On the one hand, when DNA methylation pattern is established (in utero), it is then maintained into subsequent cellular generations, being a mechanism through which each cell lineage becomes highly specialized. On the other hand, any stimulus reaching a particular cell through life is potentially able to modulate its DNA methylation (3).

Figure 2.

DNA methylation implies the addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of the cytosine DNA base, giving rise to a 5-methyl-cytosine. In differentiated cells, only cytosine followed by a guanine can be efficiently methylated by specific enzymes, called DNA methyltransferase. All the known DNA methyltransferases use S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) as the methyl donor. DNA methylation occurring in gene promoters can directly alter gene expression, by inhibiting the access to DNA of the transcriptional machinery function. This methylation is often referred as “gene-specific methylation”. Methylation taking place in repetitive transposable elements (e.g. Alu, LINE-1, HERVs, etc.) can compact the chromatin structure and therefore increase DNA resistance to toxicants

DNA methylation occurring in gene promoters can directly alter gene expression, by inhibiting the access to DNA of the transcriptional machinery function. This methylation is often referred as “gene-specific methylation” (79). Methylation taking place in repetitive transposable elements (e.g. Alu, LINE-1, HERVs, etc.) has a different function, as it can compact the chromatin structure and therefore increase DNA resistance to toxicants (116).

DNA methylation is the first player that allows the body to shape gene expression in response to environmental stimuli. This first adaptive reaction might later evolve in a stable change potentially contributing to the development of disease.

One of the most fascinating open points on DNA methylation is the possibility for transgenerational inheritance of methylation changes, implying both an impact on the offspring through direct effects of exposure of the gametes or embryos, or rather a true transgenerational effect on subsequent generations that did not directly experience the exposure.

Bisulfite treatment is the method of choice for the analysis of DNA methylation in complex genomes as it is a simple method to convert an epigenetic mark into a genetic difference, which can be further analyzed by standard molecular biology techniques, such as pyrosequencing. Several additional methods have been developed in the last few years for DNA methylation analysis, however bisulfite treatment and pyrosequencing remain the gold standard to evaluate the effects of environmental exposure, due to its sensitivity that allows the detection even of very slight modifications (14).

Several types of exposures experienced during occupational life have been shown to modulate both global and gene-specific DNA methylation.

An increased global methylation was reported in coal workers and in hairdresser exposed to formaldehyde (10, 28). A reduced global methylation was reported for workers in petro-chemical factories, and workers exposed to low-dose benzene, such as petrol-station workers (16, 34, 95, 102). Global methylation studies conducted on farmers exposed to different pesticides were not conclusive. Most of the studies reported a decrease of global methylation, while Benedetti and colleagues recently reported genomic hypermethylation in soybean farmers exposed to complex mixture of pesticides (12, 27, 51, 52, 97).

To evaluate the effects of occupational exposure, methylation levels have also been measured on promoters of several genes, mainly involved in cancer risk, and epigenetic alterations may be early indicators of genotoxic and non-genotoxic carcinogen exposure (99).

In hairdressers, gene specific methylation analysis of selected cancer-related genes allowed the identification of higher methylation of the CDKN2A gene, a master regulator of cell cycle (66). Increased methylation levels of CDKN2A were also reported in nurses and midwives (19), together with BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumor-suppressor genes (88). Increased methylation levels of tumor-suppressor genes were also confirmed in lead-exposed workers (125).

Low-dose benzene exposure was associated with aberrant promoter methylation of genes involved in the inflammation process, in nitrosative stress and in xenobiotic metabolism (50). In petrochemical workers, the tumor-suppressor p15 altered expression was reported (16, 102), and cancer-related NRF2 and KEAP1 genes altered promoter methylation was reported in men occupationally exposed to arsenic (47). DNA methylation of the cancer-related genes F2RL3 and AHRR was associated with occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) (4). Occupational exposure to vinyl chloride monomer (VCM)-occupational exposure was associated with altered methylation of tumor-suppressor p16 (117), and cancer-related MGMT and MLH1 genes (122).

Exposure to pesticides was associated with several altered gene specific-methylation levels: p16 (52); CDH1, GSTp1, and MGMT (97); BRCA1, and genes involved in p70S6K signaling, and PI3K signaling in B lymphocytes (33, 42).

Methylation levels of NOS3 and EDN1 genes, involved in coagulation, were altered in steel workers (108).

Goodrich and colleagues reported that dental workers exposure to mercury (Hg) was associated with reduced methylation of SEPP1 gene, which is involved in the counterbalance of Hg toxic effects in buccal epithelium (38).

Interestingly, long-term exposure to shift work in cohorts of nurses and midwives, was associated with altered methylation of CLOCK genes, which are involved in the control of circadian rhythm and whose alterations have been linked to increased cancer risk (18, 93).

The increasing experimental and epidemiological studies of DNA methylation changes caused by occupational exposures suggest that both global and gene specific methylation are strongly impacted, and that epigenetic marks may have the potential to be future biomarkers for occupational risk assessment.

Histone modifications

Each human cell contains approximately 2 meters of DNA, while the average nucleus is 0.006 mm in diameter. This simple observation underlines two opposing requirements: DNA needs to be compacted, but on the other hand it needs to maintain accessibility in order to be transcribed, replicated, and repaired.

Human DNA is therefore compacted by being wound around octamers of core histone proteins that form nucleosomes. Nucleosomes comprise 147 base pairs of DNA wrapped approximately twice around the protein core that contains two copies of each histone, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 (69). The interaction between DNA and histones is critical to regulating transcription, replication, and repair of the genome and is regulated by more than 100 distinct histone modifications, such as phosphorylation, methylation, ubiquitination, and acetylation (127). Histone code hypothesis states that gene regulation is partly dependent on histone modifications that primarily occur on histone tails (48). These modifications modify the net charge of the core histone, modulating the affinity between the DNA (negatively charged) and the octamer: adding positive charges would result in a closure of the nucleosome, while adding negative charges would result in an opening of the nucleosome (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Human DNA is compacted by being wound around octamers of core histone proteins that form nucleosomes. Nucleosomes comprise 147 base pairs of DNA wrapped approximately twice around the protein core that contains two copies of each histone, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. The interaction between DNA and histones is critical to regulating transcription, replication, and repair of the genome and is regulated by more than 100 distinct histone modifications, such as phosphorylation, methylation, ubiquitination, and acetylation. Histone code hypothesis states that gene regulation is partly dependent on histone modifications that primarily occur on histone tails. These modifications modify the net charge of the core histone, modulating the affinity between the DNA (negatively charged) and the octamer: adding positive charges would result in a closure of the nucleosome, while adding negative charges would result in an opening of the nucleosome

Histone acetylation/deacetylation, probably the most investigated modification, is conducted by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs). For example, histone acetylation is associated with transcriptionally active genes, while deacetylation is associated with inactive genes.

Several environmental conditions (e.g. metals, air pollutants, dietary conditions) can induce histone modifications, possibly altering both specific gene expression and global chromatin conformation (7, 20, 56, 106). Interestingly, the influences of these toxicants can endure even after the toxicant is no longer present.

The standard method for histone modification analysis is the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). However, many efforts have been made in order to develop high-throughput methods by combining chromatine immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and DNA-microarray analysis (chip) techniques, abbreviated as “ChIP-on-chip” (65, 91, 96).

Histone 3 lysine 4 dimethylation (H3K4me2) and histone 3 lysine 9 acetylation (H3K9ac) are two histone modifications associated with open chromatin states and considered as main markers of exposures (9). H3K4me2 and H3K9ac were associated with several occupational exposures, including different metals such as nickel, arsenic, and iron, and with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) and benzene (7, 20, 21, 55, 64, 70, 126). While DNA methylation seems to be modified in a few days, histone modifications are probably a suitable epigenetic biomarker induced by long-term exposures. However, as the comprehensive analysis of histone modifications is almost impossible to be obtained, and even specific modification analyses are quite time consuming, histone modifications are still largely unexplored in large epidemiological cohorts.

microRNA expression

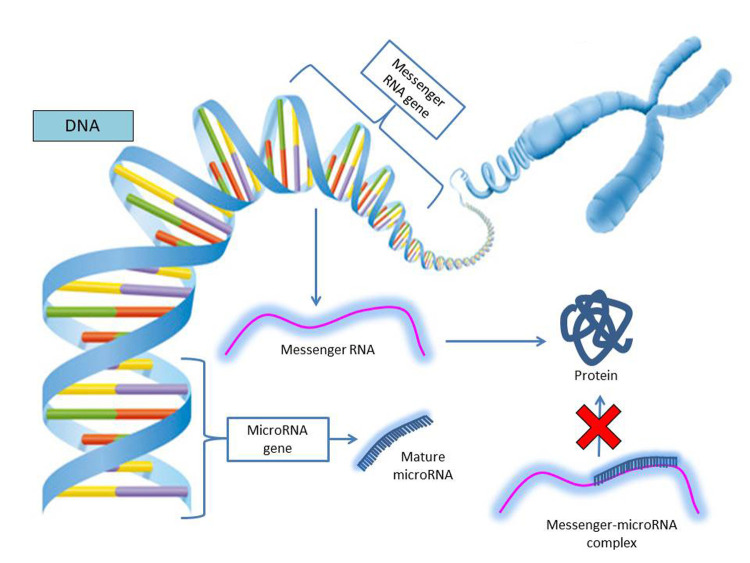

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short RNAs of approximately 22 nucleotides in length. miRNAs post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression by silencing protein expression through cleavage and degradation of the mRNA transcript or inhibiting translation (23) (figure 4). A single miRNA can bind multiple mRNA targets (more than 100), while several miRNAs may regulate a single mRNA target (35).

Figure 4.

MicroRNAs are short RNAs of approximately 22 nucleotides in length. miRNAs post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression by silencing protein expression through cleavage and degradation of the mRNA transcript or inhibiting translation. A single miRNA can bind multiple mRNA targets (more than 100), while several miRNAs may regulate a single mRNA target

The relative expression of miRNAs can be studied by various techniques, such as hybridisation-based methods (e.g. microarrays) used as an initial approach to find the potential candidate miRNAs, or quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) used to validate highly dysregulated miRNAs. qPCR, due to its high precision and accuracy, remains the gold standard for miRNA quantification. In addition, miRNAs can be sequenced and quantified by using next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms (2).

Thanks to their stability, miRNAs have been extensively investigated in peripheral blood and urine as potential biomarkers of exposure. Lower expression of miR-24-3p, miR-27a-3p, miR-142-5p, and miR-28-5p in blood was associated with urinary monohydroxy-PAHs and plasma benzo[a]pyrene-r-7,t-8,c-10-tetrahydrotetrol-albumin (BPDE–Alb) adducts in coke oven workers (29). miR-6819-5p and miR-6778-5p were observed to be upregulated in blood in workers exposed to organic solvents, such as ethylbenzene, toluene, and xylene, while the up-regulation of miR-92a and miR-486 was reported in plasma samples in association with chronic mercury occupational exposure (31, 105). Decreased expression of miR-548h-5p, miR-145-5p, miR-4516, miR-331-3p, miR-181a-5p, and miR-1260a, all involved in tumor suppressor activity, was observed in incumbent firefighters while the expression of miR- 374a-5p and miR-486-3p, involved in cancer survival, was increased (49).

miRNA levels were evaluated also as biomarkers of pesticide exposure in urine. Interestingly, miR-223, -518d-3p, -597, -517b, -133b, and -28-5p were observed to be positively associated with farmworkers status during the post-harvest season, and a positive dose response relationship with organophosphate pesticide metabolites was reported by Weldon and colleagues (118).

Although miRNAs have the potential of being sensitive biomarkers of different occupational exposures, further studies in larger populations are needed to empower the associations identified between biomarkers and exposures.

Extracellular vesicles

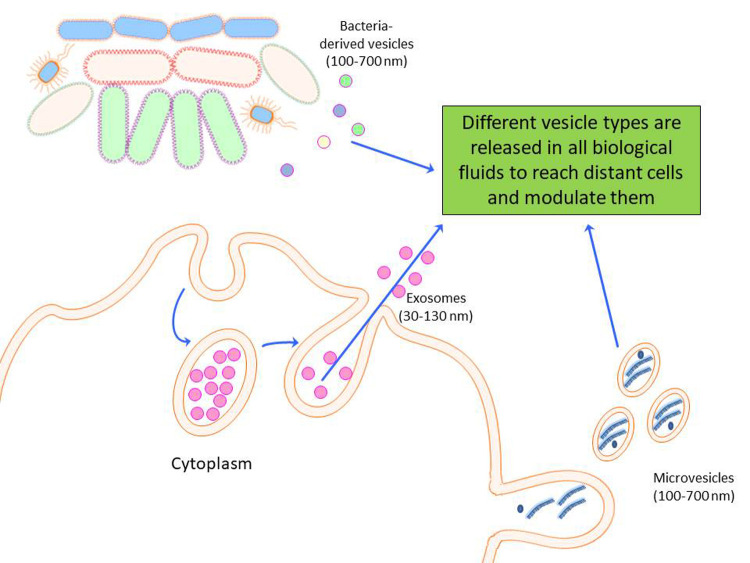

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are a heterogeneous group of membrane vesicles, which are released from cells under both physiological and pathological conditions (124). EVs play a central role in cell-to-cell communication, as they are able to transfer between cells biological active molecules, such as proteins and nucleic acids (113). Of particular interest is the fact that EVs contain microRNAs, thus being potentially able to modulate cell expression “at a distance” (124). As EVs can transmit information from one cell to another, they represent a potential mechanism to help explaining how several environmental exposures interact with the molecular machinery of the body (figure 5). EVs have been detected in most body fluids, including blood, urine, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, amniotic fluid, seminal plasma, and breast milk.

Figure 5.

Extracellular vesicles are a heterogeneous group of membrane vesicles, including microvesicles and exosomes, which are released from cells under both physiological and pathological conditions. Extracellular vesicles play a central role in cell-to-cell communication, as they are able to transfer between cells biological active molecules, such as proteins and nucleic acids. Extracellular vesicles contain microRNAs, being able to modulate cell expression “at a distance”, and they have been detected in most body fluids, including blood, urine, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, amniotic fluid, seminal plasma, and breast milk

The study of EVs is quite a new research field, and the standardization of methods for their isolation and characterization is still debated. The current guidelines for EVs processing are reported in the Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018) (109).

In a recent work, we isolated plasma EVs from fifty-five healthy male workers employed for at least 1 year in a steel production plant, before and after workplace PM exposure, and evaluated the expression of 88 EV-associated miRNAs by quantitative qPCR. miR-128 and miR-302c expression was increased after 3 days of workplace PM exposure. Moreover, in vitro experiments conducted on the A549 alveolar epithelium derived-cell line confirmed a dose-dependent expression of miR-128 in EVs released after 6 h of PM treatment. These findings suggest that PM exposure induces the release of specific miRNAs within EVs generated from alveolar or other lung cells, which can be detected in plasma (17). Moreover, in the same cohort, the increased expression of 17 EV-associated miRNAs was associated with individual level of PM and metal exposure, suggesting the involvement of different molecular mechanisms such as insulin biosynthesis, inflammation and coagulation in response to those specific exposures (82).

Telomere length

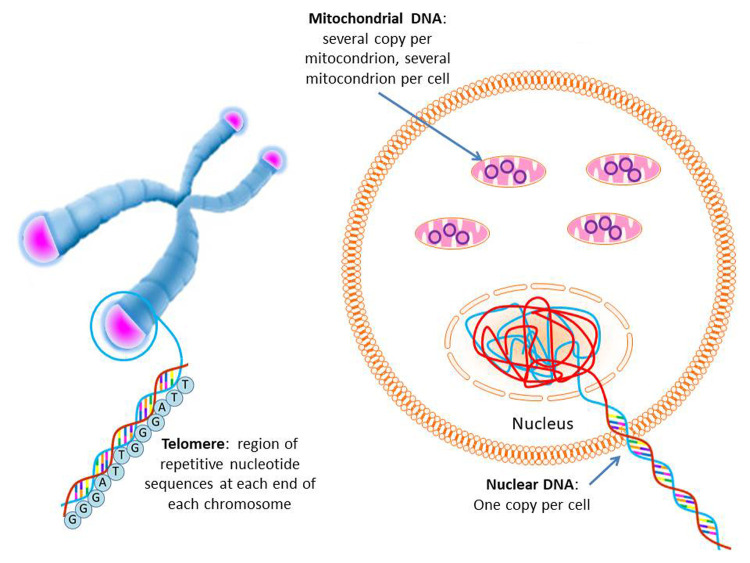

All the cells have a biological clock in telomeres, which are DNA sequences located at the ends of chromosomes (figure 6) involved in maintaining genomic stability and regulating cellular proliferation (67). Telomeres are DNA repeat sequences (TTAGGG) that, together with associated proteins, form a sheltering complex that caps chromosomal ends and protects their integrity (25). Chromosomal stability is gradually lost as telomeres shorten with each round of cell division. Telomere length can be measured in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Leukocyte Telomere Length, LTL) as marker of biological aging (73). In fact, in proliferating tissues, LTL is longer at birth and shortens progressively as individuals’ age (25).

Figure 6.

Telomeres are DNA repeat sequences (TTAGGG) that, together with associated proteins, form a sheltering complex that caps chromosomal ends and protects their integrity. Chromosomal stability is gradually lost as telomeres shorten with each round of cell division. Telomere length can be measured in leukocytes as marker of biological aging. In proliferating tissues, leukocyte telomere length is generally longer at birth and shortens progressively as individuals’ age. Most of the mammalian cells contain hundreds to more than a thousand mitochondria each. The mitochondrion works as a factory for ATP (adenosine triphosphate) and metabolite supplies for cell survival and releases cytochrome c to initiate cell death. Each organelle harbors 2–10 copies of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). mtDNA is known to be more sensitive to oxidative damage than nuclear DNA due to its lack of protective histones, introns, and an efficient DNA repair mechanisms. mtDNA copy number may serve as a promising biomarker for oxidative stress–related health outcomes

Retrospective and prospective epidemiological studies have shown that LTL shortening is a risk factor for age-related NCDs (40, 83, 85). Oxidative stress and inflammation, the two major intermediate mechanisms for such diseases, are also risk factors for LTL shortening (84, 86). Telomere erosion can however be further accelerated by external stressors. Telomeres, in fact, as triple-guanine-containing sequences, are highly sensitive to physical and chemical genotoxic exposures. Occupational exposure to genotoxic compounds, directly, by damaging DNA, and indirectly, by favoring the cumulative effect of oxidative damages and the onset of chronic inflammation, might accelerate the physiological process of telomere erosion and facilitate the onset of NCDs (15).

LTL are measured by using qPCR methods described by Cawthon (24). This assay measures relative LTL i.e., T/S ratio, by determining the ratio of telomere repeat copy number (T) to single nuclear copy gene (S), in a given sample relative to that of a reference DNA. The single-copy gene used in this study is usually human ß-globin (HBB). This technique can be applied to a high-throughput format and therefore this method is widely used in large population studies (46).

Our research groups published the first evidences of LTL shortening in association with occupational exposures: LTL decreased in traffic workers exposed to benzene (43) and in coke-oven workers exposed to high levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (80). After this initial observation, Fu and coworkers confirmed LTL reduction in Chinese coke-oven workers, longitudinally studied (36). Exposure to high levels of vinyl chloride monomer was also associated with LTL shortening (128, 129), as well as N-nitrosamines in rubber industries and polychlorinated biphenyls exposure in a transformer cycling company (62, 130). In hairdressers, aromatic amine exposure, evaluated by hemoglobin adducts, reduced LTL (66). Studies evaluating particle matter (PM)-related exposures at work coherently report modifications of LTL in association with long-term exposure (43, 63, 121). LTL reduction was reported also in smelters exposed to Pb (87).

Several studies associate exposure to pesticides to LTL but the results are not conclusive. A decrease of LTL in blood was found in different type of exposures (51, 52, 98). Similar results were reported also for TL measured in DNA from saliva (41). On the other hand, increased LTL was also reported in association with exposure to different pesticides (6, 32, 115).

The association of LTL with exposure to ionizing radiations presents contrasting results. Shorter LTL was found in Chernobyl nuclear power plant (CNPP) clean-up workers exposed to low levels of radiation (45). On the contrary, longer telomere were found in Chernobyl CNPP clean-up workers who worked during 1986, in those undertaking ‘dirty’ tasks (digging and deactivation) (92) and in workers of a plutonium production plant (100). Authors suggest that longer telomeres, revealed in people more heavily exposed to ionizing radiation probably indicate a later activation of telomerase as a chromosome healing mechanism following damage, and reflect defects in telomerase regulation that could potentiate carcinogenesis. LTL shortening was reported also in workers cardiac catheterization laboratory staff exposed to long-term low-dose ionizing radiation (5).

Telomere length may be an underlying mechanism by which a wide range of occupational exposures may influence ageing and may relate to an early risk of NCD development and mortality.

Mitochondrial DNA copy number

Most of the mammalian cells contain hundreds to more than a thousand mitochondria each. A mitochondrion is an essential organelle of eukaryotic cells, with many functions that ensure differentiation, survival and control of cell death (59). The mitochondrion works as a factory for ATP (adenosine triphosphate) and metabolite supplies for cell survival and releases cytochrome c to initiate cell death. Each organelle harbors 2–10 copies of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). mtDNA is known to be more sensitive to oxidative damage than nuclear DNA due to its lack of protective histones, introns, and an efficient DNA repair mechanisms (90). Increased oxidative stress may contribute to alterations in the copy number mtDNAcn and integrity of mtDNA in human cells (60, 61). Epidemiologic studies have linked reduced leukocyte mtDNA copy number (mtDNAcn) with a range of adverse clinical outcomes, including all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease and sudden cardiac death, metabolic syndrome, and chronic kidney disease (8, 26, 110). Therefore, mtDNAcn may serve as a promising biomarker for oxidative stress–related health outcomes. Progressive loss of mitochondrial function is a common feature of ageing being influenced by the life-long production of ROS, as by-products of oxidative metabolism (11, 54).

mtDNAcn is measured using a qPCR method similar to the one used for TL analysis. The assay measures relative mtDNAcn by determining the ratio of mitochondrial (MT) DNA copy number to single copy gene (S) copy number in experimental samples relative to the MT/S ratio of a reference-pooled sample (22, 81).

Since mtDNA are highly prone to damage, some studies explored the effect of occupational pollutants on it. Reports found that alteration of mtDNAcn in peripheral blood can be related to toxic exposures, such as PAHs (81, 123) and benzene (22).

It has been suggested that the oxidative stress, as a consequence of exposure to PAHs, has a dual influence on mitochondrial DNA content. Environmental low-dose exposure to PAHs can stimulate mitochondrial DNA production to fulfill the respiratory needs of the cell in order to allow the cell survival (89). On the other hand, excessive oxidative stress generated by tobacco smoke that, containing many toxic, carcinogenic and mutagenic chemicals, as well as stable and unstable free radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS), with the potential for oxidative DNA damage, might result in decreased or no synthesis of mtDNA, eventually leading to cell senescence or cell death. This hypothesis may also explain the different results obtained in terms of mtDNAcn in association with occupational exposures.

A considerable amount of research is still needed to understand the influence of the exposure to occupational toxicants on mtDNAcn.

Markers of exposure or markers of effect?

The biomarkers we have described are modified by many factors and probably every stimulus that our body receives, is later summarized as “epigenetic memory”.

For this reason, epigenetic biomarkers cannot be considered as markers of single exposures, as they are not specific for one particular occupational toxicant and are not useful to quantify the individual dose to which each worker was exposed. Nonetheless, these markers have the potential for becoming important markers of early effect, as they might assist the occupational physician in understanding who are the workers at higher risk of developing specific diseases in a given occupational setting.

The concept of precision medicine postulates that medicine should make individual prevention and treatment by taking into account each patient’s genomics, pre-existing conditions, exposures, and a variety of potential risk factors unique to that individual. Epigenetics might integrate this concept, shedding light on individual susceptibility to toxicants and giving irreplaceable tools for measuring such susceptibility in a quantitative manner. Epigenetics data would therefore potentiate several parameters such as toxicodynamics, toxicokinetics and the mechanism of action toxicants within the body, thus eventually contributing to the risk assessment processes (101).

However, these markers have not been standardized yet, so the next step in order to translate the findings from basic research to medicine will have to go in this direction.

The challenge that occupational physicians and scientists are facing in the (near) future is big, as they need to interpret these markers not only as markers of occupational risk but also, in addition, as markers of risk related to modifiable lifestyle factors. If the entire professional and scientific community of occupational medicine and health accept this challenge, this might represent a huge step forward in the comprehension of occupational risks and towards workers’ health protection and well-being promotion.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported by the authors

Esposizione occupazionale e rischio di sviluppare malattie croniche non trasmissibili: il ruolo dei marcatori molecolari ed epigenetici

Le malattie croniche non trasmissibili (MCNT) costituiscono la principale causa di morte nel mondo, rappresentando, annualmente, il 71% di tutti i decessi (WHO, 2018; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases). Le quattro tipologie principali di MCNT sono le malattie cardiovascolari (come infarto e ictus), il cancro, le malattie respiratorie croniche (come la malattia polmonare cronica ostruttiva e l’asma) e il diabete. Il rischio di sviluppare MCNT è fortemente influenzato da fattori comportamentali e stili di vita quali fumo di sigaretta, inattività fisica e abitudini dietetiche. Un ruolo rilevante hanno anche fattori di rischio occupazionale (ad esempio stress lavoro correlato e lavoro a turni) e fattori socioeconomici che sono stati associati in particolare allo sviluppo di malattie respiratorie croniche e di patologie cardiovascolari (13).

Stessa esposizione, rischio differente: l’importanza di individuare i soggetti ipersuscettibili

L’attenzione che è stata posta sul ruolo dei rischi occupazionali nell’insorgenza delle MCNT deriva dall’osservazione di un aumento sia di mortalità sia di morbidità in alcune specifiche categorie di lavoratori. L’ipersuscettibilità è definita come una condizione caratterizzata dalla commistione di diversi fattori di rischio che rendono alcuni soggetti più suscettibili di altri agli effetti di determinate esposizioni (37, 72, 107). I fattori di rischio coinvolti includono differenti sottocategorie, come l’assetto genetico e i fattori occupazionali o lo stile di vita. Le varianti di suscettibilità genetica sono varianti ereditarie che stanno alla base della variabilità biologica e che contribuiscono a determinare la risposta molecolare di ciascun individuo agli insulti ambientali. I fattori occupazionali e lo stile di vita includono tutte quelle componenti non genetiche che costituiscono la vita di ciascun individuo, come la dieta, l’uso di droghe, lo stato socioeconomico, i tratti comportamentali e le esposizioni occupazionali e ambientali (37, 107). Entrambe queste componenti sono cruciali nel determinare l’insorgenza di diverse patologie, come le MCNT, che sono spesso associate all’avanzare dell’età, sebbene ci siano evidenze che mostrano come 15 milioni di morti attribuibili alle MCNT si verifichino tra i 30 e i 65 anni di età. Di queste morti “precoci”, si stima che più dell’85% si verifichino nei paesi a basso e medio reddito, nei quali le esposizioni ambientali raggiungono livelli elevati e le condizioni lavorative sono spesso fonte di innumerevoli rischi per l’individuo.

Per studiare una popolazione di lavoratori, non possiamo non tenere in considerazione anche altri fattori di rischio che sono ben rappresentati all’interno della popolazione generale. Un esempio è l’obesità, una condizione caratterizzata da un aumentato livello di infiammazione cronica sistemica, che sfocia in un’aumentata suscettibilità al rischio cardiovascolare associato all’esposizione al particolato atmosferico (Particulate Matter, PM). Per questa ragione, al fine di avere un quadro completo e dettagliato del rischio individuale di sviluppare MCNT, è fondamentale prendere in considerazione diversi fattori di ipersuscettibilità.

L’epigenetica al crocevia tra genetica, esposizioni ambientali e malattie

La suscettibilità genetica o le esposizioni ambientali da sole non sono solitamente sufficienti a spiegare la patogenesi delle MCNT, ma devono essere integrate in uno scenario più complesso che può portare ad una maggiore comprensione dei fenotipi patologici. L’epigenetica è una componente cruciale di questo scenario, dal momento che le modificazioni epigenetiche sono correlate a esposizioni specifiche e quindi potenzialmente in grado di spiegare gli effetti dell’ambiente sul genoma, colmando il vuoto attualmente esistente tra assetto genetico e ambiente nello sviluppo di patologie. L’epigenoma può quindi essere pensato come un’entità plastica modificata dall’ambiente. Alcune delle modificazioni epigenetiche sono identificabili in tessuti facilmente accessibili (e.g. sangue periferico, urine, cellule buccali, ecc.) e sono stabili nel tempo. Il profilo epigenetico di un soggetto può essere quindi considerato come una sorta di memoria delle esposizioni occupazionali/ambientali nel corso della vita (57, 77). Nell’ultimo decennio, i risultati ottenuti dagli studi di associazione genome-wide (Genome Wide Association Studies, GWAS) hanno permesso di stabilire che le varianti geniche ad alta penetranza associate alle patologie causano specifiche conseguenze funzionali (e.g. cambi aminoacidici non sinonimi o proteine tronche). D’altra parte, una grande fetta di varianti a bassa penetranza sono difficili da interpretare, poiché non provocano cambiamenti funzionali in grado di determinare per sé un effetto patogenetico. L’epigenetica può offrire un’opportunità per comprendere come queste varianti possano impattare gli effetti delle esposizioni occupazionali/ambientali, chiarendo così il loro ruolo come fattori di rischio delle MCNT (58). Gli effetti di una specifica variante genica possono essere modulati da modificazioni epigenetiche associate, ad esempio, a determinate esposizioni ambientali/occupazionali, e in grado quindi di regolare l’espressione dell’allele corrispondente (111, 114).

Profili epigenetici alterati sono stati associati a un ampio spettro di MCNT inclusi cancro (94, 112, 119), malattie cardiovascolari (1), malattie neurodegenerative e invecchiamento (44, 71, 103), patologie psichiatriche (75, 104, 120) e autoimmuni (30, 68, 74), che includono tra i fattori di rischio anche esposizioni occupazionali/ambientali (57).

Oltre all’epigenomica, l’“omica” include la genomica, la trascrittomica, la miRNomica, la proteomica, la metabolomica e la microbiomica (Figura 1). L’applicazione delle tecniche “omiche”, che si sta sempre più diffondendo, è un altro strumento che potrà essere utilizzato per integrare e approfondire le attuali conoscenze sulla complessità della relazione tra fattori di rischio e insorgenza di patologie. Esula dallo scopo di questo articolo una trattazione sistematica delle “omiche” che si può trovare in Karczewski e Snyder (53) e a cui si rimanda.

Nuovi biomarcatori

Mentre le mutazioni genetiche sono eventi relativamente rari e, una volta acquisite, non sono reversibili, le modificazioni epigenetiche sono dinamiche e contribuiscono all’adattamento delle funzioni cellulari in risposta a qualsiasi stimolo. Inoltre, poiché diversi profili epigenetici sono associati a diverse patologie, essi possono contribuire anche alla comprensione dei meccanismi molecolari sottostanti la malattia e potrebbero quindi essere utilizzati come ire biomarcatori clinici (sia diagnostici sia prognostici) di differenti MCNT, tra le quali la più consolidata è il cancro (39, 78).

Per identificare i cambiamenti epigenetici indotti dall’ambiente, sono necessari biomarcatori altamente specifici e sensibili. Allo stesso tempo, il biomarcatore ideale deve essere facile da misurare, anche in un ambiente differente da quello di un laboratorio di ricerca.

La metilazione del DNA, le modificazioni istoniche, l’espressione dei microRNA, le vescicole extracellulari, la lunghezza dei telomeri e le alterazioni mitocondriali sono biomarcatori promettenti da impiegare in ambito occupazionale.

Metilazione del DNA

La metilazione del DNA è la modificazione epigenetica meglio caratterizzata. Essa consiste nell’aggiunta di un gruppo metile al quinto carbonio del nucleotide citosina del DNA, formando una 5-metil-citosina (Figura 2). Nelle cellule differenziate solo le citosine metilate seguite da una guanina possono essere metilate. Tale reazione è catalizzata da specifici enzimi, le DNA metiltransferasi, che utilizzano S-adenosil-metionina (SAM) come donatore di un gruppo metile (76). I livelli di metilazione si definiscono durante le fasi precoci del differenziamento embrionale mediante ondate di metilazione e demetilazione che avvengono durante l’embriogenesi. In seguito, quando la metilazione è stabilita (in utero), viene mantenuta nelle successive divisioni cellulari, essendo un meccanismo attraverso il quale le diverse linee cellulari divengono altamente differenziate e specializzate. Tuttavia, ogni stimolo in grado di raggiungere la cellula lungo tutto il corso della vita di un individuo può potenzialmente modulare la metilazione del DNA (3).

La metilazione del DNA che avviene a livello dei promotori dei geni, riferita come “metilazione gene-specifica”, può direttamente alterare l’espressione genica inibendo l’accesso al DNA da parte dei “macchinari” di trascrizione (79). La metilazione che avviene invece a livello di sequenze ripetute (quali ad esempio Alu, LINE-1, HERV) ha una funzione diversa, poiché permette la compattazione della struttura cromatinica, aumentando la resistenza del DNA nei confronti dell’esposizione ad agenti tossici (116).

La metilazione del DNA è il primo meccanismo che permette all’organismo di modulare l’espressione genica in risposta agli stimoli ambientali. Tale reazione adattativa potrebbe evolvere successivamente in un cambiamento stabile, potenzialmente in grado di contribuire allo sviluppo di malattie. Una delle tematiche più affascinanti e tuttora allo studio è la possibilità di un’ereditarietà transgenerazionale dei profili di metilazione del DNA. Essa potrebbe essere determinata da un effetto diretto di diverse esposizioni ambientali sui gameti o sull’embrione, oppure, essere dovuta a un vero e proprio effetto transgenerazionale su individui che non hanno direttamente vissuto l’esposizione.

Il trattamento con il bisolfito è il metodo d’elezione per l’analisi della metilazione del DNA in genomi complessi, poiché è un metodo semplice per convertire uno stato epigenetico in una diversità genetica, che può essere successivamente analizzata mediante tecniche standard di biologia molecolare, quali il pirosequenziamento.

Benché molti altri metodi siano stati sviluppati in questi ultimi anni, il trattamento con il bisolfito e l’analisi con pirosequenziamento rimangono la metodica d’elezione per valutare effetti mediati dall’esposizione ambientale, grazie alla sensibilità che permette la rilevazione anche di variazioni lievi (14).

Diversi studi hanno valutato gli effetti dell’esposizione ambientale in ambito occupazionale in termini sia di livelli di metilazione gene-specifica sia di metilazione globale.

Un aumento dei livelli di metilazione globale è stato osservato in lavoratori del carbone e in parrucchieri esposti a formaldeide (10, 28). Una riduzione dei livelli di metilazione globale è stata riportata invece per lavoratori in industrie petrolchimiche e in lavoratori esposti a basse dosi di benzene, quali gli addetti alle stazioni di rifornimento di carburante (16, 34, 95, 102). La maggior parte degli studi di metilazione condotti sui lavoratori agricoli esposti a diverse tipologie di pesticidi ha evidenziato una diminuzione dei livelli di metilazione globale, mentre Benedetti e colleghi hanno recentemente riportato ipermetilazione genomica in agricoltori della soia esposti a complesse miscele di pesticidi (12, 27, 51, 52, 97).

Per valutare gli effetti dell’esposizione occupazionale, sono stati esaminati anche i livelli di metilazione sui promotori di diversi geni, principalmente coinvolti nel rischio di cancro, poiché le alterazioni epigenetiche potrebbero essere i primi indicatori di esposizione a cancerogeni genotossici e non genotossici (99).

Nei parrucchieri, l’analisi di metilazione gene-specifica di geni selezionati correlati al cancro ha permesso l’identificazione di aumentati livelli di metilazione del gene CDKN2A, uno dei principali regolatori del ciclo cellulare (66). Livelli di metilazione aumentati di CDKN2A e degli oncosoppressori BRCA1 e BRCA2 sono stati riportati negli infermieri e nelle ostetriche (19, 88). L’aumento dei livelli di metilazione di geni oncosoppressori è stato osservato anche nei lavoratori esposti al piombo (125).

L’esposizione a basse dosi di benzene è stata associata a una metilazione aberrante del promotore di geni coinvolti nel processo di infiammazione, nello stress nitrosativo e nel metabolismo degli xenobiotici (50). Negli operatori petrolchimici è stata riportata l’espressione alterata dell’oncosoppressore p15 (16, 102). Alterati livelli di metilazione dei promotori dei geni NRF2 e KEAP1, correlati all’insorgenza di tumori, sono stati riportati nei lavoratori esposti all’arsenico (47). La metilazione del DNA dei geni implicati nella tumorigenesi F2RL3 e AHRR è stata associata all’esposizione occupazionale a idrocarburi policiclici aromatici (IPA) (4), mentre l’esposizione occupazionale al cloruro di vinile monomero è stata associata a metilazione alterata dell’oncosoppressore p16 (117) e dei geni MGMT e MLH1 implicati nell’insorgenza di tumori (122).

L’esposizione ai pesticidi è stata associata a diversi livelli di metilazione dei geni p16 (52), CDH1, GSTp1 e MGMT (97), BRCA1 e di geni coinvolti nei pathway di p70S6K e di PI3K nei linfociti B (33, 42).

I livelli di metilazione dei geni NOS3 e EDN1, coinvolti nella coagulazione, sono stati invece osservati alterati nei lavoratori dell’acciaio (108).

Goodrich e colleghi hanno riportato che l’esposizione degli operatori dentistici al mercurio (Hg) è associata a una ridotta metilazione del gene SEPP1, che è coinvolto nel bilanciamento degli effetti tossici dell’Hg nell’epitelio buccale (38).

È interessante notare che l’esposizione a lungo termine a turni di lavoro in coorti di infermieri e ostetriche è stata associata a una metilazione alterata dei geni CLOCK, coinvolti nel controllo del ritmo circadiano e le cui alterazioni sono state collegate a un aumento del rischio di tumore (18, 93).

I crescenti studi sperimentali ed epidemiologici relativi alla variazione di metilazione del DNA evidenziano che sia la metilazione globale, sia quella gene-specifica sono fortemente influenzate da esposizioni professionali suggerendo la possibilità che i marcatori epigenetici potrebbero potenzialmente essere futuri biomarcatori per la valutazione del rischio professionale.

Modificazioni istoniche

Ogni cellula umana contiene circa 2 metri di DNA, nonostante mediamente il nucleo abbia un diametro di 0,006 mm. Questa semplice osservazione sottolinea la necessità di due esigenze opposte: il DNA deve essere compattato, ma d’altra parte è necessario che mantenga l’accessibilità per poter essere trascritto, replicato e riparato. Il DNA umano viene quindi compattato avvolgendosi attorno a ottameri di proteine istoniche a formare nucleosomi: essi sono infatti costituiti da un doppio filamento di DNA di 147 coppie di basi avvolte approssimativamente due volte attorno al nucleo proteico caratterizzato da due copie di ciascuna proteina istonica H2A, H2B, H3 e H4 (69). L’interazione tra DNA e istoni è fondamentale per la trascrizione, la replicazione e la riparazione del genoma ed è regolata da oltre 100 distinte modificazioni istoniche, fra cui la fosforilazione, la metilazione, l’ubiquitinazione e l’acetilazione (127). La regolazione genica dipende in parte dalle modificazioni istoniche che si verificano principalmente sulle code dell’istone e che comportano la variazione della carica netta dell’istone centrale, modulando l’affinità tra il DNA (caricato negativamente) e l’ottamero: l’aggiunta di cariche positive comporta invece la chiusura del nucleosoma, mentre l’aggiunta di cariche negative determina un’apertura del nucleosoma (Figura 3) (48).

L’acetilazione/deacetilazione degli istoni è, probabilmente, la modificazione istonica più studiata ed è mediata dagli enzimi istone-acetiltransferasi (HAT) e istone-deacetilasi (HDAC) rispettivamente. Generalmente, l’acetilazione degli istoni è associata a geni trascrizionalmente attivi, mentre la deacetilazione è associata a geni inattivi.

Diverse condizioni ambientali (ad esempio esposizione a metalli, a inquinanti atmosferici, oppure malattie come il diabete) possono indurre modificazioni istoniche, alterando sia l’espressione gene-specifica sia la conformazione globale della cromatina (7, 20, 56, 106). È interessante notare che l’effetto determinato dall’esposizione a sostanze tossiche può permanere anche dopo che esse non sono più presenti.

Il metodo standard per l’analisi delle modificazioni istoniche è il saggio immunoassorbente legato ad un enzima (ELISA). Tuttavia, sono stati recentemente sviluppati metodi ad alta produttività combinando l’immunoprecipitazione della cromatina (ChIP) e le tecniche di analisi del DNA-microarray (chip), abbreviate come «ChIP-on-chip» (65, 91, 96).

La dimetilazione della lisina 4 dell’istone H3 (H3K4me2) e l’acetilazione della lisina 9 dell’istone H3 (H3K9ac) sono due modificazioni istoniche associate agli stati di cromatina aperta e considerate come marcatori principali delle esposizioni ambientali (9). H3K4me2 e H3K9ac sono stati associati a diverse esposizioni occupazionali, inclusi diversi metalli come nichel, arsenico e ferro, e IPA e benzene (7, 20, 21, 55, 64, 70, 126). Mentre le variazioni dei livelli di metilazione del DNA sembrano variare in pochi giorni, le modificazioni istoniche sono probabilmente un adeguato biomarcatore epigenetico indotto da esposizioni a lungo termine. Tuttavia, poiché la loro analisi completa è pressoché impossibile da ottenere e le analisi specifiche delle modificazioni richiedono un ampio tempo di elaborazione, le modificazioni istoniche sono ancora largamente inesplorate in ampie coorti epidemiologiche.

Espressione di microRNA

I microRNA (miRNA) sono brevi RNA di circa 22 nucleotidi di lunghezza. I miRNA regolano l’espressione genica a livello post-trascrizionale, silenziando l’espressione proteica mediante il taglio e la degradazione del trascritto dell’RNA messaggero (mRNA) o inibendo la traduzione (23) (Figura 4). Un singolo miRNA può legare più mRNA target (più di 100), mentre diversi miRNA possono regolare un singolo target di mRNA (35).

L’espressione relativa dei miRNA può essere studiata con varie tecniche, come i metodi basati sull’ibridazione (per esempio microarray) usati come iniziale approccio per identificare i potenziali miRNA candidati, o mediante PCR quantitativa (qPCR) usati per convalidare miRNA altamente deregolati. La qPCR, grazie agli elevati livelli di precisione e accuratezza, rimane il metodo d’elezione per la quantificazione del miRNA. Inoltre, i miRNA possono essere sequenziati e quantificati utilizzando piattaforme di sequenziamento di nuova generazione (NGS) (2).

Grazie alla loro stabilità, i miRNA sono stati ampiamente studiati nel sangue periferico e nelle urine come potenziali biomarcatori di esposizione occupazionale. La ridotta espressione di miR-24-3p, miR-27a-3p, miR-142-5p e miR-28-5p nel sangue è stata associata ai livelli di monoidrossi-IPA urinario e benzo [a] pirene-r-7, t- 8 addotti di c-10-tetraidrotetrol-albumina (BPDE-Alb) nel sangue in lavoratori del coke (29). L’espressione di due miRNA (miR-6819-5p e miR-6778-5p) è risultata aumentata nel sangue di lavoratori esposti a solventi organici, come etilbenzene, toluene e xilene, mentre l’aumentata espressione di miR-92a e miR-486 è stata riportata in campioni di plasma in associazione all’esposizione professionale cronica al mercurio (31, 105). In uno studio condotto su una casistica di vigili del fuoco, è stata riportata una ridotta espressione di miR-548h-5p, miR-145-5p, miR-4516, miR-331-3p, miR-181a-5p e miR-1260a, tutti coinvolti in attività di soppressione tumorale, mentre l’espressione di miR-374a-5p e miR-486-3p, coinvolti nella sopravvivenza del cancro, è risultata aumentata (49).

I livelli di miRNA nelle urine sono stati valutati anche come biomarcatori di esposizione ai pesticidi. È interessante notare che l’espressione di miR-223, -518d-3p, -597, -517b, -133b e -28-5p è positivamente associata alla stagione post-raccolta nei lavoratori agricoli, con una relazione dose-risposta positiva con metaboliti di pesticidi organofosfati (118).

Sebbene i miRNA abbiano la potenzialità di essere sensibili biomarcatori di diverse esposizioni, sono necessari ulteriori studi in popolazioni più ampie che convalidino i risultati sinora emersi e valutino attentamente la loro validità tenendo conto dei diversi fattori che possono modificare la loro espressione.

Vescicole extracellulari

Le vescicole extracellulari (EV) sono un gruppo eterogeneo di vescicole circondate da membrana, che vengono rilasciate dalle cellule in condizioni fisiologiche e patologiche (124). Le EV svolgono un ruolo centrale nella comunicazione inter-cellulare, poiché sono in grado di trasferire molecole attive biologiche, fra cui proteine e acidi nucleici (113). È di particolare interesse il fatto che le EV contengano miRNA, potenzialmente in grado di modulare l’espressione cellulare «a distanza» (124). Poiché le EV possono trasferire informazioni da una cellula all’altra, rappresentano un potenziale meccanismo in grado di chiarire come diverse esposizioni ambientali comportino effetti su diversi meccanismi molecolari (figura 5). Le EV sono state rilevate nella maggior parte dei fluidi corporei, tra cui sangue, urina, saliva, liquido cerebrospinale, liquido di lavaggio bronco-alveolare, liquido amniotico, liquido seminale e latte materno.

Lo studio delle EV è un campo di ricerca piuttosto nuovo, e la standardizzazione dei metodi per il loro isolamento e caratterizzazione è ancora dibattuta. Le attuali linee guida per l’analisi delle EV sono riportate nelle Informazioni minime per gli studi sulle vescicole extracellulari 2018 (MISEV2018) (109).

In un recente studio, abbiamo isolato EV dal plasma di 55 lavoratori maschi sani impiegati per almeno 1 anno in un impianto di produzione di acciaio, prima e dopo l’esposizione a PM sul posto di lavoro, e abbiamo valutato l’espressione di 88 miRNA associati a EV mediante qPCR. L’espressione dei miR-128 e miR-302c è risultata aumentata dopo 3 giorni di esposizione a PM sul luogo di lavoro. Inoltre, esperimenti in vitro condotti sulla linea cellulare derivata dall’epitelio alveolare A549 hanno confermato un’espressione dose-dipendente di miR-128 in EV rilasciate dopo 6 ore di trattamento con PM. Questi risultati suggeriscono che l’esposizione a PM induca il rilascio di miRNA specifici all’interno di EV generate da cellule alveolari o di altre cellule polmonari, che possono poi essere rilevate nel plasma (17). Inoltre, nella stessa coorte, l’aumentata espressione di 17 miRNA contenuti all’interno di EV è stata associata a livelli individuali di esposizione a PM e metalli, suggerendo il coinvolgimento di diversi meccanismi molecolari come la biosintesi di insulina, l’infiammazione e la coagulazione in risposta a tali esposizioni specifiche (82).

Lunghezza dei telomeri

Tutte le cellule possiedono una sorta di orologio biologico nei telomeri, ossia sequenze di DNA situate alle estremità dei cromosomi (Figura 6) coinvolte nel mantenimento della stabilità genomica e nella regolazione della proliferazione cellulare (67). I telomeri sono costituiti da sequenze ripetute dei DNA (TTAGGG) che, con le proteine ad essi associate, formano un complesso di protezione che ricopre le estremità cromosomiche e protegge la loro integrità (25). La stabilità cromosomica si perde gradualmente con l’accorciamento dei telomeri ad ogni ciclo di divisione cellulare. La lunghezza dei telomeri (TL) può essere misurata in cellule mononucleate del sangue periferico (Lunghezza dei Telomeri Leucocitari, LTL) come marcatori dell’invecchiamento biologico (73). Infatti, nella proliferazione dei tessuti, la LTL è più lunga alla nascita e si accorcia progressivamente con l’avanzare dell’età anagrafica degli individui (25).

Studi epidemiologici retrospettivi e prospettici hanno dimostrato che l’accorciamento della LTL è un fattore di rischio per le MCNT correlate all’età (40, 83, 85). Lo stress ossidativo e l’infiammazione, i due principali meccanismi intermedi per tali malattie, sono anche fattori di rischio per l’accorciamento della LTL (84, 86). L’erosione dei telomeri può tuttavia essere ulteriormente accelerata da fattori di stress esterni. I telomeri, infatti, come sequenze contenenti triplette di guanina, sono altamente sensibili alle esposizioni genotossiche fisiche e chimiche. L’esposizione occupazionale ai composti genotossici potrebbe accelerare il processo fisiologico di erosione dei telomeri e facilitare l’insorgenza di MCNT, sia direttamente danneggiando il DNA sia indirettamente, favorendo l’effetto cumulativo dei danni ossidativi e l’insorgenza dell’infiammazione cronica (15).

Le LTL sono misurate usando i metodi di qPCR descritti da Cawthon (24). Questo saggio misura il rapporto LTL relativo, T / S, determinando il rapporto tra il numero di copie telomeriche ripetute (T) a un gene a singola copia (S), in un dato campione rispetto a quello di un DNA di riferimento. Il gene a copia singola utilizzato in questo tipo di studi è di solito la β-globina umana (HBB). Questa tecnica può essere effettuata anche con strumentazioni ad alta processività (high-throughput) ed è pertanto ampiamente utilizzato in studi di popolazioni anche di grandi dimensioni (46).

I nostri gruppi di ricerca hanno pubblicato le prime evidenze di accorciamento delle LTL in associazione con esposizioni occupazionali: LTL diminuita nei lavoratori del traffico esposti al benzene (43) e nei lavoratori del coke esposti ad alti livelli di idrocarburi policiclici aromatici (80). Dopo questa osservazione iniziale, Fu e colleghi hanno confermato la riduzione della LTL in una popolazione cinese di lavoratori del coke, in uno studio longitudinale (36). Anche l’esposizione a livelli elevati di monomero di cloruro di vinile, quella a N-nitrosammine nelle industrie della gomma e all’esposizione a policlorobifenili in una società di trasformazione del ciclico, sono state associate a riduzioni della LTL (128, 129, 62, 130). Nei parrucchieri, l’esposizione alle ammine aromatiche, valutata mediante addotti di emoglobina, riduce la LTL (66). Gli studi che valutano le esposizioni correlate al PM sul lavoro riportano coerentemente le modifiche della LTL in associazione con l’esposizione a lungo termine (43, 63, 121). La riduzione della LTL è stata riportata anche in lavoratori delle fonderie esposti a Piombo (87).

Diversi studi associano l’esposizione ai pesticidi alla LTL, ma i risultati non sono conclusivi. Una diminuzione di LTL nel sangue è stata trovata in diversi tipi di esposizioni (51, 52, 98). Risultati simili sono stati riportati anche per TL misurato nel DNA dalla saliva (41). D’altro canto, è stato segnalato un aumento della LTL in associazione all’esposizione a diversi pesticidi (6, 32, 115).

L’associazione di LTL con esposizione a radiazioni ionizzanti presenta risultati contrastanti. I livelli minori di LTL sono stati osservati negli operai addetti alle pulizie della centrale nucleare di Chernobyl (CNPP) esposti a bassi livelli di radiazione (45). Al contrario, maggiore lunghezza della LTL è stata rilevata negli operai addetti alla pulizia di CNPP che hanno lavorato nel 1986, in quelle attività considerate “contaminanti” (scavatura e disattivazione) (92) e nei lavoratori di un impianto di produzione di plutonio (100). Gli autori suggeriscono che i telomeri più lunghi, rilevati in persone maggiormente esposte alle radiazioni ionizzanti, probabilmente indicano una successiva attivazione della telomerasi come meccanismo di riparazione/protezione del cromosoma in seguito al danno e riflettono difetti nella regolazione della telomerasi che potrebbero potenziare la carcinogenesi. L’accorciamento della LTL è stato riportato anche in lavoratori che effettuano cateterismo cardiaco, e sono perciò esposti a radiazioni ionizzanti a basse dosi a lungo termine (5).

La TL può essere considerata una buona misura per valutare l’effetto di un’ampia gamma di esposizioni professionali sull’invecchiamento biologico come condizione correlata a un rischio precoce di sviluppo e mortalità delle MCNT.

Numero di copie del DNA mitocondriale

La maggior parte delle cellule dei mammiferi contiene da centinaia a più di un migliaio di mitocondri ciascuna. Un mitocondrio è un organello essenziale delle cellule eucariotiche, che svolge molte funzioni in grado di assicurare il differenziamento, la sopravvivenza e il controllo della morte cellulare (59). Il mitocondrio funziona come una fabbrica di adenosina trifosfato (ATP) e metaboliti, utili per la sopravvivenza cellulare, e rilascia il citocromo C per attivare i meccanismi implicati nella morte cellulare. Ogni organello ospita 2-10 copie di DNA mitocondriale (mtDNA). Il mtDNA è noto per essere più sensibile al danno ossidativo rispetto al DNA nucleare a causa della mancanza di istoni protettivi, introni e di un efficiente meccanismo di riparazione del DNA (90). L’aumento dello stress ossidativo può contribuire alle alterazioni del numero di copie (mtDNAcn) e all’integrità del mtDNA nelle cellule umane (60, 61). Studi epidemiologici hanno associato il numero ridotto di mtDNAcn nei leucociti con una serie di esiti clinici avversi, tra cui tutte le cause di mortalità, cardiopatia coronarica e morte cardiaca improvvisa, sindrome metabolica e malattia renale cronica (8, 26, 110). Pertanto, mtDNAcn può essere considerato come un promettente biomarcatore per la valutazione degli effetti sulla salute correlati allo stress ossidativo. La progressiva perdita della funzione mitocondriale è una caratteristica comune dell’invecchiamento influenzata dalla produzione per tutta la vita di ROS, come sottoprodotti del metabolismo ossidativo (11, 54).

mtDNAcn viene misurato utilizzando un metodo di qPCR simile a quello utilizzato per l’analisi della TL. Il test misura il mtDNAcn relativo determinando il rapporto del numero di copie del DNA mitocondriale (MT) nel numero di copie del gene a copia singola (S) in campioni sperimentali relativi al rapporto MT/S rispetto a un campione di riferimento (22, 81).

Dato che il mtDNA è altamente soggetto a danni, alcuni studi hanno esplorato gli effetti in seguito ad esposizione occupazionale a diversi inquinanti. I risultati hanno rilevato che l’alterazione del mtDNAcn nel sangue periferico può essere correlata a esposizioni tossiche, come gli IPA (81, 123) e il benzene (22).

È stato suggerito che lo stress ossidativo, come conseguenza dell’esposizione agli IPA, abbia una doppia influenza sul contenuto di DNA mitocondriale. L’esposizione ambientale a basse dosi di IPA può stimolare la produzione di DNA mitocondriale per soddisfare i bisogni respiratori della cellula al fine di consentire la sopravvivenza cellulare (89). D’altra parte, una diminuzione o una totale assenza di sintesi del mtDNA potrebbe essere determinata dall’elevato stress ossidativo generato ad esempio dal fumo di tabacco contenente molte sostanze chimiche tossiche, cancerogene e mutagene, così come dalla presenza di radicali liberi stabili e instabili e dalle specie reattive dell’ossigeno (ROS), in grado di causare danno ossidativo del DNA. Tale condizione potrebbe portare alla senescenza e alla morte cellulare. Questa ipotesi può anche spiegare i diversi risultati ottenuti in dalla valutazione di mtDNAcn in associazione a esposizioni occupazionali.

È ancora necessaria una considerevole ricerca per comprendere gli effetti dell’esposizione a sostanze tossiche sul mtDNAcn.

Marcatori di esposizione o marcatori di effetto?

I biomarcatori che sono stati descritti in questo articolo sono modificati da molti fattori e, probabilmente, ogni stimolo che il nostro organismo riceve può essere successivamente tradotto in “memoria epigenetica”.

Per questo motivo, i biomarcatori epigenetici non possono essere considerati marcatori di singole esposizioni, in quanto non sono specifici per una particolare tossicità professionale e non sono utili per quantificare la dose individuale a cui ciascun lavoratore è stato esposto. Ciononostante, questi marcatori potrebbero diventare importanti indicatori di effetto precoce, e potrebbero aiutare il medico del lavoro a identificare i lavoratori a più alto rischio di sviluppare malattie specifiche in un determinato contesto lavorativo.

Il concetto di medicina di precisione postula che la medicina dovrebbe fare prevenzione e mettere a punto trattamenti personalizzati tenendo conto della genomica di ciascun paziente, delle condizioni preesistenti, delle esposizioni e di una varietà di fattori di rischio potenziali esclusivi di ciascun individuo. L’epigenetica potrebbe integrare questo concetto, facendo luce sulla suscettibilità individuale alle sostanze tossiche e fornendo strumenti insostituibili per misurare tale suscettibilità in termini quantitativi. I dati dell’epigenetica potenziano quindi diversi parametri come la tossicodinamica, la tossicocinetica e il meccanismo di azione delle sostanze tossiche all’interno dell’organismo, contribuendo così in ultima analisi ai processi di valutazione del rischio (101).

Tuttavia, questi marcatori non sono ancora stati standardizzati, quindi il prossimo passo per tradurre i risultati dalla ricerca di base alla medicina dovrà andare in questa direzione.

La sfida che i medici del lavoro e i ricercatori devono affrontare è considerevole, in quanto è necessaria l’interpretazione di questi marcatori non solo in termini di rischio occupazionale ma anche come indicatori di rischio associato a stili di vita modificabili. Se l’intera comunità professionale e scientifica della medicina del lavoro e della salute pubblica accetterà questa sfida, le nuove conoscenze acquisite permetteranno un notevole passo avanti nella comprensione dei rischi occupazionali, favorendo la promozione della protezione della salute e del benessere dei lavoratori.

References

- 1.Abi Khalil C. The emerging role of epigenetics in cardiovascular disease. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2014;5:178–187. doi: 10.1177/2040622314529325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agrawal S, Tapmeier T, Rahmioglu N, et al. The miRNA Mirage: How Close Are We to Finding a Non-Invasive Diagnostic Biomarker in Endometriosis? A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19 doi: 10.3390/ijms19020599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alegria-Torres JA, Baccarelli A, Bollati V. Epigenetics and lifestyle. Epigenomics. 2011;3:267–277. doi: 10.2217/epi.11.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alhamdow A, Lindh Hagberg J, et al. DNA methylation of the cancer-related genes F2RL3 and AHRR is associated with occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Carcinogenesis. 2018;39:869–878. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgy059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andreassi MG, Piccaluga E, Gargani L, et al. Subclinical carotid atherosclerosis and early vascular aging from long-term low-dose ionizing radiation exposure: a genetic, telomere, and vascular ultrasound study in cardiac catheterization laboratory staff. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:616–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.12.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andreotti G, Hoppin JA, Hou L, et al. Pesticide Use and Relative Leukocyte Telomere Length in the Agricultural Health Study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arita A, Niu J, Qu Q, et al. Global levels of histone modifications in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of subjects with exposure to nickel. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:198–203. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashar FN, Moes A, Moore AZ, et al. Association of mitochondrial DNA levels with frailty and all-cause mortality. J Mol Med (Berl) 2015;93:177–186. doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1233-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baccarelli A, Bollati V. Epigenetics and environmental chemicals. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:243–251. doi: 10.1097/mop.0b013e32832925cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbosa E, Dos Santos ALA, Peteffi GP, et al. Increase of global DNA methylation patterns in beauty salon workers exposed to low levels of formaldehyde. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2019;26:1304–1314. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3674-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellizzi D, Cavalcante P, Taverna D, et al. Gene expression of cytokines and cytokine receptors is modulated by the common variability of the mitochondrial DNA in cybrid cell lines. Genes Cells. 2006;11:883–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benedetti D, Lopes Alderete B, de Souza CT, et al. DNA damage and epigenetic alteration in soybean farmers exposed to complex mixture of pesticides. Mutagenesis. 2018;33:87–95. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gex035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bertazzi PA. Medicina del lavoro. Lavoro, ambiente, salute. 2013 Cortina Raffaello. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhattacharjee R, Moriam S, Umer M, et al. DNA methylation detection: recent developments in bisulfite free electrochemical and optical approaches. Analyst. 2018;143:4802–4818. doi: 10.1039/c8an01348a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blackburn EH, Epel ES, Lin j. Human telomere biology: A contributory and interactive factor in aging, disease risks, and protection. Science. 2015;350:1193–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.aab3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bollati V, Baccarelli A, Hou L, et al. Changes in DNA methylation patterns in subjects exposed to low-dose benzene. Cancer Res. 2007;67:876–880. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bollati V, Angelici L, Rizzo G, et al. Microvesicle-associated microRNA expression is altered upon particulate matter exposure in healthy workers and in A549 cells. J Appl Toxicol. 2015;35:59–67. doi: 10.1002/jat.2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bukowska-Damska A, Reszka E, Kaluzny P, et al. Sleep quality and methylation status of core circadian rhythm genes among nurses and midwives. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34:1211–1223. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2017.1358176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bukowska-Damska A, Reszka E, Kaluzny P, et al. Sleep quality and methylation status of selected tumor suppressor genes among nurses and midwives. Chronobiol Int. 2018;35:122–131. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2017.1376219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cantone L, Nordio F, Hou L, et al. Inhalable metal-rich air particles and histone H3K4 dimethylation and H3K9 acetylation in a cross-sectional study of steel workers. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:964–969. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantone L, Angelici L, Bollati V, et al. Extracellular histones mediate the effects of metal-rich air particles on blood coagulation. Environ Res. 2014;132:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carugno M, Pesatori AC, Dioni L, et al. Increased mitochondrial DNA copy number in occupations associated with low-dose benzene exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:210–215. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Catalanotto C, Cogoni C, Zardo G. MicroRNA in Control of Gene Expression: An Overview of Nuclear Functions. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(10) doi: 10.3390/ijms17101712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cawthon RM. Telomere length measurement by a novel monochrome multiplex quantitative PCR method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(3):e21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan SR, Blackburn EH. Telomeres and telomerase. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:109–121. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen S, Xie X, Wang Y, et al. Association between leukocyte mitochondrial DNA content and risk of coronary heart disease: a case-control study. Atherosclerosis. 2014;237:220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collotta M, Bertazzi PA, Bollati V. Epigenetics and pesticides. Toxicology. 2013;307:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Souza MR, Kahl VFS, Rohr P, et al. Shorter telomere length and DNA hypermethylation in peripheral blood cells of coal workers. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 2018;836(Pt B):36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng Q, Huang S, Zhang X, et al. Plasma microRNA expression and micronuclei frequency in workers exposed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:719–725. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng Q, Luo Y, Chang C, et al. The Emerging Epigenetic Role of CD8+T Cells in Autoimmune Diseases: A Systematic Review. Front Immunol. 2019;10:856. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ding E, Zhao Q, Bai Y, et al. Plasma microRNAs expression profile in female workers occupationally exposed to mercury. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:833–841. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.03.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duan X, Yang Y, Wang S, et al. Cross-sectional associations between genetic polymorphisms in metabolic enzymes and longer leukocyte telomere length induced by omethoate. Oncotarget. 2017;8:80638–80644. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fagny M, Patin E, MacIsaac JL, et al. The epigenomic landscape of African rainforest hunter-gatherers and farmers. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10047. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fenga C, Gangemi S, Costa C. Benzene exposure is associated with epigenetic changes (Review) Mol Med Rep. 2016;13:3401–3405. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.4955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, et al. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu W, Chen Z, Bai Y, et al. The interaction effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons exposure and TERT- CLPTM1L variants on longitudinal telomere length shortening: A prospective cohort study. Environ Pollut. 2018;242(Pt B):2100–2110. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gochfeld M. Factors influencing susceptibility to metals. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105(Suppl 4):817–822. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105s4817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodrich JM, Basu N, Franzblau A, et al. Mercury biomarkers and DNA methylation among Michigan dental professionals. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2013;54:195–203. doi: 10.1002/em.21763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]